Abstract

Sulfolobus acidocaldarius is an aerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon which grows optimally at 80°C and pH 2 in terrestrial solfataric springs. Here, we describe the genome sequence of strain DSM639, which has been used for many seminal studies on archaeal and crenarchaeal biology. The circular genome carries 2,225,959 bp (37% G+C) with 2,292 predicted protein-encoding genes. Many of the smaller genes were identified for the first time on the basis of comparison of three Sulfolobus genome sequences. Of the protein-coding genes, 305 are exclusive to S. acidocaldarius and 866 are specific to the Sulfolobus genus. Moreover, 82 genes for untranslated RNAs were identified and annotated. Owing to the probable absence of active autonomous and nonautonomous mobile elements, the genome stability and organization of S. acidocaldarius differ radically from those of Sulfolobus solfataricus and Sulfolobus tokodaii. The S. acidocaldarius genome contains an integrated, and probably encaptured, pARN-type conjugative plasmid which may facilitate intercellular chromosomal gene exchange in S. acidocaldarius. Moreover, it contains genes for a characteristic restriction modification system, a UV damage excision repair system, thermopsin, and an aromatic ring dioxygenase, all of which are absent from genomes of other Sulfolobus species. However, it lacks genes for some of their sugar transporters, consistent with it growing on a more limited range of carbon sources. These results, together with the many newly identified protein-coding genes for Sulfolobus, are incorporated into a public Sulfolobus database which can be accessed at http://dac.molbio.ku.dk/dbs/Sulfolobus.

Sulfolobus acidocaldarius strain DSM639, the type strain of the archaeal genus Sulfolobus, was the first hyperthermoacidophile to be characterized from terrestrial solfataras by Brock et al. (12). It grows optimally at 75 to 80°C and pH 2 to 3, under strictly aerobic conditions, on complex organic substrates, including yeast extract, tryptone, and Casamino Acids and a limited number of sugars.

Many of the seminal studies on archaea and crenarchaea were performed on S. acidocaldarius. Thus, S. acidocaldarius was employed to demonstrate the similarity of the archaeal and eukaryal transcription apparatuses (6, 36, 46). Moreover, its sensitivity to a wide range of ribosomal antibiotics (1) and ease of transformation (3) have rendered S. acidocaldarius a focus for in vivo genetic studies. Proteins responsible for chromatin folding (Sac7c) and the highly abundant Sac10b (Alba) protein, implicated in the regulation of chromatin and/or cellular RNAs in Sulfolobus (7, 30), were first characterized for this organism (29).

S. acidocaldarius has also been used for studying genetic fidelity at high temperatures and is the only hyperthermophilic archaeon for which the rate and type of spontaneous mutation have been quantified in vivo (26). Its relatively low mutation rate, despite its high-temperature environment, has stimulated a strong interest in its efficient repair systems. It also carries a restriction modification system involving the endonuclease SuaI and exocyclic N-4 methyl cytidine at the target site, which, in contrast to 5 methyl cytidine, is less damaging for DNA structure on deamination at high temperature (27, 45).

Special features include its ability to exchange chromosomal genes intercellularly (2, 25) and its capacity to grow synchronously in culture which has facilitated archaeal cell cycle studies (9, 10). In contrast to S. solfataricus P2 (51) and Sulfolobus tokodaii (33), which both possess extensive networks of autonomous and nonautonomous mobile elements (13, 15), S. acidocaldarius maintains a very stable genome organization. This, together with the construction of transcriptome microarrays based on the present genome sequence (39), will provide a solid basis for comprehensive studies of the cellular and systems biology of Sulfolobus.

Determination of the genome sequence of S. acidocaldarius and comparative studies with the genomes of S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii, enabled us to generate an integrated and comprehensive public database for the Sulfolobus genomes which will serve as a important research resource for (i) further defining the phylogenetic status of the crenarchaeal kingdom of the Archaea; (ii) molecular, genetic, and cell-cycle studies of Sulfolobus; and (iii) studying less complex archaeal systems in order to understand the corresponding, and more complex, systems in eukaryotes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genome sequencing and assembly.

The genome of S. acidocaldarius strain DSM639 was cloned and mapped using a shotgun strategy with plasmid pUC18 and bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) libraries (53). Sequencing was performed using a Biorobot 8000 (QIAGEN, Westburg, Germany) and MegaBACE 1000 Sequenators (Amersham Biotech, Amersham, United Kingdom). Sequence reads averaged 650 bp. For gap closure and sequence editing, 1,113 custom primer-walking reactions were performed on the plasmid and BAC clones. Several sequence regions were also checked by generating and sequencing PCR fragments. The genome was assembled using the phred-phrap-consed software package (21).

Gene identification, functional annotation, and genomic comparisons.

Protein coding genes were identified with the bacterial and archaeal gene finder EasyGene (37), and tRNA genes were located using tRNAscan-SE (38). All short open reading frames (ORFs; <120 amino acids) yielding no sequence matches in GenBank were aligned against short ORFs identified with EasyGene in the other Sulfolobus genomes. ORFs with homologs in at least two genomes were inferred to encode a gene and were included in the final annotation. Frameshifts were detected and checked by sequencing after a second round of manual annotation. All remaining frameshifts were considered to be authentic. All annotations were checked individually a third time by an independent annotator.

