Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to assess patient‐reported outcomes (PROs), including health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and anxiety and depression symptoms, and to identify associated variables in patients with tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI)‐resistant chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) in chronic‐phase (CP) or accelerated‐phase (AP) who were receiving olverembatinib.

Methods

Patients in multicenter studies were invited to complete the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality‐of‐Life Core 30 Questionnaire, the Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale, and the Self‐Rating Depression Scale at baseline and regularly during olverembatinib therapy. The time trends in PROs were estimated with a linear model using a generalized estimating equation based on an independent working correlation matrix. A generalized estimating equation model was used to assess the variables associated with PROs.

Results

In total, 146 patients with CML‐CP or CML‐AP were included in this study. Scores on seven items from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality‐of‐Life Core 30 Questionnaire, including global health, physical functioning, emotional functioning, fatigue, dyspnea, diarrhea, and financial difficulties, improved significantly over time during olverembatinib therapy. In multivariate analysis, age younger than 40 years was significantly associated with greater improvement in social functioning (p = .033), and CML‐CP (vs. CML‐AP) was associated with greater improvements in dyspnea (p = .031) and diarrhea (p = .031) over time. Scores on the Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale and the Self‐Rating Depression Scale decreased significantly over time during olverembatinib treatment (p < .001).

Conclusions

The authors concluded that HRQoL significantly improved over time during olverembatinib therapy in heavily treated patients with TKI‐resistant CML, especially among those who were younger and those who had CML‐CP. Anxiety symptoms also significantly decreased over time.

Keywords: chronic myeloid leukemia, health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), olverembatinib, Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Self‐Rating Depression Scale (SDS)

Short abstract

Health‐related quality of life as well as symptoms of anxiety and depression significantly improved during olverembatinib therapy in patients who had tyrosine kinase inhibitor‐resistant chronic myeloid leukemia, especially those who were younger and those in chronic phase versus accelerated phase. Anxiety symptoms significantly decreased over time.

INTRODUCTION

The introduction of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), including third‐generation (3G) TKIs, has improved the outcomes of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Information on patient‐reported outcomes (PROs), including health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) and symptom profiles, is necessary to improve overall treatment outcomes of TKI therapy. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Several studies on HRQoL have focused on patients who had CML treated with imatinib, second‐generation TKIs, and asciminib. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Despite studies on the efficacy and safety of 3G TKIs, 6 , 7 , 8 , 16 data on PROs in patients receiving 3G TKIs are rare. Olverembatinib is a novel, small‐molecule, orally administered, 3G BCR::ABL1 inhibitor that is effective in TKI‐resistant patients who have Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)‐positive CML or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. 6 , 17 The objective of the current study was to assess HRQoL profiles and the prevalence of self‐reported symptoms of anxiety and depression and to identify variables associated with these symptoms in heavily treated patients with TKI‐resistant, chronic‐phase (CP) or accelerated‐phase (AP) CML (CML‐CP or CML‐AP) who were receiving olverembatinib.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

This multicenter study included individuals who experienced resistance to previous imatinib and/or second‐generation TKI therapies and switched to olverembatinib (in phase 1 since October 2016 [Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (www.chictr.org.cn) identifier, ChiCTR1900027568] and in phase 2 since May 2019 [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03883100]). Patients were invited to participate in the PRO study. All participants were aged 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of Ph‐positive and/or BCR::ABL1‐positive CML‐CP or CML‐AP according to European LeukemiaNet (ELN) criteria, and had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score <2. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 The patients' HRQoL scores were assessed using the Chinese version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality‐of‐Life Core 30 Questionnaire (QLQ‐C30) before the initiation of olverembatinib therapy and at various visit time points (3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months) during olverembatinib treatment. 22 , 23 , 24 The participants from Peking University People's Hospital also completed anxiety and depression symptom scales: the Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Self‐Rating Depression Scale (SDS). 25 , 26 Patients who discontinued participation in the study were deemed ineligible for subsequent assessments. In the event of any progression within this period, the protocol required that patients complete a PRO assessment as close as possible to the time of disease progression, after which they would be excluded from further assessments.

