Abstract

Privacy fatigue caused by privacy data disclose and the complexity of privacy control has become an important factor influencing people’s privacy decision-making behavior. At present, academia mainly studies privacy fatigue as a key determinant to explain the privacy paradox problem, but there is insufficient attention to its influencing factors and specific pathway of occurrence. Exploring the antecedents of privacy fatigue is of great significance for alleviating users’ subjective privacy detachment and promoting privacy protection. Based on the Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) theoretical framework, this study aims to explore the antecedents of privacy fatigue through the qualitative comparative analysis method of fuzzy set (fsQCA). The results show that there are three patterns of pathways which lead to privacy fatigue, namely the rational pattern, emotional pattern, and strain pattern. This study not only provides theoretical reference for understanding the antecedents of privacy fatigue among users but also offers new practical solutions for user privacy management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-84646-z.

Keywords: Privacy fatigue, Privacy protection, Mobile social media

Subject terms: Information technology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Social media, as a content production platform based on user relationships, has experienced rapid development relying on advancements in internet technology, gradually becoming an indispensable part of people’s daily lives. However, with an increasing amount of user personal information being disclosed on mobile social media, users’ privacy security faces growing risks, for example, in 2020, the personal information of 5.38 billion Weibo users was priced for sale, and in 2021, the personal information of 5.53 billion Facebook users was leaked1,2. Privacy management has gradually become a challenge that social media users must confront in the digital age.

This has also made privacy issues one of the focal points of attention in the field of information management, with scholars focusing on exploring the relationship between privacy attitudes and privacy behavior. Privacy concern is considered a core concept in measuring privacy attitudes in the field of information management3. It measures the extent to which users are concerned about the risks of controlling, collecting, and using their personal information and is believed to be a key factor influencing privacy behavior, such as engaging in more privacy protection strategies4, reducing information disclosure and sharing3, concealing privacy information, etc5. However, these known factors may not account for all privacy decisions, as the complexity and required effort for privacy assurance protocols continue to increase6. Several studies have suggested that complex privacy policies and management could lead to a negative psychological state called privacy fatigue, which even surpasses the influence of privacy concern on privacy behavior decisions6,7. This privacy fatigue, caused by the complexity of data disclose and privacy controls, can lead people to engage in behaviors of abandoning privacy protection, thereby exacerbating the discrepancy between privacy concern and the willingness to engage in privacy protection behaviors8, and is one of the powerful perspectives for explaining the privacy paradox among social media users in the new stage7,9. Therefore, the emergence of privacy fatigue in the development stage of mobile social media has become an issue that deserves attention in safeguarding the security behavior of social media users. However, despite research emphasizing the universality and importance of privacy fatigue among social media users8, explicitly exploring the antecedent variables of privacy fatigue is scarce, and there is a lack of exploration of the patterns of its occurrence.

Based on this, this paper takes the phenomenon of privacy fatigue among mobile social media users as the starting point, and proposes the core research question of this paper: What are the specific antecedents of privacy fatigue phenomenon? The question mainly covers the following aspects: In the context of mobile social interaction, which factors influence the emergence of user privacy fatigue? Do these factors have certain combination rules, leading to the occurrence of privacy fatigue among mobile social media users?

In order to answer the research questions above, this study introduced Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) to construct the research model suitable to the research context. In addition, in order to analyze the “joint effects” and configuration effects of various factors on privacy fatigue, this study adopts the Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) method to explore the specific influencing factors and specific pathways of privacy fatigue, aiming to provide important theoretical references for understanding the privacy behavior of users on social media and help reduce users’ privacy fatigue and solve their privacy issues.

The rest of this paper is organized as such. Section 2 is the theoretical backgrounds, including literature review which briefly discusses prior studies concerning privacy fatigue, as well as the theoretical framework of this paper, namely the Stressor-Strain-Outcome theory. Section 3 outlines the research design of the paper, proposing the study’s research framework and variable settings based on the theoretical foundations, introducing the research method of Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis, and also elaborating on the questionnaire design and data collection methods of this study. The process of data analysis and the directional comparative analysis results of the phenomenon of privacy fatigue are presented in Sect. 4. Finally, Sect. 5 provides the summary of the paper.

Literature review

The research of privacy fatigue

Fatigue is described as a subjective, unpleasant feeling of physical or mental exhaustion8. Specifically, fatigue stems from a sense of exhaustion commonly experienced when facing high demands and unattainable goals, which may initially lead to psychological stress and potentially result in a permanent state of fatigue, known as “burnout,” affecting individuals’ behavioral decisions, mainly manifested in individuals’ inclination to make decisions to reduce workload10. In the realm of mobile social media, facing an increasingly challenging privacy environment, frequent data disclose have heightened users’ skepticism about their ability to control their own privacy, corresponding to the increasing online and complex measures for personal privacy protection, while also raising doubts among users about the effectiveness of the measures they take. This fatigue caused by the complexity of data leaks and privacy control is referred to as privacy fatigue8.

The phenomenon of user privacy fatigue is believed to be primarily characterized by cynicism and emotional exhaustion. Cynicism is a negative attitude that arises when target expectations cannot be met, while emotional exhaustion represents the depletion of personal emotional resources9. In terms of behavioral outcomes, previous studies have suggested that “behavioral disengagement” is a major result of fatigue, manifested as individuals reducing efforts due to excessive stress, resulting in relaxation of routine security practices9, or even directly abandoning the conquering of high task demands11. Specific protective disengagement behaviors also include users directly skipping the reading of privacy policies and choosing to accept8, increasing personal information disclosure6, and choosing to use default settings (i.e., making every individual on the website publicly accessible)12. Hargittai & Marwick’s study summarized through interviews that users’ spiritual alienation or cynicism toward privacy issues is an important reason for the disconnection between privacy concerns and privacy disclosure behavior13; Zhu et al.‘s latest research also shows that in e-commerce, social media, and other scenarios, users invest a considerable amount of time, money, and cognitive effort, resulting in very high sunk costs. In such situations, privacy fatigue as a coping mechanism promotes disclosure behavior7.

Currently, most research on “fatigue” focuses on the analysis of factors influencing social media fatigue. The research found that the fatigue generated by users is influenced by two factors: individual characteristics and external environmental factors. Among them, individual factors include users’ individual characteristics14, privacy attitudes15, information literacy16, and cost considerations17, while environmental influences include interpersonal pressure18, information overload19, and forced use17.

