ABSTRACT

Coronary microvascular disease (CMVD) affects the coronary pre‐arterioles, arterioles, and capillaries and can lead to blood supply–demand mismatch and cardiac ischemia. CMVD can present clinically as ischemia or myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA or MINOCA, respectively). Currently, therapeutic options for CMVD are limited, and there are no targeted therapies. Genetic studies have emerged as an important tool to gain rapid insights into the molecular mechanisms of human diseases. For example, coronary artery disease (CAD) genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) have enrolled hundreds of thousands of patients and have identified > 320 loci, elucidating CAD pathogenic pathways and helping to identify therapeutic targets. Here, we review the current landscape of genetic studies of CMVD, consisting mostly of genotype‐first approaches. We then present the hypothesis that CAD GWAS have enrolled heterogenous populations and may be better characterized as ischemic heart disease (IHD) GWAS. We discuss how several of the genetic loci currently associated with CAD may be involved in the pathogenesis of CMVD. Genetic studies could help accelerate progress in understanding CMVD pathophysiology and identifying putative therapeutic targets. Larger phenotype‐first genomic studies into CMVD with adequate sex and ancestry representation are needed. Given the extensive CAD genetic and functional validation data, future research should leverage these loci as springboards for CMVD genomic research.

Keywords: coronary microvascular disease, genetics, genomics, ischemic heart disease

1. Introduction

Coronary microvascular disease (CMVD), defined as disease of the coronary pre‐arterioles, arterioles, and capillaries, impairs proper blood flow to the heart [1]. CMVD is characterized by functional and structural changes, including endothelial and smooth muscle cell dysfunction, luminal narrowing of arterioles and capillaries, vessel tortuosity, diminished capillary density, and capillary obstruction [2]. All of these can compromise coronary blood flow, lead to cardiac ischemia, and contribute to a range of clinical presentations [3, 4, 5]. CMVD can cause angina and myocardial infarction, as in ischemia (or myocardial infarction) with no obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA and MINOCA), and may represent up to 30%–50% of the burden of IHD [1, 3, 4, 6, 7]. CMVD also contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) [4, 8, 9]. In some patients, CMVD occurs concurrently with coronary artery disease (CAD), and increases mortality. CMVD is also associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events [3]. Currently, therapeutic options for CMVD are limited, and there are no targeted therapies.

CMVD impacts the treatment and diagnosis of cardiovascular ischemia in women and contributes to the discrepant burden of heart disease in women. A seminal trial in this field is the 2006 initial women's ischemia syndrome evaluation (WISE) study, which enrolled 256 women with suspected IHD undergoing coronary angiography. Notably, two thirds of the women in this study had INOCA [6]. Proposed mechanisms contributing to the higher burden of CMVD in women include sex differences in hormone effects, autonomic regulation, and susceptibility to proatherogenic mediators [4, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15]. Unlike with sex differences, there are currently minimal data regarding the effects of race, ethnicity, or genetic ancestry on CMVD.

Given the clinical importance of CMVD, a clearer understanding of the underlying pathophysiology is needed to identify new treatments and accelerate progress in the field.

Genetic studies have emerged as an important tool to gain rapid insights into the molecular mechanisms of human diseases. For example, CAD genome‐wide association studies (GWAS) have enrolled hundreds of thousands of patients and have identified > 320 CAD‐associated loci [16, 17], validating known pathogenic pathways for CAD in diverse patient populations, such as lipoprotein metabolism [18], and also identifying potential novel mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. For example, the gene Tribbles1 regulates lipid homeostasis, and variants mapped to this gene impact risk for myocardial infarction [19]. Genetic studies have the power to advance our understanding of disease and therapeutic options, and we should leverage these to improve our understanding of CMVD.

Several insightful reviews have addressed putative pathological mechanisms and biomarkers of CMVD [2, 3, 4]. In this review, we summarize the current landscape of genetic studies of CMVD, consisting mostly of genotype‐first approaches (Table 1). We next discuss the hypothesis that CAD GWAS are better characterized as IHD GWAS and may be used to gain novel insights into CMVD pathogenesis. We present genomic studies of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) as further support of this hypothesis.

TABLE 1.

Summary of genotype‐first studies.

| Authors | Population | Phenotype | Genes associated with Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford et al. | 109 patients with angina (mean age 61, 74% women) | Invasive measures showing abnormal coronary vasoreactivity in response to intravenous adenosine in patients without CAD | ET‐1 |

| Yoshino et al. |

643 patients who had invasive coronary microcirculatory assessment between 1993 and 2010 (median age 46–51, 93% white) |

Abnormal coronary flow reserve (< 2.5) in response to intracoronary injection of adenosine |

VEGFA CKDN2B‐AS1 MYH15 NT5E |

| Guerraty et al. | 11 017 patients with ischemic cardiac symptoms (mean age 70, 41% women, 73% white) | Ischemia with non‐obstructive CAD and MBF by perfusion PET | FOG2 |

| Severino et al. |

362 patients with suspected myocardial ischemia (mean age 64) |

CMVD defined as invasive coronary flow reserve < 2.5 and no CAD | eNOS |

| Resar et al. |

100 patients with 70% or greater stenosis in at least one epicardial artery (mean age 61–66) |

