Abstract

User satisfaction with Assistive Technology (AT) is one of the crucial factors in the success of any AT service. The current study aimed to estimate satisfaction with AT and the reasons for dissatisfaction and unsuitability among persons with functional difficulties in India. Using the WHO Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment tool, a cross-sectional study was conducted in eight districts, representing four zones of India. Multi-stage cluster random sampling and probability proportional to size techniques were used to select smaller administrative units from the larger ones. Satisfaction was reported in terms of assistive products and service delivery. In total, 8486 participants were surveyed out of which 8964 individuals were enumerated with a response rate of 94.6%. Around 22.2% (1888) of participants had functional difficulties and reported using AT, out of which 3.9% (74) were dissatisfied with their products. The assistive products, assessment and training, and repair and maintenance-related services were reported to be satisfied by approximately 92.2% (1740), 88.4% (1669), and 85.2% (1609) of respondents, respectively. Further, 3.2% (61) and 3.7% (70) of respondents reported that their AT was not suitable for home and public environments, respectively. According to 2.8% (53) respondents, their AT did not assist them in executing daily living activities. Discomfort (56.6%), poor fitting (37.7%), low quality of service (20.7%), and poor aesthetic values (18.9%) were identified as reasons for dissatisfaction. Satisfaction was good for AT received from friends and family but was poor for those received from the public sector. The study shows that overall satisfaction and suitability with AT were high among users with functional difficulties, but few have reported barriers to effective device use and facing challenges in accessing repair and follow-up services.

Keywords: Assistive technology, Assistive technology users, People with disability, Satisfaction, Access, India

Subject terms: Health care, Public health, Population screening

Introduction

Assistive Technology (AT) has been gaining significant global attention in recent years within the context of health and well-being, and quality of life improvement. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 2.5 billion, that is, one out of every three, in the world need at least one or more assistive products to improve their daily functioning and independent living.1 However, only one in ten persons can access the AT they need. With increasing chronic debilitating health problems or diseases and an aging population, the functional limitations are expected to increase the requirement of AT to 3.5 billion by 2050.2

Evidence shows that AT provides effective support to persons with disabilities (PwDs), elders, and those with chronic health conditions for their independent living, everyday activities, occupational and educational performance, and even social inclusion.3–6 In addition, the use of AT helps to reduce the rate of institutionalization, injury, and burden to caregivers or family members.7 While ensuring access to AT in the country, the quality of AT-related service should also be ensured. Access to AT does not necessarily mean user satisfaction with assistive products and services related to AT, or that a functional difficulty has been fully or even partially addressed. The WHO has described the indicator of AT satisfaction as the proportion of assistive product users who are satisfied with their assistive product(s) and related services, in different environments and activities, disaggregated by AT product type.2 Numerous researchers have also employed similar definitions in the past.8,9 Therefore, satisfaction implies the use of AT with an underlying sub-dimension concerning AT products and service delivery and their maintenance. A systematic review of fifty-three studies concluded that the service delivery process contributed to the satisfaction with the usability of ATs in PwDs about achieving aspirations in everyday activities.9

Although user satisfaction is an important outcome measure for AT service, the measurement of satisfaction is challenging to date and there is a limited number of tools available for use among PwDs. The Quebec User Evaluation of Satisfaction with Assistive Technology (QUEST 2.0) is a 12-item outcome measure that assesses user satisfaction, including the physical characteristics of the products and service delivery process.10,11 The challenge in measuring user satisfaction includes the multitude of ATs that are used and various kinds of disability that might confound the assessment of satisfaction. Very often PwDs need multiple ATs, which need separate assessments for satisfaction. Such comprehensive indicators germane to AT satisfaction ideally need to be measured by conducting community-based epidemiological studies in different environments and among persons with various types of disabilities.

In India, the satisfaction rate with AT products and service delivery process is little or not known, and few studies are available on satisfaction-related indicators relating to spectacles use only.12,13 The WHO reported that nearly 90% of people in need of AT live in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), and there are limited data available on AT satisfaction across these nations. Studying satisfaction is critically important since it is one of the overarching elements of AT adoption and participation. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess user satisfaction with AT and the reasons for dissatisfaction and unsuitability, using the WHO Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA) tool among persons with functional difficulties. The study’s findings could lead to potential recommendations for improving the quality of assistive products and services in the country.

Methods

The detailed methodology, including the estimation of the sample size, and sampling technique, was published in a previous paper.14 Briefly, this cross-sectional study was conducted in eight districts selected from four different zones of India spanning November to December 2021. Individuals of all age groups irrespective of health conditions or functional limitations were included in the study. Further, the sampling technique was a multi-stage cluster random sampling with compact segment sampling for household selection. The census enumeration block (CEB), also known as the primary sampling unit for the present study, was listed in each selected district. Using probability proportional to size, thirteen CEBs were selected in each district. Each CEB had a population of approximately 1000 considering all age groups. The study aimed to select 80 to 100 individuals regardless of the age of groups from each CEB.

