Abstract

Background:

The effect of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) on gait in Parkinson’s Disease (PD) is poorly understood. Kinematic studies utilizing quantitative gait outcomes such as speed, cadence, and stride length have shown mixed results and were done mostly before and after acute DBS discontinuation.

Objective:

To examine longitudinal changes in kinematic gait outcomes before and after DBS surgery.

Method:

We retrospectively assessed changes in quantitative gait outcomes via motion capture in 22 PD patients before and after subthalamic (STN) or globus pallidus internus (GPi) DBS, in on medication state. Associations between gait outcomes and clinical variables were also assessed.

Result:

Gait speed reduced from 110.7 ± 21.3 cm/s before surgery to 93.6 ± 24.9 after surgery (7.7 ± 2.9 months post-surgery, duration between assessments was 15.0 ± 3.8 months). Cadence, step length, stride length, and single support time reduced, while total support time, and initial double support time increased. Despite this, there was overall improvement in the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale-Part III score “on medication/on stimulation” score (from 19.8 ± 10.7–13.9 ± 8.6). Change of gait speed was not related to changes in levodopa dosage, disease duration, unilateral vs bilateral stimulation, or target nucleus.

Conclusion:

Quantitative gait outcomes in on medication state worsened after chronic DBS therapy despite improvement in other clinical outcomes. Whether these changes reflect the effects of DBS as opposed to ongoing disease progression is unknown.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Gait, Kinematics, Motion Analysis, Deep Brain Stimulation

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder, which manifests with motor features of tremor, bradykinesia, rigidity as well as gait abnormalities. Difficulties with ambulation in particular lead to significant morbidity and disability in this population [1]. Gait abnormalities have been linked to increased risk of falls. Specifically, slower gait speed, decreased cadence, shorter step length and shorter stride length are linked to increased fall risk [2]. Falls have been associated with increased morbidity and mortality in addition to higher health care costs [3]. The effect of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) on gait disorders is less well defined unlike its effect on tremor or bradykinesia [4,5]. Routine clinical assessments of gait rely primarily on observation-based scoring such as the Movement Disorders Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS Part III)[6] which is coarse and less sensitive given that walking is a highly complex function. The limitations are due to restrictive scoring of the gait parameters (range from 0-no gait abnormality to 4 – inability to walk or only with person’s assistance). This scoring does not allow examination of more subtle differences in gait such as changes in gait speed or stride.

To improve precision and accuracy of gait assessments, objective measures such as instrumented walkways, wearable sensors, and motion capture systems have been utilized in clinical research studies [7]. Several studies have utilized motion capture to understand gait dynamics in PD [8,9] however only few studies have examined gait changes before and after surgery using motion analysis especially during on medication/on stimulation states[10-14]. Additionally, such studies have shown mixed results so far. While DBS was seen to improve gait speed [12,15,16] in some studies, others alluded to worsened gait speed [11]. Rocchi et al.[11] demonstrated that combined effect of DBS and levodopa was less effective in improving velocity in PD patients with subthalamic nucleus (STN) stimulation, compared to pre-surgical on medication state. The study highlighted possible interaction of DBS with levodopa action. We aim to describe longitudinal changes in gait parameters in PD patients that have undergone DBS, and to determine whether changes in levodopa dosage after surgery relate to changes in gait velocity.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

We retrospectively reviewed our institution’s clinical motion capture database between 2015 and 2018. Cases were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) diagnosis of PD made by a movement disorder neurologist, and 2) availability of both pre-surgical and post-surgical kinematic gait data. Patients with comorbidities, such as prior strokes, essential tremor, major musculoskeletal or neurological disorders that could affect gait, or those needing assistive devices to ambulate were excluded. A total of 22 cases were available for analysis. The retrospective analysis of clinical data with a waiver of consent was approved by the Emory University IRB.

