Abstract

Inroduction

The Simulation-based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) is a valuable instrument for evaluating individual performance within interprofessional teams.

Aim

This study aimed to translate and validate the SITAT into Turkish (SITAT-TR) to enhance interprofessional education and teamwork assessments in the Turkish context.

Methods

This study was designed as an adaptation study in a descriptive research design. Ethical approval was obtained for the study. The process of Turkish translation and cross-cultural adaptation was completed. Subsequently, a simulation scenario was developed. The scenario was performed and recorded by standardized patients representing professionals in different roles. These videos were then reviewed by students from various professions to conduct validity and reliability studies.

Results

This study evaluated 345 students from five professions at Süleyman Demirel University, using the SITAT-TR scale. Psychometric analysis showed strong validity with high content validity indices (I-CVI: 0.95–1.00; S-CVI/Ave, 0.98) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.915). Suitability of factor analysis was confirmed by a high KMO value (0.940) and significant Bartlett’s test results, supporting a unidimensional structure. Simulation-based competency assessments revealed mostly ‘proficient’ ratings, with significant differences between physicians and dietitians in certain tests (SP2 and SP4). These findings highlight the reliability of the SITAT-TR and its generally high competency levels within interprofessional teamwork in healthcare settings.

Conclusion

This study showed that the Turkish version of the Simulation-Based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) can be used as a valid and reliable measurement tool.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-024-06398-8.

Keywords: Simulation-based learning, İnterprofessional Teamwork, Adaptation, Validity, Reliability

Introduction

Interprofessional teamwork is critical for delivering high-quality healthcare and improving patient outcomes. It involves collaboration among healthcare professionals from various professions, combining diverse knowledge and skills towards a common goal [1]. This collaborative approach is not only essential in routine healthcare settings but also proves vital during public health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where effective teamwork can support healthcare worker resiliency and patient safety [2]. However, the literature reveals challenges to effective interprofessional teamwork, including communication barriers, inconsistent motivation levels among team members, and the need for organizational support [3, 4]. These challenges are compounded during crises, when remote work can disrupt established teamwork dynamics [2]. Additionally, external barriers such as the attitudes of healthcare insurers and municipalities can impede the development of effective Interprofessional teams [5]. Despite these challenges, interventions such as care pathways, Crew Resource Management skills, and interprofessional meetings have been suggested to enhance teamwork and patient care [1, 6]. While interprofessional teamwork is crucial for patient-centered care and health care provider well-being, it faces several obstacles that need to be addressed. Interventions to improve teamwork should focus on enhancing communication, organizational support, and inclusion of all relevant stakeholders. The literature underscores the importance of a supportive organizational context and the need for healthcare systems to adapt to facilitate effective Interprofessional collaboration [5, 7]. To achieve the full benefits of interprofessional teamwork, healthcare organizations must commit to continuous improvement and address multilevel factors that influence team dynamics and patient outcomes [8–10].

Interprofessional education enables students from various professions to practice teamwork and communication skills in a controlled environment, leading to enhanced interprofessional communication and clinical decision making [11]. Research indicates that simulation-based IPE positively influences the attitudes and competencies of medical and nursing students, thereby improving their interprofessional learning experiences [12, 13]. Moreover, periodic interprofessional training has been shown to enhance knowledge, skills, and retention of learned abilities [14].

Simulation-based interprofessional teamwork assessment tools are essential for evaluating individual performance [15]. A Simulation-Based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) was developed to assess the effectiveness of interprofessional education (IPE) through simulations [16]. This tool, created using the Delphi methodology to achieve expert consensus, comprises 16 items aimed at evaluating an individual’s performance in an interprofessional team setting [15, 16]. The first version of the SITAT was created from a successful Delphi study, and the original version had weak validity. However, the design and strong validity evidence of Turkish adaptation were demonstrated in our study. Simulation-based education has been demonstrated to be effective in improving teamwork, particularly in emergency settings, and has resulted in enhanced teamwork within interprofessional teams [17]. The use of simulations in interprofessional learning has proven effective in cultivating a broad array of skills, including communication, teamwork, leadership, and understanding others’ roles [18].