Functional assignments are based on data collected from searches against SWISS-PROT (11), GenBank (8), COG (56), and the Pfam databases (5). Transmembrane helices were predicted with TMHMM (34) and signal peptides with SignalP (42). All the data for the S. acidocaldarius genome were stored, analyzed, and compared with the other Sulfolobus genomes in the MUTAGEN annotation system (14).

Phylogenetic assignments of genes (as in Table 1) were obtained by searching gene sequences against the GenBank/EMBL sequence database with low-complexity filtering and an e-value cutoff of 0.01. Database matches were considered significant if they covered >70% of the protein with >55% positive hits and if the two protein lengths deviated by <30%. The origin of the gene was then assigned according to the first bifurcation point in a phylogenetic tree generated from the positive matches obtained (K. Brügger, unpublished).

TABLE 1.

Specificity of protein-coding genes of the S. acidocaldarius genomea

| Gene specificity | Total no. of S. acidocaldarius genes | Total no. of genes absent from S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii |

|---|---|---|

| S. acidocaldarius exclusive | 305 | 305 |

| Sulfolobus specific | 866 | 0 |

| Crenarchaea specific | 107 | 4 |

| Archaea specific | 352 | 58 |

| Archaea + bacteria specific | 327 | 24 |

| Archaea + eukarya specific | 64 | 2 |

| Universal | 271 | 7 |

| Total | 2,292 | 400 |

The criteria used for assigning genes to different genera, kingdoms, or domains are described in Materials and Methods.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The annotated genome sequence has been deposited in the GenBank/EMBL sequence database under accession no. CP000077.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

General genome features.

The genome of S. acidocaldarius constitutes a 2,225,959-bp circular chromosome with a G+C content of 36.7%. The final genome sequence was assembled from a total of 19,761 sequence reads, yielding a 5.8-fold sequence coverage. The genome numbering starts 100 bp upstream from the cdc6-3 gene. A total of 2,292 protein-coding genes were predicted, including many shorter genes (coding for <120 aa) which were identified, or verified, for the first time using a comparative sequence approach with the other Sulfolobus genomes (33, 51). The total numbers of genome-specific genes and of shared homologs (the criteria used are described in Materials and Methods) are presented for the three Sulfolobus genomes in the overlapping circle plot in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Conservation of protein genes. The overlapping circle plot shows the number of genes shared between two or three Sulfolobus genomes. Blue, red, and green numbers represent genes shared with S. acidocaldarius, S. solfataricus, and S. tokodaii, respectively. The black number in the center denotes the total number of different genes in the three genomes.

Of the 2,292 protein-coding genes identified for S. acidocaldarius, over 50% were either exclusive to S. acidocaldarius (305 genes) or specific to Sulfolobus (866 genes) (Table 1). Lower percentages were identified as crenarchaeon specific, archaeon specific, archaeon plus bacterium specific, archaeon plus eukaryote specific, or universal (Table 1).

About 58% of the total number of genes in all three Sulfolobus genomes are shared between the three organisms (Fig. 1), and they encode a core set of proteins which can be classified into 1,391 gene families or functional groups. The largest gene families encode proteins involved in transport. In contrast, the largest family of genes which are exclusive to S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii encode transposases (see below).

Previously unrecognized genes were identified by comparing all ORFs detected in the S. acidocaldarius genome by EasyGene with the GenBank genome files for S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii as described in Materials and Methods. This revealed 133 short genes in total (Table 2), of which 95 were different genes, all with previously unrecognized homologs in S. solfataricus and/or S. tokodaii. The length distribution of these genes is shown in Table 2, and the ratio of newly identified to known genes gradually decreases with increasing gene size over the range 50 to 100 bp (Table 2). No inteins were detected in S. acidocaldarius.

TABLE 2.

Newly identified short genes in the S. acidocaldarius genomea

| Amino acid size range | No. of genes:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Newly identified | Known | |

| 30-39 | 5 | 0 |

| 40-49 | 7 | 3 |

| 50-59 | 21 | 20 |

| 60-69 | 24 | 30 |

| 70-79 | 29 | 37 |

| 80-89 | 20 | 42 |

| 90-99 | 17 | 52 |

| 100-109 | 5 | 75 |

| 110-119 | 5 | 52 |

| Total | 133 | 311 |

The short genes were identified by sequence comparison with the other Sulfolobus genomes. Some of the 133 newly identified genes exist in multiple copies, so the total number of different genes is 95 (see text). The numbers of known genes in the S. acidocaldarius genome, in the same size ranges, are included for comparison.

Short untranslated RNAs.

Many smaller untranslated RNAs have been isolated from archaea, first from S. acidocaldarius (43) and more recently from Archaeoglobus fulgidus and S. solfataricus (54, 55). For S. acidocaldarius, 18 of the 29 RNAs identified (excluding tRNAs, rRNAs, and 7S RNA) belong to the C/D box snoRNAs which guide base methylation in rRNAs, tRNAs, and other unidentified targets. All of these RNA genes were successfully mapped in the genome for S. acidocaldarius and are included in the Sulfolobus database. Most of these could not be detected in the other Sulfolobus genomes by BLAST searches because of low sequence conservation, and therefore, only RNAs detected experimentally for S. solfataricus (55) are included in the database.

