Abstract

Phosphodiesterase 9 (PDE9) degrades selectively the second messenger cGMP, which is an important molecule of dopamine signaling pathways in striatal projection neurons (SPNs). In this study, we assessed the effects of a selective PDE9 inhibitor (PDE9i) in the primate model of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Six macaques with advanced parkinsonism were used in the study. PDE9i was administered as monotherapy and co-administration with L-DOPA at two predetermined doses (suboptimal and threshold s.c. doses of L-Dopa methyl ester plus benserazide) using a controlled blinded protocol to assess motor disability, L-DOPA -induced dyskinesias (LID), and other neurologic drug effects. While PDE9i was ineffective as monotherapy, 2.5 and 5 mg/kg (s.c.) of PDE9i significantly potentiated the antiparkinsonian effects of L-DOPA with a clear prolongation of the “on” state (p < 0.01) induced by either the suboptimal or threshold L-DOPA dose. Co-administration of PDE9i had no interaction with L-DOPA pharmacokinetics. PDE9i did not affect the intensity of LID. These results indicate that cGMP upregulation interacts with dopamine signaling to enhance the L-DOPA reversal of parkinsonian motor disability. Therefore, striatal PDE9 inhibition may be further explored as a strategy to improve motor responses to L-DOPA in PD.

Keywords: PDE9 inhibitor, antiparkinsonian, cyclic nucleotides, L-DOPA induced dyskinesia, Parkinson’s disease, MPTP

Introduction

Dopamine (DA) replacement by L-DOPA , the main symptomatic treatment for Parkinson’s diseases (PD), albeit effective in early-stage disease, with time it gradually fails to fully reverse motor deficits and is complicated with motor response fluctuations and dyskinesias (Nutt, 2000; Obeso et al., 2000). Studies in experimental models and patients have shown that both disease progression and drug exposure play a role in the development of motor complications and the resulting decline in L-DOPA efficacy (Jenner, 2008; Papa et al., 1994). To prolong the effectiveness of L-DOPA , several strategies to reduce drug exposure have been used, including deferring the initiation of L-DOPA , lowering its doses, substituting by DA agonists, or modulating DA actions by targeting interacting non-DAergic systems (Rascol et al., 2015). However, none have resulted in effective control of motor complications. An alternative to these presynaptic/synaptic mechanisms would be targeting the DA signaling downstream from receptor activation, which involves various transduction pathways. An important aspect of this strategy is that particular signaling mechanisms may impact differentially the antiparkinsonian and dyskinesigenic effects of L-DOPA .

The two families of DA receptors, D1R and D2R are segregated in subpopulations of striatal projection neurons (SPNs), the direct and indirect striatal output pathways, respectively (Gerfen et al., 1990). D1R and D2R signaling are mediated by regulation of the second messengers cAMP and cGMP (Giorgi et al., 2008; Seifert et al., 2015). These cyclic nucleotides are key transducers of signaling cascades downstream DA receptor activation. In fact, studies in animal models have shown that striatal cAMP and cGMP levels change following nigrostriatal denervation (Giorgi et al., 2008). cAMP and cGMP are, on the other hand, tightly regulated by specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs). It is thus plausible that the PDE-mediated catabolism of cAMP and cGMP impacts transduction pathways of DA receptor signals. PDE families are distinguished by enzyme properties, expression patterns, and substrate specificity to one or both cyclic nucleotides (Nishi et al., 2008). Most PDEs are expressed in the striatum, and conspicuously in SPNs (Coskran et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2006). Therefore, PDEs posit a unique therapeutic target to modulate selectively striatal dopaminergic signals in PD, and furthermore, inhibitors for different PDEs may have specific effects on particular motor symptoms (Erro et al., 2021).

PDE9 is highly expressed in the striatum as shown by mRNA expression in animal and human brain tissue (Andreeva et al., 2001; Harms et al., 2019; Lakics et al., 2010; van Staveren et al., 2002). PDE9 acts only on cGMP while other striatal PDEs have mixed actions on cyclic nucleotides, or lower affinity for cGMP, or a lower presence in the striatum compared to other loci. Notably, striatal cGMP levels are significantly reduced in DA-denervated rodents (Hossain and Weiner, 1993; Sancesario et al., 2004), and among the PDEs degrading cGMP, PDE9 may play an important role. DA is a major regulator of synthesis and release of nitric oxide (NO) from interneurons, and NO binds to and activates soluble guanylyl cyclase (NO-sGC) in the SPN membrane to form cGMP (Lucas et al., 2000; West and Grace, 2004). This NO-sGC-cGMP pathway induces long-term depression at glutamatergic synapses on direct SPNs (Calabresi et al., 1999). cGMP also plays an important role in protein kinase G- signaling cascades in indirect SPNs, and there is strong evidence for NO-sGC-cGMP changes following DA loss likely affecting both striatal output pathways (Threlfell and Cragg, 2011; West and Tseng, 2011). In rodent models of chronic L-Dopa treatment, the striatal cGMP levels also decrease in correlation with the development of dyskinesias (Giorgi et al., 2008), although variations were observed depending on the phase of dyskinesias (Sancesario et al., 2014). We assessed the behavioral effects of the PDE9 inhibitor FRM-16606 (Forum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) after dopamine depletion in parkinsonian primates. FRM-16606 is a novel, potent and highly selective PDE9 inhibitor (PDE9i), as demonstrated by PDE9A IC50 of 11 nM (>180 fold selectivity over PDE1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 3A, 3B, 4A, 4D, 5A, 7A, 8A and 10). This PDE9i also penetrates the brain, and has >70% bioavailability and adequate half-life for in-vivo use (rodent pharmacokinetic and behavioral data) (McRiner et al., 2015). Our studies showed that PDE9i potentiates specifically the antiparkinsonian action of L-DOPA without directly impacting L-Dopa-induced dyskinesias.

Materials and Methods

Non-human primate model

All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. A total of 6 adult macaques (Macaca Mulatta and Fascicularis, 2 females and 4 males) were used to produce a model of advanced parkinsonism as previously described (Cao et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2015). Briefly, animals received repeated systemic 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) administration, and after stabilization of moderate to severe parkinsonian motor disability (score ≥ 17 in a rating scale ranging from 0 to 39, although the maximum impairment that can be achieved is 25; score ranges from mild to severe impairment are: mild ≤ 12, moderate low 13-16, moderate high 17-20, and severe 20-25) (Cao et al., 2007), they were maintained on oral L-DOPA treatment (carbidopa/levodopa; SINEMET® 25/100). This regimen led to gradual development of L-DOPA -induced dyskinesia (LID). Oral L-DOPA doses were determined individually according to the animal’s sensitivity to produce an acceptable reversal of motor disability (“on” state). The clinical characteristics of each animal are described in Table 1. Animals entered the study after 4 months or more of stable, moderate to severe parkinsonism and chronic L-DOPA treatment (Cao X et al., 2007). Initially, subcutaneous (s.c.) doses of L-DOPA methyl ester plus benserazide (both from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were determined for each animal based on their response to repeated tests of various doses. Four individual s.c. L-DOPA doses were determined (Table 1): optimal (the dose that induced an optimal improvement of motor disability usually ≥75%), sub-optimal (the lower dose that induced 50-75% improvement usually with clear dyskinesias), threshold (the dose that induced mild reversal of parkinsonian symptoms free of dyskinesias), and sub-threshold dose (the highest dose that induced no clear motor changes). Benserazide was always one quarter of the L-DOPA dose. After preliminary tests of L-DOPA plus PDE9i, the optimal and subthreshold doses of L-DOPA were not used in the subsequent systematic tests. The L-DOPA optimal dose showed ceiling effects that could not be changed by adding the inhibitor, and the inhibitor combination with L-DOPA subthreshold dose induced variable results. Thus, the injectable sub-optimal and threshold L-DOPA doses were used in repeated acute tests of co-therapy with the PDE9i in 6 animals.

