Abstract

Background:

Childhood maltreatment can affect subsequent social relationships, including different facets of peer relationships. Yet, how prior maltreatment shapes adolescents’ connections within school peer networks is unclear, despite the rich literature showing the importance of this structural aspect of social integration in adolescence.

Objectives:

This study examines how childhood physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect predict adolescent social network structure as withdrawal, avoidance, and fragmentation among peers.

Participants and Setting:

Data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) Waves I, III, and IV yield a sample of 9,154 respondents with valid network data and survey of childhood maltreatment.

Methods:

Models using linear regression examine childhood maltreatment predicting withdrawal, avoidance, and fragmentation in adolescent peer networks. Maltreatment is first measured as ever occurring, then separately by maltreatment type.

Results:

Results indicate that experiencing any maltreatment leads to withdrawal (lower sociality, B= −0.214, p= 0.008), avoidance (lower popularity, B= −0.222, p= 0.007), and fragmentation (lower cohesion, B=−0.009, p<.001). However, different types of maltreatment are associated with different dimensions of peer networks, with only physical neglect impacting all three dimensions.

Conclusions:

Experiencing any maltreatment in childhood predicts lower integration in the adolescent peer network structure across three dimensions. However, distinct types of maltreatment relate differently to separate network dimensions, with sexual abuse predicting withdrawal, emotional and physical abuse predicting avoidance and fragmentation, and physical neglect predicting lower integration on all three dimensions.

Keywords: Childhood Maltreatment, Peer Networks, Adolescence

1. Introduction

Maltreatment, often perpetrated by a parent or other caregiver, includes experiences of both abuse (physical, sexual, or emotional) and neglect (Warmingham et al., 2019) which present major threats to a secure and stable childhood. The wide-ranging impact of maltreatment has been studied extensively, indicating risks to psychopathological (Bennett et al., 2010; Berzenski & Yates, 2011; Cicchetti, 2016; McLaughlin et al., 2020), emotional (Poole et al., 2018; Warmingham et al., 2019), and social development (Cicchetti, 2016; Trickett et al., 2011; Trickett & Negriff, 2011).

When considering social development in the early life course, typically, children who experience secure and healthy connections with parents and caregivers successfully age into adolescence, shift focus from parents to peers, and hone age-appropriate social skills and social efficacy through these peer relationships (Crosnoe et al., 2018; Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011; Haslam & Taylor, 2022). However, children who lack security and stability, or are otherwise exposed to threats in childhood, may have difficulty in developmentally vital peer relationships during this stage of the life course. Such challenges are of particular concern, as adolescence is a key developmental stage when connections with school peers become highly salient, affecting identity development, behavior, and well-being as individuals age through and beyond adolescence (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011; Kamis & Copeland, 2020).

Different aspects of peer relations relate to maltreatment. Studies have examined peer likability (Bolger & Patterson, 2001), neglect and rejection (Dodge et al., 1994), deviant peer affiliation (Yoon et al., 2021), victimization (Benedini et al., 2016), isolation (Christ et al., 2017), online social media networks (Negriff & Valente, 2018), and teachers’ perceptions of peer status (Yoon et al., 2018). Yet, little research considers how maltreatment impacts the structure of social connections (Green et al., 2012), a related but distinct measure of peer relationships in adolescence, best analyzed through the social networks perspective. The social networks perspective captures the fundamental structural components underlying social interaction, connection, and integration through multiple individuals’ perspectives to highlight the web of social connections in a setting (Carr, 2018; Cotterell, 2007). Here, we provide a novel application of the social networks perspective to the study of childhood maltreatment, examining how abuse and neglect relate to distinct dimensions of peer network structure: sociality, popularity, and cohesion, with lower levels of these dimensions conceptually indicating social processes of withdrawal, avoidance, and fragmentation, respectively.

1.1. Maltreatment and Peer Networks

Studies focusing on the social consequences of maltreatment hypothesize several pathways through which maltreatment affects how youth connect to peers. For example, abuse and neglect affect social cognition, leading maltreated children to have difficulties perceiving, interpreting, and responding to social stimuli and processing social information (Crawford et al., 2022). Maltreatment also leads to challenges in emotional regulation and secure attachment (Cicchetti, 2016; Crosnoe et al., 2018), with poor emotional regulation increasing peer rejection (Trickett et al., 2011) and insecure attachment leading to difficulties in accurately appraising social interactions and relationships (Giordano, 2003). Children experiencing maltreatment also face difficulty developing an autonomous self-identity, which can lead to negative self-esteem (Cicchetti, 2016). Research describes these cascading effects of maltreatment on social cognition, emotional regulation, attachment, and autonomy (Cicchetti, 2016; Yoon et al., 2023), linking maltreatment to reduced peer relations and interpersonal functioning in adolescence (Haslam & Taylor, 2022; Negriff & Valente, 2018; Trickett et al., 2011).

However, research has yet to examine how maltreatment influences the structure of peer relationships. In the social networks perspective, relationships in a setting create a network of interconnections. Positions within that structure of network ties affect a wide range of outcomes, independent from effects of other facets of relationships, like relational quality, personal characteristics, self-perceptions of peer acceptance and likability, or specific behaviors like bullying (Crosnoe, 2000). Sociocentric, or global, peer network structure contains information about both direct and indirect connections, representing information from multiple perspectives (Carr, 2018; Valente, 2010) that is more reliable than self-reports, which tend to overestimate peers’ deviance and similarity to respondents’ own behaviors and beliefs (Brown & Larson, 2009). Within the social networks perspective, different dimensions of network structure have different conceptual and empirical implications (Falci & McNeely, 2009; Forster et al., 2015). Although these dimensions of networks can be correlated, they differ in how they are shaped by other social factors and their subsequent effects on well-being (Copeland & Kamis, 2022; Kamis & Copeland, 2020). While a robust literature shows that many different aspects of peer networks and network structure matter for youth, here we examine three dimensions that represent basic building blocks of network structure that have been shown to relate to youth well-being (Copeland & Kamis, 2022; Kamis & Copeland, 2020; Kornienko & Santos, 2014; Tomlinson et al., 2021), providing a foundational first look at how maltreatment relates to peer network integration. We focus on sociality, popularity, and cohesion.

