Abstract

The electronic health record (EHR) should contain information to support culturally responsive care and research, however, the widely used default “Asian” demographic variable in most US social systems (including EHRs) lacks information to describe the diverse experience within the Asian diaspora (e.g., ethnicities, languages). This has a downstream effect on research, identifying disparities, and addressing health equity. We were particularly interested in EHRs of autistic patients from the Asian diaspora, since the presence of a developmental diagnosis might call for culturally responsive care around understanding causes, treatments, and services to support good outcomes. The aim of this study is to determine the degree to which information about Asian ethnicity, languages, and culture is documented and accessible in the EHR, and whether it is differentially available for patients with or without autism. Using electronic and manual medical chart review, all autistic and “Asian” children (Group 1; n=52) were compared to a randomly selected comparison sample of non-autistic and “Asian” children (Group 2; n=50). Across both groups, manual chart review identified more specific approximations of racial/ethnic backgrounds in 54.5% of patients, 56% for languages spoken, and that interpretation service use was underestimated by 13 percentage points. Our preliminary results highlight that culturally responsive information was inconsistent, missing, or located in progress notes rather than a central location where it could be accessed by providers. Recommendations about the inclusion of Asian ethnicity and language data are provided to potentially enhance cultural responsiveness and support better outcomes for families with an autistic child.

Keywords: Culturally response care, Asian Diaspora, Autism, health equity, healthcare practices, electronic health record

Introduction

Individuals with intersecting marginalized identities – racial and ethnic minority, limited English proficiency, and disability – can experience reduced health outcomes, quality of life, and life expectancy because of multiplicative disparities in care [1]. In the United States, the Asian diaspora has been consistently excluded from specific consideration in research on disparities [2], from studies of autism generally [3], and from grant mechanisms to support health and clinical research [4]. Two interactive reasons for this are that Asian subgroups are often small and thus excluded due to limited statistical power, and because of a longstanding anti-Asian narrative of the model minority stereotype (MMS) that might suggest “Asians” do not experience disparities. In the United States, the MMS erroneously describes “Asians” as a monolithic group and paints a misleading picture that all “Asians” are successful in life compared to other minoritized ethnic groups, and thus do not need attention related to health equity [5]. Such exclusionary practices make it impossible to see and thus address the specific health concerns and needs of this community.

The first step to dispel the MMS Asian diaspora as a monolithic group is to understand –and ultimately have systems reflect – the vast diversity of this population. Comprising 6.2% of the U.S. population, the Asian diaspora is the fastest growing immigrant group in the U.S. [6] and predicted to be the largest U.S. immigrant community in 2065 [7]. As of 2023, there are 2,300 known languages spoken, 48 countries, and 4.7 billion people within the region of Asia [8]. In the US, the majority of families within the Asian diaspora are multilingual (77%) compared to other racial minority groups, with about 33% of the population speaking a language other than English as their first language [9].

During data collection for this study, the Statistical Policy Directive No. 15 (SPD 15) provided updated standards for recording, maintaining, and presenting race/ethnicity data for federal agencies, including the Census Bureau were published by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on March 28, 2024 [38]. Some of the notable changes included the improvements in terminology used in describing different race/ethnicity categories, including the new “Middle Eastern or North African” (MENA) category, and the function to select multiple checkboxes for respondents who identify as multiracial and multiethnic. Based on the updated SPD 15, “Asian” is one of the seven minimum race/ethnicity reporting categories and includes “individuals with origins in any of the original peoples of Central or East Asia, Southeast Asia, or South Asia, including, for example, Chinese, Asian Indian, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese”. Despite the vast diversity in ethnicity, cultural practices, and preferred languages used within the U.S. Asian diaspora, “Asian” is still a single category in this new SPD 15. In fact, people from the Asian diaspora often prefer to identify based on their ethnic heritage. In the 2016 National Asian American Survey, only 16% identified as Asian American while almost 70% identified based on their specific ethnic groups [10]. Hence, it is not surprising that 90% of Asian Americans do not see themselves as a monolithic group but rather a diverse group of cultures from varied ethnic groups [11].