Clinical and laboratory data, treatment responses, and patient outcomes were obtained from medical records. The study adhered strictly to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Assessment of efficacy

Disease phase, treatment response definitions, and assessment criteria were based on the ELN‐recommended assessment. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 Hematologic, cytogenetic, and molecular analyses were performed as described previously. 6 A complete hematologic response, a major cytogenetic response, a complete cytogenetic response, and a major molecular response (MMR) were defined according to ELN criteria. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21

Assessment of safety

Adverse events (AEs) were assessed continuously and were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.18. Complete blood counts with differential, serum chemistry, and physical examinations were performed before the study, weekly during months 1 and 2, on alternate weeks in months 3 and 4, and monthly thereafter.

Assessment of HRQoL

HRQoL was assessed by the well validated Chinese version of the cancer‐specific EORTC QLQ‐C30, which was validated in China, 20 , 21 before and at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months of olverembatinib therapy until disease progression to AP or BP.

The EORTC QLQ‐C30, which is one of the most commonly used measures to assess HRQoL in patients with cancer, 24 contains a total of 30 items that can be grouped into 15 domains: five functional domains (physical, role, cognitive, and emotional and social functioning), three symptomatic domains (fatigue, pain, and nausea and vomiting), one general health status/quality‐of‐life domain, and six single domains (dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhea, and financial difficulties). The scores of the items included in each domain are summed and divided by the number of items included to obtain the total score of the domain (raw score, RS: RS = [Q1 + Q2 + … Qn]/n). To make the scores of each domain comparable to each other, a linear transformation was further performed using the polarization method to convert the RS into a standardized score (SS) with values ranging from 0 to 100. The following formulas were used: functional domain, SS = [1 − (RS − 1)/R] × 100; symptom domain and general health status domain, SS = [(RS − 1)/R] × 100. Higher scores in the functional domain and the general health status domain indicate better functional status and HRQoL, whereas higher scores in the symptom domain indicate more symptoms or problems (poorer HRQoL).

Assessment of anxiety and depression symptoms

Anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed using the SAS and the SDS, respectively, which are widely used, user‐friendly instruments for self‐assessment by patients. 25 , 26 Moreover, the Chinese adaptations of these scales have been validated in epidemiologic surveys. 27 , 28 Both of these scales are 20‐item self‐report assessment instruments, with the total scores derived from the summation of the scores of the 20 items. The standard score is obtained by multiplying the total score by a factor of 1.25. For anxiety and depression symptoms, the respective standard cutoff scores are 50 and 53. Following the guidelines set forth by the China Mental Health Center, for this study, we used specific ranges for the standard SAS scores, namely, 25–49 (normal), 50–59 (mild anxiety), 60–69 (moderate anxiety), and 70 (severe anxiety). Similarly, the standard SDS scores were categorized into ranges of 25–52 (normal), 53–62 (mild depression), 63–72 (moderate depression), and 73 (severe depression).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described using medians (ranges) and means ± standard deviations, and categorical variables are described using counts (percentages). The Pearson χ2 test (for categorical variables) and the Mann‒Whitney U test (for continuous variables) were used to measure between‐group differences in variables.

Univariate and multivariate general linear models were used to assess the impact of baseline variables on each of the scale scores (QLQ‐C30 score, SAS standard score, and SDS standard score). The time trends of the PROs were estimated with a linear model using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) based on the independent working correlation matrix. The GEE model was also used to assess the impact of achieving an MMR (yes vs. no; time‐dependent variable) and other baseline variables on longitudinal quality of life. The QLQ‐C30 score, the SAS standard score, and the SDS standard score were regressed on MMR achievement (yes vs. no; time‐varying covariate), age, sex, CML phase, interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib therapy, and treatment duration. The interactions of these covariates were also included in the model to evaluate whether HRQoL changed over time in a different manner. We used the GENMOD procedure in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) to fit the GEEs. Two‐sided p values < .05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses and plots in this study were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corporation), SAS version 9.4, and GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

