Abstract

The genetically attested migrations of the third millennium BC have made the origins and nature of the Yamnaya culture a question of broad relevance across northern Eurasia. But none of the key archaeological sites most important for understanding the evolution of Yamnaya culture is published in western languages. These key sites include the fifth-millennium BC Khvalynsk cemetery in the middle Volga steppes. When the first part of the Eneolithic cemetery (Khvalynsk I) was discovered in 1977–79, the graves displayed many material and ritual traits that were quickly recognized as similar and probably ancestral to Yamnaya customs, but without the Yamnaya kurgans. With the discovery of a second burial plot (Khvalynsk II) 120m to the south in 1987–88, Khvalynsk became the largest excavated Eneolithic cemetery in the Don-Volga-Ural steppes (201 recorded graves), dated about 4500–4300 BCE. It has the largest copper assemblage of the fifth millennium BC in the steppes (373 objects) and the largest assemblage of sacrificed domesticated animals (at least 106 sheep-goat, 29 cattle, and 16 horses); and it produced four polished stone maces from well-documented grave contexts. The human skeletons have been sampled extensively for ancient DNA, the basis for an analysis of family relationships. This report compiles information from the relevant Russian-language publications and from the archaeologists who excavated the site, two of whom are co-authors, about the history of excavations, radiocarbon dates, copper finds, domesticated animal sacrifices, polished stone maces, genetic and skeletal studies, and relationships with other steppe cultures as well as agricultural cultures of the North Caucasus (Svobodnoe-Meshoko) and southeastern Europe (Varna and Cucuteni-Tripol’ye B1). Khvalynsk is described as a coalescent culture, integrating and combining northern and southern elements, a hybrid that can be recognized genetically, in cranio-facial types, in exchanged artifacts, and in social segments within the cemetery. Stone maces symbolized the unification and integration of socially defined segments at Khvalynsk.

Keywords: Eneolithic, Russian steppe, mortuary archaeology, ritual sacrifice, copper metallurgy, ancient DNA, social differentiation

Introduction: the Yamnaya phenomenon and its origins

Recent large-scale studies of ancient DNA (aDNA) show that the Bronze Age populations in the steppes of present-day Russia and Ukraine migrated across both Europe and Asia during the Early Bronze Age (EBA) and the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) in the chronology of the western steppes (Haak et al 2015; Allentoft et al 2015; Mathiesen et al. 2018; Damgaard et al 2018; Wang et al 2018; Narasimhan et al. 2019). Between 3100–2500 BCE the Yamnaya culture expanded out of its steppe homeland westward into central Europe, where people with ca. 70% Yamnaya ancestry created the Corded Ware horizon (Haak et al. 2015; Frînculeasa et al 2015; Nikitin 2018); and eastward to the Altai Mountains, where people almost identical to the Yamnaya population in genetic ancestry appeared as the Afanasievo culture (Allentoft et al. 2015; Narasimhan 2018). Today the origin and nature of the Yamnaya archaeological culture is a question with new relevance across northern Eurasia. Yet none of the key archaeological sites most important for understanding the evolution of Yamnaya customs and economy is published in a western language. These key sites would include Khvalynsk on the Volga (Eneolithic), Repin on the Don (EBA), and Mikhailovka (EBA) on the Dnieper rivers.2 This essay is about Khvalynsk, an Eneolithic cemetery on the Volga River dated ca. 4500–4300 BCE.

In this report we present new aDNA-based studies of the Khvalynsk population in combination with traditional archaeological and anthropological studies. The formal presentation of the ancient DNA data along with a comprehensive set of genetic analyses will be made in a separate publication; here, we summarize results where they are relevant to understanding the Khvalynsk cemetery population. In addition, we present specific analytical summaries of radiocarbon dates and stable isotopes, copper artifacts, animal sacrifices, and polished stone maces. We argue that Khvalynsk exhibits remarkable diversity in its population and equally remarkable segmentation between groups of individuals in its grave offerings (Figure 1). We discuss how the Khvalynsk cemetery was related to other sites and archaeological cultures during the steppe Eneolithic. We also discuss cranio-facial types, skeletal pathologies, and new data from aDNA on family relationships within the Khvalynsk cemetery, with broader comments on the evolution of “steppe ancestry” that later characterized the Yamnaya populations.

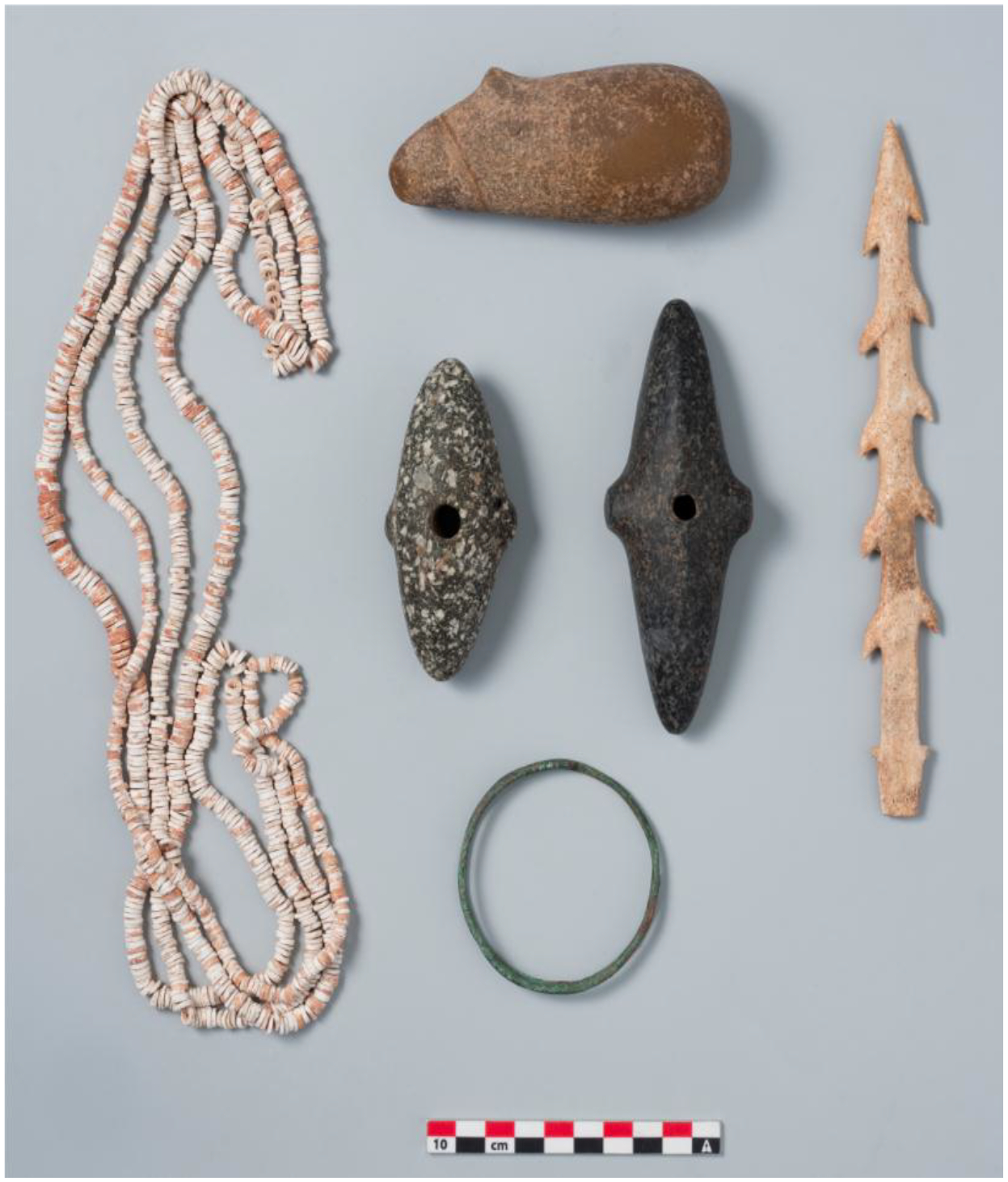

Figure 1:

Artifacts from Khvalynsk I. Three polished stone mace heads, antler harpoon, copper bracelet, and Unio shell beads. Photo by the State Historical Museum, Moscow. Used with permission.

Western archaeologists have asked if, by applying a cultural label such as ‘Yamnaya’ to a biological unit of analysis, as in ‘the typical Yamnaya pattern of genetic ancestry’, we imply that all Yamnaya-culture individuals had not only the same ancestry, but the same pottery, ornaments, and economy (Eisenmann et al. 2018; Furholt 2018, 2019; Hofmann 2019). However, to speak of a typical measurement or pottery type is never to imply that no outliers or variation existed; indeed, the concept of the average or typical observation implies the opposite. The Eneolithic populations of the Pontic-Caspian steppes (north of the Black and Caspian Seas) can be divided into regional groups defined by both material/cultural customs and genetic/morphological traits. Funeral customs (body pose, grave shape) varied regionally, as did pottery styles and economies. Ceramic types were more varied than cranio-facial or genetically defined groups. Figure 2 shows that Khvalynsk-style ceramics were the predominant ceramic type only in the middle and lower Volga steppes, while people with genetic ancestry like Khvalynsk can be found 1000 km to the south in the North Caucasus steppes. The Khvalynsk mating network extended far beyond the Khvalynsk pottery style.

Figure 2:

Important archaeological sites of the 5th millennium BC in and near the Pontic-Caspian steppes. Orange line: ecological border of steppe. Black circles: steppe Eneolithic; red: Old Europe; orange: Meshoko Eneolithic. Stippled area: sites with Khvalynsk style ceramics.

Anthony refers to groups defined by similarities in their aDNA as mating networks (Anthony 2019: 2). A mating network is a population that shared a distinctive cluster of autosomal genetic traits such that individuals from that chronological period and region can be assigned to a space in a principal components analysis (PCA) plot that does not overlap significantly with the spaces occupied by other contemporary mating networks. Mating networks were maintained by the long-term, multi-generational exchange of daughters and/or sons as mates, creating significant gene flow between groups within the network. It cannot be assumed that mating networks were culturally relevant or even known to ancient populations, although borders between mating networks probably were recognized.

One interesting aspect of the Yamnaya mating network was its narrowness, more homogeneous (a more restricted space in a PCA) than the earlier Eneolithic populations. This reduction in genetic diversity between Eneolithic and EBA populations is interesting partly because EBA material culture (archaeology) exhibited contradictory trends at this transition—Yamnaya funeral rituals became more standardized and homogeneous than in the Eneolithic, like Yamnaya aDNA; but many regional Eneolithic artifact types, including regional ceramic types, continued into the EBA and appeared as regional variants that contrasted with the genetic and ritual homogeneity of Yamnaya ancestry and grave types. In the Pontic-Caspian steppes, mating networks and cultural traditions had a dynamic, changing relationship. Khvalynsk provides a data-rich window through which to examine the material and genetic variability of the pre-Yamnaya population at one of the largest and most important Eneolithic cemeteries.

The importance of Khvalynsk

Khvalynsk is the largest excavated Eneolithic cemetery in the Don-Volga-Ural steppes (201 recorded graves). It has the largest copper assemblage of the late fifth millennium BC in the steppes (373 objects) and the largest assemblage of sacrificed domesticated animals (at least 106 sheep-goat, 29 cattle, and 16 horses). The human skeletons have been sampled extensively for ancient DNA, but genome-wide data from only three individuals has been published to date (Mathieson et al. 2018). Here we discuss relevant results from 32 analyzed individuals. The whole genomes of three additional Eneolithic individuals from graves in the North Caucasus steppes dated 4400–4100 BC at the Progress-2 and Vonyuchka-13 cemeteries, broadly contemporary with Khvalynsk, were previously recognized as similar in ancestry and in PCA space to the published three from Khvalynsk (Wang et al. 2019: 3). This discovery expanded the range of the Khvalynsk mating network 1000 km to the south, from the Middle Volga steppes to the North Caucasus steppes. Unpublished samples from Volga Eneolithic cemeteries do not significantly alter the relationships or PCA space observed in the initial published samples, but rather form a cline between Khvalynsk and Progress-2. The Khvalynsk/Progress-2 ancestry cline represents a distant genetic ancestor, although not the exclusive or proximate ancestor, for the typical pattern of genetic ancestry exhibited in Yamnaya individuals. Yamnaya individuals cluster near Khvalynsk/Progress-2 in PCA space, but their distributions overlap only marginally (Wang et al. 2019; Narasimhan 2019). Yamnaya genomes had additional Anatolian Farmer ancestry (typical for agricultural populations in southeastern Europe and the North Caucasus) not present in Khvalynsk/Progress-2 (Wang et al. 2019: 6–7). Khvalynsk is important because of its size, its unique concentration of copper artifacts and domesticated animal sacrifices, and its genetic and ritual connections with the Yamnaya culture.

When Khvalynsk was discovered in 1977 it was recognized immediately, and with some excitement, as a good candidate for the elusive pre-Yamnaya archaeological phase in the Volga steppes (Vasiliev 1981). The shell-tempered, round-bottomed pottery of Khvalynsk, decorated with small comb stamps and shell-edge impressions, was like one of the earliest Yamnaya pottery types, found in Yamnaya kurgans in the southern Volga steppes (Bykovo I 12/7 type; see Mallory 1977). Also, the position of the body in most graves, on the back with tightly raised knees, was identical to a distinctive Yamnaya body pose often called ‘the Yamnaya position’ (Heyd 2012; Frînculeasa et al 2015). The abundant red ochre on the grave floor also was like Yamnaya. The differences between them (ornament and weapon types, absence of kurgans at Khvalynsk) were ascribed to the earlier chronological position of Khvalynsk (Agapov, Vasiliev, and Pestrikova 1990:83–85). It was anticipated that Khvalynsk would have radiocarbon dates in the early to middle fourth millennium BCE (Vasiliev 1981), not long before the oldest cluster of Yamnaya radiocarbon dates, 3300–3000 BCE. But radiocarbon dates calculated on human bone instead suggested that Khvalynsk dated ca 5200–4500 BC, almost 2000 years older than Yamnaya (Agapov et al. 1990:86–87). Archaeologists did not yet know that radiocarbon dates on Eneolithic human bones were skewed older by the absorption of old carbon in the bones of populations that regularly ate riverine fish, a phenomenon now known as a freshwater reservoir effect (FRE). The long chronological gap between Khvalynsk and Yamnaya was regarded uneasily as a ‘hiatus’ (Agapov et al. 1990:86–87; Rassamakin 1999:122). Here we show that Khvalynsk was in use about 4500–4300 BCE, about 1000 years before the Yamnaya culture appeared, contemporary with Skelya and early Sredni Stog4 in the Pontic steppes (Rassamakin 2002, 2013; Telegin 1986) and Varna I in the Danube valley.

A significant chronological gap still exists between Khvalynsk and Yamnaya. Subsequent discoveries of a few graves similar in ritual details to Khvalysnk and dated to the fourth millennium BCE have filled the gap to some extent, but the early fourth millennium BCE remains surprisingly poorly documented in the Volga-Ural steppes (Vasiliev and Ovchinnikova 2000; Morgunova 2014). This intermediate period is better documented in the North Caucasus steppes (Korenevskii 2016) and the Black Sea steppes west of the Don River, where the Sredni Stog culture introduced Khvalynsk-like grave rituals with Khvalynsk-like DNA traits 4500–3500 BCE (Kotova 2013; Rassamakin 2013). Sredni Stog is often seen as an ancestor of Yamnaya in Ukraine (Telegin et al. 2001; Anthony 2007: 240–249).

Other Eneolithic cemeteries were smaller than Khvalynsk, usually less than 30 graves. Khlopkov Bugor, 130 km south of Khvalynsk on the west Volga bank, had 24 excavated Eneolithic graves, including one person who was a 2nd-degree relative of a person buried at Khvalynsk (see below). A cemetery on the Volga 160 km north of Khvalynsk, at Ekaterinovka Mys, dated 150–200 years earlier, had more than 100 excavated graves (Korolev et al. 2018). Nalchik in the North Caucasus, approximately contemporary with Khvalynsk, had 121 graves (Gimbutas 1956: 53–54; Anthony 2007:187). A few other large Eneolithic cemeteries are known in the Volga-Caucasus steppes, but Khvalynsk was the largest.