Lack of active mobile elements.

No copies of active IS elements or miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements were detected in marked contrast to the other Sulfolobus genomes (13, 15, 47). Four potentially full-length IS elements were identified, two of which occur in an integrated element, SA3 (Saci0487 and -0504). However, each exists in a single copy in the genome and is, therefore, unlikely to be active given that transposition events observed to date in Sulfolobus species are mobilized by a “copy and paste” mechanism (P. Redder, unpublished). Moreover, only five fragmented IS elements were detected, one of which (Saci1941) partitions a proline iminopeptidase gene, providing evidence for an earlier transposition event. This fragment is almost identical in sequence to the transposase gene of a single IS element which encodes both a transposase and a resolvase (Saci2022 and 2023). We conclude that the genome has undergone few, if any, major rearrangements due to mobile elements, in contrast to the genomes of S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii, which are both extensively shuffled (15).

Integrated elements and intercellular gene exchange.

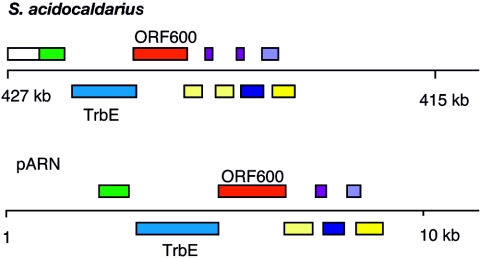

There are four chromosomally integrated elements, SA1 to SA4 carrying direct terminal repeats, some of which share larger (>100 bp) internal sequences, and their genomic positions are indicated in Fig. 2. They range in size from 5.6 to 8.7 kb, for the three smaller ones, to 32.5 kb for the larger one, SA3, and each exhibits a higher G+C content (39 to 42%) than the genome (52). They all encode integrases, three of which are of the archaeal partitioning type (52). SA3 resembles a self-transmissible plasmid of the pARN type (20, 23), and it has retained most of the conserved plasmid region which carries genes implicated in plasmid conjugation (Fig. 3). These genes encode a TrbE-like protein which, although interrupted by a +1 frameshift, may still be functional due to a “slippery” sequence of 8 A's, and ORF600 which carries multiple transmembrane helical motifs (Fig. 3) (23). Only the putative origin of replication and genes implicated in plasmid replication are absent, possibly as a result of rearrangements occurring at the Sulfolobus-specific recombination motif, TAAACTGGGGAGTTTA, multiple copies of which are present in both the pARN plasmids and SA3 (23). This element could facilitate the intercellular exchange of chromosomal DNA that is a special characteristic of S. acidocaldarius (2, 25).

FIG. 2.

Origins of replication and other major structural features of the S. acidocaldarius genome. Replication origins were predicted using the Z-curve method (64), where only the Y component, calculated for each nucleotide, is plotted. Arrows indicate putative replication origins which are consistent with those predicted experimentally from marker frequency analyses (39). On the genome map, the following are indicated: three cdc6 genes, integrated elements SA1 to SA4, large rRNA genes, and SRSR clusters. The two different classes of repeat sequences (A,B and C,D) which are present in the four SRSR clusters are shown.

FIG. 3.

Gene map of the region of the integrated element SA3 which resembles a pARN self-transmissible plasmid. The chromosomal region is aligned with the corresponding region of a pARN plasmid (23). Genes with identical colors are homologs. All proteins in this region have been implicated in the archaeal conjugative apparatus. They include the partial homolog of TrbE and ORF600 (23).

SA4 encodes a homolog of a bacterial resolvase/recombinase (Saci0634) encoded by, for example, pathogenicity islands of Escherichia coli O157:H7 EDL933. Apart from S. acidocaldarius, only four other archaeal genomes, all from euryarchaea, encode such a resolvase, although the latter show more sequence similarity to their bacterial counterparts than to the Sulfolobus enzyme.

Metabolism.

Most genes encoding enzymes of the predicted central metabolic pathways are present, including those required for synthesizing purines and pyrimidines (57) and all amino acids, except selenocysteine. Exceptionally, a putative folate synthesis enzyme is encoded (Saci1101) which is normally absent from archaea (62).

S. acidocaldarius differs from known Sulfolobus species in that it grows on a more limited range of carbon sources, which include d-fucose, d-glucose, sucrose, maltotriose, dextrin, and starch, and it can also grow on a wide range of amino acids (24). Genes required for glucose metabolism are present for both the nonphosphorylated Entner-Doudoroff pathway and the partially overlapping alternative pathway which generates ATP (50). Lack of growth on metabolites such as ribose and fructose may reflect a lack of transporters for these sugars. A search of the genomes for Pfam transporter families PF00005, PF00083, and PF00528 yielded only 41 genes for S. acidocaldarius, compared with 75 for S. solfataricus and 52 for S. tokodaii. This is consistent with our not finding at least five specific sugar transporters in the S. acidocaldarius genome which are present in S. solfataricus: (i) arabinose/fructose/xylose, (ii) galactose/glucose/mannose, (iii) cellobiose and higher derivatives, (iv) maltose/maltodextrin, and (v) trehalose (18), and only two, the third and fourth, were found in S. tokodaii. However, other proteins must be responsible for sugar transport, since S. acidocaldarius can grow on both d-glucose and dextrin, as well as other sugars (24), consistent, for example, with its encoding an α-amylase (Saci1200).

