Abstract

Sleep apnea is a global public health concern, but little research has examined this issue in low- and middle-income countries, including Samoa. The purpose of this study was to examine the sample prevalence and characteristics of sleep apnea using a validated home sleep apnea device (WatchPAT, Itamar) and explore factors that may influence sleep health in the Samoan setting. This study used data collected through the Soifua Manuia (“Good Health”) study, which investigated the impact of the body mass index (BMI)-associated genetic variant rs373863828 in CREBRF on metabolic traits in Samoan adults (sampled to overrepresent the obesity-risk allele of interest). A total of 330 participants had sleep data available. Participants (53.3 % female) had a mean (SD) age of 52.0 (9.9) years and BMI of 35.5 (7.5) kg/m2, and 36.3 % of the sample had type 2 diabetes. Based on the 3 % and 4 % apnea hypopnea indices (AHI) and the 4 % oxygen desaturation index (ODI), descriptive analyses revealed moderate to severe sleep apnea (defined as ≥15 events/hr) in 54.9 %, 31.5 %, and 34.5 % of the sample, respectively. Sleep apnea was more severe in men (e.g., AHI 3 % ≥15 in 61.7 % of men and 48.9 % of women). Correction for non-representational sampling related to the CREBRF obesity-risk allele resulted in only slightly lower estimates. Multiple linear regression linked a higher number of events/hr to higher age, male sex, higher BMI, higher abdominal-hip circumference ratio, and geographic region of residence. Further research and an increased focus on equitable and affordable diagnosis and access to treatment are crucial to addressing sleep apnea in Samoa and globally.

Keywords: Sleep apnea, Pacific islander, Sleep health, Sleep epidemiology

1. Introduction

Sleep apnea is a prevalent disorder characterized by recurring upper airway obstruction, resulting in reduced oxygen levels and fragmented sleep patterns. This condition has significant negative consequences for physical health, cognitive function, and overall quality of life [1]. Globally, sleep apnea affects an estimated 1 billion people, highlighting its importance as a public health issue [2]. Despite extensive research in high-income countries, there is a lack of robust data from low- and middle-income countries [3], including Samoa, which has a notably high prevalence of obesity [4,5] — one of the key risk factors for sleep apnea.

Research on sleep health in Pacific Islander populations is scarce, but existing studies suggest significant concerns. For instance, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. experience inadequate sleep and high daytime sleepiness [6,7], which may reflect underlying sleep pathology. Supporting this, a study of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander individuals in Utah found significant sleep apnea severity (and low treatment adherence) [8]. In New Zealand, Māori individuals show a higher prevalence of sleep apnea compared to non-Māori individuals [9]. It is worth noting that sleep apnea is an independent risk factor for mortality [10,11] but, fortunately, there are treatment interventions available that can reduce this risk. For example, Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) can be effective in not only improving sleep quality [12], but also reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [13,14] by enhancing glycemic control, reducing insulin resistance, improving fasting glucose, lowering hemoglobin A1c levels, and decreasing blood pressure [15,16].

These findings, combined with our previous work showing high rates of excessive daytime sleepiness in Samoan adults [17], underscore the need to examine sleep apnea’s prevalence and characteristics in Samoa. This study aims to address this gap by evaluating sleep apnea in this population and exploring culturally relevant factors that may influence sleep health.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study overview

This was a secondary analysis of data collected via the 2017–2019 Soifua Manuia (“Good Health”) study which aimed to investigate the impact of the CREB3 Regulatory Factor (CREBRF) genetic variant rs373863828 on metabolic traits in Samoan adults [18]. The variant’s minor allele (A) is paradoxically associated with increased body mass index (BMI), but lower odds of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in Pacific Islander individuals [19]. The overall sample included 519 participants from ‘Upolu, Samoa, with intentional oversampling of the CREBRF obesity-risk A allele at an approximate GG:AG:AA genotype ratio of 2:2:1 (compared with the expected population ratio of 8.2:5.7:1). All participants completed extensive physical assessments and comprehensive behavioral questionnaires. Objective sleep data were collected in a subset of 391 participants (as the assessment was added several months into the recruitment/data collection period). The study protocol and recruitment procedures are detailed elsewhere [18]. The study received approval from ethical boards at Yale University, Brown University, the University of Pittsburgh, Mass General Brigham, and the Samoa Ministry of Health. All participants gave written informed consent.

2.2. Phenotype data

Objective sleep data were collected using WatchPAT TM 200 Unified (Itamar Medical Ltd.) devices worn on the nondominant wrist. These highly accurate and clinically reliable devices measure peripheral arterial tone, heart rate, oxygen saturation, actigraphy, snoring levels, and body position via three points of contact (wrist, finger, and chest). Data for this study were reviewed and cleaned by trained sleep research polysomnologists (Methods S1). Unlike traditional polysomnography, WatchPAT does not rely on fixed time thresholds to define respiratory event durations. Instead, its proprietary algorithm analyzes multiple physiological parameters [20]. For this study, respiratory events were defined as a 30 % or greater peripheral arterial tone amplitude reduction together with a specific oxygen desaturation threshold (3 % or 4 %, details below). Despite this difference, the WatchPAT apnea-hypopnea and oxygen desaturation indices demonstrate an impressive 93 % to 99 % correlation when compared to the same metrics collected using the gold standard polysomnography [21].

In this study, we focused on three clinical indicators of sleep apnea: the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) using both 3 % and 4 % oxygen desaturation cutoffs, and the oxygen desaturation index (ODI) using a 4 % oxygen desaturation cutoff. Each measure provides distinct insights into sleep apnea severity, and their combined use ensures a comprehensive assessment of the condition in this novel population. The AHI quantifies the number of apneas (pauses in breathing) and hypopneas (partial reductions in breathing) per hour of sleep, based on reductions in blood oxygen levels of ≥3 % (AHI 3 %) or ≥4 % (AHI 4 %). The 3 % cutoff captures a broader range of events, including those that might be less severe but still clinically relevant. In contrast, the 4 % cutoff is more stringent and is widely used in clinical practice to diagnose moderate to severe sleep apnea. We chose to use both cutoffs to provide a nuanced characterization of sleep apnea severity and evaluate how different thresholds impact the classification within this specific population. Given that this is the first examination of sleep apnea in Samoan adults, this approach allowed us to place our findings within the context of existing literature and clinical practices. The ODI measures the frequency of ≥4 % oxygen desaturation events per hour (events/hr) of sleep, independent of apneas/hypopneas. This measure provides valuable information on the frequency and impact of significant oxygen desaturation events. Including the ODI helped us more fully characterize the data and align our findings with a broader range of sleep apnea measures reported in the literature.

