Abstract

It has been hypothesized that the biopsychosocial stress associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, in combination with the immunological effects of SARS-CoV-2 and pancreatic β-cell dysfunction, may contribute to the onset of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in children. In this study, we documented the incidences of T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan, from 1986 to 2018, and expanded the analysis to include cases from 2019 to 2022 to evaluate the potential influence of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on T1D incidence. The COVID-19 pandemic period was defined as 2020 to 2022. Data spanning from 1986 to 2022 were analyzed in annual increments, while data from 1987 to 2022 were analyzed in 3-year interval increments using Joinpoint regression analysis. Across all analyses, no joinpoints were identified, and a consistent linear increase was observed. These findings suggest that there was no statistically significant change in the incidence of T1D attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic in Yamanashi Prefecture. The annual increase in the incidence was calculated to be 3.384% per year, while the increase in the 3-year interval incidence was calculated to be 2.395% per year. Although the incidence of pediatric T1D among children aged 0–14 years in Yamanashi Prefecture increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (2020–2022), this trend appeared to be a continuation of the pre-2019 increase. The direct or indirect impact of COVID-19 on this trend could not be conclusively determined due to the limited number of cases included in this study.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-84654-z.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes, Coronavirus, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Incidence, Pandemic

Subject terms: Diseases, Endocrinology, Health care, Medical research

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is characterized by the autoimmune-mediated destruction of pancreatic islet β-cells, leading to insufficient endogenous insulin production. Although the specific etiology and pathogenesis of T1D are incompletely understood, both genetic predispositions and environmental triggers are believed to play critical roles1. Studies involving monozygotic twins have underscored the genetic influence, revealing a concordance rate of 20–65% for T1D, suggesting that 35–80% of the risk may be attributed to environmental factors2,3. This significant environmental component is further supported by observations that genetic factors remain relatively constant within populations over time, whereas the incidence of pediatric T1D has increased, potentially implicating changing environmental conditions in its pathogenesis.

Evidence supporting the impact of environmental factors on T1D incidence includes increased rates observed among immigrants relocating to areas with higher T1D incidence, such as Sweden4, a surge in cases following the Los Angeles earthquake5, and a correlation with rising obesity rates6. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic introduced substantial changes to the social and physical environment of children, including lockdowns, curfews, and widespread mask usage, which varied significantly by region. These pandemic-related environmental shifts may have influenced the incidence of T1D.

Additionally, among environmental factors, infections with enteroviruses and other gastrointestinal and respiratory viruses are hypothesized to be among the causes of the onset of T1D. This is attributed to virus-induced autoimmunity, which leads to β-cell damage and the production of autoantibodies, resulting in the development of T1D7–10. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affects not only the respiratory system but also the intestinal tract11, and SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in the β-cells of patients who died from COVID-1912. Another report suggested that although there was no increase in islet autoantibodies, direct and indirect damage to β-cells by SARS-CoV-2 infection has been indicated13. Based on these reports and hypotheses, COVID-19, a viral gastrointestinal and respiratory infection, may also have some impact on the onset of T1D.

In light of these considerations, it is plausible that the multiple stresses induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, including direct viral effects and resulting societal and environmental changes, may have affected the incidence of pediatric T1D. This hypothesis is supported by a growing body of literature documenting variations in pediatric T1D incidence in different regions during the pandemic period.

Objectives

Our previous research documented the incidence of pediatric T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture from 1986 to 2018, providing a comprehensive baseline before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic14. Building on this foundational work, our current study aimed to elucidate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of pediatric T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture.

Through this investigation, we aimed to provide valuable insights into the interaction between pandemic-induced environmental changes and the incidence of pediatric T1D, with the ultimate goal of informing future healthcare strategies and research directions in the context of global health emergencies.

Methods

Data collection

This study enrolled pediatric patients aged 0–14 years (aged < 15 years) who were diagnosed with their first episode of acute-onset T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture using a methodology consistent with our previously published work14. We used three primary methods to identify new cases of acute-onset T1D:

A detailed examination during routine urinalysis led to a diagnosis of acute-onset T1D.

Collaboration with all medical institutions in Yamanashi Prefecture capable of treating pediatric patients, a total of 10 institutions, to identify first-episode acute-onset T1D patients presenting for care.

Enrollment data were obtained from the Medical Expense Subsidy Project for Specific Pediatric Chronic Diseases, a government support system for patients with diseases such as T1D. This subsidy project provides assistance with medical expenses to encourage enrollment among eligible patients.

To ensure comprehensive case ascertainment, we cross-referenced data from these sources to minimize the risk of omitting eligible patients from our study cohort. The Medical Expense Subsidy Project for Specific Pediatric Chronic Diseases facilitates medical cost reductions for enrolled patients, which may influence patient enrollment patterns. To address potential underreporting, our collaborating institutions proactively enrolled eligible patients in the subsidy program to further ensure study inclusivity.

In Yamanashi Prefecture, children with new-onset T1D must go to a medical institution where they can be hospitalized, and diabetes education is provided along with diabetes treatment in cooperation with the community and schools. Even if the patient goes to a hospital in a neighboring prefecture for treatment, the possibility of omission in this study is very low because most of them designate a medical institution in their area of residence (our collaborating medical institution) as their emergency site because ambulances cannot cross the prefecture during emergency transport. Therefore, we believe that the possibility of omission in this study is very low.