We aimed to understand how to better support culturally responsive care and research by examining what ethnicity and language information is available and accessible in our healthcare system’s electronic health records (EHR). The EHR centralizes the operations of hospital care and supports continuity of care across multiple departments (e.g., primary care, neurology, behavioral health, etc.). Given this role of the EHR, we reviewed both the content (available information) and the process (how easy or challenging it is to locate) for acquiring relevant information about Asian ethnicity and language use. We also compared information for patients with and without an autism diagnosis, since there are important opportunities for culturally responsive care in the screening, diagnosis, and ongoing management of a developmental diagnosis like autism across the lifespan. We also acknowledge that the information obtained regarding racial/ethnic backgrounds are approximations of patient identities based on EHR data and could be inaccurate. The study goals were to explore how our current EHR system reports demographic information for patients from the Asian diaspora, and how easy or difficult is to find it the EHR at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). Findings could inform health disparity reduction efforts for autistic children and families with other intersecting multiple marginalized backgrounds.

Methods

Demographic options in the EHR

At the beginning of the study, options for “Race” in the Demographics Tab of CHOP’S EPIC based EHR included: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Asked but unknown, Black or African American, Choose Not to Disclose, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Other, Unknown, and White. Options for ethnicity included: Refused, Hispanic or Latino, Non-Hispanic or Non-Latino, Other, Unknown, Asked but Unknown, and Choose Not to Disclose. Multiple races and ethnicities can be selected. During the study period, Indian (i.e., representing those with heritage from South Asia and the subcontinent Indian), was added as a specific option within “Race” and will be discussed in more detail below. For language(s), Preferred Language, Spoken Language, and Written Language are sections available to indicate patient language information. Options for Interpreter Use (i.e., use of hospital-provided language services for interpretation at a medical appointment) included: Interpreter Needed, Interpreter Not Needed, and Not Indicated.

Participants

Participants were drawn from the 25,999 children who presented at least once for a well-child visit between 16 and 26 months of age at a CHOP primary care site between 2011 and 2015 and again after 4 years of age. This cohort was drawn from two previous studies utilizing EHR data to examine the accuracy of universal screening for autism in primary care and autism prevalence within a large pediatric network (CHOP) [12-13]. 1109 of the 25,999 children were recorded as “Asian” in the EHR’s demographic tab (“Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” was not included in this sample, and “Indian” was not yet available as a variable). Of the 1109, 55 also met our study definition of autism having either 1) at least two entries of autism associated with a visit diagnosis and/or the problem list, or 2) an autism diagnosis made by an autism specialist (e.g., Licensed Psychologist, Developmental Pediatrician). For the comparison group, 50 from the remaining 1054 without an autism diagnosis documented were randomly selected. Separately, as a result of our manual chart review, four cases from the autism group were removed because no documentation of a formal autism diagnosis, including an educational diagnosis, was ascertained other than the mentioning of some autism concerns in the chart. Additionally, one case was moved from the comparison group to the autism group because an autism diagnosis had been recently made. Thus, one additional child was added to the comparison sample to replace the n=1 moved to the autism group. The final sample sizes were Autism (n=52), and Comparison (n=50). Additionally, during the period of manual chart review, 26 of the 102 patients had updated their EHR “Race” category to either “Indian” (n=23) or “Other” (n=3). A waiver of consent was obtained to mitigate selection bias if consent was required from the families.

