Abstract

Purpose

The presence of chaperones during intimate physical examinations is a matter of ongoing debate. While most guidelines recommend the use of chaperones in all cases, there are no clinical trials specifically investigating intimate exams performed on women by male physicians. We aimed to evaluate female patients’ perceptions regarding the presence or absence of chaperones during proctological examinations conducted by male physicians.

Methods

In this randomised clinical trial, patients were assigned, unaware that they were participating in a study, to either Group 1 (without a chaperone during their proctological exam) or Group 2 (with a chaperone). After the appointment, they completed a questionnaire regarding the examination they had just undergone. The study was conducted at two hospitals in Southern Brazil.

Results

Ninety-five patients were included in each group. The mean (SD) comfort score was 8.3 (2.9) with a chaperone and 8.8 (2.5) without a chaperone (P = 0.25). When asked if they would want the exam performed the same way in the future, 72.6% in Group 1 answered ‘yes’, compared to 58.9% in Group 2 (P = 0.046). In Group 2, 48.4% of patients did not feel more protected by the chaperone, while none of the patients in Group 1 felt less protected without one.

Conclusions

Forgoing chaperones during proctological examinations of women, when the physician is male, is well accepted by most patients. Preferences regarding chaperones are complex, demanding a selective approach. The use of chaperones should remain a recommendation, not a requirement, to accommodate individual needs while maintaining the doctor-patient relationship.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03615586.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00384-024-04796-4.

Keywords: Chaperone, Intimate examination, Doctor-patient relationship, Proctology

Introduction

The evolution of medicine has led to the continuous integration of new technologies into clinical practice. Physicians now have access to a wide array of sophisticated tools that enhance speed and accuracy of diagnosis. Nonetheless, concerns are rising that these technological advancements could potentially undermine the doctor-patient relationship [1]. Recent studies emphasise the importance of adopting a patient-centred approach. Even in the current context, the way a doctor behaves and addresses delicate subjects remains essential for building trust with the patient and achieving good clinical outcomes [2, 3].

The present study investigates a sensitive aspect of the doctor-patient relationship: the conduction of intimate physical exams. It was initially inspired by ‘Naked,’ a text by the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande, that was published as both a book chapter and an article in the New England Journal of Medicine [4, 5]. In his work, Gawande reflects on his own uncertainties regarding the subject and, after examining different practices around the world, discusses whether a chaperone should be present during pelvic or rectal examinations, particularly when the physician is male and the patient is female. He states: ‘So do male physicians make women more comfortable with intimate examinations by involving a chaperone or not? My bet is that bringing an aide in helps more than it hurts. But we don’t know; the study has never been done.’

Such a study has, in fact, never been done. A PubMed search (August 30, 2024) confirmed the absence of clinical trials on this subject. In practice, the use of chaperones depends on the individual decision and preference of each doctor. A study conducted in the USA assessed, through a questionnaire survey, whether internal medicine residents plan to use chaperones during intimate examinations. It was demonstrated that male residents are more likely to use companions during gynaecological examinations, but less likely to do so during breast or rectal examinations [6]. Similarly, a study conducted in Norfolk, England, found that 45% of male general clinicians never or rarely used chaperones in intimate examinations of women. Only 2% of male physicians used chaperones when examining men, and only 8% of female physicians did so when examining women [7].

Although women are routinely examined by male proctologists in different parts of the world, there is little to no understanding on how they feel during rectal exams when a third person is present. It is uncertain whether a female nurse in the room provides a sense of protection or compromises the patient’s privacy. Our initial hypothesis was that the presence of a chaperone would result in a higher level of comfort for the patients.

Considering the practical and legal implications of this issue, the objectives of the present study were as follows: (1) to assess female patients’ perceptions regarding the presence or absence of chaperones during rectal exams performed by male physicians; (2) to determine how protected they felt during their exams; and (3) to evaluate their preferences regarding the presence of a chaperone at future medical visits.

