Summary

Background

Biological age (BA), an integrated measure of physiological aging, has a clear link to stroke. There is a paucity of long-term longitudinal studies about the association between accelerated biological age and stroke prognosis in patients with previous strokes, and the differences in the predictive ability of various BA indicators calculated from clinical biochemistry biomarkers for future stroke outcomes are still unknown. To evaluate the role of three accelerated BA indicators for short- and long-term prognosis of patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), and to identify the most appropriate predictor.

Methods

This study included 7396 patients from the Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III), a prospective national registry of patients with acute ischemic stroke or TIA between August 2015 and March 2018 in China. We constructed accelerated BA using three widely recognized algorithms: PhenoAge, Klemera-Doubal, and HD method. To ascertain the association of accelerated BA with the risk of short- and long-term stroke outcomes, a Cox or logistic regression model was conducted for the analysis. The net reclassification index and integrated discrimination improvement were used to evaluate the added model improvement ability of BA acceleration.

Findings

Compared to those with the lowest of PhenoAge acceleration, patients with the highest were more likely to have a higher risk of stroke (HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.49–2.63, P < 0.001), ischemic stroke (HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.41–2.53, P < 0.001), composite vascular events (HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.53–2.68, P < 0.001), all-cause death (HR 7.02, 95% CI 3.41–14.47, P < 0.001) and the modified Rankin scale of 3–6 (OR 2.55, 95% CI 2.05–3.16, P < 0.001) at three months, and the association observed within one year and five years was similar to that within three months. The risk of all stroke outcomes for HDAge was consistent with PhenoAge acceleration, but KDMAge acceleration was the same, except for stroke within one year (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53, P = 0.053). PhenoAge acceleration provided a better improvement in the model’s predictive ability for stroke prognosis, compared to BA determined by other algorithms.

Interpretation

In this prospective cohort study, BA acceleration, particularly PhenoAge, may help identify stroke patients with risks of short- and long-term poor outcomes, potentially enabling subclinical prevention and early intervention.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2019-I2M-5-029), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20358), Beijing Hospitals Authority Clinical Medicine Development of special funding support (ZLRK202312), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC3602500, 2022YFC3602505), Outstanding Young Talents Project of Capital Medical University (A2105), and Beijing High-Level Public Health Technical Personnel Construction Project (Discipline leader -03-12).

Keywords: Biological age, Biological age acceleration, Stroke, Prognosis

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Currently, three clinical biomarker-based algorithms, PhenoAge acceleration, Klemera-Doubal method age acceleration, and Homeostatic-Dysregulation age were developed and shown to be strong predictors of future occurrence of stroke. However, whether accelerated biological age (BA) could elevate the risk of short- and long-term stroke prognosis in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack is unclear and the predictive ability of the three BA algorithms for stroke prognosis has not been assessed in the same study population.

Added value of this study

With three well-validated aging measures, this study showed that BA acceleration based on blood biomarkers and physical measurements was positively associated with the risk of short- and long-term stroke outcomes, and the PhenoAge acceleration provided a better improvement in the model’s predictive ability for prognosis compared to BA determined by other algorithms in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our present study suggests that PhenoAge could be the most useful tool for identifying poor stroke prognosis, independent of chronological age. Given that potential reversibility, BA acceleration assessed by blood biomarkers and physical measurements offers the possibility of slowing aging or identifying high-risk stroke populations for preventative interventions.

Introduction

As the global population ages, we face an immense burden of neurological morbidity linked to aging in the coming decades.1,2 Aging, a complex biological process, is characterized by the gradual deterioration of the physiological integrity of cells, tissues, and organs.3 While chronological age (CA; time since birth) serves as a convenient way to evaluate an individual’s aging condition, the pace of aging within a population of the same CA varies from person to person which leads CA to fail to mirror changes in multiple biological systems timely.4 However, biological age (BA) can better capture differences in individuals’ health conditions compared to CA and could account for the variability in the aging process.5,6 Recently, various measures of BA based on phenotypic, molecular biological, or compound indicators have been developed. Clinical indicators constructed using physical and biochemical markers can often detect physiological changes earlier4 and at a lower cost, such as phenotypic age (PhenoAge),7 Klemera-Double method (KDM),8 and homeostasis disorder (HD).9

Chronological age has long been considered a dominant and immutable risk factor for cerebrovascular disease.10 However, previous studies have revealed that BA can not only predict clinical nervous system disorders independently of CA,10, 11, 12 but is also a better predictor of the onset of nervous system disorders and degenerative diseases compared to CA.4,13 Moreover, BA may better indicate an individual’s ability to recover from an injury such as stroke than CA,14 and it has the potential to be modulated.15 Despite several established associations between BA and neurological disease, there is a paucity of long-term longitudinal studies in patients with previous stroke.10 Additionally, the differences in the predictive ability of various BA indicators calculated from clinical biochemistry biomarkers for future stroke outcomes are still unknown.10

To further confirm the association of biological age on short- and long-term stroke prognosis, we applied three validated BA algorithms based on clinically measured biomarkers to stroke patients to assess the role of BA in stroke outcomes and to identify the most appropriate predictor.

