Abstract

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the most common types of urogenital cancer. The introduction of immune-based combinations, including dual immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) or ICI plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), has radically changed the treatment landscape for metastatic RCC, showing varying efficacy across different prognostic groups based on the International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium (IMDC) criteria.

Materials and methods

This retrospective multicenter study, part of the ARON-1 project, aimed to evaluate the outcomes of favorable-risk metastatic RCC patients treated with immune-based combinations or sunitinib. Patients were assessed for overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall response rate. We carried out a survival analysis by a Cox regression model.

Results

A total of 524 favorable-risk patients were included in the analysis. After a median follow-up of 37.2 months, the median OS in the overall population was 56.1 months. There was no significant difference in OS between patients receiving sunitinib and those receiving TKI + ICI combinations (p = 0.761). Patients on TKI + ICI had significantly longer PFS compared to patient treated with sunitinib (30.7 vs 22.9 months, p = 0.007). Analysis of OS and PFS based on metastatic site revealed that patients with bone metastases benefited more from ICI plus TKI (56 patients with bone metastases receiving IO + TKI, 38 received pembrolizumab plus axitinib, 15 cabozantinib plus nivolumab and 3 pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib), while sunitinib was more effective for pancreatic and glandular metastases. Additionally, the number of metastatic sites played a role, with TKI plus ICI showing superiority in patients with a single metastatic site. The time from RCC diagnosis to metastatic disease also impacted outcomes, with TKI plus ICI being more effective in patients with a shorter interval (i.e., < 36 months).

Conclusions

The choice between upfront combination or monotherapy for metastatic favorable prognosis RCC remains a current issue. While combination therapy offers prolonged PFS, it does not necessarily translate to improve OS compared to sunitinib. This real-world study supports the superiority in terms of PFS of TKI plus ICI vs TKI monotherapy but not in OS. Probable, other clinical factors should be taking into account to make clinical treatment decisions in this setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00262-024-03897-x.

Keywords: ARON-1 study, Good favorable-risk IMDC criteria, Immunotherapy, Immune-based combinations, Renal cell carcinoma

Patient summary: In this paper, we analyzed favorable-risk prognosis patients in metastatic RCC. This scenario is a complicated one because immunocombinations do not show an OS advantage. We analyze more than 500 patients to provide real-world evidence in this setting to guide clinical decisions in real life.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of the most common types of urogenital cancer, and it presents metastatic disease at diagnosis in 25–30% of cases, with a 5-year mortality rate about 30–40% [1]. First-line treatment of metastatic clear cell RCC (ccRCC) recently witnessed an outstanding revolution, with the introduction of immune-based combinations, where an immune-checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) is combined with either another ICI, or with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) [2–7].

Historically, IMDC criteria classified metastatic RCC into three prognostic groups and response to first-line immune-based combinations seems to be profoundly different among these three groups of patients [8]. In all first-line immune-based combinations studies, prespecified subgroup analyses showed that favorable-risk patients derive no statistically significant overall survival (OS) benefit (either in terms of progression-free survival (PFS) or of OS as compared to sunitinib, in contrast with intermediate- and poor-risk patients where a significant OS benefit is achieved [8, 9]). This difference could lay its rationale in different underlying biology of the three risk groups, as emerging from biomarker analysis [10–12]. Favorable-risk patients seem to present a more angiogenic profile compared to the immunogenic profile of intermediate- and poor-risk patients. Furthermore, at least five of the six individual risk factors which are included into the IMDC model, when present, point toward a state of inflammation; consequently, the lack of these factors underlines a not-inflamed tumor microenvironment where immunotherapy is known to be less effective. Nonetheless, the trials that led to the approval of immune-based combinations were not specifically designed to evaluate survival outcomes depending on the IMDC risk groups; furthermore, the number of favorable-risk patients enrolled in pivotal trials is someway lower than that commonly observed in everyday clinical practice. Thus, no clear conclusions can be drawn on the efficacy of combinations in this population, apart from nivolumab plus ipilimumab that was investigated and approved in intermediate- and poor-risk groups only, having these two subgroups as its target population (although all newcomers were allowed to be enrolled). Nowadays, the combination of pembrolizumab plus axitinib, pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib and nivolumab plus cabozantinib is approved in all risk groups, while TKI monotherapy still remains an option for favorable-risk patients in clinical practice. Unfortunately, no predictive biomarkers are currently available to aid in the clinical strategy decision process [13].