The exceptional size of the Khvalynsk cemetery, as well the morphological (according to cranio-facial measurements) and genetic heterogeneity of those interred there, were linked to its integrative ritual position during an era of population movements and economic change in the Volga steppes. The Khvalynsk people showed ancestry from a southern population that can be derived, using both cranio-facial measurements and aDNA, from regions including the Caucasus and the lower Don steppes (Khokhlov 2017). These southern-derived people mingled in the Volga steppes, around Khvalynsk and south of Khvalynsk, with a population that can be derived, using both cranio-facial and aDNA data, from the northern forest zone (Khokhlov 2017). The admixed population that resulted from this north-south combination gathered at Khvalynsk to conduct funeral activities, feast on the meat of newly acquired domesticated animals, and celebrate alliance-making symbols (polished stone maces, see below). The earliest domesticated animals appeared in the middle Volga steppes around 4800–4600 BCE (using dates on animal bones), just 100–300 years before Khvalynsk (Morgunova 2015; Vybornov et al. 2019). Khvalynsk appears to have been a central place for the performance of these relatively new sacrificial rituals, a gathering place for genetically diverse populations participating in a new funeral cult focused on the ritual power and value of domesticated animals.

Copper ornaments were another introduced innovation used in a new way. Khvalynsk was part of a network of cultures that participated between 4500–4200 BC in the exchange of copper, exotic shells, domesticated animals, and emerging symbols of hierarchical leadership (polished stone maces) between the Volga steppes, the North Caucasus steppes, the Dnieper steppes, and the tell towns of the lower Danube valley and the Varna region in Bulgaria (Figure 2). The agricultural communities of the Karanovo VI/Gumelniţa/Tripol’ye B1 period were the copper-producing centers of the network, which Chernykh (1992) named the ‘Carpatho-Balkan Metallurgical Province’. Khvalynsk is the easternmost site included in this ‘province’ (Chernykh 2008). Khvalynsk is thus an essential site for understanding the introduction of domesticated animals and copper metallurgy to the steppes, and the genetic, morphological, and cultural origins of the population that would later become Yamnaya. Up to now, no English-language summary of the site exists beyond short descriptions contained in longer works (Anthony 2007: 182–186; Mallory and Adams 1997: 328).

History and ecological setting of Khvalynsk I and II

Before 1971, when the hydroelectric dam was completed at Balakovo 40km downstream, the Khvalynsk cemetery was located on the west bank of the Volga River 16 km south of the town of Khvalynsk at 52°21’14.58”N, 48° 4’44.80”E (Figures 2, 3). The site is now under the Saratov Reservoir created by the dam. Here dry limestone hills overlooked the Volga on its west side, and a flat steppe plain rolled away to its east. The Eneolithic cemetery was at the foot of the western hills at a place where their white peaks stood 3–5 km away from the river. The Volga River, more than a kilometer wide, flowed through a wetland of large forested islands and marshes 5km wide at this location, now a 5km-wide reservoir (Figure 3).

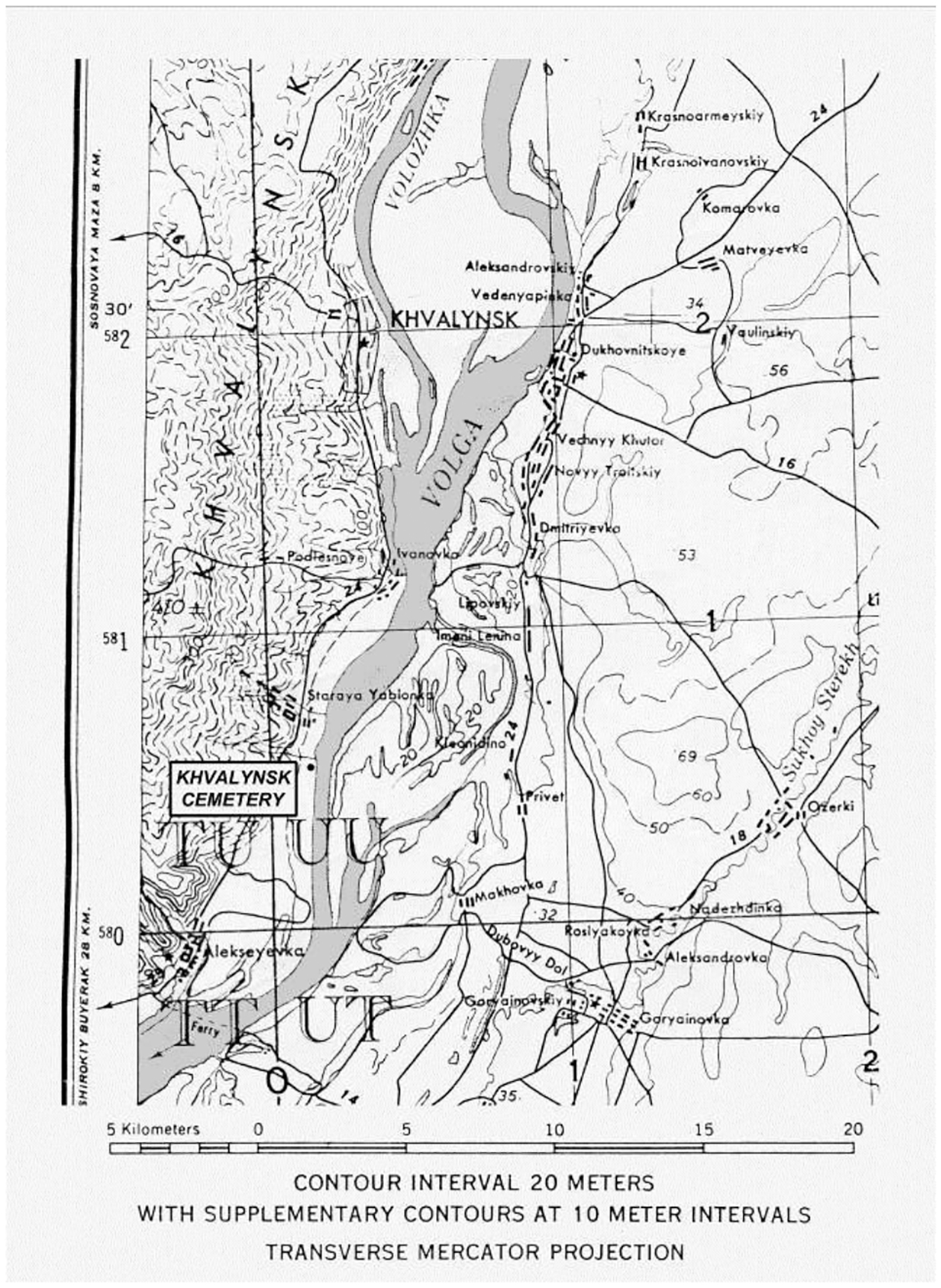

Figure 3.

Topographic map of the Khvalynsk area ca. 1930 before dams, with cemetery marked. Army Map service, Corps of Engineers, 1957, Series N501, NN-3901, edition 3-AMS, 1:250,000; based on USSR 1:50,000 General Staff of the Red Army maps, 1929–1932.

Vegetation varied significantly between wooded ravines on the high west bank, a flat steppe on the east bank, and forests and marshes on the Volga bottomlands. At the Eneolithic settlement of Lebyazhinka VI north of Samara, with radiocarbon dates contemporary with Khvalynsk (Kulkova et al 2017), the most frequent fish bones were those of northern pike (Esox lucius), which in this region can weigh up to 25 kg; followed by catfish (Silurus glanis), up to 300 kg; and zander (Sander lucioperca), up to 20 kg (Kirillova et al. 2017). Large birds whose tubular bones were used for flutes or whistles in the Khvalynsk graves included white-tailed eagles (Haliaeetus albicilla), bustards (Otis tarda), cranes (Grus grus), and swans (Cygnus sp.) (Kirillova 2010:364). Broad-leaf forests on the 5-km-wide floodplain hosted moose (Alces alces), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), wild boar (Sus scrofa) and aurochs (Bos primigenius), as well as smaller game (Morgunova 2014: Tables 19, 20, 21). East of the gallery forest a dry steppe plain rolled unbroken to the Altai Mountains in Siberia. In the Volga-Ural region, the steppes contained wild horses (Equus caballus) in the northern steppes near Khvalynsk and saiga antelope (Saiga tartarica) and onagers (Equus hemionus) in the drier southern Volga steppes bordering the Caspian Sea (Morgunova 2014:Table 21; Vybornov et al. 2019).

Erosion of the western bank after the reservoir was filled led to the discovery and salvage excavation in 1977–79 of the northern cemetery of 158 individuals, later designated Khvalynsk I (Figure 4). An unknown number of graves was lost before the archaeologists arrived. The director was I.B. Vasiliev, the energetic leader of the archaeology faculty at the Samara (then Kuibyshev) Pedagogical Institute, now the Samara State Social-Pedagogical University. The Volga continued to erode the cemetery during the excavation, swallowing 4m in the two years between 1977 and 1979, indicated in Figures 4 and 15 by the two parallel lines on the right side of Khvalynsk I. The graves were isolated in the center of the explored area, with no additional graves found to the north, south, or west, leading the archaeologists to believe that they had established the limits of the cemetery on all sides except the rapidly eroding east (Agapov, Vasiliev, and Pestrikova 1990:6–7). A report was published in the Russian language in 1990 (Agapov et al. 1990) describing each grave and surface sacrificial deposit.

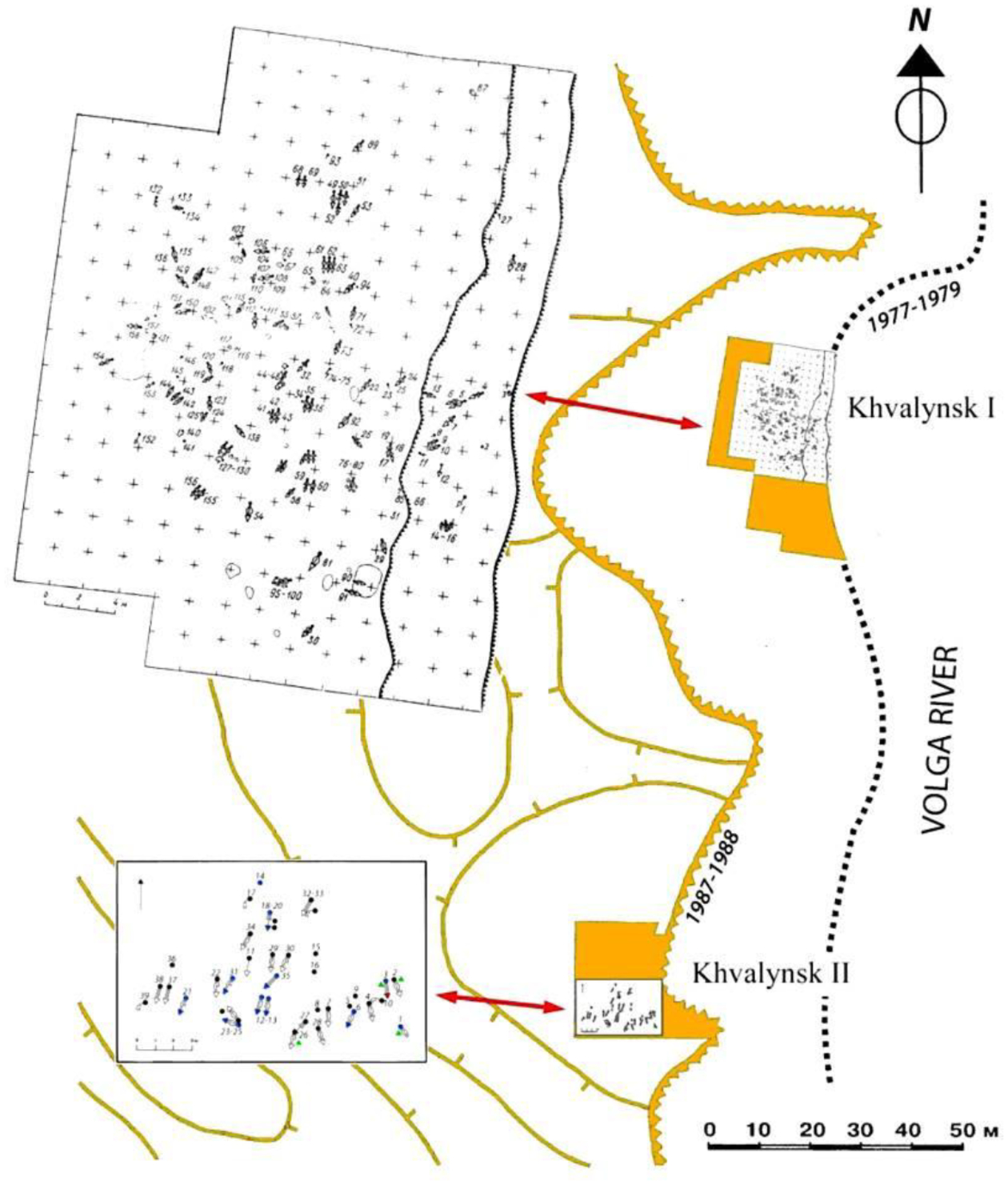

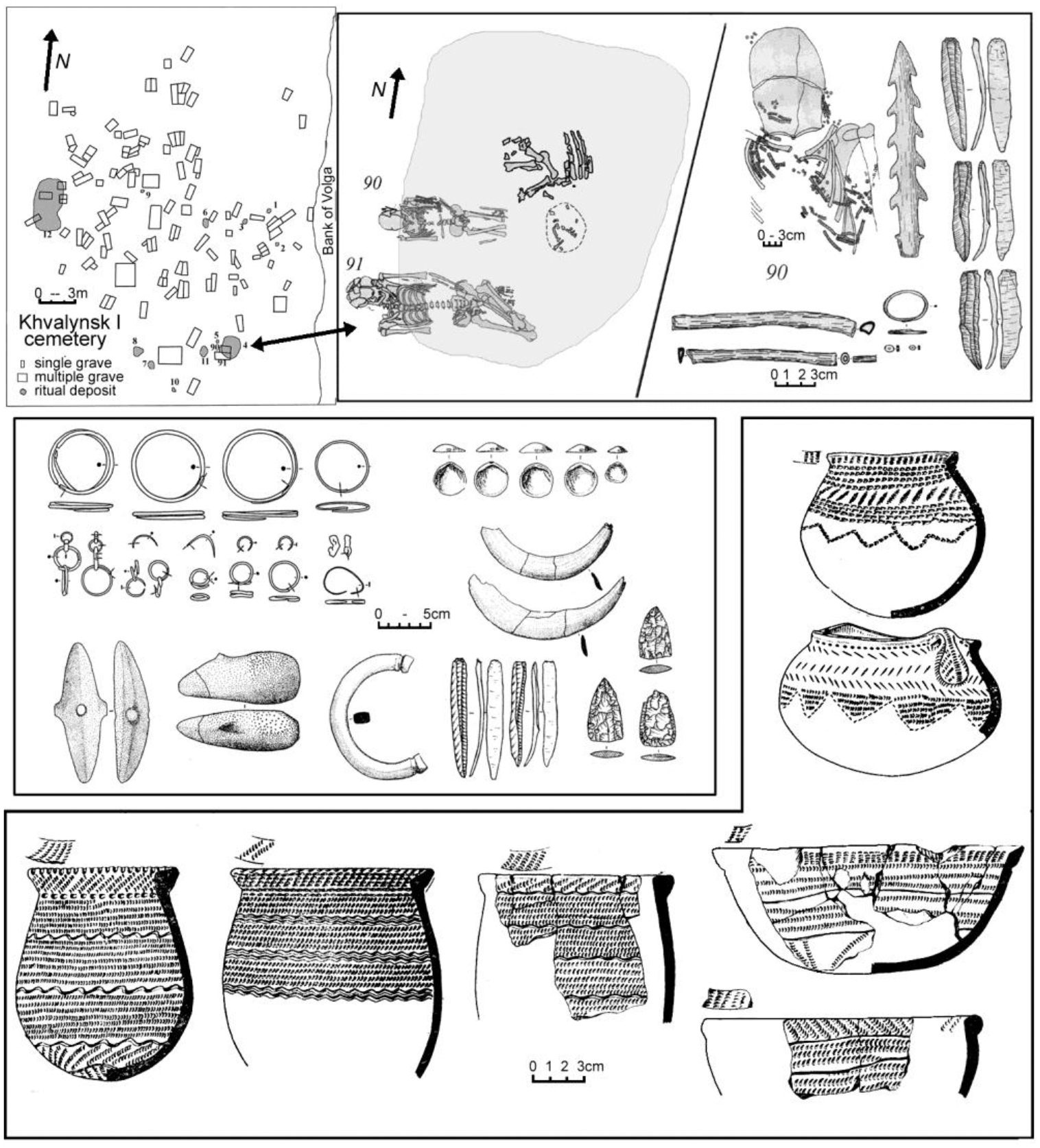

Figure 4:

Plans of Khvalynsk I and II, with cemetery plans shown within the investigated areas (shaded). For II, the location of the cemetery-plan rectangle within the investigated area is approximate. (After Agapov Vasiliev & Pestrikova 1990: Figure 2; and S. Agapov 2010: un-numbered map on page 118.)