Procedures

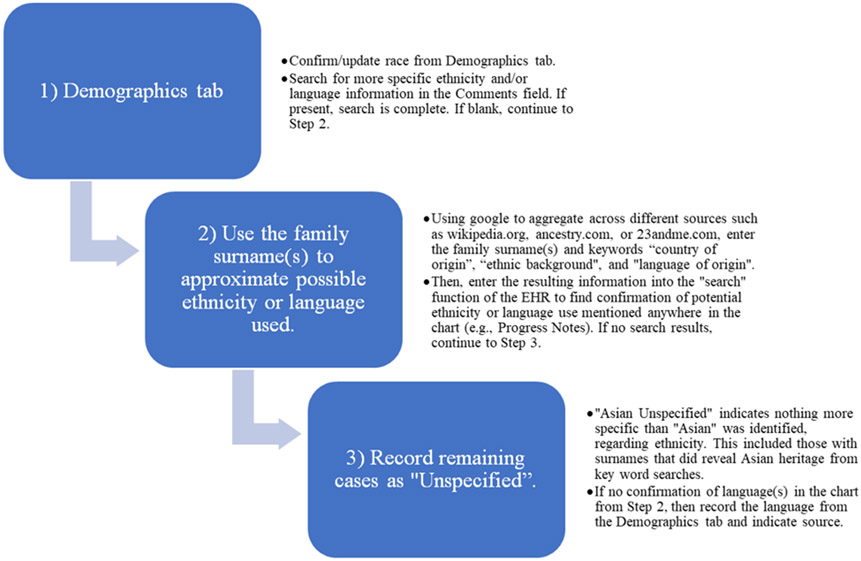

Data were abstracted both electronically and manually. Electronic abstraction included the following structured data fields from the EHR: Race/Ethnicity from the Demographics tab, Language information from the Demographics tab (Preferred, Written, and Spoken language used), Interpreter needed, age, sex assigned at birth, and insurance type (Medicaid, private insurer). Manual abstraction included information about any specific ethnicities, languages, or actual use of Interpreter Services found in the Comments fields of the Demographic tabs, or from progress notes, telephone/message encounters, and external records (e.g., school records). Descriptive notes were recorded to comprehensively represent any information available. The source of the information (i.e., progress notes, encounters tab, media tab, etc.) was also recorded. Figure 1 details our process of manual abstraction for ethnicity and language information. Within our autism sample, we also manually abstracted the earliest date of a documented autism diagnosis as a variable to determine if our Asian ethnicity autism sample was similar to or different from autistic patients nationally. For this, we used a standardized record review process developed for the entire published cohort [14].

Figure 1: Manual Abstraction Procedures.

Note. Language and Ethnicity were recorded as separate variables. The child’s surname/last name was used as the start of the search for any approximation of ethnicity and/or language(s) used (Step 2). Cases that were categorized as “Unspecified” if no information in the medical chart that can confirm the approximation of possible ethnicity (Step 3).

The manual chart reviews were conducted by three reviewers (MC, MRP, and ZW) with backgrounds in clinical research who were trained by two autism researchers and clinicians (JM and DT) with clinical experience reviewing patient charts to identify relevant information in the EPIC-based EHR. Data were abstracted into a REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database [15] hosted at CHOP. The research team collaboratively developed a manual chart review procedure to assist in the identification of noted demographic information using key words to search the patients’ charts (Figure 1):

Results

Manual chart reviews for demographic information alone took between 3-20 minutes per record. Our autism (n=52) and comparison groups (n=50) had similar mean age and insurance type (Table 1). The proportion of males to females for the autism group was 71%:29% (in line with identified higher ratios of autistic males), and the comparison group was 52%:48%; however, differences were not found to be statistically significant (p>0.05). The median age at first documented autism diagnosis was 3.6 years old, with most children getting the diagnosis around 3 years old (32.7%). This finding is similar to recent autism prevalence literature [16-17], suggesting our autistic Asian patients are similar to patients nationally. The proportion of unspecified ethnicities and languages in the autism and comparison groups were not statistically different (p>0.05), and therefore results were combined when reporting ethnicity and language variables.

Table 1.

Group Demographic and Clinical Information

| Group Demographics |

Autism (n=52) |

Comparison (n=50) |

Statistical Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 11.5 (0.9) | 11.7 (1.0) | t(100) = 1.0, p = 0.32 |

| Sex (M, F) | 37 (71%), 15 (29%) | 26 (52%), 24 (48%) | χ2 = 0.05, p = 0.83 |

| Insurance Type | χ2 = 0.74, p = 0.69 | ||

| Private | 31 (60%) | 27 (54%) | |

| Medicaid | 20 (38%) | 21 (42%) | |

| Unknown/None | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) |

Interrater reliability: Multiple reviewers completed independent record reviews on 10% of the charts (n=10, 5 for each group). Percent agreement was calculated for interrater reliability across three reviewers. Raters reached 100% agreement (n=5 of 5) when determining date of first autism diagnosis, and 90% agreement (n=9 of 10) on Asian ethnicity, preferred language, and actual use of interpreter services.