First, sociality, meaning the number of peers named as friends by the focal individual, relates to how an individual sees themselves in the overall social environment, indicating a sense of belonging among peers or successful attempts to connect to peers (Forster et al., 2015; Kamis & Copeland, 2020). Compared to youth without histories of abuse or neglect, maltreated youth often have a lower sense of belonging among peers and lower self-esteem, which may hinder reaching out to develop friendships, or lead to seeing themselves as less connected within the peer social environment (Feiring et al., 2000; Sani et al., 2020). Individuals who have experienced maltreatment, and subsequent insecure attachment, are also less likely to explore their social environments or may feel shame, nervousness, or anticipated stigma surrounding their maltreatment, further reducing attempts to initiate friendships (Elliott et al., 2005). Thus, maltreatment may lead to lower sociality, suggesting a process of withdrawal.

Second, popularity indicates the number of peers that name a focal individual as a friend, representing social status, visibility, and desirability as a friend (Kornienko & Santos, 2014). Maltreated youth may have socially undesirable traits or behaviors, such as lower emotional regulation and greater aggressive behaviors, or other socially stigmatized manifestations of maltreatment, such as neglected appearance (Bennett et al., 2010; Cicchetti, 2016; Trickett et al., 2011). Such factors can lead to reduced social status, lower likability, greater rejection from peers, or being ignored by peers (Cicchetti, 2016; Trickett et al., 2011), all factors that would contribute to peers being less likely to name maltreated youth as a friend. While prior work often examines peer neglect or rejection, we refrain from using these terms because the measure of popularity used here differs from prior studies by examining tie structure rather than emotional valence or intent, and so cannot distinguish between these concepts. Instead, from the social networks perspective, lower popularity indicates avoidance.

Third, cohesion refers to the density or tight-knittedness of interconnections among one’s connections (Copeland & Kamis, 2022; Valente, 2010). Cohesion indicates how indirect social ties can impact individuals, with the density of interconnections among others in a group affecting how groups provide social support, foster trust, and generate a sense of identity, as well as enact shared norms and social conformity (McGloin et al., 2014). Socially undesirable traits or behaviors associated with maltreatment may be more successfully sanctioned by more cohesive friend groups that can better enforce group norms compared to less cohesive groups (McGloin et al., 2014). Greater sanctions associated with cohesive friend groups may lead to maltreated youth occupying less cohesive social positions. Moreover, more cohesive friend groups require greater shared identity, trust, and social expectations (Falci & McNeely, 2009; McGloin et al., 2014). Experiencing maltreatment can increase mistrust of others (Poole et al., 2018), which may create barriers to maintaining cohesive friend groups for maltreated youth. We refer to the lack of cohesive friend groups predicted by maltreatment as fragmentation.

1.2. Maltreatment Types in the Context of Peer Relationships

We expect broad associations between maltreatment and peer network integration, yet maltreatment encompasses a range of experiences, including physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect. Although past work does not examine these types of maltreatment in the context of peer network dimensions, there is evidence that specific types of abuse and neglect may relate to peer connections differently. For example, research suggests that physical neglect and sexual abuse can produce shame that leads to lower self-perceptions of peer acceptance (Bennett et al., 2010; Feiring et al., 2000; Warmingham et al., 2019). Other work has found that physical and emotional abuse increase aggression and conduct-related problems (Berzenski & Yates, 2011; Warmingham et al., 2019) that can lead to lower likability among peers (Dodge et al., 1994; Yoon et al., 2018). Building on these past studies examining maltreatment types can further clarify how childhood abuse and neglect relate to peer network integration.

1.3. Current Study

This study extends past literature examining the impact of maltreatment on social relationships by incorporating a social networks perspective that underscores the importance of the network structure of direct and indirect ties among peers in school (Falci & McNeely, 2009; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Valente, 2010). We use data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) to examine how childhood maltreatment predicts three dimensions of peer networks. Building on prior work that finds that maltreatment generally creates barriers to successful peer friendships (Cicchetti, 2016; Trickett et al., 2011), we broadly seek to address the following research questions:

RQ1: Do maltreated youth withdraw from peers (lower sociality)?

RQ2: Are maltreated youth avoided by peers (lower popularity)?

RQ3: Do maltreated youth experience fragmentation among peers (lower cohesion)?

We first explore the association between any maltreatment and peer network integration, and then further explore the importance of maltreatment type by predicting withdrawal, avoidance, and fragmentation by specific kinds of abuse and neglect.

2. Method

2.1. Data

The sample for this study comes from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). During Wave I collection (1994/95) Add Health administered an in-school questionnaire to over 90,000 students in grades 7–12 across United States schools. During this survey, respondents were asked to name up to five each of their closest male and female friends. In schools where more than 50% of students completed the network portion of the survey, friendship nominations were matched to create sociocentric networks (Carolina Population Center, 2001). A subset of initial respondents was sampled for a subsequent in-home survey (N=20,745). Respondents from the in-home survey have been followed up in 1996 (Wave II), 2001–02 (Wave III), 2008–2009 (Wave IV), and 2016–2018 (Wave V) (Harris et al., 2019). The current study includes respondents who were in schools with calculated network data, who were eligible for in-home surveys, and present in Waves III and IV when maltreatment measures were collected (N= 9,154). Compared to our sample, those who were eligible for in-home surveys but who were not present in Waves III and IV were more likely to be male, older, have a maximum parental education of less than a high school degree, and have received public assistance. These respondents were also less likely to be Non-Hispanic white or to have been raised by two biological parents and had lower popularity, sociality, and cohesion.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Maltreatment Indicators

We follow CDC definitions (Mersky et al., 2021) of abuse and neglect and past work assessing maltreatment in Add Health (Hussey et al., 2006; Mishra et al., 2022; Parnes & Schwartz, 2022; Sokol et al., 2018) by including measures of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and physical neglect. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and physical neglect are measured at Wave III asking, “Before 6th grade…” Respondents are indicated as experiencing that type of maltreatment if they report that it occurred once or more. Emotional abuse is measured at Wave IV as, “Before your 18th birthday…” To ensure that maltreatment measures represent the same period of childhood and precede measures of networks, we only indicate emotional abuse if the respondent reports the first instance of any emotional abuse occurring prior to age 12 (youngest age at Wave I) (Sokol et al., 2018). Exact wording of maltreatment measures can be found in Appendix A. Any maltreatment is noted as 1 if a respondent reports experiencing any of the maltreatment indicators, and 0 if they report experiencing no maltreatment.

