Highlights

-

•

We observed that hypericin mediated PDT(HY-PDT) could significantly inhibit the proliferation of the CCA cells and suppress migration and the epithelial mesenchymal transition(EMT) as well.

-

•

Then, we conducted transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis and observed that HY-PDT was most likely involved in ferroptosis, apoptosis, the EMT process and AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathways in CCA cells.

-

•

Next, a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments were performed to confirm that HY-PDT could trigger CCA cells ferroptosis through inhibiting the expression of GPX4 protein.

-

•

In terms of molecular mechanism, we first found that HY-PDT induced ferroptosis by decreasing GPX4 expression via suppression of the AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway.

-

•

In addition, we found that HY-PDT inhibit CCA cells migration and the EMT process by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1 pathway.

Our study illustrated a new mechanism of action for HY-PDT and might throw light on the individualized precision therapy for CCA patients.

Keywords: Ferroptosis;Cholangiocarcinoma;PDT;GPX4;AKT

Abstract

Cholangiocarcinoma remains a challenging primary hepatobiliary malignancy with dismal prognosis. Photodynamic therapy (PDT),a less invasive treatment, has been found to inhibit the proliferation and induce ferroptosis, apoptosis and necrosis in other tumor cells in recent years. Regrettably, the role and exact molecule mechanism of PDT is still incompletely clear in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Ferroptosis is a novel regulated cell death(RCD), which is controlled by glutathione peroxidase4(GPX4) with the characteristics of iron dependent and excessive intracellular accumulation of lipid peroxides. This novel form of RCD has attracted great attention as a potential new target in clinical oncology during recent years. In this study, we observed that hypericin mediated PDT(HY-PDT) could significantly inhibit the proliferation of the cholangiocarcinoma cells and suppress migration and the epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) as well. Then, we conducted transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis and observed that HY-PDT was most likely involved in ferroptosis, apoptosis, the EMT process and AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathways in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Next, a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments were performed to confirm that HY-PDT could trigger cholangiocarcinoma cells ferroptosis through inhibiting the expression of GPX4 protein. In terms of molecular mechanism, we found that HY-PDT induced ferroptosis by decreasing GPX4 expression via suppression of the AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway. In addition, we also found that HY-PDT inhibit cholangiocarcinoma cells migration and the EMT process by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1 pathway. Our study illustrated a new mechanism of action for HY-PDT and might throw light on the individualized precision therapy for cholangiocarcinoma patients.

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a lethal malignancy originating from the biliary epithelial cells with a rising global incidence [1,2]. The incidence of CCA in Western countries is low, ranging from 3 cases per million to 60 cases per million inhabitants annually while in endemic areas of East and Southeast Asia, the highest incidence is soaring to 850 cases per million population [3,4]. At present, surgery remains the cornerstone of curative treatment for CCA [1,4,5].However, only around 20 % of CCA patients have access to curative surgery [6]. During the past decade,the 5-year survival of CCA patients after R0 resection has ranged from 7 % to 20 % with little improvement [3]. Moreover, CCA is usually insensitive to both chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and the effect of targeted therapy is very limited as well [7,8,9]. Therefore, it is urgently needed to investigate new approaches with exact mechanisms of action to lay the foundation for precision medicine.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a promising therapeutic approach for cancer, which involves the activation of the photosensitizer with light of a specific wavelength to kill tumor cells [10,11,12]. Large studies have reported that combination PDT and biliary stenting could result in significantly longer survival than biliary stenting alone for patients with unresectable CCA [13,14,15,16]. Additionally, PDT in conjunction with systemic chemotherapy was well tolerated and significantly improved the overall survival of chemotherapy alone [17,18]. As a second-generation photosensitizer, hypericin possesses the advantage of low dark toxicity and high tissue penetrability, which has been approved by the European Medicine Agency for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [19,20]. In the course of PDT, the activated hypericin generates abundant aounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS),which is able to directly attack tumor cells [21]. Moreover, HY-PDT could inhibit the proliferation of a variety of tumor cells, though, the mechanism of action on the treatment of CCA remains incompletely clear [19,22].

Ferroptosis, a novel non-apoptotic form of regulated cell death (RCD), is mainly initiated by iron-dependent Fenton reaction, exhaustion of the intracellular pool of reduced glutathione(GSH) and severe lipid peroxidation due to ROS generation [23,24]. As the core regulatory proteins of ferroptosis, GPX4 may utilizes GSH to decrease the level of cellular lipid peroxidation and ROS accumulation [23,25].Since this unique RCD emerges to be the underlying cause of many diseases,new therapeutic interventions against various cancers via regulation of ferroptosis signaling pathways have begun to be explored extensively [26,27,28,29].Epithelial mesenchymal transition(EMT),a process of epithelial cells get mesenchymal phenotypes, has been proved to play a crucial role in the invasion and metastasis of CCA cells. [30,31,32]. Accumulating studies suggest that ferroptosis potently inhibits the proliferation and metastasis in a variety of tumor cells [24,33,34]. Recent studies showed that PDT induce ferroptosis-like cell death and PDT combined with ferroptosis inducer could achieve the synergetic anti-tumor effects [35,36]. However, the effect and molecular level mechanism of PDT in CCA cells has been still incompletely understood and required to be further explored.

In the present study, we observed that HY-PDT could potently kill CCA cells and significantly inhibit tumor cells proliferation and suppress migration and the EMT process as well. Then, we conducted transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis to further explore the inhibitory actions. KEGG enrichment analysis and GSEA showed that HY-PDT was most likely involved in ferroptosis, apoptosis, EMT process and AKT/mTORC signaling pathways in CCA cells. We next validated that HY-PDT could induce ferroptosis of CCA cells through inhibiting the expression of GPX4 protein. In terms of molecular mechanism, we performed both in vitro and in vivo experiments to found that HY-PDT induced CCA cells ferroptosis by decreasing GPX4 expression via suppression of the AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway. Moreover, we also observed that HY-PDT could restrain migration and the EMT process by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway in CCA cells. Our findings demonstrated a new mechanism of PDT and might lay the foundation for the more precision therapy for patients with CCA.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