The ARON-1 project (NCT05287464) collects real-world data from multiple oncology centers worldwide with the aim of evaluating outcomes of patients with RCC treated with immune-based combinations [8, 14–16]. In this multicenter retrospective study, we analyzed favorable-risk metastatic RCC patients treated with immune-based combinations or sunitinib, in order to investigate their clinical outcomes. The aim of the present analysis was the comparison between the efficacy observed in patients treated with sunitinib alone and patients treated with a TKI plus ICI combination.

Patients and methods

Study population

We retrospectively collected data from patients aged ≥ 18 years with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of RCC and histologically or radiologically confirmed metastatic disease. We included patients with IMDC favorable-risk criteria treated with first-line TKI plus ICI combinations (January 1, 2016 to October 1, 2023) or sunitinib (January 1, 2008 to January 1, 2017) from 55 centers in 18 countries under ARON-1 trial (NCT05287464).

We retrospectively extracted from patients’ paper and electronic charts data about age, gender, tumor histology, nephrectomy, sites of metastases, type of immunocombination or TKIs and response to therapy according to RECIST 1.1 criteria [17]. Patients with incomplete data on tumor assessment and/or response to therapy were excluded from the ARON-1 study.

First-line therapy was continued until the evidence of clinical and/or radiological tumor progression, unacceptable toxicities or death. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were performed following standard local procedures every 8–12 weeks. Physical and laboratory tests were carried out every 4–6 weeks during patients’ follow-up.

Study endpoints

The primary objective of our retrospective study was to assess the outcome of favorable-risk patients treated with first-line immune-combinations or sunitinib for advanced RCC. Data on tumor response (complete [CR] or partial responses [PR], stable [SD] or progressive disease [PD]) were collected and analyzed. Overall response rate (ORR) was calculated as the sum of CR + PR, while overall clinical benefit (OCB) was calculated as the sum of CR + PR + SD.

OS was calculated from the start of treatment to death for any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the start of first-line therapy to radiological progression assessed by investigator or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Time to second progression (PFS2) was defined as the time from the start of first-line therapy to objective radiological tumor progression on next-line treatment or death from any cause. Duration of response (DoR) was defined as the time from the start of first-line therapy to radiological disease progression or death in patients who achieved CR or PR. Patients without a tumor progression to following line of treatment or death or lost at follow-up at the time of analysis were censored at their last follow-up date.

Statistical analysis

OS, PFS and PFS2 were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method with Rothman’s 95% confidence intervals (CI), and comparisons between survival distributions were led by using the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate analyses were carried out by using Cox proportional hazard models, hazard ratio (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). A survival receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to identify potential cutoffs to better stratify patients in risk groups. The Chi-square test was employed to compare groups for categorical variables. Significance levels were set at a value of 0.05, and all p values were two-sided. The statistical analysis was performed by MedCalc version 19.6.4 (MedCalc Software, Broekstraat 52, 9030 Mariakerke, Belgium).

Results

Study population

We included 3902 patients from the ARON-1 study. Of them, 524 (13%) presented IMDC favorable-risk criteria and were included in this analysis (Figure Supplementary 1); 266 patients (51%) were treated with first-line sunitinib while 258 patients (49%) received first-line immune-based combinations. The median follow-up time was 37.2 months (95%CI 25.0–30.0), in the overall study population, 52.7 months (95%CI 48.2–68.0) in patients treated by sunitinib and 27.7 months (95%CI 15.7–80.7) in those receiving TKI plus ICI, reflecting the evolution of first-line treatment patterns over time.

Median age was 64 years (range 25–88); 75% were males and 25% females. Tumor histology was ccRCC in 461 patients (88%); in the 63 non-clear cell RCC patients, papillary histology was observed in 45 cases and chromophobe RCC in 3 (Table 1); sarcomatoid differentiation was reported in 33 patients (6%). Lung (62%) was the most common metastatic sites. Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics of the overall population are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline patients’ characteristics

| Patients | Overall 524 (%) |

Sunitinib 258 (%) |

TKI plus ICI 266 (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 393 (75) | 198 (77) | 195 (73) | 0.515 |