Impaired collateral formation as measured by the Rentrop scoring system | HIF‐1A |

| Zigra et al. |

107 patients with history of premature MI (mean age 32) |

History of premature MI with normal epicardial arteries | eNOS |

2. Candidate Gene Studies

2.1. Endothelin‐1 (ET‐1)

ET‐1 is a strong vasoconstrictor involved in the pathogenesis of CMVD [20]. Patients with slow coronary flow have been shown to have increased plasma levels of ET‐1 [21]. Ford et al. used a candidate gene approach to explore the association between rs9349379, a locus in the common intronic enhancer region of ET‐1, and CMVD [22]. 391 patients presenting with angina were recruited, and after invasive coronary angiography, 151 participants without obstructive CAD were enrolled and underwent invasive coronary vasoreactivity testing. Of these, 72% of them had evidence of CMVD (n = 109), and 46% of patients with CMVD harbored the minor G allele at rs9349379 compared with 39% of controls (p = 0.013). Participants with the rs9349379‐G allele had an odds ratio of 2.33 for CMVD (95% confidence interval 1.10–4.96; p = 0.027), impaired myocardial perfusion (p = 0.04) and exercise intolerance (−3.0 units in Duke Exercise Treadmill Score; p = 0.045) [20].

The G allele at rs9349379 locus is located in an intron and enhances ET‐1 expression, increasing plasma ET‐1 and activating the G‐coupled endothelin A receptor on vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) [20, 23]. Interestingly, rs9349379‐G is protective against migraines caused by meningeal and intracranial vasodilation, suggesting rs9349379‐G enhances vasoconstriction of vessels to compensate [23]. Since ET‐1 is a vasoconstrictor and its expression is enhanced by rs9349379‐G, the G‐allele could result in increased or inappropriate microvascular vasoconstriction and promote cardiac ischemia.

2.2. CDKN2B‐AS1, VEGFA, MYH15, and NT5E

Yoshino et al. used a candidate gene approach to link genetic variants of key vascular genes with microvascular dysfunction. Patient genetic data, encompassing 1536 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across 76 candidate genes, was collected. Individuals in the study had non‐obstructive CAD, defined as less than a 30% coronary stenosis (n = 643). Males (n = 217) and females (n = 426) underwent invasive microvascular function testing. Through the administration of intracoronary adenosine and usage of a Doppler guidewire, coronary flow reserve (CFR) values were obtained for the participants. CDKN2B‐AS1, MYH15, NT5E, and VEGFA were found to be significantly associated with CMVD [24].

2.3. Cyclin‐Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2B Antisense RNA 1 (CDKN2B‐AS1)

CDKN2B‐AS1 is a long noncoding RNA expressed in vascular endothelial cells, coronary smooth muscle cells, and cells in the colon [25]. It is part of the CDKN2B‐CDKN2A gene cluster which includes tumor suppressor genes. CDKN2B‐AS1 interacts with polycomb genetic repressive complexes, resulting in epigenetic silencing of genes in proximity.

Yoshino found that SNPs that map to the CDKN2B‐AS1 gene are associated with an abnormal CFR value of < 2.5, and the strongest SNP association (rs10757274) had an odds ratio of 1.5 (p = 0.003). Tumor suppressor genes play an important role in cell senescence and apoptosis, and failure of CDKN2B‐AS1 to epigenetically silence adjacent tumor suppressor genes may promote apoptosis and cell senescence in vascular endothelial cells, leading to malformed vessels, reduced microvascular density, and overall reduction in microvascular function [26].

2.4. Myosin Heavy Chain 15 (MYH15)

Variants associated with MYH15 have previously been correlated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction [27]. Two SNPs located in the introns of MYH15 SNPs were associated with CFR < 2.5 in men. The strongest SNP in males had an odds ratio of 2.60 (p = 0.0006), and in women, the odds ratio was 1.25 (p = 0.1454) [24]. MYH15 is predicted to be involved in actin, ATP, and calmodulin binding. MYH15 may also interact with other myosin forms to maintain tonic smooth muscle contraction [28]. Aberration in baseline tonic contractions of VSMC may be involved in the reduction of lumen diameter in microvessels [29].

2.5. Ecto‐5′‐Nucleotidase (NT5E)

NT5E encodes the enzyme CD73 which dephosphorylates adenosine monophosphate to adenosine. Adenosine is a cardioprotective molecule and endothelium‐dependent vasodilator [30]. An NT5E SNP in the 3' UTR region was found to be associated with abnormal CFR (< 2.5) in men (odds ratio = 2.85, p = 0.0018) but not in women (odds ratio = 1.11, p = 0.4794) [24]. NT5E knockout mice have reduced adenosine levels [31], and loss of function variants may have decreased levels of adenosine, impairing coronary vasodilation, and contributing to cardiac ischemia and CMVD.

2.6. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (VEGF‐A)

VEGF‐A is a well‐established master regulator of angiogenesis and blood vessel maintenance. The downstream effects of VEGF‐A include cardiac stem cell migration, cardiomyocyte survival, and angiogenesis [32]. Moreover, the usage of telatinib, an anti‐VEGF‐A drug, promotes coronary capillary rarefaction [33]. A SNP in the 3' UTR of VEGF‐A was linked to an abnormal CFR of < 2.5 (odds ratio = 1.68, p = 0.004) [24]. When Yoshino et al. stratified the results by sex, the VEGF‐A allele was found to be associated with CFR < 2.5 in men (odds ratio = 2.74, p = 0.0015) but not in women (odds ratio = 1.06, p = 0.6909) [24].

VEGF‐A loss of function SNPs can result in impaired endothelial cell proliferation and reduced microvasculature due to compromised angiogenic ability [26]. The resulting loss of capillary density may impair the heart's responses to pressure overload [34]. Importantly, anti‐VEGF drugs are currently used to treat certain cancers and degenerative eye conditions; however, the unintended consequences impacting microcirculation remain unstudied [35].