There are at least three enzymes encoded in S. acidocaldarius which potentially enable it to grow on specialized carbon sources: (i) a homolog of the bacterial enzyme (Saci2213) which degrades poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates), an energy storage polylipid; (ii) a special transporter for malate and other C4-dicarboxylates (Saci1755) which are shared with some euryarchaea but not with other Sulfolobus species; and (iii) the two subunits of an aromatic ring dioxygenase (Saci2059, 2060) which degrades di- and monoaromatic ring compounds and is found only in S. acidocaldarius among the archaea.

All three Sulfolobus genomes encode the enzymes for metabolizing sulfur which yield sulfuric acid from hydrogen sulfide via a conserved sulfur locus (Saci2201, -2202, -2203), but only S. tokodaii encodes a sulfur oxygenase and can oxidize So.

DNA replication from multiple initiation sites.

All components of the DNA replication machinery which are known to be encoded in the other crenarchaeal genomes are also present in S. acidocaldarius (reviewed in reference 22). The finding of three cdc6 genes widely spaced in each of the first two Sulfolobus genomes was suggestive of multiple origins of replication (33, 51), as were Z-curve analyses which localized three possible origins in the S. solfataricus genome (64). However, the first experimental evidence, using two-dimensional gel analyses, identified two replication origins in S. solfataricus, neighboring cdc6-1 and cdc6-3 genes. The former was characterized in its noncoding upstream region by origin recognition boxes (ORB1, ORB2 and ORB3) and the latter by binding sites for Cdc6-2 and Cdc6-3 (C2a, C2b, C3a, and C3b) as well as shorter versions of the ORBs, mORBa and mORBb (Fig. 4) (48). The genome of S. acidocaldarius exhibits sequence motifs, and gene contexts, similar to those of S. solfataricus adjacent to the cdc6-1 and cdc6-3 genes (Fig. 4A and B). Marker frequency measurements, using whole-genome microarrays based on the S. solfataricus genome and on a preliminary version of this S. acidocaldarius sequence, have extended this knowledge by providing evidence for three origins in both organisms (39). Moreover, all the experimentally supported origins correspond approximately in position to those predicted by our Z-curve analysis (64) (Fig. 2), which indicates that cdc6-2 is not associated with an origin and is consistent with Cdc6-2 being assigned a role as a negative regulator of replication initiation at the cdc6-1 and cdc6-3 sites (48). The putative third replication origin has not yet been localized at the DNA sequence level.

FIG. 4.

Putative Cdc6 binding sites in S. acidocaldarius. (A) The three ORB sequences in S. acidocaldarius (S.a. ORB1 to -3) compared to the consensus ORB sequences in S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii (S.s. and S.t. ORB) (48), where dots indicate nonconserved bases. The genome map shows the position of the sequences relative to cdc6-1. (B) S. acidocaldarius sequences which are similar to Cdc6-2 and Cdc6-3 binding sites (48). The genome map indicates the positions of the sequences relative to cdc6-3.

DNA repair.

DNA of hyperthermophiles is particularly susceptible to deamination and depurination reactions, estimated at up to 1,000-fold higher than for mesophiles (49), and it requires rapid and effective DNA repair systems. This is consistent with the S. acidocaldarius genome encoding different repair systems, of both bacterial and archaeal/eukaryal types, most of which occur in some other archaea. They include direct removal of DNA damage, base excision repair, nucleotide excision repair (NER), and homolog-dependent double-strand-break repair (28, 61). However, in addition to the NER pathway, S. acidocaldarius seems to carry an apparatus for UV damage excision repair since it encodes a UV damage endonuclease (Saci1096) which occurs in bacteria and some eukarya (63) but is absent from all other archaeal genomes, except Haloarcula marismortui (4). The existence of two alternative nucleotide excision repair pathways in S. acidocaldarius may account for the observation that it mutates at a rate similar to that of some mesophilic bacteria upon short-wavelength UV irradiation (31).

Restriction and modification enzymes.

S. acidocaldarius carries a restriction modification system involving the type II restriction enzyme SuaI (Saci1989), which recognizes the sequence GGCC (45) that is modified by a GGN4mCC methyltransferase (27). This system appears to be specfic to S. acidocaldarius because the 570 genomic copies of GGCC are underrepresented by factors of 2.5 and 5, respectively, relative to the genomes of S. tokodaii and S. solfataricus. The methyltransferase was assigned to Saci1975, which is absent from other crenarchaea but present in some euryarchaea. However, two other DNA methylase genes (Saci0651, -1283) are shared with the other two Sulfolobus genomes.

Transcription.