The observation period spanned from 1986 to 2022, incorporating newly diagnosed T1D cases in children aged 0–14 years (< 15 years) from 2019 to 2022 into our previously published study on the incidence of pediatric T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture (1986–2018)14.

The period from 1986 to 2019 was designated as the pre-pandemic period, while the period from 2020 to 2022 was defined as the COVID-19 pandemic period.

Diagnosis of type 1 diabetes

The diagnostic criteria for acute-onset T1D in this study have changed over time, reflecting advances in the understanding and diagnosis of the disease. For all patients identified prior to 2012, the diagnosis of acute-onset T1D was made by pediatricians at each participating site. These diagnoses were validated based on evidence of insulin deficiency, indicated by either a fasting serum C-peptide concentration of less than 0.5 ng/mL or a urinary C-peptide excretion of less than 20 µg/day. In addition, the presence of serum autoantibodies associated with T1D, namely, anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody, insulin autoantibody (IAA), islet antigen-2 (IA-2) antibody, and islet cell antibody (ICA), was confirmed whenever possible.

After 2012, all patients met the Japan Diabetes Society diagnostic criteria for acute-onset T1D. Patients with acute-onset T1D were diagnosed as follows:

1) Presentation with classic symptoms of diabetes such as thirst, polydipsia, polyuria, and an expected progression to ketoacidosis within approximately three months of disease onset. 2) Anticipation of the need for continuous insulin therapy shortly after diagnosis, with an expected temporary “honeymoon period”. " 3) The presence of autoantibodies associated with T1D, specifically GAD antibodies, IA-2 antibodies, IAA, ICA, or zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) antibodies, during the clinical course. In particular, IAA positivity must be confirmed prior to initiation of insulin therapy. 4) In patients without islet autoantibodies, a fasting serum C-peptide level less than 0.6 ng/mL indicates insufficient endogenous insulin secretion.

Based on these criteria, patients meeting criteria 1, 2, and 3 were diagnosed with acute-onset (autoimmune) T1D (type 1 A). Those meeting criteria 1, 2, and 4 were classified as having acute-onset T1D (type 1B).

In 2004, the Japan Diabetes Society announced the diagnostic criteria for fulminant type 1 diabetes (FT1D), and in 2012, an updated version was announced15. The diagnostic criteria are shown below. Those who met the diagnostic criteria were diagnosed with FT1D and excluded from this study. Criteria for definite diagnosis of FT1D (2004). FT1D is confirmed when all the following three findings are present: (1) Occurrence of diabetic ketosis or ketoacidosis soon (approximately 7 days) after the onset of hyperglycemic symptoms (elevation of urinary and/or serum ketone bodies at first visit). (2) Plasma glucose level ≥ 16.0 mmol/L (≥ 288 mg/dL) and glycated hemoglobin level < 8.5% (Japan Diabetes Society value) at first visit. (3) Urinary C-peptide excretion < 10 µg/day or fasting serum C‐peptide level < 0.3 ng/mL (< 0.10 nmol/L) and < 0.5 ng/mL (< 0.17 nmol/L) after intravenous glucagon (or after meal) load at onset. The changes in the revised guidelines for 2012 are as follows. The HbA1c in (3) has been changed to 8.7% of the NGSP value, and the following finding has been added: F) Association with HLA DRB1*04:05‐DQB1*04:01 is reported.

In summary, cases from 2012 onwards were those that met the diagnostic criteria for acute-onset T1D as defined by the Japan Diabetes Society, and cases from before 2012 were included in this study only after the attending pediatrician confirmed a decrease in insulin secretion capacity or a positive result for diabetes-related autoantibodies. In practice, however, all cases were diagnosed through careful examinations to verify the presence of T1D-related autoantibodies detectable at the time, along with evidence of impaired insulin secretion, insulin dependence, or progression of these symptoms, before being registered in this study.

In contrast, regarding FT1D, it is hypothesized that cases before 2004 may have been misclassified as T1D (type 1B). However, as FT1D is an exceedingly rare condition in children, it is considered highly unlikely that such cases were included in this study.

From the above, it can be concluded that nearly all cases registered in this study represent acute-onset T1D.

Incidence calculation

First, we calculated the annual crude incidences of T1D in the pediatric population (aged 0 to 14 years) from January 1986 to December 2022 (see Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1). The calculation method was to divide the number of new cases of T1D each year during this period by the population of 0- to 14-year-olds in Yamanashi Prefecture each year. Population data were obtained from the Japanese National Census16–19.

Table 1.