2.7. Friend of GATA 2 (FOG2)

Cardiomyocyte‐specific conditional deletion of FOG2 in adult mice resulted in a reduction in coronary microvasculature [36]. We previously performed a candidate gene study linking rs28374544, a missense variant which encodes FOG2 S657G, with CMVD [37]. Patients with the variant clinically presented with increased angina, abnormal coronary blood flow, and limited obstructive CAD (< 50% in left main coronary artery or < 70% in other major vessels) [37]. Further analysis of heart tissue and functional cardiomyocyte studies suggested that FOG2 S657G is associated with altered expression of angiogenic factors which may result in diminished microvascular formation. Furthermore, the variant was associated with differentially regulated cardiomyocyte metabolism which could drive supply–demand mismatch and lead to cardiac ischemia [37].

2.8. Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase (eNOS)

Endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) converts L‐arginine to nitric oxide (NO) in endothelial cells, and NO modulates vasodilation, athero‐protection, and smooth muscle cell proliferation [38]. To study the role of eNOS in patients with nonobstructive CAD, Zigra et al. recruited 107 participants with a history of premature MI and a control group of similar age and sex demographics (n = 103). All participants were first classified as having significant CAD (≥ 50% stenosis) or normal epicardial arteries and then genotyped for the eNOS T786C and G894T variants. Both variants were associated with premature myocardial infarction (before age 35 years) in patients without obstructive CAD (e.g., MINOCA), indicating a role for eNOS in CMVD [39].

To further examine how eNOS is connected to IHD, Severino et al. recruited 362 patients arranged into three groups. Group 1 consisted of patients with obstructive CAD, defined as ≥ 50% stenosis in at least one major epicardial artery (n = 218). Group 2 individuals had abnormal CFR of ≤ 2.5 with no obstructive CAD (n = 54). Group 3 was a control group without CAD or CMVD (n = 90). Patients were genotyped (GT, GG, or TT) at rs1799983. Participants in groups 1 and 2 were more likely to be heterozygous for the locus relative to group 3, suggesting that the GT genotype is associated with cardiac ischemia (OR: 2.36; CI 95% 1.08–5.2; p: 0.03). Although no significant difference in GT prevalence was found between groups 1 and 2, the presence of the TT genotype was higher in group 1 compared to group 2 (p < 0.001). Additionally, multivariate analysis found that the heterozygous variant was associated with acute coronary syndrome (OR: 2.82; CI 95% 1.42–5.59; p: 0.003) [38].

NO synthesized by eNOS decreases inflammation and promotes angiogenesis [40]. Loss of function eNOS variants may result in vascular inflammation which may lead to endothelial dysfunction, characteristic of CMVD pathogenesis [40].

2.9. Hypoxia‐Inducible Factor 1α (HIF‐1α)

VEGF‐A plays a critical role in coronary microvascular health, and upstream regulators of VEGF‐A, such as HIF‐1α, may also regulate the coronary microvasculature [41]. Another coronary phenotype associated with resilience of the coronary circulation is coronary collateral formation. Though this phenotype has been described on coronary angiography (and therefore in the context of larger vessels), it represents angiogenic processes whose pathways overlap with CMVD. Resar et al. used a candidate gene approach to implicate HIF‐1α in coronary collateral formation. 100 patients with a 70% or greater stenosis in at least one epicardial artery and with no acute myocardial infarction or history of revascularization were recruited [42]. Participants were genotyped for rs11549465, a variant which encodes a C to T substitution resulting in missense mutation HIF‐1α P582S. Patients without collateral formation had a significantly higher frequency of the missense mutation (0.188 vs. 0.037, p < 0.001), and heterozygous (CT) or homozygous (TT) genotype was negatively associated with collateral formation (OR = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.04 to 0.84; p = 0.03) [42].

HIF‐1α is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of numerous genes involved in angiogenesis, vascular remodeling, and vascular reactivity including ET‐1 and VEGF, which have both previously been linked to CMVD [42].

2.10. Limitations of Candidate Gene Studies

These studies have identified several putative genes associated with CMVD, and convergence onto common pathways and biological plausibility support their roles in disease pathogenesis. However, candidate gene studies have several important limitations. First, their genotype‐first nature their ability to uncover novel biology. Second, these studies had lower numbers of participants in general, given challenges in phenotyping CMVD. Most importantly, candidate gene studies often fail to replicate in independent cohorts. None of these studies had independent replication cohorts. There is a clear need for larger, diverse, unbiased genomic studies validated in distinct cohorts.

3. Reframing CAD GWAS as IHD GWAS

In contrast to CMVD, there have been many such large studies exploring the genetics of CAD. GWAS have identified > 320 genetic loci associated with CAD [16, 43], many of which are associated both with CAD and co‐morbid conditions such as hypercholesterolemia, obesity, and hypertension [44]. To adequately power these GWAS, investigators have used broad clinical criteria and included a heterogeneous group of people with wide range of clinical presentations. For example, some individuals present with transmural myocardial infarction with identifiable obstructive lesion on coronary angiography, whereas others were enrolled based on chest pain, elevated plasma troponins levels, and ECG changes. These latter patients may have undergone risk stratification with stress testing without additional testing, and therefore did not have confirmed obstructive CAD. It is likely that a portion of these patients had CMVD as the underlying etiology of their cardiac ischemia. Thus, we argue that these loci are best defined as “Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) loci” which may be due to CAD or CMVD (or both), or less common causes of IHD such as SCAD.