2.2.2. Peer Networks

Sociocentric network data are from the in-school Wave I survey of Add Health. Students can name up to five best male friends and five best female friends within their school. These nominations are then matched across respondents, creating global, sociocentric network data that capture the web of friendships within a school.

Sociality is measured by out-degree, the total number of friendship nominations sent by the respondent. Popularity is measured by in-degree, the total number of friendship nominations received by the respondent. Cohesion is measured by effective ego-network density, which indicates the number of existing friendship ties of possible ties in one’s friendship ego-network (as sent and received ties), adjusted for the cap at 10 possible nominations (Copeland & Kamis, 2022), calculated as

where, S=sum of ties in sent/received ego-network, N =number of nodes in sent/received ego-network, and 10 indicates the maximum possible number of sent nominations. Practically, cohesion indicates the reciprocity and tight-knittedness of one’s friend group, such as the extent to which friends are friends with each other. Further information about the calculation of network measures can be found in the Add Health network codebook (Carolina Population Center, 2001).

2.2.3. Covariates

We control for several individual-level demographic characteristics that relate to both peer networks and maltreatment to better capture the association between maltreatment and networks. Networks and the prevalence of maltreatment types typically differ by gender (“female” (ref.), “male”), age (measured at Wave I), and race/ethnicity (“Non-Hispanic white” (ref.), “Non-Hispanic Black”, “Hispanic”, and “Non-Hispanic other race”). Similarly, we adjust for household characteristics that often relate to both maltreatment and network integration, including maximum parental education at Wave I (“less than high school” (ref.), “high school degree”, “some college”, and “college degree”), whether a parent reported receiving public assistance at Wave I, and whether the respondent reported being raised by both biological parents in childhood (measured at Wave IV). School size (number of students in school) and the number of out of school friends named during friendship nomination were also included, as these factors may shape network characteristics.

2.5. Analysis Plan

Descriptive analyses showcase the prevalence of each form of maltreatment and average values for peer network measures in our sample. We perform a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions to assess the relationship between maltreatment and peer networks. The first set of models estimate how experiencing any form of maltreatment predicts each dimension of peer networks. The second set of models analyzes the impact of each type of maltreatment experience separately. For both sets of models, we control for both individual-level, household-level, and network-level characteristics described above. We adjust standard errors for the clustering of respondents in schools.

Missingness across study variables is low. The highest missingness is for parent-reported public assistance (13.2 % missing). We use multiple imputations by chained equations (MICE) with 20 imputations to adjust for missing data and note that analyses using listwise deletion yield substantively similar results. Descriptive analyses and statistical models were performed in Stata 18.0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive results (Table 1) suggest that on average, respondents in this sample send 4.49 friend nominations (sociality) and receive 4.54 friend nominations (popularity). The average cohesion in the sample is .18, suggesting that just under 20% of all possible ties are observed in their close friend network, so that on average, teens are not in extremely tight nor extremely fragmented friend groups. Ancillary analyses suggest that these dimensions of peer network structure are correlated, though moderately. Sociality and popularity are correlated with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of .41, and sociality and popularity are both correlated with cohesion with a correlation coefficient of approximately .63. A relatively high percentage of respondents in the sample indicate experiencing any type of abuse or neglect before 6th grade (or before age 12) (40.86%), consistent with other work using these measures in Add Health (Sokol et al., 2018). There were, however, stark differences in prevalence across types of maltreatment. Approximately 28.61% of respondents report experiencing any physical abuse, 4.36% any sexual abuse, 17.47% any emotional abuse, and 10.29% any physical neglect. Although not the focus of the present analyses, additional analyses suggest that the majority of respondents reporting any type of maltreatment reported only one type of abuse or neglect.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health); N=9,154.

| Mean or % | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Peer Network Position | ||

| Sociality | 4.49 | 3.01 |

| Popularity | 4.54 | 3.70 |

| Cohesion | 0.18 | 0.10 |

| Childhood Maltreatment (ever occurred) | ||

| Any Maltreatment | 40.86% | |

| Physical Abuse | 28.61% | |

| Sexual Abuse | 4.36% | |

| Emotional Abuse | 17.47% | |

| Physical Neglect | 10.29% | |

| Demographics and Home Characteristics | ||

| Male | 44.90% | |

| Age | 15.52 | 1.70 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| NH White | 53.26% | |

| NH Black | 22.66% | |

| Hispanic | 14.45% | |

| NH Other Race | 9.63% | |

| Maximum Parental Education | ||

| Less than HS | 11.41% | |

| HS Degree | 29.21% | |

| Some College | 21.55% | |

| College Degree | 37.84% | |

| Parent Report Public Assistance | 7.24% | |

| Raised by Two Biological Parents (Wave IV) | 70.35% | |

| School and Peer Characteristics | ||

| School Size | 1139.43 | 783.10 |

| Number of Out of School Friends | 1.36 | 2.07 |

Note: Childhood Maltreatment refers to experiences prior to 6th grade or age 12 (measured in Wave III & IV); Unless otherwise noted, all variables are from Wave I in-school and in-home surveys; NH = Non-Hispanic; HS= high school; SD= standard deviation.