However, it is important to note that social media fatigue and privacy fatigue are two distinct concepts. Social media fatigue reflects users’ negative emotions about their motives for using social media20, it mainly triggers discontinuance and displacement behaviors of users towards social media21,22, while privacy fatigue emphasizes users’ negative attitudes toward privacy protection decisions, its main outcome is in the results of privacy-protective behavior, privacy disclosure behavior23,24.The latest research has attempted to use privacy fatigue as a new behavioral indicator to explain the emergence of the privacy paradox phenomenon25, which provides a better understanding of the privacy behavior of social media users. Although some studies have attempted to use privacy fatigue as the latest behavioral evidence to explain the presentation of privacy paradox phenomena21, they have paid less attention to the determinants of privacy fatigue. Privacy fatigue is important, but previous literature has paid less attention to the causes of privacy fatigue, so to fill the research gap in exploring the causes of privacy fatigue, this paper will use the SSO theoretical framework and employ the fsQCA method to explore the antecedent variables and causal condition combinations of privacy fatigue, contributing a new research perspective to promoting user privacy protection.

Stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) model

In 1993, based on the Maslach Professional Burnout Inventory (MBI), Koeske et al. proposed the Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) model. This model, initially applied in psychology, aimed to study the internal psychological processes of how external environmental stressors influence employee fatigue26. Privacy fatigue is a psychological state of fatigue experienced by users in the mobile social media domain and the domain of privacy. Using the SSO theoretical model, it can reveal the psychological process of users facing pressure and causing privacy fatigue. The SSO theoretical framework indicates that stimuli from internal and external environments (Stressor) lead to a series of stress-strain activities (Strain), which consequently result in negative behavioral responses (Outcome). Among them, “stressor” refers to stimuli factors that induce stress and negative emotions in individuals, perceived and interpreted by actors as trouble and potential disruption, such as information overload, technological threats, etc27,28. ; “strain” refers to the physiological or psychological imbalance and negative emotions experienced by individuals under the influence of stressors, such as anxiety, unease, irritability, etc29,30. ; “outcome” refers to the direct behavioral or performance consequences resulting from prolonged exposure to strain, such as fatigue, behavioral disengagement, etc31. It is evident that the psychological process reflected in the “pressure source-stress-outcome” model of the SSO theoretical framework is consistent with the internal logic of privacy fatigue, which is caused by data leaks and the complexity of privacy control as an external pressure source6, and characterized by negative emotions of cynicism and emotional exhaustion, ultimately leading to “behavioral detachment“7. Therefore, the SSO theoretical framework’s “pressure source-stress-outcome” model is applicable in exploring the specific causes of privacy fatigue. Unlike the “Stimulus-Organism-Response” (SOR) model primarily used in the consumer domain, the SSO theoretical model can explain the intrinsic correlation and dynamic development between environmental stimuli and strain outcomes from the perspectives of stress coping and behavioral responses, revealing the underlying mechanisms and hierarchical processes leading to outcome generation by various influencing factors. This theoretical framework aligns well with the research approach of this paper focusing on factors and causal condition combinations related to privacy fatigue.

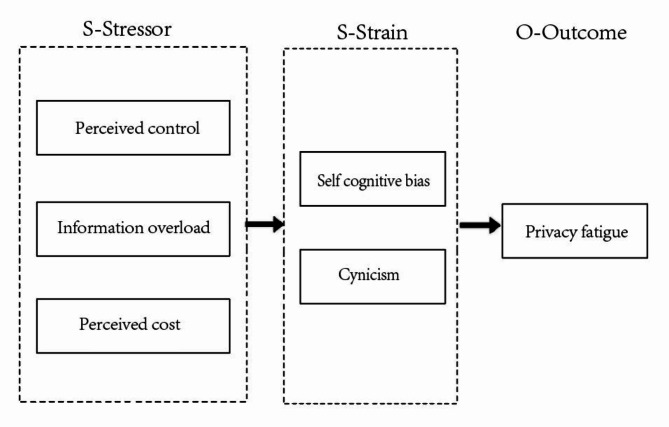

The SSO theoretical model has made progress in studying the relationship between stress and strain outcomes in the context of social media and has shown significant effectiveness in explaining fatigue phenomena. For example; Fu et al.‘s research indicated that information overload and social overload lead individuals to experience social media fatigue, resulting in negative psychological consequences32; Ma et al. (2022) pointed out that stressors and unmet information needs may lead users in short video platforms to experience pressure and negative reactions to recommendation algorithms33. Existing studies indicate that the SSO theoretical framework is a good theoretical framework for explaining the process of various negative emotions among users in the social media domain. Overall, the SSO theory has been repeatedly used to explain the negative impacts of new technology use and has been shown to be applicable in explaining the process of various negative emotions among users in the social media domain. Figure 1 shows the basic framework of the Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) theoretical model adopted in this chapter.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model.

Research design

Research model

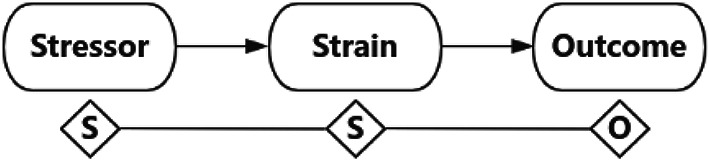

The developed SSO model for privacy fatigue research is relatively vague and does not reflect the complexity of external environmental tasks. Combining previous literature and existing research in the privacy domain, this study constructs a research model based on the SSO theoretical framework, as shown in Fig. 2, treating information overload, perceived control, and perceived cost as stressors, self-cognitive biases, and cynicism as strains under the influence of stressors, and privacy fatigue as the ultimate outcome, constructing an SSO theoretical model of privacy fatigue influencing factors.

Fig. 2.

Stressor-Strain-Outcome theoretical framework applied privacy fatigue.

Stressors

(1) Perceived Control.

Perceived control affects user satisfaction, with higher perceived control leading to a higher expectation of achieving ideal results after handling events34. In the field of information dissemination, perceived control is considered a factor influencing user decisions on social media use, with users making decisions consistent with their perceived control status during social media participation. Wang et al. pointed out that perceived control, as a direct precursor of perceived risk, negatively affects consumers’ willingness to disclose personal information35. In the context of privacy fatigue, perceived control refers to the degree to which users perceive control over the risk of privacy information36. Given the theoretical framework of this study, perceived control is considered a stressor factor that triggers users’ strain responses and leads to the outcome of privacy fatigue.

(2) Information Overload.