Sequences of the RNA polymerase of S. acidocaldarius were first analyzed by Zillig and colleagues (36, 46). The genome encodes 12 RNA polymerase subunits, all characteristic of the crenarchaea, and previous sequencing of the rpoE gene (17) missed a stop codon which has now been corrected. The rpoB gene does not exhibit a frameshift, as occurs in S. solfataricus (51). Seminal studies were also performed on archaeal transcription factors encoded in the S. acidocaldarius genome (6). The archaeon-eukaryote-type transcriptional initiation factors are all encoded as well as bacterium-like elongation factors NusG and NusA.

Four bacterium-like factors have been shown experimentally to regulate transcription in Sulfolobus species by binding near the B responsive elements and TATA-like motifs, including Sa-Lrp (19). Further analyses revealed 31 putative transcriptional regulators in the S. acidocaldarius genome, mainly belonging to Pfam families MarR, AsnC, and ArsR, most of which are conserved in all Sulfolobus genomes.

Translation.

Most of the genes implicated in translational functions have close homologs in the other Sulfolobus genomes. There are a single rRNA operon, single 5S RNA and 7S RNA genes, and 65 ribosomal protein genes: 28 for the small subunit and 37 for the large subunit, including homologs of the archaeon-eukaryote S25e and S26e. Forty-eight tRNA genes use 42 different anticodons, and there is a single pseudo-tRNAArg (GCG) gene. Three tRNAMet (CAT) genes are present, one of which (Saci0521) corresponds to the initiator tRNA (35), and tRNAAsp (GUC) and tRNAVal (UAC) genes are each present in duplicate copies. Nineteen tRNA genes contain introns, with 17 located between +1 and +2 bp 3′ to the anticodon loop and 1 in the D-loop of tRNAGlu (CTC). As for the other Sulfolobus genomes, the asparagine and glutamine aminoacyltransferases are absent. The genome encodes tRNA- and rRNA-modifying enzymes, including a cytosine-C5-methylase (Saci2312), tRNA nucleotidyl-transferase, and N-6 methylase. It also carries an intron-containing gene for the eukaryote-like Cbf5 protein (Saci0811, 0812) which is implicated in pseudouridylation (60), and it encodes an intron splicing enzyme (Saci0858).

Analysis of putative TATA-like promoter sequences and Shine-Dalgarno motifs revealed that a large fraction of mRNAs produced by single genes, or by the first genes of operons, are leaderless (Fig. 5). Their TATA-like motifs are located between positions −24 and −30, upstream from the start codon, and they lack a Shine-Dalgarno motif, as was observed for S. solfataricus (58). For genes located downstream from the first genes in putative operons, 48 to 54% exhibit Shine-Dalgarno motifs (Fig. 5) strongly biased towards the sequence 5′-GGTG-3′ (59).

FIG. 5.

Analysis of leader sequences of all putative protein-coding genes of the S. acidocaldarius genome. Results are presented for single genes and the first, middle, and terminal ORFs of predicted operons. The vertical bars represent the presence of (a) TATA-like motifs located 24 to 30 bp upstream from the start codon, (b) Shine-Dalgarno motifs, (c) neither motif, and (d) TATA-like and Shine-Dalgarno motifs.

Protein folding, modification, and degradation.

As in the other Sulfolobus species, but in contrast to several other archeaea, three similar proteins form the thermosome in S. acidocaldarius, which facilitates protein folding.

S. acidocaldarius encodes fewer protein kinases than S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii (2, 6 and 10 matches, respectively, of e < 0.01 to Pfam PKinase) but it exhibits a similar level to most other archaea.

For normal protein turnover, the S. acidocaldarius proteasome can potentially be assembled from an alpha subunit (Saci0613) and one, or both, of two beta subunits (Saci0662, 0909). Similarly to the other Sulfolobus species, it also carries a selenocysteine lyase gene (Saci0024) for converting selenocysteine into H2Se and alanine, presumably enabling it to utilize selenocysteine as a nutrient. Moreover, the protease thermopsin is encoded (Saci1714), which is absent from the other Sulfolobus species, suggesting that an alternative protein degradation system exists in S. acidocaldarius.

SRSR clusters.

There are four short regularly spaced repeat (SRSR) clusters in the genome. The 24-bp repeat sequences are A+T-rich and nonpalindromic and differ in sequence from those of other Sulfolobus species. Two large clusters (with 74 and 133 repeat copies) and two small clusters (carrying 4 and 11 repeat copies) occur within a 177-kb region of the genome (Fig. 2). The A+T-rich repeat sequences of the large clusters are identical, but they show no sequence similarity to the repeats of the small clusters which are closely similar to one another and exhibit interrupted inverted repeat structures (Fig. 2). SRSR clusters are often flanked by one to four cas genes (32) which are absent from the genomes lacking clusters. In S. acidocaldarius, two homologs of the cas1 and cas2 genes lie between the large clusters and the small SRSR clusters, and an interrupted cas4 gene homolog lies adjacent to a small SRSR cluster.

Recent studies on DNA replication in Pyrococcus and S. acidocaldarius (based on this genome sequence) have shown that some SRSR clusters are copied late in the replication cycle (39, 65). This is consistent with SRSR clusters having a role in chromosomal segregation (40), possibly as centromeres (16). A homolog of a DNA binding protein which specifically targets, and bends, the 24-bp repeat sequence (44) is encoded (Saci0449).

