Abstract

Diacyl phthiocerol esters and their congeners are mycobacterial virulence factors. The biosynthesis of these complex lipids remains poorly understood. Insight into their biosynthesis will aid the development of rationally designed drugs that inhibit their production. In this study, we investigate a biosynthetic step required for diacyl (phenol)phthiocerol ester production, i.e., the reduction of the keto group of (phenol)phthiodiolones. We utilized comparative genomics to identify phthiodiolone ketoreductase gene candidates and provide a genetic analysis demonstrating gene function for two of these candidates. Moreover, we present data confirming the existence of a diacyl phthiotriol intermediate in diacyl phthiocerol biosynthesis. We also elucidate the mechanism underlying diacyl phthiocerol deficiency in some mycobacteria, such as Mycobacterium ulcerans and Mycobacterium kansasii. Overall, our findings shed additional light on the biosynthesis of an important group of mycobacterial lipids involved in virulence.

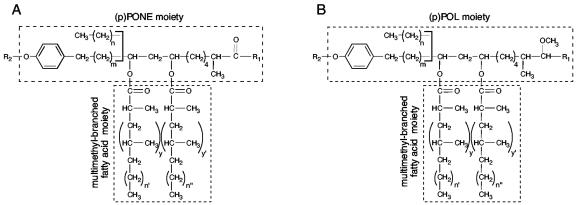

A unique feature of the mycobacteria is their outer cell wall layer. The unusual lipid composition of this layer contributes to the characteristic pathogenicity and resiliency of mycobacterial pathogens (4, 7, 8, 15, 22, 24). Among the lipids of the mycobacterial outer cell wall layer are diesters of long-chain multimethyl-branched fatty acids and β glycol-containing long-chain polyketides (PKs) (14, 15, 20, 24). These diesters, collectively referred to herein as diacylated PKs (DPs), are produced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. leprae, M. bovis, M. microti, M. africanum, M. kansasii, M. marinum, M. ulcerans, M. haemophilum, and M. gastri. With the exception of M. gastri, all these mycobacteria are pathogenic. Depending on the species, the fatty acid component of the diesters is called either mycocerosic acid or phthioceranic acid. The β glycol-containing PKs are phthiocerols (POLs), phthiodiolones (PONEs), phenolphthiocerols (pPOLs), or phenolphthiodiolones (pPONEs). The diesters of pPOLs and pPONEs are glycosylated on the aromatic ring. Finally, the difference between (p)POLs and (p)PONEs is that the former lipid family has a 3-methoxy group [or 2-methoxy in (p)POLs of the B series], whereas the latter family has a 3-keto group [or 2-keto in (p)PONEs of the B series] (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Structures of DPs. (A) Diacyl PONE and pPONE variants. (B) Diacyl POL and pPOL variants. R1, -CH2-CH3 in (p)POLs and (p)PONEs of series A and -CH3 in (p)POLs and (p)PONEs of series B; R2, glycosyl moiety; n = 20 to 22; n′, n′′ = 16 to 18; y, y′ = 2 to 4; m = 15 to 17.

Discovered over 70 years ago (39, 40), DPs have recently become the focus of intense attention after several lines of evidence indicated their role as virulence factors. Most importantly, abrogation of the production of M. tuberculosis nonglycosylated DPs (often referred to as phthiocerol dimycocerosates) was recently shown to correlate with attenuation of virulence in mouse infection models (6, 13, 33, 34, 36, 37). Furthermore, production of glycosylated DPs (usually referred to as phenolglycolipids [PGLs]) and not production of only nonglycosylated DPs (32) correlates with M. tuberculosis hypervirulence in the mouse model, and the M. tuberculosis PGLs were demonstrated to down-regulate macrophage immune function in vitro (32), hinting at a possible immunomodulatory role for these lipids. Finally, the M. leprae glycosylated DPs (PGL-1) were shown to induce nerve demyelination and mediate the predilection of M. leprae for Schwann cells. These biological activities are attributed to the trisaccharide moiety of the glycolipid (26, 31).

Despite insights into DP biosynthesis from early metabolic labeling and degradation studies (17-19) and the recent identification of PK synthase genes (e.g., pks15/1, ppsA-E, and mas) involved in the production of DPs (1, 2, 11, 23, 30, 42), our understanding of DP biosynthesis remains limited. As part of our efforts to elucidate DP biosynthesis, we have recently reported on the functional and structural characterization of M. tuberculosis PapA5, an acyltransferase believed to catalyze acylation of (p)POLs and (p)PONEs with mycocerosic acids (5, 27). In the present study, we clarify another step of the DP biosynthetic pathway, i.e., reduction of the PONE keto group. This is the first step in the conversion of (p)PONEs to (p)POLs (Fig. 2). Comparative genomics of DP clusters of diacyl (p)PONE/(p)POL-producing mycobacteria versus those of diacyl (p)POL-deficient mycobacteria allowed us to identify a conserved gene candidate encoding the predicted phthiodiolone ketoreductase. Gene complementation studies with naturally occurring diacyl POL-deficient M. kansasii and M. ulcerans validated our predicted function for the putative ketoreductase. Furthermore, we show that diacyl phthiotriol (3-hydroxy) is an intermediate in the diacyl POL biosynthetic pathway. Finally, our analysis illuminates the genetic basis underlying diacyl POL deficiency in M. kansasii and M. ulcerans.

