Abstract

This study investigates the enhancement of solar cell efficiency using nanofluid cooling systems, focusing on citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Traditional silicon-based and perovskite solar cells were examined to assess the impact of these nanofluids on efficiency improvement and thermal management. A Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed to vary nanoparticle concentration (0.2–0.8 wt%), coolant flow rate (0.5–1.5 L/min), and solar irradiance (800–1000 W/m²). Efficiency improvements were measured using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression. The experimental setup integrated nanofluid cooling systems with the solar cells, facilitating efficient heat dissipation. Results showed significant efficiency gains: silicon-based cells improved from 15 to 17% with PVP stabilization, and perovskite cells increased from 18 to 21.1%. PVP-stabilized nanofluids exhibited superior thermal conductivity (0.7 W/m K) and lower thermal resistance (0.008 K/W) compared to citrate-stabilized nanofluids, leading to notable reductions in operating temperatures. For silicon cells, temperatures dropped from 50 °C to 40 °C with PVP, and for perovskite cells, from 55 °C to 40 °C. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) identified optimal conditions for maximum efficiency improvement at 0.8 wt% nanoparticle concentration and 1.5 L/min flow rate. These findings underscore the potential of PVP-stabilized nanofluids in enhancing solar cell performance and longevity. Future research should refine the experimental design, increase sample size, and explore other nanoparticle types and stabilization methods to optimize solar cell efficiency and thermal management. This study contributes to the broader goal of promoting the widespread adoption of solar energy as a sustainable alternative to conventional energy sources.

Keywords: Solar cells, Nanofluids, Silver nanoparticles, Thermal management, Energy efficiency

Subject terms: Energy science and technology, Nanoscience and technology

Introduction

The escalating demand for renewable energy sources has been a significant global trend over the past few decades, primarily driven by the urgent need to address environmental sustainability and the finite nature of fossil fuel reserves. As the world grapples with the consequences of climate change, there has been a growing consensus on the necessity of transitioning to cleaner, more sustainable energy alternatives. Among the various renewable energy sources, solar energy is one of the most promising and rapidly expanding solutions1. Solar cells, commonly called photovoltaic (PV) cells, play a pivotal role in this transition by converting sunlight directly into electricity, providing a renewable power source with minimal environmental impact.

Despite the clear benefits and widespread adoption of solar energy, the efficiency of solar cells continues to be a critical challenge that must be addressed to maximize their energy output and overall viability2. Traditional silicon-based solar cells have long dominated the photovoltaic market, owing to their relatively high efficiency and the well-established manufacturing processes that support their production. However, these cells are not without their limitations. Silicon-based cells typically exhibit moderate efficiency levels and are prone to significant energy losses due to thermal effects. As the cells absorb sunlight, some energy is converted into heat, leading to elevated operating temperatures3. These increased temperatures, in turn, reduce the efficiency of the cells and contribute to their degradation over time, ultimately shortening their operational lifespan.

In response to the limitations of silicon-based cells, perovskite solar cells have emerged as a newer and highly promising alternative. Perovskite cells are known for their higher efficiency potential and the flexibility of their tunable bandgap properties, which allow for better optimization in different solar energy applications4. However, like their silicon counterparts, perovskite solar cells also face challenges related to thermal management and long-term stability. Effectively managing heat within these cells is crucial for unlocking their full potential and ensuring their durability in real-world applications.

Over the past decade, the application of nanotechnology in solar energy systems has garnered considerable attention to enhance solar cells’ performance and efficiency. One of the most promising advancements in this area is the development of nanofluids—engineered colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles within a base fluid. These nanofluids have been identified as a potential solution for improving the thermal management of solar cells. Incorporating nanofluids into cooling systems can significantly enhance heat dissipation, reduce operating temperatures, and improve solar cells’ overall efficiency and longevity5.

The application of nanofluids in solar energy systems has shown significant potential in improving thermal management and overall efficiency. Studies have demonstrated that nanofluids, such as Al2O3, TiO2, and hybrids, can enhance heat transfer, lower operating temperatures, and mitigate thermal degradation in photovoltaic (PV) systems (Table 1). For example, Al2O3 nanofluids have been shown to improve solar panel cooling, leading to higher energy output. Similarly, hybrid nanofluids have proven effective in applications like solar trough collectors, enhancing thermal efficiency and reducing entropy, particularly in high-irradiance regions. Despite these benefits, challenges remain. Issues such as increased pressure drop, system complexity, and the need for precise optimization have been reported. Additionally, nanofluids’ long-term stability and environmental impact need further research to ensure their broader adoption in solar energy systems.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis of nanofluid applications in solar energy systems.

| Objective | Findings | Positive Aspects | Negative Aspects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investigate the effects of nanofluids and heat sources on thermal absorption | Tungsten lamp showed highest efficiency; Al2O3 nanofluid was most effective | It is highly efficient with a tungsten lamp and is an effective Al2O3 nanofluid | Efficiency dropped over time; SDS reduced heat transfer6 |

| Optimize shell-and-tube heat exchanger using nanofluids | Cold-water flow rates improve efficiency; corrugated tubes best | Sustainable design; cold-water flow improved efficiency | Longer shell reduced efficiency; needs optimization7 |

| Analyze irreversibility in solar collectors with hybrid nanofluids | Heat transfer rate improved with nanoparticle variation | Enhanced heat transfer with nanoparticle optimization | Complex neural network analysis is needed8 |

| Conduct energy, exergy, and economic analysis using novel nanofluids | GAMWCNT nanofluid enhanced thermal and exergy efficiency | Improved thermal exergy efficiency with eco-friendly nanofluid | Efficiency declines with temperature; friction factor up9 |

| Evaluate energy exergy efficiency with zinc oxide nanofluids | Higher nanofluid concentration improves system efficiency | Higher efficiency with zinc oxide nanofluid | Surfactant affects thermophysical properties negatively10 |

| Analyze thermal performance with zigzag pipe and hybrid nanofluids | Zigzag pipe and hybrid nanofluid improved efficiency | Enhanced efficiency with zigzag pipe design | Increased pressure drop, limited scalability11 |

| Investigate convective heat transfer using TiN nanofluids | TiN nanofluid increased heat transfer; twisted tape was added | Increased heat transfer with TiN nanofluid, twisted tape | Pressure drop increased with higher concentration12 |

| Evaluate the performance of solar heaters with nanofluids in North Africa | TiO2 nanofluid reduced energy needs and emissions | Reduced energy, CO2 with TiO2 nanofluid | Higher fractions increase complexity, cost13 |

| Assess integrated solar desalination with nanofluid collectors | CNT nanofluids boosted water yield and efficiency | Enhanced yield, efficiency with CNT nanofluids | Complex preparation precise characterization needed14 |

| Study cooling effects of Al2O3 nanofluids on solar panels | Al2O3 cooling improved panel efficiency and reduced temperature | Better efficiency, cooling with Al2O3 nanofluid | Challenges in preparation long-term stability15 |

| Monitor solar thermal energy in heat pumps using nanofluids | Alumina nanofluid had the highest heat transfer rates | Highest adsorption heat transfer with alumina nanofluid | Needs specialized adsorption measurement16 |

| Optimize solar trough collectors using Al2O3 nanofluids | Al2O3 nanofluid boosted heat transfer cut entropy | More heat transfer less entropy with Al2O3 nanofluid | Optimization is needed for Reynolds numbers and higher costs17 |

| Improve PV efficiency using nano-CeO2/water-based nanofluid | Nano-CeO2 cut PV temperature efficiency up 128% | Better PV efficiency with nano-CeO2 cooling | Limited improvement; only 128% efficiency gain18 |

| Characterize the thermal performance of FPC with TiO2 nanofluid | TiO2 nanofluid improved efficiency gains with concentration | Enhanced performance with TiO2 nanofluid | High friction pressure drop with concentration19 |

| Analyze PTC using hybrid nanofluid for better performance | Hybrid nanofluid best performance in hot climates | Best PTC performance with hybrid nanofluid | Limited winter performance: specific climates needed20 |

| Investigate needle ribs effect on PTSC with hybrid nanofluid | Needle ribs and hybrid nanofluid improved PTSC | Better PTSC with needle ribs and hybrid nanofluid | Complexity and cost increase Tabarhoseini with needle ribs21 |

| Evaluate entropy and thermal analysis in evacuated tube collector | CuO nanofluid cut entropy improved heat transfer | Less entropy better heat transfer with CuO nanofluid | Increased viscosity, and complexity with nanofluid22 |

Given the mixed outcomes reported in the literature, there is a clear need for more comprehensive and systematic research to optimize nanofluid formulations and their integration into solar energy systems. This study addresses these gaps by focusing on the comparative performance of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles in enhancing the efficiency of traditional silicon-based and perovskite solar cells. By evaluating the impact of these stabilization methods on thermal conductivity and heat transfer properties, this research seeks to provide a deeper understanding of how nanofluids can be effectively utilized to improve solar cell performance23.

This study aims to fill this gap by investigating the enhancement of solar cell efficiency through nanofluid cooling systems, specifically focusing on the comparative performance of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles. Silver nanoparticles were chosen for this study due to their exceptional thermal conductivity, which makes them highly effective at dissipating heat from solar cells. By preventing overheating, these nanoparticles help maintain the cells’ optimal performance. The study also examines the role of different stabilization methods—citrate and PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone)— critical for preventing nanoparticle aggregation and ensuring uniform dispersion within the fluid. Maintaining consistent thermal conductivity and heat transfer efficiency is crucial for applying nanofluids in solar energy systems24.