Table 2 displays the Race variable from the Demographics tab against the approximations of Asian ethnicities (i.e., provider-documented ethnicity) obtained from manual chart review. After accounting for families who had been updated from “Asian” to either “Indian” or “Other” (most likely during a healthcare visit that occurred after our data pull), reviewers found additional, more specific Asian ethnic information for 54.5% of families (n=42 of 77). The most common location for additional Asian ethnic information was a progress note where a provider specifically noted the family’s ethnicity or country of origin (n=39). Other sources included: nursing notes (n=3), and adoption records (n=1).

Table 2.

Asian ethnicity information identified electronic v. manual chart review

| Races Listed in Demographics tab (n, %) |

Ethnicities Identified Using Manual Chart Review (n, %) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Asian | 71 (69.6%) | Bangladeshi | 1 (0.98%) |

| Cambodian | 2 (1.96%) | ||

| Chinese | 5 (4.90%) | ||

| Indian | 4 (3.92%) | ||

| Indonesian | 4 (3.92%) | ||

| Japanese | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Korean | 7 (6.86%) | ||

| Multiracial | 2 (1.96%) | ||

| Moroccan | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Multiethnic | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Unspecified | 33 (32.35%) | ||

| Vietnamese | 10 (9.80%) | ||

| Asian & Other | 1 (0.98%) | Unspecified | 1 (0.98%) |

| Asian & White | 4 (3.92%) | Multiracial | 3 (2.94%) |

| Unspecified | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Indian | 23 (22.55%) | Indian | 23 (22.55%) |

| Other | 3 (2.94%) | Korean | 1 (0.98%) |

| Pakistani | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Yemen | 1 (0.98%) | ||

| Total Unspecified | 35 (34.31%) | ||

With regard to languages used, we found more than half of the charts (n=57 of 102, 56%) had additional, or even discrepant, information between what was in the Demographics tab and what was noted in the chart (Table 3). A key discrepancy was around use of interpretation services, with the Demographics tab suggesting 5 families needed interpretation services, but manual chart reviewing finding documented use of interpretation services for 18 families. Table 3 details language information noted under the Demographic tab and 19 specific non-English languages found through manual chart review.

Table 3.

Language information available in the EHR Demographics tab v. manual chart review

| Language Information from the Demographics Tab (n=102, % Total) |

Language Information found Using Manual Abstraction (n=57, 56% of Total) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred Language | Written Language | Spoken Language | Arabic | 1 | |

| English Only | 86 | 92 | 86 | Bangla | 1 |

| English Primary | 0 | 0 | 6 | Bengali | 1 |

| English Secondary | 0 | 0 | 6 | Cambodian | 5 |

| Non-English Language Only | 7 | 7 | 2 | Cantonese | 3 |

| Not Indicated | 9 | 3 | 2 | Hindi | 2 |

| Indonesian | 9 | ||||

| Indian Language (Unspecified) | 1 | ||||

| Japanese | 1 | ||||

| Kannada | 1 | ||||

| Korean | 3 | ||||

| Malayalam | 1 | ||||

| Mandarin | 3 | ||||

| Russian | 1 | ||||

| Tagalog | 1 | ||||

| Tamil | 3 | ||||

| Telugu | 3 | ||||

| Urdu | 2 | ||||

| Vietnamese | 8 | ||||

| Multiple Non-English Languages | 7 | ||||

| Interpreter Needed | No Interpreter Needed | Not Indicated | Indication of Interpreter Utilized | 18 | |

| Interpreter Use | 5 | 52 | 45 | ||

Note. The name of the non-English language was included whenever it was mentioned at least once in the chart. However, there was not enough information to determine whether the noted language was preferred or spoken by the family, or just by the child.

Discussion

The current President of the United States (U.S.), Joseph R. Biden Jr., published Executive Order 14091 [18] in February 2023 which strengthens the requirements of providing culturally and linguistically responsive care for federal agencies, as the Office recognizes the primary path to achieve health equity for marginalized communities is through providing culturally and linguistically responsive care. Relatedly, the 2013 National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health [19] recommended including the following: cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other needs for effective communication as part of CLAS for healthcare providers and organizations.

Demographic information in the EHR is crucial for providing culturally responsive healthcare, but only if it is present, self-reported, accessible, and specific enough to be informative. The US’s tradition of reducing the global community to ~5-7 racial and ethnic groups used for national reporting requirements is insufficient for supporting culturally responsive care in healthcare encounters. Thus, we set out to determine how easy or difficult it was to locate the more specific and detailed information about patients from the Asian diaspora that might inform and support culturally responsive care across all providers, particularly for autistic patients and families, who need multi-disciplinary care.