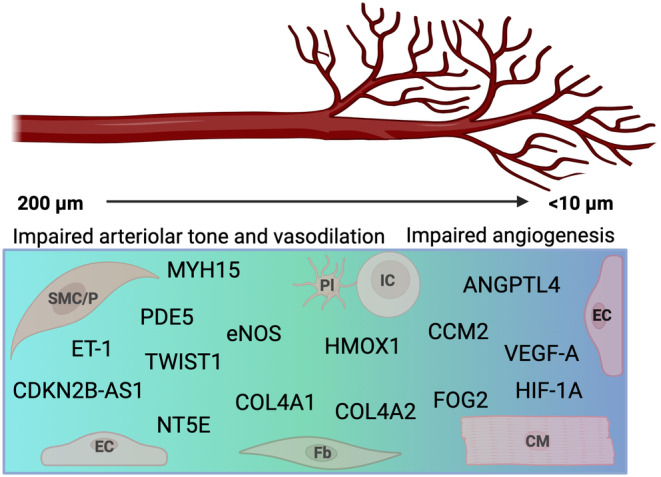

Indeed, there is significant overlap between previously identified “IHD loci” and genes involved in CMVD, including ET‐1, CDKN2B‐AS1, HMOX1, and VEGF‐A, all of which have been implicated in both CAD and CMVD. ET‐1 plasma levels and genetic variations in CDKN2B‐AS1 have been associated with both CAD and CMVD [25, 45, 46]. Here we review the genes associated with IHD loci which may play a role in CMVD. These act on various cell types including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, cardiomyocytes, and immune cells. Some genes act via a primary cell type whereas others have disparate roles in different processes. For example, MYH15 effects are primarily restricted to muscle cells while TWIST1 has reported roles in both endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Similarly, these genes can affect different pathophysiologic changes underlying CMVD, ranging from angiogenesis and vascular remodeling to vascular tone and reactivity [24, 47, 48]. Though we do not specifically outline fibroblast or platelet‐related genes, these undoubtedly contribute to the complex pathophysiology of CMVD involving multiple mechanisms, multiple cell types, and multiple vascular levels (Figure 1). Finally, though there are some similarities between CAD and CMVD—both processes involve smooth muscle dysfunction and have similar risk factors including age, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia—there are notable differences in the pathophysiology of each disease. First, these processes occur in different compartments of the coronary circulation and have distinct structures and flow environments. Second, they have distinct developmental origins and involve distinct cell biologic processes (e.g., lipid accumulation is not seen in CMVD as in CAD). Lastly, altered coronary flow is not present in all cases of CAD, but is a staple of CMVD [49].

FIGURE 1.

Putative and known CMVD genes. Genes associated with CMVD affect different parts of the coronary microcirculation including the pre‐arterioles (100–200 μm), arterioles (50–100 μm), and capillaries (< 10 μm). They regulate processes including arteriolar tone, vasodilatory function, and angiogenesis, and many affect multiple processes in both arterioles and capillaries. Genes may regulate a unique cell type or serve different functions in distinct cell types. Understanding the genetic architecture of CMVD brings together different disciplines and draws from distinct fields. CM, cardiomyocyte; EC, endothelial cell; Fb, fibroblast; IC, immune cell; Pl, platelet; SMC/P, smooth muscle cell/pericyte.

3.1. Angiopoietin‐Like 4 (ANGPTL4)

Loss‐of‐function mutations in ANGPTL4 are associated with CAD [46]. More recently, ANGPTL4 has been shown to regulate the microvasculature through endothelial cell metabolism and angiogenesis [50]. ANGPLT4 also decreased inflammation following myocardial infarction and was protective in this context [51].

3.2. Heme Oxygenase 1 (HMOX1)

Increased HMOX1 expression has been reported in white blood cells of patients with CAD [52, 53]. HMOX1 has also been shown to promote angiogenesis and positively regulate VEGF [54, 55, 56]. More generally, HMOX1 breaks down heme, and can affect antioxidant defense, cell senescence, and cell growth [57]. The role of HMOX1 in different cell types could promote CAD or CMVD through distinct pathways.

3.3. Phosphodiesterase Type 5 (PDE5)

Family‐based studies and larger GWAS have associated PDE5A with CAD [44, 46, 58]. PDE5A modulates cGMP levels by hydrolyzing cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), a potent regulator of vascular smooth muscle proliferation, remodeling, and contractility [59]. PDE5A inhibitors are currently used to treat erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension [60].

3.4. TWIST‐Related Protein 1 (TWIST1)

rs2107595 was reported to modulate histone deacetylase 9 (HDAC9) and has previously been associated with CAD in both GWAS and smaller case–control studies [61]. However, this locus may also be involved in CAD pathogenesis through TWIST1 modulation [47], and specifically regulate the expression of TWIST1 in VSMC to promote plasticity and phenotype switching [62]. TWIST1 also regulates endothelial cell proliferation and inflammation, and aberrant regulation may increase risk of atherosclerosis [48].

3.5. Cerebral Cavernous Malformations Protein 2 (CCM2)

rs2107732 in the CCM2 gene has been identified as protective against CAD via GWAS [46], and loss of function mutations in CCM2 are associated with increased risk of CAD. Loss of CCM2 disrupts endothelial cell function via increased Rho A‐Rho kinase activity, and loss of CCM2 leads to aberrant angiogenic remodeling. Notably, CCMs also regulate VEGF‐A expression [63].

3.6. Collagen Type 4 Alpha 1 Chain and Alpha 2 Chain (COL4A1/COL4A2)

COL4A1 and COL4A2 have been implicated in CAD, and variants in COL4A1 and COL4A2 were also found to co‐segregate with SCAD in family studies [64]. Further analysis revealed that they are opposite risk alleles for SCAD and CAD [65]. Decreased COL4A1/COL4A2 expression is associated with CAD, and increased expression was associated with a higher risk of SCAD [65]. Since COL4A1/COL4A2 maintain arterial integrity and VSMC function, variants may alter the migration of VSMCs to the intima leading to the progression of atherosclerosis [65]. COL4A1 and COL4A2 also affect smooth muscle cell function and may contribute to CMVD via impaired vasoreactivity and arteriolar tone. Finally, type IV collagens are potent inhibitors of angiogenesis [66].