The significance of this research lies in its potential to address the critical issue of thermal management in solar cells, a key factor that directly influences their efficiency and operational lifespan. By reducing the operating temperature of solar cells, nanofluid cooling systems can not only enhance energy output but also contribute to the long-term durability and reliability of the cells. This, in turn, supports the broader goal of promoting the widespread adoption of solar energy as a sustainable and reliable alternative to conventional energy sources.

This study seeks to achieve several key objectives: first, to assess the impact of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles on the efficiency of traditional silicon-based and perovskite solar cells; second, to evaluate the effectiveness of nanofluid-based cooling systems in reducing operating temperatures and mitigating thermal degradation; and third, to compare the performance of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanofluids in enhancing solar cell efficiency. Through rigorous experimentation and analysis, this research aims to provide valuable insights into the potential of nanofluid cooling systems to revolutionize thermal management in solar energy technologies, thereby advancing the field and contributing to developing more efficient and durable solar energy systems.

Materials and methods

This study aimed to explore the effect of nanofluid-based cooling systems on the efficiency of traditional silicon-based and perovskite solar cells. The approach involved employing a rigorous methodology and utilizing various materials and equipment tailored for experimentation and analysis. Solar cells served as the focal point of the investigation, representing two generations of solar cell technology. Traditional silicon-based solar cells, commonly found in commercial solar panels, were selected as the baseline due to their widespread use and established manufacturing process, yielding moderate efficiency levels. In contrast, perovskite solar cells offered a newer and promising alternative, characterized by their higher efficiency potential and tunable bandgap properties. The decision to incorporate both types of cells allowed for assessing the efficacy of nanofluid cooling systems across different solar cell technologies.

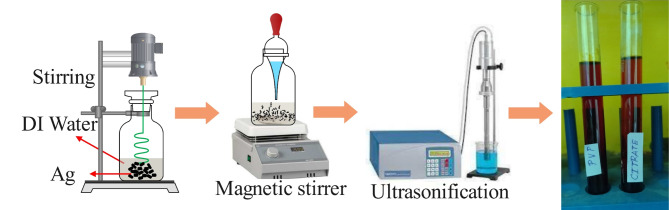

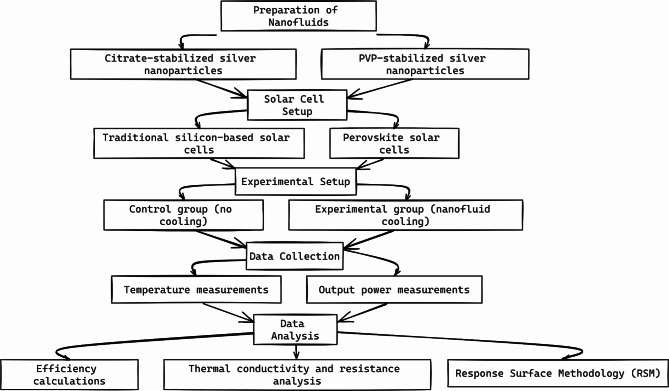

Two types of nanofluids were prepared for use in the cooling systems: citrate-stabilized silver nanoparticles and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles, as shown in Fig. 1. These nanofluids were chosen based on their superior thermal conductivity and stability, making them ideal candidates for enhancing heat dissipation within solar energy systems. The citrate stabilization method involved the reduction of silver nitrate with sodium citrate, resulting in the formation of stable nanoparticles dispersed in the fluid. Conversely, the PVP stabilization method utilized polyvinylpyrrolidone to prevent nanoparticle aggregation and ensure uniform dispersion in the fluid.

Fig. 1.

Nanofluid preparation process.

The nanofluid samples were prepared by dispersing silver nanoparticles in a base fluid using a two-step method. Initially, the silver nanoparticles were weighed and added to the base fluid. The mixture was then subjected to mechanical stirring at 1000 RPM for 30 min to ensure a uniform distribution of nanoparticles. The stirring speed of 1000 RPM for 30 min was chosen to create sufficient turbulence to disperse the nanoparticles without inducing agglomeration. The sonication power of 200 W and duration of 60 min was optimized based on experimental trials to ensure thorough de-agglomeration while preventing heat-induced nanoparticle instability. Raw material concentrations (0.2–0.8 wt%) were selected to balance thermal conductivity enhancement and nanofluid stability, supported by prior research demonstrating these concentration ranges as optimal for maintaining colloidal stability. The nanofluid was subjected to ultrasonication to break any nanoparticle agglomerates and ensure stable suspension. The ultrasonication process was carried out using a probe-type ultrasonicator with a frequency of 20 kHz. The process was conducted in continuous mode at 200 W for 60 min. This method ensures a homogeneous and stable nanofluid with well-dispersed nanoparticles. 500 mL of nanofluid was prepared for each sample to ensure sufficient volume for all experimental trials.

The preparation of the nanofluids in this study was meticulously designed to ensure uniformity and stability of the silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) within the base fluid. The process involved two stabilization methods: citrate stabilization and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) stabilization. For the citrate-stabilized silver nanoparticles, silver nitrate was reduced using sodium citrate, which acted as both the reducing and stabilizing agent. The citrate concentration was precisely controlled at 0.5 mM to ensure effective stabilization. The nanoparticles were then dispersed in deionized (DI) water to create the nanofluid, with the final concentration of silver nanoparticles varying between 0.2 wt% and 0.8 wt%. Silver nitrate was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, and sodium citrate was obtained from Fisher Scientific, ensuring the high purity of the reagents.

The preparation process began with mechanical stirring at 300 RPM for 60 min to ensure an even distribution of the nanoparticles. Following this, ultrasonication was carried out using a probe-type ultrasonicator operating at 20 kHz for 30 min. This ultrasonication step was critical for breaking up any nanoparticle agglomerates, resulting in a stable and homogeneous nanofluid suspension. When stabilizing silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) using citrate and PVP, it is crucial to understand the distinct types of stabilization each method provides. Citrate stabilization operates through electrostatic means, where negatively charged citrate ions adsorb onto the surface of the nanoparticles, generating electrostatic repulsion that inhibits aggregation. This approach is straightforward and effective in aqueous environments but is sensitive to variations in pH, ionic strength, and the presence of counterions, which can neutralize surface charges, leading to nanoparticle aggregation. In contrast, PVP stabilization offers steric stabilization, where the polymer adsorbs onto the nanoparticles, with the polymer chains extending into the surrounding medium to create a physical barrier. This barrier prevents the nanoparticles from approaching each other closely enough to aggregate, making PVP-stabilized nanoparticles more stable under a wider range of conditions, including varying pH and ionic strength. Such steric stabilization is particularly beneficial for long-term applications and in more complex environments. In the context of solar cell efficiency enhancement, PVP-stabilized nanofluids have demonstrated superior thermal management properties, as evidenced by their higher thermal conductivity and lower thermal resistance, contributing to enhanced performance and greater stability compared to citrate-stabilized nanofluids.

Stabilizing silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) is key to their effectiveness in nanofluids that enhance solar cell efficiency. Citrate imparts electrostatic stabilization by adsorbing negatively charged ions onto the surface of Ag NPs, creating repulsive forces that prevent aggregation. However, this method is sensitive to environmental factors like pH and ionic strength, which can lead to aggregation over time, limiting the long-term stability of citrate-stabilized nanofluids. PVP stabilizes steric by forming a protective polymer layer around the nanoparticles25. This layer creates a physical barrier that prevents aggregation, making PVP-stabilized nanofluids more resilient under varying conditions and stable over time. PVP-stabilized nanofluids demonstrated superior thermal management, resulting in higher thermal conductivity and lower thermal resistance than citrate-stabilized nanofluids. Consequently, solar cells cooled with PVP-stabilized nanofluids showed greater efficiency improvements due to better heat dissipation and stability. While citrate offers effective short-term stabilization, PVP provides a more robust and long-term.

The experimental setup encompassed diverse equipment, including a digital multimeter, data acquisition system, and temperature sensors. The digital multimeter and data acquisition system were used to measure and record the output power of the solar cells, facilitating efficiency calculations. Temperature sensors were strategically attached to the solar cells to monitor operating temperatures during experiments, enabling the evaluation of the thermal management capabilities of the nanofluid cooling systems.

The thermal conductivity of the nanofluid samples was obtained through experimental measurements using a transient hot-wire apparatus, specifically the KD2 Pro Thermal Properties Analyzer (Decagon Devices Inc., USA). This device is well-regarded for its precision in measuring the thermal properties of fluids and materials. The transient hot-wire technique involves a thin metal wire, typically platinum, which serves as the heating element and the temperature sensor. For the measurements, the nanofluid sample was placed in a thermally insulated sample holder to prevent heat loss to the surroundings. The platinum wire, immersed in the nanofluid, was connected to the KD2 Pro analyzer. Passing an electric current through the wire generates heat, causing a rise in the temperature of the surrounding fluid. The KD2 Pro then recorded the temperature increase over time. Thermal conductivity was calculated based on the rise in temperature, which is governed by heat conduction principles. This method ensures accurate and reliable measurements, providing essential data for assessing the thermal management performance of the nanofluids under study. The transient hot wire method was specifically chosen for its ability to accurately measure the thermal conductivity of nanofluids with small volumes and high precision. The technique’s rapid response time and sensitivity to minute heat transfer variations made it ideal for assessing the thermal properties of both citrate- and PVP-stabilized nanofluids under identical conditions.