Methods

Trial design

This is a two-armed, parallel, randomised clinical trial with an allocation ratio of 1 to 1.

Study population

Women aged 18 years or older who presented unaccompanied for an initial coloproctological visit were eligible for the study. Patients already under clinical follow-up or undergoing any therapeutic procedure during the appointment were excluded.

The study was conducted in two different outpatient clinics of coloproctology in the city of Porto Alegre, Southern Brazil. The first one is located at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, a large academic hospital that takes care of patients referred from the Brazilian Public Health System, usually with a low socioeconomic background. The second is located at Hospital Mae de Deus, an institution that serves higher-income patients in a private practice system.

Randomisation and interventions

Patient enrolment commenced on August 31, 2018, but was suspended in January 2020, due to the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Enrolment resumed in October 2022, after mask mandates in hospitals ended, being completed on October 30, 2023.

The peculiarities of this study led us to follow a series of specific steps. To avoid the Hawthorne effect, wherein participants alter their behaviour due to awareness of being part of an experiment [8], we designed the study to minimise cues about the expected outcomes. Initially, none of the patients were aware that they would be participating in a study. They were randomised according to a computer-generated randomisation list (Python script,) into two study groups: Group 1—without the presence of a chaperone during the proctological exam; Group 2—with the presence of a chaperone. As recommended in the literature, subjects were allocated in blocks of four [9]. The allocation sequence was concealed using coded numerically sequenced opaque sealed envelopes, which were opened immediately before the consultation.

All patients were examined by one of two male proctologists (DCD, PCC), each with over 20 years of experience. They became aware of the allocation just moments before calling the patients into the office. When a chaperone was used, the doctor invited her into the room after obtaining the medical history, before starting the physical examination. Patients in Group 2 agreed to have a female nurse during their physical examination. In Group 1, the doctor proceeded directly to the physical examination after the medical history.

Once the appointment was finished, the physician informed patients about the study. Those who expressed interest in participating were then interviewed by a female research assistant (without the coloproctologist’s presence), who explained the study and obtained the signed informed consent, assuring that participation was voluntary and would not affect their treatment. They were also assured that the examining physician would not have immediate access to their answers. Confidentiality and anonymity of the collected data were guaranteed. After that, patients completed a questionnaire regarding the examination they had just undergone. This instrument was developed according to the literature [10]. Initially, a panel of experts, including coloproctologists, nurses, and patient representatives, reviewed the initial pool of items for relevance and comprehensiveness. A pilot test was then conducted to refine the questions and ensure the content validity, construct validity, and reliability.

The questionnaire consisted of six questions. The first question answered by the patients was ‘How did you feel during the examination?’ Responses were recorded on a visual scale ranging from 0 (totally uncomfortable) to 10 (totally comfortable). All subsequent questions were categorical, offering two or three possible answers.

Besides administering the questionnaire, the female research assistant was also responsible for collecting each patient's demographic and clinical data.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the patient’s level of comfort (or embarrassment) depending on whether a chaperone was present or absent during the examination. We also evaluated patient preferences regarding the presence of a chaperone at future visits and how protected they felt during their exams.

Statistical analysis

The sample size was calculated for a superiority trial with binary outcomes. Assuming 80% power, a 5% alpha error, and an increase in positive experience from 14 to 31% with a chaperone, at least 91 patients per group were needed. These figures were based on Teague et al.’s study [11], which found that more women preferred a chaperone if the examining physician was male.

The D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test was used to verify the Gaussian distribution. Categorical data were analysed with the chi-square test; the chi-square trend test was used for more than two categories. Age between groups was compared using the Student t-test with Welch’s correction for unequal variances. Confidence intervals were calculated to assess differences between groups. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.3 for MacOS, GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Brazilian Ethical and Research Committee and received the Certificate of Ethical Presentation (CAAE: 9763917.6.0000.5327). It adhered to the modified CONSORT guidelines for Randomized Trials of Nonpharmacologic Treatments [12] and was registered on Clinical Trials under the number NCT03615586. Ethics in Research Committees of both participating institutions approved the protocol. All patients provided written informed consent.