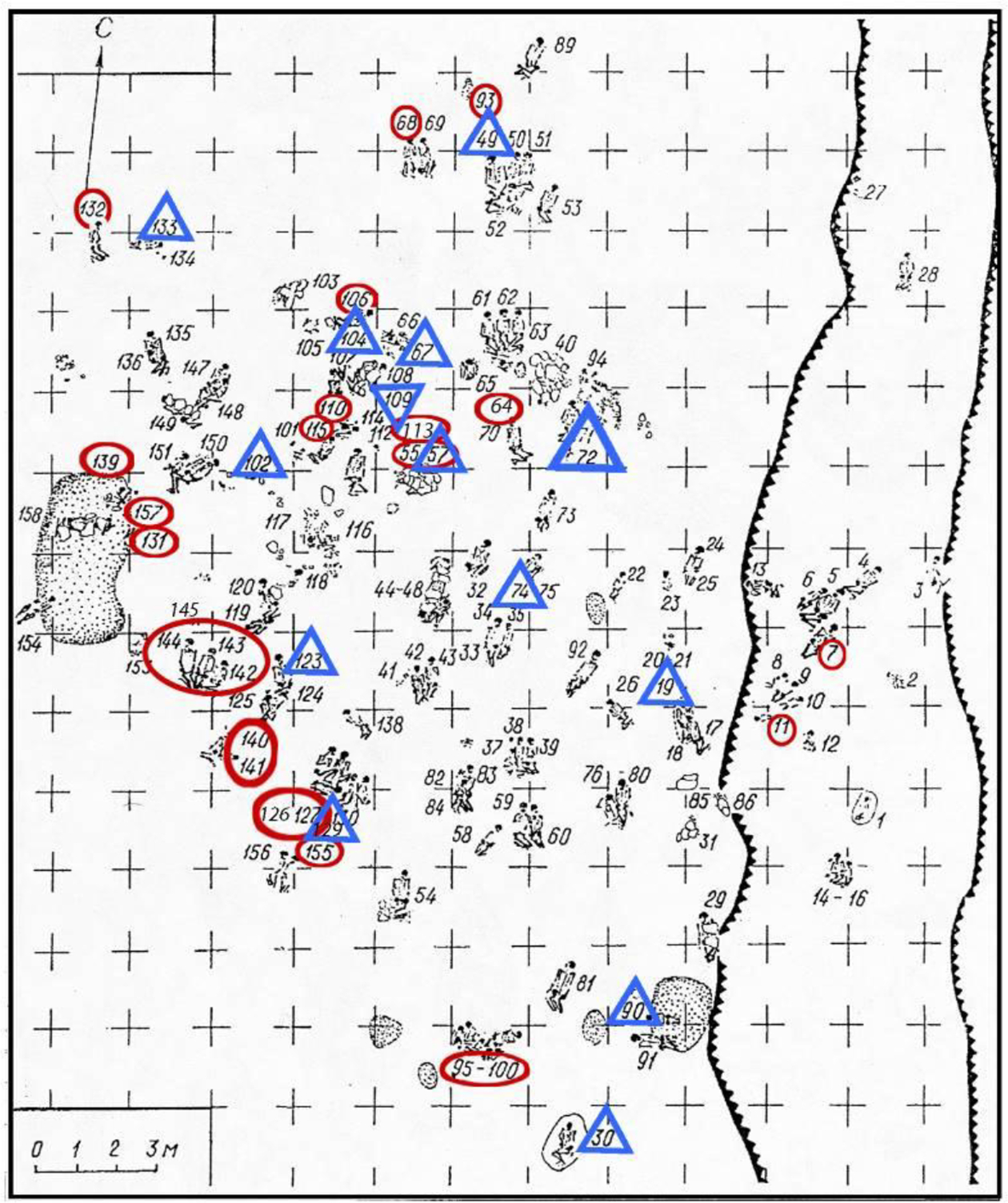

Figure 15:

Plan of Khvalynsk I. Red circles = animal sacrifices; Blue triangles = copper finds; Stippled areas = surface sacrificial deposits in red ochre; Serrated lines = Volga River bank in 1977 and 1979. Arrow with ‘C’ denotes north. Graves 90 & 91 are illustrated in Figure 9, graves 147–149 in Figure 5. Total area explored was larger; see shaded area in Figure 4. After Vasiliev 2003.

Khvalynsk II was discovered 10 years after Khvalynsk I when continuing erosion exposed additional human skeletons 120m southwest of the first cemetery. Khvalynsk II was excavated in 1987–1988 by many of the same archaeologists from Samara (Kuibyshev) who had worked on Khvalynsk I, including A. Khokhlov and S. Agapov, co-authors of this report. I.B. Vasiliev again directed the first part of the excavation, and V.I. Pestrikova directed the second part. The Khvalynsk II excavation recovered 43 individuals (Khokhlov 2010:Table 1.1), again after an unknown number were lost to the Volga. A monograph describing both Khvalynsk I and II was published 22 years after the excavation ended (S. Agapov 2010). It contains many specialist studies (lithics, ceramics, metallurgy, fauna, shells, skeletal measurements, etc) in the Russian language. Pestrikova’s unpublished dissertation on Khvalynsk I was revised by D. Agapov for the opening essay of the 2010 monograph (Pestrikova and Agapov 2010). The 1990 and 2010 monographs are the most important sources of information for this report.

The funeral rituals (body pose, grave form, use of ochre, etc), ceramic types, lithics, ornaments, and radiocarbon dates from the two cemeteries are alike. Khvalynsk I and II were used during the same era by people from the same archaeological culture. But the demographic traits of I and II were sharply different. At Khvalynsk I males and females were buried in nearly equal numbers. Among 83 adults or adolescents to whom a sex could be assigned based on skeletal features, 45 (54%) were males and 38 (46%) were females (Khokhlov 2010: 410). Copper ornaments accompanied six adult males and five adult females at Khvalynsk I, again about equal, and were found with one infant and two adolescents.

The Khvalynsk II burial plot, in contrast, was heavily weighted toward adult males: more than three adult males for each adult female. Of 26 skeletons assignable to a sex, 20 (77%) were males and only six (23%) were females (Khokhlov 2010: 410). This was much like the proportion of males and females buried later in Yamnaya graves in the Volga steppes (80% males). This raises the question if Yamnaya gender practices evolved not from the preceding ‘culture’ but specifically from an Eneolithic sodality or other male-focused sub-group like the one buried in the Khvalynsk II cemetery. The absolute number of copper ornaments buried with 158 individuals at Khvalynsk I (35) was one tenth of the number found with 43 individuals at Khvalynsk II (338) (D. Agapov 2010). The abundant copper at Khvalynsk II accompanied about one third of both males and females: nine adult males and two adult females. Copper ornaments also were found with an infant and a child.

Khvalynsk I looks like a ‘family’ cemetery where all ages and sexes were buried, while Khvalynsk II was a more specialized cemetery for a copper-rich group of males (possibly warriors or traders), most of whom were related by family descent (see genetics section below), with a few unrelated males, females and immatures.

Unfortunately, another difference between I and II is that most of the skeletons from I were lost in a Volga River flood that destroyed the storage area where they were curated in the river-port city of Samara. One might say that the Volga reached for these graves twice. Contemporary studies, including ancient DNA studies, can be conducted only on male-dominated II and the small number of individuals from I that survived the flood (9 of 158—see Table 1 radiocarbon dates).

Table 1: Khvalynsk I and II radiocarbon dates and stable isotopes.

Paired human-terrestrial fauna dates in bold. Note that some individuals were sampled more than once. c2 tests in red italics fail to combine (i.e., they are significantly different).

| Grave # | Material | Lab number | Age BP | ± | calBC (95%) | calBC mean | δ13C | δ15N | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khvalynsk I | ||||||||||

| Skel. 4 | Human F | UPI-119 | 5903 | 72 | 4985 | 4555 | 4779 | |||

| Skel. 13 | Human F | UPI-122 | 4030 | 60 | 2865 | 2350 | 2583 | |||

| Skel. 17 | Human F | PSUAMS-2883 | 5775 | 25 | 4703 | 4547 | 4627 | −22.9 | 14.6 | |

| Grave 19 | Shell bead | Ki-2180 | 7140 | 150 | 6367 | 5725 | 6017 | χ 2 , df=2, T=9.3(5% 6.0) | ||

| Grave 19 | Shell bead | Ki-? | 6570 | 150 | 5754 | 5215 | 5505 | |||

| Grave 19 | Shell bead | Ki-? | 6600 | 150 | 5801 | 5220 | 5533 | |||

| Skel. 26 | Human F | UPI-120 | 5808 | 79 | 4841 | 4458 | 4660 | |||

| Skel. 30 | Human M | PSUAMS-2884 | 5995 | 25 | 4983 | 4795 | 4882 | −20.8 | 15.3 | |

| Skel. 62 | Human M | UPI-132 | 6085 | 193 | 5471 | 4549 | 5003 | |||

| Skel. 127 | Human M | GrA-26899 | 5840 | 40 | 4796 | 4553 | 4700 | −20.7 | 14.5 | χ 2 , df=2, T=21.0(5% 3.8) |

| Skel. 127 | Human M | PSUAMS-2885 | 5625 | 25 | 4537 | 4362 | 4444 | −20.6 | 14.1 | |

| Skel. 147 | Human F | PSUAMS-2886 | 5845 | 25 | 4791 | 4615 | 4716 | −21.6 | 14.5 | |

| Grave 147 | Sheep-goat bone ring | GrA-29178 | 5565 | 40 | 4489 | 4341 | 4404 | −17.9 | 11.7 | χ 2 , df=2, T=34.7(5% 3.8) |

| Khvalynsk II | ||||||||||

| Skel. 1 | Human M | PSUAMS-4032 | 5760 | 25 | 4697 | 4539 | 4612 | −20.1 | 15.6 | |

| Skel. 1 | Human M | Univ. Bradford | −20.2 | 14.8 | ||||||

| Skel. 2 | Human F | PSUAMS-2902 | 5975 | 25 | 4940 | 4790 | 4859 | −21.9 | 15.4 | |

| Skel. 4 | Human M | PSUAMS-2903 | 5965 | 25 | 4938 | 4737 | 4846 | −21.0 | 15.6 | |

| Skel. 6 | Human F | PSUAMS-4250 | 6085 | 25 | 5204 | 4905 | 5002 | −22.2 | 14.8 | |

| Skel. 7 | Human M | PSUAMS-4148 | 5900 | 25 | 4836 | 4715 | 4767 | −21.1 | 15.9 | |

| Skel. 7 | Human M | Univ. Bradford | −20.9 | 15.3 | ||||||

| Skel. 10 | Human F | PSUAMS-4149 | 6150 | 25 | 5209 | 5006 | 5109 | −23.4 | 14.7 | χ 2 , (humans): df=1, T=15.9(5% 3.8) |

| Skel. 10 | Human F | OxA-4311 | 5790 | 85 | 4839 | 4451 | 4641 | −20.3 | 14.0 | |

| Grave 10 | Cow bone | GrA-34100 | 5570 | 40 | 4491 | 4342 | 4406 | −20.0 | 7.5 | χ2 (paired), df=1, T=151.8(5% 6.0) |

| Skel. 12 | Human M | AA-12572 | 5985 | 85 | 5207 | 4681 | 4885 | −21.5 | χ2, df=1, T=0.1(5% 3.8) | |

| Skel. 12 | Human M | PSUAMS-4031 | 5960 | 25 | 4936 | 4730 | 4839 | −20.8 | 15.6 | |

| Skel. 12 | Human M | Univ. Bradford | −20.4 | 15.2 | ||||||

| Skel. 13 | Human M | PSUAMS-4200 | 5985 | 25 | 4945 | 4792 | 4871 | −21.7 | 16.1 | |

| Skel. 17 | Human M | PSUAMS-4033 | 6070 | 25 | 5198 | 4853 | 4976 | −22.3 | 14.5 | |

| Skel. 17 | Human M | −22.2 | 13.8 | |||||||

| Skel. 18 | Human M | OxA-4314 | 6015 | 85 | 5208 | 4715 | 4922 | −22.4 | 13.6 | χ2, df=1, T=1.6(5% 3.8) |

| Skel. 18 | Human M | PSUAMS-2906 | 6125 | 20 | 5209 | 4958 | 5079 | −21.8 | 14.2 | |

| Skel. 19 | Human F | PSUAMS-4151 | 6260 | 25 | 5311 | 5084 | 5250 | −23.4 | 16.2 | |

| Skel. 22 | Human M | PSUAMS-4153 | 5950 | 25 | 4929 | 4726 | 4826 | −21.0 | 16.3 | |

| Skel. 23 | Human M | Univ. Bradford | −20.6 | 14.2 | ||||||

| Skel. 24 | Human M | OxA-4312 | 5830 | 85 | 4900 | 4460 | 4686 | −20.2 | 13.8 | χ2, df=1, T=3.4(5% 3.8) |

| Skel. 24 | Human M | PSUAMS-4154 | 5995 | 25 | 4983 | 4795 | 4882 | −21.1 | 16.1 | |

| Skel. 25 | Human F | PSUAMS-4162 | 5730 | 25 | 4678 | 4494 | 4576 | −20.8 | 16.6 | |

| Skel. 26 | Human M | PSUAMS-4163 | 6100 | 25 | 5206 | 4935 | 5032 | −21.9 | 16.9 | |

| Skel. 27 | Human M | PSUAMS-4304 | 6000 | 25 | 4987 | 4797 | 4888 | −21.9 | 16.3 | |

| Skel. 28 | Human M | PSUAMS-4545 | 5820 | 25 | 4783 | 4555 | 4676 | −20.5 | 15.6 | |

| Skel. 29 | Human M | PSUAMS-4150 | 5840 | 25 | 4789 | 4613 | 4708 | −21.1 | 16.6 | |

| Skel. 30 | Human M | AA-12571 | 6200 | 85 | 5359 | 4935 | 5140 | −20.5 | removed from model χ2, df=1, T=6.0(5% 3.8) |

|

| Skel. 30 | Human M | PSUAMS-4223 | 5985 | 25 | 4945 | 4792 | 4871 | −21.5 | 15.7 | |

| Skel. 31 | Human M | PSUAMS-4305 | 5930 | 25 | 4889 | 4722 | 4799 | −21.6 | 15.5 | |

| Skel. 32 | Human F | Univ. Bradford | −21.1 | 15.4 | ||||||

| Skel. 33 | Human M | PSUAMS-4164 | 5640 | 25 | 4540 | 4369 | 4466 | −21.3 | 15.3 | |

| Skel. 34 | Human M | OxA-4313 | 5920 | 80 | 5001 | 4555 | 4802 | removed from model χ2, df=1 T=4.3(5% 3.8 |

||

| Skel. 34 | Human M | PSUAMS-4306 | 6095 | 25 | 5206 | 4909 | 5022 | −22.6 | 15.5 | |

| Skel. 35 | Human M | PSUAMS-4155 | 6150 | 25 | 5209 | 5006 | 5109 | −22.9 | 15.1 | χ2, df=1, T=1.7(5% 3.8) |

| Skel. 35 | Human M | OxA-4310 | 6040 | 80 | 5209 | 4729 | 4953 | |||

| Skel. 38 | Human M | PSUAMS-4156 | 5755 | 25 | 4695 | 4508 | 4607 | −20.9 | 16.2 | |

Radiocarbon chronology and stable isotopes

Twenty radiocarbon dates were previously published from Khvalynsk: ten from Khvalynsk I and ten from Khvalynsk II (Table 1). Most were in Russian-language publications (Agapov et al. 1990: Table 5; Anthony 2007: Table 9.1; Shishlina et al. 2009; Chernykh and Orlovskaya 2010; Mathieson et al. 2018). Some dates were reported from the Soviet-era laboratory UPI, which operated briefly in Ekaterinburg in the 1980s, but never was included in the journal Radiocarbon’s global list of current and former radiocarbon laboratories. The 20 published dates are compiled here for the first time. Also, 28 new dates are presented here for the first time.