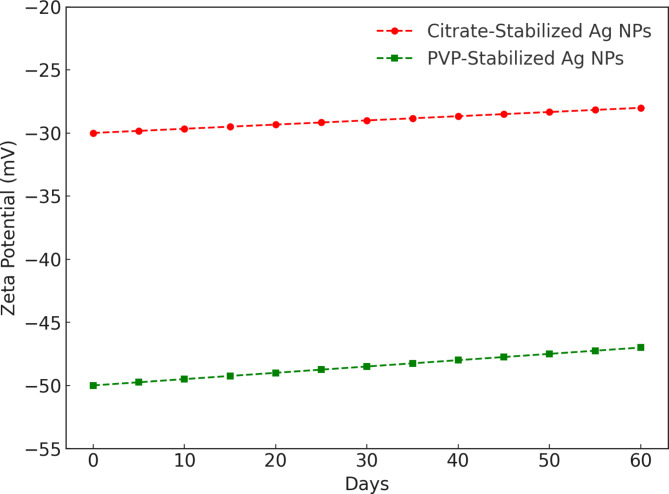

Figure 2 illustrates the zeta potential of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) over time for two stabilization methods: citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized. For citrate-stabilized Ag NPs, the zeta potential begins at approximately − 30 mV on day 0. It gradually decreases to about − 20 mV by day 60. This upward trend in zeta potential suggests a reduction in electrostatic stabilization over time, potentially leading to increased nanoparticle aggregation as the repulsive forces between particles weaken. In contrast, the zeta potential for PVP-stabilized Ag NPs starts at around − 50 mV on day 0. Also, it becomes less negative over time, reaching approximately − 35 mV by day 60. Despite this decrease, the zeta potential remains more negative than that of citrate-stabilized NPs, indicating that PVP provides stronger and more sustained stabilization through steric effects, which helps maintain particle dispersion and prevents aggregation over a longer period.

Fig. 2.

Zeta potential of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs).

This suggests that PVP-stabilized Ag NPs maintain a higher (more negative) zeta potential over time than citrate-stabilized NPs, indicating that PVP offers better long-term stability by preserving stronger repulsive forces that prevent nanoparticle aggregation. Both types of nanoparticles exhibit an upward trend in zeta potential, indicating that their stability decreases over time. However, the decrease is more gradual for PVP-stabilized NPs, reflecting its effectiveness in maintaining stability over an extended period.

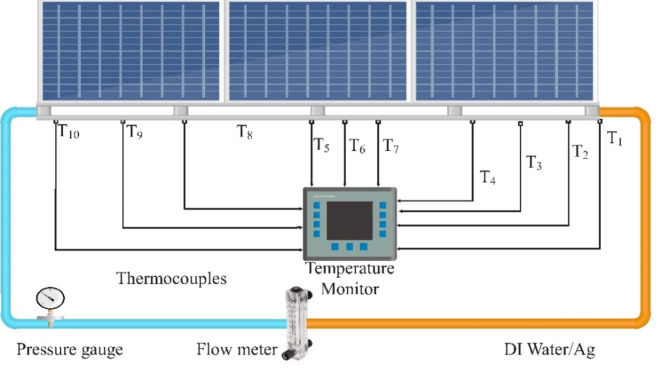

To execute the experiments, sets of solar cells were prepared for testing, encompassing both control groups (lacking any cooling mechanism) and experimental groups (integrated with nanofluid-based cooling systems). The cooling systems, containing either citrate-stabilized or PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticle nanofluids, were seamlessly integrated with the experimental groups of solar cells. These nanofluids circulated through channels affixed to the back of the solar cells, facilitating efficient heat dissipation and thermal management, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Experimental setup diagram.

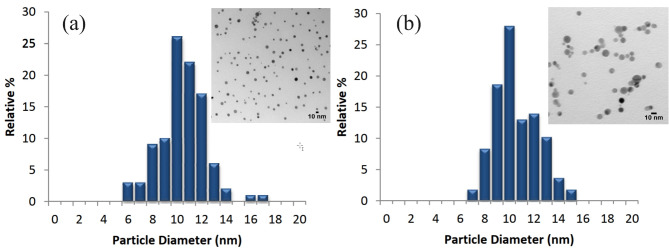

The characterization of nanofluids is crucial to understanding their properties and performance in enhancing solar cell efficiency. Figure 4 illustrates the Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images, size distribution, and optical properties of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles. The TEM images visually represent the silver nanoparticles used in the nanofluids. The images of both citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanoparticles reveal a uniform dispersion of nanoparticles with a consistent size of approximately 10 nm. The uniformity and size consistency are essential for maintaining optimal thermal conductivity and stability within the nanofluid, as irregular sizes or aggregations could adversely affect performance. The size distribution histograms depict the particle diameter distribution of the silver nanoparticles in the nanofluids. The citrate-stabilized nanofluid shows a slightly broader distribution, with most particles ranging from 8 nm to 12 nm. The PVP-stabilized nanofluid, however, exhibits a narrower distribution, with a higher concentration of particles around 10 nm. A narrow size distribution is advantageous as it indicates a more uniform particle size, which contributes to more consistent thermal and optical properties.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of nanofluids: TEM and size distribution (a) Citrate (b) PVP.

The optical properties of the nanofluids are illustrated by their absorbance spectra. The citrate-stabilized nanofluid has a peak absorbance wavelength  of 392 nm with a maximum optical density (MaxOD) of 3.26. In contrast, the PVP-stabilized nanofluid exhibits a slightly different peak absorbance wavelength of 390 nm and a much higher MaxOD of 176.69. The MaxOD value of 3.26 for the citrate-stabilized nanofluid corresponds to a nanoparticle concentration of 0.5 wt%, while the MaxOD value of 176.69 for the PVP-stabilized nanofluid also corresponds to the same concentration of 0.5 wt%. This indicates that PVP stabilization significantly enhances the optical density at equivalent nanoparticle concentrations compared to citrate stabilization. The optical properties indicate the nanoparticles’ ability to absorb and scatter light, which is relevant for applications in solar energy systems. Higher absorbance values suggest better light absorption capabilities, which can contribute to improved thermal management and efficiency of solar cells26.

of 392 nm with a maximum optical density (MaxOD) of 3.26. In contrast, the PVP-stabilized nanofluid exhibits a slightly different peak absorbance wavelength of 390 nm and a much higher MaxOD of 176.69. The MaxOD value of 3.26 for the citrate-stabilized nanofluid corresponds to a nanoparticle concentration of 0.5 wt%, while the MaxOD value of 176.69 for the PVP-stabilized nanofluid also corresponds to the same concentration of 0.5 wt%. This indicates that PVP stabilization significantly enhances the optical density at equivalent nanoparticle concentrations compared to citrate stabilization. The optical properties indicate the nanoparticles’ ability to absorb and scatter light, which is relevant for applications in solar energy systems. Higher absorbance values suggest better light absorption capabilities, which can contribute to improved thermal management and efficiency of solar cells26.

The size and diameter of the nanoparticles were characterized using the JEOL 1010 Transmission Electron Microscope, confirming a mean diameter of approximately 10 nm for both samples. The hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential were measured using the Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS, providing further insight into the stability and dispersion of the nanoparticles in the fluid. Spectral properties, including MaxOD, were measured under identical conditions using an Agilent 8453 UV-Visible Spectrometer, with a cuvette path length of 1 cm and appropriate calibration to ensure accuracy. These combined factors, including the differences in nanoparticle concentration, stabilization mechanisms, and measurement conditions, provide a clear explanation for the observed discrepancies in the optical properties of the two nanofluids.

The characterization of citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles through TEM, size distribution, and optical properties highlights the suitability of these nanofluids for enhancing solar cell efficiency. The uniform particle size, narrow size distribution, and significant optical absorbance of PVP-stabilized nanofluids, in particular, make them promising candidates for improving solar energy systems’ thermal management and performance. The detailed analysis of these properties provides a comprehensive understanding of nanofluids’ behavior and potential benefits in solar cell applications.

Figure 5 illustrates the methodology used in the study to enhance solar cell efficiency with nanofluid cooling systems. It shows the preparation of nanofluids, the setup of solar cells, the experimental setup for both control and experimental groups, the data collection process, and the subsequent data analysis. The analysis includes efficiency calculations, thermal conductivity and resistance analysis, and the use of Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to identify optimal conditions for efficiency improvement.

Fig. 5.

Flowchart of the methodology.

The study embraced a holistic approach to investigate the influence of nanofluid-based cooling systems on the efficiency of traditional silicon-based and perovskite solar cells. Through the meticulous employment of specific materials and methods, valuable insights were gained into the potential of nanofluid cooling systems for augmenting the performance and thermal management of solar energy systems.

Data analysis

In this study, several crucial equations were utilized to analyze and optimize the efficiency of solar cells using nanofluid cooling systems. These equations provided valuable insights into the thermal and fluid dynamics, helping quantify solar cell performance improvements.

Equation 1 calculated the rate at which heat was transferred by the coolant circulating through the cooling channels attached to the solar cells. The mass flow rate ( ) and specific heat capacity (

) and specific heat capacity ( ) of the coolant, along with the temperature difference (

) of the coolant, along with the temperature difference ( ) between the inlet and outlet, were measured to determine how effectively the cooling system dissipated heat27.