Methods

Study participants

The data were derived from the Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III), a prospective national registry of patients with acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) between August 2015 and March 2018 in China.16,17 The protocol of CNSR-III has been previously published in detail.18 In brief, the study aimed to identify the imaging and biological markers for the prognosis of ischemic cerebrovascular events and identify the patients at high risk in an early phase. This study enrolled patients experiencing an ischemic stroke or TIA within 7 days after symptom onset. All participants were monitored for stroke outcomes at three months, one year, and five years. Patients were enrolled from 201 sites, of which 11,261 patients in 171 sites voluntarily participated in the biomarker subgroup study and collected pre-specified blood samples after admission.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Beijing Tiantan Hospital (IRB approval number: KY2015-001-01) and all participating centers. The written informed consent has been signed by all participants or their representatives before entering the study.

Baseline information

The trained researchers collected baseline data for each participant through direct face-to-face interviews or from related medical records following a standardized protocol. Baseline information included age, sex, weight, height, blood pressure, current smoking status, drinking status, and medical history of hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, ischemic stroke, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, and family medical history. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by the square of height (m2), and the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was assessed on admission. All measurements were conducted in accordance with established operating guidelines.

Clinical biomarker measurement

We obtained fasting blood samples and extracted serum, plasma samples, and white blood cells after admission (median time, 53.6 h [interquartile range, 26.5–95.8 h]) after the onset of ischemic stroke or TIA. The extracted samples were transported from the local hospitals to the clinical biobank in Beijing Tiantan Hospital in two layers of anti-contamination packaging and were monitored by a cold chain all the time. All specimens were stored in −80 °C refrigerators until tests were performed centrally and blindly. Serum biochemical indexes and blood cell indexes were entered into the selection progress of BA construction. Importantly, these markers used to calculate BA are routinely collected during clinical care and health research: blood cell counts (hemoglobin, platelet count, white blood cell count, etc.), and biochemical indexes (lipids, fasting glucose, renal function indexes, liver function, etc.).

Construction of biological age and age acceleration

A series of markers, including physical measurements and blood biomarkers, were considered for calculating BA in the Supplementary file. Following the procedure suggested by previous studies, BA was conducted using three widely recognized algorithms: PhenoAge, Klemera–Doubal, and HD methods.7, 8, 9 The three formulas of calculation are supplied in Supplementary method. The Pearson’s correlation coefficient for each marker was calculated using CA, and those with coefficients above a specific threshold (>0.10) were considered in the construction by sex.19 Observations with missing values were excluded from this analysis, resulting in sixteen markers used for calculations in both men and women. These markers, including waist, albumin, uric acid, lymphocyte, monocyte, red blood cell count, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, cystatin C, diastolic blood pressure, gamma glutamyl transferase, high density lipoprotein, total triglyceride, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, and mean cell volume, were subsequently utilized to calculate PhenoAge, KDMAge, and HDAge. Additionally, we also calculated PhenoAge using nine blood chemical markers (albumin, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, C-reactive protein, glucose, mean cell volume, red blood cell distribution width, white blood cell count, and lymphocyte ratio) for further sensitivity analysis.20

For the three methods of biological age (BA), the blood-chemistry-derived measures were initially derived from NHANES 1988–1994 (NHANES III). Access to the relevant algorithms and R code was available through the ‘BioAge’ R package at https://github.com/dayoonkwon/BioAge.21 PhenoAge was developed by multiple factors linked to mortality risks, utilizing elastic-net Gompertz regression to estimate the risk of death.22 KDMAge was determined by conducting multiple regressions between certain biomarkers and CA in the reference population, allowing for a quantitative evaluation of the decline in system integrity.8 Furthermore, HDAge assessed the deviation of an individual’s physiological measurements from the reference derived from a youthful and healthy population by using the Mahalanobis distance metric.9 In the present study, the acceleration of PhenoAge and KDMAge was calculated by the regression of BA on CA. When assessing biological age acceleration, individuals with PhenoAge or KDMAge exceeding their CA were considered to age more rapidly. Individuals with a higher HDAge were more susceptible to homeostatic disorders and physical health burdens, and were perceived to undergo a more accelerated state of aging. Given that HDAge was skewed, we used natural log-transformed HD in our predictive models for HD age acceleration.23

Outcomes

Participants were followed up by face-to-face interviews at three months and by telephone at one and five years by trained site investigators. Ischemic stroke was characterized by either severe primary neurological impairment (an increase of 4 or more points on the NIHSS score) resulting from cerebral ischemia or new neurological impairment lasting more than 24 h.18 Stroke included both ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke, while composite vascular events included ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, and vascular death. All-cause death was defined as fatalities resulting from any cause. The poor functional outcome was defined as an modified Rankin scale (mRS) of 3–6.24 Events were collected by site researchers and were ultimately decided by the independent endpoint determination committee. Case fatality was either verified on a death certificate from the hospital or local civil registry. Data for patients did not have follow-up assessment were censored on the date of a primary outcome event or the last visit if the patient was lost to follow-up, whichever came first.