In total, 146 patients with CML‐CP (n = 114) or CML‐AP (n = 32) were included in this study. The median age was 42 years (range, 20–74 years). Ninety‐four patients (64%) were male. The median interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation was 5.5 years (range, 0.4–23 years). Sanger sequencing at baseline revealed that 19 patients (13%) harbored no BCR::ABL1 mutations, 92 (63%) harbored a single T315I mutation, 22 (15%) harbored a T315I mutation and other mutations, and 13 (9%) harbored non‐T315I mutations. In total, 102 patients with CML‐CP (n = 85) or CML‐AP (n = 17) completed the SAS and SDS questionnaires (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | HRQoL, No. (%) | SAS/SDS, No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 146 (100.0) | 102 (100.0) |

| Age: Median [range], years | 42 [20–74] | 40 (20–64) |

| Men | 94 (64.4) | 66 (64.7) |

| Time from diagnosis to olverembatinib treatment: Median [range], years | 5.5 [0.4–23.2] | 5.9 [0.4–15.2] |

| Prior TKI | ||

| Imatinib | 19 (13.0) | 15 (14.7) |

| Imatinib/dasatinib | 54 (37.0) | 32 (31.4) |

| Imatinib/nilotinib | 25 (17.1) | 18 (17.6) |

| Imatinib/dasatinib/nilotinib | 36 (24.7) | 28 (27.5) |

| Nilotinib | 6 (4.1) | 5 (4.9) |

| Dasatinib | 2 (1.4) | 0 |

| Dasatinib/nilotinib | 4 (2.7) | 4 (3.9) |

| No. of lines of prior TKI therapy | ||

| 1 | 27 (18.5) | 20 (19.6) |

| 2 | 83 (56.8) | 54 (52.9) |

| ≥3 | 36 (24.7) | 28 (27.5) |

| BCR::ABL1 mutation status by Sanger sequencing | ||

| No mutation | 19 (13.0) | 19 (18.6) |

| T315I single mutation | 92 (63.0) | 55 (53.9) |

| T315I and other mutations | 22 (15.1) | 15 (14.7) |

| Other mutations | 13 (8.9) | 13 (12.7) |

| CML stage | ||

| CML‐CP | 114 (78.1) | 85 (83.3) |

| CML‐AP | 32 (21.9) | 17 (16.7) |

Abbreviations: CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; CML‐AP, chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase; CML‐CP, chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase; HRQoL, health‐related quality of life; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Response

During the 3‐year follow‐up, 104 of 110 patients (95%) with an assessable hematologic response achieved a complete hematologic response. Of the 142 patients who were evaluated for a cytogenetic response, 108 (76%) achieved a major cytogenetic response, and 97 (68%) achieved a complete cytogenetic response. Among all patients, 87 (60%) achieved an MMR, 33 (23%) achieved a molecular response of a 4.5‐log transcript reduction on the international scale, 16 progressed to the advanced phase, and 25 died from disease progression (n = 16) or other comorbidities (n = 9).

Safety

All 146 patients experienced at least one treatment‐related AE, of which 120 (82%) were grade 3/4. One hundred twenty‐four patients (85%) experienced hematologic AEs. The most frequent hematologic AE was thrombocytopenia (76%), of which 58% were grade 3/4, followed by anemia (58%), of which 21% were grade 3/4. Most severe AEs resolved after temporary treatment suspension or dose reduction (see Table S2).

