Abstract

Background

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment is the gold standard of clinical care for older patients but its application in the primary care setting is limited, possibly due to its time-consuming process. Hence, a brief geriatric assessment could be a feasible alternative. We conducted a scoping review to identify which brief geriatric assessment tools have been evaluated or implemented in primary and community care settings and to identify the domains assessed including their reported outcomes.

Methods

CENTRAL, PubMed and Embase were searched using specific text words and MeSH for articles published from inception that studied evaluation or implementation of brief geriatric assessments in primary care or community setting.

Results

Twenty-five articles were included in the review, of which 11 described brief geriatric assessments implemented in community, nine in primary care and five in mixed settings. Physical health, functional, mobility/balance and psychological/mental emerged as four domains that are most assessed in brief geriatric assessments. Self-reported questionnaire is the key approach, but uncertainty remains on the validity of subjective cognitive assessments. Brief geriatric assessments have been administered by non-healthcare professionals. The duration taken to complete ranged from five to 20 min. Studies did not report significant change in the clinical outcomes of older adults except for better identification of those with higher needs.

Conclusion

The studies reported that brief geriatric assessments could identify older adults with unmet needs or geriatric syndromes, but they did not report improved health outcomes when combined with clinical intervention pathways. Clarity of brief geriatric assessments’ questions is important to ensure the feasibility of using self-administered questionnaire by older adults. Future studies should determine which groups of older adults benefit the most from the brief assessments when these are paired with additional evaluations and interventions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12877-024-05615-9.

Keywords: Brief geriatric assessment, Primary care, Community setting

Introduction

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is defined as a multi-dimensional and multi-disciplinary approach to identify medical, functional, and social needs, followed by the development of a coordinated and targeted care plan to address the identified needs of older patients [1]. Given its recognition as the gold standard of clinical care for frail older patients in the hospital setting [1] and beneficial effect yielded in mortality reduction [2], extension of CGA to primary care could be considered given that this setting often provides the first point of clinical contact for this population [3]. However, the application of CGA in the primary care setting is limited [3], possibly due to its time-consuming process [3, 4]. Typically, a CGA may take up to two hours [5].

CGA is usually conducted by the multidisciplinary team and medical professionals in acute hospital and primary care settings respectively [6]. Impacted by the mismatch of supply of healthcare professionals and the increasing needs of an ageing population, briefer or simplified geriatric assessment which can either be self-administered by older adults or administered by trained non-healthcare professionals have increasing appeal.

Hence, brief geriatric assessment (BGA) has emerged as a possible alternative for CGA in primary care and community settings, including in the homes of those with limited access to primary care services. Unlike CGA, the role of BGA is unclear in clinical pathways. Despite the shorter duration of BGA, ranging from 15 [6] to 30 min [7], implementing BGA widely remains challenging given the rapid growth of older populations globally.

To date, there is a lack of consensus on which community-dwelling adults should be targeted to receive geriatric assessment, due in part to its varied purposes which range from health promotion to early detection of impairments or diseases [6]. It is suggested that neither robust older adults [8] nor those in poor health or with disability [9] benefit from geriatric assessment. Thus, older adults in the middle of the health spectrum are more likely benefit from BGA and they may have two or more chronic conditions or polypharmacy [8]. Finding a BGA that could easily be applied in a community setting to identify older adults in this middle spectrum could be crucial for early intervention.

Despite the emergence of BGA in geriatric care, there is also no consensus on which domains should be assessed. BGA was often developed based on prior literature [10, 11], CGA [11] and from the pool of assessment tools for different domains [12, 13]. The latter possibly arose due to the need to cater to different contexts, available resources and different targeted populations. As a result, the envisaged role of BGA as a shortened version of CGA is debatable, given that the former largely emphasises screening to allow early detection of impairments while the latter serves to direct care processes. Moreover, the application of the four focus areas of CGA, medical, psychological, social, and functional [1, 14] in BGA remains to be studied.

Heterogeneity of BGA tools, ranging from their components (assessed domains) to implementation (self-administered versus interviewer-administered) makes selection of the most appropriate BGA tool for specific contexts and subgroups of older adults an uphill task for practitioners. Given these knowledge gaps, our scoping review sought to identify tools and methodologies employed in BGA for older adults and the practical considerations and levels of implementation in primary care and community settings.

Methods

This review was conducted with reference to the COCHRANE Scoping Review Method guidance document [15]. The review questions were formulated based on prior discussions with health policy makers that positioned geriatric assessment as a key population health initiative to improve the quality of life of older adults. This study conforms to the PRISMA guidelines and reports their required information accordingly (see Additional file 1).

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted with three electronic databases – Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed and Embase. The search strategy was developed using the PCC framework (population, concept, context), adopting a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and text words related to older adults, geriatric assessment, abbreviated, brief, rapid and short. Articles published from inception till 18 April 2024 were considered for inclusion. Additional file 2 provides the search strategy used for PubMed.

The study inclusion criteria were 1) study participants 60 years old and above; 2) evaluation and/or application of BGA in the primary care or community settings; and 3) BGA that minimally assesses physical and mental domains. The exclusion criteria were 1) studies targeting population with specific conditions (e.g., dementia, mild cognitive impairment, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, pre-surgical); 2) studies conducted solely in acute hospitals, long term care facilities, post-discharge from hospitals or specialist outpatient clinical settings; and 3) conference proceedings, commentary, or studies without full texts in the English language.

