Abstract

Ovarian cancer is a common malignant tumor in women, exhibiting a certain sensitivity to chemotherapy drugs like gemcitabine (GEM). This study, through the analysis of ovarian cancer single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data and transcriptome data post-GEM treatment, identifies the pivotal role of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) in regulating the treatment process. The results reveal that HIF-1α modulates the expression of VEGF-B, thereby inhibiting the fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2)/FGFR1 signaling pathway and impacting tumor formation. In vitro experiments validate the mechanistic role of HIF-1α in GEM treatment, demonstrating that overexpression of HIF-1α reverses the drug's effects on ovarian cancer cells while silencing fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) can restore treatment efficacy. These findings provide essential molecular targets and a theoretical foundation for the development of novel treatment strategies for ovarian cancer in the future.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-024-01723-5.

Keywords: Ovarian cancer, Gemcitabine, Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha, Vascular endothelial growth factor B, Fibroblast growth factor 2, Fibroblast growth factor receptor 1

Introduction

With the continuous advancement of modern medical technology, the incidence of ovarian cancer, a gynecologic malignancy, is increasing annually, posing a challenge in the field of clinical medicine [1–3]. The diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer have long been a focal point for researchers due to its subtle early symptoms, resulting in many patients being diagnosed at advanced stages, thereby complicating treatment [4–6]. As most cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage, the mortality rate is high. Moreover, due to chemotherapy resistance, the recurrence rate of ovarian cancer is also high [7]. Currently, chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine (GEM) are widely utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer due to their high sensitivity toward the disease [8, 9]. However, the precise mechanism of action of GEM remains incompletely elucidated, necessitating further in-depth research [10, 11].

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) is a critical transcription factor that plays a pivotal role in the tumor microenvironment [12, 13]. HIF-1α is involved in regulating cellular metabolism, proliferation, and apoptosis, among other biological processes [14–16]. Tumor angiogenesis plays a critical role in the growth and treatment response of solid tumors [17]. Particularly under hypoxic conditions, the expression of HIF-1α significantly increases, thereby influencing the survival and growth of tumor cells through the regulation of relevant gene expression [14–16]. Studies indicate that HIF-1α is connected to tumor development by promoting the expression of Vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGF-B) and angiogenesis [18, 19]. Therefore, an in-depth exploration of the role of HIF-1α in the treatment of ovarian cancer is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic effects of GEM.

The FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway, as a crucial cell signal transduction pathway, plays a significant role in tumor growth, metastasis, and invasion [20, 21]. Aberrant activation of the FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway is closely associated with the malignancy and prognosis of tumors [21, 22]. Studies have revealed that this pathway interacts with the VEGF-B signaling pathway regulated by HIF-1α, jointly participating in the biological behaviors of tumor cells [23]. Therefore, exploring the mechanism of action of the HIF-1α/VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 network in ovarian cancer treatment holds promise for identifying novel therapeutic strategies.

This study employs multiple methods to delve into the role of HIF-1α in GEM treatment of ovarian cancer. First, we analyzed characteristic genes of ovarian cancer cells using public databases such as GEO and TCGA to identify potential key genes. Then, through high-throughput transcriptomic analysis, we monitored changes in the expression levels of key genes in ovarian cancer cells after treatment, focusing particularly on HIF-1α, VEGFB, FGF2, and FGFR1. In vitro experiments, we validate the impact of GEM on ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through methods like CCK-8, wound healing tests, and Transwell assays. We focus on changes in the expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, FGFR1 proteins, and mRNAs. These experimental designs aid in elucidating the mechanism of action of GEM on ovarian cancer cells, providing a deeper understanding and research foundation for disease treatment.

The ultimate aim of this study is to extensively investigate the mechanism of GEM in ovarian cancer treatment, particularly its impact on the HIF-1α/VEGFB/FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway. The findings of this study are expected not only to provide critical molecular targets for the development of new treatment strategies for ovarian cancer but also to advance personalized and precision therapy, improving patient survival rates and quality of life. These results hold significant clinical implications and scientific value.

Materials and methods

Public data download

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data related to ovarian cancer were obtained from the gene expression omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The dataset GSE217517 encompasses ovarian cancer tumor tissues from 8 ovarian cancer patients (GSM6720925-GSM6720932). The data was analyzed using the R software package "Seurat" [24]. Data quality control was performed based on the criteria of 200 < nFeature_RNA < 5000 percent.mt < 20, and highly variable genes expressing the top 2000 variances were screened. As the data were obtained from a public database, no ethical approval or informed consent was required [25].

Cluster analysis

To reduce the dimensionality of the scRNA-Seq dataset, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed based on the top 2000 highly variable genes by variance. The top 20 principal components (PCs) were selected for downstream analysis using the Elbowplot function in the Seurat software package. The FindClusters function provided by Seurat was employed to identify main cell subgroups, with the resolution set at the default value (res = 1). Subsequently, the UMAP algorithm was utilized to reduce the nonlinear dimensionality of the scRNA-seq sequencing data. Markers for various cell subgroups were identified using the Seurat software package. The cells were annotated by combining known cell lineage-specific marker genes with manual annotations using the CellMarker online tool in conjunction with the "Singel R" package [26]. Cell communication analysis was performed using the "CellChat" package in the R programming language.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

After clustering, the differential feature genes in each cell type were analyzed using the FindAllMarkers function. Specifically, the characteristic genes of epithelial cells or significantly differentially expressed genes (DEGs) from high-throughput transcriptomic data were selected. Subsequently, the co-expressed genes were subjected to gene ontology (GO) functional and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis using the clusterProfiler package in R software. The results were visualized using the ggplot2 package [27].

High-throughput transcriptome sequencing

SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells treated with GEM (cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 1 μM GEM at 37 °C for 5 days) and untreated SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells were collected, with three replicates for each group. A total of at least 1 μg of total RNA was isolated and purified using DNAse I and a silica membrane (RNeasy Kit, 74,004, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA was quantified using the Qubit RNA HS Assay Kit (Q32852, Thermo Fisher, USA) and diluted to 100 ng/μL. The quality of total RNA was confirmed using a Fragment Analyzer (Agilent 5400, USA). Samples with RNA quality ≥ 6 were selected for RNA library preparation in accordance with ISO/IEC-17025 certification (TruSeq RNA Library Preparation Kit v2, RS-122-2302, Illumina, USA). mRNA was enriched and fragmented using oligo(dT) magnetic beads (MS04T, Suzhou Walden Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China), followed by cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification. Paired-end sequencing with read lengths of 126 bp was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 V4 sequencer (Illumina, USA), with each sample generating at least 12.5 Gbp, yielding approximately 50 million read pairs, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Image analysis, base calling, and quality control were carried out using the Illumina data analysis pipeline RTA v1.18.64 and Bcl2fastq v1.8.4. RNAseq reads were provided in compressed Sanger FASTQ format [28]. DEGs were identified from the RNA-Seq dataset using the "edgeR" package in R software, with |logFC|> 2 and P.adjust < 0.05 as the screening criteria.

Analysis of protein–protein interaction (PPI) network

The STRING database (https://string-db.org/) was utilized to annotate the PPI network of DEGs. The data was exported as a TSV file, and genes correlated to candidate genes were selected. Subsequently, visualization was performed using Cytoscape software [29].