For Khvalynsk I, the ten dates previously published were from the Kiiv, UPI, and Groningen laboratories (Table 1). Three dates on shell beads are clearly subject to a variable freshwater reservoir effect; they are usually ignored in discussions of Khvalynsk chronology. Four new dates from the Pennsylvania State University Accelerator Mass Spectrometry laboratory (PSUAMS) are presented here, making 14 dates from Khvalynsk I. For Khvalynsk II, eight dates were published previously by the Oxford, Groningen, and Arizona laboratories, and two dates by PSUAMS (Mathieson et al. 2018). To these ten previously published dates we now add 24 new PSUAMS dates from Khvalynsk II, making 34 dates from Khvalynsk II (Table 1). Table 1 presents 48 dates for the Khvalynsk cemetery, 34 from Khvalynsk II and 14 from Khvalynsk I, including 28 new dates. In addition, Table 1 presents data on dietary stable isotopes (δ13C and δ15N) from 30 individuals, not all dated by radiocarbon.

Most of the dates are on human bones or teeth. This is a problem, because studies by Shishlina and van der Plicht have shown that radiocarbon dates from Eneolithic human bones can be more than 1000 years too old in this region, a result of freshwater reservoir effects (FRE) (Shishlina et al 2009, 2017). Therefore, most of the radiocarbon dates in Table 1 are skewed too old.

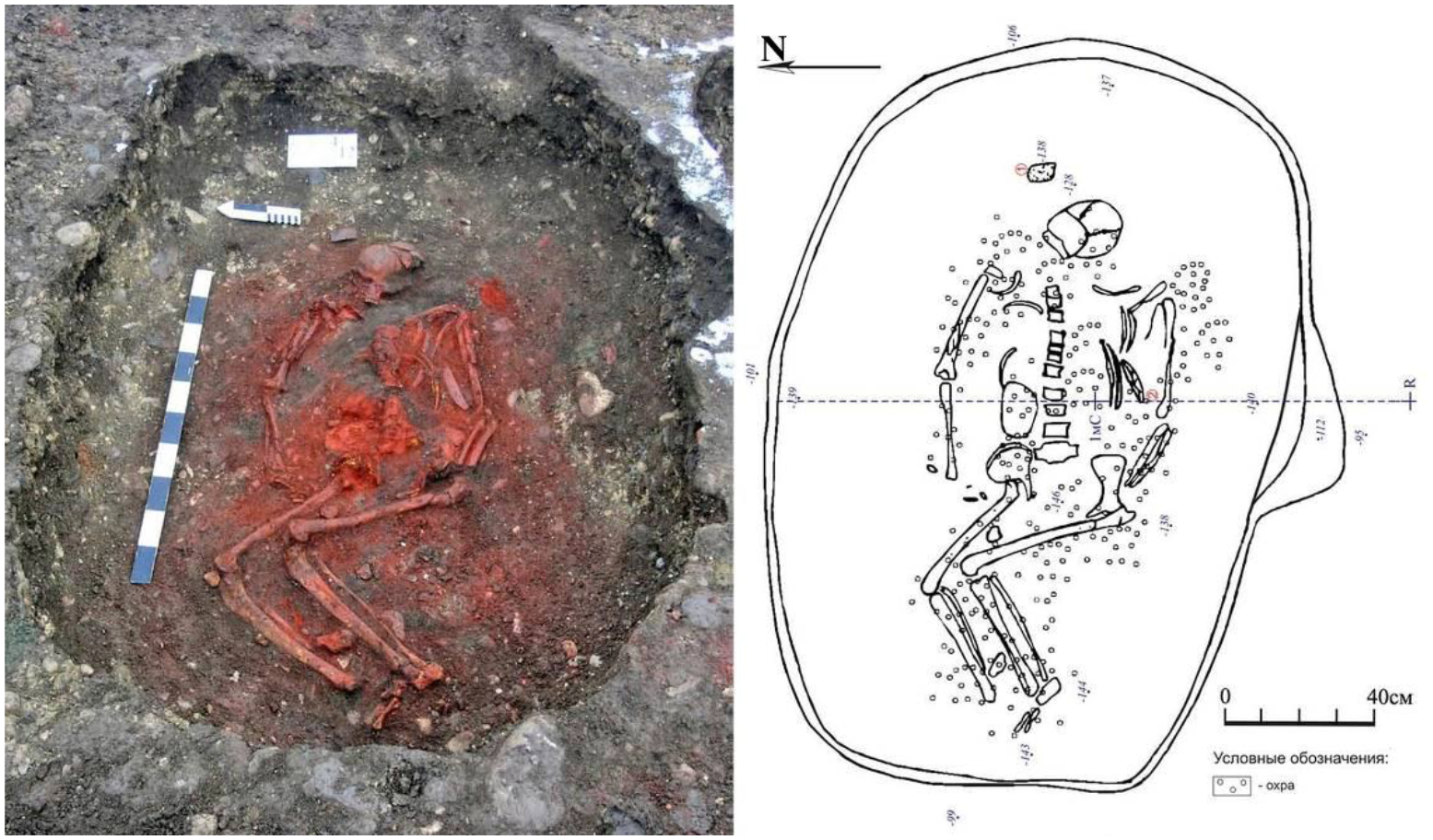

We have direct evidence of such skewing from two graves published by Shishlina et al. (2009), one at Khvalynsk I and the other at Khvalynsk II, with radiocarbon dates from domesticated cattle and sheep bones, not subject to reservoir effects (Shishlina et al. 2009: Table 8). Calibrated, the two samples produced statistically the same age: 4450–4350 BCE. A date of 4450–4355 BCE was obtained on a ring made of sheep bone (GrA-29178, 5565±40 BP) from grave 147 at Khvalynsk I (Figure 5). The human female buried with this bone ring was dated 4789–4618 BCE (PSUAMS 2886, 5845±25 BP), about 300 years older (Table 1). The second date, 4448–4362 BCE (GrA-34100, 5570± 40 BP), was obtained on a cow bone from grave 10 at Khvalynsk II. The human female in this grave was dated by Oxford to 4730–4530 BC (OxA-4311, 5790±85 BP), about 300 years older; but recently has been re-dated to 5210–5017 BC (PSUAMS 4149, 6150 ±25 BP), about 600 years older than the cow bone in the same grave (Table 1). It seems possible that a mistake was made in labeling one of these two human samples, but in any case, we can be confident that both came from Khvalynsk II.5

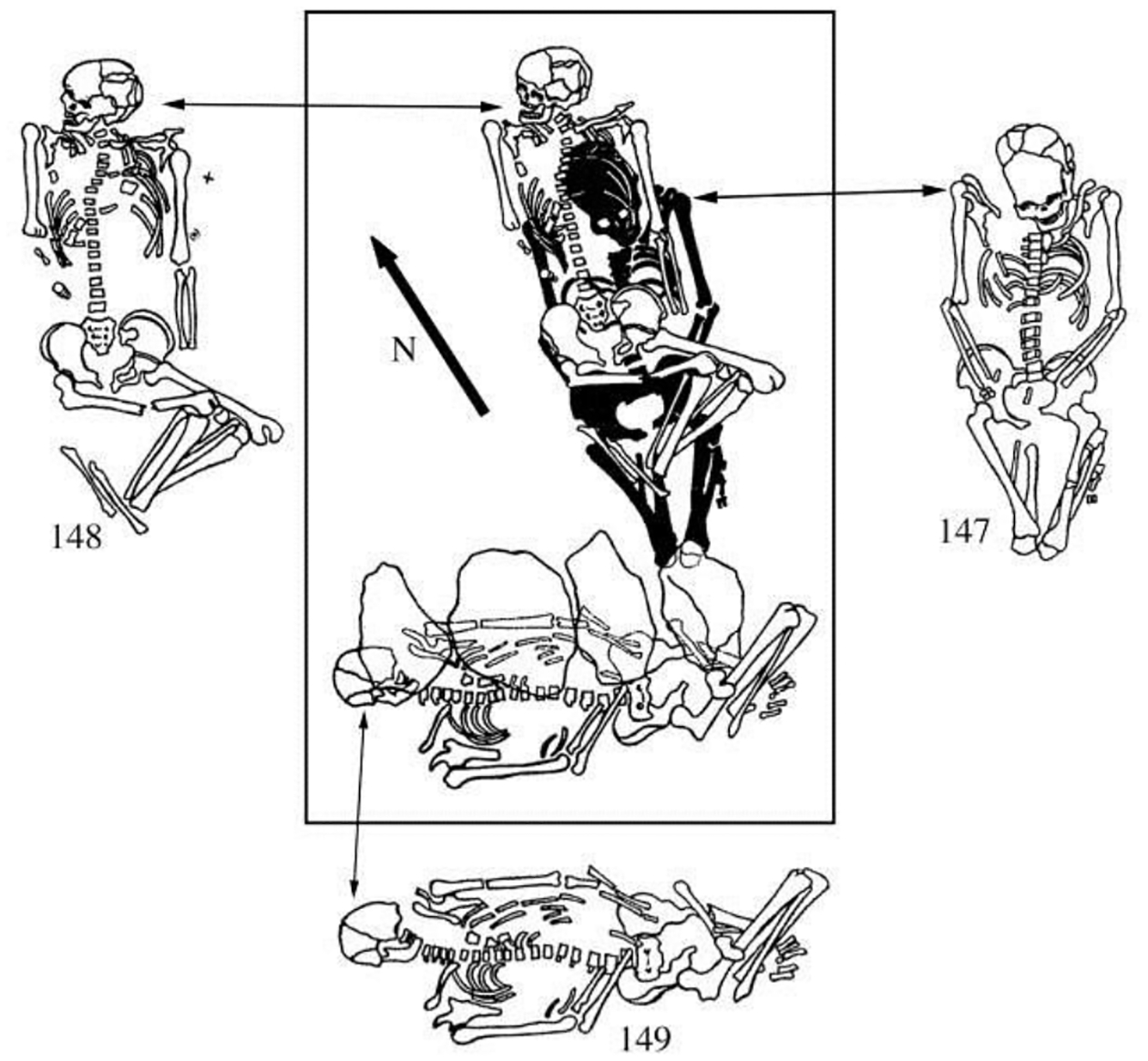

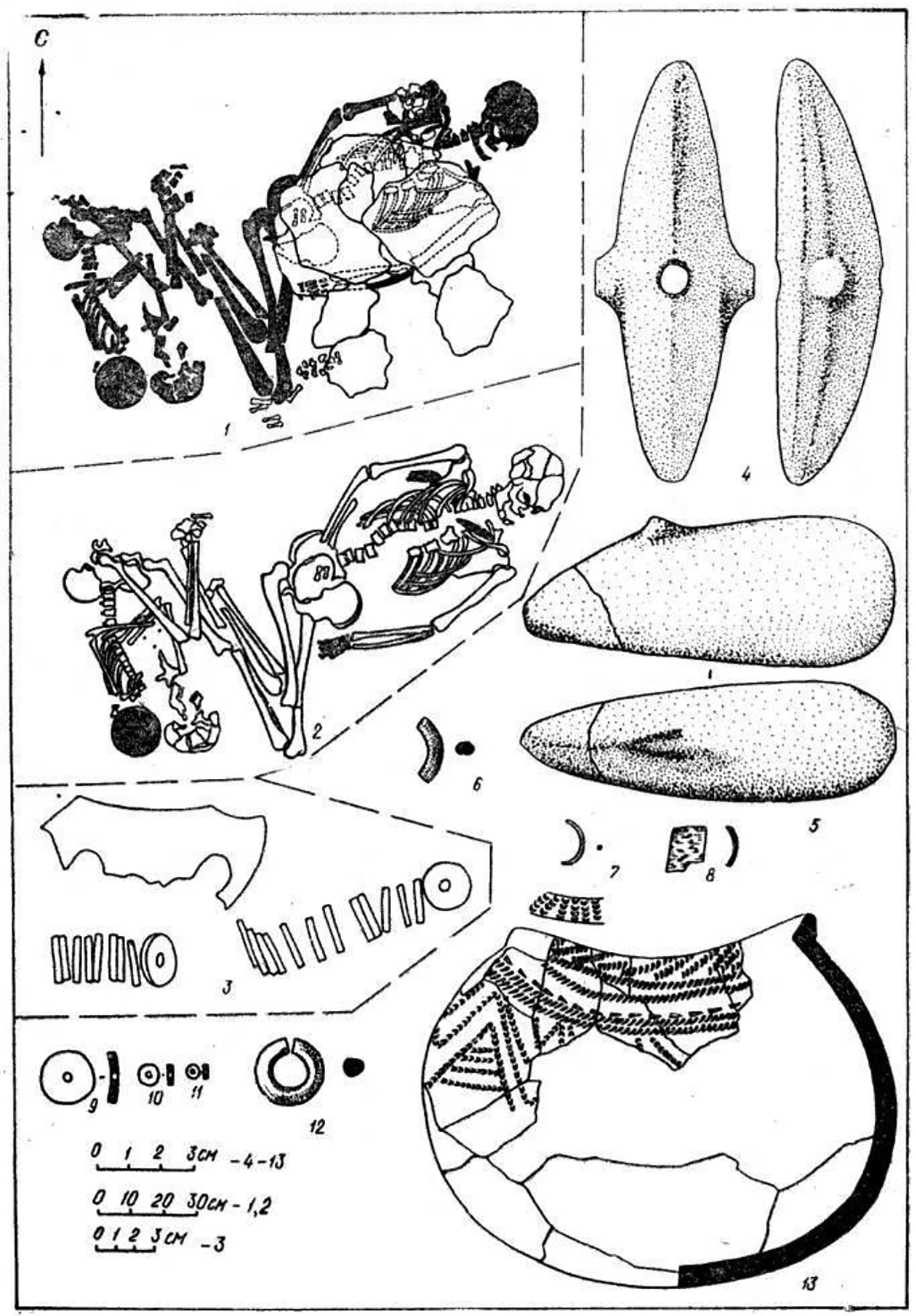

Figure 5.

Skeletons 147–149 at Khvalynsk I. Individual 147, a female aged 40–50 with red ochre around her pelvis, had a bone ring made of sheep-goat bone that gave a radiocarbon date not affected by reservoir effects. Directly above 147 was 148, a male aged 30–40 with no red ochre, and at their feet was 149, a male aged 50–65 with no ochre, covered by flat stones. For a plan of the cemetery & location of 147–149 see Figure 15. After Agapov et al. 1990: Figure 22.

The offsets between faunal and human dates from the same grave indicate the presence of an FRE, in which consumption of aquatic resources (fish, shellfish, aquatic birds) leads to the incorporation of ‘old carbon’ into human tissues (Philippsen 2013). Therefore, the faunal dates of 4450–4355 calBCE from Khvalynsk I and 4448–4362 calBCE from Khvalynsk II provide the best estimate currently available for the true age of the two cemeteries. If we compare the midpoint of these dates, ca. 4400 calBCE, to the midpoints of the calibrated age ranges for the humans, the resulting offsets range between 43 yr (essentially no offset given the inbuilt uncertainty in radiocarbon dating) and 860 yr, with a mean FRE offset of 401 ± 288 yr (Table 1).

The details of the genetically-determined family trees at Khvalynsk are examined below (Figure 18). Here our narrow purpose is to use family relationships as a chronological check on the FRE connected with radiocarbon dates. In three of the five families at Khvalynsk II (Grey, Purple, and Orange), individuals who were nearly contemporary (1st to 3rd degree relatives) have 14C dates more than 100 years apart, and the older 14C dates are associated with lower δ13C values. In the extreme case (Orange), a father and son are dated minimally 247 years apart (between the 95% confidence intervals of the two dates), and the older date is linked to a lower δ13C value. The dates for related individuals confirm that the 14C dates at Khvalynsk II do not identify contemporary graves, so they are not reliable relative to each other. However, in some related pairs of individuals the older 14C date (indicating depleted 14C) is from the individual with lower δ13C values (indicating depleted δ13C).

