Abstract

Covalent organic frameworks are a novel class of porous polymers, notable for their crystalline structure, intricate frameworks, defined pore sizes, and capacity for structural design, synthetic control, and functional customization. This paper provides a comprehensive analysis of graph entropies and hybrid topological descriptors, derived from geometric, harmonic, and Zagreb indices. These descriptors are applied to study two variations of Marta covalent organic frameworks based on contorted hexabenzocoronenes. We also conduct a comparative analysis using scaled entropies, offering refined tools for assessing the intrinsic topologies of these networks. Additionally, these hybrid descriptors are used to develop statistical models for predicting graph energy in higher-dimensional Marta-COFs.

Keywords: hexabenzocoronenes, covalent organic frameworks, vertex degree indices, entropies, graph energy

1 Introduction

Reticular chemistry connects organic building blocks through strong covalent bonds, which have the capacity to regulate the pore sizes of frameworks by preserving their fundamental topology and varying the lengths of organic linkers, thus paving the way for the emergence of multiple classes of crystalline porous materials (Yaghi, 2016; Yaghi, 2019). Reticulated materials can be classified as metal organic frameworks (MOFs), created by the combination of organic linkers and metal atoms, and covalent organic frameworks (COFs), composed only of organic linkers (Gropp et al., 2020). COFs have drawn particular attention from researchers due to their regular pattern of organic building blocks, which allows for the creation of crystalline structures with extensive surface areas, stability, and customizable pores (El-Kaderi et al., 2007). COFs possess potential applicatiions in separation (Fan et al., 2023), luminescence (Haug et al., 2020), biomedicine (Shi et al., 2023), energy conversion (Sun et al., 2023), environmental remediation (Hou et al., 2023), seawater desalination (Jrad et al., 2023), photocatalysis (Gong et al., 2023), and electrocatalysis (Zhang et al., 2021). The COFs have predetermined structures based on their building blocks, allowing for highly ordered geometries (Huang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2014). Their covalently crystalline structure gives them advantages over other porous materials such as molecular sieves, MOFs and zeolites (Yang et al., 2019; Jiao et al., 2019; Algieri and Drioli, 2021).

Covalent bonds within COFs can arise from a diverse range of functional groups. The methods for forming these bonds can be broadly classified into several categories, including boroxine-linked, boronate ester-linked, triazine-linked, imine-linked, hydrazone-linked, -ketoenamine-linked, azine-linked, imide-linked, carbon-carbon linked, and others (Wang et al., 2020; Geng et al., 2020). Boronate ester based COFs represent a category of crystalline, porous polymers characterized by layer-stacked structures, which are formed through reversible covalent interactions between boronic acid and catechol. The initial reported methods for COF formation involved the self-condensation of boronic acids into boroxine rings and the co-condensation of boronic acids with catechols to form boronic esters. This bond type stands out as one of the most frequently observed COF formation, with COF-5 being an early example falling within this category (Cot̂é et al., 2005; Li et al., 2018). Since then the varieties of COFs featuring boron, have gained significant attention primarily due to their exceptional thermal stability (Kuhn et al., 2008).

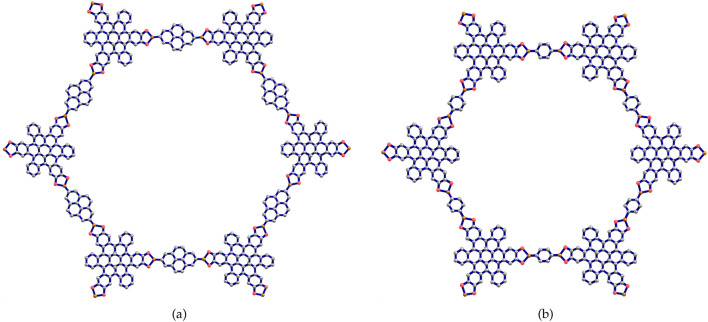

The COFs considered in this study are made up of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) with contorted hexabenzocoronene (c-HBC) serving as the core component for constructing the two Marta-COFs. The c-HBC adopts a doubly-concave structure, which sets it apart from the planar hexabenzocoronene. Its formation occurs when the aromatic core of HBC is distorted away from planarity due to steric congestion in its proximal carbon atoms. Structurally, c-HBC is the building block composed of six benzene rings attached to the periphery of a coronene molecule (Sepúlveda et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2022). The c-HBC unit, as shown in Figure 1, when copolymerized with pyrene-2,7-diboronic acid (PDBA), results in the formation of a highly crystalline two-dimensional COF known as Marta-COF-1 (Abadía et al., 2019). Notably, the c-HBC nodes and the PDBA display substantial -areas and extensive -stacking within the resulting COF. In response to this, a comparable COF labeled Marta-COF-2 has been created, synthesized and investigated with the substitution of pyrene-2,7-diboronic acid by benzene-1,4-diboronic acid (BDBA) (Abadía et al., 2021). As depicted in Figure 2, graphical diagram representations of the two COF frameworks, Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2, are illustrated to highlight their distinctive arrangements.

FIGURE 1.

Contorted hexabenzocoronene (c-HBC).

FIGURE 2.

The unit cell structures of (A) Marta-COF-1 (B) Marta-COF-2.

The two variations of highly crystalline Marta COFs can be evaluated through quantitative parameters called the topological descriptors that convert various structural attributes of the frameworks into measurable quantities. These quantifying functionals are essential for representing the molecular frameworks and are useful for QSPR and QSAR analyses (Jafari et al., 2024; Patil et al., 2024; Nath et al., 2023; Hayat et al., 2023). The incorporation of topological descriptors and graph-derived metrics in QSAR/QSPR studies has been extensively used in the domain of computational and material sciences. This amalgamation has provided robust tools for predicting structural behaviors and designing new materials with desired properties or functionalities. These approaches enable researchers to explore numerous applications, including drug discovery, material optimization, and the development of materials that can be tailored for specific applications or objectives (Balasubramanian and Saxena, 2021; Balasubramanian, 2022; Arockiaraj et al., 2023a; Hasani and Ghods, 2024; Abubakar et al., 2024; Meharban et al., 2024; Ullah et al., 2024; Shanmukha et al., 2023a; Gnanaraja et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023; Hassan et al., 2024).