| Female | 131 (25) | 60 (23) | 71 (27) | |

| Age, years (y) | 64 | 65 | 64 | – |

| Range | 29–88 | 34–88 | 29–87 | |

| Past nephrectomy | 508 (97) | 252 (98) | 256 (96) | 0.408 |

| Clear cell histology | 461 (88) | 221 (86) | 240 (90) | 0.385 |

| Sarcomatoid differentiation | 33 (6) | 21 (8) | 12 (5) | 0.391 |

| Common sites of metastasis | ||||

| Lung | 324 (62) | 159 (61) | 165 (62) | 0.885 |

| Bone | 105 (20) | 49 (19) | 56 (21) | 0.724 |

| Liver | 67 (13) | 40 (16) | 27 (10) | 0.208 |

| Brain | 24 (5) | 14 (5) | 10 (4) | 0.734 |

| Pancreas | 60 (11) | 29 (11) | 31 (12) | 0.825 |

| Glandular | 98 (19) | 40 (16) | 58 (22) | 0.281 |

| First-line therapy | ||||

| Sunitinib | 258 (49) | 258 (100) | – | – |

| Pembrolizumab plus axitinib | 187 (36) | – | 187 (70) | |

| Nivolumab plus cabozantinib | 54 (10) | – | 54 (20) | |

| Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib | 25 (5) | – | 25 (10) | |

| Second-line therapies | 230 (44) | 149 (58) | 77 (29) | < 0.001 |

| Type of second-line therapy | ||||

| Cabozantinib | 89 (17) | 42 (16) | 47 (18) | – |

| Nivolumab | 40 (8) | 40 (16) | 0 (0) | |

| Everolimus | 33 (6) | 31 (12) | 2 (1) | |

| Axitinib | 20 (4) | 14 (5) | 6 (2) | |

| Sorafenib | 17 (3) | 17 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Clinical trials | 12 (2) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) | |

| Sunitinib | 7 (1) | 0 (0) | 7 (3) | |

| Lenvatinib/everolimus | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) | |

| Other | 3 (< 1) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | |

Bold values indicate the stadistical significance

Survival analysis

In the overall study population, median OS was 56.1 months (95%CI 51.8–97.8), while it was not reached in patients receiving both sunitinib and IO + TKI (p = 0.761, Fig. 1), without significant differences in terms of 1-year or 2-year OS rates between the two first-line subgroups (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival and progression-free survival in favorable-risk RCC patients treated by IO + TKI or sunitinib

Table 2.

1-year and 2-year overall survival rates (%) by type of first-line therapy

| Patients | Sunitinib % | TKI plus ICI % | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall study population | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 96 | 95 | 0.734 |

| 2-year OS rate | 88 | 88 | 1.000 |

| Lung metastases | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 97 | 95 | 0.472 |

| 2-year OS rate | 89 | 88 | 0.825 |

| Bone metastases | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 94 | 96 | 0.518 |

| 2-year OS rate | 82 | 92 | 0.036 |

| Liver metastases | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 93 | 86 | 0.107 |

| 2-year OS rate | 78 | 69 | 0.150 |

| Pancreatic metastases | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 100 | 93 | 0.007 |

| 2-year OS rate | 99 | 91 | 0.010 |

| Glandular metastases | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 100 | 94 | 0.013 |

| 2-year OS rate | 97 | 84 | 0.002 |

| 1 site of metastasis | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 99 | 98 | 0.562 |

| 2-year OS rate | 93 | 92 | 0.789 |

| > 1 site of metastasis | |||

| 1-year OS rate | 94 | 93 | 0.755 |

| 2-year OS rate | 85 | 85 | 1.000 |

Bold values indicate the stadistical significance

The median PFS in the overall study population was 28.6 months (95%CI 23.5–81.9) and was significantly longer in patients treated by TKI plus ICI (30.7 months, 95%CI 28.1–35.0 vs 22.9 months, 95%CI 19,7–81,9, p = 0.007, Fig. 1).

When we analyzed patients’ outcome depending on metastatic sites, no significant OS differences between patients receiving sunitinib or TKI plus ICI were found in patients with lung (56.1 months, 95%CI 50.7–97.8 vs NR, 95%CI NR–NR, p = 0.985), bone (51.8 months, 95%CI 40.7–97.8 vs NR, 95%CI NR–NR, p = 0.475), liver (47.8 months, 95%CI 30.1–56.1 vs NR, 95%CI NR–NR, p = 0.596), brain (73.9 months, 95%CI 19.8–97.8 vs NR, 95%CI NR–NR, p = 0.282), pancreatic (65.8 months, 95%CI 57.4–73.9 vs 28.9 months, 95%CI 28.9–28.9, p = 0.102) or glandular metastases (59.2 months, 95%CI 48.5–73.9 vs NR, 95%CI NR–NR, p = 0.354). The 2-year OS rate was significantly higher in patients with bone metastases treated by TKI plus ICI vs sunitinib (92% vs 82%, p = 0.036, Table 2), while sunitinib was associated with higher 1-year and 2-year OS rates in both patients with pancreatic (100% vs 93%, p = 0.007 and 99% vs 91%, p = 0.010, Table 2) or glandular metastases (100% vs 94%, p = 0.013 and 97% vs 84%, p = 0.002, Table 2).

