Abstract

Metal implants are commonly used in clinical practice. However, little is known regarding the prevalence of metal implants. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of metal implants in the United States (US) among individuals aged ≥ 40 years. This study conducted a serial cross-sectional analysis of US adults aged ≥ 40 years who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2015–2016 and 2017–March 2020). Self-reported questionnaires were used to assess whether the participants had metal implants inside their bodies. The primary outcome was the prevalence of metal implants among adults aged 40 years and older. Furthermore, weighted logistic regression analysis was employed to determine the changes in the prevalence of metal implants from 2015 to March 2020. Moreover, this study investigated the variation in metal implant prevalence by demographic factors based on the pooled NHANES cycles. All analyses were conducted based on 3,736 participants from the NHANES 2015–2016 and 6,387 participants from the NHANES 2017–March 2020. This study observed a high prevalence of metal implants among adults aged 40 and older (2015–2016: 27.23%; 2017–March 2020: 31.53%). Moreover, the results of the weighted logistic regression analysis showed that the prevalence of metal implants significantly increased from 2015 to March 2020, especially among older individuals, men, and White individuals. In addition, the results of the weighted logistic regression analysis indicated that the metal implant prevalence differed by age and race/ethnicity, in which older individuals and White individuals showed a significantly higher prevalence of metal implants than younger individuals and non-White individuals, respectively. There was a high prevalence of metal implants among US adults aged 40 and older, and the prevalence of metal implants significantly increased from 2015 to March 2020. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to this special population, and it may be necessary to ensure accessibility and affordability and assess the potential long-term health impacts of metal implants, considering the increased prevalence of metal implants.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-84340-0.

Keywords: Metal implants, Orthopaedics, Epidemiology, Public health

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Epidemiology

Introduction

Metal implants, medical devices made from biocompatible metals, are commonly used in clinical settings, with about 70% of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved medical implants that are metal‐based1. Metal implants, typically made from materials such as titanium, stainless steel, cobalt-chromium alloys, or a combination of these metals, are commonly used to replace damaged or diseased bones or joints, providing stability, support, and restoring functionality to the affected area2,3. Furthermore, metal implants have been widely used in the field of orthopaedics, such as joint replacements, fracture fixation, spinal fusion, and bone reconstruction4–7. Take joint replacements as an example. Metal implants, which are considered the ideal material for replacing diseased bone and joint tissues, are used extensively in joint replacement surgery, such as total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty (TKA)8–11. One study reports that the annual procedure volumes of primary THA and primary TKA in the United States (US) in 2014 were about 370,770 and 680,150, respectively12. In addition, a large number of studies suggest that the use of THA and TKA is expected to increase significantly over time12–18. Although the above evidence is unable to reflect the epidemiology of metal implants directly and only reveals the tip of an iceberg, it is not hard to see that there is a large population of individuals with metal implants, especially with the increase in the aging population.

Although it is well recognized that metal implants play important roles in improving clinical outcomes, cumulative evidence indicates that metal implants may cause potential short- and long-term negative impacts on human health, such as infection, implant loosening, metal hypersensitivity, elevated concentrations of metal ions, wear and tear over time, and the possibility of requiring revision surgeries19–25. Furthermore, considering the efficacy and safety of the existing metal implants, the design and development of novel, more efficient, and safer metal implants has recently become an important research field and hot spot1,26–28. The above evidence suggests that the issues associated with metal implants have been widely discussed and received growing attention. Therefore, it is necessary to pay more attention to this special population, individuals with metal implants inside the body, and evaluate the prevalence of metal implants, which might play an essential role in supporting evidence-based decision-making, facilitating related research advancements, enhancing implant safety, and developing effective integrated management strategies in the future. However, to the best of our knowledge, none has concentrated on the prevalence of subjects with metal implants.

Against this background, this study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of metal implants among adults aged 40 and older in the United States (US) using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Moreover, this study evaluated the changing trends in the prevalence of metal implants from 2015 to March 2020. In addition, this study investigated whether the prevalence of metal implants varied by age, sex, and race/ethnicity. These exploratory attempts mentioned above might aid the understanding of the current status of the use of metal implants, which could help guide clinical strategies and public health policies.

Material and methods

Study design and populations

This serial cross-sectional study included participants aged 40 years and older (questions on metal implants were asked of only survey participants 40 years and older) from the NHANES (2015–2016 and 2017-March 2020), considering the questionnaire on metal implants was not evaluated before NHANES 2015–2016. Furthermore, this study excluded subjects without definitive answers to the question on metal implants (refused to answer or answered “don’t know.”) or with missing data on metal implants. The NHANES, which was conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), was designed to evaluate the health and nutritional status of US residents. Moreover, all participants from the NHANES have received and signed the informed consent, and the ethics review board of the NCHS has approved the NHANES29–31. Additional information was provided at the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). This study has been reported in line with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline32.