Table 1:

Subject Demographics and L-Dopa Responses

| Monkey | Age (years) | Gender | MDS OFF | MDS ON | LID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | F | 17 | 1.5 | 13 |

| 2 | 8 | F | 17 | 1.5 | 11.5 |

| 3 | 8 | M | 19 | 3.5 | 10 |

| 4 | 8 | M | 22 | 4.5 | 9 |

| 5 | 9 | M | 23 | 8.5 | 7 |

| 6 | 10 | M | 23.5 | 3.5 | 11 |

Non-human primates (n=6) used in all behavioral studies included males and females between 8- and 10-year-old. MDS OFF = motor disability score at baseline “off’ state; MDS ON = motor disability score at the peak-dose effect of L-dopa in the “on” state. MDS ranges from 0 to 39: 0 = no impairment, 39 = extreme impairment (incompatible with current studies). LID=dyskinesia score at peak-dose effect of L-dopa. LID score ranges from 0 to 27 : 0= no dyskinesia, 27 = severe and/or constant dyskinesia in all body segments. Data are mean of 3 or more behavioral assessments to determine stability of the model. F = female; M=male.

PDE9 inhibitor trials

Two studies of PDE9i efficacy after acute administration were performed to determine (1) the intrinsic effects of PDE9i and (2) the effects of PDE9i on L-DOPA responses; i.e. monotherapy trial and L-DOPA co-administration trial. On test days, drugs were administered subcutaneously (s.c.) to all animals (n=6) followed by behavioral evaluations as described below. All tests were performed after overnight fast and at least 48 hours apart to ensure adequate drug washout. The oral L-DOPA maintenance treatment was withheld on test days. In both trials, PDE9i doses were tested in random order, and each dose was repeated three times (Potts et al., 2015). Data were averaged to yield a mean from three values for each dose in each monkey.

MONOTHERAPY.

PDE9i was dissolved in saline and given s.c. at 0 (control saline injection), 0.4, 0.71, 1.21, 2.1 and 4.1 mg/kg to evaluate potential intrinsic effects on parkinsonian motor disability. Animals were assessed before and after PDE9i administration for up to 3 hours to cover the time period of plasma peak levels of PDE9i. PDE9i doses were chosen to produce drug exposures across a broad range centered on plasma levels for predicted efficacy in preclinical models of antipsychotic activity (rat novel object recognition assay) (McRiner et al., 2015) .

PDE9i - L-DOPA CO-ADMINISTRATION.

Acute single s.c. injections of PDE9i and L-DOPA were co-administered to determine PDE9i efficacy to improve motor responses to L-DOPA (effects on motor disability and LID). Based on results of monotherapy tests, the PDE9i exposure was increased for cotherapy tests using 0, 2.5, 5.0 and 7.5 mg/kg s.c. PDE9i was administered 30 min before L-DOPA methyl ester/benserazide at the preselected s.c. sub-optimal or threshold doses, as determined for each animal. Animals were assessed before PDE9i administration and following L-DOPA administration until the effect wore off.

Behavioral evaluations

Motor evaluations were performed live by trained examiners using a standardized primate motor scale (PMS) for MPTP-treated monkeys (Papa and Chase, 1996). The PMS has 2 parts: motor disability is rated in Part I (which is similar to Part III of the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale used for patients with PD; score range, 0 to 39), and dyskinesias are rated in Part II (score range, 0 to 27), as described previously (Cao et al., 2007). In addition, other common neurologic effects of drugs such as sedation or hyperactivity were assessed with the “Drug Effects on the Nervous System” (DENS) scale (Uthayathas et al., 2013). This scale serves to determine rapid changes in cognitive, extrapyramidal, and autonomic functions after acute drug administration. Animals were assessed by all measures prior to drug treatment (time 0, “off” state), 30 minutes after drug injection, and again every 20 minutes thereafter for the duration of the motor response (“on” state) until scores returned to baseline. Examiners were blinded to the treatment during both monotherapy and cotherapy trials.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetic studies were performed in two awake animals (from the group of animals used in behavioral tests) obtaining blood samples under chair restrain following appropriate chair training. No sedation was used for this procedure. Blood samples were obtained via a vascular access port in the saphenous vein immediately prior to s.c. drug injection, and again at 60, 120, and 180 minutes post-injection(s) for all experiments. Samples were collected following: (1) PDE9i 2.5 mg/kg plus saline (2) PDE9i 5.0 mg/kg plus saline (3) PDE9i 2.5 mg/kg plus sub-optimal L-DOPA methyl ester/benserazide and (4) PDE9i 5.0 mg/kg plus sub-optimal L-DOPA methyl ester/benserazide. Each treatment was repeated once. All samples were processed in duplicates according to standard laboratory procedures, and plasma was stored at −80°C until used for measurements of PDE9i and L-DOPA concentrations using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry.

Data analysis

Results of monotherapy and cotherapy were analyzed comparing the following behavioral parameters: time course of motor disability scores (MDS), total MDS (sum of MDS obtained at all post-injection time points), and DENS scores. In addition, results of cotherapy included comparisons of the duration of the “on” state (reversal of motor disability), which was measured as the time elapsed from beginning of effects at 30 min interval to the last interval with score 50% or lower than baseline (Cao et al., 2007). The following LID parameters were also measured: time course, peak-dose (score at 50 minutes post-injection), and total (sum of LID scores obtained at all post-injection time points) scores. The scoring used in these measures resulted in parametric data (Beck et al., 2018). All data were normalized to control values for analysis of differences produced by PDE9i using one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures followed by Dunnett post-hoc tests when the F value was significant.

Results

PDE9 inhibition potentiates the anti-parkinsonian action of L-DOPA

Monotherapy of PDE9i was evaluated to determine any potential intrinsic motor effects in the parkinsonian setting. PDE9i had no motor effects in this group of severely parkinsonian primates at any of the doses tested (0.12 - 4.1 mg/kg). Baseline MDS in the “off” state did not change at any time point during the 3 h post-injection period. Also important, PDE9i given alone did not induce dyskinesias at any of the doses tested in this group of parkinsonian primates who had already been primed with dopaminergic drug exposure and developed stable LID. No adverse reactions were induced by PDE9i at the tested range of doses. Up to 4.1 mg/kg (s.c.) PDE9i did not produce any sedative effect (no measurable scores on the DENS scale). These results indicate that PDE9i motor effect observed in the L-DOPA cotherapy trials (see below) depended on concomitant dopamine-activated mechanisms, which include both cGMP and cAMP pathways.