Study selection and data extraction

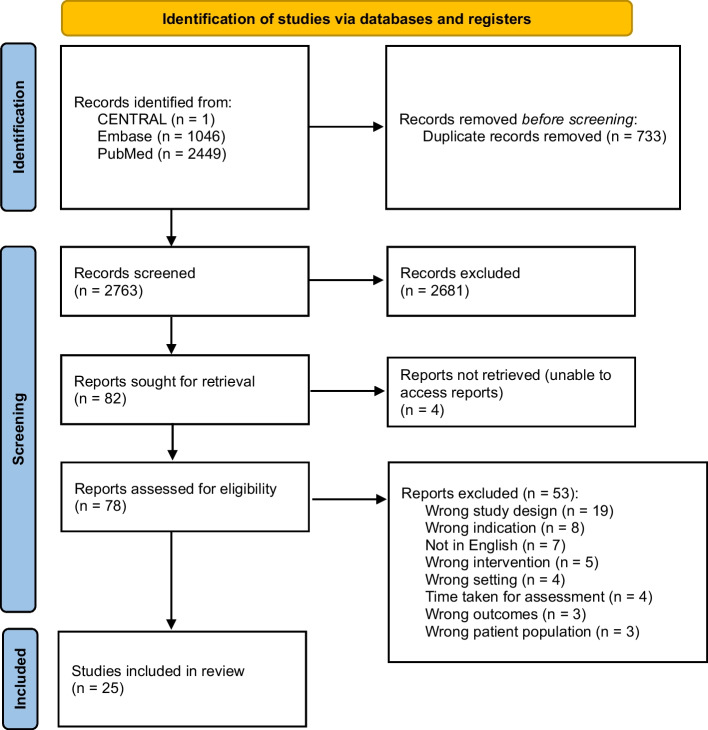

Three reviewers (JG, LKL and PL) performed the screening of citations using Covidence, a web-based tool [16]. The title and abstract of each citation were independently screened by two reviewers and the same process was repeated for articles at the full-text screening stage. Any disagreement during screening (either title/abstract or full text) was resolved by the third reviewer. The PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1 presents the flow of study selection. A data extraction sheet was developed and pilot-tested prior to the data extraction phase. Data extraction was performed on all included articles by either JG, LKL or PL using a data extraction sheet to capture details of the study population, overall study aims, study population, BGA tool, domains assessed by BGA and summarised findings. The extracted information was cross-checked by a second reviewer for accuracy. Risk of bias assessment was not conducted given our review objectives.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Results

Study characteristics

Twenty-five studies were included in this review (Table 1). Among them, 11 studies involved the implementation of BGA in the community [11, 17–26], nine in the primary care setting [10, 27–34] and five in mixed settings of community and primary care [35–37], community, primary care, hospital and/or long-term care facilities [38, 39]. The last two referenced studies were included given that their BGA implementations were in community and primary care settings for majority (about 80%) of the total study populations.

Table 1.

Studies that included BGA as part of the evaluation and/or implementation in primary care and community setting

| Authors, year | Overall aim | Study design | Study population | Setting | BGA tool | Reliability | Validity | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessi et al., 2003 [17] | To assess the reliability & validity of a postal survey | Longitudinal cohort study |

n = 2575 [73.5(5.7) yo]; 3.0% ♀ Older adults, aged ≥ 65yo who have multiple geriatric problems |

Community | GPSS |

Yes Percentage agreement test–retest – 88.3% Weighted kappa 0.70 |

Yes Against established questionnaire for each domain |

Sensitivity and specificity for all domains except memory & ADL ranged from 0.71 to 0.81 and 0.69 to 0.82 respectively GPSS cutoff points ≥ 4 (high risk) has sensitivity & specificity of 89% & 42% respectively |

| Balsinha et al., 2018 [27] | To examine the usefulness & feasibility of SPICE in the primary care setting | Cross-sectional |

n = 51 [74.9(7.3) yo]; 60.8% ♀ Patients, aged 65yo visited GP |

Primary care | SPICE | No | No | The agreement between patents’ perception & doctor’s perception (based on medical record) using SPICE were fair (k = 0.56 to 0.71) |

|

Chen et al., 2020 [18] |

To develop simplified & brief screening tool | Development & validation study |

n = 200 [77.5(7.5) yo]; 62.0% ♀ Patients, > 65yo in the community |

Community | HCOASS |

Yes The internal consistency was acceptable (α = 0.73) |

Yes The cut off of 6/7 score yielded 88% sensitivity, 81% specificity, 72% PPV & 93% NPV AUC for the HCOASS was 0.91 |

The screening scale demonstrated adequate reliability, content validity & discriminant validity |

|

de Souza Orlandi et al., 2018 [28] |

To validate the translated RGA | Cross-sectional |

n = 148 [70.0(6.8) yo]; 68.2% ♀ Patients, aged 60yo receiving primary care services |

Primary Care |

RGA Incontinence |

Yes Internal consistency ranged from 0.736 to 0.801 ICC ranged from 0.716 to 0.796 |

Yes Satisfactory concurrent validity, discriminant, convergent & divergent validity |

Brazilian version of RGA is a reliable & valid tool to assess older adults |

| Donald 1997 [19] | To develop & validate the EARRS for community-dwelling older adults | Development & validation study |

n = 112 [NS]; NS ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (> 75yo) receiving day care service |

Community Day Care hospital |

EARRS |

Yes Test–retest reliability (Weighted kappa 0.75 to 1.0) Inter-tester reliability (Weighted kappa 0.66 to 0.96) |

Yes The correlation between EARRS & Barthel Index was poor (−0.50 to −0.65) |

EARRS has a good face validity & was a user-friendly scale |

| Fletcher et al., 2004 [29] |

To examine the effects of different clinical pathways (universal vs targeted referral) in the primary care services, following BGA screening |

Longitudinal cohort study |

n = 43,219 [81.4(4.9) yo]; 63.9% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) receiving primary care service |

Primary Care | NS | No | No | Patients who received universal referral for further assessment had lower hospital readmission compared to patients receiving targeted referral |

|

Gaugler et al., 2011 [20] |

To develop a screening tool and deliver a multi-component “diversion” service program to support private-pay older adults | Development and implementation of assessment tool |

n = 261 [NS]; 66.3% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults who are private-pay & at risk for nursing home admission or assisted living entry |

Community | LWAH-RS | No | No | A threshold of 3 on the summed score of the LWAH-RS was considered “high risk” & most older adults were classified as “high risk”. Screening was followed by consultation |

|

Kerse et al., 2008 [35] |

To examine the utility of the BRIGHT questionnaire in identifying community-dwelling older people with disability-related needs | Validation study |

n = 121 [80.9(4.9) yo]; 54.5% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75 years old) receiving or had previously received primary care service |

