Abstract

No biomarker can effectively screen for early gastric cancer (EGC). Players in the A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)-natural killer group 2 member D (NKG2D) receptor axis may have a role for that. As a proof-of-concept pilot study, the expression of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, ADAM17, and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I chain-related sequence A (MICA), a ligand for NKG2D, in gastric cancer was investigated in silico using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Subsequently, the mRNA and protein expression levels of these markers except ADAM8 were tested in blood samples from patients with EGC and healthy controls. In the TCGA data analyses, EGC tissues (n = 57) expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 than normal tissues (n = 35) (p < 0.005). In human blood sample analyses, ADAM12 (p = 0.0007), ADAM17 mRNA (p < 0.0001) and ADAM10 (p < 0.0017) protein were significantly elevated in patients with EGC (n = 27 for mRNA and n = 25 for protein) compared to the controls (n = 30 for mRNA and n = 26 for protein). Areas under the curves calculated by receiver-operating characteristic analysis for ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein were 0.7568 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.6334 to 0.8802), 0.8062 (95% CI: 0.6889 to 0.9234; p < 0.0001), and 0.8108 (95% CI: 0.6895 to 0.9320; p = 0.0001), respectively. Thus, ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein levels in peripheral blood could hold potential as biomarkers for screening EGC, and further investigations are required.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-84237-y.

Keywords: ADAM12, ADAM17, ADAM10, Gastric cancer, Biomarker

Subject terms: Gastroenterology, Oncology

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer death1. The survival of patients with gastric cancer differs widely depending on the stage. The 5-year survival rate of patients with gastric cancer is over 70% for localized tumors, 30% for regional tumors, and less than 5% for tumors with distant metastasis2. Furthermore, recurrence rate is 4.0% after endoscopic resection and 0.8% after surgical resection of early gastric cancer (EGC)3. Thus, early detection is critical for survival, and continuous effort to detect recurrence early even after resection is required. There is no noninvasive biomarker that can effectively screen for early-stage gastric cancer. Current screening methods for gastric cancer rely on endoscopic examinations. Although endoscopic examination is very safe, potential risks due to its invasiveness necessitate the development of noninvasive biomarkers.

A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM)-natural killer group 2 member D receptor (NKG2D) axis may serve as a new source for cancer diagnostics. NKG2D, an activating receptor of natural killer (NK) cells, and its ligands, NKG2DL, expressed on cancer cells function as an immune checkpoint where cancer cells should be inspected4. If the NKG2D recognizes NKG2DL, NK cells send out a killing signal, which leads to apoptosis of cancer cells4. To evade this, cancer cells upregulate the expression of ADAMs4. ADAMs cleave NKG2DL into a soluble form4. This soluble NKG2DL, in turn, binds with NKG2D causing downregulation of NKG2D4. In this way, cancers evade NK cell’s immune surveillance4.

Previous studies have demonstrated that ADAM expression is upregulated in gastric cancer. In gastric cancer tissues, the protein expression of ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 was increased5. In metastatic lymph nodes of gastric cancer, the protein expression of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 was increased5. In addition, the role of ADAMs is vital for gastric cancer. As an example, ADAM9 mRNA expression and ADAM9 protease activity were increased in gastric cancer cell lines6. When gastric cancer cells were knocked down with si-ADAM9 RNA or inhibited by ADAM9 blocking antibody, cancer cell progression was significantly suppressed6. In an animal model of gastric cancer, miR-129-5p suppressed ADAM9 protein expression and tumor growth7.

In a few clinical studies, the potential roles of ADAMs and MHC class I polypeptide-related sequence A(MICA), an NKG2DL, as cancer-screening biomarkers have been demonstrated. ADAM8 protein in peripheral blood was significantly increased in patients with EGC compared to healthy normal controls8. Moreover, the levels were observed to increase gradually from healthy controls to gastric dysplasia, EGC, and AGC8. It revealed a statistically significant difference between patients with EGC and normal controls. Another study showed that ADAM9 mRNA expression was elevated in the peripheral blood of patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma compared to healthy controls9. A soluble form of MICA that was resulted by ADAM-mediated shedding was associated with prognosis of patients with gastric cancer; patients with gastric cancer having a higher level of soluble MICA had a lower survival rate10. Moreover, soluble MICA was significantly increased in patients with gastric cancer compared with healthy controls10.

Based on these previous studies, we postulated that ADAMs and MICA have potential as biomarkers for screening for gastric cancer. In this pilot study, we aimed to test this hypothesis. First, we characterized ADAM expression in gastric cancer by using bioinformatic techniques. Second, we validated the results by analyzing human blood samples. We hope the results of this study will provide a direction where the future investigations for biomarkers for early-stage cancers should be headed to.

Methods

Study design

This pilot study evaluated the association between ADAMs, MICA, and gastric cancer. In a previous study, ADAM9, ADAM10, and ADAM17 expression was increased in both primary cancer tissues and metastatic lymph node tissues of gastric cancer5. In another study, a soluble form of MICA was associated with the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer10. Thus, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM17, and MICA were chosen as study markers.

For the initial assessment of target markers, we performed an in-silico analysis using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Subsequently, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were performed on human blood samples.

After the initially planned study, we expanded the bioinformatic analyses to cover all ADAMs and NKG2DLs. In this process, we found that ADAM12 had statistical significance. Thus, we added ADAM12 as a target marker in the blood sample analysis. Also, we identified that ADAM8 had statistical significance. Thus, we included ADAM8 in the in-silico analysis, but did not include it in the blood sample analysis for there is already a study that investigated the association between serum ADAM8 protein and gastric cancer8.

In silico analysis with TCGA database

We downloaded the transcriptomic, survival, and clinical data of 415 patients with GC (indexed as STAD) from the Xena TCGA database hub (https://xenabrowser.net) generated by the University of North Carolina TCGA Genome Characterization Center. Transcriptomic data were acquired from 415 gastric cancer tissues indexed as primary tumors and 35 nearby normal tissues indexed as solid normal tissues.