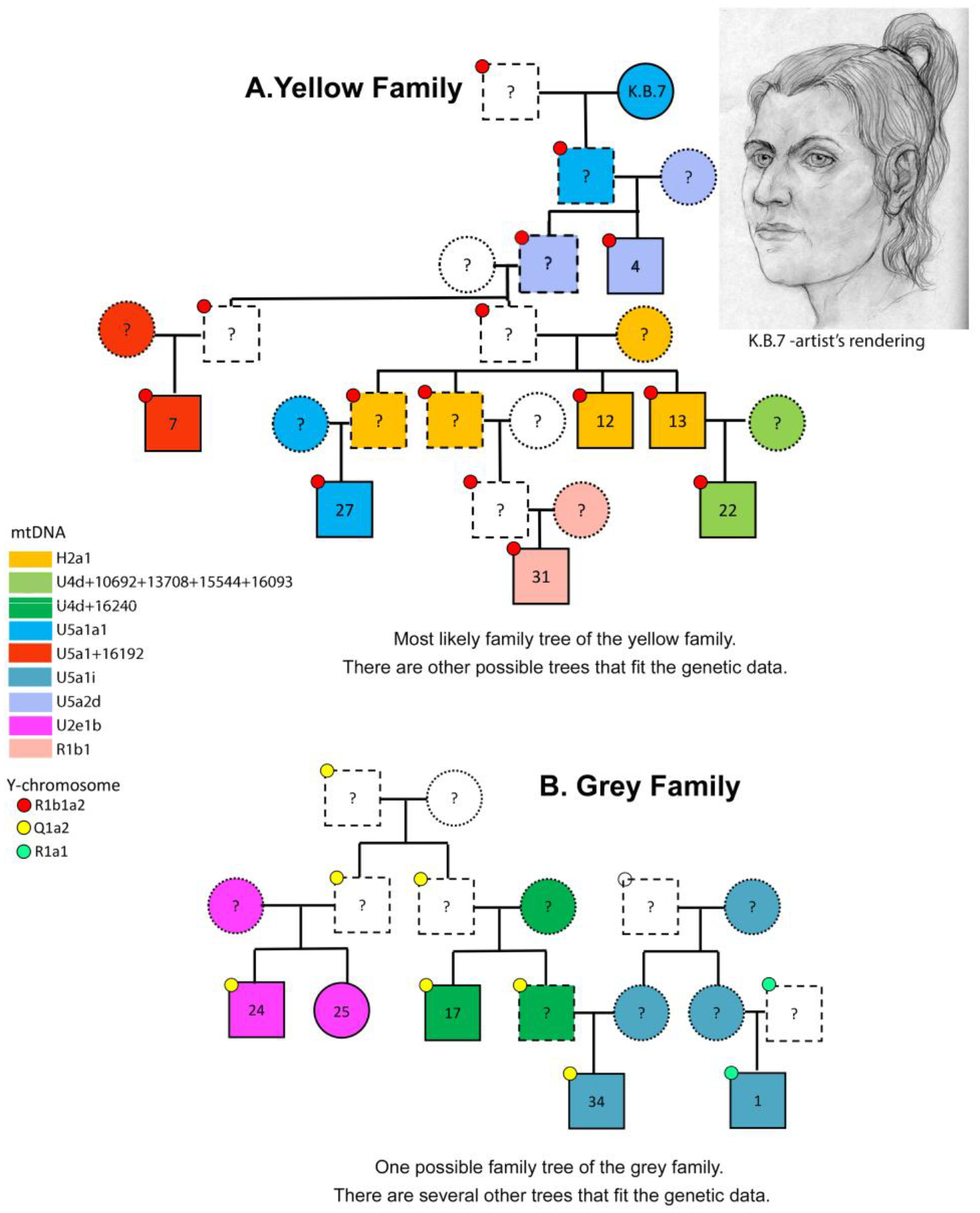

Figure 18.

Colors are mtDNA haplogroups, circles in upper left corner are Y-haplogroups according to color key at left. Dashed rectangle=missing male; dotted circle=missing female; solid rectangle=sampled male; solid circle =sampled female. A. Most likely family tree of the Yellow family, assuming KB7 is oldest; B. one of several equally plausible family trees of the Grey family. KB7 and grave 27 have the same mtDNA haplogroup but they were not related within 3 degrees so any relation was several generations back.

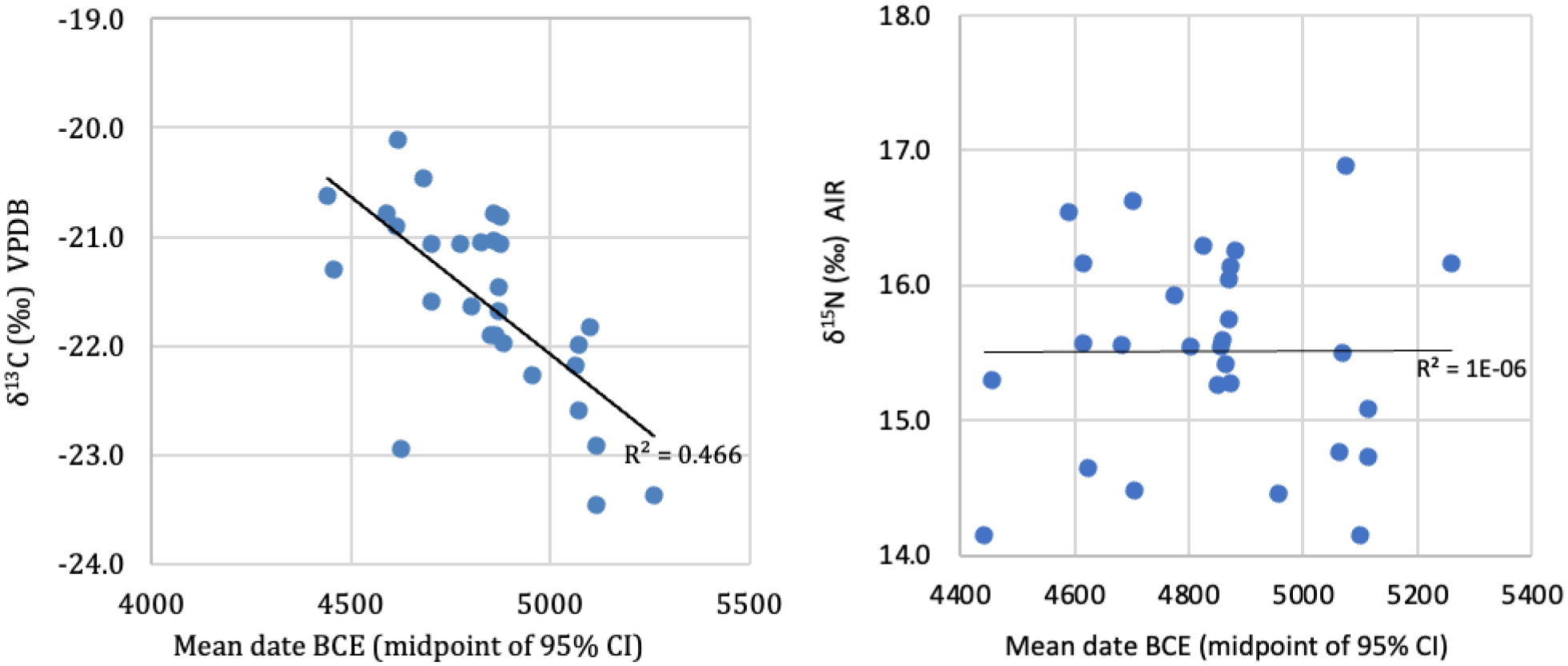

This is reflected in a moderate negative correlation between δ13C values and calibrated age, accounting for nearly half the variation in the latter (r2 = 0.474, p < 0.001, n = 29) (Figure 6a). There is a clear outlier (K-I, grave 17) with a predicted offset removed by nearly three standardized residuals from the assumed date of 4400 calBCE. Its removal improves the regression considerably (r2 = 0.663, p < 0.001, n = 28; the slope of the regression line remains similar). Extending the slope to the y-intercept suggests that a diet with no 14C offset would result in a δ13C value of ca. −20.3‰ (or ca. −20.0‰ if the outlier is excluded). In contrast, there is no relationship between δ15N values and calibrated age (r2 < 0.001, p = 0.995, n = 29) (Figure 6b). This is unexpected, since aquatic foods are typically significantly 15N-enriched compared to terrestrial flora and fauna (Anderson and Cabana 2007; Schoeninger et al. 1983), and therefore a positive relationship with radiocarbon offsets is often observed (e.g., Schulting et al. 2014). Since most of the analyses were made on the petrous bone, the core of which forms in infancy and does not remodel (Jørkov et al. 2009), it is possible that some samples retain a partial nursing signal (Schurr 1998), which could obscure the relationship between δ13C and δ15N values.

Figure 6.

Human δ13C (a: left) and δ15N (b: right) bone/tooth collagen values plotted against the midpoint of date cal BCE (95% confidence interval, CI) for 29 individuals from Khvalynsk I and II. Note that removing the outlier in the lower left of Figure 6a significantly improves the regression (r2 = 0.663).

However, the relationship between radiocarbon offsets and both δ13C and δ15N values is complex (Cook et al. 2001; Higham et al. 2010; Wood et al. 2013; Fernandes et al. 2015; Svyatko et al. 2015; 2017; Svyatko, Schulting et al. 2017). Aquatic systems are often 13C-depleted, as seems to be the case on the Volga, but they may also be elevated relative to C3 terrestrial ecosystems (Dufour et al. 1999; Katzenberg and Weber 1999). And fish from adjacent watersheds, or even different parts of the same river, can exhibit variable 14C offsets, leading to different relationships with both stable isotopes (Fernandes et al. 2015, 2016; Svyatko et al. 2017). In the Upper Lena river system north of Lake Baikal, Siberia, a program of paired human–fauna dating from the same graves identified a comparable relationship in which 14C offsets (of up to 1000 yr) were better predicted by δ13C values than by δ15N (Schulting et al. 2015). This differed from Lake Baikal itself, where both isotopes were significant predictors, but δ15N accounted for the larger amount of the variability in 14C offsets.

The implication of the variability in the FRE at Khvalynsk is that individuals were acquiring aquatic resources from different catchments, subject to different 14C reservoir offsets. This is consistent with the cranio-facial metric and genetic data indicating that the cemetery served for communities of different origins to the south and to the north, though it places this within a context of the immediate lifetimes of individuals rather than their more distant ancestry. One possibility is that such access was held within families or clans, as was the case with the best fishing places on the salmon rivers of the Interior Plateau culture area of northwestern North America (Romanoff 1992). If so, we might expect to see a link between the genetic ancestry evidence and the FRE offsets.

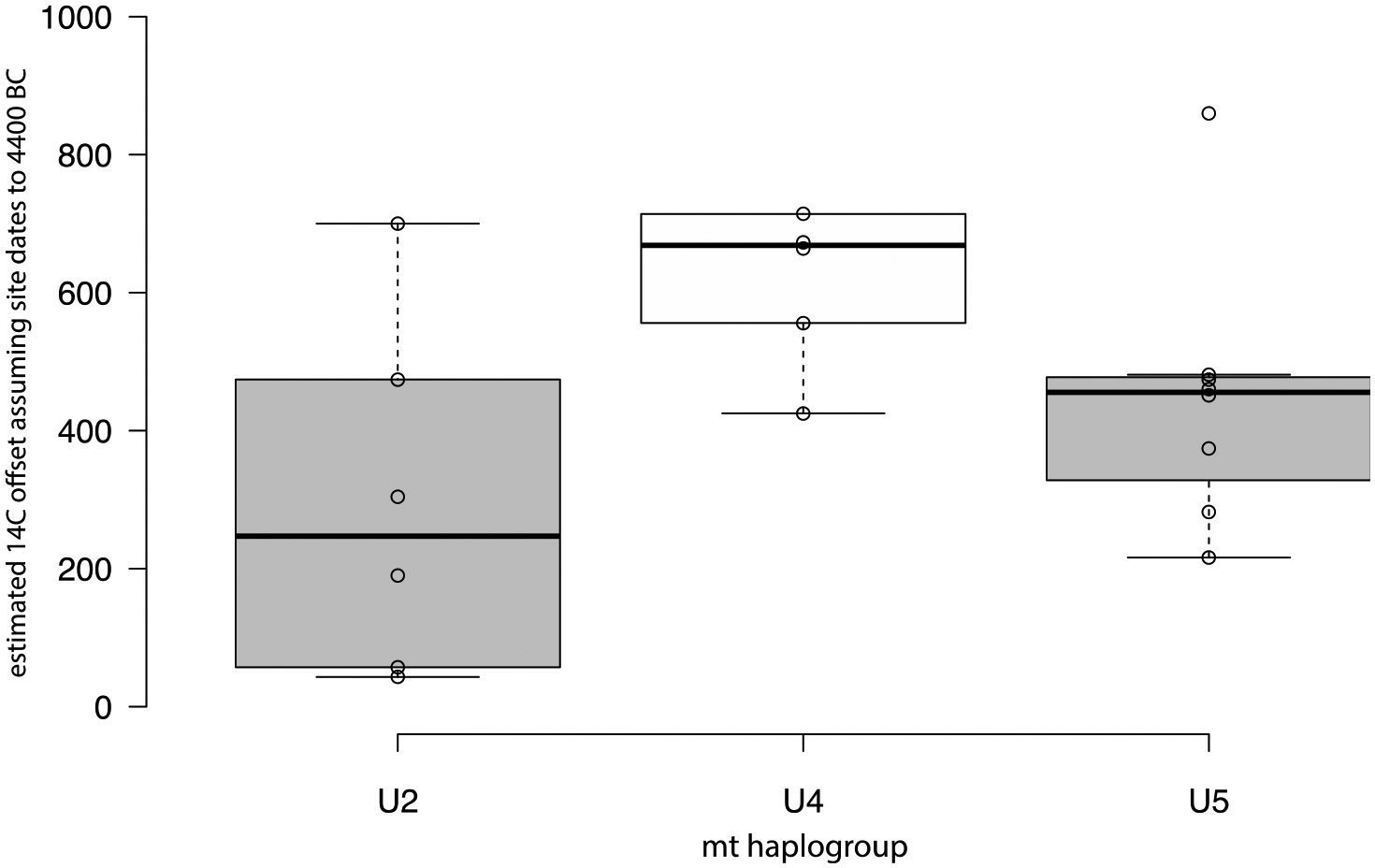

While this is not the case for Y-chromosome haplogroups, there is some indication of such a relationship between the estimated FRE offset and mitochondrial haplogroups. Limiting the comparison to haplogroups with more than five samples, the estimated mean FRE offsets relative to the faunal date of 4400 cal BC differ significantly for mt-haplogroups U2, U4 and U5 (ANOVA, F = 4.268, p = 0.031, n = 20). Bonferroni post-hoc tests show that the significant difference is between U2 and U4 (p = 0.029), with mean 14C offsets of 295 ± 256 yr and 624 ± 114 yr, respectively (Figure 7). Note that the same result would obtain if the means of the calibrated dates were used directly, since the same offset (i.e., from 4400 cal BC) is applied to all the individuals.

Figure 7.

Boxplots comparing mean 14C offsets for mt-haplogroups U2, U4 and U5.

The Volga River appears to have been depleted in both δ13C and 14C in some of its catchments, creating a mild correlation between older ages and lower δ13C in the bones of people who regularly ate Volga fish from those parts of the river. The maternal mtDNA haplogroup U2 (represented in two lineages, U2e1b and U2e2a) differed significantly from U4 in its smaller average FRE offsets (with U5 being intermediate), perhaps suggesting that U2 females came from a riverine catchment with less depleted δ13C and 14C. Females with U2 maternal ancestry occur in both Khvalynsk I and II (Table 6). The richest grave at Khvalynsk II contained an older brother (Khvalynsk II:24) and a younger sister (II:25) who carried U2 mtDNA ancestry.

Table 6.

