Abstract

An electro- and optically favorable quaternary nanocomposite film was produced by solution-casting nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO NPs) into polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT/PSS). Based on transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and X-ray diffraction (XRD) observations, the synthesized NiO NPs have a cubic phase and a diameter between 10 and 45 nm. The complexity and interactions observed through XRD patterns, UV–visible spectra, and FTIR measurements suggest that the NPs are not just dispersed within the polymer matrix, but are interacting with it, leading to enhanced dielectric properties and AC electrical conductivity. From 9 × 103 to 3.22 × 103 Ω, NiO NPs concentrations reduce bulk resistance Rb, indicating more linked conductive channels. The dielectric tests showed that polarized nanoparticles increased polarizability under electric field conditions. The incorporation of NiO NPs boosted DC conductivity from 1.25 × 10–6 to 5.64 × 10–5 S m−1. The mobility of NiO NPs boosts DC conductivity linearly with field frequency. These interactions can lead to improved electrical conductivity, energy storage capabilities, and overall efficiency of the nanocomposite, making it a promising material for various applications.

Keywords: Nanocomposite, PEDOT:PSS, Bulk resistance, Dielectric constant, NiO

Subject terms: Materials science, Optics and photonics

Introduction

Currently, nanocomposite materials are attracting a lot of attention because of their unique properties. By combining two or more materials, the properties of each component are enhanced, creating materials that are stronger and more durable than either of the individual components. Furthermore, these nanocomposites can be tailored to have specific properties that make them useful for a variety of applications, including light-emitting devices1,2, sensors3, and direct methanol fuel cells4. There are several important synthesis methods for nanocomposite formation, including electrospinning5, sol–gel6, in situ processes7, casting techniques8, and pyrolysis9.

PVA is a semicrystalline polar polymer with hydroxyl groups that may form hydrogen bonds with different fillers in polymeric systems. PVA possesses strong dielectric properties, a high capacity for charge storage, and optical and dielectric features. So, PVA can be used for different applications such as optoelectronics and electronics sectors10–13. Furthermore, PVP is an amorphous, water-soluble, and non-toxic polymer. PVP has also drawn the attention of researchers because of its special qualities, which include its inexpensive cost, good dielectric nature, water solubility, and mechanical strength14,15. The presence of N-O, and C-O groups permits it to generate various complexes through covalent interactions with inorganic salts and nanofillers on their surface, which provide their stabilization without accumulations16. To improve the conductivity of the polymer blend, a conductive polymer may be incorporated. This additive not only enhances the dispersibility of the conductive particles but also increases the overall conductivity of the blend, making it suitable for various applications in electronics and energy storage17–19. PEDOT/PSS has superior electrochemical stability, high electrical conductivity (σ), and film-forming properties among these polymers20. The improvement of both the miscible polymer blend and its electrical conductivity results from the function groups involved in the backbone’s polymer chain21. In addition, the incorporation of nanoparticles within the polymer blend creates molecular bridges that enable the formation of nanocomposites. These nanoparticles’ uniform dispersion and distribution typically lead to the creation of large polymeric/filler interfacial areas in the composite, which is beneficial for the material’s electrical and dielectric properties22,23. Recently, scientists have gained a great interest in transition metal oxides because of their low cost, stability, and optoelectronic properties24–26. Reddy et al.27 prepared PVA/PEDOT: PSS/Copper (II) Oxide (CuO) nanocomposites with 15% CuO NPs, revealing good interaction and enhanced dielectric properties, suggesting potential energy storage applications due to their enhanced properties. The study also found that the higher dielectric constant, lower dielectric loss, and enhanced AC conductivity (σac = 1.67 × 10–5 S m−1 at 150 °C) decrease impedance and capacitive reactance with increased nanofiller content. NiO NPs, one of the most significant metal oxides, are characterized by their thermal stability and photostability, high melting (~ 1955 ◦C), refractive index of ≈ 2.2, and a wide optical bandgap (Eg = 3.4-4 eV)28,29. As a result, NiO NPs are suitable for a variety of applications, including gas sensors, batteries, electrochemical capacitors, magnetic materials, and catalysis30. NiO NPs can be incorporated into the thin film layer of the solar cell, enhancing its light absorption and improving the overall efficiency of the device30,31.

In this work, flexible quaternary polymeric nanocomposite films were created by solution-casting PVA, PVP, PEDOT/PSS, and NiO NPs. An extensive investigation was reported to compare the effects of various concentrations of NiO NPs on the electrical and dielectric properties of quaternary nanocomposite films.

Experimental section

Materials

PVA (Mw 31,000–50,000 g/mol), PVP (Mw 40,000 g/mol), and PEDOT/PSS (1.3 wt % dispersion in H2O) were all bought from Sigma-Aldrich. Nickel chloride hexahydrate (Nicl2. 6H2O) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) were obtained from Merck.

NiO NPs synthesis

The precipitation procedure was used to produce NiO NPs. In the first stage, a magnet stirrer was used to thoroughly dissolve nickel chloride hexahydrate and sodium hydroxide in deionized water. A molar ratio of 1:2 between the two aqueous solutions was gradually added drop by drop at room temperature T = 303 K under vigorous stirring. In the next stage, the precipitate was collected, filtered, and washed several times with deionized water. As a result of the precipitation process, the precipitate was collected, filtered, and rinsed with deionized water. In an oven at 363–368 K, it was dried for two days before being ground into a fine powder by agate mortars. After obtaining a fine powder, it was heated for four hours at 723 K, then ground for a second time. The particle size, on average, is 18.2 nm.

NiO/PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposite fabrication

Separately, 1 g of PVP and 1 g of PVA were completely dissolved in 100 mL deionized water at room temperature and 50 °C, respectively, and then mixed and stirred (300 rpm) for 6 h. Then, five equal volumes of 20 ml of dissolved PVP/PVA and 0.5 mL of PEDOT/PSS were added and stirred for 1 h. After that, 0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1.0 wt % of NiO NPs were dropped into the mixtures and stirred for 2 h. In the final step, the mixtures were cast into 55 mm diameter plastic Petri dishes and dried at 50 °C. The thickness of the films ranges from about 240 nm.