3.2. Maltreatment Predicts Social Network Dimensions

Table 2 shows results predicting sociality, popularity, and cohesion by any maltreatment experience before 6th grade, controlling for all covariates and adjusting for clustering within schools. Results suggest that any maltreatment significantly predicts lower sociality (B= −0.214 ,p= 0.008), popularity (B= −0.222, p= 0.007), and cohesion (B= −0.009, p<.001). These results suggest that maltreatment separately predicts withdrawal (lower sociality), avoidance (lower popularity), and fragmentation (lower cohesion).

Table 2.

Regression Results Predicting Sociality, Popularity, and Cohesion by Any Childhood Maltreatment. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health); N=9,154.

| Sociality | Popularity | Cohesion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef (SE) |

Coef (SE) |

Coef (SE) |

| Any Childhood Maltreatment | −0.214 **

(0.079) |

−0.222 **

(0.080) |

−0.009 ***

(0.002) |

| Male | −0.693 ***

(0.072) |

−0.613 *** (0.102) |

−0.025 *** (0.002) |

| Age | −0.057 (0.031) |

0.018 (0.039) |

0.000 (0.001) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| NH White (ref.) | |||

| NH Black | −0.927 ***

(0.159) |

−0.958 *** (0.175) |

−0.041 *** (0.005) |

| Hispanic | −0.823 ***

(0.136) |

−0.660 ***

(0.164) |

−0.014 *

(0.006) |

| NH Other Race | −0.744 ***

(0.204) |

−0.938 *** (0.194) |

−0.018 *

(0.008) |

| Maximum Parental Education | |||

| Less than HS (ref.) | |||

| HS Degree | 0.146 (0.138) |

0.189 (0.145) |

0.007 (0.004) |

| Some College | 0.517 ***

(0.128) |

0.344 *

(0.159) |

0.017 *** (0.005) |

| College Degree | 0.511 ***

(0.137) |

0.657 ***

(0.167) |

0.027 *** (0.005) |

| Parent Report Public Assistance | −0.465 **

(0.139) |

−0.625 ***

(0.169) |

−0.015 **

(0.005) |

| Raised by Two Biological Parents (Wave IV) | 0.159 *

(0.066) |

0.263 *

(0.100) |

0.013 ***

(0.003) |

| School Size | 0.000 **

(0.000) |

0.000 **

(0.000) |

0.000 ***

(0.000) |

| Number of Out of School Friends | −0.402 ***

(0.024) |

−0.249 ***

(0.030) |

−0.008 ***

(0.001) |

| Constant | 6.644 ***

(0.592) |

5.354 ***

(0.592) |

0.230 ***

(0.022) |

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

Note: Any Maltreatment indicates experiencing physical, sexual, or emotional abuse or physical neglect; NH = Non-Hispanic; HS= high school

