Abstract

BPV1, BPV2, BPV13, and BPV14 are all genotypes of bovine delta papillomaviruses (δPV), of which the first three cause infections in horses and are associated with equine sarcoids. However, BPV14 infection has never been reported in equine species. In this study, we examined 58 fresh and thawed commercial semen samples from healthy stallions. In 34 (58.6%), bovine δPV DNA was detected and quantified using droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR). Real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was able to identify bovine δPV DNA in 5 samples (8.6%). Of the BPV-infected semen samples, 15 were positive for BPV2 (~ 44.1%) on ddPCR and 4 (~ 11.7%) on qPCR; 12 (~ 35.3%) for BPV14 on ddPCR and 1 (~ 3%) by qPCR; 4 (~ 11.7%) for BPV1 on ddPCR, whereas qPCR failed to reveal this infection; 3 (~ 8.8%) for BPV13 on ddPCR; and BPV13 infection was not detected by qPCR. Our study showed for the first time that BPV14 is an additional infectious agent potentially responsible for infection in horses, as its transcripts were detected and quantified in some semen samples. Large-scale BPV14 screening is necessary to provide substantial data on the molecular epidemiology for a better understanding of the geographical divergence of BPV14 prevalence in different areas and how widespread BPV14 is among equids.

Keywords: Bovine papillomavirus, Commercial stallion semen, Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), Healthy stallions, Real time quantitative PCR (qPCR), Semen

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Immunology, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Bovine papillomaviruses (BPVs) are double-stranded DNA viruses that can cause both cutaneous and mucosal infections. Persistent viral infection results in epithelial and mesenchymal tumors in cattle1.

Currently, 44 BPV genotypes have been molecularly identified, of which 26 have been assigned to five genera: Deltapapillomavirus (δPV) (BPV1, BPV2, BPV13, and BPV14), Xipapillomavirus (χPV) (BPV3, BPV4, BPV6, BPV9, BPV10, BPV11, BPV12, BPV15, BPV17, BPV20, BPV23, BPV24, BPV26, BPV28, and BPV29), Epsilonpapillomavirus (εPV) (BPV5, BPV8 and BPV25), Dyokappapapillomavirus (DyoκPV) (BPV16, BPV18 and BPV22) and Dyoxipapillomavirus (DyoχPV) (BPV7). The remaining 18 genotypes remain to be classified2.

Bovine δPVs are highly pathogenic, being associated with benign and malignant tumors of skin and bladder of cattle3–8. More recently, bovine δPV infection has often been associated with reproductive disorders in large and small ruminants due to its ability to undergo transplacental vertical transmission9–11.

Besides cattle, bovine δPVs have been found in other animal species, including in the skin and bladder tumors of water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis)5,12,13, skin lesions of newborn lambs7, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy sheep and goats14–16. Furthermore, bovine δPVs appeared to be involved in molecular pathways leading to equine sarcoids17,18. However, the relationship to the BPV is still poorly understood, and there is not any actual vaccination program for the BPV in the management or prevention of this disease, which makes sarcoid to frustrate practicing veterinarians because there is no consistently effective treatment. BPV1 and BPV2 are believed to be the predominant viruses responsible for BPV-associated diseases in horses19,20. Recently, BPV13 was also identified in equine sarcoids21; however, about 10% of sarcoids did not contain any detectable BPV1 and BPV2; therefore, it has been suggested that some sarcoids could be associated with other papillomavirus (PV) types20. Very recently, ovine papillomavirus (OaPV) DNA was detected and quantified in equine sarcoids22, confirming the results of previous studies on the pathogenic potential of these viruses to be responsible for both cross-species transmission and infection23,24.

From a clinical perspective, PV infection is characterized by virus latency, which defines a particular type of subclinical infection that does not support virus synthesis, while host immunity cannot clear viral genomes from the infected basal cells25. During this phase of the viral life cycle, its concentration in tissues could not be detected, and was too low to be determined by conventional methods26. PV latency increases the likelihood of persistent infection in animal populations27.

Currently, little information is available regarding the actual incidence of PV infections in male domestic animals, particularly regarding the presence and significance of PVs in semen. Bovine δPVs have very rarely been found in the semen of healthy bulls28,29 and, to our knowledge, there has been only one report describing BPV1 E5 expression in the semen of healthy horses30. Equus caballus papillomavirus type 2 (EcPV2) DNA and transcriptionally active OaPVs have recently been detected in the semen of healthy horses31,32. Further, it has been suggested that the sensitivity of PV detection in semen samples is generally low33, which could explain the hurdles in detecting PV in semen using traditional diagnostic tools. Furthermore, the antiviral activity of some semen raises technical problems in attempts to detect and isolate viruses from this matrix34.

Digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) is used to detect and directly quantify low-abundance pathogens with a high degree of sensitivity. As such, droplet dPCR (ddPCR) provides more precise and reproducible detection of pathogen load in the clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases, including viral diseases26. Currently, ddPCR is the most accurate and sensitive molecular procedure for measuring PV load in both human and veterinary medicine35–37.

In this study, we performed a virological evaluation, using ddPCR to detect and quantify bovine δPV nucleic acids in the semen of healthy stallions in order to better understanding the epidemiology of bovine δPV infection in horses, as bovine δPVs play a role in some equine viral diseases.

Results

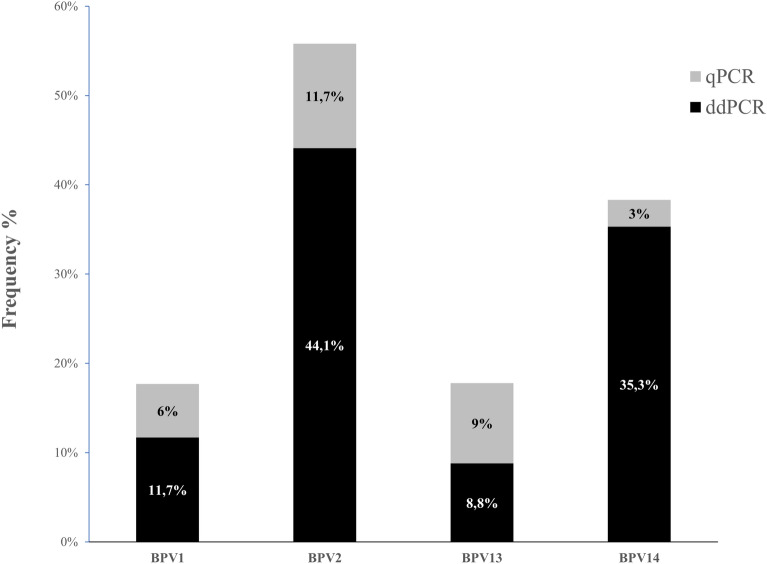

The frequency of occurrence of bovine δPV DNA in semen was 58.6% using ddPCR (34/58) and 8.6% using qPCR (5/58). Differences between the two molecular protocols were determined to be statistically significant using McNemar’s test (p value p < 0.0001). Of BPV-infected semen, ~ 11.7% (4/34) were positive for BPV1 through ddPCR, while qPCR failed to reveal this infection; ~ 44.1% (15/34) were positive for BPV2 when examined through ddPCR and ~ 11.7% (4/34) via qPCR; ~ 8.8% (3/34) were positive for BPV13 using ddPCR, while this infection was not detected with qPCR; ~ 35.3% (12/34) were positive for BPV14 by ddPCR and ~ 3% (1/34) by qPCR (Fig. 1). Considering a Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold of 1%, the BPV2 occurrence was shown to be significantly higher than that of both BPV1 and BPV13 occurrence (p < 0.001); BPV14 occurrence appeared to be significantly higher than that of BPV1 (p = 0.005) and BPV13 (p = 0.003). No significant differences were observed in the occurrence of BPV2 and BPV14. ddPCR revealed a single infection in 29 BPV-positive semen samples (83.5%). Dual BPV2/BPV14 infection was seen in two samples. Double infections caused by BPV1/BPV14 and BPV2/BPV13 were detected in two additional semen samples. Only one semen sample tested positive for a triple infection, comprising BPV1/BPV2/BPV13. However, the qPCR failed to detect multiple infections. Overall, BPV1 DNA showed a number of copies/μL ranging from 0.1 to 3.83. BPV2 DNA had a copy number/μL with a range from 0.13 to 4.18, while qPCR detected BPV2 DNA with a high (31.87 to 33.1) cycle threshold (CT) value, thus correlating ddPCR data. The copy number/μL of BPV13 DNA ranged between 0.21 and 4.18. The copy number/μL of BPV14 DNA ranged from 0.13 to 3.4, whereas qPCR detected only one positive sample corresponding to a cycle threshold of 33.34. The raw data obtained by ddPCR and qPCR is summarized in Supplemental Table S1. Figure 2 compares the qPCR cycle of quantification and the relative rain plots of ddPCR.

Fig. 1.

Percentages of single BPV genotype DNA detected by ddPCR. qPCR identified the DNA of two BPV genotypes, but did not reveal either BPV1 or BPV13 DNA. UL = undetectable levels.

