Abstract

Linear compartmental models are often employed to capture the change in cell type composition of cancer cell populations. Yet, these populations usually grow in a nonlinear fashion. This begs the question of how linear compartmental models can successfully describe the dynamics of cell types. Here, we propose a general modeling framework with a nonlinear part capturing growth dynamics and a linear part capturing cell type transitions. We prove that dynamics in this general model are asymptotically equivalent to those governed only by its linear part under a wide range of assumptions for nonlinear growth.

Keywords: Cancer, Compartments, Heterogeneity, Linear models, Nonlinear growth

Introduction

Populations of cancer cells are typically heterogeneous (Kleppe and Levine 2014; Alizadeh et al. 2015; Pe’er et al. 2021), which means that different types of cells can be identified within the same population on the basis of their different genetic or phenotypic make-ups. Heterogeneity can fuel tumor evolution by affording adaptability, since subpopulations with distinct phenotypes can thrive in distinct somatic environments (Ramón y Cajal et al. 2020) and, in any one of such environments, adaptive peaks may be only a few mutational steps away from some of these subpopulations. Hence, devising sensible targets for tumor therapies is complex and tumors can find ways to evade immune surveillance and drug interventions (McGranahan and Swanton 2017). Reaching a solid understanding of tumor heterogeneity is thus believed pivotal to advance tumor biology and clinical research (Alizadeh et al. 2015; Pillai et al. 2023).

Heterogeneity of cancer cell populations is not a static phenomenon, as cells can change their type, for example via stochastic switching (Gupta et al. 2011). To keep track of the dynamics of different cell types, compartmental models have been employed to model populations of cancer cells. Different compartments correspond to different cell types with transitions between compartments describing the flow of cells through types (Derényi and Szöllősi 2017; Koziol et al. 2020; Magni et al. 2006; Michelson and Leith 1993; Michor et al. 2005; Panetta 1997; Panetta et al. 2006; Simeoni et al. 2004; Werner et al. 2013). Linearity is a common assumption in compartmental models of cancer cells (Panetta and Adam 1995; Panetta 1997; Kozusko et al. 2001; Panetta et al. 2006; Ledzewicz and Schättler 2007; Fornari et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014, 2019; Raatz et al. 2021; Li and Thirumalai 2022). In particular, per-capita growth rates of, and transition rates between, cell types, especially prior to treatment, are often supposed to be fixed and independent of population abundances. This assumption can simplify, among other things, the computation of the stationary distribution of cell types (Werner et al. 2013), the sensitivity analysis of growth rates to model parameters (Zhou et al. 2019) and, more in general, the characterization of demographics (e.g. cell age distribution) in the population (Boettcher et al. 2018). From a modeling perspective, such simplification is welcome as model analysis is typically complicated by nonlinearities introduced once treatment regimes are modeled.

But the assumption of linearity implies a population growing exponentially, which is only sustainable for a short time unless model parameters are tuned to guarantee zero growth (Dingli et al. 2007). More realistically, growth dynamics of the total population size of untreated cancer cells as observed in experiments are often described as nonlinear (Benzekry et al. 2014). For example, the formula for logistic growth, which is quadratic in population size (Nowak 2006, Ch. 2), is a usual candidate for fitting growth data of cancer cell populations and a benchmark or an inspiration for alternative, more sophisticated models of these same data (Jin et al. 2017; Bobadilla et al. 2019; Johnson et al. 2019; Sahoo et al. 2021; Roy et al. 2022).

Overall, there is a potential tension between the assumption of linearity, which is convenient for modeling heterogeneity of any sort in populations of cancer cells, and the observation that these populations generally grow in a nonlinear fashion. However, this tension is alleviated by data about non-genetic heterogeneity driven by stochastic switching among cell phenotypes. Experiments in different systems showed that linear models (e.g., Markov chains) accurately predict the dynamics of the relative frequencies of cancer cell types, in particular their asymptotic distribution, in populations seeded with samples from a heterogeneous population (Gupta et al. 2011; Pisco et al. 2013; Su et al. 2017; Risom et al. 2018; Dirkse et al. 2019; Najafi et al. 2023). This is empirical evidence that growth dynamics of cancer could be largely inconsequential for studies of its heterogeneity.