Characterization

Nanocomposite films were investigated using Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectroscopy in the 400 – 4000 cm−1 wavenumber range. XRD patterns were examined with a DIANO X-Ray Diffractometer using CuKα radiations. A UV-visible spectrophotometer was used to measure the optical absorption of the films. Japan’s JEOL/JEM/1011 TEM was used to examine NiO nanoparticles’ size and form. At 303 K, broadband dielectric spectroscopy (Novo Control Turnkey Concept 40 System) was used to measure the dielectric properties and impedances of the films. The EIS spectrum analyzer 1.0 is used to fit the impedance curves.

Results and discussion

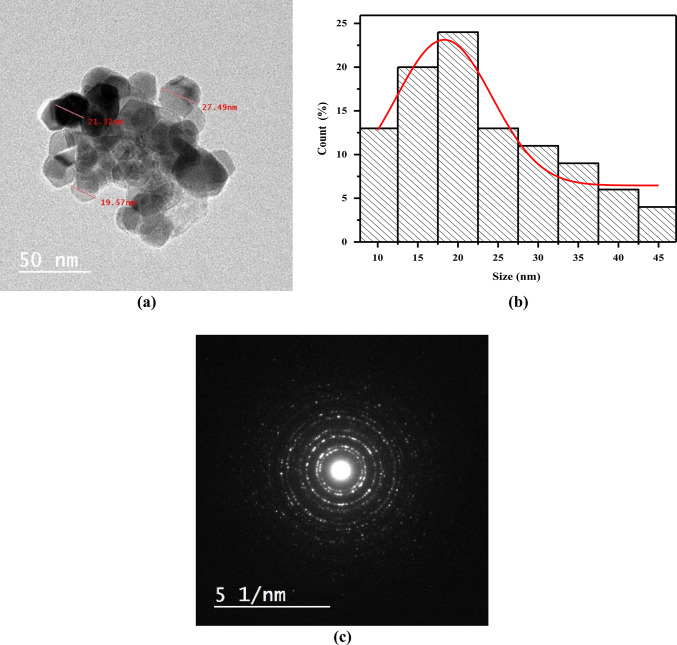

TEM of NiO NPs

Figure 1a illustrates the TEM image of NiO NPs with a cubic (hexagonal) structure of about 18.2 nm, based on the histogram distribution plot (Fig. 1b). The strong diffraction pattern of NiO NPs in Fig. 1c confirms the high degree of crystallinity of NiO NPs.

Fig. 1.

(a) TEM image, (b) histogram distribution plot, and, (c) diffraction pattern of NiO NPs.

X-ray diffraction analysis

XRD measurements are used to examine the crystal structure of nanocomposite samples. Figure 2 depicts the XRD pattern of NiO NPs, pure PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS, and various content NiO-filled PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS. A single broad diffraction peak was observed at 2θ = 22.26°, indicating high compatibility between the blend components. The diffraction peaks for pure NiO NPs were observed at 2θ = 37.31°, 43.42°, and 63.82°, which correspond respectively to the (111), the (200), and the (220) planes32. The observed peaks confirm that NiO NPs with high purity form a cubic structure. The crystal size (D) of prepared NiO NPs was calculated using Scherrer’s equation  where

where  is the x-ray wavelength,

is the x-ray wavelength,  is FWHM and

is FWHM and  is the diffraction angle33 listed in Table 1. In accordance with TEM results, it was found that the particle size is approximately 21 nm. As a result of NiO NP doping, the intensity and position of the abroad diffraction peak in the doped samples have changed slightly. The crystallinity (Xc) of the nanocomposite films is determined using the following formula34:

is the diffraction angle33 listed in Table 1. In accordance with TEM results, it was found that the particle size is approximately 21 nm. As a result of NiO NP doping, the intensity and position of the abroad diffraction peak in the doped samples have changed slightly. The crystallinity (Xc) of the nanocomposite films is determined using the following formula34:

|

1 |

where Apeak and Ahump represent the areas of crystalline and hump peaks. According to the Xc values, pure and NiO-filled nanocomposite films showed 56.15, 52.64, 45.75, 41.37, and 39.85%. As a result of the considerable variation in the polymer-nanofiller interaction, the decrease in Xc value indicates the formation of more amorphous regions within the nanocomposite films. This increase in amorphousness may explain the enhanced ionic diffusivity that is associated with high ionic conductivity35. Highly doped nanocomposite samples demonstrated three diffraction peaks of NiO NPs, confirming the presence of NiO NPs in these samples. As a consequence, the addition of NiO NPs to the PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS matrix supports the FTIR results, as detailed below.

Fig. 2.

XRD analysis of pure NiO NPs as well as PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS with various NiO contents.

Table 1.

The NiO NPs lattice parameters.

| 2θ (o) | h k l | d-spacing (Å) | FWHM | D (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37.25 | 111 | 2.4114 | 0.4394 | 19.92 |