Health‐related quality of life

At baseline

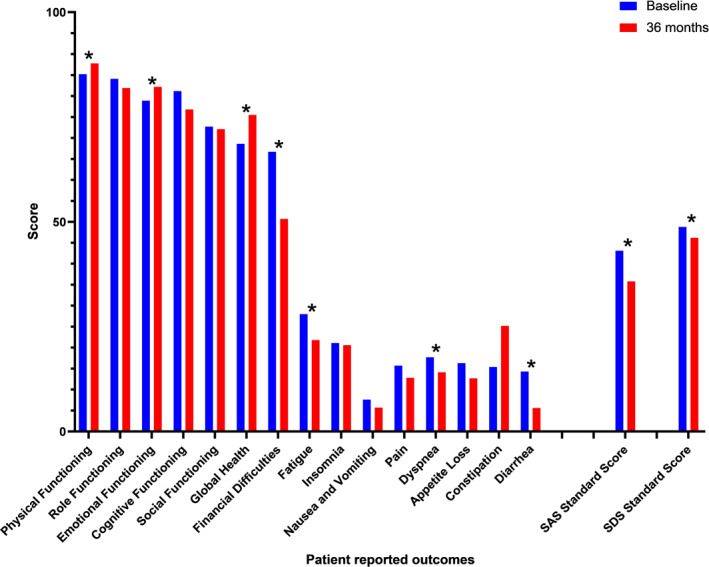

The three most severe symptom burdens (mean ± standard deviation score) reported by patients before olverembatinib therapy were financial difficulties (67 ± 35), fatigue (28 ± 23), and insomnia (21 ± 28). The remaining 12 domains were assessed in terms of physical functioning (85 ± 15), role functioning (84 ± 26), emotional functioning (79 ± 20), cognitive functioning (81 ± 20), social functioning (73 ± 25), global health/quality of life (69 ± 23), nausea and vomiting (8 ± 15), diarrhea (14 ± 24), pain (16 ± 19), constipation (15 ± 24), loss of appetite (16 ± 23), and dyspnea (18 ± 22; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in patient‐reported outcomes over time (baseline and 36 months; *p < .05). SAS indicates the Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale; SDS, Self‐Rating Depression Scale.

To identify variables associated with HRQoL at baseline, the demographic characteristics (sex, age), disease phase, interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation, and BCR::ABL1 mutation status of patients were analyzed. In multivariate analyses, an interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation ≥5 years (vs. <5 years) was significantly associated with poor cognitive functioning (p = .014). Lack of a BCR::ABL1 mutation (vs. T315I with or without other mutations) was significantly associated with poor cognitive functioning (p = .014), poor emotional functioning (p = .030), and severe constipation (p = .021).

During olverembatinib therapy

In total, 129 (88%), 118 (81%), 119 (82%), 96 (66%), and 102 (69%) patients completed the questionnaire at 3 months, 6 months, 12 months, 24 months, and 36 months, respectively (see Table S1). The three most severe symptom burdens (mean ± standard deviation score) reported by the patients after 36 months of olverembatinib therapy were financial difficulties (50 ± 37), constipation (25 ± 28), and fatigue (22 ± 20; Figure 1).

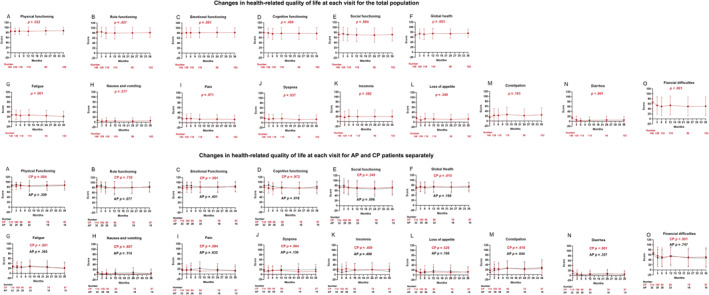

The dynamic HRQoL profile during olverembatinib therapy was estimated with a linear model using a GEE based on the independent working correlation matrix. The scores for seven scale items, including the global health (p = .003), physical functioning (p = .022), and emotional functioning (p = .001) items, significantly improved over time, which indicated better functional status; the scores for the symptom scale items, including fatigue (p < .001), dyspnea (p = .037), diarrhea (p < .001), and financial difficulties (p < .001), decreased significantly, which indicated fewer symptoms or problems (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

(A–O) Changes in health‐related quality of life at each visit.

To identify variables associated with the changes in HRQoL during olverembatinib therapy, a linear model using the GEE, which included patients' demographic characteristics (sex and age [younger than 40 years vs. 40 years and older]), disease phase (CML‐CP vs. CML‐AP), interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation (<5 years vs. ≥5 years) at baseline, and treatment response (MMR achievement, yes vs. no) at each visit during treatment, was used in multivariate analyses. MMR achievement (yes vs. no) was a time‐dependent variable that represented the MMR status before each assessment. The interactions of age, sex, CML phase, and interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation with treatment duration (visit * age, visit * sex, visit * CML phase, visit * interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation) were also included in the model to assess whether HRQoL changed over time.

