Abstract

Background

Dysregulated energy metabolism has emerged as a defining hallmark of cancer, particularly evident in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Distinct from other breast cancer subtypes, TNBC exhibits heightened glycolysis and aggressiveness. However, the transcriptional mechanisms of aerobic glycolysis in TNBC remains poorly understood.

Methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort was utilized to identify genes associated with glycolysis. The role of FOSL1 in glycolysis and tumor growth in TNBC cells was confirmed through both loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments. The subcutaneous xenograft model was established to evaluate the therapeutic potential of targeting FOSL1 in TNBC. Additionally, chromatin immunoprecipitation and luciferase reporter assays were employed to investigate the transcriptional regulation of glycolytic genes mediated by FOSL1.

Results

FOSL1 is identified as a pivotal glycolysis-related transcription factor in TNBC. Functional verification shows that FOSL1 enhances the glycolytic metabolism of TNBC cells, as evidenced by glucose uptake, lactate production, and extracellular acidification rates. Notably, FOSL1 promotes tumor growth in TNBC in a glycolysis-dependent manner, as inhibiting glycolysis with 2-Deoxy-D-glucose markedly diminishes the oncogenic effects of FOSL1 in TNBC. Mechanistically, FOSL1 transcriptionally activates the expression of genes such as SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA, which further accelerate the glycolytic flux. Moreover, FOSL1 is highly expressed in doxorubicin (DOX)-resistant TNBC cells and clinical samples from cases of progressive disease following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Targeting FOSL1 proves effective in overcoming chemoresistance in DOX-resistant MDA-MB-231 cells.

Conclusion

In summary, FOSL1 establishes a robust link between aerobic glycolysis and carcinogenesis, positioning it as a promising therapeutic target, especially in the context of TNBC chemotherapy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12967-024-06014-9.

Keywords: Energy metabolism, Drug resistance, Glucose metabolism, Glucose transporter, Gene promoter

Introduction

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a particularly aggressive subtype of breast cancer, distinguished by the absence of estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) [1, 2]. This lack of receptor expression renders traditional endocrine and targeted therapies largely ineffective, leaving chemotherapy as the primary treatment option [3, 4]. The ability to effectively reverse chemotherapy resistance is paramount for enhancing the prognosis of patients with TNBC [5, 6]. Addressing this challenge could pave the way for more successful therapeutic strategies, ultimately improving outcomes for those affected by this formidable disease.

Metabolic reprogramming is a pivotal factor in tumor development, with Warburg metabolism standing out as a quintessential example of such alterations, particularly in the context of TNBC [7]. This aggressive subtype is increasingly recognized for its reliance on glycolysis, and numerous studies have delved into the transcriptional regulation of key metabolic enzymes involved in this process [8]. The transcription factor SIX1 is noteworthy for its ability to modulate glycolytic gene expression through interactions with histone acetyltransferases HBO1 and AIB1, ultimately promoting the Warburg effect and enhancing tumor growth both in vitro and in vivo [9]. Additionally, transcription factors MYC and HIF1α are known to directly influence the expression of critical glycolytic enzymes, further driving the malignancy of TNBC [10–12]. Other transcriptional factors, such as POU1F1 and ETV4, also contribute to the metabolic landscape by regulating the expression of LDHA, HK2, and GLUT1, thereby fostering glycolysis and tumor progression [13, 14]. Our previous research has highlighted the role of miR-210-3p and MIR210HG in augmenting HIF1α activity, which in turn boosts the glycolytic capacity of TNBC cells [15, 16]. Given the intricate relationship between glucose metabolism and the pathogenesis of TNBC, it becomes imperative to identify and screen key regulatory factors that link the Warburg effect to the onset and progression of this disease. However, the current body of research on the transcriptional mechanisms governing the Warburg effect in TNBC remains fragmented, underscoring the need for systematic investigations to unravel these complex interactions and inform the development of innovative therapeutic strategies.

FOSL1, or Fos-like antigen 1 (Fra-1), is a transcription factor within the Fos protein family, renowned for its ability to form heterodimers with other constituents of the AP-1 complex, including JUN and JUNB [17, 18]. This dynamic interaction enables FOSL1 to intricately regulate target gene expression in response to a myriad of stimuli, such as growth factors and cytokines [19]. Dysregulation of FOSL1 has been linked to various diseases, particularly cancer, where it plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis by fostering cell survival and proliferation [20]. In TNBC, the amplification of copy numbers significantly elevates FOSL1 expression, further complicating the disease’s pathology [21]. FOSL1 is essential for numerous biological processes, including tumor resistance, growth, migration, and invasion [18, 22–24]. Notably, strategically targeting the signaling cascade mediated by FOSL1 has the potential to enhance the sensitivity of TNBC cells to PARP inhibitors [25], thus offering a promising avenue for improving treatment outcomes in this aggressive cancer subtype.

In this study, we categorized TNBC samples according to their glycolysis phenotype and undertook an in-depth characterization of the transcription factors involved in aerobic glycolysis within TNBC. Our functional validation demonstrated that FOSL1 is instrumental in regulating the expression of glycolytic genes through transcriptional mechanisms, thereby facilitating both glycolysis and tumor growth. Notably, targeting FOSL1 effectively reversed chemotherapy resistance in TNBC cells. Using a FOSL1 PROTAC probe, T-5224, significantly enhanced the sensitivity of TNBC cells to DOX treatment.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

RNA sequencing data for TNBC and adjacent non-malignant tissues were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://gdc.cancer.gov/). A specific glycolysis gene signature, including SLC2A1, HK2, GPI, PFKL, ALDOA, PGK1, PGAM1, ENO1, PKM2, and LDHA, was utilized to categorize the samples into glycolysis-high (n = 57) and glycolysis-low (n = 56) groups [15]. Differentially expressed genes associated with glycolysis were identified using an exact test, with a significance threshold set at P < 0.05 and a minimum 2-fold change in expression levels.

Cell lines and reagents

TNBC cell lines (Hs578T, MDA-MB-21, and HCC1937) and non-TNBC cell lines (MCF7, T47D, and ZR-75-1), along with the non-malignant MCF-10 A, MDA-MB-231-DR, and HEK293T cells, were acquired from the Cell Resource Center at the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Shanghai, China. Authentication of the cell lines and mycoplasma testing were conducted to ensure their validity. For cell culture, RPMI-1640 and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, both sourced from Hyclone (USA). Cells were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum from Gibco (USA), along with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin from Invitrogen (USA). The cells were maintained in a culture incubator set to 37 °C with an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All reagents used in this study were obtained from MCE (New Jersey, USA), including T-5224 (Cat. HY-12270), 2-Deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG, Cat. HY-13966), doxorubicin (DOX, Cat. HY-15142 A), and cisplatin (DDP, Cat. HY-17394).

