Abstract

In recent years, large amounts of researches showed that pulmonary embolism (PE) has become a common disease, and PE remains a clinical challenge because of its high mortality, high disability, high missed and high misdiagnosed rates. To address this, we employed an artificial intelligence–based machine learning algorithm (MLA) to construct a robust predictive model for PE. We retrospectively analyzed 1480 suspected PE patients hospitalized in West China Hospital of Sichuan University between May 2015 and April 2020. 126 features were screened and diverse MLAs were utilized to craft predictive models for PE. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves (AUC) were used to evaluate their performance and SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values were utilized to elucidate the prediction model. Regarding the efficacy of the single model that most accurately predicted the outcome, RF demonstrated the highest efficacy in predicting outcomes, with an AUC of 0.776 (95% CI 0.774–0.778). The SHAP summary plot delineated the positive and negative effects of features attributed to the RF prediction model, including D-dimer, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrin and fibrinogen degradation products (FFDP), platelet count, albumin, cholesterol, and sodium. Furthermore, the SHAP dependence plot illustrated the impact of individual features on the RF prediction model. Finally, the MLA based PE predicting model was designed as a web page that can be applied to the platform of clinical management. In this study, PE prediction model was successfully established and designed as a web page, facilitating the optimization of early diagnosis and timely treatment strategies to enhance PE patient outcomes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-75435-9.

Keywords: Pulmonary embolism, Machine learning algorithms, Prediction model, SHAP value

Subject terms: Vascular diseases, Respiratory tract diseases, Machine learning, Software

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism (PE) represents a critical pulmonary circulatory disorder resulting from blockages in the pulmonary artery trunk or its branches, posing a significant threat to personal health. Manifesting with either subtle clinical symptoms or atypical features, PE often leads to missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis, causing patients to delay treatment and exacerbate disease progression1–3. A North American study reported a detection rate for PE of less than 5%4. At present, computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) stands as the primary clinical diagnostic method for PE. However, its application may yield adverse effects, particularly renal function impairment in patients with a history of renal disease or allergies5,6. In addition, CTPA is time-consuming, expensive, and inaccessible in certain conditions especially grassroots healthcare units. Therefore, establishing an efficient predictive model to identify high-risk PE patients before the onset of clinical event is imperative and impactful.

The concept of “medical engineering integration” advocates for the amalgamation and application of medicine, engineering, and biology, leveraging the complementary strengths of diverse disciplines. Machine learning, a methodology enabling computer systems to execute specific tasks through pattern recognition and reasoning rather than explicit instructions, has significantly contributed to this integration by studying algorithms and statistical models7. Machine learning spans diverse algorithms, encompassing supervised techniques like support vector machines (SVM), Bayesian learning, decision trees, regressions, as well as unsupervised methods such as k-means clustering, reinforcement learning (e.g., Q-learning), and specialized models like neural networks8,9. In the realm of disease risk prediction, the prevalent approach involves framing risk assessment as a statistical classification problem and leveraging pertinent models for resolution. Notably, SVM, neural networks, random forests (RF), and naive Bayes emerge as commonly utilized algorithms in disease risk prediction, recognized for their efficacy based on literature reviews, practical applications, and methodological characteristics10.

The synergy between machine learning and medicine has revolutionized disease prevention and treatment11. Notably, the China PAR model evaluates both 10-year and lifelong risks of cardiovascular diseases, which provides a practical assessment tool for primary cardiovascular disease prevention in China12. As for PE Predicting, previous work focused on the capability of MLA in aiding interpret radiology results to increase the accuracy and timeliness of PE diagnosis13–15. However, these models were limited to patients who had already undergone a formal diagnostic workup for PE. Therefore, in this study we intend to study suspected patients at risk of PE and apply diverse MLAs to analyze PE-associated variables including demographic profiles, clinical status, laboratory findings, and imaging characteristics, aiming to construct an optimal predictive model and verify its predictive capacity through Shapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) values, which not only helps to improve the clinical management of PE patients, but also decreases the unnecessary CTPA.