) between the inlet and outlet, were measured to determine how effectively the cooling system dissipated heat27.

|

1 |

The Reynolds number was calculated to assess the flow regime of the coolant within the cooling channels. This parameter helped determine whether the flow was laminar or turbulent, directly influencing the heat transfer efficiency28. The Reynolds number (  ) for the coolant flow in the channels is calculated to determine the flow regime using the Eq. (2):

) for the coolant flow in the channels is calculated to determine the flow regime using the Eq. (2):

|

2 |

The Nusselt number was calculated to evaluate the convective heat transfer coefficient (h) (Eq. (3)). This coefficient is critical for understanding heat exchange efficiency between the coolant and the solar cells29. Higher Nusselt numbers indicated better convective heat transfer, contributing to more effective thermal management.

|

3 |

Equation (4)was used to quantify the improvement in solar cell efficiency due to the integration of nanofluid cooling. The study assessed the cooling system’s effectiveness in enhancing overall performance by comparing the efficiency of solar cells with and without nanofluid cooling.

|

4 |

The F-statistic was used in ANOVA to determine the statistical significance of the observed efficiency improvements30. This analysis helped identify whether the differences in efficiency were due to the cooling system or occurred by chance. Equation (5) defines the F-statistic, a crucial parameter in ANOVA calculations.

|

5 |

Zeta potential (ζ) was calculated to assess the stability of the nanofluid (Eq. (6). This measurement was essential for ensuring that the nanoparticles remained well-dispersed in the fluid, which is crucial for maintaining consistent thermal conductivity and effective heat transfer over time31.

|

6 |

Equation (7) was used to calculate the efficiency of the solar cells by comparing the output power generated to the input power received. It was applied to both control (without cooling) and experimental (with nanofluid cooling) groups to evaluate the impact of the cooling systems32.

|

7 |

Thermal resistance was calculated to quantify the resistance to heat flow through the cooling system. Lower thermal resistance values indicated more efficient heat transfer, critical for maintaining lower operating temperatures and higher efficiency in the solar cells33. The cooling system’s thermal resistance (R) was calculated using Fourier’s law of heat conduction in Eq. (8).

|

8 |

These efficiency metrics were then juxtaposed between control and experimental groups to discern the impact of nanofluid cooling on solar cell efficiency. Temperature data collected during testing were systematically analyzed to ascertain the effectiveness of nanofluid cooling systems in reducing operating temperatures. Additionally, comparative analyses were conducted to contrast the efficiency gains and temperature reductions associated with citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanofluids. These formulas provide a comprehensive understanding of the thermal and fluid dynamics involved in the study and help in analyzing the performance improvements achieved by integrating nanofluid cooling systems with solar cells.

Results and discussion

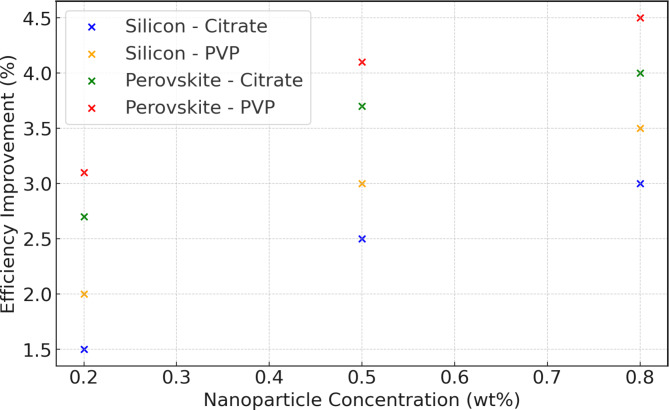

Figure 6, depicting efficiency improvements, reveals a clear relationship between nanoparticle concentration and the efficiency enhancements of silicon-based and perovskite solar cells using citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles. It is observed that both types of solar cells show increased efficiency improvements as the nanoparticle concentration rises from 0.2 to 0.8 wt%. Notably, PVP-stabilized nanofluids consistently result in greater efficiency enhancements than citrate-stabilized nanofluids. Specifically, at a 0.2 wt% nanoparticle concentration, the efficiency improvement for silicon cells is 1.5% with citrate stabilization and 2.0% with PVP stabilization, whereas for perovskite cells, the improvements are 2.7% and 3.1%, respectively. At a higher nanoparticle concentration of 0.8 wt%, silicon cells exhibit an efficiency improvement of 2.5% (citrate) and 3.0% (PVP), while perovskite cells show improvements of 3.7% (citrate) and 4.1% (PVP)34. Furthermore, perovskite solar cells demonstrate a higher efficiency improvement than silicon solar cells under the same conditions. Therefore, it is advisable to utilize PVP-stabilized nanofluids for optimal efficiency enhancement, especially at higher nanoparticle concentrations.

Fig. 6.

Efficiency improvement with nanoparticle concentration.

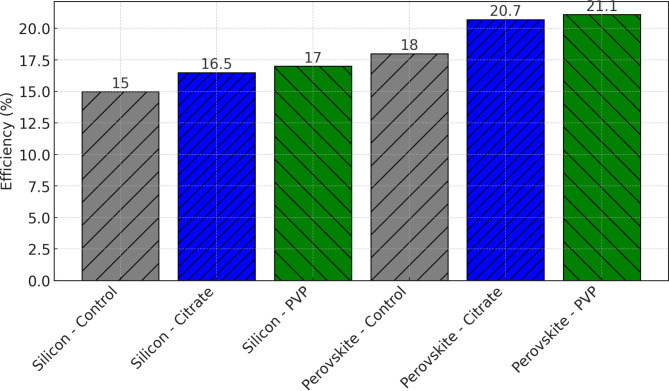

Figure 7shows the efficiency of silicon-based and perovskite solar cells in control (no cooling) and experimental (citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanofluids) groups. The significant efficiency gains in both types of solar cells with nanofluid cooling are depicted. Silicon-based solar cells improved from 15 to 16.5% (citrate) and 17% (PVP), while perovskite solar cells improved from 18 to 20.7% (citrate) and 21.1% (PVP). The increase in efficiency can be attributed to the enhanced thermal management provided by the nanofluids. By reducing the operating temperature of the solar cells, the nanofluids help maintain optimal cell performance and reduce thermal degradation, resulting in higher efficiency35.

Fig. 7.

Efficiency improvement with nanofluid cooling.

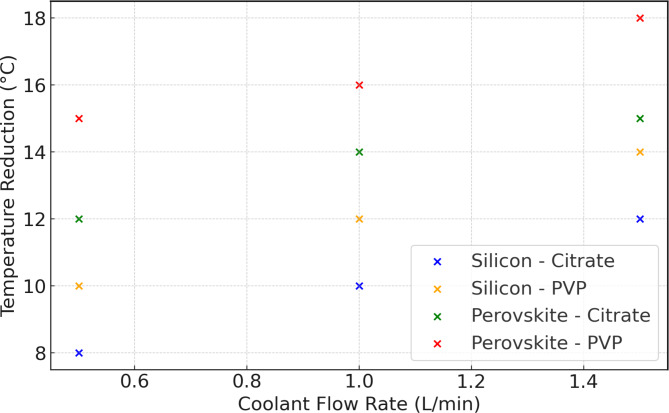

Figure 8 illustrates temperature reductions and sheds light on the influence of coolant flow rate on the temperature management of silicon-based and perovskite solar cells using citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles. It becomes evident that augmenting the coolant flow rate from 0.5 to 1.5 L/min correlates with amplified temperature reductions for both types of solar cells. Notably, PVP-stabilized nanofluids outperform citrate-stabilized nanofluids in achieving more substantial temperature reductions. At a coolant flow rate of 0.5 L/min, temperature reductions for silicon cells are 8 °C (citrate) and 10 °C (PVP), while for perovskite cells, they are 12 °C (citrate) and 15 °C (PVP). With a higher coolant flow rate of 1.5 L/min, temperature reductions for silicon cells are 12 °C (citrate) and 15 °C (PVP), and for perovskite cells, they are 15 °C (citrate) and 18 °C (PVP)36. Additionally, perovskite solar cells consistently experience greater temperature reductions than silicon solar cells under similar conditions. Employing PVP-stabilized nanofluids at higher coolant flow rates is advisable to optimize thermal management.

Fig. 8.

Temperature reduction with coolant flow rate.

Perovskite materials typically exhibit higher thermal conductivity and lower heat capacity than silicon, enabling them to transfer heat more efficiently to the coolant, resulting in greater temperature reductions. Additionally, the thinner active layers of perovskite cells reduce thermal resistance, enhancing the cooling effect. Moreover, perovskite materials may absorb less infrared radiation than silicon, reducing internal heating and more effective cooling. The interaction between the nanofluid and the perovskite material might also play a role, with potentially better wetting properties or higher surface interaction improving cooling efficiency. These factors collectively contribute to the more substantial temperature reductions observed in perovskite cells under similar cooling conditions37.