The graph entropy measure enables the evaluation of the inherent complexity and diversity of COFs. This measure provides valuable insights into the arrangement and functioning of COF structures by associating fundamental graph components with appropriate weights (Junias and Clement, 2023; Arockiaraj et al., 2024a; Chu et al., 2023; Roy et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023; Lal et al., 2024). The applications of graph entropy continue to expand its relevance and significance across diverse domains due to its adaptable nature that surpasses disciplinary boundaries and facilitates the analysis of complex systems (Arockiaraj et al., 2023b; Junias et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2024). In recent years, there has been significant interest in the computation of topological expressions and entropies for COFs (Yang et al., 2024; Arockiaraj et al., 2023c; Augustine and Roy, 2022; Shanmukha et al., 2023b; Arockiaraj et al., 2024b). In this study, we provide hybrid topological characterizations and entropies for two variations of Marta COFs and conduct a comparative analysis of the bond-wise entropy of these frameworks. Furthermore, we construct regression models to predict the graph energy of these frameworks based on the calculated topological indices.

2 Computational methods

We consider the Marta-COF as a molecular graph where the sets and represent the atoms and bonds respectively. Our mathematical computation involves deriving topological descriptors and entropies, incorporating hybrid descriptors based on vertex degree and degree-sum parameters. The number of bonds incident to a vertex is denoted as which represents the degree of a vertex . Additionally, the total sum of the degrees of all neighbors of vertex is denoted as which is defined as the degree-sum of vertex . That is, in which we used . Let and . The total number of edges within Marta-COFs is classified into distinct edge classes based on symmetrical representations related to and . These edge classes are labeled as (Marta-COF) and (Marta-COF), respectively.

We now define the additive and multiplicative versions of topological descriptors related to the degree and degree-sum parameters of Marta-COF, involving the index function , as follows (Hakeem et al., 2023; Paul et al., 2023; Arockiaraj et al., 2022; Mondal et al., 2022; Arockiaraj et al., 2023d; Ramane et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2023; Zaman et al., 2023; Hassan et al., 2024):

When the index function is raised to its own power, the resulting versions of topological descriptors can take the following forms:

The index functions are considered in our study, as stated below (Arockiaraj et al., 2024a; Arockiaraj et al., 2024b; Arockiaraj et al., 2023e; Arockiaraj et al., 2024c).

(Bi Zagreb)

(Tri Zagreb)

(Geometric Harmonic)

(Geometric Bi-Zagreb)

(Geometric Tri-Zagreb)

(Harmonic Geometric)

(Harmonic Bi-Zagreb)

(Harmonic Tri-Zagreb)

(Bi-Zagreb Geometric)

(Bi-Zagreb Harmonic)

(Tri-Zagreb Geometric)

(Tri-Zagreb Harmonic)

These index functions, combined with the edge classes based on and , lead to the formation of topological descriptors. However, the representative element in the edge classes does not account for the specific types of atoms involved at their terminal points. Since three types of atoms are present in Marta covalent organic frameworks, which constitute the basis for Marta, it is important to distinguish between the atoms. Therefore, we involve weight functions that consider both the atoms and bonds, thereby enhancing the partitions based on and . The weight function for atoms will be denoted by the symbol , while will represent the weight function for bonds. Particularly, represents the weight assigned to atom B, while denotes the weight function corresponding to the bond B C. As a result, the edge classification of Marta-COFs will undergo additional refinement through the utilization of the bond weight function.

In employing Shannon’s entropy method, defining a structural information function on the bonds of Marta-COFs is necessary. In our study, we adopt the index function derived from degree or degree-sum parameters of Marta-COFs corresponding to the structural information function. The entropy of Marta-COF structures using the structural information function is defined on and takes the following form.

In a series of papers (Arockiaraj et al., 2023c; Mushtaq et al., 2022; Raza et al., 2023), the significance and implications of substituting the multiplicative factor have been comprehensively explored concerning the scalar multiplicative index. This leads to the formulation of the modified version of entropy as presented below.

3 Results and discussion

In this section, the two types of Marta-COFs are analyzed, and their structural properties are compared using topological descriptors and entropies. We consider the geometrical configuration of bi-trapezium (BT) shaped arrangements of Marta-COFs, which yield diverse configurations of Marta-COF layers. These Marta-COF structures are constructed using the unit cells as shown in Figure 2, which are the fundamental building blocks.

The Marta-COF-BT geometric formation is achieved by arranging units linearly to form the base and units to form the non-parallel sides, subject to the conditions and . By fixing and respectively, the hexagonal and parallelogram geometries are extracted from the BT configurations which are denoted by Marta-COF-H and Marta-COF-P . The linear chain of Marta-COFs is derived by setting and is represented as Marta-COF-L . The representations of hexagonal structures for two variations of Marta-COFs are depicted in Figures 3, 4.

FIGURE 3.

Hexagonal Marta-COF-1 with dimension 2.

FIGURE 4.

Hexagonal Marta-COF-2 with dimension 2.

Furthermore, the covalent organic framework Marta-COF-1-BT is composed of vertices and edges, while Marta-COF-2-BT comprises vertices and edges. We have computed diverse molecular descriptors of Marta COFs by calculating degree and degree-sum parameters and the distribution of bonds are shown in Tables 1, 2. The explicit mathematical expressions for these descriptors in Marta-COFs are derived by assigning unit weights to atoms and bonds.

TABLE 1.