Y and mtDNA haplogroups at Khvalynsk and the relative at Khlopkov Bugor.

| Lab ID | mtDNA haplogroup | Cemetery & grave # | Y-haplogroup v1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I6412 | H13a2a | Khvalynsk II, Grave 38 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6403 | H2a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 13 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I0122 | H2a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 12 | M | R1b-L754-L389-V1636 |

| I6402 | H2a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 29 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6738 | R1b1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 31 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6106 | T2a1b+723+10005 | Khvalynsk II Grave 2 | F | |

| I6102 | T2a1b | Khvalynsk I Grave 17 | F | |

| I6104 | U2e1a1 | Khvalynsk I Grave 127 | M | R1b-L754-L389 |

| I6407 | U2e1b | Khvalynsk II Grave 24 | M | Q1-L472-M25-YP1669 |

| I6734 | U2e1b | Khvalynsk II Grave 25 | F | |

| I6105 | U2e1b+8494+15287 | Khvalynsk I Grave 147 | F | |

| I6299 | U2e2a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 18 | M | Q1-L472-M25-YP1669 |

| I6739 | U2e2a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 33 | M | Q1-L472-M25-YP1669 |

| I6108 | U4a | Khvalynsk II Grave 6 | F | |

| I0426 | U4a+6524+9989+12308 | Khvalynsk II, Grave 32 | F | |

| I6735 | U4a+6524+9989+12308 | Khvalynsk II Grave 26 | M | J1-CTS1026 |

| I6408 | U4a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 35 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I11837 | U4a1+8155+13158+489+3780+13635 | Khvalynsk I Grave 40 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6741 | U4b1+293+13834 | Khvalynsk II Grave 30 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I0434 | U4d+16240 | Khvalynsk II Grave 17 | M | Q1-L472 |

| I6110 | U4d+16240 | Khvalynsk II Grave 10 | F | |

| I6406 | U4d+10692+13708+15544+16093 | Khvalynsk II Grave 22 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6109 | U5a1+16192 | Khvalynsk II Grave 7 | M | R1b-L754-L389 |

| I6404 | U5a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 19 | F | |

| I6736 | U5a1a1 | Khvalynsk II Grave 27 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6301 | U5a1a1 | Khlopkov Bugor, Grave 7 | F | |

| I6737 | U5a1a2 | Khvalynsk II Grave 28 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6740 | U5a1i | Khvalynsk II Grave 34 | M | Q1-L472-M25 |

| I0433 | U5a1i | Khvalynsk II Grave 1 | M | R1a-M459 |

| I6107 | U5a2d+146 | Khvalynsk II Grave 4 | M | R1b-L754-L389 |

| I6405 | U5a2d+146 | Khvalynsk II Grave 21 | M | R1b-L754 |

| I6103 | U5a2d+2244+9577+13886+16086 | Khvalynsk I Grave 30 | M | I2a-L699 |

The mean faunal date of 4400 calBC probably is the most accurate estimate of the midpoint date for the Khvalynsk cemetery. A relatively short span of time is suggested by the fact that 70% of the individuals analyzed from Khvalynsk II were related to other individuals in ways that could fit within a 5-or-6 generation span, or about 140–170 years (Figure 18). Stable isotopes indicate a diet in which riverine fish played a large role, causing a strong FRE in radiocarbon dates on human bones and teeth. Variation in δ13C seems to identify Volga riverine catchments that were depleted in carbon. δ13C also correlated with mtDNA haplogroups, suggesting that females at Khvalynsk came from different riverine catchments, while the men’s Y-haplogroups did not display such patterning.

Copper artifacts and trade

The two Khvalynsk cemeteries together yielded 373 copper objects, the largest assemblage of copper items from any Eneolithic cemetery in the steppes. Almost all were ornaments (beads, rings, or bracelets) made of hammered sheet copper or wire, bent into tubes and rings. Four melted lumps of copper in two graves at Khvalynsk II (Figure 8:1 and Table 3) were possibly unshaped, primitive trade ingots or possibly were evidence of local production (but Khvalynsk pyrotechnology probably was not sufficient for production, see below). Two similar lumps, interpreted as ‘ingots’, were found at Khvalynsk I in the ‘cultural stratum’, but were not associated with a specific grave (D. Agapov 2010: 263). As noted above, the number of copper objects at Khvalynsk I (35) was one tenth of the number at Khvalynsk II (338). The count of 338 objects from Khvalynsk II includes 332 preserved objects (D. Agapov 2010: 258) and an additional six copper stains/traces that were recorded during the excavation but could not be catalogued (D. Agapov 2010: Table 1). Similarly, the count of 35 from Khvalynsk I includes one grave distinguished only by a copper stain. It is necessary to include the stains to identify the individuals who had copper objects. At Khvalynsk I, 9% of the individuals (15/158) had copper objects on or near their bodies, about one in ten; and at Khvalynsk II 30% of individuals (13/43), about one in three. Adding the two cemeteries together, 28 individuals (14% of 201) had at least one copper object.

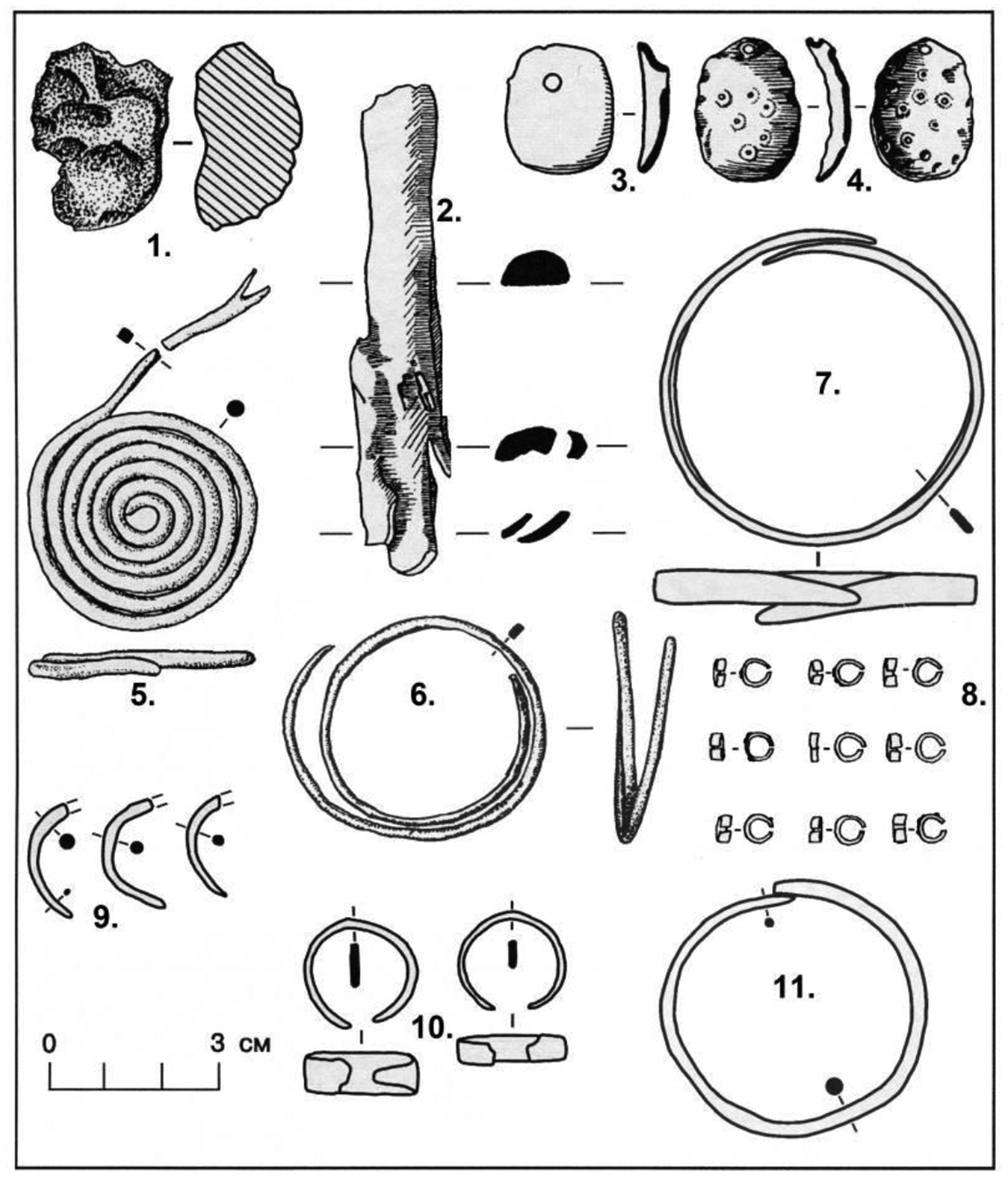

Figure 8.

Copper objects from Khvalynsk II. 1, grave 21; 2, grave 24; 3, grave 12; 4, grave 35; 5, grave 24; 6, sacrificial deposit; 7, grave 31; 8, grave 12; 9, grave 24; 10, grave 24; 11, grave 6. After D. Agapov 2010: Figures 8, 9, and 11.

Table 3:

All graves, with age and sex, containing animal sacrifices (by species), copper objects, and stone maces at Khvalynsk I and II. Does not include above-grave sacrificial deposits. Comments such as “burned” are from Agapov et al. 1990 text and Table 1.

| Skel. # | Sex age | Sheep-goat | Cattle | Horse | Copper | Mace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I: 7 | f 50–70 | X | ||||

| I: 11 | i 5–7 | X | ||||

| I: 19 | m 50–60 | 2 rings | ||||

| I: 30 | m 50–60 | 2 rings 2 beads |

||||

| I: 49 | m 40–50 | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 57 55 56 |

m 40–50 m 40–50 i 13–14 |

X | X burned | 2 rings | 1 cruciform mace |

|

| I: 64 | f 50–60 | X | ||||

| I: 67 | m 50–60 | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 68 | f 50–60 | 5 talus bones from 4 individuals | ||||

| I: 71 | f 40–50 | 2 linked rings | ||||

| I: 72 | f 40–50 | 2 linked rings | ||||

| I: 74 | f 15–20 | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 90 | i 10–14 | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 93 | i 6–10 | X burned | ||||

| I: 97 | f 60–70 | from 5 individuals | ||||

| I: 100 | i 4–6 | back leg of a lamb | X | |||

| I: 102 | m adult | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 104 | f 25–35 | 1 ring | broken tip | |||

| I: 106 | i 4–7 | X | ||||

| I: 108–110 | m adult | X | 1 ring | 1 eared mace 1cruciform mace |

||

| I: 113 | m 30–40 | X | ||||

| I: 115 | f 17–25 | 35 talus from 22 ind | ||||

| I: 123 | f 25–35 | 1 ring | ||||

| I: 126 | m 17 | vertebrae 2 individuals | ||||

| I: 127 | m adult | X | X | |||

| I:129 | f 20–25 | 1 ring 1 spiral |

||||

| I: 131 | m adult | X | ||||

| I: 132 | m adult | X | ||||

| I: 133 | i 10–13 | trace | ||||

| I: 139 | m 30–40 | X | X | |||

| I: 140–141 | m 45–55 f 30–35 |

1 skull | ? | ? | ||

| I: 143–144 | m 45–50 f 30–40 |

skull fragments of 8 individuals | X | |||

| I: 145 | m 40–60 | X | ||||

| I: 155 | f 11–15 | X | ||||

| I: 157 | m 50–60 | X | ||||

| Skel. # | Sex age | Sheep-goat | Cattle | Horse | Copper | Mace |

| II: 1 | m 30–35 | 1 ring 1 bead |

||||

| II: 2 | f 17–20 | trace | ||||

| II: 3 | i 4–5 | 1 pendant 1 curved sheet frag |

||||

| II: 6 | f 20–30 | X | 2 rings | |||

| II: 10 | f 55–65 | X | ||||

| II:12 | m 20–30 | 293 beads 2 rings 2 pendants |

||||

| II: 13 | m 25–35 | 2 rings 1 bead |

||||

| II: 14 | i 1 yr | X | 1 bead | |||

| II: 16 | i 1 yr | X | ||||

| II: 18 | m 45–55 | 1 ring | ||||

| II: 21 | m 50–55 | melted lump | Antler hammer | |||

| II: 24 | m 20–25 | X | 1 spiral pendant 3 melted lumps 8 rings 4 beads |

1 eared mace | ||

| II: 26 | m 17–22 | trace | ||||

| II: 31 | m 20–30 | 1 ring | ||||

| II: 35 | m 40–50 | 1 pendant | ||||

| II: 38 | M | X | X |

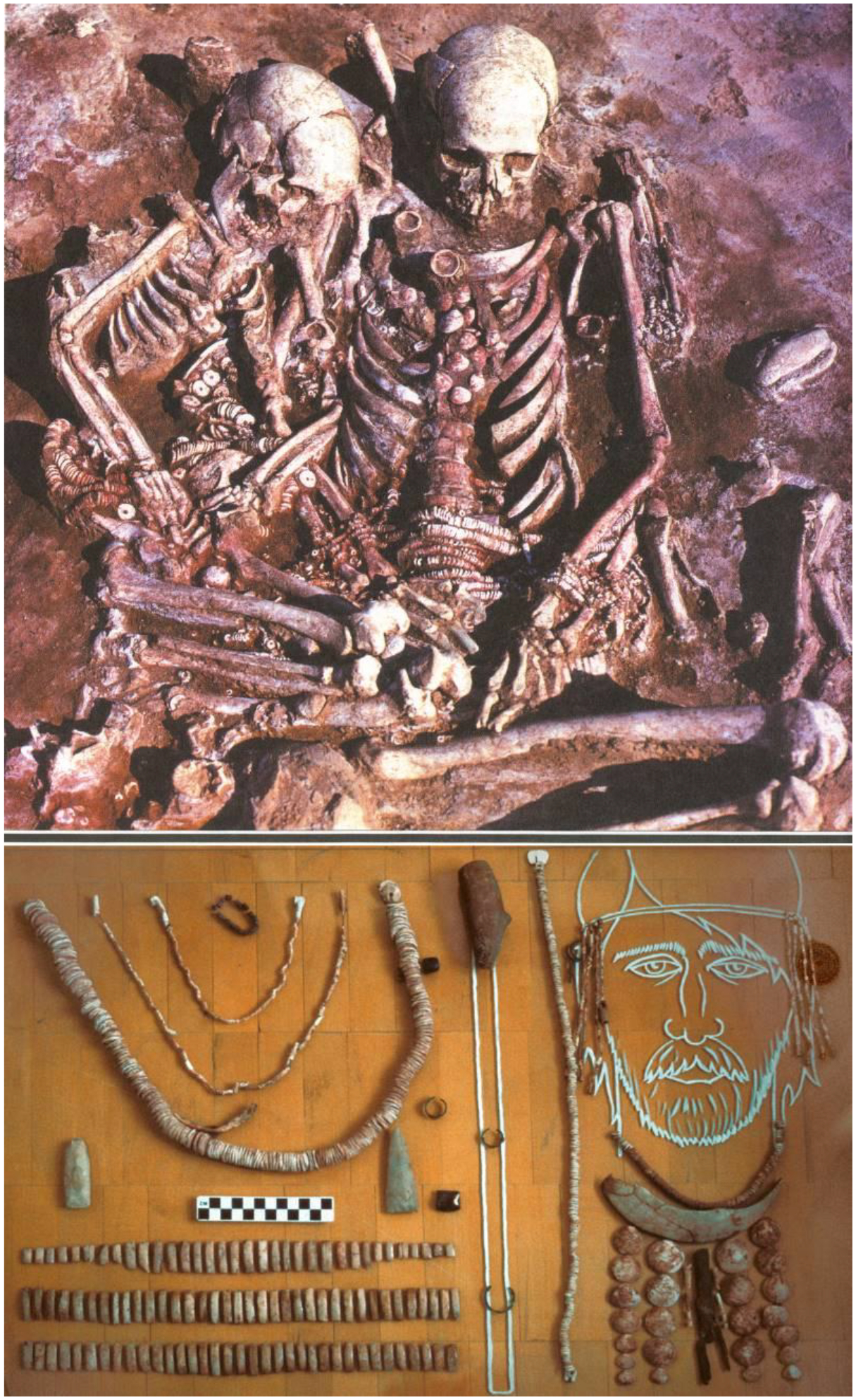

Within the 14% minority that had access to copper ornaments, most had one to four pieces (Figure 8). A single bead of copper was an important find at Khvalynsk; presumably, it was just as important to the person who wore it. Most of the pieces were combined into sets such as beads strung together or connected rings made into a hanging ornament. One male aged 20–30 in Khvalynsk II: grave 12 was buried with 297 copper objects, most of them (293) simple copper beads strung on at least two necklaces also adorned with small sheet-copper oval pendants (Figure 8: 8 & 3). This single individual had 80% of the copper objects found in both cemeteries combined. If we exclude grave II:12 to see if it alone was responsible for the difference between Khvalynsk I and II, Khvalynsk II still would have 41 copper objects, more than Khvalynsk I (35) in one third the number of graves. A higher proportion of graves at Khvalynsk II (1/3 compared to 1/10) contained copper objects, so even without II:12 the two cemeteries differed significantly in their access to copper.

The copper-rich male in grave II:12 was the brother of the male in II:13, and the uncle of the male in grave II:22, who was the son of II:13 (family relationships below). The brothers in II:12&13 were the center of a cluster of seven related males that included II:4, II:7, II:22, II:27, and II:31 as second or third-degree relatives (the Yellow family in Figures 17 and 18). This patriline accounted for one of seven individuals at Khvalynsk II, the largest single family identified, and modeling described below suggests that the relationships within it should be distributed over four or five generations, so it was a persistent presence over more than 100 years. Its wealth in copper could have been related to its central position in the male-dominated group buried at Khvalynsk II. No female relatives—no mothers, daughters, sisters, or female cousins of the seven related men were buried with them. Khvalynsk II could have been a burial place for a multi-generational male sodality or society engaged in long-distance expeditions that brought Balkan copper to the Volga. The paternally central man in II:12 had much more copper than anyone else at Khvalynsk.