The number of cases of type 1 diabetes, incidence, and modeled crude rate (per 100,000 person-years) were analyzed for each annual period from 1986 to 2022.

| 0- to -14-year-olds | Year | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 |

| Crude Incidence | 1.176 | 0.599 | 1.227 | 1.258 | 1.282 | 2.614 | 4.000 | 2.027 | 2.041 | 2.740 | 3.448 | 2.083 | 0.000 | 2.878 | 2.920 | 1.471 | 0.746 | 3.053 | 3.876 | |

| Number of Cases | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Population | 1,70,000 | 1,67,000 | 1,63,000 | 1,59,000 | 1,56,000 | 1,53,000 | 1,50,000 | 1,48,000 | 1,47,000 | 1,46,000 | 1,45,000 | 1,44,000 | 1,42,000 | 1,39,000 | 1,37,000 | 1,36,000 | 1,34,000 | 1,31,000 | 1,29,000 | |

| Modeled Crude Rate | 1.692 | 1.749 | 1.808 | 1.870 | 1.933 | 1.998 | 2.066 | 2.136 | 2.208 | 2.283 | 2.360 | 2.440 | 2.523 | 2.608 | 2.696 | 2.787 | 2.882 | 2.979 | 3.080 | |

| 0- to -14-year-olds | Year | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Crude Incidence | 3.150 | 1.613 | 5.738 | 3.333 | 3.419 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 4.545 | 3.738 | 5.714 | 1.961 | 0.990 | 1.010 | 1.031 | 7.071 | 2.083 | 3.158 | 9.783 | ||

| Number of Cases | 4 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 9 | ||

| Population | 1,27,000 | 1,24,000 | 1,22,000 | 1,20,000 | 1,17,000 | 1,16,000 | 1,12,000 | 1,10,000 | 1,07,000 | 1,05,000 | 1,02,000 | 1,01,000 | 99,000 | 97,000 | 99,000 | 96,000 | 95,000 | 92,000 | ||

| Modeled Crude Rate | 3.184 | 3.292 | 3.403 | 3.519 | 3.638 | 3.761 | 3.888 | 4.019 | 4.155 | 4.296 | 4.441 | 4.592 | 4.747 | 4.908 | 5.074 | 5.246 | 5.423 | 5.607 |

To address the small sample size, we grouped years into 3-year intervals and calculated the crude incidence for each interval. The intervals were as follows: 1987–1989, 1990–1992, 1993–1995, 1996–1998, 1999–2001, 2002–2004, 2005–2007, 2008–2010, 2011–2013, 2014–2016, 2017–2019, and 2020–2022. The crude incidence for each 3-year interval was determined by dividing the number of newly diagnosed cases during the interval by the population aged 0–14 years in Yamanashi Prefecture during the same interval (Table 2).

Table 2.

The number of cases of type 1 diabetes, incidence, and modeled crude rate (per 100,000 person-years) were analyzed for every 3-year interval from 1987 to 2022.

| 0- to -14-years-olds | 3-year Interval | 1987-1989 | 1990-1992 | 1993-1995 | 1996-1998 | 1999-2001 | 2002-2004 | 2005-2007 | 2008-2010 | 2011-2013 | 2014-2016 | 2017-2019 | 2020-2022 |

| Midpoint Year | 1988 | 1991 | 1994 | 1997 | 2000 | 2003 | 2006 | 2009 | 2012 | 2015 | 2018 | 2021 | |

| Crude Incidence | 1.022 | 2.614 | 2.268 | 1.856 | 2.427 | 2.538 | 3.485 | 2.266 | 2.736 | 2.922 | 3.051 | 4.947 | |

| Number of Cases | 5 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 14 | |

| Population | 4,89,000 | 4,59,000 | 4,41,000 | 4,31,000 | 4,12,000 | 3,94,000 | 3,73,000 | 3,53,000 | 3,29,000 | 3,08,000 | 2,95,000 | 2,83,000 | |

| Modeled Crude Rate | 1.800 | 1.933 | 2.075 | 2.228 | 2.392 | 2.568 | 2.757 | 2.960 | 3.177 | 3.411 | 3.662 | 3.932 |

Diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis

In this study, an effort was made to track the occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at the initial onset of T1D as thoroughly as possible. The diagnostic criteria for DKA were based on the guidelines of the Japan Diabetes Society. A diagnosis of DKA was considered when patients presented with blood glucose levels ≥ 250 mg/dL, elevated beta-hydroxybutyrate, arterial blood pH ≤ 7.30, and bicarbonate levels ≤ 18 mEq/L. The final diagnosis of DKA was made by the treating physician after confirmation that the criteria were met.

Statistical analysis

To evaluate temporal changes in the annual crude incidence (1986–2022) and the 3-year crude incidence (1987–2022) of T1D before and after the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed the data using the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 5.3.0.0, November 2024; Division of Statistics and Applied Research, National Cancer Institute, https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/). This analysis calculates the Annual Percent Change (APC) and 3-Year Percent Change (3PC) and employs statistical methods to identify significant changes in trends (joinpoints).

When entering data into the Joinpoint Regression Program, the following method was used for analysis. For the annual data, “year” was selected as the independent variable, and “Annual” was chosen as the “Interval Type.” For the 3-year interval data, “year” was also selected as the independent variable, but “Other” was chosen as the “Interval Type.”