In the compact segment technique, a CEB was divided into segments of equal population size that had approximately twenty households each (around 80 to 100 population, assuming an average family size of 4–5 in India). One segment was selected randomly from each CEB and the survey proceeded from one end to the other till all twenty households were covered.

Data collection

Two districts, in each of the four zones of the country, North, East, West, and South, were included in the survey. A total of five public health institutes or medical colleges, each located in one of the five zones were involved in the survey. One area supervisor and one survey manager from each institute/medical college were provided training for the study using the World Health Organization, Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (WHO-rATA) tool. The study tool was the WHO rATA digital tool installed in the ArcGIS app.15,16

Measurement of satisfaction and suitability

User satisfaction implies perceptions of the quality of the services, the physical characteristics of the product, the needs of clients, and the extent of alignment with clients’ priorities and aspirations. The WHO rATA tool included a 5-point Likert scale (1-very dissatisfied; 2-dissatisfied; 3-neutral; 4-quite satisfied; 5-very satisfied) to measure the satisfaction indicators with AT to the types of functional difficulty (Table 1): firstly, assistive products, reflect the physical characteristics of the products such as appearance, weight, durability, effectiveness, simplicity to use, comfort, and safety; secondly, assessment and training which reflects the provider competence, even being treated with respect and dignity, provision of all information, emotional support; third, the repair and maintenance related services which reflects the access to services in getting repaired or fix a problem raised with products and simplicity in maintenance. The study tool for suitability also consisted of a similar 5-point Likert scale (1-not at all; 2-not much; 3-moderately; 4-mostly; 5-completely) to assess the suitability of AT in terms of its application at home and in public environment, and daily household activities and participation in society.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants (8486).

| Characteristics | n | Percentages |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 34.5 (20.4) | |

| Age groups (in years) | ||

| < 17 | 2001 | 23.6 |

| 18–39 | 3130 | 36.9 |

| 40–59 | 144 | 25.3 |

| 60–79 | 1082 | 12.8 |

| ≥ 80 | 129 | 1.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 4087 | 48.2 |

| Female | 4397 | 51.8 |

| Place | ||

| Urban | 4151 | 48.9 |

| Rural | 4335 | 51.1 |

| Functional difficulties | ||

| Mobility | 1015 | 11.9 |

| Seeing | 2256 | 26.6 |

| Hearing | 287 | 3.4 |

| Communication | 68 | 0.8 |

| Cognitive | 158 | 1.9 |

| Self-care | 125 | 1.5 |

| Any form disabilities | 2700 | 31.8 |

| AT use among functional difficulties (1888) | ||

| Mobility | 566 | 29.9 |

| Seeing | 1726 | 91.4 |

| Hearing | 143 | 7.5 |

| Communication | 22 | 1.2 |

| Cognitive | 77 | 4.1 |

| Self-care | 76 | 4.0 |

Data management and analysis

The data were analyzed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp 2015, Stata Statistical Software: Release 15, College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). For the analysis, all types of AT were considered as a unit of analysis (one unit), not just AT per se. This means that the responses obtained were analyzed regardless of the type of AT used. The 5-point Likert scale responses were re-categorized as 4&5 = yes (satisfied/suitable), 3 = neutral (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied/neither suitable nor unsuitable), and 1&2 = no (dissatisfied/unsuitable) for each AT satisfaction indicator. In the final analysis, the five-point responses were categorized as “yes”, “no”, and “neutral”. Since the neutral categories data represents less meaning and also to avoid the cluttering of the words, we have not shown the neutral data in Tables 2, 3. The satisfaction was reported in terms of product satisfaction; services related to assessment and training, repair and maintenance of the products, and the suitability of the AT for use at home and public environment and participation in activities of daily living. The findings from the descriptive analysis were summarized as mean, percentages, and standard deviation. The responses were presented as relative frequency. The Chi-square test (or Fisher Exact test if the cell value is less than 5) was done to assess the association with various independent factors with AT satisfaction.

Table 2.