Ethnicity and Cultural Backgrounds

We found that manually finding more specific approximations of ethnicity and language information was time-consuming and difficult. With our systematic approach (Figure 1), we found helpful cultural and ethnic information outside of the Demographics tab for at least 43% of our “Asian” families. This means culturally relevant information was being shared during healthcare encounters, and that providers thought it was important enough to document but was being primarily stored in progress notes rather than an accessible and central location for all providers. As such, our findings on more specified ethnicity and language information are likely direct reports from patients but documented based on the provider’s perspectives, emphasizing the need for clear and representative patient-reported demographic forms.

When the sample’s ethnic information was extracted and tabulated based on all available information (electronic and manual reviews), ethnic identities across at least four major regions of the Asia continent were represented (South, East, Southeast, and West Asia) [20]. This level of diversity necessitates family-specific conversations about culturally relevant information, such as spoken heritage language(s); cultural family and healthcare practices; and families’ cultural perceptions of autism, developmental, and other health concerns. Our chart review also showed two medical charts who had the “Asian” category selected in the Demographics tab in our hospital’s EHR system had the possible national origins from Morocco and Yemen (Table 2). This observation could mean that there were potential data entry errors during paperwork completion. Nevertheless, it could also indicate that the families view “Asian” as a more accurate and appropriate representation of their racial/ethnic identity when the remaining options were unequipped and inaccurate. This specific finding yet once again emphasizes the importance of increasing open-endedness in collecting race/ethnicity data to promote autonomy and inclusivity in how respondents wish to identify and report. As an example, SPD 15 suggested guidelines for including features of selecting multiple checkboxes and write-in options when possible [38]. Indeed, the need to develop mechanisms that promote meaningful self-reported demographic documentation is critical for health disparity research, as numbers could be skewed by incorrect categorization.

Spoken and Written Language(s)

National Standards of CLAS (2013) highlighted the importance of integrating patients’ preferred language(s) in providing CLAS. Identifying the range of a family’s spoken and/or written language(s) is important in providing high quality and ethical care for both autistic children and families from this diaspora. In this sample, 56% of languages indicated from chart review did not match what was listed in the Demographics Tab (Table 3). Such mismatching information in a patient’s medical chart can have both clinical and ethical implications for autism families within the US Asian diaspora. The need to prioritize linguistically responsive care can ensure families have access to effective communication methods. Indeed, providing effective communication is essential in promoting health literacy and health equity for the marginalized Asian diaspora [21-22].

Some patient charts indicated unspecified languages from a certain region in Asia, with the potential to inaccurately reflect family languages and perpetuate stereotypes. For example, “Indian dialect” was noted as a type of spoken language, despite India having many major languages (e.g., Urdu or Telegu) and “Indian dialect” has never been recorded as a type of spoken or written language. This suggests the hospital staff may not have been able (or did not take the time) to ask and document the correct language, and/or that care team members do not reliably update it in the Demographics tab during subsequent interactions. This suggests that the current use of the Demographics tab does not sufficiently support documentation of accurate and culturally responsive information. However, it certainly could do so. Better design and use of the EHR for this purpose could support the ethical and safety concerns for multilingual patients outlined in the National CLAS Standards [19]. Additionally, it is important for clinicians and staff to receive training on the importance of and method for improving documentation in the EHR.

Implications for Culturally and Linguistically Affirming Practices

Making it easier for the entire care team to learn about and acknowledge a family’s Asian ethnic identities is the first crucial step towards practicing person- and family-centered approaches to patients from the Asian diaspora. As some initial examples, Table 4 includes some of ways in which specific Asian ethnicity and language information can inform care.

Table 4.

