Abstract

Overexpression of the myeloid Src-family kinases Fgr and Hck has been linked to the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Here we characterized the contribution of active forms of these kinases to AML cell cytokine dependence, inhibitor sensitivity, and AML cell engraftment in vivo. The human TF-1 erythroleukemia cell line was used as a model system as it does not express endogenous Hck or Fgr. To induce constitutive kinase activity, Hck and Fgr were fused to the coiled-coil (CC) oligomerization domain of the breakpoint cluster region protein associated with the Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase in chronic myeloid leukemia. Expression of CC-Hck or CC-Fgr transformed TF-1 cells to a granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-independent phenotype that correlated with enhanced phosphorylation of the kinase domain activation loop. Both CC-Hck and CC-Fgr cell populations became sensitized to growth arrest by Src-family kinase inhibitors previously shown to suppress the growth of bone marrow cells from AML patients in vitro and decrease AML cell engraftment in immunocompromised mice. Methionine substitution of the ‘gatekeeper’ residue (Thr338) also stimulated Hck and Fgr kinase activity and transformed TF-1 cells to GM-CSF independence without CC fusion. TF-1 cells expressing either active form of Hck or Fgr engrafted immunocompromised mice faster and developed more extensive tumors compared to mice engrafted with the parent cell line, resulting in shorter survival. Expression of wild-type Hck also significantly enhanced bone marrow engraftment without an activating mutation. Reverse phase protein array analysis linked active Hck and Fgr to the mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1/p70 S6 ribosomal protein (mTORC-1/S6) kinase and focal adhesion kinase (Fak) signaling pathways. Combining Hck and Fgr inhibitors with existing mTORC-1/S6 kinase or Fak inhibitors may improve clinical responses and reduce the potential for acquired resistance.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-83740-6.

Introduction

While acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is associated with complex genetic changes, dysregulation of protein-tyrosine kinase signaling is a common feature providing avenues for precision therapy. For example, mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 (Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3) induce constitutive kinase activity sufficient to drive leukemogenesis1. Common Flt3 mutations include internal tandem duplication (ITD) in the regulatory juxtamembrane region or point mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain2,3. Flt3 inhibitors have shown promise in clinical trials, although acquired resistance arising through mutations in the drug binding site has limited their clinical efficacy4–6.

AML cells often overexpress members of the Src tyrosine kinase family, including Hck and Fgr7,8, and high levels of these myeloid Src-family kinases correlate with poor clinical outcomes9. Hck and Fgr are normally expressed in mature macrophages, granulocytes and B-cells, where they regulate diverse pathways involved in innate immunity and inflammation10–12. Previous work has shown that Hck is also strongly expressed in leukemia stem cells from AML patients and that knockdown of Hck expression suppressed the growth of AML blast cells13. Along similar lines, the pyrrolopyrimidine Src-family kinase inhibitor A-419259 (also known as RK-20449) eradicated AML patient xenografts in immunocompromised mice13. Subsequent work has shown that A-419259 is also an inhibitor of Flt3 kinase activity in vitro9 suggesting that its activity against multiple AML-associated tyrosine kinases may account for its efficacy against primary patient cells in the mouse xenograft model14. Newer work has linked Fgr to AML as well. Unlike Hck, ectopic expression of wild-type Fgr induces oncogenic transformation of rodent fibroblasts and reduces the cytokine requirement for myeloid cell survival in vitro15. Previously, we reported the discovery of TL02-59, an N-phenylbenzamide ATP-site inhibitor of Fgr that blocked the growth and induced apoptosis of AML cell lines with single-digit nM potency16. TL02-59 induced growth arrest in patient AML bone marrow samples, with Fgr and Hck expression levels correlating strongly with TL02-59 sensitivity16. Patient-derived AML bone marrow cell responses to TL02-59 were independent of Flt3 expression and mutational status, with the four most sensitive patient samples wild-type for Flt3. Oral administration of TL02-59 for just three weeks eliminated the human AML cell line MV4-11 from the spleen and peripheral blood in a mouse model of AML, while dramatically suppressing bone marrow engraftment16. These results demonstrate that inhibitors targeting Hck and Fgr may provide clinical benefit in AML patients that over-express these Src-family members.

While inhibitor efficacy against AML cell lines and patient samples collectively identifies myeloid Src-family members as drug targets in AML, the contributions of individual family members to the transformed phenotype is less clear. In this study, we explored the oncogenic potential of Fgr and Hck kinase activity following expression in the human cytokine-dependent cell line, TF-1, which does not express either kinase. To mimic the constitutive activation of Hck and Fgr observed in AML cells, we fused the N-terminus of each kinase to the 70 amino acid coiled coil (CC) domain of the Breakpoint Cluster Region (BCR) protein17. BCR-CC fusion enhanced both Fgr and Hck autophosphorylation following expression in TF-1 cells and was sufficient to induce cytokine-independent survival and proliferation in vitro. Cells expressing each of these active kinases also exhibited enhanced sensitivity to both A-419259 and TL02-59, demonstrating acquired dependence on the active kinase for cytokine-independent growth. Cells expressing active CC-Fgr and CC-Hck showed more rapid tumor growth in immunocompromised mice compared to the wild-type cells, suggesting a direct contribution of these Src-family members to enhanced growth in vivo. To determine whether this gain of function was independent of the CC domain fusion, Fgr and Hck were also activated by an alternative mechanism in which the gatekeeper threonine residue in the kinase domain was replaced with methionine (T338M mutant). Both Fgr-T338M and Hck-T338M also transformed TF-1 cells to cytokine independence in vitro and enhanced bone marrow engraftment in vivo as did cells expressing wild-type Hck. Mice engrafted with TF-1 cells expressing either active kinase showed significantly reduced survival compared to mice engrafted with the parental cell line. Proteomics studies showed that active Hck and Fgr influenced the mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1/p70 S6 ribosomal protein kinase (mTORC1-S6K) and focal adhesion kinase (Fak) signaling pathways, both of which have been independently linked to AML progression. These results demonstrate that constitutive activation of Fgr or Hck is sufficient to generate signals for AML cell expansion in vitro and tumor burden in vivo, supporting continued development of inhibitors for these kinases for AML therapy. Combination with established inhibitors for Fak or mTORC signaling may enhance anti-AML efficacy and reduce the potential for acquired resistance.

Results and discussion

Coiled-coil domain fusion and gatekeeper mutation release Fgr and Hck transforming potential in myeloid cells

To explore the individual roles of Fgr and Hck in AML cell growth, we chose the human TF-1 cell line as a model system. These cells, originally derived from a patient with erythroleukemia, require the cytokines GM-CSF, IL-3, or erythropoietin to sustain growth in culture18. Previous studies have shown that expression of oncogenic tyrosine kinases associated with myeloid leukemias, including Bcr-Abl19 and Flt3-ITD9, induce cytokine independence in these cells, suggesting that active Src-family kinases may influence their cytokine dependence as well.

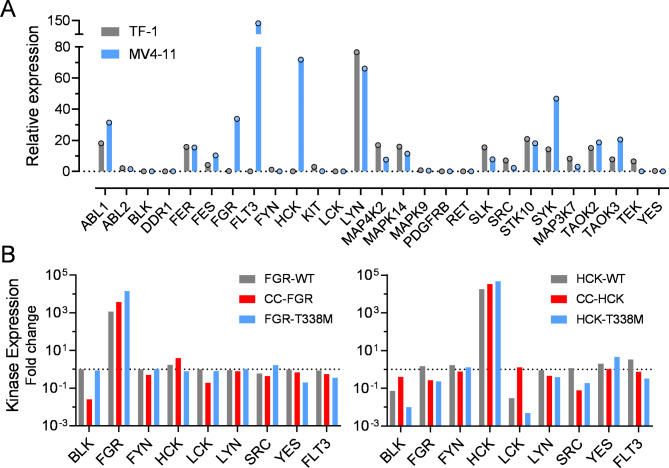

First, we profiled the relative expression of 27 protein kinases previously identified as likely targets for inhibition by TL02-5916 and A-4192599 using quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR; Fig. 1A). This analysis revealed undetectable levels of Hck and Fgr transcripts in the parental TF-1 cell line. The absence of endogenous Fgr and Hck expression, along with their cytokine dependence for growth, makes TF-1 cells an ideal system to study the individual effects of these Src-family kinases on cellular growth and survival both in vitro and in vivo. As a positive control, target kinase transcripts were also assessed in the AML cell line MV4-11, which expresses the Flt3-ITD oncogene. These cells also express relatively high levels of Fgr and Hck and are very sensitive to growth suppression by both A-4192599 and TL02-5916.

Fig. 1.

Transcription profiles of Src-family kinase expression in cell lines used in this study. (A) Relative mRNA expression profiles of A-419259 and TL02-59 target kinases previously identified by KINOMEscan analysis were determined for the AML cell lines TF-1 and MV4-11 by qPCR. ΔCt values for each kinase relative to GAPDH were determined first. To generate the expression profiles, the average ΔCt value for all kinases in each cell line was subtracted from each individual ΔCt value and the base 2 antilog of the resulting ΔΔCt values were plotted as shown. Each data point represents the average of three independent determinations. (B) Profiling of all eight Src-family kinases and Flt3 expression in TF-1 cell populations transduced with wild-type (WT), coiled-coil (CC) fusions, and gatekeeper mutants (T338M) of FGR (left) and HCK (right). Using the same qPCR primer–probe sets from panel A, ΔCt values for each kinase relative to GAPDH were determined for each of the indicated cell populations. The corresponding ΔCt value for parental TF-1 cells (from part A) was subtracted from each of these ΔCt values and the base 2 antilog of the resulting ΔΔCt values were plotted as fold change relative to the TF-1 parent cells. The dotted line indicates the basal expression level in the parental TF-1 cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the bar height indicate the resulting mean values.