Questions on metal implants

A self-reported questionnaire, in which participants were asked the question “any metal objects inside your body,” was used to evaluate whether subjects were with metal implants. The definition of metal implants in the question contained any artificial joints, pins, plates, metal suture material, or other types of metal objects in the body, and the metal object should not be visible on the outside of the body or in the mouth (such as piercings, crowns, dental braces or retainers, shrapnel, or bullets). Other details about the questionnaire on metal implants are provided on NHANES33–35.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed from December 1, 2023, to January 5, 2024. This study first described the demographic characteristics and medical history (age, sex, race/ethnicity and diseases that led to the placement of the implants, such as arthritis and coronary heart disease) of participants included in the final analysis, in which continuous variables were reported as means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs, using Wald type confidence interval), while categorical variables were reported as percentages with 95% CIs. For demographic characteristics and medical history, missing data (participants who (i) refused to answer the question, (ii) answered “don’t know.” to the question, or (iii) with missing data) were reported as unknown. Furthermore, differences in demographic characteristics between NHANES 2015–2016 and NHANES 2017-March 2020 for continuous variables were assessed using survey-weighted linear regression, whereas categorical variables were compared using survey-weighted Chi-square test. Moreover, this study estimated the overall prevalence of metal implants and prevalence stratified by demographic factors in survey cycles 2015–2016 and 2017-March 2020. In addition, weighted logistic regression models were employed to assess the change in the prevalence of metal implants from survey cycles 2015–2016 to 2017-March 2020. In addition, the associations between demographic factors and the prevalence of metal implants were investigated based on the pooled NHANES cycles (2015–2016 and 2017-March 2020) using the weighted logistic regression models. In sensitivity analysis, this study assessed the prevalence of metal implants after excluding participants with missing data on demographic characteristics and medical history. Nationally representative estimates were calculated for all analyses by utilizing NHANES survey weights, which effectively accommodate the intricate, cluster-stratified design of NHANES36. Statistics were generated using R software version 4.2.1 (https://cran.r-project.org/) and EmpowerStats version 2.0 (http://www.empowerstats.com). A result was considered significant when its 2-sided P value was less than 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

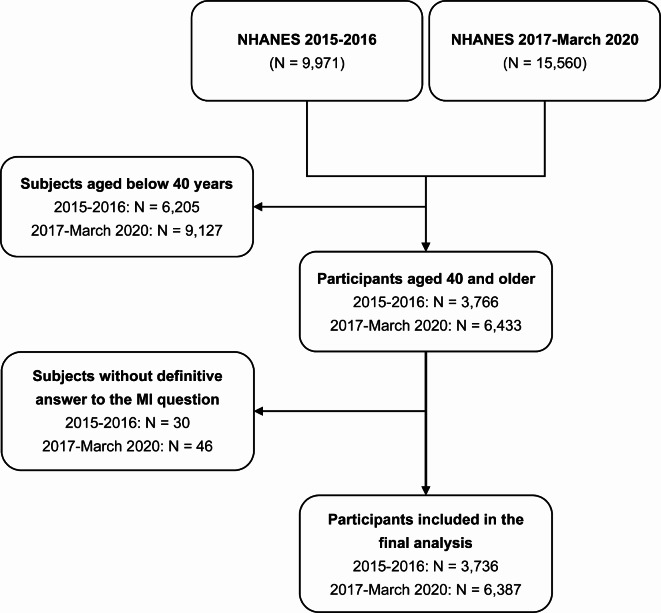

The flowchart of participant selection is shown in Fig. 1. For subjects aged 40 years and older, 74 participants (NHANES 2015–2016: N = 28; NHANES 2017-March 2020: N = 46) who answered “don’t know” to the questions on metal implants and two participants with missing data on metal implants (all from the NHANES 2015–2016) were excluded from the present study. Finally, a total of 10,123 participants from the NHANES (2015–2016: N = 3,736; 2017-March 2020: N = 6,387) were included in the final analysis. Moreover, the mean ages of participants from the NHANES 2015–2016 and NHANES 2017-March 2020 were 58.47 (95% CI: 57.56 to 59.37) and 59.05 (95% CI: 58.34 to 59.77), respectively. No significant differences in demographic characteristics except for the history of stroke (2015–2016: 4.02% vs. 2017-March 2020: 5.58%) between participants from NHANES 2015–2016 and NHANES 2017-March 2020 were observed. Other details on demographic information are listed in Table 1. In addition, there were no differences in age, sex, and race/ethnicity between included and excluded participants aged 40 and older (other details on demographic information are shown in Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of participant selection. MI, metal implant; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys.

Table 1.