3.7. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Disease (SCAD) Genes

SCAD impacts the larger epicardial coronary vessels and is a cause of myocardial infarction that primarily impacts women. Currently, the pathogenesis of SCAD is not fully understood and the field is still working to understand the genetic overlap between SCAD and other causes of IHD. Meanwhile, investigators are using genetic studies to gain insight into mechanisms of SCAD. Carss et al. sequenced 384 individuals with SCAD and found that only a small percentage of SCAD survivors had a pathogenic variant that could explain their disease development [67]. Adlam et al. used GWAS meta‐analysis to identify 16 risk loci for SCAD. Through this study, they identified a locus containing tissue factor gene F3, which regulates blood coagulation, to be specific for SCAD risk. They also identified six loci which mapped to PHACTR1, HTRA1, ATP2B1, COL4A1, COL4A2, and MRPS6 with suspected causal variants shared by SCAD and CAD but with opposite risk alleles [65]. This results indicate that there are likely shared biological pathways contributing to these different cardiovascular diseases but via different mechanisms. As with CMVD, continuing genetic studies will help the field elucidate and differentiate the pathways contributing to CMVD, CAD, and SCAD (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) heterogeneity. Clinical manifestations of cardiac ischemia can stem from multiple causes including those that affect the coronary microvasculature, as in coronary microvascular disease (CMVD), or the epicardial vessels, as in coronary artery disease (CAD), coronary spasms, thrombosis or spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). CAD GWAS have enrolled heterogeneous populations which are more accurately described as having IHD. The underlying pathophysiology driving the results may range from CMVD to larger vessel atherosclerosis or SCAD. A growing number of genetic studies has shown the large overlap in loci and putative genes that underlie IHD.

4. CMVD Co‐Morbidities

CMVD is associated with several cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and chronic kidney disease [68]. Understanding the genetic underpinnings of these co‐morbid diseases can help us better understand CMVD. For example, a study by Dou et al. found that aging and obesity were associated with decreased expression of caveolin‐1, which acts to inhibit the ADAM17 protein. When caveolin is decreased, ADAM17 activity is increased, leading to a variety of molecular changes ending in an increased proinflammatory state. This ultimately impairs bradykinin‐induced endothelium‐dependent vasodilatation of the coronary arterioles, which is part of the functional changes in CMVD [69]. As demonstrated in this example, inflammation plays a large role in the pathogenesis of CMVD and its associated conditions (diabetes, hypertension, etc.), which implicates a large number of inflammatory proteins including chemokines and interleukins [70]. Thus, it will also be important to focus on inflammatory pathways when exploring the genetics of CMVD pathogenesis [70].

5. CMVD Sex‐Based Differences

CMVD is particularly important in women's cardiovascular health [71]. Though the prevalence of CMVD diagnosed by objective imaging measures is similar in men and in women [71], CMVD remains under‐diagnosed and under‐treated in women and contributes to the discrepant burden of untreated heart disease in women [1, 3, 7]. Interestingly, sex‐specific allelic variants within MYH15, VEGF‐A, and NT5E were associated with CMVD in men, but not in women. There are also sex‐based differences in susceptibility to ET‐1, an established mediator of CMVD pathogenesis [20]. Some of the sex‐based differences seen in these genetic studies may be due to sex‐specific effects related to gene–environment interactions. For example, gene expression patterns vary between men and women due to hormone regulation and sex‐based epigenetic modifications, which could explain how the same genetic variant would differentially influence CMVD risk in women versus men [72, 73]. IHD may be more heterogeneous or polygenic in women compared to men. Clinical studies have also shown sex‐based differences in plaque formation and coronary vascular remodeling [74]. Taken together, there remains a gap in understanding when it comes to the genetic susceptibility for CMVD in women, and sex is an important variable to consider in future studies.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this paper, we review the genetic loci associated with CMVD (Table 1). We discuss the data supporting the association between CVMD and the various genetic loci and explore how these loci may mechanistically relate to CMVD (Figure 1). Genomic studies give insight into molecular pathways and pathogenesis of disease and have contributed to our understanding of CAD. For example, genetic studies identified that patients with inactivating mutations in PCSK9 had decreased LDL cholesterol levels and lowered risk of CAD. This understanding led to the development of PCSK9 inhibiting monoclonal antibodies now used to treat hypercholesterolemia and reduce the risk of CAD [43]. We also review the genetic overlap between CMVD, CAD, and SCAD (Figure 2). Given the extensive CAD genetics data that exists and overlaps with CMVD, future studies should consider using already identified CAD genetic loci as starting points for CMVD genomic research. We also need more studies that explore sex‐based differences in CMVD genetics and pathogenesis.

Epigenetic regulators of CMVD are not well established. There are proposed roles for DNA methylation, histone modifications, and microRNAs as epigenetic modulators of CAD [75], and reviewing this field with a lens towards CMVD may also give novel insights.

Lastly, larger and more diverse genomic studies into the genomics of CMVD will help better elucidate the disease process and ideally lead to strides in diagnosis and management. Studies have demonstrated ancestry‐based differences in the genetics of CAD, and many of the CAD‐associated loci identified in populations of European ancestry have not been shown to have significant effect sizes in populations of African ancestry [31]. These ancestry‐based differences likely also apply to CMVD. Thus, it is critical that future studies include diverse patient populations and take ancestry and sex into account so that our evolving model of CMVD and therapeutic options do not exclude women and people of non‐European ancestry.