Statistical method

BA acceleration was categorized into four groups by quartiles. Continuous variables were reported as mean with standard deviation (SD) or median with the interquartile range, and categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the association between BA acceleration and stroke, stroke recurrence, composite vascular events, and all-cause death. Data for patients did not have follow-up assessment were censored on the date of a primary outcome event or the last visit if the patient was lost to follow-up, whichever came first. We found no violations of the proportional hazard assumption in the models using Schoenfeld residuals (P > 0.05). The outcome of mRS scores of 3–6 was analyzed using logistic regression. We calculated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) or odds ratios (ORs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the first quartile as the reference through three multivariable Cox/logistic methods. The confounding factors relevant to stroke outcome were selected according to findings of previous literature and clinical knowledge.25,26 We used four adjusted models in this study. Model 1 was adjusted for CA and gender, and model 2 additionally adjusted for body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, educational background, and living condition. Model 3 further included covariates that are relevant to stroke outcome based on the literature including previous medical history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, family medical history and NIHSS at baseline. Model 4 adjusted for covariates in model 3 using the inverse-probability-of-treatment-weighted method to account for missing values for biomarkers as a sensitive analysis.27 We further used the Fine–Gray competing risk models, considering all-cause death as a competing event. Additionally, the net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were further used to evaluate the added predictive value of BA acceleration. Restricted cubic splines with 4 knots were constructed to model a non-linear relationship between BA and stroke outcomes.

A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R version 4.3.1 and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Role of the funding source

The funders played no role in study design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or writing of the manuscript for publication.