To develop work patterns related to interprofessional collaboration in Turkey, the adaptation of measurement tools into Turkish is a barrier. Therefore, it is recommended that these adaptation studies be performed in the early stages of development. These tools are essential for enhancing students’ learning outcomes and experiences in interprofessional settings [19]. Moreover, the development of observational measures for assessing performance in various settings, such as surgical teams, is vital for understanding and enhancing teamwork [20]. Interprofessional point-of-care simulation training has been shown to enhance safety culture and teamwork in hospital environments, underscoring the importance of such training in healthcare settings [21].

The originality of this study stems from the evaluation of a video that features simulated patients at various roles and levels within a clinical case-based simulation scenario by students from multiple professions. This unique aspect encompasses Turkish adaptation of the tool and examines its application from the perspective of different disciplinary fields.

The adaptation of the Simulation-Based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) into Turkish (SITAT-TR) can significantly enhance interprofessional education and teamwork evaluation in simulation settings. This study aims to contribute to the validation process with all its elements, rather than just a translation. By drawing on insights from various studies on simulation-based training, academic writing, and teamwork assessment, the introduction of SITAT-TR can provide a valuable resource for evaluating and improving interprofessional teamwork in Turkish-speaking contexts.

Aim

The aim of this study is to make the adaptation of the Simulation-Based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) into Turkish (SITAT-TR).

Methods/design

For this study, permission was first obtained from the scale developers. Then, the data collection process was started after receiving ethics committee approval.

Translation and intercultural adaptation

For the adaptation process, the recommended guidelines for the translation, adaptation, and validation of measurement scales for cross-cultural health research were used to develop the Turkish version of the SITAT [22, 23] (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Adaptation process procedure

Translation process

Step 1 involved the translation of the English version (SITAT-EN) to the Turkish version (SITAT-TR). A team comprised of seven individuals with diverse interprofessional backgrounds (a medical educator, a dietician, a physician, a physical therapist, a paramedic, a medical laboratory technician, and a certified translator with fluency in both languages) was assembled to accomplish this task.Team members completed their translations by themselves then an online discussion session was held to create a common text and the first Turkish version was obtained (SITAT-v1). First, translators translated the scale within the scope of their language proficiency. In Step 2, they worked together for the first Turkish version in Step 2, the translation and intercultural adaptation of the SITAT. Translators attempted to achieve semantic integrity and verbal consensus using the nominal group technique. The words and expressions used in the original SITAT were preserved to the greatest extent possible. The changes were made only when the participating authors believed that this was necessary. In Turkish, the same expression can be used in different ways. As prevalence is important in adaptation studies, its widespread use is preferred in terms of intelligibility. Unnatural or uncommon Turkish expressions have been identified in certain substance formulations. This has been replaced by a consensus among the authors. Step 3 involved backward translation from Turkish to English. The Turkish-v1 draft form was translated back into English by a team of three people (two medical educators and one linguist (a certified translator)). Step 4 consists of comparing texts. Five team members discussed disagreements regarding the clauses in an online discussion session and obtained a draft text. This draft text was finalized based on a linguist’s feedback and then shared with the developers of the original rubric for their feedback. The developers of the original rubric compared the reversed version to the original version. It approved the use of the scale as ‘SITAT-TR’ by its international name. Step 5 involved testing the scale and its comprehension ability. To ensure content validity, the items were evaluated by a team that consisted of the same professions as those involved during later data collection. Therefore, at least one professional from each profession participated in this evaluation. Opinions were collected from 12 specialists across six professions: medical educators (2), dietitians (2), physicians (2), physiotherapists (2), paramedics (2), and medical laboratory technicians (2). Participants were asked to evaluate the clarity of the items (Item not suitable/Item Should be Seriously Reviewed/Item Must Be Slightly Reviewed/Item Eligible) and revise the proposals for incomprehensible items. The items were accepted as comprehensible, with an agreement of 85% and above for all respondents of the evaluation team. The experts’ feedback was evaluated in the scale validity analysis, and the item and scale content validity indices were calculated. Minimum and maximum item content validity index (I-CVI) were calculated as 0.95 and 1.00, respectively. In the calculation of the scale content validity index, the mean value of the scale content validity (SCVI/Ave) was 0.98. The desired level and understandable items were recorded in the measurement tool, whereas the others were revised based on participants’ suggestions.