Bond partitioning of Marta-COF-1-BT and Marta-COF-2-BT according to degree classes.

| Bond S T |

Number of degree bonds | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marta-COF-1-BT | Marta-COF-2-BT | ||

| B O | |||

| O C | |||

| C C | |||

| B C | |||

TABLE 2.

Bond partitioning of Marta-COF-1-BT and Marta-COF-2-BT according to degree-sum classes.

| Bond S T |

Number of degree-sum bonds | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marta-COF-1-BT | Marta-COF-2-BT | ||

| B O | |||

| O C | |||

| C C | |||

| B C | |||

The degree based descriptors for Marta-COF-1-BT are obtained for using the following equation.

In computing the degree-sum descriptors of Marta-COF-1-BT , we use

The resulting outcomes are given in the form, .

Result 1

The quantitative expressions for Marta-COF-1-BT are given by

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

The equations below generate the topological descriptors of Marta-COF-2-BT .

Result 2

The quantitative expressions for Marta-COF-2-BT are given by

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

To determine entropy values for the two variations of Marta-COFs, we use the quantitative expressions from the above derived results with the aid of scalar multiplicative self-powered descriptors. Let and . We denote and . Thus, the mathematical expressions representing Marta-COF-1 as self-powered descriptors are provided below.

1.

2.

Similarly for Marta-COF-2-BT , let and . We denote and . Then,

1.

2.

We are now ready to calculate the entropies of Marta-COFs using the provided mathematical expressions. Due to the complexity of these expressions, we determine the numerical values of Marta-COFs where the dimensions of the bi-trapezium configuration are set by BT . The computed entropies are presented in Tables 3, 4. Comparing the various descriptors, the tri-Zagreb-harmonic consistently demonstrates higher entropy values across all configuration phases in both Marta-COFs.

The entropies calculated for Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2 primarily depend on their total number of bonds, which is unequal due to the fixed dimensions of these COFs. To compare their entropies effectively and investigate structural characteristics like bond energy and stability, we employ a scaling process. We perform scaling for the hexagonal and parallelogram configurations of Marta-COFs between two variations by calculating the ratio of total degree entropies to the total number of bonds. Table 5 clearly shows that the bond-wise entropies of the Marta-COF-2 framework are consistently higher than those of Marta-COF-1 across all hexagonal and parallelogram configurations, as depicted in Figure 5. As a result, the Marta-COF-2 frameworks exhibit a higher degree of information disorder than the Marta-COF-1 frameworks.

TABLE 3.

Entropies calculated from degree/degree-sum parameters of Marta-COF-1-BT .

| 9.297 | 9.946 | 10.427 | 10.811 | 11.132 | 11.408 | 11.650 | 11.865 | 12.059 | ||

| 11.249 | 11.908 | 12.393 | 12.780 | 13.102 | 13.379 | 13.621 | 13.837 | 14.031 | ||

| 5.765 | 6.432 | 6.921 | 7.311 | 7.634 | 7.912 | 8.155 | 8.371 | 8.566 | ||

| 4.877 | 5.641 | 6.178 | 6.594 | 6.935 | 7.224 | 7.476 | 7.698 | 7.898 | ||

| 5.187 | 5.869 | 6.366 | 6.759 | 7.085 | 7.364 | 7.609 | 7.826 | 8.021 | ||

| 3.628 | 4.555 | 5.171 | 5.633 | 6.002 | 6.310 | 6.575 | 6.808 | 7.015 | ||

| 5.391 | 6.066 | 6.559 | 6.950 | 7.275 | 7.553 | 7.797 | 8.014 | 8.209 | ||

| 2.095 | 3.337 | 4.106 | 4.654 | 5.078 | 5.423 | 5.714 | 5.966 | 6.187 | ||

| 3.612 | 4.400 | 4.9460 | 5.366 | 5.709 | 5.999 | 6.251 | 6.474 | 6.674 | ||

| 5.261 | 6.018 | 6.552 | 6.967 | 7.308 | 7.597 | 7.849 | 8.072 | 8.272 | ||

| 2.876 | 3.751 | 4.338 | 4.782 | 5.139 | 5.439 | 5.698 | 5.926 | 6.129 | ||

| −25.217 | −14.384 | −8.897 | −5.637 | −3.495 | −1.986 | −0.866 | −0.002 | 0.685 | ||

| 8.876 | 9.525 | 10.006 | 10.390 | 10.711 | 10.986 | 11.228 | 11.443 | 11.638 | ||

| 9.523 | 10.178 | 10.662 | 11.048 | 11.370 | 11.646 | 11.888 | 12.104 | 12.298 | ||

| 10.851 | 11.499 | 11.981 | 12.365 | 12.686 | 12.962 | 13.203 | 13.419 | 13.613 | ||

| 13.487 | 14.152 | 14.640 | 15.028 | 15.351 | 15.628 | 15.871 | 16.087 | 16.281 | ||

| 9.428 | 10.076 | 10.557 | 10.942 | 11.263 | 11.538 | 11.780 | 11.995 | 12.190 | ||

| 10.377 | 11.034 | 11.519 | 11.905 | 12.227 | 12.504 | 12.746 | 12.962 | 13.156 | ||

| 11.412 | 12.062 | 12.543 | 12.928 | 13.249 | 13.524 | 13.766 | 13.982 | 14.176 | ||

| 14.352 | 15.021 | 15.510 | 15.898 | 16.221 | 16.498 | 16.741 | 16.957 | 17.152 | ||

| 9.852 | 10.501 | 10.981 | 11.366 | 11.686 | 11.962 | 12.204 | 12.419 | 12.613 | ||

| 11.279 | 11.911 | 12.384 | 12.763 | 13.081 | 13.354 | 13.594 | 13.808 | 14.001 | ||

| 10.408 | 11.057 | 11.539 | 11.923 | 12.244 | 12.520 | 12.762 | 12.977 | 13.171 | ||

| 12.347 | 12.464 | 13.497 | 13.884 | 14.207 | 14.483 | 14.726 | 14.942 | 15.136 | ||

TABLE 4.