Clinical specimens

Human breast cancer specimens were obtained from the Department of Breast Surgery at the General Surgery Center of The First Hospital of Jilin University, following the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the ethics committee of The First Hospital of Jilin University (Approval number: 2023 − 395), and all participants provided written informed consent before undergoing surgery. None of the patients had received radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, or any other related anti-cancer treatments prior to their surgery. The patients included in our study are classified as sporadic cases; they are all Chinese and originate from Jilin Province. The clinicopathological data of the patients, including their classification as luminal, HER2+, or TNBC, can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Loss-of-function and gain-of-function experiments

For loss-of-function studies, specific siRNAs or shRNAs targeting the designated genes were synthesized by GenePharma Inc (Shanghai, China). Transient knockdown of siRNA was performed by transfecting cells with the siRNAs using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, USA), adhering to the manufacturer’s instructions. To generate stable cell lines, shRNA constructs along with lentivirus packaging plasmids were introduced into HEK293T cells. After 48 h of transfection, the supernatants containing the virus were collected and used to infect target cells in the presence of 5 µg/ml polybrene (Cat. E1299, Selleck, Shanghai, China). The transfected cells were then selected using 2 µg/ml puromycin (Cat. S7417, Selleck, Shanghai, China). The sequences for siRNA and shRNA are provided below: si-FOSL1, GAGCUGCAGUGGAUGGUAC; sh-FOSL1-1, ACTCATGGTGTTGATGCTTGG; sh-FOSL1-2, AATGAGGCTGTACCATCCACT. For the overexpression of FOSL1, cells were transfected with the pcDNA3.1-FOSL1 plasmid using Lipofectamine 3000, while an empty control plasmid was used to establish control lines.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from TNBC cells and tissues using the RNAiso Plus kit (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). The concentration and quality of the RNA were assessed through spectrophotometry with a NanoDrop™ 2000 device (Thermo Scientific, USA). For the detection of mRNA, reverse transcription was performed using the PrimeScript RT Master kit (Takara Bio Inc., Japan) The expression levels of RNA were measured with the universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix and analyzed using the ViiA7 System (AB Applied Biosystems, USA). The relative mRNA levels were normalized against β-actin. The specific primer sequences used in this study can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

Western blot

Total proteins were extracted from TNBC cells using RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), which included both protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The protein concentration was determined with the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The proteins were then separated using 6-10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluorid membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk, the membranes were incubated with specific primary antibodies. The primary antibodies utilized included FOSL1 (ab252421, Abcam) and anti-β-actin (ab8227, Abcam). The following day, the membranes were treated with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature. Finally, the protein blots were developed using the ECL kit (Millipore, USA) allowing for the visualization of the target proteins.

Detection of glucose, lactate, and extracellular acidification rate

As reported previously [15, 16], glucose and lactate concentrations were assessed using a commercial glucose assay kit from Sigma-Aldrich (MAK263, Shanghai, China) and a Lactate Assay Kit from BioVision (K607-100, USA), following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Additionally, the extracellular acidification rate was measured with a Seahorse XF96 analyzer from Seahorse Biosciences, USA. To ensure accuracy, all measurements were normalized to the total protein content in the samples.

Animal experiments

To investigate the in vivo functions of FOSL1, male Balb/c nude mice aged six weeks were utilized, following the guidelines set forth in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” by the National Academy of Sciences. The mice were maintained under a 12-hour light/dark cycle with unrestricted access to food and water. For the establishment of a subcutaneous xenograft model, 2 × 106 specified TNBC cells were in phosphate-buffered saline and injected subcutaneously into the lower back region of the mice. To assess the effects of 2-DG treatment, mice received intraperitoneal injections of 500 mg/kg 2-DG every other day. For pharmacological inhibition of FOSL1, once the tumor volume reached approximately 50 mm², the mice were randomly assigned to three groups. The mice received intraperitoneal injections of either 50 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of T-5224 every other day. After a duration of 30 days, the mice were euthanized, and the tumor weights were measured. Tumor volumes were calculated using the formula: volume (mm³) = length (mm) × width (mm)²/2. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Jilin University.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

As reported previously [16, 26], the IHC experiment was conducted on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole tissue sections, following established protocols. Initially, the tissue sections underwent deparaffinization, followed by antigen retrieval using a citrate-based solution with heat treatment at 95 °C for 20 min. To inhibit endogenous peroxidase activity, the sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide at room temperature for 15 min. After washing, the sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humid chamber with primary antibodies. The following day, the slides were exposed to a secondary antibody conjugated with HRP at room temperature for one hour. Visualization was achieved through DAB staining, followed by hematoxylin counterstaining, and imaging of the sections. Scoring of the IHC results was performed as previously described [16], with two senior pathologists independently evaluating the scores in a blinded manner to ensure objectivity. The primary antibodies utilized in this study included FOSL1 (ab252421, Abcam; diluted at 1:500), GLUT1 (Cat. 66290-1-Ig, Proteintech; diluted at 1:1,000), ENO1 (Cat. 11204-1-AP, Proteintech; diluted at 1:500), and LDHA (66287-1-Ig, Proteintech; diluted at 1:200).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The ChIP experiment was conducted using the Pierce Agarose ChIP Kit (Cat. 26156). HS578T and MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min to crosslink proteins to DNA, after which 1.25 mol/L glycine was added to halt the crosslinking reaction. Chromatin shearing was achieved through sonication using the Bioruptor® from Diagenode, resulting in DNA fragments ranging from 300 to 600 bp. Following centrifugation at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C, the cell supernatants were collected. The immunoprecipitation of DNA was carried out overnight at 4 °C using anti-phospho-FOSL1 (#5841, Cell Signaling Technology) or an isotype-matched control IgG from the sonicated lysates. Subsequently, the mixture was incubated with protein A/G-agarose beads for an additional three hours at 4 °C. The purified DNA underwent de-crosslinking at 65 °C for 12 h and was then analyzed using Premix Taq™ PCR (Takara, Japan). Primers were specifically designed to amplify the predicted binding sites of FOSL1 located at the promoter region of the SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA gene.

Luciferase reporter assay

The binding sites of FOSL1 within the promoter regions of the specified genes were identified using the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.elixir.no/). MCF-10 A cells were cultured in 24-well plates and, upon reaching 50–70% confluence, were transfected with the designated promoter luciferase reporter plasmids, either containing FOSL1 or an empty vector, along with β-galactosidase reporter plasmids for normalization purposes. After a 24-hour incubation period, the cells were lysed to extract the necessary components for measuring luciferase activity. The luciferase reporter assay was performed following the guidelines provided by the manufacturer (Promega, USA). The resulting data were analyzed by calculating the ratio of luciferase signal to β-galactosidase signal.