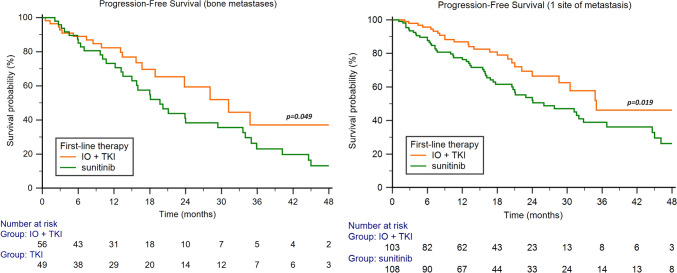

The median PFS was significantly longer with TKI plus ICI in patients with bone metastases (31.2 months, 95%CI 18.9–34.8, vs 19.7 months, 95%CI 13.5–33.6, p = 0.049, Fig. 2), while no significant differences were found in patients with lung (30.7 months, 95%CI 24.0–35.0, vs 23.5 months, 95%CI 18.1–81.9, p = 0.099), liver (13.4 months, 95%CI 3.0–30.5, vs 22.5 months, 95%CI 13.0–35.0, p = 0.101), brain (30.7 months, 95%CI 9.0–30.7, vs 22.5 months, 95%CI 5.0–51.3, p = 0.424), pancreatic (28.3 months, 95%CI 28.3–28.3, vs 33.6 months, 95%CI 17.3–41.3, p = 0.577) or glandular metastases (28.3 months, 95%CI 18.9–32.5, vs 33.6 months, 95%CI 18.3–38.4, p = 0.377).

Fig. 2.

Progression-free survival in favorable-risk RCC patients treated by IO + TKI or sunitinib based on metastatic site and number of sites

The best cutoff for the number of metastatic sites was calculated by ROC curve and resulted > 1; 211 patients (40%) presented only 1 metastatic site while 313 patients (60%) reported > 1 metastatic site. No differences between TKI plus ICI and sunitinib were found in terms of median OS in both patients with 1 site (NR, 95%CI NR–NR, vs 62.9 months, 95%CI 52.2–89.8, p = 0.792) versus > 1 site of metastasis (51.6 months 95%CI 36.5 51–6 vs 54.8 months, 95%CI 48.3–97.8, p = 0.789).

The median PFS was longer on patients with 1 site of metastasis receiving TKI plus ICI combination (35.0 months, 95%CI 28.6–35.0, vs 26.0 months, 95%CI 20.5–72.1, p = 0.019, Fig. 2), while no significant differences were observed in patients with > 1 metastatic sites (28.3 months, 95%CI 23.8–32.5, vs 20.4 months, 95%CI 17.9–81.9, p = 0.150).

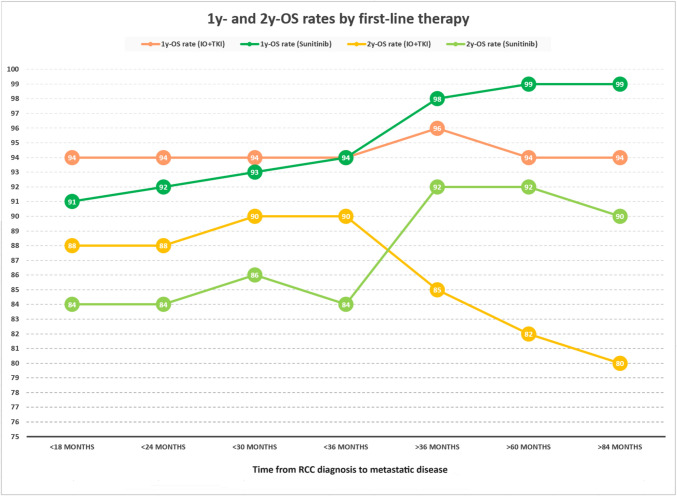

Patients were further stratified based on the time from RCC diagnosis to metastatic disease. Figure 3 illustrates the 1-year and 2-year OS rates of first-line TKI plus ICI and sunitinib according to the time from RCC diagnosis to metastatic disease, showing that the growth of the latter correlates with an increase of patients still alive with TKIs and a reduction of the rates observed with TKI plus ICI (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

1-year and 2-year OS rates according to the time from RCC diagnosis to metastatic disease in favorable-risk patients treated by IO + TKI or sunitinib

Finally, we compared the effectiveness obtained by the three distinct TKI plus ICI combinations. In particular, the 1-year and 2-year OS rates were 91% and 78% in patients treated by pembrolizumab plus axitinib, 100% and 90% with nivolumab plus cabozantinib and 90% and 79% with pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib. The differences were statistically significant in terms of both 1-year (p = 0.006) and 2-year OS rates (p = 0.048) in favor of the nivolumab plus cabozantinib combination.