Previous work from our group showed that expression of wild-type Fgr or Hck alone was not sufficient to transform TF-1 cells to cytokine independence in cell culture9,15. Therefore, to induce constitutive activation of Fgr and Hck, we fused each kinase to the N-terminal 70 amino acids of Bcr, which encodes a coiled-coil (CC) oligomerization domain17. Fusion of the Bcr CC domain contributes to the activation of Abl kinase in the context of Bcr-Abl, the transforming tyrosine kinase responsible for chronic myeloid leukemia20. We reasoned that CC fusion may produce a similar outcome with Src-family kinases, which share a core domain structure with Abl consisting of SH3, SH2 and kinase domains21,22. A molecular model of the CC-Fgr fusion protein is presented in Fig. 2A. This model is based on a recent X-ray crystal structure of the Fgr core region (SH3, SH2 and kinase domains; PDB ID: 7UY0) which forms a homodimer with the activation loop tyrosine of one monomer inserted into the active site of the other23. This homodimer is trapped in the dimeric state by the presence of the ATP-site kinase inhibitor, A-419259, providing a potential snapshot of autophosphorylation in progress. Fusion of the antiparallel coiled-coil domain of Bcr, modeled on its crystal structure (PDB ID: 1K1F)17, may promote homodimer formation and autophosphorylation.

Fig. 2.

Molecular model of a CC-Fgr fusion protein and binding modes for the Src-family kinase inhibitors, A-419259 and TL02-59. (A) Hypothetical structural model of a Src-family kinase-coiled-coil (CC) fusion protein. The N-terminal 70 amino acid CC domain of BCR was fused to the N-terminal end of Fgr (shown) and Hck. Model is based on the X-ray crystal structure of near-full-length Fgr bound to the ATP-site inhibitor A-419259 (not shown in model). In this structure, Fgr forms a homodimer with the kinase domain activation loop of one monomer (kinase-2; green) engaging the active site of the other (kinase-1; grey). Also shown are the SH3 (red) and SH2 (blue) domains, the SH2-kinase linker (orange) and the negative regulatory tail (cyan). The unique domain is unstructured (dotted line). The model was produced using PyMol (Schrödinger) and the PDB coordinates for the BCR CC domain (PDB ID: 1K1F) and Fgr (PDB ID: 7UY0). (B, C) ATP-site inhibitors A-419259 and TL02-59 induce distinct conformations of the Fgr kinase domain. Overall kinase domain structures are shown at left, with close-up views of the binding sites at right. A-419259 induces outward rotation of the N-lobe αC-helix (blue), with the DFG motif (orange) flipped inward. TL02-59 causes inward rotation of αC-helix with the DFG motif flipped outward. In both cases, the gatekeeper residue (T338) makes direct contact with the inhibitor; both ligands also interact with hinge residues connecting the N- and C-lobes of the kinase domain (E339 and M341). Models produced with PyMol and crystal coordinates for near-full-length Fgr bound to A-419259 (PDB ID: 7UY0) or TL02-59 (PDB ID: 7UY3).

As an alternative mechanism of kinase activation, we also created kinase domain ‘gatekeeper’ mutants of Fgr and Hck. The gatekeeper mutation replaces Thr338 in the kinase domain with methionine (referred to here as T338M or TM; amino acid numbering as per the crystal structure of Src; PDB ID: 2SRC24). X-ray crystallography of a similar mutation in Src has been shown to induce kinase activation by optimizing the coordination of ATP in the active site and stabilizing the ‘hydrophobic spine’ associated with the active conformation25. The gatekeeper residue is adjacent to the ATP-binding site of Fgr and Hck, where it makes direct polar contacts with the ATP-site inhibitors A-419259 and TL02-59 (modeled in Fig. 2B and C). While the T338M substitution activated both Fgr and Hck as described below, it also resulted in resistance to both inhibitors as expected from the crystal structures.

Both modified versions of Fgr and Hck (CC fusions and T338M gatekeeper mutants) were then introduced into TF-1 cells by retroviral transduction followed by puromycin selection. As additional controls, we also produced TF-1 cell populations expressing the wild-type forms of each kinase. All six transduced cell populations, as well as the parental cell line, were then tagged with the near-infrared fluorescent protein 720 (iRFP720) and luciferase for subsequent cell sorting and in vivo imaging of tumor cell growth, respectively. The cell populations were then examined for Src-family kinase and Flt3 transcripts by qPCR. Each population showed enhanced expression of Hck and Fgr transcripts as expected relative to the parental cell line with negligible changes to other Src-family kinase levels (Fig. 1B).

Each TF-1 cell population was then assayed for cytokine independent growth. Parental TF-1 cells, as well as cells expressing wild-type Fgr, failed to grow in the absence of GM-CSF as observed previously9 (Fig. 3), while cells expressing wild-type Hck grew very slowly in the absence of cytokine. In contrast, expression of the CC fusions or the gatekeeper mutants of either Fgr or Hck induced cytokine-independent proliferation of TF-1 cells, which grew equally well in the presence or absence of GM-CSF. As a positive control, we also transduced TF-1 cells with Flt3-ITD, which supported cytokine-independent growth as expected. This result shows that CC fusion and gatekeeper mutation both allow Hck and Fgr to support the GM-CSF-independent growth and survival of this AML cell line.

Fig. 3.

Active forms of Fgr and Hck induce cytokine-independent growth of TF-1 myeloid cells. The human erythroleukemia cell line TF-1 was transduced with recombinant retroviruses carrying wild-type (WT) full-length Fgr and Hck as well as coiled-coil (CC) fusions and kinase domain gatekeeper mutants (T338M). Cells transduced with Flt3-ITD were included as a positive control. Cell growth was monitored over four days using the Cell Titer-Blue cell viability assay (Promega). All time points were assayed in triplicate and the mean fluorescence value, corrected for background, is shown ± SE (in most cases the error bars are smaller than the data points).

We next assessed the effect of CC fusion and gatekeeper mutation on Fgr and Hck autophosphorylation in TF-1 cells. Wild-type and mutant forms of each kinase were immunoprecipitated from the transduced cell populations followed by immunoblotting with phosphospecific antibodies to the activation loop tyrosine (pTyr416) as well as each kinase to control for protein recovery. Controls included parental TF-1 cells as well as cells expressing wild-type Hck and Fgr. Representative immunoblots are shown in Fig. 4A and quantitation is shown as the ratio of the pTyr416 to kinase protein band intensities for replicate blots in Fig. 4B. (Uncropped images of the immunoblots are provided in Figure S1.) Wild-type Fgr and Hck both showed constitutive autophosphorylation following over-expression in TF-1 cells, consistent with previous results16. CC domain fusion further enhanced autophosphorylation of Hck by about twofold and Fgr by about fourfold, with lower enhancement observed for the gatekeeper mutants. These results demonstrate that both modifications enhance kinase activity, which may in part account for the ability of the active forms to drive cytokine-independent proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Protein levels and autophosphorylation of Fgr and Hck following expression in TF-1 cells. TF-1 cells expressing wild-type (WT), CC fusion, or gatekeeper mutant (T338M) forms of Fgr or Hck were lysed and kinase proteins isolated by immunoprecipitation. Aliquots of each immunoprecipitate were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed for kinase activation loop autophosphorylation (pTyr416) and kinase protein expression. Immunoreactive bands were quantified with secondary antibodies tagged with infrared dyes and imaged using the LI-COR Odyssey platform. Parent TF-1 cells were also analyzed as a negative control. Each condition includes at least four biological replicates. (A) Representative blot images, with molecular weight (MW) markers indicated in kDa. Uncropped images are provided in the Supplemental Information, Figure S1. (B) Ratios of pTyr416 to kinase expression band intensities were determined for each replicate and average ratio is shown as the bar height ± SE. The individual data points are also shown.

Src-family kinases are characterized by non-catalytic SH2 and SH3 domains, which contribute to the regulation of kinase activity and recruit substrate proteins involved in signal transduction. Crystal structures of both Hck26 and Fgr23 show that the SH3-SH2 regulatory unit engages the back of the kinase domain, potentially suppressing interaction with cellular signaling partners and regulating kinase activity in the case of Hck27. To explore whether CC fusion or gatekeeper mutation affected the overall conformation of Hck and Fgr in TF-1 cells, we performed an SH3 domain capture assay. For these experiments, a biotinylated 12-amino-acid SH3 domain peptide ligand known as VSL1228 was immobilized on magnetic beads and mixed with lysates from each of the TF-1 cell populations expressing the wild-type kinases as well as the two active variants. Following incubation and washing, associated kinases were eluted and detected by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 5, binding of both CC-Hck and CC-Fgr to the VSL12-loaded beads was significantly enhanced compared to the wild-type kinases, indicating that CC fusion induces an open conformation with the SH3 domain exposed for partner protein engagement. Alternatively, or in addition, release of SH3 from the SH2-kinase linker may also allosterically influence substrate selection by the kinase domain as suggested by earlier work29. The gatekeeper mutants, on the other hand, showed similar engagement with the immobilized SH3 ligand as wild-type, suggesting that the activating effects of the gatekeeper mutation are limited to the kinase domain and not allosterically transmitted to the regulatory domains. (Uncropped images of the immunoblots are provided in Figure S2.)

Fig. 5.