To further support the descriptive nature of this paper, secondary measures included the AHI 3 %, AHI 4 %, and ODI 4 % across supine and non-supine sleep positions and rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM estimates of sleep states using the devices’ proprietary algorithm [22] as well as percent time spent below 90 % oxygen saturation (T90). Sleep apnea measures were examined as continuous events/hr and collapsed based on clinically accepted sleep apnea categories by number of events/hr (none/minimal: <5; mild: 5 to <15; moderate: 15 to < 30; and severe: ≥30) [23]. Finally, sleep apnea measures were also summarized in a “clinically actionable” moderate to severe category (≥15 events/hr).

AHI 3 % and 4 % and ODI 4 % distributions were examined by participant characteristics known to be associated with sleep apnea in other populations [24], as well as factors unique to the Samoan context that may influence sleep health. Age and sex were self-reported by participants. Weight and height were measured in duplicate using a digital scale (Tanita HD 351; Tanita Corporation of America) and portable stadiometer (SECA 213, Seca GmbH & Co), and BMI was computed from the averaged values. BMI was treated as continuous and categorical variables using Polynesian cutoffs for underweight (<18 kg/m2), ‘normal’ (18 to <26 kg/m2), overweight (26 to 32 kg/m2), and obesity (>32 kg/m2). Abdominal and hip circumference were measured using a standard tape measure (SECA 201, SECA, Hamburg, Germany) and abdominal-hip ratio was computed. CREBRF rs373863828 genotype data were generated via TaqMan real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems) [19]. T2DM status was determined based on any of the following: current use of diabetes medication; Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (5.7–6.4 %, pre-diabetes; >6.4 %, diabetes); fasting blood glucose (FBG; 100–125, pre-diabetes; ≥126, diabetes); and/or oral glucose tolerance testing based on the American Diabetes Association criteria [25]. Blood pressure (BP) was measured in triplicate and the second and third values were averaged; hypertension was defined as hypertension medication use or an average systolic BP ≥140 or average diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg. Participants self-reported asthma diagnoses. Behavioral and social data encompassed self-reported smoking habits (current use of cigarettes, tobacco, or pipe; yes/no), alcohol consumption in the past 12 months (yes/no), and socioeconomic resources quantified using a material lifestyle score [26] which sums the number of items owned from an 18-item household inventory (refrigerator, freezer, portable stereo/MP3 player, etc.). For participants with a low level (i.e., <35 %) of missing information across the household inventory questionnaire, imputation was used to fill in missing data [17]. Moderate-vigorous physical activity data (average minutes per day) were collected using Actigraph GT3X+ accelerometer-based devices (ActiGraph Corporation) as detailed elsewhere [27]. Finally, participants provided data about the night of the WatchPAT assessment related to sleep surface (e.g., mattress on a raised bed, mat on the floor, etc.), the number of people sharing the sleep surface, and the number of people sharing the room. WatchPAT assessment season (cool/dry vs. hot/wet) was inferred based on assessment date. These variables were also explored to comprehensively characterize the impact of these culturally unique factors on sleep apnea measures in this population.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Statistical and descriptive analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2 [28]. Data were described using means, standard deviations (SD), medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency counts and percentages for categorical variables. Categorical sleep apnea sample prevalence was calculated across the three primary sleep apnea measures (AHI 3 %, AHI 4 %, and ODI 4 %), including for supine/non-supine position and REM/non-REM cycles. To evaluate the influence of non-representational sampling and to obtain more accurate estimates of sleep apnea prevalence that might be seen in a random sample of the population, we performed a correction for CREBRF obesity-risk allele enrichment (Code S1). Specifically, we calculated genotype-specific weights by comparing the expected genotype frequencies in the general population with the observed genotype frequencies in our sample. Similar to inverse probability weighting, we then used the genotype-specific weights to adjust the counts of categorical sleep apnea severity (none, mild, moderate, severe).

To better understand AHI and ODI data distributions across the participant factors described above, various visualizations were employed including stacked bar, sina with violin, rain, scatter, and mosaic plots. Associations between sleep measures and participant factors were formally tested using Spearman correlation coefficients and Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests depending on the predictor variable type. Finally, multiple linear regression was used to examine associations of square root transformed (given data skewness) sleep apnea measures and a priori selected participant characteristics of age, sex, CREBRF genotype, BMI, abdominal-hip ratio, T2DM, hypertension, asthma, census region, relationship status, and cigarette and alcohol use. Unstandardized regression estimates, 95 % confidence intervals (CI), and p-values were reported, and model assessment was performed using residual analysis and influence diagnostics. Across all analyses, p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

After data cleaning and quality control, the WatchPAT sample consisted of 330 participants (53.3 % female) with a mean (±SD) age of 52.0 (±9.9) years and BMI of 35.5 (±7.5) kg/m2 (Table 1). No statistically significant differences were observed between the WatchPAT sample and the larger parent sample (Table S1).

Table 1.