Satisfaction with assistive products among persons with difficulties based on source of funding for AT.

| Source of AT | Satisfaction with Assistive products Yes No. p-value |

Satisfaction with assessment and training Yes No. p-value |

Satisfaction with repair or maintenance Yes No. p-value |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | ||||

| Government | 85 (4.9) | 5 (6.8) | 0.4609 | 89 (5.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0.507 | 85 (5.3) | 4 (8.5) | 0.347 |

| NGO/Charity | 46 (2.6) | 3 (4.0) | 0.459 | 47 (2.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.648 | 45 (2.8) | 1 (2.1) | 0.883 |

| Employer/School | 4 (0.2) | 0 | 0.846 | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 0.958 | 2 (0.1) | 1 (2.1) | 0.085 |

| Insurance | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0.959 | 1 (0.06) | 0 | 0.986 | 1 (0.06) | 0 | 0.972 |

| Out-of-pocket | 1167 (67.1) | 54 (72.9) | 0.292 | 1154 (69.1) | 18 (75.0) | 0.559 | 1120 (69.6) | 34 (72.3) | 0.704 |

| Family/friends | 420 (24.1) | 10 (13.5) | 0.029* | 361 (21.6) | 3 (12.5) | 0.291 | 343 (21.3) | 7 (14.9) | 0.293 |

| Others | 8 (0.5) | 2 (2.7) | 0.066 | 6 (0.4) | 0 | 0.918 | 5 (0.3) | 0 | 0.866 |

| Don’t Know | 9 (0.5) | 0 | 0.687 | 8 (0.5) | 0 | 0.892 | 8 (0.5) | 0 | 0.794 |

| Total** | 1740 (92.2) | 74 (3.9) | 1669 (88.4) | 24 (1.3) | 1609 (85.2) | 47 (2.5) | |||

*Statistically significant **Row Percentages; Yes: quite/very satisfied; No: dissatisfied/very dissatisfied; Neutral data not shown here.

Table 3.

Suitability of the AT for home, public environments, and participation in activities based on the source of AT.

| Source of AT | Suitability of the AT for home and surroundings | Utility of the AT for participation in activities | Suitability of the AT for outdoor and public environments | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | Yes | No | p-value | |

| n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | n,(%) | ||||

| Government | 84 (5.1) | 6 (9.8) | 0.1368 | 86 (5.4) | 4 (7.54) | 0.489 | 77 (5.1) | 8 (11.4) | 0.043* |

| NGO/Charity | 42 (2.6) | 3 (4.9) | 0.290 | 41 (2.6) | 3 (5.66) | 0.217 | 38 (2.5) | 4 (5.71) | 0.148 |

| Employer/School | 4 (0.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0.179 | 4 (0.3) | 1 (1.88) | 0.160 | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 0.833 |

| Insurance | 1 (0.06) | 0 | 0.964 | 1 (0.06) | 0 | 0.968 | 1 (0.07) | 0 | 0.955 |

| Out-of-pocket (self) | 1094 (66.6) | 41 (67.2) | 0.930 | 1071 (67.3) | 35 (66.04) | 0.835 | 1031 (68.6) | 40 (57.1) | 0.049* |

| Family/friends | 400 (24.3) | 9 (14.7) | 0.078 | 372 (23.4) | 6 (11.32) | 0.032* | 336 (22.4) | 14 (20.0) | 0.659 |

| Others | 10 (0.6) | 1 (1.6) | 0.388 | 8 (0.5) | 4 (7.54) | 0.000* | 7 (0.5) | 4 (5.71) | 0.000* |

| Don’t Know | 8 (0.5) | 0 | 0.744 | 8 (0.5) | 0 | 0.769 | 8 (0.5) | 0 | 0.694 |

| Total** | 1643 (87.0) | 61 (3.2) | 1591 (84.3) | 53 (2.80) | 1502 (79.5) | 70 (3.7) | |||

*Statistically significant **Row Percentages. Yes: mostly/completely suitable; No: not at all/not much; Neutral data not shown here.

Ethics clearance and informed consent

The present study was part of a main study conducted to estimate assistive technology service indicators using the WHO rATA tool. This main study was reviewed and approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of a tertiary care institute (Ref. no. IEC-632/03.09.2021), and it adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The survey supervisor explained the study procedures to each participant using the participant information sheet (PIS), and a copy of the PIS was given to each of them. Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians for minors.

Results

In total, 8486 participants were surveyed out of 8964 enumerations, with a response rate of 94.6%. Of the total respondents, 48.2% (4087) were males and 48.9% (4151) were urban residents. The highest proportion of respondents belonged to the age group 18–39 years (36.9%, 3130), followed by 40–59 years (25.3%, 2144, Table 1). Visual disability (26.6%) was the most common among all types of disabilities followed by mobility problems (11.9%) and hearing problems (3.4%, Table 1). Given any type of disability, 2700 participants have any form (some or severe or total) of disability.

The results showed that 1888 participants with functional difficulties used at least or one more AT (22.2%, 1888/8486), with AT for seeing problems being the highest used among all types, reaching up to 91.4% of participants (1726), followed by AT use for mobility problems (566, 29.9%). As far as sources of AT are concerned, 67.4% (1273) of respondents obtained the AT by paying themselves (out-of-pocket), and 23.5% (444) reported that they got it from their friends or family. The rest 5.0% (94) received the AT from public health facilities and another 2.6% of users (49) received it from non-government sectors or charity hospitals.

