Abstract

Segmentation is a fundamental feature of the vertebrate body plan. This metameric organization is first implemented by somitogenesis in the early embryo, when paired epithelial blocks called somites are rhythmically formed flanking the neural tube. Recent advances in in vitro models have offered promise to elucidate the mechanism underlying somitogenesis. Notably, models derived from human pluripotent stem cells introduced an efficient proxy to study this process during human development. Here, we focus on our current understanding of somitogenesis gained from both in vivo and in vitro studies. We deconstruct the spatiotemporal dynamics of somitogenesis in four distinct modules: dynamic events in the presomitic mesoderm, segmental determination, somite anteroposterior polarity patterning, and epithelial morphogenesis – and detail the mechanisms operating in each module.

Introduction

Segmentation is a fundamental feature of the vertebrate body plan, which is most evident in the periodic arrangement of the vertebrae and peripheral nerves. This metameric organization of the adult body is first established in the early embryo by the process of somitogenesis1, when the bilateral mesodermal tissue flanking the neural tube – the paraxial mesoderm – repetitively forms paired blocks called somites along the anterior-posterior body axis (Fig.1a). The periodically arranged somites provide the blueprint on which the segmentally organized musculoskeletal axis, vascular system, and peripheral nervous system are built. The characteristics of somite organization thus play a significant role in defining the shape of vertebrate bodies. In humans, a range of genetic mutations associated with somitogenesis leads to segmentation defects of the vertebrae including congenital scoliosis and spondylocostal dysostosis2–13 (Box 1).

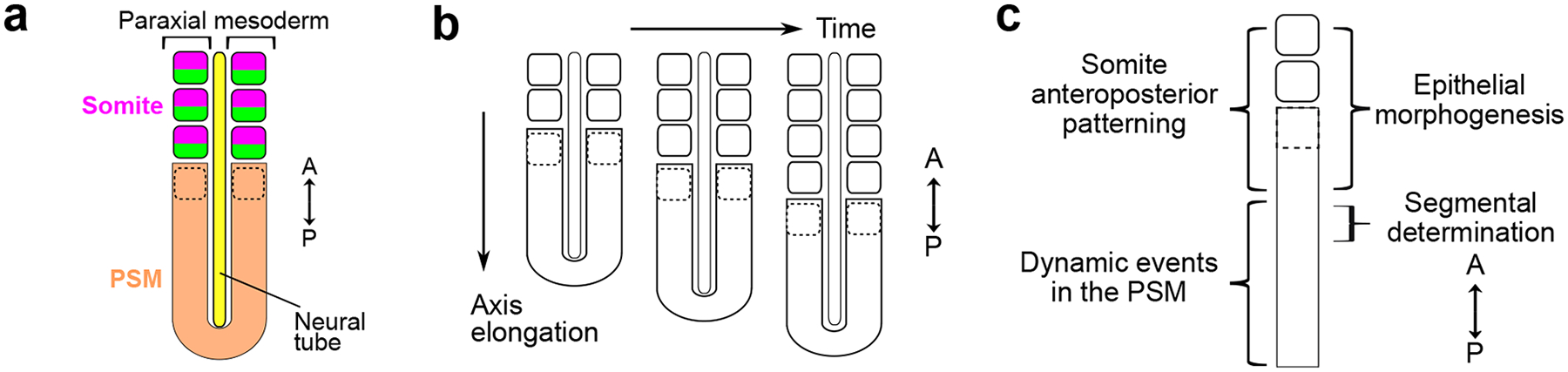

Figure 1. Paraxial mesoderm segmentation and modules of somitogenesis.

a. The paraxial mesoderm locates on either side of the neural tube. It forms epithelial blocks called somites from the unsegmented region called presomitic mesoderm (PSM). Each somite is subdivided into an anterior (magenta) and posterior (green) compartment associated with different transcriptomes and developmental trajectories. The dotted outline represents the forming somite. A, anterior; P, posterior.

b. Somites are formed sequentially in an anterior to posterior direction, in coordination with the elongation of the body axis.

c. Simplified representation of the paraxial mesoderm and general locations of different somitogenesis modules. In the anterior PSM, both somite anteroposterior patterning and epithelial morphogenesis are initiated with the expression of MESP transcription factors, just anteriorly to segmental determination.

Box1 – Defective somitogenesis leads to congenital segmentation disorders.

Segmentation defects of the vertebrae (SDV) have been estimated to affect 0.5–1 newborns per 1000 births199,200. Types of SDV vary based on the extent (one or multiple vertebrae affected) and location (e.g. cervical, lumbar, sacral, etc.) of defects201. Among severe abnormalities that affect multiple continuous vertebrae, Spondylocostal Dysostosis (SCD) is characterized by the presence of extensive hemivertebrae, abnormally aligned ribs, and shortening of the trunk. Similarly, Spondylothoracic Dysostosis (STD) leads to severe vertebral malformations with complete bilateral fusion of the ribs at the costovertebral junctions. Milder forms of SDV affecting single or regionalized vertebrae include congenital scoliosis that results in a lateral curvature of the spine exceeding 10 degrees, as well as the Klippel–Feil syndrome that affects the cervical vertebrae limiting the motion of the neck. SDV can be caused by defective embryonic segmentation due to pathogenic mutations of key somitogenesis genes. Genetic analysis has identified that a majority of SCD cases are caused by mutations and truncations in the DLL3 gene which encodes a key regulator of the segmentation clock2,9. Other SCD subsets can be caused by mutations in genes encoding the core segmentation clock component HES7 (ref3), vital modulator LFNG13, the master segmental and polarity regulator MESP2 (ref4), etc. Cases of STD are also caused by mutations in the MESP2 gene6, and the Klippel–Feil syndrome is associated with mutations of the somitic gene MEOX1 (ref11). Overall, most of these cases appear to be autosomal recessive caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations, although dominant cases have been reported including a dominant SCD linked to TBX6 mutations10. Additionally, environmental influences such as hypoxia and carbon monoxide exposure may have teratogenic effects on spine development200. In fact, very few cases of congenital scoliosis can be clearly attributed to a simple genetic cause. Congenital scoliosis patients in high-altitude regions tend to show more severe rib deformities202, highlighting the significance of gene-environment interactions. Hypoxia exposure to pregnant mice greatly increased the severity and penetrance of vertebral defects in heterozygous Hes7 or Mesp2 mutant mouse embryos likely via disruptions of FGF signaling7. Recent in vitro models offer a tractable, human-specific platform to further study causes of SDV. In-depth molecular, cellular, and functional analysis can be performed on human paraxial mesoderm cells differentiated from pluripotent stem cells bearing pathogenetic mutations or directly derived from patients27,32. Environmental factors can also be quantitatively controlled to elucidate the etiology of segmentation defects.

Somitogenesis is a complex, dynamic process representing the epitome of elegant self-organization in development. In the paraxial mesoderm, somites form rhythmically from the anterior-most part of the unsegmented region called presomitic mesoderm (PSM) which lies at the posterior end of the embryo. Somite formation occurs sequentially from head to tail, in a coordinated manner with body axis elongation (Fig.1b). The temporal rhythm and total number of somites formed are defining features of vertebrate species14,15. In addition to its signature morphology of epithelial block, each somite is subdivided into anterior and posterior compartments defined by specific transcriptomes and developmental trajectories16–18. Due to its remarkable spatiotemporal characteristics, somitogenesis has served as a paradigm to decode design principles of development.

We now know that the process of somitogenesis includes several dynamic signaling processes, entangled feedback regulations, and interconnected cellular and tissue behaviors. An oscillating gene regulatory network called segmentation clock controls the rhythm of somite formation1,19. In each cycle, activity of the clock is initiated in the posterior PSM and travels anteriorly as a wave of gene transcription. When reaching the anterior PSM, the clock activity together with posterior to anterior signaling gradients specify the segmental domain, concomitantly with the onset of the epithelialization program. The antero-posterior polarity of the future somite is also established before formation of the boundary which separates the epithelial somite from the PSM. Despite some diversity in the gene regulatory networks and cellular behaviors, the general principles and machinery underlying somitogenesis are highly conserved across vertebrate species.

In this review, we first highlight recent advances in developing experimental in vitro models of somitogenesis. We then review our current knowledge of somitogenesis gained from both in vivo and in vitro studies. We deconstruct the complex process of somitogenesis in four patterning modules interacting during somite formation (Fig.1c). We first focus on the dynamic events taking place in the posterior PSM, including the segmentation clock and signaling gradients, before detailing their combined role in segment determination in the anterior PSM. We then summarize the mechanism of antero-posterior polarity patterning, followed by overviewing the programs that lead to epithelial somite morphogenesis.

Studying somitogenesis in vitro

While embryos from mouse, chicken, and zebrafish continue to serve as experimental models of somitogenesis, a new array of in vitro models have been recently developed20. These include ex vivo cultures of embryo explants21–23 as well as in vitro models based on differentiated pluripotent stem cells (PSCs)24–33. These models allow direct visualization combined with sophisticated manipulations to investigate the mechanism of segmentation. In addition, models from human PSCs make it possible to study human somitogenesis which takes place between 3 to 4 weeks after fertilization when embryos are rarely accessible34. With these models, human specific traits and etiology of congenital diseases can also be investigated in depth.