Revisions were made following feedback from the scale developer and evaluation team, and the SITAT-TRv2 was created. Subsequently, a team of four experts working on medical education and rubric development was consulted, and, according to their suggestions, the last version of the SITAT-TR was created. In Step 5, all the authors discussed the comments for Step 4. In step 6, they considered their common conclusions and suggestions when developing the translated version 2. Step 7 involved pilot testing with a convenience sample of another group of 345 respondents. A pilot study was conducted to determine the validity and reliability of the final version of the scale, developed after receiving expert feedback.

Simulation scenario

For study, a scenario was developed by subject matter experts and medical educators. In this scenario, the treatment planning process for a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus who was hospitalized in the ward was expressed. In this scenario, there were employees from different professions such as dietitians, physicians, nurses, and physiotherapists. Various roles were determined for these employees in accordance with their duties and responsibilities, with different characteristics in accordance with the SITAT. The four simulated patients played the assigned roles. The physician was determined to be the team leader, and the dietitians and nurses were compatible team members. The physiotherapist was randomly designed as a weak and incompatible team member. Simulated patients working in our medical faculty’s simulated patient laboratory were asked to perform these roles. The performance was recorded.

Demographic findings, videos, and SITAT items were prepared in Google forms and shared with students online. In the video instructions, students from different professional fields were asked to watch the video and evaluate the role of their choice using SITAT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assigned professions and roles of team members

| Team Member | SP1 | SP2 | SP3 | SP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assigned Profession | Dietitian | Physician | Nurse | Physiotherapist |

| Assigned Role | Team Member | Leader | Team Member | Team Member (Weak) |

Participants

Data were collected for psychometric analysis of the SITAT-TR from 345 students at the Süleyman Demirel University in Isparta (n = 345). These five professions were chosen because they are frequently used in studies of interprofessional education/collaboration in the literature. Participants were in five professions: Dietitian, Physician, Physiotherapist, Paramedic, and Medical Laboratory Technician, as listed in table (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequencies of participants and professions

| Professions | n | % | SP1 | SP2 | SP3 | SP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dietitian | 78 | 23% | 61 | 6 | 1 | 10 |

| Physician | 66 | 19% | 4 | 50 | 0 | 12 |

| Physiotherapist | 57 | 17% | 2 | 9 | 7 | 39 |

| Paramedic | 70 | 20% | 8 | 36 | 16 | 10 |

| Medical Laboratory Technician | 74 | 21% | 7 | 36 | 14 | 17 |

| All | 345 | 100% | 82 | 137 | 38 | 88 |

Data collection

In this research, particular emphasis is directed towards the potential for data collection related to the adapted scale within the framework of language and culture. This study recognizes the significance of insights from students representing diverse professional backgrounds, considering their valuable contributions to this data-gathering process. An online form (Google Forms) was used for the data collection. This form was subsequently distributed anonymously to students who were requested to share their views on professional identity. Data were collected between 25.03.2024–25.04.2024. No sample was included in this study. The study was carried out with volunteer students (n = 345).

Data analysis

Jamovi software was used for data analysis. Psychometric analysis was performed on the data collected using SITAT-TR for construct validity. Content validity indices are quantitative measures used to assess the content validity of a scale or test, and indicate how well the items represent the construct being measured. Content validity ensures that the instrument comprehensively and accurately reflects the domain it intends to measure. The two primary types of content validity indices are the Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI). The Item Content Validity Index was calculated for each item based on expert ratings of its relevance or appropriateness. Experts rated each item on a specific scale, and the I-CVI is typically expressed as a proportion ranging from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate greater content validity for the item. The content validity index reflects the overall content validity of the scale and can be calculated in two main ways. The S-CVI/UA, or universal agreement, considers the proportion of items for which all experts agree regarding content validity. The S-CVI/Ave, or average, calculated the mean I-CVI across all items, providing a broader measure of content validity for the scale as a whole. This approach is more commonly used because it reflects the general level of agreement among experts and is essential for determining whether a scale or test adequately covers the intended content area and maintains consistency in measuring the construct. For the reliability of the internal consistency of the subscales and the overall SITAT-TR scale, Cronbach’s alpha was used. Values > 0.70 were considered sufficient [24, 25]. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to explore statistical differences between the five professions.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Süleyman Demirel University Ethics Committee (Approval Date: 01.04.2022; no. 108). All participants were guaranteed their anonymity. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the participants had the right to withdraw or drop participation unconditionally or unconditionally at any time and of their own free will.