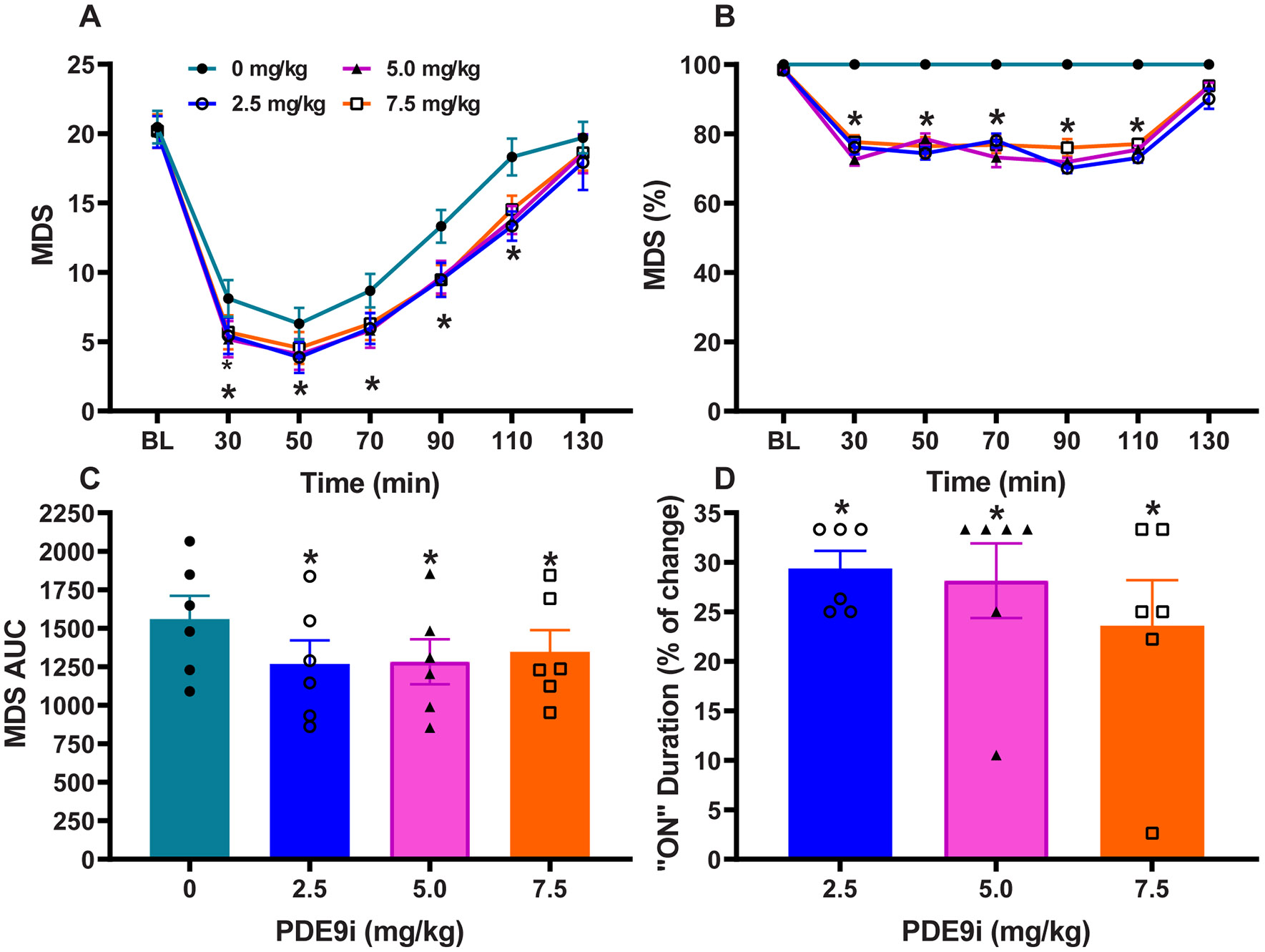

PDE9i 2.5, 5.0 and 7.5 mg/kg (s.c.) augmented the effects of suboptimal and threshold doses of L-DOPA in advanced parkinsonian monkeys. The significant synergistic action of PDE9i was similar at the three tested doses, suggesting that responsiveness is likely limited by the advanced parkinsonism in this primate model. Notably, PDE9i-mediated potentiation of L-DOPA effect was observed in every animal of this group of six severely parkinsonian primates. Four subcutaneous (s.c.) doses of L-DOPA methyl ester plus benserazide were used as determined for each animal according to criteria for subthreshold, threshold, suboptimal and optimal responses (see Fig. 1A, B for response patterns). Analysis of specific motor parameters following cotherapy with the suboptimal L-DOPA dose showed that MDS at all time points including the peak and total (area under curve; AUC) MDS were significantly reduced compared to the control treatment (L-DOPA plus PDE9i 0 mg/kg) (Fig. 2A-C; repeated measures one-way ANOVA: F (3,15) = 15, p<0.05). Yet, the most prominent effect of PDE9i was a pronounced prolongation of the “on” time, extending for 20 to 60 min across animals. On average, this extension represents a 30% increase of the response duration for L-DOPA suboptimal dose, which typically averages 100 min (Repeated measures one-way ANOVA: F (3,15) = 32.7, p < 0.01; Fig. 2D).