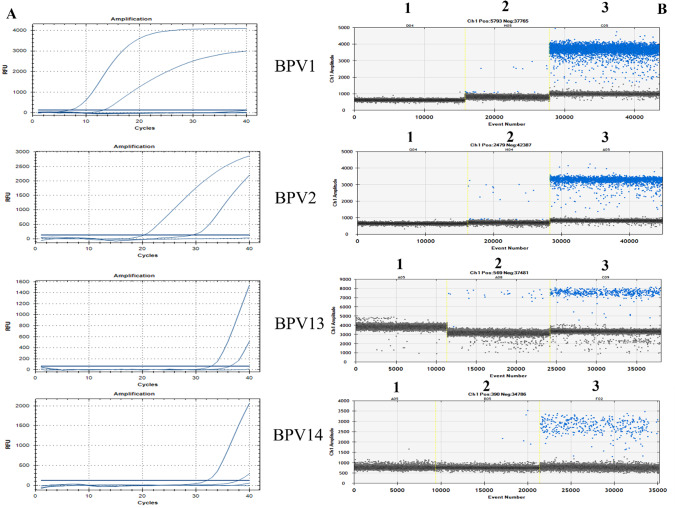

Fig. 2.

qPCR curves (A) and the relative rain plots of the ddPCR (B) for the four BPVs. QuantaSoft screenshots show the ddPCR results. Positive plots are represented in blue, whereas negative droplets are in grey. BPV1–D04(1): negative samples; H05(2): positive samples; and C05(3) is the positive control. BPV2–G04(1): negative samples; H04(2): positive samples; and A05(3) is the positive control. BPV13–A05(1): negative samples; A08(2): positive samples; and C09(3) is the positive control. BPV14–AO5(1): negative sample; B05(2): positive sample; and F02(3) is the positive control.

One-Step RT-ddPCR was performed on positive semen samples only. BPV1 mRNA was detected and quantified in 3 of 4 samples; its copy number per μL ranged from 0.18 to 0.23. BPV2 mRNA was detected and quantified in 6 of 15 samples its copy number/μL varying from 0.13 to 1.4. BPV14 transcripts were seen in 4 of 12 samples; its copy number/μL varied from 0.3 to 4.4. No BPV13 transcripts were detected in 3 samples.

ddPCR detected BPV1 DNA in two peripheral blood samples. One sample contained BPV1 transcripts too. BPV2 DNA was detected in 3 blood samples. In two of them, RT-ddPCR revealed BPV2 mRNA. BPV13 DNA was seen in one blood sample. BPV14 DNA and its transcripts were seen in two peripheral blood samples.

Discussion

Our study showed, for the first time, that bovine δPV DNA could be detected and quantified from both the fresh and thawed semen of healthy stallions using ddPCR. Numerous DNA-positive samples were found to contain E5 transcripts, which are markers of active BPV infection, indicating that our positive ddPCR results came from real semen infection, thereby refuting any contamination from the environment during semen collection. As such, it is conceivable that BPVs are shed into equine semen and spread in a manner similar to other viruses, including equid herpes virus34.

In the present study, we calculated the overall and type-specific frequency of occurrence of bovine δPV in the semen. The overall occurrence of bovine δPV DNA found through ddPCR was significantly higher in comparison to that detected using qPCR. BPV2 and BPV14 were the most frequently detected genotypes in the semen samples. Their actual occurrence was significantly higher than that of BPV1 and BPV13, which is consistent with the territorial differences in the distribution of BPV genotypes.

Our study is the first to report the presence of BPV14 and its transcripts in horses, suggesting that this genotype, in addition to BPV1, BPV2, and BPV13, may be an extra infectious pathogen in equine species. BPV14 transcripts does not seem to be associated with viral load as suggested for some PV infection38. BPV14 mRNA represent a marker of an active BPV14 infection, which shows that this genotype could be responsible for a cross-transmission and infection like other bovine δPVs. Our suggestions are consistent with previous studies showing that BPV14 infection can result in mesenchymal proliferation after cross-species infection39.

BPV14 nucleic acid detection and quantification were performed using ddPCR, a highly accurate method of PV detection. Conversely, qPCR failed to detect the viral load in many ddPCR-positive seminal samples similar to other viral diseases40. As such, the ddPCR assay may be an essential tool for improving diagnostic procedures, thereby allowing the identification of the genotypic distribution of BPV, a better understanding of the ecological diversity of BPV prevalence, and the possible geographical divergence of BPV prevalence in different areas.