Satisfaction with assistive products

The results showed that approximately 92.1% of AT users (1740/1888) found satisfaction with the products they used. But a smaller proportion 3.9% (74) of users were dissatisfied with their assistive products (Table 2). The highest satisfaction was shown among users who had bought the products by themselves (67.1%) followed by those provided by family members or friends (24.1%, Table 2).

Among the 74 participants who were dissatisfied with AT, the most frequent reasons for poor satisfaction were pain and discomfort while using AT (56.8%, 42), and poor fitting of the devices (22.9%, 22), followed by less durability (12.2%, 9) and lack of aesthetic value (6.8%, 5) and feeling unsafe and heaviness during use. Besides these, thirteen participants were dissatisfied due to the lack of availability of maintenance and repair services.

Satisfaction with assessment and training, repair and maintenance of assistive products

Out of the 1888 participants who used AT, 88.4% of respondents reported that they were satisfied with the assessment and training they received, and quite a similar proportion of participants (85.2%) reported satisfaction with AT repair and maintenance services. In contrast, a total of 24 (1.3%) respondents were dissatisfied with the assessment and training of AT products, and 47 (2.5%) were dissatisfied with the repair, maintenance, and follow-up services based on their experiences, with the rest remaining neutral (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied). Again, AT either procured from out-of-pocket payment (69.1%) or those given by family members or friends (21.6%) were shown to have the highest satisfaction among users regarding training and maintenance. The association between satisfaction with AT was statistically significant in those who had obtained AT from family or friends. (p-value = 0.029, Table 2)

The major causes of dissatisfaction with assessment and training were poor quality of the service (45.8%, 11/24), higher costs of service utilization (33.3%, 8/24), and long waiting time to access the service (20.8%, 5/24, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Reasons for dissatisfaction with services (assessment and training) of Assistive products (33 responses from 24 individuals).

*Statistically significant **Row Percentages; Yes: quite/very satisfied; No: dissatisfied/very dissatisfied; Neutral data not shown here.

Suitability of assistive products

Given the suitability of assistive products, 87.0% (1643/1888) of the respondents reported that products owned by them were suitable for use at home and nearby surrounding environments, but 3.2% (61) of respondents reported the products were unsuitable for the same (Table 3). Further, 79.5% (1502) and 84.3% (1591) of participants said that the products they used were also suitable for the public environments and helped them do what they wanted regarding daily living activities and self-care respectively. In addition, 3.7% and 2.8% of the respondents reported poor suitability of products for public environments and daily living activities respectively.

The study also reported that there was a statistically significant association between obtaining assistive products from the government sector and poor suitability in the public environment (p-value < 0.05, Table 3). At the same time, the products obtained from friends or family members were significantly associated with better suitability for performing various daily living and self-care activities (p-value < 0.05, Table 3).

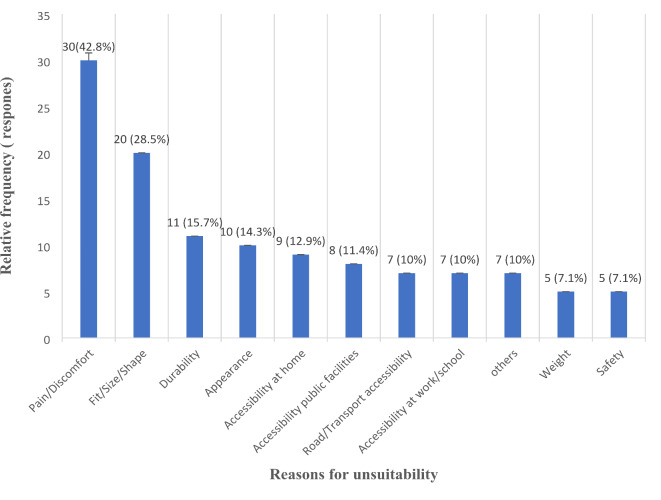

Considering the factors attributing unsuitability of assistive products while used in various environmental context (home – executing household activities and self-care; participation activities- social events, school or colleges, and public places- markets, theatres), the main reasons were pain and discomfort (42.8%, 30/70), poor fitting or size of the products (28.5%, 20/70), less durability (15.7%, 11/70), and poor appearance (14.3%, 10/70). In addition, lack of accessibility in the home environment (12.9%, 9/70), public facilities (11.4%, 8/70), and road and transport accessibility (10.0%) were also reported as reasons for dissatisfaction (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Reasons for unsuitability of assistive products in different environments (119 responses from 70 participants who reported unsuitability in a public environment).

Discussion

Understanding user satisfaction with AT is of paramount importance since it is one of the key predictors of AT adoption and participation. For example, when an AT is not suited to the client’s needs and has not fulfilled their priorities, the same will be rejected or used sub-optimally. Among AT users, PwDs are the most vulnerable population who require them most compared to the rest of the population. Disability, an umbrella term that covers impairment, activity limitation, and participation restriction, is an outcome of the negative interaction between intrinsic features of the person and features of the overall environment context in which the person lives, works, and interacts with others17. Assistive Technology helps PwDs overcome this negative interaction that hinders their full participation at both personal as well as environmental levels and should compensate for decreased body function as well as prevent further loss of function and ability.