Coiled-coil fusion induces an open conformation of Fgr and Hck. A biotinylated SH3 domain capture peptide (VSL12; amino acid sequence VSLARRPLPPLP) was immobilized on streptavidin-coated magnetic beads and incubated with clarified cell lysates from each of the TF-1 cell populations shown. Following incubation and washing, associated kinase proteins were detected by immunoblotting and quantified using the LICOR Odyssey imaging system. Aliquots of each lysate were included on the blots for normalization. Lysates were also incubated with the beads in the absence of the peptide to control for non-specific binding. (A) Representative immunoblots show the expression level in the lysate (Input), captured kinase proteins (VSL12), and non-specific binding to the beads (Control) for each of the six cell populations. Uncropped images are provided in the Supplemental Information, Figure S2. (B) Quantitation of the results from three (Hck) or four (Fgr) independent determinations. The fluorescence intensity of the captured kinases was corrected for non-specific binding and normalized to the intensity of the input protein in each case. Bar heights show the mean normalized intensity ± SE and statistical comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA; *p < 0.05; ns, not significant.

TF-1 cells transformed to cytokine independence by active Fgr and Hck are sensitized to Src-family kinase inhibitors

Src-family kinase inhibitors with activity against Fgr and Hck have shown promise in preclinical models of AML (see Introduction). These compounds include the pyrrolopyrimidine A-419259 and the N-phenylbenzamide TL02-59, both of which occupy the ATP binding site in the kinase domain. Recent crystal structures of Fgr bound to each of these inhibitors23 revealed that A-419259 stabilizes an αC-helix-out/Asp-Phe-Gly (DFG) motif-in conformation, while TL02-59 binds in the αC-helix-in/DFG-out ‘Type II’ mode (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, TL02-59 was shown to cause allosteric displacement of the SH3 and SH2 domains from their negative regulatory positions on the back of the kinase domain, while A-419259 increased the stability of the closed kinase conformation23.

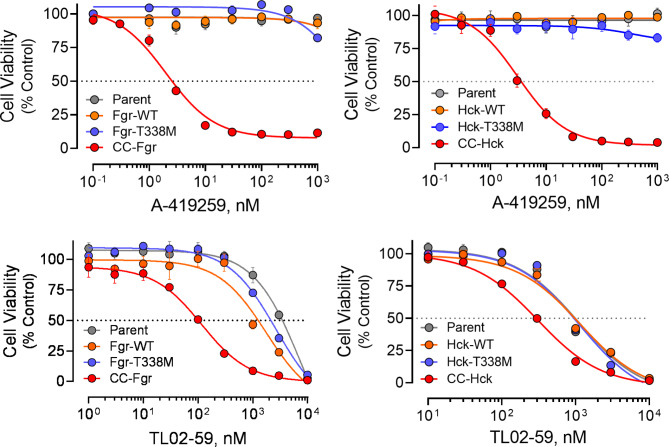

Transformation of TF-1 cells by active Hck and Fgr to cytokine independence suggested that these cells now require the activity of these kinases for growth and should therefore show sensitivity to A-419259 and TL02-59. To test this idea, TF-1 cells expressing the Fgr and Hck CC fusions, the T338M gatekeeper mutants, the wild-type kinases, as well as the parental cells were incubated in the presence of each inhibitor over a broad range of concentrations and cell viability was assessed 48 h later. The resulting concentration–response curves are shown in Fig. 6 and the IC50 values are summarized in Table 1. Cytokine-independent TF-1 cells expressing CC-Fgr and CC-Hck, both of which retain a wild-type kinase domain, were remarkably sensitive to growth suppression by A-419259 in the absence of GM-CSF, with IC50 values of 2.0 nM and 3.1 nM, respectively. In contrast, cells expressing the corresponding wild-type kinases as well as the parent cell line, both of which still require GM-CSF for growth, were more than 1,000-fold less sensitive. TL02-59 treatment also selectively inhibited CC-Fgr and CC-Hck cell proliferation, with IC50 values of 116 and 308 nM, respectively. The potency of TL02-59 was lower than that previously reported for other AML cell lines16 which may reflect the impact of coiled-coil fusion on overall kinase conformation as shown by SH3 domain capture assay (Fig. 5). TL02-59 binds to the active site of Fgr in a Type II manner, a conformation which may be more sensitive to allosteric effects23. TF-1 cells transformed with the gatekeeper mutants of Fgr and Hck were completely resistant to both inhibitors as expected. This result is consistent with the X-ray crystal structures, which demonstrate that the gatekeeper threonine forms critical hydrogen bonds with both inhibitors (Fig. 2B and 2C)23,30.

Fig. 6.

Expression of CC-Fgr and CC-Hck sensitizes TF-1 cells to growth suppression by the Src-family kinase inhibitors, A-419259 and TL02-59. TF-1 cells expressing wild-type (WT), CC fusion, or gatekeeper mutant (T338M) forms of Fgr (left panels) or Hck (right panels), as well as the parent cell line, were treated with A-419259 (upper panels) or TL02-59 (lower panels) over the range of concentrations shown. Following 72 h incubation, cell viability was assessed with the Cell Titer-Blue assay (Promega). Data are expressed as percent viability of cells treated with the DMSO carrier solvent alone (0.1%). All conditions were measured at least in triplicate, and each data point indicates the mean value ± SE. Inhibitor IC50 values determined by non-linear regression analysis are presented in Table 1. Note that TF-1 parent cells, as well as cells expressing the wild-type kinases, are cultured in the presence of GM-CSF while cells expressing the active kinases (CC fusions and T338M gatekeeper mutants) are not.

Table 1.

TF-1 cells expressing active forms of Fgr and Hck are sensitized to the Src-family kinase inhibitors A-419259 and TL02-59.

| Cell population | A-419259, IC50 (nM) | TL02-59, IC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| Parent | > 3,000 | 1108 |

| Hck wild-type | > 3,000 | 1155 |

| Hck-T338M | > 3,000 | 1151 |

| CC-Hck | 3.1 | 308 |

| Parent | > 3,000 | > 3,000 |

| Fgr wild-type | > 3,000 | 1759 |

| Fgr-T338M | > 3,000 | 2658 |

| CC-Fgr | 2.0 | 116 |

Cells were treated over a range of inhibitor concentrations and cell viability was monitored with the Cell Titer-Blue fluorometric assay. The resulting concentration–response curves (Fig. 6) were best-fit by non-linear regression analysis to determine the IC50 values shown.

We also explored whether GM-CSF could rescue the sensitivity of TF-1 cells expressing active Fgr or Hck to A-419259 treatment. TF-1 cells expressing either CC-Hck or CC-Fgr were cultured in presence or absence of GM-CSF for several passages, treated with A-419259, and assayed for viability 72 h later. Cells grown in the absence of GM-CSF remained very sensitive to A-419259 treatment, with IC50 values in the single-digit nM range as before. In the presence of GM-CSF, however, the CC-Hck and CC-Fgr cell populations behaved differently. Cells expressing CC-Hck were partially rescued from A-419259-induced cytotoxicity by GM-CSF, with approximately 50% of the population showing reduced viability (Figure S3A). On the other hand, GM-CSF rescued TF-1/CC-Fgr cells from A-419259 growth suppression by about 80% (Figure S3B), suggesting that active Hck generates a stronger signal for cell growth. This difference is consistent with signaling data for each kinase presented below.

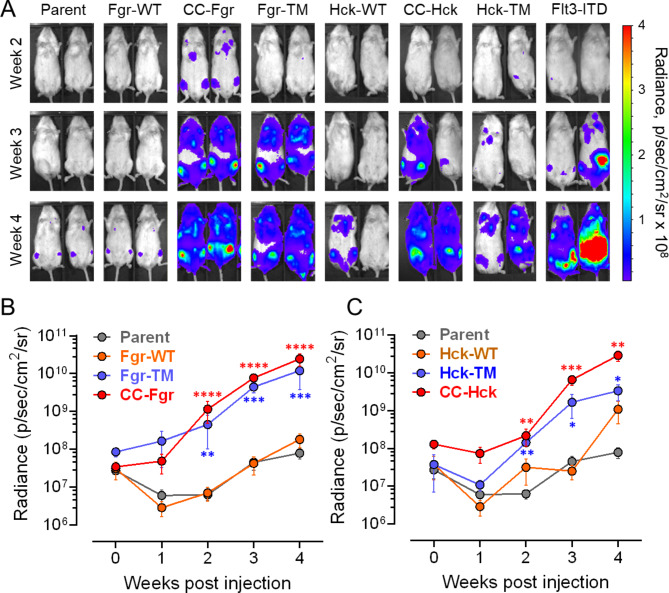

Expression of active Fgr and Hck enhances TF-1 myeloid cell growth in vivo

Previous work has shown that A-419259 and TL02-59 suppress the growth of AML cell lines and patient cells following oral administration to engrafted mice, suggesting that Src-family kinase activity contributes to AML progression in vivo (see Introduction). These observations predicted that expression of active Fgr or Hck may provide a growth advantage to TF-1 cells following engraftment. To test this idea, parental TF-1 cells as well as cell populations expressing wild-type, CC fusions and gatekeeper mutants of Hck and Fgr were tagged with luciferase and injected into the tail vein of immunocompromised mice. Growth of each cell population was monitored by in vivo imaging each week for a total of four weeks. Parental TF-1 cells, as well as cells expressing wild-type Fgr, showed relatively slow engraftment, with weak luciferase signals present in the femur after four weeks (Fig. 7A and B). Mice engrafted with cells expressing wild-type Hck showed more variability, with some animals showing higher levels of engraftment by 4 weeks (Fig. 7A and C). In contrast, cells expressing either active form of Fgr or Hck showed rapid growth in vivo, with signals observed as early as 2 weeks post-engraftment that steadily progressed over the four-week period. As a positive control, mice engrafted with TF-1 cells expressing Flt3-ITD were also monitored and showed in vivo expansion comparable to that observed with the active forms of Hck and Fgr (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Expression of active forms of Fgr and Hck accelerates AML engraftment in vivo. Immunocompromised (NSG) mice were injected with equal numbers of parental TF-1 cells (Parent) or cells expressing wild-type (WT), CC fusion, or gatekeeper mutant (TM) forms of Fgr or Hck (5 or 6 animals per group). Cells transformed with Flt3-ITD were included as a positive control. Each cell line was also tagged with luciferase to allow in vivo imaging of tumor growth. Mice were imaged immediately following cell injection and weekly for 4 weeks. (A) Representative images of two mice from each group. The radiance scale is shown on the right. (B, C) Quantitative analysis of tumor growth over time based on in vivo image analysis of luciferase activity (B, Fgr cells; C, Hck cells). Statistical comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA following Log10 transformation of the radiance values. Significant differences were observed between the parent and active kinase-expressing cell populations at 2, 3, and 4 weeks (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001). The parent control values are the same on each graph.