Sample description and characteristics.

| Characteristic | Overall sample n = 330 |

Male n = 154 |

Female n = 176 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)1 | 52.0 (9.9) | 52.9 (10.0) | 51.2 (9.7) |

| Sex2 | |||

| Male | 154 (46.7) | ||

| Female | 176 (53.3) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2)1 | 35.5 (7.5) | 33.1 (6.3) | 37.6 (7.8) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Abdominal-hip ratio1 | 0.98 (0.07) | 0.99 (0.06) | 0.96 (0.06) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Type 2 Diabetes2 | |||

| None | 40 (12.2) | 20 (13.0) | 20 (11.5) |

| Pre-diabetes | 169 (51.5) | 82 (53.2) | 87 (50.0) |

| Diabetes | 119 (36.3) | 52 (33.8) | 67 (38.5) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Hypertension2 | |||

| No | 215 (66.6) | 107 (70.0) | 108 (63.5) |

| Yes | 108 (33.4) | 46 (30.0) | 62 (36.5) |

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| Asthma2 | |||

| No | 316 (95.8) | 144 (93.5) | 172 (97.7) |

| Yes | 14 (4.2) | 10 (6.5) | 4 (2.3 %) |

| CREBRF rs373863828 genotype2 | |||

| GG | 145 (43.9) | 71 (46.1) | 74 (42.0) |

| AG | 139 (42.1) | 65 (42.2) | 74 (42.0) |

| AA | 46 (13.9) | 18 (11.7) | 28 (16.0) |

| Census Region2 | |||

| Apia Urban Area | 68 (20.6) | 31 (20.1) | 37 (21.0) |

| Northwest ‘Upolu | 139 (42.1) | 66 (42.9) | 73 (41.5) |

| Rest of ‘Upolu | 123 (37.3) | 57 (37.0) | 66 (37.5) |

| Education (years)1 | 11.3 (2.9) | 10.9 (3.3) | 11.7 (2.4) |

| Relationship Status2 | |||

| Not partnered | 57 (17.3) | 25 (16.2) | 32 (18.2) |

| Partnered | 273 (82.7) | 129 (83.8) | 144 (81.8) |

| Alcohol2 | |||

| No | 305 (92.4) | 133 (86.4) | 172 (97.7) |

| Yes | 25 (7.6) | 21 (13.6) | 4 (2.3) |

| Smoking2 | |||

| No | 207 (62.9) | 78 (50.6) | 129 (73.7) |

| Yes | 122 (37.1) | 76 (49.4) | 46 (26.3) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Material Lifestyle Score (no. household assets)1 | 8.0 (4.1) | 7.9 (4.2) | 8.1 (3.9) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Moderate-vigorous physical activity (min/day)3 | 75.3 (88.6) | 83.0 (90.3) | 69.8 (74.1) |

| Missing | 39 | 20 | 19 |

| AHI 3 % (average events/hr)3 | 16.6 (17.9) | 19.0 (21.4) | 14.8 (15.0) |

| AHI 4 % (average events/hr)3 | 9.4 (13.9) | 10.9 (16.4) | 8.1 (11.5) |

| ODI 4 % (average events/hr)3 | 10.2 (14.9) | 12.0 (16.3) | 8.9 (11.9) |

| Categorical AHI 3 %2 | |||

| All categories | |||

| None/minimal sleep apnea (<5 events/hr) | 40 (12.1) | 18 (11.7) | 22 (12.5) |

| Mild (5 to <15 events/hr) | 109 (33.0) | 41 (26.6) | 68 (38.6) |

| Moderate (15 to<30 events/hr) | 114 (34.6) | 54 (35.1) | 60 (34.1) |

| Severe (≥30 events/hr) | 67 (20.3) | 41 (26.6) | 26 (14.8) |

| Clinical action category | |||

| Moderate to severe (≥15 events/hr) | 181 (54.9) | 95 (61.7) | 86 (48.9) |

| Categorical AHI 4 %2 | |||

| All categories | |||

| None/minimal sleep apnea (<5 events/hr) | 104 (31.5) | 46 (29.9) | 58 (33.0) |

| Mild (5 to <15 events/hr) | 122 (37.0) | 48 (31.2) | 74 (42.0) |

| Moderate (15 to<30 events/hr) | 69 (20.9) | 39 (25.3) | 30 (17.0) |

| Severe (≥30 events/hr) | 35 (10.6) | 21 (13.6) | 14 (8.0) |

| Clinical action category | |||

| Moderate to severe (≥15 events/hr) | 104 (31.5) | 60 (38.9) | 44 (25.0) |

| Categorical ODI 4 %2 | |||

| All categories | |||

| None/minimal sleep apnea (<5 events/hr) | 95 (28.8) | 43 (27.9) | 52 (29.5) |

| Mild (5 to <15 events/hr) | 121 (36.7) | 45 (29.2) | 76 (43.2) |

| Moderate (15 to<30 events/hr) | 74 (22.4) | 40 (26.0) | 34 (19.3) |

| Severe (≥30 events/hr) | 40 (12.1) | 26 (16.9) | 14 (8.0) |

| Clinical action category | |||

| Moderate to severe (≥15 events/hr) | 114 (34.5) | 66 (42.9) | 48 (27.3) |

| Total Sleep Time (hrs)1 | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.2) |

| Percent time spent <90 % oxygen saturation3 | 0.22 (1.84) | 0.39 (3.09) | 0.15 (1.36) |

| Categorical percent time spent <90 % oxygen saturation2 | |||

| No hypoxia (0 %) | 86 (26.1) | 36 (23.4) | 50 (28.4) |

| Light hypoxia (>0 to <5 %) | 201 (60.9) | 90 (54.4) | 111 (63.1) |

| Mild hypoxia (5 % to <10 %) | 16 (4.8) | 7 (4.5) | 9 (5.1) |

| Moderate hypoxia (10 % to <25 %) | 21 (6.4) | 18 (11.7) | 3 (1.7) |

| Severe hypoxia (≥25%) | 6 (1.8) | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.7) |

| Sleep Surface2 | |||

| Mattress on a raised bed | 75 (31.9) | 30 (26.3) | 45 (37.2) |

| Mattress on the floor | 39 (16.6) | 15 (13.2) | 24 (19.8) |

| Mat on the floor | 102 (43.4) | 56 (49.1) | 46 (38.0) |

| Bare floor | 14 (6.0) | 8 (7.0) | 6 (5.0) |

| Other4 | 5 (2.1) | 5 (4.4) | 0 (0 %) |

| Missing | 95 | 40 | 55 |

| Number of people sharing the sleep surface the night of the assessment2 | |||

| 1 | 88 (37.1) | 49 (42.6) | 39 (32.0) |

| 2 | 69 (29.1) | 31 (27.0) | 38 (31.1) |

| ≥35 | 80 (33.8) | 35 (30.4) | 45 (36.9) |

| Missing | 93 | 39 | 54 |

| Number of people who were sharing the room the night of the assessment2 | |||

| 1 | 70 (29.5) | 38 (33.0) | 32 (26.2) |

| 2 | 58 (24.5) | 25 (21.7) | 33 (27.1) |

| ≥35 | 109 (46.0) | 52 (45.2) | 57 (46.7) |

| Missing | 93 | 39 | 54 |

| Season2 | |||

| Cool and dry | 208 (63.0) | 93 (60.4) | 115 (65.3) |

| Hot and wet | 122 (37.0) | 61 (39.6) | 61 34.7) |

mean (SD)