For the annual data, the years 1986 to 2022 were sequentially entered in the “year” column, with the corresponding number of cases and the population aged 0–14 years entered for each year (Table 1). For the 3-year interval data, the midpoint year for each interval was calculated as the average of the three years and entered in the “Other” column. For instance, for the 1987–1989 interval, the midpoint year, 1988, was calculated as (1987 + 1988 + 1989)/3 and entered. Similarly, the values 1988, 1991, 1994, 1997, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2021 were entered as the midpoint years. The number of cases and population were entered as the total for each 3-year interval (Table 2).

For the dependent variable, “Calculated From Data File” was selected for the “Run Type,” and “Crude Rate” was chosen for the “Type of Variable.” A denominator of 100,000 was used for the rate calculations. For the annual data analysis, the number of cases was entered as the “Count Variable,” and the population aged 0–14 years as the “Population Variable.” For the 3-year interval data analysis, the total number of cases and the total population for each interval were entered.

For the “Heteroscedastic/Correlated Errors Option,” “Poisson Variance” was selected because the dependent variable (incidence = number of cases/population) follows a Poisson distribution.

The null hypothesis assumed no change in trends, with APC = 0% and 3PC = 0%. The significance level (α) was set at 0.05, and results with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Due to the small number of cases, a log-linear model was applied for the analysis.

Additionally, to compare the incidence of DKA and gender ratio before and during the pandemic, we conducted a chi-square test using R software (version 4.3.2, https://www.R-project.org/). The significance level (α) was set at 0.05, with p-values below this threshold deemed statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

This study was rigorously reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Yamanashi School of Medicine (IRB No: 2020–2215, entitled “Investigation of the Total Number of Pediatric Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Yamanashi Prefecture”). An anonymized dataset was used for patient data collection to protect patient privacy. The opt-out method was used to obtain informed consent, and informational posters were displayed at participating hospitals to allow patients and guardians to decline participation. All study procedures were carefully designed and conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the highest standards of ethical conduct in medical research.

Results

Epidemiological characteristics

During the study period from January 1986 to December 2022, a total of 120 pediatric patients who were diagnosed with T1D were enrolled in this study. By 2018, 99 patients were enrolled, and an additional 21 patients (consisting of 9 boys and 12 girls) were enrolled from 2019 to 2022. There were no cases of patients diagnosed with FT1D after 2004. The sex distribution of the entire cohort consisted of 53 boys and 67 girls, and the sex distribution from 1986 to 2019 was 45 boys and 61 girls. During the COVID-19 pandemic (from 2020 to 2022), there were 8 boys and 6 girls. We conducted a χ-square test to see if there was a difference in the gender ratio before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, but no significant difference was found (p = .451). Supplemental Table S1).

In terms of race and ethnicity, Asians make up the majority of the population in Japan. Among Asian groups, Japanese people are particularly numerous, and among ethnic groups other than Japanese, there are East Asian groups such as Koreans and Southeast Asian groups such as Filipinos. This is particularly evident in Yamanashi Prefecture, where there were almost no non-Asian patients. There was only one patient whose parents were not almost entirely Asian. However, his paternal grandfather was Japanese. There were two patients whose mother was of Southeast Asian descent and whose father was Japanese. Due to these results, it was not possible to make comparisons between the Japanese and other ethnic groups.

In 2019, during the recruitment of new patients under the Medical Expense Subsidy Project for Specific Pediatric Chronic Diseases, a discrepancy was noted in the identification of a male patient who had not previously been seen by our collaborating medical institutions. It was inferred that this patient sought treatment at a hospital in Tokyo, as inferred from the place of registration for subsidized medical expenses. However, due to the noncollaboration status of this hospital with our study and the subsequent inability to conduct a survey, this patient was excluded from our analysis.

Therefore, we estimated the case detection rate for our study to be 99.17%, reflecting a comprehensive capture of T1D cases in Yamanashi Prefecture during the study period.

Joinpoint regression analysis & crude incidence

As no statistically significant joinpoints were identified in the Joinpoint Regression Program analysis, a linear trend was applied to both the annual and 3-year interval analyses.

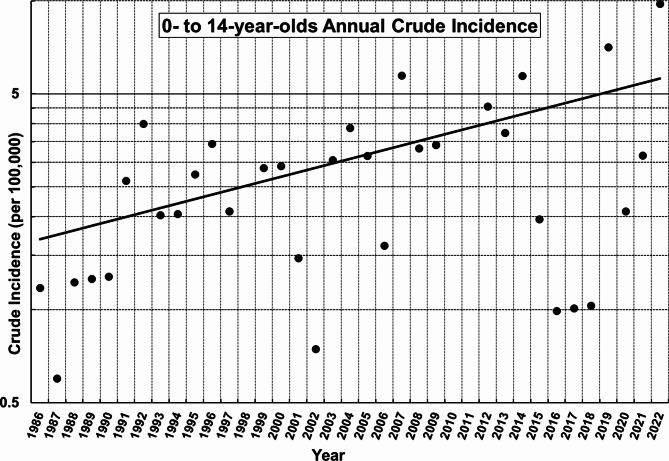

The regression equation for the annual crude incidence, calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program, is as follows: ln(y) = 0.033278⋅x − 65.56357 (x = year, y = Modeled Crude Rate) (Table 1). The annual percentage change (APC) was 3.384% per year (p = .001, 95% CI: 1.550–5.650% per year) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Joinpoint regression analysis of annual crude incidence of type 1 diabetes in children aged 0 to 14 years in Yamanashi Prefecture (1986–2022): No statistically significant joinpoints were detected. The annual percentage change (APC) was 3.384% per year (p = .001, 95% CI: 1.550–5.650% per year). The null hypothesis assumed no change in trends with APC = 0%. The significance level was set at 0.05.