Entropies calculated from degree/degree-sum parameters of Marta-COF-2-BT .

| 9.119 | 9.758 | 10.234 | 10.615 | 10.934 | 11.207 | 11.448 | 11.662 | 11.855 | ||

| 11.071 | 11.721 | 12.202 | 12.585 | 12.905 | 13.180 | 13.421 | 13.635 | 13.829 | ||

| 5.585 | 6.246 | 6.732 | 7.119 | 7.441 | 7.717 | 7.959 | 8.174 | 8.369 | ||

| 4.686 | 5.449 | 5.985 | 6.401 | 6.741 | 7.030 | 7.281 | 7.503 | 7.702 | ||

| 5.006 | 5.684 | 6.178 | 6.570 | 6.895 | 7.173 | 7.416 | 7.632 | 7.827 | ||

| 3.411 | 4.346 | 4.967 | 5.431 | 5.803 | 6.112 | 6.378 | 6.611 | 6.818 | ||

| 5.218 | 5.888 | 6.378 | 6.767 | 7.091 | 7.367 | 7.611 | 7.826 | 8.021 | ||

| 1.860 | 3.121 | 3.901 | 4.455 | 4.884 | 5.232 | 5.526 | 5.779 | 6.002 | ||

| 3.404 | 4.202 | 4.752 | 5.175 | 5.519 | 5.811 | 6.063 | 6.286 | 6.486 | ||

| −10.573 | −5.293 | −2.516 | −0.805 | 0.357 | 1.205 | 1.854 | 2.371 | 2.796 | ||

| 2.648 | 3.543 | 4.139 | 4.588 | 4.949 | 5.251 | 5.511 | 5.740 | 5.945 | ||

| −26.290 | −15.212 | −9.558 | −6.185 | −3.965 | −2.399 | −1.237 | −0.341 | 0.372 | ||

| 8.701 | 9.340 | 9.815 | 10.196 | 10.515 | 10.789 | 11.029 | 11.243 | 11.436 | ||

| 9.345 | 9.991 | 10.471 | 10.853 | 11.172 | 11.447 | 11.688 | 11.902 | 12.096 | ||

| 10.671 | 11.311 | 11.788 | 12.169 | 12.487 | 12.761 | 13.001 | 13.216 | 13.409 | ||

| 13.312 | 13.969 | 14.452 | 14.837 | 15.157 | 15.432 | 15.674 | 15.889 | 16.082 | ||

| 9.249 | 9.889 | 10.365 | 10.746 | 11.064 | 11.338 | 11.578 | 11.793 | 11.986 | ||

| 10.198 | 10.847 | 11.327 | 11.710 | 12.029 | 12.304 | 12.545 | 12.759 | 12.953 | ||

| 11.232 | 11.872 | 12.349 | 12.731 | 13.049 | 13.323 | 13.563 | 13.777 | 13.971 | ||

| 14.178 | 14.838 | 15.322 | 15.707 | 16.028 | 16.303 | 16.545 | 16.759 | 16.953 | ||

| 9.674 | 10.313 | 10.789 | 11.171 | 11.489 | 11.762 | 12.003 | 12.217 | 12.411 | ||

| 11.179 | 11.802 | 12.270 | 12.646 | 12.961 | 13.233 | 13.472 | 13.685 | 13.877 | ||

| 10.229 | 10.869 | 11.345 | 11.726 | 12.044 | 12.318 | 12.559 | 12.773 | 12.966 | ||

| 12.169 | 12.823 | 13.305 | 13.689 | 14.009 | 14.284 | 14.525 | 14.740 | 14.934 | ||

TABLE 5.

Scaled entropy values for parallelogram and hexagonal configurations between Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2.

| Marta-COF-1 | Marta-COF-2 | Marta-COF-1 | Marta-COF-2 | Marta-COF-1 | Marta-COF-2 | Marta-COF-1 | Marta-COF-2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0022 | 0.0026 | 0.0015 | 0.0018 | 0.0011 | 0.0013 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | |

| 0.0014 | 0.0016 | 0.001 | 0.0012 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | |

| 0.001 | 0.0012 | 0.0008 | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | |

| 0.0009 | 0.001 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | |

| 0.0025 | 0.0030 | 0.0018 | 0.0021 | 0.0013 | 0.0015 | 0.0008 | 0.0010 | |

| 0.0026 | 0.0031 | 0.0018 | 0.0022 | 0.0013 | 0.0016 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | |

| 0.0013 | 0.0016 | 0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | 0.0004 | 0.0005 | |

| 0.0014 | 0.0017 | 0.001 | 0.0012 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.0006 | |

| 0.0021 | 0.0025 | 0.0015 | 0.0018 | 0.0011 | 0.0013 | 0.0007 | 0.0008 | |

| 0.0022 | 0.0026 | 0.0016 | 0.0019 | 0.0011 | 0.0013 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | |

| 0.0023 | 0.0027 | 0.0016 | 0.0019 | 0.0012 | 0.0014 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | |

| 0.0024 | 0.0029 | 0.0017 | 0.0020 | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | 0.0008 | 0.0010 | |

FIGURE 5.

Bar diagrams of scaled entropies (A, B) Marta-COF-1-H and Marta-COF-2-H , (C, D) Marta-COF-1-P and Marta-COF-2-P. .

4 Prediction of graph energy

A prominent application of spectral graph theory is its ability to relate graph spectrum to the molecular orbital energy levels of -electrons in conjugated hydrocarbons (Graovac et al., 1975; Gutman and Furtula, 2017). The concept of total -electron energy originated from Hückel molecular orbital theory, specifically for alternant hydrocarbons frameworks. In spectral graph theory, the -electron energy is approximately proportional to the graph-based energy for alternant hydrocarbons; however, this does not hold for general frameworks. Nevertheless, this approach can be extended to graphs containing heteroatoms by treating them similarly to graphs composed of carbon atoms. Let be a graph of order with adjacency matrix . The eigenvalues of are denoted as , …, constitute graph spectrum (Gutman, 1978; Kalaam et al., 2024). The graph energy , typically expressed in -units, for a graph is defined as the sum of the absolute values of its eigenvalues, as shown below.