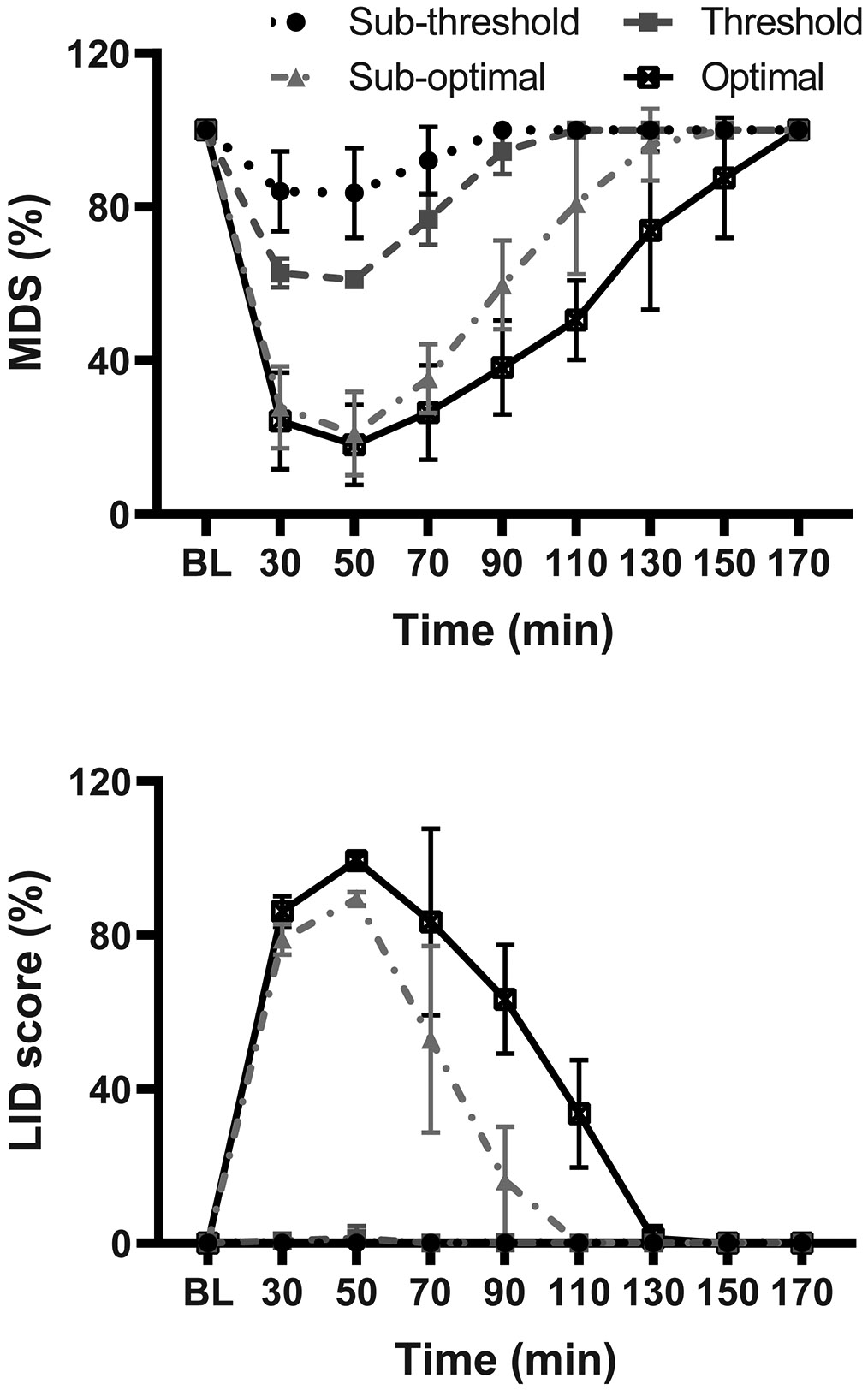

Figure 1. L-DOPA responses.

(A) Motor disability scores (MDS) following optimal, suboptimal, threshold and subthreshold doses of L-DOPA (s.c. injection). (B) L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia (LID, total scores) at the same four doses of L-DOPA . Time courses of responses show scores at 20 min intervals starting at 30 min after the injection (pre-injection “Off” scores are also shown). Data are mean ± SEM.

Figure 2. PD9i coadministration with “suboptimal” L-DOPA dose.

(A) Time course of antiparkinsonian responses to PDE9i at 2.5, 5, and 7.5 mg/kg compared to control treatment (PDE9i 0 mg/kg). Motor disability scores (MDS) were significantly improved by the addition of PDE9i. (B) Normalized MSD scores showing the level of improvement as percentage. (C) Areas under the curve (AUC) of MDS with different doses of PDE9i. AUC were calculated for the whole response. (D) The prolongation of responses (“On” state) by PDE9i co-administration as percentage of the control L-DOPA response (L-DOPA plus PDE9i 0 mg/kg). Data are mean ± SEM. One- or 2-way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett post-hoc test: *p < 0.05 versus control PDE9i 0 mg/kg (vehicle) injection.

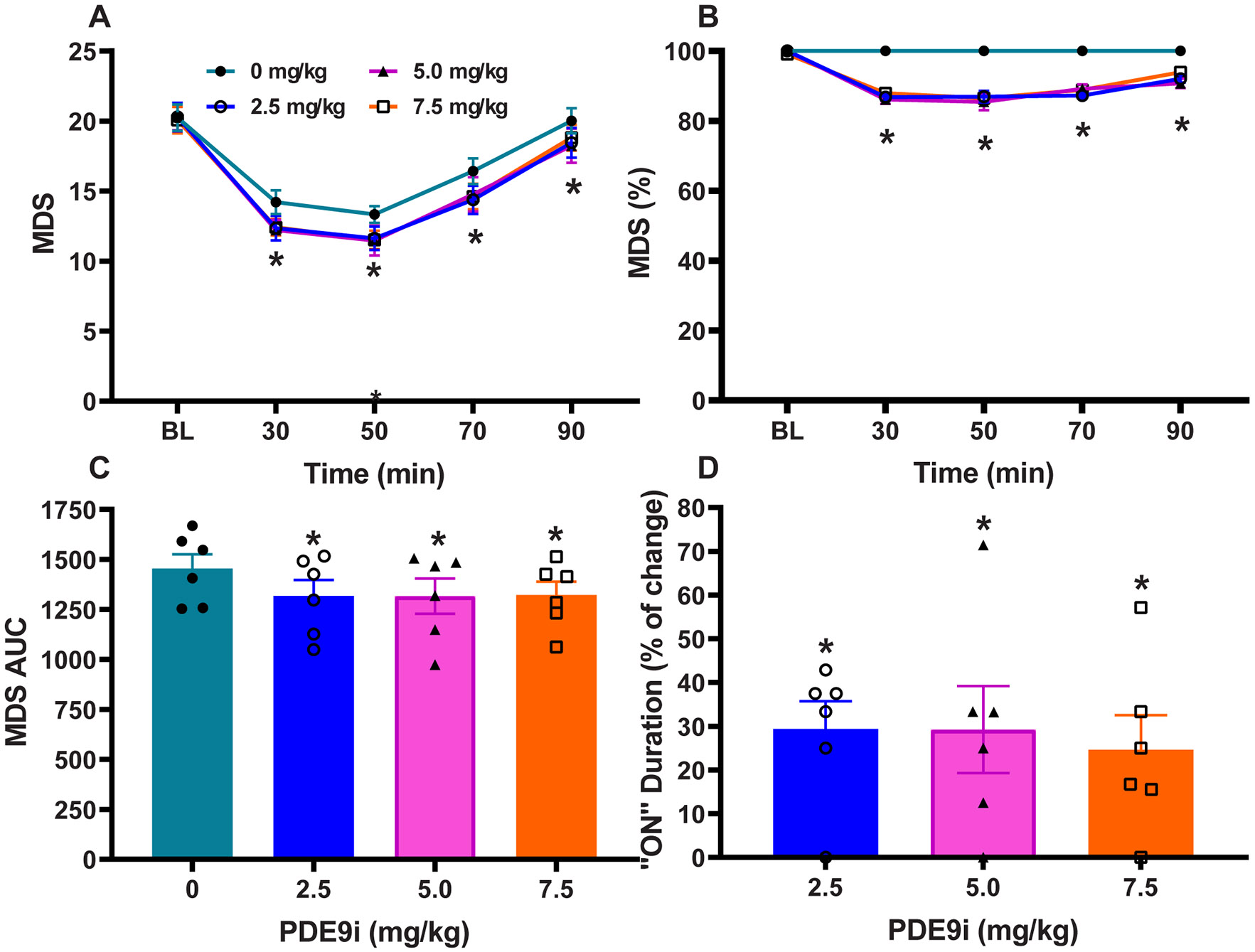

The analysis of specific motor parameters following cotherapy with the threshold L-DOPA dose also showed that MDS at all time points and total (AUC) MDS were significantly reduced (Repeated measures one-way ANOVA: F (3,15) = 14.8, p < 0.01; Fig. 3A-C), and that the “on” time was similarly prolonged (Repeated measures one-way ANOVA: F (3,15) = 8.2, p < 0.05; Fig 3D). The potentiation of a threshold dose of L-DOPA in advanced parkinsonian primates who typically depend on higher L-DOPA levels underscores the strength of PDE9i synergism.

Figure 3. PD9i coadministration with “threshold” L-DOPA dose.