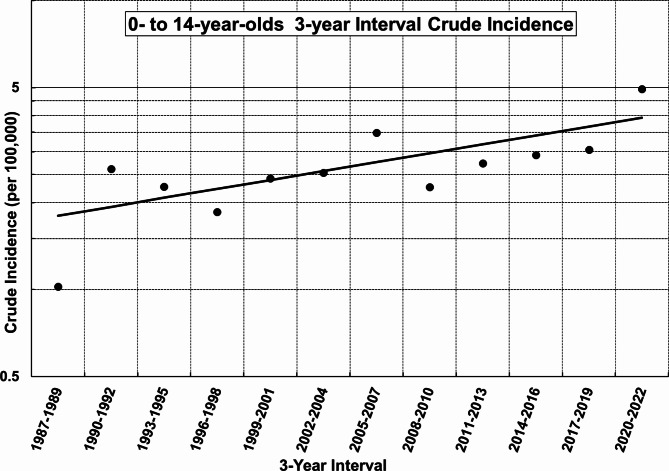

In contrast, the regression equation for the 3-year interval crude incidence was ln(y) = 0.023669⋅x − 46.46633 (x = midpoint year, y = Modeled Crude Rate) (Table 2). The 3-year interval percentage change (3PC) was 2.395% per year (p = .008, 95% CI: 0.642–4.208% per year) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Joinpoint regression analysis of the crude 3-year interval incidence of type 1 diabetes in children aged 0 to 14 years in Yamanashi Prefecture (1987–2022): No statistically significant joinpoints were detected. The 3-year interval percentage change (3PC) was 2.395% per year (p = .008, 95% CI: 0.642–4.208% per year). The null hypothesis assumed no change in trends with 3PC = 0%. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis

During the 2020–2022 COVID-19 pandemic, 21.4% (3 of 14) of new T1D patients presented with DKA at onset, with the following distribution across age groups: one each in the 0–4-year-old, 5–9-year-old, and 10–14-year-old age groups. Compared to the prepandemic period (2012–2019), where 25.9% (7 of 27) of patients presented with DKA, and the distribution indicated a greater frequency in the 10–14-year-old age group (5 patients, see Supplemental Table S1). A χ-squared test was used to assess the difference in the proportion of patients who presented with DKA between these two periods, but no difference was found (p = 1.0).

Discussion

Joinpoint regression analysis

In the joinpoint regression analyses, no statistically significant joinpoints were identified in either the annual or 3-year interval data. These results suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic did not significantly alter the incidence of T1D in Yamanashi Prefecture from 2020 to 2022.

The discrepancy between the APC of 3.384% per year, obtained from the annual joinpoint regression analysis, and the 3PC of 2.395% per year, derived from the 3-year interval joinpoint regression analysis, is likely attributable to annual data variations caused by year-to-year fluctuations and the small number of cases (Fig. 1). Conversely, the limited number of observation points in the 3-year interval data likely influenced the robustness of its analysis (Fig. 2). These factors are thought to have contributed to the observed difference in the rate of increase.

A study of pediatric T1D incidence in Oita Prefecture reported an annual increase in T1D incidence of 4.7% per year20. The difference in the annual increase rates for children aged 0–14 years (< 15 years) between Oita and Yamanashi Prefectures is due to statistical variability, probably caused by the small number of cases in both regions. In fact, the 95% confidence intervals for the annual increase rates in Oita Prefecture (1.7–7.8% per year) and the APC in Yamanashi Prefecture (1.550–5.650% per year) were overlaped, indicating no substantial difference between the two.

Comparative data from South Korea revealed an incidence of 3.70 per 100,000 people in 2008, with an annual increase of 3–4% per year from 2008 to 201421. This suggests that the trends observed in these Japanese prefectures are not significantly different from those observed in South Korea, suggesting the possibility of regional similarities in T1D incidence trends in the Asian region.

Impact during the pandemic in Yamanashi prefecture

Analysis of the crude incidence of T1D among 0- to 14-year-olds from 2020 to 2022 revealed notable fluctuations, with particularly low rates in 2020 and 2021, followed by a significant increase in 2022 (Fig. 1). This trend is consistent with the sharp decline in viral infections during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was attributed to the widespread use of masks and outdoor restrictions. Data from the National Institute of Infectious Diseases in Japan support this observation, showing a marked decrease in reported cases of influenzavirus and most enteroviruses during this period. An exception was coxsackievirus A6 (CVA6), which, despite a decrease in reported cases before the pandemic, increased in 2021 and 2022 (Influenzavirus23, Enterovirus24–27). The potential impact of a small outbreak of coxsackievirus type A6 (CVA6) on the increased incidence of T1D in 2022 was considered. However, despite numerous reports linking coxsackievirus type B (CVB) to the onset of T1D28, there is little evidence to support the involvement of coxsackievirus type A (CVA) in the development of this disease. Therefore, we postulated that the contribution of this small CVA6 outbreak to the increase in T1D incidence in 2022 is likely to be insignificant.