In multivariate analyses, age younger than 40 years was associated with greater improvement in social functioning (p = .033), and CML‐CP (vs. CML‐AP) was associated with greater improvement in dyspnea (p = .031) and diarrhea (p = .031) over time as the number of cycles of olverembatinib therapy increased. In addition, in multivariate analyses, an interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation <5 years (vs. ≥5 years) was associated with better physical functioning (p = .023), social functioning (p = .029), cognitive functioning (p = .004), and fatigue (p = .020); CML‐CP (vs. CML‐AP) was associated with better emotional functioning (p = .026), insomnia (p = .007), and diarrhea (p = .004); achieving an MMR was associated with less nausea and vomiting (p = .024); and male sex was associated with better global health (p = .036). However, these covariates were not associated with improvements in HRQoL over time as the number of treatment cycles increased.

In addition, we performed separate analyses on patients in CML‐CP and CML‐AP. Among the patients in CML‐CP, the results were the same as in the previous analysis of all patients: physical functioning (p = .004), emotional functioning (p < .001), global health (p = .010), fatigue (p < .001), dyspnea (p = .004), diarrhea (p < .001), and financial difficulties (p < .001) improved during olverembatinib treatment. For the patients in CML‐AP, no items improved, whereas cognitive functioning (p = .018) and constipation (p = .016) worsened during olverembatinib treatment (Figure 2).

Regardless of whether the patients completed the 36‐month questionnaire survey, the results were the same as in the previous analysis of all patients: physical functioning (p = .007), emotional functioning (p < .001), global health (p = .006), fatigue (p < .001), dyspnea (p = .015), diarrhea (p < .001), and financial difficulties (p < .001) improved during olverembatinib treatment. In those who discontinued participation before completion of the study, nausea and vomiting (p = .015) improved during treatment, whereas constipation (p = .005) worsened during treatment.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression

At baseline

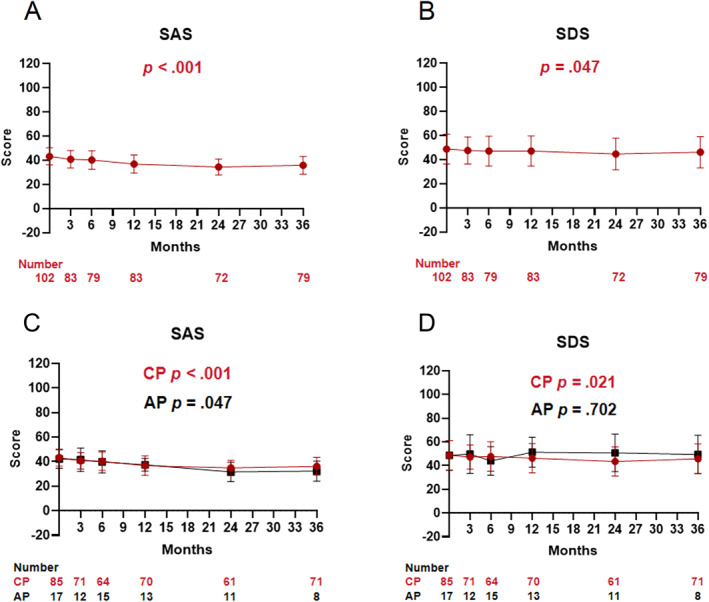

The SAS standard score of the 102 patients who completed the questionnaires before olverembatinib therapy was 43 ± 7 points. According to the guidelines set forth by the China Mental Health Center, 83 patients (82%) had no anxiety symptoms, and 18 patients (18%) and one patient (1%) experienced mild and moderate anxiety symptoms, respectively. The standard SDS score was 49 ± 12 points. Fifty‐six patients (55%) had no depression symptoms; and 35 (34%), nine (9%), and two (2%) patients experienced mild, moderate, and severe depression symptoms, respectively.

Univariate and multivariate general linear models were used to identify variables associated with SAS and SDS scores at baseline. In the multivariate analysis, an age younger than 40 years (vs. 40 years and older; p = .006) and an interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation <5 years (vs. ≥5 years; p = .023) were significantly associated with a lower SDS standard score. No variable affecting the SAS standard score at baseline was identified.