Cell growth inhibition assay

Cell growth was assessed using the Cell Count Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. In this procedure, MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and MDA-MB-231-DR cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 3,000 cells per well. Following treatment with drugs (DOX and DDP) at specified time intervals, cell viability was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay according to the manufacturer’s guidelines (Dojindo, Japan). After a 1.5-hour incubation period, the resulting reaction product was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). To compare the data across different groups, either a two-sided Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA, or two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was employed. Additionally, Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the correlation in expression levels between the specified proteins. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were analyzed using the log-rank test to compare the survival distributions between different groups. A P-value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant for all analyses. Significance levels were indicated as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Results

Identification of glycolysis-associated transcriptional factors in TNBC

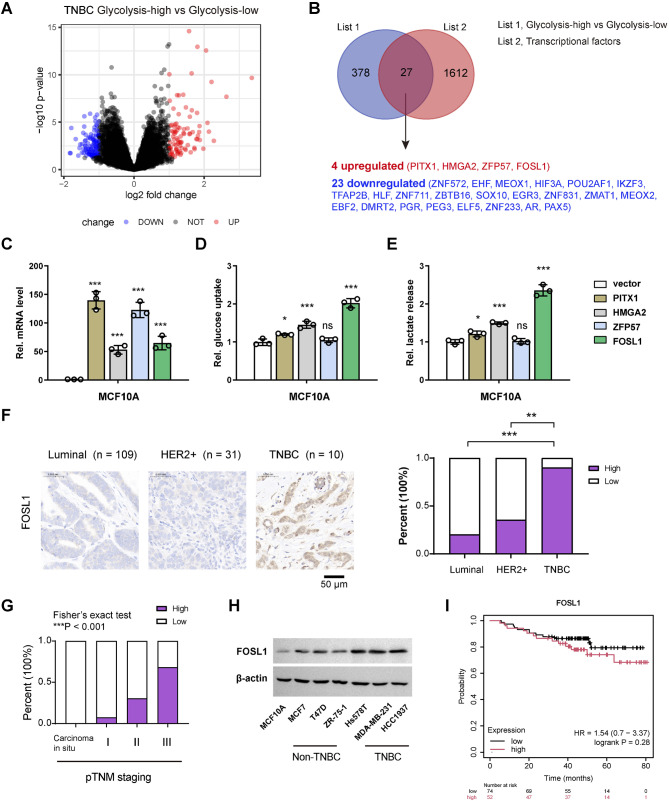

To explore the transcriptional factors implicated in the glycolytic metabolism of TNBC, we initiated our investigation by analyzing data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). As previously reported 15, TNBC samples were categorized into two distinct groups: a glycolysis-high group (n = 57) and a glycolysis-low group (n = 56), based on a validated glycolysis gene signature. This comprehensive analysis unveiled 404 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) related to glycolysis (Fig. 1A, Supplementary Table 3). By integrating these DEGs with genes encoding transcription factors, we identified 24 glycolysis-related transcriptional factors in TNBC: 4 upregulated (PITX1, HMGA2, ZFP57, FOSL1) and 23 downregulated (ZNF572, EHF, MEOX1, HIF3A, POU2AF1, IKZF3, TFAP2B, HLF, ZNF711, ZBTB16, SOX10, EGR3, ZNF831, ZMAT1, MEOX2, EBF2, DMRT2, PGR, PEG3, ELF5, ZNF233, AR, PAX5) (Fig. 1B). From the perspective of therapeutic targeting, we focused on the four upregulated transcriptional factors. To assess their influence on glycolysis, we overexpressed these genes in the immortalized breast epithelial cell line MCF-10 A (Fig. 1C), utilizing glucose uptake and lactate production as indicators of glycolytic activity. Our results indicated that PITX1, HMGA2, and FOSL1 all enhanced glycolysis, with FOSL1 demonstrating the most pronounced effect (Fig. 1D and E). Therefore, we selected FOSL1 for further investigation. To elucidate the expression patterns of FOSL1, we performed IHC analysis in a breast cancer cohort (n = 150). The results revealed a significant nuclear localization of FOSL1, indicating its nuclear functions. Notably, the expression level of FOSL1 in TNBC subtype was markedly elevated compared to other breast cancer types (luminal and HER2+) (Fig. 1F). Through the analysis of FOSL1 immunostaining in relation to the corresponding pTNM staging, we found that FOSL1 expression levels were significantly elevated in samples with advanced pathologic TNM stages (Fig. 1G). Western blot analyses also demonstrated that the protein level of FOSL1 was higher in TNBC cell lines (Hs578T, MDA-MB-231, and HCC1937) than in non-TNBC cell lines (MCF7, T47D, and ZR-75-1) and the nonmalignant MCF-10 A cells (Fig. 1H). Kaplan-Meier curve analysis indicated that higher levels of FOSL tend to correlate with shorter overall survival, although the statistical difference was not significant (Fig. 1I).

Fig. 1.

Identification of glycolysis-associated TFs in TNBC. (A) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes related to TNBC glycolysis. (B) Venn diagram showing the 27 glycolysis-related IFs in TNBC. (C) Real-time qPCR analysis of the overexpression efficiency of PITX1, HMGA2, ZFP57, and FOSL1 in MCF-10 A cells. (D, E) The effects of PITX1, HMGA2, ZFP57, and FOSL1 overexpression on the glucose uptake (D) and lactate production (E) of MCF-10 A cells. (F) IHC analysis of FOSL1 expression levels in different breast cancer subtypes. Scale bar, 50 μm. (G) Analysis of FOSL1 immunostaining and the corresponding pTNM staging. (H) Western blotting analysis of FOSL1 protein in different breast cancer cell lines. Scale bar, 50 μm. (I) Kaplan-Meier curve analysis of the prognostic value of FOSL1 in TNBC. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001