Community Primary Care | BRIGHT |

Yes Test–retest reliability Cronbach alpha of 0.77 |

Yes BRIGHT cut-off ≥ 3 with IADL yielded 86% sensitivity & specificity BRIGHT cut-off ≥ 3 with adverse outcomes yielded 65% sensitivity & 84% specificity |

BRIGHT has reasonable utility in identifying those with disability but the findings could not be generalised to those with significant level of disability |

|

Kerse et al., 2014 [21] |

To assess the impact of using screening to improve case finding on hospitalizations, residential care placement, functional decline, & quality of life for community-dwelling older adults | Cluster RCT |

n = 3753 [80.3(4.6) yo]; 54.7% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) receiving or had previously received primary care service |

Community | BRIGHT | No | No | The intervention group which received BRIGHT screening had higher number of residential care placement & decreased functional performance compared to the control group |

|

King et al., 2017 [22] |

To describe the innovative model of care, incorporating screening to identify high-needs older people | Single arm pilot study |

n = 416 [79.5(2.4) yo]; 48.1% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) receiving or had previously received primary care service |

Community | BRIGHT | No | No | The BRIGHT screen proved to be an efficient & systematic method for population case finding of high-needs older people through GP practices |

|

Lach et al., 2023 [38] |

To examine the utility of RGA as a fall risk screening tool at various settings | Cross-sectional study |

n = 8686 [77.6(NS) yo]; 65.0% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) receiving or had previously received primary care service |

Community Primary Care Hospitals Long-term Care |

RGA | No | No | RGA significantly predicted fall history. However, 80% of older adults were assessed at the hospital & long-term care setting where older adults were generally older |

|

Maggio et al., 2020 [30] |

To validate the Sunfrail Checklist in primary care, verify its discriminating capacity of identifying patients requiring CGA | Descriptive, observational study |

n = 122 [81(4) yo]; 53.3% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) |

Primary Care | Sunfrail Checklist | No |

Yes The degree of agreement between GP & CGA on frailty is 66.3%, with a Cohen k of 0.353; NPV of 84.6% |

Sunfrail Checklist cannot replace the CGA. The Sunfrail Checklist seems to be an excellent screening tool of frailty due to its high discriminating power of false negatives |

| Matthews et al., 2004 [36] | To validate the SFQ & examine its association with the outcomes of institutionalisation & death at 3-year follow-up | Validation and longitudinal study |

n = 48 [76.2(NS) yo]; 60.4% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 63yo) receiving primary care service |

Community Primary Care | SFQ | No |

Yes SFQ was correlated to Timed Up and Go and repetitive Sit-to-Stand tests, bimanual dexterity |

The inclusion of additional cognitive assessment tools (modified SFQ) improved the gap of SFQ which are self-reported-based The “modified” SFQ score but not the SFQ score was a significant predictor of institutionalisation and death combined |

|

Merchant et al., 2020 [31] |

To explore the feasibility & implementation of RGA iPad application, prevalence of frailty, sarcopenia & anorexia of ageing | Feasibility study |

n = 2589 [73.1(6.5) yo] 52.5% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) receiving primary care service |

Primary Care | RGA | No | No | The RGA app is a rapid & feasible tool to be used in primary care for identification of geriatric syndrome & assisted management |

|

Moore et al., 1997 [32] |

To examine the effectiveness of BGA coupled with clinical summaries designed to assist physicians in managing the screen identified problems in community-based clinic | Cluster RCT |

n = 261 [76.4(NS) yo]; 70.9% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 70yo) newly received primary care service |

Primary Care | NS | No | No | Hearing loss was more commonly diagnosed & managed by physicians for patients in the intervention group compared to the control group. No other differences were detected between the two groups |

|

Mueller et al., 2018 [10] |

To examine the diagnostic performance of a brief assessment tool compared to a CGA | Prospective diagnostic study (validity) |

n = 85 [78(6) yo]; 54.1% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 70yo) |

Primary Care | NS | No |

Yes Sensitivity 25% (undernutrition) to 82.1% (hearing impairment); specificity 45.8% (visual impairment) to 87.7% (undernutrition). NPV 73.5% to 84.1%, except visual impairment 50.0% |

The performance of the Brief Assessment Tool in detecting geriatric syndromes compared to a CGA was satisfactory for most syndromes |

|

Mueller et al., 2021 [33] |

To determine whether the Active Geriatric Evaluation (AGE) tool, which consists of brief assessment & management plans, could slow functional decline in older patients | Cluster RCT |

n = 429 [82.5(4.8) yo]; 62.7% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) who visited GP at least twice in the past year |

Primary Care | NS | No | No | BGA cum management of geriatric syndrome from AGE did not slow functional decline of patients aged 75 years and older over a 2-year course compared with routine care. There was no significant difference in the quality of life & healthcare use between the intervention and control group |

|

Oubaya et al., 2014 [23] |

To validate the psychometric properties of the SEGAm | Longitudinal, prospective |

n = 167 [77(7) yo]; 70.7% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) |

Community | SEGAm |

Yes Internal consistency was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient at 0.68, & test–retest reliability with intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.88 |

Yes Good discriminant capacity in differentiating those with good versus poor performance in mood, nutrition, balance, autonomy & comorbidities, except for the cognitive function |

SEGAm instrument is recommended for use by all those involved in gerontological & geriatric care, to detect patent or latent frailty, with the caveat of valid cognitive evaluation |

| Rubenstein et al., 2007 [24] | To examine the effectiveness of a system consists of screening, assessment, referral, & follow-up provided within primary care for high-risk older outpatients | RCT |

n = 792 [74.4(6.0) yo]; 3.2% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) who have multiple geriatric problems |