Results

Baseline characteristics

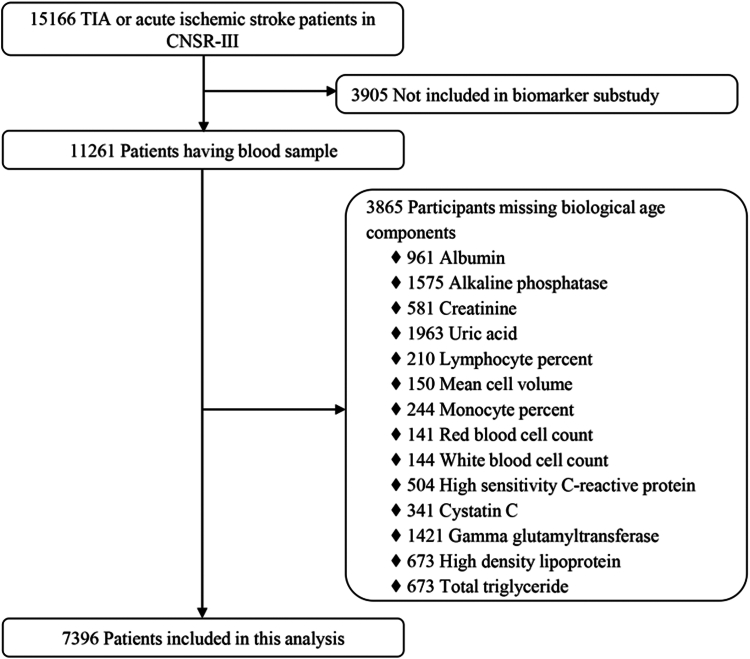

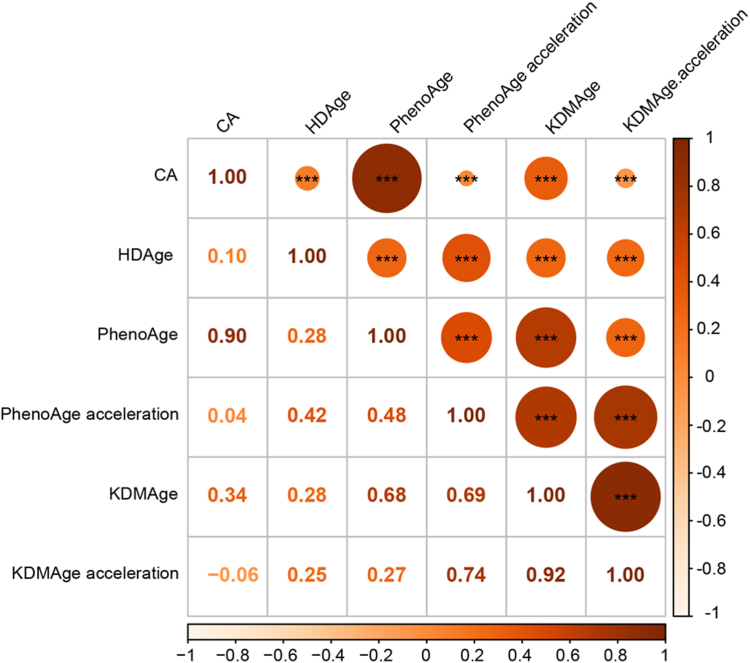

Among all the patients with ischemic stroke or TIA enrolled in the CNSR-III study, 11,261 patients underwent baseline blood sample collection. After excluding 3865 patients with missing data of laboratory tests, a total of 7396 patients were included in this analysis (Fig. 1). Briefly, the average age of these patients was 62.3 (±11.3) years and 31.7% were women. A total of 4724 patients (63.9%) had a history of hypertension, and 1218 (16.5%) with hypercholesterolemia, and 1784 (24.1%) with diabetes (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of included and excluded participants were well-balanced (Supplementary Table S1). Biological and physical indicators used to construct BA are shown in Supplementary Table S2. The PhenoAge measure was highly correlated with CA (Pearson coefficient = 0.90) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for the selection of participants. CNSR-III, the Third China National Stroke Registry; TIA, Transient Ischemic Stroke.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants (n = 7396).

| Characteristic | N (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 62.3 ± 11.3 |

| Female | 2346 (31.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 24.7 ± 3.3 |

| Current smoking, No. (%) | 2371 (32.1) |

| Heavy drinking, No. (%) | 1062 (14.4) |

| Educational background | |

| Middle school and below | 5291 (71.5) |

| High school and above | 2105 (28.5) |

| Living condition | |

| Live alone | 378 (5.1) |

| Live with others | 7018 (94.9) |

| NIHSS | 3.0 (1.0–6.0) |

| 0–3 | 3952 (53.4) |

| ≥3 | 3444 (46.6) |

| Medical history, No. (%) | |

| Stroke | 1690 (22.8) |

| Hypertension | 4724 (63.9) |

| Diabetes | 1784 (24.1) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1218 (16.5) |

| Coronary artery disease | 778 (10.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 289 (3.9) |

| Family medical history | |

| Hypertension | 1540 (20.8) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 152 (2.1) |

| Diabetes | 471 (6.4) |

| Stroke | 908 (12.3) |

| Coronary artery disease | 333 (4.5) |

| Index event, No. (%) | |

| Ischemic stroke | 6618 (89.5) |

| TIA | 778 (10.5) |

| Biological aging | |

| HDAge (log units) | 5.1 ± 1.0 |

| PhenoAge (years) | 61.2 ± 12.8 |

| PhenoAge acceleration | −1.2 ± 5.7 |

| KDMAge (years) | 55.7 ± 28.3 |

| KDMAge acceleration | −6.7 ± 26.7 |

BMI, body mass index; TIA, Transient ischemic stroke; HDAge, homeostatic dysregulation age; KDMAge, Klemera-Doubal method age.

Fig. 2.

Correlation matrix of chronological age, biological ages, and age accelerations (Pearson correlation). ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

Biological age and stroke outcomes

There were 1.2%, 2.6%, and 11.0% of patients lost to follow-up at three months, one year and five years, respectively. During the 3-month follow-up, patients had 451 (6.1%) strokes, 420 (5.7%) ischemic strokes, 468 (6.3%) composite vascular events, 107 (1.4%) all-cause deaths, and 1000 (13.7%) mRS of 3–6. After adjusting for all potential confounders, per 1-SD increase in PhenoAge acceleration showed positive associations with stroke (HR 1.22; 95%CI 1.12–1.32; P < 0.001), ischemic stroke (HR 1.21; 95%CI 1.11–1.32; P < 0.001), composite vascular events (HR 1.24; 95%CI 1.15–1.34; P < 0.001), all-cause mortality (HR 1.78; 95%CI 1.59–1.99; P < 0.001), and mRS of 3–6 (OR 1.37; 95%CI 1.28–1.46; P < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S3). Compared with the first quartile of PhenoAge acceleration, participants in the fourth quartile were more likely to have a higher risk of stroke (HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.49–2.63, P < 0.001), ischemic stroke (HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.41–2.53, P < 0.001), composite vascular events (HR 2.03, 95% CI 1.53–2.68, P < 0.001), all-cause death (HR 7.02, 95% CI 3.41–14.47, P < 0.001), and mRS of 3–6 (OR 2.55 95% CI 2.05–3.16, P < 0.001). The risk of all stroke outcomes for HDAge and KDMAge acceleration was consistent with PhenoAge acceleration.