Demographic factors of participants included in the final analysis.

| Demographic factor | NHANES 2015–2016 | NHANES 2017–March 2020 | P value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 3,736)a | (N = 6,387)a | ||

| Age (years), meanc | 58.47 (57.56, 59.37) | 59.05 (58.34, 59.77) | 0.326 |

| Sex, %c | 0.934 | ||

| Men | 47.20 (45.52, 48.90) | 47.30 (45.69, 48.91) | |

| Women | 52.80 (51.10, 54.48) | 52.70 (51.09, 54.31) | |

| Race/ethnicity, %c | 0.873 | ||

| White | 68.68 (60.27, 76.02) | 66.76 (61.71, 71.45) | |

| Black | 10.56 (6.97, 15.70) | 10.66 (8.11, 13.88) | |

| Mexican American | 6.92 (3.98, 11.77) | 6.48 (4.92, 8.49) | |

| Other | 13.84 (10.22, 18.48) | 16.10 (13.51, 19.08) | |

| History of arthritis, % | 0.768 | ||

| Yes | 38.20 (35.84, 40.56) | 39.18 (36.30, 42.05) | |

| No | 61.58 (59.24, 63.93) | 60.61 (57.73, 63.48) | |

| Unknownd | 0.22 (0.03, 0.41) | 0.22 (0.14, 0.30) | |

| History of congestive heart failure, % | 0.969 | ||

| Yes | 3.77 (3.15, 4.39) | 3.87 (3.06, 4.67) | |

| No | 95.95 (95.27, 96.64) | 95.88 (95.06, 96.71) | |

| Unknownd | 0.28 (− 0.02, 0.57) | 0.25 (0.10, 0.40) | |

| History of coronary heart disease, % | 0.267 | ||

| Yes | 5.34 (4.34, 6.35) | 6.31 (4.69, 7.93) | |

| No | 94.24 (93.18, 95.30) | 93.47 (91.83, 95.11) | |

| Unknownd | 0.42 (0.13, 0.70) | 0.22 (0.11, 0.33) | |

| History of angina/angina pectoris, % | 0.468 | ||

| Yes | 2.99 (2.35, 3.63) | 3.28 (2.62, 3.94) | |

| No | 96.81 (96.15, 97.48) | 96.41 (95.71, 97.11) | |

| Unknownd | 0.20 (0.06, 0.33) | 0.31 (0.22, 0.41) | |

| History of heart attack, % | 0.586 | ||

| Yes | 5.07 (4.21, 5.93) | 5.56 (4.37, 6.76) | |

| No | 94.84 (93.99, 95.68) | 94.28 (93.08, 95.49) | |

| Unknownd | 0.09 (0.00, 0.18) | 0.15 (0.02, 0.29) | |

| History of stroke, % | 0.018 | ||

| Yes | 4.02 (3.47, 4.57) | 5.58 (4.82, 6.34) | |

| No | 95.88 (95.26, 96.50) | 94.30 (93.52, 95.07) | |

| Unknownd | 0.10 (− 0.04, 0.25) | 0.13(0.05, 0.20) | |

| History of cancer, % | 0.221 | ||

| Yes | 16.20 (15.12, 17.28) | 16.60 (15.20, 17.99) | |

| No | 83.69 (82.56, 84.83) | 83.38 (82.00, 84.77) | |

| Unknownd | 0.11 (− 0.07, 0.29) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) |

aUnweighted sample size.

bP value determined by survey-weighted linear regression (for continuous variables) or survey-weighted Chi-square test (for categorical variables).

cWeighted mean or percentage.

dParticipants who (i) refused to answer the question, (ii) answered “don’t know.” to the question, or (iii) with missing data.

NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Table 2.

Demographic factors between included and excluded participants.

| Demographic factor | Included | Excludeda | P valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 10,123)b | (N = 76)b | ||

| Age (years), mean | 58.83 (58.27, 59.39) | 62.36 (58.01, 66.71) | 0.117 |

| Sex, % | 0.518 | ||

| Men | 47.26 (46.11, 48.42) | 41.15 (23.5, 61.42) | |

| Women | 52.74 (51.58, 53.89) | 58.85 (38.58, 76.50) | |

| Race/ethnicity, % | 0.718 | ||

| White | 67.49 (63.22, 71.48) | 71.71 (56.2, 83.35) | |

| Black | 10.62 (8.5, 13.19) | 7.19 (3.43, 14.45) | |

| Mexican American | 6.65 (5.11, 8.60) | 5.90 (2.44, 13.59) | |

| Other | 15.25 (13.12, 17.65) | 15.21 (7.76, 27.65) | |

| History of arthritis, % | 0.032 | ||

| Yes | 38.81 (36.81, 40.81) | 42.39 (26.34, 58.43) | |

| No | 60.98 (58.98, 62.97) | 55.45 (39.11, 71.79) | |

| Unknownd | 0.22 (0.13, 0.30) | 2.16 (− 2.06, 6.39) | |

| History of congestive heart failure, % | 0.029 | ||

| Yes | 3.83 (3.28, 4.38) | 8.31 (− 0.01, 16.63) | |

| No | 95.91 (95.34, 96.48) | 89.82 (80.90, 98.75) | |

| Unknownd | 0.26 (0.12, 0.40) | 1.87 (− 1.29, 5.02) | |

| History of coronary heart disease, % | 0.008 | ||

| Yes | 5.94 (4.86, 7.03) | 12.96 (2.26, 23.66) | |

| No | 93.76 (92.66, 94.86) | 84.61 (73.16, 96.06) | |

| Unknownd | 0.30 (0.17, 0.42) | 2.43 (− 1.83, 6.70) | |

| History of angina/angina pectoris, % | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 3.17 (2.69, 3.65) | 0.68 (− 0.26, 1.62) | |