However, growth dynamics that are deemed realistic for the abundances of cancer cells often imply that the population eventually approaches a unique stable size. An example is logistic growth, under which the population size invariably stabilizes at carrying capacity. This invites a theoretical explanation for the observed irrelevance of population growth in studies of heterogeneity. Existence and uniqueness of an attracting stable state for growth dynamics suggest that transition dynamics among cell types may occur, by and large, around the equilibrium size, where growth dynamics tend to vanish and the distinction between abundance and relative frequency of cell types loses its significance. This argument, which is found for example in (Shah et al. 2023) on phenotypic heterogeneity, appears valid at an intuitive level. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, it has not been made formally rigorous so far.

Nonlinear dynamics in numerous systems are often crucial to our understanding of these systems. But, as we will show rigorously in the present manuscript, nonlinear dynamics of growth turn out to be ultimately irrelevant to modeling heterogeneity of cancer cells. We propose a generic modeling framework that combines nonlinear growth dynamics with linear transition dynamics for heterogeneous populations of cells. The framework can accommodate the main forms of nonlinear growth dynamics usually associated with cancer cell populations and is not committed to any specific kind, i.e. genetic or phenotypic, of heterogeneity. We then use the concept of asymptotic equivalence as defined by the qualitative theory of differential equations (Brauer and Nohel 1989) and related results (Yakubovich 1951; Brauer 1962). In particular, we prove that dynamics of the proposed model are asymptotically equivalent to those governed exclusively by the linear part of it. In the context of studying cancer heterogeneity, our work contributes to justify the use of linear models of cell-type transitioning that neglect cancer growth dynamics.

Model

We model the dynamics of a cell population where is the abundance of cells of type i () via the following differential equation

| 1 |

where , , indicates transposition, is the initial population, which is a nonzero vector with non-negative components, while

| 2 |

with , is the total population size with . In what follows, we will often use the streamlined notation N for . The scalar-valued function g(N) is differentiable on and there exist positive constants and (with ), which may depend on the specific form of g and not be necessarily unique, such that

| 3 |

and

| 4 |

With this formalism, we can introduce, for example, logistic growth by setting or Gompertz growth by setting with K a positive constant and and .

The function g modulates , which is a diagonal matrix with (i, i)-entry () equal to . We take to be equal to , where is the per-capita birth rate and is the per-capita death rate at time t, so that is the (possibly time-dependent) intrinsic growth of cells of type i. The are uniformly bounded above by , i.e., for all , where we use the 1-norm for matrices, i.e. for a matrix . We also assume that the average

| 5 |

of the type-specific growth rates weighted by cell-type abundance is integrable and takes value 0 at most a finite number of times so that, eventually, remains positive. In particular, there is some such that

| 6 |

The linear part of Eq. (1) captures cell transitions among types and, ultimately, heterogeneity in the population. is a constant square matrix. Its non-diagonal entries in column i () are non-negative and contain the transition rates from type i into other types, while the non-diagonal entries in row i () of contain the transition rates from other types into type i. We impose the condition

| 7 |

where , so that cell flow out of each type equals cell flow into that type:

| 8 |

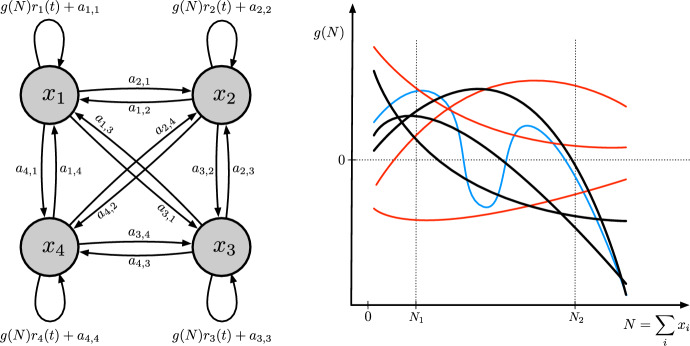

Fig. 1 gives a schematic representation of the model for the case and possible shapes for the function g.