n (%)

median (IQR)

carpet/floor/blanket/mat on sofa/sofa

ranges from 3 to 9

AUA = Apia Urban Area; NWU = Northwest ‘Upolu; ROU = Rest of ‘Upolu; AHI = apnea hypopnea index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; Hypertension, defined as an average value ≥140/90 mmHg and/or current hypertension medication use; Diabetes, Type 2 diabetes status was determined based on any of the following: current use of diabetes medication, Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (5.7–6.4 %, pre-diabetes; >6.4 %, diabetes), fasting blood glucose (FBG; 100–125, pre-diabetes; ≥126, diabetes), and/or oral glucose tolerance testing based on the American Diabetes Association criteria; Asthma, self-report history of asthma diagnosis; Smoking, defined based on self-report of current use of cigarettes, cigars, or pipes; Alcohol, defined based on self-report of consumption of alcohol in the past 12 months; Moderate-vigorous physical activity, average minutes/day measured using accelerometer.

Of the sample, 54.9 %, 31.5 %, and 34.5 % had moderate to severe sleep apnea (≥15 events/hr) based on the AHI 3 %, AHI 4 %, and ODI 4 %, respectively (Table 1); rates were higher among men (61.7 %, 38.9 %, and 42.9 %, respectively) vs. women (48.9 %, 25.0 %, and 27.3 %, respectively). Higher AHI and ODI scores were observed in supine (vs. non-supine) sleep positions and REM (vs. non-REM) sleep cycles (Table S2). For example, for the AHI 4 %, 41.4 % of the sample had moderate to severe sleep apnea in the supine position compared with only 20.7 % in the non-supine position. Likewise, 56.1% vs. 23.4 % had moderate to severe sleep apnea in REM vs. non-REM sleep, respectively.

Empirical correction to obtain prevalence estimates that better reflect the sleep apnea severity distribution that might be seen in the broader population, accounting for the overrepresentation of the CREBRF obesity-risk allele associated BMI inflation in the sample, revealed only small shifts in sleep apnea categories across the three measures (Table S3). Specifically, percentages in each sleep apnea category had a maximum shift of 1.6 %, and the estimated percentage of individuals with moderate to severe sleep apnea (≥15 events/hr) dropped by only 1 % to 1.5 % across the three measures, so CREBRF-adjusted prevalences were very similar to the raw frequencies shown in Table 1.

Despite the high AHI/ODI levels, depending on the measure, 23.4–28.4 % of the sample had no hypoxia (T90 of 0 %) and 54.4–63.1 % had only light hypoxia (T90 of >0 % to <5 %) (Table 1). As expected, greater hypoxia was observed in individuals with more severe sleep apnea (Table S4).