In LMICs, there has been a critical research gap in the context of satisfaction measurement among AT users. The current comprehensive study on AT satisfaction among the disabled, the first of its kind in India, was part of a sub-national rATA study, conducted to understand various AT service indicators in the country. Overall, the results of the present study show that clients are moderately satisfied as far as characteristics of their assistive products are concerned; be it weight, appearance, simplicity of use, safety, durability, and effectiveness, and AT services being received in terms of assessment, training, repair and maintenance for products.

Higher satisfaction is observed in those users who obtain the AT from friends or family members or buy themselves compared to other sources of AT. Although the present study does not identify the factors leading to satisfaction with products, other studies reported that ease of use, safety, lightweight, and feeling of comfort with products lead to better satisfaction.9,18,19 In terms of suitability of AT, most of the participants felt that AT being owned by them is appropriate, useful, and suitable for use at home, in the public environment, in executing daily living and self-care activities, and visiting places like schools or colleges, workplaces, neighborhood, or going for leisure and recreational purposes.

The factors that lead to higher satisfaction in terms of services and suitability with AT are ease of operation, comfort, being treated with respect and dignity, emotional support, and customized AT, perhaps helping to align with the principle of a client-centered approach. A plethora of evidence exists that proves that a client-centered approach is effective in increasing user satisfaction with AT services.9,20,21 However, future studies are warranted to determine the various facilitators and barriers to satisfaction in AT usage. Furthermore, a pre-requisite for a client-centered approach for PwDs is teamwork, involving caregivers, family members, users, therapists, and support organizations. In India, the very nature and cultural adoption of joint family, and multiple organizations working for disabilities along with favorable social capital may perhaps play an important role in satisfaction, and further helping to align with a client-centered approach. Studies from India reported that a good supportive network involving relatives, friends, and neighbors, makes a favorable social capital and also supports caregivers of PwDs or the elderly population in bringing about a better quality of life and psychological well-being of the PwDs.22,23 However, future studies, including qualitative studies, are required to quantify the relationship between social capital and AT satisfaction among PwDs. Besides, the advantage of self-purchased products is that they usually meet user’s expectations, thereby leading to higher satisfaction. Products being received at subsidized rates under various government schemes may also contribute to satisfaction, especially in low-income settings when there are no alternative sources of AT. For example, the ADIP scheme (Assistance to Disabled Persons) of the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MoSJE) in India lists 51 assistive products for visual loss that can be accessed either free of charge or at a subsidized rate according to the family income of the beneficiaries.24,25

The current study also explored the reasons for the unsuitability of the devices being used. Pain or discomfort when using AT, problems with fitting, size, and weight, and poor aesthetics of the devices were the most frequent reasons for the unsuitability of the products. Similar reasons for dissatisfaction with devices have been reported in other studies also.18 A study from two coastal districts of Eastern India reported that uncomfortable glasses and higher cost of the service were the most frequent reasons for dissatisfaction, leading to poor access to the service.26 Cosmetic issues are especially important in determining satisfaction with ATs that are worn on exposed areas of the body, like glasses, crutches, etc. In addition, previous studies have also reported that AT received from the public sector has poor acceptability.27 This finding was also demonstrated in the current study. A rapid assessment survey on visual impairment, including blindness revealed that the cost of the service and spectacles and lack of availability of service were among the reasons for dissatisfaction, resulting in low uptake of the services.27

Overall, the literature on satisfaction with AT is scarce, with the majority of studies focussing on spectacles or other common mobility products. Numerous studies have reported satisfaction with one or a few ATs, but a comprehensive assessment of all aspects of AT is lacking. A study conducted in Sweden to assess user satisfaction with manual wheelchairs and rollators using QUEST tool showed overall high satisfaction with both types of devices.18 Numerous rATA surveys have been conducted in other countries and the level of satisfaction with AT ranges from 40.29% in Senegal to 90.61% in Guatemala.16,29–31 (Tables 4, 5) Among the countries of the WHO-SEAR, India has the highest user satisfaction with AT, closely followed by Nepal (84.01%), Maldives (83.57%), and Indonesia (82.2%). In consonance with previous studies, the level of satisfaction was lowest with AT maintenance and repair services. Similarly, the suitability of AT was found to be poor in a public environment as compared to the home environment. (Table 4)

Table 4.