Results

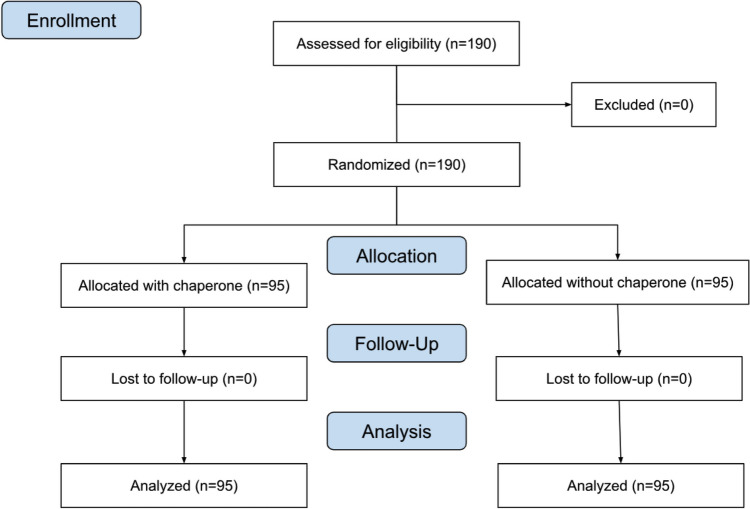

A total of 190 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1). Their clinical and demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1, with no significant differences between the study groups. The study population was predominantly composed of white, married women with elementary or middle school education, with a mean age of 52.1 years (range 21 to 77 years). Most patients reported having a religious affiliation, with 82% identifying as Catholic.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing patient selection

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studied population. Numbers are n (%), except when stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Without chaperone n = 95 |

With chaperone n = 95 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD)* | 52.1 (13.4) | 52.3 (15.5) | 0.92a |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 10 (10.5) | 16 (16.8) | 0.12b |

| Married | 52 (54.7) | 52 (54.7) | |

| Divorced | 18 (18.9) | 8 (8.4) | |

| Widow | 15 (15.7) | 19 (20.0) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 76 (80) | 78 (82.1) | 0.71c |

| Non-white | 19 (20) | 17 (17.9) | |

| Level of education | |||

| Elementary/MIDDLE school | 47 (49.5) | 48 (50.5) | 0.14b |

| High school | 33 (34.7) | 23 (24.2) | |

| Higher education | 15 (15.8) | 24 (25.3) | |

| Religious affiliation | |||

| Yes | 85 (89.5) | 82 (86.3) | 0.5c |

| No | 10 (10.5) | 13 (13.7) | |

| Type of healthcare | |||

| Public system | 75 (78.9) | 76 (80) | 0.85c |

| Private system | 20 (21.1) | 19 (20) | |

| Type of chief complaint | |||

| Abdominal symptoms | 25 (26.3) | 21 (22.1) | 0.49c |

| Anal symptoms | 70 (73.7) | 74 (77.9) | |

| Examining physician | |||

| Physician #1 | 47 (49.5) | 48 (50.5) | 0.88c |

| Physician #2 | 48 (50.5) | 47 (49.5) | |

aUnpaired t test with Welch’s correction

bChi-square for trend

cChi-square test

The mean comfort score during the exam, assessed by the first question of the questionnaire, was 8.8 (SD = 2.5) without a chaperone present and 8.3 (SD = 2.9) with a chaperone (P = 0.25, Welch’s t-test).

The subsequent questions and answers for each group are presented in Table 2. There was a significant difference for question 6, ‘In the event of a re-examination, would you like the doctor to perform the exam in the same way?’ Sixty-nine patients (72.6%; 95% CI: 62.9–80.5%) in Group 1 answered yes, compared to 56 patients (58.9%; 95% CI: 48.9–68.3%) in Group 2 (P = 0.046, chi-square). The 13.68% difference (95% CI: 0.02–26.5%) favoured exams without a chaperone.