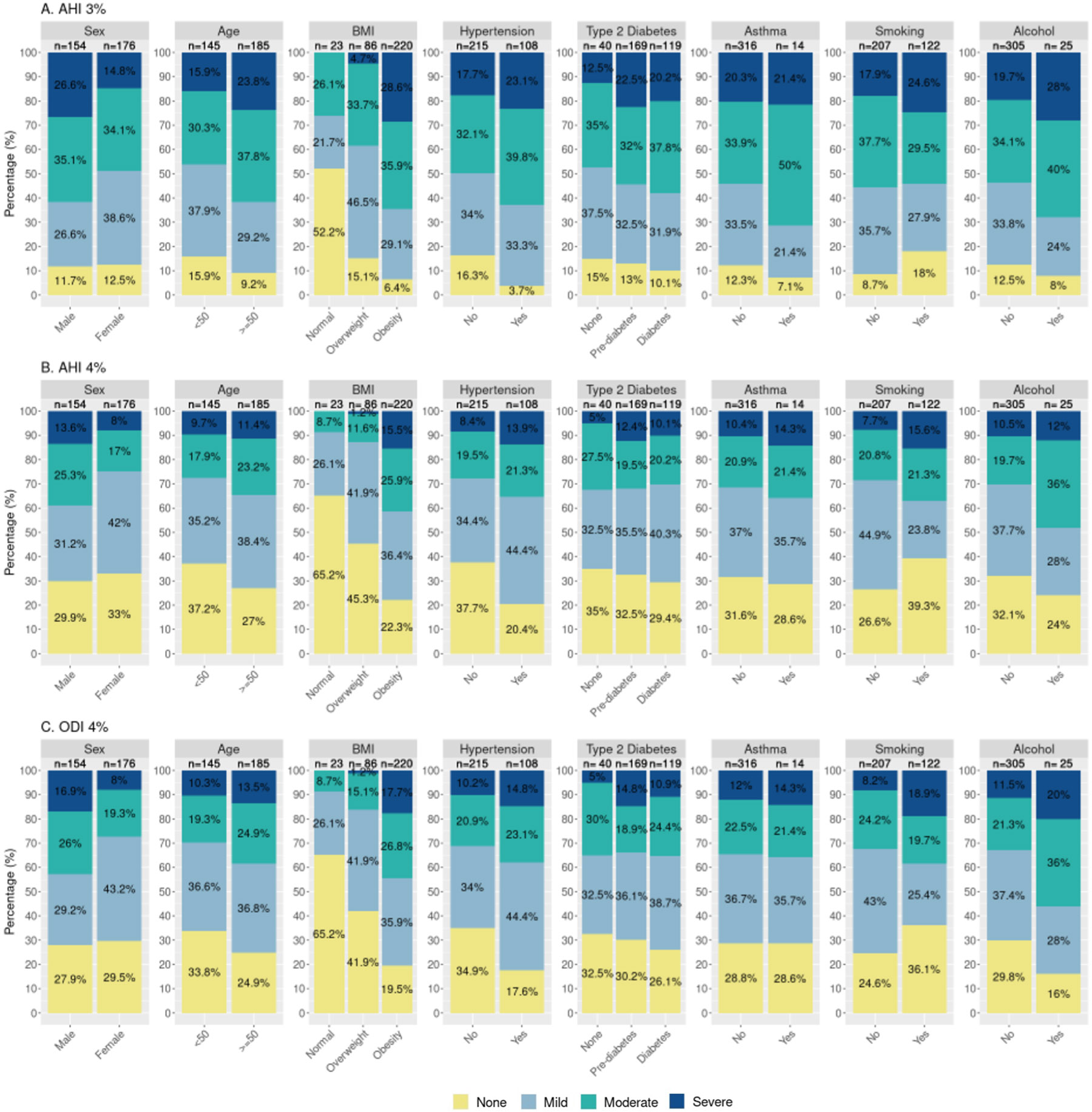

Stacked bar plots depict the distribution of categorical sleep apnea categories across a variety of different factors (Fig. 1). Consistent with the observed distributions seen in Fig. 1, a more detailed examination of the relationships between continuous (i.e., without collapsing) AHI/ODI data and categorical (Figures S1-S3) and continuous (Figure S4) participant factors showed that, across the AHI/ODI measures, a greater number of events/hr was associated with increased age (p = 0.002 to 0.10), BMI (p < 2.2e-16), abdominal-hip ratio (p = 1.1e-10 to 2.7e-10), and number of household assets (p = 0.002 to 0.035); lower physical activity levels (p = 0.016 to 0.031); male sex (p = 0.012 to 0.022); the presence of hypertension (p = 0.004 to 0.006); and CREBRF genotype (more copies of the A allele, p = 0.034 to 0.039). Exploratory analyses revealed that the association between sleep apnea measures and CREBRF genotype persisted when controlling for age, sex, and T2DM status (β=0.397 to 0.437, p = 0.001 to 0.028) but did not persist when controlling for age, sex, and BMI (β=0.085 to 0.096, p = 0.391 to 0.433) (Table S5). Exploratory mosaic plots (Figures S5-S8) depicting the proportional distribution of sleep apnea categories across a variety of factors support joint effects of sex, age, and BMI on sleep apnea severity.

Fig. 1. Stacked bar plots of sleep apnea measures by participant characteristics.

AHI = apnea hypopnea index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; None = <5 events/hr; Mild = 5–14.9 events/hr; Moderate = 15–29.9 events/hr; Severe = ≥30 events/hr. Age (years); BMI (kg/m2), ‘Normal’ = 18–25.99 kg/m2, Overweight = 26–32 kg/m2, Obesity = >32 kg/m2; Hypertension, defined as an average value ≥140/90 mmHg and/or current hypertension medication use; Diabetes, Type 2 diabetes status was determined based on any of the following: current use of diabetes medication; Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (5.7–6.4 %, pre-diabetes; >6.4 %, diabetes); fasting blood glucose (FBG; 100–125, pre-diabetes; ≥126, diabetes); and/or oral glucose tolerance testing based on the American Diabetes Association criteria; Asthma, self-report history of asthma diagnosis; Smoking, defined based on self-report of current use of cigarettes, cigars, or pipes; Alcohol, defined based on self-report of consumption of alcohol in the past 12 months; see Figures S1 and S2 for additional descriptive plots.

Finally, the results of linear regression examining associations of square root-transformed sleep apnea with a priori selected participant characteristics (age, sex, CREBRF genotype, BMI, abdominal-hip circumference ratio, T2DM status, hypertension status, asthma status, census region of residence, relationship status, socioeconomic resources, education, cigarette use, and alcohol use) are presented (Table 2). We observed associations between higher AHI/ODI levels and higher age (, p = 0.001 to 0.002); male sex ( to 0.979, p = 1.52E-07 to 7.99E-08); higher BMI ( to 0.136, p = 6.16E-21 to 9.35E-19); higher abdominal-hip circumference ratio ( to 2.923, p = 0.016 to 0.033); and residence in NWU vs AUA ( to 0.442 p = 0.037 to 0.052) while controlling for covariates.

Table 2.

Results of linear regression examining associations between square root-transformed sleep apnea indices and participant characteristics (n = 319).

| Term | AHI 3 % | AHI 4 % | ODI 4 % | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5th | 97.5th | p | 2.5th | 97.5th | p | 2.5th | 97.5th | p | ||||

| Age | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.049 | 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.011 | 0.048 | 0.002 |

| Sex, Female (Ref=Male) | −0.884 | −1.224 | −0.543 | 6.30E-07 | −0.949 | −1.295 | −0.603 | 1.52E-07 | −0.979 | −1.328 | −0.631 | 7.99E-08 |

| CREBRF genotype | 0.117 | −0.104 | 0.338 | 0.302 | 0.123 | −0.102 | 0.348 | 0.285 | 0.122 | −0.105 | 0.348 | 0.293 |

| BMI | 0.124 | 0.099 | 0.150 | 9.35E-19 | 0.136 | 0.109 | 0.162 | 6.16E-21 | 0.134 | 0.108 | 0.161 | 2.32E-20 |

| Abdominal-hip circumference ratio | 2.923 | 0.330 | 5.515 | 0.028 | 2.875 | 0.237 | 5.512 | 0.033 | 3.291 | 0.632 | 5.950 | 0.016 |

| Pre-Type 2 Diabetes (Ref=No diabetes) | 0.238 | −0.253 | 0.730 | 0.343 | 0.224 | −0.275 | 0.724 | 0.379 | 0.223 | −0.281 | 0.727 | 0.387 |

| Type 2 Diabetes (Ref=No diabetes) | 0.024 | −0.509 | 0.557 | 0.929 | 0.037 | −0.505 | 0.579 | 0.894 | 0.021 | −0.526 | 0.567 | 0.941 |

| Hypertension (Ref=No hypertension) | 0.156 | −0.190 | 0.503 | 0.377 | 0.122 | −0.231 | 0.475 | 0.498 | 0.148 | −0.207 | 0.504 | 0.415 |

| Asthma (Ref=No asthma) | 0.144 | −0.626 | 0.913 | 0.714 | −0.064 | −0.846 | 0.719 | 0.874 | −0.103 | −0.892 | 0.686 | 0.798 |