FOSL1 promotes aerobic glycolysis in TNBC cells

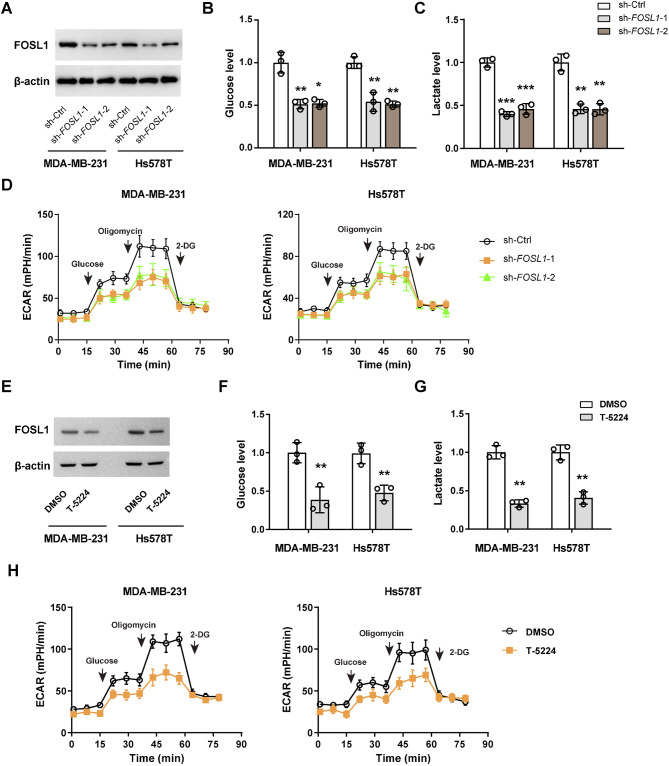

To determine the role of FOSL1 in the glycolytic metabolism of TNBC cells, we conducted shRNA-mediated loss-of-function studies. Western blot analyses confirmed that the protein expression levels of FOSL1 was effectively downregulated by two specific shRNAs (Fig. 2A). Notably, silencing of FOSL1 resulted in a modest reduction of approximately 50–60% in glucose uptake and lactate release in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells (Fig. 2B and C). Furthermore, Seahorse assays demonstrated that the extracellular acidification rate was significantly inhibited following FOSL1 knockdown (Fig. 2D). Through gain-of-function studies, we observed that the overexpression of FOSL1 in T47D and ZR-75-1 cells markedly enhanced glycolytic metabolism, as evidenced by increased glucose uptake, elevated lactate production, and heightened extracellular acidification rate (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

FOSL1 promotes aerobic glycolysis in TNBC cells. (A) Western blotting analysis showing the knockdown efficiency of FOSL1 in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells. (B-D) Measurement of glucose uptake (B), lactate production (C), extracellular acidification rate (D), in sh-Ctrl and sh-FOSL1 MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells. (E) Western blotting analysis showing FOSL1 protein expression upon T-5224 treatment in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells. (F-H) Measurement of glucose uptake (F), lactate production (G), extracellular acidification rate (H), in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells upon T-5224 treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001

To further validate the connection between FOSL1 and glycolysis, we utilized a FOSL1 PROTAC probe, T-5224, designed to induce FOSL1 degradation [27]. Following a 24-hour treatment with T-5224 in Hs578T and MDA-MB-231 cells, FOSL1 protein levels were dramatically reduced (Fig. 2E). Consistent with the reduction of FOSL1, T-5224 treatment also significantly inhibited glucose uptake, lactate production, and extracellular acidification rate in both MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells (Fig. 2F-H). Collectively, these findings underscore the critical involvement of FOSL1 in the glycolytic metabolism of TNBC cells.

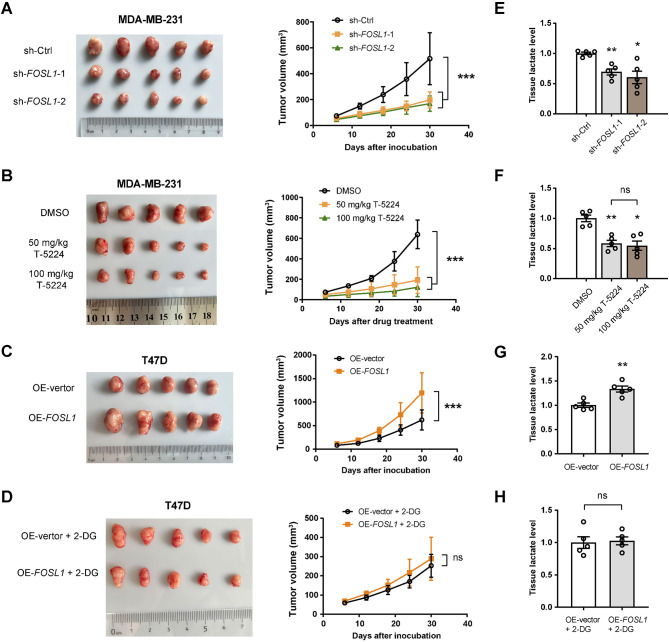

FOSL1 promotes TNBC growth in a glycolysis-dependent manner

To investigate the potential oncogenic role of FOSL1 in TNBC, we established a subcutaneous xenograft tumor model by injecting either sh-Ctrl or sh-FOSL1 MDA-MB-231 cells into nude mice, with five mice per group. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the knockdown of FOSL1 significantly inhibited the growth kinetics of the resulting tumors. In a complementary approach, we inoculated wild-type MDA-MB-231 cells into another set of nude mice (n = 5 per group). Once the tumors reached a volume of 50 mm³, we administered T-5224 at dosages of 50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg via intraperitoneal injection every other day for a duration of 30 days. Remarkably, treatment with T-5224 resulted in a substantial decrease in tumor growth, with no significant difference observed in the inhibitory effects between the 50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg dosage levels (Fig. 3B). Conversely, we also generated subcutaneous xenograft tumors using OE-vector and OE-FOSL1 T47D cells, revealing that FOSL1 overexpression resulted in an approximate 30% increase in tumor burden (Fig. 3C). Next, we explored whether the growth advantage conferred by FOSL1 is associated with enhanced glycolytic activity. To address this, we inhibited in vivo glycolysis through intraperitoneal injections of 500 mg/kg 2-DG every other day. Remarkably, this intervention substantially diminished the growth-promoting effects associated with FOSL1 overexpression (Fig. 3D). Through lactate level assessments in xenograft tumor tissues, we observed that both the knockdown of FOSL1 and the application of T-5224 led to a significant reduction in lactate levels (Fig. 3E and F). Conversely, overexpression of FOSL1 resulted in an increase in lactate levels (Fig. 3G). There was no discernible difference in tissue lactate levels between the OE-vector + 2-DG and OE-FOSL1 + 2-DG groups (Fig. 3H). Collectively, these findings highlight FOSL1 as a potential therapeutic target in this aggressive cancer subtype, suggesting that its oncogenic roles may be dependent on glycolysis.

Fig. 3.

FOSL1 promotes TNBC growth in a glycolysis-dependent manner. (A) Xenograft tumor model showing the impact of FOSL1 knockdown on tumor growth, originating from MDA-MB-231 cells (n = 5 per group). (B) The growth curve of MDA-MB-231 tumors following treatment with 50 mg/kg or 100 mg/kg of T-5224 over a period of 30 days (n = 5 per group). (C) Xenograft tumor model showing the impact of FOSL1 overexpression on tumor growth, originating from T47D cells (n = 5 per group). (D) The impact of FOSL1 overexpression on the growth of T47D tumors when treated with 500 mg/kg of 2-DG. (E) Measurement of lactate levels in sh-Ctrl and sh-FOSL1 MDA-MB-231 tumor tissues. (F) Measurement of lactate levels in MDA-MB-231 tumors following treatment with T-5224. (G, H) Measurement of lactate levels in OE-vector and OE-FOSL1 T47D tumor tissues with (G) or without (H) 2-DG treatment. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01; ns, not significant