Response to first-line therapy

In the overall study population, we reported 6% CR, 46% PR, 40% SD and 8% PD. Patients treated by TKI plus ICI showed 9% of CR, 44% PR, 39% SD and 8% PD, while in the sunitinib subgroup we observed 4% of CR, 46% PR, 41% SD and 9% PD. The OCB and ORR were 92% and 53% for IO + TKI and 91% and 50% for sunitinib.

We summarized the responses to therapy in the different RCC subgroups in Table 3. Sunitinib showed better OCB in patients with liver, pancreatic or glandular metastases, while we observed a significant difference in favor of TKI plus ICI in patients with 1 site of metastasis and patients with a time interval between RCC diagnosis and metastatic disease < 36 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Response to first-line therapy in distinct RCC subgroups

| Patients | Overall % | Sunitinib % | TKI plus ICI % | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall study population | ||||

| Complete remission | 6 | 4 | 9 | 0.551 |

| Partial response | 46 | 46 | 45 | |

| Stable disease | 38 | 41 | 38 | |

| Progressive disease | 8 | 9 | 8 | |

| Lung metastases | ||||

| Complete remission | 6 | 3 | 9 | 0.271 |

| Partial response | 49 | 48 | 50 | |

| Stable disease | 37 | 39 | 34 | |

| Progressive disease | 8 | 10 | 7 | |

| Bone metastases | ||||

| Complete remission | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0.187 |

| Partial response | 45 | 46 | 44 | |

| Stable disease | 42 | 46 | 39 | |

| Progressive disease | 9 | 8 | 10 | |

| Liver metastases | ||||

| Complete remission | 5 | 5 | 5 | < 0.001 |

| Partial response | 39 | 45 | 27 | |

| Stable disease | 36 | 39 | 32 | |

| Progressive disease | 20 | 11 | 36 | |

| Pancreatic metastases | ||||

| Complete remission | 12 | 5 | 14 | < 0.001 |

| Partial response | 55 | 59 | 62 | |

| Stable disease | 29 | 36 | 17 | |

| Progressive disease | 4 | 0 | 7 | |

| Glandular metastases | ||||

| Complete remission | 7 | 3 | 11 | 0.021 |

| Partial response | 47 | 54 | 42 | |

| Stable disease | 40 | 41 | 39 | |

| Progressive disease | 6 | 2 | 8 | |

| 1 site of metastasis | ||||

| Complete remission | 8 | 4 | 11 | 0.012 |

| Partial response | 40 | 37 | 43 | |

| Stable disease | 45 | 47 | 43 | |

| Progressive disease | 7 | 12 | 2 | |

| > 1 site of metastasis | ||||

| Complete remission | 6 | 3 | 8 | 0.240 |

| Partial response | 50 | 53 | 46 | |

| Stable disease | 36 | 37 | 34 | |

| Progressive disease | 8 | 7 | 12 | |

| Time to metastases < 36 months | ||||

| Complete remission | 8 | 4 | 12 | 0.040 |

| Partial response | 40 | 43 | 37 | |

| Stable disease | 40 | 36 | 43 | |

| Progressive disease | 12 | 17 | 8 | |

| Time to metastases > 36 months | ||||

| Complete remission | 5 | 4 | 7 | 0.370 |

| Partial response | 51 | 48 | 54 | |

| Stable disease | 39 | 44 | 33 | |

| Progressive disease | 5 | 4 | 6 | |

Bold values indicate the stadistical significance

One-hundred and thirty-eight (52%) and 130 patients (50%) reported CR or PR with TKI plus ICI or sunitinib, respectively. The median DoR was longer in patients receiving TKI plus ICI (NR, NR–NR) vs 31.6 months (95%CI 20.7–81.9, p < 0.001, Figure Supplementary 2).