For long-term follow-up, the association between age acceleration calculated by the three different algorithms and stroke outcomes at one year and five years was consistent with that at three months (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). Over the 5-year follow-up, patients had 1172 (15.9%) strokes, 1061 (14.4%) ischemic strokes, 1356 (18.3%) composite vascular events, 759 (10.3%) all-cause deaths, and 1318 (20.0%) cases had an mRS of 3–6. A per 1-SD increase in PhenoAge acceleration also showed positive associations with stroke (HR 1.13; 95%CI 1.07–1.19; P < 0.001), ischemic stroke (HR 1.11; 95%CI 1.04–1.17; P < 0.001), composite vascular events (HR 1.13; 95%CI 1.07–1.19; P < 0.001), all-cause mortality (HR 1.49; 95%CI 1.41–1.57; P < 0.001), and mRS of 3–6 (OR 1.52; 95%CI 1.42–1.62; P < 0.001) in model 3. The risk of stroke outcomes within one year and five years for HDAge was consistent with PhenoAge acceleration, but KDMAge acceleration was the same, except for stroke within one year (HR 1.24, 95% CI 1.00–1.53, P = 0.053). PhenoAge acceleration calculated based on nine markers remained identical to the other age acceleration algorithms (Supplementary Table S6). Additionally, the effect size for the risk of death was slightly larger compared to other stroke outcomes.

In sensitive analysis, the results of the inverse weighted probability model and competition risk model were largely similar to those of other models (Supplementary Tables S3–S7). To evaluate the effects of biological aging on different stroke subtypes, we analyzed the association between biological aging and stroke risk in both cardiogenic and non-cardiogenic patients, observing generally consistent outcomes in Supplementary Table S8. When we excluded the patients with medical history of stroke, the all results still were similar to those of all patients (Supplementary Table S9).

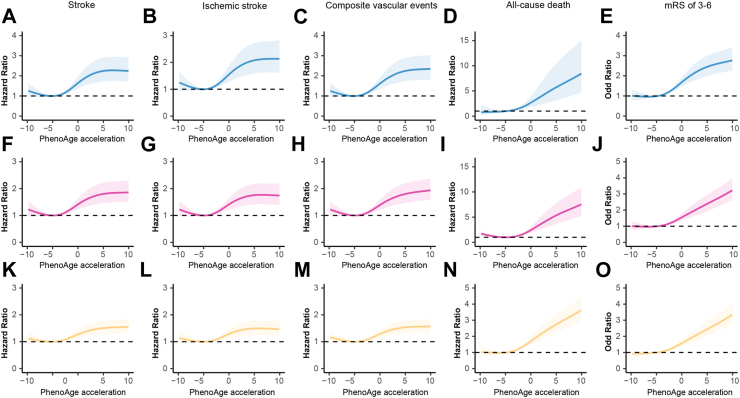

Multivariable-adjusted spline regression models further showed a positive relationship between biological age acceleration and short- and long-term stroke prognosis (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). The trajectory of cumulative probability for different outcomes at three months, one year, and five years using Kaplan–Meier analysis by stratifying the biological ages (Supplementary Figs. S4–S6).

Fig. 3.

Graphs of the best fitting models for relationships of PhenoAge acceleration with stroke, ischemic stroke, composite vascular events, all-cause death, and mRS of 3–6 at three months, one year, and five years. Panels: three months (A–E), one year (F–J) and five years (K–O). Restricted cubic spline regression model (4 knots) adjusted for CA, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, educational background, living condition, previous medical history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, family medical history and NIHSS at baseline.

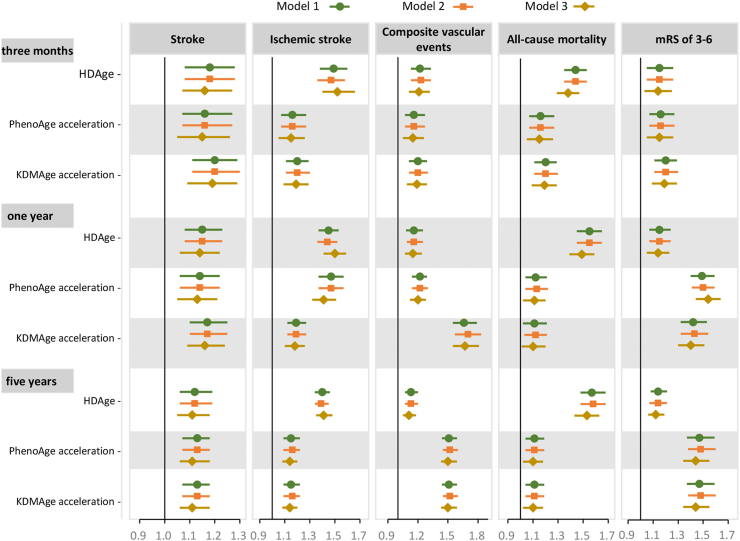

Most of the individual biomarkers included in the BA measures were predictive for neurological outcomes (Supplementary Figs. S7–S9). For example, higher C-reactive protein levels were associated with an increased risk of stroke outcomes, whereas a lower albumin level was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and mRS of 3–6 at three months. Similar results were observed for the one-year and five-year stroke outcomes. Meanwhile, BA acceleration measures showed a comprehensive predictive effect across different stroke outcomes (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

HRs or ORs and 95% CIs for stroke outcomes in relation to 1-SD increase in biological age acceleration measures. Model 1 was adjusted for CA and sex, and model 2 was additionally adjusted for body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, educational background, and living condition. Model 3 further included covariates that are relevant for stroke outcome based on the literature including previous medical history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, coronary heart disease, atrial fibrillation, family medical history and NIHSS at baseline. HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HDAge, homeostatic dysregulation age; KDM, Klemera-Doubal method age; SD, standard deviation.