Community | GPSS | No | No |

This study demonstrated that a system of postal screening, case finding, assessment, referral, & follow-up case management can increase the recognition and evaluation of geriatric conditions & improve access to geriatric services |

|

Sanford et al., 2020 [39] |

To assess the prevalence of the 4 geriatric syndromes of dementia, frailty, sarcopenia, & weight loss utilising the RGA | Prevalence study (secondary analysis of clinical data) |

n = 11,344 [NS yo]; NS ♀ Older adults (≥ 65yo) |

Community Primary Care Hospitals Long-term Care |

RGA Advanced directive |

No | No | The RGA, a valid screening tool, identified the prevalence of one or more of the geriatric syndromes of frailty, sarcopenia, weight loss, & dementia in the older adult population across all care continuums to be high |

|

Tai et al., 2021 [11] |

To develop an appropriate BGA tool to diagnose & manage geriatric syndromes for community-dwelling older adults | Development and validation study |

n = 1258 [73.5(6.2) yo]; 53.2% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) |

Community | NS | No |

Yes Sensitivities 48% to 97.6% for 6MWT; 58.3% for cognitive impairment; 62.7% for mood impairment |

The Rinne tuning fork test, Snellen scale test, BMI, wall-occiput distance, or rib-pelvis distance were included into the final version of the BGA |

|

Tan et al., 2021 [37] |

To develop and cross-validate self-administered (SA)-RGA against Administrator-administered (A)-RGA to identify seniors with geriatric syndromes | Development and validation study |

n = 123 [71(5.9) yo]; NS ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 60yo) |

Community Primary Care | RGA | No |

Yes High sensitivity, specificity, NPV & positive likelihood ratio on questions pertaining to fatigue, 5 or more illnesses, weight loss & falls in the past year There were discrepancies for functional assessment & SARC-F between the self-administered & administrator-administered RGA |

There remains discrepancy between self-administered & administrator-administered RGA for functional performance & strength evaluation Cognitive domain could not be assessed |

| Woo et al., 2015 [25] | To explore the feasibility of using the FRAIL scale in a community screening, followed by clinical validation using CGA of those classified as pre-frail or frail | Feasibility study |

n = 816 [NS yo]; 85.4% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 65yo) |

Community | FRAIL | No | No | This study shows that the FRAIL scale may be used by non-healthcare professionals as a community screening tool for frailty, as part of a step care approach to primary care for older people |

| Yu et el., 2021 [26] | To examine the psychometric properties of the online version of the FRAIL scale & its implementation acceptability | Feasibility study & longitudinal study |

n = 1882 [75.2(7.3) yo]; 76.8% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 60yo) |

Community | FRAIL | No | Yes | It is a validated & acceptable frailty screening tool for use by older persons and community centre staff |

|

Zulfiqar 2021 [34] |

To examine the validity of the ZFS tool & its implementation acceptability & feasibility | Validation & prospective study |

n = 102 [82[NS] yo]; 53.9% ♀ Community-dwelling older adults (≥ 75yo) |

Primary Care | ZFS | No | Yes | In comparison with CGA, ZFS yielded sensitivity 89.5%, specificity 68.9%, PPV 78.5% & NPV 83.8% |

Abbreviations: ADL Activities of Daily Living, AUC Area under the ROC curve, BGA Brief Geriatric Assessment, BMI Body Mass Index, BRIGHT Brief Risk Identification of Geriatric Health Tool, CGA Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment, EARRS Elderly at risk rating scale, GPSS Geriatric Postal Screening Survey, GP General Practitioners, HCOASS High-need Community Older Adults Screening Scale, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, LWAH-RS Live Well at Home Rapid Screen Tool, NS Not specified, RGA Rapid Geriatric Assessment tool, SEGAm Modified Short Emergency Geriatric Assessment, NPV Negative predictive value, PPV Positive predictive value, RCT Randomised Controlled Trials, SPICE Senses, Physical ability, Incontinence, Cognition and Emotional Distress, SFQ Strawbridge Frailty Questionnaire, yo years old, ZFS Zulfiqar Frailty Scale, 6MWT 6-min walk test, ♀ female

Studies on BGA were reported since the 1990s with two studies published in 1997 [19, 32], five studies in the 2000s [17, 24, 29, 35, 39], eight studies in the 2010s [10, 20–23, 25, 27, 28] and the remaining 10 studies from 2020 onwards [11, 18, 26, 30, 31, 33, 34, 37–39].

Seven studies were conducted in North America [17, 20, 24, 32, 36, 38, 39], one in South America [28], two in United Kingdom [19, 29], six in Europe [10, 23, 27, 30, 33, 34] and the remaining nine studies in either Oceania [21, 22, 35] or Asia [11, 18, 25, 26, 31, 37].

Study population

A total of 79,560 older adults were examined in the included studies. Their mean age was 79.7 years in 21 studies (n = 67,027). Four studies [19, 20, 25, 39] did not report the mean age. Among the 22 studies that reported gender distribution, female older adults (n = 41,034) accounted for 60.4% of the study population (n = 67,981). Ten studies involved older adults aged 65 years old and above [11, 17, 18, 23–25, 27, 31, 38, 39] while four studies examined the younger age group of 60 to 64 years old [26, 28, 36, 37]. The remaining studies adopted higher age cut-offs of either 70 [10, 32] or 75 years and above [19, 21, 22, 29, 30, 33–35]. The age requirement was not documented in one study [20].

BGA tools

Rapid Geriatric Assessment tool (RGA) was the most studied BGA tool [28, 31, 37–39], with the question on incontinence [28] or advanced directive [39] included as an additional item in two studies. The Brief Risk Identification of Geriatric Health Tool (BRIGHT) was examined in three studies [21, 22, 35] while two studies each used FRAIL scale [25, 26] and Geriatric Postal Screening Survey (GPSS) [17, 24]. The remaining studies adopted other BGA tools such as Elderly At Risk Rating Scale (EARRS) [19], High-need Community Older Adults Screening Scale (HCOASS) [18], Live Well at Home Rapid Screen (LWAH-RS) Tool [20], Senses, Physical ability, Incontinence, Cognition and Emotional distress (SPICE) [27], Sunfrail Checklist [30], Strawbridge Frailty Questionnaire (SFQ) [36], Modified Short Emergency Geriatric Assessment (SEGAm) [23], and Zulfiqar Frailty Scale (ZFS) [34]. There was no specific name of the BGA in five studies [10, 11, 29, 32, 33].