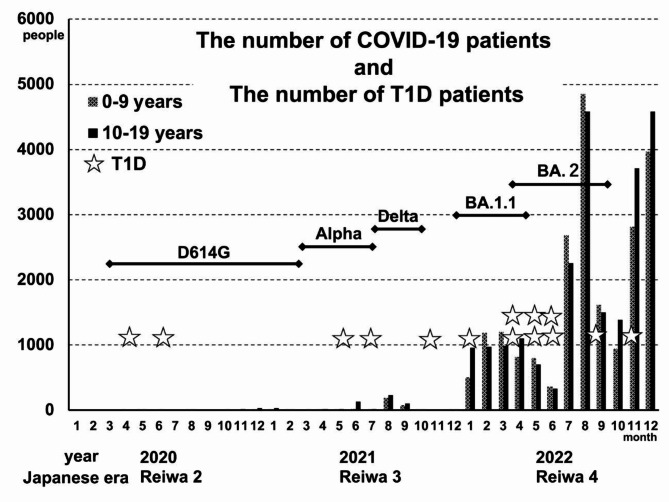

COVID-19 case data from the Yamanashi Prefectural Center for Infectious Diseases revealed a clear pattern in the emergence of COVID-19 cases over the course of the pandemic29. While the number of COVID-19 cases in the prefecture was minimal in 2020 and 2021, a marked increase was observed in 2022 (Japanese era name; Reiwa 4), especially among children and adolescents under 10 years of age, with 4847 and 4586 cases reported in August and 2022, respectively. This increase in COVID-19 cases continued after August, a critical time for public health in our prefecture. When these results are contrasted with the T1D incidences, the distribution of T1D cases in 2022 did not coincide with the timing of the surge in COVID-19 cases. Specifically, there was one patient in January, two each in April, May, and June, one in September, and one in November. This distribution suggested that the increase in the number of pediatric T1D patients in Yamanashi Prefecture preceded the most rapid increase in the number of COVID-19 patients (after July 2022) (Fig. 3). This pattern is similar to observations in Scotland, where no direct correlation was found between the COVID-19 epidemic and the increase in T1D cases30,31.

Fig. 3.

The dotted bars represent the number of COVID-19 patients aged 0–9 years, and the solid bars represent the number of COVID-19 patients aged 10–19 years. One asterisk represents a patient with T1D. D614G, alpha, delta, BA.1.1, and BA.2 represent SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Year-to-year fluctuations in T1D cases in Yamanashi Prefecture have been observed since before the pandemic, suggesting that the fluctuations in T1D incidence from 2020 to 2022 are likely part of a continuing trend rather than a pandemic-induced deviation. This assertion is supported by the timing and nature of the emergence of COVID-19 cases in Yamanashi Prefecture, suggesting that the direct impact of the pandemic on T1D incidence may be limited.

In addition, the analysis of SARS-CoV-2 variants during the pandemic, as reported by the Genome Analysis Center at our institution (Yamanashi Prefectural Central Hospital)32, did not reveal any discernible pattern suggesting a correlation between specific SARS-CoV-2 variants and T1D incidence (Fig. 3). This further supports the notion that the observed increase in T1D cases, especially in 2022, may not be directly attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic or specific viral variants.

Yamanashi Prefecture implemented a state of emergency in response to the COVID-19 pandemic from April 16, 2020, to May 14, 2020, followed by the enforcement of priority measures to prevent the spread of disease from August 20, 2021, to September 12, 2021. Analysis of the number of T1D cases during these periods did not show any significant fluctuations corresponding to these public health measures. This suggests that while measures were critical for controlling the spread of COVID-19, they did not directly affect the incidence of T1D within the prefecture.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses reported an increase in pediatric T1D incidence during the pandemic compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic33,34. As mentioned above, our report, like these reports, showed an increase in average incidence during the pandemic (from 2020 to 2022), but the increase followed the prepandemic trend. This pattern is consistent with observations from Denmark35, Germany36, and Oita Prefecture, Japan20. Denmark also reported that there was no increase in the incidence of T1D within 6 months of SARS-CoV-2 infection37.

DKA during the pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase in the incidence of DKA at the time of initial illness was reported worldwide, possibly because of a decline in hospital functionality and patient reluctance to seek medical care38. However, our analysis in Yamanashi Prefecture reveals a contrasting scenario. In the three-year period from 2020 to 2022, coinciding with the pandemic, there was no significant difference in the number of pediatric patients who presented with DKA at the onset of illness compared with that in the prepandemic period from 2012 to 2019.

This observation is noteworthy in the context of public health responses in larger metropolitan areas, such as Tokyo and Osaka, where states of emergency were declared 4 times and priority preventive measures were implemented 3 or 4 times against COVID-19 from 2020 to 2022. In contrast, Yamanashi Prefecture, with a comparatively smaller population, implemented each measure only once. This suggests that the smaller population size and perhaps more manageable COVID-19 case load in Yamanashi Prefecture facilitated more effective epidemic control, thereby minimizing disruptions to the functioning of the healthcare system and mitigating patients’ reluctance to seek medical care.