Fig. 1.

The left panel gives a schematic representation of the model in Eq. (1) for the case . The right panel reports possible shapes of the function g in this model. Black lines represent functions that satisfy for and for for constants and . These functions are within the scope of our model. Red lines represent functions that fail to satisfy these inequalities and are, therefore, out of the scope of the model. The blue line represents a function that is within the model scope, but since this function has more than one root the main result in this paper does not apply to this specific choice of the function g, see Sect. 4. For ease of visualization, in this panel the same and are kept for all depicted functions. However, these constants generally depend on the specific function g and, for a given function, they may not be unique

Solutions of Eq. (1) are nonnegative and bounded. As for non-negativity, if , then and the fact that non-diagonal entries of are non-negative imply that

| 9 |

As for boundedness, we note that, since for some constants and we have for and for , then we have that for and for . Therefore, we can define , , and and consider the compact set

| 10 |

where is the non-negative orthant and is the 1-norm for vectors, i.e. . Taking the time derivative of Eq. (2) while using Eqs. (1) and (7),

| 11 |

Since with equality holding when , the sign of is either 0, when , or equal to the sign of g(N). When , and, by Eqs. (3) and (11), and , while when , and, by Eqs. (4) and (11), and . Therefore, H is positively invariant for Eq. (1). Since , all solutions of Eq. (1) are found within H and, therefore, are bounded.

Asymptotic Equivalence

Our main result consists in showing that, under certain conditions, the dynamics of our model are ultimately governed only by its linear part. To get to this result, we first need to introduce the concept of asymptotic equivalence between differential equations. Consider the following two systems of n equations

| 12a |

| 12b |

both defined on where is a matrix, and are vectors of n components and is a continuous vector-valued function. Following (Brauer 1962, Section 2), we say that these two systems are asymptotically equivalent if for every solution of Eq. (12a) there exists a solution of Eq. (12b) such that

| 13 |

and, conversely, for every solution of Eq. (12b) there exists a solution of Eq. (12a) such that Eq. (13) holds.

To establish asymptotic equivalence between Eq. (12a) and Eq. (12b), we will use a result from (Yakubovich 1951, Theorem 2), which we present without proof in the form found in (Brauer 1962, Theorem 6),

Theorem 1

(Yakubovich) Let be the largest among the real parts of the eigenvalues of . Let m be the largest algebraic multiplicity of the eigenvalues of that have real part . Let q be the largest algebraic multiplicity of any eigenvalue of with real part equal to 0 with in case no eigenvalue of has real part equal to 0. If there is a function such that and

| 14 |

then Eq. (12a) and Eq. (12b) are asymptotically equivalent.

When Eq. (12a) and Eq. (12b) are asymptotically equivalent, the former system, which is possibly nonlinear, can be seen as a perturbed version of the latter, linear system where the perturbation becomes eventually irrelevant. The notion of asymptotic equivalence is particularly useful when stability properties of a nonlinear system are difficult to obtain, yet it can be shown that the system asymptotically behaves as a linear system that is hopefully easier to analyze (Brauer 1962, Section 4.1). Asymptotic equivalence means that one can always find solutions of the two systems such that is o(1). However, this notion is limited in that it does not directly yield quantitative estimates of the error term and of how fast this goes to 0. Explicit estimates for the difference between the fundamental matrices of two asymptotically equivalent systems in the special case in which is linear are derived in (Bodine and Lutz 2010).

Main Result

We consider the following two systems:

| 15a |

| 15b |

defined on , where Eq. (15a) is our model in Eq. (1) and Eq. (15b) is a system corresponding to the sole linear part of our model. Our aim is to provide a sufficient condition for the asymptotic equivalence between Eq. (15a) and Eq. (15b). To this aim, we first establish the following preliminary result:

Proposition 1

has an eigenvalue equal to 0 and no eigenvalue of has real part larger than 0.

