Abstract

This dataset originates from TeensLab, a consortium of Spanish Universities dedicated to behavioral research involving Spanish teenagers. The dataset contains data from 33 distinct educational institutions across Spain, accounting for a total of 5,890 students aged 10 to 23 (M = 14.10, SD = 1.94), representing various educational levels such as primary school, secondary school, sixth form and vocational training. The main dimensions covered in this dataset include (i) economic preferences, (ii) cognitive abilities and (iii) strategic thinking. Additionally, a range of supplementary variables is included alongside socio-demographic factors, capturing data on aspects like physical appearance, mood and expectations, among others.

Subject terms: Economics, Decision making, Education

Background & Summary

Adolescence is a stage of major physical, psychological, emotional and social development, representing a crucial period in human life. The experiences, skills and habits that are accumulated during this stage have a permanent impact on human life. Therefore, understanding the behavior of individuals throughout this period is essential to supporting their development and ensuring their success in adulthood. Indeed, there is great interest in underlying motivations of adolescent behaviors for the design of public policies1.

It is widely recognized that individual preferences and cognitive abilities are important determinants of real-life decision-making of adults in strategic and non-strategic situations2–6. To understand and predict adult behavior, it is essential to comprehend how their attitudes toward risk, social and time preferences, cognitive abilities, creativity, and other traits evolve, particularly in their younger years7–18.

The dataset presented here contributes to the literature on adolescence by eliciting-using the tools of experimental economics-rich information on economic preferences, cognitive abilities, strategic thinking behavior and other information from a large set of adolescents in Spain. We conducted lab-in-the-field experiments in 33 different educational centers, accounting for a total of 5,890 observations of Spanish students. The centers belong to 19 different locations. A total of 20 of them are public and the rest are semi-private. In addition to socio-demographic details and other variables related to the individual, the data includes several sets of variables: economic preferences, cognitive abilities, strategic thinking and other additional measures.

Our dataset can contribute to future research on adolescents in at least two ways. First, it allows researchers to study adolescent decision-making and understand developmental causes of anomalous behavior. Second, it provides information on economic preferences, cognitive skills and other individual information, enabling exploring the extent to which these variables are sensitive to the class and school environment.

This dataset has been previously employed in the following studies: (i) An analysis of the relevance of monetary incentives, experimental tools and protocols to collect data in schools19, (ii) a study of the impact of visual aids in experimental lottery tasks to reduce inconsistency among adolescents20, (iii) the development of time and risk preferences throughout the adolescence21, (iv) the dynamics of social preferences among girls and boys22 and (v) the use of coordination devices among adolescents23. These studies as well as information about the TeensLab can be found on our website (https://loyolabehlab.org/teenslab/).

Methods

Data acquisition

In conducting research with minors, adherence to legal frameworks and ethical guidelines is essential. Spanish law governing the protection of personal data of minors allows for data processing based on the consent of children over 14 years of age (Art. 724). Although our study included participants over 14, we obtained informed parental consent through a parental council that had approved the study, enabling the integration of the study into the school curriculum. This consent authorized participation and the anonymous sharing and use of data within the scientific community. In this way, parental consent is collected by the center itself at the beginning of the scholar-year where they present the activities planned, including this experiment. This strategy not only simplified the process but also facilitated scalability.

Participants were informed about the purpose of data processing, the confidentiality of their responses, and the legal framework governing their data. Teachers managed participant lists and assigned identification numbers to ensure confidentiality. All responses were recorded anonymously.

Informed consent was additionally obtained from all participants on the initial screen of the experiment. This mandatory screen provided essential information in compliance with data protection regulations. Table 1 presents a translation of this information, which includes the identity of the data controller and a description of the rights participants may exercise.

Table 1.

Initial screen of the experiment.

| Welcome! |

| Before we begin, we want to thank you for your participation and inform you that all your responses will be kept confidential. This is a research project conducted by the Loyola Behavioral Lab, funded by the Andalusian Agency for International Development Cooperation, the Regional Government of Andalusia, and the Ministry of Science and Innovation. |

| As you will see, the instructions are very simple. It is very important that you pay close attention and fully understand the instructions. |

| If you require additional information, you can contact the research staff at Loyola University Andalusia involved in the project: Pablo Brañas Garza, Professor of Behavioral Economics, 957 22 21 00, pablob@uloyola.es. All personal data obtained in this study is confidential and will be processed in accordance with the Organic Law on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights 3/2018. |

| CLICK ON THE CHECKBOX TO ACCEPT AND GO TO THE FOLLOWING SCREEN |

I consent to the processing of my data obtained in this study in accordance with the Spanish Organic Law on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights 3/2018. I consent to the processing of my data obtained in this study in accordance with the Spanish Organic Law on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights 3/2018. |

Our experiment was approved by the Ethical Committee of Universidad Loyola Andalucía (No. 20190318, 20200709 and 20230301) Furthermore, for 10-year-olds, it was also approved by the Bioethics Commission of the University of Barcelona (No. IRB00003099).