| No | 96.56 (96.05, 97.07) | 91.28 (86.43, 96.12) | |

| Unknownd | 0.27 (0.19, 0.35) | 8.04 (3.33, 12.75) | |

| History of heart attack, % | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 5.38 (4.56, 6.19) | 3.74 (− 1.89, 9.38) | |

| No | 94.49 (93.68, 95.31) | 90.03 (80.85, 99.20) | |

| Unknownd | 0.13 (0.04, 0.22) | 6.23 (− 1.18, 13.64) | |

| History of stroke, % | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4.99 (4.47, 5.50) | 4.31 (− 0.52, 9.15) | |

| No | 94.90 (94.36, 95.43) | 90.57 (86.08, 95.06) | |

| Unknownd | 0.12 (0.04, 0.19) | 5.12 (− 2.08, 12.32) | |

| History of cancer, % | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 16.45 (15.49, 17.40) | 23.47 (12.00, 34.93) | |

| No | 83.50 (82.54, 84.47) | 74.37 (62.42, 86.32) | |

| Unknownd | 0.05 (− 0.02, 0.12) | 2.16 (− 2.06, 6.39) |

% Weighted percentage.

aSubject aged 40 and older without definitive answer to the question on metal implants (refused to answer or answered “don’t know”) or with missing data on metal implants.

bUnweighted sample size.

cP value determined by survey-weighted linear regression (for continuous variables) or survey-weighted Chi-square test (for categorical variables).

dParticipants who (i) refused to answer the question, (ii) answered “don’t know.” to the question, or (iii) with missing data.

Prevalence of metal implants among individuals aged 40 and older

Overall, the prevalence of metal implants among those 40 years and older in 2015–2016 and 2017-March 2020 were 27.23% (95% CI: 23.61 to 30.85) and 31.53% (95% CI: 29.76 to 33.30), respectively. Furthermore, the prevalence of metal implants showed an increasing trend from 2015 to March 2020, especially for the older population (60 years and older) (from 37.19% to 43.40%), men (from 25.89% to 32.05%), Whites (from 29.76% to 36.00%), and Mexican American (from 19.07% to 23.64%). Moreover, the older population and Whites, regardless of survey cycles, showed a higher prevalence of metal implants than the younger population (40–59 years) and non-Whites, respectively. Results are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Prevalence of metal implants among US adults 40 years or older.

| NHANES 2015–2016 | NHANES 2017–March 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Unweighted sample size | Prevalence % (95% CI) | Unweighted sample size | Prevalence % (95% CI) | P-value |

| Overall | 3736 | 27.23 (23.61, 30.85) | 6387 | 31.53 (29.76, 33.30) | 0.049 |

| Age | |||||

| 40–59 years | 1853 | 19.50 (15.69, 23.31) | 2993 | 21.21 (19.06, 23.37) | 0.456 |

| 60 years and older | 1883 | 37.19 (32.77, 41.60) | 3394 | 43.40 (41.04, 45.76) | 0.022 |

| Sex | |||||

| Men | 1796 | 25.89 (22.04, 29.74) | 3154 | 32.05 (29.33, 34.78) | 0.017 |

| Women | 1940 | 28.43 (23.84, 33.02) | 3233 | 31.06 (28.96, 33.16) | 0.322 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 1277 | 29.76 (25.46, 34.05) | 2381 | 36.00 (33.06, 38.94) | 0.027 |

| Black | 795 | 20.71 (18.02, 23.39) | 1710 | 20.54 (18.34, 22.74) | 0.926 |

| Mexican American | 622 | 19.07 (16.69, 21.45) | 647 | 23.64 (21.36, 25.93) | 0.011 |

| Other | 1042 | 23.76 (18.32, 29.19) | 1649 | 23.46 (20.01, 26.90) | 0.927 |

CI, confidence interval; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Change in metal implant prevalence from 2015 to March 2020

The results of weighted logistic regression analysis showed that the overall prevalence of metal implants significantly increased from 2015 to March 2020, regardless of adjustment for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. In subgroup analysis, this study found that the prevalence of metal implants significantly increased among the older population (60 years and older), men, and Whites from 2015 to March 2020, regardless of adjustment for demographic factors. However, no significant increase in the prevalence of metal implants was observed among the younger population (40–59 years), women, and non-Whites from 2015 to March 2020. Other details are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Change in prevalence of metal implants.