Assessed domains

The British Geriatric Society (BGS) CGA Toolkit for Primary Care Practitioners [5] was used to guide classification of the assessment domains for the BGA tools studied. The recommended six domains for assessment are Physical, Socioeconomic/Environmental, Functional, Mobility/Balance, Psychological/Mental and Medication Review. The included studies adopted BGA covering two to six domains from the BGS guidance. The coverage of four domains was most common [10, 20–22, 32, 33, 35], followed by five domains [17, 18, 23, 24, 30, 34], two domains [28, 31, 37–39], three domains [11, 27, 36], six domains [19, 29] and one domain [25, 26].

Physical [10, 17–19, 21–39] and psychological/mental [10, 11, 17–24, 27–39] domains were most commonly assessed, followed by mobility/balance [10, 11, 17–24, 27, 29, 30, 32–36] and functional [10, 11, 17–24, 29, 32, 33, 35]. Medication review [17, 19, 23, 24, 29, 30, 34] and socioeconomic [18–20, 29, 30, 34] were the least assessed domains (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the BGA tools adopted in the selected studies

| Authors | BGA tool | Duration | Administration | Physical | Socioeconomic / Environmental | Functional | Mobility / Balance | Psychological / Mental | Medication Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alessi et al., 2003 [17] | GPSS | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | · | · | |

| Balsinha et al., 2018 [27] | SPICE | 8 min | General practitioners | · | · | · | |||

| Chen et al., 2020 [18] | HCOASS | NS | Volunteers | · | · | · | · | · | |

| de Souza Orlandi et al., 2018 [28] |

RGA Incontinence |

NS | NS | · | · | ||||

| Donald 1997 [19] | EARRS | 10 to 15 min | Nurses / Doctors | · | · | · | · | · | · |

| Fletcher et al., 2004 [29] | NS | NS | Nurse, non-healthcare professional & older adults | · | · | · | · | · | · |

|

Gaugler et al., 2011 [20] |

LWAH-RS | 12 min | Caregiver coaches, care consultants, or support planners | · | · | · | · | ||

| Kerse et al., 2008 [35] | BRIGHT | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | · | ||

| Kerse et al., 2015 [21] | BRIGHT | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | · | ||

| King et al., 2017 [22] | BRIGHT | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | · | ||

| Lach et al., 2023 [38] | RGA | A few minutes | Professionals, students & trained volunteers | · | · | ||||

| Maggio et al., 2020 [30] | Sunfrail checklist | NS | General practitioners | · | · | · | · | · | |

| Matthews et al., 2004 [36] | SFQ | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | |||

| Merchant et al., 2020 [31] | RGA | ≤ 5 min | Trained care coordinators and/or nurse | · | · | ||||

| Moore et al., 1997 [32] | NS | 10 min | General practitioners | · | · | · | · | ||

| Mueller et al., 2018 [10] | NS | 20 min | General practitioners | · | · | · | · | ||

| Mueller et al., 2021 [33] | NS | 20 min | General practitioners / medical assistants | · | · | · | · | ||

| Oubaya et al., 2014 [23] | SEGAm | 5 min | Professionals, nurses & trained personnels | · | · | · | · | · | |

| Rubenstein et al., 2007 [24] | GPSS | NS | Older adults | · | · | · | · | · | |

| Sanford et al., 2020 [39] |

RGA Advanced directive |

4 to 5 min | Doctors, nurses, allied health & social workers | · | · | ||||

| Tai et al., 2021 [11] | NS | < 10 min | Trained personnel | · | · | · | |||

| Tan et al., 2021 [37] | RGA | ≤ 5 min | Older adults, healthcare personnel | · | · | ||||

| Woo et al., 2015 [25] | FRAIL | NS | Trained personnel | · | |||||

| Yu et al., 2021 [26] | FRAIL | NS |

Older adults, trained personnel |

· | |||||

| Zulfiqar 2021 [34] | ZFS | > 2 min | General practitioners | · | · | · | · | · |

Abbreviations: BRIGHT Brief Risk Identification of Geriatric Health Tool, EARRS Elderly at risk rating scale, GPSS Geriatric Postal Screening Survey, HCOASS High-need Community Older Adults Screening Scale, LWAH-RS Live Well at Home Rapid Screen Tool, NS Not specified, RGA Rapid Geriatric Assessment, SEGAm Modified Short Emergency Geriatric Assessment, SPICE Senses, Physical ability, Incontinence, Cognition and Emotional distress, SFQ Strawbridge Frailty Questionnaire, ZFS Zulfiqar Frailty Scale

BGA implementation

Assessment mode

Most of the assessments were conducted primarily through in-person interviews [10, 11, 18, 19, 23, 25, 27, 30–34, 38, 39]. Postal mail was relied on in four studies [17, 21, 22, 24] while two studies used web-based platforms [26, 37]. A combination of approaches, such as in-person and phone interviews [20] as well as in-person interviews and postal mails [29, 35, 36] were also reported. One study did not report its assessment method [28].

Assessors

Doctors [10, 19, 27, 30, 32–34, 39], nurses [19, 23, 29, 31, 39], trained personnel [11, 18, 20, 23, 25, 26, 29, 31, 33, 38, 39] and healthcare professional [37, 39] conducted BGA while eight studies [17, 21, 22, 24, 26, 29, 35, 36] reported older adults self-administering the BGA tools. One study did not document the BGA assessor [28].

Duration of the assessment

Among 13 studies that documented the duration of BGA, the shortest duration reported was five minutes or less [23, 31, 34, 37–39]. The remaining studies reported either 8 to 15 min [11, 19, 20, 27, 32] or 20 min [10, 33]. Twelve studies did not report the duration of the assessment [17, 18, 21, 22, 24–26, 28–30, 35, 36].