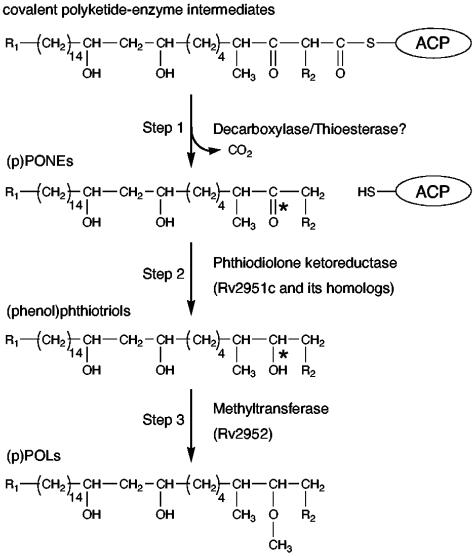

FIG. 2.

Current model for (p)PONE-to-(p)POL conversion. The PK intermediates synthesized by the (Pks1/15)PpsA-E PK synthase system are shown bound to the acyl carrier protein domain (ACP) of PpsE. The mechanism of the proposed decarboxylative release of the PK chain to produce (p)PONEs remains unknown (step 1). The next step in the scheme is (p)PONE keto group reduction to generate the hydroxyl group in the (phenol)phthiotriol intermediates (step 2). *, keto and hydroxyl groups. As proposed in this study, step 2 is catalyzed by phthiodiolone ketoreductases. The hydroxyl group is subsequently methylated to produce (p)POLs (step 3). R1, CH3-(CH2)5-7-CH2 -in the POLs and PONEs and p-hydroxy-phenyl-CH2-CH2 -in (p)POLs and (p)PONEs; R2, -CH3 (A series) or -H (B series). The timing of the reduction and methylation steps relative to esterification of the glycols with the multimethyl-branched fatty acids remains unknown. The glycols are arbitrarily presented nonesterified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and reagents.

Solvents and nonradiolabeled chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. [3-14C]propionate (56 μCi mmol−1) was acquired from American Radiolabeled Chemicals. Molecular biology reagents were from Sigma, Invitrogen, New England Biolabs, Novagene, QIAGEN, or Stratagene.

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli strains were cultured under standard conditions in Luria-Bertani medium (Difco) (35). M. tuberculosis Erdman (ATCC 35801) and M. kansasii (ATCC 12478) were grown at 37°C in either liquid Middlebrook 7H9 medium or on solid Middlebrook 7H11 medium (Difco) supplemented with 10% oleic acid-albumin-dextrose-catalase or albumin-dextrose-catalase (Becton Dickinson) as reported earlier (28). M. ulcerans (ATCC 35840) was grown in the same media but at 28 to 30°C (28). Bacterial strains transformed with plasmid pMV261 and its derivatives (see below) were selected and cultured in growth medium containing kanamycin (30 μg ml−1). The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | Cloning host | Invitrogen |

| M. tuberculosis Erdman | Wild type | ATCC 35801 |

| M. kansasii | Wild type | ATCC 12478 |

| M. kansasii/pMV261 | Contains pMV261 | This study |

| M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c | Contains pCPMm2951c | This study |

| M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c | Contains pCPMmMk2951c | This study |

| M. ulcerans | Wild type | ATCC 35840 |

| M. ulcerans/pMV261 | Contains pMV261 | This study |

| M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c | Contains pCPMm2951c | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMV261 | Mycobacterial expression vector | 41 |

| pCPMm2951c | pMV261 expressing Mm2951c | This study |

| pCPMmMk2951c | pMV261 expressing Mm2951c-Mk2951c hybrid | This study |

Sequence similarity searches and analysis.

Sequence similarity and conserved domain searches in public databases and sequence comparisons were done with BLAST programs via http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Multiple protein sequence alignments were performed using Clustal W software bundled with the MegAlign sequence alignment software package (DNASTAR, Inc.). M. marinum preliminary genome sequence data were obtained from the Sanger Institute M. marinum sequencing project database (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/M_marinum/). M. ulcerans genome sequence information was obtained from the BuruList World Wide Web server (http://genopole.pasteur.fr/Mulc/BuruList.html).

Cloning and sequencing of the M. kansasii Rv2951c homolog Mk2951c.

The Mk2951c gene was amplified from M. kansasii genomic DNA with primers Mm2951c1-f (5′-TTCGTTACGGCTTTGTCGACGCTCCGGTGCACT-3′) and Mm2951c1-r (5′-TCACAGCTTCTTCAGCCCCCGCAACACCTTGGCGTG-3′). These primers were designed based on the sequence of the M. tuberculosis Rv2951c homolog found in M. marinum (Mm2951c) and its flanking regions. M. kansasii genomic DNA was purified as reported earlier (28). Recombinant DNA manipulations were performed using standard methodologies (35). The amplified Mk2951c gene fragment (1,104 bp) was cloned using the TOPO cloning system (Invitrogen). Inserts from various independent clones were sequenced using standard methods (35).

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmid pCPMm2951c, expressing the M. marinum Mm2951c gene, was constructed as follows. An M. marinum genomic fragment encompassing the Mm2951c gene and 247 bp of its upstream region was PCR amplified from genomic DNA (gift of S. Ehrt, Weill Medical College of Cornell) with primers Mm2951c2-f (5′-GAATTCACCCGAGCGGGCTGGGGAGGCTGAGTT-3′) and Mm2951c2-r (5′-GCTAGCCGCGAACCGGCTCCGAGCGGA-3′). The fragment was cloned as an EcoRI-NheI insert into the mycobacterial expression plasmid pMV261 (41). The resulting plasmid, pCPMm2951c, was introduced into M. ulcerans and M. kansasii by electrotransformation (28). These transformants (M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c and M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c), as well as transformants carrying vector pMV261 (M. ulcerans/pMV261 and M. kansasii/pMV261), were propagated as described above.