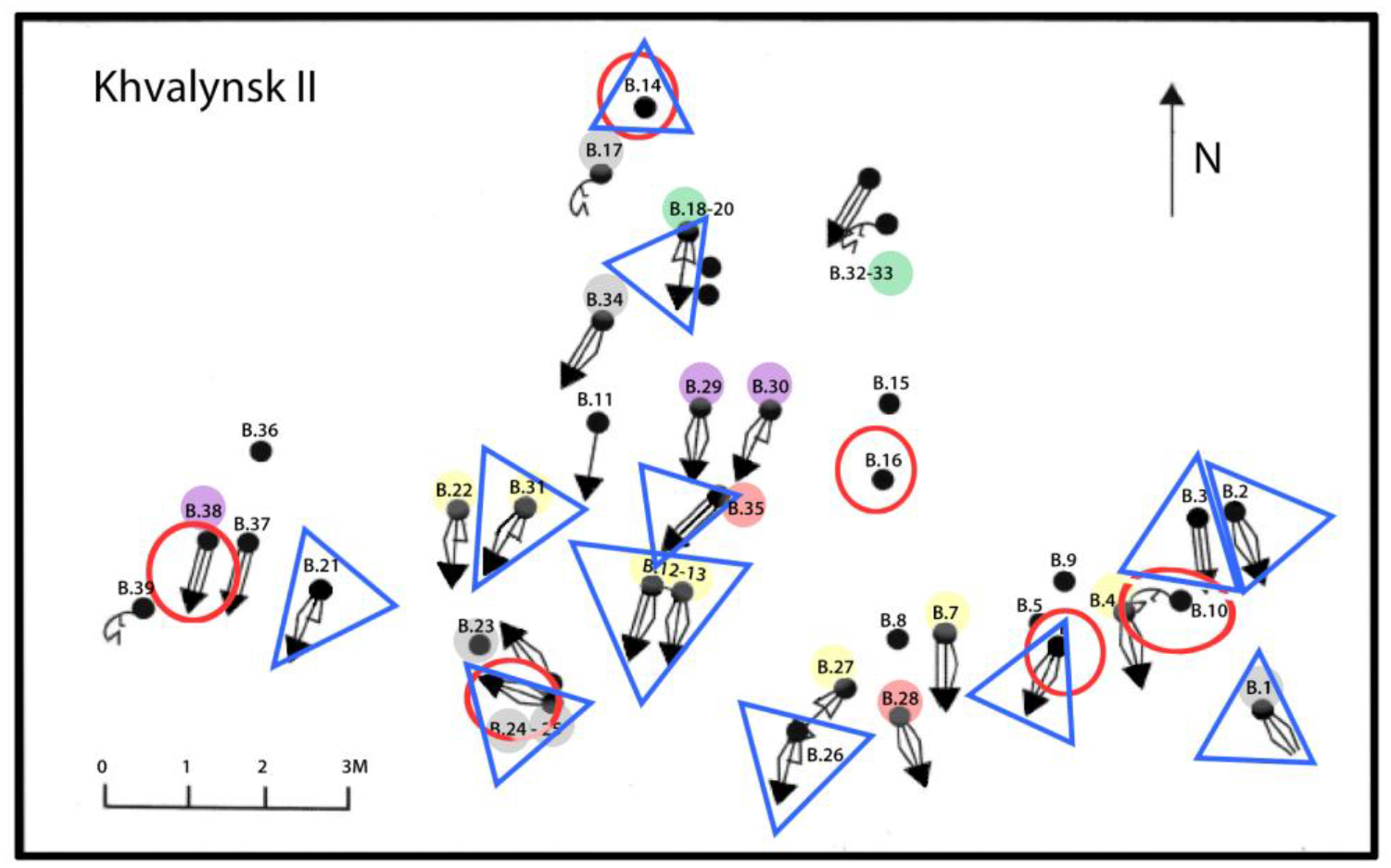

Figure 17:

Plan of Khvalynsk II with family relationships indicated by color superimposed on copper finds (blue triangle) and animal sacrifices (red circle). Icons with straight lines were supine with raised knees; icons with curved lines were half-sitting with raised knees; black circles were isolated skulls. Related individuals are color coded with six colors for six families. Table 5 describes the relationships. Adapted from D. Agapov 2010: figure 5.

Family relationships also might suggest that the beginning of the Balkan copper trade occurred suddenly on the Volga, with copper changing from absent to abundant over the span of two generations, between grandparent and grandchild. The male in grave II:4 was a second-degree relative of a female in grave 7 at Khlopkov Bugor (KB7), a Khvalynsk-culture cemetery 130 km south near Saratov. No copper was found at Khlopkov Bugor, so it is generally thought to be older than Khvalynsk, although the artifact and ceramic types are quite similar. (We established above that their radiocarbon dates are variably affected by FRE and cannot be relied on to indicate their relative age.) If Khlopkov Bugor was older, then the Yellow-family female KB7 was a paternal grandmother or paternal aunt (given their different mtDNA haplogroups) of the male at Khvalynsk II:4. The chronological difference between them was no more than two generations, perhaps 50–60 years. If the absence of copper at Khlopkov Bugor is explained by its earlier position, then the copper trade began suddenly and abundantly when the Khvalynsk cemetery began to be used, about 4500 BCE.

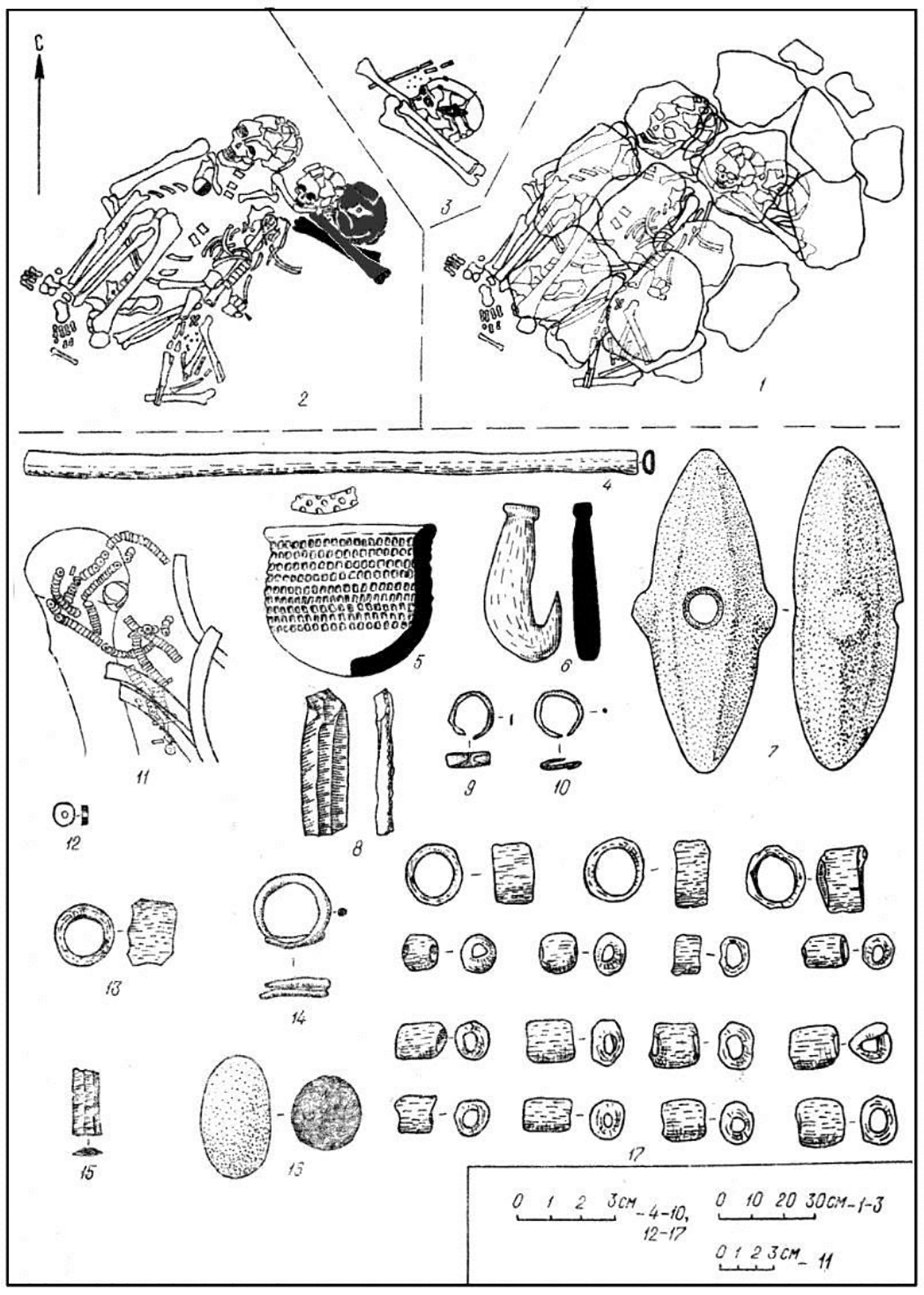

An artifact linked to the copper-using minority was the bird-bone tube, possibly used as a flute or whistle (Figures 9, top right; & 11). With one exception (II:4, the Yellow-family male related to KB7) bird-bone tubes appeared only in graves with copper ornaments, and only with adult males, or in one case, an adolescent buried with an adult male (I: 90 & 91, see Figure 9 top). They were not modified to create musical notes—they had no holes—so their function is uncertain. At Khvalynsk I, graves 19, 30, 57 (Figure 11), and 90 (Figure 9) had bird-bone tubes (Agapov et al. 1990: 60 n.), and Table 3 shows that all these graves contained copper ornaments with a male (or an adolescent). At Khvalynsk II, only grave 24 was described by the zoologist Bogatkina (2010: Table 1) as containing a bird-bone tube, and this was the richest grave at Khvalynsk, discussed below, belonging to a male equipped with many copper items. The Moscow zoologist Kirillova (2010: 363–366) found five more bird-bone tubes in collections that had moved to Moscow, from four graves at Khvalynsk II:4, 13 (two tubes), 18, and 35. All nine individuals in both cemeteries with bird-bone tubes were adult males (or an adolescent buried with an adult male), and all but one (II:4) were buried with copper artifacts (Table 3). It interesting that II:4 is modeled in the Yellow family relationships as the oldest Yellow family grave at Khvalynsk II, so perhaps the copper trade had not yet started when II:4 died. Kirillova specified that the bones were ulnas from large birds, which she tentatively identified as a swan, a white-tailed eagle, and three bones that were in the size class of swan-crane-bustard, among locally available large birds. Two of the three mace graves at Khvalynsk (see below) contained bird-bone tubes, which seem to have symbolized an office or status among the copper-using men (and one boy) at both Khvalynsk I and II. This restriction in the use of bird-bone tubes was one of many shared customs that connected I and II in the same ‘culture’.

Figure 9:

Khvalynsk I plan and objects. Top: cemetery plan and Sacrificial Deposit 4 containing bones of 2 cattle, 1 sheep-goat, & 1 horse above Graves 90 & 91 with bird-bone tube, harpoon (see Fig.1), flint blades, and copper ring. Middle: grave artifacts including the broken mace and whole mace from grave I:108, a polished stone bracelet probably from the North Caucasus, & fossil Glycemeris shell ornaments; Bottom: ceramic pots and bowls from Khvalynsk I. From Anthony 2007: Figure 9.7.

Figure 11.

Mace chief grave, Khvalynsk I: 57. 1, surface pavement of flat stones above skeletons 55–57. 2, mace-chief 57 in black, beneath individuals 55 & 54. 3, mace chief 57 with mace on skull. Objects found with 57: 4, bird-bone tube. 5, miniature ceramic cup. 6, bone hook. 7, polished stone cruciform mace. 8, 15, flint blades. 9, 10, 14, copper rings. 11,12, Unio shell bead & string of Unio beads on humerus. 13, 17, bone rings or large bone beads. 18, abraded stone used as polisher. After Agapov et al. 1990: Figure 18.

Balkan ores probably were the source of the copper imported to Khvalynsk, although most of the imported metal was worked into rings and beads by local artisans. A Balkan source is surprising given the distance (2000 km) between Khvalynsk and the lower Danube valley. But ‘clean’ Balkan ores, specifically copper ores of groups B1-B2 and B3-B6 from Ai Bunar in Bulgaria, match the trace elements in Khvalynsk copper better than Caucasus ores do (Ryndina 2010: 242–243; D. Agapov 2010). Courcier argued that relatively ‘clean’ copper ores also were found in the Caucasus in some Chalcolithic artifacts, as at Menteshtepe (Courcier 2014: 596). But the Menteshtepe ‘clean’ copper had trace amounts of arsenic measured in the high tenths of one percent (range 0.6–0.9% arsenic). E.N. Chernykh analyzed 41 copper objects from Khvalynsk with methods capable of detecting arsenic, and only ten (12.2%) had any arsenic trace elements; more than 80% had no detectable arsenic. Of the ten exhibiting some arsenic, seven were in the range 0.0034–.1% (Chernykh 2010: Table 2), like the copper from Cucuteni-Tripolye sites, which ranged 0.007–0.1% (Chernykh 2010: Table 6). The trace elements in 70% of the tested Khvalynsk copper objects with arsenic fell into the range of the trace elements in Balkan copper rather than Caucasian copper. Three of the ten tested objects had arsenic outside the range of the tested Balkan copper objects, but not by very much: 0.2, 0.3, and 0.42. These three rings all were worn by adult females. Their slightly elevated arsenic might have resulted from a mixture with copper from Caucasian ores, so might indicate trade with the south.

‘Clean’ oxide copper ores are abundant locally in the Volga-Ural steppes (Figure 10), not far from Khvalynsk, but ore mining and smelting probably was not yet possible locally during the Eneolithic. To smelt copper from a multi-mineral sandstone ore usually requires charcoal heated to 1200–1300 °C, much higher than the maximum temperature (700–800 °C) attained in making Khvalynsk ceramics (Vasilieva 2010: 164). Khvalynsk pyrotechnology probably was not sufficient to smelt local copper oxide ores, which began to be mined in the Yamnaya period, by present evidence (Chernykh and Isto 2002). Eneolithic experimentation with metallurgy ultimately led to the beginning of extractive copper ore mining and productive metallurgy in the steppes during the fourth millennium BCE.

Figure 10.

Multi-mineral sandstone copper oxide ore with malachite and azurite in an eroded ravine exposure 8km west of Mikhailovka Ovsianka (Mikhaylo-Ovsyanka in GoogleEarth), Samara oblast, Volga-Ural steppes. Mining began here in the Bronze Age. Photo by D. Anthony and D. Brown 2000.

At least five copper ornaments examined by Ryndina were made at temperatures of 900–1000° C and must have been imported as finished objects; three of these were spiral rings like ornaments at Varna (Ryndina 2010: 239–240). But most of the other copper beads and rings were shaped at temperatures between 300–800° C, were rather crudely finished, and seem to have been bent and welded into shape locally (but using imported metal). Ryndina (2010) noted that the methods used for wire-making and welding on the Khvalynsk copper artifacts seem to have been copied after the methods used by Tripol’ye A and B1 metalsmiths, including the same welding method (adding a small strip of heated copper), but the Khvalynsk artisans used lower working temperatures, their work was cruder, and their welds often failed to join completely. One individual at Khvalynsk II: 21 was named ‘the smith’ by the excavators because his grave contained an unworked lump of copper (Figure 8:1), an antler hammer and a grooved stone hammer that might have been used to make sheet copper, and a beaver incisor that could have been used as an edge tool to cut sheet copper. He was not related to any of the known families at Khvalynsk II but had similar genetic ancestry.

Rassamakin (1999) proposed that the Dnieper Rapids region emerged in this era as a secondary center of ‘Skelya-culture’ metalworking between Varna and the North Caucasus steppes. Most of the Khvalynsk copper is consistent with this kind of secondary source, among local steppe artisans. This could also be the source of a copper bead found at Svobodnoe, made of Balkan copper (Courcier 2014). Svobodnoe was one of a series of agricultural settlements established in the Kuban River drainage after 4700 BCE by immigrant farmers who crossed the North Caucasus peaks from Georgia (Wang et al. 2019). They participated in the trading network that brought Balkan copper into the steppes. Svobodnoe also produced many polished greenstone axes with faceted butts, like the axe found at Khvalynsk in grave I:105, probably made in the North Caucasus. A polished serpentine bracelet at Khvalynsk found in grave I: 8 probably was made in the North Caucasus (Figure 9: middle panel); it was like bracelets at Nalchik. The Khvalynsk population was active in inter-regional exchange systems (Danube-Dnieper-Caucasus-Volga) that were stimulated by the heightened production of Balkan copper after 4500 BCE.