Research has found that information overload leads to negative emotions for users in various contexts, such as SNS fatigue in the context of social networking sites37, and job satisfaction reduction in the context of Mobile ICTs38. In the field of social media, numerous studies have shown that information overload can lead to user social media fatigue. Bright (2015) and others pointed out that this is because a large amount of information makes it more difficult for users to understand and increases their mental energy investment in information filtering, leading to fatigue15; based on the SSO perspective, Lee (2016) and others regard perceived overload as a stressor for social media fatigue and found that it leads to the generation of social media user fatigue37. In research on social media privacy, privacy information overload refers to the large amount of information about privacy management that exceeds users’ capacity to receive and process, and when information exceeds the “critical point,” it leads to the emergence of privacy fatigue, manifested as a state of passive fatigue15. Therefore, this study considers information overload as one of the stressors.

(3) Perceived Cost.

Perceived cost in privacy contexts refers to users’ risk assessment of anticipated loss of benefits, often applied in privacy calculus theory. This theory suggests that privacy decisions fundamentally represent the evaluation of perceived benefits and risks of privacy disclosure by software users. When the expected benefits of disclosing personal information outweigh the potential risks, users will exchange risks and benefits and disclose their personal privacy information39. Privacy concerns are often considered the main privacy cost, namely anxiety about others accessing personal information and concerns about privacy information leakage. In addition, perceived risk is also a significant inhibitory factor, as Hajli et al. found that perceived control is negatively correlated with perceived privacy risk and information sharing attitudes40. Perceived cost is considered a reliable predictor of protective and cautious privacy intentions and behaviors. Therefore, this study includes perceived cost as a stressor in the research model.

Strains

(1) Self-Cognitive Biases.

Users, constrained by the use of (inappropriate) cognitive heuristics that people apply to deal with data limitations, information processing limitations, or a lack of expertise, may develop cognitive biases in estimating the risks of privacy disclosure41. Users’ cognitive biases often manifest as: ① Optimistic bias, which reflects people’s optimistic bias due to not having experienced negative risks firsthand. For example, a study in South Korea found that experiencing privacy infringement affects people’s optimism; those who have not experienced infringement are more optimistic and therefore more inclined to adopt privacy protection behaviors42. ② Overconfidence bias, where users have an overconfidence in their ability to cope with privacy disclosure or infringement risks. Research found that among users who rated their privacy protection technology assessment highly, less than a quarter actually understood how to defend against privacy risks through technical means43. ③ Affective bias, where perceived benefits prompt people to generate positive emotions, leading them to overlook risks when making behavioral decisions, resulting in the emergence of the privacy paradox. Studies have shown that people are easily influenced by their momentary emotional states when conducting privacy assessments44. ④ Hyperbolic discounting, where users’ perception and evaluation of short-term and long-term benefits are influenced by time factors. Users tend to underestimate long-term benefits and losses because they are in the future and are more inclined to obtain immediate convenience45. Since users’ cognitive biases are influenced by environmental factors and also act on privacy fatigue, cognitive biases are considered burdens caused by stressors.

(2) Cynicism:

Cynicism typically refers to a negative, pessimistic attitude or belief toward an object, accompanied by frustration, hopelessness, and disillusionment. It mainly develops from unmet expectations. In the field of information management, Hoffmann et al. first proposed the concept of privacy cynicism in 2016, which has gradually gained widespread recognition and extensive research in the privacy domain46. Choi et al. pointed out that cynicism and emotional exhaustion constitute core components of privacy fatigue, further applying cynicism to the explanation of user privacy behavior and the process of privacy fatigue. Other scholars have also found that cynicism also functions as a coping mechanism and is an important factor in explaining privacy fatigue and privacy behavior. When individuals are highly privacy cynical, they might feel that efforts to cope with risks are futile or unsuccessful, thus being less motivated to scrutinize the pros and cons of data disclosure and putting less effort into making privacy decisions, which leads to more privacy disclosure behavior, detrimental to users’ privacy protection25. Previous studies have shown that perceived control, information disclosure, and perceived cost can influence cynicism. For example, Iris van Ooijen pointed out that, under the mediating role of cynicism, the negative relationship between information overload and response costs and privacy protection behavior is weaker for highly cynical individuals25. In this research model, cynicism, as a coping mechanism for stressors, exists as a strain and ultimately leads to the outcome of privacy fatigue.

Research methodology

The QCA method, as a “case-oriented” approach used to address the interdependence of configurational phenomena and the complexity of causality, was first proposed by Ragin in 1987.47 It is divided into two methods: Crisp-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (csQCA) and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA). One of the most popular methods used in current research is fsQCA, which is different from traditional quantitative analysis. Instead of focusing on the individual effects of multiple factors on a complex matter, fsQCA pays attention to the combined effects of these factors in producing a specific outcome. Therefore, it is more suitable for analyzing the conditions that lead to various outcomes when multiple factors are involved and has gradually been applied in the fields of social media and privacy48. In the privacy domain, fsQCA has contributed to the elucidation of processes such as privacy protection behavior and privacy disclosure behavior from a configurational perspective. However, no study has yet applied fsQCA to the analysis of antecedent variables of privacy fatigue. Moreover, due to the heterogeneity and complexity of privacy fatigue, its occurrence may be the result of the interaction and combination of these motives. Therefore, after exploring the influencing factors and possible internal connections of privacy fatigue based on the SSO theory, this study further chooses to use fsQCA, a research method that connects qualitative and quantitative strategies, to break through the limitations of traditional regression analysis and qualitative research methods, which are mainly suitable for exploring the “net effects” of individual factors, and to study how a combination of variables causes a particular outcome .

Questionnaire design

This study adopts a questionnaire survey method, and the measurement indicators of the questionnaire are derived from existing domestic and foreign literature, with slight modifications to fit the actual situation of mobile social media in China. The questionnaire design is mainly divided into two parts. The first part includes demographic variables, such as the respondent’s gender, age, education level, frequency of using WeChat, etc. The second part focuses on the investigation of factors related to the model, including Perceived control, Information overload, Perceived cost, Self-cognitive bias, Cynicism, and other 5 variables. The questionnaire uses a Likert five-point scale, ranging from “1” to “5,” where “1” represents “strongly disagree” and “5” represents “strongly agree”. Specific measurement items are shown in Table 1. This study collects data samples from users on the mobile social media platform WeChat in China.

Table 1.