Participants

This study was conducted at Seoul National University Hospital and Chaum Health Check-up Center between July 2021 and March 2023. Patients who recently received a diagnosis of gastric cancer at Seoul National University Hospital were included in the gastric cancer group. Gastric cancer was confirmed using endoscopic and histopathological examinations. Clinical stage was determined using endoscopic ultrasonography and computed tomography. For the control group, healthy individuals who were found to have no evidence of cancer during a health check-up at the Chaum Health Check-up Center were included. Written informed consent for enrollment was obtained. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB number: 2102-189-1203) and CHA Bundang Medical Center (IRB number: 2021-07-073). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Upon enrollment, 10 mL of peripheral blood was drawn to one SST bottle (BD Vacutainer®, 5 mL) and one EDTA bottle (BD Vacutainer®, 5 mL). The serum and plasma samples were stored at − 80 °C. The serum samples were used for protein quantification with ELISA, and the plasma samples were used for mRNA quantification for qRT-PCR.

Population size calculation

To calculate the required population size, we used a previous study that evaluated the association between ADAM8 protein and gastric cancer as a reference study8. As a primary endpoint, we aimed to find a marker that can distinguish EGC patients from healthy controls. Thus, we used the average value of serum ADAM8 protein in normal controls (1.7 ng/mL) and patients with EGC (53.9 ± 36.9 ng/mL). Using an alpha of 0.05, power of 80%, and enrollment ratio of 1, the population size (healthy controls: patients with EGC) of the training set was calculated to be 16 (8:8). Assuming that sample handling errors may occur in 20% of cases, the population size was determined to be 20 (10:10). If the training study yielded significant results, a validation study was planned to follow with a population size of 40 (20:20) was conducted. As a secondary endpoint, we aimed to determine the differences between patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC) and healthy controls. The population size for AGC was planned to be the same as that for EGC. The secondary endpoint study was terminated when the primary endpoint was met.

mRNA isolation and real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of the isolated RNA was assessed using a Nanodrop-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequently, 1 µg of RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the AccuPower CycleScript RT Premix (BIONEER, Daejeon, Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 Touch real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) using iQ™ SYBR Green Supermix (BIONEER). The specific primer sets used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The following PCR reactions were performed: initial denaturation (95 °C for 10 min) followed by 45 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 10 s) and annealing (55 °C for 30 s). The raw data obtained from qRT-PCR were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCt method, and the expression levels were normalized to the reference gene GAPDH as an endogenous internal control. All experiments were performed in duplicates.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ELISA kits were used for the detection of ADAM9 (Aviva Systems Biology, San Diego, CA, USA), ADAM10 (Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA), ADAM12 (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), ADAM17 (Novus Biologicals), and MICA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The absorbance was measured at an appropriate wavelength using a microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, Vermont, USA). Standard curves were generated using known concentrations of recombinant proteins to quantify the target protein levels in serum samples. All experiments were performed in duplicates.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between the groups was determined using Shapiro–Wilk test, Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, paired t-test, and analysis of variance (ANOVA). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses of TCGA dataset were performed using R software (https://www.r-project.org/, Version 4.3.1). The “ggplot2” package (Version 3.4.3) was used for data summary and analysis. For the evaluation of diagnostic performance, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to calculate the area under the curve (AUC). Graphs were generated using Graph pad Prism9 (Graph Software, La Jolla, California, USA).

Results

Part 1. ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in gastric cancer tissues from TCGA database

To evaluate the expression levels of ADAM and MICA mRNAs in gastric cancer tissues, we performed in-silico analyses of 415 gastric cancer tissues and 35 normal tissues from TCGA database.

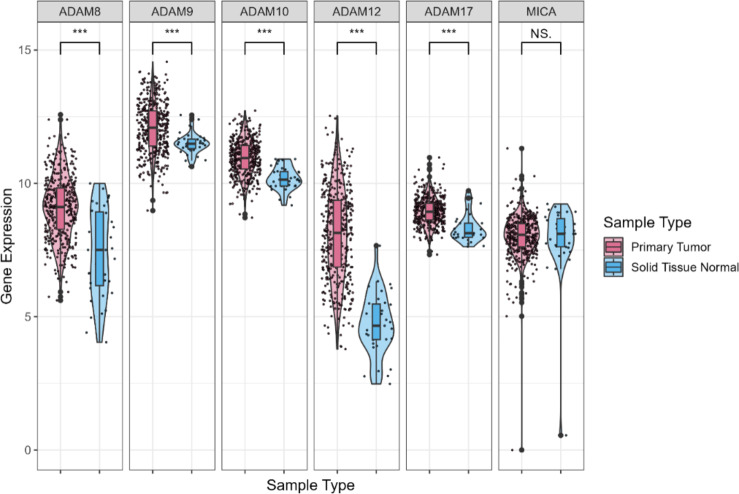

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in gastric cancer

Gastric cancer tissues (n = 415) expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 (p < 0.001) than normal tissues (n = 35) (Fig. 1). When gastric cancer tissue was paired with normal tissue from the same patient with gastric cancer (n = 32), ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 mRNAs showed significantly higher expression in gastric cancer tissues (p < 0.05) (Supplementary Figure S1).

Fig. 1.

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in gastric cancer tissues compared with normal tissues from TCGA database. Expression levels of ADAM and MICA mRNAs were compared in gastric cancer tissues (n = 415) and normal tissues (n = 35) via in silico analyses using TCGA database. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, NS. not specific; t-test.

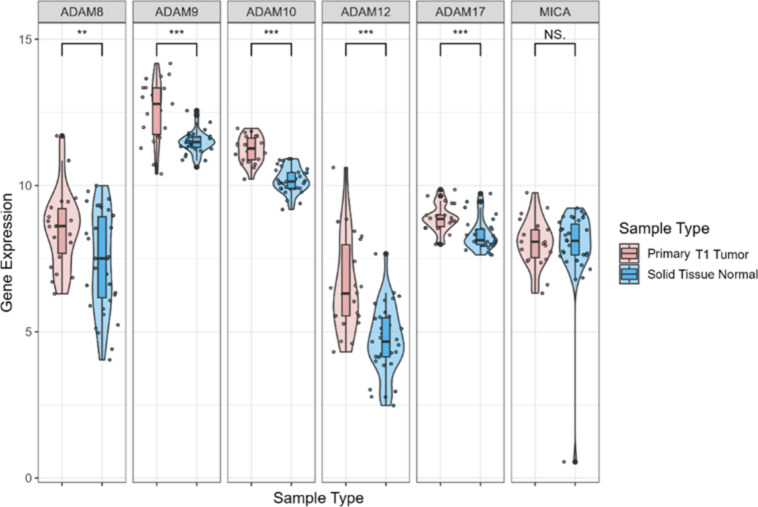

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in early gastric cancer

To determine whether the above association was observed in EGC, gastric cancer tissues from T1 stage tumors were grouped as EGC (n = 22) and compared with normal tissues (n = 35). EGC expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 than normal tissues (p < 0.005) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in early gastric cancer tissues compared with normal tissues from TCGA database. mRNA expression levels of ADAM and MICA were compared between gastric cancer tissues with T1 stage (n = 22) and normal tissues (n = 35) via in silico analyses using TCGA database. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, NS. not specific; t-test.