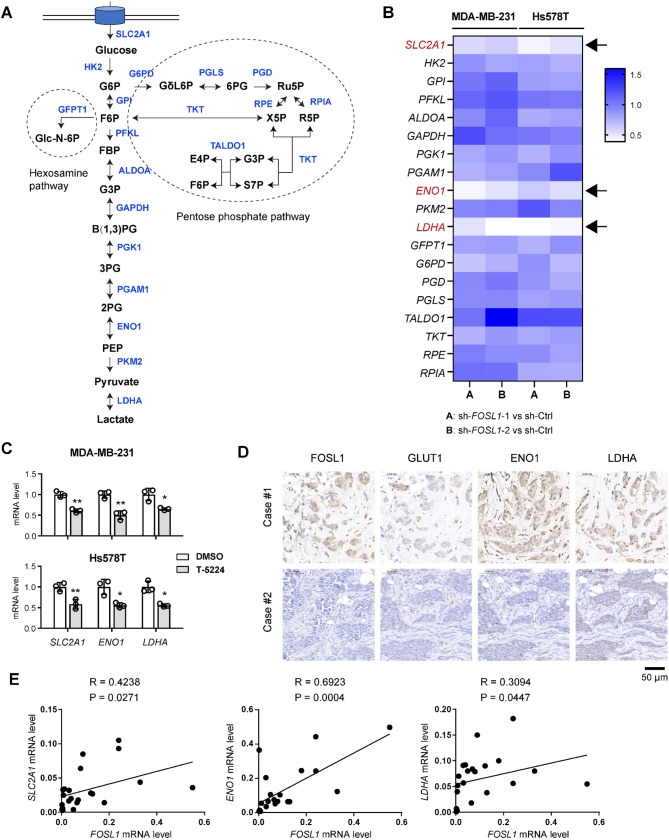

FOSL1 transcriptionally regulates glycolytic genes in TNBC

To understand the regulatory role of FOSL1 in glycolytic metabolism, we investigated whether FOSL1 transcriptionally modulates the expression of key glycolytic enzymes to enhance glycolysis. We examined the expression levels of genes associated with the hexosamine pathway, glycolysis pathway, and pentose phosphate pathway following FOSL1 knockdown (Fig. 4A). The results revealed a consistent and significant downregulation of several glycolytic genes, including SLC2A1 (encoding glucose transporter GLUT1), alpha-enolase (ENO1), and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA), upon FOSL1 knockdown (Fig. 4B). Similarly, treatment with T-5224 led to a marked reduction in the expression of these genes (Fig. 4C). Conversely, overexpression of FOSL1 resulted in the upregulation of their expression (Supplementary Fig. 2A). There is a close correlation between FOSL1 mRNA level and the expression of those three genes in the TCGA cohort (Supplementary Fig. 2B). IHC analysis further corroborated these findings, demonstrating that TNBC samples exhibiting higher FOSL1 expression levels corresponded with elevated GLUT1, ENO1, and LDHA protein levels (Fig. 4D). This correlation was substantiated by real-time qPCR analysis conducted on a cohort of TNBC patients (n = 22) (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

FOSL1 regulates the expression of glycolytic genes. (A) A schematic diagram showing the glycolysis pathway, hexosamine pathway, and pentose phosphate pathway. (B) Real-time qPCR analysis of the expression of genes involved in the glycolysis pathway (SLC2A1, HK2, GPI, PFKL, ALDOA, GAPDH, PGK1, PGAM1, ENO1, PKM2, and LDHA), hexosamine pathway (GFPT1), and pentose phosphate pathway (G6PD, PGD, PGLS, TALDO1, TKT, RPE, and RPIA) in sh-Ctrl and sh-FOSL1 MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells. (C) Real-time qPCR analysis of SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA gene expression in MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T cells following treatment with T-5224. (D) IHC analysis showed the expression correlation between FOSL1 and the glycolytic components (SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA). Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Correlation analysis of FOSL1 expression with SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA in 22 TNBC samples. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01

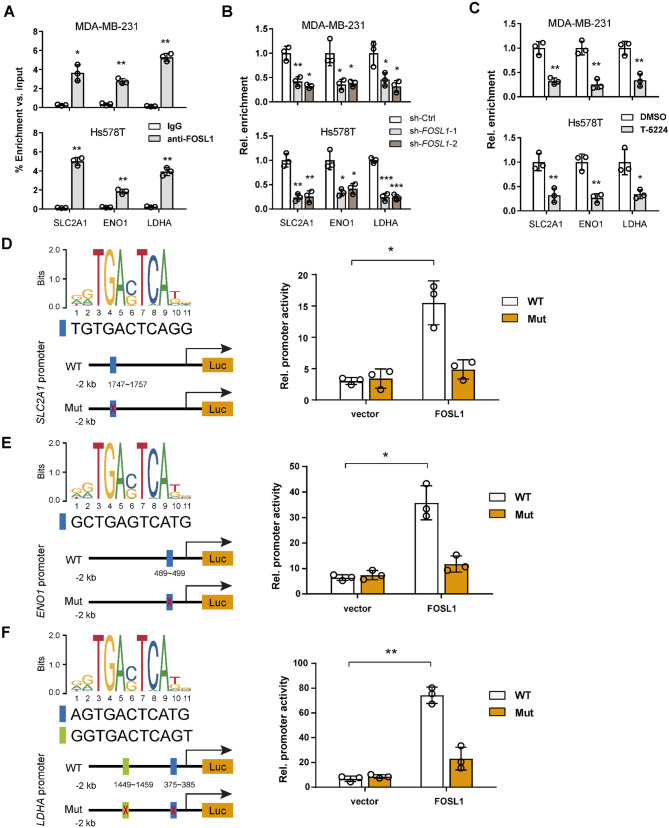

To elucidate whether FOSL1 directly regulates these glycolytic genes at the transcriptional level, we performed ChIP-PCR assays. Indeed, ChIP-PCR showed the enrichment of FOSL1 in the promoter regions of SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA gene (Fig. 5A). Moreover, both FOSL1 knockdown and T-5224 treatment significantly diminished the enrichment of FOSL1 at the promoters of these glycolytic genes (Fig. 5B and C). To identify the binding motifs, we scrutinized the 2000 bp promoter regions these genes for potential FOSL1 binding sites. Additionally, we constructed promoter reporter constructs containing these putative binding sites and conducted luciferase reporter assays (Fig. 5D-F). The FOSL1 binding motif was acquired from JASPAR. The findings demonstrated that FOSL1 overexpression markedly increased the reporter activity of SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA. Notably, mutations introduced into these binding sites substantially abrogated the FOSL1-mediated enhancement of promoter activity (Fig. 5D-F). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that FOSL1 plays a crucial role in the transcriptional regulation of glycolytic genes, thereby enhancing glycolysis in TNBC cells.

Fig. 5.