Table 2.

Patient’s responses with and without chaperones

|

Patients without chaperone n (%) Group 1 |

Patients with chaperone n (%) Group 2 |

P-value or difference between groups * (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|

|

1. How did you feel during the examination? b—mean (SD) 8.8 (2.5) |

1. How did you feel during the examination? b—mean (SD) 8.3 (2.9) |

0.25 b |

|

2. How did you feel about not having a person besides the doctor during the exam? Bad: 1 (1.1) Indifferent: 33 (34.7) Good: 61 (64.2) |

2. How did you feel about having a person besides the doctor during the exam? Bad: 4 (4.2) Indifferent: 21 (22.1) Good: 70 (73.7) |

3.1%* (− 2.1 to 9.3%) |

|

3. Do you think the absence of a female chaperone made the examination: Better: 31 (32.6) Did not change it: 62 (65.3) Worse: 2 (2.1) |

3. Do you think the presence of a female chaperone made the examination: Better: 43 (45.3) Did not change it: 50 (52.6) Worse: 2 (2.1) |

0%* (− 5.4 to 5.4%) |

|

4. Did you feel less protected without the presence of another person? Yes: 0 (0) No: 95 (100) |

4. Did you feel more protected with the presence of another person? Yes: 49 (51.6) No: 46 (48.4) |

51.5%* (40.9 to 61.3%) |

|

5. Would you rather have your exam performed in the presence of a female chaperone? Yes: 4 (4.2) Indifferent: 4 (4.2) No: 87 (91.6) |

5. Would you rather have your exam performed without the presence of a female chaperone? Yes: 4 (4.2) Indifferent: 8 (8.4) No: 83 (87.4) |

4.2%* (− 4.8 to 13.3%) |

|

6. In the event of a reexamination, would you like the doctor to conduct the examination in the same way (without a chaperone)? Yes: 69 (72.6) No: 26 (27.4) |

6. In the event of a reexamination, would you like the doctor to conduct the examination in the same way? (with a chaperone)? Yes: 56 (58.9) No: 39 (41.1) |

13.6%* (0.2 to 26.5%) |

aConfidence interval

bHow did you feel during the examination? Responses were recorded on a visual scale ranging from ‘0’, indicating ‘totally uncomfortable’, to ‘10’, indicating ‘totally comfortable’

cUnpaired t-test with Welch’s correction

*The difference was considered a dichotomous outcome. In questions 2, 3, and 5: indifferent and good, better and did not change it, and yes and indifferent, were combined, respectively

There was no correlation between the responses and the patients’ specific characteristics, such as educational level, religiousness, or type of healthcare (private or public system). Responses did not significantly vary by physician or by the study inclusion period.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the practice of not using a chaperone during proctologic examinations of women, when the examining physician is a man, is well accepted by the patients. The level of comfort observed was high and similar in both groups. Furthermore, no women felt less protected without a chaperone present.

These results do not align with the recommendations of various medical councils worldwide concerning the use of a third person during intimate examinations. In England, the General Medical Council recommends that patients should be offered a chaperone for intimate examinations, regardless of the patient’s or the physician’s gender [13]. In Canada, guidelines vary by province. In Ontario, both patients and doctors can request a third person during intimate examinations and, if necessary, can request that the examination be postponed if a chaperone is not available [14].

In the USA, there are no national guidelines for chaperone use, and recommendations vary by state [15]. In Florida, it is not required, but it is highly recommended [16]. In Oregon, as of July 1, 2023, doctors are required to offer a chaperone for genital, rectal, and breast examinations [17]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College Health Association recommend the use of chaperones for all breast, genital, and rectal examinations [18, 19]. On the other hand, the American College of Physicians and the American Medical Association advocate for shared decision-making between doctor and patient [20, 21].