| Population | Survey cycle | Model 1a | Model 2b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Overall | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.23 (1.01, 1.50) | 0.049 | 1.22 (1.01, 1.48) | 0.043 | |

| Agec | |||||

| 40–59 years | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.11 (0.84, 1.46) | 0.456 | 1.12 (0.85, 1.48) | 0.433 | |

| 60 years and older | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.30 (1.05, 1.60) | 0.022 | 1.31 (1.07, 1.62) | 0.015 | |

| Sexd | |||||

| Men | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.35 (1.07, 1.71) | 0.017 | 1.35 (1.09, 1.69) | 0.011 | |

| Women | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.13 (0.89, 1.45) | 0.322 | 1.12 (0.87, 1.44) | 0.377 | |

| Race/ethnicitye | |||||

| White | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.33 (1.04, 1.69) | 0.027 | 1.30 (1.03, 1.65) | 0.033 | |

| Non-White | 2015–2016 | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| 2017–March 2020 | 1.05 (0.86, 1.29) | 0.633 | 1.04 (0.84, 1.28) | 0.740 | |

aNo covariates were adjusted.

bAge, sex, and race/ethnicity were adjusted.

cAge was not adjusted in Model 2.

dSex was not adjusted in Model 2.

eRace/ethnicity was not adjusted in Model 2.

CI, confidence interval, OR, odds ratio.

Prevalence of metal implants and demographic factors

The results of weighted logistic regression models indicated that the metal implant prevalence differed by age and race/ethnicity, in which older individuals and White individuals showed a significantly higher prevalence of metal implants than younger individuals and non-White individuals, respectively. However, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of metal implants between men and women. The specific results are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Weighted logistic regression analysis of factors associated with metal implants prevalence.

| Demographic factor | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.05 (1.04, 1.06) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.04, 1.05) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Men | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| Women | 1.02 (0.89, 1.16) | 0.804 | 0.97 (0.85, 1.10) | 0.605 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | Reference (1) | – | Reference (1) | – |

| Non-White | 0.57 (0.49, 0.66) | < 0.001 | 0.66 (0.56, 0.77) | < 0.001 |

CI, confidence interval, OR, odds ratio.

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analysis, this study assessed the prevalence of metal implants after excluding participants with missing data on demographic characteristics and medical history. After excluding participants with missing data on demographic characteristics and medical history, a total of 9,950 participants were included in the subsequent analysis. The prevalences of metal implants were similar compared with the results in the primary analysis (Table 3). The detailed results are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to evaluate metal implant prevalence among US adults aged 40 and older. The main findings of this study indicated that there was a high prevalence of metal implants among US adults aged 40 and older, with approximately one-third of those reporting the presence of metal implants inside the body. Moreover, this study observed that the prevalence of metal implants significantly increased from 2015 to March 2020, especially among older individuals, males, and White individuals. In addition, the present study demonstrated that the prevalence of metal implants differed by age and race/ethnicity, in which older individuals and White individuals showed a significantly higher prevalence of metal implants than younger individuals and non-White individuals, respectively.

This study observed a high prevalence of metal implants among US adults aged 40 and older, with 27.23% (95% CI: 23.61 to 30.85) in 2015–2016 and 31.53% (95% CI: 29.76 to 33.30) in 2017-March 2020. Moreover, the present study also observed a significant increase in metal implant prevalence from 2015 to March 2020 among US adults aged 40 and older. On the one hand, the aging US population might be a possible reason for this high prevalence. Several musculoskeletal degenerative disorders, such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, are strongly associated with increasing age37–39. Furthermore, the cumulative evidence indicates an increasing trend of these diseases, such as osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, in the US population40–42. Therefore, a significant increase in the number of older adults greatly enhances the probability that individuals receive surgery, such as THA or TKA, where metal implants are commonly used10,11. However, it should be noted that several non-orthopaedic conditions, such as vascular stents or cardiac implantable electronic devices, may also be an important cause of the high prevalence of metal implants because of the widespread usage of these materials mentioned above in clinical practice43–45. On the other hand, advancements in medical technology, in particular with regard to medical materials, might be another possible reason contributing to the high prevalence of metal implants. The development of more effective and safer metal implants plays an essential role in prolonging the service life of metal implants, improving the clinical outcomes of patients, and contributing to the increased use of metal implants in surgery46,47.

Interestingly, the present study observed a significant increase in metal implant prevalence among men but not women from 2015 to March 2020. The specific reasons for the sex differences remained unclear. There were several possible reasons as follows. First, it is important to note that certain medical conditions necessitating the use of metal implants may exhibit a higher prevalence among men. For instance, conditions such as hip arthritis or specific types of bone fractures are potentially more frequent in the male population, thereby resulting in an increased incidence of metal implant procedures in men48. Second, we speculated that the sex differences in orthopaedic injuries might be a possible reason because men tend to engage more in physically demanding activities or sports compared with women, which might lead to an increased risk of orthopaedic injuries49–51. The statistical significance of sex differences might help guide clinical strategies and public health policies. However, it was uncertain whether the statistical significance of sex differences had practical clinical implications. Therefore, additional studies are required to investigate whether the prevalence of metal implants differed by sex and potential cause that led to the gender differences in the prevalence of metal implants.