Methods

Data collection and processing of data

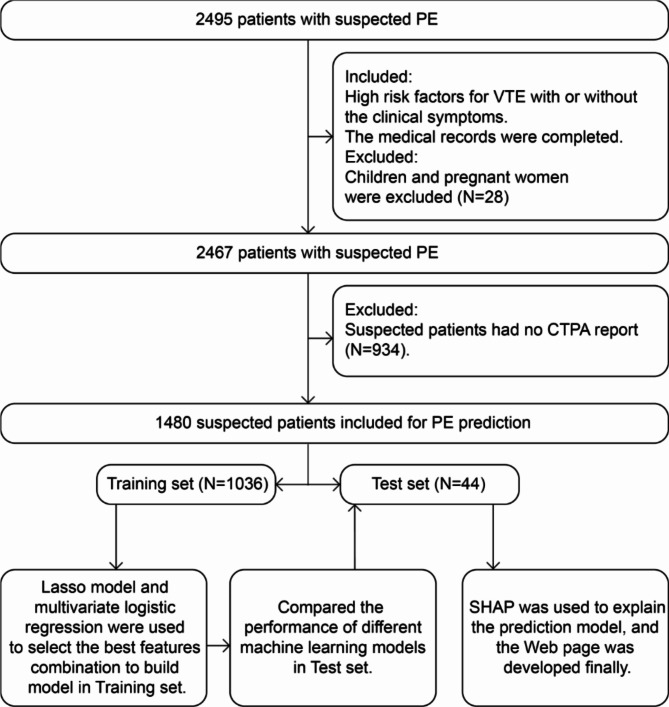

According to included criteria (1.High risk factors for venous thromboembolism (VTE), with or without the clinical symptoms; 2.The medical records were complete.) and excluded criteria (1.Children under the age of 18 and pregnant women were excluded, N = 28; 2.CTPA reports were not available, N = 934; 3.CTPA did not clearly diagnose, N = 53.), we conducted a retrospective review of medical records pertaining to 1480 hospitalized individuals at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between May 2015 and April 2020. 1480 suspected PE patients progressed to the subsequent phase. Among these, 70% (n = 1036) were allocated to the training set, while the remaining 30% (n = 444) comprised the test set for PE prediction. Comprehensive data encompassing demographic profiles, clinical status, laboratory findings, and imaging characteristics were collected, and 126 features were screened into the next step. To construct the PE prediction model, we employed the Lasso model and multivariate logistic regression techniques to discern the most optimal combination of features in the training set. Finally, we evaluated the performances of MLAs by AUC in the test set and elucidated the optimal prediction model by SHAP values (shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the patient selection and data processing.

Machine learning

The MLAs used in this study specifically included logistic regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), multilayer perceptron (MLP), random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) and light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM). We assessed the predictive performance according to the AUC. To ensure the robustness and reliability of the results, bootstrap methods with 1,000 bootstrap replicates were used to the derive 95% confidence interval (CI). Further, we used SHAP summary plot to delineate the positive or negative effects of the top features in the prediction model, and used SHAP dependence plot to explain how a single feature affects the output of the prediction model16. Finally, we developed a clinical web interface for pulmonary embolism prediction (https://xingyu87.pythonanywhere.com/). This platform allows for the determination of pulmonary embolism probability by inputting specific variable values. Notably, it visually showcases the SHAP values, providing insight into each variable’s contribution to pulmonary embolism prediction.

Statistics

Continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while non-normal variables were reported as median (Q1, Q3). Categorical data were described as numbers (n) and percentages (%). Statistical analyses included Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test was employed for comparisons involving categorical data. Significance was determined at p-values < 0.05.