FOSL1 transcriptionally induces SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA gene expression in TNBC cells. (A) ChIP-qPCR validation of the binding relationship between FOSL1 and the promoter regions of the SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA genes. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using an anti-FOSL1 antibody or IgG, and the promoter binding sites of each gene for FOSL1 were amplified by quantitative PCR with specific primers. Normal rabbit IgG served as a negative control, while input samples underwent reverse transcription PCR as a positive control. (B, C) ChIP-qPCR showing that FOSL1 knockdown (B) or T-5224 treatment (C) reduced the recruitment of FOSL1 on the promoter regions of the SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA genes. (D-F) The predicted FOSL1-binding sites in the SLC2A1 promoter (D), ENO1 promoter (E), and LDHA promoter (F) were mutated to create mutant promoters, and the relative luciferase activity of WT or mutant promoters was determined in MCF-10 A cells transfected with vector control or FOSL1. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001

Targeting FOSL1 increases chemotherapy sensitivity

Tumor glycolysis plays a pivotal role in influencing chemotherapy and immunotherapy sensitivity through various mechanisms, including metabolic adaptation, drug resistance, modulation of the tumor microenvironment, and regulation of the cell cycle [28–30]. Targeting tumor glycolysis cancer can reverse chemoresistance in breast cancer [31]. Given the FOSL1-mediated enhancement of glycolysis, we investigated whether targeting FOSL1 could effectively reverse chemoresistance in TNBC. To achieve this, MDA-MB-231 TNBC cells were subjected to treatment with DOX and cisplatin (DDP). Remarkably, interference with FOSL1 expression or treatment with T-5224 significantly augmented the therapeutic efficacy of both DOX and DDP compared to corresponding control cells (Fig. 6A and B). Further analysis of MDA-MB-231-DR cells revealed elevated FOSL1 protein level relative to their sensitive ones (Fig. 6C). Notably, in clinical samples, FOSL1 expression was significantly higher in progressive disease cases after neoadjuvant chemotherapy when compared to those exhibiting complete or partial remission (Fig. 6D). Moreover, interfering FOSL1 with a specific siRNA or treatment with T-5224 reduced the FOSL1 protein level and markedly enhanced the sensitivity of MDA-MB-231-DR cells to DOX treatment (Fig. 6E and F). To further underscore the clinical relevance of our findings, we assessed the therapeutic efficacy of combining FOSL1 targeting with DOX in TNBC tumors derived from MDA-MB-231-DR cells. The results revealed that DOX had no significant impact on the growth of MDA-MB-231-DR tumors, whereas T-5224 diminished the tumor burden by approximately 20%. Importantly, T-5224 effectively resensitized MDA-MB-231-DR cells to DOX treatment in vivo (Fig. 6G). IHC analysis showed that the proliferation index, as indicated by Ki-67, was markedly reduced following treatment with T-5224, while an inverse finding was observed in cleaved caspase 3 (CCS3), indicating increased apoptosis. Furthermore, this effect can be further enhanced with a combined treatment of DOX and T-5224, suggesting a synergistic effect (Supplementary Fig. 3). Collectively, these findings illuminate the promising therapeutic potential of targeting FOSL1 in TNBC, particularly in the context of overcoming chemoresistance.

Fig. 6.

Targeting FOSL1 increases chemotherapy sensitivity. (A) Cell viability test showing the inhibitory effects of DOX and DPP on sh-Ctrl and sh-FOSL1 MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Cell viability test showing the impact of T-5224 on inhibitory effects of DOX and DPP on MDA-MB-231 cells. (C) Real-time qPCR and Western blotting analysis of FOSL1 mRNA and protein level in MDA-MB-231 DOX-resistant and -sensitive cells. (D) IHC analysis showing the expression levels of FOSL1 between samples classified as stable disease (complete or partial remission) and those categorized as progressive disease. Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) Cell viability test showing the impact of siRNA-mediated FOSL1 knockdown on inhibitory effects of DOX on MDA-MB-231-DR cells. (F) Cell viability test showing the impact of T-5224 on inhibitory effects of DOX on MDA-MB-231-DR cells. (G) Xenograft tumor model showing the impact of DOX and T-5224 on tumor growth, originating from MDA-MB-231-DR cells (n = 5 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001

Discussion

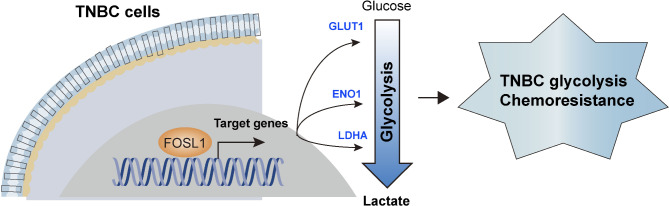

Reprogrammed energy metabolism plays a crucial role in the development of TNBC, particularly through glycolytic processes. We have previously explored how microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs regulate glycolytic metabolism in TNBC. In this study, we expand our understanding of the transcriptional regulation of glycolysis by focusing on the role of FOSL1 in TNBC, enhancing our knowledge of the mechanisms involved in this metabolic reprogramming (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mechanism model. In TNBC, FOSL1 acts as a pivotal transcription factor that orchestrates glycolytic metabolism by transcriptionally activating SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA gene expression. This activation amplifies glycolytic flux, thereby fueling rapid tumor proliferation and fostering chemoresistance in TNBC cells

This study, along with previous investigations [18], has established that FOSL1 is overexpressed in TNBC and basal breast cancer subtypes. FOSL1 is known to play a crucial role in the carcinogenesis of various cancers, influencing multiple aspects of tumor initiation, development, and metastasis [32–35]. Specifically, FOSL1 has been shown to promote processes such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, invasion, metastasis, transendothelial migration of cancer cells, and resistance to treatment in TNBC [36–38]. In our current research, we have identified FOSL1 as a key transcriptional factor driving glycolysis in TNBC. By suppressing FOSL1 using shRNA or the PROTAC probe T-5224, we observed a significant decrease in glycolysis and tumor growth in TNBC cells. Importantly, the ability of FOSL1 to enhance tumor growth appears to rely on increased glycolytic activity, as inhibiting glycolysis with 2-DG diminishes the oncogenic effects of FOSL1. This highlights the importance of glycolysis in the tumor-promoting functions of FOSL1 in TNBC. Specifically, the expression pattern of FOSL1 in TNBC correlate strongly with the elevated glycolytic metabolism observed in TNBC cells, underscoring the critical role of FOSL1 in modulating metabolic pathways essential for tumor growth and progression.