Proof

Eq. (7) shows that 0 is an eigenvalue of with corresponding left eigenvector . By Gers̆gorin theorem (Horn and Johnson 2013, Corollary 6.1.3), all eigenvalues of are in the union of the closed disks centered at () with radius . By assumption, every column of contains non-negative non-diagonal entries that add up to minus the diagonal entry in that column. Every Gers̆gorin’s disk of then has its center on the non-negative part of the real axis of the complex plane and all circles enclosing the disks pass through the origin. Hence, the real part of every eigenvalue of is at most 0.

We can now state our main result:

Theorem 2

If there exists a function h of N that is positive and differentiable on and solves the following differential equation,

| 16 |

where C is a positive constant, then the system in Eq. (15a) and the system in Eq. (15b) are asymptotically equivalent.

Proof

Suppose h exists. Let

| 17 |

which is positive on . Differentiating this equation with respect to time while using Eqs. (2), (5) and (11),

| 18 |

Solving this differential equation and then using Eq. (6), we obtain a differential inequality,

| 19 |

The dynamics of N in Eq. (15a) are bounded with for all , see Eq. (10). By the extreme value theorem, the continuous functions h(N) and V(N) achieve maximal values and , respectively, on . With these bounds, the inequality in Eq. (19) and the definition of V we can bound the nonlinear part of Eq. (15a),

| 20 |

We can now invoke Theorem 1 and the notation therein. Let , and so that, by Eq. (20), . By Proposition (1), we have , and . Then, is a non-negative integer with maximum value . Substituting in Eq. (14), the improper integral therein converges

| 21 |

where is the gamma function and the solution of the integral on the right-hand side of the first line of this equation is found in (Gradshteyn et al. 2014, 2.325 6). Therefore, the system in Eq. (15a) and the system in Eq. (15b) are asymptotically equivalent.

A corollary of Theorem 2 is that there is a unique, stable equilibrium of the dynamics of N on . Since and , the function g has at least one root in the interior of this interval so that . If h exists as specified in Theorem 2, then Eq. (16) at reduces to . Since both C and are positive, is negative for every root of g. But continuity of g implies that there cannot be more than one such root. This proves the corollary. It can also be shown that is attracting on because, as Eqs. (18-20) show, as , and, by Eq. (17), if and only if , but if and only if . This corollary reveals a limitation of Theorem 2: it does not apply when g in our model in Eq. (1) has more than one root (Fig. 1).

A further corollary is the existence of a carrying simplex defined by the set of population state vectors with 1-norm equal to . If the function h exists as specified in Theorem 2, then on the simplex the nonlinear part of the system in Eq. (1) vanishes (because the function g does) and only the linear system in Eq. (15b) is left. The simplex is positively invariant for this linear system because its dynamics preserve the 1-norm: by Eq. (7), .

Application to Nonlinear Dynamics of Cancer Growth

Table 1 shows that Theorem 2, despite the limitations stated in the previous section, is general enough to apply to the three main forms of nonlinear dynamics that are usually believed to govern the growth of cancer cells populations (Spratt et al. 1993; Gerlee 2013; Benzekry et al. 2014; Hartung et al. 2014; Sarapata and Pillis 2014; Diebner et al. 2018; Vaghi et al. 2020): generalized logistic growth, generalized Gompertz growth and generalized von Bertalanffy growth. The corollary to this theorem ensures that the cancer cell population will approach the equilibrium size with for generalized logistic and Gompertz growth and for generalized von Bertalanffy growth.

Table 1.