Dissatisfaction with Assistive Technology from Rapid Assessment Technology Assessment in other countries and India.

| Country/Region | Year | Sample Size | Dissatisfaction with (%) | Unsuitability of AT to (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Products | AT assessment /training | Repair, maintenance | Home environment | Participation in activities | Public environments | |||

| Western Guatemala | 2021 | 3050 | 9.0 | 4.0 | 17.0 | 12.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 |

| Bangladesh | 2021 | 11,187 | 11.0 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 17.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Sierra Leone | 2019 | 2076 | 26.2 | 24.6 | 26.5 | 23.1 | 20.0 | – |

| Indonesia | 2019 | 2046 | 8.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 6.5 | 6.8 | – |

| Pakistan | 2021 | 62,723 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 13.1 | 7.4 | 7.2 | – |

| Current Study | 2022 | 8486 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

Table 5.

Comparison of satisfaction with assistive technology among selected countries of six WHO regions in the world.

| Country (Year) | Satisfaction with assistive products (%) | Satisfaction with assessment and training (%) | Satisfaction with repair or maintenance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Region (EUR) | |||

| Azerbaijan (2021) | 47.68 | 37.64 | 19.24 |

| Georgia (2021) | 62.24 | 52.95 | 27.98 |

| Italy (2021) | 83.61 | 58.31 | 37.82 |

| Poland (2021) | 87.19 | 88.87 | 38.14 |

| Sweden (2021) | 87.18 | 81.09 | 50.8 |

| Tajikistan (2021) | 73.85 | 76.61 | 74.77 |

| Ukraine (2021) | 80.15 | 52.02 | 36.7 |

| African Region (AFR) | |||

| Burkina Faso (2021) | 80.39 | 55.99 | 54.03 |

| Kenya (2021) | 62.48 | 61.92 | 48.66 |

| Liberia (2021) | 50.22 | 30.57 | 18.06 |

| Malawi (2021) | 61.9 | 56.78 | 39.93 |

| Senegal (2021) | 40.29 | 34.61 | 29.02 |

| Togo (2021) | 70.63 | 62.9 | 49.7 |

| Western Pacific Region (WPR) | |||

| China (2021) | 82.86 | 59.28 | 50.96 |

| Mongolia (2021) | 72.17 | 60.05 | 51.36 |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) | |||

| Djibouti (2021) | 76.09 | 75.87 | 74.78 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic) | 85.55 | 79.71 | 73.62 |

| Iraq (2021) | 68.13 | 53.43 | 49.64 |

| Jordan (2021) | 83.49 | 74.94 | 70.83 |

| Pakistan (2019) | 85.94 | 82.79 | 78.48 |

| Region of the Americas (AMR) | |||

| Dominican Rep. (2021) | 78.34 | 84.88 | 48.64 |

| Guatemala (2021) | 90.61 | 46.95 | 46.01 |

| South-East Asian Region (SEAR) | |||

| Indonesia (2021) | 82.2 | 78.91 | 78.1 |

| Maldives (2021) | 83.57 | 56.63 | 57.83 |

| Myanmar (2021) | 66.12 | 63.54 | 60.55 |

| Nepal (2021) | 84.01 | 54.23 | 61.87 |

| India (2021) | 92.2 | 88.4 | 85.2 |

The findings of the current study could be beneficial for planning, designing, and delivering quality AT services, that can help to increase client satisfaction with AT. Constructive and timely feedback from PwDs in line with a client-centered approach is essential to enhancing their satisfaction with the products they are using. Furthermore, training of rehabilitation staff will improve the satisfaction of both clients and caregivers. Competency of the therapists (assistive technologist) concerning skills, knowledge, understanding of the products in line with the client’s need and participation and user’s learning ability is an important prerequisite for the client to adopt the products as well as satisfaction with AT.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no standardized and universally acceptable AT service delivery model to date. Although the assistive devices production and development is advancing rapidly over the last few years, including information and communication technology (ICT), the AT service sector is not advancing at the same pace. Therefore, there is a need for developing a standardized and universally applicable AT service delivery model that can help to improve independence and quality of life of the end users.

The authors propose a model named Clinico-Social Model of AT service. Originally this model was developed by the authors for inclusive service of people with low vision and blindness.32 The principle of the model may be applicable for AT service. The model can help to address clinical and feasible rehabilitation part of AT service in the hospital whereas the AT service-related socio environment part can be taken care of through a community-based networks with multiple organizations. For this, the health facilities need to perform a thorough mapping of all relevant organizations in their catchment areas. The model emphasizes the importance of maintaining a continuum of care for persons with disabilities from the hospital or clinic to community based services.