Evaluation and application of BGA

Application of the BGA in the clinical pathway

Six studies evaluated the effectiveness of implementing clinical intervention pathways with BGA as the initial screening process [21, 22, 24, 29, 32, 33]. The studies did not report significant change in the clinical outcomes of older adults [21, 24, 29, 32, 33] except for better identification of those with higher needs [22, 24, 32].

Examination of the utility and implementation feasibility of BGA

Nine studies examined the utility of BGA in identifying geriatric syndromes [25–27, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39] or predicting hospitalisation and mortality [36] among community-dwelling older adults who have received or are receiving primary care services [27, 31, 35, 36, 38, 39]. Conversely, age was used as the inclusion criterion in three of the studies [25, 26, 34]. In this review, utility is defined as the usefulness of BGA. The validation of BGA [25, 26, 34–36] and the feasibility of its implementation [27, 31, 34] were commonly reported. Positive findings regarding BGA’s utility in identifying unexpressed needs of older adults [27], predicting falls [38] and recognising geriatric syndromes [25, 26, 31, 34, 35, 39] were also noted.

Development and validation of BGA

Four studies focused on the development and reliability and/or validation of their respective BGA [11, 18, 19, 37]. One study reported the development and pilot of its BGA tool [20]. Five studies examined the validity of their BGA tools [10, 17, 23, 28, 30], among which three studies incorporated reliability examinations [17, 23, 28].

Discussion

Our findings indicate that BGA is not used as an abbreviation for CGA; rather, it serves as a precursor to step-up care, such as CGA, if BGA uncovers unexpressed needs or geriatric syndromes in older adults. Subjective self-report questionnaires are the primary method used in BGA and are administered by trained non-healthcare professionals. Enhanced health outcomes in older adults were not reported when BGA was paired with clinical intervention pathways. To our knowledge, this is the first review to assess the utility and implementation of BGA in primary care and community settings.

The adoption of BGA in community and primary care has been reported to facilitate the identification of community-dwelling older adults with psychological distress [27] or depression [31], compromised independence in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living [35], fall risk [31, 38], sarcopenia [31, 39], and anorexia [31, 39]. The studies also demonstrated the promising capability of BGA to identify frail older adults [25, 26, 31, 34, 39]. Since CGA is time-consuming, frailty screening is recommended for identifying older adults in need of CGA [40].

The intervention studies that integrated BGA into clinical intervention pathways in primary care and community settings did not document positive outcomes regarding mortality or functional ability among older adults. This corroborates similar findings from a previous systematic review on CGA in primary care [3]. The heterogeneity of clinical interventions, including follow-up assessments and delivered intervention (e.g., specialised intervention, education) as well as follow-up periods ranging from 6 months to 3 years, complicates the interpretations of the findings. Most of these studies recruited individuals aged 75 and older who were visiting or had visited primary care services, rather than younger age groups, as seen in the studies focusing on the utility of the BGA. The intention may have been to target frail older adults, who are generally above 75 years old [41] or to prioritise resources for screening those aged 75 and above in the community [42]. It may be worthwhile to examine the potential confounding factors affecting changes in outcomes for this vulnerable group, such as insufficient intervention intensity and patient adherence rates [24], to better guide the development and refinement of the implementation strategies of the targeted interventions.

Among the six assessment domains recommended by BGS for CGA, physical health, psychological/mental, functional ability, and mobility/balance are the four domains most commonly assessed in BGA. At a minimum, assessments of physical health and psychological/mental health are included. Frailty assessment tools such as FRAIL, SFQ and ZFS were among the BGA tools used in the identified studies. Frailty is a multidimensional syndrome characterised by a reduction in the physiological reserves of different body systems [43]. Of note, the psychological/mental health domain was included in the frailty assessment questionnaires, such as SFQ and ZFS. Additionally, the item on fatigue in the FRAIL scale has high sensitivity and specificity in identifying older adults at high risk of depression [37], and the assessment of fatigue is more oriented toward a psychological interpretation [44]. The assessment of socioeconomic/environmental factor is less emphasised in BGA compared to CGA, possibly because socio-environmental resources are important considerations for physicians when selecting and prioritising targeted interventions for patients [6]. However, these factors are less emphasised during the initial screening in the two-stage process of geriatric assessment [42].

Majority of the included studies avoided using objective measurements, which are typically more time-consuming. Self-reported questionnaires, whether interviewer-administered or self-administered are the main approach in BGA. While the validity of self-reported questionnaires for physical, functional, mobility, psychological domains are generally acceptable, the cognitive domain falls short [11, 17, 23, 34, 36]. Self-reported memory decline is commonly elicited in BGA [17, 20, 23, 30, 34–36]. Although it could indicate early dementia [45], it is not recommended as a proxy for cognitive assessment [45, 46]. The integration of objective measures of cognition [36] or input from caregivers [34] helps improve the feasibility [34] and validity [36] of BGA tools.

Most versions of BGA can be completed within 10 min; however, they remain challenging for general practitioners to incorporate into routine clinical care [27]. Slightly less than half of the included studies engaged trained non-healthcare professionals to administer the tool, which aligns with the recommendation that geriatric assessment or screening should be quick and easy to administer without the need for healthcare resources, particularly if it aims to identify older adults in need of CGA [47]. While the agreement between clinician-administered and trained non-healthcare professional-administered BGA has not been well-examined, high agreement between clinician-administered and lay-person-administered geriatric assessment has been reported for inter-RAI [48]. Notably, about a third of the studies required older adults to self-administer the BGA, which could be a more sustainable approach since it is less resource-intensive. Web-based BGA [26, 37] has also emerged in the last decade. Better quality of responses from web-based assessments, in terms of fewer unanswered questions and longer responses to open-ended questions has been reported elsewhere [49], although the study population was not well-described. Nonetheless, both paper or web-based self-administered BGA has their challenges, particularly for older adults who may struggle with ambiguous terms. Phrases like “some difficulties” or “loss of weight” can be subjective and vary widely in interpretation [26, 37]. Incorporation of explanatory notes and probing questions to improve clarity in the meaning of questions is suggested as a way to address this issue [26, 37].