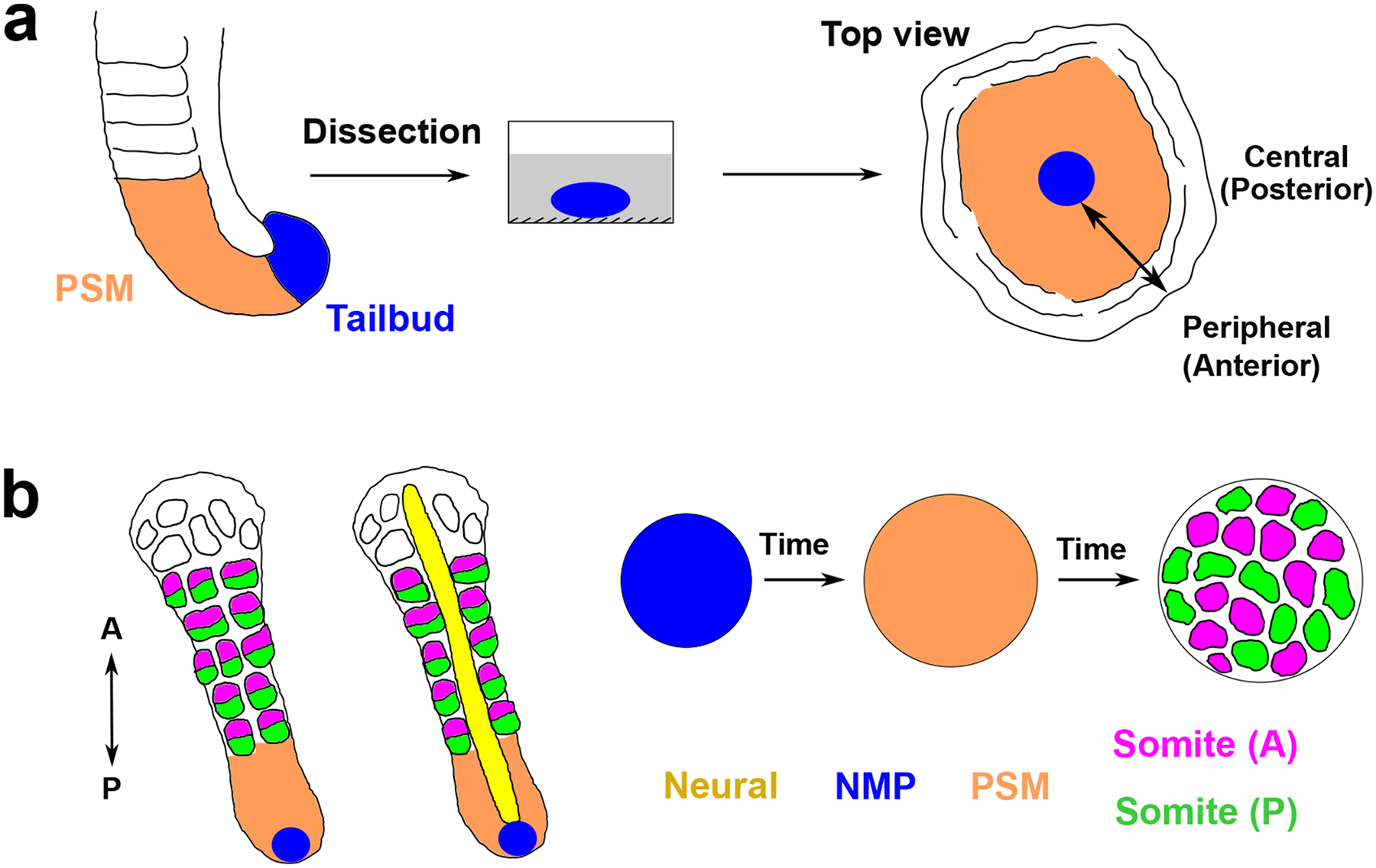

Embryo explants cultured ex vivo have long been used as experimental systems to dissect somitogenesis. The pulsatile expression of cHairy1 in the PSM was initially demonstrated by splitting caudal explants of chicken embryos along the midline with one half fixed while the other was cultured for some time before fixation35. This allowed reconstructing the periodic waves of cHairy1(HES4) expression, leading to the discovery of the segmentation clock35. Cultured mouse embryos and explants with live reporters were later used to directly visualize clock oscillations36,37. Recently, simplified systems have been developed for in-depth study of somitogenesis. Dissociated single cells from the PSM of zebrafish embryos were used to investigate cell-autonomous features of the segmentation clock38. A quasi-2D mouse explant system termed monolayer PSM formed from dissected mouse tailbud cultured on fibronectin without added signaling factors first demonstrated that the segmentation clock activity can be observed in vitro21 (Fig.2a). These explants form a disk-like tissue displaying periodic waves of gene expression and physical segment formation, establishing a central-peripheral axis corresponding to the posterior-anterior axis in the embryo21. By further supplementing signaling factors to mimic the signaling environment of the posterior PSM, through activating WNT and FGF signaling while inhibiting BMP and Retinoid acid, these explants were maintained in an oscillating state for up to 48 hours22. Together with reaggregation assays, density controls, and microfluidic devices, quantitative investigations using the explant system revealed a range of novel emergent phenomena in the PSM21,22,39,40.

Figure 2. In vitro models of somitogenesis.

a. Dissected mouse tailbud is cultured on a fibronectin-coated dish, forming a flat disk-like tissue displaying sequential segment formation from the edge to the center. Its central-peripheral axis corresponds to the posterior-anterior axis of the embryo.

b. PSC-derived organoid models of somitogenesis give rise to sequential (left and middle) or simultaneous (right) formation of somite-like structures. In organoids such as segmentoids or axioloids, somites are sequentially formed from the PSM (orange) and subdivided into an anterior (magenta) and posterior (green) half. NMPs are labelled as blue and locate at the posterior tip of the elongating structures. The neural tube (yellow) can also be generated in some protocols. In somitoids (right) where cells differentiate in sync and form somites simultaneously, entirely anterior or posterior somite-like structures are randomly distributed. A, anterior; P, posterior.

The remarkable autonomy of the somitogenesis program ex vivo has inspired efforts to develop embryo-free models using pluripotent stem cells (PSC). Directed differentiation of PSC to paraxial mesoderm was achieved by recapitulating the stepwise developmental trajectory learned from in vivo studies41. In embryos, paraxial mesoderm is derived from neuromesodermal progenitors (NMP) which reside in the anterior region of the primitive streak and its lateral epiblast, as well as in the tailbud at later stages42–46. The signaling environment of this region is characterized by high WNT47,48, high FGF49, low BMP50, and moderate Nodal or TGFβ51,52. Similar signaling cues are required for the specification from NMP to PSM. Based on these, multiple protocols have been developed using cocktails of signaling factors to direct the differentiation of human PSCs to NMP and then to posterior PSM25–27,41,53–55. The GSK3β inhibitor CHIR99021 to active WNT signaling is used in all protocols, in combination with other factors. Addition of all the factors to the culture medium is however not essential as for instance FGF and Nodal are produced by cultured cells upon WNT activation26.

A first class of in vitro models focuses on recapitulating the segmentation clock and signaling gradients. This was pioneered by the induced PSM or iPSM model24 derived from aggregates of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) differentiated in vitro. iPSM displayed centrifugal traveling waves of Hes7 expression and an FGF signaling gradient, resembling the mouse tailbud explants. Simplified two-dimensional models, which support clock oscillations and where cells differentiate simultaneously, were further established25–27. Such 2D models using human PSCs were used to identify the human segmentation clock25–27. The other broad class of models reconstitute all stages of somitogenesis, generating somite-like structures in vitro (Fig.2b). This was pioneered by the development of gastruloids56,57, which are elongated PSC-derived cell aggregates induced by a pulse of the WNT agonist CHIR99021. They contain derivatives from all three germ layers and establish dorsal-ventral and anterior-posterior axes. When embedded in low-percentage Matrigel, mESC-derived gastruloids can sequentially form epithelial somites exhibiting antero-posterior polarity28. A variation of the gastruloid protocol can produce trunk-like structures composed of morphological somites flanking a neural tube29. Recently, several models such as segmentoids and axioloids have been established using human PSCs30–33,58,59. These capture major hallmarks of the dynamics of somite formation and patterning. Another model called somitoid recapitulates paraxial mesoderm development in time but without the spatial dimension, giving rise to simultaneously formed somite-like structures in a spreading disk-shaped tissue31. Machine learning and micropatterning were further used to tune the spatial coupling of PSC aggregates to optimize the generation of human trunk organoids consisting of somites and neural tube33. These models provide valuable platforms to advance human developmental biology.

At the same time, limitations of current in vitro models should be borne in mind. Most protocols yielding 3D structures have an efficiency lower than the natural embryo and generate organoids with heterogenous shapes, limiting applications such as high-throughput screening. Recent efforts incorporating bioengineering toolsets have demonstrated promising ways to reinforce high efficiency and consistency in organoid production33,60–62. Matrix with defined components and properties should be explored to replace Matrigel, a protein mix extracted from mouse tumors, whose undefined nature should be treated with caution during data interpretation. Furthermore, a range of complex features of somitogenesis remain to be recapitulated in vitro. Although HOX gene collinearity has been characterized in some models32,56,57,59, axial regionalization is hard to control in vitro and all current models display a premature cessation of elongation. Thus, region-specific mechanisms of somitogenesis as well as the regulation of total somite number remain difficult to study in vitro. Additionally, interactions of the somitogenesis machinery with the signaling and physical environments provided by surrounding cell lineages in the embryo cannot be directly investigated with current models. Nevertheless, with the rapid pace of in vitro model development and improvement, a bright future lies ahead.

Dynamic events in the presomitic mesoderm

The precision and consistency of somite formation require a variety of orchestrated molecular and cellular events starting in the posterior PSM. We can learn many principles of self-organization by studying the establishment of these dynamic events. We will consider their functional roles in the next section.

The segmentation clock.