Most guidelines, therefore, imply that chaperones are beneficial and should be encouraged to protect both patients and doctors. However, their presence can potentially alter the natural dynamic of the medical encounter. Introducing a third party can cause embarrassment to patients, who may become reluctant to share sensitive information. They might interpret it as a sign of distrust from the doctor, potentially weakening the doctor-patient relationship [22, 23].

From the physician’s perspective, there may be two positions: one where the physician does not feel comfortable examining a patient alone and routinely uses a chaperone and another where the physician does not consider a chaperone necessary, believing it might compromise patient trust and privacy. In the latter, even offering a chaperone can change the natural course of the examination [24–26].

From the patient’s perspective, there are a limited number of studies investigating the necessity of chaperones. A survey in England aimed to assess patient preferences about the subject. Questionnaires were mailed to individuals of both genders, with responses returning from 190 men and 261 women. Fifteen percent of respondents opposed having a chaperone, while another 15% preferred one. Fifty-nine percent would feel uncomfortable if a chaperone was present without their consent. Most patients who declined a chaperone cited concerns about confidentiality and discomfort with a third person being present [27].

A similar study in Australia, also using mail-in questionnaires, found that more women preferred a chaperone if the examining physician was male compared to female (31% vs. 14%, P < 0.01) [11]. In Hong Kong, a survey of 150 patients waiting for consultations at a teaching hospital revealed that over 90% considered a chaperone appropriate for intimate examinations, and 84% felt doctors should always request one, regardless of gender [28]. In a survey of women attending gynaecological consultations at a large teaching hospital in Nigeria, 124 (53.9%) preferred having a chaperone during pelvic examinations, while 106 (46.1%) did not [29].

Our study is unique, as it analyses patients’ actual experiences during examinations with and without a chaperone. This approach differs from previous surveys, which relied on mail-in or pre-consultation questionnaires and may not reflect real-time experiences.

Only 2% of patients in Group 1 felt the absence of a chaperone made the examination worse (question 2), and 4% would have preferred the examination to have been conducted with a chaperone present (question 5). The interpretation of these results will certainly depend on what the physician believes and practices. Those who always use chaperones may consider 2% to be an unacceptable number and use it as justification for their practice. In contrast, those who do not routinely use chaperones may view the data as supporting their approach. Interestingly, in Group 2, the percentage of patients who would have preferred to be examined without a chaperone (question 5) was also 4%.

In Table 2, we compare responses from the two groups. Although questions 2 to 5 involve different scenarios (with or without a chaperone), the addressed issues are similar. Thus, we decided to present a statistical comparison between the groups, while acknowledging potential limitations in the analysis.

The answers to question 4 were notable: 48.4% of patients in Group 2 did not feel more protected by the presence of a chaperone, while none of the patients in Group 1 felt less protected by its absence, resulting in a 51.5% difference. These somewhat surprising results emphasise the complexity of the psychological factors involved in intimate examinations. It seems that when the examination is conducted properly, the absence of a third party (Group 1) does not appear to elicit a sense of vulnerability in the patients. In contrast, the findings from Group 2 suggest that the mere presence of a chaperone may imply to about half of the patients that such ‘protection’ is in fact necessary, and its absence could represent a situation of increased exposure or vulnerability.

There was a significant difference between the groups regarding question 6 ‘In the event of a re-examination, would you like the doctor to perform the exam in the same way?’ More than 72% of patients in Group 1 answered ‘yes’, compared to 58.9% in Group 2. The fact that 27% in Group 1 responded negatively, indicating a preference for a chaperone in future examinations, contrasts with their previous responses showing that none felt unprotected during the examination and only 4% would have preferred having a chaperone present. This finding indicates that for a minority of the patients examined alone, despite the overall acceptance and positive evaluation of the examination, there remains a certain degree of discomfort during the process. On the other hand, the observation that 41% of patients in Group 2 responded ‘no’, preferring not to have a chaperone present again, suggests that once a strong bond is established with the physician, many patients no longer consider a third person necessary for future examinations. These results indicate that even a careful and empathetic doctor may occasionally make a patient uncomfortable, with or without a chaperone.