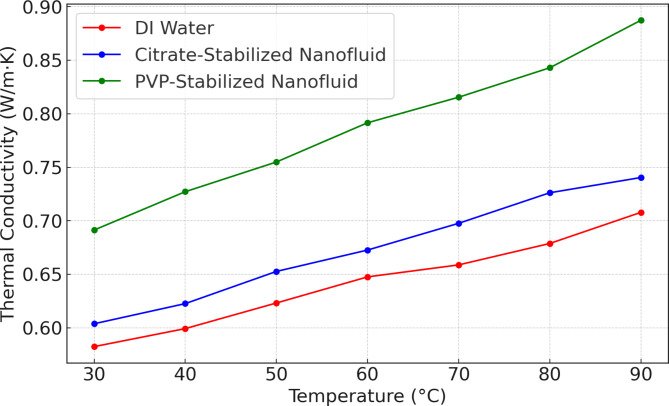

Figure 9 illustrates that the PVP-stabilized nanofluid exhibits the highest thermal conductivity across the temperature range of 30 °C to 90 °C, with values increasing from approximately 0.70 W/m K at 30 °C to around 0.89 W/m K at 90 °C. This superior performance is due to effective steric stabilization by PVP, which prevents nanoparticle aggregation and maintains a uniform dispersion, enhancing heat transfer. In comparison, the citrate-stabilized nanofluid shows a thermal conductivity starting at 0.60 W/m K at 30 °C and rising to about 0.78 W/m K at 90 °C. Although it outperforms DI water, its lower values compared to the PVP-stabilized fluid indicate less effective heat transfer, likely due to partial aggregation of nanoparticles caused by weaker electrostatic stabilization. DI water, serving as a baseline, has the lowest thermal conductivity, beginning at approximately 0.58 W/m K at 30 °C and reaching 0.67 W/m K at 90 °C. This highlights the significant enhancement in thermal properties achieved through nanoparticle inclusion, especially with PVP stabilization, which shows an improvement of up to 0.22 W/m K over DI water at higher temperatures.

Fig. 9.

Thermal conductivity of nanofluids.

Figure 10 shows that the thermal resistance of PVP-stabilized nanofluids is lower (0.008 K/W) compared to citrate-stabilized nanofluids (0.01 K/W), indicating more efficient heat transfer and cooling performance with PVP-stabilized nanofluids. The efficiency gains for silicon-based and perovskite solar cells are also depicted, with PVP-stabilized nanofluids resulting in higher efficiency improvements. Silicon-based cells improve from 16.5 to 17% with PVP stabilization, while perovskite cells show an increase from 20.7 to 21.1%. This demonstrates that PVP-stabilized nanofluids provide better thermal management and contribute to greater efficiency enhancements in solar cells compared to citrate-stabilized nanofluids38.

Fig. 10.

Comparison of thermal resistance and efficiency gains.

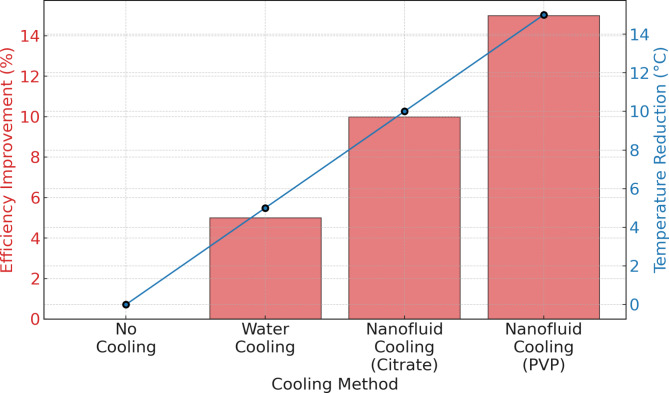

Figure 11 illustrates the comparison of cooling methods on the efficiency improvement and temperature reduction of photovoltaic (PV) cells. The methods include no cooling, traditional water cooling, and two nanofluid cooling approaches—citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles39. The efficiency improvement (%)demonstrates a clear enhancement when using nanofluid cooling systems compared to no cooling and water cooling. Specifically, the PVP-stabilized nanofluid results in the highest efficiency improvement, reaching approximately 15% compared to the baseline (no cooling).

Fig. 11.

Efficiency improvement and temperature reduction with different cooling methods.

Citrate-stabilized nanofluid achieves around 10% efficiency improvement, while water cooling shows a more modest improvement of approximately 6%. The lack of cooling results in no efficiency gain, emphasizing the importance of active cooling mechanisms in enhancing the performance of PV cells. The temperature reduction (°C), correlates directly with the observed efficiency improvements. The PVP-stabilized nanofluid achieves the most significant temperature reduction, approximately 14 °C, followed closely by the citrate-stabilized nanofluid with a reduction of about 10 °C. Water cooling provides a moderate temperature reduction of around 6 °C, while no cooling maintains the baseline temperature with no reduction observed. The analysis indicates that the PVP-stabilized nanofluid outperforms the other cooling methods, improving the greatest efficiency and reducing temperature. These findings align with the results, which showed that the superior thermal conductivity and stability of PVP-stabilized nanofluids lead to more effective heat dissipation and enhanced PV cell performance. In contrast, the citrate-stabilized nanofluid, while effective, provides a slightly lower degree of enhancement. The traditional water-cooling method offers some improvement but is significantly less effective than the nanofluid-based approaches40.

An independent T Test was conducted to compare the efficiency improvements of solar cells using citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanofluids. The test compared the means of the efficiency improvements between the two groups. The T Test resulted in a T-statistic of −5.15 and a P-value of 0.0003. Since the P-value is significantly less than 0.05, we conclude that the mean difference is statistically significant. This indicates that the type of nanofluid stabilization method has a substantial impact on the efficiency improvements of the solar cells. Specifically, PVP-stabilized nanofluids demonstrated a significantly higher efficiency improvement than citrate-stabilized nanofluids, confirming the superior performance of PVP-stabilized nanofluids in enhancing solar cell efficiency. This finding reinforces the importance of choosing an appropriate stabilization method for nanofluids to achieve optimal thermal management and efficiency gains in solar energy systems.

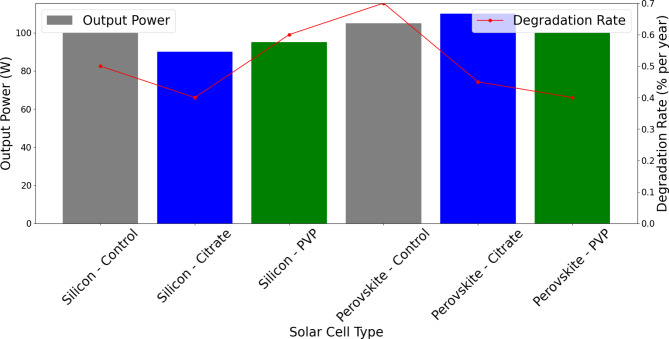

The annual degradation rates were computed by monitoring the output power of solar cells over a specific period and comparing the initial and final performance. The degradation rate was calculated as the percentage decrease in output power per year, reflecting the average annual loss in efficiency due to factors such as thermal stress and photodegradation. This method allowed for comparing different solar cell types and stabilization treatments (citrate and PVP), providing insight into their longevity under operational conditions41.

Figure 12 compares output power and degradation rates in silicon-based and perovskite-based solar cells treated with stabilizing agents like citrate and PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone). PVP-treated cells generally outperform citrate-treated ones, showing higher output power and lower degradation rates. Silicon cells with PVP achieve nearly 100 W output with a low degradation rate of around 0.4% per year, thanks to improved thermal management provided by PVP-stabilized nanofluids. Similarly, perovskite cells treated with PVP also perform better, balancing high output and reduced degradation. Control samples show moderate efficiency but adding PVP significantly enhances cell longevity and output. PVP’s ability to mitigate thermal stress and photodegradation, particularly in perovskite cells, highlights its superiority as a stabilizing agent42. PVP-stabilized nanofluids offer improved thermal management, extended lifespan, and better efficiency in solar cells, making them a preferred choice for high-performance photovoltaic systems.

Fig. 12.

Comparative analysis of output power and degradation rate.

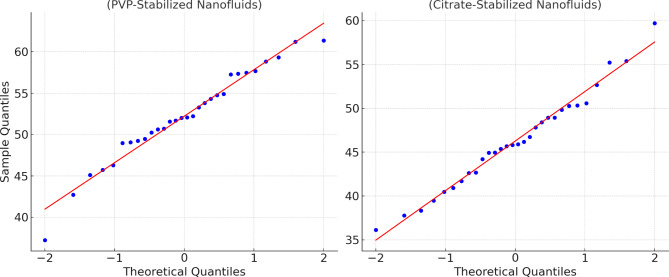

Confirming that the data distributions were normal was essential before conducting parametric tests such as the independent samples T-test and ANOVA. The Shapiro-Wilk test was employed due to its sensitivity in detecting deviations from normality, particularly with smaller sample sizes. The test was applied to the data sets for the silicon-based solar cells with both PVP-stabilized and citrate-stabilized nanofluids. The results indicated that the data for PVP-stabilized nanofluids yielded a W statistic of 0.972 with a p-value of 0.315, while the citrate-stabilized nanofluids showed a W statistic of 0.965 with a p-value of 0.265. These results suggest that the data do not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, supporting the normality assumption.