Improvement in prediction model for stroke outcomes by addition of BA acceleration

In Supplementary Table S10, we compared the performance of different age acceleration models in predicting stroke outcomes. At 3-month follow-up, compared to models with KDMAge acceleration plus basic model, the point estimates of IDIs in PhenoAge acceleration models ranged from 0.20% to 1.32%, and point estimates of NRIs varied from 22.55% to 49.63% for all outcomes. Meanwhile, when HDAge was added to the basic model, the new model showed a better improvement ability for stroke and composite vascular events, with point estimates of IDIs at 0.13% and 0.16% respectively, and point estimates of NRIs at 9.62% and 10.01% respectively. Additionally, PhenoAge acceleration still had a better integrated discrimination improvement ability than HDAge and KDMAge acceleration at one year and five years. Also, for short- and long-term stroke prognosis, we found the three BA accelerations had a better improvement ability than CA when adding to basic models (Supplementary Table S11).

Discussion

In this Chinese stroke registry cohort study, we present novel evidence that BA acceleration based on blood biomarkers and physical measurements was positively associated with the risk of short- and long-term stroke outcomes, with slightly larger effect sizes observed for all-cause death than other stroke outcomes. Further analysis demonstrated that the PhenoAge acceleration provided a better improvement in the model’s predictive ability for prognosis compared to BA determined by other algorithms in patients with TIA or ischemic stroke, and may be a better predictor of short-term and long-term prognosis of stroke.

BA is closely related to the onset and progression of neurological diseases. Previous studies indicated that BA based on clinical biomarkers,4 leukocyte telomere length,28 and DNA methylation measurements,29 could serve as novel indicators for the onset of stroke. Spanish experts have shown for the first time that age acceleration determined by DNA methylation could increase the risk of stroke recurrence.30 However, a case–control study in China revealed that biological aging represented by telomere length in stroke patients was not linked to stroke recurrence, but with a 69% increased risk of post-stroke death in patients with atherosclerotic thrombotic stroke.31 Since DNA methylation and telomere length have less convenience,32 our study based on more readily available physical and clinical indicators, also supported the conclusion that accelerated BA was associated with stroke recurrence, similar to DNA-methylation findings.30 The forementioned study on telomere length31 included patients with atherothrombotic strokes, lacunar infarction, or hemorrhagic strokes, while the methylation study30 and our study mainly involved patients with acute ischemic stroke, thus the results may have been different. Additionally, due to the lack of data validation of long-term prognosis in previous studies,10 we further verified a strong connection between accelerated BA and the long-term prognosis in stroke patients (one year and five years). Consequently, BA acceleration could serve as a potential indicator for predicting long-term stroke outcomes in patients with stroke or TIA, and these findings need to be validated further across different populations. Knowing the BA in stroke patients would be useful to identify those patients at higher risk of recurrent stroke or neurological deterioration in daily clinical practice.29,33 Given the potentially reversible nature of biomarkers used to measure BA,34,35 BA may represent a partially modifiable risk factor compared to CA. Ultimately, the potentially changeable features and corresponding estimation methods of BAs presented in this study can be easily applied in clinical practice or geriatric health management, which could give a window for potential interventions at slowing biological aging to delay the onset of age-related disorders10 and provide novel opportunities for prevention and intervention of cerebrovascular diseases. Currently, the translational use of biological aging measures in clinical practice still needs for more studies. Previous studies have emphasized the potential of multi-domain lifestyle interventions in decelerating aging and preventing chronic disease such as stroke.36,37 We need to further understand the biological mechanisms and to determine whether interventions targeting biological age can improve prognosis in stroke patients. Future studies could focus more on the potential role of lifestyle or other interventions, which may facilitate the tailoring of interventions to specific aspects of aging and/or health.

Currently, there is no gold standard approach to calculating BA based on clinical biomarkers, and discrepancies may exist among different measures.12 As we incorporated the same set of biomarkers into our three BA measures, PhenoAge showed greater improvement in predictive models for stroke outcomes compared to HDAge and KDMAge. The inconsistent result is probably explained by the fact that PhenoAge captures not only CA, but also the mortality risk predicted by the biomarkers. Whereas, HDAge reflects physiological deviations from a youthful and healthy population, and KDMAge simply reflects CA.9 Considering that stroke is a cerebrovascular disease with a characteristic of high mortality rate,38 the PhenoAge algorithm may be more suitable for estimating the BA of the stroke population.