Following its discovery in the chicken embryo, the segmentation clock has been shown to be conserved from fish to humans26,27,35–37,63–65. The clock “ticks” with a signature period in each species14, which can be used as a surrogate to investigate mechanisms of inter-species differences in developmental timing66–68 (Box 2). In addition to the diversity in tempo, the exact network components and topology also vary in different species despite conserved features1,19. Among the cyclic genes, members of the hairy and enhancer of split (Hes/her) family of basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors, which are vertebrate homologues of the pair-rule gene hairy required for normal segmentation in Drosophila, are strikingly conserved across species69 (Fig.3a). Components of the Notch signaling pathway also oscillate in all vertebrate species studied, although their precise identity can be different69. For example, Lfng gene expression oscillates in mice and chicken but not in zebrafish70–76. Furthermore, targets of the FGF (e.g., DUSP4, SPRY2) and WNT (e.g., AXIN2, DKK1) signaling pathways display oscillations in mice and humans69. These different oscillators appear to be linked, as demonstrated in mouse explant cultures where periodically pulsing Notch inhibitor could entrain the oscillating dynamics of a WNT target40,77. Additionally, an expanding list of oscillating components with different phase relationships has been revealed in human and mouse in vitro models32, providing an opportunity to systematically investigate the clock topology and its evolutionary conservation.

Box2 – Tempos of the segmentation clock illuminate mechanisms of developmental timing.

The rate of embryonic development, or developmental timing, varies significantly across vertebrate species despite a general similarity in the sequence of developmental events. The conserved segmentation clock illustrates this notion as it oscillates with a signature period in different vertebrate species14: approximately 30 minutes in zebrafish, 90 minutes in chicken, 100 minutes in corn snake, 2.5 hours in mouse, and 5 hours in human. Understanding the mechanisms underlying these different clock tempos will shine light on species-specific developmental timing. Recent in vitro models derived from stem cells of different species have opened the door for in-depth investigations. Comparing the murine and human segmentation clock in vitro, it was proposed that the tempo difference arises from the cell-autonomous differences in global biochemical reaction rates66. Swapping genomic sequences of the core gene HES7 did not alter the overall tempos of the clock. The degradation and expression delays of HES7 were found to be slower in human cells, and the measured parameters of biochemical reactions accounted for the period differences in mathematical simulations. A further study proposed that the differential biochemical reaction speeds are brought about by species-specific metabolic rates67. Using similar in vitro systems recapitulating segmentation clock oscillations, the mass-specific metabolic rate of human cells was measured to be slower than that of mouse cells. Pharmacologically impairing the cellular NAD+/NADH redox balance led to lowered rates of global protein translation and slowed clock oscillation, while increasing the NAD+/NADH ratio sped up the clock. These quantitative results thus support a hierarchy wherein global metabolic rate determines translation and biochemical reaction speed to control the tempo of the segmentation clock. With recent adaptation using pluripotent stem cells from diverse species68, in vitro models of the segmentation clock provide a broader platform to decode mechanisms of developmental timing.

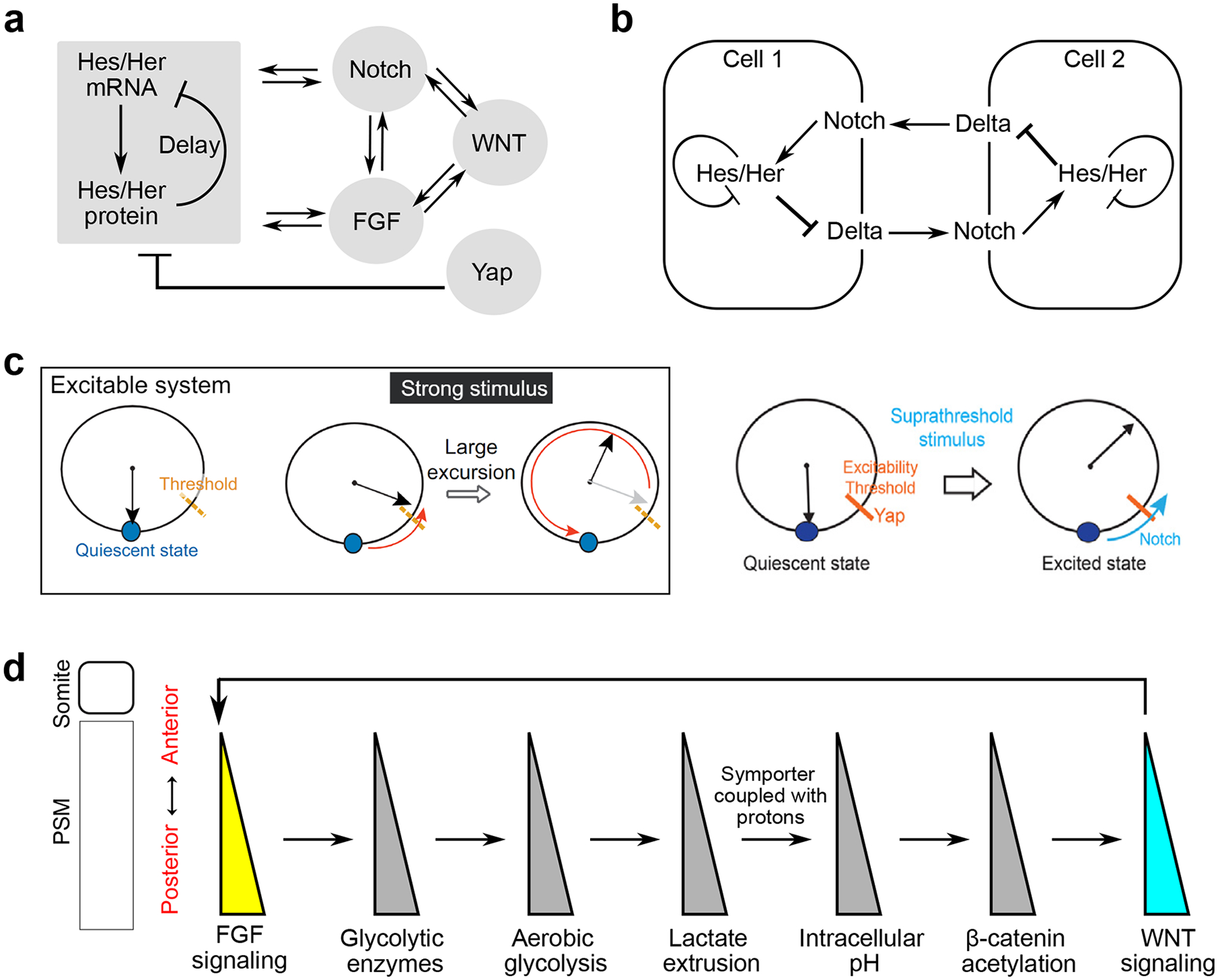

Figure 3. The segmentation clock and gradients along the PSM.

a. The hairy and enhancer of split (Hes/her) family of transcription factors are the core components of the segmentation clock. They generate cell-autonomous oscillations due to time-delayed transcription repression by protein accumulation. They are intricately linked with oscillators of Notch and FGF signaling, which are interconnected with oscillating WNT targets. Yap signaling represses the cell-autonomous Hes/her oscillations22.

b. Local synchronization of PSM cell oscillation is mediated by Notch signaling. Notch signaling regulates the expression of Hes/her transcription factors, which in turn inhibits the expression of Notch ligand Delta. Notch signaling transmitted from adjacent cells thus can fine-tune the oscillation profiles of Hes/her in a given cell.

c. An excitable system can be analogized to the pendulum. After a weak stimulus below the threshold, the system will locally return to its initial quiescent state. In response to a strong stimulus crossing the threshold (suprathreshold), the system does a large excursion before coming back to its initial state. The segmentation clock can be modeled as an excitable system22. It is proposed that Yap signaling regulates the threshold of excitability, while Notch signaling serves as the suprathreshold stimulus that triggers a pulse of activity. Reproduced with permission from REF.22.

d. The interacting signaling and metabolic gradients along the PSM. The posterior-to-anterior FGF signaling gradient leads to the graded transcription of rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes120. Thus, cells in the posterior PSM experience a higher level of aerobic glycolysis that leads to more lactate extrusion. As the extrusion is mediated by the monocarboxylate symporters coupled to protons, these cells end up having higher intracellular pH or reduced acidity. This in turn promotes β-catenin acetylation in the posterior PSM, reinforcing the posterior-to-anterior WNT signaling gradient118. WNT and FGF signaling gradients are further intertwined through protein phosphorylation and transcriptional cross-regulations47,130.

Although earlier studies concluded that isolated chicken and mouse cells could not oscillate in vitro36,78, defined conditions can support autonomous oscillations22,26. Primary cells isolated from zebrafish tailbud bearing a fluorescent reporter driven by the promoter of a cyclic gene display sustained oscillations in medium containing FGF8 (ref38). Elevated Yap signaling in isolated mouse and human cells blocks the clock oscillations while maintaining PSM identity22. Yap inhibition can restore sustained oscillations with the appropriate species-specific period in isolated cells, even when Notch signaling is pharmacologically inhibited22,26. These observations suggest that oscillations are intrinsic and do not need cell-cell contact. These cell-autonomous oscillations were proposed to arise from time-delayed negative feedback loops mediated by the short-lived Hes/her core proteins, which are transcriptional repressors79–86 (Fig.3a). Oscillation arises due to the delay between Hes/her gene transcription and protein accumulation that inhibits their own transcription79. Several cyclic targets, such as Sprouty/Dusp genes or Dkk1/Axin2, encode respectively negative feedback inhibitors of the FGF and WNT pathways and they were also proposed to contribute to the negative feedback in mice47,87. Additionally, a strong production rate, or overshooting of the steady state, was proposed to ensure the robustness of oscillations88. In zebrafish, the paired clock genes her1 and her7 are closely linked in the same chromosomal neighborhood, and they display transcriptional co-firing and correlated transcript levels during clock oscillations88. Disruption of this chromosomal adjacency in mutants resulted in less precise co-transcription and defective oscillation. Thus, co-transcription may elevate the RNA production rates of clock genes to provide the overshooting that supports sustained oscillations88.