Furthermore, our findings are consistent with the concept that sexual transmission could be an important route of BPV transmission, and that the occurrence of these viruses in the semen of asymptomatic stallions is a potential cause of concern. It is worth noting that the mechanism by which horses are infected with BPV leading to equine sarcoid is not fully understood. It has been suggested that infection can be from a direct contact with cattle or horses carrying BPV or through bites of a virus-carrying fly41.

Our findings suggest that bovine δPV occurrence is relevant in the semen of asymptomatic horses and are consistent with horses being a potential BPV reservoir, which raises the question about the importance of incorporating stallions in efforts to evaluate BPV infection before fertilization to reduce the potential incidence of BPV cross-species transmission and BPV-related disease in horses. Furthermore, making ddPCR available to clinical applications may give great advantages to correct diagnosis and effective treatment. The biological significance of bovine δPVs in semen of healthy stallions remains to be elucidated. Although PVs are basically known to be oncogenic viruses1, recent evidence suggest that PV infection can be implicated in male and female infertility as PVs could have a detrimental impact in sperm quality and reproductive outcomes29,30,42–45. Furthermore, it has been suggested that human papillomavirus (HPV) infection could be responsible for early pregnancy failure46,47, which is very likely because HPV infection is more common in early pregnancy compared with late pregnancy48. Furthermore, HPV infection can negatively impact maternal and fetal outcomes through abnormal placentation and placental function, as HPV targets placental trophoblast cells49. It is also worth noting that BPVs target placental trophoblastic cells, resulting in both abortive and productive placental infection50, which is associated with reproductive disorders in pregnant cows8,9. As such, genital BPV infection may lead to subfertility.

BPV1 infection was the only genotype detected in the cells of the reproductive tract of horses so far30. Our results related to all bovine δPVs represent a critical starting point for additional research to establish the reproductive prognosis of stallions with sperm BPV infection and better explain the role of seminal BPVs as risk factors for stallion fertility.

Although there has been a marked improvement in the per-season pregnancy rate in both thoroughbred and non-thoroughbred mares, reproductive disorders still have a significant impact on the equine breeding industry51,52. Although maternal factors have been recognized as important risk factors for reproductive problems, information on the importance of stallion factors in influencing the reproductive performance of mares is still lacking53,54. Therefore, more comprehensive studies are required to gain a true picture of the factors that most influence the fertility of commercial stallions, because the overall per-mating pregnancy rate for stallions is currently 59.6%55. However, the mechanism through which BPVs gain access to these sites remains unclear. In both asymptomatic men56 and horses57, the presence of PV DNA in semen may be associated with undiagnosed penile lesions. As such, we should not exclude the possibility that bovine δPVs in some semen samples from asymptomatic stallions may be associated with undiagnosed and/or misinterpreted penile lesions. However, we suggest that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) may be another important source of PV infection, and that bovine δPVs in equine semen may predominantly originate from the blood, as we have found transcriptionally active bovine δPVs in both the blood and semen of the same stallions with a strong concordance, which corroborates previous studies30 and strengthens the overall concept that the presence of bovine δPVs in equine semen is not solely local. It is worth noting that BPV1 DNA has been found in genital swabs from asymptomatic healthy horses58. Our findings were further corroborated by comparative studies. Indeed, it has been suggested that HPV in semen could originate from the blood, as transcriptionally active HPVs have been detected in peripheral blood leukocytes of men with HPV-positive seminal samples59. Notably, peripheral blood infected with expressed PV yields infections at permissive sites with detectable viral DNA, RNA transcripts, and proteins22,60.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study showed that BPV1, BPV2, BPV13, and BPV14 can be found in semen of apparently healthy stallions causing single and/or multiple infections. Bovine δPV RNA, as marker of an active infection, was detected and quantified using ddPCR tool, that appeared to be the most accurate and sensitive diagnostic method for detection BPVs. BPV2 and BPV14 were the most prevalent genotypes with highest copy number/μL in stallion semen.

Evidence suggests that PV infection could have a negative impact on reproductive health in both domestic animals and humans. Our findings provide a new perspective to better understand the epidemiology of BPVs in equine species. Future studies on bovine δPV infection in horses should be a priority for researchers, as this infection in horses as it may be an underestimate risk factor affecting equine reproductive efficiency. Understanding the causes and risks of equine pregnancy loss is essential for developing prevention and management strategies to reduce its occurrence and impact on the horse-breeding industry. Although infectious diseases are believed to represent the primary causes of equine reproductive disorders, it is worth noting that a definitive cause of equine pregnancy failure could not be established in as many as 70% of cases, and new diagnostic approaches are required to improve the likelihood of increasing the accuracy of diagnosis61.