7. Perspectives

Coronary microvascular disease (CMVD) is emerging as an important and poorly understood cardiovascular disease which disproportionately affects women. Genomics is one approach to quickly gain new insight into mechanisms of disease. Here we review what is currently known about the genomics of CMVD and present a novel framework for thinking about and interpreting ischemic heart disease genomic studies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Alpha Phi Foundation (MAG, SSV), Burroughs Wellcome Fund (MAG), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant# K12GM081259 (TC). Figures created using BioRender.com.

Funding: This work was supported by the Alpha Phi Foundation (MAG, SSV), Burroughs Wellcome Fund (MAG), and National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant #K12GM081259 (TC).

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request from corresponding author.

References

- 1. Bairey Merz C. N., Pepine C. J., Walsh M. N., and Fleg J. L., “Ischemia and no Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (INOCA): Developing Evidence‐Based Therapies and Research Agenda for the Next Decade,” Circulation 135 (2017): 1075–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Camici P. G. and Crea F., “Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction,” New England Journal of Medicine 356 (2007): 830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taqueti V. R. and Di Carli M. F., “Coronary Microvascular Disease Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Options: JACC State‐Of‐The‐Art Review,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 72 (2018): 2625–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Godo S., Suda A., Takahashi J., Yasuda S., and Shimokawa H., “Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction,” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 41 (2021): 1625–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Del Buono M. G., Montone R. A., Camilli M., et al., “Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Across the Spectrum of Cardiovascular Diseases: JACC State‐Of‐The‐Art Review,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 78 (2021): 1352–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shaw L. J., Merz C. N. B., Pepine C. J., et al., “Insights From the NHLBI‐Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study Part I: Gender Differences in Traditional and Novel Risk Factors, Symptom Evaluation, and Gender‐Optimized Diagnostic Strategies,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 47 (2006): 4S–20S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Camm A. J., Lüscher T. F., Maurer G., and Serruys P. W., ESC CardioMed (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hage C., Svedlund S., Saraste A., et al., “Association of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction With Heart Failure Hospitalizations and Mortality in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: A Follow‐Up in the PROMIS‐HFpEF Study,” Journal of Cardiac Failure 26 (2020): 1016–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paulus W. J. and Tschope C., “A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: Comorbidities Drive Myocardial Dysfunction and Remodeling Through Coronary Microvascular Endothelial Inflammation,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62 (2013): 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burke A. P., Farb A., Malcom G., and Virmani R., “Effect of Menopause on Plaque Morphologic Characteristics in Coronary Atherosclerosis,” American Heart Journal 141 (2001): 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu M. Y., Hattori Y., Sato A., Ichikawa R., Zhang X. H., and Sakuma I., “Ovariectomy Attenuates Hyperpolarization and Relaxation Mediated by Endothelium‐Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor in Female Rat Mesenteric Artery: A Concomitant Decrease in Connexin‐43 Expression,” Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology 40 (2002): 938–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morton J. S., Jackson V. M., Daly C. J., and McGrath J. C., “Endothelium Dependent Relaxation in Rabbit Genital Resistance Arteries is Predominantly Mediated by Endothelial‐Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor in Females and Nitric Oxide in Males,” Journal of Urology 177 (2007): 786–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chan M. V., Bubb K. J., Noyce A., et al., “Distinct Endothelial Pathways Underlie Sexual Dimorphism in Vascular Auto‐Regulation,” British Journal of Pharmacology 167 (2012): 805–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wong P. S., Roberts R. E., and Randall M. D., “Sex Differences in Endothelial Function in Porcine Coronary Arteries: A Role for H2O2 and Gap Junctions?,” British Journal of Pharmacology 171 (2014): 2751–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yap F. C., Taylor M. S., and Lin M. T., “Ovariectomy‐Induced Reductions in Endothelial SK3 Channel Activity and Endothelium‐Dependent Vasorelaxation in Murine Mesenteric Arteries,” PLoS One 9 (2014): e104686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aragam K. G., Jiang T., Goel A., et al., “Discovery and Systematic Characterization of Risk Variants and Genes for Coronary Artery Disease in Over a Million Participants,” Nature Genetics 54 (2022): 1803–1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tcheandjieu