In the PSM, clock activities from individual cells are coordinated as propagating waves in a posterior to anterior direction. The local synchronization of the oscillation phase among neighboring cells is controlled by Notch-mediated cell coupling89. As the Hes/her genes underlying the cell-autonomous oscillation are regulated by Notch signaling, the period and phase in one cell can be fine-tuned by the Notch signaling input transmitted from neighboring cells (Fig.3b). Indeed, the period of autonomous oscillation displayed in isolated PSM cells appeared longer than the period of coupled cells in the PSM tissue38,90. This Notch-dependent mechanism was first proposed in zebrafish, with the cyclic expression of the Notch ligand DeltaC acting as a synchronization mediator64,91–94. The synchronization role of Notch signaling was also confirmed in mouse embryos, explants, and human in vitro cultures22,26,39,95. In mice, cyclic Delta-Like-1 (DLL1) regulates the synchronous oscillation95,96 and its optogenetic induction was able to entrain the oscillation of the clock gene Hes197. Another type of Delta ligands – DeltaD in zebrafish and DLL3 in mice – modulates wave dynamics but does not display oscillatory expression91,93,98–100. The coupling delay – the time delay in intercellular Notch signaling transmission from one oscillator to the next – has emerged as a key parameter modulating the intrinsic period in the collective context101. For example, increasing the copy number of DeltaD in zebrafish – potentially shortening the coupling delay – accelerated oscillations102. A correct coupling delay of intercellular Notch signaling is essential for proper wave dynamics90,94,97,103. Strikingly, Lfng deletion in mice led to asynchronous oscillations in the PSM but normal period and amplitude in isolated cells90. LFNG controls the synchronized oscillation by delaying the signal-sending process of intercellular Notch signaling transmission, and its absence caused asynchronous oscillation with dampened amplitude90. Further, spatial modulation of the coupling delay could bring about complex wave patterns in space. As waves of clock activities travel along the PSM, their speed progressively slows down1,19. That is, the oscillation period in the anterior PSM is longer than that of the posterior PSM. What controls this frequency gradient is not clear, but as the Notch-mediated coupling delay modulates the oscillation period90,94,102,104–106, an increasing coupling delay towards the anterior PSM has been hypothesized to underlie this phenomenon94,103,107. Protein production delay108 and gradients of FGF and WNT signaling26,33,109,110 have also been proposed to govern the frequency gradient. Additionally, Notch signaling plays complex roles in regulating the amplitude22,93,111 and maintenance112 of clock oscillations, but appears dispensable for the onset of oscillations113,114 during embryo development.

Fascinating emergent properties of the clock were revealed through a series of in vitro studies. Dissociation and reaggregation assays using mouse embryo tail bud cells demonstrated the remarkable self-organizing capability of PSM cells in forming spatiotemporal wave patterns39. In these experiments, collective wave patterns emerged de novo in aggregates of randomly mixed mouse PSM cells dissociated from all regions of the PSM in a Notch-dependent fashion39. These argue against the existence of special pacemakers and highlight the system-level integration of the clock oscillation. Without Yap inhibition, dissociated mouse or human PSM cells failed to display autonomous oscillation when seeded at low density22,26. However, a critical seeding density promoted the transition from quiescence to sustained oscillation in individual cells, with Notch signaling necessary but not sufficient for sustained oscillations in this context22. This quorum sensing phenomenon led to propose that the clock functions as an excitable system controlled by Notch and Yap signaling22. In this model, Notch serves as the excitation stimulus and Yap regulates the excitability threshold (Fig.3c).

Signaling and metabolic gradients.

Gradients of FGF and WNT signaling have long been identified along the PSM of vertebrate embryos, with higher signaling levels in the posterior region115. These are proposed to be established by spatially restricted transcription of signaling ligands47,49. Tailbud cells actively transcribe these ligands as shown for FGF8, but their descendants in the PSM stop transcribing FGF8 once they enter the PSM territory from the progenitor domain49. Over time, mRNA and protein decay as the relative position of the cell in the PSM becomes more anterior due to posterior elongation movements. This hourglass-like timing mechanism based on mRNA decay leads to the formation of a dynamic posterior-to-anterior FGF8 mRNA gradient which accompanies the elongation movements49. At the same time, an anterior-to-posterior counter gradient of Retinoic acid signaling is established through a source-sink mechanism by Retinoic acid metabolizing enzymes, with the biosynthetic enzyme RALDH2 highly expressed in anterior PSM and somites while the RA-degrading enzyme CYP26A1 is expressed in the tailbud116,117. These signaling gradients are reconstituted in mouse and human stem cell-based organoids that display polarized elongation32,33. Interestingly, the 2D in vitro models of paraxial mesoderm recapitulate the decreasing signaling gradients in time rather than in space. In these systems, nuclear β-catenin and phosphorylated ERK (pERK) levels display temporal decrease synchronously in all cells during differentiation26,118.

Recent studies identified a posterior-to-anterior gradient of glycolysis in the PSM of chicken and mouse embryos118–121. A temporal gradient of glycolysis is also recapitulated during the differentiation of induced human PSM cells118. Cells in the tailbud and posterior PSM exhibit a high level of aerobic glycolysis, reminiscent of the signature of cancer cells experiencing the Warburg effect119,120. This gradient is established by the graded posterior-to-anterior transcription of rate-limiting glycolytic enzymes along the PSM controlled by FGF signaling120. Disruption of the glycolytic gradient leads to defected cell motility, axis elongation, and PSM differentiation119,120. The glycolytic activity also serves as an important link between the parallel WNT and FGF signaling gradients along the PSM118 (Fig.3d). As high glycolysis in posterior PSM cells increases lactate extrusion coupled to protons via the monocarboxylate symporters, these cells experience higher intracellular pH. This reduced acidity in turn creates a favorable chemical environment for non-enzymatic β-catenin acetylation promoting WNT signaling for paraxial mesoderm specification118.

Interactions between the clock and gradients.

Although often described as separate entities, the clock and gradients are intricately interconnected throughout the PSM. On one hand, the signaling levels and metabolic activities have emerged as important players in regulating the profile of clock oscillations. Initiation of Hes/her oscillations is regulated by FGF signaling in both mouse and zebrafish embryos122–125. For example, FGF4 is required to maintain critical expression level and normal oscillation pattern of Hes7 (ref126). In vitro, a combination of signaling cocktails including FGF can sustain oscillations in dissociated cells or explants22,38. Using 2D cultures of induced human PSM cells, FGF signaling was directly shown to modulate both the phase and period of HES7 oscillation26. Furthermore, in human PSC-derived organoids and microprinted PSM colonies, global addition of FGF4 accelerated HES7 oscillation and abolished phase differences across the PSM33. Thus, FGF could play a role in the control of the frequency and phase gradients along the PSM. In addition, metabolic inputs can also regulate the period of the clock, since modulating the cellular NAD+/NADH redox balance downstream of the electron transport chain can slow down or accelerate clock oscillations67. Thus, the signaling and metabolic gradients along the PSM might contribute to the tissue-level dynamics of clock activities such as the anteriorly slowing down of wave propagation.

The fact that FGF and WNT signaling are involved in the posterior gradient system and that their target genes display oscillatory expression has long represented a conundrum for the field. FGF signaling oscillations were first identified based on the periodic expression of target genes such as Snail1 and Snail2 or pathway inhibitors including Dusp and Sprouty87,127. In mouse and zebrafish, the PSM exhibits oscillations of ERK phosphorylation (pERK) downstream of FGF signaling128,129. In mice, the pulsatile pERK gradient is linked to the periodic expression of Dusp4 downstream of Hes7128. As DUSP4 periodically dephosphorylates ERK, the pERK gradient displays pulsatile dynamics alternating between a steep and shallow pattern. Similarly in zebrafish, the clock periodically projects its dynamics onto the pERK gradient although the molecular mechanism is unclear129. In clock mutants of both species, the pERK gradient displays a steady pattern. This oscillatory pERK gradient remains to be characterized in other species including in human in vitro models. The existence of a regulatory loop formed between WNT and FGF pathways in the posterior PSM118,130 suggests that oscillations of FGF signaling could entrain periodic WNT activity. While there is evidence for periodic expression of several known WNT targets such as Axin2 or Dkk1 (ref27,40,47), so far, there is no evidence of periodic regulation of beta-catenin nuclear shuttling23,37. Therefore, the mechanism controlling WNT oscillations remains poorly understood.