| 43.29 | 200 | 2.0885 | 0.4706 | 18.96 |

| 62.86 | 220 | 1.4771 | 0.5760 | 16.87 |

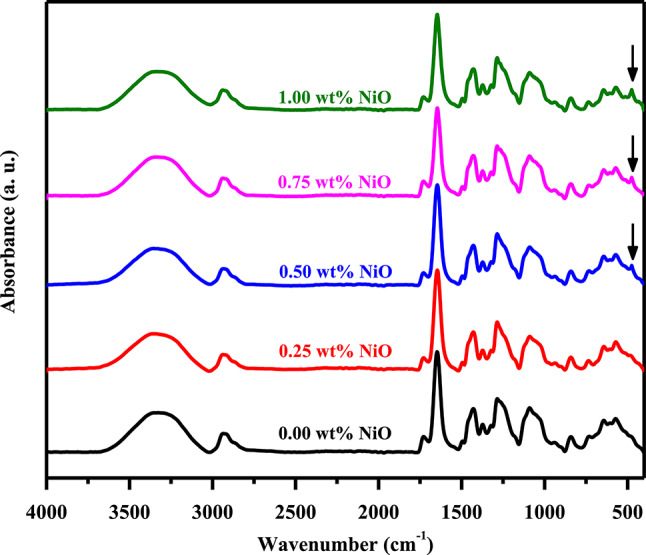

FTIR

FTIR spectra of pure and various percentages of NiO filled with PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS are shown in Fig. 3. The spectra of prepared films showed absorption bands associated with the bending and stretching vibrations generated by functional groups. A summary of these bands are listed in Table 2. There are vibration bands at 1386 cm−1, 1274 cm−1, and 843 cm−1 that correspond to the vibrations of CH2 bending36,37. The vibration bands at 2943 cm−1 correspond to the vibrations of CH2 symmetric stretching38 and 1088 cm−1 correspond to the vibrations of CO stretching of the characteristic vibration bands of PVA38. The peak at 1438 cm−1 is attributed to the C–N stretching vibration absorption of PVP39. PEDOT/PSS exhibited a band of absorption at 1647 cm−1 due to C=C stretching and 3322 cm−1 due to OH stretching39,40. The peak at 568 cm−1 can be attributed to N-C=O bending from PVP39,41. Upon adding NiO NPs with different concentrations to PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS, a small peak occurred at 475 cm−1 due to Ni-O vibrations. This peak increases slightly with increasing NiO concentration. These significant changes in peak intensities and extensive variations in a few peaks indicate polymer-nanoparticle interactions in nanocomposite films.

Fig. 3.

FTIR analysis of pure PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS and NiO/PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS with varying NiO content.

Table 2.

FTIR vibration modes of NiO/PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposites.

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Vibration mode | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3322 | O-H stretching | PEDOT/PSS, PVP, PVA | 39,40 |

| 2943 | CH2 symmetric stretching | PVA | 38 |

| 1737 | C=O stretching | PVA | 38 |

| 1647 | RC=C stretching | PEDOT/PSS | 40 |

| 1438 | C–N stretching vibration | PVP | 39 |

| 1386 | CH2 bending vibrations | PVA | 36 |

| 1274 | CH2 bending vibrations | PVA | 37 |

| 1088 | CO stretching | PVA | 37 |

| 843 | CH2 bending vibrations | PVA | 36 |

| 649 | C-N bending | PVP | 42 |

| 568 | N-C=O bending | PVP | 39,41 |

| 425 | Ni-O vibration | NiO | 42 |

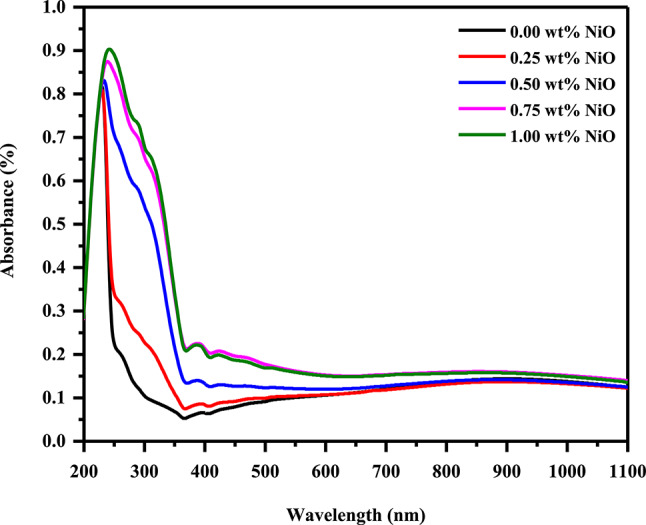

UV-VIS Absorption

Figure 4 shows the absorption spectra of pure PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS and NiO-filled PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposite with different NiO contents between 200 and 1100 nm. The spectrum of pure film displayed an absorption peak at 227.5 nm attributed to the π-π* transition43 due to C=C of pure PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS44. Upon the addition of NiO Nps, the absorbance of the NiO-filled PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposite samples increased, and its position shifted to 244 nm which can be explained by a change in band gap energy and is correlated to the modification in the crystallinity of the films. Moreover, there are another two small absorption peaks at 391 and 425 nm, which may be attributed to NiO nanoparticles45.

Fig. 4.

UV-Vis absorbance of pure PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS and filled with different NiO content.

The nature of optical transitions in the nanocomposite films is examined by the Tauc equation as follows46:

|

2 |

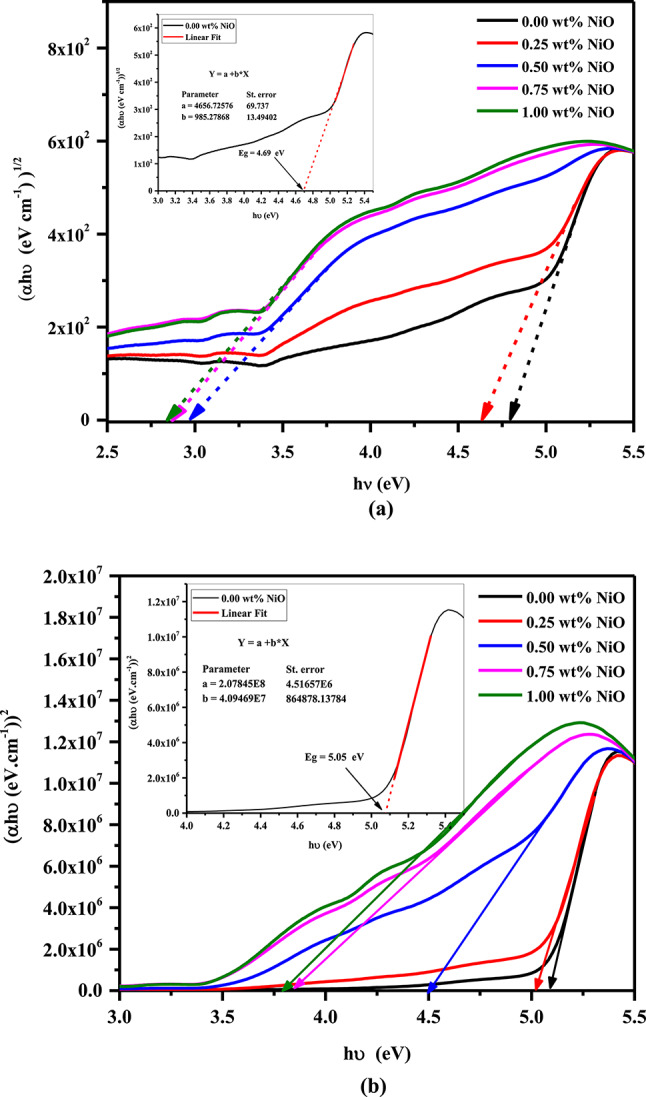

where B is a constant, α is the absorption coefficient (α = 2.303  ), and m is an exponent that characterizes the nature of the electronic transition nature, i.e., for the direct allowed transition (m = 1/2), and indirect allowed transition (m = 2). Figure 5a and b depicts the dependence of (αhυ)1/2 and (αhυ)2 on hυ for all samples. Table 3 shows the calculated values of direct (