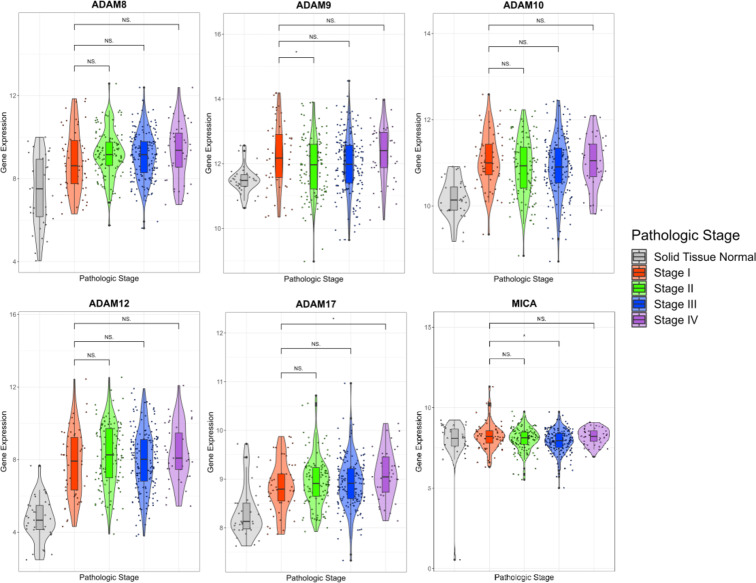

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression according to gastric cancer stage

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in normal (n = 35) and gastric cancer tissues according to gastric cancer stage (stage I, n = 57; stage II, n = 123; stage III, n = 171; stage IV, n = 41) is shown in Fig. 3. ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in each group of stage II, III and IV gastric cancer was compared with that in stage I gastric cancer group, one by one. A statistically significant difference (p < 0.05) without clinical significance was observed in a few parts of the analysis: ADAM17 between stages I and IV, ADAM9 between stages I and II, MICA between stages I and III.

Fig. 3.

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in normal and gastric cancer tissues according to gastric cancer stage in TCGA database. ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in normal (n = 35) and gastric cancer tissues according to gastric cancer stage groups (stage I, n = 57; stage II, n = 123; stage III, n = 171; stage IV, n = 41) is depicted. The difference of ADAM and MICA mRNA expression was compared between stage I gastric cancer group and other stage groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, NS. not specific; t-test.

Part 2. ADAM and MICA expression in the peripheral blood of patients with gastric cancer

Population characteristics

The characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. Eleven patients with EGC, 3 with AGC, and 12 healthy controls were enrolled in the training set. Among these, two EGC, one AGC, and two control samples were inadequate owing to hemolysis, coagulation, and insufficient amounts. Thus, nine patients with EGC, two patients with AGC, and ten healthy controls were included in the analysis. In the validation set, 20 patients with EGC, 5 patients with AGC, and 22 healthy controls were enrolled. Among them, two EGC samples and two control samples were inadequate. Thus, 18 patients with EGC, 5 patients with AGC, and 20 healthy controls were included in the analysis. Before we completed enrollment of patients with AGC, the primary endpoint was met; thus, further enrollment of patients with AGC was terminated. Sample handling errors occurred in two AGC serum samples in the training set and in two EGC and three control serum samples in the validation set.

Table 1.

Population characteristics.

| Training set | Validation set | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Early gastric cancer (n = 9) | Early gastric cancer (n = 18) | ||

| Men | 8 (88.9) | Men | 16 (88.9) |

| Age | 72.8 ± 7.14 | Age | 60.9 ± 11.6 |

| Histology | Histology | ||

| WD | 5 (55.6) | WD | 6 (33.3) |

| MD | 3 (33.3) | MD | 6 (33.3) |

| PD | 0 | PD | 1 (5.56) |

| SR | 1 (11.1) | SR | 5 (27.8) |

| Stage | Stage | ||

| cT1aN0 | 5 (55.6) | cT1aN0 | 7 (38.9) |

| cT1bN0 | 3 (33.3) | cT1bN0 | 11 (61.1) |

| Advanced gastric cancer (n = 2) | Advanced gastric cancer (n = 5) | ||

| Men | 2 (100) | Men | 3 (60) |

| Age | 74.5 ± 0.707 | Age | 58.8 ± 5.63 |

| Histology | Histology | ||

| WD | 0 | WD | 0 |

| MD | 1 (50) | MD | 2 (40) |

| PD | 1 (50) | PD | 1 (20) |

| SR | 0 | SR | 2 (40) |

| Stage | Stage | ||

| cT2N0 | 2 (100) | cT2N0 | 2 (40) |

| cT3N0 | 3 (60) | ||

| Control (n = 10) | Control (n = 20) | ||

| Men | 5 (50) | Men | 9 (45) |

| Age | 47.5 ± 8.53 | Age | 44.2 ± 10.8 |

Values are presented in number (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

WD well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, MD moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, PD poorly differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma, SR poorly cohesive carcinoma with signet ring cells.

Training set

In the mRNA quantification with the peripheral blood sample, patients with EGC expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM10 (p = 0.031), ADAM12 (p < 0.0001), ADAM17 (p = 0.0279) and MICA (p = 0.0334) than the healthy controls (Supplementary Figure S2). ADAM9 (p = 0.0789) mRNA level showed an increasing trend.

In protein quantification, ADAM17 (p = 0.084) protein showed an increasing trend in EGC compared to that in the controls (Supplementary Figure S3). ADAM9 protein was not detected. Therefore, further investigation of ADAM9 protein was terminated. ADAM12 protein had an outlier (3201.1 pg/mL) in the EGC group that was too high than that in the other EGC samples (0–490.1 pg/mL). The inclusion or exclusion of this sample did not affect statistical significance (p = 0.0204 and p = 0.039, respectively). Supplementary Figure S3 excludes this outlier value.