Considering the potential influences of social characteristics on the responses, we took care to include patients from two different social strata based on the institution where they were treated and found no significant differences in response patterns. Additionally, we examined the potential influence of demographic, cultural, and the type of primary complaint-related factors motivating the medical visit, and similarly, observed no changes in response patterns based on these factors.

This is the first clinical trial investigating the performance of proctological exams on female patients by male physicians. Studying this subject represented a challenging methodological issue; so, we had to adopt several safeguards during the development and administration of the questionnaire to ensure the reliability of the responses. It was crucial that patients were unaware of the study during the physical exam. Additionally, all interviews were conducted by female researchers without the involvement of the examining physicians. We were able to provide novel insights on a highly prevalent clinical scenario. Our results may serve as a basis for doctors to evaluate their own practice, considering their patients’ feelings and expectations regarding intimate physical exams.

Our findings have several clinical implications. Clearly, no single approach can universally satisfy the expectations of all patients. Thus, the doctor conducting proctological examinations should be able to recognise the need for a chaperone and, when deemed appropriate, offer this option to the patient. The mandatory implementation of chaperones in all examinations, as recommended by various guidelines, does not seem to represent the optimal solution and warrants reconsideration. Future research should aim to identify the factors influencing patients’ preferences for or against the presence of a chaperone during intimate examinations. Additionally, it would be valuable to assess the effects of chaperone presence in other intimate examination contexts, such as breast and gynaecological exams, which involve distinct psychosocial considerations.

Our study has some inherent methodological drawbacks. Patients were examined by only two experienced coloproctologists, each with over 20 years in practice. Examinations by younger or less experienced physicians might yield different outcomes. Additionally, the data may be influenced by cultural or religious factors related to the patients’ nationality and social background. Therefore, studies involving other populations may produce different results. These aspects should be considered when interpreting the study’s results.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that there is no single ideal approach for all patients. The recommendation for using a chaperone during proctological examinations of women by male doctors should remain exactly that—a recommendation, not a mandatory requirement. Adopting a patient-centred approach appears to be key to addressing individual needs while maintaining a trusting doctor-patient relationship. Further research should aim to investigate the impact of chaperone presence on patient clinical outcomes and to refine guidelines that balance safety, comfort, and trust in medical practice.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

DCD and PCC conceived and designed the study, conducted data collection, and analysed the results. DCD and RFS performed the statistical analysis, prepared tables and figures, and wrote the manuscript. BB collected data, conducted most interviews, and revised the article. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version.

Funding

This study did not receive any funding.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Marino F, Alby F, Zucchermaglio C, Fatigante M (2023) Digital technology in medical visits: a critical review of its impact on doctor-patient communication. Front Psychiatry 14:1226225. 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1226225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H (2014) The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One 9:e94207. 10.1371/journal.pone.0094207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrard V, Schmid Mast M, Jaunin-Stalder N, Junod Perron N, Sommer J (2018) Patient-centeredness as physician behavioral adaptability to patient preferences. Health Commun 33:593–600. 10.1080/10410236.2017.1286282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gawande A (2005) Naked. N Engl J Med 353:645–648. 10.1056/NEJMp058120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gawande A (2007) Naked. In: Better: a surgeon’s notes on performance. 1st edn. Picador, New York, pp 73–83