Methods

Sample collection

We examined 58 equine semen samples, of which 43 were commercially available. An additional 15 semen and peripheral blood samples were collected from 15 stallions with no apparent signs of disease during clinical examination at the Didactic Veterinary University Hospital (DVUH) of Naples. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol PG/2024/0023599, Naples University Federico). Permission to collect samples was obtained from the animals’ owners.

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 58 semen samples as follows: 100 µl of sperm was placed in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and 100 µl of buffer called ‘X2’ (20 mM Tris–Cl (pH 8.0); 20 mM EDTA; 200 mM NaCl; 80 mM DTT; 4% SDS; 250 µg/ml Proteinase K) was added. The resulting mixture was heated to 55 °C until the sample dissolved (approx. 1 h). Subsequently, 200 µl of buffer AL from the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, 200 µl of 100% ethanol and Proteinase K (20 mg/ml) supplied with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Wilmington, DE, USA), were also added to each sample. Steps 5–8 of the Protocol for DNA extraction from tissues in the manual of the same kit were then performed. DNA was extracted from blood samples using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Wilmington, DE, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Droplet digital polymerase chain reaction (ddPCR)

For ddPCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), a QX200 ddPCR system was used following the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was performed in a final volume of 22 μL, consisting of 11 μL of ddPCR Supermix for Probes (2X; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), 0.9 μM primer, and 0.25 μM of probe with 7 μL sample DNA corresponding to 100 ng.

The primer and probe sequences for BPV (Table 1) and the tool used to generate droplets and thermal profiles have been described previously36. The droplets were detected using a Bio-Rad QX200 Droplet Reader. Data were analyzed to determine BPV types and copy numbers using QuantaSoft software version 1.4 (Bio-Rad). Manual thresholds were applied to both the BPV genotypes and positive controls, the latter of which included BPV-1 DNA from a zebra sarcoid (a kind gift provided by Dr. Altamura, University of Naples, Italy), BPV-2 clone DNA (a kind gift by Dr. A. Venuti, IRCSS Regina Elena, National Cancer Institute, Rome, Italy), and BPV-13 and BPV-14 DNA from bovine bladder tumors from our laboratories (Roperto, Russo, et al., 2016). A BPV-negative sample and non-template control were included in each run. The BPV concentration was finally expressed as the number of DNA copies per microliter of semen (copies/μl). Therefore, the PCR result could be directly converted into copies/μl in the initial samples simply by multiplying it with the total volume of the reaction mixture (22 μl) and subsequently dividing that number by the volume of DNA sample added to the reaction mixture (7 μl) at the beginning of the assay.

Table 1.

Primers and probes used to detect bovine δPVs in ddPCR and qPCR.

| Forward 5′ 3′ | Reverse 5′ 3′ | Probe | Region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPV1 | ACTTCTGATCACTGCCATT | ATAGAAACCATAGATTTGGCA | TGAAGTGTTTCTGTTTGTGA-FAM | ORF E5 |

| BPV2 | TACAGGTCTGCCCTTTTAAT | AACAGTAAACAAATCAAATCCA | AACAACAAAGCCAGTAACC-FAM | 3′UTR E5 |

| BPV13 | CTGTGTGGATTTGATTTGTT | CAGGGGGAATACAAATTCT | TGAAGTGTTTCTGTTTGTGA-FAM | 3′UTR E5 |

| BPV14 | CTTTGTTATTGTATATGAGTCTGT | ACTCTTGACGGTTTAAAAGTA | ATCTTGCCAGTGATCCTG-FAM | 3′UTR E5 |

Each sample was analyzed in duplicate to ensure accuracy. Samples were considered BPV-positive if at least three droplets containing BPV amplicons were present, as has been suggested for PV infections in human and veterinary medicine15,24,37. Furthermore, samples with < 20 positive droplets were re-analyzed to ensure that these low copy number samples were not caused by cross-contamination.

RNA extraction and one-step reverse transcription (RT)-ddPCR

RNA was extracted from the semen and blood samples of the same stallions using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. This kit contains genomic DNA (gDNA) eliminator spin columns. Subsequently, the One-Step RT ddPCR Advanced Kit for Probes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was applied to 100 ng of RNA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described24. A one-step reaction was performed on samples to which reverse transcriptase (RT) was added (RT+) and on those without RT (RT−).