Validation set

In the mRNA quantification, patients with EGC expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM12 (p = 0.0023) and ADAM17 (p < 0.0001) than the controls (Supplementary Figure S4).

In protein quantification, ADAM10 (p < 0.001) protein was significantly increased in patients with EGC compared to that in the controls (Supplementary Figure S5). ADAM12 protein had an outlier (122201.9 pg/mL) in the control group that was too high than that in the other control samples (0-209.2 pg/mL). Including (p = 0.393) and excluding (p = 0.005) this sample had a statistically significant effect. Supplementary Figure S5 excludes this outlier value.

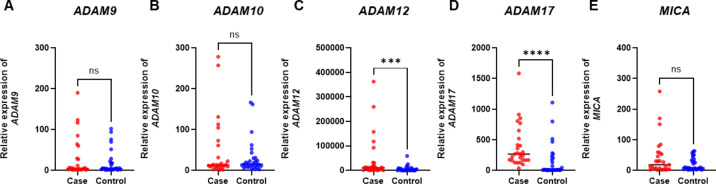

Combined analyses

When the training and validation sets were combined, there were 27 patients with EGC, 7 with AGC, and 30 controls. Analyses were performed on the combined population.

First, the EGC group was compared with the control group. In mRNA quantification, patients with EGC (n = 27) expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM12 (p = 0.0007) and ADAM17 (p < 0.0001) than the controls (n = 30) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

ADAM and MICA mRNA expression in the combined sets of plasma samples of patients with early gastric cancer and healthy controls. mRNA expression levels of (A) ADAM9 (p = 0.858), (B) ADAM10 (p = 0.803), (C) ADAM12 (p = 0.0007), (D) ADAM17 (p < 0.0001), and (E) MICA (p = 0.319) were examined using qPCR in plasma samples obtained from early gastric cancer (case, n = 27, shown in red) and healthy controls (control, n = 30, shown in blue). The data were normalized to an internal control (GAPDH) and presented as relative expression. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns. not specific; t-test or Mann–Whitney U test.

In protein quantification, ADAM10 (p < 0.001) protein was significantly increased in EGC samples (n = 25) compared to that in the controls (n = 26) (Fig. 5). For ADAM12 protein analysis, two outliers were excluded: one EGC sample from the training set and one control sample from the validation set. ADAM12 (p < 0.001) protein levels were significantly higher in patients with EGC (n = 24) than in healthy controls (n = 25). Figure 5 was drawn after excluding two outliers.

Fig. 5.

ADAM and MICA protein expression in the combined sets of serum samples of patients with early gastric cancer and healthy controls. Expression levels of (A) ADAM10 (p < 0.001), (B) ADAM12 (p < 0.001), (C) ADAM17 (p = 0.702), and (D) MICA (p = 0.812) were examined using ELISA in serum samples obtained from patients with early gastric cancer (case, n = 25 [n = 24 for ADAM12], shown in red) and healthy controls (control, n = 26 [n = 25 for ADAM12], shown in blue). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, ns. not specific; t-test or Mann–Whitney U test.

Second, the AGC group (n = 7) was compared with the control group (n = 30). In the mRNA quantification, patients with AGC (n = 7) expressed significantly higher mRNA levels of ADAM17 (p = 0.003) than the controls (n = 30) (Supplementary Figure S6).

The protein levels of ADAM10 (p = 0.006) and ADAM12 (p = 0.014) were significantly increased in patients with AGC (n = 5) than in controls (n = 26) (Supplementary Figure S7). For ADAM12 protein analysis, one outlier in the control sample was excluded (p = 0.751). The protein level of MICA (p = 0.042) was significantly decreased in patients with AGC than in controls (Supplementary Figure S7).

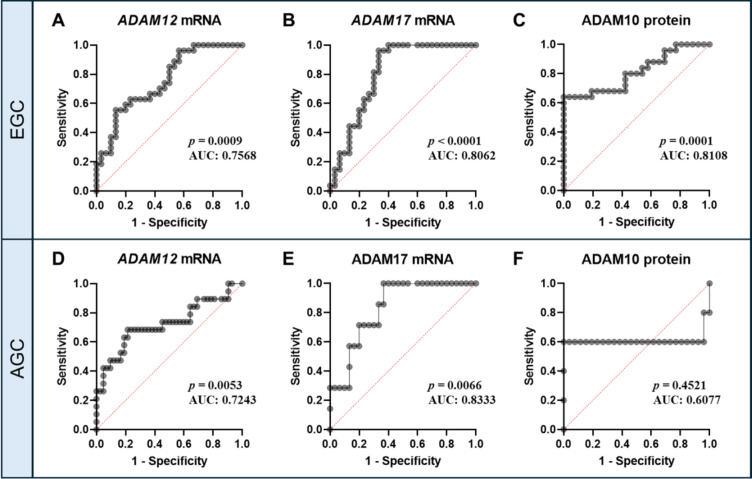

Diagnostic performance of ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein

Diagnostic performance of ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA in EGC (n = 27) and controls (n = 30) and ADAM10 protein in EGC (n = 25) and controls (n = 26) of the combined population was evaluated with ROC analysis. ADAM12 mRNA had an AUC of 0.7568 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.6334 to 0.8802; p = 0.0009), ADAM17 mRNA had an AUC of 0.8062 (95% CI: 0.6889 to 0.9234; p < 0.0001), and ADAM10 protein had an AUC of 0.8108 (95% CI: 0.6895 to 0.9320; p = 0.0001) (Fig. 6A, B, C). For the purpose of comparison, the diagnostic performance of ADAM12 and ADAM17 mRNA in AGC (n = 7) and controls (n = 30) and ADAM10 protein in AGC (n = 5) and controls (n = 26) was additionally presented in Fig. 6. ADAM12 mRNA had an AUC of 0.7243 (95%CI: 0.5716 to 0.8770; p = 0.0053), ADAM17 mRNA had an AUC of 0.8333 (95% CI: 0.6949 to 0.9718; p = 0.0066), and ADAM10 protein had an AUC of 0.6077 (95% CI: 0.1859 to 1.000; p = 0.4521) (Fig. 6D, E, F). Although the diagnostic performance decreased in AGC due to the small sample size, the trend is consistent with that in EGC.