During olverembatinib therapy

At 36 months after the initiation of olverembatinib therapy, the SAS and SDS standard scores of the patients were 36 ± 7 and 46 ± 13 points, respectively. Seventy‐eight (95%) and 48 (59%) patients were free of anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms, respectively. Four patients (5%) had mild anxiety symptoms, 24 (29%) had mild depression symptoms, 10 (12%) had moderate depression symptoms, and two (2%) had severe depression symptoms.

Linear model analyses using the GEE based on the independent working correlation matrix revealed that the standard SAS score (p < .001) and the standard SDS score (p = .047) decreased significantly over time during olverembatinib therapy (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Changes in Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self‐Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores over time at each visit for the total population (A, B), for AP and CP patients (C, D) separately. AP indicates accelerated phase; CP, chronic phase.

To identify variables associated with changes in the SAS and SDS scores from baseline during olverembatinib therapy, the GEE, which included demographic characteristics (sex and age [younger than 40 years vs. 40 years and older]), disease phase (CML‐CP vs. CML‐AP), interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation (<5 years vs. ≥5 years), and treatment response (achieving an MMR, yes vs. no) at each visit during treatment were used. In the multivariate analysis, an age younger than 40 years (p = .014) and an interval from CML diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation <5 years (vs. ≥5 years; p = .047) were significantly associated with a lower SDS standard score during olverembatinib therapy, but these covariates were not correlated with improvements over time. No variable was associated with a change in the standard SAS score.

The standard SAS scores decreased significantly over time during olverembatinib therapy both in patients with CML‐CP and in those with CML‐AP (both p values < .001); however, the standard SDS score decreased significantly over time only in the CML‐CP group (p = .021), but not in the CML‐AP group (p = .702; Figure 3).

Regardless of whether patients completed the 36‐month questionnaire survey, the standard SAS scores decreased significantly over time during olverembatinib therapy (both p values < .001). In multivariate analysis of the patients who completed the 36‐month questionnaire survey, age younger than 40 years (vs. 40 years and older; p = .017) was significantly associated with a lower standard SDS score.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we focused on HRQoL, anxiety symptoms, and depression symptoms and analyzed the variables associated with these symptoms in patients with TKI‐resistant CML who were receiving olverembatinib. During 3 years of olverembatinib therapy, HRQoL and anxiety symptoms significantly improved in patients who had CML‐CP. Anxiety symptoms significantly decreased over time in both patients with CML‐CP and those with CML‐AP, including those who did and did not complete the 36‐month questionnaire survey.

Improvements in the HRQoL were associated with being in the CP stage of CML at baseline (vs. the AP stage), young age, harboring a T315I‐based BCR::ABL1 mutation, and having better emotional functioning at baseline. These associations may be attributed to patients being aware of the specific efficacy of olverembatinib in overcoming the T315I mutation. These findings were specific to olverembatinib therapy.

Previous studies have indicated a correlation between higher costs and poor HRQoL. 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 In this study, we observed that financial difficulties were the most serious burden reported by patients before and during the study. Since 2018, imatinib, nilotinib, and dasatinib have been partially reimbursed by medical insurance across China, and all patients involved in this study had been heavily treated, with a median interval from diagnosis to olverembatinib initiation of 5 years. Long‐term therapy and related costs, including frequent hospital visits for follow‐up care and a decrease in job opportunities and abilities because of illness, may result in a financial burden for some patients; although clinical trials provide free medication and testing, economic difficulties persist. Therefore, financial difficulties, one of the most common and severe symptom burdens before and during the study, are understandable.

Consistent with previous studies, 29 , 30 , 33 , 34 fatigue was a prominent symptom at baseline; a longer TKI therapy duration was associated with more severe depression symptoms at baseline, and male sex was associated with improved global health during olverembatinib therapy. Patients in a later line setting who were treated with asciminib in the ASCEMBL trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03106779) also presented with fatigue as the most common symptom at baseline, which improved during treatment, with no deterioration in CML‐specific symptoms or HRQoL in these patients. 14

An age younger than 40 years was associated with greater improvement in social functioning during olverembatinib therapy, which indicated that young patients who benefited from the treatment were investing more in social activities. In addition, younger age was associated with lower standard SDS scores at baseline, which decreased over time, and this is also consistent with the findings of a previous study indicating that younger patients have better mental health. 15

This study has several limitations. First, the study had a relatively small sample size. Second, not all patients in the clinical trials completed the questionnaires to assess anxiety and depression symptoms. Third, the patients were from clinical trials, and further studies are needed to determine the applicability of these conclusions in real‐world scenarios. Our patients were younger, and the structure of the health care system in China differed significantly from that in developed countries. Further investigation is needed to determine the applicability of our health care model to countries that have different health care systems.