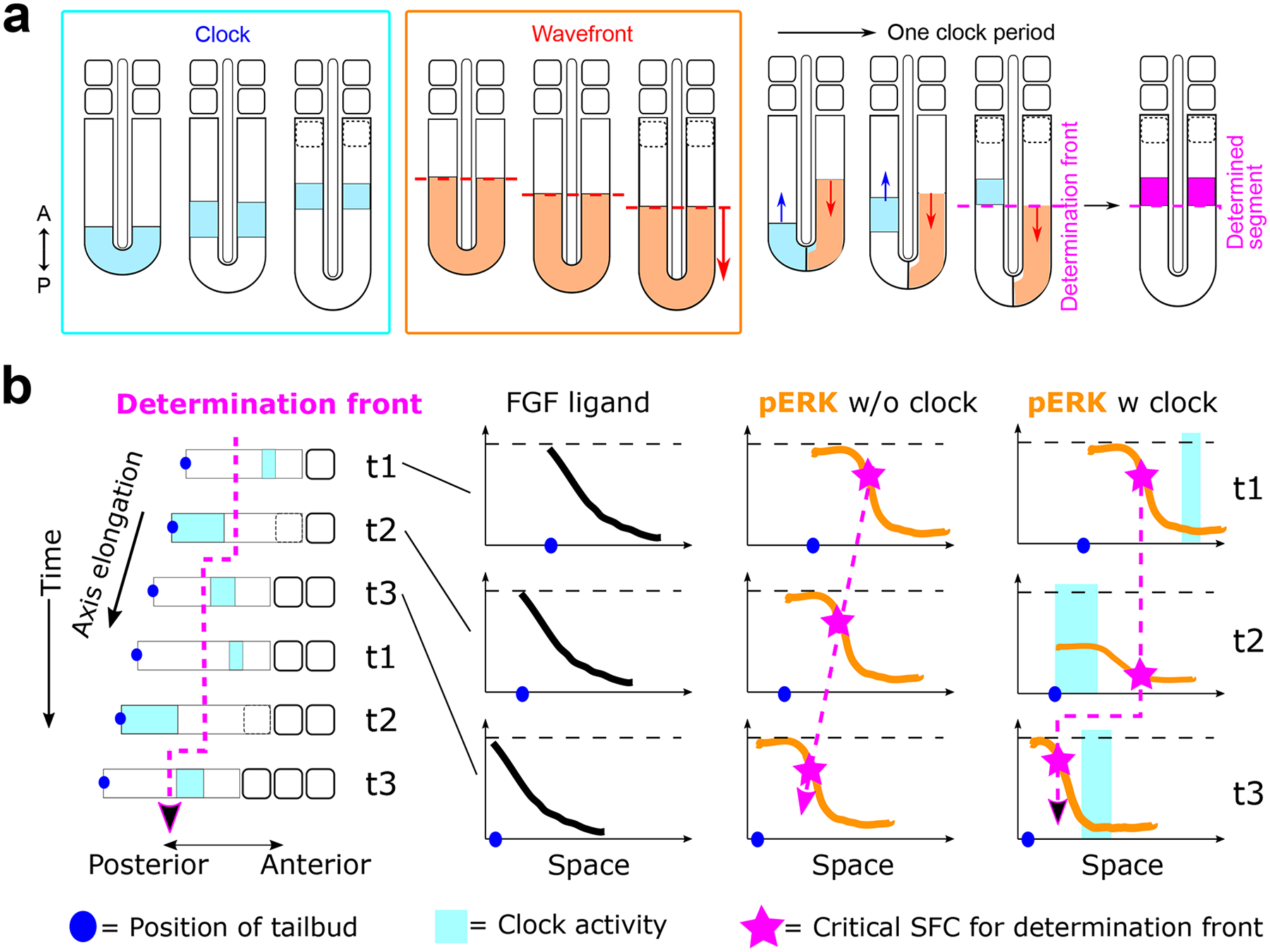

Segmental determination in the anterior PSM

How does the symphony of dynamic events in the posterior PSM direct segmental determination in the anterior PSM? The clock and wavefront model has served as an influential general concept explaining the periodic prepattern that leads to somite formation131. Inspired by the mathematical theory of catastrophes, the classic model proposes that clock and wavefront are two independent entities which together trigger segmental determination. In the model, an oscillator or clock controls the oscillation of PSM cells between a somite-forming and non-forming state but only a specific phase of the oscillation permits differentiation in response to a posteriorly travelling front of maturation (wavefront). When the right phase of oscillation meets the wavefront in the anterior PSM, at a level which was subsequently termed determination front132, an abrupt change in cell properties (the catastrophe) is triggered, resulting in somite formation (Fig.4a). Thus, the tempo of segment determination is set by the oscillator, while the size of the segment represents the distance travelled by the wavefront during one cycle of oscillation. This conceptual framework is now supported by the discovery of the segmentation clock serving as the proposed oscillator while the FGF/WNT signaling gradients along the PSM provide the wavefront37,47,132–137. Extensive studies from model embryos have now revealed cascades of molecular events associated with segmental determination.

Figure 4. The clock and wavefront model and clock-dependent oscillatory gradient (COG) model.

a. In each cycle of somite formation, activity of the segmentation clock (cyan blocks) initiates in the posterior PSM and propagates anteriorly. At the same time, morphogen gradients defining the wavefront (orange dotted line) regress posteriorly as the body axis elongates. When the right phase of the clock oscillation meets the wavefront at anterior PSM, they together specify the determination front that marks the boundary of the future somite (magenta dotted line). Black dotted outlines represent the forming somite, and the magenta band represents a determined segment.

b. The COG model proposed that the stepwise progression of the determination front (magenta dotted line) is brought about by the oscillatory dynamics of the pERK gradient combined with SFC sensing129. The FGF ligand gradient regresses steadily with the posterior elongation of the body axis. In the absence of segmentation clock, the pERK gradient simply regresses posteriorly, displaying a similar profile at all time points. The critical SFC value, above which the determination is committed, corresponds to the same relative position along the pERK gradient and thus moves posteriorly in a smooth manner. With a functional clock, the pERK gradient oscillates and so does the position with the critical SFC value in each pERK profile. SFC is defined by Δp/p, hence the value depends on both the local slope of the gradient (Δp) as well as the absolute pERK level (p). When the clock activity (cyan square) starts in the posterior PSM (t2), it lowers the pERK amplitude and makes the slope shallower. With both p and Δp decreasing, the position with the critical SFC value shifts towards the lower end of the pERK profile, and thus appears stalled in space as the body axis elongates posteriorly. When the clock activity reaches mid-PSM (t3), pERK levels in this region decreases. At the same time, pERK level in the posterior PSM recovers its amplitude resulting in a steeper slope. The position of the critical SFC suddenly moves uphill in the new pERK profile and the determination front thus jumps posteriorly to the next position. When the clock activity moves to the anterior PSM (t1), the pERK profile and SFC are not affected much. As the cycle repeats, the movement of the determination front alternates between arrest and posterior jump, leading to its stepwise progression.

In response to the clock signal, a prepattern of gene expression is initiated by the mesoderm posterior (MESP) family of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors138,139, such as Mesp2 in mice/humans and mespb in zebrafish, which are transiently expressed in the anterior PSM. The periodic expression of Mesp2 in mice is intricately regulated by multiple inputs140. First, the TBX6 transcription factor directly binds the Mesp2 enhancer and is required for Mesp2 expression141,142. The anterior border of Tbx6 expression thus sets the anterior limit of the Mesp2 expression stripe. Second, Notch signaling positively regulates Mesp2 while FGF negatively regulates its expression128,141–144. Given that Tbx6 is expressed throughout most of the PSM, the posterior limit of the Mesp2 expression stripe is defined by both periodic Notch activity from the clock and the oscillatory FGF signaling gradient. As the clock wave progressively slows down, it generates a gradually narrowing band of synchronized Notch activity travelling toward the anterior PSM141,142,144. Due to the oscillatory dynamics of the FGF signaling gradient, the pERK levels in the anterior PSM oscillate in an on-off pattern and periodically enable the group of cells in the Notch activation band to activate Mesp2 expression128. Once expressed, MESP2 in turn triggers the expression of its targets Ripply1 and Ripply2 to destabilize TBX6 protein in a ubiquitin-dependent manner142,145–147, establishing the anterior limit of the next Mesp2 expression domain. Thus, RIPPLY proteins indirectly suppress Mesp2 expression, which is also influenced by Retinoic Acid148. In zebrafish, the RIPPLY-mediated TBX6 protein degradation is conserved, although the regulation of ripply genes expression is mediated directly by her genes and ERK activity, independent of mesp genes149–153. It is worth noting that the expression of MESP genes does not exactly correspond to the determination front136,137,154–156. Microsurgical inversions of somite-wide domains have mapped the level of the determination front in the anterior PSM of the chicken embryo132. These experiments showed that it lies posteriorly to the MESP2 expression stripe. The wavefront appears to be approximately located at the level of the anterior boundary of the Mesogenin1 (MSGN1) domain which defines the first sharp segmental boundary along the PSM14. Accordingly, heat-shock experiments in zebrafish suggest that segmental commitment occurs four to five somitic cycles prior to the physical separation of somites, while mespb expression is first detected about two segment length posterior to the forming somite136,137,154.

Then what is exactly the determination front, where spatiotemporal information is precisely instructed by the clock and wavefront? It was initially proposed to be a simple threshold of FGF and/or WNT signaling below which the cells are competent to differentiate once in the right phase of the clock cycle47,132,133. This notion is supported by multiple experiments, where altering the expression levels of WNT and FGF ligands predictably shifts the segment boundary and somite size in accordance with the concept of a travelling wavefront47,132,133. It was further proposed that opposing Retinoic acid and FGF-WNT gradients together define a bistable domain allowing segment specification157. However, recent quantitative investigations using zebrafish explants argue against using absolute signaling levels representing the determination front and suggest that the critical parameter is the spatial fold change (SFC) of the pERK gradient23. SFC is defined by the ratio between the local slope of the pERK gradient and the absolute pERK level. This proposed mechanism computes the signaling level difference between neighboring cells at a given time and can provide robustness against amplitude variations of absolute signaling levels23. When the SFC associated with the last presumptive somite boundary was calculated to represent the determination front, the value was shown to be fixed at ~22% during all stages of somitogenesis and under multiple perturbed conditions23.

A variety of conceptual variations from the original clock and wavefront model have been proposed. Notably, the clock-dependent oscillatory gradient (COG) model129 considers the oscillatory clock as an upstream input to the wavefront rather than an independent entity as in the classic clock and wavefront model. Strikingly, periodic inhibition of FGF signaling with chemical compounds is sufficient to rescue the defective segmentation in zebrafish mutant lacking a functional clock129. This suggests that the clock primarily serves as an inhibitory regulator of FGF signaling dynamics. Altogether, the model combines this functional hierarchy with the SFC sensing mechanism to explain the discrete progression of the determination front129 (Fig.4b). In each clock cycle, the anteriorly propagating stripe of her expression transiently alters both the amplitude and the slope of the pERK profile, conferring oscillatory dynamics to the otherwise smoothly regressing pERK gradient downstream of the FGF ligands. As the SFC is jointly determined by both the local slope and the absolute level of pERK, position with the critical SFC value for the determination front moves discretely in a stepwise manner (Fig.4b). In the absence of the clock, the determination front progresses continuously reflecting only the posterior regression of the FGF signaling ligand. The importance of this stepwise determination mechanism in patterning and morphogenesis is discussed in the next sections. The molecular mechanism that cells use to detect and interpret the SFC remains to be elucidated.