Furthermore, in AT sector, we introduce the service delivery model can be categorized into opportunistic and non-opportunistic services. Firstly, opportunistic model for AT services will cater to patients who visit hospital for their health needs for the first time or to avail follow up for some other services like disability certificates. These patients can access AT services in the form of Assessment, Solution, Selection, and Training (ASSET) for the use of AT. The same practices can be followed by local partner organizations. Second, non-opportunistic model for AT services will cater to those who visit places other than hospital and are provided AT services, e.g. off the shelf AT or in non-health organizations. The end users can visit those centers for their non-health needs related to disabilities. Each AT can have a user manual or audio-visual training record. If any PwD needs further clinical testing and hospital services, they can be referred to a base hospital, like a hub and spoke model. The primary purpose of the proposed AT service model is to draw attention of health practitioners and policymakers to the need of person-centered disability services in the health facilities and other non-health facilities. Such a model potentially can cater to a wide range of services related to AT by involving multiple organizations along with multiple human resources with less resources from a single facility. Such a model is currently being run in Delhi where nearly 80 organizations including school for the blind are in the network.32,33

One of the strengths of the current study is that it documents the various dimensions of satisfaction with AT, and also the leading causes of dissatisfaction. Further, the sound methodological design and the use of an internationally validated tool make the results comparable with other countries. The study is the first of its kind in India, which will be instrumental in improving the quality of AT services for PwDs and help in the creation of an inclusive society.

There are a few limitations in the study that need to be acknowledged. First, the reasons for dissatisfaction with each product cannot be discerned by problem-specific analysis, as the unit of analysis was not a single assistive product. Moreover, the big data obtained from a population-based study makes it challenging and complicated to analyze problems specifically. Nonetheless, it is necessary to investigate such analysis in future research. It is also important to investigate user satisfaction segregated by particular products or types of functional difficulties or disabilities. Second, geographical and language differences may lead to various interpretations of the same question for satisfaction by participants from different states. Third, the study tool has subjective questions that can be influenced by social desirability bias. Fourth, the study did not investigate the effect of confounding factors like educational status, duration of device used, and severity of disabilities on satisfaction.

Conclusions

Client satisfaction in the field of AT is one of the integral outcomes in addition to clinical and functional improvement, and quality of life. The provision of user-centered assistive products and services is critical for effective independent living and participation in the society for PwDs. Current study reported good satisfaction among PwDs with AT in terms of the product aesthetics and in achieving clients’ needs for executing daily activities. On the other hand, the reasons for dissatisfaction reported were pain and discomfort, poor appearance and fitting, poor quality of service, lack of accessibility to home and public environment. The study will provide important feedback to all stakeholders working with AT as well as users and their caregivers to critically evaluate their products and service delivery.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the area supervisors, the enumerators, local health workers and administrative staff and their respective institutes for participation in the survey. Pratap Kumar Jena, (School of Public Health, KIIT Deemed to be University, Bhubaneswar, Odisha), Donald S Christian (Community Medicine, GCS Medical College, Ahmedabad), Edmond Fernandes (Edward & Cynthia Institute of Public Health, CHD Groups, Bangalore), Uday Shankar Singh, (Pramukhswami Medical College & Shree Krishna Hospital, Bhaikaka University, Anand, Gujarat), Ramachandra Kamath, (Community Medicine, Kodagu Institute of Medical Sciences Karnataka).

Author contributions

SSS and MS were responsible for all content of the draft. SSS, MS, KJ, and KA were responsible for the study planning and the study design, definition of intellectual content. TJS helped in administrative approval and made suggestions to improve the draft. The authors listed met authorship criteria, reviewed the manuscript before finalization, and had full access to the data. SSS is the principal investigator and guarantor of the study.

Funding

The research is non-commercial and conducted in the interest of public health. The Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi supported the study and publication (01/ICMR/rATA/2023-NCD-II). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the present study, including study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The interview questionnaire used for data collection can be accessed at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-ATM-2021.1. Datasets used in this paper (tables, figures, graphs, and related files) can be requested after communication with the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World report on disability. Geneva, Switzerland WHO. 2011; Last accessed on 23 Nov. 2023

- 2.Organziation WH. Global Report on Assistive Technology (GReAT). 2022. Last accessed on 23 Nov. 2023