Furthermore, some of the regular spacer sequences of S. solfataricus and S. tokodaii correspond to sequences within Sulfolobus plasmid and viral genomes and may inhibit uptake of new extrachromosomal elements (41). Of the 220 spacer sequences in the S. acidocaldarius SRSRs, 3 gave multiple matches with known conjugative plasmid genes from Sulfolobus (23) and 3 matched sequences within the SA3 element, integrated in the S. acidocaldarius genome, which also corresponds to a conjugative plasmid (23). Given that RNA transcripts are produced from the SRSR clusters in Sulfolobus, any inhibitory mechanism is likely to involve RNA (54, 55; R. Lillestøl, unpublished).

Conclusion.

S. acidocaldarius is the third Sulfolobus genome to be sequenced, and by comparative analyses, we have presented a comprehensive gene map and annotation for this genome. It includes many previously unknown, mainly smaller, genes as well as many untranslated RNAs. Moreover, the numerous gene products which have been characterized experimentally for S. acidocaldarius are annotated in the genome, and several new features were discerned. A Sulfolobus database was established while comparing and annotating the protein and stable RNA genes of the three Sulfolobus genomes, which can be accessed at http://dac.molbio.ku.dk/dbs/Sulfolobus. It also contains supplementary information on protein-coding genes, including prerun searches against public databases with predictions for transmembrane regions and signal peptides as described in Materials and Methods. The Sulfolo bus database should provide a useful resource for the research community.

Acknowledgments

Genome sequencing was supported by an EU Cell Factory grant no. QLK3-CT-2000-00649, and the research was further supported by an Archaea Centre grant from the Danish Natural Science Research Council.

We thank Hoa Phan Thi-Ngoc for help in purifying DNA from BAC clones and Bettina Haberl (Epidauros Biotechnologie AG) for assistance in setting up sequencing reactions.