An additional plasmid, pCPMmMk2951c, was constructed with an insert consisting of the M. marinum 247-bp fragment fused in frame to the 5′ end of the M. kansasii Mk2951c gene. The 247-bp fragment was excised from pCPMm2951c with EcoRI and ApaLI, and the Mk2951c gene coding region was amplified from genomic DNA for cloning as an ApaLI-NheI fragment using primers Mm2951c1-f (shown above) and Mk2951c-r (5′-GCTAGCTCACAGCTTCTTCAGCCCCCGCAACACCTT-3′). The amplified Mk2951c gene fragment, the 247-bp fragment, and pMV261 linearized with ApaLI and EcoRI were ligated to create pCPMmMk2951c. This plasmid was introduced into M. kansasii by electrotransformation to generate strain M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c.

Extraction of apolar lipids.

Apolar lipid fractions containing DPs were extracted from M. tuberculosis, M. ulcerans, and M. kansasii as previously described (27, 38). Briefly, cells from bacterial cultures (100 ml; optical density at 600 nm, 1.0) were harvested by centrifugation or by vacuum filtration and resuspended in 20 ml of methanol (MeOH):0.3% NaCl (10:1, vol/vol). The suspension was extracted twice with 10 ml of petroleum ether (PE). The upper layer, containing apolar lipids, was recovered, mixed thoroughly with 20 ml of CHCl3 for 1 h, and dried under reduced pressure. The resulting apolar lipid extract was resuspended in PE:CHCl3 (1:1, vol/vol) and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and mass spectrometry (MS) as described below. To obtain 14C-labeled DPs, mycobacterial cultures (50 ml; optical density at 600 nm, 0.8) were metabolically labeled by pulsing them with 10 μCi of [14C]propionate (56 μCi mmol−1) for 24 h before cell harvesting and lipid extraction. [14C]propionate is selectively incorporated into DPs and other methyl-branched lipids, facilitating analysis by radio-TLC (2, 13).

Purification of DPs.

A 1-cm column was packed 15 cm high with silica gel (35 to 70 μm, 6-nm pore diameter [Acros Organics]) and irrigated with PE:diethylether (9:1, vol/vol). Samples of extracted apolar lipids were added and eluted as 1- to 2-ml fractions. DP-containing fractions were identified by TLC analysis, pooled, and concentrated under reduced pressure. In selected cases, the recovered DPs were subjected to additional purification by preparative TLC as indicated below.

Thin-layer chromatography.

Analytical TLC was performed using aluminum-backed, 250-μm-thick Silica Gel 60 plates (EM Science or Whatman). Preparative TLC was performed on 10- by 10-cm, 250-μm-thick glass-backed Silica Gel 60 TLC plates (EM Science), and lipids were eluted from the silica gel with CHCl3:MeOH (3:1, vol/vol). Lipids were separated using a PE:diethylether (9:1, vol/vol) solvent system. Unlabeled lipids were visualized by spraying them with 5% ethanolic phosphomolybdic acid, orcinol reagent, anisaldehyde, or naphthol sulfuric acid solution, followed by charring. TLC plates with radiolabeled lipids were exposed for 24 to 48 h to a phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics) and analyzed using a Storm 860 gel PhosphorImager system (Molecular Dynamics) and the companion software ImageQuant version 5.0 (Amersham Biosciences).

Atmospheric-pressure photoionization MS.

Mass spectral data were acquired at the Hunter College/CUNY MS facility on an Agilent Technologies 1100 series liquid chromatography/mass spectrometer device model G1946D using atmospheric-pressure photoionization (APPI) in positive and negative modes. Ionization was carried out with a drying gas flow of 5.0 liters min−1, a nebulizer pressure of 60 lb/in2, a drying gas temperature of 300°C, a vaporizer temperature of 450°C, and a capillary voltage of 4,000 V. The mass range scanned was between 200 and 1,600 atomic mass units (amu), with fragmentor voltages ranging from 60 V at 50 amu to 175 V at 1,800 amu. The samples were dissolved in hexane and CHCl3. Routinely, a 10-μl aliquot of the sample was combined with 10 μl of toluene (APPI dopant), and a 10-μl aliquot of the mixture was introduced into the mass spectrometer in a solution of MeOH:H2O (95:5, vol/vol) containing 0.1% acetic acid, 50 μM ammonium acetate, and 0.1% CHCl3 at a flow rate of 500 μl min−1. Data were processed using ChemStation software (Agilent Technologies).

Derivatization of M. ulcerans lipids.

Purified M. ulcerans DPs were dried in a vial at room temperature and subjected to standard chemistry to achieve hydroxyl group derivatization (12, 21). For acetylation, the lipid sample was resuspended in 100 μl of acetic anhydride:pyridine (9:1, vol/vol), and the mixture was incubated overnight at room temperature. Chloroacetylation was accomplished by the addition of 100 μl of pyridine and 50 mg of chloroacetic anhydride to the lipid sample and subsequent incubation of the mixture for 4 h at 0°C. For benzoylation, 100 μl of pyridine, 20 mg of benzoic anhydride, and a catalytic amount of 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine were added to the lipid sample, and the mixture was incubated overnight at room temperature. After incubation, 1 volume of water was added to each derivatization reaction mixture, and the aqueous solution was extracted twice with hexanes. The organic extract was washed with water and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the remaining lipid products were analyzed by MS.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the Mk2951c gene was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY906857.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Identification of phthiodiolone ketoreductase gene candidates in mycobacteria producing diacyl (p)PONE and diacyl (p)POL esters.