Results

A total of 345 students from five professions at Süleyman Demirel University participated in this study (n = 345). The data collected for the psychometric analysis of the SITAT-TR included students from five professions at the Süleyman Demirel University. There were 78 dietitians representing 23% of the total sample, 66 physicians accounting for 19% of the total sample, 57 physiotherapists accounting for 17% of the total sample, 70 paramedics constituting 20% of the total sample, and 74 Medical Laboratory Technicians comprising 21% of the total sample. A total of 345 students participated in this study. The participants gender was 65,50% (n = 226) female and 34,50% (n = 119) males. The average age of the participants was calculated as 21.33 ± 2.68 years (Table 2).

The findings of this study highlight the competency levels of different team members as evaluated by simulation-based interprofessional teamwork assessment. The overall mean scores and standard deviations for the assessment were as follows: the first evaluation yielded a mean score of 2.77 ± 0.77; the second evaluation showed a mean score of 3.30 ± 0.51; the third evaluation resulted in a mean score of 2.81 ± 0.51; and the fourth evaluation had a mean score of 2.67 ± 0.73. In terms of competency, the majority of the evaluations rated the team members as ‘proficient,’ with the second evaluation specifically rating a team member as ‘expert.’ Notably, even the weakest team member was rated as ‘proficient,’ indicating a generally high level of competency across the board. These results suggest that, despite their varying roles and levels within the simulation, team members demonstrated a strong ability to work together effectively, with particular strengths noted in specific evaluations. This comprehensive assessment provided valuable insights into team dynamics and individual performance in interprofessional settings (Table 3).

Table 3.

Frequencies and percentages detailed for respondents’ professions (n = 345)

| SP1 | SP2 | SP3 | SP4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professions | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Dietitian | 2.81 | 0.65 | 2.69 | 0.46 | 3.13 | 0 | 2.41 | 0.80 |

| Physician | 3.34 | 0.47 | 3.45 | 0.40 | 0 | 0 | 2.01 | 0.72 |

| Physiotherapist | 2.19 | 0.97 | 3.31 | 0.58 | 2.68 | 0.37 | 2.96 | 0.68 |

| Paramedic | 2.10 | 1.15 | 3.21 | 0.47 | 2.94 | 0.46 | 2.67 | 0.50 |

| Medical Laboratory Technician | 2.81 | 0.65 | 3.28 | 0.59 | 2.74 | 0.62 | 2.62 | 0.62 |

| All | 2.77 | 0.77 | 3.30 | 0.51 | 2.81 | 0.51 | 2.67 | 0.73 |

| Comment | Competent | Proficient | Competent | Competent (Weak) | ||||

Psychometric analysis

Content validity

In the scale validity analysis, expert feedback was evaluated and item and scale content validity indices were calculated. Minimum and maximum item content validity index (I-CVI) were calculated as 0.95 and 1.00, respectively. In the calculation of the scale content validity index, the mean value of the scale content validity (SCVI/Ave) was 0.98. Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the overall SITAT-TR was 0,91 and reliability values were above the norm of 0.70 [24, 25] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Internal consistency analyze of different roles

| SP1 | SP2 | SP3 | SP4 | Overall scale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach alfa | 0,925 | 0,873 | 0,864 | 0,916 | 0,915 |

However, this scale did not have predefined dimensions. The results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests indicated that the dataset was highly suitable for factor analysis. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy is 0.940, which falls within the ‘excellent’ range (values above 0.90 are considered excellent). This suggests that the sample size and variables included in the dataset were adequate for the factor analysis. Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity yielded significant results, with an approximate chi-square value of 2379.963 and a significance level (p-value) of less than 0.001. This result rejects the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, indicating significant correlations between variables. Both KMO and Bartlett’s tests confirmed that the dataset was appropriate for factor analysis. A high KMO value signifies excellent sample adequacy, and a significant Bartlett’s test indicates that the factor analysis will likely yield meaningful results because of the substantial correlations among the variables. These findings support the reliability and validity of factor analysis of this dataset. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to determine the potential variations due to population and cultural differences. The scale does not have any sub-dimensions. This scale has been evaluated as a strong measurement tool, with a unidimensional structure.