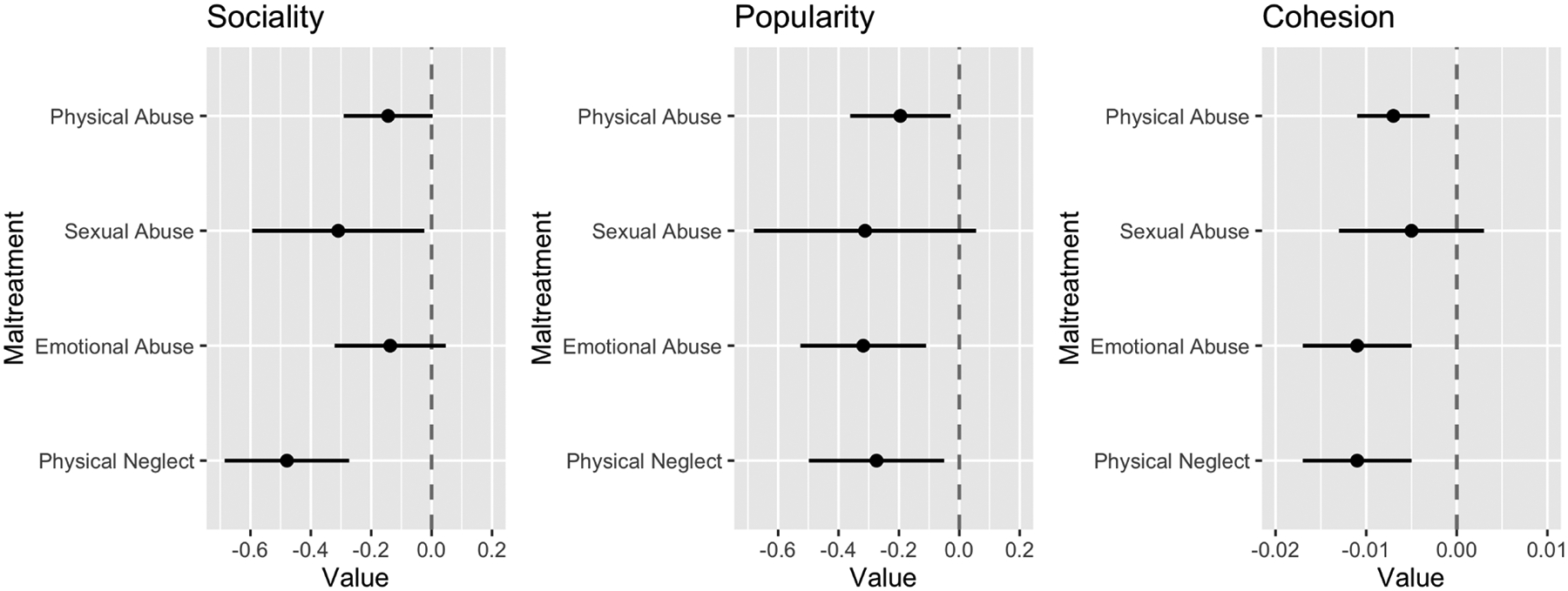

Figure 1 shows coefficients from models analyzing types of maltreatment separately, controlling for all covariates (coefficients, standard errors, and p-values available in Appendix B). Results indicate that certain types of maltreatment may be more salient for specific dimensions of peer network integration. Here, sociality is only significantly predicted by physical neglect (B= −0.479, p<.001) and sexual abuse (B= −0.309, p= 0.034). Physical abuse (B= −0.195, p= 0.022; B= −0.007, p=0.001), emotional abuse (B= −0.318, p= 0.003; B= −0.011, p<.001), and physical neglect (B= −0.274, p= 0.017; B= −0.011, p<.001) significantly predict popularity and cohesion, respectively. Put differently, sexual abuse predicts withdrawal (lower sociality) and physical abuse and emotional abuse predict avoidance (lower popularity) and fragmentation (lower cohesion). Physical neglect differs from all other types of maltreatment in that it is harmful to all three peer network dimensions.

Figure 1.

Regression Results Predicting Sociality, Popularity, and Cohesion by Each Childhood Maltreatment Measure. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health); N=9,154.

4. Discussion

This study examines the relationship between maltreatment (abuse and neglect) and several dimensions of social network structure indicating processes of withdrawal (sociality), avoidance (popularity), and fragmentation (cohesion). We build upon past work highlighting how maltreatment impacts children’s ability to develop social relationships through changes in social cognition, emotional regulation, attachment, and autonomy (Cicchetti, 2016; Yoon et al., 2023) by incorporating a missing perspective: how maltreatment affects social network structure, as individuals’ integration within the structure of direct and indirect connections from multiple viewpoints among peers in school (Carr, 2018; Cotterell, 2007; Valente, 2010). Findings here clarify how maltreatment influences multiple dimensions of peer connections and the salience of specific types of maltreatment for different dimensions of peer network integration.

Results suggest that any experience of maltreatment (compared to no maltreatment) predicts withdrawal (lower sociality), avoidance (lower popularity), and fragmentation (lower cohesion). Although present analyses do not explore specific mechanisms, these findings extend past work suggesting that maltreatment is detrimental to social connections.

First, findings on sociality indicate that youth who have experienced maltreatment name fewer friends among in-school peers, indicating withdrawal from the peer environment. This pattern is consistent with past work finding that maltreated children have lower self-esteem (Feiring et al., 2000), are less likely to see themselves as belonging (Sani et al., 2020), or feel greater shame (Bennett et al., 2010), suggesting here that such factors may lead to withdrawing from peers. Maltreatment may lead to anticipating rejection (Bolger & Patterson, 2001) or victimization (Benedini et al., 2016), or to developing attachment styles antithetical to reaching out to peers (Elliott et al., 2005), additional factors that can precipitate withdrawal.

Second, avoidance, or lower popularity of maltreated youth among peers, indicates that maltreated youth are less likely to be named as friends by peers. Maltreatment may increase behaviors that reduce desirability as a friend, such as greater emotional dysregulation and lower prosocial behavior (Trickett et al., 2011) or increased aggression or externalizing behaviors (Anthonysamy & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2007; Bolger & Patterson, 2001; Trickett et al., 2011). Separate from such behaviors, maltreatment itself is stigmatized (Purtle et al., 2022), so that if maltreatment leaves a visible trace or is otherwise known to peers, it may be a viewed as a stigmatized trait to avoid in potential friends.

Third, results show that childhood maltreatment predicts fragmentation, or lower cohesion. Cohesion represents indirect ties among peers that shape the tight-knittedness of peer groups, an aspect of peer connection particularly understudied in relation to abuse and neglect. Cohesive groups may better sanction the non-normative social behaviors of youth who have experienced maltreatment (e.g., emotion dysregulation, aggression), leading these youth to occupy more fragmented positions. Alternatively, insecure attachment and greater mistrust on the part of maltreated youth could make belonging to a more interconnected group more stressful. Maltreated youth may instead opt for investing in one-on-one relationships, or may end up spanning different friend groups rather than becoming deeply embedded in a cohesive, interconnected group.

Next, results examining separate types of abuse and neglect find differences in which types of maltreatment relate to which peer network dimensions. Results for withdrawal indicate that physical neglect and sexual abuse predict lower sociality. This result is consistent with past work suggesting that physically neglected children are more shame-prone (Bennett et al., 2010) and that sexual abuse predicts lower self-perceptions of peer acceptance and closeness (Feiring et al., 2000; Trickett et al., 2011), factors that can contribute to adolescents who have experienced these types of abuse withdrawing from peer networks. However, why emotional and physical abuse do not predict withdrawal is less clear. These types of maltreatment may relate less to shame or self-perceptions of relationships, instead affecting peer connections through other means than withdrawal, such as popularity, discussed below.

Avoidance, as lower popularity, is significantly predicted by physical abuse, emotional abuse, and physical neglect (but not sexual abuse). Much research notes that physically abused children are more likely to exhibit aggressive and antisocial behavior (Dodge et al., 1994; Trickett et al., 2011) and externalizing symptoms (Yoon, 2020; Yoon et al., 2023) that lead to peer rejection and lower likability. Emotional abuse is likewise associated with lower emotional regulation, greater externalizing symptoms, and affiliation with deviant peers (Yoon et al., 2021), which could be seen as unfavorable to most peers. Studies on neglect and emotional abuse suggest similar patterns of lower parental involvement leading to increased deviance and lower peer approval (Chapple et al., 2005). The findings here extend such research to peer network structure, suggesting that beyond approval, likability, or deviance, peers are less likely to nominate maltreated adolescents as friends.

The non-significance of sexual abuse here may suggest that this type of abuse is less visible to peers, so that it shapes self-perceptions (as with withdrawal above), but not peer perceptions. Interestingly, prior work examining a different measure of sexual victimization finds significant associations with popularity in a sample of adolescent girls (Tomlinson et al., 2021), which may suggest gender-specific effects. For example, if girls’ friendships typically involve greater self-disclosure in ways that increase peer knowledge of sexual assault, it may shape peers’ friendship nominations toward girls in ways that are less salient for boys. These potential differences by gender or type of sexual violence should be examined in future work.