Evaluating the graph energy of Marta covalent organic frameworks in higher-order dimensions presents challenges in generating adjacency matrices and solving the associated problem. However, software like newGRAPH (Stevanović et al., 2021) is useful to some extent for addressing this issue in smaller-dimensional frameworks. Therefore, we compute the energy values for specific graph frameworks of using the newGRAPH software, as shown in Table 6. Based on these values, we developed statistical models to predict the energy values for higher dimensions by consolidating data from various frameworks into a unified dataset.

TABLE 6.

Energy values for Marta-COF-1-BT and Marta-COF-2-BT .

| Marta-COF-1-BT | in units | Marta-COF-2-BT | in units |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1,1) | 629.91736 | (1,1) | 542.93298 |

| (2,1) | 1073.14678 | (2,1) | 913.67542 |

| (2,2) | 1749.63317 | (2,2) | 1474.18263 |

| (3,1) | 1516.37621 | (3,1) | 1284.41785 |

| (3,2) | 2659.37652 | (3,2) | 2224.45461 |

| (3,3) | 3335.86291 | (3,3) | 2784.96182 |

| (4,1) | 1959.60563 | (4,1) | 1655.16029 |

| (4,2) | 3569.11987 | (4,2) | 2974.72660 |

We conducted a correlation analysis to explore the relationship between topological descriptors and graph energy in two Marta-COFs. Next, we applied simple linear regression to examine the relationship between these two quantitative variables, providing a clear representation of the link between the predictor and the dependent variable. The proposed equation relating graph energy to topological descriptors is presented below.

where and are constants, and we also include the other statistical parameters such as standard error (Se) and the -value.

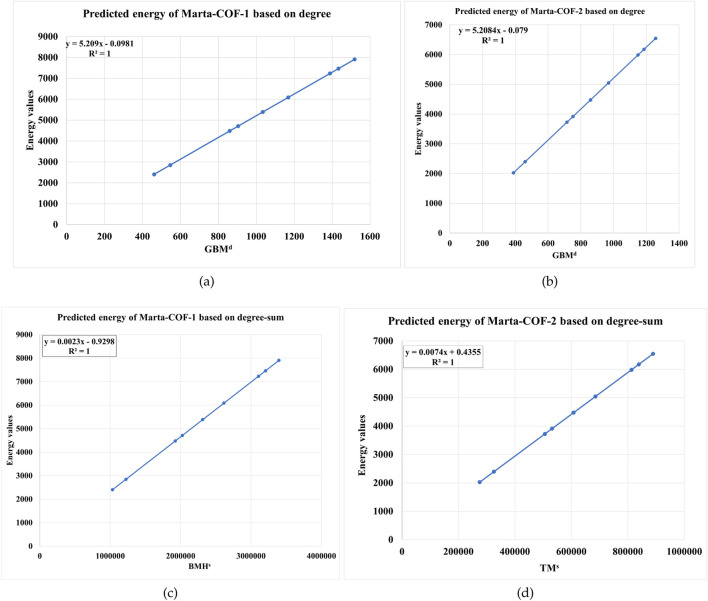

Based on the correlation analysis, we identified the optimal predictive models for Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2 based on degree descriptors. The geometric-bi-Zagreb index yielded a perfect correlation for both frameworks, with the lowest standard error (Se) and the highest value. The linear regression equations derived from the geometric-bi-Zagreb index are presented below.

In the same way, the linear regression equations derived from degree-sum descriptors particularly the bi-Zagreb harmonic index for Marta-COF-1-BT and the tri-Zagreb index for Marta-COF-2-BT yield the most accurate predictive models, as shown below.

Using the regression equations mentioned above, we estimated the graph energy of Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2 based on both degree and degree-sum descriptors in higher dimensions. The resulting predictions are presented in Tables 7, 8 and visually depicted in Figure 6. The predicted energy of Marta-COFs based on degree descriptors shows a perfect correlation compared to degree-sum descriptors, making these predictive models useful for estimating graph energy values in higher-dimensional Marta-COFs.

TABLE 7.

Comparison of predicted energy for Marta-COF-1 based on degree and degree-sum descriptors.

| Marta-COF-1-BT | Predicted in units by | Predicted in units by |

|---|---|---|

| Marta-COF-1-BT (4,3) | 4712.088025 | 4711.848507 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (4,4) | 5388.629944 | 5388.378539 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (5,1) | 2402.877657 | 2403.240586 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (5,2) | 4478.844391 | 4478.694523 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (5,3) | 6088.200927 | 6087.840491 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (5,4) | 7231.059257 | 7230.678492 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (5,5) | 7907.710565 | 7907.208525 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (6,1) | 2846.122289 | 2846.616635 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (6,2) | 5388.629944 | 5388.378539 |

| Marta-COF-1-BT (6,3) | 7464.423218 | 7463.832476 |

TABLE 8.

Comparison of predicted energy for Marta-COF-2 based on degree and degree-sum descriptors.

| Marta-COF-2-BT | Predicted in units by | Predicted in units by |

|---|---|---|

| Marta-COF-2-BT (4,3) | 3914.740053 | 3914.766728 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (4,4) | 4475.250718 | 4475.235789 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (5,1) | 2025.936362 | 2025.648081 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (5,2) | 3724.984055 | 3724.959645 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (5,3) | 5044.519232 | 5044.657041 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (5,4) | 5984.3221 | 5984.740269 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (5,5) | 6545.261934 | 6545.209329 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (6,1) | 2396.688729 | 2396.310057 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (6,2) | 4475.250718 | 4475.235789 |

| Marta-COF-2-BT (6,3) | 6174.427058 | 6174.547353 |

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of predicted graph energy based on degree/degree-sum (A, B) Marta-COF-1-BT and (C, D) Marta-COF-2-BT. .