Results

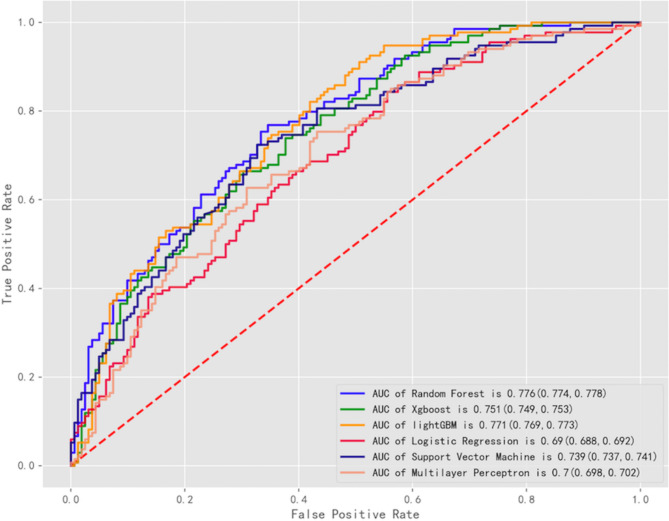

We conducted a retrospective analysis involving 1480 hospitalized suspected PE patients at West China Hospital of Sichuan University from May 2015 to April 2020. Demographic and clinical variables were listed in Table S1. Differences between the training and test sets were non-significant for all variables (shown in Table S2). All data during hospitalization were analyzed by Lasso model, and features selected by Lasso were presented as Figure S1. By combining multivariate logistic regression with clinical practice, seven variables emerged as significant predictors of PE : D-dimer, activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), fibrin and fibrinogen degradation products (FFDP), platelet count, albumin, cholesterol, and sodium (shown in Table S3). Utilizing these selected features as input variables, we constructed diverse machine learning algorithm (MLA) models, including LR, SVM, MLP, RF, XGBoost and LightGBM, and employed GridSearch along with 5-fold cross-validation for model training and evaluation (shown in Table S4). Among these, RF demonstrated the highest efficacy in outcome prediction, exhibiting the largest AUC of 0.776 (95% CI 0.774–0.778) as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of AUCs among machine learning models.