Like avoidance, fragmentation is predicted by all forms of maltreatment except for sexual abuse. Adolescents who experienced physical abuse, emotional abuse, or physical neglect in childhood are less likely to be in tight-knit friend groups where friends are friends with each other, or they may span different groups. If these types of maltreatment increase undesirable behaviors as discussed above, such behaviors may lead to maltreated youth being less able to maintain positions in more cohesive groups that better sanction norm violations. If abuse and neglect foster general mistrust or maladaptive attachment styles (Cicchetti, 2016), tight-knit friend groups may be stressful rather than supportive for youth who have experienced physical or emotional abuse or physical neglect.

Taken together, results indicate that withdrawal is more closely aligned with sexual abuse, while avoidance and fragmentation stem from emotional and physical abuse. Physical neglect negatively impacts all three network dimensions considered here. Although examining maltreatment separately by type is helpful for further understanding the potential mechanisms that link maltreatment to social relationships, it is important to remember that types of maltreatment do not typically occur in isolation from one another or from other types of childhood adversity (Sokol et al., 2018). Results here should be interpreted as the relationship between a type of maltreatment and peer network dimension, but not the impact of a specific abuse or neglect experience net of all other types of adversity or the relationship for those only experiencing one type of adversity. Future work should explore how patterns outlined here extend to co-occurring adversities.

Overall, results from this study show that different maltreatment types relate to distinct dimensions of network integration, providing an important first step toward bridging past work on childhood maltreatment with social network analysis. The network dimensions here represent building blocks of integration. However, childhood maltreatment’s impact on these basic measures of integration can compound over time to influence more complicated network structures. For example, if maltreated youth are more likely to withdrawal from or be avoided by peers, lacking ties to peers subsequently contributes to lacking more complex forms of integration, such as transitive ties or structural cohesion, which contribute to adolescent well-being (Bearman & Moody, 2004; Moody & White, 2003; Valente, 2010). Moreover, social integration in adolescence sets the stage for social relationships across the life course (Kamis & Copeland, 2020; Trickett et al., 2011). Lower integration means that maltreated youth are missing the developmental benefits of peer networks, which may have a lasting impact. Thus, findings here show only a conservative snapshot of how maltreatment influences peer connections, with the potential for broader network and life course consequences for social connection and well-being.

This study is not without limitations. We perform multiple comparisons, which may lead to concerns about Type 1 errors. Popular corrections for multiple testing (e.g., Bonferroni correction) may lead to some results presented here falling below statistical significance. However, such corrections may be too conservative, inflating the probability of a Type 2 error, and may be ill-advised for exploratory studies (Althouse, 2016; García-Pérez, 2023). Nevertheless, results should be interpreted with caution, and further confirmatory studies with narrower, pre-planned hypotheses are warranted. Peer networks are measured in the mid-1990’s and peer connections could look different for contemporary youth given social and technological changes. However, the impact of maltreatment on peer connections is still found in contemporary research, and despite its age, Add Health is the best available dataset that enables assessing maltreatment and sociocentric peer network structure in a large, nationally-based dataset. Future work should gather information on contemporary peer networks across the U.S. to examine the patterns discussed here in current adolescent cohorts. Social network measures used here measure structural dimensions of peer networks and therefore do not consider other details of connections, such as relationship quality or characteristics of peers. Work building on the findings presented here may consider these additional dimensions of friendships in tandem with structural features to further clarify the impact of maltreatment on peer relationships in adolescence. Maltreatment measures are gathered through retrospective reports and only report respondents’ views of their childhood, which may face recall bias (Hardt & Rutter, 2004). Future work should also expand on the results here to consider additional aspects of childhood maltreatment, such as co-occurrence, severity, duration, and timing (Friedman et al., 2015). Finally, future work should consider if patterns observed here are consistent across sociodemographic groups (such as those based on gender and race and ethnicity) that may have differing risks of childhood maltreatment and unique friendship experiences.

5. Implications and Conclusion

Results highlight the link between childhood maltreatment and social integration in peer networks in adolescence. Importantly, this study finds that all forms of maltreatment influence peer integration in some way, whether through withdrawal, avoidance, or fragmentation. Adolescent peer networks provide key psychosocial and developmental resources, making integration in adolescent networks strongly predictive of adolescent and adult well-being (Cotterell, 2007; Crosnoe, 2000; Falci & McNeely, 2009; Kamis & Copeland, 2020). Thus, such relative disconnection or isolation from peers may further disadvantage maltreated youth who are already experiencing hardship in early life, and who may have a greater need for peer connections as social resources buffering the negative impacts of maltreatment.

Beyond the overall risks of maltreatment to peer network integration, results suggest the need to pay particular attention to the social consequences of physical neglect, which reduces multiple dimensions of social integration. Physical neglect is the most frequently reported maltreatment type in Child Protective Services (CPS) records but receives relatively lower attention by researchers (Warmingham et al., 2019). Results here challenge the lack of focus paid to physical neglect, highlighting the importance of this type of maltreatment for social disconnection from peers.

The findings presented here support the development of interventions that promote peer connections for maltreated youth. For example, programs that focus on reducing shame, challenging negative self-perceptions, and reaching out to others may be particularly beneficial for youth who have experienced sexual abuse. Similarly, stakeholders and practitioners should consider how youth who have experienced physical neglect may be at particular risk for social disconnection from peers through multiple avenues, and that even maltreated youth who maintain friendships may lack the particularly supportive opportunities of cohesive groups. Working to address mistrust or develop social skills may have positive externalities for maintaining cohesive social ties beyond simply increasing the number of friends. Future work should further explore the mechanisms that link different types of maltreatment to peer networks and examine how peer connections may ameliorate both proximal and distal effects of maltreatment on well-being. Overall, this study speaks to the research on childhood adversity, social networks, and well-being in early life by clarifying our understanding of how childhood maltreatment shapes adolescent peer network structure.