5 Conclusion

The mathematical expressions for topological descriptors have been formulated, and entropy quantities for two variations of Marta-COFs have been derived. A refined edge partition technique has been employed, involving the use of innovative hybrid descriptors that combine geometric, harmonic, and Zagreb descriptors. Furthermore, a comparative analysis between Marta-COF-1 and Marta-COF-2 has been conducted, revealing that higher entropy values were consistently displayed by Marta-COF-2 in both hexagonal and parallelogram frameworks compared to Marta-COF-1. Optimal linear regression models to predict graph energy across different dimensional Marta frameworks have also been developed, significantly reducing computational complexity. These findings and techniques can be applied to link properties such as mechanical stability, solubility, hardness, and electrophilicity, provided that experimental data are available.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. ZR is supported by the University of Sharjah Research Grant No. 23021440148 and MASEP Research Group.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

ZR: Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing. MA: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. AM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft. AS: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing–review and editing.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abadía M. M., Stoppiello C. T., Strutynski K., Berlanga B. L., Gastaldo C. M., Saeki A., et al. (2019). A wavy two-dimensional covalent organic framework from core-twisted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (36), 14403–14410. 10.1021/jacs.9b07383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abadía M. M., Strutynski K., Stoppiello C. T., Berlanga B. L., Gastaldo C. M., Khlobystov A. N., et al. (2021). Understanding charge transport in wavy 2D covalent organic frameworks. Nanoscale 13 (14), 6829–6833. 10.1039/d0nr08962a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar M. S., Aremu K. O., Aphane M., Amusa L. B. (2024). A QSPR analysis of physical properties of antituberculosis drugs using neighbourhood degree-based topological indices and support vector regression. Heliyon 10, e28260. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algieri C., Drioli E. (2021). Zeolite membranes: synthesis and applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 278, 119295. 10.1016/j.seppur.2021.119295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Fiona J. C., Abraham J., Klavžar S., Balasubramanian K. (2024a). Guanidinium and hydrogen carbonate rosette layers: distance and degree topological indices, szeged-type indices, entropies, and NMR spectral patterns. Heliyon 10, e24814. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Fiona J. C., Shalini A. J. (2024c). Comparative study of entropies in silicate and oxide frameworks. Silicon 16, 3205–3216. 10.1007/s12633-024-02892-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Greeni A. B., Kalaam A. R. A. (2023a). Linear versus cubic regression models for analyzing generalized reverse degree based topological indices of certain latest corona treatment drug molecules. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 123 (16), e27136. 10.1002/qua.27136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Jency J., Maaran A., Abraham J., Balasubramanian K. (2023d). Refined degree bond partitions, topological indices, graph entropies and machine-generated boron NMR spectral patterns of borophene nanoribbons. J. Mol. Struct. 1295 (11), 136524. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.136524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Jency J., Mushtaq S., Shalini A. J., Balasubramanian K. (2023c). Covalent organic frameworks: topological characterizations, spectral patterns and graph entropies. J. Math. Chem. 61, 1633–1664. 10.1007/s10910-023-01477-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Paul D., Clement J., Tigga S., Jacob K., Balasubramanian K. (2023e). Novel molecular hybrid geometric-harmonic-Zagreb degree based descriptors and their efficacy in QSPR studies of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Sar. QSAR Environ. Res. 34 (7), 569–589. 10.1080/1062936x.2023.2239149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Paul D., Ghani M. U., Tigga S., Chu Y. M. (2023b). Entropy structural characterization of zeolites BCT and DFT with bond-wise scaled comparison. Sci. Rep. 13, 10874. 10.1038/s41598-023-37931-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Paul D., Klavžar S., Clement J., Tigga S., Balasubramanian K. (2022). Relativistic distance based and bond additive topological descriptors of zeolite RHO materials. J. Mol. Struct. 1250 (2), 131798. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131798 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arockiaraj M., Raza Z., Maaran A., Abraham J., Balasubramanian K. (2024b). Comparative analysis of scaled entropies and topological properties of triphenylene-based metal and covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Pap. 78, 4095–4118. 10.1007/s11696-023-03295-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine T., Roy S. (2022). Topological study on triazine-based covalent-organic frameworks. Symmetry 14 (8), 1590. 10.3390/sym14081590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K. (2021). “Relativistic quantum chemical and molecular dynamics techniques for medicinal chemistry of bioinorganic compounds,” in Biophysical and computational tools in drug discovery, topics in medicinal chemistry. Editor Saxena A. K. (Cham: Springer; ), 37, 133–193. 10.1007/7355_2020_109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian K. (2022). Computational and artificial intelligence techniques for drug discovery and administration, Compr. Adv. Pharmacol. 2, 553–616. 10.1016/B978-0-12-820472-6.00015-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Huang N., Gao J., Xu H., Xu F., Jiang D. (2014). Towards covalent organic frameworks with predesignable and aligned open docking sites. Chem. Commun. 50 (46), 6161–6163. 10.1039/c4cc01825g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Z.-Q., Siddiqui M. K., Manzoor S., Kirmani S. A. K., Hanif M. F., Muhammad M. H. (2023). On rational curve fitting between topological indices and entropy measures for graphite carbon nitride. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43 (3), 2553–2570. 10.1080/10406638.2022.2048034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cot̂é A. P., Benin A. I., Ockwing N. W., O’keeffe M., Matzger A. J., Yaghi O. M. (2005). Porous, crystalline, covalent organic frameworks. Science 310 (5751), 1166–1170. 10.1126/science.1120411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kaderi H. M., Hunt J. R., Cortés J. L. M., Cot̂é A. P., Taylor R. E., O’keeffe M., et al. (2007). Designed synthesis of 3D covalent organic frameworks. Science 316 (5822), 268–272. 10.1126/science.1139915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Wang H., Peng M., Meng H., Mundstock A., Knebel A., et al. (2023). Pore-in-pore engineering in a covalent organic framework membrane for gas separation. ACS Nano 17 (8), 7584–7594. 10.1021/acsnano.2c12774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng K., He T., Liu R., Dalapati S., Tan K. T., Li Z., et al. (2020). Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 120 (16), 8814–8933. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanaraja L. R. M., Ganesana D., Siddiqui M. K. (2023). Topological indices and QSPR analysis of NSAID drugs. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43 (10), 9479–9495. 10.1080/10406638.2022.2164315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y.-N., Guan X., Jiang H.-L. (2023). Covalent organic frameworks for photocatalysis: synthesis, structural features, fundamentals and performance. Coord. Chem. Rev. 475, 214889. 