Fig. 6.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and areas under the curves (AUC) of ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein for the prediction of early gastric cancer (EGC) and advanced gastric cancer (AGC) in the combined population. Panels (A)–(C) represent the analyses in the EGC, and (D)–(F) in the AGC. The combined population of training set and validation set for analyses of EGC comprised of EGC (n = 27) and controls (n = 30) for the mRNAs and EGC (n = 25) and controls (n = 26) for the protein. The combined population for analyses of AGC comprised of AGC (n = 7) and controls (n = 30) for the mRNAs and AGC (n = 5) and controls (n = 26) for the protein.

Discussion

This proof-of-concept study tested whether players in the ADAM-NKG2D axis have clinical applicability in gastric cancer diagnostics. In this study, we found that the mRNA expression levels of ADAM8, ADAM9, ADAM10, ADAM12, and ADAM17 were significantly higher in EGC tissues than in normal tissues. Among these, we found that ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein levels were significantly increased in the peripheral blood of patients with EGC compared to those in controls revealing fair performance. This result implies that ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein have potential as biomarkers for screening EGC.

The incidence of cancer is increasing with an aging population. The most effective cancer management strategies are early detection and complete excision. Health-checkups are useful for early detection but have shortcomings in terms of risks and expenses. There are multiple tumor markers, but only a few have proven useful in cancer screening11. Thus, most tumor markers are used to assess treatment response rather than to screen for cancer. Hence, the development of a safe, noninvasive method for checkups, such as blood tests for cancer screening, has been pursued11. A major hurdle in developing a cancer-screening biomarker is finding a marker with sufficient power to detect cancer at an early stage.

To solve the problem of detecting early-stage cancers, liquid biopsy is under investigation. Liquid biopsy examines cancer-derived materials such as circulating tumor cells, exosomes, extracellular vesicles, and cell-free nucleic acids12. In addition, algorithmic analysis of cancer risk with a composite of various markers are being investigated. For example, CancerSEEK calculated the risks of eight cancers using 16 circulating tumor DNAs and eight proteins13. Circulating tumor DNAs are not easily detected in early-stage cancers14,15. To address this problem of detecting early-stage cancers, the authors commented that protein markers were added13. The CancerSEEK could detect cancers of the ovary, liver, stomach, pancreas, esophagus, colorectum, lung, and breast with a sensitivity of 70%. Although CancerSEEK has achieved significant advancements in cancer diagnostics, the detection of early-stage cancers remains a limitation. This limitation highlights the importance of ongoing research in the development of novel biomarkers.

Therefore, the use of ADAMs warrants further investigation. The ADAM family belongs to the superfamily of zinc-dependent metalloproteinases, and are expressed in various tissues in body16. Currently, 22 ADAM members were discovered in humans17. Among those, 12 ADAMs (ADAM8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 17, 19, 20, 21, 28, 30, and 33) are proteolytically active containing the catalytic metalloproteinase domain17–19. ADAMs are often called as a sheddase involved in ectodomain shedding. They proteolytically cleave membrane-bound proteins such as cytokines, growth factors, receptors, ligands and cell adhesion molecules, which result in important biological processes such as cell signaling, cell adhesion, migration, proteolysis, and tissue remodeling17,20. It is known that ADAM-mediated shedding can be constitutive or induced by signaling through G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) activators, protein kinase C (PKC) activators, calcium ionophores, and others20. The normal function of ADAMs is best demonstrated in knockout studies. ADAM knockout in mice resulted in infertility, developmental failure of heart and nervous system, muscle defect, and so on20. For instance, apical surface of uterine epithelium is covered by mucins. A transmembrane mucin MUC1 exerts anti-adhesive effect thus serving as a physical barrier against microbial attack, but this barrier needs to be overcome when the time of blastocyst attachment comes. There is evidence that ADAMs, especially ADAM17, take part in the process of clearing of MUC1 by shedding it locally on the uterine epithelium to facilitate embryo implantation17,21,22.

On the other hand, dysregulation of ADAMs are involved in several pathologic processes such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, asthma and Alzheimer’s disease20. Especially, ADAMs are closely linked to cancer development and metastasis16,19. Overexpression of ADAMs was observed in many cancers23–28, and higher expression was associated with poor prognosis23,25,29–31. Knocking-down ADAMs reduced cancer cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and tumor growth in vivo32–34. Furthermore, knocking-down ADAMs increased chemosensitivity and radiosensitivity of cancer cells35–37. Inhibiting ADAMs with specific molecules such as monoclonal antibody reduced tumor growth, increased chemosensitivity, and decreased shedding of NKG2DL leading to enhanced immune recognition by NK cells38–40. These observations support the idea that ADAMs may serve as diagnostic and therapeutic targets for cancer.

In the current study, we identified ADAM10, ADAM12 and ADAM17 simultaneously as potential biomarkers for gastric cancer diagnosis. This finding is consistent with the findings of other studies showing that the expression of ADAM10, ADAM12 and ADAM17 is increased in gastric cancer tissues, and that increased expression of those in gastric cancer tissues is associated with poor survival in patients with gastric cancer5,41–46. ADAM10, ADAM12 and ADAM17 are known to have very similar sequences and crystal structures17,47,48. Consequently, they have similar functions sharing some substrates such as pro-heparin binding (HB)-epidermal growth factor (EGF)17,47.

ADAM10 and ADAM17 were often studied together having the greatest number of substrates and shared substrates among ADAM members17. The expression of ADAM10 and ADAM17 was increased in biopsy specimens of non-cancerous gastric mucosa infected with Helicobacter pylori, the well-known carcinogen for gastric cancer, compared to those in specimens not infected42. When gastric epithelial cells were infected with H. pylori, ADAM10 and ADAM17 mRNA expression demonstrated a temporal increase42. In addition, ADAM10 and ADAM17 expression upon H. pylori infection may explain the paradox that higher expression of MUC1, a protective barrier on the gastric mucosa against H. pylori attachment49, is actually associated with poor prognosis of gastric cancer50. That is, ADAM17 mediated MUC1 shedding induced by H. pylori infection may have caused increased expression of MUC1 as a coping mechanism although it failed to prevent gastric cancer development. Another study demonstrated that H. pylori infection of gastric epithelial cells caused phosphorylation of ADAM17 C-terminal potentiating the cleavage function of ADAM17 to the extent that shedding of HB-EGF could lead to EGF receptor transactivation51. These findings indicate that gastric carcinogenesis caused by chronic infection with H. pylori is mediated by aberrant expression of ADAM10 and ADAM17.