Common nonlinear growth dynamics for cancer cell populations accommodated by the proposed model

| Growth dynamics | g(N) | h(N) | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized logistic growth | |||

| Generalized Gompertz growth | 1 | ||

| Generalized von Bertalanffy growth |

K, , v and w are positive parameters. Within each row, the functions g and h along with the constant C solve the differential Eq. (16)

Discussion

A corollary of our main result (Theorem 2) is the existence of a carrying simplex, where only the linear dynamics of the model in Eq. (1) persist while the nonlinear dynamics vanish. This suggests two separate considerations:

The first consideration has to do with time-scale separation. We may hypothesize that the nonlinear part of our system vanishes faster than the linear part as the carrying simplex is approached so that the system quickly reduces to its linear part. While working with multiple time scales is an effective approach in the analysis of differential equations (Kuehn 2015), a strength of our results is their independence of the existence of a time-scale separation between the nonlinear part and the linear part of Eq. (1). To understand why, suppose we replace with , for some , in the linear part of Eq. (1). Changing the value of we can arbitrarily vary the speed of the dynamics of the linear part of the system. Yet, Theorem 2 still holds. This is because if Eqs. (7) and (8) hold for , then equivalent equations hold for and if Proposition 1 holds , then an equivalent proposition holds for because the spectrum of the latter matrix is equal to the spectrum of the former scaled by . We could also independently alter the speed of the nonlinear part of Eq. (15a). After placing an arbitrary positive factor in front of in Eq. (15a), Theorem 2 would still hold with the sole modification that would now appear as a factor on both sides of Eq. (20). But this would not affect the convergence of the integral in Eq. (21). Our main finding in Theorem 2 is then compatible with an intrinsic time-scale separation between the dynamics of the nonlinear part and those of the linear part of the system in Eq. (1). Yet the result is general enough to lead to a positive conclusion about the asymptotic equivalence of our system to its linear part independently of the existence of a time-scale separation and, in case of existence of this separation, independently of which part of the system is faster.

However, asymptotic equivalence is not, in general, independent of how fast the dynamics of the nonlinear part of a system are compared to those of its linear part. In our case, independence derives from the fact that scaling of by a positive factor does not alter the relevant properties of this matrix, in particular those of its spectrum, for Theorem 2 to apply. But looking at the more general Theorem 1 about asymptotic equivalence, if has positive dominant eigenvalue , then scaling of this matrix by implies scaling of this eigenvalue by the same factor. This, in turn, sets conditions (dictated by the term ) on how fast the nonlinear part of Eq. (12a) should vanish so that the integral in Eq. (14) converges and one can establish asymptotic equivalence between Eqs. (12a) and (12b).

The second consideration relates to the work of Smale (Smale 1976), who proved that an arbitrary dynamical system in dimensions can be embedded in a competitive system of n species the asymptotic dynamics of which are restricted to a -dimensional carrying simplex. Species dynamics on this carrying simplex would then be fully governed by the embedded system. By identifying species as cell types, Smale’s result suggests an approach alternative to ours to combine growth dynamics of, and transition dynamics within, cell populations that also allows one to ultimately neglect growth dynamics and exclusively focus on transition dynamics. Only looking at the nonlinear part of Eq. (1), growth dynamics as specified in Table 1 can in fact be employed to define a competitive system with a carrying simplex. Transition dynamics of cells could then be embedded in the competitive system as opposed to added to it as in our Eq. (1).

However, Smale’s construction requires the dynamics of the embedded system to be “small", for otherwise the system may fail to be competitive. An advantage of our framework is that this restriction is not required. On the other hand, an approach based on Smale’s construction can be more flexible than ours in accommodating nonlinear aspects of cancer dynamics other than cell-type specific growth rates. In modeling cancer cell populations, it is common to postulate interactions among cells. Lotka-Volterra equations (Hofbauer and Sigmund 1998, Section 5.1) define a nonlinear system that has been shown to aptly capture interactions between healthy and cancerous cells (Foryś 2009; Grigorenko et al. 2020) and between cancer cells (Freischel et al. 2021; Cho et al. 2023; Gérard et al. 2024). Competitive Lotka-Volterra equations with a carrying simplex easily lend themselves to (and, in fact, were an inspiration for) Smale’s construction. It is unclear to us, instead, how interactions of the Lotka-Volterra type could be included in the nonlinear part of an equation like Eq. (12a) while ensuring asymptotic equivalence of this to its linear part.