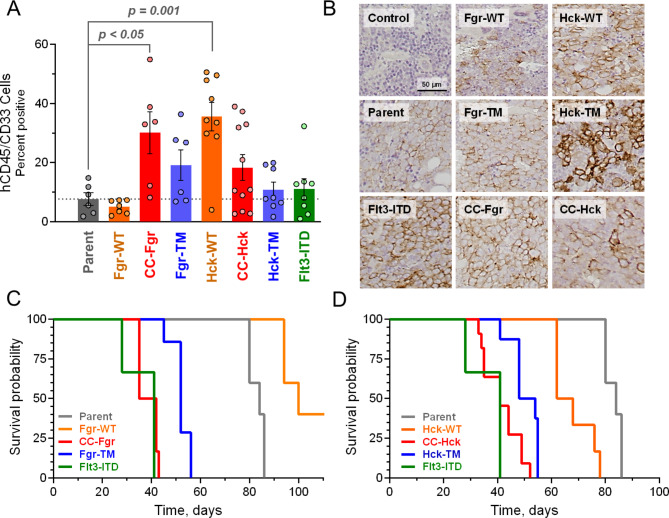

Following four weeks of engraftment, the mice were sacrificed and blood, bone marrow and spleen samples were analyzed by flow cytometry for the presence of TF-1 cells, identified as double positive for human cell-surface CD33 and CD45 expression (Fig. 8A). Mice injected with TF-1 cells expressing CC-Fgr, Fgr-TM, CC-Hck, and Hck-TM showed higher average bone marrow engraftment compared to the parent TF-1 cells, with the CC-Fgr group reaching statistical significance (p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA). Surprisingly, mice injected with cells expressing wild-type Hck also showed significant bone marrow engraftment compared to the parent cells (p = 0.001), unlike the wild-type Fgr group. These data demonstrate that overexpression of wild-type Hck is sufficient to enhance bone marrow engraftment of a human AML cell line in a mouse model. Further studies will be required to determine whether this effect is due to enhanced kinase activity, recruitment of leukemogenic signaling partners, or both, specifically in the bone marrow environment. Flt3-ITD-transformed cells were only enhanced slightly in the bone marrow, suggesting that active Flt3 alone may not be sufficient to induce leukemia cell retention in this compartment. However, Flt3-ITD caused TF-1 cells to grow faster in other organs based on the overall tumor burden observed by in vivo imaging (Fig. 7A). Unlike the bone marrow, no significant differences were observed in the number of TF-1 cells from any of the groups in the spleen or peripheral blood after 4 weeks (data not shown). These findings demonstrate that either Fgr or Hck activity alone is sufficient to enhance engraftment and expansion of a human AML cell line in bone marrow, and in the case of Hck, overexpression without mutation is sufficient to produce this result. Immunohistochemistry confirmed leukemic cell infiltration of the bone marrow (Fig. 8B) as well as additional tissues including the brain and ovaries (data not shown) which may model other AML-related tumors such as myeloid sarcoma31,32.

Fig. 8.

Active forms of Fgr and Hck promote bone marrow engraftment and reduce survival of NSG mice. Immunocompromised (NSG) mice were injected with equal numbers of control TF-1 cells (Parent) or cells expressing wild-type (WT), CC fusion, or gatekeeper mutant (TM) forms of Fgr or Hck. Cells transformed with Flt3-ITD were included for comparison. Four weeks after cell injection, mice were sacrificed and spleen, bone marrow and peripheral blood were analyzed for the presence of TF-1 cells by flow cytometry with antibodies specific for human cell surface CD45 and CD33. (A) Flow cytometry result for bone marrow cells. Each dot represents one mouse. Bar heights indicate the average percentage of human cells present ± SE. The dotted line indicates the extent of engraftment of parent TF-1 cells. Statistical analysis between all groups was evaluated by one-way ANOVA. (B) Representative thin sections of bone marrow from the groups shown in part A. Human TF-1 cells were visualized by immunohistochemistry with an antibody specific for human CD45. (C, D) Kaplan-Meyer analysis of groups of mice injected with each cell line as indicated. Results from the control groups (Parent, Flt3-ITD) are shown on both panels for comparison. The study ended at 120 days.

We also explored the effects of Fgr and Hck expression on the overall survival of engrafted mice. Groups of mice were injected with parental TF-1 cells as well as cells expressing the wild-type and active forms of either Fgr or Hck. Mice injected with TF-1 cells transformed with Flt3-ITD were included as a positive control. Mice engrafted with CC-Fgr or Flt3-ITD cells showed almost identical survival curves, with all mice succumbing to disease by 45 days. Mice engrafted with Fgr-T338M cells survived somewhat longer, with all mice succumbing by day 56 (Fig. 8C). In contrast, mice injected with parental cells or cells expressing wild-type Fgr survived almost twice as long. Similar results were observed with mice engrafted with CC-Hck and Hck-T338M cells (Fig. 8D). Interestingly, mice injected with cells expressing wild-type Hck also showed reduced survival compared to the parental cell group, although the rate of loss was slower than that observed with cells expressing the active forms of Hck. This effect of wild-type Hck on survival may relate to the enhanced bone marrow engraftment observed with these cells.

At the end of the survival study, in vivo images of the animals injected with the parental cell line as well as cells expressing the wild-type kinases indicated that tumors developed not only in the bone marrow but also in several other sites (Figure S4A). To explore this issue further, we measured the spleen length for all animals in the survival study as an estimate of splenomegaly (Figure S4B) and counted the number of tumor sites observed in all animals that were present outside of the bone marrow and spleen (Figure S4C). Some or all animals in each group showed splenomegaly, except for mice engrafted with CC-Hck cells. However, more than half of the mice in this group exhibited tumors outside of the bone marrow and spleen, which may account in part for the poor survival of these animals. All mice engrafted with cells expressing wild-type Hck, on the other hand, showed splenic enlargement, but only one of the nine animals in this group exhibited tumors outside of the bone marrow. These observations support the conclusion that over-expression of wild-type Hck, a common finding in AML9, primarily promotes survival and growth of AML cells in the bone marrow environment. All Flt3-ITD positive control animals showed some degree of splenic enlargement as well as tumor formation outside of the bone marrow, which may account for their poor survival as well.

Comparison of Fgr and Hck signaling profiles by reverse-phase protein array (RPPA) analysis

Fgr and Hck are often over-expressed in primary AML cells and their transcript levels are closely correlated9. In addition, their structures and regulation are similar, raising the question of whether they trigger redundant or discrete signaling pathways to drive AML cell growth. To address this question, we took advantage of the observation that TF-1 cells transformed with active forms of Fgr and Hck become remarkably sensitive to the kinase inhibitor, A-419259, with a greater than 3-log difference in IC50 values between the parental and kinase-transformed cell lines (Fig. 6 and Table 1). Cells transformed with gatekeeper mutants of Hck and Fgr are completely resistant to A-419259, providing strong evidence for exclusive on-target activity. These observations supported the use of A-419259 as a selective chemical probe to explore signaling events driven by active Hck and Fgr in the transformed cell populations.

TF-1 cells transformed with either CC-Fgr or CC-Hck were treated with A-419259 at a final concentration of 300 nM with parallel cultures left untreated for comparison. This inhibitor concentration causes complete suppression of transformed cell growth without affecting the parent cells or cells expressing the inhibitor-resistant gatekeeper mutants of each kinase (Fig. 6). Cells were treated for 16 h at which point viability was still > 90% by trypan blue exclusion, indicating that this relatively short-term exposure to the inhibitor induced growth arrest without apoptosis. Pellets from each pair of cells were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and shipped to the MD Anderson Cancer Center for RPPA analysis. Cells were then lysed under denaturing conditions, and serial dilutions were arrayed on nitrocellulose-coated slides to identify a linear range for accurate quantitation. Approximately 500 replicate arrays were generated, and each array was probed with a separate antibody. The panel of antibodies defines a wide range of signaling proteins and includes many phosphospecific antibodies targeting kinase signaling pathways (see Materials and Methods for more details).