10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graovac A., Gutman I., Trianjistić N. (1975). On the coulson integral formula for total π-electron energy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 35 (4), 555–557. 10.1016/0009-2614(75)85666-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp C., Canossa S., Wuttke S., Gándara F., Li Q., Gagliardi L., et al. (2020). Standard practices of reticular chemistry. ACS Cent. Sci. 6 (8), 1255–1273. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c00592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman I. (1978). The energy of a graph, Ber. Math. Stat. Sekt. Forschungszentrum Graz 103, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gutman I., Furtula B. (2017). The total π-electron energy saga. Croat. Chem. Acta 90, 359–368. 10.5562/cca3189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hakeem A., Ullah A., Zaman S. (2023). Computation of some important degree-based topological indices for γ - graphyne and Zigzag graphyne nanoribbon. Mol. Phys. 121 (14), e2211403. 10.1080/00268976.2023.2211403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasani M., Ghods M. (2024). Topological indices and QSPR analysis of some chemical structures applied for the treatment of heart patients. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124 (1), e27234. 10.1002/qua.27234 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan M. M., Waqar A., Ali H., Ali P. (2024). Computation of connection-based Zagreb indices in chain graphs and triangular sheets. J. Coord. Chem. 77, 896–919. 10.1080/00958972.2024.2305819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haug W. K., Moscarello E. M., Wolfson E. R., McGrier P. L. (2020). The luminescent and photophysical properties of covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (3), 839–864. 10.1039/c9cs00807a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayat S., Suhaili N., Jamil H. (2023). Statistical significance of valency-based topological descriptors for correlating thermodynamic properties of benzenoid hydrocarbons with applications. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1227, 114259. 10.1016/j.comptc.2023.114259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou K., Gu H., Yang Y., Lam S. S., Li H., Sonne C., et al. (2023). Recent progress in advanced covalent organic framework composites for environmental remediation. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 6, 199. 10.1007/s42114-023-00776-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang N., Wang P., Jiang D. (2016). Covalent organic frameworks: a materials platform for structural and functional designs. Nat. Rev. Mater 1, 16068. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.68 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang R., Hanif M. F., Siddiqui M. K., Hanif M. F. (2024). On analysis of entropy measure via logarithmic regression model and Pearson correlation for Tri-s-triazine. Comput. Mater. Sci. 240, 112994. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.112994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari M., Isfahani T. M., Shafiei F., Senejani M. A. (2024). QSPR study to predict some of quantum chemical properties of anticancer imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine derivatives using genetic algorithm multiple linear regression and molecular descriptors. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 124 (1), e27259. 10.1002/qua.27259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao L., Seow J. Y. R., Skinner W. S., Wang Z. U., Jiang H.-L. (2019). Metal-organic frameworks: structures and functional applications. Mater. Today 27, 43–68. 10.1016/j.mattod.2018.10.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jrad A., Olson M. A., Trabolis A. (2023). Molecular design of covalent organic frameworks for seawater desalination: a state-of-the-art review. Chem 9 (6), 1413–1451. 10.1016/j.chempr.2023.04.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Junias J. S., Clement J. (2023). Predictive analytics of conductance and HOMO-LUMO gaps with topological descriptors of porphyrin nanosheets. Phys. Scr. 99 (1), 015208. 10.1088/1402-4896/ad0c1b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Junias J. S., Clement J., Rahul M. P., Arockiaraj M. (2024). Two-dimensional phthalocyanine frameworks: topological descriptors, predictive models for physical properties and comparative analysis of entropies with different computational methods. Comput. Mater. Sci. 235, 112844. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2024.112844 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaam A. R. A., Greeni A. B., Arockiaraj M. (2024). Modified reverse degree descriptors for combined topological and entropy characterizations of 2D metal organic frameworks: applications in graph energy prediction. Front. Chem. 12, 1470231. 10.3389/fchem.2024.1470231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J., Kang M., Kim Y. H., Suh E.-K., Yang M., Cho S. Y., et al. (2022). Contorted hexabenzocoronene derivatives as a universal organic precursor for dimension-customized carbonization. Carbon 200, 21–27. 10.1016/j.carbon.2022.08.049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn P., Antonietti M., Thomas A. (2008). Porous, covalent triazine-based frameworks prepared by ionothermal synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (18), 3450–3453. 10.1002/anie.200705710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S., Bhat V. K., Sharma S. (2024). Topological indices and graph entropies for carbon nanotube Y-junctions. J. Math. Chem. 62, 73–108. 10.1007/s10910-023-01520-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Li H., Dai Q., Li H., Brédas J.-L. (2018). Hydrolytic stability of boronate ester-linked covalent organic frameworks. Adv. Theory Simul. 1 (2), 1700015. 10.1002/adts.201700015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meharban S., Ullah A., Zaman S., Hamraz A., Razaq A. (2024). Molecular structural modeling and physical characteristics of anti-breast cancer drugs via some novel topological descriptors and regression models. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 7, 100134. 10.1016/j.crstbi.2024.100134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal S., De N., Pal A. (2022). Topological indices of some chemical structures applied for the treatment of COVID-19 patients. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 42 (4), 1220–1234. 10.1080/10406638.2020.1770306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq S., Arockiaraj M., Fiona J. C., Jency J., Balasubramanian K. (2022). Topological properties, entropies, stabilities and spectra of armchair versus zigzag coronene-like nanoribbons. Mol. Phys. 120 (17), e2108518. 10.1080/00268976.2022.2108518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A., Ojha P. K., Roy K. (2023). QSAR assessment of aquatic toxicity potential of diverse agrochemicals. Sar. QSAR Environ. Res. 34 (11), 923–942. 10.1080/1062936x.2023.2278074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil V. M., Gupta S. P., Masand N., Balasubramanian K. (2024). Experimental and computational models to understand protein-ligand, metal-ligand and metal-DNA interactions pertinent to targeted cancer and other therapies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 10, 100133. 10.1016/j.ejmcr.2024.100133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul D., Arockiaraj M., Jacob K., Clement J. (2023). Multiplicative versus scalar multiplicative degree based descriptors in QSAR/QSPR studies and their comparative analysis in entropy measures. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138, 323. 10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-03920-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramane H. S., Pise K. S., Jummannaver R. B., Patil D. D. (2021). Applications of neighbors degree sum of a vertex on zagreb indices, MATCH Commun. Math. Comput. Chem. 85, 329–348. [Google Scholar]