To mitigate issues related to non-standard samples and minimize missing data, we simplified response formats, predominantly using multiple-choice questions rather than open-ended ones. The design of the software required that participants could not skip questions. However, for potentially sensitive topics, they were allowed to choose the option “I would prefer not to answer”.

The participant pool was recruited through agreements with school headmasters, who agreed to integrate the experiment into their pedagogical curriculum and to carry it out as a classroom activity. Consequently, we achieved a high level of participation19. The experiments were conducted on-site at schools using an online platform named Social Analysis and Network Data (SAND; https://sand.kampal.com), enhancing data privacy control. This platform allows students to navigate and complete the experimental questionnaire, which is divided into several sections, on their devices (tablets, computers, or smartphones).

The questionnaire was administered entirely in Spanish. Due to the restrictive school policies on experiments involving real money, we used hypothetical rewards. However, it has been documented that the behavior of adolescents does not differ between incentivized and hypothetical payment schemes at least for risk and time preferences, suggesting the reliability of the findings25–31.

Measurements

Table 2 contains all the tasks included in the study. Apart from basic information regarding the school (province, city and public/semi-private) and the class (stage, grade, group, class size), our dataset includes individual-level measurements for the following three behavioral dimensions:

Economic preferences: Time discounting, involving choices between immediate and delayed rewards (patience)19,32; risk preferences, assessed through decisions involving probabilistic outcomes (prudence)19,20; social preferences, measured via resource allocation tasks (egalitarianism, altruism, spitefulness)33–35; and honesty, evaluated through opportunities to misreport outcomes36.

Cognitive abilities: Cognitive reflection, overriding intuitive responses19,37; financial abilities, solving simple financial calculations19; probability knowledge and accuracy, measured via decisions in probabilistic scenarios38 and creativity, generating multiple original ideas using a single object39.

Strategic thinking: Subjects choices and expectations in strategic environments (games)22.

Table 2.

Experiment summary by dimensions and observations.

| Dimension | Variable sets | Task | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic preferences | Time discount | The Truck task | 5684 |

| Risk preferences | The Gumball Machine task | 5592 | |

| Social preferences | Dictator game (3 decisions) | 4479 | |

| Dictator game (6 decisions) | 857 | ||

| Honesty | Pictures game | 2700 | |

| Numbers game | 852 | ||

| Cognitive abilities | Cognitive Reflection Test | CRT | 5655 |

| Finance abilities | Financial tasks | 5560 | |

| Probabilistic knowledge | Test of probability knowledge | 5426 | |

| Creativity | The Brick task | 4600 | |

| The Rope task | 508 | ||

| Strategic thinking | Strategic games | Dominant strategies: Uno Cards | 2697 |

| Cournot-Nash games: Piggy bank | 860 | ||

| Coordination games | 1793 | ||

| General information of the subject | Socio-demographic | Age, gender, family variables | 5890 |

| GPA | Self-reported As and Bs | 5890 | |

| Physical appearance | Self-reported height, weight and appearance by Stunkard figure scale | 2627 | |

| Mood | Short version of Kidscreen | 5383 | |

| Additional instruments | Expectations | Career Ambitions and Global Exploration | 1017 |

| Self-assessed math abilities | How good are you/How much you like | 2857 | |

| Time preferences | Compound staircase version | 2450 | |

| Perception of time | Sentence-completion task | 1484 |

Note: In this study, multiple tasks were used in some dimensions to assess the same concepts. Due to adjustments made throughout the experimental process, it is possible to find different versions of tasks. In particular, for the assessment of social preferences, both a 3-question and a 6-question dictator game version have been used. Similarly, for the measurement of honesty, the picture difference task was predominantly used, occasionally substituted by the numerical difference task. For the evaluation of creativity, the brick task has been the main measure, although the rope task has been used alternatively in some sessions. In addition, for strategic thinking, the Uno game was used initially, followed by the piggy bank game and finishing with coordination games. Detailed information can be found in the Repository.