The information of reagents and antibodies were detailed as the following table:

| Reagent or antibody | Source | Identifier | Country of origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPX4 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#52,455 | USA |

| AKT | Proteintech | Cat#10,176–2-AP | USA |

| mTOR | Proteintech | Cat#28,273–1-AP | USA |

| 4E-BP1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#9644 | USA |

| Phospho-AKT(ser473) | Proteintech | Cat#66,444–1-Ig | USA |

| Phospho-mTOR(ser2448) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5536 | USA |

| Phospho-4E-BP1(Thr37/46) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2855 | USA |

| E-cadherin | Proteintech | Cat#20,874–1-AP | USA |

| N-cadherin | Proteintech | Cat#22,018–1-AP | USA |

| Vimentin | Proteintech | Cat#10,366–1-AP | USA |

| SNAI1 | Proteintech | Cat#10,491–1-AP | USA |

| GAPDH | Proteintech | Cat#13,099–1-AP | USA |

| Vimentin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#5741 | USA |

| Anti-rabbit IgG,HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7074 | USA |

| Anti-mouse IgG,HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#7076 | USA |

| SC79 | MCE | Cat#HY-18,749 | USA |

| HY-18,749 | MCE | Cat#HY-B0795 | USA |

| Liproxstatin-1 | MCE | Cat#HY-12,726 | USA |

| Hypericin | MCE | Cat#HY-N0453 | USA |

| Plasmid Midi Preparation Kit | Beyotime | Cat#D0018 | China |

| Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit | Beyotime | Cat #S0033S | China |

| Lipid Peroxidation MDA Assay Kit | Beyotime | Cat#S0131S | China |

| PMSF | Beyotime | Cat#ST506 | China |

| GSH and GSSG Assay Kit | Beyotime | Cat#S0053 | China |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 | Beyotime | Cat#C0037 | China |

| BeyoClickTM EdU Cell Proliferation Kit with Alexa Fluor 555 | Beyotime | Cat#C0075S | China |

| 4 %paraformaldehyde (PFA) | Servicebio | Cat#G1101 | China |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | Servicebio | Cat#G2002 | China |

| Crystal violet staining | Servicebio | Cat#G1014–50ML | China |

| eco-friendly deparaffinization solution | Servicebio | Cat#G1128 | China |

| Anti-Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | Cat#GB114327–100 | China |

| Anti-Ki67 Rabbit pAb | Servicebio | Cat#GB111499–100 | China |

| BCA Protein Assay Kit | Cwbio | Cat#CW0014S | China |

| Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit | Vazyme | Cat#A211–02 | China |

Cell culture

Two human CCA cell lines,HUCCT1 and CCLP1,were acquired from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). HUCCT1 cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640(11,875,093, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and CCLP1cell lines were cultured in DMEM (11,995,065, Thermo Fisher Scientific,USA). The media for the cell lines were supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and 1 % penicillin/streptomycin (Biosharp, Beijing, China), and the incubation temperature was 37 °C with 95 % air and 5 % CO2.

HY-PDT treatment and cell viability assay

We seeded cells into 96-well plates (3 × 103 cells per well) and left to adhere overnight. The medium was replaced on the following day with 100μl of growth medium containing a required concentration of photosensitizer(hypericin) and the cells were incubated in the dark for 4 h Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS three times, and the photosensitized cells were exposed to 650 nm infra-red light generated by the Aladdin-A red-light therapy apparatus (Lifotronic, Guangdong, China)and illuminated at 1J/cm2 to activate hypericin. The designated agents(e. g. liproxstatin-1, SC79, MHY1485 etc.) were usually added simultaneously with hypericin or incubated for specific time. Cell viability was assessed typically 24 h after light irradiation using cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). According to the protocol provided by the supplier, we added 10 μl per well of CCK-8 regents and incubated it for 1.5 h at 37 °C. Absorbance value was measured at 450 nm using a Varioscan Lux multimode microplate reader (Thermo Scientific,USA).

Annexin V-FITC/PI staining

We seeded cells into 6-well plates in their respective medium and left to adhere overnight. Subsequently, cells were trypsinized after HY-PDT treatment for 2 h, transferred to a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and washed twice with pre-chilled PBS. Cells (2 × 105 cells per well) were counted and resuspended in 300 μl binding buffer and stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI staining kit (Vazyme, Jiangsu, China) according to manufacturer′s instructions. Each tube was respectively added 500 μl binding buffer, 5 μl of annexin V-FITC and 5 μl of PI, vortexed thoroughly, incubated for 15 min at room temperature under light-protected conditions.Samples were analyzed with the BD Accuri C6 Plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences,USA) within 1 h after staining [37].

Colony formation assay

Cells pretreated with different HY-PDT conditions were seeded in 6-well plates (1000 cells per well) and cultured for approximately two weeks with 2 ml complete medium per well at 37 °C with 5 % CO2. Fresh medium was replaced once a week. When the clones were visible to the naked eye (>50 cells/clone), the culture was terminated. Then, the cells were washed twice with PBS and 4 % paraformaldehyde (Servicebio, Hubei, China) was used to fix the colonies for 15min. Cells were washed once again with PBS and stained with 0.1 % crystal violet solution for 15 min (Servicebio, Hubei, China). Each well was photographed and the colonies were quantified using Image J software.

EdU-DNA synthesis assay

Cells(3.5 × 104cells per well) were counted and planted on 14 mm diameter round-shaped glass slides in a 24-well culture plate in 300μl of respective complete medium overnight at 37 °C. Subsequently, cell proliferation rate was determined using the EdU cell proliferation kit with Alexa Fluor 555(Beyotime, Shanghai, China)after HY-PDT treatment for 24 h The pre-warmed EdU working solution was added to the treated cells for EdU labelling for 2 h After removal of the medium, the cells were fixed at room temperature in 4 % paraformaldehyde(300 μl per well) for 15 min, and then, 100 μl of Click reaction solution was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Finally, DNA was stained with Hoechst 33,342 Solution(300 μl per well), and the cells were incubated for 10 min at room temperature under light-protected conditions. After staining, the plate was washed with washing liquid for three times and images were taken with an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE TI-S, Japan).

Wound-healing assay

Cells were planted into 6-well plates in complete medium and left to adhere overnight. The medium was replaced on the following day with 2 ml of growth medium containing the respective concentration of hypericin when the cells evenly overspreaded the culture plate. After 4 h incubation in the dark,the photosensitized cells were treated with HY-PDT. Then,we used a 1 ml pipette tip to scrape the cells in 6-well plates to produce wounds. Cells were washed with sterile PBS for three times to remove floating cells, and fresh serum-free culturing medium was added to exclude the effect of cell proliferation. The wound area was photographed at 0 h and 24 h with an inverted research microscope. The wound-healing percentage was calculated and analyzed using the imageJ software.

Transwell assay

1.5 × 104 cells pretreated by different HY-PDT conditions were seeded into the upper chamber of each transwell (8.0μm Pore Size,Corning,USA) containing 200ul of serum-free medium. Approximately 750μl corresponding fresh medium with 10 % FBS was added into the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. After 24 h incubation inside the incubator at 37 °C, the cells on the lower side of the transwell chambers were fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet for 20 min. An inverted microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE TI-S, Japan) was used to take the image and data were analyzed using ImageJ software.

Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq)

Total RNA was extracted from cells samples of PDT-treated (hypericin, 2uM)(PDT groups,n = 3)and non-treated(control groups,n = 3) with Trizol reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The extracted RNA was sent to Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co., Ltd(Shanghai, China) for transcriptome sequencing. Differentially expressed genes between PDT groups and control groups were analyzed using the edgeR package, and significance thresholds were |log2(FoldChange)| > 1 and adjusted P value < 0.05. KEGG pathway analysis and gene set enrichment analysis(GSEA) between two groups were performed by the clusterProfiler R package. The enrichment terms with adjusted P values or P values less than 0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched.

Reactive oxygen species detection

We planted cells into 24 well plates at a density of 3.5 × 104 cells per well on 14 mm diameter glass coverslips containing 1 ml of corresponding culture medium per well. The cells were incubated overnight at 37° in a 5 % CO2 incubator. The next day, the cells were treated with different HY-PDT conditions when the cells evenly overspreaded the culture plate. Intracellular ROS level was detected by a reactive oxygen species assay kit (S0033S, Beyotime, China). 300μl fluorescent probe DCFH-DA diluted with serum-free medium (1:1000) was added into each well, mixed well and incubated in a cell incubator at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed with serum-free medium three times to remove the residual DCFH-DA and photographed with a fluorescence microscope(Nikon ECLIPSE TI-S, Japan).

Detection of lipid peroxidation level and reduced glutathione(GSH)

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates and pretreated with different HY-PDT conditions when the cells evenly overspreaded the culture plate. Intracellular malondialdehyde (MDA) was detected by the lipid peroxidation MDA assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cells were harvested and washed twice with sterile PBS, and then lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Servicebio, Hubei, China)and centrifuged by a high-speed cryogenic centrifuge(Cence Centrifuge,Hunan, China) at 12,000 g at 4 °C for 5min. The supernatants were collected on ice and the protein concentration determined using BCA assay. According to the instruction manual, 100ul sample and 200ul MDA detection working solution were added into each well, and the mixed solutions were incubated at 100 °C for 15 min. After being cooled to room temperature, tubes were centrifuged at 1000 g and then 200ul supernatant was taken and added into a 96-well plate. The absorbance values were determined at 532 nm using a Varioscan Lux multimode microplate reader (Thermo Scientific,USA). GSH was detected by GSH and GSSG assay kit (S0053, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The relevant cell suspension was subjected to two cycles of rapid freeze–thawing in a −80 °C freezer and 37 °C water bath and were left in the 4 °C refrigerator for 5 min. Then, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min and the supernatants were collected at 4 °C. Subsequently, the different reagents were added in turn and the absorbance of the supernatant was added to a 96 well plate and measured at wavelengths of 412 nm using a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific,USA). The GSH content was calculated by subtracting GSSG from total glutathione (GSH+GSSG) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting analysis

Tissue and total cell proteins were extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (Servicebio, Hubei, China) with 1 % PMSF(Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and 1 % phosphatase inhibitor (Servicebio, Hubei, China). After denaturation, the equal amount of protein samples were loaded onto 10–12 % SDS-PAGE for electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5 % nonfat milk at room temperature for 2 h and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies at 1:1000 dilution at 4 °C. The membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase anti-mouse or anti-rabbit (Cell Signaling Technology,USA,1:2000 dilution) secondary antibody for 2 h at room temperature on the following day. The Western blot bands were washed and developed with SuperPico ECL chemiluminescence kit (Vazyme, Jiangsu,China)and photographed with the Chemiluminescent Imaging System (Tanon-4800, China). Finally, the protein bands were semi‐quantitatively analysed using ImageJ software in each group. All data were shown as relative level after being normalized by GAPDH [38].

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Cell samples were collected and fixed with electron microscope fixative(Servicebio, Hubei, China). After centrifugation, cells pellets were embedded in 1 % agarose and fixed with 1 % osmic acid (18,456, Ted Pella Inc, USA) at room temperature for 2 h Then, samples were serially dehydrated with 30 %, 50 %, 70 %, 80 %, 95 % and 100 % alcohol and 100 % acetone in turn. After resin penetration and embedding, the resin blocks were moved into 65 °C oven to polymerize for more than 48 h,and were cut to 60–80 nm thin on the ultra microtome.The specimen sections were stained with 2 % uranium acetate saturated alcohol solution under light-protected conditions. Finally, The cell samples were observed under TEM and take images [39].

Hematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) staining

After fixation in 4 % paraformaldehyde, tumor tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced into 5 μm thick by a Leica pathologic microtome (RM2016, Shanghai, China). Then, the samples were dewaxed through eco-friendly deparaffinization solution followed by graded alcohols (100 %, 100 %, 75 % ethanol)and rehydrated in distilled water. The slices were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and histopathological damage was assessed using an Eclipse E100 light microscope(Nikon, Japan).

Immunohistochemical analysis(IHC)

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were dewaxed, rehydrated and antigen retrieval was performed in 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3 % H2O2 solution at room temperature for 25 min. Subsequently, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies of anti-GPX4 rabbit pAb(1:200, Servicebio) and anti -Ki67 rabbit pAb (1:500,Servicebio, Hubei, China) at 4 °C overnight. The horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (1:200, Servicebio, Hubei, China) was incubated for 50 min at room temperature.The sections was developed with DAB chromogenic solution (Servicebio, Hubei, China) and the color reaction was terminated with washing tap water at the appropriate time. The nucleus were counterstained with hematoxylin solution for 3 min and dehydrated by gradient alcohol. After sealing the pieces, sections were finally observed and photographed under a light microscope(40 ×). Semi-quantitative analysis of IHC were qualified by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software, which was estimated by the staining intensity and the area of each staining.Mean option density(MOD)=Integrated option density(IOD)/ Area.

In vivo xenograft mouse study

BALB/c nude mice (female, 4∼5-weeks old and 16∼18 g) were purchased from Gempharmatech Co., Ltd(Jiangsu, China) and raised for one week before experiment to acclimated to their surroundings. Each mouse was subcutaneously inoculated with HUCCT1 cells (1 × 107 cells) in the lateral of left forelimb armpits. Then, the mice were divided randomly into control group, low-dose group,high-dose group and Lip group,6 mice per group. Each mouse of the different experimental groups was injected with 200μl hypericin through the tail vein at a dose of 4mg/kg or 8mg/kg (low-dose group 4mg/kg, high-dose group 8mg/kg, Lip group 8mg/kg) from day 7, and the mice in the control group were injected with equal volume of saline. The tumor areas were exposed to the red light irradiation (650 nm,60mW/cm2) for 20 min at 4 h and 24 h after injection. Each mouse of Lip group was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 10 mg/kg 24 h before the irradiation and then injected once a day during the first three days after the irradiation. Body weight and tumor size were measured every 2 to 3 days starting from day 7. The tumor volume (V) was calculated according to the following formula: V = 0.5 × (length × width2). All mice were euthanatized 10 days after irradiation and tumor tissues were frozen and stored at −80 °C for further analysis. In histological examination, tumor tissues were fixed, embedded, and sectioned for H&E staining and IHC as described in our previous study. All animal experiments were approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Third Hospital, Shandong University.