| Census region, NWU (Ref=AUA) | 0.403 | −0.001 | 0.807 | 0.052 | 0.427 | 0.016 | 0.839 | 0.042 | 0.442 | 0.028 | 0.857 | 0.037 |

| Census region, ROU (Ref=AUA) | −0.021 | −0.434 | 0.391 | 0.919 | 0.029 | −0.391 | 0.448 | 0.894 | 0.025 | −0.398 | 0.448 | 0.907 |

| Partnered (Ref=Not partnered) | −0.123 | −0.527 | 0.280 | 0.550 | −0.158 | −0.569 | 0.253 | 0.452 | −0.178 | −0.592 | 0.236 | 0.400 |

| Socioeconomic resources | 0.013 | −0.027 | 0.053 | 0.511 | 0.028 | −0.013 | 0.069 | 0.176 | 0.031 | −0.010 | 0.072 | 0.144 |

| Education | −0.020 | −0.080 | 0.040 | 0.521 | −0.016 | −0.077 | 0.045 | 0.610 | −0.016 | −0.077 | 0.046 | 0.612 |

| Cigarette use (Ref=No) | −0.179 | −0.503 | 0.146 | 0.282 | −0.086 | −0.416 | 0.245 | 0.611 | −0.091 | −0.424 | 0.242 | 0.593 |

| Alcohol use (Ref=No) | 0.174 | −0.423 | 0.772 | 0.568 | 0.193 | −0.415 | 0.800 | 0.534 | 0.222 | −0.391 | 0.834 | 0.479 |

= regression estimate for square root transformed dependent variable (sleep apnea measure).

2.5th = lower bound of 95 % confidence interval for ; 97.5th = upper bound of 95 % confidence interval for .

Bolded p-values indicate p < 0.05, underlined p-values indicate p < 0.1.

AHI = apnea hypopnea index; ODI = oxygen desaturation index; CREBRF rs373863828 genotype modeled additively based on number of copies of minor allele; BMI = body mass index (kg/m2); Pre-T2DM and T2DM = Type 2 diabetes status determined based on any of the following: current use of diabetes medication, Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) (5.7–6.4 %, pre-diabetes; >6.4 %, diabetes), fasting blood glucose (FBG; 100–125, pre-diabetes; ≥126, diabetes), and/or oral glucose tolerance testing based on the American Diabetes Association criteria; Hypertension, defined as an average blood pressure value ≥140/90 mmHg and/or current hypertension medication use; Asthma, based on self-report history of asthma diagnosis; Partnered = currently married or cohabitating (vs. not partnered = never married, separated, divorced, or widowed); Socioeconomic resources measured based on the number of household assets as a measure of material lifestyle score/socioeconomic position; Education, self-reported years of education; Smoking, defined based on self-report of current use of cigarettes, cigars, or pipes; Alcohol, defined based on self-report of consumption of alcohol in the past 12 months.

Discussion

Our study highlights a high prevalence of sleep apnea in this sample of adults from Samoa, emphasizing the urgency of addressing this public health issue. We found that 54.9 % of the sample had moderate to severe sleep apnea with ≥15 events/hr based on the AHI 3 % metric. This exceeds values reported in a previous study [2], which estimated (based only on population similarity to other areas with similar BMI and geographical proximity) lower expected prevalence rates in Samoa of 14.7 % by similar definition [2].

Beyond this work, only two other research papers have focused on sleep health in Samoa. The first study, conducted in 2009, examined the relationship between sleep apnea treatment and blood pressure reduction among adults from Samoa [16]. The researchers found that sleep apnea treatment by CPAP resulted in a 12.9/10.5 mm Hg reduction in BP over a 6-month period in the overall group, with an even greater reduction of 21.5/13.1 mm Hg in the baseline hypertensive group [16]. This study highlights the effectiveness of CPAP in reducing cardiovascular morbidity risk factors in this population. As mentioned above as an underlying motivation for this follow up study, the second paper was from our own group and characterized self-reported daytime sleepiness and insomnia in the same sample of adults from Samoa as this study and found a generally higher sample prevalence of excessive daytime sleepiness, but lower sample prevalence of insomnia compared with individuals from high-income countries [17].

To our knowledge there are no other studies focused on sleep apnea in Samoa. Direct comparisons with other populations need to be done cautiously due to the influences of age, sex, BMI, T2DM distributions, social determinants of health, and cultural differences on sleep apnea measures as well as the influences of sleep apnea measurement differences themselves. However, to put these findings in the context of existing research, the frequency of moderate to severe (≥15 events/hr) sleep apnea in the current study (AHI 3 % of 54.9 %) was higher than in the US-based Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). The MESA study, which measured sleep apnea (AHI 3 %) but using polysomnography across a variety of racial/ethnic groups, found the following rates: White (30.3 %), Black (32.4 %), Hispanic (38.2 %), and Chinese (39.4 %) [29]. Further comparisons can be made with a US-based sample of Mexican American adults from Starr County, Texas, who differ significantly from Samoans in environment and culture but share similarities in age range, technology (WatchPAT), and a high prevalence of T2DM. In the Starr County sample, 52.5 % of men and 48.1 % of women (all with T2DM) had moderate to severe sleep apnea [30]. In contrast, within the current Samoan sample, where only 36.5 % had T2DM, the rates were higher in men (61.7 %) and similar in women (48.9 %). Finally, in a high-risk group of African-Americans living in the southeastern U.S. (the Jackson Heart Sleep Study; mean age 63 years, 66 % female, mean BMI 32 kg/m2), the prevalence of moderate to severe sleep apnea (AHI 4 % ≥15) was 23.6 % measured via an in-home Embletta-Gold sleep apnea test [31]. These figures were also lower than the rate observed in this study, which found a sample rate of 31.5 % by the same metric.