There is currently no clear agreement on the specific role of aging biomarkers in explaining the fundamental mechanisms of aging and stroke outcomes. We speculate on possible mechanisms as follows. First, BA accelerations were computed based on blood biomarkers, and they are strongly associated with stroke and heart disease.29 Ischemic stroke, a manifestation of systemic cardiovascular disease, is influenced by cardiometabolic risk factors.10 Therefore, the association of BA acceleration with stroke outcomes may be due to the selection of biomarkers (e.g., waist circumference, blood pressure, glucose, and lipids) related to cardiovascular health in BA measures,12 and a consequence of the accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors.39 Second, aging can cause cellular damage to the components of neurovascular units and lead to structural and functional impairments.40,41 Patients with previous stroke and age acceleration may experience increased the vulnerability of neurovascular units, which limits their neuroplasticity and recovery capacity,14 and is more likely to lead to stroke recurrence and adverse outcomes. Third, BA acceleration is associated with the enhanced activation of pro-inflammatory pathways. Meanwhile, inflammation and impaired immune function contribute to the pathogenesis of multiple diseases such as stroke, which ultimately leads to mortality.37

Some limitations should be considered. First, missing data on certain clinical biomarkers means that the final included patients do not fully represent the total population, despite mostly balanced baseline characteristic. Second, the evaluation through a phone call in one and five years may lead to bias. Third, since blood sample data are collected after onset, certain physical and blood markers could be influenced by the stress response in acute ischemic stroke patients rather than reflecting steady-state data. Fourth, the composition of BA is limited to available clinical markers and some markers relevant to aging were not collected and included in this study, such as pulmonary functional parameters measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 s.4 Fifth, changes in biomarkers used for BA may also affect stroke prognosis during follow-up, but the relevant data were not collected. Sixth, biological aging depends not only on modifiable risk factors such as lifestyles and the use of medicines, but also on psychosocial and economic determinants as well as genetic determinants of individual host responses. However, our study cannot completely capture all potential risk factors. Seventh, the models cannot adjust for the medical interventions that these patients had received during the follow up, which would definitely impact the outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, this investigation used prospective data to explore the associations of various BA accelerations with the prognosis of patients with stroke or TIA. BA acceleration such as PhenoAge, KDMAge, and HDAge, may serve as an effective biomarker for predicting short- and long-term outcomes of ischemic stroke, especially PhenoAge. BA assessed by blood biomarkers and physical measurements offers the possibility of slowing aging or identifying high-risk populations for preventative interventions.

Contributors

MXW, YSP, and YJW conceptualized and designed the study. MXW, YLZ, XM, QZ, JXL, YJ collected the data. MXW drafted the manuscript. HYY analyzed and interpreted the data. YSP and YJW interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. All authors commented upon and approved the final manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data used for this analysis can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors.

Declaration of interests

All authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participating hospitals for their valuable contributions. This work was supported by grants from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2019-I2M-5-029), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20358), Beijing Hospitals Authority Clinical Medicine Development of special funding support (ZLRK202312), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC3602500, 2022YFC3602505), Outstanding Young Talents Project of Capital Medical University (A2105), and Beijing High-Level Public Health Technical Personnel Construction Project (Discipline leader -03-12).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105494.

Contributor Information

Yuesong Pan, Email: yuesongpan@aliyun.com.