Finally, we would like to recall the motivating factor behind our work: the success of linearity assumptions in modeling experimental data of transitions among cancer cell types (Gupta et al. 2011; Pisco et al. 2013; Su et al. 2017; Risom et al. 2018; Dirkse et al. 2019; Najafi et al. 2023) in the face of nonlinearities inherent to the growth dynamics of cancer. We believe that our results, despite their stated limitations, suggest a possible explanation for this success.

Author Contributions

S.S., M.R., S.G. and A.T. conceived the model. S.G. analyzed the model and wrote the manuscript with feedback from S.S., M.R. and A.T.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors acknowledge the Max Planck Society for funding.

Data Availibility

There are no data or code associated with this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no Conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Alizadeh AA, Aranda V, Bardelli A, Blanpain C, Bock C, Borowski C, Caldas C, Califano A, Doherty M, Elsner M, Esteller M, Fitzgerald R, Korbel JO, Lichter P, Mason CE, Navin N, Pe’er D, Polyak K, Roberts CWM, Siu L, Snyder A, Stower H, Swanton C, Verhaak RGW, Zenklusen JC, Zuber J, Zucman-Rossi J (2015) Toward understanding and exploiting tumor heterogeneity. Nat Med 21:846–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzekry S, Lamont C, Beheshti A, Tracz A, Ebos JML, Hlatky L, Hahnfeldt P (2014) Classical mathematical models for description and prediction of experimental tumor growth. PLoS Comput Biol 10:e1003800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobadilla AVP, Carraro T, Byrne HM, Maini PK, Alarcón T (2019) Age structure can account for delayed logistic proliferation of scratch assays. Bull Math Biol 81:2706–2724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine S, Lutz DA (2010) Asymptotic Integration of Differential and Difference Equations. Springer, Cham [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher M, Dingli D, Werner B, Traulsen A (2018) Replicative cellular age distributions in compartmentalised tissues. J R Soc Interface 15(145):20180272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer F (1962) Asymptotic equivalence and asymptotic behaviour of linear systems. Mich Math J 9:33–43 [Google Scholar]

- Brauer F, Nohel JA (1989) The qualitative theory of ordinary differential equations - An introduction. Dover Publications Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Lewis AL, Storey KM, Byrne HM (2023) Designing experimental conditions to use the Lotka-Volterra model to infer tumor cell line interaction types. J Theor Biol 559:111377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derényi I, Szöllősi GJ (2017) Hierarchical tissue organization as a general mechanism to limit the accumulation of somatic mutations. Nat Commun 8:14545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diebner HH, Zerjatke T, Griehl M, Roeder I (2018) Metabolism is the tie: The bertalanffy-type cancer growth model as common denominator of various modelling approaches. Biosystems 167:1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingli D, Traulsen A, Pacheco JM (2007) Compartmental architecture and dynamics of hematopoiesis. PLoS ONE 4:e345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirkse A, Golebiewska A, Buder T, Nazarov PV, Muller A, Poovathingal S, Brons NHC, Leite S, Sauvageot N, Sarkisjan D, Seyfrid M, Fritah S, Stieber D, Michelucci A, Hertel F, Herold-Mende C, Azuaje F, Skupin A, Bjerkvig R, Deutsch A, Voss-Böhme A, Niclou SP (2019) Stem cell-associated heterogeneity in glioblastoma results from intrinsic tumor plasticity shaped by the microenvironment. Nat Commun 10:1787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freischel AR, Damaghi M, Cunningham JJ, Ibrahim-Hashim A, Gillies RJ, Gatenby RA, Brown JS (2021) Frequency-dependent interactions determine outcome of competition between two breast cancer cell lines. Sci Rep 11:4908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari C, Beccuti M, Lanzardo S, Conti L, Balbo G, Cavallo F, Calogero RA, Cordero F (2014) A mathematical-biological joint effort to investigate the tumor-initiating ability of cancer stem cells. PLoS Comput Biol 9:e106193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foryś U (2009) Multi-dimensional Lotka-Volterra systems for carcinogenesis mutations. Math Method Appl Sci 32:2287–2308 [Google Scholar]