This study found race or ethnicity differences in the prevalence of metal implants, in which White individuals showed a significantly higher metal implant prevalence than non-White individuals. The differences in healthcare access and socioeconomic factors, such as healthcare, economic conditions, or cultural factors, which might result in disparities in the utilization of metal implants, could be responsible for the race or ethnicity differences in the prevalence of metal implants52–54. Numerous studies have highlighted the persistent disparities in healthcare access and utilization among different racial and ethnic groups in the US, which might lead to the higher prevalence of metal implants observed in whites compared with other races. For instance, a study examining the access to health care and preventive services between Asian Americans/Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) and Non-Hispanic Whites found that AAPIs were significantly less likely to have a personal healthcare provider and to receive various preventive services compared to their white counterparts55. Furthermore, the racial disparities in income and wealth level, which were reported in numerous previous studies56,57, might be a reason for the differences in the prevalence of metal implants. However, this study did not evaluate the healthcare access and socioeconomic factors among the participants included in the NHANES because this study mainly focused on describing the overall prevalence of metal implants and assessing the change in metal implant prevalence rather than the exploring the reasons for the differences in the prevalence of metal implants. Moreover, there was a large number of participants with missing data on healthcare access and socioeconomic factors, while there was no participant with missing data on age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Therefore, deeper analyses are needed to explore the reasons for the race or ethnicity differences in the prevalence of metal implants.

The main findings of this study have several implications for future research. To our knowledge, the present study is the first study to evaluate the prevalence of metal implants among US adults. The large population with metal implants and the increase in the metal implant prevalence suggest that this special population, those with metal implants inside the body, might be neglected, and there is a need to pay more attention to health care and health management for this special population. In addition, race or ethnicity differences in metal implant prevalence are observed in the present study. Although the specific reasons for these differences remain unknown, this topic is worth exploring further, which might be beneficial for developing pertinent policies and improving access to and the quality of healthcare services.

This study has some limitations, as follows. First, metal implant data were collected based on self-report, which might introduce recall bias and thus lead to inaccurate prevalence estimates. Future studies investigating the prevalence of metal implants could employ different methods to provide a more accurate estimation of the prevalence of metal implants, such as reliable medical records. Second, this study did not assess the prevalence of metal implants among subjects aged below 40 years, as the questionnaire on metal implants was not evaluated among those below 40 years, according to the information provided on the NHANES58,59. Therefore, future research could expand the scope of the investigation to get a comprehensive understanding of the actual usage of metal implants. Third, this study assessed metal implant prevalence after excluding a small number of individuals without definitive answers to the question on metal implants or with missing data on metal implants, which might influence the prevalence estimate, albeit at lower percentages (0.75%, 76 of 10,199). Fourth, this study did not estimate metal implant prevalence before 2015 or after March 2020 because the questionnaire on metal implants was not evaluated before NHANES 2015–2016, and data from the NHANES after March 2020 was not released. Therefore, a longer-term investigation seemed to be necessary and beneficial to evaluate the changing trends of the prevalence of metal implants. Fifth, this study did not assess the health insurance coverage of the study population. In the future, it is worth investigating the impact of health insurance coverage on metal implant utilization.

Conclusions

The prevalence of metal implants among US adults aged 40 and older was high, with approximately one-third reporting the presence of metal implants inside the body, and the prevalence of metal implants significantly increased from 2015 to March 2020. Therefore, more attention needs to be paid to this special population, and it may be necessary to ensure accessibility and affordability and assess the potential long-term health impacts of metal implants, considering the increased prevalence of metal implants.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey participants and staff and the National Center for Health Statistics for their valuable contributions.

Author contributions

Qiu-Fu Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Yu-Chen Tang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Hao-Ran Liao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Miao Lei: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing; Wei Dong: Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Writing—Review & Editing; Ze-Yu Liu: Validation, Writing—Review & Editing; Jie Hao: Conceptualization, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision; Zhen-Ming Hu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Data availability

The datasets obtained and analyzed in the present study are open access and can be downloaded at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Qiu-Fu Wang and Yu-Chen Tang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jie Hao, Email: hjie2005@aliyun.com.

Zhen-Ming Hu, Email: spinecenter@163.com.