Statistical analysis

The difference in prevalence detected by ddPCR and qPCR was tested using McNemar’s test. Additionally, among the samples identified as positive by ddPCR, the McNemar test was applied to perform the following five pairwise comparisons: BPV2 vs. BPV1, BPV 2 vs BPV 13, BPV2 vs BPV 14, BPV 14 vs BPV 1, and BPV 14 vs BPV 13. Bonferroni correction was further applied to adjust for statistical significance in multiple tests. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 17 software.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. G. Altamura, Department of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Productions, University of Naples Federico II, (Naples, Italy) and Dr. A. Venuti, IRCSS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, (Rome, Italy) for providing BPV1- and BPV-2-positive samples as a kind gift. Furthermore, we wish to thank Dr R. Casaroli from the Studio Veterinario Associato “Luretta”, Gazzola (PC), Dr Luigi D’Andrea from the Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale (ASP) of Caserta, Dr. B. Izzo from Azienda Sanitaria Locale (ASL) of Benevento and Dr Gerardo Paraggio private practitioner from Salerno for contributing in semen sampling, and Dr S. Morace, University of Catanzaro “Magna Graecia” for his technical assistance.

Author contributions

AC, FDF, SI, and FS; acquisition and analysis of the data; G.F. and C.C visualization and statistical analysis; S.R.: conceptualization, supervision, writing (original draft), writing (review & editing). All authors reviewed the results; they approved the final version of the manuscript and declared that the content has not been published elsewhere.

Funding

This work was partially supported by a grant of the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale del Mezzogiorno, Portici. The funder of the work did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Semen samples were commercially purchased. Some additional samples were collected at the Didactic Veterinary University Hospital (DVUH) of Naples. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol PG/2024/0023599, Naples University Federico II). Permission to collect samples was obtained from the animals’ owners.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81682-7.

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 90, Human Papillomaviruses, WHO, Lyon, France, 2007.

- 2.PaVE: The papillomavirus episteme available from http://pave.niaid.nih.gov (accessed on 31 August 2024).