(A) Time course of antiparkinsonian responses to PDE9i at 2.5, 5, and 7.5 mg/kg compared to control treatment (PDE9i 0 mg/kg). Motor disability scores (MDS) were significantly improved by the addition of PDE9i. (B) Normalized MSD scores showing the level of improvement as percentage. (C) Areas under the curve (AUC) of MDS with different doses of PDE9i. AUC were calculated for the whole response. (D) The prolongation of responses (“On” state) by PDE9i co-administration as percentage of the control L-DOPA response (L-DOPA plus PDE9i 0 mg/kg). Data are mean ± SEM. One- or 2-way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett post-hoc test: *p < 0.05 versus control PDE9i 0 mg/kg (vehicle) injection.

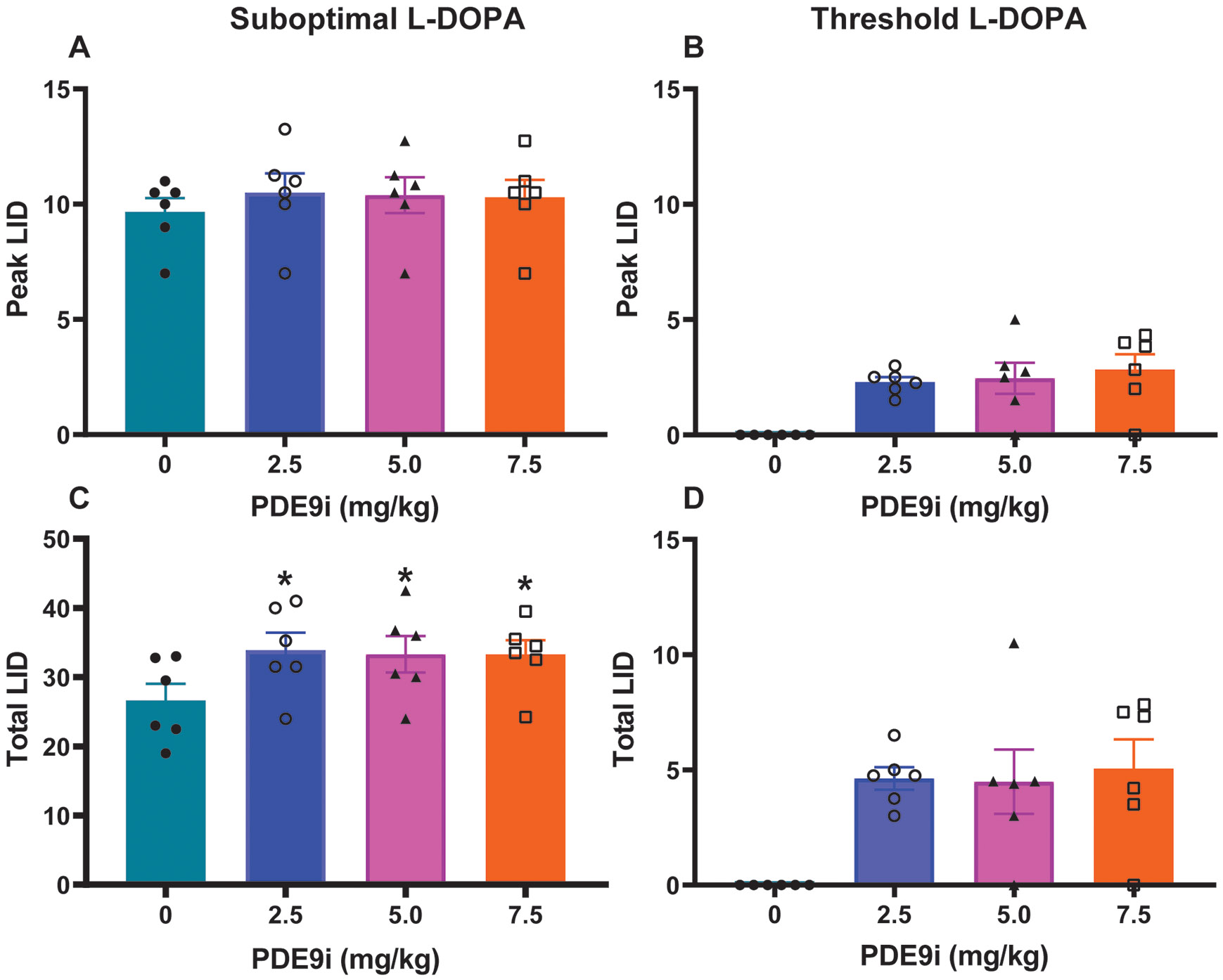

PDE9i at any of the tested doses did not induce significant differences in peak-dose LID in the suboptimal L-DOPA dose trial. As the inhibitor prolonged the L-DOPA -induced “on” state, there were more scoring intervals in the time course of the L-DOPA response when animals had dyskinesias, which led to an increase in total LID scores (Fig. 4A and C). Together, unchanged “peak-dose” LID scores contrasting with the improved “peak-dose” MDS, and increased “total” LID scores congruent with longer action of L-DOPA indicate that PDE9i potentiates predominantly the L-DOPA antiparkinsonian effects over LID. Animals had stable dyskinetic responses to the suboptimal L-DOPA dose, but no consistent LID was present with the threshold dose as established by dose definition (Fig. 1B and D). PDE9i (all doses) cotherapy with the threshold L-DOPA dose induced only occasional, inconsistent LID (Fig. 4B and D). These results in PDE9i cotherapy with the threshold L-DOPA dose also underscore the selective potentiation of L-DOPA antiparkinsonian action.

Figure 4. Effects of PDE9i coadministration with L-DOPA on LID.

(A and B) “Peak” LID following PDE9i coadministration with L-Dopa suboptimal (A) or threshold (B) doses. PDE9i did not induce significant changes in peak LID scores, which were taken at 50 minutes following L-DOPA injection. (C and D) “Total” LID following PDE9i coadministration with L-Dopa suboptimal (C) or threshold (D) doses. Total scores were calculated as the sum of scores from all post-injection time points. PDE9i at all doses combined with suboptimal L-DOPA dose significantly increased total LID (C), although the change was small (nonsignificant differences at each time point or peak dose as seen in A. PDE9i at all doses combined with threshold L-DOPA dose (D) had no significant changes on the inconsistent LID with this L-Dopa dose. Data are mean ± SEM. One- or 2-way ANOVAs followed by Dunnett post-hoc test: *p < 0.05 versus control PDE9i 0 mg/kg (vehicle) injection.

No side effects of PDE9i at the tested dose range were observed in any of these acute trials as measured by the DENS scale. Even though the therapeutic antiparkinsonain action of L-DOPA was significantly increased by PDE9i, no side effects were observed during the repeated injections of cotherapy trials.

Pharmacokinetics

A pharmacokinetic study in two primates was performed to confirm that effects of PDE9i following co-administration with L-DOPA were not due to interaction with the kinetics of either compound. In all treatment conditions, exposure was monitored up to 180 min, which corresponds to the time of behavioral effects. The parameters evaluated were the maximal concentration (Cmax) and clearance as defined by area under the curve (AUC). The two doses of PDE9i (2.5 and 5 mg/kg) administered alone (L-DOPA vehicle, 0 mg/kg) resulted in proportional plasma levels of the compound (Table 2). The half-life of PDE9i was between 2 and 3 hours at the tested dose range. After PDE9i (5 mg/kg) co-administration with L-DOPA (each animal’s respective suboptimal dose), the plasma levels of PDE9i were similar to those measured after PDE9i given alone (Table 2). Also important, the plasma levels of L-DOPA remained unchanged by the addition of PDE9i (5 mg/kg) in comparison to the control treatment, i.e. PDE9i vehicle (0 mg/kg) plus L-DOPA suboptimal dose. Overall, these data indicate that the antiparkinsonian effect of PDE9i is likely due to its targeted enzymatic inhibition and not confounded by changes in L-DOPA pharmacokinetics.