Footnotes

The paper is dedicated to the memory of Wolfram Zillig, one of the founders of Sulfolobus molecular biology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aagaard, C., H. Phan, S. Trevisanato, and R. A. Garrett. 1994. A spontaneous point mutation in the single 23S rRNA gene of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius confers multiple drug resistance. J. Bacteriol. 176:7744-7747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aagaard, C., J. Z. Dalgaard, and R. A. Garrett. 1995. Inter-cellular mobility and homing of an archaeal rDNA intron confers selective advantage over intron− cells of Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:12285-12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aagaard, C., I. Leviev, R. N. Aravalli, P. Forterre, D. Prieur, and R. A. Garrett. 1996. General vectors for archaeal hyperthermophiles: strategies based on a mobile intron and a plasmid. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 18:93-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baliga, N. S., R. Bonneau, M. T. Faccioti, M. Pan, G. Glusman, E. W. Deutsch, P. Shannon, Y. Chiu, R. S. Weng, R. R. Gan, P. Hung, S. V. Date, E. Marcotte, L. Hood, and W. V. Ng. 2004. Complete sequence of Haloarcula marismortui: a halophilic archaeon from the Dead Sea. Genome Res. 14:2221-2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bateman, A., E. Birney, L. Cerruti, R. Durbin, L. Etwiller, S. Eddy, S. Griffiths-Jones, K. Howe, M. Marshall, and E. Sonnhammer. 2002. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:276-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell, S. D., C. H. Botting, B. N. Wardleworth, S. P. Jackson, and M. F. White. 2002. The interaction of alba, a conserved archaeal chromatin protein and its regulation by acetylation. Science 296:148-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell, S. D., and S. P. Jackson. 2000. The role of transcription factor B in transcription initiation and promoter clearance in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J. Biol. Chem. 275:12934-12940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson, D. A., I. Karsch-Mizrachi, D. J. Lipman, J. Ostell, and D. L. Wheeler. 2003. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:23-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernander, R., A. Poplawski, and D. W. Grogan. 2000. Altered patterns of cellular growth, morphology, replication and division in conditional-lethal mutants of the thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Microbiology 146:749-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernander, R. 2003. The archaeal cell cycle: current issues. Mol. Microbiol. 48:599-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boeckmann, B., A. Bairoch, R. Apweiler, M. Blatter, A. Estreicher, E. Gasteiger, M. Martin, K. Michoud, C. O'Donovan, I. Phan, S. Pilbout, and M. Schneider. 2003. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledge base and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:365-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brock, T. D., K. M. Brock, R. T. Belly, and R. L. Weiss. 1972. Sulfolobus: a new genus of sulfur oxidising bacteria living at low pH and high temperature. Arch. Microbiol. 84:54-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brügger, K., P. Redder, Q. She, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, and R. A. Garrett. 2002. Mobile elements in archaeal genomes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206:131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brügger, K., P. Redder, and M. Skovgaard. 2003. “MUTAGEN: Multi User Tool for Annotating Genomes.” Bioinformatics 19:2480-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brügger, K., E. Torarinsson, L. Chen, and R. A. Garrett. 2004. Shuffling of Sulfolobus genomes by autonomous and non-autonomous mobile elements. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 32:179-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charlebois, R. L., Q. She, D. P. Sprott, C. W. Sensen, and R. A. Garrett. 1998. Sulfolobus genome: from genomics to biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:584-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darcy, T. J., W. Hausner, D. E. Awery, A. M. Edwards, M. Thomm, and J. N. Reeve. 1999. Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum RNA polymerase and transcription in vitro. J. Bacteriol. 181:4424-4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elferink, M. G., S. V. Albers, W. N. Konings, and A. J. Driessen. 2001. Sugar transport in Sulfolobus solfataricus is mediated by two families of binding protein-dependent ABC transporters. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1494-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enoru-Eta, J., D. Gigot, T.-L. Thia-Toong, N. Glansdorff, and D. Charlier. 2000. Purification and characterization of Sa-Lrp, a DNA-binding protein from the extreme thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius homologous to the bacterial global transcriptional regulator Lrp. J. Bacteriol. 182:3661-3672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garrett, R. A., P. Redder, B. Greve, K. Brügger, L. Chen, and Q. She. 2004. Archaeal plasmids, p. 377-392. In B. E. Funnell and G. J. Phillips (ed.), Plasmid biology. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Gordon, D., C. Abajian, and P. Green. 1998. Consed: a graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grabowski, B., and Z. Kelman. 2003. Archaeal DNA replication: eukaryal proteins in a bacterial context. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:487-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greve, B., S. Jensen, K. Brügger, W. Zillig, and R. A. Garrett. 2004. Genomic comparison of archaeal conjugative plasmids from Sulfolobus. Archaea 1:231-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grogan, D. W. 1989. Phenotypic characterization of the archaebacterial genus Sulfolobus: comparison of five wild-type strains. J. Bacteriol. 171:6710-6719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grogan, D. W. 1996. Exchange of genetic markers at extremely high temperatures in the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J. Bacteriol. 178:3207-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grogan, D. W., G. T. Carver, and J. W. Drake. 2001. Genetic fidelity under harsh conditions: analysis of spontaneous mutation in the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7928-7933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grogan, D. W. 2003. Cytosine methylation by the SuaI restriction-modification system: implications for genetic fidelity in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. J. Bacteriol. 185:4657-4661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grogan, D. W. 2004. Stability and repair of DNA in hyperthermophilic archaea. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 6:137-144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grote, M., J. Dijk, and R. Reinhardt. 1986. Ribosomal and DNA binding proteins of the thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 873:405-413. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo, R., X. Hong, and H. Li. 2003. SSh10b, a conserved thermophilic archaeal protein, binds RNA in vivo. Mol. Microbiol. 50:1605-1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobs, K. L., and D. W. Grogan. 1997. Rates of spontaneous mutation in an archaeon from geothermal environments. J. Bacteriol. 179:3298-3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen, R., J. D. Embden, W. Gaastra, and L. M. Schouls. 2002. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 43:1565-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawarabayasi, Y., Y. Hino, H. Horikawa, K. Jin-no, M. Takahashi, M. Sekine, S. Baba, A. Ankai, H. Kosugi, A. Hosoyama, S. Fukui, Y. Nagai, K. Nishijima, R. Otsuka, H. Nakazawa, M. Takamiya, Y. Kato, T. Yoshizawa, T. Tanaka, Y. Kudoh, J. Yamazaki, N. Kushida, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, S. Masuda, M. Yanagii, M. Nishimura, A. Yamagishi, T. Oshima, and H. Kikuchi. 2001. Complete genome sequence of an aerobic thermoacidophilic crenarchaeon, Sulfolobus tokodaii strain 7. DNA Res. 8:123-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krogh, A., B. Larsson, G. von Heijne, and E. Sonnhammer. 