Animal sacrifices: a new funeral cult

A complete zoological report on the Khvalynsk fauna has not been published, but partial descriptions are contained in four sources (Petrenko 1984: 48, 70; Agapov et al. 1990: 8–9, 60, 65, Figure 3, Tables 1&2; Kirillova 2010; Bogatkina 2010). These sources occasionally contradict each other. We arrived at the numbers presented in this text and in Tables 3 and 4 by following this rule: where one source contradicted another, Bogatkina (2010) was authoritative for the Khvalynsk II fauna, and Agapov et al. (1990: Tables 1&2) for the Khvalynsk I fauna. Bogatkina (2010) and Morgunova (2014: Table 18) attempted to re-count the Khvalynsk I fauna, but both gave numbers much smaller than Agapov et al. (1990: Tables 1&2). They apparently described only the Khvalynsk I bones that survived in the Samara laboratory in the early 1990s. The faunal data in the original 1990 report must be presumed to be accurate. That report had no separate chapter by the site zoologist, A.B. Petrenko, but she is credited on the first page where fauna is described (Agapov et al. 1990: 8), and the animal bones are identified to taxa and briefly described within the text by grave number or sacrificial deposit (bones found in ochre-stained deposits above the graves at both I and II). Summary tables of the fauna from the graves (Agapov et al. 1990: Table 1) and above-grave sacrificial deposits (Agapov et al. 1990: Table 2) provide only the number of individuals, not the number of bones, which was not reported for Khvalynsk I. Therefore, to compare I and II, we can use only the number of individuals, as in Table 2.

Table 2:

Fauna in graves and sacrificial deposits at Khvalynsk I and II, MNI only. Compiled from the sources listed in the first sentence of this section.

| Khvalynsk I sacrificial deposits | Khv I graves | Khvalynsk II sacrificial deposits | Khv II graves | Total MNI | Percent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 10 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 29 | 19.2% |

| Sheep-goat | 29 | 44 | 4 | 29 | 106 | 70.2% |

| Horse | 4 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 16 | 10.6% |

| Total | 43 | 64 | 8 | 36 | 151 MNI |

Table 4.

Ekaterinovka Mys radiocarbon dates. Intcal20

| Grave # | Lab | Sampled material | Age BP | calBC (95%) | δ13C | δ15N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grave 40 | PSUAMS 8194 | beaver incisor | 5750 ± 25 | 4686–4505 | −20.7 | 6.7 |

| grave 45 | PSUAMS 4568 | goat tooth | 5680±20 | 4550–4450 | Nd | |

| grave 101 | PSUAMS 8195 | sheep tooth | 6025 ± 40 | 5028–4798 | Nd | |

| Grave 60 | PSUAMS 8218 | marmot tooth | 5745±30 | 4689–4517 | Nd | |

| potsherd | SPb-2251 | organic residue | 5673±120 | 4795–4267 | Nd |

According to our interpretation of these sources, the animal bones recovered from Khvalynsk I and II represented the funeral sacrifices of at least 151 mammals. Three mammalian taxa were sacrificed: at least 106 domesticated sheep-goat (70%), 29 domesticated cattle (19%), and 16 horses (11%) whose domesticated status is debated. No obviously wild mammals were included in the funeral sacrifices, although wild species were represented in bone tools, ornaments, and flutes or whistles; and moose (Alces alces), red deer, horses, beavers, and fish were important in the diet at regional Eneolithic settlements (Vybornov et al. 2019; Morgunova 2014: Tables 19 & 20). At the Eneolithic Ivanovska settlement on the upper Samara River, dated 4360–4220 BCE (68%) (Ki-15086 5440±80 BP), with pottery of the ‘Samara’ type, distinct from Khvalynsk pottery, horses contributed 40.2% of the 6068 animal bones, domesticated cattle 11.4%, domesticated sheep-goat 7%, moose 17%, and beaver 22.5% (Morgunova 2014:Table 19), not counting fish or birds. Sheep-goat were ten times more frequent in the funeral deposits at Khvalynsk than at the Ivanovska settlement. However, in seasonal (winter?) camps containing Khvalynsk pottery on the lower Volga, as at Kair-Shak VI, dated 4400 BCE, sheep-goat were 60–70% of bones, and wild saiga antelope and onagers were 15% (Vybornov et al. 2019: Table 2). The sacrifices at Khvalynsk did not include the wild game animals that were prominent in the diet at both settlements. Instead, domesticated mammals were exclusively used to communicate with the spirit world.

What segments of domesticated mammals carried the prayers of the mourners? At Khvalynsk, horses were represented by one or two bones of the lower leg, usually a single phalange, in contrast to cattle and sheep-goats, which were represented by head and lower leg bones. Most of the described elements for cattle and sheep-goat were distal leg bones (principally metapodials and phalanges) and skulls, mandibles, or teeth (Agapov et al. 1990; Bogatkina 2010). Head and leg bones might be the result of ‘head-and-hoof’ deposits, in which the skin or hide of the animal with head and hooves attached is left at a ritual site as the symbol of the gods’ portion, while the meat is consumed by the human participants. Head and hoof deposits occurred throughout Eurasian steppe prehistory and into the modern era (Piggott 1962; Taylor et al. 2020). In the Eneolithic they are indicated at Khvalynsk and at another late 5th millennium BCE cemetery on the Samara River, a tributary of the Volga, at a site known as S’yezzh’e, containing ‘Samara’ style pottery, like Ivanovska. At S’yezzh’e parts of two horse heads and distal legs were found in an ochre-stained sacrificial deposit above nine Eneolithic graves, arranged in head-and-hoof offerings like the cattle and sheep-goats at Khvalynsk (Vasiliev and Matveeva 1979).

Where were the sacrificed animals deposited? About two thirds of the animal sacrifices at Khvalynsk were found in graves, associated with individual humans. These animal bones were connected to individual human deaths. One third of the sacrifices were in red-ochre-stained sacrificial deposits above the graves, possibly not connected with individual deaths but rather conducted for the public (Table 2, Figures 9 & 15). The sacrifices at S’yezzh’e were like these, in a red-ochre-stained deposit above the graves. Eleven of the 13 sacrificial deposits at Khvalynsk I (85%) contained the bones of domesticated sheep-goats, domesticated cattle, and/or horses, the same three taxa found in the graves. The two sacrificial deposits that did not contain these taxa (SD 9 & 13) contained a greenstone adze in a red ochre deposit in SD 13, and a bird (not identified) skeleton decorated with two shell beads and one copper bead lying on a red-ochre-stained bark plate in SD 9. Domesticated animals and horses were the exclusive mammalian sacrificial offerings in the sacrificial deposits as well as in the graves at both I and II.

The inclusion of horses in graves with humans and domesticated animals, and the equally interesting exclusion of obviously wild animals such as moose, suggests that at Khvalynsk the symbolic status of horses had started to move toward the domesticated pole on the wild-domesticated continuum by 4500 BC. Horses were treated like domesticated animals in three ways: they were buried with humans and domesticated animals in graves that excluded obviously wild animals; at S’yezzhe they were arranged in head-and-hoof deposits like the cattle and sheep-goats at Khvalynsk; and horse images were new symbolic artifacts. Decorative bone plaques shaped like horses were found at S’yezzhe and zoomorphic mace-heads that might represent horse heads were found at Khlopkov Bugor, 130 km south of Khvalynsk; and at Lebyazhinka IV, an Eneolithic settlement near Samara (Kriukova 2003). The evidence for a significant change in the human treatment of horses during the fifth millennium BC is symbolic rather than zoological, but it should not be ignored. In addition, recent studies of ancient horse DNA (Librado et al. 2021) indicate that the horses in the Don-Volga steppes in this era were the genetic ancestors of the modern domesticated horses that first appeared in fully modern form about 2200–2100 BCE in the Don-Volga region. The symbolic changes in the human treatment of horses seen at Khvalynsk, S’yezzhe, and other Volga sites signal the earliest phase in an experimental selection process between humans and horses in this region that produced a gradually improving partnership over the next two millennia, culminating in horses genetically and behaviorally suited for warfare, like modern horses. Perhaps the Khvalynsk horses could be trained to ride in quiet settings such as herding.

The proportion of individuals buried with domesticated mammal sacrifices was 14% at Khvalynsk I (23 of 158 individuals) and 14% at Khvalynsk II (6 of 43 individuals). Counting only adults preserved well enough to be assigned a sex, the percent receiving sacrifices was higher: at Khvalynsk I, seven females had an animal sacrifice, or 18% of adult females; and 12 males, 27% of adult males; four immature individuals also received animal sacrifices. At Khvalynsk II, animal bones occurred with two adult men (II:38 and the mace chief II:24, together 10% of adult males), three females (50% of females), and two immatures (Table 3, Figure 17).

The largest single sacrifice associated with a specific grave was the complex grave in Khvalynsk I:142–144, where two adult men aged 45–60 and 30–40 and an adult woman aged 40–50 were buried together on their backs with tightly raised knees (see Figure 15 for cemetery plan). With them were a first phalange of a horse and the skulls of eight cattle (Agapov et al 1990: Table 1). We can estimate edible meat weight as about 40% of adult body weight—for example, a 500 kg steer yields about 200 kg of ‘retail’ meat. Neolithic domesticated cattle in eastern Europe weighed between 350–500 kg (Kyselý 2016:44); let us use 400kg. If the cattle at Khvalynsk weighed 400 kg, eight cattle would produce 1280 kg of meat, and the horse another 120 kg (assuming a pony-sized body weight of 300 kg), equaling a total meat weight of 1400 kg. for the mammals in I:142–144. While no precise estimate is possible, this quantity of meat implies that the guests numbered in the hundreds. At Khvalynsk II, a similar large sacrifice was found in a sacrificial deposit above the graves in Quadrat I/8 (Bogatkina 2010: 400). This deposit contained heads and hoofs of at least two cattle and two sheep-goats, and the lower limbs of two horses. These animals again would have yielded around 1400 kg of meat, like the large sacrifice at Khvalynsk I, and again imply hundreds of guests. Large-scale feasts are implied by the large mortuary animal sacrifices at Khvalynsk.

Five hallmarks of competitive feasts conducted to create and maintain socio-political power, according to a recent analysis of feasting by Kassabaum (2019: 614–615), are large quantities of special foods shared between large groups at special places in the presence of special markers of elite status (maces and copper, here). In kin-based societies with competitive sections, feasts are an important arena for competition between lineages and clans (Hayden 2012: 126), while at the same time they channel that competition into non-violent rituals that often play an integrative, peace-making role (Dietler and Hayden 2001).

The feasts associated with funerals were sponsored or channeled through 14% of the population, and the animals sacrificed were not representative of the complex diet of fish, wild game (moose and deer), horses, and domesticated mammals that characterized everyday food consumption in Eneolithic settlement faunas in the middle Volga region (Morgunova 2014: Table 20; Schulting and Richards 2016; Vybornov 2019). Domesticated mammals, segmented and represented in funeral rituals by their parts, were used at Khvalynsk as a ritual currency to mark and symbolize social segments among the funeral guests and their families. Males, females, children, and even infants were among the designated minority to receive sacrifices. The status connected with mortuary mammal sacrifice seems to have resided in multi-generational families or in the role played by the sacrifice receiver in the funeral ritual rather than in the lifetime accomplishments of the deceased.

Domesticated animals, first adopted in the Volga-Ural steppes about 4800–4600 BCE, had triumphed by 4500 BC as the principal means of communication with the gods and ancestors, who apparently desired only sheep and goats, cattle, and an occasional horse. The horse was the only acceptable mammal that was indigenous. This new system of belief about the desires of the spirit world necessarily post-dated the arrival of domesticated animals, so it was a recently established ritual in 4500 BC. Yet this was the exclusive sacrificial ritual in the funerals at Khvalynsk. Khvalynsk was a central cemetery (because of its size) for a new funeral cult in which domesticated animals were the preferred channel of communication with the spirit world. If the Volga steppes were part of the Proto-Indo-European homeland, as many have argued (Anthony and Ringe 2015; Reich 2018; Narasimhan et al. 2019) then from the point of view of Indo-European religion, this was the moment when the world, made from the pieces of a cosmic cow (Mallory and Adams 2006: 435–436), began.

Four depositional groups: social segments at Khvalynsk

At least four depositional groups can be identified archaeologically at Khvalynsk. Three were defined by the presence of copper, animal sacrifices, and polished stone maces in graves; and the fourth, the majority, by their absence. The ca. 70% of graves that contained neither copper nor animal sacrifices nor maces did contain some notable bone, stone, and antler artifacts and many beads made of exotic imported shells.

About 14% of the population was buried wearing copper ornaments, and a different 14% with sacrificed domesticated animals. It is remarkable that these two minority groups were so similar in size and that they did not overlap more than expected, if the deposition of grave goods had occurred at random. An excessive overlap might be expected if people of higher social status had an elevated probability of receiving both types of grave goods, but with a few important exceptions noted below, the two groups were separate.

At Khvalynsk I, among 158 excavated individuals, 34 (17%) were buried with copper and/or mammal bones. In 32 of these 34 cases (94%), copper and sacrificed animal parts occurred separately, with different individuals (for supporting data see Table 3 and Figure 15). Copper ornaments occurred without animal bones with 13 individuals (8% of 158), and animal bones without copper with 20 different individuals (13%). Both exceptions at Khvalynsk I, two adult males with both copper and animal sacrifices (I:57 and I:108–110), also had polished stone maces, and in fact were the only individuals at Khvalynsk I with stone maces, suggesting that apart from the stone mace holders (see below), there was a disassociation between copper users and sacrifice receivers.

Khvalynsk II exhibited a similar separation between an animal-receiving minority and a copper-receiving minority, but with much more copper in the graves. Here out of 43 excavated individuals, 19 (44%, more than 2x the percentage at Khvalynsk I) had copper artifacts and/or animal sacrifices. Copper ornaments occurred without animal bones in the graves of 13 individuals, the same absolute number found at Khvalynsk I. These included nine males, two females, and two immatures. Animal sacrifices occurred without copper with three different individuals, one male, one female and one immature. In 16 of the 19 graves that had copper and/or animal sacrifices—84% of cases—they again occurred separately. The remaining three cases at Khvalynsk II where copper and animal sacrifices occurred in the same grave were divided between a richly equipped adult female (II:6), the isolated skull of an infant (II:14) buried with a string of copper beads and two horse phalanges, the only horse bones at Khvalynsk II; and an adult male with a stone mace (II: 24), the richest grave at Khvalynsk, discussed below.

At both Khvalynsk I and II, people buried with animal sacrifices did not in general have copper ornaments, and people who wore copper ornaments into the grave did not in general receive animal sacrifices. (Bird bone tubes are counted as an artifact, not a sacrifice.) The segregation between these groups is surprising. Under a model in which higher social status confers an elevated chance of receiving both offerings, they should have overlapped more. Instead, their segregation suggests that they represented distinct statuses. The copper ornaments were worked and welded locally, but the metal probably was obtained from Balkan cultures where smelting was practiced. Copper represented contacts with distant others. It symbolized foreign adventures and long-distance travels (which also can be seen in some cultures as journeys to ancestral worlds, see Helms 1992). The mammals for sacrifices were, in contrast, herded and produced nearer to Khvalynsk, so came from and symbolized a different set of locations and behaviors. Animal sacrifices were sacral (connected with funerals and spirits of dead ancestors) and local. A sacrifice was shared during integrative feasts attended by hundreds. Copper ornaments, in contrast, were deployed on the bodies of specific individuals, a minority, presumably with pride and its companion envy. A feast animal was partible and belonged at least temporarily to everyone, while a shining metal ornament decorated the individual who wore it.

It is tempting to interpret the sacrifice-receivers as members of a local sacral group such as shamans or priests (and their families) who were buried primarily at Khvalynsk I; and the metal-users (with their bird-bone whistles) as members of a male-biased, far-ranging group, such as traders or warriors, defined by their visits to different cultural worlds and/or access to metals obtained abroad, buried primarily at Khvalynsk II. Horseback riding perhaps already facilitated long-distance travel. Sacrifice-receivers were buried at Khvalynsk II, but it is interesting that none of them except the mace chief was related genetically to any other person at Khvalynsk II, while many of the copper-receiving males were related to other males in that cemetery. As a cemetery, Khvalynsk II was organized around related copper-receiving males, while the sacrifice-receivers were perhaps wives or sacrifices themselves (the infant in II:14). Polished stone maces identified a special class of leaders who united these two groups, and occurred in both cemeteries, implying that leadership was not limited to one cemetery or to one of the minority groups.

The mace-holders: Eneolithic chiefs