Statistical analysis

Numerical variables were expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD). Unpaired student's t-test was used to compare two groups of independent samples and one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means of multiple groups. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism8.0 software. The bands of the western blotting were conducted semi-quantified analysis by measuring the grayscale values with ImageJ software.P values were considered statistically significant when *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001. In this study, all the experiments were replicated independently at least three times.

Results

HY-PDT induces cell death and suppresses the proliferation of CCA cells

The CCK-8 experiments demonstrated that the viability of both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells was inhibited by HY-PDT in a photosensitizer (hypericin) dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Flow cytometry showed that the number of dead CCA cells stained with Annexin V-FITC/PI was increased significantly in a hypericin concentration-dependent fashion after HY-PDT (Fig. 1B). In addition, colony formation capability was measured by the colony formation assay. According to the results, the colony numbers of CCA cells after HY-PDT were reduced in a hypericin concentration dependent manner compared with the control group. (Fig. 1C). Moreover, the EdU-DNA synthesis assay was performed to measure the effect of HY-PDT on cell proliferation. The results revealed that EdU staining positive rate of CCA cells was significantly decreased after HY-PDT and EdU-positive cells obviously decreased with increasing hypericin dose(Fig. 1D). The results indicated that HY-PDT could not only induce cell death but also suppressed the proliferation of CCA cell lines. Moreover, this anti-tumor effect could be gradually intensified with increasing hypericin concentration in a certain range.

Fig. 1.

HY-PDT induces cell death and suppresses the proliferation of CCA cells.

A CCK-8 assays were conducted to determine the cell viability of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after different HY-PDT treatments(OD value at 450 nm). B Annexin V-FITC/PI staining assays were performed in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells. C Colony-formation assays were conducted in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells in control groups(hypericin, 0uM)and different HY-PDT groups(hypericin,1uM,2uM,4uM). The colony numbers were calculated using ImageJ software. EdU-DNA synthesis assays were performed to evaluate the proliferation capability of CCA cells. Representative images are presented in (Fig. 1,D) , the scale bars represent 50 μm. Proliferation was quantified in percentage of EdU-positive HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

HY-PDT inhibits the metastasis of CCA cells

In addition, we explored the role of HY-PDT on the cell motility and EMT process of CCA. To assess the effect of HY-PDT on the cell metastatic capacity, wound-healing experiments and transwell assays were performed (Fig. 2A-B). We observed that HY-PDT significantly attenuate the cells motility versus the control group. Moreover, the inhibitory effect became more apparent with increasing hypericin concentration in a certain range. To further explore the impact of HY-PDT on EMT, the expression of related genes including E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 were analyzed by Western blotting in CCA cells(Fig. 2C). The results revealed that the expression of E-cadherin was up-regulated in a hypericin concentration-dependent manner after HY-PDT with concomitant declines of N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 expressions in CCA cells. These results showed that HY-PDT might inhibit the process of EMT in both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cell lines.

Fig. 2.

HY-PDT inhibits the process of EMT in CCA cells.

A Wound-healing assays were conducted to assess the migration of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. B Transwell assays were performed to measured the migration of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. C Western blotting analysis were conducted to measured the expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

The KEGG analysis and GSEA obtained from RNA-seq

To explore the role and mechanistic effect of HY-PDT on CCA cells, we treated HUCCT1 cells with PDT and non-PDT respectively and conducted transcriptome sequencing. We analyzed the differentially expressed genes on the RNA sequencing and KEGG enrichment analysis and GSEA were conducted among upregulated and downregulated genes and found that differentially expressed genes were mainly involved in apoptosis, AKT-mTOR signaling pathways, ferroptosis, metastasis EMT, FoxO signaling pathway and other pathways (Fig. 3A-D). To some extent, the RNA-seq and bioinformatics analysis findings suggested directions for our follow-up studies.

Fig. 3.

The KEGG analysis and GSEA obtained from RNA-seq

A KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. B Bubble chart plot displays the results of the GSEA. C GSEA enrichment analysis on AKT/mTOR signaling between the control and PDT groups. D GSEA enrichment analysis on EMT between the control and PDT groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

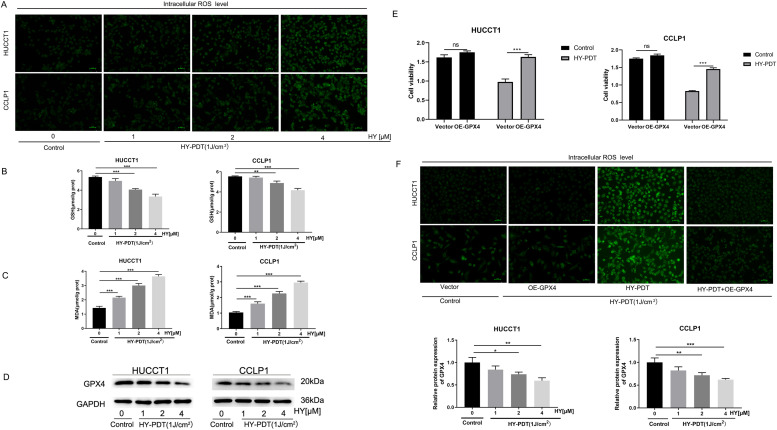

HY-PDT triggers ferroptosis regulated by GPX4 in CCA cells

Based on the results of bioinformatics analysis, we further explored the death manner of CCA cells after HY-PDT. We analyzed the changes of intracellular ROS, GSH and MDA, which were the critical biological indicators of ferroptosis (Fig. 4A-C). The results showed that,in a certain range, HY-PDT significantly increased the intracellular ROS and MDA level in a hypericin concentration-dependent manner. Correspondingly, the levels of GSH were appreciably decreased in a hypericin concentration-dependent manner after HY-PDT. In addition, the expressions of the core regulatory proteins of lipid oxidation GPX4 were also detected by Western blotting. Compared with the control groups, the expression levels of GPX4 proteins after HY-PDT declined in a dose-dependent manner in CCA cells (Fig. 4D). In order to confirm the findings, CCA cells were transfected with GPX4 overexpression plasmids to perform rescue experiments. Through the CCK-8 assays,we observed that overexpressing GPX4 could significantly reversed the inhibition of HY-PDT on CCA cells viability (Fig. 4E). Fluorescent probe DCFH-DA staining results showed that overexpression of GPX4 reversed the PDT-induced increase of the intracellular ROS levels in both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells (Fig. 4F). Thus, these results indicated that PDT-induced ferroptosis was mainly regulated by GPX4 in CCA cells.