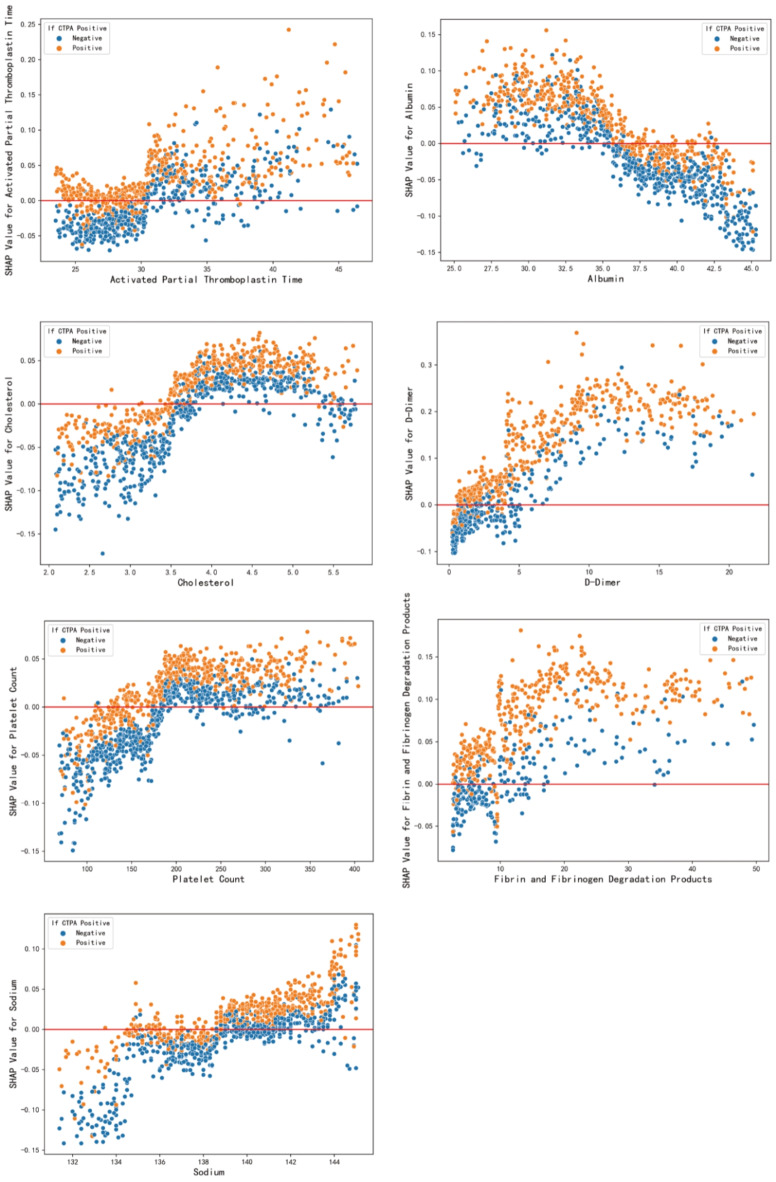

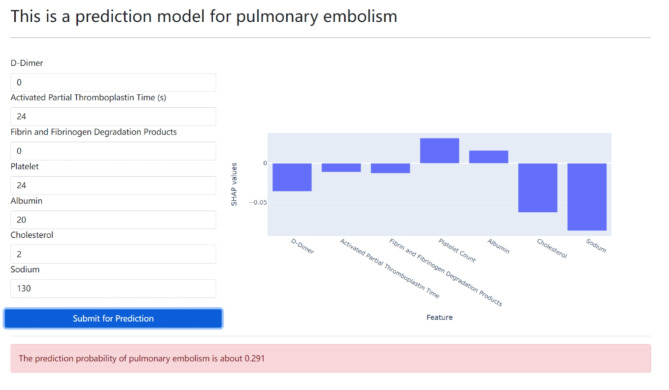

The SHAP summary plot of the RF model was presented in Fig. 3, which illustrates how higher SHAP values for specific features corresponded to an increased likelihood of PE development. Each patient had a dot assigned on the line for every feature, color-coded according to their respective feature values. These dots stacked vertically to illustrate density, with red denoting higher values and blue indicating lower values. To elucidate how individual feature influences the RF prediction model’s output, the SHAP dependence plot was displayed in Fig. 4. The y-axis represents specific feature SHAP values, with values exceeding zero indicating a higher probability of PE. Finally, we developed an online decision-support tool available on https://xingyu87.pythonanywhere.com/ (shown in Fig. 5 and Supplementary video), and the risk index of PE will be generated automatically after entering specific values of patients.

Fig. 3.

SHAP summary plot of the RF model.

Fig. 4.

SHAP dependence plot of the RF model.

Fig. 5.

Web page of pulmonary embolism prediction.

Discussions

Acute pulmonary embolism (PE) stands as the third leading cause of cardiovascular death globally, following coronary heart disease and stroke. Statistics indicate that the short-term mortality rate for untreated PE reaches as high as 30%17,18. Given PE potential to swiftly become life-threatening, early detection or advanced prediction plays a pivotal role in optimizing care, particularly for patients with complication such as cancer19,20. In this study, we demonstrated the efficacy of machine learning models in preemptively identifying patients at high risk of experiencing PE before its occurrence.

Through constructing predictive models using diverse MLAs, we observed that RF exhibited superior performance in PE prediction. RF consists of numerous random decision trees, utilizing random sample from the original data and subsets of features to develop the model. Each tree provides a classification, essentially ‘voting’ for a particular class. The collective outcome of these trees determines the forest’s classification, ensuring RF maintains consistent and stable performance levels21,22. Compared with previous research associated with machine leaning-based PE prediction23,24, the scope of research population in our study was much broader, including a variety of factors that contribute to the risk of VTE. Additionally, we utilized more features to build different machine learning models, which makes our prediction results more reliable and accurate.

More importantly, to date, there is no literature evidence of using SHAP values to explain PE prediction models. In this study, we used SHAP values to explain the contribution of machine learning in PE prediction, fully integrating engineering and medicine. First, the SHAP summary plot highlighted several key features critical for predictions, such as D-dimer, APTT, FFDP, and platelet count, aligning with earlier research outcomes25–27. Additionally, this analysis identified further factors not conventionally recognized as provocative risk elements associated with heightened PE risk, including albumin28, Sodium29, and cholesterol30. This underscores the intricate interplay between the hemostatic and internal environment systems31–33.

The MLA developed in our study offers distinct advantages over alternative risk stratification methods, such as adjusted D-dimer and scoring systems. Unlike these methods, our algorithm doesn’t require additional clinician inputs or disrupt workflow, which can automatically screen a broad inpatient population solely based on electronic health record (EHR) data. D-dimer, sensitive in detecting fibrinolysis of intravascular thrombus, lacks specificity and can be elevated in inflammatory states and other conditions34,35. The Wells criteria and revised Geneva score represent the most commonly used risk scores, yet they were designed for inpatients suspected of existing PE and not tailored for predicting future occurrences of PE. Furthermore, these scoring systems have only been validated for assessing PE risk in outpatients, not in hospitalized patients36,37. Additionally, Stals MAM38 noted remarkably low reproducibility in the scoring method.