), and m is an exponent that characterizes the nature of the electronic transition nature, i.e., for the direct allowed transition (m = 1/2), and indirect allowed transition (m = 2). Figure 5a and b depicts the dependence of (αhυ)1/2 and (αhυ)2 on hυ for all samples. Table 3 shows the calculated values of direct ( ) and indirect (

) and indirect ( ) band gap energies via linearly fitted and intercept on the hυ axis. It is observed that the indirect and direct energy gaps decrease with increasing NiO NP concentrations. The changes in the energy gap values could be attributed to the presence of NiO NPs, which introduced polaronic and defect levels that altered the electronic structure of the polymeric matrix47. Consequently, the quantity of these defects and the concentration of NiO NPs are related to the density of localized states N(E). There is evidence that the spread of localized states with various colored centers in the mobility gap may be triggered by an increase in NiO NPs concentrations30,31. Additionally, this increase in localized states may indicate that the filled samples have a lower degree of crystallinity48. Based on XRD and electrical conductivity measurements, these results are consistent with those obtained. The enhanced optical energy values suggest electrochemical and optoelectronic applications.

) band gap energies via linearly fitted and intercept on the hυ axis. It is observed that the indirect and direct energy gaps decrease with increasing NiO NP concentrations. The changes in the energy gap values could be attributed to the presence of NiO NPs, which introduced polaronic and defect levels that altered the electronic structure of the polymeric matrix47. Consequently, the quantity of these defects and the concentration of NiO NPs are related to the density of localized states N(E). There is evidence that the spread of localized states with various colored centers in the mobility gap may be triggered by an increase in NiO NPs concentrations30,31. Additionally, this increase in localized states may indicate that the filled samples have a lower degree of crystallinity48. Based on XRD and electrical conductivity measurements, these results are consistent with those obtained. The enhanced optical energy values suggest electrochemical and optoelectronic applications.

Fig. 5.

(a) (αhυ)1/2 vs hυ (inset plot of band gap energy calculation via linear fitting) and (b) (αhυ)2 vs hυ (inset plot of band gap energy calculation via linear fitting) of NiO/PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS with varying NiO content.

Table 3.

The band gap energy and linear refractive index values of NiO/PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposite.

| NiO NPs @ Sample (wt%) |

(eV) (eV) |

(eV) (eV) |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 4.69

|

5.08

|

2.03 | 1.98 |

| 0.25 | 4.50  0.13 0.13 |

5.01  0.07 0.07 |

2.05 | 1.99 |

| 0.50 | 2.91

|

4.49  0.04 0.04 |

2.40 | 2.06 |

| 0.75 | 2.81  0.04 0.04 |

3.84  0.03 0.03 |

2.43 | 2.18 |

| 1.00 | 2.79  0.06 0.06 |

3.79  0.02 0.02 |

2.44 | 2.19 |

Among the most essential optical properties, the refractive index n plays a significant role in practical applications. It governs a wide range of optoelectronic and electronic applications, including LEDs, waveguides, photodetectors, and filters. Based on the optical band gaps, the Dimitrov-Sakka equation can be used to calculate the linear refractive index no49:

|

3 |

As indicated in Table 3, an increase in NiO NPs results in a rise in refractive index values. The increased refractive index of nanocomposite films after incorporating NiO NPs could be the result of structural changes in the polymeric matrix.

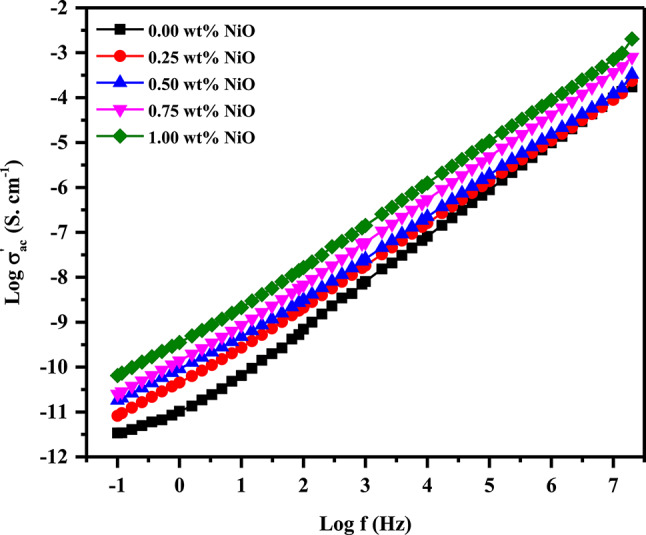

Conductivity analysis

The mobility of charge carriers is an important component in influencing the electrical conductivity of amorphous polymers. Tunable capacitors, sensors, and RF filters can all benefit from frequency dependency. Furthermore, the approach may be applied to enhance the electrical characteristics of complicated nanocomposites. By applying AC voltages across the sample at various frequencies, impedance spectroscopy can be used to determine the AC conductivity of samples:

|

4 |

Specifically, tanδ refers to the dissipation factor, f refers to the frequency of the applied signal, and ε′ and εo represent the dielectric constants of the material and free space, respectively. Figure 6 shows the frequency response of PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS loaded with different percentages of NiO NPs at ambient temperatures. Based on the figure, it appears that conductivity increases with NiO NPs content since more current paths are provided by the dispersed NiO NPs. Such nanocomposites exhibit varying conductivities depending on the shape, type, size, and dispersion of nanofillers50,51. Amorphous polymers allow more contact points between nanoparticles and polymer matrix, increasing electron and ion pathways. This improves the conductivity of nanocomposite by allowing electrons and ions to travel easily through it45.

Fig. 6.

The changes in Log (σac) versus Log f for pure and NiO-filled nanocomposite films.

A low-frequency system has a nearly constant conductivity, but a high-frequency system follows the power-law equation of Jonscher52:

|

5 |

In this scenario, σdc represents DC conductivity (at  ≈ 0), A represents a frequency-dependent component that affects the degree of polarizability, and s represents a temperature and frequency-dependent exponent.