C., Zhu X., Hilliard A. T., et al., “Large‐Scale Genome‐Wide Association Study of Coronary Artery Disease in Genetically Diverse Populations,” Nature Medicine 28 (2022): 1679–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cadby G., Giles C., Melton P. E., et al., “Comprehensive Genetic Analysis of the Human Lipidome Identifies Loci Associated With Lipid Homeostasis With Links to Coronary Artery Disease,” Nature Communications 13 (2022): 3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burkhardt R., Toh S. A., Lagor W. R., et al., “Trib1 is a Lipid‐ and Myocardial Infarction‐Associated Gene That Regulates Hepatic Lipogenesis and VLDL Production in Mice,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 120 (2010): 4410–4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ford T. J., Corcoran D., Padmanabhan S., et al., “Genetic Dysregulation of Endothelin‐1 is Implicated in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction,” European Heart Journal 41 (2020): 3239–3252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pekdemir H., Polat G., Cin V. G., et al., “Elevated Plasma Endothelin‐1 Levels in Coronary Sinus During Rapid Right Atrial Pacing in Patients With Slow Coronary Flow,” International Journal of Cardiology 97 (2004): 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Motz W., Vogt M., Rabenau O., Scheler S., Lückhoff A., and Strauer B. E., “Evidence of Endothelial Dysfunction in Coronary Resistance Vessels in Patients With Angina Pectoris and Normal Coronary Angiograms,” American Journal of Cardiology 68 (1991): 996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gupta R. M., Hadaya J., Trehan A., et al., “A Genetic Variant Associated With Five Vascular Diseases is a Distal Regulator of Endothelin‐1 Gene Expression,” Cell 170 (2017): 522–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yoshino S., Cilluffo R., Best P. J., et al., “Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Associated With Abnormal Coronary Microvascular Function,” Coronary Artery Disease 25 (2014): 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y. Y., Wang H., and Zhang Y. Y., “CDKN2B‐AS1 Gene rs4977574 A/G Polymorphism and Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta‐Analysis of 40,979 Subjects,” Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 25 (2021): 8877–8889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leopold J. A., “Microvascular Dysfunction: Genetic Polymorphisms Suggest Sex‐Specific Differences in Disease Phenotype,” Coronary Artery Disease 25 (2014): 275–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Luke M. M., Lalouschek W., Rowland C. M., et al., “Polymorphisms Associated With Both Noncardioembolic Stroke and Coronary Heart Disease: Vienna Stroke Registry,” Cerebrovascular Diseases 28 (2009): 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fisher S. A., “Vascular Smooth Muscle Phenotypic Diversity and Function,” Physiological Genomics 42A (2010): 169–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brozovich F. V., Nicholson C. J., Degen C. V., Gao Y. Z., Aggarwal M., and Morgan K. G., “Mechanisms of Vascular Smooth Muscle Contraction and the Basis for Pharmacologic Treatment of Smooth Muscle Disorders,” Pharmacological Reviews 68 (2016): 476–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Costa F. and Biaggioni I., “Role of Nitric Oxide in Adenosine‐Induced Vasodilation in Humans,” Hypertension 31 (1998): 1061–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Street S. E., Kramer N. J., Walsh P. L., et al., “Tissue‐Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase Acts Redundantly With PAP and NT5E to Generate Adenosine in the Dorsal Spinal Cord,” Journal of Neuroscience 33 (2013): 11314–11322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Giordano F. J., Gerber H.‐P., Williams S.‐P., et al., “A Cardiac Myocyte Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Paracrine Pathway Is Required to Maintain Cardiac Function,” Biological Sciences 98 (2001): 5780–5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Steeghs N., Gelderblom H., Roodt J. O., et al., “Hypertension and Rarefaction During Treatment With Telatinib, a Small Molecule Angiogenesis Inhibitor,” Clinical Cancer Research 14 (2008): 3470–3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Izumiya Y., Shiojima I., Sato K., Sawyer D. B., Colucci W. S., and Walsh K., “Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Blockade Promotes the Transition From Compensatory Cardiac Hypertrophy to Failure in Response to Pressure Overload,” Hypertension 47 (2006): 887–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mawalla B., Yuan X., Luo X., and Chalya P. L., “Treatment Outcome of Anti‐Angiogenesis Through VEGF‐Pathway in the Management of Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review of Phase II and III Clinical Trials,” BMC Research Notes 11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhou B., Ma Q., Kong S. W., et al., “Fog2 is Critical for Cardiac Function and Maintenance of Coronary Vasculature in the Adult Mouse Heart,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 119 (2009): 1462–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guerraty M. A., Verma S., Ko Y. A., et al., “FOG2 Coding Variant Ser657Gly is Associated With Coronary Microvascular Disease Through Altered Hypoxia‐Mediated Gene Transcription,” medRxiv (2023).