In contrast, our MLA model not only enhances future PE prediction but also facilitates early detection preceding the confirmatory diagnostic process, consequently reducing unnecessary CTPA. However, there are still some areas that need to be improved in the future. For example, we need to include more clinical data in multi-centers, and minimize bias that can arise from unbalanced training, suboptimal architecture design or selection, and uneven application of models, which not only increases the reliability and accuracy of the predictive model, but also avoids the influence of the model caused by hospital factors39,40. In addition, with the popularization of PE prediction models, we try to build the best PE prediction models according to the classification of causes especially for non-thrombotic PE, so as to maximize the clinical outcome of PE patients41,42. Finally, there are various limitations in integration of the web-based tool into clinical workflows. These algorithms necessitate meticulous data processing, training on potentially extensive datasets, and iterative refinement aligned with real clinical scenarios. In addition, integration of MLA into clinical practice introduces critical ethical considerations, including issues of liability concerning medical errors, comprehension among healthcare professionals regarding how these algorithms generate predictions, as well as concerns regarding privacy, security, and patient data control43,44.

Conclusions

Our prediction model based on MLA was executed within a premier hospital setting, showcasing enhanced performance in identifying PE risk within suspected patient population. Remarkably, this predictive modeling tool has been designed as a simple web page that can be applied to the platform of clinical management. We only need to input some specified features of the patient into the system, and the risk index for pulmonary embolism is automatically generated within minutes. Our machine learning-based predictive model can not only help doctors to detect suspicious patients in time and decrease unnecessary CTPA, but also improve the clinical outcome of PE patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This article accepted professional scientific editing service from AJE. The authors also thank Shanghai Municipal Hospital Respiratory and Critical Medicine Specialist Alliance.

Author contributions

Q.Z. and R.H. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed equally for the whole study. Y.X. was involved in statistical analysis. Q.Z. and R.H. were involved in drafting of the manuscript. Y.X., Z.L. and W.Z. provided critical comments and edited the manuscript. All authors were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors provided administrative, technical and material support.

Funding

This study received the following funding: the San Hang Program of the Second Military Medical University; the Changjian Program of First Affiliated Hospital the Second Military Medical University to Wei Zhang. The Project of Disciplines of Excellence, Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (Grant No. 20234Z0017).

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, and we promised the whole process was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients wrote informed consent to participate this study. Because this study involved no more than minimal risk to patients, the need for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee on Biomedical Research (No.2021 − 828), West China Hospital of Sichuan University. We promised all efforts were made to protect patient privacy and anonymity.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qiao Zhou and Ruichen Huang.

Contributor Information

Xingyu Xiong, Email: xingyu870512@gmail.com.

Zongan Liang, Email: liangza@scu.edu.cn.

Wei Zhang, Email: zhangweismmu@126.com.