We also collected information regarding the participant’s family background and outcomes in school:

Socio-demographics: Age, gender, self-reported income, migrant status and family composition (number of siblings and her ranking).

GPA: The self-reported number of A’s and B’s scored in Mathematics, English and Spanish Literature during the previous year.

Physical appearance: Self-reported height, weight and appearance by Stunkard figure scale40,41.

Mood: Three items from the Kidscreen questionnaire about their interactions at school, assessing whether they have fun with their friends or feel lonely42,43.

Finally, for certain sub-samples (see available observations in Table 2), we gathered additional auxiliary information:

Expectations: Information regarding subjects’ expectations about their future outcomes, such as their university degree, traveling around the world, living abroad and desired future job.

Self-assessed math abilities: Two types of questions: “How good are you at maths?” and “How much do you like maths?”44.

Time discounting II: Time preferences (patience) measured by the compound staircase version45.

Time perception: Questions about future actions at three levels46.

Data Records

The dataset can be found in Zenodo47 (https://zenodo.org/records/13720112) and is available in different formats (xls, cvs, dta). The screenshots of the complete experimental instructions are also available in the repository. We also provide STATA 1848 scripts for some basic summaries of the available variables.

Sample variables

The experiments were conducted over multiple sessions from 2021 to 2023. A total of 5,890 students started the experiment, but 609 did not finish the entire questionnaire.

In contrast to adults, it is well-known that children and adolescents often find it more difficult to maintain concentration over extended periods and to complete all tasks13. Some of them simply leave the survey at a certain point. We check the responses after each session and reassess the tasks which were not successful. As a result of various adjustments made during the experimental sessions, the survey tasks underwent some changes. Consequently, the number of observations for different variables in our dataset varies. Table 2 provides an overview of the available observations for each task.

The initial questionnaire screen (Table 1) provided essential information about the study, including an introduction to our team and funding sources.

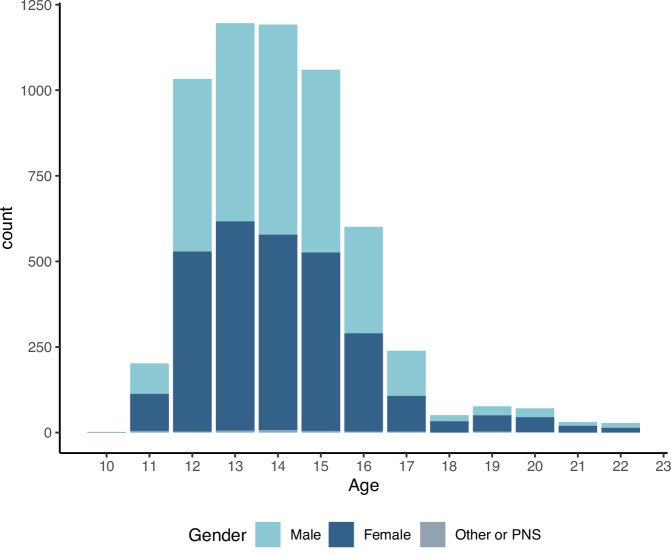

Figure 1 displays the distribution of the final sample by age and gender. The sample is well-balanced in terms of gender; 49.68% are female students and 49.68% male. The remaining subjects (0.64%) are classified as unknown, either because they did not answer or they selected another category.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the sample in terms of age and gender. Note: The histogram contains three gender categories: Male, female and other/I prefer not to say (PNS).

As for educational stages, 8.62% of the sample belongs to primary education, 84.94% belongs to secondary education, 1.90% to sixth form and 4.53% to vocational training. Table 3 presents the distribution of the observations by educational stage. Additionally, it displays the response rate and summary statistics for the ages at each stage.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by educational stage.

| Educational stage | Obs. | RR (%) | Mean Age | Std. Dev. | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary school | 508 | 73.82% | 11.62 | 0.53 | 10 | 13 |

| Secondary school | 5003 | 91.84% | 14.02 | 1.37 | 11 | 18 |

| Sixth form | 112 | 66.07% | 17.09 | 0.34 | 17 | 19 |

| Vocational training | 236 | 88.76% | 19.89 | 1.37 | 17 | 23 |

Note: RR (%) refers to the response rate in each stage. Primary school refers to Educación Primaria Obligatoria (EPO), secondary school refers to Eduación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO) and sixth form refers to Bachillerato. In Spain, compulsory education is until secondary school, after that, they can start vocational training instead of sixth form.