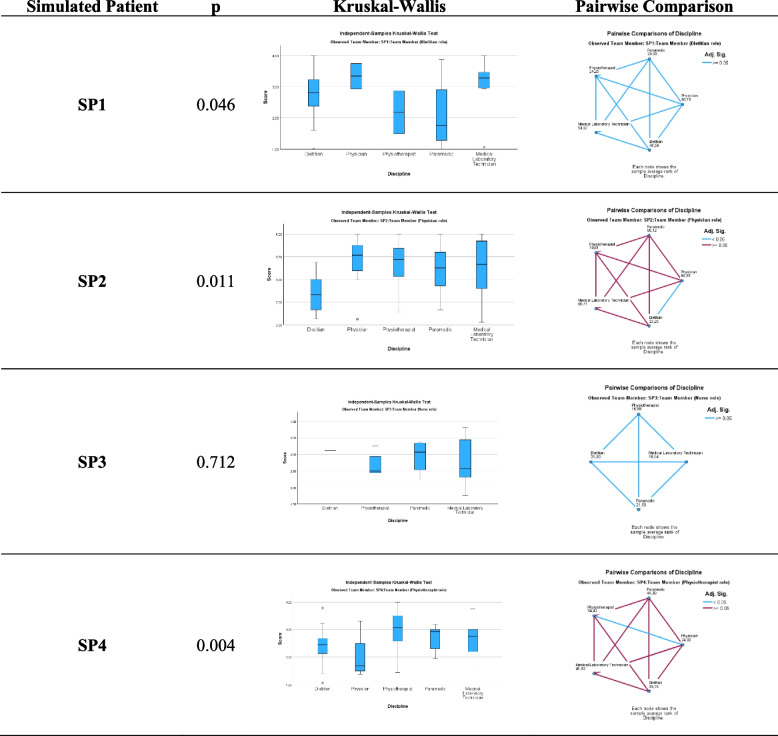

The fact that SPs in different roles are scored by participants from different professions is an important evidence for validity. For this purpose, the scores of participants from different professions were compared for each SP. A statistically significant difference was observed in the results of the interprofessional confirmatory tests for SP1 (p = 0.046). In the evaluation of paired groups, there were no statistically significant differences between the paired groups for all professions. A statistically significant difference was observed in the interprofessional confirmatory tests for SP2 (P = 0.011). In the analysis of the paired groups, it was observed that the difference was due to differences between physicians and dietitians. There was no statistically significant difference in interprofessional confirmatory tests for SP3 (p = 0.712). Analyses of the paired groups showed no differences between the paired groups in all professions. A statistically significant difference was observed in the interprofessional confirmatory tests for SP4 (P = 0.004). In the analysis of the paired groups, it was observed that the statistical difference was due to differences between physicians and dietitians (Table 5).

Table 5.

Analysis of simulated patients by professions

Discussion

There are many adaptation studies in our country on interprofessional identity, education, and collaboration [26, 27]. These studies consisted of language adaptation within a model and an analytical process in which the adapted items were tested in a population [22]. In this study, a Turkish adaptation of the SITAT was developed, and its psychometric properties were evaluated. In addition, Simulation-Based Interprofessional Teamwork of students from five different professions was measured using the SITAT-TR, and the results were compared for exploratory purposes. During the translation process, researchers extensively examined word choices, alternative interpretations, and cultural traditions for all items. To preserve the essence of the original SITAT, only a few changes were made while retaining the basic words and expressions. This study provides evidence of the validity of a Turkish scale developed to assess teamwork in simulation-based scenarios within the context of interprofessional collaboration.

Students from five different professions participated in this study. Content validity indices were calculated for expert opinions in the construct validity analyses. The items were deemed “appropriate” in terms of content validity. This study demonstrated that SITAT-TR provides strong evidence for the validity and reliability of scoring a clinical case scenario with simulated patients. The validity evidence and reliability coefficients were calculated to be higher than the values reported in the literature. In addition to the Turkish adaptation process and content validity analyses, the scores of students representing different professions were compatible with the roles constructed in the scenario.