Questionnaire measure.

| latent variable | Measured item | Question item | Document source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived control | Pcon1 | When social media requires me to agree to a privacy agreement in order to use it, I have to agree to a privacy agreement. |

Milne et al.49 |

| Pcon2 | I think it’s easy for me to take steps to protect my private information. | ||

| Information overload | IO1 | When my private information was disclosed, I was able to tell which social media platform had done it. |

Xu et al.50 |

| IO2 | There is too much information about privacy on social media for me to handle | ||

| Perceived cost | Pcost1 | When the security of personal privacy information is threatened, I think it takes a lot of energy to take action to protect it | |

| Pcost2 | When the disclose of personal privacy information threatens the interests of friends around, I think it is necessary to take protective actions | ||

| Pcost3 | When the disclosure of personal privacy information threatens economic interests, I think it is necessary to take protective action | ||

| Self- cognitive bias | SCB1 | I think privacy violations are less likely to happen to me |

Cho et al.51 |

| SCB2 | I don’t think my private information is valuable enough to warrant a privacy violation | ||

| Cynicism | CYN1 | I became skeptical about the importance of privacy issues on social networks | Schaufeli et al.52 |

| CYN2 | When it comes to adopting privacy measures in a social network environment (such as signing a privacy agreement, setting up a circle of friends to be visible, etc.), I get bored | ||

| CYN3 | Privacy disclose happen so often that I don’t bother to take any further steps | ||

| Privacy fatigue | PF1 | If in the process of using online services, I need to sign a privacy statement agreement, I will not read it and will directly choose to agree | Krasnova et al.53 |

| PF2 | If the privacy statement protocol provided by the online service provider is complicated, I will give up understanding and simply choose to agree | ||

| PF3 | I don’t want to think about responding if personal information I have provided to an online service provider is disclosed |

Data collection

To verify and check causal relationships, the study used online questionnaire to collect relevant data. The survey was administered by applicable guidelines and regulations and was reviewed and approved by the School of History and Culture at Henan University. Currently, the social media platform with the highest number of daily active users in China is WeChat. Therefore, this chapter selects WeChat users as the data collection sample. The main method of collecting questionnaires is through snowball sampling, where friends, relatives, etc., are invited to participate in the survey, and then the respondents are asked to invite their acquaintances to participate in the survey. Participants voluntarily click on the link to fill out the questionnaire. Before filing out the questionnaire, they have been informed that “submitting answers” is considered informed consent and that the data they met would be used only for this study, and anonymity was guaranteed. Participants can exit at any time during the questionnaire filling process. A total of 1301 questionnaires were collected in this study. After excluding invalid questionnaires with less than 60 s of completion time, more than 1000 s of completion time, and identical answers to all items, 1134 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective rate of 87.1%. The demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2..

Table 2.

Sample demographic information

| Items | Choices | Frequency | Percent% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 565 | 49.83% |

| female | 569 | 50.17% | |

| Age | <20 | 93 | 8.19% |

| ≥20 and<30 | 391 | 34.47% | |

| ≥30 and<40 | 580 | 51.19% | |

| ≥40 and<50 | 58 | 5.12% | |

| ≥50 | 12 | 1.03% | |

| Highest education level | Senior high school and below | 225 | 19.80% |

| Undergraduate and junior college | 414 | 36.52% | |

| Postgraduates | 375 | 33.1% | |

| Doctoral students | 120 | 10.58% | |

| Average daily time spent on Wechat usage | <1h | 55 | 4.85% |

| ≥1h and<3h | 221 | 19.49% | |

| ≥3h and<5h | 371 | 32.72% | |

| ≥5h and<8h | 282 | 24.87% | |

| ≥8h | 205 | 18.08% | |

| Number of WeChat friends | <100 | 139 | 12.29% |

| ≥100 and<300 | 550 | 48.47% | |

| ≥300 and<600 | 290 | 25.60% | |

| ≥600 and<1000 | 109 | 9.56% | |

| ≥1000 | 46 | 4.08% |

Directed comparative analysis results of privacy fatigue generation pathways

Calibration of conditional and outcome variables

For fsQCA analysis, it is necessary to calibrate the data first, converting the absolute values of conditions and outcomes into corresponding fuzzy set memberships, with thresholds set at “fully membership,” “cross-over point,” and “full nonmembership,” three levels. After calibration, the values of the set memberships range between 0 and 154. To ensure the objectivity of calibration, this study, based on the cases themselves, combined with thematic literature from other qualitative comparative analysis methods, chose the direct calibration method provided by Ragin54, with the 95%, 50%, and 5% quantiles of each continuous variable set as anchor points55. After calibration processing, the closer the variable value is to 1, the higher its membership in the relevant set; conversely, the closer the variable value is to 0, the lower its membership in the relevant set. Specific assignment details can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Calibration anchors for each variable.

| Variable | Anchors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully membership | Cross-over point | Full nonmembership | |||