- Gérard A-L, Owen RS, Dujon AM, Roche B, Hamede R, Thomas F, Ujvari B, Siddle HV (2024) In vitro competition between two transmissible cancers and potential implications for their host, the Tasmanian devil. Evol Appl 17:e13670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlee P (2013) The model muddle: in search of tumor growth laws. Cancer Res 73(8):2407–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigorenko NL, Khailov EN, Grigorieva EV, Klimenkova AD (2020) Optimal strategies in the treatment of cancers in the Lotka-Volterra mathematical model of competition. Proc Steklov Inst Math 313(Supp.1):S100–S116

- Gradshteyn IS, Ryzhik IM (2014) Table of Integrals, Series, and Products. Academic Press, Burlington MA

- Gupta PB, Fillmore CM, Jiang G, Shapira SD, Tao K, Kuperwasser C, Lander ES (2011) Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell 146(4):633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung N, Mollard S, Barbolosi D, Benabdallah A, Chapuisat G, Henry G, Giacometti S, Iliadis A, Ciccolini J, Faivre C, Hubert F (2014) Mathematical modeling of tumor growth and metastatic spreading: validation in tumor-bearing mice. Can Res 74:6397–6407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer J, Sigmund K (1998) Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK [Google Scholar]

- Horn RA, Johnson CR (2013) Matrix Analysis. Cambridge University Press, New York, 2nd edition

- Jin W, Shah ET, Penington CJ, McCue SW, Maini PK, Simpson MJ (2017) Logistic proliferation of cells in scratch assays is delayed. Bull Math Biol 79:1028–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KE, Howard G, Mo W, Strasser MK, Lima EABF, Huang S, Brock A (2019) Cancer cell population growth kinetics at low densities deviate from the exponential growth model and suggest an allee effect. PLoS Biol 17:e3000399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleppe M, Levine R (2014) Tumor heterogeneity confounds and illuminates: assessing the implications. Nat Med 20:342–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol JA, Falls TJ, Schnitzer JE (2020) Different ode models of tumor growth can deliver similar results. BMC Cancer 20:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozusko F, Chen P, Grant SG, Day BW, Panetta JC (2001) A mathematical model of in vitro cancer cell growth and treatment with the antimitotic agent curacin a. Math Biosci 170:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn C (2015) Multiple Time Scale Dynamics. Springer Press, Cham [Google Scholar]

- Ledzewicz U, Schättler H (2007) Optimal controls for a model with pharmacokinetics maximizing bone marrow in cancer chemotherapy. Math Biosci 206:320–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Thirumalai D (2022) A mathematical model for phenotypic heterogeneity in breast cancer with implications for therapeutic strategies. J R Soc Interface 19(186):20210803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magni P, Simeoni M, Poggesi I, Rocchetti M, De Nicolao G (2006) A mathematical model to study the effects of drugs administration on tumor growth dynamics. Math Biosci 200:127–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGranahan N, Swanton C (2017) Clonal heterogeneity and tumor evolution: past, present, and the future. Cell 168:613–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michelson S, Leith JT (1993) Growth factors and growth control of heterogeneous cell populations. Bull Math Biol 55:993–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michor F, Hughes TP, Iwasa Y, Branford S, Shah NP, Sawyers CL, Nowak MA (2005) Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature 435:1267–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi A, Jolly MK, George JT (2023) Population dynamics of emt elucidates the timing and distribution of phenotypic intra-tumoral heterogeneity. iScience 26:106964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak MA (2006) Evolutionary dynamics: Exploring the equations of life. Harvard University Press

- Panetta JC (1997) A mathematical model of breast and ovarian cancer treated with paclitaxel. Math Biosci 146:89–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panetta JC, Adam J (1995) A mathematical model of cycle-specific chemotherapy. Math Comput Model 22:67–82 [Google Scholar]