According to the current model for DP biosynthesis, (p)PONEs are assembled by the (Pks15/1)PpsA-E PK synthase system and subsequently modified to generate (p)POLs (15, 20, 24, 34) (Fig. 2). The (p)PONE-to-(p)POL conversion is thought to require two steps, although the timing of the two steps relative to glycol esterification remains unclear. The first step is reduction of the (p)PONE keto group via an unknown mechanism, presumably producing a (phenol)phthiotriol intermediate. The second step is hydroxyl group methylation and is thought to be catalyzed by an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase (18), which is encoded by the Rv2952 gene in M. tuberculosis (29).

In an effort to better understand DP biosynthesis, we investigated the genetic requirement for PONE-to-POL conversion with a focus on the keto group reduction. We undertook a comparative genomics approach to identify a phthiodiolone ketoreductase gene candidate. This was guided by the premise that all genes dedicated to DP production are likely located in a 70-kb gene cluster conserved in all DP producers analyzed to date (9, 10, 16). We explored the DP gene clusters in M. tuberculosis (strain H37Rv) (9), M. bovis (strain AF2122/97) (16), and M. leprae (strain TN) (10) for the presence of possible phthiodiolone ketoreductases. The analysis revealed a conserved gene encoding a putative oxidoreductase of unknown function and annotated as Rv2951c, Mb2975c, and ML0131 for M. tuberculosis (9), M. bovis (16), and M. leprae (10), respectively. We also probed the M. marinum genome for the conserved putative oxidoreductase. A query of the M. marinum genome with the M. tuberculosis the Rv2951c gene-predicted product (Rv2951c) revealed a homolog (Mm2951c) with 83% sequence identity encoded by a gene (the Mm2951c gene) located in the predicted DP gene cluster of M. marinum (not shown).

Sequence analysis indicated that the oxidoreductases have 81 to 100% sequence identity (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and revealed the presence of a domain characteristic of coenzyme F420-dependent N5,N10-methylene tetrahydromethanopterin reductase and related flavin-dependent oxidoreductases (CD identifier, COG2141) in each protein. This domain is found in a broad family of oxidoreductases that perform redox reactions, including carbonyl group reduction. The COG2141 domain has 336 residues, and ∼97% of its length aligned with each of the oxidoreductases (score values range, 131 to 147 bits; E value range, 8 × e−36 to 1 × e−31). Sequence analysis therefore suggests that Rv2951c and its homologs are the phthiodiolone ketoreductases.

Examination of the genomes of mycobacterial strains producing only diacyl (p)PONE esters for the presence of phthiodiolone ketoreductase candidates.

To support the proposed phthiodiolone ketoreductase function of Rv2951c and its homologs, we took advantage of naturally occurring DP-producing M. ulcerans and M. kansasii strains that synthesize only the diacyl PONE variants (3, 25). The mechanism underlying diacyl POL deficiency in these mycobacteria has so far remained obscure. This deficiency could be due to lack of either the ketoreductase or the methyltransferase activities required for (p)PONE-to-(p)POL conversion, except that lack of the latter activity would result in accumulation of (phenol)phthiotriol intermediates (29). Since accumulation of these intermediates has not been reported for diacyl (p)POL-deficient mycobacteria, we favored the idea that the deficiency results from lack of ketoreductase activity.

It is reasonable to postulate that if indeed the Rv2951c gene and its homologs encode phthiodiolone ketoreductases, then either the genes or gene products must be naturally disrupted, absent, or inactive in mycobacteria restricted to diacyl (p)PONE production. To investigate this hypothesis, we examined the genomes of M. ulcerans and M. kansasii for Rv2951c gene homologs. A query of the M. ulcerans genome revealed that the predicted phthiodiolone ketoreductase gene, the Mu2951c gene, has a G-to-A transition at codon 147 introducing a premature stop codon. Excluding this mutation, Mu2951c displays 80 to 98% sequence identity to the other predicted ketoreductases (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Sequence analysis indicated that Mu2951c has a possible COG2141 domain (score value, 144 bits; E value, 1 × e−35) and is encoded in the putative DP gene cluster of M. ulcerans (not shown).

Unlike the results with M. ulcerans, PCR-based identification of the M. kansasii phthiodiolone ketoreductase gene candidate (the Mk2951c gene) and its subsequent sequencing revealed no coding sequence disruption. Mk2951c has 80 to 86% sequence identity to the other predicted phthiodiolone ketoreductases (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) and a potential COG2141 domain (score value, 125 bits; E value, 8 × e−30). The Mk2951c sequence provided no information to account for the diacyl POL deficiency in M. kansasii; however, it is possible that the lack of ketoreductase activity occurs due to an inactivating mutation in the Mk2951c coding region or a mutation outside this region that compromises Mk2951c expression.

TLC analysis of DPs from M. ulcerans and M. kansasii strains expressing functional phthiodiolone ketoreductases.