| outcome variable |

Privacy fatigue |

4 | 2.666667 | 1 | |

| conditional variables | Perceived control | 4.5 | 3 | 2 | |

|

Information overload |

4 | 3 | 2 | ||

|

Perceived cost |

5 | 4 | 2.333333 | ||

|

Self- Cognitive bias |

4 | 2.5 | 1 | ||

| Cynicism | 4 | 3 | 1.666667 | ||

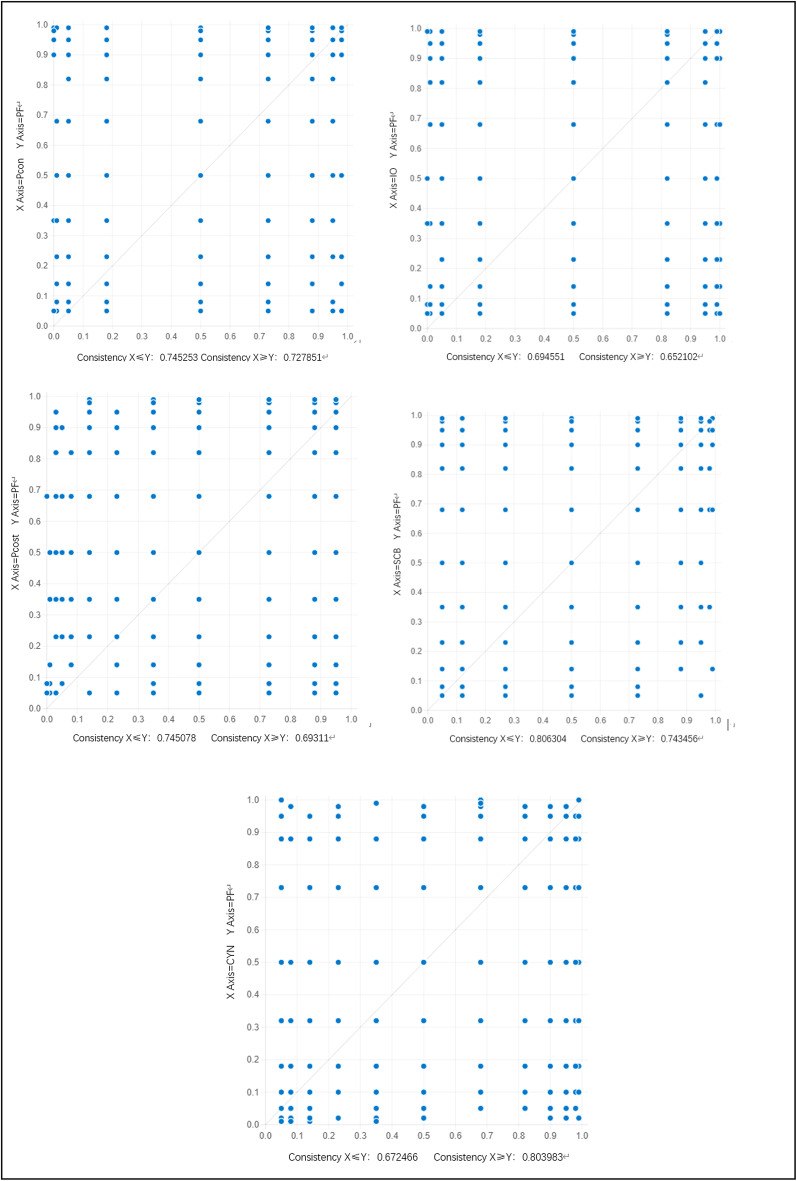

After data calibration, this study conducted a necessary condition analysis of single variables, and the results are shown in Table 4. Through data analysis, it was found that when the outcome variable is privacy fatigue and the conditional variables are perceived control, information overload, perceived cost, self-cognitive bias, and cynicism, the consistency level of each single variable did not exceed 0.954, indicating the absence of necessary conditions. Therefore, this study needs to conduct sufficiency analysis on combinations of multiple conditional variables.

Table 4.

Necessary conditions for privacy fatigue.

| Conditions | Consistency | Coverage |

|---|---|---|

| Pcon | 0.727851 | 0.745253 |

| ~Pcon | 0.561027 | 0.626126 |

| IO | 0.652102 | 0.694551 |

| ~IO | 0.637090 | 0.682258 |

| Pcost | 0.693110 | 0.745078 |

| ~Pcost | 0.609545 | 0.646780 |

| SCB | 0.743456 | 0.806304 |

| ~SCB | 0.580531 | 0.610684 |

| CYN | 0.852087 | 0.732313 |

| ~CYN | 0.475718 | 0.670852 |

Note: ~ means the operational logic of “non”.

Configuration solution

When conducting fsQCA analysis, P.C. Fiss suggests that when the sample size exceeds 150, the case frequency threshold should be set at 356. Ragin recommends setting the consistency threshold at 0.75, but considering the actual circumstances of this study, the consistency threshold is set at 0.85, with a case frequency threshold of 8, and cases with pri consistency below 0.65 are manually adjusted to 057,58. The results of fsQCA analysis yield three different levels of simplification: complex solution, intermediate solution, and parsimonious solution. It is widely recognized in academia that the discussion of analysis results should primarily focus on intermediate solutions. By using XY Plot in fsQCA, the presence or absence of conditional variables can be determined. This study constructs XY Plot for each antecedent variable and the outcome variable, showing that all conditional variables are either present or absent conditions, as shown in Table 5. This implies that complex solutions are equivalent to intermediate solutions. Therefore, this paper reports intermediate solutions supplemented by parsimonious solutions56. In this study, Fiss’s classification56 is used for conditional classification. Different conditions are defined for different situations, where core conditions appear in parsimonious solutions, and all conditions appearing in intermediate solutions but excluded from parsimonious solutions are referred to as secondary conditions, as shown in the empirical results listed in Table 6.

Table 5.

Plots for predictive validity.

Table 6.

Intermediate solutions.

| Configuration | Raw coverage | Unique coverage | Consistency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Perceived control*Perceived cost* Self-cognitive bias |

0.472265 | 0.026835 | 0.909809 |

| 2 | Perceived control*Self-cognitive bias* Cynicism | 0.545123 | 0.0474937 | 0.895503 |

| ~Information overload *~Perceived cost *Self- cognitive bias*Cynicism | 0.396912 | 0.0383293 | 0.902723 | |

| Perceived control*~Information overload* Perceived cost*Cynicism | 0.40426 | 0.0534232 | 0.901293 | |

| 3 | Information overload* Perceived cost*Self- cognitive bia*Cynicism | 0.433953 | 0.0265715 | 0.91756 |

| Solution Coverage, SCV | 0.714905 | |||

| (Solution Consistency, SCS) | 0.850429 | |||

Note: * represents the logical operator “and” in Boolean arithmetic, indicating that the connected conditions exist at the same time.

In the expression of configuration diagrams, core conditions and secondary conditions are represented by large circles and small circles, respectively, while conditions with no impact are shown as blank spaces. From the results of Table 7, the overall coverage of the model is 0.715, meaning that the results explain 71.5% of the pathways of privacy disclosure. Moreover, at the consistency level, the values of the five solutions all reach 0.85, indicating that the combination of the above factors can be considered as consistent and sufficient conditions for privacy disclosure.

Table 7.

Distribution of configurations.

| Variable | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived control | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Information overload | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ||

| Perceived cost | ● | ⊗ | ● | ● | |

| Self-cognitive bias | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Cynicism | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Solution Coverage, SCV = 0.714905 | |||||

| Solution Consistency, SCS= 0.850429 | |||||

Path analysis

Based on the aforementioned configuration solutions, three paths of privacy fatigue phenomena can be summarized (S1-S5).

(1) Rational Model-Driven: S1 path: Perceived control*Perceived cost* Self-cognitive bias, with an original coverage of 0.472, indicating that approximately 47.2% of cases can be explained by this combination path. This configuration suggests that when users perceive satisfaction in perceived control, perceived cost, and self-cognitive bias, the probability of experiencing privacy fatigue increases. Among them, perceived cost and self-cognitive bias play the most critical roles. S5 path: Information overload* Perceived cost*Self-cognitive bia*Cynicism, with an original coverage of 0.4339, indicating that approximately 43.39% of cases can be explained by this combination path. In this path, perceived cost and self-cognitive bias also play the most critical roles. According to the Privacy calculus theory, perceived cost is a manifestation of rational calculation of behavioral benefits, which indicates that individuals decide to disclose personal information when potential gains surpass expected losses. In addition, behavioral economics and existing research in the privacy field have shown that human decision-making is affected by cognitive biases. This cognitive bias is a rational judgment of the probability of risk occurrence. Due to this limited rationality, users may underestimate potential privacy risks, affecting their calculation of risks and benefits. This pattern conforms to the Privacy calculus theory, where users, under the influence of stressors such as perceived cost, engage in rational calculations, and the stressor factor of self-cognitive bias under limited rationality further facilitates the emergence of privacy fatigue.