Alternative models further break away from the clock and wavefront by proposing that the positional information for segment boundary is encoded solely by clock oscillations. In the mouse tailbud explant system, segments are formed starting from the periphery and are progressively scaled with the size of the remaining central PSM-like tissue21. In this system, the phase gradient of Lfng oscillation in the shrinking PSM region also scales with the forming segment size. It was proposed that a critical property difference between neighboring oscillators – the phase or amplitude gradient for instance – determines segmental boundary21,158,159. Further, it was suggested that the phase relationship between different sub-oscillators is important for segmental positioning. The Notch, WNT and FGF sub-oscillators display a shifting phase relationship along the PSM127. While Notch and FGF target activation is initially in phase in the posterior PSM, their different wave kinetics results in them becoming out of phase at the level of the forming segment128. This dynamic control of the phase differences was proposed to control segment determination in the anterior PSM. Also, WNT and Notch waves are out of phase in the posterior PSM but become in phase when they reach the anterior PSM, due to different travelling velocities of the waves40. Forcing out-of-phase WNT and Notch oscillators in the anterior PSM of mouse explants with microfluidic devices led to impaired PSM dynamics and segment formation40. Thus, the intracellular phase information of different oscillators could contribute to positional information encoding as well. An additional model combines clock oscillations with a local, self-organizing Turing mechanism to achieve segmental determination160. Overall, given the close mutual influence between the clock and gradients, it is possible that the key properties used to define segmental determination in these different classes of models might be correlated. Further studies simultaneously monitoring these key properties are needed to illuminate whether these model variations represent fundamental differences or either side of the same coin.

Somite antero-posterior polarity patterning

Soon after its determination, the forming segment becomes subdivided into an anterior and a posterior compartment17,18. Once established, the anterior and posterior compartments of each somite express signature genes and develop distinct properties, conferring periodic characteristics to the body axis of vertebrates17,18. They instruct the development of vertebrae, which are formed from the fusion of the posterior compartment of a somite with the anterior compartment of the next posterior somite161. They also play an instrumental role in establishing the segmental features of the peripheral nervous system since only the anterior somitic compartment is permissive to the migration of peripheral axons and neural crest cells162. This antero-posterior (also known as rostral-caudal) polarity is specified in the anterior PSM before epithelial somite formation. This contrasts with somite Dorso-Ventral patterning which results in sclerotome and dermomyotome formation and occurs after somite formation in response to signaling inputs from surrounding tissues163. Thus, the establishment of somite antero-posterior patterning is intrinsically wired in the general machinery of somitogenesis.

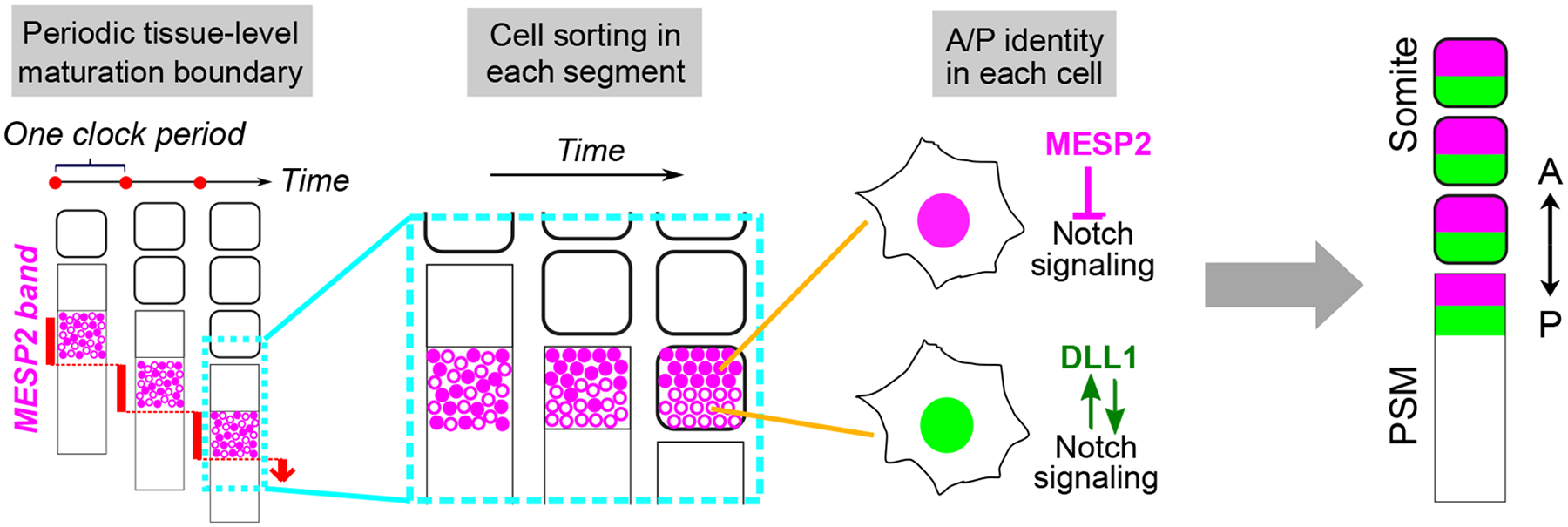

The master transcription factors of the MESP family are both necessary and sufficient to establish anterior and posterior cell identities during somitic patterning143–146. In mouse, after its initial induction in a striped domain in the anterior PSM, Mesp2 expression is rapidly confined to the anterior portion of the forming segment during the next somitic cycle144. This symmetry breaking marks the nascent domains of future anterior and posterior somitic compartments. In both mice and zebrafish, as well as in human organoids, deletion of MESP genes leads to expanded posterior somitic identity while overexpression gives rise to increased anterior identity31,138,143,150,164. The anterior fate-promoting role of MESP2 is mediated via Notch signaling in mice143,144,165,166, while the mechanism in zebrafish remains unclear150. Knock-in of a dominant-negative form of the Notch signaling mediator RBP-j in the mouse Mesp2 locus is sufficient to rescue the somite polarity defects in Mesp2-null embryos167. Therefore, the major role of MESP2 is to suppress Notch signaling activity. This occurs by destabilizing the NICD complex co-activator Mastermind-Like-1167. Thus, MESP2 requires Notch signaling for its initial expression as described in the previous section, but then it negatively regulates Notch activity140. In the absence of Mesp2, cells in the posterior somitic domain experience high Notch signaling driven by a positive feedback loop involving the Notch target gene Dll1 (ref143,144). Although MESP2 directs the onset of anterior or posterior fate divergence, maturation of these identities and the establishment of polarity patterning is a progressive process involving several players such as TBX18, UNCX, and FGFR1 that exhibit complex spatiotemporal regulation125,168–171. The complex gene regulatory networks involved in the specification of somitic antero-posterior identities remain to be thoroughly characterized.

How the initial symmetry breaking resulting in the specification of the anterior and posterior domains is achieved in the forming segment is incompletely understood140. Recent studies using human stem cell-derived organoid models identified cell sorting as an integral player underlying this patterning process31. Live imaging of a fluorescent reporter tracking MESP2 expression in human organoid models showed that MESP2 is first induced in a heterogeneous fashion among cells of the forming segment31. This salt-and-pepper distribution of expression levels spanning the newly specified segmental domain contrasts with the traditional view of a homogeneous synchronized activation of MESP2 in this domain143. Indeed, this initial heterogeneous Mesp2 expression was also confirmed in chicken and mouse embryos31 but live cell tracking remains to be performed to characterize the cell sorting mechanism in vivo. Following transient activation resulting in highly heterogeneous expression levels of MESP2, cells rapidly sort based on MESP2 expression levels. This sorting occurs within a clock cycle, establishing MESP2-high and MESP2-low cell clusters that respectively mature into anterior and posterior somitic compartments31. When cells from later stage organoids are dissociated and reaggregated, they fail to sort out to recreate the segregated antero-posterior compartments. This suggests that the cell sorting capability is only transient, corresponding to the MESP2 expression phase31. Many questions regarding the molecular mechanism of cell sorting and conservation across species remain, but these findings showcase the exciting power that in vitro systems offer in illuminating developmental biology.

Somite epithelization appears to be largely independent from antero-posterior patterning. Mouse embryos can generate epithelial somites of entirely anterior or posterior identity following inhibition or overactivation of Notch signaling165,172. The human PSC-derived in vitro model segmentoid reproduces most of the features of the clock and wavefront system. These organoids display alternative stripes of antero-posterior gene expression even when somite epithelialization is pharmacologically inhibited31, as is observed in Paraxis-null mutant mice173. Therefore epithelial somite morphogenesis and anteroposterior polarity patterning can operate independently29,31,172–176. The segmentation clock, on the other hand, is required for establishing antero-posterior polarity166,175. However, the clock is dispensable for the acquisition of anterior and posterior fates in individual cells, as demonstrated in Hes7-null or conditional Fgfr1-deletion mouse embryos, as well as human organoids31,125,177. It is required for the organization of anterior and posterior somite cells into repeated spatial patterns, which is mediated through the clock-conferred MESP2 dynamics at the tissue level31. In the presence of clock oscillations, the determination front progresses in a staggered fashion, resulting in the periodic, stepwise progression of the initial striped domain of MESP2 expression31,128,129,137,178. Given that cell sorting capability is transient during differentiation31, the synchronized onset of MESP2 expression among a group of cells can provide a maturation boundary that restricts cell sorting within the forming segment. In mutant embryos and organoids lacking HES7, MESP2 induction progresses continuously from anterior to posterior in the PSM and cells with anterior and posterior identities fail to segregate appropriately31,128,177.