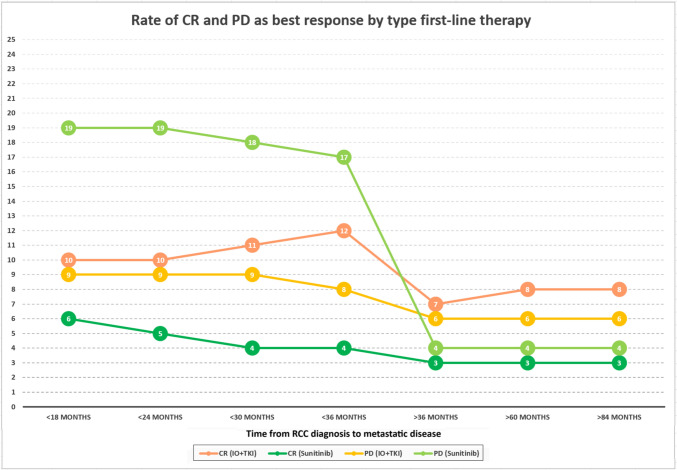

Furthermore, we focused on the rates of CR and PD as best response to first-line therapy based on the time from RCC diagnosis to metastatic disease, showing that patients recurred within 36 months are characterized by -13% of PD with sunitinib and -5% of CR with TKI plus ICI compared to those relapsed over 36 months (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Rate of CR and PD as best response by type first-line therapy

Second-line therapies and PFS2

Ninety-seven patients (37%) progressed during first-line TKI plus ICI; of these, 77 (79%) were fit for second-line treatments. On the other hand, 176 (68%) progressed during first-line sunitinib, whose 149 patients (58%) received second-line therapies, respectively (Table 1).

No differences were found in terms of median PFS2, which was NR (95%CI NR–NR) with TKI plus ICI and 44.1 months (95%CI 36.8–82.3, p = 0.706, Figure Supplementary 3) with sunitinib, as well as comparing 2-year PFS2 rates (70% vs 78%, p = 0.198) and 3y-PFS2 rates (59% vs 60%, p = 0.886).

Univariate and multivariate analyses

At univariate analysis, the presence of liver metastases was the only factor associated with OS (Table 4). As for PFS, non-clear cell histology, the presence of liver metastases and the choice of first-line sunitinib were significantly correlated with worst PFS (Table 4). We further performed univariate and multivariate analyses in patients treated with IO + TKI and in those receiving sunitinib. The results are reported in Table Supplementary 1 and Table Supplementary 2.

Discussion

To clarify whether patients with metastatic RCC initially require combination therapy (TKI plus ICI) or if a therapeutic sequence (i.e., a single-agent TKI followed by an ICI upon progression) may be a reasonable option, remains an open question. Indeed, the data observed in sub-analyses of randomized studies and those obtained through meta-analyses on both pooled and literature data seem to be consistent with each other: for favorable-risk patients the combination of TKI plus ICI offers a clear advantage in terms of PFS, but no advantage in OS compared to monotherapy with TKI (sunitinib) [2–6, 9, 18, 19].

If we leave aside the patients who are not candidates for immunotherapy and who therefore have sunitinib as their main first-line option, the question that arises for oncologists is whether it makes sense in the first-line setting. To offer a combination therapy burdened with more adverse events (as well as economical costs) to achieve a longer disease control (i.e., a longer PFS), despite the comparable OS results that can be achieved through a sequential strategy (i.e., TKI followed by ICI), surely endowed with fewer adverse events (and lesser costs).

In this context, we should also take into account the efficacy results derived from the present study, conducted globally on more than 500 patients. At first glance, our data seem to be consistent with what has already been observed in randomized clinical trials and meta-analyses [2–6, 9, 18, 19]. Specifically, the PFS and DoR were significantly longer in patients treated with TKI plus ICI compared to patients treated with sunitinib, while the PFS2 and OS were comparable in the two groups (Table 2, Table 4, Fig. 1). The combination of nivolumab plus cabozantinib showed higher survival rates at 1 year and 2 year compared to other combinations, a finding to be considered cautiously, although it is in accordance with some recent network meta-analyses [20, 21].

The answer to the above question from the clinician’s point of view does not appear to be trivial. Even though most patients in the favorable prognostic category according to IMDC may achieve long-term survival with the sequential use of a TKI followed by an ICI, some patients may benefit more from the upfront use of an immune-based combination. Our results seem to shed some light on this issue.

Firstly, looking at the site of metastases, we observed significantly better OS and PFS in patients treated with TKI plus ICI compared to those treated with sunitinib in the presence of bone metastases (Figure Supplementary 4). On the other hand, patients treated with sunitinib yielded a better survival and disease control rates compared to those treated with the combination in the case of pancreatic and glandular metastases (Table 2, Figure Supplementary 4). One possible explanation may lie in the fact that pancreatic metastases (and possibly those in glandular sites) are characterized by a more indolent biology, pronounced angiogenesis, contributing to their favorable prognosis and sensitivity to antiangiogenic drugs.