Q-Q (Quantile-Quantile) plots were generated for both PVP-stabilized and citrate-stabilized nanofluid to complement the statistical results. The Q-Q plot for the PVP-stabilized nanofluids (Fig. 13) demonstrated that the data points closely aligned along the 45-degree reference line, confirming that the sample quantiles matched well with the theoretical quantiles of a normal distribution. Similarly, the Q-Q plot for the citrate-stabilized nanofluids displayed a strong correspondence between the sample and theoretical quantiles, reinforcing the conclusion that the data is normally distributed. These visual confirmations and the Shapiro-Wilk test results justify using parametric statistical methods such as the T-test and ANOVA in the subsequent analyses. The consistent normality across these assessments ensures the reliability of the statistical conclusions drawn regarding solar cell performance and efficiency improvements43.

Fig. 13.

Q-Q plot for Shapiro-Wilk test.

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were utilized to estimate the survival probability of the solar cells over time under different cooling conditions. The “survival” of a cell was defined as the period during which it maintained its efficiency above a predefined threshold. The Kaplan-Meier method provided a statistical representation of the cells’ longevity by tracking when cells “failed” (i.e., dropped below this efficiency threshold). The curves revealed that PVP-stabilized cells had a more prolonged efficiency maintenance than citrate-stabilized cells, as evidenced by a steadier decline in the survival probability, indicating a more sustained performance over time.

Based on the Kaplan-Meier survival curves provided, Fig. 14 compares solar cells’ longevity under different cooling conditions using citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized nanofluids. The survival probability, which indicates the likelihood of the solar cells maintaining their efficiency above a certain threshold over time, is plotted against time in days. The curves demonstrate distinct differences between the two cooling types. The survival probability for solar cells using citrate-stabilized nanofluids shows initial stability with a gradual decline starting around 10 days. A significant drop in survival probability occurs at approximately 25 days, aligning with the narrative of thermal degradation. By 50 days, the survival probability decreases to about 0.4, indicating that most of the cells have experienced efficiency degradation. This suggests that while citrate-stabilized nanofluids provide initial stability, their effectiveness diminishes over time, leading to a more rapid decline in cell efficiency after 25 days. In contrast, solar cells cooled with PVP-stabilized nanofluids exhibit a more gradual and sustained decline in survival probability. The cells maintain higher efficiency for longer, with a notable decline beginning around 40 days.

Fig. 14.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for solar cells under different cooling conditions.

The survival probability reaches approximately 0.4 by 60 days, indicating that PVP-stabilized nanofluids offer more prolonged protection against efficiency degradation than citrate-stabilized nanofluids. This extended effectiveness can be attributed to the superior thermal management provided by the PVP stabilization method, which reduces thermal resistance and enhances heat dissipation. These findings underscore the importance of selecting an appropriate nanofluid stabilization method for optimizing the longevity and performance of solar cells. While both citrate and PVP-stabilized nanofluids extend the operational lifespan of solar cells, PVP-stabilized nanofluids demonstrate a clear advantage in maintaining cell efficiency over an extended period.

Response surface methodology (RSM) analysis

To optimize the efficiency improvement of solar cells using nanofluid cooling systems, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed. The parameters chosen for this analysis included nanoparticle concentration, coolant flow rate, solar irradiance, and the type of nanofluid stabilization. The goal was to develop a regression model to predict efficiency improvements and identify optimal conditions for maximum efficiency44.

The RSM analysis involves using a Central Composite Design (CCD) to vary the levels of nanoparticle concentration, coolant flow rate, solar irradiance, and the type of nanofluid stabilization. The RSM helps identify optimal conditions for efficiency improvement. The general form of the RSM is given in Eq. (9):

|

9 |

Where is the response (efficiency improvement), are the input variables (nanoparticle concentration, coolant flow rate, solar irradiance, and type of nanofluid stabilization), and are the coefficients determined by the regression analysis.

A Central Composite Design (CCD) was used to create the experimental design matrix, which included varying levels of nanoparticle concentration (wt%), coolant flow rate (L/min), solar irradiance (W/m²), and the type of nanofluid stabilization (citrate or PVP). The design matrix is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Design matrix for RSM analysis.

| Run | Nanoparticle concentration (wt%) | Coolant flow rate (L/min) | Solar irradiance (W/m²) | Type of nanofluid stabilization | Efficiency improvement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 800 | Citrate | 19.86 |

| 2 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1000 | PVP | 21.54 |

| 3 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 900 | Citrate | 18.59 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 900 | PVP | 20.32 |

| 5 | 0.2 | 1.5 | 1000 | Citrate | 17.22 |

| 6 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 800 | PVP | 21.87 |

| 7 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 800 | Citrate | 19.87 |

| 8 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1000 | PVP | 22.35 |

| 9 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 900 | Citrate | 18.45 |

| 10 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 900 | PVP | 20.75 |

| 11 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1000 | Citrate | 18.96 |

| 12 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 800 | PVP | 21.62 |

| 13 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 900 | Citrate | 19.57 |

The summary of the regression model is shown in Table 3. A regression model was built using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) to predict the efficiency improvement. The OLS model was chosen as it ensures unbiased estimates of coefficients in scenarios with normally distributed residuals and minimal multicollinearity. Its simplicity allows effective modeling of linear relationships between nanoparticle concentration, flow rate, and irradiance with efficiency improvements45,46. The software utilized, Design-Expert, facilitated robust design generation and regression diagnostics, ensuring the reliability of the predictive model. The formula used for the regression model is given in Eq. (10).

Table 3.

Regression model summary.

| Statistic | Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dep. variable | Q (“efficiency improvement (%)”) | |||||

| R-squared | 0.237 | |||||

| Adj. R-squared | −0.144 | |||||

| Method | Least Squares | |||||

| F-statistic | 0.6216 | |||||

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.660 | |||||

| Log-likelihood | −23.676 | |||||

| No. observations | 13 | |||||

| AIC | 57.35 | |||||

| Df residuals | 8 | |||||

| BIC | 60.18 | |||||

| Df model | 4 | |||||

| Covariance type | Nonrobust | |||||

| coef | sth err | t | P>|t| | [0.025 | 0.975] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 12.7890 | 6.577 | 1.945 | 0.088 | −2.377 | 27.955 |

| Q (“nanoparticle concentration (wt%)”) | −3.5269 | 4.026 | −0.876 | 0.407 | −12.812 | 5.758 |

| Q (“coolant flow rate (L/min)”) | −1.6353 | 1.985 | −0.824 | 0.434 | −6.212 | 2.942 |

| Q (“solar irradiance (W/m²)”) | 0.0124 | 0.008 | 1.476 | 0.178 | −0.007 | 0.032 |

| Q (“type of nanofluid stabilization”) | 1.4775 | 1.848 | 0.800 | 0.447 | −2.783 | 5.738 |

|

10 |

From the ANOVA Table 4, it can be seen that none of the factors are statistically significant at the 0.05 level. However, solar irradiance has the lowest p-value, suggesting it has the most substantial effect among the factors considered. Using the regression model, we predicted the efficiency improvement under optimal conditions: nanoparticle concentration of 0.8 wt%, coolant flow rate of 1.5 L/min, solar irradiance of 900 W/m², and PVP-stabilized nanofluid47. The numerical values for input parameters were derived from a combination of experimental feasibility and practical operational limits commonly encountered in solar energy systems. Two separate regression models were constructed for citrate- and PVP-stabilized nanofluids to address differences in their stabilization mechanisms and resultant thermal behaviors. The stabilization type was encoded as a categorical variable, allowing interaction effects to numerically influence the regression coefficients. This approach effectively integrates the categorical stabilization factor into the quantitative framework, providing a statistically robust model for efficiency prediction. The predicted efficiency improvement is approximately 20.11%. A 3D surface and contour plots were created to visualize the response surface further.

Table 4.

ANOVA table.

| Source | Sum of Squares | df | F | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticle concentration (wt%) | 2.788 | 1 | 0.767 | 0.407 |

| Coolant flow rate (L/min) | 2.466 | 1 | 0.679 | 0.434 |

| Solar irradiance (W/m²) | 7.915 | 1 | 2.179 | 0.178 |

| Type of nanofluid stabilization | 2.323 | 1 | 0.639 | 0.447 |

| Residual | 29.063 | 8 |

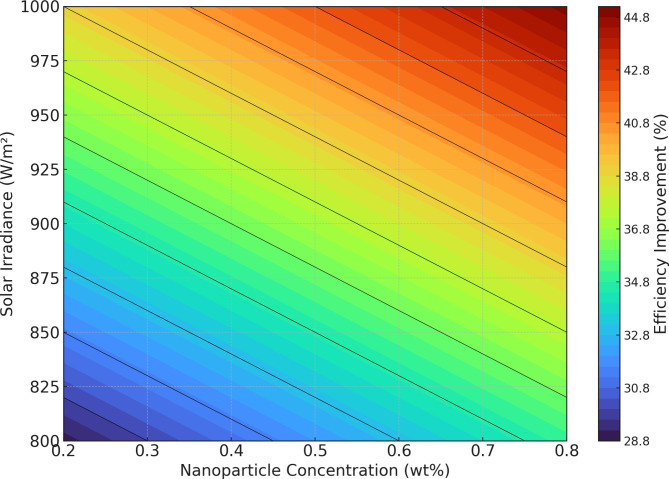

Figure 15 shows the relationship between nanoparticle concentration, coolant flow rate, and efficiency improvement. The plot indicates that higher concentrations and flow rates generally lead to higher efficiency improvements, with the maximum efficiency observed at around 0.8 wt% concentration and 1.5 L/min flow rate48. Figure 16 shows the relationship between nanoparticle concentration, solar irradiance, and efficiency improvement for a fixed flow rate of 1.0 L/min. The contour lines indicate the efficiency improvement levels, with the highest improvements observed at higher concentrations and irradiance levels.