Analysis of gene expression in TCGA database

Data for ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma from TCGA and corresponding normal tissue data from GTEx were retrieved from the Xiantao Academic website (TCGA_GTEx-OV). The normal control group included 88 samples, while the tumor tissue group included 427 samples. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, and data visualization was carried out using the ggplot2 package [30].

Correlation analysis

Pairwise correlation analysis was performed on the selected candidate genes from the high-throughput transcriptome data using Spearman correlation analysis. The results were visualized using a heatmap, with correlation coefficients ranging between -1 and 1, indicating the strength and direction of the correlation. The magnitude of the coefficient signifies the degree of correlation [31].

Cell culture and grouping

The human ovarian surface epithelial cells (IOSE-80) were purchased from Pricella (CP-H055). These primary ovarian epithelial cells were cultured in dishes coated with mouse tail collagen I (2–5 μg/cm2). The cells were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, Cat. No: 11875119) containing 10% FBS (12483020, Gibco), 1% glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment and could be passaged for 2–3 generations [32]. The human ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV-3 was obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (TCHu185), and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, CRL-1730 ™ purchased from ATCC, USA) were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (Gibco, Cat. No: 11875119) containing 10% FBS, 1% glutamine, and antibiotics (penicillin, 100 U/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified environment and passaged twice a week [33].

GEM hydrochloride was purchased from MCE (LY 188011) and dissolved in sterile water. SK-OV-3 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Cat. No: 11875119) containing 1 μM GEM at 37 °C for 5 days, with one medium change during the treatment. This group was designated as the SK-OV-3/GEM group [34, 35]. This treatment was used to assess cell proliferation, migration, Transwell invasion, and angiogenesis.

Based on the known HIF-1α, VEGF-B and FGFR1 sequences in NCBI, Shanghai Hanheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) was commissioned to construct oe-NC, oe-HIF-1α, oe-VEGF-B and oe-FGFR1 into the lentiviral vector pHBLV-CMV-MCS-EF1-Puromycin. When SK-OV-3 cells were in the logarithmic growth phase, they were dissociated using trypsin and seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates. After routine incubation for 24 h, when the cell confluence reached around 75%, the medium containing an appropriate amount of packaged lentivirus (MOI = 10, working titer approximately 5 × 106 TU/mL) and 5 μg/mL polybrene (Merck, TR-1003, USA) was added for infection. The titer of lentivirus was 1 × 108 TU/ml.

Subsequently, after 72 h, the medium was replaced with a medium containing 4 μg/mL puromycin (Invitrogen, A1113803), and the cells were cultured for at least 14 days. Puromycin-resistant cells were expanded in a medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin (Invitrogen, A1113803) for 9 days before being transferred to a puromycin-free medium for further cultivation, thereby obtaining SK-OV-3 cells stably overexpressing HIF-1α, VEGF-B or FGFR1[36].

The commercial FGFR1 silencing lentivirus (sc-39840-V) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Shanghai) and titrated to 109 TU/mL. After 72 h of infection, the medium was replaced with a medium containing 4 μg/mL puromycin, and the cells were cultured for at least 14 days. Puromycin-resistant cells were expanded in medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin for 9 days, then transferred to a puromycin-free medium, resulting in a stable FGFR1-silenced cell line. SK-OV-3 cells with stable overexpression of HIF-1α were seeded at a density of 1 × 106 cells per well in a 6-well plate, and after 24 h of incubation, the cells were infected with lentivirus. The next experiment was conducted 72 h post-infection.

Cell groupings were as follows:

Group 1: (1) oe-NC (IOSE-80 cells infected with oe-NC lentivirus); (2) oe-HIF-1α (IOSE-80 cells with stable HIF-1α overexpression); (3) oe-VEGF-B (IOSE-80 cells with stable VEGF-B overexpression); (4) oe-FGFR1 (IOSE-80 cells with stable FGFR1 overexpression).

Group 2: (1) control group (SK-OV-3 cells); (2) GEM group (SK-OV-3 cells treated with GEM); (3) oe-NC + GEM group (oe-NC lentivirus-infected cells treated with GEM); (4) oe-HIF-1α + GEM group (cells with stable HIF-1α overexpression treated with GEM); (5) oe-HIF-1α + sh-FGFR1 + GEM group (cells with stable HIF-1α overexpression infected with sh-FGFR1 lentivirus and treated with GEM).

RT-qPCR analysis

All RNA samples were extracted from cells and tissues using a lysis buffer (Vazyme, R401-01). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from mRNA samples (2 μg) using a reverse transcription system. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the QuantStudio™ 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) by mixing cDNA samples, target gene primers, and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. 1176202K) for quantitative real-time PCR analysis [37]. The primer sequences used in this study are presented in Table S1 (primer designs sourced from Primer Bank).

Western blot (WB)

Cells from each group were collected and lysed on ice for 30 min using RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% PMSF (P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After centrifugation at 14,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, the supernatant was collected. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method (P0012S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). An appropriate amount of 5 × loading buffer was added, and the samples were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min for protein denaturation. A total of 50 μg of protein was loaded per sample. The protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE using a separating gel and a stacking gel. After electrophoresis, the protein bands were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. GAPDH was used as the loading control. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline with Tween (PBST), the membrane was incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody at room temperature. Signal detection was then performed using the ECL detection system (32,209, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and the membrane was exposed using an imaging system (Amersham Imager 600, USA) [38, 39]. Grayscale analysis was conducted using Image J. The experiment was repeated three times. Information on the antibodies used for Western Blot is provided in Table S2.

CCK-8 cell proliferation experiment

The cell proliferation assay was performed using the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) (Beyotime, C0037, Shanghai, China). Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. At Day 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 1 h, and the optical density of the cells was measured at 450 nm [40]. Each group was set up with 6 replicates, and the experiment was repeated thrice.

Wound healing assay

The migration of ovarian cancer cells was evaluated through a scratch closure assay. When cells reached 90% confluence in a 6-well plate, a straight line was drawn through the monolayer using a sterile 200 µL pipette tip. The floating cells were then washed off with PBS, and the original growth medium was replaced with a medium containing 1% fetal bovine serum to inhibit cell proliferation. Images of the scratch were captured at 0 and 24 h post-incision using an inverted microscope (Olympus, Japan), and the wound closure area was quantitatively analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH, USA) to estimate the cell migration ability [40].

Transwell invasion assay

The in vitro cell invasion assay was conducted using Transwell chambers (8 μm pore size; Corning, USA). Matrigel-coated Transwell chambers with 8 μm pores were prepared by adding 600 mL of FBS-containing medium to the lower chamber and incubating at 37 °C for 1 h. Digestion-released cells were resuspended in DMEM medium without FBS, and 2 × 104 cells/mL were seeded into the upper chamber. The chambers were then incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, the Transwell chambers were removed, washed twice with PBS, fixed with 5% glutaraldehyde at 4 °C, stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 5 min, rinsed with PBS, and any surface cells were removed with a cotton swab. Cell invasion was assessed under an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon TE2000, China), where 5 random fields were captured for each chamber, and the average number of cells passing through the chamber was calculated as representative of each group [41]. Each experiment was repeated thrice.