- 3.Kisanga, S. E. & Kisanga, D. H. The role of assistive technology devices in fostering the participation and learning of students with visual impairment in higher education institutions in Tanzania. Disability Rehabilitation: Assistive Technol17(7), 791–800 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNicholl, A., Casey, H., Desmond, D. & Gallagher, P. The impact of assistive technology use for students with disabilities in higher education: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol16(2), 130–143 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittaker, G., Wood, G. A., Oggero, G., Kett, M. & Lange, K. Meeting AT needs in humanitarian crises: the current state of provision. Assistive Technol33(sup1), 3–16 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNicholl, A., Desmond, D. & Gallagher, P. Assistive technologies, educational engagement and psychosocial outcomes among students with disabilities in higher education. Disability Rehabilitation: Assistive Technol18(1), 50–58. 10.1080/17483107.2020.1854874 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madara, M. K. Assistive technologies in reducing caregiver burden among informal caregivers of older adults: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol11(5), 353–360 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demers, L., Wessels, R., Weiss-Lambrou, R., Ska, B. & De Witte, L. P. Key dimensions of client satisfaction with assistive technology: a cross-validation of a canadian measure in The Netherlands. Assist technol Res Ser27, 250–258 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsson Ranada, Å. & Lidström, H. Satisfaction with assistive technology device in relation to the service delivery process-A systematic review. Assist Technol31(2), 82–97 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demers, L., Weiss-Lambrou, R. & Ska, B. Development of the Quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST). Assistive Technol8(1), 3–13. 10.1080/10400435.1996.10132268 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demers, L., Weiss-Lambrou, R., Ska, B. & Demers, L. Item analysis of the quebec user evaluation of satisfaction with assistive technology (QUEST). Assistive Technol12(2), 96–105 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narayanan, A., Kumar, S. & Ramani, K. K. Spectacle compliance among adolescents: a qualitative study from Southern India. Optometry Vision Sci94(5), 582–587 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narayanan, A., Kumar, S. & Ramani, K. Spectacle compliance among adolescents in Southern India: Perspectives of service providers. Indian J Ophthalmol66(7), 945–950 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Senjam, S. S. et al. Assistive technology usage, unmet needs and barriers to access: a sub-population-based study in India. The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia15, 100213. 10.1016/j.lansea.2023.100213 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization (WHO). rapid Assistive Technology Assessment tool (rATA) [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 22];Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-ATM-2021.1

- 16.Boggs, D. et al. Measuring access to assistive technology using the WHO rapid assistive technology assessment (rATA) questionnaire in Guatemala: results from a Population-based Survey. Disability, CBR Inclusive Dev33(1), 108–130 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) | United Nations [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 19];Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

- 18.Samuelsson, K. & Wressle, E. User satisfaction with mobility assistive devices: an important element in the rehabilitation process. Disability Rehabilitation30(7), 551–558. 10.1080/09638280701355777 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Afghanistan A, Mohapatra BK. Users’ Satisfaction with Assistive Devices in Afghanistan.

- 20.Townsend, E. & Wilcock, A. A. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: a dialogue in progress. Canadian J Occupational Therapy71(2), 75–87 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arthanat, S., Simmons, C. D. & Favreau, M. Exploring occupational justice in consumer perspectives on assistive technology. Can J Occup Ther79(5), 309–319 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jindal, P. & Sharma, A. Structural social capital of parents having persons with disability in Chandigarh. Int J Adv Res (Indore)9(11), 754–761 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhammad, T., Kumar, P. & Srivastava, S. How socioeconomic status, social capital and functional independence are associated with subjective wellbeing among older Indian adults? A structural equation modeling analysis. BMC Public Health10.1186/s12889-022-14215-4 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Disability division, Empowerment M of SJ and. National Policy For Persons with Disabilities < http://socialjustice.nic.in/policiesacts3.php>. 2017;

- 25.Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Govt. of India. Pattern of Assistance during 12th Five Year Plan- National Programme for Control of Blindness. New Delhi: 2013.

- 26.Bhardwaj, A. et al. Rapid assessment of avoidable visual impairment in two coastal districts of eastern India for determining effective coverage: a cross-sectional study. J Ophthalmic Vision Res10.18502/jovr.v18i2.13185 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gajiwala, U. et al. Compliance of spectacle wear among school children. Indian J Ophthalmol69(6), 1376–1380 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marmamula, S., Khanna, R. C., Shekhar, K. & Rao, G. N. A population-based cross-sectional study of barriers to uptake of eye care services in South India: the Rapid Assessment of Visual Impairment (RAVI) project. BMJ Open4(6), e005125. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005125 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bangladesh Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA), May 2021 - Bangladesh | ReliefWeb [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 27];Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/bangladesh/bangladesh-rapid-assistive-technology-assessment-rata-may-2021

- 30.Ossul-Vermehren, I., Carew, M.T. and Walker J. Assistive Technology in urban low-income communities in Sierra Leone and Indonesia: Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA) survey results. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Oct 27];Available from: https://at2030.org/assistive-technology-in-urban-low-income-communities-in-sierra-leone-and-indonesia/

- 31.World Health Organization G. Rapid Assistive Technology Assessment (rATA): Baseline Survey in Pakistan. 2021. Last accessed on 23 Nov. 2024

- 32.Senjam, S. S. Developing a disability inclusive model for low vision service. Indian J Ophthalmol69(2), 417–422. 10.4103/ijo.IJO_236_20 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senjam, S. S. et al. Improving assistive technology access to students with low vision and blindness in Delhi: a school-based model. Indian J Ophthalmol71(1), 257–262 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The interview questionnaire used for data collection can be accessed at https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-ATM-2021.1. Datasets used in this paper (tables, figures, graphs, and related files) can be requested after communication with the corresponding author.