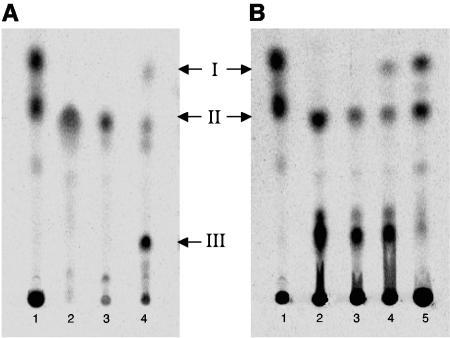

We investigated whether expression of a functional phthiodiolone ketoreductase would correct the diacyl POL deficiency of M. ulcerans and M. kansasii. Radio-TLC analysis of apolar lipid extracts from the control strains M. ulcerans/pMV261 and M. kansasii/pMV261 confirmed that the transformants had apolar lipid profiles essentially indistinguishable from those seen with wild-type strains (Fig. 3). A comparison of apolar lipids from M. ulcerans/pMV261 and M. kansasii/pMV261 with those of M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c and M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c revealed that transformants containing pCPMm2951c (expressing Mm2951c) produced a new lipid (lipid I) with an Rf nearly identical to that of diacyl POLs from M. tuberculosis (Fig. 3) (27).

FIG. 3.

TLC analysis of radiolabeled apolar lipids from M. ulcerans (A) and M. kansasii (B) strains. Lanes 1, reference lipid profile of M. tuberculosis showing the spots corresponding to diacyl POLs (higher Rfs) and diacyl PONEs (lower Rfs) (27). Lanes 2, lipid profiles of M. ulcerans and M. kansasii wild-type strains. Lanes 3, lipid profiles of M. ulcerans/pMV261 and M. kansasii/pMV261. Lanes 4, lipid profiles of M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c and M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c. Lane 5, lipid profile of M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c. Spot I and spot II correspond to the diacyl POL and diacyl PONE variants, respectively, based on the reference profile of M. tuberculosis and MS analysis. Spot III corresponds to the suspected diacyl phthiotriol intermediate, an assignment confirmed by MS analysis.

Surprisingly, the radio-TLC analysis revealed yet another new component (lipid III) in the lipid profile of M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c. Lipid III migrated with a lower Rf than that of the native diacyl PONEs (lipid II) and was not detected in M. ulcerans/pMV261 (Fig. 3). The low Rf of lipid III is consistent with the expected migration of the more-polar diacyl phthiotriol intermediate. The accumulation of this lipid in M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c is unexpected and may suggest that the methyltransferase activity of M. ulcerans is not as robust as that of M. tuberculosis, which does not accumulate the intermediate (Fig. 3). Lipids with Rf values similar to those of the suspected diacyl phthiotriol intermediate were also present in the lipid profiles of all M. kansasii strains (Fig. 3). These spots probably arise from M. kansasii-specific apolar lipids in the crude extracts rather than from diacyl phthiotriol accumulation.

Although analysis of the sequenced Mk2951c fragment provided no reasons to suspect that the gene product is inactive, the complementation studies demonstrated that M. kansasii lacks a functional phthiodiolone ketoreductase. We analyzed the DP profile of M. kansasii transformed with pCPMmMk2951c to investigate whether the Mk2951c gene fragment has naturally occurring mutations that render the enzyme inactive. This plasmid is essentially the same as pCPMm2951c, except for the replacement of the Mm2951c coding sequence downstream of the second codon with the one from Mk2951c. Radio-TLC analysis of M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c apolar lipids revealed that, like Mm2951c, MmMk2951c complemented the diacyl POL deficiency of M. kansasii, indicating that the translational product of the Mk2951c gene fragment is functional. Thus, the lack of phthiodiolone ketoreductase activity in M. kansasii is anticipated to arise from mutations outside this fragment, possibly in the ribosome-binding site or promoter/regulatory regions.

MS analysis of DPs from M. ulcerans and M. kansasii strains expressing functional phthiodiolone ketoreductases.