- 3.Carvalho, T., Pinto, C. & Peleteiro, M. C. Urinary bladder lesions in bovine enzootic haematuria. J. Comp. Pathol.134, 336–346. 10.1016/j.jcpa.2006.01.001 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wosiaki, S. R., Claus, M. P., Alfieri, A. F. & Alfieri, A. A. Bovine papillomavirus type 2 detection in the urinary bladder of cattle with chronic enzootic haematuria. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz.101, 635–638. 10.1590/s0074-02762006000600009 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roperto, S. et al. A review of bovine urothelial tumours and tumour-like lesions of the urinary bladder. J. Comp. Pathol.142, 95–108. 10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.08.156 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daudt, C. et al. Papillomaviruses in ruminants: An update. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.65, 1381–1395. 10.1111/tbed.12868 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roperto, S. et al. Bovine papillomavirus type 13 expression in the urothelial bladder tumours of cattle. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.63, 628–634. 10.1111/tbed.12322 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roperto, S., Munday, J. S., Corrado, F., Goria, M. & Roperto, F. Detection of bovine papillomavirus type 14 DNA sequences in urinary bladder tumors in cattle. Vet. Microbiol.190, 1–4. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.04.007 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roperto, S. et al. Oral fibropapillomatosis and epidermal hyperplasia of the in newborn lambs associated with bovine Deltapapillomavirus. Sci. Rep.8, 13310. 10.1038/s41598-018-31529-9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roperto, S., Russo, V., De Falco, T., Taulescu, M. & Roperto, F. Congenital papillomavirus infection in cattle: Evidence for transplacental transmission. Vet. Microbiol.230, 95–100. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2019.01.019 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Falco, F., Cutarelli, A., Leonardi, L., Marcus, I. & Roperto, S. Vertical intrauterine bovine and ovine papillomavirus coinfection pregnant cows. Pathogens13, 453. 10.3390/pathogens13060453 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozkul, I. A. & Aydin, Y. Tumours of the urinary bladder in cattle and water buffalo in the Black Sea region of Turkey. Br. Vet. J.152, 473–475. 10.1016/s0007-1935(96)80041-8 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silvestre, O. et al. Bovine papillomavirus type 1 DNA and E5 oncoprotein expression in water buffalo fibropapillomas. Vet. Pathol.46, 636–641. 10.1354/vp.08-VP-0222-P-FL (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roperto, S. et al. Detection of bovine Deltapapillomavirus DNA in peripheral blood of healthy sheep (Ovis aries). Transbound. Emerg. Dis.65, 758–764. 10.1111/tbed.12800 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cutarelli, A., De Falco, F., Uleri, V., Buonavoglia, C. & Roperto, S. The diagnostic value of the droplet digital PCR for the detection of bovine Deltapapillomavirus in goats by liquid biopsy. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.68, 3624–3630. 10.1111/tbed.13971 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roperto, S., Cutarelli, A., Corrado, F., De Falco, F. & Buonavoglia, C. Detection and quantification of bovine papillomavirus DNA by digital droplet PCR in sheep blood. Sci. Rep.11, 10292. 10.1038/s41598-021-89782-4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lancaster, W. D., Olson, C. & Meinke, W. Bovine papilloma virus: Presence of virus-specific DNA sequences in naturally occurring equine tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA74, 524–528. 10.1073/pnas.74.2.524 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers, G. et al. Association of bovine papillomavirus with the equine sarcoid. J. Gen. Virol.8, 1055–1062. 10.1099/vir.0.18947-0 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jindra, C., Kamjunke, A. K., Jones, S. & Brandt, S. Screening for bovine papillomavirus type 13 (BPV13) in a European population of sarcoid-bearing equids. Equine Vet. J.54, 662–669. 10.1111/evj.13501 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munday, J. S., Orbell, G., Fairley, R. A., Hardcastle, M. & Vaatstra, B. Evidence from a series of 104 equine sarcoids suggests that most sarcoids in New Zealand are caused by bovine papillomavirus type 2 although both BPV1 and BPV2 DNA are detectable in around 10% of sarcoids. Animals11, 3093. 10.3390/ani11113093 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lunardi, M. et al. Bovine papillomavirus type 13 DNA in equine sarcoids. J. Clin. Microbiol.51, 2167–2171. 10.1128/JCM.00371-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Falco, F., Cutarelli, A., Pellicanò, R., Brandt, S. & Roperto, S. Molecular detection and quantification of ovine papillomavirus DNA in equine sarcoid. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.2024, 6453158. 10.1155/2024/6453158 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Falco, F. et al. Evidence of a novel cross-species transmission by ovine papillomaviruses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.69, 3850–3857. 10.1111/tbed.14756 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Falco, F. et al. Possible etiological association of ovine papillomaviruses with bladder tumors in cattle. Virus Res.328, 199084. 10.1016/j.virusres.2023.199084 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doorbar, J. The human Papillomavirus twilight zone—Latency, immune control and subclinical infection. Tumour Virus Res.16, 200268. 10.1016/j.tvr.2023.200268 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, H. et al. Application of droplet digital PCR to detect the pathogens of infectious diseases. Biosci. Rep.38, BSR20181170. 10.1042/BSR20181170 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Della Fera, A. N., Warburton, A., Coursey, T. L., Khurana, S. & McBride, A. A. Persistent human papillomavirus infection. Viruses13, 321. 10.3390/v13020321 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindsey, C. L. et al. Bovine papillomavirus DNA in milk, blood, urine, semen, and spermatozoa of bovine papillomavirus-infected animals. Genet. Mol. Res.8, 310–318. 10.4238/vol8-1gmr573 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva, M. A., Silva, E. C., Gurgel, A. P., Nascimento, K. C. & Freitas, A. C. Bovine papillomavirus E2 and E5 gene expression in sperm cells of healthy bulls. Virusdisease25, 125–128. 10.1007/s13337-013-0185-5 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva, M. A. et al. The presence and gene expression of bovine papillomavirus in the peripheral blood and semen of healthy horses. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.61, 329–333. 10.1111/tbed.12036 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong, P. et al. Abortion storm of Yili horses is associated with Equus caballus papillomavirus 2 variant infection. Arch. Microbiol.206, 5. 10.1007/s00203-023-03723-5 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cutarelli, A. et al. Molecular detection of transcriptionally active ovine papillomaviruses in commercial equine semen. Front. Vet. Sci.11, 1427370. 10.3389/fvets.2024.1427370 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruni, L. et al. Global and regional estimates of genital human papillomavirus prevalence among men; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health11, e1345-1362. 