Compared with other studies, we identified similar associations between AHI and ODI measures and participant factors such as male sex [32,33], higher BMI [33], higher age [33], an abdominal-hip circumference ratio [34]. In bivariate analyses, we also identified associations previously noted in the literature, including those with higher AHI/ODI measures and more socioeconomic resources [35], less physical activity [36], and the presence of hypertension [37]. Of note, we also identified associations with CREBRF genotype – though this association did not persist when controlling for BMI. Interestingly, we identified no associations between sleep apnea measures and T2DM status in this sample despite strong associations reported in prior work [38,39]. This null association persisted even when T2DM categories of pre-diabetes and diabetes were collapsed and treated as binary (explored based on graphical distribution shown in Figure S1). While we hypothesize this may be due to the saturation of overweight/obesity in this sample and/or the protective glycemic effect of the CREBRF obesity-risk allele, this is purely speculative and additional research is needed to understand this observation. We also did not identify associations between sleep apnea and unique environmental/lifestyle variables including sleep surface, season of assessment, or room/sleep surface sharing. Given the paucity of research concerning Pacific Islanders, coupled with the alarming evidence (presented above) that points toward a disproportionate burden of sleep issues in this group, it is evident that prioritizing sleep health research within this historically underrepresented group is imperative. This will enable a more comprehensive understanding of how age, sex, BMI, T2DM, social determinants of health, and cultural factors collectively impact sleep apnea measurements and their implications for cardiometabolic health.

While there are many strengths to this study, including that it provides one of the first examinations of sleep apnea in Samoa using clinically reliable devices, the sample ascertainment bias that resulted from intentional oversampling of the CREBRF obesity-risk allele potentially reduces the generalizability of our findings as a product of a moderately upwardly biased sample mean BMI. Specifically, the frequency of the CREBRF minor allele (A) in our sample was 0.561 compared with a lower frequency of 0.259 in the general Samoan population [19]. The sample mean BMI of the present study, 35.5 kg/m2, was higher than that from the larger more generally representative (but earlier) 2010 sample of 33.5 kg/m2 [19]. Of note, the participants for this study were recruited through the earlier 2010 study, so this increase in BMI is likely a product of not only CREBRF obesity-risk allele overrepresentation, but also year-on-year effects associated with aging and nutritional transition. However, even after adjusting for CREBRF-related sample ascertainment bias (Code S1), the sleep apnea category distributions shift by only 1–2 % (Table S3). Further, we don’t believe that the rates of sleep apnea in this sample are fully explained by obesity. In a sub-analysis of individuals with a BMI <30 kg/m2 (n = 73), a substantial 27.3 % exhibited an AHI 3 % ≥15 events/hr. This underscores the need for further research to better understand the role of not just body size, but also other factors on the development of this condition, as well as on the generalizability of findings.

Given the distribution of sleep apnea data in this study sample, there is a compelling need for further research dedicated to confirming these findings and exploring sleep apnea subtypes/endotypes. Most immediately, however, these data suggest a need for public health planning and policies geared toward the diagnosis and provision of accessible, cost-effective sleep apnea treatment options in Samoa. With the closure of a local sleep clinic in 2020 and a reported lack of CPAP machines locally, individuals suspected of having sleep apnea must currently seek screening and treatment in New Zealand or Australia. Prioritizing the development of healthcare infrastructure specifically focused on sleep-related issues is imperative. A concerted effort, integrating public health initiatives, improved medical accessibility, and dedicated research, is needed to mitigate the impact of sleep apnea in Samoa and foster a healthier future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for their involvement in this research as well as the local village authorities, the Samoa Ministry of Health, the Samoa Bureau of Statistics, and the Ministry of Women, Community and Social Development for their support of this work. A special fa’afetai tele lava to our research assistants – Melania Selu, Vaimoana Lupematisila, Folla Unasa, and Lupesina Vesi. Finally, we would like to thank the Editor and anonymous peer reviewers who took the time to review this paper as their feedback improved the clarity and quality of our work.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award numbers R01HL093093, R01HL133040, and K99HD107030. The sleep studies and SR were partially funded by R35135818. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Yale and Brown Universities, with Yale University serving as the IRB of record (1604017547). Data analysis activities at the University of Pittsburgh were reviewed by their IRB and were determined to be exempt (PRO16040077) based on their receipt of only deidentified data. Activities of the Sleep Reading Center were approved by Mass General Brigham (formerly Partners Healthcare). The study was also approved by the Health Research Committee of the Samoa Ministry of Health.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Availability of data

dbGAP accession #phs000914.v1.p1.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies

In the revision of this work, ChatGPT 4o and Google Gemini were utilized to provide feedback on sections of this paper to improve the readability and language. After using these tools, the authors carefully reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Lacey W. Heinsberg: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Alysa Pomer: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Brian E. Cade: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Jenna C. Carlson: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Take Naseri: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Muagututia Sefuiva Reupena: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Satupa’itea Viali: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Daniel E. Weeks: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. Stephen T. McGarvey: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Susan Redline: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Nicola L. Hawley: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Lacey Heinsberg, Jenna Carlson, Brian Cade, Daniel Weeks, Stephen McGarvey, Susan Redline, and Nicola Hawley report funding from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of this study.

Susan Redline reports grants and personal fees from Jazz Pharma, personal fees from Eisai Inc, and personal fees from Eli Lilly outside of the submitted work.

The funders had no role in the design of the study; collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or decision to publish the results.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.sleepe.2024.100099.