- 6.Ehrenthal DB, Farber NJ, Collier VU, Aboff BM (2000) Chaperone use by residents during pelvic, breast, testicular, and rectal exams. J Gen Intern Med 15:573–576. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.10006.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conway S, Harvey I (2005) Use and offering of chaperones by general practitioners: postal questionnaire survey in Norfolk. BMJ 330:235–236. 10.1136/bmj.38320.472986.8F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR (2014) Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J Clin Epidemiol 67:267–277. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altman DG, Bland JM (1999) How to randomise. BMJ 319:703–704. 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone DH (1993) Design a questionnaire. BMJ 307:1264–1266. 10.1136/bmj.307.6914.1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teague R, Newton D, Fairley CK et al (2007) The differing views of male and female patients toward chaperones for genital examinations in a sexual health setting. Sex Transm Dis 34:1004–1007. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3180ca8f3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P (2017) CONSORT statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic trial abstracts. Ann Intern Med 167:40–47. 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Intimate examinations and chaperones (2024) London, UK: General Medical Council. https://www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standards-for-doctors/intimate-examinations-and-Chaperones/intimate-examinations-and-chaperones. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 14.Price DH, Tracy CS, Upshur RE (2005) Chaperone use during intimate examinations in primary care: postal survey of family physicians. BMC Fam Pract 21(6):52. 10.1186/1471-2296-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Code of medical ethics: use of chaperones (2024) American Medical Association. https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/sites/amacoedb/files/2022-08/1.2.4.pdf. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 16.(2024) Are physicians required to have a chaperone present in the room when examining patients?. Tallahassee, FL: Florida Board of Medicine. https://flboardofmedicine.gov/help-center/are-physicians-required-to-have-a-chaperone-present-in-the-room-when-examining-patients/. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 17.Offering a medical chaperone, 2023 (2024) Portland, OR: Oregon Medical Board. https://www.oregon.gov/omb/topics-of-interest/pages/chaperone.aspx. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 18.Sexual misconduct: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 796 (2020). Obstet Gynecol 135:e43-50. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACHA Guidelines (2024) Best practices for sensitive exams [Internet]. Silver Springs, MD: American College Health Association. https://www.acha.org/documents/resources/guidelines/ACHA_Best_Practices_for_Sensitive_Exams_October2019.pdf. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 20.Policy Compendium Summer (2024) Washington, DC: The American College of Physicians, Division of Government Affairs and Public Policy. https://www.acponline.org/sites/default/files/documents/advocacy/where_we_stand/assets/acp-policy-compendium.pdf. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 21.Use of Chaperones (2024) Chicago, IL: American Medical Association. https://code-medical-ethics.ama-assn.org/ethics-opinions/use-chaperones. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 22.Morrow J (1999) Chaperones for genital examination. We should offer a chaperone but not inflict one. BMJ 319:1266 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Randall S, Webb A, Kishen M (1999) Chaperones for genital examination. Presence of chaperone may interfere with doctor-patient relationship. BMJ 319:1266 [PubMed]

- 24.Stanford L, Bonney A, Ivers R, Mullan J, Rich W, Dijkmans-Hadley B (2017) Patients’ attitudes towards chaperone use for intimate physical examinations in general practice. Aust Fam Physician 46(11):867–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Hecke O, Jones K (2014) What should GPs be doing about chaperones? Br J Gen Pract 64:589–590. 10.3399/bjgp14X682489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Hecke O, Jones K (2015) The use of chaperones in general practice: is this just a ‘Western’ concept? Med Sci Law 55:278–283. 10.1177/0025802414557114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitford DL, Karim M, Thompson G (2001) Attitudes of patients towards the use of chaperones in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 51:381–383 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan VC, Choy HT, Kwok GY et al (2017) Chaperones and intimate physical examinations: what do male and female patients want?. Hong Kong Med J 23:35–40. 10.12809/hkmj164899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nkwo PO, Chigbu CO, Nweze S, Okoro OS, Ajah LO (2013) Presence of chaperones during pelvic examinations in southeast Nigeria: women’s opinions, attitude, and preferences. Niger J Clin Pract 16:458–461. 10.4103/1119-3077.116889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.