How Asian ethnicity and language information may be clinically relevant.

| Missing Demographic Information |

Description |

|---|---|

| Primary information | |

| Ethnicity | Gathering ethnic identities of a family can serve two purposes. First, it can support a culturally responsive discussion of the family’s understanding of autism, disability, and health-related behaviors (e.g., treatment choices) that may be influenced by ethnically specific cultural beliefs. Second, it can provide critical data for institutional- and population-level health equity research and policies. |

| Preferred Language(s) | Collectivism is integral in many Asian families, and extended family members often play a critical role in healthcare decisions for the child. Acknowledging the multigenerational component within family dynamics may require attending to an extended family composition that is multiracial, multiethnic, and multilingual. Identifying the preferred spoken and written language of the parents as well as other caretakers the parents identify as important (e.g., maternal grandmother, paternal uncle) can facilitate continuity of care when different family members are involved in the child’s care. |

| Secondary Information | |

| Families’ Perceptions of Autism and Related Developmental Concerns | Treatment decisions can be strongly associated with perceptions of autism. Knowing the family’s cultural perceptions of autism may facilitate effective family-professional communication and collaborative healthcare decision-making. Cultural perceptions of autism, stigma, and beliefs about cause can impact parental emotional wellbeing positively and/or negatively23. Incorporating traditional healing methods is also common in Asian cultures24. Cultural perceptions of skill attainment (e.g., higher education, speaking multiple home languages, living independently with family members) can play a critical role in how a family makes sense of the diagnosis and follows through with recommendations and referrals. Co-occurring conditions (e.g., ADHD, language disorders, intellectual disability, epilepsy, anxiety) may not be immediately understood as part of the clinical complexity and need for multiple interventions. It is important to note that this discussion may happen in more than one session and warrant an ongoing check-in with the families. |

| Families’ Understanding and Perceptions of their consumers’ rights in seeking different services and treatments | Ongoing discussions with the family regarding their knowledge of the U.S. autism care system can foster self-empowerment in families within the Asian diaspora. The intersectional experience of how the U.S. Asian diaspora is racialized (MMS) and the collectivistic cultural values (e.g., respect for authority of the healthcare professionals, stigma of disability) may combine to create barriers to care. For example, if a provider assumes Asian families are well educated and acculturated, and the family’s silence or deference is misconstrued as agreement or understanding, the family may not have the information they need for their child. Health information in multiple languages can help ensure parents fully understand the healthcare information. Providers can foster the family’s sense of self-empowerment by sharing with them their rights as patients in the healthcare system, and their rights across different service settings (e.g., schools, state-level social service programs). Specifically, providers can do so by explaining the information in a culturally and language responsive way (sometimes referred to as being a health knowledge broker). Relatedly, providers may consider acting as an advocate directly, by offering to consult with other relevant providers in the child’s care system to explain test results, diagnoses, and treatment/service recommendations. |

Applying an intersectional lens [34] as a conceptual framework is essential for developing culturally and linguistically responsive care [19]. Widely used intersectionality frameworks of ADDRESSING [25] and RESPECTFUL [26] recognize how ethnicity and languages are closely linked to other aspects of a person’s identity and experience including languages, cultural values, spiritual practices, and perceptions of health, healthcare practices, and parenting practices.

Through the social justice lens, prioritizing culturally and linguistically responsive care can achieve both health and social equity, particularly for the U.S. Asian diaspora [35]. This is because for generations, the U.S. Asian diaspora has been subjected to many forms of structural oppressions including forced acculturation [27] and systematic erasure of their multicultural identities and experiences in America [28]. In a healthcare setting, this may include the simple genuine expression of respect and humility by providers towards the family’s multicultural behaviors (e.g., asking if the family can teach the terms the provider has missed) and multicultural practices (e.g., encouraging the family’s choice of prioritizing the teaching of their heritage language[s]). These examples are simple but necessary for building a trustworthy, respectful, and most importantly, safe patient/family-provider and organization partnership. Such partnership is essential to sustain patient’s/family’s ongoing engagement with clinical care and to provide opportunities to promote family-centered outcomes for this marginalized community. Therefore, providing culturally and linguistically responsive care are the beginning and critical steps toward achieving health equity and social justice and gradually resisting against systemic oppressions for the children, families, and future generations of the U.S. Asian diaspora.