Angiogenesis assay

Angiogenesis was assessed using the Chemicon® In Vitro Angiogenesis Assay Kit (Chemicon International, ECM625) to evaluate blood vessel formation. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were utilized for the experiment following these procedures: ECMatrix™ solution was thawed overnight at 4 °C. 900 μL of the ECMatrix™ solution was mixed with 100 μL of 10 × ECMatrix™ Dilution Buffer in a sterile microcentrifuge tube. Then, 50 μL of the mixture was transferred to each well of a pre-chilled 96-well tissue culture plate and incubated at 37 °C for at least 1 h to allow the matrix solution to solidify. Endothelial cells were harvested and resuspended in the supernatants extracted from ovarian cancer cells of the control group, GEM group, oe-NC + GEM group, oe-HIF-1α + GEM group, and oe-HIF-1α + sh-FGFR1 + GEM group. Cells were seeded onto the polymerized surface of ECMatrix™ at a density of 1.0 × 106 cells per well and then incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. The formation of cellular networks was completed within 18 h, with initial signs visible after 4 h. The process of angiogenesis was observed using an inverted light microscope [42].

Statistical analysis

The data were obtained from at least three independent experiments, and the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD); for comparisons between the two groups, a two-sample independent t-test was employed; for comparisons involving three or more groups; one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. If the ANOVA results indicated significant differences, Tukey's Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc test was performed for further comparisons between groups. For non-normally distributed or unequal variances data, the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis H test was utilized. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software, Inc.) and R language. The significance level for all tests was set at 0.05, with a two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Single-cell sequencing reveals cellular heterogeneity in ovarian cancer tumor tissue

scRNA-seq data of ovarian cancer tumor tissue were downloaded from the GEO database using the GSE217517 chip, which included samples from 8 ovarian cancer patients. The data was integrated using the Seurat package, filtering out cells with nFeature_RNA < 5000, nCount_RNA < 20,000, and percent.mt < 20% (Figure S1A). After removing low-quality cells based on these criteria, a total of 28,451 genes and 60,906 cells were retained for analysis. The correlation analysis of sequencing depth showed a correlation coefficient of r = -0.15 between nCount_RNA and percent.mt, and r = 0.86 between nCount_RNA and nFeature_RNA after data filtering (Figure S1B), indicating the high quality of the filtered cell data for further analysis.

Subsequent to cell filtering, data normalization was performed, followed by analysis of highly variable genes. PCA was applied for linear dimensionality reduction based on these genes, showing the distribution of cells in PC_1 and PC_2 (Figure S1C and Figure S1D). The results revealed the presence of batch effects among the samples.

The sample data underwent batch correction using the Harmony package, and an ElbowPlot was utilized to rank the standard deviation of PCs (Figure S1E). The corrected results indicated the successful elimination of sample batch effects (Figure S2A). Subsequently, non-linear dimensionality reduction was performed on the top 20 PCs using the UMAP algorithm, and clustering profiles at different resolutions were displayed using the cluster package (Figure S2B). Through UMAP clustering analysis, all cells were grouped into 29 cell clusters (Figure S2C).

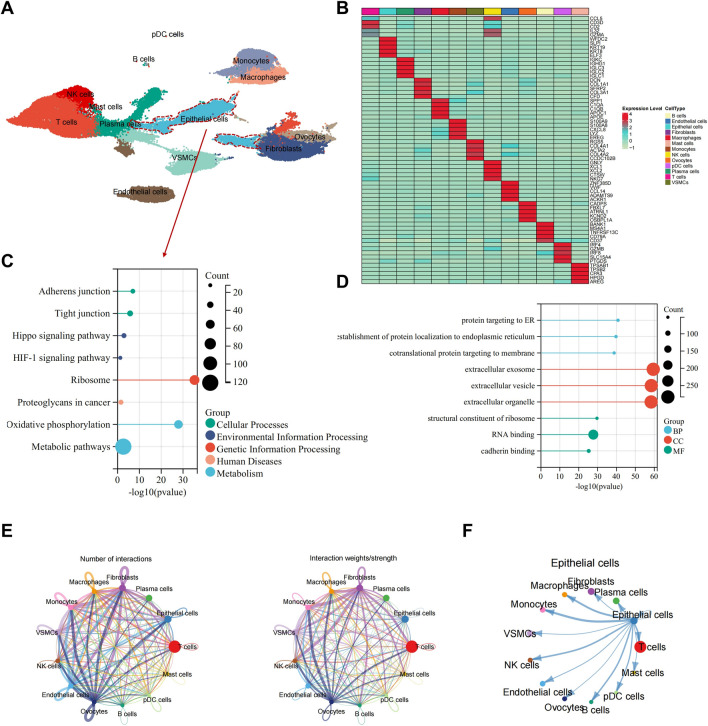

Next, the "SingleR" package from Bioconductor/R software was employed to automatically annotate these 29 cell clusters, resulting in the identification of 13 cell types (Fig. 1A). Additionally, expression heatmaps showcasing the top 5 expressed genes for each of the 13 cell types were displayed, confirming the reliability of the cell clustering (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of ovarian cancer scRNA-seq data based on public databases. A Visualization of cell annotation results grouping on UMAP clustering; B Correlation heatmaps of top five genes in 13 cell types; C, D KEGG E and GO F functional enrichment plots of epithelial cell characteristic genes; E Cell communication network plot in samples, where thickness of lines in the left plot represents the number of pathways, and in the right plot represents interaction strength; F Communication plot between epithelial cells and other cells

A total of 962 DEGs were identified in the epithelial cells using the FindAllMarkers function. Enrichment analysis of these genes revealed significant associations with signaling pathways such as Adherens junction, Tight junction, HIF-1 signaling pathway, and Oxidative phosphorylation in the KEGG analysis (Fig. 1C). Additionally, the GO analysis showed significant associations with processes like protein targeting to ER, extracellular exosome, and RNA binding (Fig. 1D). The "CellChat" R package was utilized to investigate pathway activities between different cells. The intercellular interactions among the 13 cell types were presented, highlighting a significant connections between epithelial cells and all other cell types (Fig. 1E, F).

Through scRNA-seq analysis of ovarian cancer tumor tissue in public databases, we successfully identified 13 cell types, including epithelial (tumor) cells. This discovery lays a foundation for a deeper understanding of the cellular heterogeneity and complexity of ovarian cancer. Our future plans involve leveraging these initial findings to delve into the molecular mechanisms of ovarian cancer epithelial (tumor) cells, aiming to unveil their critical roles in disease treatment.