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00305-4 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sellers, R. F. Transmission of viruses by artificial breeding techniques: A review. J. R. Soc. Med.76, 772–775. 10.1177/014107688307600913 (1983). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biron, V. L. et al. Detection of human papillomavirus type 16 in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma using droplet digital polymerase chain reaction. Cancer122, 1544–1551. 10.1002/cncr.29976 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Falco, F., Corrado, F., Cutarelli, A., Leonardi, L. & Roperto, S. Digital droplet PCR for the detection and quantification of circulating bovine Deltapapillomavirus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis.68, 1345–1352. 10.1111/tbed.13795 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isaac, A. et al. Ultrasensitive detection of oncogenic human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal tissue swabs. J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg.46, 5. 10.1186/s40463-016-0177-8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacquin, E. et al. The level of expression of HPV16 early transcripts is not associated with the natural history of cervical lesions. J Med Virol.96, e29875. 10.1002/jmv.29875 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munday, J. S. et al. Genomic characterisation of the feline sarcoid-associated papillomavirus and proposed classification as Bos taurus papillomavirus type 14. Vet Microbiol.177, 289–295. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.03.019 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu, X. et al. Analytical comparisons of SARS-COV-2 detection by qRT-PCR and ddPCR with multiple primer/probe sets. Emerg. Microbes Infect.9, 1175–1179. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1772679 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogłuszka, M., Starzyńki, R. R., Pierzchała, M., Otrocka-Domagała, I. & Raś, A. Equine sarcoids—Causes, molecular changes, and clinicopathologic features: A review. Vet. Pathol.58, 472–482. 10.1177/0300985820985114 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva, M. A. R., Pontes, N. E., Da Silva, K. M. G., Guerra, M. M. P. & Freitas, A. C. Detection of bovine papillomavirus type 2 DNA in commercial frozen semen of bulls (Bos taurus). Anim. Reprod. Sci.129, 146–151. 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2011.11.005 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lyu, Z. et al. Human papillomavirus in semen and the risk for male infertility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis.17, 714. 10.1186/s12879-017-2812-z (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moreno-Sepulveda, J. & Rajmil, O. Seminal human papillomavirus infection and reproduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Andrology9, 478–502. 10.1111/andr.12948 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busnelli, A. et al. Sperm human papillomavirus infection and risk of idiopathic recurrent pregnancy loss: Insights from a multicenter case-control study. Fertil. Steril.119, 410–418. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2022.12.002 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chilaka, V. N. et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) in pregnancy—An update. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol.264, 340–348. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.07.053 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sucato, A. et al. Human papillomavirus and male infertility: What do we know?. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 17562. 10.3390/ijms242417562 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Værnesbranden, M. R. et al. Maternal human papillomavirus at mid-pregnancy and delivery in a Scandinavian mother-child study. Intern. J. Infect. Dis.108, 574–581. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.05.064 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ambühl, L. M. M. et al. Human papillomavirus infects placental trophoblast and Hofbauer cells, but appears not to play a causal role in miscarriage and preterm labor. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand.96, 1188–1196. 10.1111/aogs.13190 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roperto, S. et al. Productive infection of bovine papillomavirus type 2 in the placenta of pregnant cows affected with urinary bladder tumors. PLoS One7, e33569. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033569 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Allen, W. R. & Wilsher, S. Half a century of equine reproduction research and application: A veterinary tour de force. Equine Vet. J.50, 10–21. 10.1111/evj.12762 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macleay, C. M. et al. A scoping review of the global distribution of causes and syndromes associated with mid- to late-term pregnancy loss in horses between 1960 and 2020. Vet. Sci.9, 186. 10.3390/vetsci9040186 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Mestre, A. M., Rose, B. V., Chang, Y. M., Wathes, D. C. & Verheyen, K. L. P. Multivariable analysis to determine risk factors associated with early pregnancy loss in thoroughbred broodmares. Theriogenology124, 18–23. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.10.008 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hanlon, D. W., Stevenson, M., Evans, M. J. & Firth, E. C. Reproductive performance of thoroughbred mares in the Waikato region of New Zealand: 2. Multivariable analyses and sources of variation at the mare, stallion and stud farm level. N. Z. Vet. J.60, 335–343. 10.1080/00480169.2012.696240 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allen, W. R. & Wilsher, S. The influence of mare numbers, ejaculation frequency and month on the fertility of Thoroughbred stallions. Equine Vet. J.44, 535–541. 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00525.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luttmer, R. et al. Presence of human papillomavirus in semen of healthy men is firmly associated with HPV infections of the penile epithelium. Fertil. Steril.104, 838-844.e8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.028 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li, C. X. et al. Identification of a novel equine papillomavirus in semen from a thoroughbred stallion with a penile lesions. Viruses11, 713. 10.3390/v11080713 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kanat, Ӧ et al. Equine and bovine papillomaviruses from Turkish brood horses: a molecular identification and immunohistochemical study. Vet. Arhiv89, 601–611. 10.24099/vet.arhiv.0507 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Foresta, C. et al. Human papillomavirus proteins are found in peripheral blood and semen Cd20+ and Cd56+ cells during HPV-16 semen infection. BMC Infect. Dis.13, 593. 10.1186/1471-2334-13-593 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cladel, N. M. et al. Papillomavirus can be transmitted through the blood and produce infections in blood recipients: Evidence from two animal models. Emerg. Microbes Infect.8, 1108–1121. 10.1080/22221751.2019.1637072 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cantόn, G. J. et al. Equine abortion and stillbirth in California: A review of 1,774 cases received at a diagnostic laboratory, 1990–2022. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest.35, 153–162. 10.1177/10406387231152788 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.