Technical Validation

The study is a laboratory-in-the-field experiment. Data were collected in the school classrooms under the supervision of team members and research assistants.

The data recorded in the software were downloaded for cleaning using Stata48. Variables were coded and incomplete entries were not deleted. Only the age variable was imputed through the year of birth reported by the students and according to the course to which they belonged.

Our experiment includes standard tasks from the literature as well as tasks adapted by our research team from previous literature19. We have extensive prior experience in designing experiments for teenagers and collecting data in primary and secondary schools using lab-in-the-field techniques. Previous evidence suggests that there are no significant differences in outcomes when using hypothetical payoff tasks, such as eliciting risk preferences27–31. Prior to each task, students were provided with a brief description and they were informed of the economic implications of their decisions in hypothetical terms. This ensured that participants fully understood the nature of the tasks, while maintaining the validity of the experimental design and the scalability of the study. Some pilots of the tasks were carried out independently to configure the final design. The changes in the survey are detailed in the variables descriptor available in the repository.

One of the main problems in collecting data from non-standard samples is that some tasks are not understood and participants show inconsistent behavior across them. To address this, our design took into account the results of pilots that adapted the tasks to the adolescent context through the use of visual aids. As a result, the consistency rates are remarkably higher than those reported in the literature7,19,20.

Consistency is assessed by examining how the choices of participants align with their stated preferences in different situations, based on their personal decision-making patterns. Among the data reported for the economic preferences dimension, we find a high percentage of consistent responses in the tasks that require certain within-task consistency. We observe that 82.75% of the individuals who complete the time preference task exhibit consistent behavior. Similarly, 79.20% of individuals report consistent answers in the risk preferences task20. Table 4 includes a distribution of responses for both tasks across their 6 decisions, where a trend can be identified that may represent this high level of consistency. Such enhanced consistency indicates that the data collected from adolescents are reliable and coherent, providing a robust foundation for examining adolescent decision-making processes and developmental trends.

Table 4.

Percentage of responses for each decision.

| The Truck task | The Gumball Machine task | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision num. | A | B | Decision num. | A | B |

| #1 | 83.63% | 16.37% | #1 | 89.43% | 10.57% |

| #2 | 57.80% | 42.20% | #2 | 80.88% | 19.12% |

| #3 | 46.93% | 53.07% | #3 | 45.41% | 54.59% |

| #4 | 39.34% | 60.66% | #4 | 18.19% | 81.81% |

| #5 | 36.66% | 63.34% | #5 | 10.03% | 89.97% |

| #6 | 29.19% | 70.81% | #6 | 5.24% | 94.76% |

Note: Subjects in both tasks can exhibit inconsistent responses within the task, for instance, if they switch back from option B to option A. The same tendency can be observed in both tasks: The majority of subjects begin with option A and change to option B gradually and finally, the majority of subjects end up choosing option B in the last decision.

Usage Notes

The Zenodo repository gives access to the available data together with a descriptive note on the variables and their coding. The variable descriptor includes a definition of the task, some general characteristics, and the specific name under which it is found in the database. We provide further information on the changes that the survey has made over time. In addition, the repository visualizes the experimental screens in the original Spanish language.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International License.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Javier Gonzalez for his amazing job as an illustrator and the following RAs who helped to run the experiments in the schools: Laura Giraldo, Juan Gonzalez, Emilio Nieto, Emilio Pericet, Paula Piña, and Luis Rivero. This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (PID2022-141802NB-I00 and PID2021-126892NB-I00); the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2023-147817NB-I0, PID2022-140661OB-I00, FPU20/05846, PID2019-106146GB-I00 and PGC2018- 093506-B-I00); Excelencia-Junta Andalucía (PY-18-FR-0007); the Andalusian Agency for International Development Cooperation (AACID-0I008/2020); the Department of University, Research and Innovation of the Junta de Andalucía and as appropriate, by “ERDF A way of making Europe”, by the European Union (B-SEJ-280-UGR20); the María de Maeztu Programme of Agencia Estatal de Investigación (CEX2021-001181-M); Comunidad de Madrid EPUC3M11 (V PRICIT); the University of the Basque Country (EHU-N23/50) and the Basque Government (IT1461-22).