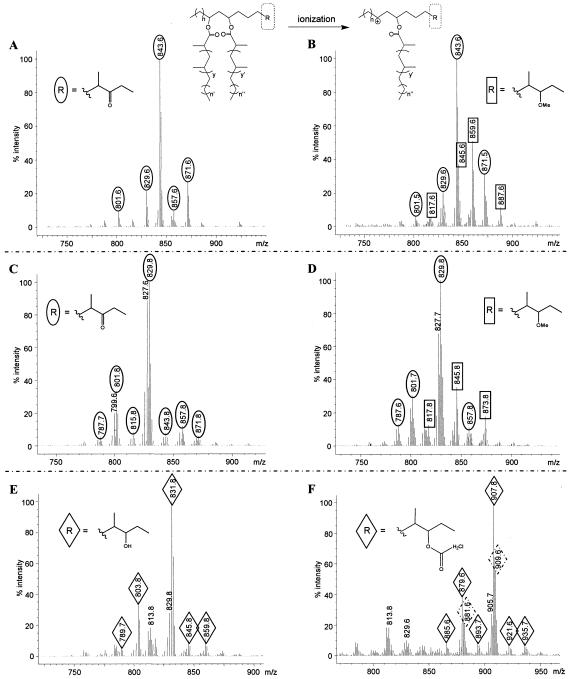

DPs of M. kansasii and M. ulcerans transformants were analyzed by MS to confirm the production of diacyl POLs in M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c, M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c, and M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c. DPs from M. kansasii/pMV261 and M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c were purified by flash column chromatography and analyzed by APPI MS. The mass spectra of both lipid fractions showed the expected peak distribution pattern of the monoacyl PONE ion series (3, 24), with the major peak at m/z 843.6 (Fig. 4A and B) likely corresponding to an ester of C26 PONE and C32 mycocerosic acid. The peaks in this series differ by multiples of 14 amu, a variation arising from the characteristic heterogeneity in the number of methyl branches and length of acyl chains found in DPs. Most importantly, a second peak series not present in the mass spectra of M. kansasii/pMV261 lipids and centered on m/z 859.6 was seen in the spectra of M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c lipids (Fig. 4A and 4B). The m/z value of each ion in this series is 16 amu larger than that of its native monoacyl PONE ion (a mass gain resulting from methylation of the 3-keto group), indicating that this series corresponds to the monoacyl POL ions. MS analysis of M. kansasii/pCPMmMk2951c DPs demonstrated the presence of the expected peaks for both the monoacyl POL and the monoacyl PONE ion series in this strain as well (not shown). Overall, the MS analysis confirmed that the introduction of Mm2951c or MmMk2951c into M. kansasii imparts the capacity to produce diacyl POLs.

FIG. 4.

APPI-MS analysis of DPs from M. kansasii and M. ulcerans strains. The top scheme shows the ionization of DPs to the corresponding carbocations arising from the loss of either acyl chain and resulting in the peaks in the mass spectra. The presented mass spectra correspond to (A) an M. kansasii/pMV261 lipid II sample showing the monoacyl PONE ion series (ovals); (B) an M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c lipid I plus II sample showing both the monoacyl PONE and the monoacyl POL ion series (rectangles); (C) an M. ulcerans/pMV261 lipid II sample showing the monoacyl PONE ion series; (D) an M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c lipid I plus II sample showing both the monoacyl PONE and the monoacyl POL ion series; (E) an M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c lipid III sample showing a peak distribution consistent with the monoacyl phthiotriol ion series (diamonds) derived from the diacyl phthiotriol intermediates; and (F) an M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c lipid III sample after chloroacetylation showing m/z 907.8 and 909.6 peaks corresponding to the m/z 831.8 peak in the spectrum of the nonderivatized lipid III sample with the expected +76- and +78-amu shifts arising from chloroacetylation. The 37Cl isotope peaks of the chloroacetylated lipids are marked with diamonds with broken lines. The n, n′, n′′, y, and y′ values are as shown in the Fig. 1 legend.

MS analysis also established that Mm2951c rescued diacyl POL production in M. ulcerans. The M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c diacyl POLs and diacyl PONEs (Fig. 3A, lane 4, lipids I and II) were isolated using flash column chromatography followed by preparative TLC purification. The diacyl PONEs of M. ulcerans/pMV261 (Fig. 3A, lane 3, lipid II) were purified using the same methodology. The M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c and M. ulcerans/pMV261 lipid fractions were analyzed by APPI MS. As expected, the mass spectrum of the lipid from M. ulcerans/pMV261 showed only the monoacyl PONE ion series (Fig. 4C). The most prominent peak in the series had an m/z value of 829.8, likely arising from an ester of C25 PONE and a C32 acyl chain. The spectrum of the M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c lipid fraction containing lipids I and II displayed not only the expected monoacyl PONE peak series but also an additional series with a major peak at m/z 845.8 (Fig. 4D). As seen in the mass spectrum of the M. kansasii/pCPMm2951c lipids, the m/z value of each peak in this series is 16 amu larger than that of its native monoacyl PONE ion (Fig. 4D). The masses in this peak series correspond to the masses expected for the monoacyl POL ion series.

Interestingly, the mass spectra obtained for lipids of both M. ulcerans/pMV261 and M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c displayed an unexpectedly prominent peak at m/z 827.6 to 827.7 (Fig. 4C and D). This m/z value is 2 amu smaller than the m/z value of the major diacyl PONE peak (m/z 829.8). It is tempting to speculate that this peak arises from a DP variant with one additional degree of unsaturation. However, double-bond-containing DP variants have not been reported, and further structural analysis would be needed to investigate this possibility.

MS analysis of the suspected diacyl phthiotriol intermediate produced by M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c.

Radio-TLC analysis suggested the accumulation of diacyl phthiotriols in M. ulcerans/pCPMm2951c. The suspected diacyl phthiotriols (Fig. 3A, lipid III) were isolated by flash column chromatography followed by preparative TLC purification and subjected to MS analysis. The mass spectrum of lipid III showed an ion series with a major peak at m/z 831.8 and corresponding secondary peaks with the distinctive 14-amu variation patterns of DPs (Fig. 4E). m/z 831.8 is 2 amu larger than that of the predominant monoacyl PONE ion (m/z 829.8) (Fig. 4C) and consistent with the reduction of the keto group, resulting in the monoacyl phthiotriol ion. However, this value also falls within the monoacyl POL ion series (Fig. 4D), making an unequivocal identity assignment impossible.