As a result, the expected increase in DKA cases at the onset of the outbreak, which is commonly observed in regions with a greater burden on the healthcare system, was not observed in Yamanashi Prefecture. This finding indirectly supports the hypothesis that the observed increase in DKA incidence in other regions may be due to the combined effects of decreased hospital accessibility and patients’ reluctance to seek timely medical intervention.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the small number of T1D patients. This reflects the low incidence of T1D in Japan and the small population of Yamanashi Prefecture. This limitation is important because it may inherently affect the fact that the COVID-19 epidemic had no statistically significant effect on T1D incidence. The inability to measure islet autoantibodies before the onset of T1D and the failure to obtain approval from the ethics committee to track the history of SARS-CoV-2 infection in newly diagnosed patients further limits our understanding. In particular, our insight into the proportion of individuals who develop T1D after SARS-CoV-2 infection is limited, which may obscure the subtle relationship between the pandemic and the incidence of T1D. Additionally, as most cases of FT1D develop in adults, the probability is considered to be extremely low, but it is also a limitation of this study that it is possible that it includes cases diagnosed with FT1D before 2004.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly influenced various aspects of healthcare and disease dynamics. Despite this, the incidence of pediatric T1D among children aged 0–14 years in Yamanashi Prefecture increased during this period, aligning with the pre-pandemic trend. However, due to the limited number of cases analyzed, this study could not definitively determine the direct or indirect effects of the pandemic on T1D incidence. These findings, nonetheless, highlight the importance of adopting a comprehensive perspective to better understand and address the challenges associated with T1D.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Tomohi S, Ko K, and SA designed the study. Hiro Y did the statistical analysis. Tomohi S wrote the manuscript. KoK, KiK, MM, and SA provided clinical advice. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no funding to declare.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Medicine of Yamanashi University (IRB number: 2020–2215, titled “Investigation of the Total Number of Pediatric Patients with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Yamanashi Prefecture”).

Informed consent

All study participants provided informed consent that was obtained in the form of opt-out.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ilonen, J., Lempainen, J. & Veijola, R. The heterogeneous pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.15, 635–650. 10.1038/s41574-019-0254-y (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Redondo, M. J. et al. Genetic determination of islet cell autoimmunity in monozygotic twin, and non-twin siblings of patients with type 1 diabetes: Prospective twin study. BMJ318, 698–702. 10.1136/bmj.318.7185.698 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redondo, M. J. et al. Concordance for islet autoimmunity among monozygotic twins. N Engl. J. Med.359, 2849–2850. 10.1056/nejmc0805398 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hussen, H. I., Moradi, T. & Persson, M. The risk of type 1 diabetes among offspring of immigrant mothers in relation to the duration of residency in Sweden. Diabetes Care. 38, 934–936. 10.2337/dc14-2348 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman, F. R. & Devgan, S. An increase in newly onset IDDM admissions following the Los Angeles earthquake. Diabetes Care. 18, 422. 10.2337/diacare.18.3.422a (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrara, C. T. et al. Excess BMI in childhood: A modifiable risk factor for type 1 diabetes development? Diabetes Care. 40, 698–701. 10.2337/dc16-2331 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, K. et al. Association between Enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes risk: A meta-analysis of 38 case-control studies. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 12, 706964. 10.3389/fendo.2021.706964 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd, R. E., Tamhankar, M. & Lernmark, Å. Enteroviruses and type 1 diabetes: Multiple mechanisms and factors? Annu. Rev. Med.73, 483–499. 10.1146/annurev-med-042320-015952 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyerlein, A., Donnachie, E., Jergens, S. & Ziegler, A. G. Infections in early life and development of type 1 diabetes. JAMA315, 1899–1901. 10.1001/jama.2016.2181 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lönnrot, M. et al. Respiratory infections are temporally associated with initiation of type 1 diabetes autoimmunity: The TEDDY study. Diabetologia60, 1931–1940. 10.1007/s00125-017-4365-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamers, M. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science369, 50–54. 10.1126/science.abc1669 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenblock, C. et al. Viral infiltration of pancreatic islets in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Commun.12, 3534. 10.1038/s41467-021-23886-3 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben Nasr, M. et al. Indirect and direct effects of SARS-CoV-2 on human pancreatic islets. Diabetes71, 1579–1590. 10.2337/db21-0926 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saito, T. et al. Incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes mellitus in Yamanashi Prefecture, Japan, 1986–2018. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab.4, e00214. 10.1002/edm2.214 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imagawa, A. et al. Report of the committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the research of fulminant and acute-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus: New diagnostic criteria of fulminant type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Diabetes Investig. 3, 536–539. 10.1111/jdi.12024 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan (e-Stat). Population by Age (5-Year Group) for Prefectures (as of October 1 of Each Year) - Total population (from 1970 to 2000). [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&data=1&metadata=1&cycle=0&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&tclass1=000000090004&tclass2=000000090005&tclass3val=0&stat_infid=000000090269).