Altogether, the level of MESP2 expression in PSM cells dictates the prospective antero-posterior identities as well as local cell sorting, while its rhythmic and synchronized activation in the future segmental domain ensures periodic spatial regularity. Combining the recent model of symmetry breaking31 with models of fate specification140, here we propose a three-step framework (Fig.5) of somite antero-posterior patterning: (1) the clock-and-wavefront system periodically triggers the salt-and-pepper MESP2 expression following segment specification at the determination front; (2) MESP2-high cells are rapidly sorted to the anterior region while MESP2-low cells are sorted to the posterior; (3) Cells in each compartment acquire anterior or posterior identities based on initial MESP2 levels and additional Notch-dependent gene regulatory networks. Some components can regulate multiple steps, for example, the segmentation clock might also confer directionality to cell sorting or reinforce the gene regulatory network for fate maturation.

Figure 5. A framework of somite anteroposterior polarity patterning.

Three processes at different scales generate the repeated stripe patterning along the paraxial mesoderm. The stepwise segmental determination controlled by the clock and wavefront system leads to discrete progression of MESP2 expression band in the anterior PSM. In each determined segment, cells are simultaneously triggered to express MESP2 with heterogenous levels. Then in one clock period, cells with high MESP2 levels are rapidly sorted to the anterior compartment of the forming segment while cells with low MESP2 expression move to the posterior, establishing the initial symmetry breaking of the polarity patterning31. In cells, MESP2 functions as a repressor of Notch signaling. Thus, MESP2-high cells in the anterior compartment experience suppressed Notch signaling while MESP2-low cells in the posterior compartment have high Notch signaling with positive feedback loops from Notch targets including DLL1. The differential Notch signaling promotes gene regulatory networks to mature the anterior or posterior identity in each cell.

Somite epithelial morphogenesis

Following the prepattern of gene expression laid down by the clock and wavefront system, cascades of molecular, cellular, and physical events are set off to promote mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) and somite boundary formation in the anterior PSM140,179. The MESP family of transcription factors connects the genetic prepattern to morphogenesis by controlling the expression of Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and Ephrin ligands164. EphA4 expression is restricted posteriorly to the forming boundary, while Ephrin ligands such as EphrinB2 and EphrinA1 locate anteriorly to the prospective boundary164,180,181. The Eph-Ephrin interactions generate bi-directional signaling facilitating the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix (ECM) at the interface to form the inter-somitic fissure. In zebrafish, Eph-Ephrin signaling modulates actomyosin activation to direct Integrin activation and clustering at the interface between the ligand and receptor expressing domains, which in turn promotes fibronectin matrix assembly and physical boundary formation182,183. In chicken, phosphorylated EphrinB2 suppresses CDC42 activity to promote efficient epithelialization181, in parallel with optimal activation of other RHO family small GTPases such as RAC1184 and guidance by ECM assembly185–187. The morphogenic process is also regulated by a variety of cell-cell and cell-ECM adhesion molecules, whose expression is regulated by the bHLH transcription factor Paraxis (TCF15)188,189. Cadherin-2 (CDH2 or N-Cadherin) and Cadherin-11 cooperate to maintain the epithelial morphology of somite176. CDH2 promotes intercellular Integrin repression within the PSM and the forming segment thus restricting ECM assembly to the tissue boundary190. Its polarized distribution in a forming somite, with a higher level at the posterior half, was proposed to accelerate the epithelization of the posterior part facilitating tissue separation from the PSM191,192. This distribution is established via increased endocytosis of CDH2 in the anterior half by enriched Paraxial Protocadherin (PAPC or PCDH8)191. As PAPC is dynamically regulated by MESP2 in the anterior PSM191,193, it serves as another link between the clock-and-wavefront system and somite morphogenesis.

Recent advances have led to a new understanding of epithelial somite morphogenesis. The posterior primitive streak of chicken embryos treated with a BMP inhibitor gives rise to epithelial somite-like rosettes simultaneously without oscillations of cyclic genes or MESP2 expression175. This was confirmed in human organoids where somitic rosettes can form despite deletion of the core clock component HES7 or the master transcription factor MESP2 (ref31). Formation of these rosettes is blocked when myosin activity is pharmacologically inhibited. Moreover, cells dissociated from somite-stage organoids can re-form rosettes again upon reaggregation, without going through the prior genetic cascades31. These together suggest that epithelial rosette-forming potential is an intrinsic feature of somitic cells, driven by local acto-myosin activities31,175. Mechanics has emerged as another important player governing somite morphology194–196. Quantitative studies of zebrafish embryos show that initial bilateral symmetry of somite boundaries is imprecise196, despite buffering by Retinoic acid signaling197. The somite antero-posterior length is adjusted after somite formation through tissue shape changes. These were proposed to be mediated by surface tension, which compensates for the initial antero-posterior imprecision by modulating the medio-lateral length196. Thus, bilateral symmetry is progressively improved, highlighting a dynamic picture of tissue shapes and mechanics. Notably, this mechanism is independent from the molecular prepattern established by the clock and wavefront system196. Whether such a mechanism operates in amniotes such as chicken or mouse remains however to be investigated.

Therefore, somite morphogenesis must be viewed as an integrated result of multiple inputs: the genetic prepattern established by the clock and wavefront system allocates a discrete group of cells for differentiation, where cascades of signaling and physical events are triggered that feed into the intrinsic machinery of rosette formation followed by mechanical fine-tuning via tissue surface tension and stresses from surrounding tissues (Fig.6a). Details of each input as well as their interacting nodes remain to be investigated. To understand somite shapes and sizes under various conditions and across species, pinpointing the major inputs for each context might be helpful in reducing the complexity (Fig.6b–e). For instance, Matrigel and Retinoic acid promote somite morphogenesis in vitro via unknown mechanisms28,29,32. In both mouse and human organoids, Matrigel upregulated the expression of a range of cell adhesion and ECM remodeling genes29,32, In human organoids, Retinoic acid signaling promoted the expression of transcription factors associated with epithelization including TCF15 (Paraxis) in synergy with Matrigel32. Thus, both Matrigel components and Retinoic acid might transcriptionally elevate the intrinsic ability of somitic cells to form rosettes, while Matrigel could also provide a favorable mechanical environment for rosette assembly (Fig.6b). Further, rosette shapes in organoids are often less regular29–32, which could reflect the lack of mechanical tuning from intricate neighboring tissues as can occur in embryos (Fig.6c). In the absence of a functional segmentation clock as in Hes7-null mice177, rosettes are irregularly assembled failing to establish proper segmentation. This suggests that the intrinsic machinery of rosette formation is intact while the defect results from a dysregulated prepattern: since absence of the clock leads to the loss of the stepwise dynamics of the determination front, discrete groups of differentiating cells cannot be regularly allocated and organized cascades of signaling events cannot be precisely established (Fig.6d). Somite size is another interesting feature that is actively regulated. In embryos and explants, the size of the newly formed somite scales with the length of the PSM21,23. While in somitoid organoids – where rosette formation is disconnected from the clock and wavefront system and instead occurs in a simultaneous fashion – the rosettes display size invariance relative to the overall size of the organoid31. This suggests that the intrinsically formed rosettes have a typical length scale and the scaling phenomenon might rely on other contributing inputs. It appears that the scaling could be achieved mainly through modulating the prepattern generated by the clock and wavefront system198: the size of the prepattern determines the amount of material for rosette assembly and eventual somite size (Fig.6e).

Figure 6. An integrated view of somite morphogenesis.

a. Multiple inputs are integrated to generate somites with regular morphology. The clock and wavefront system periodically lays down a prepattern of gene expression. The size of the prepattern determines the number of cells that undergo differentiation altogether in this somitic cycle. In the region of the prepattern, organized signaling and physical cascades are initiated. They feed into the intrinsic ability of somitic cells to form epithelial rosettes, whose shapes are further finetuned by mechanical cues.

b. Understanding major inputs affected may be helpful to decipher somite shapes in various contexts. Matrigel, Retinoic acid, and the transcription factor Paraxis may elevate the intrinsic ability to form epithelial rosettes.

c. The irregular somite shapes often observed in stem cell-derived organoids result from futile mechanical tuning in contrast to embryos.

d. When the clock and wavefront system is disrupted as in Hes7-null mice, regular prepatterns that organize cell differentiation and signaling cascades cannot be established. Hence, somites can only be irregularly assembled reflecting the intrinsic machinery of rosette formation.

e. The phenomenon that somite size scales with PSM length might be achieved through the modulation of prepattern size by the clock and wavefront system. The prepattern size determines the number of cells that will be incorporated into a forming somite and thus its eventual size.

Conclusion and perspective

Somitogenesis lays down the blueprint of the vertebrate body plan and embodies fascinating common themes throughout development, from dynamic signal transduction to emergent cellular behaviors. Numerous experiments show that the various modules of somitogenesis can be decoupled and operated independently. Only when we fully understand each module, will we be able to start to grasp the elegant design principles of somitogenesis. The recently established in vitro models offer access to unlimited experimental material and a reductionist setup that allows intricate perturbations to yield spatiotemporal information with unprecedented resolution. They permit experiments we could only dream of and can reveal insights that are masked by the tremendous complexity of embryos. Moreover, human stem cell-derived models provide an invaluable platform to illuminate the obscure mechanisms of early human development and understand the causes of congenital diseases. Thus, it is truly an exciting time to study somitogenesis.

At the same time, integrating the mechanistically independent modules of somitogenesis represents another challenge. After all, it is the seamless coordination of these different modules that yields precision and robustness to this vital developmental process. An epithelial somite is consistently subdivided into an anterior and posterior half, even though the process of morphogenesis and AP patterning can be efficiently decoupled in vivo and in vitro. Some shared players that are engaged in all the modules might provide links for integration. For example, Notch signaling brings about the synchronization of clock oscillation, regulates the expression of the segmental genes, determines antero-posterior somite identities, etc. It is conceivable that the versatile Notch signaling components might weave different modules into a coherent machinery. Alternatively, the integration could be a result of coincidental coordination, where the distinct modules only share a common regulation factor that lies very upstream. Further studies combining in vivo and in vitro models will shine light on the system-level organization of somitogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers 5R01HD085121 (to O.P.) and K99HD111689 (to Y.M.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Y.M. and O.P. declare no competing interests.