Recent data suggest that metastatic organotropism may indicate a specific inherent biology mechanism of pancreatic metastases with prognostic and treatment implications that may differ from other sites of disease [22].

The number of metastatic sites seems to be another relevant factor, as the benefit in terms of both PFS and response rate for the TKI plus ICI combination in the present study appears to be confined to patients with a single site of metastatic disease, this observation looks not immediately explainable, although the fact that a complete response is more likely in these cases (Fig. 2, Table 3) may account for this finding.

Moreover, the timing of recurrence appears to be another factor to consider. Our results showed that in patients with a time interval between RCC diagnosis and metastatic disease of fewer than 36 months, the use of the TKI plus ICI combination is superior in terms of disease control rate and 1-year and 2-year OS rates compared to sunitinib (Table 3, Fig. 3–4, Table Supplementary 1). Intriguingly, for patients who relapsed beyond 36 months, sunitinib appears to be more effective than the combination (Fig. 3). The time between RCC diagnosis and the appearance of metastases is likely an important indicator of the disease’s biology: it is indirectly estimated within the IMDC prognostic classification through the parameter of the time between diagnosis and the start of systemic treatment. The longer this time (as well as the time to recurrence), the more responsive to angiogenic agents appears to be the disease [23].

Among the study’s limitations, we can recognize its retrospective nature, the different duration of follow-up (longer for the sunitinib-treated group, as expected) and the different proportion of patients who received second-line treatment between the two patient groups (higher in those who received sunitinib). Moreover, the lack of information regarding favorable-risk patients makes it difficult to compare with our results in terms of subgroups analysis.

In conclusion, in this wide real-world population of patients with metastatic RCC with a favorable-risk profile according to IMDC, the superiority of the TKI plus ICI combination over sunitinib is confirmed in terms of PFS but not in terms of OS. Some patients selected by site/number of metastases and interval between the initial diagnosis and recurrence may benefit more from either the combination or sunitinib monotherapy.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors participate in data collection, manuscript writing and revision.

Funding

None to declare.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Javier Molina-Cerrillo declares consultant, advisory or speaker roles for IPSEN, Roche, Pfizer, Sanofi, Janssen and BMS. JMC has received research grants from Pfizer, IPSEN and Roche Francesco Massari has received research support and/or honoraria from Astellas, BMS, Janssen, Ipsen, MSD and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Linda Cerbone has received honoraria for advisory boards, speaker engagements and scientific consultancy for educational purposes from AstraZeneca, EISAI, MSD, Ipsen, BMS, A.A.A.; past MSD employee in Medical Affairs. Ondrej Fiala received honoraria from Novartis, Janssen, Merck and Pfizer for consultations and lectures unrelated to this project. Fernando Sabino M. Monteiro has received research support from Janssen, Merck Sharp Dome and honoraria from Janssen, Ipsen, Bristol Myers Squibb and Merck Sharp Dome, all unrelated to the present paper. R. Kanesvaran has received fees for speaker bureau and advisory board activities from the following companies; Pfizer, MSD, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen, Johnson and Johnson, Merck, Amgen, Astellas and Bayer. Camillo Porta has received honoraria from Angelini Pharma, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eisai, Ipsen and MSD and acted as a Protocol Steering Committee Member for BMS, Eisai and MSD. Sebastiano Buti has received honoraria for speaking at scientific events and advisory roles from AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Merck, Eisai, MSD, Novartis and Pfizer and research funding from Novartis and Pfizer. Matteo Santoni has received research support and honoraria from Janssen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Ipsen, MSD, Astellas, A.A.A. and Bayer, all unrelated to the present paper. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Giandomenico Roviello and Javier Molina-Cerrillo: co-first Authors