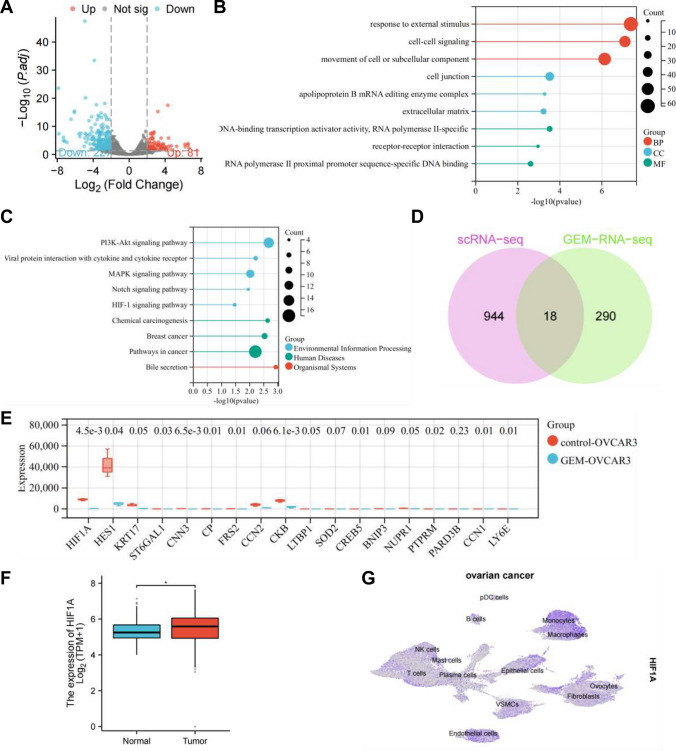

scRNA-seq combined with transcriptome sequencing reveals the key role of HIF-1α in GEM-mediated inhibition of ovarian cancer

As reported in the literature, GEM has been shown to inhibit the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of ovarian cancer cells [43]. To further elucidate the signaling pathway through which GEM exerts its anticancer effects, ovarian cancer cells treated with GEM were subjected to high-throughput sequencing, and the resulting transcriptome count matrix was analyzed using edgeR software, leading to the identification of 308 DEGs, with 227 significantly downregulated and 81 significantly upregulated (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Identification of key genes in high-throughput transcriptome analysis. A Volcano plot of differential analysis, where red indicates significantly upregulated genes, blue indicates significantly downregulated genes, and grey indicates non-significant genes; B, C Enrichment analysis of significant DEGs using GO (B) and KEGG (C); D Venn diagram of differential genes between characteristic genes of epithelial cells in scRNA-seq dataset and high-throughput transcriptome data after GEM treatment; E Boxplots of expression of 18 intersecting genes in the transcriptome dataset; F Boxplot of HIF-1α expression levels in TCGA_GTEx-OV, where * indicates P ≤ 0.05 (TCGA_GTEx-OV dataset: Normal: n = 88, Tumor: n = 427); G UMAP plot of HIF-1α expression in scRNA-seq dataset

Functional enrichment analysis of these 308 DEGs revealed significant associations in GO enrichment analysis. In the biological process (BP) category, terms related to response to external stimulus, cell–cell signaling, and movement of cell or subcellular components were prominently enriched. In the cellular component (CC) category, terms such as cell junction, apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme complex, and extracellular matrix were significantly enriched. Meanwhile, in the molecular function (MF) category, terms including DNA-binding transcription activator activity, RNA polymerase II-specific, receptor-receptor interaction, and RNA polymerase II proximal promoter sequence-specific DNA binding showed significant enrichment (Fig. 2B).

Moreover, KEGG pathway analysis highlighted enrichments in pathways such as PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, MAPK signaling pathway, and HIF-1 signaling pathway (Fig. 2C).

By intersecting the characteristic genes of epithelial cells in the scRNA-seq dataset with the DEGs from the high-throughput transcriptome data of cells treated with GEM, a total of 18 intersecting genes were identified (Fig. 2D). In the high-throughput transcriptome data, the expression levels of 18 intersecting genes were displayed, showing the most significant variation in HIF-1α expression, significantly decreased (Fig. 2E).

Further analysis involved extracting data for ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and corresponding normal tissue data from the Genotype-Tissue Expression Project (GTEx) (TCGA_GTEx-OV). The annotation indicated a significant overexpression of HIF-1α in ovarian cancer tissues (Fig. 2F), which was also widely expressed in the scRNA-seq data set (Fig. 2G).

Interestingly, KEGG enrichment analysis of the characteristic genes of epithelial cells from the scRNA-seq dataset and the DEGs from the high-throughput transcriptome data of GEM-treated cells both exhibited significant enrichment in the HIF-1 signaling pathway. HIF-1α is recognized as a crucial transcription factor in cancer progression and targeted cancer therapy [44], with known roles in promoting ovarian cancer progression [45]. Therefore, this study underscores the significance of HIF-1α as a key gene modulated by GEM in influencing ovarian cancer progression.

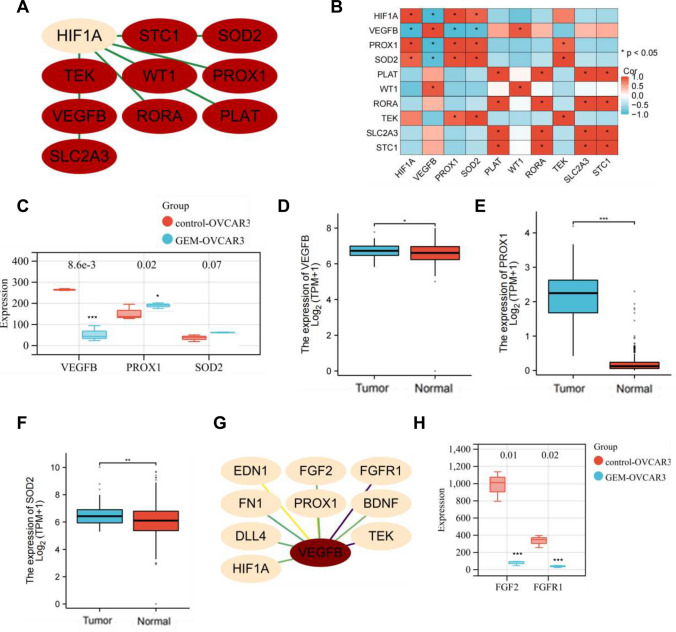

Significant decrease in expression levels of VEGFB, FGF2, and FGFR1 after GEM treatment

In the present analysis, we successfully identified the key gene HIF-1α, which influences the progression of breast cancer in response to GEM. Subsequently, we further analyzed the upstream and downstream signaling pathways. Initially, we identified 9 genes directly interacting with HIF-1α among the DEGs (Fig. 3A). By analyzing the expression matrix of 10 genes using Pearson correlation based on high-throughput transcriptome data, we found that only VEGFB, PROX1, and SOD2 showed significant correlation with HIF-1α (Fig. 3B). Moreover, VEGFB, PROX1, and SOD2 were significantly upregulated in tumors in the GTEx-TCGA dataset, with only VEGFB showing a significant decrease in expression after GEM treatment (Fig. 3C–F). Consequently, we postulate an interaction between VEGFB and HIF-1α.

Fig. 3.

Exploration of the Impact of GEM Treatment on Other Key Genes. A PPI network of genes interacting with HIF-1α among significant DEGs; B Correlation heatmap of genes interacting with HIF-1α; C Boxplots of expression levels of VEGF-B, PROX1, SOD2 (control-OVCAR3, n = 3, GEM-OVCAR3, n = 3); D–F Boxplots of expression levels of VEGF-B (D), PROX1 (E), SOD2 (F) in TCGA_GTEx-OV dataset, where * indicates P < 0.05, ** indicates P < 0.01, *** indicates P < 0.001 (TCGA_GTEx-OV dataset: Normal: n = 88, Tumor: n = 427); (G) PPI network of genes interacting with VEGF-B among significantly DEGs; (H) Boxplots of expression levels of FGF2 and FGFR1 (control-OVCAR3, n = 3, GEM-OVCAR3, n = 3)

Additionally, further analysis revealed an interaction between VEGFB and 9 DEGs (Fig. 3G). The expression levels of FGF2/FGFR1 before and after GEM treatment were also examined, showing a significant reduction in FGF2/FGFR1 expression after GEM treatment (Fig. 3H). Studies have shown that VEGFB induces apoptosis in tumor cells and exhibits anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor activities [46]. In tumor tissues, VEGFB prevents excessive angiogenesis by inhibiting the FGF2/FGFR1 pathway [47].