- 17.Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan (e-Stat). Population by Age (Five-Year Groups) for Prefectures (as of October 1 of Each Year) - Total population, Japanese population (from 2000 to 2020). [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=0&tclass1=000000090004&tclass2=000001051180&stat_infid=000013168609&tclass3val=0&metadata=1&data=1).

- 18.Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan (e-Stat), Population by Age (Five-Year Groups) and Sex for Prefectures - Total population, Japanese population, October 1, 2021. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=7&year=20210&month=0&tclass1=000001011679&stat_infid=000032191051&result_back=1&tclass2val=0&metadata=1&data=1).

- 19.Portal Site of Official Statistics of Japan (e-Stat), Population by Age (Five-Year Groups) and Sex for Prefectures - Total population, Japanese population, October 1, 2022. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200524&tstat=000000090001&cycle=7&year=20220&month=0&tclass1=000001011679&stat_infid=000040045496&result_back=1&tclass2val=0&metadata=1&data=1).

- 20.Matsuda, F., Itonaga, T., Maeda, M. & Ihara, K. Long-term trends of pediatric type 1 diabetes incidence in Japan before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep.13, 5803. 10.1038/s41598-023-33037-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim, J. H. et al. Increasing incidence of type 1 diabetes among Korean children and adolescents: Analysis of data from a nationwide registry in Korea. Pediatr. Diabetes. 17, 519–524. 10.1111/pedi.12324 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patterson, C. C. et al. Incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989–2003. Lancet373, 2027–2033. 10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60568-7 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weekly reports of influenza virus isolation/detection. /19–2022/23. (Infectious Agents Surveillance Report: Data based on the reports received before September 1, 2023 from public health institutes), National Insutitute of Infectious Disease, Japan. [cited 2024 21 November] (2018). https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/arc/gv/202223/data2022232e.pdf)

- 24.Weekly reports of major virus isolation/. detection from aseptic meningitis cases, 2018–2022. (Infectious Agents Surveillance Report: Data based on the reports received before December 30, 2022 from public health institutes), National Insutitute of Infectious Disease, Japan. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/arc/gv/2022/data202216e.pdf)

- 25.Weekly reports of enterovirus 71 and group A coxsackievirus 16 isolation/detection. 2018–2022. (Infectious Agents Surveillance Report: Data based on the reports received before December 30, 2022 from public health institutes), National Insutitute of Infectious Disease, Japan. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/arc/gv/2022/data202218e.pdf)

- 26.Weekly reports of. virus isolation/detection from hand, foot and mouth disease cases, 2018–2022. (Infectious Agents Surveillance Report: Data based on the reports received before December 30, 2022 from public health institutes), National Insutitute of Infectious Disease, Japan. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/arc/gv/2022/data202224e.pdf)

- 27.Weekly reports of major coxsackievirus isolation. /detection from herpangina cases, 2018–2022. (Infectious Agents Surveillance Report: Data based on the reports received before December 30, 2022 from public health institutes), National Insutitute of Infectious Disease, Japan. [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/iasr/arc/gv/2022/data202226e.pdf)

- 28.Carré, A. et al. Coxsackievirus and type 1 diabetes: Diabetogenic mechanisms and implications for research. Endocr. Rev.44, 737–751. 10.1210/endrev/bnad007 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamanashi Center for Infectious Disease Control and Prevention (YCDC). Portal site, Analysis and Dissemination Materials (YCDC Report), COVID-19 infection status by age, All Periods (PDF: 337KB) [cited 2024 21 November] (https://www.pref.yamanashi.jp/documents/101638/nendaibetu.pdf).

- 30.McKeigue, P. M. et al. Relationship of incident type 1 diabetes to recent COVID-19 infection: Cohort study using e-health record linkage in Scotland. Diabetes Care. 46, 921–928. 10.2337/dc22-0385 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berthon, W. et al. Incidence of type 1 diabetes in children has fallen to Pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels: A Population-wide analysis from Scotland. Diabetes Care. 47, e26–e28. 10.2337/dc23-2068 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirotsu, Y. et al. Lung tropism in hospitalized patients following infection with SARS-CoV-2 variants from D614G to Omicron BA.2. Commun. Med.3, 32. 10.1038/s43856-023-00261-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hormazábal-Aguayo, I. et al. Incidence of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents under 20 years of age across 55 countries from 2000 to 2022: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev.40, e3749. 10.1002/dmrr.3749 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Souza, D. et al. Incidence of diabetes in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open.6, e2321281. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21281 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noorzae, R. et al. Risk of type 1 diabetes in children is not increased after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A nationwide prospective study in Denmark. Diabetes Care. 46, 1261–1264. 10.2337/dc22-2351 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tittel, S. R. et al. Did the COVID-19 lockdown affect the incidence of pediatric type 1 diabetes in Germany? Diabetes Care. 43, e172–e173. 10.2337/dc20-1633 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bering, L. et al. Risk of New-onset type 1 diabetes in Danish children and adolescents after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A Nationwide, Matched Cohort Study. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J.42, 999–1001. 10.1097/inf.0000000000004063 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elgenidy, A. et al. Incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 124,597 children with diabetes. Pediatr. Res.93, 1149–1160. 10.1038/s41390-022-02241-2 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.