≈ 0), A represents a frequency-dependent component that affects the degree of polarizability, and s represents a temperature and frequency-dependent exponent.

According to Jonscher, a 'universal dynamic reaction’ may be applied to a wide range of materials45. Low-frequency ranges are associated with bulk conductivity, which is generated by charge carrier displacements and hence connected to DC conductivity51. Charge carriers’ conductivity improves linearly with frequency because higher frequencies allow them to travel more easily than lower frequencies53. At higher frequencies, the loss factor dominates, resulting in a relative increase in conductivity54. The σdc value exhibited an increase from 1.25 × 10–6 to 5.64 × 10–5 S.m−1 with the addition of NiO NPs.

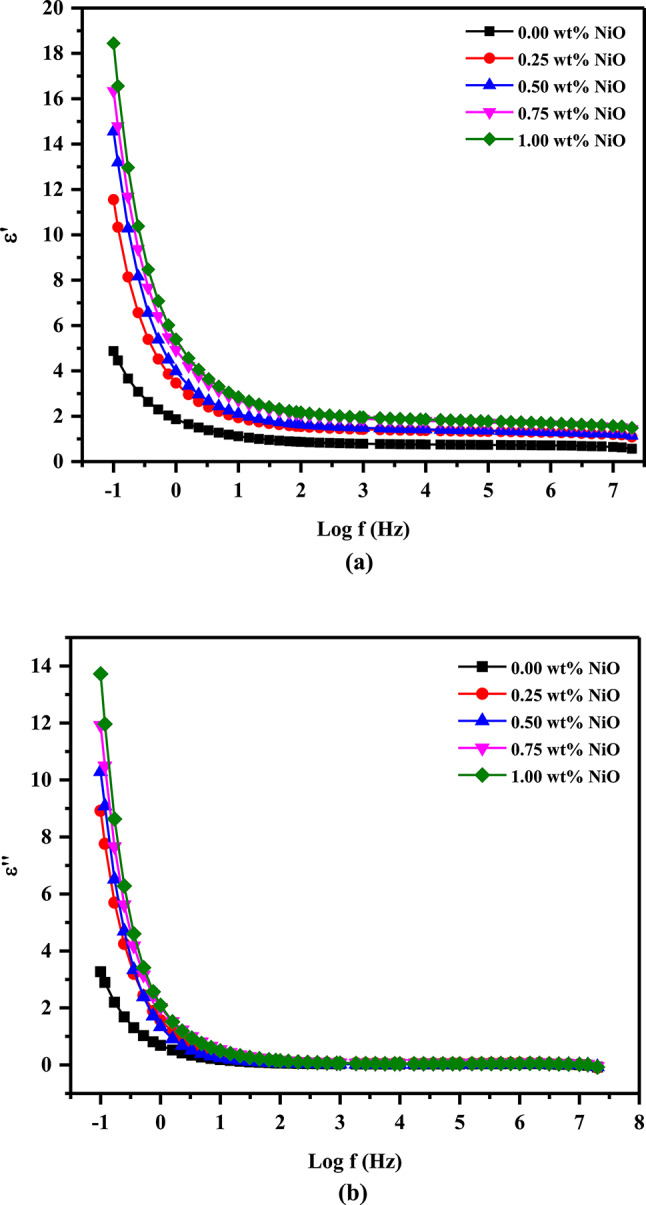

Dielectric characteristics

The dielectric constant (ε′) of a material is a measurement of its electrical properties, and it is a measure of how strongly the material can store an electrical charge. Material with a higher dielectric constant can store more electrical energy. The dielectric loss (ε″) is the amount of energy lost as heat or radiation when a substance is exposed to an electric field. It is an important measure for materials that are used in electrical applications, as it determines the efficiency of the material. A low dielectric constant provides excellent insulation for high-frequency applications, reducing the amount of energy lost as heat55. Following are the equations used to calculate dielectric constants and loss values:

|

6 |

|

7 |

Here, d, A, and C represent sample thickness, cross-sectional area, and capacitance, respectively. PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS nanocomposites filled with NiO NPs show changes in ε′ and ε″ over frequency as illustrated in Fig. 7a and b. As a result, higher frequencies have a reduced effect on ε′ and ε″ values. At low frequencies, the high ε′ and ε″ values may be attributable to electrode and interface impacts, which account for the bulk of samples. Polar materials have high ε′ and ε″ values at low field frequencies but decline as field frequencies grow due to dipoles’ inability to keep up with variations35,40. Upon filling the NiO NPs, ε′ and ε″ values increased across all frequency ranges. With increasing NiO NPs concentrations, more of these nanocapacitors are produced, resulting in greater dielectric constants. Nano-fillers also increase the dielectric constant of dipoles by lowering limitations on their response to electrical fields56. On the other hand, NiO NPs and the dielectric matrix may polarize due to Maxwell–Wagner-Sillars (MWS) phenomena. A mismatch in conductivity or permittivity between the NPs and the matrix causes this polarization, which improves dielectric characteristics at lower frequencies57.

Fig. 7.

Frequency dependence of the (a) real and (b) imaginary part of the dielectric constant of the nanocomposite films.

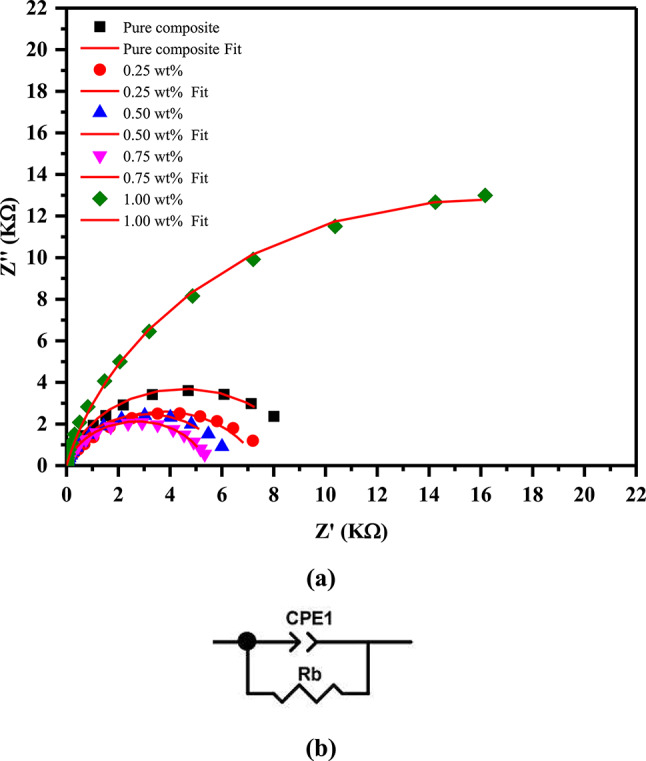

Complex electric impedance

The complex impedance analysis of the samples under investigation can be obtained using the equation below58:

|

8 |

The real and imaginary components of the complex impedance are denoted by Z′ and Z′′, respectively. Figure 8a shows Nyquist plots for the films, which were measured at room temperature and covered a broad range of frequencies between 10–1 Hz and 107 Hz. Nyquist curves generate semicircular arcs with their centers located below Z’. In this semicircular arc, stationary polymer chains produce bulk capacitance, while ions’ motion produces bulk resistance59. The semicircular arc’s depression in its center indicates that the ionic relaxation mechanism is not Debye. A departure from the Debye type can be caused by uneven thicknesses and morphologies of the investigated films, as well as rough electrode surfaces. Nanocomposites’ Debye-type behavior may be affected by film thicknesses and morphologies. Different film thicknesses alter charge buildup and dispersion, influencing dielectric response. Additionally, rough electrode surfaces might complicate charge transport pathways, resulting in non-ideal dielectric behavior60.

Fig. 8.

(a) The examined samples’ Nyquist plots and (b) their equivalent circuit.

The diameter of the semicircle decreases as the concentration of NiO NPs rises, demonstrating that bulk resistivity decreases while ionic conductivity increases.

Figure 8b shows an equivalent circuit with resistors and capacitances to demonstrate the impedance link between microstructure and electrical properties. Bulk Resistance (Rb) and Partial Capacitance (CPE) are used in parallel to form this circuit. This CPE’s impedance can be estimated as follows61:

|

9 |

CPE capacitors have diverged from purity as shown by this relationship, where Q represents 1/|Z| at 1rad/s, and n represents the element phase. At n = 1, the CPE functions as a pure capacitor, and at n = 0, it acts as a pure resistor.

According to Fig. 8a, the parameters of the equivalent circuit are listed in Table 4. The bulk resistance Rb lowers with increasing concentrations of NiO NPs, suggesting more interconnected conductive channels62. Additionally, bulk capacitance values (Q) rise with increasing concentrations of NiO NPs. The equivalent circuit selected is reasonably compatible with the data obtained.

Table 4.

The fitting of equivalent circuit parameters.

| NiO NPs @ Films (wt%) | Fitting parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rb (ohm) | Q (F) | N | |

| 0.00 | 9.00 × 103 | 3.08 × 10–5 | 0.88 |

| 0.25 | 7.43 × 103 | 4.53 × 10–5 | 0.78 |

| 0.50 | 6.22 × 103 | 4.64 × 10–5 | 0.86 |

| 0.75 | 5.53 × 103 | 5.35 × 10–5 | 0.84 |

| 1.00 | 3.22 × 103 | 7.96 × 10–5 | 0.85 |

Conclusion

Nanocomposite films with different synthesized NiO NP contents were created by solution-casting PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS blends. According to XRD and TEM analyses, the NiO nanoparticles have a cubic structure of approximately 18.2 nm. Incorporating NiO NPs into PVA/PVP/PEDOT/PSS reduces the nanocomposites’ crystallinity. A distinctive diffraction peak confirmed the presence of NiO NPs. FT-IR spectra indicate the complexation between NiO NPs and polymeric composite. The bandgap energies of the nanocomposite films dropped with an increase in NiO NPs content, from 4.69  0.14 eV to 2.79

0.14 eV to 2.79  0.06 eV for indirect bandgaps and 5.08

0.06 eV for indirect bandgaps and 5.08  0.05 eV to 3.79

0.05 eV to 3.79  0.02 eV for direct bandgaps. Impedance spectroscopy demonstrated that higher NiO NP concentrations increased the nanocomposite’s dielectric properties and AC conductivity. The equivalent electrical circuits’ impedance components Z′ and Z′′ were examined. Therefore, the decrease in the bulk resistance implies a stronger electrical pathway inside the polymeric materials. The nanocomposite films exhibited different electrical and optical properties depending on the NiO NPs content.

0.02 eV for direct bandgaps. Impedance spectroscopy demonstrated that higher NiO NP concentrations increased the nanocomposite’s dielectric properties and AC conductivity. The equivalent electrical circuits’ impedance components Z′ and Z′′ were examined. Therefore, the decrease in the bulk resistance implies a stronger electrical pathway inside the polymeric materials. The nanocomposite films exhibited different electrical and optical properties depending on the NiO NPs content.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) under grant number 43671.

Author contributions

E. Salim: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation, writing—review & editing. A. Magdy: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing & editing, Formal analysis. A. El-Shaer: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. A.H. EL-Farrash: Conceptualization, Supervision, review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Open access funding is provided by the Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