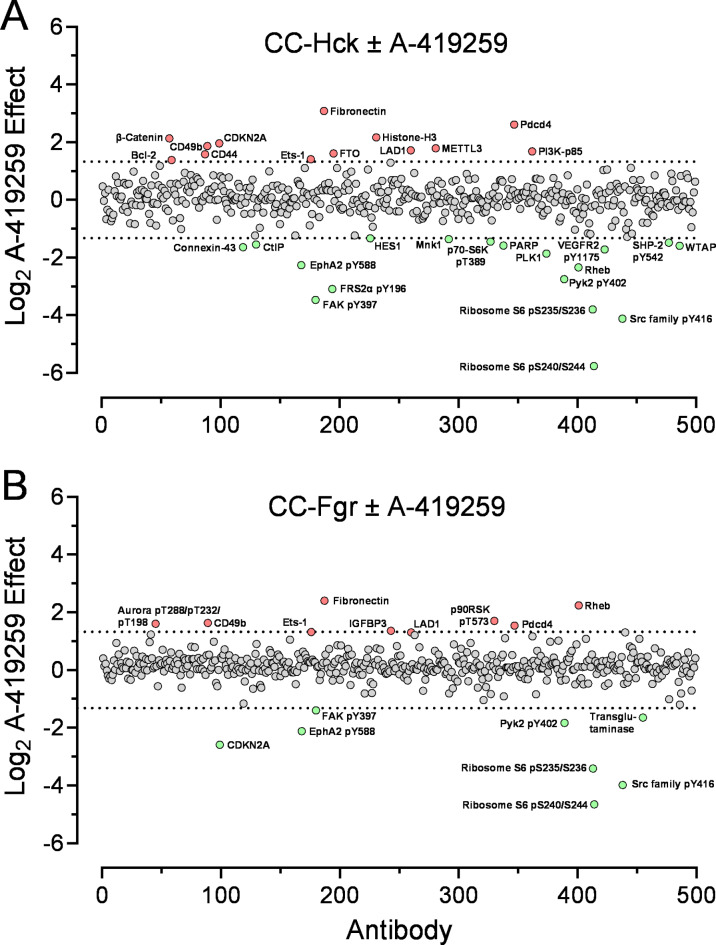

Figure 9 plots the overall RPPA data as the Log2 fold change observed in the presence of A-419259 vs. the untreated controls. Decreases in protein phosphorylation and protein expression levels greater than 2.5-fold observed with A-419259 treatment are summarized in Table 2. In both cell populations, A-419259 treatment inhibited Src-family kinase autophosphorylation (pTyr416 antibody) by more than 15-fold, providing direct evidence for inhibition of Fgr and Hck kinase activity. Overall, A-419259 treatment influenced ten phosphorylation events in the CC-Hck cell population vs. six for the CC-Fgr cells by 2.5-fold or more. Inhibitor treatment decreased expression of eight proteins in CC-Hck cells vs. two for CC-Fgr cells, with limited overlap between the two cell populations. Increases in protein expression levels were also observed following inhibitor treatment (Table 3). Four proteins were increased more than 2.5-fold in both cell populations, with ten unique to CC-Hck cells vs. two for CC-Fgr cells. Increased phosphorylation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase and Aurora kinases was also observed in CC-Fgr cells. Overall, of the 37 changes in protein phosphorylation and expression observed, 32 have been previously implicated in AML cell survival, disease progression, and/or drug resistance (see Tables 2 and 3).

Fig. 9.

Reverse phase protein array analysis of Hck and Fgr signaling in TF-1 cells. TF-1 cells expressing (A) CC-Hck or (B) CC-Fgr were treated with A-419259 (300 nM) for 16 h or left untreated. Cell lysates were prepared, spotted on replicate glass slides, and individual slides were probed with antibodies that recognize 499 distinct signaling proteins and phosphoproteins. Differences in immunoreactivity were quantified and plotted as Log2 of the ratio of the treated vs. untreated samples. Each dot represents the result from one antibody, and the results are shown in alphabetical order of each antibody name. The dotted lines correspond to changes greater than 2.5-fold, with points corresponding to decreases shown in green and increases shown in red.

Table 2.

Protein phosphorylation and expression levels reduced by A-419259 in TF-1 cells expressing active Fgr or Hck.

| Protein affected | Hck cells, fold decrease | Fgr cells, fold decrease | Function | AML connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreases in protein phosphorylation | ||||

| Ribosomal protein S6 (pS240/pS244) | 54.03 | 25.10 | Indicative of increased mTORC1 activity and protein synthesis | mTORC1-S6K pathway linked to AML initiation and progression33 |

|

Src family kinases (pY416) |

17.44 | 15.76 | Increased Src-family kinase activity | Positive control for A-419259 inhibition of Hck and Fgr |

|

Ribosomal protein S6 (pS235/pS236) |

13.93 | 10.62 | Indicative of increased mTORC1 activity and protein synthesis | mTORC1-S6K pathway linked to AML initiation and progression33 |

| Focal adhesion kinase Fak (pY397) | 11.11 | 2.63 | Regulates adhesion and migration | Regulates LSC survival and stromal interactions34 |

|

FRS2α (pY196) |

8.49 | 1.28 | Adaptor protein linked to proliferative signaling | Linked to Src activation in stem cell leukemia-lymphoma syndrome35 |

|

Pyk2 (pY402) |

6.71 | 3.55 | FAK homolog regulates adhesion and migration | Potential redundancy with Fak in cancer development36 |

|

EphA2 (pY588) |

4.81 | 4.35 | Ephrin family receptor tyrosine kinase | Experimental therapy target in MLL-AF9 leukemic mice37 |

|

SHP-2 (pY542) |

3.62 | 1.46 | Protein-tyrosine phosphatase and adaptor protein | Promotes AML cell growth and survival38 |

|

VEGFR2 (pY1175) |

2.92 | 2.01 | Receptor tyrosine kinase associated with neoangiogenesis | Inhibitors suppress AML cell growth in vitro and in vivo39 |

|

p70-S6K (pT389) |

2.80 | 1.78 | Activating linker tyrosine on ribosomal protein S6 kinase40 | mTORC1-S6K pathway linked to AML initiation and progression33 |

| Decreases in protein levels | ||||

| Rheb | 5.06 | (↑ 4.72) | Small GTPase linked to mTORC1 activation | Promotes AML progression via mTORC1 in MLL-AF9 mice41 |

| PLK1 | 3.62 | 1.28 |

Polo-like Kinase 1 Cell cycle regulator |

Overexpressed in AML and potential drug target42 |

| Connexin-43 | 3.30 | 2.23 | Intercellular communication, migration, polarity | |

| WTAP | 3.11 | 2.29 | Wilm’s tumor-1 associated protein pre-mRNA splicing factor | Overexpressed and predicts poor prognosis in AML43 |

| PARP | 3.02 | 1.89 |

Poly ADP-ribose polymerase DNA repair and genome integrity |

Potential therapeutic target in some AML subtypes44 |

| CtIP (RBBP8) | 3.00 | (↑ 1.86) | Regulates DNA repair via homologous recombination | |

| Mnk1 | 2.74 | 1.75 | MAPK-interacting kinase 1 regulates protein synthesis via eIF4E | Inhibitors induce G1 arrest and apoptosis in AML cells45,46 |

| HES1 | 2.56 | 1.33 | Transcriptional repressor regulated by NOTCH, Hedgehog and Wnt | Promotes cancer stem cell phenotype47 |

| CDKN2A | (↑ 3.89) | 5.88 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p16-Ink4a and p14-Arf | Tumor suppressor lost in many cancers48 |

| Transglutaminase (TGM2) | 1.73 | 3.14 | Protein crosslinking in apoptosis, wound healing, and cell adhesion | Promotes metastasis, drug resistance and stemness49 |

Changes are grouped as effects on protein phosphorylation and protein level in order of largest to smallest for TF-1 CC-Hck cells. Two protein level decreases are unique to Fgr cells (CDKN2A and transglutaminase). Values shown in parentheses represent increases.

Table 3.

Protein expression levels increased by A-419259 in TF-1 cells expressing active Fgr or Hck.

| Protein affected | Hck cells, fold increase | Fgr cells, fold increase |

Function | AML connection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increases in protein expression, Fgr and Hck | ||||

| Fibronectin | 8.43 | 5.29 | Cell adhesion | Promotes AML cell adhesion in bone marrow microenvironment50 |

| Pdcd4 | 6.12 | 2.90 |

Programmed cell death 4 Regulates protein translation51 |

Signifies decreased mTORC1 activity in AML cells52 |

| CD49b | 3.66 | 3.09 |

Integrin α2 subunit Cell adhesion and signaling |

Promotes chemoresistance in AML cell lines53 |

| Ets-1 | 2.66 | 2.50 | Transcription factor | |

| Increases in protein expression, Hck specific | ||||

| Histone H3 | 4.51 | 1.68 | Chromatin structure | Target of methylation in AML54 |

| β-Catenin | 4.38 | 1.24 | Cell adhesion and signaling | Promotes AML cell survival and chemoresistance55 |

| CDKN2A | 3.89 | (↓ 5.88) | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p16-Ink4a and p14-Arf | Tumor suppressor lost in many cancers48 |

| METTL3 | 3.45 | 1.02 | N6-adenosine-methyltransferase | Promotes survival and suppresses differentiation of AML cell lines56 |

| LAD1 | 3.29 | 2.47 |

Anchoring filament protein Cell adhesion |

|

| PI3K p85 | 3.21 | 2.25 |

Phosphoinositide signaling Akt activation |

Promotes AML cell growth, proliferation, and survival57 |

| FTO | 3.05 | 1.16 | RNA and DNA demethylation | |

| CD44 | 3.00 | (↓ 1.12) | Cell adhesion and migration | Extrinsic control of leukemia stem cell homing and survival58 |

| Bcl-2 | 2.61 | 1.03 | Mitochondrial apoptotic suppressor | Target for Venetoclax in CLL and AML59 |

| Increases in protein expression, Fgr specific | ||||

| Rheb | (↓ 5.06) | 4.72 | Small GTPase linked to mTORC1 activation | Promotes AML progression via mTORC1 in MLL-AF9 mice41 |

| p90 RSK (pT573) | (↓ 1.11) | 3.24 |

p90 Ribosomal S6 protein kinase |

Essential for FLT3-ITD+ AML cell growth and survival60 |

|

Aurora-ABC (pT288/T232/T198) |

1.80 | 3.03 | Mitotic kinase | Emerging inhibitor target in AML61 |

| IGFBP3 | 2.44 | 2.57 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein | |

Values shown in parentheses represent decreases.