Highlights.

Any childhood maltreatment leads to withdrawal, avoidance, and fragmentation in peer networks.

Sexual abuse and physical neglect predict withdrawal.

Physical abuse and neglect and emotional abuse predict avoidance and fragmentation.

Acknowledgements:

This research uses data from Add Health, funded by grant P01 HD31921 (Harris) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Add Health is currently directed by Robert A. Hummer and funded by the National Institute on Aging cooperative agreements U01 AG071448 (Hummer) and U01AG071450 (Aiello and Hummer) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Add Health was designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix A. Measurement of Childhood Maltreatment

| Variable | Wave | Question | Coding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Abuse | III | By the time you started 6th grade, how often had your parents or other adult caregivers slapped, hit, or kicked you? | 1=if ever happened; 0=otherwise |

| Sexual Abuse | III | By the time you started 6th grade, how often had your parents or other adult caregiver touched you in a sexual way, forced you to touch him or her in a sexual way, or forced you to have sexual relations? | 1=if ever happened; 0=otherwise |

| Emotional Abuse | IV | Before your 18th birthday, how often did a parent or other adult caregiver say things that really hurt your feelings or made you feel like you were not wanted or loved? How old were you the first time this happened? | 1=if first happened before respondent was 12 years old; 0=otherwise |

| Physical Neglect | III | By the time you started 6th grade, how often had your parents or other adult caregiver not taken care of your basic needs, such as keeping you clean or providing food or clothing? | 1=if ever happened; 0=otherwise |

Appendix B. Model Results for Figure 1 Predicting Sociality, Popularity, and Cohesion by Each Childhood Maltreatment Measure. National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health); N=9,154.

| Sociality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coef | SE | p-value |

| Physical Abuse | −0.144 | 0.074 | 0.054 |

| Sexual Abuse | −0.309 | 0.144 | 0.034 |

| Emotional Abuse | −0.137 | 0.093 | 0.143 |

| Physical Neglect | −0.479 | 0.104 | 0.000 |

| Popularity | |||

| Variable | Coef | SE | p-value |

| Physical Abuse | −0.195 | 0.084 | 0.022 |

| Sexual Abuse | −0.312 | 0.186 | 0.097 |

| Emotional Abuse | −0.318 | 0.105 | 0.003 |

| Physical Neglect | −0.274 | 0.113 | 0.017 |

| Cohesion | |||

| Variable | Coef | SE | p-value |

| Physical Abuse | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.001 |

| Sexual Abuse | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.244 |

| Emotional Abuse | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

| Physical Neglect | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.000 |

Note: All models are conducted separately and each model includes all covariates.

References

- Althouse AD (2016). Adjust for Multiple Comparisons? It’s Not That Simple. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 101(5), 1644–1645. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthonysamy A, & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (2007). Peer status and behaviors of maltreated children and their classmates in the early years of school. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(9), 971–991. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, & Moody J (2004). Suicide and Friendships among American Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 94(1), 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedini KM, Fagan AA, & Gibson CL (2016). The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 111–121. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, & Lewis M (2010). Neglected Children, Shame-Proneness, and Depressive Symptoms. Child Maltreatment, 15(4), 305–314. 10.1177/1077559510379634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berzenski SR, & Yates TM (2011). Classes and Consequences of Multiple Maltreatment: A Person-Centered Analysis. Child Maltreatment, 16(4), 250–261. 10.1177/1077559511428353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, & Patterson CJ (2001). Developmental Pathways from Child Maltreatment to Peer Rejection. Child Development, 72(2), 549–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB, & Larson J (2009). Peer Relationships in Adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolina Population Center. (2001). National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health: Network Variables Code Book.

- Carr D (2018). The Linked Lives Principle in Life Course Studies: Classic Approaches and Contemporary Advances. In Alwin DF, Felmlee DH, & Kreager DA (Eds.), Social Networks and the Life Course: Integrating the Development of Human Lives and Social Relational Networks (pp. 41–63). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-71544-5_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chapple CL, Tyler KA, & Bersani BE (2005). Child Neglect and Adolescent Violence: Examining the Effects of Self-Control and Peer Rejection. Violence and Victims, 20(1), 39–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ SL, Kwak YY, & Lu T (2017). The joint impact of parental psychological neglect and peer isolation on adolescents’ depression. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 151–162. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D (2016). Socioemotional, Personality, and Biological Development: Illustrations from a Multilevel Developmental Psychopathology Perspective on Child Maltreatment. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 187–211. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland M, & Kamis C (2022). Who Does Cohesion Benefit? Race, Gender, and Peer Networks Associated with Adolescent Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 10.1007/s10964-022-01631-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotterell J (2007). Social Networks in Youth and Adolescence (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford KM, Choi K, Davis KA, Zhu Y, Soare TW, Smith ADAC, Germine L, & Dunn EC (2022). Exposure to early childhood maltreatment and its effect over time on social cognition. Development and Psychopathology, 34(1), 409–419. 10.1017/S095457942000139X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2000). Friendships in Childhood and Adolescence: The Life Course and New Directions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4,), 377–391. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, & Johnson MK (2011). Research on Adolescence in the Twenty-First Century. Annual Review of Sociology, 37(1), 439–460. 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Olson JS, & Cheadle JE (2018). Problems at Home, Peer Networks at School, and the Social Integration of Adolescents. In Alwin DF, Felmlee DH, & Kreager DA (Eds.), Social Networks and the Life Course (Vol. 2, pp. 205–218). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-71544-5_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Pettit GS, & Bates JE (1994). Effects of physical maltreatment on the development of peer relations. Development and Psychopathology, 6(1), 43–55. 10.1017/S0954579400005873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott GC, Cunningham SM, Linder M, Colangelo M, & Gross M (2005). Child physical abuse and self-perceived social isolation among adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(12), 1663–1684. 10.1177/0886260505281439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falci C, & McNeely C (2009). Too many friends: Social integration, network cohesion and adolescent depressive symptoms. Social Forces, 87(4), 2031-. [Google Scholar]