- Panetta JC, Evans WE, Cheok MH (2006) Mechanistic mathematical modelling of mercaptopurine effects on cell cycle of human acute lymphoblastic leukaemia cells. Br J Cancer 94:93–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er D, Ogawa S, Elhanani O, Keren L, Oliver TG, Wedge D (2021) Tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Cell 39:1015–1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai M, Hojel E, Jolly MK, Goyal Y (2023) Unraveling non-genetic heterogeneity in cancer with dynamical models and computational tools. Nature Computational Science 3:301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisco AO, Brock A, Zhou J, Moor A, Mojtahedi M, Jackson D, Huang S (2013) Non-darwinian dynamics in therapy-induced cancer drug resistance. Nat Commun 4:2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raatz M, Shah S, Chitadze G, Brüggemann M, Traulsen A (2021) The impact of phenotypic heterogeneity of tumour cells on treatment and relapse dynamics. PLoS Comput Biol 17(2):e1008702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, Aasen T, De Mattos-Arruda L, Diaz-Cano SJ, Hernández-Losa J, Castellví J, (2020) Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med 98:161–177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Risom T, Langer EM, Chapman MP, Rantala J, Fields AJ, Boniface C, Alvarez MJ, Kendsersky ND, Pelz CR, Johnson-Camacho K, Dobrolecki LE, Chin K, Aswani AJ, Wang NJ, Califano A, Lewis MT, Tomlin CJ, Spellman PT, Adey A, Gray JW, Sears RC (2018) Differentiation-state plasticity is a targetable resistance mechanism in basal-like breast cancer. Nat Commun 9:3815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy T, Ghosh S, Saha B, Bhattacharya S (2022) A noble extended stochastic logistic model for cell proliferation with density-dependent parameters. Sci Rep 12:8998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo S, Mishra A, Kaur H, Hari K, Muralidharan S, Mandal S, Jolly MK (2021) A mechanistic model captures the emergence and implications of non-genetic heterogeneity and reversible drug resistance in er+ breast cancer cells. NAR Cancer 3:zcab027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarapata EA, Pillis LG (2014) A comparison and catalog of intrinsic tumor growth models. Bull Math Biol 76:2010–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S, Philipp L-M, Giaimo S, Sebens S, Traulsen A, Raatz M (2023) Understanding and leveraging phenotypic plasticity during metastasis formation. npj Systems Biology and Applications 9:48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni M, Magni P, Cammia C, De Nicolao G, Croci V, Pesenti E, Germani M, Poggesi I, Rocchetti M (2004) Predictive pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of tumor growth kinetics in xenograft models after administration of anticancer agents. Can Res 64:1094–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smale S (1976) On the differential equations of species in competition. J Math Biol 3(1):5–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spratt JA, Von Fournier D, Spratt JS, Weber EE (1993) Decelerating growth and human breast cancer. Cancer 71:2013–2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Wei W, Robert L, Xue M, Tsoi J, Garcia-Diaz A, Homet Moreno B, Kim J, Ng RH, Lee JW, Koya RC, Comin-Anduix B, Graeber TG, Ribas A, Heath JR (2017) Single-cell analysis resolves the cell state transitionand signaling dynamics associated with melanomadrug-induced resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci 114:13679–13684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaghi C, Rodallec A, Fanciullino R, Ciccolini J, Mochel JP, Mastri M, Poignard C, Ebos JML, Benzekry S (2020) Population modeling of tumor growth curves and the reduced gompertz model improve prediction of the age of experimental tumors. PLoS Comput Biol 16:e1007178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner B, Dingli D, Lenaerts T, Pacheco JM, Traulsen A (2011) Dynamics of mutant cells in hierarchical organized tissues. PLoS Comput Biol 7:12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner B, Dingli D, Traulsen A (2013) A deterministic model for the occurrence and dynamics of multiple mutations in hierarchically organized tissues. J R Soc Interface 10:20130349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakubovich VA (1951) On the asymptotic behavior of the solutions of a system of differential equations. Matematicheskii Sbornik 70:217–240 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Luo Y, Dingli D, Traulsen A (2019) The invasion of de-differentiating cancer cells into hierarchical tissues. PLoS Comput Biol 15:e1007167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Wang Y, Wu B (2014) A multi-phenotypic cancer model with cell plasticity. J Theor Biol 357(21):35–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data or code associated with this manuscript.