There are other ways in which ADAM10 and ADAM17 participate in gastric cancer development via various signaling pathways. Neurogenic locus notch homolog (Notch) and Wingless-related integration site (Wnt) signaling pathways had positive correlation with ADAM17 expression in gastric cancer5. Erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular (Eph) receptor type A8 (EphA8) expression was associated with poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer, and its knockdown decreased the expression of ADAM10, indicating that EphA8 is an upstream regulator of ADAM1052. In gastric cancer cells, IL-8 induced shedding of EGFR ligands to lead to EGFR transactivation in a pathway that is dependent on ADAM10 but not on ADAM12 or ADAM1753. Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 16 (CXCL16) and C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 6 (CXCR6) axis that activate protein kinase B (Akt) and MAPK signaling pathways in gastric carcinogenesis was dependent on ADAM1054. Micro RNAs are also involved in gastric cancer development by influencing ADAM10 or ADAM17. The expression levels of miR-448 and miR-320a were negatively correlated with those of ADAM10 in gastric cancer tissues, and overexpression of these miRNAs suppressed gastric cancer cell proliferation, colony formation, and invasion55,56. Overexpression of miR-338-3p, which is regulated by the circular RNA circ_0051620, inhibited gastric cancer cell migration and invasion by inhibiting ADAM1757,58.

Compared to ADAM10 and ADAM17, the role of ADAM12 in relation to gastric cancer development is relatively less studied. There is evidence that ADAM12 is involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis44. A study suggested that ADAM12 facilitate tumor progression by promoting metastasis and immune infiltration in gastric cancer by showing that genes involved with extracellular matrix and tumor microenvironment were associated with ADAM12 in gene enrichment analyses59. Also, a proteomic study revealed that ADAM12S, a secreted form of ADAM12, promotes migration of gastric cancer cells by upregulating CD146, a cell adhesion molecule dependent on the catalytic residue of ADAM12S60. In terms of micro RNA, one study showed that miR-30c-5p was downregulated while its target, ADAM12, was upregulated in gastric cancer tissues61. Although the mechanistic role of ADAM12 in gastric carcinogenesis has not been sufficiently elucidated yet, there were already two studies demonstrating that ADAM12 was increased in the urine samples of gastric cancer patients compared to controls suggesting that urinary ADAM12 holds potential as a biomarker for gastric cancer62,63. On the other hand, ADAM12 may play a crucial role in relation to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) in gastric cancer. Overexpression of HER2 is involved in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer, and HER2 positivity ranges from 6.0 to 29.5% in gastric cancer64. A study in head and neck cancer cells demonstrated that ADAM12 increased HER2 expression, HER2 inhibition decreased ADAM12 expression, and HER2 transfection increased ADAM12 expression suggesting there is a positive feedback loop between those two65.

Above studies support that ADAM12, ADAM17 and ADAM10 hold potential as biomarkers for gastric cancer. We specifically demonstrated their potential in screening EGC. In general, it is easier to demonstrate significant differences between patients with advanced cancer and healthy controls. However, demonstrating the differences between early-stage cancer and healthy controls is a challenging task. Thus, demonstrating significant difference of the above study markers between EGC and healthy controls is a great achievement of this study.

This study had some limitations. First of all, the sample size was very small. We calculated population size based on a reference study which evaluated the association between ADAM8 protein and gastric cancer. Since its outcome was remarkable from the training set, the population size was calculated quite small as was described in the methods. We think inconsistency between the training set and validation set, which happened in ADAM10, was caused by the small sample size. Secondly, age and sex matching could not be done in this study. Planning a pilot-study like a sieve to test the potential of 10 markers altogether, we forwent the matching but enrolled participants who were willing to donate blood samples for the study. As a matter of fact, it was quite difficult to find participants because blood draw was bothersome for the participants, and younger people were more willing to donate blood samples in patients and controls alike. Thirdly, it was unfortunate that we were unable to enroll many patients with AGC. In Korea, the detection rate of AGC has significantly dropped over the last decade thanks to national cancer screening program. Most of the patients with gastric cancer are being detected at an early stage. Thus, before enrolling patients with AGC up to the initially planned number, we observed statistical significance in patients with EGC meeting the primary endpoint. Therefore, we stopped enrolling patients further. Although we could not compare healthy controls and patients with EGC and AGC in sufficiently large numbers, the analyses with TCGA data indirectly indicated that the difference between early and advanced stages may not be too large. Additionally, we did not include ADAM12 protein as a main finding of this study because ADAM12 protein had a few outliers. However, we see that ADAM12 also holds potential and is worth further study for many biomarkers in real-world also have outliers of sometimes unknown reasons. Lastly, we suggest that future studies be designed in a larger population with age and sex matching and be followed longitudinally to better characterize the study markers.

Conclusion

In summary, we hypothesized that players in the ADAM-NKG2D axis, the less investigated targets, may have a role in gastric cancer diagnostics. Investigations first with bioinformatic analyses and second with human blood samples revealed that ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein have a potential as biomarkers for screening EGC. This finding is particularly encouraging in that finding a biomarker with sufficient power to detect cancer at an early stage has been a substantial challenge to researchers. We believe that ADAM12, ADAM17 mRNA and ADAM10 protein are worth further investigation as biomarkers for gastric cancer screening, and that players in the ADAM-NKG2D axis are worth investigation for cancer diagnostics and therapeutics.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. 2020R1F1A107714812).

Author contributions

S.O., KB.K., S.G.K.: planned, designed, and directed the study. S.-S.L., S.-H.C.; handled human blood samples, performed experiments, and insured quality control. H.J.: performed in-silico analyses.: KB. K.: supervised experiments and in-silico analyses. C.-K.C, S.-W.C., S.G.K: helped human blood sample acquirement and supervised human study. S.O., S.-S.L., H.J.: analyzed data. S.O., J.L., KB.K., S.G.K: interpreted the results. All authors participated in preparing the manuscript.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sooyeon Oh, Sang-Soo Lee, Hoeyoung Jin, KyuBum Kwack and Sang Gyun Kim contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

KyuBum Kwack, Email: kbkwack@cha.ac.kr.