The corresponding author is responsible for providing reasonable access to the datasets used in this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang, W. et al. CsPbBr3/Cs4PbBr6 nanocomposites: Formation mechanism, large-scale and green synthesis, and application in white light-emitting diodes. Cryst. Growth Des.18, 6133–6141 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobbara, S. R., Salim, E., Barille, R. & Nunzi, J.-M. Light-induced electroluminescence patterning: Interface energetics modification at semiconducting polymer and metal-oxide heterojunction in a photodiode. J. Phys. Chem. C122, 23506–23514 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tajik, S. et al. Recent developments in polymer nanocomposite-based electrochemical sensors for detecting environmental pollutants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.60, 1112–1136 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rambabu, G., Bhat, S. D. & Figueiredo, F. M. L. Carbon nanocomposite membrane electrolytes for direct methanol fuel cells—A concise review. Nanomaterials9, 1292 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badali, Y., Koçyiğit, S., Aytimur, A., Altındal, Ş & Uslu, İ. Synthesis of boron and rare earth stabilized graphene doped polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanocomposite piezoelectric materials. Polym. Compos.40, 3623–3633 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fadli, A. H., Yulkifli, Darvina, Y., Hartono, A. & Ramli, R. The electrical properties of NiFe2O4-PVDF nanocomposite prepared by sol-gel method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.1481, 012023 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zang, C. et al. In situ growth of ZnO/Ag2O heterostructures on PVDF nanofibers as efficient visible-light-driven photocatalysts. Ceram. Int.48, 27379–27387 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, H. et al. Enhanced energy density in sandwich-structured P(VDF-HFP) nanocomposites containing Hf0.5Zr0.5O2 nanofibers. Chem. Eng. J.436, 131123 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choudhary, H. K., Kumar, R., Pawar, S. P. & Sahoo, B. Role of graphitization-controlled conductivity in enhancing absorption dominated EMI shielding behavior of pyrolysis-derived Fe3C@C-PVDF nanocomposites. Mater. Chem. Phys.263, 124429 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarkar, N., Sahoo, G. & Swain, S. K. Graphene quantum dot decorated magnetic graphene oxide filled polyvinyl alcohol hybrid hydrogel for removal of dye pollutants. J. Mol. Liq.302, 112591 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajesh, K., Crasta, V., Rithin Kumar, N. B., Shetty, G. & Rekha, P. D. Structural, optical, mechanical and dielectric properties of titanium dioxide doped PVA/PVP nanocomposite. J. Polym. Res.26, 99 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Bermany, E., Mekhalif, A. T., Banimuslem, H. A., Abdali, K. & Sabri, M. M. Effect of green synthesis bimetallic Ag@SiO2 core–shell nanoparticles on absorption behavior and electrical properties of PVA-PEO nanocomposites for optoelectronic applications. Silicon15, 4095–4107 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdallah, E. M. et al. Elucidation of the effect of hybrid copper/selenium nanofiller on the optical, thermal, electrical, mechanical properties and antibacterial activity of polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl cellulose blend. Polym. Eng. Sci.63, 1974–1988 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, J. et al. Nanocomposites membranes from cellulose nanofibers, SiO2 and carboxymethyl cellulose with improved properties. Carbohydr. Polym.233, 115818 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AlAbdulaal, T. H., Abdullah, W. & Yahia, I. S. Synthesizing and exploring the structural and optical properties of PVA/PVP/PEG polymeric sheet upon doping with nano nickel oxide (NiO) for CUT-OFF filters. J. Mater. Res. Technol.27, 8308–8322 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Sayed, A. M. & Khabiri, G. Spectroscopic, optical and dielectric investigation of (Mg, Cu, Ni, or Cd) acetates’ influence on carboxymethyl cellulose sodium salt/polyvinylpyrrolidone polymer electrolyte films. J. Electron. Mater.49, 2381–2392 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chalmers, E., Lee, H., Zhu, C. & Liu, X. Increasing the conductivity and adhesion of polypyrrole hydrogels with electropolymerized polydopamine. Chem. Mater.32, 234–244 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han, L. et al. Transparent, adhesive, and conductive hydrogel for soft bioelectronics based on light-transmitting polydopamine-doped polypyrrole nanofibrils. Chem. Mater.30, 5561–5572 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin, J. et al. Self-assembled functional components-doped conductive polypyrrole composite hydrogels with enhanced electrochemical performances. RSC Adv.10, 10546–10551 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen, C., Kine, A., Nelson, R. D. & LaRue, J. C. Impedance spectroscopy study of conducting polymer blends of PEDOT:PSS and PVA. Synth. Met.206, 106–114 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saroj, A. L., Chaurasia, S. K., Kataria, S. & Singh, R. K. Isothermal and non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of PVA + ionic liquid [BDMIM][BF4]-based polymeric films. Phase Transit.89, 578–597 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alghunaim, N. S. Effect of CuO nanofiller on the spectroscopic properties, dielectric permittivity and dielectric modulus of CMC/PVP nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol.8, 3596–3602 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaabour, L. H. Effect of selenium oxide nanofiller on the structural, thermal and dielectric properties of CMC/PVP nanocomposites. J. Mater. Res. Technol.9, 4319–4325 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morsi, M. A., Abdelrazek, E. M., Tarabiah, A. E. & Salim, E. Preparation and tuning the optical and electrical properties of polyethylene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol/poly(3,4-thylenedioxythiophene): Polystyrene sulfonate/CuO-based quaternary nanocomposites for futuristic energy storage devices. J. Energy Storage80, 110239 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agha, M., El-Kemary, M., Oraby, A. H. & Salim, E. Efficient multilayers organic solar cells with hybrid interfacial layer-based P3HT and CuO nanoparticles. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.34, 557–564 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salim, E., Abdelghany, A. M. & Tarabiah, A. E. Ameliorating and tuning the optical, dielectric, and electrical properties of hybrid conducting polymers/metal oxide nanocomposite for optoelectronic applications. Mater. Chem. Phys.313, 128788 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy, P. L. & Pasha, S. K. K. Polyvinyl alcohol/poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly(styrenesulfonic acid)/copper (II) oxide nanocomposites as high performance dielectric materials for energy storage applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.34, 960 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guillemot, T., Schneider, N., Loones, N., Javier Ramos, F. & Rousset, J. Electrochromic nickel oxide thin films by a simple solution process: Influence of post-treatments on growth and properties. Thin Solid Films661, 143–149 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Sayed, A. M. Exploring the morphology, optical and electrical properties of nickel oxide thin films under lead and iridium doping. Physica B Condens. Matter.600, 412601 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salim, E. Charge extraction enhancement in hybrid solar cells using n-ZnO/p-NiO nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.32, 28830–28839 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan, S., El-Shaer, A., Oraby, A. H. & Salim, E. Investigations of charge extraction and trap-assisted recombination in polymer solar cells via hole transport layer doped with NiO nanoparticles. Opt. Mater. (Amst.)145, 114413 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhas, S. D. et al. Synthesis of NiO nanoparticles for supercapacitor application as an efficient electrode material. Vacuum181, 109646 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magdy, A., El-Shaer, A., EL-Farrash, A. H. & Salim, E. Influence of corona poling on ZnO properties as n-type layer for optoelectronic devices. Sci. Rep.12, 21489 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alshehari, A. M., Salim, E. & Oraby, A. H. Structural, optical, morphological and mechanical studies of polyethylene oxide/sodium alginate blend containing multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Mater. Res. Technol.15, 5615–5622 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salleh, N. S., Aziz, S. B., Aspanut, Z. & Kadir, M. F. Z. Electrical impedance and conduction mechanism analysis of biopolymer electrolytes based on methyl cellulose doped with ammonium iodide. Ionics (Kiel)22, 2157–2167 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alrebdi, T. A. et al. Enhanced adsorption removal of phosphate from water by Ag-doped PVA-NiO nanocomposite prepared by pulsed laser ablation method. J. Mater. Res. Technol.20, 4356–4364 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irfan, M. et al. Preparation, structural characterization and electrical studies on NiO doped PVA films. Mater. Today Proc.5, 10839–10844 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waly, A. L., Abdelghany, A. M. & Tarabiah, A. E. A comparison of silver nanoparticles made by green chemistry and femtosecond laser ablation and injected into a PVP/PVA/chitosan polymer blend. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.33, 23174–23186 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahma, A. et al. Intermolecular interactions and the release pattern of electrospun curcumin-polyvinyl(pyrrolidone) fiber. Biol. Pharm. Bull.39, 163–173 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salim, E., Hany, W., Elshahawy, A. G. & Oraby, A. H. Investigation on optical, structural and electrical properties of solid-state polymer nanocomposites electrolyte incorporated with Ag nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.12, 21201 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamaruddin, Edikresnha, D., Sriyanti, I., Munir, M. M. & Khairurrijal,. Synthesis of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-green tea extract composite nanostructures using electrohydrodynamic spraying technique. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng.202, 012043 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.El Sayed, A. M. & Saber, S. Structural, optical analysis, and Poole-Frenkel emission in NiO/CMC–PVP: Bio-nanocomposites for optoelectronic applications. J. Phys. Chem. Solids163, 110590 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atta, M. R., Alsulami, Q. A., Asnag, G. M. & Rajeh, A. Enhanced optical, morphological, dielectric, and conductivity properties of gold nanoparticles doped with PVA/CMC blend as an application in organoelectronic devices. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.32, 10443–10457 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdallah, E. M., Qahtan, T. F., Abdelrazek, E. M., Asnag, G. M. & Morsi, M. A. Enhanced the structural, optical, electrical and magnetic properties of PEO/CMC blend filled with cupper nanoparticles for energy storage and magneto-optical devices. Opt. Mater. (Amst.)134, 113092 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salim, E. & Tarabiah, A. E. The influence of NiO nanoparticles on structural, optical and dielectric properties of CMC/PVA/PEDOT:PSS nanocomposites. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater.33, 1638–1645 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tauc, J. Absorption edge and internal electric fields in amorphous semiconductors. Mater. Res. Bull.5, 721–729 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Hakimi, A. et al. Enhancing the structural, optical, thermal, and electrical properties of PVA filled with mixed nanoparticles (TiO2/Cu). Crystals (Basel)13, 135 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tarabiah, A. E. et al. Enhanced structural, optical, electrical properties and antibacterial activity of PEO/CMC doped ZnO nanorods for energy storage and food packaging applications. J. Polym. Res.29, 167 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dimitrov, V. & Sakka, S. Linear and nonlinear optical properties of simple oxides. II. J. Appl. Phys.79, 1741–1745 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh, N. L., Qureshi, A., Rakshit, A. K. & Avasthi, D. K. Analysis of Organometallics Dispersed Polymer Composite Irradiated with Oxygen Ions. Bull. Mater. Sci vol. 29 (2006).