Sebastiano Buti and Matteo Santoni: co-Senior Authors

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A (2023) Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin 73(1):17–48. 10.3322/caac.21763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF et al (2018) Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 378(14):1277–1290. 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J et al (2019) Avelumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380(12):1103–1115. 10.1056/NEJMoa1816047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V et al (2019) Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380(12):1116–1127. 10.1056/NEJMoa1816714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY et al (2021) Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384(14):1289–1300. 10.1056/NEJMoa2035716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M et al (2021) Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384(9):829–841. 10.1056/NEJMoa2026982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Massari F, Rizzo A, Mollica V et al (2021) Immune-based combinations for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Eur J Cancer 154:120–127. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santoni M, Buti S, Myint ZW et al (2023) Real-world outcome of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and intermediate- or poor-risk international metastatic renal cell carcinoma database consortium criteria treated by immune-oncology combinations: differential effectiveness by risk group? Eur Urol Oncol 17(1):102–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee D, Gittleman H, Weinstock C et al (2023) A U.S. food and drug administration-pooled analysis of frontline combination treatment survival benefits by risk groups in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 84(4):373–378. 10.1016/j.eururo.2023.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB et al (2018) Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med 24(6):749–757. 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motzer RJ, Robbins PB, Powles T et al (2020) Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in advanced renal cell carcinoma: biomarker analysis of the phase 3 JAVELIN Renal 101 trial. Nat Med 26(11):1733–1741. 10.1038/s41591-020-1044-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer RJ, Banchereau R, Hamidi H, Powles T, McDermott D, Atkins MB, Escudier B, Liu LF, Leng N, Abbas AR, Fan J, Koeppen H, Lin J, Carroll S, Hashimoto K, Mariathasan S, Green M, Tayama D, Hegde PS, Schiff C, Huseni MA, Rini B (2020) Molecular subsets in renal cancer determine outcome to checkpoint and angiogenesis blockade. Cancer Cell 38(6):803-817.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosellini M, Marchetti A, Mollica V, Rizzo A, Santoni M, Massari F (2023) Prognostic and predictive biomarkers for immunotherapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol 20(3):133–157. 10.1038/s41585-022-00676-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santoni M, Massari F, Myint ZW et al (2023) Clinico-Pathological Features Influencing the Prognostic Role of Body Mass Index in Patients With Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma Treated by Immuno-Oncology Combinations (ARON-1). Clin Genitourin Cancer 21(5):309-319.e1. 10.1016/j.clgc.2023.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santoni M, Massari F, Myint ZW et al (2023) Global real-world outcomes of patients receiving immuno-oncology combinations for advanced renal cell carcinoma: the ARON-1 study. Target Oncol 18(4):559–570. 10.1007/s11523-023-00978-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Porta C, Bamias A, Zakopoulou R et al (2023) Geographical differences in the management of metastatic de novo renal cell carcinoma in the era of immune-combinations. Minerva Urol Nephrol 75(4):460–470. 10.23736/S2724-6051.23.05369-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S et al (2016) RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification: from the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer 62:132–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGregor B, Geynisman DM, Burotto M, Suárez C, Bourlon MT, Barata PC, Gulati S, Huo S, Ejzykowicz F, Blum SI, Del Tejo V, Hamilton M, May JR, Du EX, Wu A, Kral P, Ivanescu C, Chin A, Betts KA, Lee CH, Choueiri TK, Cella D, Porta C (2023) A matching-adjusted indirect comparison of nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus pembrolizumab plus axitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol 6(3):339–348. 10.1016/j.euo.2023.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buti S, Petrelli F, Ghidini A, Vavassori I, Maestroni U, Bersanelli M (2020) Immunotherapy-based combinations versus standard first-line treatment for metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Transl Oncol 22(9):1657–1663. 10.1007/s12094-020-02292-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cattrini C, Messina C, Airoldi C, Buti S, Roviello G, Mennitto A, Caffo O, Gennari A, Bersanelli M (2021) Is there a preferred first-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma? A network meta-analysis. Ther Adv Urol 29(13):17562872211053188. 10.1177/17562872211053189.PMID:34733356;PMCID:PMC8558789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bosma NA, Warkentin MT, Gan CL, Karim S, Heng DYC, Brenner DR, Lee-Ying RM (2022) Efficacy and safety of first-line systemic therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol Open Sci 22(37):14–26. 10.1016/j.euros.2021.12.007.PMID:35128482;PMCID:PMC8792068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singla N, Xie Z, Zhang Z, Gao M, Yousuf Q, Onabolu O, McKenzie T, Tcheuyap VT, Ma Y, Choi J, McKay R, Christie A, Torras OR, Bowman IA, Margulis V, Pedrosa I, Przybycin C, Wang T, Kapur P, Rini B, Brugarolas J (2020) Pancreatic tropism of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JCI Insight 5(7):e134564. 10.1172/jci.insight.134564.PMID:32271170;PMCID:PMC7205259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, Eigl BJ, Ruether JD, Cheng T, North S, Venner P, Knox JJ, Chi KN, Kollmannsberger C, McDermott DF, Oh WK, Atkins MB, Bukowski RM, Rini BI, Choueiri TK (2009) Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 27(34):5794–5799. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.