- Feiring C, Rosenthal S, & Taska L (2000). Stigmatization and the Development of Friendship and Romantic Relationships in Adolescent Victims of Sexual Abuse. Child Maltreatment, 5(4), 311–322. 10.1177/1077559500005004003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster M, Grigsby TJ, Bunyan A, Unger JB, & Valente TW (2015). The Protective Role of School Friendship Ties for Substance Use and Aggressive Behaviors Among Middle School Students. Journal of School Health, 85(2), 82–89. 10.1111/josh.12230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Montez JK, Sheehan CM, Guenewald TL, & Seeman TE (2015). Childhood Adversities and Adult Cardiometabolic Health: Does the Quantity, Timing, and Type of Adversity Matter? Journal of Aging and Health, 27(8), 1311–1338. 10.1177/0898264315580122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez MA (2023). Use and misuse of corrections for multiple testing. Methods in Psychology, 8, 100120. 10.1016/j.metip.2023.100120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC (2003). Relationships in Adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Green HD, Tucker JS, Wenzel SL, Golinelli D, Kennedy DP, Ryan GW, & Zhou AJ (2012). Association of childhood abuse with homeless women’s social networks. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(1), 21–31. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, & Rutter M (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(2), 260–273. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel EA, Hussey JM, Killeya-Jones LA, Tabor J, & Dean SC (2019). Cohort Profile: The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(5), 1415–1415k. 10.1093/ije/dyz115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam Z, & Taylor EP (2022). The relationship between child neglect and adolescent interpersonal functioning: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 125, 105510. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, & Layton JB (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Chang JJ, & Kotch JB (2006). Child Maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Adolescent Health Consequences. Pediatrics, 118(3), 933–942. 10.1542/peds.2005-2452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamis C, & Copeland M (2020). The Long Arm of Social Integration: Gender, Adolescent Social Networks, and Adult Depressive Symptom Trajectories. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 0022146520952769. 10.1177/0022146520952769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornienko O, & Santos CE (2014). The Effects of Friendship Network Popularity on Depressive Symptoms During Early Adolescence: Moderation by Fear of Negative Evaluation and Gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(4), 541–553. 10.1007/s10964-013-9979-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGloin JM, Sullivan CJ, & Thomas KJ (2014). Peer Influence and Context: The Interdependence of Friendship Groups, Schoolmates and Network Density in Predicting Substance Use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(9), 1436–1452. 10.1007/s10964-014-0126-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Colich NL, Rodman AM, & Weissman DG (2020). Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 96. 10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersky JP, Choi C, Plummer Lee C, & Janczewski CE (2021). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences by race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status: Intersectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105066. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra AA, Marceau K, Christ SL, Schwab Reese LM, Taylor ZE, & Knopik VS (2022). Multi-type childhood maltreatment exposure and substance use development from adolescence to early adulthood: A GxE study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 126, 105508. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J, & White DR (2003). Structural Cohesion and Embeddedness: A Hierarchical Concept of Social Groups. American Sociological Review, 68(1), 103–127. 10.1177/000312240306800105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negriff S, & Valente TW (2018). Structural characteristics of the online social networks of maltreated youth and offline sexual risk behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 209–219. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes MF, & Schwartz SEO (2022). Adverse childhood experiences: Examining latent classes and associations with physical, psychological, and risk-related outcomes in adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 127, 105562. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole JC, Dobson KS, & Pusch D (2018). Do adverse childhood experiences predict adult interpersonal difficulties? The role of emotion dysregulation. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 123–133. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle J, Nelson KL, & Gollust SE (2022). Public Opinion About Adverse Childhood Experiences: Social Stigma, Attribution of Blame, and Government Intervention. Child Maltreatment, 27(3), 344–355. 10.1177/10775595211004783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani F, Herrera M, & Bielawska K (2020). Child maltreatment is linked to difficulties in identifying with social groups as a young adult. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 38(4), 491–496. 10.1111/bjdp.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RL, Gottfredson NC, Shanahan ME, & Halpern CT (2018). Relationship between Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Body Mass Index Trajectories. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 196–202. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson TA, Mears DP, Turanovic JJ, & Stewart EA (2021). Forcible Rape and Adolescent Friendship Networks. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), 4111–4136. 10.1177/0886260518787807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, & Negriff S (2011). Child Maltreatment and Social Relationships. In Underwood MK & Rosen LH, (Eds.), Social Development: Relationships in Infancy, Childhood, and Adolescence (pp. 403–426). Guilford Press. https://interlib.lib.msu.edu/remoteauth/illiad.dll?Action=10&Form=75&Value=1369045 [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Negriff S, Ji J, & Peckins M (2011). Child Maltreatment and Adolescent Development. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 3–20. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00711.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW (2010). Social Networks and Health: Models, Methods, and Applications. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Warmingham JM, Handley ED, Rogosch FA, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D (2019). Identifying maltreatment subgroups with patterns of maltreatment subtype and chronicity: A latent class analysis approach. Child Abuse & Neglect, 87, 28–39. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D (2020). Peer‐relationship patterns and their association with types of child abuse and adolescent risk behaviors among youth at‐risk of maltreatment. Journal of Adolescence, 80(1), 125–135. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Yoon M, Wang X, & Robinson-Perez AA (2023). A developmental cascade model of adolescent peer relationships, substance use, and psychopathological symptoms from child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 137, 106054. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Yoon S, Park J, & Yoon M (2018). A pernicious cycle: Finding the pathways from child maltreatment to adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 139–148. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon D, Yoon S, Pei F, & Ploss A (2021). The roles of child maltreatment types and peer relationships on behavior problems in early adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112, 104921. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]