References

- 1.Su, Y. et al. Interfacial zinc phosphate is the key to controlling biocompatibility of metallic zinc implants. Adv. Sci.6(14), 1900112. 10.1002/advs.201900112 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis, R. et al. A comprehensive review on metallic implant biomaterials and their subtractive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol.120(3–4), 1473–1530. 10.1007/s00170-022-08770-8 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shekhawat, D., Singh, A., Bhardwaj, A. & Patnaik, A. A short review on polymer, metal and ceramic based implant materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng.1017, 012038. 10.1088/1757-899X/1017/1/012038 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skou, S. T. et al. A randomized, controlled trial of total knee replacement. N. Engl. J. Med.373(17), 1597–1606. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505467 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhandari, M. et al. Total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty for hip fracture. N. Engl. J. Med.381(23), 2199–2208. 10.1056/NEJMoa1906190 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allain, J. & Dufour, T. Anterior lumbar fusion techniques: Alif, olif, dlif, llif, ixlif. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. OTSR106(1s), S149–S157. 10.1016/j.otsr.2019.05.024 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lim, H. K., Choi, Y. J., Choi, W. C., Song, I. S. & Lee, U. L. Reconstruction of maxillofacial bone defects using patient-specific long-lasting titanium implants. Sci. Rep.12(1), 7538. 10.1038/s41598-022-11200-0 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsikandylakis, G., Overgaard, S., Zagra, L. & Kärrholm, J. Global diversity in bearings in primary tha. EFORT Open Rev.5(10), 763–775. 10.1302/2058-5241.5.200002 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim, J. K. et al. Is a titanium implant for total knee arthroplasty better? A randomized controlled study. J. Arthroplasty36(4), 1302–1309. 10.1016/j.arth.2020.11.010 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson, R. J. et al. Hip replacement. Lancet (London, England)392(10158), 1662–1671. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31777-x (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price, A. J. et al. Knee replacement. Lancet (London, England)392(10158), 1672–1682. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32344-4 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sloan, M., Premkumar, A. & Sheth, N. P. Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the US, 2014 to 2030. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am.100(17), 1455–1460. 10.2106/jbjs.17.01617 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh, J. A., Yu, S., Chen, L. & Cleveland, J. D. Rates of total joint replacement in the united states: Future projections to 2020–2040 using the national inpatient sample. J. Rheumatol.46(9), 1134–1140. 10.3899/jrheum.170990 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kurtz, S. M., Ong, K. L., Lau, E. & Bozic, K. J. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the united states: Updated projections to 2021. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am.96(8), 624–630. 10.2106/jbjs.M.00285 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inacio, M. C. S., Paxton, E. W., Graves, S. E., Namba, R. S. & Nemes, S. Projected increase in total knee arthroplasty in the United States—An alternative projection model. Osteoarthr. Cartil.25(11), 1797–1803. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.07.022 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bashinskaya, B., Zimmerman, R. M., Walcott, B. P. & Antoci, V. Arthroplasty utilization in the united states is predicted by age-specific population groups. ISRN Orthop.10.5402/2012/185938 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz, S., Ong, K., Lau, E., Mowat, F. & Halpern, M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the united states from 2005 to 2030. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am.89(4), 780–785. 10.2106/jbjs.F.00222 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maradit Kremers, H. et al. Prevalence of total hip and knee replacement in the united states. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am.97(17), 1386–1397. 10.2106/jbjs.N.01141 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He, J., Li, J., Wu, S., Wang, J. & Tang, Q. Accumulation of blood chromium and cobalt in the participants with metal objects: Findings from the 2015 to 2018 national health and nutrition examination survey (nhanes). BMC Geriatr.23(1), 72. 10.1186/s12877-022-03710-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacheco, K. A. Allergy to surgical implants. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol.56(1), 72–85. 10.1007/s12016-018-8707-y (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lachiewicz, P. F., Watters, T. S. & Jacobs, J. J. Metal hypersensitivity and total knee arthroplasty. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg.24(2), 106–112. 10.5435/jaaos-d-14-00290 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapadia, B. H. et al. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet (London, England)387(10016), 386–394. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61798-0 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraser, J. F., Werner, S. & Jacofsky, D. J. Wear and loosening in total knee arthroplasty: A quick review. J. Knee Surg.28(2), 139–144. 10.1055/s-0034-1398375 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bjorgul, K. et al. High rate of revision and a high incidence of radiolucent lines around metasul metal-on-metal total hip replacements: Results from a randomised controlled trial of three bearings after seven years. Bone Jt. J.95-b(7), 881–886. 10.1302/0301-620x.95b7.31067 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovochich, M. et al. Understanding outcomes and toxicological aspects of second generation metal-on-metal hip implants: A state-of-the-art review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol.48(10), 853–901. 10.1080/10408444.2018.1563048 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang, Y. et al. Functionally tailored metal-organic framework coatings for mediating ti implant osseointegration. Adv. Sci.10(29), e2303958. 10.1002/advs.202303958 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu, S. et al. Long-lasting renewable antibacterial porous polymeric coatings enable titanium biomaterials to prevent and treat peri-implant infection. Nat. Commun.12(1), 3303. 10.1038/s41467-021-23069-0 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen, X. et al. Fabrication of magnesium/zinc-metal organic framework on titanium implants to inhibit bacterial infection and promote bone regeneration. Biomaterials212, 1–16. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.05.008 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CDC. Nchs ethics review board (erb) approval, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/irba98.htm [Accessed December 17].

- 30.CDC. Nhanes 2015–2016 brochures and consent documents, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/Documents.aspx?BeginYear=2015 [Accessed December 17].

- 31.CDC. Nhanes 2017-march 2020 pre-pandemic brochures and consent documents, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/documents.aspx?Cycle=2017-2020 [Accessed December 17].

- 32.von Elm, E. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet (London, England)370(9596), 1453–1457. 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.CDC. Sample person questionnaire-medical conditions (nhanes 2015-2016), https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2015-2016/questionnaires/MCQ_I.pdf [Accessed December 17].