Author contributions

A.Al., A.C., J.A.C., A.E., M.P.E., D.J., J.K., D.M., A.S., M.J.V. and P.B. conceived the experiment. M.V., A.Al., A.Ar., T.G., A.I., D.J., P.L., A.C.M., M.P.R., P.R. and M.J.V. conducted the experiment. A.C., J.A.C., J.K., D.M. and P.B. provided data or analysis tools. M.V., A.Al., A.Ar., T.G., D.J., P.L., A.C.M., M.P.R., P.R. and A.S. performed the analysis. M.V., T.G. and J.K. wrote the paper. A.Al., A.C., J.A.C., A.E., M.P.E., D.J., P.L., D.M., A.S. and P.B. reviewed the paper.

Code availability

STATA 1848 software was used. The code for the variables can be found in the aforementioned repository.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41597-024-04298-6.

References

- 1.Dahl, R. E., Allen, N. B., Wilbrecht, L. & Suleiman, A. B. Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature554, 441–450, 10.1038/nature25770 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D. & Sunde, U. Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review100, 1238–1260, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.100.3.1238 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falk, A. et al. Global evidence on economic preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics133, 1645–1692, 10.1093/qje/qjy013 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckel, C., Johnson, C. & Montmarquette, C. Saving decisions of the working poor: Short-and long-term horizons. In Field Experiments in Economics, 219–260, https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1016/S0193-2306-9 (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2005).

- 5.Dohmen, T. et al. Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association9, 522–550, 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chapman, G. B. Time discounting of health outcomes. Economic and Psychological Perspectives on Intertemporal Choice 395–418, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2003-06265-013 (2003).

- 7.Sutter, M., Zoller, C. & Glätzle-Rützler, D. Economic behavior of children and adolescents–a first survey of experimental economics results. European Economic Review111, 98–121, 10.1016/j.euroecorev.2018.09.004 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angerer, S., Bolvashenkova, J., Glätzle-Rützler, D., Lergetporer, P. & Sutter, M. Children’s patience and school-track choices several years later: Linking experimental and field data. Journal of Public Economics220, 104837, 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2023.104837 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golsteyn, B. H., Grönqvist, H. & Lindahl, L. Adolescent time preferences predict lifetime outcomes. The Economic Journal124, F739–F761, 10.1111/ecoj.12095 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piovesan, M. & Willadsen, H. Risk preferences and personality traits in children and adolescents. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization186, 523–532, 10.1016/j.jebo.2021.04.011 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreoni, J., Di Girolamo, A., List, J. A., Mackevicius, C. & Samek, A. Risk preferences of children and adolescents in relation to gender, cognitive skills, soft skills, and executive functions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization179, 729–742, 10.1016/j.jebo.2019.05.002 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brocas, I. & Carrillo, J. D. Introduction to special issue “understanding cognition and decision making by children” studying decision-making in children: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization179, 777–783, 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.01.020 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 13.List, J. A., Petrie, R. & Samek, A. How experiments with children inform economics. Journal of Economic Literature61, 504–564, https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.20211535 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong, C. A. et al. Applying behavioral economics to improve adolescent and young adult health: a developmentally-sensitive approach. Journal of Adolescent Health69, 17–25, 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.007 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brocas, I. & Carrillo, J. D. Steps of reasoning in children and adolescents. Journal of Political Economy129, 2067–2111, 10.1086/714118 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundberg, S., Romich, J. L. & Tsang, K. P. Decision-making by children. Review of Economics of the Household7, 1–30, 10.1007/s11150-008-9045-2 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samek, A., Gray, A., Datar, A. & Nicosia, N. Adolescent time and risk preferences: Measurement, determinants and field consequences. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization184, 460–488, 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.12.023 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huurre, T., Aro, H., Rahkonen, O. & Komulainen, E. Health, lifestyle, family and school factors in adolescence: predicting adult educational level. Educational Research48, 41–53, 10.1080/00131880500498438 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alfonso, A. et al. The adventure of running experiments with teenagers. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 102048, 10.1016/j.socec.2023.102048 (2023).

- 20.Vasco, M. & De Francisco, M. J. V. Holt-laury as a gumball machine. Available at SSRN 449138610.2139/ssrn.4491386 (2023).

- 21.Alfonso, A., Brañas-Garza, P., Jorrat, D., Prissé, B. & Vazquez, M. The baking of preferences throughout high school. Tech. Rep., Mimeo. https://ideas.repec.org/p/aoz/wpaper/316.html (2024).

- 22.Brañas-Garza, P. Teenage girls are egalitarian, and boys are generous. Available at SSRN 473013810.2139/ssrn.4730138 (2024).