To differentiate between these two peak assignment possibilities, we derivatized the suspected diacyl phthiotriols to achieve hydroxyl group chloroacetylation, acetylation, or benzoylation and analyzed the reaction products by MS. Chloroacetylation, acetylation, and benzoylation are expected to introduce shifts of +76 and +78 (due to the abundance of 35Cl and 37Cl), +42, and +104 amu, respectively, in the m/z value of every peak in the monoacyl phthiotriol ion series. MS analysis of the suspected diacyl phthiotriols after chloroacetylation showed a new ion series with the main peak at m/z 907.8. This m/z value corresponds to the m/z 831.8 ion in the spectrum of the nonderivatized lipid sample with a shift of +76 amu predicted to arise from chloroacetylation. Incorporation of the chloroacetyl is verified by the presence of the +78 amu 37Cl isotope peak at m/z 909.6. MS analysis of the suspected diacyl phthiotriol after acetylation or benzoylation exhibited the expected amu shifts as well (not shown). As anticipated, comparison of the mass spectra of M. ulcerans-purified lipids I and II (Fig. 3A) subjected to each of the derivatization reactions and the corresponding nonderivatized control revealed no appreciable mass changes (not shown). Thus, the chemical derivatization analysis confirmed the presence of a free hydroxyl group in the suspected diacyl phthiotriols and proves the identity of this lipid.

In conclusion, this study advances our understanding of mycobacterial PK virulence factor biosynthesis by (i) identifying the enzyme that catalyzes the PONE keto group reduction during diacyl POL biosynthesis and, most likely, the reduction of the keto group in pPONEs during diacyl pPOL biosynthesis as well; (ii) validating the existence of the diacyl phthiotriol intermediate in diacyl POL biosynthesis; and (iii) demonstrating that lack of phthiodiolone ketoreductase activity is responsible for diacyl POL deficiency in M. ulcerans and M. kansasii. Finally, while the analysis was done with M. ulcerans, M. kansasii, and M. marinum, the results can be extended to M. tuberculosis and M. leprae, where the proposed phthiodiolone ketoreductases are expected to be required for diacyl (p)POL production.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Stavros S. Niarchos Foundation, the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, NIH MSTP training grant GM07739, the NIH National Research Service Award 1 F31 AI054326-01 to K.C.O., and a NYC Council Speaker's Fund for Biomedical Research to L.E.N.Q.

We thank Albert M. Morrishow (Weill Medical BioPolymer MS Core Facility) for his help with MS analysis and Ulf Peters (Rockefeller University) for helpful discussions of lipid derivatization experiments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azad, A. K., T. D. Sirakova, L. M. Rogers, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1996. Targeted replacement of the mycocerosic acid synthase gene in Mycobacterium bovis BCG produces a mutant that lacks mycosides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:4787-4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azad, A. K., T. D. Sirakova, N. D. Fernandes, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1997. Gene knockout reveals a novel gene cluster for the synthesis of a class of cell wall lipids unique to pathogenic mycobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16741-16745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Besra, G. S., D. E. Minnikin, A. Sharif, and J. L. Stanford. 1990. Characteristic new members of the phthiocerol and phenolphthiocerol families from Mycobacterium ulcerans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 54:11-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan, P. J. 2003. Structure, function, and biogenesis of the cell wall of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinburgh) 83:91-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buglino, J., K. C. Onwueme, J. A. Ferreras, L. E. Quadri, and C. D. Lima. 2004. Crystal structure of PapA5, a phthiocerol dimycocerosyl transferase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:30634-30642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camacho, L. R., D. Ensergueix, E. Perez, B. Gicquel, and C. Guilhot. 1999. Identification of a virulence gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 34:257-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee, D. 1997. The mycobacterial cell wall: structure, biosynthesis and sites of drug action. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1:579-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chua, J., I. Vergne, S. Master, and V. Deretic. 2004. A tale of two lipids: Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole, S. T., K. Eiglmeier, J. Parkhill, K. D. James, N. R. Thomson, P. R. Wheeler, N. Honore, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, K. Mungall, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. M. Davies, K. Devlin, S. Duthoy, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, C. Lacroix, J. Maclean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, K. M. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, S. Simon, M. Simmonds, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, J. R. Woodward, and B. G. Barrell. 2001. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409:1007-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Constant, P., E. Perez, W. Malaga, M. A. Laneelle, O. Saurel, M. Daffe, and C. Guilhot. 2002. Role of the pks15/1 gene in the biosynthesis of phenolglycolipids in the M. tuberculosis complex: evidence that all strains synthesize glycosylated p-hydroxybenzoic methyl esters and that strains devoid of phenolglycolipids harbor a frameshift mutation in the pks15/1 gene. J. Biol. Chem. 277:38148-38158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook, A. F., and D. T. Maichuk. 1970. Use of chloroacetic anhydride for the protection of nucleoside hydroxyl groups. J. Org. Chem. 35:1940-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cox, J. S., B. Chen, M. McNeil, and W. R. Jacobs. 1999. Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature 402:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daffe, M., and M. A. Laneelle. 1988. Distribution of phthiocerol diester, phenolic mycosides and related compounds in mycobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 134:2049-2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daffe, M., and P. Draper. 1998. The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39:131-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garnier, T., K. Eiglmeier, J. C. Camus, N. Medina, H. Mansoor, M. Pryor, S. Duthoy, S. Grondin, C. Lacroix, C. Monsempe, S. Simon, B. Harris, R. Atkin, J. Doggett, R. Mayes, L. Keating, P. R. Wheeler, J. Parkhill, B. G. Barrell, S. T. Cole, S. V. Gordon, and R. G. Hewinson. 2003. The complete genome sequence of Mycobacterium bovis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:7877-7882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gastambide-Odier, M., J.-M. Delaumény, and E. Lederer. 1963. Biosynthesis of C32-mycocerosic acid; incorporation of propionic acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 70:670-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gastambide-Odier, M., J.-M. Delaumény, and E. Lederer. 1963. Synthesis of phthiocerol. Incorporation of methionine and propionic acid. Chem. Ind. 31:1285-1286. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gastambide-Odier, M., P. Sarda, and E. Lederer. 1967. Biosynthesis of the aglycons of mycosides A and B. Bull. Soc. Chim. Biol. 49:849-864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goren, M. B., and P. J. Brennan. 1979. Mycobacterial lipids: chemistry and biologic activities, p. 63-193. In G. P. Youmans (ed.), Tuberculosis. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, Pa.439567