Multiple changes induced by A-419259 are linked to the mammalian target of rapamycin complex-1/p70 S6 ribosomal protein kinase (mTORC1-S6K) pathway. The largest decrease in protein phosphorylation was observed for the ribosomal S6 protein itself, with a more than 50-fold decrease in Ser240/Ser244 S6 protein phosphorylation in CC-Hck cells and a 25-fold decrease in CC-Fgr cells (Table 2). Phosphorylation of S6 protein sites Ser235/Ser236 decreased more than tenfold in each inhibitor treated cell population as well. Consistent with this observation, decreased phosphorylation of p70 S6 ribosomal protein kinase on Thr389 was also observed; this site is involved in kinase activation40. A-419259-sensitive p70 S6 kinase and ribosomal S6 protein phosphorylation were independently confirmed in cells expressing active Hck and Fgr by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 10A). Expression of the small GTPase Rheb, which activates mTORC133, was decreased more than fivefold in CC-Hck cells in response to inhibitor treatment. In addition, expression of the protein translation regulator Pcdc4 was increased in both cell populations following A-419259 treatment. Phosphorylation of Pcdc4 downstream of mTORC1-S6K leads to its degradation, so increased expression is consistent with reduced mTORC1 activity52. Taken together, these results suggest that both Hck and Fgr increase flux through the mTORC1-S6K pathway, which plays a key role in normal hematopoiesis as well as self-renewal of leukemic stem cells in AML33.

Fig. 10.

Active forms of Hck and Fgr hijack p70 S6 kinase and Fak signaling in AML cells. (A) TF-1 cells expressing active coiled-coil fusions of Hck and Fgr were treated in the presence or absence of A-419259 (300 nM) overnight. Lysates were prepared from these cultures as well as the TF-1 parent and cells expressing wild-type Hck or Fgr. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for immunoblot analysis. Blots were probed for p70 S6 kinase (p70S6K) phosphorylation (pThr389), p70 S6K expression (S6 kinase), ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation (pSer235/236), Fak phosphorylation (pTyr397) and Fak expression along with Actin. All immunoreactive bands were detected with secondary antibodies tagged with infrared dyes and imaged using the LI-COR Odyssey platform. The positions of the molecular weight markers (in kDa) are shown to the left of each panel. (B) Parental TF-1 cells and cells expressing wild-type Hck or Fgr (cultured in GM-CSF) were treated in the presence or absence of A-419259 (300 nM) overnight, and lysates were blotted with antibodies for p70 S6 kinase phosphorylation, expression, and ribosomal S6 protein phosphorylation as described for part A. Uncropped blot images are provided in the Supplemental Information, Figures S5 and S6 (p70S6 kinase) and S7 (Fak).

TF-1 cells transformed to cytokine independence by CC-Hck or CC-Fgr demonstrated A-419259-sensitive activation of the p70 S6 kinase pathway downstream (Fig. 10A). However, basal activation of p70 S6 kinase was also observed in parental TF-1 cells as well as cells expressing wild-type Hck and Fgr, all of which require GM-CSF for proliferation and survival. To test whether p70 S6 kinase activation in these cells is also linked to Src-family kinase activation, we treated these cells in the presence or absence of A-419259 followed by immunoblot analysis for p70 S6 kinase phosphorylation on Thr389 as well as phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 protein (pSer235/236) itself. A-419259 treatment had no effect on basal phosphorylation in the S6 kinase pathway in these cells (Fig. 10B), indicating that active forms of Hck and Fgr hijack S6 kinase signaling by a distinct mechanism.

What is the mechanism by which AML-associated Src-family kinases stimulate signaling through the mTORC1 pathway? A-419259 treatment did not affect Akt1 or Akt2 expression or phosphorylation of activating sites in the RPPA analysis, which are among the best characterized activators upstream of mTORC1 in AML and other cancers33. An alternative pathway is suggested by the recent observation that tyrosine phosphorylation of Deptor, an endogenous inhibitor of mTORC1, suppresses its interaction with the mTOR kinase and leads to increased mTOR activity62. This previous study showed that inhibitors of Src-family kinase activity (PP2 and dasatinib) suppressed Deptor tyrosine phosphorylation in HeLa cells. Thus, Deptor represents a possible target for Fgr and Hck phosphorylation and a connection to upregulation of mTORC1 signaling.

Eph receptor tyrosine kinases have also been identified as upstream regulators of Deptor via tyrosine phosphorylation62. We observed that phosphorylation of EphA2 on Tyr588 was significantly reduced by A-419259 treatment of both the CC-Hck and CC-Fgr cell populations. Other work has implicated EphA2 as a mediator of Src signaling63 and EphA2 itself has been suggested as a therapeutic target in a mouse model of AML37. Importantly, previous kinome-wide profiling of A-419259 selectivity9 argues against direct inhibition of mTOR kinase, S6 kinase, or EphA2, consistent with a mechanism of action initiated by active Hck and Fgr.

In addition to the mTORC1-S6K pathway, A-419259 treatment also inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (Fak) as well as the homologous kinase, Pyk2. In each case, the affected phosphorylation site (pTyr397) creates a docking site for Src-family kinases through their SH2 domains, leading to enhanced signaling by both kinases36. Fak has been linked to leukemia stem cell survival as well as interactions with bone marrow stromal cells, and has been explored as a therapeutic target in AML as well as myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)34. Subsequent immunoblots produced similar results, with strong, A-419259-sensitive signals for Fak pTyr397 observed in lysates from CC-Hck cells and in CC-Fgr cells albeit to a much lesser extent (Fig. 10A). The presence of active CC-Hck correlated with proteolytic cleavage of Fak, resulting in a smaller ~ 70 kDa pFak species on the pTyr397 immunoblot. Proteolytic activation of Fak has been reported in other forms of cancer, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia where it contributes to an aggressive phenotype64. Replicate blots with an antibody for the Fak protein showed the expected full-length 120 kDa form in all samples, with reduced band intensity in the CC-Hck sample consistent with proteolytic cleavage. The smaller form is not observed on the Fak protein blot, indicating that the FAT domain has been cleaved; this region of Fak carries the epitope for the antibody. A previous RPPA study reported that high levels of Fak expression correlated with unfavorable cytogenetic profiles and relapse in both AML and MDS patient samples34. Consistent with our observations, Fak expression correlated significantly with pSrc (pY416) levels although the individual Src-family members involved were not identified. Previous selectivity profiling demonstrates that A-419259 is unlikely to influence Fak or Pyk2 kinase activity directly9, supporting Fgr and Hck as the direct inhibitor targets in this pathway. In addition to Fak/Pyk2 signaling, A-419259 treatment increased expression of several additional proteins linked to cell adhesion. Inhibitor treatment of both cell populations enhanced expression of Fibronectin and CD49b (integrin α2 subunit), with the CC-Hck cells showing upregulation LAD1, CD44, and β-catenin as well (Table 3).

While most of the signaling events affected by Hck were also linked to Fgr, albeit to a lesser extent in most cases, expression of a few proteins involved in growth regulation were affected in opposite ways (Table 2). A-419259 treatment led to a marked decrease in the expression of Rheb in CC-Hck cells, supporting up-regulation of this mTORC1 activator by Hck. In CC-Fgr cells, however, inhibitor treatment resulted in an increase in Rheb expression of similar magnitude. Because Hck and Fgr expression is tightly correlated in patient AML samples9, the opposing effects of each kinase may result in little net change in Rheb expression overall. Another example relates to expression of the CDKN2A locus, which encodes the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p16 Ink4a and p14 Arf. These endogenous cell cycle regulators act as tumor suppressors and are lost in many forms of cancer48. In this case, A-419259 treatment decreased CDKN2A expression in CC-Fgr cells while increasing expression in CC-Hck cells, again suggesting a minimal net effect in AML cells where both kinases are expressed.

Summary and limitations of the study

The Src-family kinases Hck and Fgr are often over-expressed and constitutively active in AML cells. While genetic knockdown and pharmacological inhibition of these kinases suppresses AML cell growth and induces apoptosis, the individual contributions of these kinases to AML progression and the signaling pathways they influence are less clear. Using the human cytokine-dependent cell line TF-1 as a model system, we found that activation of either Hck or Fgr by two independent mechanisms (coiled-coil domain fusion or gatekeeper mutation) was sufficient to transform the cells to cytokine-independent growth and survival in vitro. Active forms of either kinase also enhanced cell growth in vivo, with overexpression of wild-type Hck without a kinase-activating mutation sufficient to drive bone marrow engraftment and decrease survival. Phosphoproteomic analyses revealed that active Hck and Fgr are linked to enhanced ribosomal S6 kinase and Fak signaling, both of which have been previously implicated in AML cell growth and survival33,34. While significant overlap in Fgr and Hck signaling pathways was observed in this model system, the effects with Hck were generally of greater magnitude especially with Fak. Combinations of inhibitors for either of these pathways with Src-family kinase inhibitors may improve efficacy and reduce the potential for acquired resistance in AML cases where these kinases are over-expressed.