Fig. 4.

HY-PDT down-regulates the expression of GPX4 to trigger ferroptosis in CCA cells.

A Fluorescent probe DCFH-DA assays were performed to measure intracellular ROS level in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. B, C GSH and MDA levels in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT were also detected. D Changes in the expression GPX4 protein in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. E CCK-8 assays demonstrated that over-expression of GPX4 rescued cell viability (OD value at 450 nm) in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. F Fluorescent probe DCFH-DA assays exhibited that over-expression of GPX4 reversed the intracellular ROS level in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ns no significance.

Ferroptosis inhibitor reversed the anti-tumor effect of HY-PDT in CCA cells

To further study the above findings, the following experiments were performed. First, we found that the addition of liproxstatin-1(Lip,10uM), a ferroptosis inhibitor, significantly reversed CCA cells death induced by HY-PDT (hypericin,2uM) in CCK-8 assays(Fig. 5A). Likewise, liproxstatin-1 (10uM) effectively rescued the decreasing expression of GPX4 and GSH while reversed the increasing the level of intracellular ROS and MDA induced by HY-PDT (hypericin, 2uM) (Fig. 5B-E). In order to investigate the morphological changes further, the microstructure of CCA cells were observed using TEM. Compared with the control groups, both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells showed typical morphological features of ferroptosis, including intact nuclear membrane, shrunken mitochondria morphology with increased mitochondrial matrix electron density and decreased or disappeared mitochondrial cristae after HY-PDT (hypericin, 2uM). In CCLP1 cells, we could even observe the number of mitochondria was clearly diminished due to the rupture of the mitochondrial membrane. Adding ferroptosis inhibitor liproxstatin-1 (10uM) to the cells and cultured for 4 h could significantly reverse the degree of mitochondrial impairment induced by HY-PDT in both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Lip-1 rescues the change of ferroptosis in CCA cells induced by HY-PDT.

A CCK-8 assays showed that Lip-1 (10 µM) rescued the decline of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells viability(OD value at 450 nm) triggered by HY-PDT. B Western blotting analysis demonstrated that Lip-1 (10 µM) reversed the decline of GPX4 protein in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. C Fluorescent probe DCFH-DA assays showed that Lip-1 (10 µM) reversed the increased ROS level in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. D,E Lip-1 (10 µM) could reverse the change of GSH and MDA levels after HY-PDT in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells. F The ultrastructural changes of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after treatment of different conditions were observed under TEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

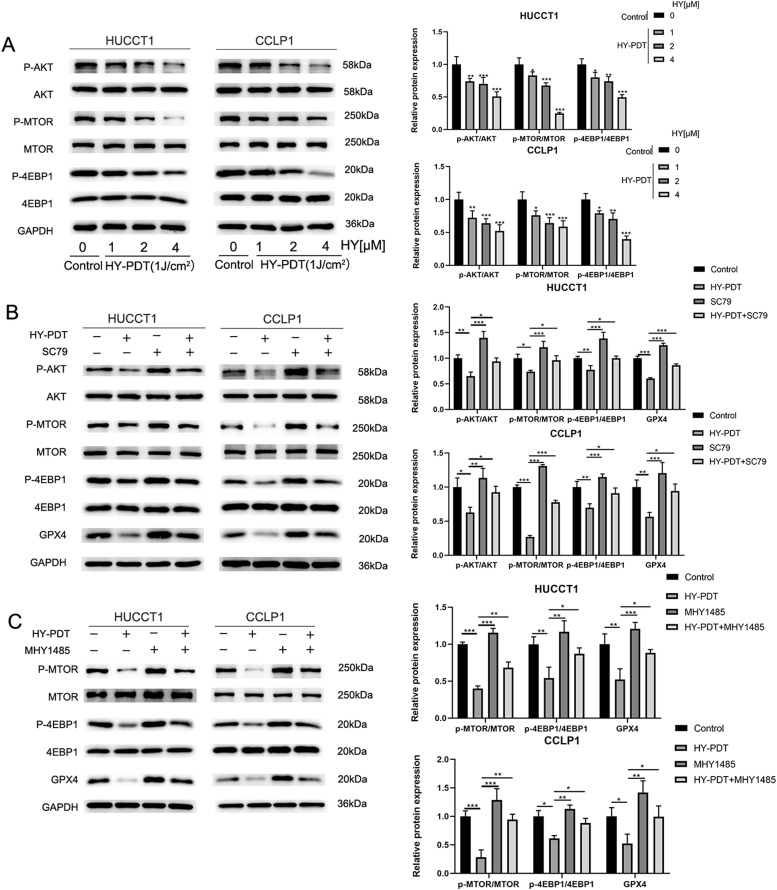

HY-PDT decreases the expression of GPX4 through the AKT/ mTORC1/4EBP1 axis

Next, we further explored the potential link between GPX4 and the AKT/mTORC1 pathway by Western blotting. It has been identified that the mTORC1/4EBP1 signaling pathway exhibits a crucial function during the process of protein synthesis. Combined with KEGG and GSEA enrichment analysis, the results indicated that the AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway could be involved in HY-PDT. Therefore, Western blotting analysis was performed to detect the expression ratios of major proteins, including phosphorylated Akt/total Akt, phosphorylated mTOR/total mTOR and phosphorylated 4EBP1/total 4EBP1. The results revealed that the relative expression ratios of these proteins were significantly decreased in a dose-dependent manner after HY-PDT in both HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells (Fig. 6A). Subsequently, we conducted rescue experiments adding the AKT activator SC79 (10μM) to the media of CCA cells for 4 h Interestingly, SC79 significantly reversed the declining trend of phosphorylated Akt/total Akt, phosphorylated mTORC/total mTOR, phosphorylated 4EBP1/total 4EBP1 and the expression of GPX4 protein in CCA cells after HY-PDT (hypericin, 2uM) (Fig. 6B). Likewise, adding the mTOR activator MHY1485 (10μM) to the media of CCA cells for 2 h prior to the HY-PDT (hypericin, 2uM), the declining trend of associated phosphorylated proteins ratios and the expression of GPX4 protein were also rescued successfully (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these findings suggested that the expression of GPX4 protein was regulated by HY-PDT via the AKT/mTORC1/4EBP1 axis.

Fig. 6.

HY-PDT inhibits GPX4 protein expression through the AKT/mTORC1/4EBP1 pathway.