Sang Gyun Kim, Email: harley@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattiuzzi, C. & Lippi, G. Current Cancer epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Glob Health. 9, 217–222. 10.2991/jegh.k.191008.001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu, J. et al. The Comparison between Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection and Surgery in Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract 4378945, (2018). 10.1155/2018/4378945 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Zingoni, A., Vulpis, E., Loconte, L. & Santoni, A. NKG2D ligand shedding in response to stress: role of ADAM10. Front. Immunol.11, 447. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00447 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, W. et al. ADAM17 promotes lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer via activation of the notch and wnt signaling pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med.43, 914–926. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.4028 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, J. M. et al. The effect of disintegrin-metalloproteinase ADAM9 in gastric cancer progression. Mol. Cancer Ther.13, 3074–3085. 10.1158/1535-7163.mct-13-1001 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu, Q. et al. MiR-129-5p functions as a tumor suppressor in gastric cancer progression through targeting ADAM9. Biomed. Pharmacother. 105, 420–427. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.05.105 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung, H. W., Kim, J. J., Choi, J. I., Lee, H. R. & Lim, J. B. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 8 as a potential blood biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric Cancer. Yonsei Med. J.60, 713–719. 10.3349/ymj.2019.60.8.713 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh, S. et al. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 9 (ADAM9) in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma and their role as a Biomarker during Hepatocellular Carcinoma Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 12, 745. 10.3390/cancers12030745 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao, P., Chen, D. & Cheng, H. Prognostic significance of soluble major histocompatibility complex class I-related chain A (sMICA) in gastric cancer. Br. J. Biomed. Sci.75, 203–205. 10.1080/09674845.2018.1505188 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herrlich, P. & Herrlich, A. A. D. A. M. Metalloprotease-released Cancer biomarkers. Trends Cancer. 3, 482–490. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.05.001 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nikanjam, M., Kato, S. & Kurzrock, R. Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. J. Hematol. Oncol.15, 131. 10.1186/s13045-022-01351-y (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen, J. D. et al. Detection and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science359, 926–930. 10.1126/science.aar3247 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettegowda, C. et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl Med.6, 224ra224. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007094 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen, J. D. et al. Combined circulating tumor DNA and protein biomarker-based liquid biopsy for the earlier detection of pancreatic cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, 10202–10207. 10.1073/pnas.1704961114 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocks, N. et al. Emerging roles of ADAM and ADAMTS metalloproteinases in cancer. Biochimie90, 369–379. 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.08.008 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong, S. & Khalil, R. A. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) and ADAM with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS) family in vascular biology and disease. Biochem. Pharmacol.164, 188–204. 10.1016/j.bcp.2019.03.033 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda, S. A. D. A. M. & Family Proteins, A. D. A. M. T. S. Snake Venom metalloproteinases: a structural overview. Toxins (Basel). 8. 10.3390/toxins8050155 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mochizuki, S. & Okada, Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Sci.98, 621–628. 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00434.x (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards, D. R., Handsley, M. M. & Pennington, C. J. The ADAM metalloproteinases. Mol. Aspects Med.29, 258–289. 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.001 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thathiah, A., Blobel, C. P. & Carson, D. D. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme/ADAM 17 mediates MUC1 shedding. J. Biol. Chem.278, 3386–3394. 10.1074/jbc.M208326200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olson, G. E., Winfrey, V. P., Matrisian, P. E., NagDas, S. K. & Hoffman, L. H. Blastocyst-dependent upregulation of metalloproteinase/disintegrin MDC9 expression in rabbit endometrium. Cell. Tissue Res.293, 489–498. 10.1007/s004410051141 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, H. B. et al. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 mRNA and protein expression in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, as well as its clinicopathological factors and prognosis. Mol. Med. Rep.11, 961–967. 10.3892/mmr.2014.2802 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li, H., Duhachek-Muggy, S., Dubnicka, S. & Zolkiewska, A. Metalloproteinase-disintegrin ADAM12 is associated with a breast tumor-initiating cell phenotype. Breast Cancer Res. Treat.139, 691–703. 10.1007/s10549-013-2602-2 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mino, N. et al. A disintegrin and metalloprotease 12 (ADAM12) is a prognostic factor in resected pathological stage I lung adenocarcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol.100, 267–272. 10.1002/jso.21313 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walkiewicz, K. et al. Expression of Migration-Related Genes in Human Colorectal Cancer and Activity of a Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase 17. Biomed Res Int 8208904, (2016). 10.1155/2016/8208904 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Ringel, J. et al. Aberrant expression of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17/tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme increases the malignant potential in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res.66, 9045–9053. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-05-3287 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bilgin Doğru, E. et al. EMMPRIN and ADAM12 in prostate cancer: preliminary results of a prospective study. Tumour Biol.35, 11647–11653. 10.1007/s13277-014-2514-8 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burdelski, C. et al. Overexpression of the A disintegrin and metalloproteinase ADAM15 is linked to a small but highly aggressive subset of prostate cancers. Neoplasia19, 279–287. 10.1016/j.neo.2017.01.005 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakoda, T. et al. Impact of disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 12 on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma treated with surgical resection and perioperative chemotherapy. Pancreatology22, 479–487. 10.1016/j.pan.2022.03.018 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuefer, R. et al. ADAM15 disintegrin is associated with aggressive prostate and breast cancer disease. Neoplasia8, 319–329. 10.1593/neo.05682 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moriwaki, M. et al. Relevance of A Disintegrin and Metalloproteinase Domain-Containing (ADAM)9 Protein Expression to Bladder Cancer Malignancy. Biomolecules 12, (2022). 10.3390/biom12060791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Buranaphatthana, W. et al. Involvement of the A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 9 in oral cancer cell invasion. Eur. J. Oral Sci.129, e12775. 