Research Implications

Searchable data fields have major implications for data recording and reporting. Data from EHRs is increasingly relied upon for studying autism prevalence, identification, outcomes, and disparities [29]. This increasing reliance continues to highlight the ongoing call to action to fix and improve the erroneous data recording method for the U.S. Asian diaspora, as it misconstrues the social and health experience of this community [5, 30], impacts public health policies [31-32], and undoubtedly is a civil rights violation as it systemically perpetuates anti-Asian marginalization [33]. Our manual chart review extends this finding to show that for our patients from the Asian diaspora, the electronically searchable demographic variables in the EHR were so limited, incomplete, or discrepant from information found in progress notes that it rendered the Demographics tab almost irrelevant. But it does not need to remain this way. Electronic platforms such as EPIC can also make it easy to gather more granular responses. Specifically for the Asian Diaspora, centering the practice of data disaggregation with intention is a first step toward dismantling the ongoing anti-Asian MMS; illuminating the incredible diversity of cultures, languages, and strengths; and supporting families’ rights to ethical healthcare and autism services [37].

Limitations and Future Directions

It’s likely that families who would fit under the “Asian” category were not recorded as such in our EHR. It’s also likely some relevant ethnicity and language information is missing in our manual searches, especially directly self-reported ethnic backgrounds. Furthermore, as a record review study, we could not contact families for any clarifications. Thus, our results are likely an underestimate of the amount of demographic information that could be improved upon in the EHR for this population. While some may also find the sample size to be a limitation, it represents nearly the entire “Asian” group within a cohort of 25,999. If we as researchers continuously devalue studies from the Asian diaspora because of “small” sample sizes, we will perpetuate the systematic erasure of the experiences of this population from research. Additionally, the study’s inclusion criteria was limited to clear documentation of an autism diagnosis and was often provided by clinicians within the hospital system who could clearly document this. As a result, the included sample is likely skewed with the exclusion of cases where a diagnosis was made outside of the hospital system (e.g., school setting, research center, etc.).

Future directions could include more research into families’ and providers’ perspectives about what information would be feasible, acceptable, and helpful to have in a centralized location in the EHR. Additionally, how to use EHR design and human factors engineering to make accessing, updating, and incorporating relevant cultural information into clinical care easier and better.

Conclusion

The lack of data in the EHR system exposes a gap in documentation of Asian ethnicity and language information needed for culturally responsive care. Having an autism diagnosis did not impact the presence or accessibility of demographic information. By having more clear and accessible demographics that accurately represent the vast diversity and the multicultural experience of the U.S. Asian Diaspora, we can begin to quantify disparities and implement culturally responsive care methods, all of which will enhance the subsequent care and services received. This is particularly important for a diagnosis like autism or other developmental delays, where empowering families to support their children is critical.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the network of primary care clinicians, their patients, and families for their contribution to this project and clinical research facilitated through the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Funding

This work was supported by the Allerton Foundation, NIMH R03MH116356.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest/Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Review Board approved a waiver of consent to mitigate selection bias if consent were required.

References

- 1.Singh JS, Bunyak G. Autism Disparities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Ethnography of Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research. 2019;29(6):796–808. doi: 10.1177/1049732318808245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Kind AJH. A scoping review of health disparities in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47:3380–3391. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3251-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mire SS, Truong DM, Sakyi GJ, Ayala-Brittain ML, Boykin JD, Stewart CM, Daniels F, et al. A Systematic Review of Recruiting and Retaining Sociodemographically Diverse Families in Neurodevelopmental Research Studies. J Autism Dev Disord. 2023;1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Đoàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KLK, Irvin VL. Trends in clinical research including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander participants funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7)e197432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JY, Block CJ, Yu H. Debunking the 'model minority' myth: How positive attitudes toward Asian Americans influence perceptions of racial microaggressions. J Vocat Behav. 2021;131:103648. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pew Research Center. Key facts about Asian Americans. Published April 29, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-americans/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Research Center. Future immigration will change the face of America by 2065. Published October 5, 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/10/05/future-immigration-will-change-the-face-of-america-by-2065/ [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Probabilistic Population Projections for China. In: World Population Prospects 2019. United Nations. 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/Graphs/Probabilistic/POP/TOT/935. Accessed 26 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johns Hopkins Medicine. National Asian Pacific Islander American Heritage month. Published 2020. Retrieved May 7, 2023, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/diversity/_documents/asian-american-pacific-islander-heritage-guide.pdf

- 10.AAPI Data. Asian American Identity. Retrieved November 15, 2023, from https://aapidata.com/blog/asian-american-identity/