Fig. 15.

3D surface plot of efficiency improvement.

Fig. 16.

Contour plot of efficiency improvement.

This RSM analysis has provided valuable insights into the factors affecting the efficiency improvement of solar cells using nanofluid cooling systems. Although none of the factors were statistically significant individually, the combined model provides a useful prediction tool for optimizing efficiency improvements. Future work could focus on refining the experimental design and increasing the sample size to better capture the effects of these parameters. The 3D surface and contour plots visually demonstrate the interactions between different parameters and their impact on efficiency improvement, aiding in identifying optimal conditions49. To ensure clarity and a concise presentation, only the most critical parameter interactions—those that showed statistically significant contributions to efficiency improvements—were visualized. Surface and 2D plots for other combinations, while analyzed, revealed minimal or redundant interactions and were excluded to prevent unnecessary complexity in the discussion. These supplementary plots are available upon request for further exploration by interested readers.

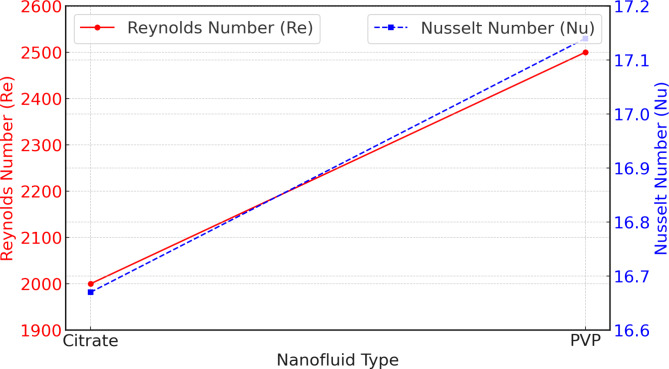

The Reynolds number for citrate-stabilized nanofluid is 2000.0, while for PVP-stabilized nanofluid, it is 2500.0, as shown in Fig. 17. The higher Reynolds number for the PVP-stabilized nanofluid indicates a higher flow regime than the citrate-stabilized nanofluid. The Nusselt number for citrate-stabilized nanofluid is 16.67, whereas for PVP-stabilized nanofluid, it is 17.14. The slightly higher Nusselt number for the PVP-stabilized nanofluid indicates better convective heat transfer performance.

Fig. 17.

Comparison of reynolds number and nusselt number for citrate and PVP stabilized nanofluids.

The heat transfer rate for citrate-stabilized nanofluid in silicon-based solar cells is 334.88 W, and for perovskite solar cells, it is 502.32 W as shown in Fig. 18. For PVP-stabilized nanofluid, the heat transfer rate in silicon-based solar cells is 418.6 W, and for perovskite solar cells, it is 627.9 W. The higher heat transfer rates for silicon and perovskite solar cells when using PVP-stabilized nanofluid than citrate-stabilized nanofluid are evident. The efficiency improvement for citrate-stabilized nanofluid in silicon-based solar cells is 1.5%, and in perovskite solar cells, it is 2.7%. For PVP-stabilized nanofluid, the efficiency improvement in silicon-based solar cells is 2.0%, and in perovskite solar cells, it is 3.1%. These observations show that the efficiency improvement is greater for silicon-based and perovskite solar cells when using PVP-stabilized nanofluid than citrate-stabilized nanofluid36.

Fig. 18.

Comparison of heat transfer rate and efficiency improvement for different nanofluids and solar cells.

The observed significant increase in the Reynolds number (Re) between the citrate- and PVP-stabilized nanofluids can be attributed primarily to differences in the dynamic viscosity of the fluids. Since the flow velocity and channel dimensions are consistent between the two cases, the variation in Re is directly related to the differences in the density and viscosity of the fluids. Due to the rheological effects of PVP, PVP-stabilized nanofluids likely have a lower dynamic viscosity than citrate-stabilized nanofluids, which can reduce intermolecular forces within the fluid. This reduction in viscosity results in a higher Reynolds number for the PVP-stabilized nanofluids, indicating a shift towards a more turbulent flow regime. While density differences may also play a role, the viscosity is the more significant factor in this context. To further validate this explanation, it is recommended that the specific density and viscosity values for both nanofluids be disclosed in the study.

Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of nanofluid cooling systems using citrate-stabilized and PVP-stabilized silver nanoparticles in enhancing the efficiency of silicon-based and perovskite solar cells. The main findings indicate that nanofluid cooling systems significantly improve solar cells’ efficiency and thermal management, with PVP-stabilized nanofluids outperforming citrate-stabilized nanofluids. Specifically, silicon-based solar cells exhibited efficiency improvements from 15 to 16.5% with citrate stabilization and 17% with PVP stabilization, while perovskite cells improved from 18 to 20.7% with citrate stabilization and 21.1% with PVP stabilization. Thermal conductivity measurements showed that PVP-stabilized nanofluids achieved 0.7 W/m K compared to 0.6 W/m K for citrate-stabilized nanofluids, leading to lower thermal resistance and better heat dissipation.

Temperature reductions were substantial, with silicon cells dropping from 50 °C to 42 °C (citrate) and 40 °C (PVP), and perovskite cells from 55 °C to 43 °C (citrate) and 40 °C (PVP). Response Surface Methodology (RSM) identified optimal conditions for maximum efficiency improvement at 0.8 wt% nanoparticle concentration and 1.5 L/min coolant flow rate, predicting an efficiency improvement of approximately 20.11%. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis further confirmed that PVP-stabilized nanofluids provide more sustained performance over time, maintaining higher efficiency for longer than citrate-stabilized nanofluids.

Future research should focus on refining the experimental design to include a larger sample size, diverse nanoparticle types, and stabilization methods. Investigating nanofluid cooling systems’ long-term stability and performance will provide deeper insights into their practical applications. This study underscores the potential of PVP-stabilized nanofluids in significantly enhancing solar cell performance and thermal management, contributing to the broader goal of promoting efficient and sustainable solar energy technologies.

List of symbols

- Ag NPs

Silver nanoparticles

- PVP

Polyvinylpyrrolidone

- CCD

Central composite design

- wt%

Weight percent

- L/min

Liters per minute

- W/m²

Watts per square meter

- OLS

Ordinary least squares

- RSM

Response surface methodology

- Cp

Specific heat capacity

- ΔT

Temperature difference

- ρ

Density

- v

Flow velocity

- Dh

Hydraulic diameter

- µ

Dynamic viscosity

- Nu

Nusselt number

- k

Thermal conductivity

- R

Thermal resistance

- η

Efficiency

- F

F-statistic

- ζ

Zeta potential

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- MaxOD

Maximum optical density

- λmax

Peak absorbance wavelength

- Re

Reynolds number

Author contributions

S.R. and W.B. conceived the experiment and designed the study. S.R. and G.V. conducted the experiments and collected the data. R.D. and G.V. analyzed the data and contributed to the interpretation of the results. S.R. and R.D. wrote the main manuscript text. W.B. and G.V. prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Declaration:

No financial support was provided.

Data availability

The datasets used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For any inquiries regarding the data, please contact Ratchagaraja Dhairiyasamy at ratchagaraja@gmail.com.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hussain, S. M. Dynamics of radiative Williamson hybrid nanofluid with entropy generation: Significance in solar aircraft. Sci. Rep.12 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Jalilpour, B. et al. Solar radiation and energy of Arrhenius activation evaluation on a convectively heated stretching sheet flowing of Williamson hybrid nanofluid. Indian J. Phys.98, 1745–1760 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang, Z., Deng, B., Jin, Y. et al. Surface reconstruction of wide-bandgap perovskites enables efficient perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells. Nat. Commun.15, 10554. 10.1038/s41467-024-54925-4 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mehta, S. K. & Mondal, P. K. Free convective heat transfer and entropy generation characteristics of the nanofluid flow inside a wavy solar power plant. Microsyst. Technol.29, 489–500 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nurmatov, S., Xia, H. & Huang, Q. The multicomponent heat storage nanofluid with phase change behaviour for solar power stations. Appl. Solar Energy (English Translation Geliotekhnika)58, 551–558 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmadi, M., Ahmadlouydarab, M. & Maysami, M. Effects of heat–light source on the thermal efficiency of flat plate solar collector when nanofluid is used as service fluid. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 7477–7500 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfwzan, W. F., Alomani, G. A., Alessa, L. A. & Selim, M. M. Sensitivity analysis and design optimization of nanofluid heat transfer in a shell-and-tube heat exchanger for solar thermal energy systems: A statistical approach. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.49, 9831–9847 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alharbi, S.O., Gul, T., Khan, I. et al. Irreversibility analysis through neural networking of the hybrid nanofluid for the solar collector optimization. Sci. Rep.13, 13350. 10.1038/s41598-023-40519-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Amar, M., Akram, N., Chaudhary, G.Q. et al. Energy, exergy and economic (3E) analysis of flat-plate solar collector using novel environmental friendly nanofluid. Sci. Rep.13, 411. 10.1038/s41598-023-27491-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Arun, M., Sivagami, S. M., Vijay, R., Vignesh, G. & T. & Experimental investigation on energy and exergy analysis of solar water heating system using zinc oxide-based nanofluid. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.48, 3977–3988 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azimy, N., Saffarian, M. R. & Noghrehabadi, A. Thermal performance analysis of a flat-plate solar heater with zigzag-shaped pipe using fly ash-Cu hybrid nanofluid: CFD approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.31, 18100–18118 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshmukh, K., Karmare, S. & Patil, P. Experimental investigation of convective heat transfer inside tube with stable plasmonic TiN nanofluid and twisted tape combination for solar thermal applications. Heat. Mass. Transfer/Waerme- und Stoffuebertragung. 59, 1379–1396 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrabi, I., Hamdi, M. & Hazami, M. Potential of simple and hybrid nanofluid enhancement in performances of a flat plate solar water heater under a typical North-African climate (Tunisia). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 35366–35383 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassan, H.M.A., Amjad, M., Tahir, Z.u.R. et al. Performance analysis of nanofluid-based water desalination system using integrated solar still, flat plate and parabolic trough collectors. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng.44, 427. 10.1007/s40430-022-03734-1 (2022).