Our findings are consistent with the scope of the scoping review, which aims to examine emerging evidence and identify knowledge gaps [50] regarding the utility and implementation of BGA in community and primary care settings. The current evidence suggests that BGA can serve as a screening tool to identify older adults with unexpressed needs or geriatric syndromes who may require step-up care. Therefore, the findings of our scoping review indicate that BGA should be easily implemented and completed within 10 min. The widespread use of a self-reported questionnaire suggests its feasibility. At a minimum, BGA should include assessments of physical health and psychological/mental domains, though mobility, balance, and functional abilities are also commonly assessed. Furthermore, BGA may not need to be conducted by healthcare professionals, as several studies have involved non-healthcare professionals as assessors.

The relatively small number of studies identified for this review, combined with the heterogeneity of the BGA tools used, has limited the depth and breadth of our analysis. The identification of only 25 studies may be attributed to the exclusion criteria, which excluded settings such as specialist outpatient clinics and emergency department. We believed that the older adults recruited from these settings would have different needs and intervention compared to those residing in the community.

Considering the sampling approaches adopted by most studies, it appears that the primary goal of BGA may be to conduct case-finding among those at risk for adverse health outcomes, rather than focusing solely on age as a criterion. However, it is important to approach this interpretation with caution, as many individuals may present with diverse health issues when seeking primary care, ranging from routine check-ups to significant concerns. Future research is needed to identify which subgroups of older adults benefit most from BGA when combined with additional evaluations and interventions, as well as to consider differential treatment effects by age [51].

The implementation of questionnaire-based BGA is less resource-intensive and allows for self-administration by older adults, However, its accessibility for older adults with low literacy or upper extremities mobility limitations remains a concern. Therefore, future studies should: a) explore the feasibility of audio-delivered, web-based questionnaires [52]; b) further examine and refine self-reported questionnaires for the cognitive domain to enhance their validity, potentially incorporating a hybrid approach to cognitive assessment, such as input from informants [53] and/or objective assessments by healthcare professionals; and c) investigate the impact of screening older adults' social situations on long-term health outcomes for this vulnerable group, given the strong association between social situations and both physical and mental health [54, 55].

Conclusion

Our review’s findings bolster the understanding of BGA as a feasible tool for identifying older adults with unexpressed needs and geriatric syndromes. It can serve as a precursor to step-up care if the assessment uncovers significant needs, typically including evaluations of both physical and psychological/mental domains. However, there is lack of evidence regarding its effectiveness in improving their health outcomes when combined with clinical intervention pathways. The ambiguity surrounding which subgroups of older adults would benefit most from BGA assessment and follow-up interventions presents a valuable opportunity for future research.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank A/Prof Lim Wee Shiong, A/Prof Reshma Aziz Merchant and A/Prof Laura Tay for their expert input to this review.

Abbreviations

- CGA

Comprehensive geriatric assessment

- BGA

Brief geriatric assessment

- CENTRAL

Cochrane central register of controlled trials

- RGA

Rapid geriatric assessment tool

- BRIGHT

Brief risk identification of geriatric health tool

- GPSS

Geriatric postal screening survey

- EARRS

Elderly at risk rating scale

- HCOASS

High-need community older adults screening scale

- LWAH-RS

Live well at home rapid screen

- SPICE

Senses, physical ability, incontinence, cognition and emotional distress

- SFQ

Strawbridge frailty questionnaire

- SEGAm

Modified short emergency geriatric assessment

- ZFS

Zulfiqar frailty scale

- BGS

British geriatric society

Authors’ contributions

L.K.Lau, P.Lun, J.Gao, E.Tan and Y.Y. Ding conceptualized and designed the study methodology. Article screening and full text review were completed by L.K.Lau, P.Lun and J.Gao. Data extraction was completed by L.K.Lau, P.Lun and J.Gao. Manuscript write including data analysis, preparation of tables and figures was completed by L.K.Lau, P.Lun, J.Gao and Y.Y.Ding.

Funding

This review received no funding from any source.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Parker SG, McCue P, Phelps K, et al. What is Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA)? An umbrella review. Age Ageing. 2018;47:149–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilotto A, Cella A, Pilotto A, et al. Three decades of comprehensive geriatric assessment: evidence coming from different healthcare settings and specific clinical conditions. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18:192.e1-192.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrard JW, Cox NJ, Dodds RM, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment in primary care: a systematic review. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aliberti MJR, Covinsky KE, Apolinario D, et al. 10-Minute targeted geriatric assessment predicts disability and hospitalization in fast-paced acute care settings. J Gerontology: Series A. 2019;74:1637–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Society BG. Comprehensive geriatric assessment toolkit for primary care practitioners. 2019.

- 6.Seematter-Bagnoud L, Büla C. Brief assessments and screening for geriatric conditions in older primary care patients: a pragmatic approach. Public Health Rev. 2018;39:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachana NA, Mitchell LK, Pinsker DM, et al. In brief, look sharp: short form assessment in the geriatric setting. Aust Psychol. 2016;51:342–51. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stijnen MMN, Van Hoof MS, Wijnands-Hoekstra IYM, et al. Detected health and well-being problems following comprehensive geriatric assessment during a home visit among community-dwelling older people: who benefits most? Fam Pract. 2014;31:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouman A, van Rossum E, Nelemans P, et al. Effects of intensive home visiting programs for older people with poor health status: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mueller YK, Monod S, Locatelli I, et al. Performance of a brief geriatric evaluation compared to a comprehensive geriatric assessment for detection of geriatric syndromes in family medicine: a prospective diagnostic study. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai C-J, Yang Y-H, Huang C-Y, et al. Development of the brief geriatric assessment for the general practitioner. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:134–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morley JE, Adams EV. Rapid geriatric assessment. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:808–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd M, Koziol-McLain J, Yates K, et al. Emergency department case-finding for high-risk older adults: the Brief Risk Identification for Geriatric Health Tool (BRIGHT). Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:598–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon D, Brown AS, Brummel-Smith K et al. Best paper of the 1980s: National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: geriatric assessment methods for clinical decision-making. 1988. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1490–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Andrea C. Tricco, Ka Shing Li. Scoping reviews: what they are and how you can do them. Cochrane Training 2017.