Thus, it can be preliminarily concluded that GEM alleviates the progression of ovarian cancer by inhibiting the VEGFB-mediated FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway.

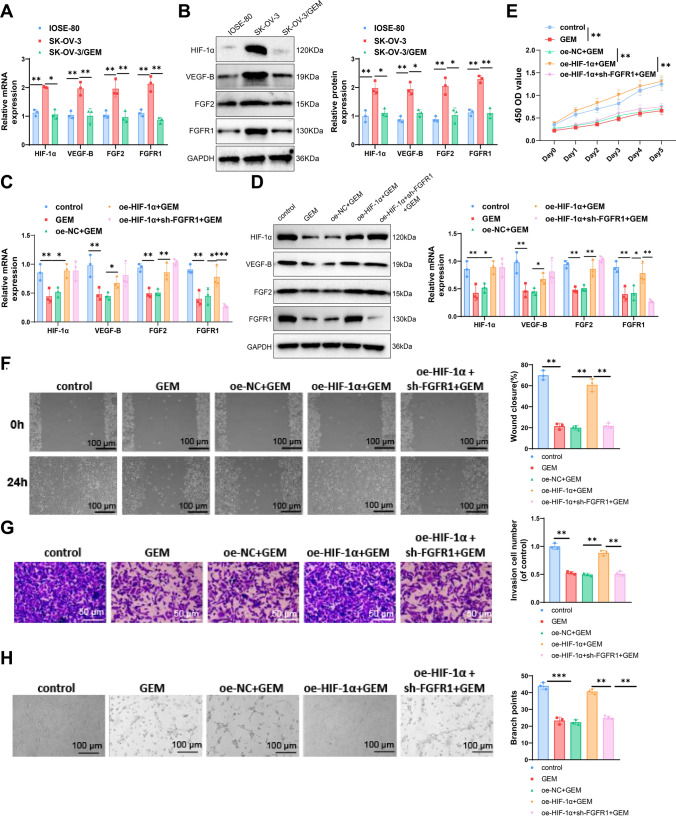

GEM Reduces Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation, Migration, Invasion, and Angiogenesis by Inhibiting the HIF-1α/VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 Signaling Pathway.

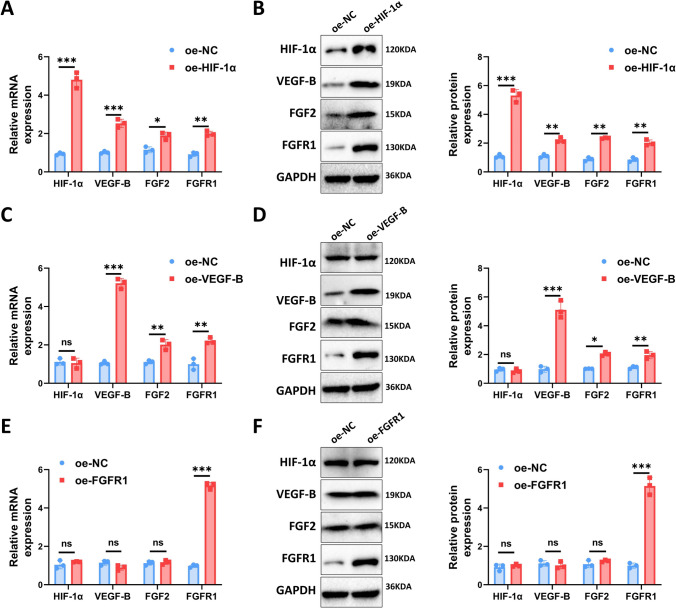

In this figure, we explored the interactions between HIF-1α, VEGF-B, and FGF2/FGFR1 by overexpressing these genes in human ovarian epithelial cells (ISOE-80). Our qPCR and Western blot analyses showed that overexpression of HIF-1α led to significant increases in the expression levels of VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1 (Fig. 4A, B). Interestingly, overexpression of VEGF-B did not affect HIF-1α levels but significantly increased the expression of FGF2 and FGFR1 (Fig. 4C, D). Lastly, overexpression of FGFR1 did not significantly alter the expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, and FGF2, with only FGFR1 itself showing a considerable increase in expression (Fig. 4E, F).

Fig. 4.

Validation of the upstream–downstream relationships of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, and FGF2/FGFR1. A Overexpression of HIF-1α followed by qPCR A and Western blot analysis B to assess the expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1; C Overexpression of VEGF-B followed by qPCR C and Western blot analysis D to evaluate the expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1; E Overexpression of FGFR1 followed by qPCR E and Western blot analysis F to determine the expression levels of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1. Cell experiments were conducted in triplicate. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Therefore, we hypothesized that HIF-1α may be involved in the progression of ovarian cancer by activating the VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway. We selected ISOE-80, the ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV-3, and SK-OV-3/GEM cells treated with 1 μM GEM for three days. IOSE-80 is a normal ovarian epithelial cell line, and we used it as a control for the ovarian cancer cell line SK-OV3 to demonstrate the changes in target gene expression following malignant transformation. Western blot analysis revealed a significant increase in the expression of HIF-1α and VEGF-B in ovarian cancer cells SK-OV-3 compared to ISOE-80 cells. Additionally, in GEM-treated SK-OV-3/GEM cells, the expression of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1 was significantly reduced compared to untreated SK-OV-3 cells (Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 5.

Exploring the molecular mechanisms of Dioscorea nipponica Makino extract on inhibiting the proliferation, migration, invasion capabilities, and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer cells. A, B qPCR and WB analysis of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1 expression levels in ISsh-80, SK-OV-3, and SK-OV-3/GEM cells; C, D qPCR and WB analysis of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1 expression levels in the control (SK-OV-3), GEM, oe-NC + GEM, oe-HIF-1α + GEM, and oe-HIF-1α + sh-FGFR1 + GEM groups; E CCK-8 assay measuring the differences in proliferation across groups; F Scratch assay measuring the differences in migration across groups; G Transwell assay measuring the differences in invasion across groups; H Angiogenesis assay measuring the formation of tubular structures across groups. All experiments were repeated three times. Cell experiments were repeated three times. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

To validate the role of HIF-1α in GEM treatment, SK-OV-3 ovarian cancer cells were divided into control and experimental groups: GEM-treated SK-OV-3 (GEM), overexpressed negative control (oe-NC + GEM), overexpressed HIF-1α (oe-HIF-1α + GEM), and overexpressed HIF-1α with silenced FGFR1 (oe-HIF-1α + sh-FGFR1 + GEM). Western blot analysis showed reduced expression of HIF-1α, VEGF-B, FGF2, and FGFR1 in GEM-treated cells compared to the control. In the oe-HIF-1α + GEM group, these levels increased, while silencing FGFR1 led to a reduction in FGFR1 only (Fig. 5C, D).