References

- [1].Osman AM, Carter SG, Carberry JC, Eckert DJ. Obstructive sleep apnea: current perspectives. Nat Sci Sleep 2018;10:21–34. 10.2147/NSS.S124657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Benjafield AV, Ayas NT, Eastwood PR, et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7(8):687–98. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Roche J, Rae DE, Redman KN, et al. Sleep disorders in low- and middle-income countries: a call for action. J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17(11):2341–2. 10.5664/jcsm.9614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390(10113):2627–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hawley NL, Minster RL, Weeks DE, et al. Prevalence of adiposity and associated cardiometabolic risk factors in the Samoan genome-wide association study. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26(4):491–501. 10.1002/ajhb.22553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Matthews EE, Li C, Long CR, Narcisse MR, Martin BC, McElfish PA. Sleep deficiency among Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Black, and White Americans and the association with cardiometabolic diseases: analysis of the National Health Interview Survey Data. Sleep Health 2018;4(3):273–83. 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Young MC, Gerber MW, Ash T, Horan CM, Taveras EM. Neighborhood social cohesion and sleep outcomes in the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander National Health Interview Survey. Sleep 2018;41(9). 10.1093/sleep/zsy097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Locke BW, Sundar DJ, Ryujin D. Severity, comorbidities, and adherence to therapy in Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med 2023;19(5):967–74. 10.5664/jcsm.10472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mihaere KM, Harris R, Gander PH, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea in New Zealand adults: prevalence and risk factors among Māori and non-Māori. Sleep 2009;32(7): 949–56. 10.1093/sleep/32.7.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Marshall NS, Wong KKH, Liu PY, Cullen SRJ, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton health study. Sleep 2008;31(8): 1079–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fu Y, Xia Y, Yi H, Xu H, Guan J, Yin S. Meta-analysis of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea with or without continuous positive airway pressure treatment. Sleep Breath 2017;21(1): 181–9. 10.1007/s11325-016-1393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Engleman HM, Asgari-Jirhandeh N, McLeod AL, Ramsay CF, Deary IJ, Douglas NJ. Self-reported use of CPAP and benefits of CPAP therapy: a patient survey. Chest 1996; 109(6): 1470–6. 10.1378/chest.109.6.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gervès-Pinquié C, Bailly S, Goupil F, et al. Positive airway pressure adherence, mortality, and cardiovascular events in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;206(11):1393–404. 10.1164/rccm.202202-0366OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Agossou M, Awanou B, Inamo J, Dufeal M, Arnal JM, Dramé M. Association between Previous CPAP and comorbidities at diagnosis of obesity-hypoventilation syndrome associated with obstructive sleep apnea: a comparative retrospective observational study. J Clin Med 2023;12(7). 10.3390/jcm12072448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shang W, Zhang Y, Wang G, Han D. Benefits of continuous positive airway pressure on glycaemic control and insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes and obstructive sleep apnoea: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2021;23(2):540–8. 10.1111/dom.14247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Middleton S, Vermeulen W, Byth K, Sullivan CE, Middleton PG. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea in Samoa progressively reduces daytime blood pressure over 6 months. Respirology 2009;14(3):404–10. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Heinsberg LW, Carlson JC, Pomer A, et al. Correlates of daytime sleepiness and insomnia among adults in Samoa. Sleep Epidemiol 2022;2:100042. 10.1016/j.sleepe.2022.100042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hawley NL, Pomer A, Rivara AC, et al. Exploring the paradoxical relationship of a Creb 3 regulatory factor missense variant with body mass index and diabetes among samoans: protocol for the soifua manuia (Good Health) observational cohort study. JMIR Res Protoc 2020;9(7):e17329. 10.2196/17329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Minster RL, Hawley NL, Su CT, et al. A thrifty variant in CREBRF strongly influences body mass index in Samoans. Nat Genet 2016;48(9):1049–54. 10.1038/ng.3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ayas NT, Pittman S, MacDonald M, White DP. Assessment of a wrist-worn device in the detection of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med 2003;4(5):435–42. 10.1016/s1389-9457(03)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pang KP, Gourin CG, Terris DJ. A comparison of polysomnography and the WatchPAT in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007;137(4):665–8. 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang Z, Sowho M, Otvos T, et al. A comparison of automated and manual sleep staging and respiratory event recognition in a portable sleep diagnostic device with in-lab sleep study. J Clin Sleep Med 2020;16(4):563–73. 10.5664/jcsm.8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].The international classification of sleep disorders. American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. 3rd ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(8):893–900. 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Association AD. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care 2017;41(Supplement_1):S13–27. 10.2337/dc18-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Choy CC, Hawley NL, Naseri T, Reupena MS, McGarvey ST. Associations between socioeconomic resources and adiposity traits in adults: evidence from Samoa. SSM Popul Health 2020;10:100556. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hawley NL, Zarei P, Crouter SE, et al. Accelerometer-based estimates of physical activity and sedentary time among samoan adults. J Phys Act Health 2024;21(7): 636–44. 10.1123/jpah.2023-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Published online 2021. https://www.R-project.org/.

- [29].Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep 2015;38(6):877–88. 10.5665/sleep.4732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hanis CL, Redline S, Cade BE, et al. Beyond type 2 diabetes, obesity and hypertension: an axis including sleep apnea, left ventricular hypertrophy, endothelial dysfunction, and aortic stiffness among Mexican Americans in Starr County, Texas. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2016;15:86. 10.1186/s12933-016-0405-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Johnson DA, Guo N, Rueschman M, Wang R, Wilson JG, Redline S. Prevalence and correlates of obstructive sleep apnea among African Americans: the jackson heart sleep study. Sleep 2018;41(10). 10.1093/sleep/zsy154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wahner-Roedler DL, Olson EJ, Narayanan S, et al. Gender-specific differences in a patient population with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Gend Med 2007;4(4):329–38. 10.1016/s1550-8579(07)80062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Johnson KG, Johnson DC, Thomas RJ, Rastegar V, Visintainer P. Cardiovascular and somatic comorbidities and sleep measures using three hypopnea criteria in mild obstructive sleep-disordered breathing: sex, age, and body mass index differences in a retrospective sleep clinic cohort. J Clin Sleep Med 2020;16(10): 1683–91. 10.5664/jcsm.8644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lim YH, Choi J, Kim KR, et al. Sex-specific characteristics of anthropometry in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: neck circumference and waist-hip ratio. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2014;123(7):517–23. 10.1177/0003489414526134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Papadopoulos D, Kikemeni A, Skourti A, Amfilochiou A. The influence of socioeconomic status on the severity of obstructive sleep apnea: a cross-sectional observational study. Sleep Sci 2018;11(2):92–8. 10.5935/1984-0063.20180018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hall KA, Singh M, Mukherjee S, Palmer LJ. Physical activity is associated with reduced prevalence of self-reported obstructive sleep apnea in a large, general population cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med 2020;16(7):1179–87. 10.5664/jcsm.8456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Brown J, Yazdi F, Jodari-Karimi M, Owen JG, Reisin E. Obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: updates to a critical relationship. Curr Hypertens Rep 2022;24(6): 173–84. 10.1007/s11906-022-01181-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yu Z, Cheng JX, Zhang D, Yi F, Ji Q. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a dose-response meta-analysis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021;2021:1337118. 10.1155/2021/1337118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Fallahi A, Jamil DI, Karimi EB, Baghi V, Gheshlagh RG. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2019;13(4):2463–8. 10.1016/j.dsx.2019.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.