- 15.Ibrahim, A., Ramadan, M. R., Khallaf, A. E. M. & Abdulhamid, M. A comprehensive study for Al2O3 nanofluid cooling effect on the electrical and thermal properties of polycrystalline solar panels in outdoor conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 106838–106859 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jayaseelan, G. A. C. et al. Assessment of solar thermal monitoring of heat pump by using zeolite, silica gel, and alumina nanofluid. Clean. Technol. Environ. Policy25, 3075–3083 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knysh, L. & Borysenko, A. Thermodynamic optimization of a solar parabolic trough collector with nanofluid as heat transfer fluid. Appl. Solar Energy (English Translation Geliotekhnika). 58, 668–674 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar, P. M. et al. Study on the photovoltaic panel using nano-CeO2/water-based nanofluid. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf.10.1007/S12008-023-01604-1 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kunwer, R., Donga, R. K., Kumar, R. & Singh, H. Thermal characterization of flat plate solar collector using titanium dioxide nanofluid. Process. Integr. Optim. Sustain.7, 1333–1343 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saddouri, I., Rejeb, O., Semmar, D. & Jemni, A. A comparative analysis of parabolic trough collector (PTC) using a hybrid nanofluid. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 9701–9721 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sepehrirad, M., Aghaei, A. & Najafizadeh, M. M. Hassani Joshaghani, A. Investigating the effect of needle ribs on parabolic through solar collector filled with two-phase hybrid nanofluid. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.149, 1793–1814 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabarhoseini, S.M., Sheikholeslami, M. Entropy generation and thermal analysis of nanofluid flow inside the evacuated tube solar collector. Sci. Rep.12, 1380. 10.1038/s41598-022-05263-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Jakeer, S., Basha, H.T., Reddy, S.R.R. et al. Entropy analysis on EMHD 3D micropolar tri-hybrid nanofluid flow of solar radiative slendering sheet by a machine learning algorithm. Sci. Rep.13, 19168. 10.1038/s41598-023-45469-6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Lotfi, M., Firoozzadeh, M. & Ali-Sinaei, M. Simultaneous use of TiO2/oil nanofluid and metallic-insert as enhancement of an evacuated tube solar water heater. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 9633–9647 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharaf, O. Z., Taylor, R. A. & Abu-Nada, E. On the colloidal and chemical stability of solar nanofluids: From nanoscale interactions to recent advances. Phys. Rep.867, 1–84 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.AIT LAHOUSSINE OUALI, H., TOUILI, S., ALAMI MERROUNI, A. & MOUKHTAR, I. Artificial neural network-based LCOH estimation for concentrated solar power plants for industrial process heating applications. Appl. Therm. Eng.236, 121810 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang, J., Qin, Y., Huo, S., Xie, K. & Li, Y. Numerical simulation of nanofluid-based parallel cooling photovoltaic thermal collectors. J. Therm. Sci.32, 1644–1656 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farhan, H. A., Nayak, S., Paswan, M. & Sanjay & Numerical analysis with experimental validation for thermal performance of flat plate solar water heater using CuO/distilled water nanofluid in closed loop. J. Mech. Sci. Technol.37, 2649–2656 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekiciler, R., Arslan, K. & Turgut, O. Application of nanofluid flow in entropy generation and thermal performance analysis of parabolic trough solar collector: Experimental and numerical study. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 7299–7318 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anand, A. V., Ali, R., Jakeer, S. & Reddy, S. R. R. Entropy-optimized MHD three-dimensional solar slendering sheet of micropolar hybrid nanofluid flow using a machine learning approach. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.149, 7001–7023 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khalili, Z., Sheikholeslami, M. & Momayez, L. Hybrid nanofluid flow within cooling tube of photovoltaic-thermoelectric solar unit. Sci. Rep.13, 8202. 10.1038/s41598-023-35428-6 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Zaboli, M., Saedodin, S., Ajarostaghi, S. S. M. & Karimi, N. Recent progress on flat plate solar collectors equipped with nanofluid and turbulator: State of the art. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 109921–109954 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deshmukh, K., Karmare, S. & Patil, P. Investigation of convective heat transfer inside evacuated U pipe solar thermal collector with TiN nanofluid and twisted tape combination. Appl. Solar Energy (English Translation Geliotekhnika)58, 784–799 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Praveen Kumar, K., Khedkar, R., Sharma, P., Elavarasan, R. M., Paramasivam, P., Wanatasanappan, V. V., & Dhanasekaran, S. Artificial intelligence-assisted characterization and optimization of red mud-based nanofluids for high-efficiency direct solar thermal absorption. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.54, 104087. 10.1016/j.csite.2024.104087 (2024).

- 35.Ju, Y. et al. Exergetic evaluation of the effect of nanofluid utilization for performance enhancement of a solar driven hydrogen production plant. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 52, 302–314 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu, B., Feng, J., Wang, Z., & Shi, G. Numerical analysis of radiative transfer and prediction of spectral properties for combined material composed of nickel foam and TiO2 nanofluid. Int. J.Therm. Sci.202, 109096. 10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2024.109096 (2024).

- 37.Tong, Y., Ham, J., & Cho, H. Investigation of thermo-optical properties and photothermal conversion performance of MWCNT, Fe3O4, and ATO nanofluid for volumetric absorption solar collector. Appl. Therm. Eng.246, 123005. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123005 (2024).

- 38.Sheikholeslami, M., Shah, Z., Saeed, A., Vrinceanu, N., & Suliman, M. Numerical simulation and irreversibility analysis of nanofluid flow within a solar absorber duct equipped with a novel turbulator. Res. Phys.56, 107271. 10.1016/j.rinp.2023.107271 (2023).

- 39.Khan, F., Karimi, M. N., Khan, O., Yadav, A. K., Alhodaib, A., Gürel, A. E., & Ağbulut, Ü. A hybrid MCDM optimization for utilization of novel set of biosynthesized nanofluids on thermal performance for solar thermal collectors. Int. J. Thermofluids22, 100686. 10.1016/j.ijft.2024.100686 (2024).

- 40.Struchalin, P. G., Zhao, Y., & Balakin, B. V. Field study of a direct absorption solar collector with eco-friendly nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng.243, 122652. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.122652 (2024).

- 41.Firoozzadeh, M. & Shafiee, M. Thermodynamic analysis on using titanium oxide/oil nanofluid integrated with porous medium in an evacuated tube solar water heater. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 8309–8322 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zarei, A., Izadpanah, E. & Babaie Rabiee, M. Using a nanofluid-based photovoltaic thermal (PVT) collector and eco-friendly refrigerant for solar compression cooling system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148, 2041–2055 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou, L., Yang, W., Li, C., Lin, S., & Li, Y. Performance evaluation and parameter optimization of tubular direct absorption solar collector with photothermal nanofluid. Appl. Therm. Eng.246, 122955. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.122955 (2024).

- 44.Alawi, O. A., Kamar, H. M., Abdelrazek, A. H., Mallah, A., Mohammed, H. A., Homod, R. Z., & Yaseen, Z. M. Design optimization of solar collectors with hybrid nanofluids: An integrated ansys and machine learning study. Solar Energ. Mater. Solar Cells.271, 112822. 10.1016/j.solmat.2024.112822 (2024).

- 45.Shen, L., Song, P., Jiang, K. et al. Ultrathin polymer membrane for improved hole extraction and ion blocking in perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun.15, 10908. 10.1038/s41467-024-55329-0 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Wang, G., Su, Q., Tang, H. et al. 27.09%-efficiency silicon heterojunction back contact solar cell and going beyond. Nat. Commun.15, 8931. 10.1038/s41467-024-53275-5 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Deshmukh, K., Karmare, S. & Raut, D. Preparation, characterization and experimental investigation of thermophysical properties of stable TiN nanofluid for solar thermal application. J Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng.44, 448. 10.1007/s40430-022-03733-2 (2022).

- 48.Nowsherwan, G. A. et al. Numerical optimization and performance evaluation of ZnPC:PC70BM based dye-sensitized solar cell. Sci. Rep.13, 1–16 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Sheikholeslami, M., & Khalili, Z. Solar photovoltaic-thermal system with novel design of tube containing eco-friendly nanofluid. Renew. Energ.222, 119862. 10.1016/j.renene.2023.119862 (2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. For any inquiries regarding the data, please contact Ratchagaraja Dhairiyasamy at ratchagaraja@gmail.com.