It is stated that each profession perceives its own profession and other professions differently. In this study, it was shown that there was no difference between professions for some roles, while there was a statistically significant difference in some professions. It was also shown that students from different professions rated scenarios representing different professions and roles from different perspectives. This scoring behavior suggests that there are many confounding factors related to interprofessional identity, collaboration, education, and research. This area is considered as valuable preliminary information, especially for mixed method studies.

The reliability coefficient is a strong evidence for validity in terms of consistent comprehensibility. Cronbach’s alpha for each SP varied. However, the internal consistencies found were all above the statistical cutoff value of 0.70 [24, 25]. The lowest, although sufficient, internal consistency of SITAT-TR was observed. This result is similar to the psychometric properties of the SITAT. The reliability coefficients of the scale were calculated to be high for evidence of reliability. This shows that the items in the Turkish version of the scale can be consistently understood.

The psychometric assessment of simulation-based teamwork is influenced by several confounding factors [15, 16]. Although our study differs in design, it aligns partially with others in terms of “sub-scales, inter-rater variability, and the validation process’ [16]. One limitation is the voluntary nature of student participation; however, the sample size provided adequate statistical stability. Despite the focus on students from a single university and the relatively early stages of participants’ professional roles, this tool shows promise for evaluating team members in simulation-based interprofessional team studies. Furthermore, it offers initial insights into the nature of interprofessional evaluations within teamwork, highlighting that future studies with broader designs could yield more robust psychometric evidence of interprofessional teamwork.

Conclusion

This study successfully adapted the SITAT into Turkish (SITAT-TR) and demonstrated its validity and reliability in assessing interprofessional teamwork within simulation-based scenarios. By rigorously examining the linguistic, cultural, and contextual aspects during translation, the SITAT-TR preserves the integrity of the original scale while providing evidence of its applicability in Turkish contexts. The findings indicate that the SITAT-TR can be a valuable tool for measuring team dynamics among students from various healthcare professions, offering insight into how interprofessional collaboration is perceived and enacted. The tool’s high reliability and robust validity indices support its use in future interprofessional education and research in simulation settings in Turkey. Future studies with diverse designs and larger samples will be instrumental in expanding psychometric evidence and exploring the broader implications of interprofessional collaboration in healthcare.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Süleyman Demirel University for their support in our research.

Declaration of helsinki

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Declaration of AI-assisted technologies

The authors declare that artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technologies, including large language models (LMMs), were not used in this study.

Authors’ contributions

G.K. and MI.BK.; Design - G.K.; Supervision - G.K.; Sources - G.K. and MI.BK.; Data Collection and/or Processing - MI.BK.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - G.K. and MI.BK.; Literature Review - G.K. and MI.BK.; Main Text - G.K. and MI.BK.; Critical Review - G.K. and MI.BK.

Funding

The authors declare that they have no financial support for this study.

Data availability

The authors assumed that the data stored in the data warehouse could be easily accessed by others if the requests were approved.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written permission was obtained from the developer of the scale for the study and the Süleyman Demirel University Ethics Committee of the university where the research was conducted (date: 01.04.2022; no: 108). In the ethics committee approval, a commitment was made that there was no relationship between the data collection process and the educational processes of the participating students. Ethical approval demonstrated that the study adhered to the ethical standards for human participants, including privacy, consent, fairness, and beneficence. This approval confirmed that the research was conducted in accordance with ethical principles, and that the rights of the participants were protected.