Reference

- 1.Hubaud A & Pourquié O Signalling dynamics in vertebrate segmentation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 15, 709–721 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bulman MP et al. Mutations in the human delta homologue, DLL3, cause axial skeletal defects in spondylocostal dysostosis. Nat. Genet 24, 438–441 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sparrow DB, Guillén-Navarro E, Fatkin D & Dunwoodie SL Mutation of Hairy-and-Enhancer-of-Split-7 in humans causes spondylocostal dysostosis. Hum. Mol. Genet 17, 3761–3766 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whittock NV et al. Mutated MESP2 causes spondylocostal dysostosis in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet 74, 1249–1254 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McInerney-Leo AM et al. Compound heterozygous mutations in RIPPLY2 associated with vertebral segmentation defects. Hum. Mol. Genet 24, 1234–1242 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornier AS et al. Mutations in the MESP2 gene cause spondylothoracic dysostosis/Jarcho-Levin syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet 82, 1334–1341 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sparrow DB et al. A mechanism for gene-environment interaction in the etiology of congenital scoliosis. Cell 149, 295–306 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouman A et al. Homozygous DMRT2 variant associates with severe rib malformations in a newborn. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 176, 1216–1221 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turnpenny PD et al. Novel mutations in DLL3, a somitogenesis gene encoding a ligand for the Notch signalling pathway, cause a consistent pattern of abnormal vertebral segmentation in spondylocostal dysostosis. J. Med. Genet 40, 333–339 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparrow DB et al. Autosomal dominant spondylocostal dysostosis is caused by mutation in TBX6. Hum. Mol. Genet 22, 1625–1631 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohamed JY et al. Mutations in MEOX1, encoding mesenchyme homeobox 1, cause Klippel-Feil anomaly. Am. J. Hum. Genet 92, 157–161 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayrakli F et al. Mutation in MEOX1 gene causes a recessive Klippel-Feil syndrome subtype. BMC Genet 14, 95 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparrow DB et al. Mutation of the LUNATIC FRINGE gene in humans causes spondylocostal dysostosis with a severe vertebral phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet 78, 28–37 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez C et al. Control of segment number in vertebrate embryos. Nature 454, 335–339 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomez C & Pourquié O Developmental control of segment numbers in vertebrates. J. Exp. Zool. B Mol. Dev. Evol 312, 533–544 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuan C-YK, Tannahill D, Cook GMW & Keynes RJ Somite polarity and segmental patterning of the peripheral nervous system. Mech. Dev 121, 1055–1068 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming A, Kishida MG, Kimmel CB & Keynes RJ Building the backbone: the development and evolution of vertebral patterning. Development 142, 1733–1744 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scaal M Early development of the vertebral column. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 49, 83–91 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oates AC, Morelli LG & Ares S Patterning embryos with oscillations: structure, function and dynamics of the vertebrate segmentation clock. Development 139, 625–639 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz-Cuadros M & Pourquie O In vitro systems: A new window to the segmentation clock. Dev. Growth Differ 63, 140–153 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lauschke VM, Tsiairis CD, François P & Aulehla A Scaling of embryonic patterning based on phase-gradient encoding. Nature 493, 101–105 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubaud A, Regev I, Mahadevan L & Pourquié O Excitable Dynamics and Yap-Dependent Mechanical Cues Drive the Segmentation Clock. Cell 171, 668–682.e11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simsek MF & Özbudak EM Spatial Fold Change of FGF Signaling Encodes Positional Information for Segmental Determination in Zebrafish. Cell Rep 24, 66–78.e8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsumiya M, Tomita T, Yoshioka-Kobayashi K, Isomura A & Kageyama R ES cell-derived presomitic mesoderm-like tissues for analysis of synchronized oscillations in the segmentation clock. Development 145, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu L-F et al. An In Vitro Human Segmentation Clock Model Derived from Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Rep 28, 2247–2255.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diaz-Cuadros M et al. In vitro characterization of the human segmentation clock. Nature (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1885-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Established an in vitro system using human pluripotent stem cells to identify the human segmentation clock, together with references 25 and 27; Characterized the signaling regulations of the human segmentation clock.

- 27.Matsuda M et al. Recapitulating the human segmentation clock with pluripotent stem cells. Nature 580, 124–129 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Established in vitro systems using human pluripotent stem cells to identify the human segmentation clock, together with references 25 and 26; Modeled congenital segmentation disorders using the in vitro systems.

- 28.van den Brink SC et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal somitogenesis in gastruloids. Nature (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2024-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veenvliet JV et al. Mouse embryonic stem cells self-organize into trunk-like structures with neural tube and somites. Science 370, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanaki-Matsumiya M et al. Periodic formation of epithelial somites from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun 13, 1–14 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miao Y et al. Reconstruction and deconstruction of human somitogenesis in vitro. Nature (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05655-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Established two organoid models of human somite formation, somitoid and segmentoid; Discovered that cell sorting underlies somite anterior-posterior polarity patterning.

- 32.Yamanaka Y et al. Reconstituting human somitogenesis in vitro. Nature (2022) doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-05649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Established an organoid model of human somite formation, axioloid; Characterized the model in detail and identified a critical role of Retoid acid in somite epithelization in vitro.

- 33.Yaman YI & Ramanathan S Controlling human organoid symmetry breaking reveals signaling gradients drive segmentation clock waves. Cell (2023) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Used bioengineering tools to establish an organoid model of human trunk consisting of the neural tube and somites; Dissected roles of signaling gradients in regulating wave dynamics of clock oscillations.

- 34.Schoenwolf GC, Bleyl SB, Brauer PR & Francis-West PH Larsen’s Human Embryology E-Book (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palmeirim I, Henrique D, Ish-Horowicz D & Pourquié O Avian hairy gene expression identifies a molecular clock linked to vertebrate segmentation and somitogenesis. Cell 91, 639–648 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masamizu Y et al. Real-time imaging of the somite segmentation clock: revelation of unstable oscillators in the individual presomitic mesoderm cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 1313–1318 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aulehla A et al. A β-catenin gradient links the clock and wavefront systems in mouse embryo segmentation. Nat. Cell Biol 10, 186 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Webb AB et al. Persistence, period and precision of autonomous cellular oscillators from the zebrafish segmentation clock. Elife 5, (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsiairis CD & Aulehla A Self-Organization of Embryonic Genetic Oscillators into Spatiotemporal Wave Patterns. Cell 164, 656–667 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonnen KF et al. Modulation of Phase Shift between Wnt and Notch Signaling Oscillations Controls Mesoderm Segmentation. Cell 172, 1079–1090.e12 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Developped a microfluidic device to entrain oscillations of Wnt and Notch signaling; Proposed that the phase relationship between clock sub-oscillators encodes positional information for segmental determination.

- 41.Chal J et al. Differentiation of pluripotent stem cells to muscle fiber to model Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Biotechnol 33, 962–969 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iimura T, Yang X, Weijer CJ & Pourquié O Dual mode of paraxial mesoderm formation during chick gastrulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 104, 2744–2749 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tzouanacou E, Wegener A, Wymeersch FJ, Wilson V & Nicolas J-F Redefining the progression of lineage segregations during mammalian embryogenesis by clonal analysis. Dev. Cell 17, 365–376 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gouti M et al. A Gene Regulatory Network Balances Neural and Mesoderm Specification during Vertebrate Trunk Development. Dev. Cell 41, 243–261.e7 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Attardi A et al. Neuromesodermal progenitors are a conserved source of spinal cord with divergent growth dynamics. Development 145, dev166728 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guillot C, Djeffal Y, Michaut A, Rabe B & Pourquié O Dynamics of primitive streak regression controls the fate of neuromesodermal progenitors in the chicken embryo. Elife 10, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aulehla A et al. Wnt3a plays a major role in the segmentation clock controlling somitogenesis. Dev. Cell 4, 395–406 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chapman SC, Brown R, Lees L, Schoenwolf GC & Lumsden A Expression analysis of chick Wnt and frizzled genes and selected inhibitors in early chick patterning. Dev. Dyn 229, 668–676 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dubrulle J & Pourquié O fgf8 mRNA decay establishes a gradient that couples axial elongation to patterning in the vertebrate embryo. Nature 427, 419–422 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Streit A & Stern CD Establishment and maintenance of the border of the neural plate in the chick: involvement of FGF and BMP activity. Mech. Dev 82, 51–66 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robertson EJ Dose-dependent Nodal/Smad signals pattern the early mouse embryo. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 32, 73–79 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zinski J, Tajer B & Mullins MC TGF-β Family Signaling in Early Vertebrate Development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 10, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Loh KM et al. Mapping the Pairwise Choices Leading from Pluripotency to Human Bone, Heart, and Other Mesoderm Cell Types. Cell 166, 451–467 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nakajima T et al. Modeling human somite development and fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva with induced pluripotent stem cells. Development 145, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xi H et al. In Vivo Human Somitogenesis Guides Somite Development from hPSCs. Cell Rep 18, 1573–1585 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beccari L et al. Multi-axial self-organization properties of mouse embryonic stem cells into gastruloids. Nature 562, 272–276 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moris N et al. An in vitro model of early anteroposterior organization during human development. Nature (2020) doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Budjan C et al. Paraxial mesoderm organoids model development of human somites. Elife 11, e68925 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gribaudo S et al. Self-organizing models of human trunk organogenesis recapitulate spinal cord and spine co-morphogenesis. Nat. Biotechnol (2023) doi: 10.1038/s41587-023-01956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anand GM et al. Controlling organoid symmetry breaking uncovers an excitable system underlying human axial elongation. Cell 186, 497–512.e23 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Karzbrun E et al. Human neural tube morphogenesis in vitro by geometric constraints. Nature 599, 268–272 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gjorevski N et al. Tissue geometry drives deterministic organoid patterning. Science 375, eaaw9021 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]