CCK-8 assays indicated that GEM treatment reduced cell proliferation compared to the control, while overexpressing HIF-1α increased proliferation compared to oe-NC + GEM. Silencing FGFR1 significantly inhibited this effect (Fig. 5E).

Scratch assays showed reduced migration in GEM-treated cells, while overexpression of HIF-1α enhanced migration compared to oe-NC + GEM. Silencing FGFR1 significantly decreased migration (Fig. 5F). Transwell assays similarly showed reduced invasion in GEM-treated cells, enhanced invasion in the oe-HIF-1α + GEM group, and a decrease following FGFR1 silencing (Fig. 5G).

Angiogenesis assays using HUVECs revealed that GEM inhibited tube formation, while overexpressed HIF-1α promoted it. Silencing FGFR1 significantly reduced this effect (Fig. 5H).

In conclusion, GEM can significantly reduce ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis by inhibiting the HIF-1α/VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway.

Discussion

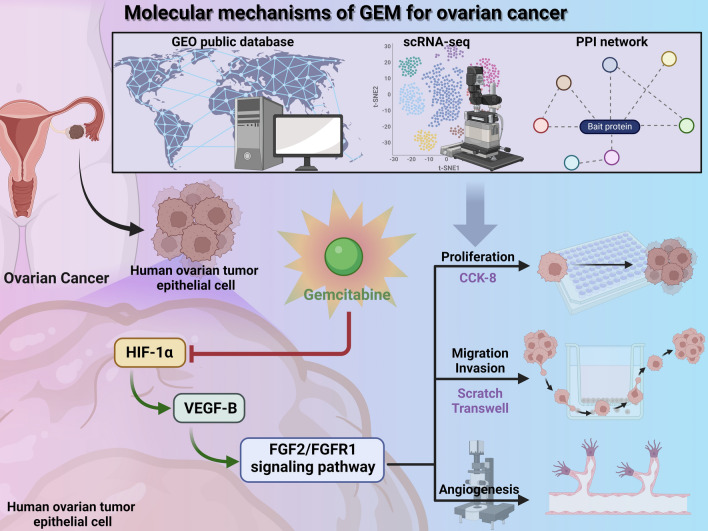

Ovarian cancer is a prevalent and lethal gynecologic malignancy that significantly impacts women's quality of life and health [48]. GEM, a chemotherapy agent, has demonstrated good sensitivity in treating ovarian cancer, making it a commonly used drug in clinical practice [49, 50]. This study aims to investigate the mechanism of action of HIF-1α in the GEM treatment of ovarian cancer, focusing on inhibiting the impact of the FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway on tumors by regulating VEGF-B expression (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Molecular mechanisms of GEM treatment in breast cancer

In this study, ovarian cancer scRNA-seq data were obtained from the TCGA public database for cell-specific gene analysis and GO/KEGG enrichment analysis. Advanced high-throughput transcriptome sequencing analysis techniques were employed to successfully identify the genes in the HIF-1α/VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 network that play a key role in GEM treatment of ovarian cancer. These results provide compelling evidence for further exploring the mechanistic role of this signaling pathway in the development of ovarian cancer.

Compared to previous studies, this research demonstrates significant innovation in cell-specific gene analysis and key network identification [51, 52]. By extensively analyzing scRNA-seq data, the research team not only identified 13 different cell types but also conducted differential gene selection and functional analysis for distinct cell populations, offering more insights into understanding the pathogenesis of ovarian cancer.

This study reveals that HIF-1α influences the activity of the FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway and, consequently, the efficacy of GEM in ovarian cancer cells by modulating the expression levels of VEGF-B. This finding expands the understanding of this signaling pathway in tumor development and provides a theoretical basis for further research and development of therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway.

In vitro experimental results demonstrate that GEM treatment significantly inhibits the proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis of ovarian cancer cells. This aligns with previous research on the mechanism of action of this drug and further confirms the effectiveness of GEM in suppressing tumor growth and angiogenesis [53–55]. Furthermore, this study identifies that the overexpression of HIF-1α can reverse the effects of GEM, offering crucial insights into the mechanisms of tumor resistance in clinical settings.

The role of the HIF-1α/VEGFB/FGF2/FGFR1 network in ovarian cancer treatment has garnered significant attention [18, 19]. HIF-1α, as a key transcription factor, can regulate the expression of VEGFB [56, 57]. VEGF-B can bind to FGFR1, inducing the formation of the FGFR1/VEGFR1 complex, which inhibits FGF2-induced Erk activation, thereby suppressing FGF2-driven angiogenesis and tumor growth [47]. Our study found that the therapeutic effect of GEM is closely associated with the downregulation of HIF-1α, which inhibits the activation of the VEGF-B/FGF2/FGFR1 signaling pathway. Based on this background, we elucidated the molecular mechanisms by which GEM alleviates ovarian cancer progression. The understanding of these molecular mechanisms provides important molecular targets for the development of ovarian cancer treatment strategies and may lead to more effective personalized therapies for patients, improving treatment outcomes and survival rates.

Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) is a heparin-binding growth factor that exists in multiple isoforms depending on the translation initiation site: an 18 kDa cytoplasmic isoform and four larger nuclear isoforms (22, 22.5, 24, and 34 kDa) [58]. Our results indicated that only the 18 kDa cytoplasmic isoform of FGF-2 underwent significant changes. This 18 kDa cytoplasmic isoform of FGF-2 is released from cells and functions by activating FGF receptor tyrosine kinases on the cell surface [59]. This is consistent with our findings regarding the specific regulation of FGFR1 by FGF-2.

However, this study has certain limitations, such as the experimental results being validated only at the in vitro cellular level. Further validation and confirmation in animal models or clinical samples are required. Additionally, the detailed roles of HIF-1α, VEGFB, FGF2, and FGFR1 in ovarian cancer progression need to be further explored to enhance our understanding of the disease mechanisms. Moreover, our conclusions were drawn using a single concentration of GEM and RNAseq analysis performed at a single time point, meaning that variations in GEM concentration and treatment duration may influence the experimental outcomes.

Looking ahead, further exploration of the interactions between HIF-1α and other signaling pathways, as well as personalized treatment strategies in combination with GEM therapy, is warranted. For patients resistant to GEM, the use of FGFR inhibitors such as Futibatinib, Infigratinib, and Dovitinib may restore the efficacy of GEM [60–62]. Continued research holds promise for providing deeper theoretical insights into the development of precision therapies for ovarian cancer, laying a solid foundation for clinical translation, and ultimately offering more effective treatment options and improved quality of life for patients.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1. Figure S1. Quality control, filtering, and PCA of scRNA-seq data. (A) Violin plots showing the gene count per cell (nFeature_RNA), the number of mRNA molecules per cell (nCount_RNA), and the percentage of mitochondrial genes (percent.mt) in scRNA-seq data; (B) Scatter plots illustrating the correlation between filtered data nCount_RNA and percent.mt, and between nCount_RNA and nFeature_RNA; (C) Heatmap of the top 20 significantly correlated gene expressions in PC_1 – PC_6 of PCA, where yellow represents upregulated expression and purple represents downregulated expression; (D) Distribution of cells in PC_1 and PC_2 before batch correction, with each point representing a cell on the left, and violin plot showing distribution in PC_1 and PC_2 on the right; (E) Distribution of standard deviation of PCs, where important PCs have larger standard deviations.