Written informed consent was obtained from all students who expressed their opinions within the scope of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Scaria MK. Role of care pathways in interprofessional teamwork. Nurs Stand. 2016;30(52):42–7. 10.7748/ns.2016.e10402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jordan SR, Connors SC, Mastalerz KA. Frontline healthcare workers’ perspectives on interprofessional teamwork during COVID-19. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2022;29: 100550. 10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kishimoto M, Noda M. The difficulties of interprofessional teamwork in diabetes care: a questionnaire survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:333–9. 10.2147/JMDH.S66712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harlak H, Dereboy C, Gemalmaz A. Validation of a Turkish translation of the communication skills attitude scale with Turkish medical students. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2008;21(1):55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vries A, van Dongen J, van Bokhoven M. Sustainable interprofessional teamwork needs a team-friendly healthcare system: experiences from a collaborative Dutch programme. J Interprof Care. 2016;31:1–3. 10.1080/13561820.2016.1237481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb B, Clutton N. Crew Resource Management within interprofessional teamwork development: improving the safety and quality of the patient pathway in health and social care. J Pract Teach Learn. 2010;10(2):4–27. 10.1921/174661110X592647. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turcotte M, Etherington C, Rowe J, et al. Effectiveness of interprofessional teamwork interventions for improving occupational well-being among perioperative healthcare providers: a systematic review. J Interprof Care. 2023;37(6):904–21. 10.1080/13561820.2022.2137116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilcock PM, Janes G, Chambers A. Health care improvement and continuing interprofessional education: continuing interprofessional development to improve patient outcomes. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009;29(2):84–90. 10.1002/chp.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McComb S, Hebdon M. Enhancing patient outcomes in healthcare systems through multidisciplinary teamwork. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(6):669–72. 10.1188/13.CJON.669-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: a review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(Suppl 7):S295-303. 10.4103/2152-7806.139612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogunyemi D, Haltigin C, Vallie S, Ferrari MB. Evolution of an Obstetrics and Gynecology Interprofessional Simulation-Based Education Session for Medical and nursing students. Med (Baltim). 2020;99(43): e22562. 10.1097/md.0000000000022562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Lee W, Kim M, et al. Effectiveness of Simulation-Based Interprofessional Education for Medical and nursing students in South Korea: a Pre-post Survey. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1). 10.1186/s12909-020-02395-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Rachmawati U, Jauhar M, Kusumawardani LH, Rasdiyanah R, Rohana IGAPD. Preparing nursing students for Inter-professional Collaborative Practice through Simulation-Based Inter-professional Education: a systematic review. Jendela Nurs J. 2022;6(1):43–56. 10.31983/jnj.v6i1.8452. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krielen P, Meeuwsen M, Tan E, Schieving J, Ruijs A, Scherpbier N. Interprofessional Simulation of Acute Care for nursing and medical students: interprofessional competencies and transfer to the Workplace. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1). 10.1186/s12909-023-04053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Bismilla Z, Ittersum W, Van Mallory L. Development of a Simulation-based interprofessional. Teamwork Assess Tool. 2019;11(April):168–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daulton B, Romito LM, Weber Z, Burba JL, Ahmed R. Application of a Simulation-based Interprofessional Teamwork Assessment Tool (SITAT) to Individual Student performance in a team-based Simulation. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021;8:238212052110424. 10.1177/23821205211042436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar A, Gilmour CJ, Nestel D, Aldridge R, McLelland G, Wallace EM. Can we teach Core Clinical obstetrics and Gynaecology skills using Low Fidelity Simulation in an interprofessional setting? Aust New Zeal J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54(6):589–92. 10.1111/ajo.12252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martini N, Farmer K, Patil S, et al. Designing and evaluating a virtual patient Simulation—the Journey from Uniprofessional to Interprofessional Learning. Information. 2019;10(1): 28. 10.3390/info10010028. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakobsen RB, Gran SF, Grimsmo B, et al. Examining participant perceptions of an Interprofessional Simulation-Based Trauma Team Training for Medical and nursing students. J Interprof Care. 2017;32(1):80–8. 10.1080/13561820.2017.1376625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Healey A. Developing observational measures of performance in Surgical teams. BMJ Qual Saf. 2004;13(suppl1):i33-40. 10.1136/qhc.13.suppl_1.i33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinde T, Gale T, Anderson I, Roberts M, Sice P. A study to assess the influence of Interprofessional Point of Care Simulation Training on Safety Culture in the operating Theatre Environment of a University Teaching Hospital. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(2):251–3. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1084277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: a clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(2):268–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(24):3186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunnally J. Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunnally J, Bernstrein I. Psychometric Theory. 3rd Editio. McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages. 1994.

- 26.Kolcu MIB, Karabilgin Ozturkcu OS, Kolcu G. Turkish adaptation of the interprofessional attitude scale (IPAS). J Interprof Care. 2022;36(5):684–90. 10.1080/13561820.2021.1971636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolcu G, Başer Kolcu Mİ, Krijnen W, Reinders JJ. Turkish translation and validation of an interprofessional identity measure: EPIS-TR. J Interprof Care. 1–10. 10.1080/13561820.2024.2403012 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors assumed that the data stored in the data warehouse could be easily accessed by others if the requests were approved.