(2) Burden Model-Driven: S2 path: Perceived control*Self-cognitive bias* Cynicism, with an original coverage of 0.545, indicating that approximately 54.5% of cases can be explained by this combination path. This configuration suggests that when users perceive satisfaction in perceived control, self-cognitive bias, and cynicism, they are more likely to experience privacy fatigue, with self-cognitive bias and cynicism playing the most critical roles. S3 path: ~Information overload *~Perceived cost *Self-cognitive bias*Cynicism, with an original coverage of 0.397, indicating that approximately 39.7% of cases can be explained by this combination path, where self-cognitive bias and cynicism still play the most critical roles. In previous studies, scholars believed that users’ disclosure behavior is driven by bounded rationality, meaning that due to limitations in users’ knowledge, their decisions are influenced by cognitive biases. These cognitive biases lead to users’ incorrect estimation of the risk level of the environment or their ability to cope with risks42. The pressure caused by these error estimations, if accompanied by feelings of uselessness, powerlessness, and mistrust toward the handling of personal data, rendering privacy protection subjectively futile, users are more likely to experience privacy fatigue. This pattern conforms to the assumptions of the SSO theory model, where users’ burden responses induced by stressors facilitate the emergence of privacy fatigue.

(3) Emotion Model-Driven: S4 path: Perceived control*~Information overload* Perceived cost*Cynicism, with an original coverage of 0.404, indicating that approximately 40.4% of cases can be explained by this combination path. This configuration suggests that when users’ information overload does not occur and the elements of perceived control, perceived cost, and cynicism are simultaneously satisfied, users are more likely to experience privacy fatigue. Among them, cynicism plays the most critical role. Previous research has shown that an attitude of cynicism negatively predicts users’ privacy decisions and intentions to disclose privacy, and is an important reason leading to the decoupling of privacy concern and privacy protection behaviors13,59. The emotion model-driven pattern confirms these studies. Scholars have also found that when perceived costs exceed users’ tolerance levels, it triggers negative fatigue emotions in privacy-cynical individuals. Users may adopt an attitude of cynicism toward privacy protection behavior25, even if they feel that the time and effort required to perform behaviors aimed at protecting their privacy are reasonable. Similarly, scholars also argue that privacy cynicism negatively moderates the relationships between self-efficacy and response efficacy and privacy protection behavior. Therefore, when users’ cynicism is strongly pronounced, this affective coping mechanism plays an important role, leading to the emergence of privacy fatigue along with the two stressor factors of perceived control and perceived cost.

Robustness test of fsQCA

Methods for robustness testing include adjusting calibration thresholds, adjusting case frequency thresholds, adjusting consistency thresholds, and increasing or decreasing cases, among others. In this study, robustness testing was conducted by adjusting the case frequency threshold, setting it to 9, while keeping other thresholds unchanged for configurational analysis. After adjustment, the solution scenarios are shown in Table 8. By comparison, it was found that except for cynicism becoming a marginal condition instead of a core condition in Path 4, and ~ Information overload becoming a core condition while self-cognitive bias shifted from a core to a marginal condition in Path 1, the existing configurations were generally consistent with previous solutions. The coverage of solutions slightly decreased, while consistency slightly increased after adjustment. The test results showed a clear subset relationship with the previous results, and the obtained solutions had a consistent internal explanatory mechanism with the previous ones60. Based on this, it can be considered that this study is robust.

Table 8.

The result of robustness testing.

| Variable | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived control | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Information overload | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | |

| Perceived cost | ● | ⊗ | ● | ● | |

| Self-cognitive bias | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Cynicism | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Solution Coverage, SCV = 0.704683 | |||||

| Solution Consistency, SCS = 0.854639 | |||||

Discussion of the results

In the privacy field, existing studies have emphasized the universality of privacy fatigue and its importance in promoting privacy protection, explaining privacy paradox, and so on8. However, there is a lack of exploration into the antecedents and processes of privacy fatigue. To fill this research gap, this study empirically examines the influencing factors and pathways of privacy fatigue, contributing a new research perspective to explain the phenomenon of privacy fatigue. Based on the SSO theoretical model, this paper analyzed the causal pathways of privacy fatigue by introducing the fsQCA method. This research found that Perceived control, Information overload, and Perceived cost are stressor factors in the process of privacy fatigue, while Self-cognitive bias and Cynicism are strain factors. Building on this, according to fsQCA analysis, three pathways of privacy fatigue were identified. Firstly, the burden model emphasizes that when users react with a burden response due to the influence of stressors, the phenomenon of privacy fatigue is more likely to be induced. Secondly, there are rational and emotional models. The rational model emphasizes that when users make rational calculations under the influence of stressors such as perceived cost and exhibit limited rational burden responses due to self-cognitive biases, privacy fatigue is more likely to be induced. This is consistent with existing research in the privacy domain and the results of Privacy calculus theory research. This study further supplements the emotional model, emphasizing the important role of users’ psychological processes and emotions in the process of privacy fatigue, especially the crucial role played by cynicism, which is consistent with previous research, indicating that cynicism also functions as a coping mechanism4,25.

Theoretical implications

This paper provides important theoretical insights for a better understanding of privacy behaviors among social media users. Firstly, privacy fatigue has been identified as a key factor influencing user privacy behavior, yet research on privacy fatigue is scarce, especially regarding its formation mechanism. This paper fills this gap by incorporating Perceived control, Information overload, Perceived cost, Self-cognitive bias, and Cynicism into the factor model based on the SSO theoretical model. Secondly, through research, this paper identifies three causal pathways of privacy fatigue composed of the aforementioned five factors: the rational model, the burden model, and the emotional model. This conclusion offers new explanatory perspectives for interpreting the phenomenon of privacy fatigue in the digital era. Lastly, this paper introduces the fsQCA method into the study of privacy fatigue among social media users for the first time. Due to the complexity of privacy fatigue dynamics, where the causal factors interact with each other, traditional regression perspectives are insufficient QCA, as a representative method of configuration theory, is suitable for analyzing the combined effects of various factors on specific behavioral outcomes, thereby providing interpretations of the equivalent pathways of privacy fatigue. Therefore, the qualitative comparative analysis of privacy fatigue phenomena using fsQCA in this chapter is highly applicable and innovative.