- 23.Brañas-Garza, P. & Lomas, P. Developmental equilibrium selection. Available at SSRN 471236610.2139/ssrn.4712366 (2023).

- 24.Organic law 3/2018, of december 5, on the protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights (2018).

- 25.Brañas-Garza, P., Estepa-Mohedano, L., Jorrat, D., Orozco, V. & Rascón-Ramírez, E. To pay or not to pay: Measuring risk preferences in lab and field. Judgment and Decision Making16, 1290–1313, 10.1017/S1930297500008433 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brañas-Garza, P., Jorrat, D., Espn, A. M. & Sánchez, A. Paid and hypothetical time preferences are the same: Lab, field and online evidence. Experimental Economics26, 412–434, 10.1007/s10683-022-09776-5 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kühberger, A., Schulte-Mecklenbeck, M. & Perner, J. Framing decisions: Hypothetical and real. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes89, 1162–1175, 10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00021-3 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuang, Y. & Schechter, L. Stability of experimental and survey measures of risk, time, and social preferences: A review and some new results. Journal of Development Economics117, 151–170, 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.07.008 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Read, D. Monetary incentives, what are they good for? Journal of Economic Methodology12, 265–276, 10.1080/13501780500086180 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beattie, J. & Loomes, G. The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty14, 155–168, 10.1023/A:1007721327452 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horn, S. & Freund, A. M. Adult age differences in monetary decisions with real and hypothetical reward. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making35, e2253, 10.1002/bdm.2253 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coller, M. & Williams, M. B. Eliciting individual discount rates. Experimental Economics2, 107–127, 10.1023/A:1009986005690 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fehr, E., Bernhard, H. & Rockenbach, B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature454, 1079–1083, 10.1038/nature07155 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corgnet, B., Espn, A. M. & Hernán-González, R. The cognitive basis of social behavior: cognitive reflection overrides antisocial but not always prosocial motives. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience9, 287, 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00287 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brañas-Garza, P., Cabrales, A., Espinosa, M. P. & Jorrat, D. The effect of ambiguity in strategic environments: an experiment. arXiv preprint10.48550/arXiv.2209.11079 (2022).

- 36.Fischbacher, U. & Föllmi-Heusi, F. Lies in disguise—an experimental study on cheating. Journal of the European Economic Association11, 525–547, 10.1111/jeea.12014 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomson, K. S. & Oppenheimer, D. M. Investigating an alternate form of the cognitive reflection test. Judgment and Decision Making11, 99–113, 10.1017/S1930297500007622 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delavande, A. & Kohler, H.-P. Subjective expectations in the context of hiv/aids in malawi. Demographic Research20, 817, 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.31 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guilford, J. P. Creativity: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. The Journal of Creative Behavior1, 3–14, 10.1002/j.2162-6057.1967.tb00002.x (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stunkard, A. J. et al. An adoption study of human obesity. New England Journal of Medicine314, 193–198, https://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/nejm198601233140401 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrasco, R. & Gonzalez, D. The impact of obesity on human capital accumulation: An analysis of driving factors. Mimeohttps://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/dt/2024/dt2024-03.pdf (2024).

- 42.Aymerich, M. et al. Desarrollo de la versión en español del kidscreen: un cuestionario de calidad de vida para la población infantil y adolescente. Gaceta Sanitaria19, 93–102, https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/gs/2005.v19n2/93-102/es (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ravens-Sieberer, U. et al. Kidscreen-52 quality-of-life measure for children and adolescents. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research5, 353–364, 10.1586/14737167.5.3.353 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adamecz-Völgyi, A., Jerrim, J., Pingault, J.-B. & Shure, D. Overconfident boys: The gender gap in mathematics self-assessment. IZA Discussion Paperhttps://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/278878 (2023).

- 45.Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Huffman, D. & Sunde, U. The preference survey module: A validated instrument for measuring risk, time, and social preferences. Management Science69, 1935–1950, 10.1287/mnsc.2022.4455 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Keller, T., Kiss, H. J. & Szakál, P. Endogenous language use and patience. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization220, 792–812, 10.1016/j.jebo.2024.02.013 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasco, M. et al. Teenslab dataset10.5281/zenodo.13720112 (2024).

- 48.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: Release 18. College Station TX: StataCorp LLC. (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Vasco, M. et al. Teenslab dataset10.5281/zenodo.13720112 (2024).

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

STATA 1848 software was used. The code for the variables can be found in the aforementioned repository.