- 21.Kaluza, Z., and D. Mostowicz. 2003. Synthesis of enantiopure 1,2-dihydroxyhexahydropyrroloisoquinolines as potential tools for asymmetric catalysis. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 14:225-232. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karakousis, P. C., W. R. Bishai, and S. E. Dorman. 2004. Mycobacterium tuberculosis cell envelope lipids and the host immune response. Cell. Microbiol. 6:105-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathur, M., and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1992. Molecular cloning and sequencing of the gene for mycocerosic acid synthase, a novel fatty acid elongating multifunctional enzyme, from Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin. J. Biol. Chem. 267:19388-19395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minnikin, D. E., L. Kremer, L. G. Dover, and G. S. Besra. 2002. The methyl-branched fortifications of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 9:545-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minnikin, D. E., G. Dobson, M. Goodfellow, M. Magnusson, and M. Ridell. 1985. Distribution of some mycobacterial waxes based on the phthiocerol family. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:1375-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng, V., G. Zanazzi, R. Timpl, J. F. Talts, J. L. Salzer, P. J. Brennan, and A. Rambukkana. 2000. Role of the cell wall phenolic glycolipid-1 in the peripheral nerve predilection of Mycobacterium leprae. Cell 103:511-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Onwueme, K. C., J. A. Ferreras, J. Buglino, C. D. Lima, and L. E. Quadri. 2004. Mycobacterial polyketide-associated proteins are acyltransferases: proof of principle with Mycobacterium tuberculosis PapA5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:4608-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parish, T., and N. G. Stoker (ed.). 2001. Methods in molecular medicine, vol. 54. Mycobacterium tuberculosis protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J.

- 29.Perez, E., P. Constant, F. Laval, A. Lemassu, M. A. Laneelle, M. Daffe, and C. Guilhot. 2004. Molecular dissection of the role of two methyltransferases in the biosynthesis of phenolglycolipids and phthiocerol dimycocerosate in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J. Biol. Chem. 279:42584-42592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rainwater, D. L., and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1985. Fatty acid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin. Purification and characterization of a novel fatty acid synthase, mycocerosic acid synthase, which elongates n-fatty acyl-CoA with methylmalonyl-CoA. J. Biol. Chem. 260:616-623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rambukkana, A., G. Zanazzi, N. Tapinos, and J. L. Salzer. 2002. Contact-dependent demyelination by Mycobacterium leprae in the absence of immune cells. Science 296:927-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reed, M. B., P. Domenech, C. Manca, H. Su, A. K. Barczak, B. N. Kreiswirth, G. Kaplan, and C. E. Barry III. 2004. A glycolipid of hypervirulent tuberculosis strains that inhibits the innate immune response. Nature 431:84-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rousseau, C., T. D. Sirakova, V. S. Dubey, Y. Bordat, P. E. Kolattukudy, B. Gicquel, and M. Jackson. 2003. Virulence attenuation of two Mas-like polyketide synthase mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 149:1837-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rousseau, C., N. Winter, E. Pivert, Y. Bordat, O. Neyrolles, P. Ave, M. Huerre, B. Gicquel, and M. Jackson. 2004. Production of phthiocerol dimycocerosates protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the cidal activity of reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by macrophages and modulates the early immune response to infection. Cell. Microbiol. 6:277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 36.Sirakova, T. D., V. S. Dubey, H.-J. Kim, M. H. Cynamon, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 2003. The largest open reading frame (pks12) in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis genome is involved in pathogenesis and dimycocerosyl phthiocerol synthesis. Infect. Immun. 71:3794-3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirakova, T. D., V. S. Dubey, M. H. Cynamon, and P. E. Kolattukudy. 2003. Attenuation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by disruption of a mas-like gene or a chalcone synthase-like gene, which causes deficiency in dimycocerosyl phthiocerol synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 185:2999-3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slayden, R., and C. E. Barry III. 2001. Analysis of the lipids of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Mol. Med. 54:229-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stendal, N. 1934. The presence of a glycol in the wax of tubercle bacilli. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. Ser. D 198:1549-1550. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stodola, F. H., and R. J. Anderson. 1936. The chemistry of the lipids of tubercle bacilli. XLVI. Phthiocerol, a new alcohol from the wax of the human tubercle bacillus. J. Biol. Chem. 114:467-472. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stover, C. K., V. F. de la Cruz, T. R. Fuerst, J. E. Burlein, L. A. Benson, L. T. Bennett, G. P. Bansal, J. F. Young, M. H. Lee, G. F. Hatfull, et al. 1991. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature 351:456-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trivedi, O. A., P. Arora, A. Vats, M. Z. Ansari, R. Tickoo, V. Sridharan, D. Mohanty, and R. S. Gokhale. 2005. Dissecting the mechanism and assembly of a complex virulence mycobacterial lipid. Mol. Cell. 17:631-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.