We concluded that HRQoL significantly improved over time during olverembatinib therapy in heavily treated patients with TKI‐resistant CML‐CP. Younger age and being in the CP stage of CML rather than the AP stage were associated with improved HRQoL. Anxiety symptoms significantly decreased over time among patients with CML‐CP and those with CML‐AP, regardless of whether they completed the 36‐month questionnaire survey.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lu Yu: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, investigation, formal analysis, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, and project administration. Weiming Li: Data curation, investigation, writing–review and editing, and project administration. Na Xu: Writing–review and editing, data curation, investigation, and project administration. Xiaoli Liu: Investigation, data curation, writing–review and editing, and project administration. Bingcheng Liu: Data curation, project administration, writing–review and editing, and investigation. Yanli Zhang: Investigation, writing–review and editing, project administration, and data curation. Li Meng: Investigation, data curation, project administration, and writing–review and editing. Huanling Zhu: Investigation, data curation, project administration, and writing–review and editing. Xin Du: Investigation, data curation, project administration, and writing–review and editing. Suning Chen: Investigation, data curation, project administration, and writing–review and editing. Hu Yu: Investigation, writing–review and editing, data curation, and project administration. Yongping Song: Investigation, project administration, data curation, and writing–review and editing. Lichuang Men: Formal analysis, data curation, and writing–review and editing. Qian Jiang: Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, validation, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, resources, project administration, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, and funding acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Li Meng is an employee of Guangzhou Healthquest Pharma Company Ltd. and a stockholder in Ascentage Pharma Group International. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1

Table S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 81970140 and No. 82370161).

Yu L, Li W, Xu N, et al. Patient‐reported outcomes in adults with tyrosine kinase inhibitor‐resistant chronic myeloid leukemia receiving olverembatinib therapy. Cancer. 2025;e35652. doi: 10.1002/cncr.35652