- Raza Z., Arockiaraj M., Maaran A., Kavitha S. R. J., Balasubramanian K. (2023). Topological entropy characterization, NMR and ESR spectral patterns of coronene-based transition metal organic frameworks. ACS Omega 8 (14), 13371–13383. 10.1021/acsomega.3c00825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. G. S., Balasubramanian K., Prabhu S. (2023). Topological indices and entropies of triangular and rhomboidal tessellations of kekulenes with applications to NMR and ESR spectroscopies. J. Math. Chem. 61, 1477–1490. 10.1007/s10910-023-01465-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sepúlveda D., Guan Y., Rangel U., Wheeler S. E. (2017). Stacked homodimers of substituted contorted hexabenzocoronenes and their complexes with C60 fullerene. Org. Biomol. Chem. 15 (28), 6042–6049. 10.1039/c7ob01333g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmukha M. C., Ismail R., Gowtham K. J., Usha A., Azeem M., Sabri E. H. A. A. (2023b). Chemical applicability and computation of K-Banhatti indices for benzenoid hydrocarbons and triazine-based covalent organic frameworks. Sci. Rep. 13, 17743. 10.1038/s41598-023-45061-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmukha M. C., Usha A., Basavarajappa N. S., Shilpa K. C. (2023a). Comparative study of multilayered graphene using numerical descriptors through M-polynomial. Phys. Scr. 98 (7), 075205. 10.1088/1402-4896/acd820 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Yang J., Gao F., Zhang Q. (2023). Covalent organic frameworks: recent progress in biomedical applications. ACS Nano 17 (3), 1879–1905. 10.1021/acsnano.2c11346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevanović L., Brankov V., Cvetković D. (2021). 21S. Simić, newGRAPH: a fully integrated environment used for research process in graph theory. Available at: http://www.mi.sanu.ac.rs/newgraph/index.html.

- Sun J., Xu Y., Lv Y., Zhang Q., Zhou X. (2023). Recent advances in covalent organic framework electrode materials for alkali metal-ion batteries. CCS Chem. 5 (6), 1259–1276. 10.31635/ccschem.023.202302808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah A., Jama M., Zaman S. (2024). Shamsudin, Connection based novel AL topological descriptors and structural property of the zinc oxide metal organic frameworks. Phys. Scr. 99 (5), 055202. 10.1088/1402-4896/ad350c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Wang H., Wang Z., Tang L., Zeng G., Xu P., et al. (2020). Covalent organic framework photocatalysts: structures and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (12), 4135–4165. 10.1039/d0cs00278j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghi O. M. (2016). Reticular chemistry construction, properties, and precision reactions of frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (48), 15507–15509. 10.1021/jacs.6b11821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghi O. M. (2019). Reticular chemistry in all dimensions. ACS Cent. Sci. 5 (8), 1295–1300. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Hanif M. F., Siddiqui M. K., Hussain M., Hussain N., Fufa S. A. (2024). On topological analysis of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks via M-polynomial. Sci. Rep. 14, 6931. 10.1038/s41598-024-57291-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Wang D., Meng Z., Li Y. (2019). Adsorption separation of CH4/N2 on modified coal-based carbon molecular sieve. Sep. Purif. Technol. 218, 130–137. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.02.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Khalid A., Aamir M., Siddiqui M. K., Muhammad M. H., Bashir Y. (2023). On some topological indices of metal-organic frameworks. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43 (6), 5607–5628. 10.1080/10406638.2022.2105909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman S., Jalani M., Ullah A., Ali M., Shahzadi T. (2023). On the topological descriptors and structural analysis of cerium oxide nanostructures. Chem. Pap. 77, 2917–2922. 10.1007/s11696-023-02675-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhu M., Schmidt O. G., Chen S., Zhang K. (2021). Covalent organic frameworks for efficient energy electrocatalysis: rational design and progress. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2 (4), 2000090. 10.1002/aesr.202000090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Saif M. J., Idrees N., Kanwal S., Parveen S., Saeed F. (2023). QSPR analysis of drugs for treatment of schizophrenia using topological indices. ACS Omega 8 (44), 41417–41426. 10.1021/acsomega.3c05000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Hanif M. F., Mahmood H., Siddiqui M. K., Hussain M., Hussain N. (2023). Topological analysis of entropy measure using regression models for silver iodide. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 138, 805. 10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-04432-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.