Yongjun Wang, Email: yongjunwang@ncrcnd.org.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.Erlangsen A., Stenager E., Conwell Y., et al. Association between neurological disorders and death by suicide in Denmark. JAMA. 2020;323(5):444–454. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eren F., Yilmaz S.E. Neuroprotective approach in acute ischemic stroke. Brain Circ. 2022;8(4):172–179. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_52_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S.S., Singer B.D., Vaughan D.E. Molecular and physiological manifestations and measurement of aging in humans. Aging Cell. 2017;16(4):624–633. doi: 10.1111/acel.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L., Zhang Y., Yu C., et al. Modeling biological age using blood biomarkers and physical measurements in Chinese adults. EBioMedicine. 2023;89 doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pellegrini M., Hägg S., Belsky D.W., Cohen A.A. Developments in molecular epidemiology of aging. Emerg Top Life Sci. 2019;3(4):411–421. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20180173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li X., Ploner A., Wang Y., et al. Longitudinal trajectories, correlations and mortality associations of nine biological ages across 20-years follow-up. Elife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.51507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basu S., Liu Z., Kuo P.-L., et al. A new aging measure captures morbidity and mortality risk across diverse subpopulations from NHANES IV: a cohort study. PLoS Med. 2018;15(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klemera P., Doubal S. A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen A.A., Milot E., Yong J., et al. A novel statistical approach shows evidence for multi-system physiological dysregulation during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2013;134(3–4):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurran C.E., Wang Y., Mak J.K.L., et al. Advanced biological ageing predicts future risk for neurological diagnoses and clinical examination findings. Brain. 2023;146(12):4891–4902. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao X., Ma C., Zheng Z., et al. Contribution of life course circumstances to the acceleration of phenotypic and functional aging: a retrospective study. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;51 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mak J.K.L., McMurran C.E., Hägg S. Clinical biomarker-based biological ageing and future risk of neurological disorders in the UK Biobank. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2024;95(5):481–484. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2023-331917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López-Otín C., Blasco M.A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriano-Tárraga C.M.-C.M., Giralt-Steinhauer E., Ois A., et al. Biological age is better than chronological as predictor of 3-month outcome in ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2017;89(8):830–836. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin B., Mu Y., Ding Z. Assessing the causal association between biological aging biomarkers and the development of cerebral small vessel disease: a mendelian randomization study. Biology. 2023;12(5):660. doi: 10.3390/biology12050660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Z., Xiong Y., Feng X., et al. Insulin resistance estimated by estimated glucose disposal rate predicts outcomes in acute ischemic stroke patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12933-023-01925-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J., Lin J., Pan Y., et al. Interleukin-6 and YKL-40 predicted recurrent stroke after ischemic stroke or TIA: analysis of 6 inflammation biomarkers in a prospective cohort study. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):131. doi: 10.1186/s12974-022-02467-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y., Jing J., Meng X., et al. The Third China National Stroke Registry (CNSR-III) for patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack: design, rationale and baseline patient characteristics. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2019;4(3):158–164. doi: 10.1136/svn-2019-000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X., Huang N., Guo X., Huang T. Role of sleep quality in the acceleration of biological aging and its potential for preventive interaction on air pollution insults: findings from the UK Biobank cohort. Aging Cell. 2022;21(5) doi: 10.1111/acel.13610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine M.E.L.A., Quach A., Chen B.H., et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging. 2018;10(4):573–591. doi: 10.18632/aging.101414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon D., Belsky D.W. A toolkit for quantification of biological age from blood chemistry and organ function test data: BioAge. GeroScience. 2021;43(6):2795–2808. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00480-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levine M.E. Modeling the rate of senescence: can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2012;68(6):667–674. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaney C., Wiley K.S. The variable associations between PFASs and biological aging by sex and reproductive stage in NHANES 1999–2018. Environ Res. 2023;227 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iizuka T., Kaneko J., Tominaga N., et al. Association of progressive cerebellar atrophy with long-term outcome in patients with anti-N-Methyl-d-Aspartate receptor encephalitis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(6):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uzuner N., Uzuner G.T. Risk factors for multiple recurrent ischemic strokes. Brain Circ. 2023;9(1):21–24. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_73_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleindorfer D.O., Towfighi A., Chaturvedi S., et al. 2021 Guideline for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2021;52(7):e364–e467. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansournia M.A., Altman D.G. Inverse probability weighting. BMJ. 2016;352 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H., Lai X., Fang Q., et al. Independent and joint association of leukocyte telomere length and lifestyle score with incident stroke. Stroke. 2023;54(5):e199–e200. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.122.041126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waziry R., Gu Y., Boehme A.K., Williams O.A. Measures of aging biology in saliva and blood as novel biomarkers for stroke and heart disease in older adults. Neurology. 2023;101(23):e2355–e2363. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000207909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soriano-Tárraga C., Lazcano U., Jiménez-Conde J., et al. Biological age is a novel biomarker to predict stroke recurrence. J Neurol. 2020;268(1):285–292. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W., Chen Y., Wang Y., et al. Short telomere length in blood leucocytes contributes to the presence of atherothrombotic stroke and haemorrhagic stroke and risk of post-stroke death. Clin Sci. 2013;125(1):27–36. doi: 10.1042/CS20120691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shireby G.L., Davies J.P., Francis P.T., et al. Recalibrating the epigenetic clock: implications for assessing biological age in the human cortex. Brain. 2020;143(12):3763–3775. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang T., Xiao Y., Cheng Y., et al. Epigenetic clocks in neurodegenerative diseases: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2023;94(12):1064–1070. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2022-330931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li A., Koch Z., Ideker T. Epigenetic aging: biological age prediction and informing a mechanistic theory of aging. J Intern Med. 2022;292(5):733–744. doi: 10.1111/joim.13533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srour B., Hynes L.C., Johnson T., Kühn T., Katzke V.A., Kaaks R. Serum markers of biological ageing provide long-term prediction of life expectancy—a longitudinal analysis in middle-aged and older German adults. Age Ageing. 2022;51(2) doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fayyaz A.I., Ding Y. Mental stress, meditation, and yoga in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Brain Circ. 2023;9(1):1–2. doi: 10.4103/bc.bc_66_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X., Cao X., Zhang J., et al. 2022. Accelerated aging mediates the associations of unhealthy lifestyles with cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality: two large prospective cohort studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsao C.W., Aday A.W., Almarzooq Z.I., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–e639. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ischemic stroke patients are biologically older than their chronological age. Aging. 2016;8:11. doi: 10.18632/aging.101028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell R.D., Winkler E.A., Sagare A.P., et al. Pericytes control Key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron. 2010;68(3):409–427. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai W., Zhang K., Li P., et al. Dysfunction of the neurovascular unit in ischemic stroke and neurodegenerative diseases: an aging effect. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;34:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.