The mechanism by which coiled-coil fusion drives Hck and Fgr activation requires further comment. Immunoblots shown in Fig. 4 support enhanced autophosphorylation of each kinase at activation loop tyrosine 416. While statistical significance was not reached due to variation between the blots, a clear upward trend is observed with the active forms. In addition, quantitative RPPA analysis (Fig. 9; Tables 2 and 3) revealed that the coiled-coil active forms of Hck and Fgr both show enhanced, A-419259-sensitive autophosphorylation (pY416) and downstream signaling capacity in TF-1 cells. Overall, the effect of coiled-coil fusion may result not only from increased autophosphorylation due to oligomerization, but also from the ‘opening’ of the kinases which results in exposure of the signaling domains (Fig. 5).

One limitation of the mouse model relates to the absence of human cytokine expression in the NSG mouse strain. The parent TF-1 cell line, as well as cells expressing wild-type Hck and Fgr, require GM-CSF to proliferate in vitro. This may put these cell populations at a disadvantage in vivo as well, because of the lack of human GM-CSF in the bone marrow and other sites. Cells transformed to cytokine independence by active forms of Hck and Fgr are not constrained by this lack of GM-CSF in vitro or in vivo. Future studies will examine the behavior of these cell populations in additional immunocompromised mouse strains that are also engineered to express human hematopoietic cytokines.

Mutations resulting in the activation of Hck, Fgr or other Src-family kinases are not frequently found in AML patients. However, Hck and Fgr are often over-expressed which correlates significantly with poor patient outcomes9. In addition, primary AML cells show coordinated upregulation of multiple myeloid Src-family members (Hck, Fgr and Lyn), which may amplify signals for growth and survival even further9. One unexpected finding in our study is that over-expression of wild-type Hck enhanced bone marrow engraftment in vivo (Fig. 8), suggesting that over-expression of Hck alone may be an important contributor to AML etiology. This observation is consistent with prior work showing that Hck is over-expressed in primary leukemic stem cells13, making it an attractive target for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and methods

Cell Culture

MV4-11, TF-1, and 293T cells were sourced from the American Type Culture Collection. MV4-11 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium, supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, and Antibiotic–Antimycotic (Life Technologies, #15240062). Parental TF-1 cells were cultured in the same medium supplemented with 100 ng/mL human GM-CSF (Life Technologies #PHC2015). Human 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS.

Expression vector construction and retroviral transduction

Coding sequences for human Fgr, Hck (p59 form) and Flt3-ITD were subcloned into the retroviral vector, pMSCVpuro (Takara) as described elsewhere16. To create CC-Hck and CC-Fgr, the coding sequence for the 70 amino acid coiled-coil domain of Bcr was amplified by PCR and subcloned in frame to the 5’ end of each kinase cDNA. The T338M gatekeeper mutants were generated using the QuikChange II site-directed mutagenesis system (Agilent). The complete nucleotide sequences of all Fgr and Hck coding regions were confirmed prior to use. Recombinant retroviruses were produced from the pMSCVpuro vectors in 293T cells and used to transduce TF-1 cells using our published protocol9,16. Cells were initially selected in the presence of 3 µg/mL puromycin and 2 ng/mL GM-CSF for 1–2 weeks. Once the puromycin-resistant population emerged, cells expressing active forms of Fgr, Hck as well as Flt3-ITD were transitioned to GM-CSF-free medium in plus 1 µg/mL puromycin. Recombinant lentiviruses containing the iRFP720-E2A-Luciferase sequence, where a viral E2A sequence promotes ribosomal skipping, were produced in 293T cells transfected with pHIV-iRFP720-E2A-Luc (Addgene #104587)65 and the packaging plasmids psPAX2 (Addgene #12260) and pMD2.G (Addgene #12259) with 3:2:1 ratio of plasmid DNA using the using X-tremeGENE 9 DNA transfection reagent (Millipore Sigma). All TF-1 cell populations were transduced with the iRFP720/Luc lentiviruses using our published protocol16, and iRFP720-positive cells were sorted using a BD FACSAria II flow sorter. Expression was maintained by regular sorting to maintain > 95% positivity of iRFP720 prior to injection into mice.

RNA Isolation, cDNA preparation, and real‐time quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from MV4-11 and TF-1 cells using the QIAamp RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was prepared from 4 µg of RNA using the SuperScript IV first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction (ThermoFisher). Reverse transcription reactions (80 μL) were diluted tenfold with reaction mix and 8 µL was used for qPCR with gene‐specific QuantiTect primers and SYBR Green detection (Qiagen). The Ct value for each kinase was corrected for the corresponding GAPDH Ct value (ΔCt) and then converted to a relative expression value by calculating the base 2 antilog. To establish the overall kinase expression profile, the relative expression value for each individual kinase was normalized to the average expression value for all kinases examined within each sample as per Weir et al.16.

TF-1 cell growth assay

TF-1 cell populations were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL in 6-well culture plates in the presence and absence of GM-CSF. Cell viability was assessed every 24 h over four days using the CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability assay (Promega #G8080) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a SpectraMax M5 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) with an excitation wavelength of 560 nM and emission wavelength of 590 nm.

Kinase inhibitor sensitivity assays

TL02-59 was custom synthesized by A Chemtek, Inc. and A-419259 was purchased from Cayman Chemical (#18168). TL02-59 was reconstituted to 10 mM in DMSO and diluted into cell cultures with a final DMSO concentration of 0.1%. A-419259 was reconstituted as a 10 mM stock in autoclaved Milli-Q water. TF-1 cells were seeded at 100,000 cells/mL in 96-well culture plates, and serial dilutions of each inhibitor were added to triplicate wells. Cell viability was assessed 72 h later using the CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability assay as described above. IC50 values were determined by non-linear regression analysis of concentration–response curves with the GraphPad PRISM software package (version 10).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Antibodies for immunoprecipitation: Fgr rabbit polyclonal Ab, Cell Signaling Technologies #2755S; Hck rabbit mAb, Cell Signaling Technologies #14643S. Antibodies for immunoblotting: Src pY416, Millipore Sigma #05-677; Hck mouse mAb, Santa Cruz #sc-101428; Fgr mouse mAb, Thermo Fisher #H00002268-M02; Actin mouse mAb, Millipore Sigma #MAB1501R. Antibodies for RPPA validation blots were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies: Fak protein, #3285T; pFak pY397, #8556T; p70 S6 kinase protein, #34475; p70 S6 kinase pThr389, #9234T; ribosomal protein S6 pSer235/236, #4858T.

TF-1 cells were washed with cold PBS and resuspended in Cell Lysis Buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 µg/mL leupeptin; Cell Signaling Technology, #9803) with cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Millipore Sigma #11836170001). Following sonication, lysates were clarified by microcentrifugation at 4 °C and the protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Dye Reagent. For immunoprecipitation, lysate protein (2 mg) was diluted to 0.5 mL in lysis buffer and combined with 1 µg Hck or 0.65 µg Fgr antibody plus 20 µL of protein G-Sepharose beads (ThermoFisher) and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitates were collected by microcentrifugation and washed three times by resuspension in 1.0 ml of lysis buffer. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the primary antibodies indicated above. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated to infrared dyes (LI-COR, #926-68022 and #926-32213) and scanned on a LI-COR Odyssey CLx imaging system.

SH3 domain peptide capture assay

The biotinylated VSL12 SH3 domain capture peptide (amino acid sequence VSLARRPLPPLP) was synthesized by the University of Pittsburgh Health Sciences Peptide Synthesis Core Laboratory and immobilized on streptavidin Dynabeads (SA-Dynabeads; ThermoFisher M-270; Cat# 65305) as follows. The SA-Dynabead suspension (200 µL) was washed with 1.0 mL PBS, resuspended in 1.0 mL PBS with 0.01% BSA (PBS/BSA), and 5 µL of biotin-VSL12 from a 10 mg/mL stock was added. The mixture was incubated for 30 min with gentle rocking followed by three washes with 1.0 mL PBS/BSA to remove unbound peptide. The VSL12-SA-Dynabeads were resuspended in 0.5 mL PBS/BSA and placed on ice. Control beads were prepared in the same manner except the VSL12 capture peptide was omitted. Clarified TF-1 cell lysates were prepared as described above for immunoprecipitation. Cell lysate protein (0.5–2.0 mg) was diluted to 1.0 mL in Cell Lysis buffer and combined with 20 µL of the VSL12-SA-Dynabead prep (or no peptide control beads), followed by incubation for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed 3 times with 1.0 mL PBS with 0.1% Tween-20, resuspended in 20 μL 2X SDS sample buffer, and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Bound kinase proteins were detected by immunoblotting as described above.

Mouse AML xenograft model

All experimental protocols involving mice were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (United States Public Health Service Assurance # D16-00118; approved protocol # 22112126). All experimental methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations as set forth in the approved protocol. Methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org).

NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) immunodeficient mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. For tumor burden studies, 6–12-week-old mice were injected with busulfan 25 mg/kg (Millipore Sigma) intraperitoneally once a day for two days, and the following day injected with various TF-1 cell populations (5 × 106 cells/mouse) suspended in PBS via the tail vein. In vivo imaging of tumor cell growth in the mice was performed under isoflurane anesthesia. Each mouse was injected with 165 mg/kg of luciferin (Revvity) intraperitoneally right after cell injection and weekly until the end of the 4th week. Photons were detected using a Lumina S5 (Revvity) in vivo imaging system (IVIS) and analyzed using Living Image software (Revvity; ver. 4.7.2) and GraphPad PRISM (ver. 10). At the end of the fourth week, all mice were sacrificed by exposure to carbon dioxide as per the approved protocol and blood, bone marrow and spleen were collected from the carcasses. Single cell suspensions were prepared from part of the tissue samples and human AML cells were detected by flow cytometry as described below. Tissue samples were also trimmed and fixed in formalin, and bones were decalcified in 10% formic acid for histology and immunohistochemistry. AML cells in tissue sections were identified by immunohistochemistry using a rabbit monoclonal anti-human CD45 (D9M8I) XP antibody (Cell Signaling Technologies #139175). For survival studies, 6–12-week-old mice were injected with cells and tumor burden was monitored by IVIS weekly until mice succumbed from the tumor burden, met euthanasia guidelines, or after 120 days. Euthanasia was performed by exposing the mice to carbon dioxide as per the approved protocol.

Flow cytometry

Bone marrow, spleen, and blood samples from engrafted mice were analyzed for TF-1 cells by flow cytometry with human CD45-FITC (BD Biosciences, Clone HI30,) and human CD33-APC (BD Biosciences, Clone WM53) antibody conjugates. Red blood cells in the bone marrow and spleen were lysed in 10 mM KHCO3, pH 7.4, 155 mM NH4Cl, and 130 µM EDTA prior to antibody staining as described16. Cells were then analyzed on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer and the resulting data were evaluated using BD CSampler Plus software and GraphPad PRISM.

Reverse phase protein array (RPPA)

TF-1 cells transformed with either CC-Fgr or CC-Hck were treated with A-419259 at a final concentration of 300 nM with parallel cultures left untreated for comparison. Following 16 h incubation, cell viability was determined to be > 90% by trypan blue exclusion. Cells were pelleted, washed with ice cold PBS, pelleted again, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for shipment to the MD Anderson Cancer Center for RPPA analysis.

Proteins were extracted from the frozen cell pellets and concentrations adjusted to 1.5 mg/mL. Proteins were denatured by addition of SDS and 2‐mercaptoethanol, followed by serial dilution and printing on nitrocellulose‐coated glass slides. Individual slides were probed with each of 499 validated antibodies to a wide range of signaling molecules including phosphospecific antibodies; a complete list of the antibodies can be found at the following link: https://www.mdanderson.org/research/research-resources/core-facilities/functional-proteomics-rppa-core.html.

Immunoreactive signals were captured by tyramide dye deposition and a DAB (3,3’-diaminobenzidine) colorimetric reaction. Quantitative analysis was performed using custom spot finding and curve fitting software. Values are expressed relative to standard control cell lysates or control peptides spotted on each array to allow comparison of the levels of protein expression or modification (e.g. phosphorylation) across all slides.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank N. Sheng of the Immunology Department flow cytometry core and J. Hart of the McGowan Institute for expert technical assistance.

Author contributions

S.T.S. and T.E.S. designed the study and S.T.S., L.C., and G.G.A. performed the experiments. All authors contributed to the data analysis. T.E.S. wrote the original draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant CA233576. The Revvity Lumina S5 in vivo imaging system is a shared resource supported by NIH grant S10 OD025011.

Data availability

All unique non-commercial materials used in this study will be made available to qualified researchers for the purposes of reproducing or extending the analysis under the auspices of the materials transfer agreements of the respective institutions. All data from this study are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Janke, H. et al. Activating FLT3 mutants show distinct gain-of-function phenotypes in vitro and a characteristic signaling pathway profile associated with prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS ONE9, e89560 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith, C. C. et al. Validation of ITD mutations in FLT3 as a therapeutic target in human acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature485, 260–263 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffith, J. et al. The structural basis for autoinhibition of FLT3 by the juxtamembrane domain. Mol. Cell13, 169–178 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudhindra, A. & Smith, C. C. FLT3 inhibitors in AML: are we there yet?. Curr. Hematol. Malig. Rep.9, 174–185 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith, C. C. et al. Characterizing and overriding the structural mechanism of the Quizartinib-resistant FLT3 “Gatekeeper” F691L mutation with PLX3397. Cancer Discov.5, 668–679 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weis, T. M., Marini, B. L., Bixby, D. L. & Perissinotti, A. J. Clinical considerations for the use of FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.141, 125–138 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dos, S. C. et al. A critical role for Lyn in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood111, 2269–2279 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dos Santos, C. et al. The Src and c-Kit kinase inhibitor dasatinib enhances p53-mediated targeting of human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells by chemotherapeutic agents. Blood122, 1900–1913 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel, R. K. et al. Expression of myeloid Src-family kinases is associated with poor prognosis in AML and influences Flt3-ITD kinase inhibitor acquired resistance. PLoS One14, e0225887 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musumeci, F. et al. Hck inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents in cancer and HIV infection. Curr. Med. Chem.22, 1540–1564 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guiet, R. et al. Hematopoietic cell kinase (Hck) isoforms and phagocyte duties - from signaling and actin reorganization to migration and phagocytosis. Eur. J. Cell Biol.87, 527–542 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowell, C. A., Soriano, P. & Varmus, H. E. Functional overlap in the src gene family: Inactivation of hck and fgr impairs natural immunity. Genes Dev.8, 387–398 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito, Y. et al. A pyrrolo-pyrimidine derivative targets human primary AML stem cells in vivo. Sci. Transl. Med.5, 181ra152 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koda, Y. et al. Identification of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines as potent HCK and FLT3-ITD dual inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett27, 4994–4998 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen, K. et al. The Src family kinase Fgr is a transforming oncoprotein that functions independently of SH3-SH2 domain regulation. Sci. Signal11 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Weir, M. C. et al. Selective inhibition of the myeloid Src-family kinase Fgr potently suppresses AML cell growth in vitro and in vivo. ACS Chem. Biol13, 1551–1559 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao, X., Ghaffari, S., Lodish, H., Malashkevich, V. N. & Kim, P. S. Structure of the Bcr-Abl oncoprotein oligomerization domain. Nat. Struct. Biol9, 117–120 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamura, T. et al. Establishment and characterization of a unique human cell line that proliferates dependently on GM-CSF, IL-3 or erythropoietin. J. Cell. Physiol140, 323–334 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Panjarian, S. et al. Enhanced SH3/linker interaction overcomes Abl kinase activation by gatekeeper and myristic acid binding pocket mutations and increases sensitivity to small molecule inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem.288, 6116–6129 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hantschel, O. & Superti-Furga, G. Regulation of the c-Abl and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol5, 33–44 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panjarian, S., Iacob, R. E., Chen, S., Engen, J. R. & Smithgall, T. E. Structure and dynamic regulation of Abl kinases. J. Biol. Chem.288, 5443–5450 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Engen, J. R. et al. Structure and dynamic regulation of Src-family kinases. Cell Mol. Life Sci.65, 3058–3073 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du, S. et al. ATP-site inhibitors induce unique conformations of the acute myeloid leukemia-associated Src-family kinase, Fgr. Structure30, 1508-1517 e1503 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, W., Doshi, A., Lei, M., Eck, M. J. & Harrison, S. C. Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol. Cell3, 629–638 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azam, M., Seeliger, M. A., Gray, N. S., Kuriyan, J. & Daley, G. Q. Activation of tyrosine kinases by mutation of the gatekeeper threonine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.15, 1109–1118 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schindler, T. et al. Crystal structure of Hck in complex with a Src family-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol. Cell3, 639–648 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lerner, E. C. & Smithgall, T. E. SH3-dependent stimulation of Src-family kinase autophosphorylation without tail release from the SH2 domain in vivo. Nat. Struct. Biol.9, 365–369 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moroco, J. A. et al. Differential sensitivity of Src-family kinases to activation by SH3 domain displacement. PLoS One9, e105629 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pene-Dumitrescu, T. et al. HIV-1 Nef interaction influences the ATP-binding site of the Src-family kinase, Hck. BMC. Chem. Biol.12, 1 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Selzer, A. M., Alvarado, J. J. & Smithgall, T. E. Cocrystallization of the Src-family kinase Hck with the ATP-site inhibitor A-419259 stabilizes an extended activation loop conformation. Biochemistry63, 2594–2601 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Avni, B. & Koren-Michowitz, M. Myeloid sarcoma: current approach and therapeutic options. Ther. Adv. Hematol.2, 309–316 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawthorne, J. et al. Bilateral adnexal masses: A case report of acute myeloid leukemia presenting with myeloid sarcoma of the ovary and review of literature. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep.47, 101202 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh, J. & Kapur, R. Role of mTORC1-S6K1 signaling pathway in regulation of hematopoietic stem cell and acute myeloid leukemia. Exp. Hematol.50, 13–21 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter, B. Z. et al. Focal adhesion kinase as a potential target in AML and MDS. Mol. Cancer Ther.16, 1133–1144 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren, M., Qin, H., Ren, R., Tidwell, J. & Cowell, J. K. Src activation plays an important key role in lymphomagenesis induced by FGFR1 fusion kinases. Cancer Res.71, 7312–7322 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naser, R., Aldehaiman, A., Diaz-Galicia, E. & Arold, S.T. Endogenous control mechanisms of FAK and PYK2 and their relevance to cancer development. Cancers (Basel)10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Charmsaz, S. et al. EphA2 is a therapy target in EphA2-positive leukemias but is not essential for normal hematopoiesis or leukemia. PLoS One10, e0130692 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hao, F., Wang, C., Sholy, C., Cao, M. & Kang, X. Strategy for leukemia treatment targeting SHP-1,2 and SHIP. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.9, 730400 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]