Our research provides further insights into the molecular mechanisms by which FOSL1 regulates glycolysis. Similar to many transcription factors, FOSL1 has the capacity to either activate or repress gene expression, with its impact on specific genes largely determined by its cellular concentration and the identity of its binding partners [17, 39, 40]. During the process of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), FOSL1 is known to suppress the expression of epithelial markers while promoting the expression of endothelial markers and proteolytic enzymes that facilitate the degradation of the extracellular matrix [41, 42]. Additionally, the transcriptional environment surrounding the binding sites of FOSL1 also influences its activity. For example, the activation of the highly conserved IL-6 promoter requires the collaborative action of several transcription factors, including AP-1, cyclic AMP response-element binding protein (CREB), and NF-kappaB [43–45]. To identify the specific downstream targets of FOSL1 in TNBC, we conducted ChIP-PCR and luciferase reporter assays. Through these methods, we confirmed that glycolytic genes such as SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA are direct targets of FOSL1. Consistently, genetic silencing or pharmacological inhibition of FOSL1 significantly diminished its regulatory effects on these glycolytic genes. Besides those genes, ENO2 has been found to be directly regulated by FOSL1 [46]. Therefore, the potential involvement of additional genes that mediate the oncogenic functions of FOSL1 in glycolysis and tumor growth in TNBC merits further investigation.

Several studies have highlighted the association between FOSL1 and chemotherapy resistance, such as ovarian cancer, colon cancer, and breast cancer [35, 47, 48]. In ovarian cancer, genes belonging to the AP-1 transcription factor family, including FOS, FOSB, and FOSL1, have been found to be upregulated in samples displaying resistance to chemotherapy [49]. Consistent with these observations, our investigations reveal that FOSL1 is significantly overexpressed in DOX-resistant TNBC cells and samples that have developed resistance to chemotherapy. Importantly, the role of FOSL1 in mediating drug resistance in TNBC is profound; silencing or inhibiting FOSL1 markedly enhances the sensitivity of DOX-resistant TNBC cells to doxorubicin treatment. The link between glycolysis and chemotherapy resistance is well-established, operating through multiple mechanisms [50]. For example, heightened glycolytic activity boosts the levels of deoxycytidine triphosphate, which can compete with gemcitabine, thereby reducing its efficacy [51]. Additionally, increased glycolysis leads to elevated lactic acid production, acidifying the tumor microenvironment and fostering a pro-cancer and immunosuppressive milieu [52]. While we have elucidated a connection between FOSL1 and TNBC, the specific role of FOSL1 in conferring drug resistance via glycolysis remains an area ripe for further exploration. This underscores the pivotal influence of the FOSL1-driven transcriptional program of glycolysis in shaping the chemoresistant characteristics of TNBC. Due to the limited targeted treatment options available for TNBC, identifying metabolic weaknesses that can serve as therapeutic targets is crucial. The effects of metabolism on TNBC have been extensively studied, and these findings could potentially be leveraged for therapeutic advancements. Research has shown that short-term caloric restriction may increase the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to chemotherapy by enhancing ROS, which is linked to impaired mitochondrial respiration [53]. Additionally, folate deprivation or antifolate treatments may be beneficial for TNBC exhibiting metabolic inflexibility due to heightened mitochondrial dysfunction [54]. Furthermore, a fasting-mimicking diet can activate starvation escape pathways, which may be amenable to drug targeting [55].

In conclusion, our research has identified FOSL1 as a pivotal regulator of glycolysis in TNBC, primarily influencing tumor growth through the transcriptional modulation of critical glycolytic genes, notably SLC2A1, ENO1, and LDHA. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that targeting FOSL1 can effectively reverse chemoresistance in TNBC. Thus, our findings not only illuminate the essential regulatory roles of FOSL1 in glycolysis but also propose a novel and promising therapeutic strategy for the effective treatment of TNBC.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

The project was conceived and supervised by YD. Analysis of the clinical data was performed by YTL and SQY. GZ, YTL, RXC, QZ, and YFF conducted the in vitro and vivo experiments. YTL and RXC are the two pathologists among the authors that assessed the immunostaining. GZ and YTL prepared the original manuscript, incorporating feedback from all authors. All authors participated in drafting and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Youth Foundation of China (Grant No. 82203558), Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology (20220204091YY).