Practical implications

In practice, the conclusions of this study contribute to enhancing users’ awareness of privacy fatigue and promoting platform service providers to optimize privacy protection measures. Firstly, users’ sense of privacy fatigue will directly lead to disengagement from privacy protection behaviors and increase dissatisfaction with service providers (Zhang et al., 2016). This necessitates platform service providers to optimize means of acquiring user privacy and reduce the difficulty for users to understand privacy acquisition policies. Simultaneously, transparency in user privacy management needs to be enhanced to empower users with better control over the flow of their personal data. Secondly, the SSO model suggests that “burden” often serves as a key variable leading to privacy fatigue among social media users. Therefore, platform service providers should pay more attention to users’ negative emotions and cognitive responses, establish more secure and reliable mechanisms for protecting personal information, and alleviate users’ concerns and feelings of helplessness regarding privacy disclose. Lastly, the research results indicate that five paths with different combinations of factors will lead to privacy fatigue among social media users. This may provide a new approach for platform service providers in formulating privacy acquisition and protection policies: using personalized measures to prevent users from experiencing privacy fatigue and further disengaging from privacy protection behaviors.

Limitations and future research

Limitations in the current study should be acknowledged. Firstly, although this paper analyzes the pathways of privacy fatigue among social media users, it is limited to the WeChat platform, which primarily focuses on private social interactions. Emerging open social platforms, such as those centered around real-time live streaming or short video sharing, have different privacy acquisition policies. Therefore, attention should still be paid to the behavioral differences of users across multiple platforms under the phenomenon of privacy fatigue. Hence, exploring the dissimilarities between new modes of mobile social media users and traditional ones regarding privacy fatigue could be a future research direction. Secondly, in this study attempt, the differentiation of privacy fatigue pathways among users of different age groups is somewhat limited. Therefore, specific pathway differences in the occurrence of privacy fatigue among user groups with different personality characteristics may be a future research direction. Additionally, this study relies on Likert scale-form questionnaires for limited exploration of users’ subjective information. Subsequent research can utilize in-depth interviews, repeated surveys, etc., to check the pathways of privacy fatigue in this study and explore other factors that may affect privacy fatigue.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Wj.Wang designed the study. Qk. Wu was responsible for data collection and and analysis. Dq. Li helped with manuscript preparation. Xl.Tian directed the research, supported data analysis, and facilitated the writing of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is one of the achievements of Henan Soft Science Project (Project No. 202400410595) in 2024.One of the achievements of Henan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Annual Project in 2023 (Project No. : 2023CZH014).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

The survey was administered by applicable guidelines and regulations and was reviewed and approved by the School of History and Culture at Henan University. Before filing out the questionnaire, they have been informed that “submitting answers” is considered informed consent. The anonymity and confidentiality of the participants were guaranteed, and participation was completely voluntary. Therefore, all subjects who submitted the questionnaire have obtained informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tencent News. 538 million weibo user data breaches, take in everything in a glance of privacy [EB/OL]. [2022-01-20]. https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20200323AONM9900

- 2.Tencent Technology. 553 million Facebook users’ personal information was leaked [EB / OL]. [2022-01-20]. https://xw.qq.com/partner/vivoscreen/20210404A014E0/20210404A014E000? vivoredmark = 1& vivo RcdMark = 1.

- 3.Baruh, L. Secinti,E.,Cemalcılar,Z. Online privacy concerns and privacy management: a Meta-Analytical Review. J. Communication. 67, 26–53 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meier, Y. & Krämer, N. C. A longitudinal examination of internet users’ privacy protection behaviors in relation to their perceived collective value of privacy and individual privacy concerns. New. Media & Society,1–20(2023).

- 5.Xu, H., inev, T., Smith, J. & Hart, P. Information privacy concerns: linking individual perceptions with institutional privacy assurances. J. Association Inform. Syst.12 (12), 798–824 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu, M. et al. Privacy paradox in mHealth applications: an integrated elaboration likelihood model incorporating privacy calculus and privacy fatigue. Telematics Inform.61, 101601 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi, H., Park, J. & Jung, Y. The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav.81 (4), 42–51 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwon, J. & Johnson, M. E. The Market Effect of Healthcare Security: do patients care about data breaches? Workshop Econ. Inform. Secur. 06,n. pag(2015).

- 9.Zhang, X., Tian, X. & Han, Y. Influence of Privacy Fatigue of Social Media Users on their privacy Protection Disengagement Behaviour - A PSM based analysis. J. Integr. Des. Process Sci.25, 78–92 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin, C. P. Recognition of a consumer right. J. Public. Policy Mark.10 (1), 149–166 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hopstaken, J. F., van der Linden, D., Bakker, A. B. & Kompier, M. A. A multifaceted investigation of the link between mental fatigue and task disengagement. Psychophysiology52 (3), 305–315 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A. & Calvert, S. L. College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol.30 (3), 227–238 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hargittai, E. & Marwick, A. E. Really do? Explaining the privacy Paradox with Online apathy. Int. J. Communication. 10, 1–21 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, W. & Lee, K. H. Sharing,liking,commenting,and distressed?The pathway between Facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychology Behav. Social Netw.16 (10), 728–734 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bright, L. F. & Kleiser, S. B. Grau,S.L.Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav.44, 148–155 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bucher, E. Fieseler,C.,Suphan,A.The stress potential of social media in the workplace. Inform. Communication Soc.16 (10), 1639–1667 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang, Y., Liu, Y. & Li, W. Peng,L.,Yuan,C. A study of the influencing factors of mobile social media fatigue behavior based on the grounded theory. Inform. Discovery Delivery. 48 (2), 91–102 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cramer, E. M. & Song, H. Drent,A.M.Social comparison on Facebook: motivation, affective consequences, self-esteem, and Facebook fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav.64, 739–746 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao, W., Liu, Z., Guo, Q. & Li, X. The dark side of ubiquitous connectivity in smartphone-based SNS: an integrated model from information perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav.84, 185–193 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhir, A. & Kaur, P. Chen,S.,Pallesen,S.Antecedents and consequences of social media fatigue.International Journal of Information Management 48,193–202 (2019).