A The phosphorylated and total protein levels of AKT,mTOR and 4EBP1 in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. B SC79 (AKT agonist, 10 μM) reversed the relative expression of p-AKT/AKT, p-mTOR/mTOR, p-4EBP1/mTOR and GPX4 proteins in the HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells treated with HY-PDT(hypericin, 2uM). C MHY1485 (mTOR agonist, 10 μM) reversed the relative expression of p-mTOR/mTOR, p-4EBP1/4EBP1 and GPX4 proteins in the HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells treated with HY-PDT(hypericin, 2uM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

HY-PDT suppresses CCA cells proliferation and EMT and triggers ferroptosis by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1 axis

Subsequently, the effects of the AKT/ mTORC1 axis on CCA cells proliferation, ferroptosis, and EMT were further studied. Colonyformation experiments indicated that the decreased numbers of colonies induced by HY-PDT were obviously reversed by both SC79 and MHY1485 (Fig. 7A). Likewise, the CCK-8 experiment showed that SC79 and MHY1485 were able to significantly rescue cell viability of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT (Fig. 7B). To explore the change of CCA cells motility, we performed transwell assays and wound-healing experiments. Interestingly, activating the AKT/mTORC pathways could clearly reverse the decrease in the motility of CCA cells (Fig. 7C-D). Next,western bloting analysis was performed to further explore the molecular mechanisms of this phenomenon. Compared with HY-PDT treatment alone, the expression levels of EMT-associated proteins, such as E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Vimentin and Snal1 were also reversed after pre-incubation with SC79 or MHY1485 (Fig. 7E). In addition, we found that both SC79 and MHY1485 were also able to effectively rescue the decrease of GSH levels induced by HY-PDT (Fig. 7F). These findings reveal that HY-PDT regulates CCA cells proliferation, ferroptosis and EMT via the AKT/mTORC1 axis.

Fig. 7.

HY-PDT suppresses proliferation and EMT and triggers ferroptosis by inhibiting the AKT/mTORC1 pathway.

A Both SC79 and MHY1485 all reversed the decrease in colony numbers in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. B CCK-8 assay data showed that SC79 or MHY1485 reversed the decline of cell viability in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT. C,D Transwell assays and wound-healing exhibited that the impaired migratory capacity of HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells induced by HY-PDT were rescued by SC79 or MHY1485. E Western blotting analysis showed that the protein expression levels of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells treated with HY-PDT(hypericin, 2uM) were reversed by SC79 or MHY1485. F The decline of GSH levels in HUCCT1 and CCLP1 cells after HY-PDT were reversed by SC79 or MHY1485. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

HY-PDT triggers ferroptosis and inhibits CCA cells proliferation and EMT in vivo

We further evaluated the in vivo anti-CCA effects of HY-PDT in a mouse xenograft model. BALB/c nude mice with HUCCT1 subcutaneous xenografts received single injection of hypericin. The mice were then exposed to the red light irradiation (650 nm,60 mW/cm2,20 min) and the tumors volume change were monitored over a period of 10 days. The line chart showed the changes in tumors size at different time points. We observed that the tumors growth were significantly inhibited by HY-PDT and the inhibitory effects were enhanced with the increasing dose of hypericin while the ferroptosis inhibitor Lip-1 could largely counteracted the inhibitory effect of HY-PDT (Fig. 8A-B). In addition, the expression ratios of phosphorylated Akt/total Akt, phosphorylated mTORC/total mTOR, phosphorylated 4EBP1/total 4EBP1 among groups were examined by Western blotting analysis (Fig. 8C). EMT-associated proteins, including E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 were also analyzed by Western blotting (Fig. 8D). HE pathological sections of tumors revealed that the severity of tissue damages with destroyed cells caused by HY-PDT also became more evident with increasing dose of hypericin. Similarly, Lip-1 could counteracted part of the killing effects on CCA cells caused by HY-PDT (Fig. 8E). We also detected the expression levels of Ki67, a cell proliferation marker, in xenograft tumors by IHC and observed that the tumor size was positively correlated with the expression of Ki67. Additionally, we also detected the expression changes of GPX4 in different tumor tissues by IHC and the results from in vivo experiments were consistent with our in vitro findings (Fig. 8F).

Fig. 8.

HY-PDT inhibits CCA cells proliferation and EMT and induces ferroptosis in vivo

A The mice tumor volumes changed over time in different groups. B Images of excised tumor tissues from mice obtained 10 days after HY-PDT. C Changes in protein expression of p-AKT/AKT, p-mTOR/mTOR and p-4EBP1/mTOR by Western blotting analysis in mice tumors after different treatment. D Changes in protein expression of E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin and snal1 by Western blotting analysis in mice tumors after different treatment. E Histological examination of excised tumors from mice by H&E staining(40 ×). F The protein expression levels of Ki67 and GPX4 in tumors tissues sections were shown in representative IHC images(40 ×). G Mechanisms of PDT induced ferroptosis by promoting lipid peroxidation. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

The recent decade has witnessed the flourishing development of ferroptosis and increasing attention has been drawn on the study focusing on ferroptosis [23,24]. PDT, a minimally invasive treatment approach, is a significant way of the application of ferroptosis in clinical practice, which combines the action of photonic energy and photosensitizers [35,40]. Shui et al. first reported that HY-PDT could initiate a unique ferroptosis-like cell death in other tumor cells, which was independent of lipoxygenase (ALOXs) and ACSL4 [35]. However, the role and ferroptosis upstream regulatory mechanisms of PDT has remained incompletely clear in CCA cells and required to be further investigated.

In this study, we first found that HY-PDT potently inhibited the cell viability and suppressed the proliferation of CCA cells and the inhibitory action of PDT presented a hypericin dose-dependent manner across a certain range. Then, transcriptome sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were conducted and we found that hypericin mediated PDT was quite possible involved in ferroptosis in CCA cells. CCK-8 assays were performed and we observed that the addition of the ferroptosis inhibitor could significantly reverse CCA cells death after PDT. Additionally, we found that the levels of GSH were appreciably decreased in a photosensitizer dose-dependent manner after PDT. Correspondingly, HY-PDT significantly increased the intracellular ROS and MDA level in a dose-dependent manner as well while liproxstatin-1 effectively reversed the increasing intracellular ROS level induced by HY-PDT. From the perspective of the morphological changes, CCA cells showed typical ultrastructure of ferroptosis after HY-PDT while adding ferroptosis inhibitor could significantly reverse the degree of mitochondrial impairment induced by HY-PDT in CCA cells. GPX4 is well recognized as the core regulatory proteins of ferroptosis, which utilizes GSH to inhibit lipid peroxidation and ROS accumulation [23,25]. The expression of GPX4 were detected to decline in a hypericin dose-dependent manner after HY-PDT by Western blotting in CCA cells. Next, we transfected CCA cells with GPX4 over-expression plasmids to perform rescue experiments and found that over-expression of GPX4 reversed the increase of the intracellular ROS levels and the inhibition of cells viability induced by HY-PDT in CCA cells. These results suggest that HY-PDT possess the capacity to trigger ferroptosis which is induced by suppressing the expression of GPX4 protein in CCA cells. Similar to our findings, PDT of self-delivery nanomedicine could enhance lipid peroxidation of ferrotherapy via inhibiting GPX4 [41]. Recent study of Kojima Y et al. showed that combining talaporfin sodium-PDT with ferroptosis inducers, such as RSL3, could improve the anti-tumor efficacy by inhibiting cystine uptake activity of system Xc [36]. However, the toxic side effects or off-target effects of the potent inducers of ferroptosis, including sorafenib, cisplatin and lapatinib, which all are conventional chemotherapeutic drugs as well, remain a grave challenge for modern medicine [42,43]. Our research expands the targeted therapy space of PDT and exploit a novel perspective for the universal application of ferroptosis in CCA in the future.