- 16.Covidence software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at https://www.covidence.org.

- 17.Alessi CA, Josephson KR, Harker JO, et al. The yield, reliability, and validity of a postal survey for screening community-dwelling older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen M-C, Chen K-M, Wang J-J, et al. Development of a screening scale for community-dwelling older adults with multiple care needs. Clin Gerontol. 2020;43:308–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donald IP. Development of a modified Winchester disability scale–the elderly at risk rating scale. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978;1997(51):558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaugler JE, Boldischar M, Vujovich J, et al. The Minnesota live well at home project: Screening and client satisfaction. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2011;30:63–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerse N, McLean C, Moyes SA, et al. The cluster-randomized BRIGHT trial: proactive case finding for community-dwelling older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:514–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.King A, Boyd M, Dagley L. Use of a screening tool and primary health care gerontology nurse specialist for high-needs older people. Contemp Nurse. 2017;53:23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oubaya N, Mahmoudi R, Jolly D, et al. Screening for frailty in elderly subjects living at home: validation of the Modified Short Emergency Geriatric Assessment (SEGAm) instrument. J Nutr Health Aging. 2014;18:757–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubenstein LZ, Alessi CA, Josephson KR, et al. A randomized trial of a screening, case finding, and referral system for older veterans in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo J, Yu R, Wong M, et al. Frailty screening in the community using the FRAIL scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16:412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu R, Tong C, Leung G, et al. Assessment of the validity and acceptability of the online FRAIL scale in identifying frailty among older people in community settings. Maturitas. 2021;145:18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balsinha C, Marques MJ, Gonçalves-Pereira M. A brief assessment unravels unmet needs of older people in primary care: a mixed-methods evaluation of the SPICE tool in Portugal. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2018;19:637–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Souza OF, Lanzotti RB, Duarte JG, et al. Translation, adaptation and validation of rapid geriatric assessment to the Brazilian context. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22:1115–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fletcher AE, Price GM, Ng ESW, et al. Population-based multidimensional assessment of older people in UK general practice: a cluster-randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1667–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maggio M, Barbolini M, Longobucco Y, et al. A novel tool for the early identification of frailty in elderly people: the application in primary care settings. J Frailty Aging. 2020;9:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merchant RA, Hui RJY, Kwek SC, et al. Rapid geriatric assessment using mobile app in primary care: Prevalence of geriatric syndromes and review of its feasibility. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore AA, Siu AL, Partridge JM, et al. A randomized trial of office-based screening for common problems in older persons. Am J Med. 1997;102:371–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller Y, Schwarz J, Monod S, et al. Use of standardized brief geriatric evaluation compared with routine care in general practice for preventing functional decline: a pragmatic cluster-randomized trial. CMAJ. 2021;193:E1289–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zulfiqar A-A. Creation of a new frailty scale in primary care: the Zulfiqar frailty scale (ZFS). Medicines. 2021;8:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerse N, Boyd M, Mclean C, et al. The BRIGHT tool. Age Ageing. 2008;37:553–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews M, Lucas A, Boland R, et al. Use of a questionnaire to screen for frailty in the elderly: an exploratory study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan LF, Chan YH, Tay A, et al. Practicality and reliability of self vs administered rapid geriatric assessment mobile app. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25:1064–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lach HW, Berg-Weger M, Washington S, et al. Falls across health care settings: Findings from a geriatric screening program. J Appl Gerontol. 2023;42:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanford AM, Morley JE, Berg-Weger M, et al. High prevalence of geriatric syndromes in older adults. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0233857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turner G, Clegg A. Best practice guidelines for the management of frailty: a British Geriatrics Society, Age UK and Royal College of General Practitioners report. Age Ageing. 2014;43:744–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bernabei R, Venturiero V, Tarsitani P, et al. The comprehensive geriatric assessment: when, where, how. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;33:45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iliffe S, Gould M, Wallace P. Assessment of older people in the community: lessons from Britain’s ‘75-and-over checks.’ Rev Clin Gerontol. 1999;9:305–16. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knoop V, Costenoble A, Azzopardi RV, et al. The operationalization of fatigue in frailty scales: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;53: 100911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eramudugolla R, Cherbuin N, Easteal S, et al. Self-reported cognitive decline on the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly is associated with dementia, instrumental activities of daily living and depression but not longitudinal cognitive change. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2013;34:282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rabin LA, Smart CM, Crane PK, et al. Subjective cognitive decline in older adults: an overview of self-report measures used across 19 international research studies. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015;48:S63-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Terret C. How and why to perform a geriatric assessment in clinical practice. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:vii300–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Geffen LN, Kelly G, Morris JN, et al. Establishing the criterion validity of the interRAI Check-Up Self-Report instrument. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Rada VD, Domínguez-Álvarez JA. Response quality of self-administered questionnaires: A comparison between paper and web questionnaires. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2014;32:256–69. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, et al. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, et al. Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:783–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murphy-Okpala N, Dahiru T, van’t Noordende AT et al. Participatory Development and Assessment of Audio-Delivered Interventions and Written Material and Their Impact on the Perception, Knowledge, and Attitudes Toward Leprosy in Nigeria: Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2024;13:e53130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Song Y, Zhu C, Shi B et al. Social isolation, loneliness, and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from two large prospective cohorts in Europe and East Asia and Mendelian randomization. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;64:1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Dong Y, Pang WS, Lim LBS, et al. The informant AD8 is superior to participant AD8 in detecting cognitive impairment in a memory clinic setting. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013;35:159–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyawaki CE. Association of social isolation and health across different racial and ethnic groups of older Americans. Ageing Soc. 2015;35:2201–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.