- 21.Sasaki.,Yuichi. Unfriend or ignore tweets? A time series analysis on Japanese Twitter users suffering from information overload. Comput. Hum. Behav.6, 914–922 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun.,Yong, Q. et al. Understanding users’ switching behavior of mobile instant messaging applications: an empirical study from the perspective of push-pull-mooring framework. Comput. Hum. Behav.75, 727–738 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brightl.;Limh. ;Lognak.Should I post or ghost? Examining how privacy concerns impact social media engagement in US consumers. Psychol. Mark.38 (10), 1712–1722 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang, S., Zhao, L., Lu, Y. & Yang, J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behaviour in social network services. Inf. Manag.53 (7), 904–914 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Ooijen, I., Segijn, C. M. & Opree, S. J. Privacy cynicism and its role in privacy decision-making. Communication Res.02, 1–32 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koeske, G. F. & Koeske, R. D. A preliminary test of a stress-strain-outcome model for reconceptualizing the Burnout Phenomenon. J. Social Service Res.17, 107–135 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye, D. Y., Cho, D., Chen, J. & Jia, Z. Empirical investigation of the impact of overload on the discontinuous usage intentions of short video users: a stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Online Inf. Rev.47, 697–713 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasim, N. M., Fauzi, M. A., Yusuf, M. F. & Wider, W. The Effect of WhatsApp usage on employee innovative performance at the workplace: perspective from the stressor–strain–outcome model. Behav. Sci.12 (11), 456 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teng, L., Liu, D. & Luo, J. Explicating user negative behavior toward social media: an exploratory examination based on stressor–strain–outcome model. Cogn. Technol. Work. 24, 183–194 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu, L., Shi, C. & Cao, X. Understanding the Effect of Social Media Overload on Academic Performance: A Stressor-Strain-Outcome Perspective. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, (2019).

- 31.Cao, X., Masood, A. & Ali, A. Excessive use of mobile social networking sites and poor academic performance: antecedents and consequences from stressor-strain-outcome perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav.85, 163–174 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu, S., Li, H., Liu, Y., Pirkkalainen, H. & Salo, M. Social media overload, exhaustion, and use discontinuance: examining the effects of information overload, system feature overload, and social overload. Inf. Process. Manag.57 (6), 102307 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma, X., Sun, Y., Guo, X., Lai, K. & Vogel, D. Understanding users’ negative responses to recommendation algorithms in short-video platforms: a perspective based on the stressor-strain-outcome (SSO) framework. Electron. Markets. 32, 41–58 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, J. C. Of medical service users’ dissatisfaction: a Perceived Control Perspective. Int. J. Manage. Mark. Res.5, 53–63 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, T. & Duong, T. D. Chen,C.C.Intention to disclose personal information via mobile applications: a privacy calculus perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag.36 (4), 531–542 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartol, J., Prevodnik, K., Vehovar, V. & Petrovčič, A. The roles of perceived privacy control, internet privacy concerns and internet skills in the direct and indirect internet uses of older adults: conceptual integration and empirical testing of a theoretical model. New. Media Soc.09 (n), pag (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee, A. R., Son, S. M. & Kim, K. K. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: a stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav.55, 51–61 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin, P., Ou, C. X., Davison, R. M. & Wu, J. Coping with mobile technology overload in the workplace. Internet Res.28, 1189–1212 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laufer, R. S. & Wolfe, M. Privacy as a Concept and a Social Issue: a Multidimensional Developmental Theory. J. Soc. Issues. 33, 22–42 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hajli, N. Lin,X.Exploring the Security of Information Sharing on Social Networking Sites: the role of Perceived Control of Information. J. Bus. Ethics. 133, 111–123 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korteling, J. E. (Hans),Toet, Alexander. Cognitive biases section published in the encyclopedia of behavioral neuroscience. Elsevier Sci., 610–619 (2022).

- 42.Baek, Y. M., Kim, E. & Bae, Y. My privacy is okay, but theirs is endangered: why comparative optimism matters in online privacy concerns. Comput. Hum. Behav.31, 48–56 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jensen, C., Potts, C. M. & Jensen, C. Privacy practices of internet users: self-reports versus observed behavior. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud.63, 203–227 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kehr, F., Kowatsch, T. & Wentzel, D. Fleisch,E.Blissfully ignorant: the effects of general privacy concerns, general institutional trust, and affect in the privacy calculus. Inform. Syst. J.25, 607–635 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson, D. W. & Valacich, J. S. Unpacking the Privacy Paradox: Irrational Decision-Making within the Privacy Calculus. International Conference on Interaction Sciences 41,114–125 (2012).

- 46.Hoffmann, C. P., Lutz, C. & Ranzini, G. Privacy cynicism: a new approach to the privacy paradox. J. Psychosocial Res.10 (4), 7 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ragin, C. C. The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies.Berkeley: University of California Press. (1989).

- 48.Tang, Y. & Wang, L. An Empirical Study of Platform Enterprises’ privacy Protection behaviors based on fsQCA. Secur. Communication Networks. 9517769, 1–12 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milne, G. R., Labrecque, L. I. & Cromer, C. T. Toward an understanding of the Online Consumer’s Risky Behavior and Protection practices. J. Consum. Aff.43, 449–473 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu, H., Gupta, S., Rosson, M. B. & Carroll, J. M. Measuring Mobile Users’ Concerns for Information Privacy. International Conference on Interaction Sciences,1–10 (2012).

- 51.Cho, H., Lee, J. & Chung, S. Optimistic bias about online privacy risks: testing the moderating effects of perceived controllability and prior experience. Comput. Hum. Behav.26, 987–995 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schaufeli, W. B. & Leiter, M. P. Maslach,C.,Jackson,S.E.The Maslach Burnout Inventory–General Survey. (1996).

- 53.Krasnova, H. & Veltri, N. F. Günther,O. Self-disclosure and privacy Calculus on Social networking sites: the role of culture. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng.4 (3), 127–135 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ragin, C. C. Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. Soc. Forces. 88 (4), 1936–1938 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie, X. & Tsai, N. The effects of negative information-related incidents on social media discontinuance intention: evidence from SEM and fsQCA. Telematics Inform.56, 101503 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fiss, P. C. Building better causal theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J.54 (2), 393–420 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ragin, C. C.Set relations in social research: evaluating their consistency and coverage. Political Anal.14 (3), 291–310 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greckhamer, T. CEO compensation in relation to worker compensation across countries: the configurational impact of country-level institutions. Strateg. Manag. J.37 (4), 793–815 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian, X., Chen, L. & Zhang, X. The role of privacy fatigue in privacy Paradox: a PSM and Heterogeneity Analysis. Appl. Sci.12, 9702 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eppler, M. J. & Mengis, J. The concept of information overload: a review of literature from organization science,accounting, marketing, mis, and related disciplines. Inform. Soc.20 (5), 325–344 (2004). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.