The Akt/mTOR axis is a key intracellular signaling pathway involved in cellular functions, including cell survival, proliferation, migration and protein synthesis [9,44]. Cai et al. showed that the inhibition of AKT/mTORC1 signaling pathway could decrease the expression of GPX4, which induced ferroptosis in glioblastoma [33]. Additionally, Zhang et al. reported that SLC7A11-mediated extracellular cystine uptake inhibited ferroptosis by promoting GPX4 protein synthesis via the mTORC1–4EBP1 signaling pathway in multiple tumor cells [45]. In this study, we observed that the phosphorylation level of key proteins in the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway including Akt, mTOR and 4EBP1 were significantly decreased in a photosensitizer dose-dependent manner after HY-PDT in CCA cells. Interestingly, Akt/mTOR pathway agonists, whether by adding SC79 or MHY1485 could significantly reverse the decreasing expression of GPX4 and the declining degree of Akt, mTOR and 4EBP1 phosphorylation after HY-PDT as well. Moreover, we found that both SC79 and MHY1485 could remarkably rescue the decline of GSH levels after PDT as well. Combining above results, we suggested that HY-PDT triggered ferroptosis in CCA cells by inhibiting the expression of GPX4 protein through the Akt/mTORC1/4EBP1 pathway. Excessive proliferation, migration and EMT process are all important hallmarks of malignant tumor cells [29,46,47]. Recent studies demonstrated that HY-PDT could inhibit cell proliferation, migration and the EMT process in thyroid,breast, bladder and colon cancer [12,40,47,48]. Similar to these results, our research found that HY-PDT could significantly inhibit these disease phenotypes via AKT/mTOR pathway in CCA cells. Moreover, AKT/mTOR axis agonists, such as SC79 and MHY1485, reversed CCA cells proliferation, migration and EMT process induced by HY-PDT. Although the Akt/mTOR pathway is a promising therapeutic target for cancers, drug resistance and side effects of targeted agents to a large extent limit their clinical applications and only few drugs have received regulatory approval to date [49]. PDT possesses the advantages of low drug resistance, few side effects and accurate tumor localization, which paves a new avenue for individualized therapeutic modality of cancers [50,51].

In conclusion, our study found a novel anticancer mechanism of HY-PDT in CCA. Moreover, this research highlighted the role of AKT/mTORC1/GPX4 axis on ferroptosis and further investigation of the molecular mechanisms underlying PDT might lay the foundation for the precision therapies of CCA [52].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wei An: Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. Kai Zhang: Supervision, Software, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Guangbing Li: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Shunzhen Zheng: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology. Yukun Cao: Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Conceptualization. Jun Liu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding statement

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No ZR202211190156), the Medical and Health Science Technology Development Project of Shandong Province (202204010946) and Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project of Shandong Province (M-2023071).