Supplementary Material 2. Figure S2. Cell clustering of scRNA-seq data. (A) Distribution of cells in PC_1 and PC_2 after Harmony batch correction, with each point representing a cell on the left and violin plot showing the corrected distribution on the right; (B) Clustree package displaying clustering results at different resolutions; (C) Visualization of UMAP clustering results, depicting the aggregation and distribution of cells, with each color representing a cluster.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

WLL and WLH conceived and designed the study. WLL, MSS, SHW and NDD performed the experiments. WLL, MSS and SHW analyzed the data. SHW and NDD wrote the manuscript. WLH supervised the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Anhui Provincial Health Commissioner (Grant No. AHWJ2023BAa10019), Anhui Provincial Department of Education (Grant No. 2022AH051502).

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zheng X, Wang X, Cheng X, et al. Single-cell analyses implicate ascites in remodeling the ecosystems of primary and metastatic tumors in ovarian cancer. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(8):1138–56. 10.1038/s43018-023-00599-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J, Han X, Li J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics in ovarian cancer identify a metastasis-associated cell cluster overexpressed RAB13. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):254. 10.1186/s12967-023-04094-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li GN, Zhao XJ, Wang Z, et al. Elaiophylin triggers paraptosis and preferentially kills ovarian cancer drug-resistant cells by inducing MAPK hyperactivation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):317. 10.1038/s41392-022-01131-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Martín A, Harter P, Leary A, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(10):833–48. 10.1016/j.annonc.2023.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varghese A, Lele S. Rare ovarian tumors. In: Lele S, ed. Ovarian Cancer. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; September 8, 2022. [PubMed]