Data availability

All data produced or examined throughout this study are contained within this manuscript and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Jilin University. All patients involved in this study signed informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Derakhshan F, Reis JS. Pathogenesis of Triple-negative breast Cancer. Annual Rev Pathology-Mechanisms Disease. 2022;17:181–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vitaliti A, Roccatani I, Iorio E, et al. AKT-driven epithelial-mesenchymal transition is affected by copper bioavailability in HER2 negative breast cancer cells via a LOXL2-independent mechanism. Cell Oncol. 2023;46:93–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leon-Ferre RA, Goetz MP. Advances in systemic therapies for triple negative breast cancer. Bmj-British Med J 2023;381. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Chen CH, Huang YM, Grillet L, et al. Gallium maltolate shows synergism with cisplatin and activates nucleolar stress and ferroptosis in human breast carcinoma cells. Cell Oncol. 2023;46:1127–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma P. Time to optimize deescalation strategies in Triple-negative breast Cancer? Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:4840–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ren ZQ, Xue YY, Liu L et al. Tissue factor overexpression in triple-negative breast cancer promotes immune evasion by impeding T-cell infiltration and effector function. Cancer Lett 2023;565. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Zhang YS, Wu MJ, Lu WC et al. Metabolic switch regulates lineage plasticity and induces synthetic lethality in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Metabol 2024;36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Jovanovic B, Temko D, Stevens LE et al. Heterogeneity and transcriptional drivers of triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep 2023;42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Li L, Liang Y, Kang L, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the Warburg Effect in Cancer by SIX1. Cancer Cell. 2018;33:368–85. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller DM, Thomas SD, Islam A, et al. c-Myc and cancer metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5546–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elzakra N, Kim Y. HIF-1α metabolic pathways in Human Cancer. Cancer Metabolomics: Methods Appl. 2021;1280:243–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordan JD, Thompson CB, Simon MC. HIF and c-Myc: sibling rivals for control of cancer cell metabolism and proliferation. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:108–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martínez-Ordoñez A, Seoane S, Avila L, et al. POU1F1 transcription factor induces metabolic reprogramming and breast cancer progression via LDHA regulation. Oncogene. 2021;40:2725–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu T, Zheng JY, Zhuo W et al. ETV4 promotes breast cancer cell stemness by activating glycolysis and CXCR4-mediated sonic hedgehog signaling. Cell Death Discovery 2021;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Du Y, Wei N, Ma RL et al. A mir-210-3p regulon that controls the Warburg effect by modulating HIF-1α and p53 activity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Death Dis 2020;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Du Y, Wei N, Ma RL et al. Long noncoding RNA MIR210HG promotes the Warburg Effect and Tumor Growth by enhancing HIF-1α translation in Triple-negative breast Cancer. Front Oncol 2020;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Sobolev VV, Khashukoeva AZ, Evina OE et al. Role of the transcription factor FOSL1 in Organ Development and Tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Casalino L, Talotta F, Matino I et al. FRA-1 as a Regulator of EMT and metastasis in breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Liang Y, Han D, Zhang SJ et al. FOSL1 regulates hyperproliferation and NLRP3-mediated inflammation of psoriatic keratinocytes through the NF-kB signaling via transcriptionally activating TRAF3. Biochim Et Biophys Acta-Molecular Cell Res 2024;1871. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Casalino L, Talotta F, Cimmino A et al. The Fra-1/AP-1 oncoprotein: from the undruggable transcription factor to therapeutic targeting. Cancers 2022;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Serino LTR, Jucoski TS, Morais SB, et al. Association of FOSL1 copy number alteration and triple negative breast tumors. Genet Mol Biology. 2019;42:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim JE, Kim BG, Jang Y, et al. The stromal loss of miR-4516 promotes the FOSL1-dependent proliferation and malignancy of triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Lett. 2020;469:256–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feldker N, Ferrazzi F, Schuhwerk H et al. Genome-wide cooperation of EMT transcription factor ZEB1 with YAP and AP-1 in breast cancer. EMBO J 2020;39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bejjani F, Tolza C, Boulanger M, et al. Fra-1 regulates its target genes via binding to remote enhancers without exerting major control on chromatin architecture in triple negative breast cancers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:2488–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song DD, He H, Sinha I, et al. Blocking Fra-1 sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer to PARP inhibitor. Cancer Lett. 2021;506:23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han B, Guan X, Ma MY, et al. Stiffened tumor microenvironment enhances perineural invasion in breast cancer via integrin signaling. Cell Oncol. 2024;47:867–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaman SU, Pagare PP, Huang BS et al. Novel PROTAC probes targeting FOSL1 degradation to eliminate head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cancer stem cells. Bioorg Chem 2024;151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Chen PC, Ning Y, Li H, et al. Targeting ONECUT3 blocks glycolytic metabolism and potentiates anti-PD-1 therapy in pancreatic cancer. Cell Oncol. 2024;47:81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chelakkot C, Chelakkot VS, Shin Y et al. Modulating glycolysis to Improve Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Ren XJ, Cheng Z, He JM et al. Inhibition of glycolysis-driven immunosuppression with a nano-assembly enhances response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in triple negative breast cancer. Nat Commun 2023;14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Varghese E, Samuel SM, Lísková A et al. Targeting glucose metabolism to Overcome Resistance to anticancer chemotherapy in breast Cancer. Cancers 2020;12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Wang WJ, Yun BK, Hoyle RG et al. Facilitates formation of FOSL1 phase separation and Super enhancers to drive metastasis of Tumor budding cells in Head and Neck squamous cell carcinoma. Adv Sci 2024;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Vallejo A, Erice O, Entrialgo-Cadierno R, et al. FOSL1 promotes cholangiocarcinoma via transcriptional effectors that could be therapeutically targeted. J Hepatol. 2021;75:363–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Z, Wang S, Li H-L, et al. FOSL1 promotes proneural-to-mesenchymal transition of glioblastoma stem cells via UBC9/CYLD/NF-kappaB axis. Mol Therapy: J Am Soc Gene Therapy. 2022;30:2568–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li L, Wang N, Xiong YY, et al. Transcription factor FOSL1 enhances drug resistance of breast Cancer through DUSP7-Mediated dephosphorylation of PEA15. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20:515–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tolza C, Bejjani F, Evanno E, et al. AP-1 signaling by Fra-1 directly regulates HMGA1 Oncogene transcription in Triple-negative breast cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 2019;17:1999–2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoang VT, Matossian MD, La J, et al. Dual inhibition of MEK1/2 and MEK5 suppresses the EMT/migration axis in triple-negative breast cancer through FRA-1 regulation. J Cell Biochem. 2021;122:835–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shu L, Chen A, Li LR, et al. NRG1 regulates Fra-1 transcription and metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer cells via the c-Myc ubiquitination as manipulated by ERK1/2-mediated Fbxw7 phosphorylation. Oncogene. 2022;41:907–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elangovan IM, Vaz M, Tamatam CR, et al. FOSL1 promotes Kras-induced Lung Cancer through Amphiregulin and Cell Survival Gene Regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:625–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayan AE, Stanford R, Vickery R, et al. Fra-1 controls motility of bladder cancer cells via transcriptional upregulation of the receptor tyrosine kinase AXL. Oncogene. 2012;31:1493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakiri L, Macho-Maschler S, Custic I, et al. Fra-1/AP-1 induces EMT in mammary epithelial cells by modulating Zeb1/2 and TGFβ expression. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:336–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao CY, Qiao YC, Jonsson P, et al. Genome-wide profiling of AP-1-Regulated transcription provides insights into the invasiveness of Triple-negative breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74:3983–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khedri A, Guo SC, Ramar V et al. FOSL1’s Oncogene Roles in Glioma/Glioma Stem Cells and Tumorigenesis: A Comprehensive Review. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Persson E, Voznesensky OS, Huang YF, et al. Increased expression of interleukin-6 by vasoactive intestinal peptide is associated with regulation of CREB, AP-1 and C/EBP, but not NF-κB, in mouse calvarial osteoblasts. Bone. 2005;37:513–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zerbini LF, Wang YH, Cho JY, et al. Constitutive activation of nuclear factor κB p50/p65 and Fra-1 and JunD is essential for deregulated interleukin 6 expression in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2206–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yukimoto R, Nishida N, Sekido Y, et al. Specific activation of glycolytic enzyme enolase 2 (ENO2) in BRAF V600E-mutated colorectal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022;113:956–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu GY, Wang H, Ran R et al. FOSL1 transcriptionally regulates PHLDA2 to promote 5-FU resistance in colon cancer cells. Pathol Res Pract 2023;246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Wu JM, Sun YM, Zhang PY et al. The Fra-1-miR-134-SDS22 feedback loop amplifies ERK/JNK signaling and reduces chemosensitivity in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Death Dis 2016;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Javellana M, Eckert MA, Heide J, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy induces genomic and transcriptomic changes in Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. 2022;82:169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Icard P, Shulman S, Farhat D, et al. How the Warburg effect supports aggressiveness and drug resistance of cancer cells? Drug Resist Updates. 2018;38:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shukla SK, Purohit V, Mehla K, et al. MUC1 and HIF-1alpha signaling crosstalk induces anabolic glucose metabolism to Impart Gemcitabine Resistance to Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:71–87. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Apostolova P, Pearce EL. Lactic acid and lactate: revisiting the physiological roles in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Immunol. 2022;43:969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pateras IS, Williams C, Gianniou DD et al. Short term starvation potentiates the efficacy of chemotherapy in triple negative breast cancer via metabolic reprogramming. J Translational Med 2023;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Coleman MF, O’Flanagan CH, Pfeil AJ et al. Metabolic response of Triple-negative breast Cancer to Folate Restriction. Nutrients 2021;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Salvadori G, Zanardi F, Iannelli F, et al. Fasting-mimicking diet blocks triple-negative breast cancer and cancer stem cell escape. Cell Metabol. 2021;33:2247–. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data produced or examined throughout this study are contained within this manuscript and its supplementary information files.