Table 2:

Plasma L-dopa levels with and without PDE9i coadministration.

| Animal | PDE9i mg/kg |

Cmax (ng/mL) |

AUClast (hr*ng/mL) |

L-DOPA | Cmax (ng/mL) |

AUClast (hr*ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 3760 | 25313 | Vehicle | - | - |

| 2 | 5 | 4790 | 26732 | Vehicle | - | - |

| 1 | 2.5 | 2925 | 19607 | Vehicle | - | - |

| 2 | 2.5 | 2735 | 15109 | Vehicle | - | - |

| 1 | Vehicle | - | - | Suboptimal | 79.2 | 329 |

| 2 | Vehicle | - | - | Suboptimal | 86.5 | 340 |

| 1 | 5 | 3770 | 22803 | Suboptimal | 84.9 | 333 |

| 2 | 5 | 4875 | 31478 | Suboptimal | 93.3 | 294 |

Blood samples were collected from 2 awake animals at 0, 60, 120, and 180 minutes following injection of either L-dopa methyl ester plus vehicle or L-dopa plus PDE9i (2.5 and 5 mg/kg). Each treatment was repeated once for duplicate sampling. Data represent mean concentrations.

Discussion

The present results showed that PDE9i significantly potentiated the antiparkinsonian action of a range of L-DOPA doses (from threshold to suboptimal) in the primate model of advanced PD. MDS were lower throughout the entire L-DOPA response, which resulted in marked prolongation of the “on” state. The inhibitor effect on the right portion of the time/response curve, when L-DOPA plasma levels decline, underscore the potential of this therapeutic to help reducing the L-DOPA requirements. PDE9i effect was predominantly on the antiparkinsonian component of the L-DOPA response, as LID increases were mild and inconsistent in co-therapy tests in these animals with severe parkinsonism and reproducible LID. In fact, PDE9i did not change the peak-dose scores of LID following L-DOPA suboptimal dose, and thus, the slight increase in “total” LID scores reflects an extension of the “on” state. Of note, the peak-dose LID was not at a ceiling level because scores could increase with a higher dose of L-DOPA (optimal L-DOPA dose given alone, Fig. 1B). These results were not related to pharmacokinetic interactions between PDE9i and L-DOPA. Therefore, PDE9i has a selective synergism with L-DOPA-mediated antiparkinsonian action, and thereby provides a powerful tool to optimize treatment in various scenarios, such as poor motor responses, resistant symptoms, and response fluctuations. Inhibition of PDE9 may also be a useful strategy to lower L-DOPA doses and reduce LID while maintaining adequate improvement of motor deficits.

PDE9i effects are mediated by its specific action inactivating the enzymatic hydrolysis of cGMP, and thus elevating cGMP levels. The PDE families that selectively catabolize cGMP are PDE 5, 6, and 9, but their brain distribution varies. PDE9 is highly expressed in the striatum while PDE 5 and 6 have very low striatal expression (Reyes-Irisarri et al., 2007; Van Staveren et al., 2003). Regulation of various PDE families is known to produce motor effects in intact and dopamine-depleted animals (Reed et al., 2002; Sancesario et al., 2004; Sharma and Deshmukh, 2015; Sharma et al., 2013). Non-selective PDE9i (e.g. zaprinast, which has moderate affinity for PDE 5 and 6, but weak for 9, 10, and 11) have shown reduction of L-DOPA-induced abnormal involuntary movements in rodents (Giorgi et al., 2008; Picconi et al., 2011). The present study of a selective PDE9i shows potentiation of L-DOPA-induced antiparkinsonian effects, which may indicate differences not only in substrate affinity (selective for PDE9) but also in the site of action, i.e: striatal versus extra-striatal regions. Notably, the higher striatal expression of PDE9 compared with other basal ganglia regions may account for a predominant striatal action and the observed effects after systemic PDE9i administration impacting L-Dopa responses (Andreeva et al., 2001; Harms et al., 2019; Lakics et al., 2010; van Staveren et al., 2002).

PDE9i leads to an increase of cGMP and its signals in both SPN subpopulations since the enzyme seems to be expressed across SPNs. This could be synergistic with DA action on direct D1R-expressing SPNs, which is congruent with DA stimulation of the interneurons generating NO also via D1R/D5R (Prast and Philippu, 2001; West et al., 2002). In contrast, PDE9i that raises cGMP levels would be antagonistic to DA action on indirect D2R-expressing SPNs that is thought to inhibit the synthesis of the nucleotide. However, DA modulation of cGMP in indirect SPNs is less clear, as these neurons are also influenced by the NO released from interneurons expressing D1R. It is also possible that PDEs undergo differential regulations in SPN subsets after DA loss, but such data are lacking. Cyclic nucleotides changes have been reported inconsistently in animal models and patients with PD (Sharma et al., 2013), but an upregulation of cGMP signaling via NOS-NO-sGC pathway would lead to increased excitability of SPNs to corticostriatal glutamatergic transmission (Padovan-Neto et al., 2015; Threlfell and West, 2013; West and Grace, 2004). In addition, DA depletion leads to differences in the excitability changes of direct and indirect SPNs, which may underly the loss of balance of DA actions and the potential benefit of opposite PDE9i actions on DA signals in each cell subset (Fieblinger et al., 2014). Clearly, more work is necessary to explain the SPN hyperexcitability in PD (Beck et al., 2018), particularly regarding the net cGMP changes in each SPN subpopulation considering both its formation via NO-sCG and its degradation via PDEs.

The injection of PDE9i into the striatum demonstrated a direct impact on the SPN activitiy (unpublished observations in single cell recordings in NHPs). Similar to the dual response induced by DA in direct and indirect SPNs, PDE9i also induces firing increases or decreases across the recorded SPNs, as opposed of no effect of vehicle (artificial CSF) injection. In such recordings without identification of SPN subsets, the timing of PDE9i injection was adequate to assess the effects of blocking PDE9 in the SPN, as demonstrated through drug diffusion simulations (Singh et al., 2018). As a significant level of endogenous dopamine was present in the mildly parkinsonian condition of the recordings, the firing increases or decreases across SPNs suggest a variable interaction between the PDE9i-induced cGMP rise and dopamine signaling. Data may seem to be in conflict with the premise that increased cGMP levels would be antagonistic to DA action on indirect SPNs; however, this and other open questions regarding PDE9i-mediated mechanisms cannot be addressed with the present data. In addition, the relative roles of cGMP and cAMP signals in the excitability of direct and indirect SPNs are unclear, and this may be a key point in the effects of PDE9i. Notably, inhibition of PDE10A has shown no beneficial effects on MDS, but significant antidyskinetic effects in parkinsonian primates (Beck et al., 2018). Both PDE9 and 10A are highly expressed in the striatum, but PDE10A has similar affinities for cAMP and cGMP, while PDE9 is highly selective for cGMP (Fujishige et al., 1999; Hutson et al., 2011; Kleiman et al., 2012; Loughney et al., 1999). Altogether data suggest that regulation of cAMP and cGMP signaling by PDEs differentially impact SPN responses to DAergic stimulation in the parkinsonian setting.