10.1111/eos.12775 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang, L., Gong, F. & Cui, Y. RNAi-mediated a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 9 gene silencing inhibits the tumor growth of non-small lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. Rep.12, 1197–1204. 10.3892/mmr.2015.3477 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, R. et al. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain 17 regulates colorectal Cancer stem cells and Chemosensitivity Via Notch1 signaling. Stem Cells Transl Med.5, 331–338. 10.5966/sctm.2015-0168 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song, P. et al. Knockdown of circ-ADAM9 inhibits malignant phenotype and enhances radiosensitivity in breast cancer cells via acting as a sponge for miR-383-5p. Strahlenther Onkol. 199, 78–89. 10.1007/s00066-022-02006-0 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang, J. T. et al. ADAM17 confers Temozolomide Resistance in Human Glioblastoma cells and miR-145 regulates its expression. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2410.3390/ijms24097703 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Huang, Y. K. et al. Inhibition of ADAM9 promotes the selective degradation of KRAS and sensitizes pancreatic cancers to chemotherapy. Nat. Cancer. 5, 400–419. 10.1038/s43018-023-00720-x (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulstrode, H. et al. A-Disintegrin and metalloprotease (ADAM) 10 and 17 promote self-renewal of brain tumor sphere forming cells. Cancer Lett.326, 79–87. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.07.022 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolpert, F., Tritschler, I., Steinle, A., Weller, M. & Eisele, G. A disintegrin and metalloproteinases 10 and 17 modulate the immunogenicity of glioblastoma-initiating cells. Neuro Oncol.16, 382–391. 10.1093/neuonc/not232 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fang, W., Qian, J., Wu, Q., Chen, Y. & Yu, G. ADAM-17 expression is enhanced by FoxM1 and is a poor prognostic sign in gastric carcinoma. J. Surg. Res.220, 223–233. 10.1016/j.jss.2017.06.032 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshimura, T. et al. ADAMs (a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) messenger RNA expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected, normal, and neoplastic gastric mucosa. J. Infect. Dis.185, 332–340. 10.1086/338191 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung, M. W., Park, Y. L., Park, S. Y. & Joo, Y. E. Expression of ADAM12 in gastric Cancer and its relation to Tumor Cell Behavior and Prognosis. Vivo36, 2194–2204. 10.21873/invivo.12945 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu, H. et al. Elevation of ADAM12 facilitates tumor progression by enhancing metastasis and immune infiltration in gastric cancer. Int. J. Oncol.6010.3892/ijo.2022.5341 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Wang, Y. Y. et al. ADAM 10 is associated with gastric cancer progression and prognosis of patients. J. Surg. Oncol.103, 116–123. 10.1002/jso.21781 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ni, P. et al. Prognostic significance of ADAM17 for gastric Cancer survival: a Meta-analysis. Med. (Kaunas). 5610.3390/medicina56070322 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Werny, L. et al. MT1-MMP and ADAM10/17 exhibit a remarkable overlap of shedding properties. FEBS J.290, 93–111. 10.1111/febs.16586 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nyren-Erickson, E. K., Jones, J. M., Srivastava, D. K. & Mallik, S. A disintegrin and metalloproteinase-12 (ADAM12): function, roles in disease progression, and clinical implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1830, 4445–4455. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.05.011 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sheng, Y. H. et al. Influence of the MUC1 cell surface mucin on gastric mucosal gene expression profiles in response to Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.10, 343. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00343 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim, Y. I. et al. MUC1 expressions and its prognostic values in US gastric Cancer patients. Cancers (Basel). 1510.3390/cancers15040998 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.McClurg, U. L. et al. Epithelial cell ADAM17 activation by Helicobacter pylori: role of ADAM17 C-terminus and Threonine-735 phosphorylation. Microbes Infect.17, 205–214. 10.1016/j.micinf.2014.11.011 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, Y. et al. EphA8 acts as an oncogene and contributes to poor prognosis in gastric cancer via regulation of ADAM10. J. Cell. Physiol.234, 20408–20419. 10.1002/jcp.28642 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tanida, S. et al. The mechanism of cleavage of EGFR ligands induced by inflammatory cytokines in gastric cancer cells. Gastroenterology127, 559–569. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.017 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han, J. et al. CXCL16 promotes gastric Cancer Tumorigenesis via ADAM10-Dependent CXCL16/CXCR6 Axis and activates akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Int. J. Biol. Sci.17, 2841–2852. 10.7150/ijbs.57826 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu, X. et al. miR-448 suppressed gastric cancer proliferation and invasion by regulating ADAM10. Tumour Biol.37, 10545–10551. 10.1007/s13277-016-4942-0 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ge, X. et al. miR-320a modulates cell growth and chemosensitivity via regulating ADAM10 in gastric cancer. Mol. Med. Rep.16, 9664–9670. 10.3892/mmr.2017.7819 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.AmeliMojarad, M., AmeliMojarad, M., Pourmahdian, A. & Circular RNA circ_0051620 sponges mir-338-3p and regulates ADAM17 to promote the gastric cancer progression. Pathol. Res. Pract.233, 153887. 10.1016/j.prp.2022.153887 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen, J. T. et al. MiR-338-3p inhibits the proliferation and migration of gastric cancer cells by targeting ADAM17. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.8, 10922–10928 (2015). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao, Y. et al. A new strategy to identify ADAM12 and PDGFRB as a novel prognostic biomarker for matrine regulates gastric cancer via high throughput chip mining and computational verification. Comput. Biol. Med.166, 107562. 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107562 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang, Z. et al. Proteomics and biochemical analyses of secreted proteins revealed a Novel mechanism by which ADAM12S regulates the Migration of Gastric Cancer cells. J. Proteome Res.21, 2160–2172. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00221 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu, S. et al. Effects and prognostic values of miR-30c-5p target genes in gastric cancer via a comprehensive analysis using bioinformatics. Sci. Rep.11, 20584. 10.1038/s41598-021-00043-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimura, T. et al. Novel urinary protein biomarker panel for early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 123, 1656–1664. 10.1038/s41416-020-01063-5 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimura, T. et al. Urinary ADAM12 and MMP-9/NGAL complex detect the presence of gastric cancer. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila). 8, 240–248. 10.1158/1940-6207.capr-14-0229 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boku, N. HER2-positive gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 17, 1–12. 10.1007/s10120-013-0252-z (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rao, V. H. et al. A positive feedback loop between HER2 and ADAM12 in human head and neck cancer cells increases migration and invasion. Oncogene31, 2888–2898. 10.1038/onc.2011.460 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.