- 38. Severino P., D'Amato A., Prosperi S., et al., “Potential Role of eNOS Genetic Variants in Ischemic Heart Disease Susceptibility and Clinical Presentation,” Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 8 (2021): 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zigra A. M., Rallidis L. S., Anastasiou G., Merkouri E., and Gialeraki A., “eNOS Gene Variants and the Risk of Premature Myocardial Infarction,” Disease Markers 34 (2013): 431–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sarmah N., Nauli A. M., Ally A., and Nauli S. M., “Interactions Among Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase, Cardiovascular System, and Nociception During Physiological and Pathophysiological States,” Molecules 27 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Semenza G. L., “Hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 and cardiovascular disease,” Annual Review of Physiology 76 (2014): 39–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukumura D., Gohongi T., Kadambi A., et al., “Predominant Role of Endotheilal Nictric Oxide Synthase in Vascular Endothelial Growth‐Factor‐Induced Angiogenesis and Vascular Permeability,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (2001): 2604–2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Khera A. V. and Kathiresan S., “Genetics of Coronary Artery Disease: Discovery, Biology and Clinical Translation,” Nature Reviews. Genetics 18 (2017): 331–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McPherson R. and Tybjaerg‐Hansen A., “Genetics of Coronary Artery Disease,” Circulation Research 118 (2016): 564–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Mayyas F., Al‐Jarrah M., Ibrahim K., Mfady D., and Van Wagoner D. R., “The Significance of Circulating Endothelin‐1 as a Predictor of Coronary Artery Disease Status and Clinical Outcomes Following Coronary Artery Catheterization,” Cardiovascular Pathology 24 (2015): 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Erdmann J., Kessler T., Munoz Venegas L., and Schunkert H., “A Decade of Genome‐Wide Association Studies for Coronary Artery Disease: The Challenges Ahead,” Cardiovascular Research 114 (2018): 1241–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma L., Bryce N. S., Turner A. W., et al., “The HDAC9‐Associated Risk Locus Promotes Coronary Artery Disease by Governing TWIST1,” PLoS Genetics 18 (2022): e1010261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mahmoud M. M., Kim H. R., Xing R., et al., “TWIST1 Integrates Endothelial Responses to Flow in Vascular Dysfunction and Atherosclerosis,” Circulation Research 119 (2016): 450–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Guerraty M. and Arany Z., “A Call for a Unified View of Coronary Microvascular Disease,” Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 34 (2023): 145–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chaube B., Citrin K. M., Sahraei M., et al., “Suppression of Angiopoietin‐Like 4 Reprograms Endothelial Cell Metabolism and Inhibits Angiogenesis,” Nature Communications 14 (2023): 8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cho D. I., Kang H. J., Jeon J. H., et al., “Antiinflammatory Activity of ANGPTL4 Facilitates Macrophage Polarization to Induce Cardiac Repair,” JCI Insight 4 (2019): e125437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen S. M., Li Y. G., and Wang D. M., “Study on Changes of Heme Oxygenase‐1 Expression in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease,” Clinical Cardiology 28 (2005): 197–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Morita T., “Heme Oxygenase and Atherosclerosis,” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 25 (2005): 1786–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Deramaudt B. M. J. M., Braunstein S., Remy P., and Abraham N. G., “Gene Transfer of Human Heme Oxygenase Into Coronary Endothelial Cells Potentially Promotes Angiogenesis,” Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 68 (1998): 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cisowski J., Loboda A., Jozkowicz A., Chen S., Agarwal A., and Dulak J., “Role of Heme Oxygenase‐1 in Hydrogen Peroxide‐Induced VEGF Synthesis: Effect of HO‐1 Knockout,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 326 (2005): 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dulak J., Jozkowic A., Foresti R., et al., “Heme Oxygenase Activity Modulates Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Synthesis in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells,” Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 4 (2002): 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ayer A., Zarjou A., Agarwal A., and Stocker R., “Heme Oxygenases in Cardiovascular Health and Disease,” Physiological Reviews 96 (2016): 1449–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Verweij N., Eppinga R. N., Hagemeijer Y., and van der Harst P., “Identification of 15 Novel Risk Loci for Coronary Artery Disease and Genetic Risk of Recurrent Events, Atrial Fibrillation and Heart Failure,” Scientific Reports 7 (2017): 2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rybalkin S. D., Yan C., Bornfeldt K. E., and Beavo J. A., “Cyclic GMP Phosphodiesterases and Regulation of Smooth Muscle Function,” Circulation Research 93 (2003): 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kass D. A., Champion H. C., and Beavo J. A., “Phosphodiesterase Type 5: Expanding Roles in Cardiovascular Regulation,” Circulation Research 101 (2007): 1084–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang X. B., Han Y. D., Sabina S., et al., “HDAC9 Variant Rs2107595 Modifies Susceptibility to Coronary Artery Disease and the Severity of Coronary Atherosclerosis in a Chinese Han Population,” PLoS One 11 (2016): e0160449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nurnberg S. T., Guerraty M. A., Wirka R. C., et al., “Genomic Profiling of Human Vascular Cells Identifies TWIST1 as a Causal Gene for Common Vascular Diseases,” PLoS Genetics 16 (2020): e1008538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hughes M. F., Lenighan Y. M., Godson C., and Roche H. M., “Exploring Coronary Artery Disease GWAs Targets With Functional Links to Immunometabolism,” Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 5 (2018): 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Turley T. N., Theis J. L., Evans J. M., et al., “Identification of Rare Genetic Variants in Familial Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection and Evidence for Shared Biological Pathways,” Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 10 (2023): 393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Adlam D., Berrandou T. E., Georges A., et al., “Genome‐Wide Association Meta‐Analysis of Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection Identifies Risk Variants and Genes Related to Artery Integrity and Tissue‐Mediated Coagulation,” Nature Genetics 55 (2023): 964–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mundel T. M. and Kalluri R., “Type IV Collagen‐Derived Angiogenesis Inhibitors,” Microvascular Research 74 (2007): 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Carss K. J., Baranowska A. A., Armisen J., et al., “Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection: Insights on Rare Genetic Variation From Genome Sequencing,” Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine 13 (2020): e003030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Guerraty M. A., Rao H. S., Anjan V. Y., et al., “The Role of Resting Myocardial Blood Flow and Myocardial Blood Flow Reserve as a Predictor of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes,” PLoS One 15 (2020): e0228931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Dou H., Feher A., Davila A. C., et al., “Role of Adipose Tissue Endothelial ADAM17 in Age‐Related Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction,” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 37 (2017): 1180–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sagris M., Theofilis P., Antonopoulos A. S., et al., “Inflammation in Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction,” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22 (2021): 13471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Murthy V. L., Naya M., Taqueti V. R., et al., “Effects of Sex on Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction and Cardiac Outcomes,” Circulation 129 (2014): 2518–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Winham S. J., de Andrade M., and Miller V. M., “Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease: Importance of Sex and Ethnicity,” Atherosclerosis 241 (2015): 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Thej C., Roy R., Cheng Z., et al., “Epigenetic Mechanisms Regulate Sex Differences in Cardiac Reparative Functions of Bone Marrow Progenitor Cells,” npj Regenerative Medicine 9 (2024): 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Khuddus M. A., Pepine C. J., Handberg E. M., et al., “An Intravascular Ultrasound Analysis in Women Experiencing Chest Pain in the Absence of Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: A Substudy From the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute‐Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE),” Journal of Interventional Cardiology 23 (2010): 511–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Udali S., Guarini P., Moruzzi S., Choi S. W., and Friso S., “Cardiovascular Epigenetics: From DNA Methylation to microRNAs,” Molecular Aspects of Medicine 34 (2013): 883–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon reasonable request from corresponding author.