Although PDE9i cotherapy potentiated L-DOPA effects on MDS, as monotherapy the inhibitor had no intrinsic antiparkinsonian effects. An important point is the use of moderate to severely parkinsonian monkeys, and thus, intrinsic effects of PDE9i in milder conditions with more residual DA innervation (likely equivalent to earlier stages of human disease) is still a possibility. In addition, we used animals that had been primed with dopaminergic stimulation, which may induce changes in DA sensitivity as well as other non-DA systems (Morelli et al., 1996). Finally, the present study was designed to determine if the selective inhibition of PDE9 had motor effects in the parkinsonian setting, and to this end the study was limited to acute testing. PDE9i effects over chronic administration remain to be tested, but the significant number of PDE9i injections (cotherapy with two doses of L-DOPA ) did not lead to development of tolerance or other changes in efficacy, or side effects. Critically, the inclusive experimental design from monotherapy to multiple aspects of L-DOPA coadministration in a primate model provided data that support the potential of PDE9i for the therapy of PD.

In summary, results of this study show that PDE9i enhances of anti-parkinsonian responses to L-DOPA in primates. PDE9i given with L-DOPA is also safe and well tolerated following repeated acute administration. These results suggest that PDE9i may be a therapeutic strategy to extend and smooth responses to L-DOPA , as well as facilitating a reduction of the L-DOPA dose to control its motor complications. These results represent a unique opportunity to enhance dopaminergic signaling and optimize the antiparkinsonian effects of L-DOPA through other signaling regulators, such as the phosphodiesterases. Therefore, the present study supports further development of selective PDE9 inhibitors for the treatment of PD.

HIGHLIGHTS.

A selective PDE9 inhibitor potentiates the antiparkinsonian effects of L-DOPA by prolonging response duration.

The effect of PDE9 inhibition on motor responses of L-Dopa is not complicated by augmenting dyskinesias.

Effects of PDE9 inhibition that lead to increased levels of cGMP suggest a distinct cGMP interaction with dopamine signaling.

In addition to therapeutic implications, these data challenge our understanding of cGMP-mediated dopamine signaling.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH Grants NS045962, NS073994, NS110416, NS125502, and OD011132 (S.M.P.). We thank the veterinary department of the Yerkes National Primate Research Center for assistance in the maintenance and care of the primates used to model moderate to advanced PD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

Drs. Masilamoni, Sinon, Kochoian, Singh, and Papa declare no competing financial interest. Drs. McRiner and Leventhal have competing financial interest in the work described because of their affiliation with FORUM, Pharmaceuticals Inc.