2001. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305:567-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuchino, Y., M. Ihara, Y. Yabusaki, and S. Nishimura. 1982. Initiator tRNAs from archaebacteria show common unique sequence characteristics. Nature 298:684-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langer, D., J. Hain, P Thuriaux, and W. Zilllig. 1995. Transcription in archaea: similarity to that in eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:5768-5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen, T., and A. Krogh. 2003. EasyGene—a prokaryotic gene finder that ranks ORFs by statistical significance. BMC Bioinformatics 4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lowe, T., and S. R. Eddy. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:955-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundgren, M., A. Andersson, L. Chen, P. Nilsson, and R. Bernander. 2004. Three replication origins in Sulfolobus species: synchronous initiation of chromosome replication and asynchronous termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101:7046-7051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mojica, F. J., C. Ferrer, G. Juez, and F. Rodriguez-Valera. 1995. Long stretches of short tandem repeats are present in the largest replicons of the archaea Haloferax mediterranei and Haloferax volcanii and could be involved in replicon partitioning. Mol. Microbiol. 17:85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mojica, F. J. M., C. Diez-Villasenor, J. Garcia-Martinez, and E. Soria. 2005. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 60:174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen, H., J. Engelbrecht, S. Brunak, and G. A. von Heijne. 1997. A neural network method for identification of prokaryotic and eukaryal signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Int. J. Neural Syst. 8:581-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Omer, A. D., T. M. Lowe, A. G. Russell, H. Ebhardt, S. R. Eddy, and P. P. Dennis. 2000. Homologs of small nucleolar RNAs in archaea. Science 288:517-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng, X., K. Brügger, B. Shen, L. Chen, Q. She, and R. A. Garrett. 2003. Genus-specific protein binding to the large clusters of DNA repeats (short regularly spaced repeats) present in Sulfolobus genomes. J. Bacteriol. 185:2410-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prangishvili, D., R. P. Vashakidze, M. G. Chelidze, and I. Yu. Gabriadze. 1985. A restriction endonuclease SuaI from the thermoacidophilic archaebacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. FEBS Lett. 192:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puehler, G., H. Leffers, F. Gropp, P. Palm, H.-P. Klenk, F. Lottspeich, R. A. Garrett, and W. Zillig. 1989. Archaebacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerases testify to the evolution of the eukaryotic nuclear genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:4569-4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Redder, P., Q. She, and R. A. Garrett. 2001. Non-autonomous mobile elements in the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Mol. Biol. 306:1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson, N. P., I. Dionne, M. Lundgren, V. L. Marsh, R. Bernander, and S. D. Bell. 2004. Identification of two origins of replication in the single chromosome of the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Cell 116:25-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schmidt, K. J., K. E. Beck, and D. W. Grogan. 1999. UV stimulation of chromosomal marker exchange in Sulfolobus acidocaldarius: implications for DNA repair, conjugation and homologous recombination at extremely high temperatures. Genetics 152:1407-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selig, M., K. B. Xavier, H. Santos, and P. Schonheit. 1997. Comparative analysis of Embden-Meyerhof and Entner-Doudoroff glycolytic pathways in hyperthermophilic archaea and the bacterium Thermotoga. Arch. Microbiol. 167:217-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.She, Q., R. K. Singh, F. Confalonieri, Y. Zivanovic, P. Gordon, G. Allard, M. J. Awayez, C.-Y Chan-Weiher, I. G. Clausen, B. Curtis, A. De Moors, G. Erauso, C. Fletcher, P. M. K. Gordon, I. Heidekamp de Jong, A. Jeffries, C. J. Kozera, N. Medina, X. Peng, H. Phan Thi-Ngoc, P. Redder, M. E. Schenk, C. Theriault, N. Tolstrup, R. L. M. Charlebois, W. F. Doolittle, M. Duguet, T. Gaasterland, R. A. Garrett, M. Ragan, C. W. Sensen, and J. van der Oost. 2001. The complete genome of the crenarchaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus P2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.She, Q., K. Brügger, and L. Chen. 2002. Archaeal integrative genetic elements and their impact on genome evolution. Res. Microbiol. 153:325-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shizuya, H., B. Birren, U. J. Kim, V. Mancino, T. Schlepak, Y. Tachiri, and M. Simon. 1992. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300 kbp fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8794-8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tang, T.-H., J.-P. Bachellerie, T. Rozhdestvensky, M.-L. Bortolin, H. Huber, M. Drungowski, T. Elge, J. Brosius, and A. Hüttenhofer. 2002. Identification of 86 candidates for small non-messenger RNAs from the archaeon Archaeoglobus fulgidus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7536-7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang, T.-H., N. Polacek, M. Zywicki, H. Huber, K. Brügger, R. Garrett, J. P. Bachellerie, and A. Hüttenhofer. 2005. Identification of novel non-coding RNAs as potential antisense regulators in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:469-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tatusov, R. L., D. A. Natale, I. V. Garkavtsev, T. A. Tatusova, U. Y. Shankavaram, B. S. Rao, B. Kiryutin, M. Y. Galpein, N. D. Fedorova, and E. V. Koonin. 2001. The COG database: new developments in phylogenetic classification of proteins from complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:22-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thia-Toong, T. L., M. Roovers, V. Durbecq, D. Gigot, N. Glansdorff, and D. Charlier. 2002. Genes of de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis from the hyperthermoacidophilic crenarchaeote Sulfolobus acidocaldarius: novel organization in a bipolar operon. J. Bacteriol. 184:4430-4441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tolstrup, N., C. W. Sensen, R. A. Garrett, and I. G. Clausen. 2000. Two different and highly organized mechanisms of translation intitiation in the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Extremophiles 4:175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torarinsson, E., H.-P. Klenk, and R. A. Garrett. 2005. Divergent transcriptional and translational signals in Archaea. Environ. Microbiol. 7:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watanabe, Y., S. Yokobori, T. Inaba, A. Yamagishi, T. Oshima, Y. Kawarabayashi, H. Kikuchi, and K. Kita. 2001. Introns in protein coding genes in archaea. FEBS Lett. 510:27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.White, M. F. 2003. Archaeal DNA repair: paradigms and puzzles. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31:690-693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White, R. H. 1997. Purine biosynthesis in the domain Archaea without folates or modified folates. J. Bacteriol. 179:3374-3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yonemasu, R., S. J. McCready, J. M. Murray, F. Osman, M. Takao, K. Yamamoto, A. R. Lehmann, and A. Yasui. 1997. Characterization of the alternative excision repair pathway of UV-damaged DNA in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:1553-1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang, R., and C. T. Zhang. 2003. Multiple replication origins of the archaeon Halobacterium species NRC-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 302:728-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zivanovic, Y., P. Lopez, H. Philippe, and P. Forterre. 2002. Pyrococcus genome comparison evidences chromosome shuffling-driven evolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:1902-1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]