- 11.Pew Research Center Race and Ethnicity. Diverse Cultures and Shared Experiences Shape Asian American Identities. Published May 8, 2023. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2023/05/08/diverse-cultures-and-shared-experiences-shape-asian-american-identities/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guthrie W, Wallis K, Bennett A, Brooks E, Dudley J, Gerdes M, Pandey J, Levy SE, Schultz RT, Miller JS. Accuracy of autism screening in a large pediatric network. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallis KE, Adebajo T, Bennett AE, Drye M, Gerdes M, Miller JS, Guthrie W. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in a large pediatric primary care network. Autism. 2023:13623613221147396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong ZM, Bennett A, Dowd L, Dudley J, Gerdes M, Guthrie W, Schoenberg M, Wallis KE, Miller JS. It’s Time to Improve and Systematize How We Document Autism Care in Our Medical Records (in preparation). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009. Apr;42(2):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The racial and ethnic gap in children identified with autism spectrum disorder: A brief on new data. Published 2023. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm-community-report/spotlight-on-closing-racial-gaps.html

- 17.Pham AV, Charles LC. Racial Disparities in Autism Diagnosis, Assessment, and Intervention among Minoritized Youth: Sociocultural Issues, Factors, and Context. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25(5):201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Federal Register. Further Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Published February 22, 2023. Federal Register website. Retrieved from https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/02/22/2023-03779/further-advancing-racial-equity-and-support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal [Google Scholar]

- 19.Think Cultural Health. National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) Standards. 2013. Accessed on May 26, 2024. Retrieved from: https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/clas/standards

- 20.Asia Society Policy Institute. Regions. Last reviewed 2023. Accessed December 21, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/adults/index.htm [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 10 Essential Public Health Services. Last Reviewed September 18, 2023. Accessed December 21, 2023. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health Literacy and Health Equity: Connecting the Dots. Last Reviewed October 26, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2023. Retrieved from https://health.gov/news/202110/health-literacy-and-health-equity-connecting-dots [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shorey S, Ng ED, Haugan G, Law E. The parenting experiences and needs of Asian primary caregivers of children with autism: A meta-synthesis. Autism. 2020;24(3):591–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravindran N, Myers BJ. Cultural influences on perceptions of health, illness, and disability: A review and focus on autism. J Child Fam Stud. 2012;21:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hays PA. Addressing cultural complexities in practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Andrea M, Daniels J. RESPECTFUL counseling: An integrative model for counselors. In: The interface of class, culture and gender in counseling. 2001:417–466. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu WM, Liu RZ, Garrison YL, Kim JYC, Chan L, Ho Y, Yeung CW. Racial trauma, microaggressions, and becoming racially innocuous: The role of acculturation and White supremacist ideology. Am Psychol. 2019;74(1):143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pew Research Center. What it Means to be Asian in America. Published August 2, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/10/05/future-immigration-will-change-the-face-of-america-by-2065/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023;72(No. SS-2):1–14. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Lancet. Racism in the USA: ensuring Asian American health equity. Published April 3, 2021. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00769-8/fulltext#section-7c530872-6235-4433-899c-b3f276970189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Đoàn LN, Takata Y, Sakuma KK, Irvin VL. Trends in Clinical Research Including Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Participants Funded by the US National Institutes of Health, 1992 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197432. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Elliott A, Strelnick H, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Cottler LB. Asian Americans are less willing than other racial groups to participate in health research. J Clin Transl Sci. 2019;3(2-3):90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teranishi R, Lok L, Nguyen BMD. iCount: A Data Quality Movement for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Higher Education. Educational Testing Service. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev 1991;43(6):1241–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim I, Wang Y, Dababnah S et al. East Asian American Parents of Children with Autism: a Scoping Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 8, 312–320 (2021). 10.1007/s40489-020-00221-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giwa Onaiwu M. “They don't know, don't show, or don't care”: Autism's White privilege problem. Autism Adulthood. 2020;2(4):270–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cascio MA, Weiss JA, Racine E. Making autism research inclusive by attending to intersectionality: A review of the research ethics literature. 2021;8:22–36. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks R, Jones N, Battle K. (2024). What Updates to OMB’s Race/Ethnicity Standards Mean for the Census Bureau. [online] Census.gov. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2024/04/updates-race-ethnicity-standards.html.