- 6.Yoon H, Kim A, Jang H. Immunotherapeutic approaches in ovarian cancer. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(2):1233–49. 10.3390/cimb45020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fantone S, Piani F, Olivieri F, et al. Role of SLC7A11/xCT in ovarian cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(1):587. 10.3390/ijms25010587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yim C, Hussein N, Arnason T. Capecitabine-induced hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(3):e241109. 10.1136/bcr-2020-241109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hussein M, Jensen AB. Drug-induced liver injury caused by capecitabine: a case report and a literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2023;16(1):378–84. 10.1159/000529866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu X, Guo Q, Li Q, Wan S, Li Z, Zhang J. Molecular mechanism study of EGFR allosteric inhibitors using molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022;40(13):5848–57. 10.1080/07391102.2021.1874530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmadi A, Mohammadnejadi E, Razzaghi-Asl N. Gefitinib derivatives and drug-resistance: a perspective from molecular dynamics simulations. Comput Biol Med. 2023;163: 107204. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du D, Liu C, Qin M, et al. Metabolic dysregulation and emerging therapeutical targets for hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(2):558–80. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong S, Guo X, Han F, He Z, Wang Y. Emerging role of natural products in cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(3):1163–85. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Cao Y, Guo X, et al. Hypoxia-induced ROS aggravate tumor progression through HIF-1α-SERPINE1 signaling in glioblastoma. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2023;24(1):32–49. 10.1631/jzus.B2200269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh JL, Kuo CH, Shih PW, Hsu JH, I-Chen P, Huang YH. Xanthine derivative KMUP-1 ameliorates retinopathy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;165:115109. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seephan S, Sasaki SI, Wattanathamsan O, et al. CAMSAP3 negatively regulates lung cancer cell invasion and angiogenesis through nucleolin/HIF-1α mRNA complex stabilization. Life Sci. 2023;322: 121655. 10.1016/j.lfs.2023.121655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tossetta G, Piani F, Borghi C, Marzioni D. Role of CD93 in health and disease. Cells. 2023;12(13):1778. 10.3390/cells12131778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chumakova SP, Urazova OI, Shipulin VM, et al. Role of angiopoietic coronary endothelial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiomyopathy. Biomedicines. 2023;11(7):1950. 10.3390/biomedicines11071950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan F, Malvestiti S, Vallet S, et al. JunB is a key regulator of multiple myeloma bone marrow angiogenesis [published correction appears in Leukemia. 2021 Dec;35(12):3628. 10.1038/s41375-021-01367-2]. Leukemia. 2021;35(12):3509–3525. 10.1038/s41375-021-01271-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Zhu X, Qiu C, Wang Y, et al. FGFR1 SUMOylation coordinates endothelial angiogenic signaling in angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(26): e2202631119. 10.1073/pnas.2202631119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang YC, Chen WC, Yu CL, et al. FGF2 drives osteosarcoma metastasis through activating FGFR1-4 receptor pathway-mediated ICAM-1 expression. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;218: 115853. 10.1016/j.bcp.2023.115853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng L, Liu H, Chen L, et al. Expression and purification of FGFR1-Fc fusion protein and its effects on human lung squamous carcinoma. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2024;196(1):573–87. 10.1007/s12010-023-04542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akgün AE, Yaylalı YT, Seçme M, Dodurga Y, Şenol H. Kynurenine-PARP-1 link mediated by MicroRNA 210 may be dysregulated in pulmonary hypertension. Anatol J Cardiol. 2022;26(5):388–93. 10.5152/AnatolJCardiol.2021.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell. 2021;184(13):3573-3587.e29. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin S, Wu J, Chen B, Li S, Huang H. Identification of a potential MiRNA-mRNA regulatory network for osteoporosis by using bioinformatics methods: a retrospective study based on the gene expression omnibus database. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:844218. 10.3389/fendo.2022.844218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L, Hernandez MO, Zhao Y, et al. Tumor cell biodiversity drives microenvironmental reprogramming in liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(4):418-430.e6. 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu XS, Zhou LM, Yuan LL, et al. NPM1 Is a Prognostic Biomarker Involved in Immune Infiltration of Lung Adenocarcinoma and Associated With m6A Modification and Glycolysis [published correction appears in Front Immunol. 2021;12:751004. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.751004]. Front Immunol. 2021;12:724741. Published 2021 Jul 16. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.724741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Arindrarto W, Borràs DM, de Groen RAL, et al. Comprehensive diagnostics of acute myeloid leukemia by whole transcriptome RNA sequencing. Leukemia. 2021;35(1):47–61. 10.1038/s41375-020-0762-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zeng Y, Cao S, Chen M. Integrated analysis and exploration of potential shared gene signatures between carotid atherosclerosis and periodontitis. BMC Med Genomics. 2022;15(1):227. 10.1186/s12920-022-01373-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vivian J, Rao AA, Nothaft FA, et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(4):314–6. 10.1038/nbt.3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eden SK, Li C, Shepherd BE. Spearman-like correlation measure adjusting for covariates in bivariate survival data. Biom J. 2023;65(8): e2200137. 10.1002/bimj.202200137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan N, Pan HH, Liang YS, Hu HL, Zhai CL, Wang B. Identification of prognostic and diagnostic signatures for cancer and acute myocardial infarction: multi-omics approaches for deciphering heterogeneity to enhance patient management. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1249145. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1249145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiappetta G, Gamberi T, Faienza F, et al. Redox proteome analysis of auranofin exposed ovarian cancer cells (A2780). Redox Biol. 2022;52: 102294. 10.1016/j.redox.2022.102294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai Y, Zhou H, Zhu Y, et al. Elimination of senescent cells by β-galactosidase-targeted prodrug attenuates inflammation and restores physical function in aged mice. Cell Res. 2020;30(7):574–89. 10.1038/s41422-020-0314-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Word BR, Lyn-Cook BD. Enhanced efficacy of gemcitabine by indole-3-carbinol in pancreatic cell lines: the role of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1. Anticancer Res. 2011;31(10):3171–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu XM, Chen QH, Hu Q, et al. Dexmedetomidine protects intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibiting p38 MAPK cascades. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;115: 104444. 10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim JS, Shin MJ, Lee SY, et al. CD109 promotes drug resistance in A2780 ovarian cancer cells by regulating the STAT3-NOTCH1 signaling axis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):10306. 10.3390/ijms241210306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salem M, Shan Y, Bernaudo S, Peng C. miR-590-3p targets cyclin G2 and FOXO3 to promote ovarian cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and spheroid formation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(8):1810. 10.3390/ijms20081810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shu M, Zheng X, Wu S, et al. Targeting oncogenic miR-335 inhibits growth and invasion of malignant astrocytoma cells. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:59. 10.1186/1476-4598-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang L, Zhou J, Zhao S, Wang X, Chen Y. STK17B promotes the progression of ovarian cancer. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(6):475. 10.21037/atm-21-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding W, Shi Y, Zhang H. Circular RNA circNEURL4 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion of papillary thyroid carcinoma by sponging miR-1278 and regulating LATS1 expression. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(6):5911–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant CS, Munkarah AR, Kumar S, et al. Reduction of hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in ovarian cancer cells by inhibition of HIF-1 alpha gene expression. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282(6):677–83. 10.1007/s00404-010-1381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pignata S, Pisano C, Di Napoli M, Cecere SC, Tambaro R, Attademo L. Treatment of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer [published correction appears in Cancer. 2020 Apr 1;126(7):1588. 10.1002/cncr.32704]. Cancer. 2019;125(Suppl 24):4609–4615. 10.1002/cncr.32500 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Rashid M, Zadeh LR, Baradaran B, et al. Up-down regulation of HIF-1α in cancer progression. Gene. 2021;798: 145796. 10.1016/j.gene.2021.145796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ding Y, Zhuang S, Li Y, Yu X, Lu M, Ding N. Hypoxia-induced HIF1α dependent COX2 promotes ovarian cancer progress. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2021;53(4):441–8. 10.1007/s10863-021-09900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Namjoo M, Ghafouri H, Assareh E, et al. A VEGFB-based peptidomimetic inhibits VEGFR2-mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR and PLCγ/ERK signaling and elicits apoptotic, antiangiogenic, and antitumor activities. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(6):906. 10.3390/ph16060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee C, Chen R, Sun G, et al. VEGF-B prevents excessive angiogenesis by inhibiting FGF2/FGFR1 pathway. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):305. 10.1038/s41392-023-01539-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alter R, Cohen A, Guigue PA, Meyer R, Levin G. Ethnic disparities in the incidence of gynecologic malignancies among Israeli Women of Arab and Jewish Ethnicity: a 10-year study (2010–2019). Ther Adv Reprod Health. 2023;18:26334941231209496. 10.1177/26334941231209496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valery M, Vasseur D, Fachinetti F, et al. Targetable molecular alterations in the treatment of biliary tract cancers: an overview of the available treatments. Cancers. 2023;15(18):4446. 10.3390/cancers15184446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sayin S, Mitchell A. Functional assay for measuring bacterial degradation of gemcitabine chemotherapy. Bio Protoc. 2023;13(17):e4797. 10.21769/BioProtoc.4797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bobrovskikh A, Doroshkov A, Mazzoleni S, Cartenì F, Giannino F, Zubairova U. A sight on single-cell transcriptomics in plants through the prism of cell-based computational modeling approaches: benefits and challenges for data analysis. Front Genet. 2021;12:652974. 10.3389/fgene.2021.652974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian SW, Ni JC, Wang YT, Zheng CH, Ji CM. scGCC: graph contrastive clustering with neighborhood augmentations for scRNA-Seq data analysis. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(12):6133–43. 10.1109/JBHI.2023.3319551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jagieła J, Bartnicki P, Rysz J. Nephrotoxicity as a complication of chemotherapy and immunotherapy in the treatment of colorectal cancer, melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4618. 10.3390/ijms22094618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu S, Dong K, Gao R, et al. Cuproptosis-related signature for clinical prognosis and immunotherapy sensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(13):12249–63. 10.1007/s00432-023-05099-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang X, Jing H, Li H. A novel cuproptosis-related lncRNA signature to predict prognosis and immune landscape of lung adenocarcinoma. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2023;12(2):230–46. 10.21037/tlcr-22-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, hypoxia-inducible factors, and disease pathophysiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:47–71. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang D, Lv FL, Wang GH. Effects of HIF-1α on diabetic retinopathy angiogenesis and VEGF expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(16):5071–6. 10.26355/eurrev_201808_15699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Okada-Ban M, Thiery JP, Jouanneau J. Fibroblast growth factor-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32(3):263–7. 10.1016/s1357-2725(99)00133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chlebova K, Bryja V, Dvorak P, Kozubik A, Wilcox WR, Krejci P. High molecular weight FGF2: the biology of a nuclear growth factor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66(2):225–35. 10.1007/s00018-008-8440-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Javle M, King G, Spencer K, Borad MJ. Futibatinib, an Irreversible FGFR1-4 Inhibitor for the Treatment of FGFR-Aberrant Tumors. Oncologist. 2023;28(11):928–43. 10.1093/oncolo/oyad149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang C. Infigratinib: First Approval [published correction appears in Drugs. 2022 Jan;82(1):93. 10.1007/s40265-021-01652-5]. Drugs. 2021;81(11):1355–1360. 10.1007/s40265-021-01567-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Mazzola CR, Siddiqui KM, Billia M, Chin J. Dovitinib: rationale, preclinical and early clinical data in urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2014;23(11):1553–62. 10.1517/13543784.2014.966900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1. Figure S1. Quality control, filtering, and PCA of scRNA-seq data. (A) Violin plots showing the gene count per cell (nFeature_RNA), the number of mRNA molecules per cell (nCount_RNA), and the percentage of mitochondrial genes (percent.mt) in scRNA-seq data; (B) Scatter plots illustrating the correlation between filtered data nCount_RNA and percent.mt, and between nCount_RNA and nFeature_RNA; (C) Heatmap of the top 20 significantly correlated gene expressions in PC_1 – PC_6 of PCA, where yellow represents upregulated expression and purple represents downregulated expression; (D) Distribution of cells in PC_1 and PC_2 before batch correction, with each point representing a cell on the left, and violin plot showing distribution in PC_1 and PC_2 on the right; (E) Distribution of standard deviation of PCs, where important PCs have larger standard deviations.

Supplementary Material 2. Figure S2. Cell clustering of scRNA-seq data. (A) Distribution of cells in PC_1 and PC_2 after Harmony batch correction, with each point representing a cell on the left and violin plot showing the corrected distribution on the right; (B) Clustree package displaying clustering results at different resolutions; (C) Visualization of UMAP clustering results, depicting the aggregation and distribution of cells, with each color representing a cluster.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.