- 34.CDC. Sample person questionnaire-medical conditions (nhanes 2017-2018), https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2017-2018/questionnaires/MCQ_J.pdf [Accessed December 17].

- 35.CDC. Sample person questionnaire-medical conditions (nhanes 2019-2020), https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2019-2020/questionnaires/MCQ_K.pdf [Accessed December 17].

- 36.National Center for Health Statistics CfDCaP. Nhanes survey methods and analytic guidelines, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analyticguidelines.aspx#analytic-guidelines [Accessed December 17].

- 37.Compston, J. E., McClung, M. R. & Leslie, W. D. Osteoporosis. Lancet (London, England)393(10169), 364–376. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32112-3 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hunter, D. J. & Bierma-Zeinstra, S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet (London, England)393(10182), 1745–1759. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30417-9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Compston, J. et al. Uk clinical guideline for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Arch. Osteopor.12(1), 43. 10.1007/s11657-017-0324-5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Looker, A. C., Sarafrazi Isfahani, N., Fan, B. & Shepherd, J. A. Trends in osteoporosis and low bone mass in older us adults, 2005–2006 through 2013–2014. Osteopor. Int.28(6), 1979–1988. 10.1007/s00198-017-3996-1 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu, Y. & Wu, Q. Trends and disparities in osteoarthritis prevalence among us adults, 2005–2018. Sci. Rep.11(1), 21845. 10.1038/s41598-021-01339-7 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safiri, S. et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis.79(6), 819–828. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusumoto, F. M. et al. 2017 hrs expert consensus statement on cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead management and extraction. Heart Rhythm14(12), e503–e551. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.09.001 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gori, T. et al. Predictors of stent thrombosis and their implications for clinical practice. Nat. Rev. Cardiol.16(4), 243–256. 10.1038/s41569-018-0118-5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torrado, J. et al. Restenosis, stent thrombosis, and bleeding complications: Navigating between scylla and charybdis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.71(15), 1676–1695. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.023 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang, X. et al. A novel decellularized matrix of wnt signaling-activated osteocytes accelerates the repair of critical-sized parietal bone defects with osteoclastogenesis, angiogenesis, and neurogenesis. Bioact. Mater.21, 110–128. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.07.017 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Surmeneva, M. A. et al. Fabrication of multiple-layered gradient cellular metal scaffold via electron beam melting for segmental bone reconstruction. Mater. Des.133, 195–204. 10.1016/j.matdes.2017.07.059 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ensrud, K. E. et al. Degree of trauma differs for major osteoporotic fracture events in older men versus older women. J. Bone Miner. Res.31(1), 204–207. 10.1002/jbmr.2589 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zech, A. et al. Sex differences in injury rates in team-sport athletes: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J. Sport Health Sci.11(1), 104–114. 10.1016/j.jshs.2021.04.003 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stanley, L. E., Kerr, Z. Y., Dompier, T. P. & Padua, D. A. Sex differences in the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament, medial collateral ligament, and meniscal injuries in collegiate and high school sports: 2009–2010 through 2013–2014. Am. J. Sports Med.44(6), 1565–1572. 10.1177/0363546516630927 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wentz, L., Liu, P. Y., Haymes, E. & Ilich, J. Z. Females have a greater incidence of stress fractures than males in both military and athletic populations: A systemic review. Mil. Med.176(4), 420–430. 10.7205/milmed-d-10-00322 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manuel, J. I. Racial/ethnic and gender disparities in health care use and access. Health Serv. Res.53(3), 1407–1429. 10.1111/1475-6773.12705 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mahajan, S. et al. Trends in differences in health status and health care access and affordability by race and ethnicity in the United States, 1999–2018. JAMA326(7), 637–648. 10.1001/jama.2021.9907 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wallace, J., Jiang, K., Goldsmith-Pinkham, P. & Song, Z. Changes in racial and ethnic disparities in access to care and health among us adults at age 65 years. JAMA Intern. Med.181(9), 1207–1215. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3922 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wen, X. J. & Balluz, L. Racial disparities in access to health care and preventive services between asian americans/pacific islanders and non-hispanic whites. Ethn. Dis.20(3), 290–295 (2010). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Levy, B. L. Wealth, race, and place: How neighborhood (dis)advantage from emerging to middle adulthood affects wealth inequality and the racial wealth gap. Demography59(1), 293–320. 10.1215/00703370-9710284 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boen, C., Keister, L. & Aronson, B. Beyond net worth: Racial differences in wealth portfolios and black-white health inequality across the life course. J. Health Soc. Behav.61(2), 153–169. 10.1177/0022146520924811 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.CDC. Medical conditions 2015–2016, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2015-2016/MCQ_I.htm#OSQ230 [Accessed December 17].

- 59.CDC. Medical conditions 2017-march 2020, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2017-2018/P_MCQ.htm [Accessed December 17].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets obtained and analyzed in the present study are open access and can be downloaded at: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/.