Lu Yu, Weiming Li, and Na Xu contributed equally to this work as joint first authors.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data from this study may be made available upon reasonable request. Any request for data should be sent to the corresponding author with a detailed description of the research protocol. The corresponding author reserves the right to decide whether or not to share the data.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, et al. Long‐term outcomes of imatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(10):917‐927. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1609324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Saussele S, et al. Assessment of imatinib as first‐line treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia: 10‐year survival results of the randomized CML study IV and impact of non‐CML determinants. Leukemia. 2017;31(11):2398‐2406. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al. Final 5‐year study results of DASISION: the Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment‐Naive Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(20):2333‐2340. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.64.8899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bower H, Bjorkholm M, Dickman PW, Höglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TML. Life expectancy of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia approaches the life expectancy of the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2851‐2857. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.66.2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brummendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1825‐1833. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01589-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jiang Q, Li Z, Qin Y, et al. Olverembatinib (HQP1351), a well‐tolerated and effective tyrosine kinase inhibitor for patients with T315I‐mutated chronic myeloid leukemia: results of an open‐label, multicenter phase 1/2 trial. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01334-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla‐Ibarz J, et al. Ponatinib efficacy and safety in Philadelphia chromosome‐positive leukemia: final 5‐year results of the phase 2 PACE trial. Blood. 2018;132(4):393‐404. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-739086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cortes J, Apperley J, Lomaia E, et al. Ponatinib dose‐ranging study in chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a randomized, open‐label phase 2 clinical trial. Blood. 2021;138(21):2042‐2050. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Efficace F, Stagno F, Iurlo A, et al. Health‐related quality of life of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with first‐line dasatinib versus imatinib therapy. Leukemia. 2020;34(2):488‐498. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0563-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shacham AA, Shemesh S, Rosenmann L, et al. Health‐related quality of life in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with first‐ versus second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Med. 2020;9(11):3417. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Efficace F, Castagnetti F, Martino B, et al. Health‐related quality of life in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving first‐line therapy with nilotinib. Cancer. 2018;124(10):2228‐2237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Unnikrishnan R, Veeraiah S, Ganesan P. Symptom burden and quality of life issues among patients of chronic myeloid leukemia on long‐term imatinib therapy. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(2):165‐168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whiteley J, Reisman A, Shapiro M, Cortes J, Cella D. Health‐related quality of life during bosutinib (SKI‐606) therapy in patients with advanced chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib failure. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(8):1325‐1334. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2016.1174108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Réa D, Boquimpani C, Mauro MJ, et al. Health‐related quality of life of patients with resistant/intolerant chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia treated with asciminib or bosutinib in the phase 3 ASCEMBL trial. Leukemia. 2023;37(5):1060‐1067. doi: 10.1038/s41375-023-01888-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi D, Li Z, Li Y, Jiang Q. Variables associated with self‐reported anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;62(3):640‐648. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2020.1842397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kantarjian HM, Jabbour E, Deininger M, et al. Ponatinib after failure of second‐generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor in resistant chronic‐phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(11):1419‐1426. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dhillon S. Olverembatinib: first approval. Drugs. 2022;82(4):469‐475. doi: 10.1007/s40265-022-01680-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood. 2013;122(6):872‐884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-501569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Steegmann JL, Baccarani M, Breccia M, et al. European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management and avoidance of adverse events of treatment in chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2016;30(8):1648‐1671. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Silver RT, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2020 recommendations for treating chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34(4):966‐984. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0776-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cross N, Ernst T, Branford S, et al. European LeukemiaNet laboratory recommendations for the diagnosis and management of chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2023;37(11):2150‐2167. doi: 10.1038/s41375-023-02048-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng JX, Liu BL, Zhang X, et al. The validation of the standard Chinese version of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire 30 (EORTC QLQ‐C30) in pre‐operative patients with brain tumor in China. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang CC, Lien HH, Sung YC, Liu H, Chie W. Quality of life of patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan: validation and clinical application of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ‐C30 and EORTC QLQ‐STO22. Psychooncology. 2007;16(10):945‐949. doi: 10.1002/pon.1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ‐C30: a quality‐of‐life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(5):365‐376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371‐379. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(71)71479-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zung WW. A self‐rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12(1):63‐70. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leung KK, Lue BH, Lee MB, Tang LY. Screening of depression in patients with chronic medical diseases in a primary care setting. Fam Pract. 1998;15(1):67‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu XC, Oda S, Peng X, Asai K. Life events and anxiety in Chinese medical students. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32(2):63‐67. doi: 10.1007/bf00788922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jiang Q, Wang H, Yu L, Gale RP. Higher out‐of‐pocket expenses for tyrosine kinase‐inhibitor therapy is associated with worse health‐related quality‐of‐life in persons with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(12):2619‐2630. doi: 10.1007/s00432-017-2517-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Efficace F, Breccia M, Saussele S, et al. Which health‐related quality of life aspects are important to patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving targeted therapies and to health care professionals? GIMEMA and EORTC Quality of Life Group. Ann Hematol. 2012;91(9):1371‐1381. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1458-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, McNees P, Pisu M. Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):437‐443. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McGarry LJ, Chen YJ, Divino V, et al. Increasing economic burden of tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment failure by line of therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(2):289‐299. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1120189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hess G, Rule S, Jurczak W, et al. Health‐related quality of life data from a phase 3, international, randomized, open‐label, multicenter study in patients with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma treated with ibrutinib versus temsirolimus. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(12):2824‐2832. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2017.1326034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vachon H, Mierzynska J, Taye M, et al. Reference values for the EORTC QLQ‐C30 in patients with advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma and in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Eur J Haematol. 2021;106(5):697‐707. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Table S2

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study may be made available upon reasonable request. Any request for data should be sent to the corresponding author with a detailed description of the research protocol. The corresponding author reserves the right to decide whether or not to share the data.