- 51.Rahaman, M. et al. A new insight in determining the percolation threshold of electrical conductivity for extrinsically conducting polymer composites through different sigmoidal models. Polymers (Basel)9, 527 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Muntaser, A. et al. Incorporated TiO2 nanoparticles into PVC/PMMA polymer blend for enhancing the optical and electrical/dielectric properties: Hybrid nanocomposite films for flexible optoelectronic devices. Polym. Eng. Sci.10.1002/pen.26476 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhajantri, R. F., Ravindrachary, V., Harisha, A., Ranganathaiah, C. & Kumaraswamy, G. N. Effect of barium chloride doping on PVA microstructure: Positron annihilation study. Appl. Phys. A87, 797–805 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jebli, M. et al. Structural and morphological studies, and temperature/frequency dependence of electrical conductivity of Ba0.97La0.02Ti1−xNb4x/5O3 perovskite ceramics. RSC Adv.11, 23664–23678 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tan, D. Q. Review of polymer‐based nanodielectric exploration and film scale‐up for advanced capacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater.30 (2020).

- 56.Thakur, Y. et al. Enhancement of the dielectric response in polymer nanocomposites with low dielectric constant fillers. Nanoscale9, 10992–10997 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koner, S. et al. Effect of interface coupling between polarization and magnetization in La0.7Pb0.3MnO3 (LPMO)/P(VDF-TrFE) flexible nanocomposite films. J. Mater. Sci.57, 7621–7641 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khalil, R. Impedance and modulus spectroscopy of poly(vinyl alcohol)-Mg[ClO4]2 salt hybrid films. Applied Physics A123, 422 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al-Muntaser, A. A., Pashameah, R. A., Sharma, K., Alzahrani, E. & Tarabiah, A. E. Reinforcement of structural, optical, electrical, and dielectric characteristics of CMC/PVA based on GNP/ZnO hybrid nanofiller: Nanocomposites materials for energy-storage applications. Int. J. Energy Res.46, 23984–23995 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lanfredi, S. Electric conductivity and relaxation in fluoride, fluorophosphate and phosphate glasses: Analysis by impedance spectroscopy. Solid State Ion146, 329–339 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Muntaser, A. A. et al. Tuning the structural, optical, electrical, and dielectric properties of PVA/PVP/CMC ternary polymer blend using ZnO nanoparticles for nanodielectric and optoelectronic devices. Opt. Mater. (Amst.)140, 113901 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nasrallah, D. A., El-Metwally, E. G. & Ismail, A. M. Structural, thermal, and dielectric properties of porous PVDF/Li4Ti5O12 nanocomposite membranes for high-power lithium-polymer batteries. Polym. Adv. Technol.32, 1214–1229 (2021). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding author is responsible for providing reasonable access to the datasets used in this study.