References

- Andreeva SG, Dikkes P, Epstein PM, Rosenberg PA, 2001. Expression of cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase 9A mRNA in the rat brain. J Neurosci 21, 9068–9076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck G, Singh A, Papa SM, 2018. Dysregulation of striatal projection neurons in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 125, 449–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabresi P, Gubellini P, Centonze D, Sancesario G, Morello M, Giorgi M, Pisani A, Bernardi G, 1999. A critical role of the nitric oxide/cGMP pathway in corticostriatal long-term depression. J Neurosci 19, 2489–2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Liang L, Hadcock JR, Iredale PA, Griffith DA, Menniti FS, Factor S, Greenamyre JT, Papa SM, 2007. Blockade of cannabinoid type 1 receptors augments the antiparkinsonian action of levodopa without affecting dyskinesias in 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-treated rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 323, 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coskran TM, Morton D, Menniti FS, Adamowicz WO, Kleiman RJ, Ryan AM, Strick CA, Schmidt CJ, Stephenson DT, 2006. Immunohistochemical localization of phosphodiesterase 10A in multiple mammalian species. J Histochem Cytochem 54, 1205–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erro R, Mencacci NE, Bhatia KP, 2021. The Emerging Role of Phosphodiesterases in Movement Disorders. Mov Disord 36, 2225–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fieblinger T, Graves SM, Sebel LE, Alcacer C, Plotkin JL, Gertler TS, Chan CS, Heiman M, Greengard P, Cenci MA, Surmeier DJ, 2014. Cell type-specific plasticity of striatal projection neurons in parkinsonism and L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Nat Commun 5, 5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishige K, Kotera J, Michibata H, Yuasa K, Takebayashi S, Okumura K, Omori K, 1999. Cloning and characterization of a novel human phosphodiesterase that hydrolyzes both cAMP and cGMP (PDE10A). J Biol Chem 274, 18438–18445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerfen CR, Engber TM, Mahan LC, Susel Z, Chase TN, Monsma FJ Jr., Sibley DR, 1990. D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-regulated gene expression of striatonigral and striatopallidal neurons. Science 250, 1429–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi M, D'Angelo V, Esposito Z, Nuccetelli V, Sorge R, Martorana A, Stefani A, Bernardi G, Sancesario G, 2008. Lowered cAMP and cGMP signalling in the brain during levodopa-induced dyskinesias in hemiparkinsonian rats: new aspects in the pathogenetic mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci 28, 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms JF, Menniti FS, Schmidt CJ, 2019. Phosphodiesterase 9A in Brain Regulates cGMP Signaling Independent of Nitric-Oxide. Front Neurosci 13, 837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain MA, Weiner N, 1993. Dopaminergic functional supersensitivity: effects of chronic L-dopa and carbidopa treatment in an animal model of Parkinson's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267, 1105–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson PH, Finger EN, Magliaro BC, Smith SM, Converso A, Sanderson PE, Mullins D, Hyde LA, Eschle BK, Turnbull Z, Sloan H, Guzzi M, Zhang X, Wang A, Rindgen D, Mazzola R, Vivian JA, Eddins D, Uslaner JM, Bednar R, Gambone C, Le-Mair W, Marino MJ, Sachs N, Xu G, Parmentier-Batteur S, 2011. The selective phosphodiesterase 9 (PDE9) inhibitor PF-04447943 (6-[(3S,4S)-4-methyl-1-(pyrimidin-2-ylmethyl)pyrrolidin-3-yl]-1-(tetrahydro-2H-py ran-4-yl)-1,5-dihydro-4H-pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidin-4-one) enhances synaptic plasticity and cognitive function in rodents. Neuropharmacology 61, 665–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenner P., 2008. Molecular mechanisms of L-DOPA-induced dyskinesia. Nat Rev Neurosci 9, 665–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman RJ, Chapin DS, Christoffersen C, Freeman J, Fonseca KR, Geoghegan KF, Grimwood S, Guanowsky V, Hajos M, Harms JF, Helal CJ, Hoffmann WE, Kocan GP, Majchrzak MJ, McGinnis D, McLean S, Menniti FS, Nelson F, Roof R, Schmidt AW, Seymour PA, Stephenson DT, Tingley FD, Vanase-Frawley M, Verhoest PR, Schmidt CJ, 2012. Phosphodiesterase 9A regulates central cGMP and modulates responses to cholinergic and monoaminergic perturbation in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341, 396–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakics V, Karran EH, Boess FG, 2010. Quantitative comparison of phosphodiesterase mRNA distribution in human brain and peripheral tissues. Neuropharmacology 59, 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loughney K, Snyder PB, Uher L, Rosman GJ, Ferguson K, Florio VA, 1999. Isolation and characterization of PDE10A, a novel human 3', 5'-cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Gene 234, 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas KA, Pitari GM, Kazerounian S, Ruiz-Stewart I, Park J, Schulz S, Chepenik KP, Waldman SA, 2000. Guanylyl cyclases and signaling by cyclic GMP. Pharmacol Rev 52, 375–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRiner AJ, Burnett DA, Bursavich MG, Kapadnis S, Leventhal L, Nolan S, Ripka AS, Shapiro G, Tang C, Wen M, Koenig G, 2015. Identification of imidazotriazinone anlogs as potent and selective PDE9 inhibitors demonstrating good drug-like properties and cognitive enhancement in a rodent cognition model’. 250th National Meeting of the American Chemical Society, Boston, MA, US (16th – 20th August, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- Morelli M, Fenu S, Carta A, Di Chiara G, 1996. Effect of MK 801 on priming of D1-dependent contralateral turning and its relationship to c-fos expression in the rat caudate-putamen. Behav Brain Res 79, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishi A, Kuroiwa M, Miller DB, O'Callaghan JP, Bateup HS, Shuto T, Sotogaku N, Fukuda T, Heintz N, Greengard P, Snyder GL, 2008. Distinct roles of PDE4 and PDE10A in the regulation of cAMP/PKA signaling in the striatum. J Neurosci 28, 10460–10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nutt JG, 2000. Clinical pharmacology of levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Ann Neurol 47, S160–164; discussion S164–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeso JA, Olanow CW, Nutt JG, 2000. Levodopa motor complications in Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci 23, S2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padovan-Neto FE, Sammut S, Chakroborty S, Dec AM, Threlfell S, Campbell PW, Mudrakola V, Harms JF, Schmidt CJ, West AR, 2015. Facilitation of corticostriatal transmission following pharmacological inhibition of striatal phosphodiesterase 10A: role of nitric oxide-soluble guanylyl cyclase-cGMP signaling pathways. J Neurosci 35, 5781–5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa SM, Chase TN, 1996. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias improved by a glutamate antagonist in Parkinsonian monkeys. Ann Neurol 39, 574–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papa SM, Engber TM, Kask AM, Chase TN, 1994. Motor fluctuations in levodopa treated parkinsonian rats: relation to lesion extent and treatment duration. Brain Res 662, 69–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picconi B, Bagetta V, Ghiglieri V, Paille V, Di Filippo M, Pendolino V, Tozzi A, Giampa C, Fusco FR, Sgobio C, Calabresi P, 2011. Inhibition of phosphodiesterases rescues striatal long-term depression and reduces levodopa-induced dyskinesia. Brain 134, 375–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts LF, Park ES, Woo JM, Dyavar Shetty BL, Singh A, Braithwaite SP, Voronkov M, Papa SM, Mouradian MM, 2015. Dual kappa-agonist/mu-antagonist opioid receptor modulation reduces levodopa-induced dyskinesia and corrects dysregulated striatal changes in the nonhuman primate model of Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 77, 930–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prast H, Philippu A, 2001. Nitric oxide as modulator of neuronal function. Prog Neurobiol 64, 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rascol O, Perez-Lloret S, Ferreira JJ, 2015. New treatments for levodopa-induced motor complications. Mov Disord 30, 1451–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed TM, Repaske DR, Snyder GL, Greengard P, Vorhees CV, 2002. Phosphodiesterase 1B knock-out mice exhibit exaggerated locomotor hyperactivity and DARPP-32 phosphorylation in response to dopamine agonists and display impaired spatial learning. J Neurosci 22, 5188–5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Irisarri E, Markerink-Van Ittersum M, Mengod G, de Vente J, 2007. Expression of the cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases 2 and 9 in normal and Alzheimer's disease human brains. Eur J Neurosci 25, 3332–3338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancesario G, Giorgi M, D'Angelo V, Modica A, Martorana A, Morello M, Bengtson CP, Bernardi G, 2004. Down-regulation of nitrergic transmission in the rat striatum after chronic nigrostriatal deafferentation. Eur J Neurosci 20, 989–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sancesario G, Morrone LA, D'Angelo V, Castelli V, Ferrazzoli D, Sica F, Martorana A, Sorge R, Cavaliere F, Bernardi G, Giorgi M, 2014. Levodopa-induced dyskinesias are associated with transient down-regulation of cAMP and cGMP in the caudate-putamen of hemiparkinsonian rats: reduced synthesis or increased catabolism? Neurochem Int 79, 44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R, Schneider EH, Bahre H, 2015. From canonical to non-canonical cyclic nucleotides as second messengers: pharmacological implications. Pharmacol Ther 148, 154–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Deshmukh R, 2015. Vinpocetine attenuates MPTP-induced motor deficit and biochemical abnormalities in Wistar rats. Neuroscience 286, 393–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kumar K, Deshmukh R, Sharma PL, 2013. Phosphodiesterases: Regulators of cyclic nucleotide signals and novel molecular target for movement disorders. Eur J Pharmacol 714, 486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Jenkins MA, Burke KJ Jr., Beck G, Jenkins A, Scimemi A, Traynelis SF, Papa SM, 2018. Glutamatergic Tuning of Hyperactive Striatal Projection Neurons Controls the Motor Response to Dopamine Replacement in Parkinsonian Primates. Cell Rep 22, 941–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Liang L, Kaneoke Y, Cao X, Papa SM, 2015. Dopamine regulates distinctively the activity patterns of striatal output neurons in advanced parkinsonian primates. J Neurophysiol 113, 1533–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, Cragg SJ, 2011. Dopamine signaling in dorsal versus ventral striatum: the dynamic role of cholinergic interneurons. Front Syst Neurosci 5, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfell S, West AR, 2013. Review: Modulation of striatal neuron activity by cyclic nucleotide signaling and phosphodiesterase inhibition. Basal Ganglia 3, 137–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthayathas S, Shaffer CL, Menniti FS, Schmidt CJ, Papa SM, 2013. Assessment of adverse effects of neurotropic drugs in monkeys with the "drug effects on the nervous system" (DENS) scale. J Neurosci Methods 215, 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Staveren WC, Glick J, Markerink-van Ittersum M, Shimizu M, Beavo JA, Steinbusch HW, de Vente J, 2002. Cloning and localization of the cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase type 9 in the rat brain. J Neurocytol 31, 729–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Staveren WC, Steinbusch HW, Markerink-Van Ittersum M, Repaske DR, Goy MF, Kotera J, Omori K, Beavo JA, De Vente J, 2003. mRNA expression patterns of the cGMP-hydrolyzing phosphodiesterases types 2, 5, and 9 during development of the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 467, 566–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AR, Galloway MP, Grace AA, 2002. Regulation of striatal dopamine neurotransmission by nitric oxide: effector pathways and signaling mechanisms. Synapse 44, 227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AR, Grace AA, 2004. The nitric oxide-guanylyl cyclase signaling pathway modulates membrane activity States and electrophysiological properties of striatal medium spiny neurons recorded in vivo. J Neurosci 24, 1924–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AR, Tseng KY, 2011. Nitric Oxide-Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase-Cyclic GMP Signaling in the Striatum: New Targets for the Treatment of Parkinson's Disease? Front Syst Neurosci 5, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Adamowicz WO, Eldred WD, Jakowski AB, Kleiman RJ, Morton DG, Stephenson DT, Strick CA, Williams RD, Menniti FS, 2006. Cellular and subcellular localization of PDE10A, a striatum-enriched phosphodiesterase. Neuroscience 139, 597–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]