References

- 1.Valle Juan W, et al. Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 2021;397(10272):428–444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.VITHAYATHIL M., KHAN S.A. Current epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma in western countries. J. Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1690–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banales J.M., Marin J.J.G., Lamarca A., Rodrigues P.M., Khan S.A., Roberts L.R., et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0310-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel A., Bridgewater J., Edeline J., Kelley R.K., et al. Biliary tract cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2023 Feb;34(2):127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.10.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunasekaran Ganesh, Bekki Yuki, Lourdusamy Vennis, et al. Surgical treatments of hepatobiliary cancers. Hepatology. 2021;0(0):128–136. doi: 10.1002/hep.31325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.GómezEspaña M.ª.A., Montes A.F., GarciaCarbonero R., et al. SEOM clinical guidelines for pancreatic and biliary tract cancer (2020) Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021;23(5):988–1000. doi: 10.1007/s12094-021-02573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Zhipeng, Liu Jialiang, Chen Tianli, et al. HMGA1-TRIP13 axis promotes stemness and epithelial mesenchymal transition of perihilar cholangiocarcinoma in a positive feedback loop dependent on C-Myc. J. Experim. Clinic. Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-01890-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abou-Alfa Ghassan K, Sahai Vaibhav, Antoine Hollebecque, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):671–684. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30109-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Le, Wei Jessica, Liu Pengda. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway for targeted therapeutic treatment in human cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021:85. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kolarikova Marketa, Hosikova Barbora, Dilenko Hanna, et al. Photodynamic therapy: innovative approaches for antibacterial and anticancer treatments. Med. Res. Rev. 2023;43(4):717–774. doi: 10.1002/med.21935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Lisha, Song Dongfeng, Qi Ling, et al. Photodynamic therapy induces human esophageal carcinoma cell pyroptosis by targeting the PKM2/caspase-8/caspase-3/GSDME axis. Cancer Lett. 2021;520:143–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferenc Peter, Solár Peter, Kleban Ján, al et. Down-regulation of Bcl-2 and Akt induced by combination of photoactivated hypericin and genistein in human breast cancer cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2010;98(1):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harsha Moole, Harsha Tathireddy, Sirish Dharmapuri, et al. Success of photodynamic therapy in palliating patients with nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 23(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Ortner Marianne E.J., Frieder berr Karelcaca, et al. Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Jianfeng, Shen Hongzhang, Jin Hangbin, et al. Treatment of unresectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma using hematoporphyrin photodynamic therapy: a prospective study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2016;16:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Zongyan, Jiang Xiaofeng, Xiao Hua, et al. Longterm results of ERCP or PTCSdirected photodynamic therapy for unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Surg. Endosc. 2020;8:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08095-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzalez-Carmona Maria Angeles, Bolch Maximilian, Jansen Christian, et al. Combined photodynamic therapy with systemic chemotherapy for unresectable cholangiocarcinoma. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019 doi: 10.1111/apt.15050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yunpeng Huang, Xiaoyu Li, Zijian Zhang, et al. Photodynamic therapy combined with ferroptosis is a synergistic antitumor therapy strategy. Cancers 15(20). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Dong Xiaoxv, Zeng Yawen, Zhang Zhiqin, et al. Hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy for the treatment of cancer: a review. J. Pharmacy Pharmacol. 2021;73(4) doi: 10.1093/jpp/rgaa018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demian van Straten, Vida Mashayekhi, Henriette S.de Bruijn, et al. Oncologic photodynamic therapy: basic principles, current clinical status and future directions. Cancers9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lan Ming, Kai Cheng, Yu Chen, et al. Enhancement of tumor lethality of ROS in photodynamic therapy. Cancer Med. 10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Marcin Olek, Agnieszka Machorowska-Pienia˙zek, Zenon P. Czuba, et al. Effect of Hypericin-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy on the Secretion of Soluble TNF Receptors by Oral Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 15(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Stockwell Brent R. Ferroptosis turns 10: emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022;14:185. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xin Chen, Rui Kang, Guido Kroemer, et al. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18(5). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Jiashuo Zheng, Marcus Conrad. The Metabolic Underpinnings of Ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 32(6). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Jianbing Du, Zhuo Wan, Cong Wang, et al. Designer exosomes for targeted and efficient ferroptosis induction in cancer via chemo-photodynamic therapy. Theranostics 11(17). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Xuan Wang, Yuting Ji, Jingyi Qi, et al. Mitochondrial carrier 1 (MTCH1) governs ferroptosis by triggering the FoxO1-GPX4 axis-mediated retrograde signaling in cervical cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 14(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Chen Peng, Li Xuejie, Zhang Ruonan, et al. Combinative treatment of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics. 2020;10(11):5107–5119. doi: 10.7150/thno.44705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lei Guang, Zhuang Li, Gan Boyi, et al. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2022;7:22. doi: 10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Min Lu, Xinglei Qin, Yajun Zhou, et al. Long non-coding RNA LINC00665 promotes gemcitabine resistance of Cholangiocarcinoma cells via regulating EMT and stemness properties through miR-424-5p/BCL9L axis. Cell Death Dis. 12.1:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Shuhang Liang, Hongrui Guo, Kun Ma, et al. A PLCB1–PI3K–AKT signaling axis activates EMT to promote cholangiocarcinoma progression. Cancer Res. 81.23:5889–5903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Sun Lulu, Dong Hongliang, Zhang Weiqun, et al. Lipid peroxidation, GSH depletion, and SLC7A11 inhibition are common causes of EMT and ferroptosis in A549 cells, but different in specific mechanisms. DNA Cell Biol. 2021;40(2) doi: 10.1089/dna.2020.5730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai Jiayang, Ye Zhang, Hu Yuanyuan, et al. Fatostatin induces ferroptosis through inhibition of the AKT/mTORC1/GPX4 signaling pathway in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14 doi: 10.1038/s41419-023-05738-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shan Lei, Wenpeng Cao, Zhirui Zeng, et al. JUND/linc00976 promotes cholangiocarcinoma progression and metastasis, inhibits ferroptosis by regulating the miR-3202/GPX4 axis. Cell Death Dis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Shui Sufang, Zhao Zenglu, Wang Hao, et al. Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation initiated by photodynamic therapy drives a distinct ferroptosis-like cell death pathway. Redox Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kojima Y., Tanaka M., Sasaki M., et al. Induction of ferroptosis by photodynamic therapy and enhancement of antitumor effect with ferroptosis inducers. J. Gastroenterol. 2023;59(2) doi: 10.1007/s00535-023-02054-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurisic V., Bogdanovic G.T., Jakimov D., et al. Modulation of TNF-alpha activity in tumor PC cells using anti-CD45 and anti-CD95 monoclonal antibodies. Cancer Lett. 2004;214(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jurisic V., Srdic-Rajic T., Konjevic G., et al. TNF-α induced apoptosis is accompanied with rapid CD30 and slower CD45 shedding from K-562 cells. J. Membr. Biol. 2011;239(3):115–122. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jurisic V., Bumbasirevic V., Konjevic G., et al. TNF-α induces changes in LDH isotype profile following triggering of apoptosis in PBL of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Ann. Hematol. 2004;83(2):84–91. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0731-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.E. Buytaert, J.Y. Matroule, S. Durinck, et al. Molecular effectors and modulators of hypericin-mediated cell death in bladder cancer cells. Oncogene 27(13). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Zhao L.P.,Chen S.Y.,Zheng R.R.,et al. Photodynamic therapy initiated ferrotherapy of self-delivery nanomedicine to amplify lipid peroxidation via GPX4 inactivation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14(48). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Yin Weimin, Chang Jiao, Sun Jiuyuan, et al. Nanomedicine-mediated ferroptosis targeting strategies for synergistic cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2023;11(6):1171–1190. doi: 10.1039/d2tb02161g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.AlAsmari Abdullah F., Ali Nemat, AlAsmari Fawaz, et al. Elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying sorafenibinduced hepatotoxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/7453406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tewari Devesh, Patni Pooja, Bishayee Anusha, et al. Natural products targeting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in cancer: a novel therapeutic strategy. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022;80(0):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Yilei, Swanda Robert V., Nie Litong, et al. mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12(1):1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21841-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fan Lili, Lei Han, Lin Ying, et al. Hotair promotes the migration and proliferation in ovarian cancer by miR2223p/CDK19 axis. CMLS. 2022;5:79. doi: 10.1007/s00018-022-04250-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian Hongwei, Wang Fang, Deng Yuan, et al. Centromeric protein K (CENPK) promotes gastric cancer proliferation and migration via interacting with XRCC5. Gastric Cancer. 2022;25(5):879–895. doi: 10.1007/s10120-022-01311-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mühleisen Laura, Alev Magdalena, Unterweger Harald, et al. Analysis of hypericin-mediated effects and implications for targeted photodynamic therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18(7) doi: 10.3390/ijms18071388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alzahrani Ali S. PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors in cancer: at the bench and bedside. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019;59:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lisha Li, Dongfeng Song, Ling Qi, et al. Photodynamic therapy induces human esophageal carcinoma cell pyroptosis by targeting the PKM2/caspase-8/caspase-3/GSDME axis. Cancer Lett. 520:143–159. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Hanada Yuri, Pereira Stephen P, Brian Pogue, et al. EUS-guided verteporfin photodynamic therapy for pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021;94(1):179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2021.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Zi-jian, Huang Yun-peng, Li Xiao-xue, et al. A novel ferroptosis-related 4-gene prognostic signature for cholangiocarcinoma and photodynamic therapy. Front. Oncol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.747445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]