References

- 1.Di Nisio, M., van Es, N. & Büller, H. R. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet. 388(10063), 3060–3073 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rali, P. M. & Criner, G. J. Submassive pulmonary embolism. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 198(5), 588–598 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millington, S. J. et al. High and intermediate risk pulmonary embolism in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. 50(2), 195–208 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Righini, M., Robert-Ebadi, H. & Le Gal, G. Diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. J. Thromb. Haemost. 15(7), 1251–1261 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yazıcı, S. et al. Relation of contrast nephropathy to adverse events in pulmonary emboli patients diagnosed with contrast CT. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 34(7), 1247–1250 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams, L. S., Walker, G. R., Loewenherz, J. W. & Gidel, L. T. Association of contrast and acute kidney injury in the critically ill: a propensity-matched study. Chest. 157(4), 866–876 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matheny, M. E., Whicher, D. & Thadaney Israni, S. Artificial intelligence in health care: a report from the national academy of medicine. JAMA 323(6), 509–510 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen, G. & Dlugolinsky, S. Machine learning and deep learning frameworks and libraries for large-scale data mining: a survey. Artif. Intell. Rev. 52, 77–124 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handelman, G. S. et al. eDoctor: machine learning and the future of medicine. J. Intern. Med. 284(6), 603–619 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngiam, K. Y. & Khor, I. W. Big data and machine learning algorithms for health-care delivery. Lancet Oncol. 20(5), e262–e273 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haug, C. J. & Drazen, J. M. Artificial intelligence and machine learning in clinical medicine, 2023. N Engl. J. Med. 388(13), 1201–1208 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang, X. et al. Predicting the 10-Year risks of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in Chinese population: the China-PAR Project (Prediction for ASCVD Risk in China). Circulation. 134(19), 1430–1440 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu, W. et al. Evaluation of acute pulmonary embolism and clot burden on CTPA with deep learning. Eur. Radiol. 30(6), 3567–3575 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma, X. et al. A multitask deep learning approach for pulmonary embolism detection and identification. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 13087 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunsaker, A. R. Deep learning and risk assessment in acute pulmonary embolism. Radiology 302(1), 185–186 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma, M. et al. Predicting the molecular subtype of breast cancer and identifying interpretable imaging features using machine learning algorithms. Eur. Radiol. 32(3), 1652–1662 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freund, Y., Cohen-Aubart, F. & Bloom, B. Acute pulmonary embolism: a review. JAMA. 328(13), 1336–1345 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konstantinides, S. V. et al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur. Heart J. 41(4), 543–603 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barco, S. et al. Age-sex specific pulmonary embolism-related mortality in the USA and Canada, 2000-18: an analysis of the WHO mortality database and of the CDC multiple cause of death database. Lancet Respir Med. 9(1), 33–42 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peris, M. et al. Clinical characteristics and 3-month outcomes in cancer patients with incidental versus clinically suspected and confirmed pulmonary embolism. Eur. Respir J. 58(1), 2002723 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Motamedi, F. et al. Accelerating big data analysis through LASSO-random forest algorithm in QSAR studies. Bioinformatics 38(2), 469–475 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tseng, P. Y. et al. Prediction of the development of acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery by machine learning. Crit. Care 24(1), 478 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiao, N. et al. Machine learning prediction of venous thromboembolism after surgeries of major sellar region tumors. Thromb. Res. 226, 1–8 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang, G. et al. Machine learning-based models for predicting mortality and acute kidney injury in critical pulmonary embolism. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23(1), 385 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kearon, C. et al. Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with d-dimer adjusted to clinical probability. N Engl. J. Med. 381(22), 2125–2134 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klok, F. A. et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb. Res. 191, 145–147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alba, G. A. et al. NEDD9 is a novel and modifiable mediator of platelet-endothelial adhesion in the pulmonary circulation. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 203(12), 1533–1545 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Özcan, S. et al. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein/albumin ratio in acute pulmonary embolism. Rev. Invest. Clin. 74(2), 097–103 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou, Q., Xiong, X. Y. & Liang, Z. A. Developing a nomogram-based scoring tool to estimate the risk of pulmonary embolism. Int. J. Gen. Med. 15, 3687–3697 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonaca, M. P. et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering with evolocumab and outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the FOURIER Trial (further cardiovascular outcomes research with PCSK9 inhibition in subjects with elevated risk). Circulation. 137(4), 338–350 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanff, T. C. et al. Thrombosis in COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 95(12), 1578–1589 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loo, J., Spittle, D. A. & Newnham, M. COVID-19, immunothrombosis and venous thromboembolism: biological mechanisms. Thorax. 76(4), 412–420 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poor, H. D. Pulmonary thrombosis and thromboembolism in COVID-19. Chest. 160(4), 1471–1480 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Righini, M. et al. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels to rule out pulmonary embolism: the ADJUST-PE study. JAMA 311(11), 1117–1124 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suh, Y. J. et al. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology 298(2), E70–E80 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Medson, K. et al. Comparing ‘clinical hunch’ against clinical decision support systems (PERC rule, wells score, revised Geneva score and YEARS criteria) in the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. BMC Pulm Med. 22(1), 432 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirsch, B. et al. Wells score to predict pulmonary embolism in patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Am. J. Med. 134(5), 688–690 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stals, M. A. M. et al. Safety and efficiency of diagnostic strategies for ruling out pulmonary embolism in clinically relevant patient subgroups: a systematic review and individual-patient data meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 175(2), 244–255 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An, C. et al. Radiomics machine learning study with a small sample size: single random training-test set split may lead to unreliable results. PLoS One 16(8), e0256152 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vrudhula, A. et al. Machine learning and bias in medical imaging: opportunities and challenges. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 17(2), e015495. (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCabe, B. E. et al. Beyond pulmonary embolism; nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism as diagnostic challenges. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 48(4), 387–392 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asah, D. et al. Nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism from inorganic particulate matter and foreign bodies. Chest 153(5), 1249–1265 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daidone, M., Ferrantelli, S. & Tuttolomondo, A. Machine learning applications in stroke medicine: advancements, challenges, and future prospectives. Neural Regen Res. 19(4), 769–773 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Reilly-Shah, V. N. et al. Bias and ethical considerations in machine learning and the automation of perioperative risk assessment. Br. J. Anaesth. 125(6), 843–846 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.