2.2. Clinical and demographic variables

Clinical covariates included age, sex, disease duration, levodopa equivalent dose (LED) [17], and duration between the pre- and post-surgical gait assessments. Sites of implant i.e. STN vs. globus pallidus internus (GPi), as well as hemisphere involved (right, left, or bilateral implants) were also noted. Because the clinic visits coincided with the transition from the Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale-Part III score (UPDRS-III) to the Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale-Part III score (MDS-UPDRS-III) in our clinic, symptom severity was assessed with the UPDRS-III for all pre-surgical visits, but with the MDS-UPDRS-III for 17/22 of post-surgical visits. All UPDRS-III scores were converted to MDS-UPDRS-III scores prior to analysis using established formulas [18].

2.3. Clinic visits and testing states

Patients were assessed for gait outcomes at two visits: pre-surgical and post-surgical. Pre-surgical gait assessments were performed in the “on medication state.” Post-surgical gait assessments were performed in the “on stimulation” and “on medication” state.

Patients were assessed for motor symptom severity with the UPDRS-III / MDS-UPDRS-III during a separate clinic visit from motion capture gait assessments. Average time between pre-surgical gait ( motion capture) and clinical motor score assessments was 17 days and for post-surgical assessments the difference was 1.5 days (2 patients were evaluated on different days and the remainder were evaluated on the same day). At the pre-surgical clinical assessment visits, patients were assessed in the “off medication” state and the “on medication” state. At post-surgical visits, patients were assessed in the “off medication/off stimulation”, “off medication/on stimulation”, and “on medication/on stimulation” states. For “off medication” exams, patients withheld dopaminergic medications overnight (typically 12 h). For stimulation exams, a 15-minute wash-out and wash-in periods were applied. For “on medication” exams, patients took their regular morning dose of PD medications, and exams were performed after the onset of action which was typically 30–90 min.

2.4. Gait assessments

At each gait assessment, patients were assessed with a full-body, 3D optical motion capture system (Motion Analysis Corporation, Santa Rosa, CA) using a customized configuration of 60 reflective kinematic markers. Average (Standard Deviation) time between the two gait analyses was 15.0 (3.8) months. Time from first gait analysis to surgery was 7.3 (3.2) months and from surgery to the second gait analysis was 7.7 (2.9) months. Patients completed a standardized battery of gait tasks including multiple replicates (5 times) of walking at self-selected speed over a distance of 4.7 m. Walking segments excluded turns and were used to obtain nine standard gait outcomes for each lower limb, including gait speed, cadence, step length, stride length, total, single, and double support time, and step width using OrthoTrak 6.6.0 (See Supplement Table S1 and Fig. S1). Videos of the walking segments (excluding turns) were reviewed by the author (R.T) to verify occurrence of festination or freezing of gait during this task. Lab setting was the same for both pre and post-surgical testing conditions.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBMM SPSS Statistics 6, JMP 15.1.0 and R Studio Version 1.3. For each patient, gait parameters of both legs were averaged prior to analysis. Statistical significance of changes in study variables from pre- to post-surgical visits were assessed with paired t-tests for continuous variables and Wilcoxon signed-ranks tests for ordinal variables. Normality was tested using Shapiro-Wilk test (p > 0.05 for all variables except post-surgical step width) and homogeneity of variance, using Levene test for gait variables (p > 0.05). Sub-group analyses were conducted for STN target, GPi target, unilateral implants, and bilateral implants. Further analysis of individual sides (right limb and left limb) was conducted (see Supplement Table S7). In order to compare the relative changes in each study variable, changes from pre-surgical to post-surgical were expressed as average differences divided by standard deviation (“effect size,” referred to as Cohen’s d; [19], see Supplement table S6). Power analysis was included for each gait variable and sub-group analysis (Supplement table S6). Correlations between changes in gait speed and changes in clinical variables including disease duration, change in LED, and change in MDS-UPDRS-III score were assessed with Spearman’s correlations. Tests were considered significant at α = 0.006 after correcting for type-I error using Bonferroni procedure (8 comparisons). Numerical values of study variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

3. Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics for 22 patients included in the analysis are shown in Table 1. No significant changes were observed in MDS-UPDRS part III off medication scores from pre- to post-surgery (p = 0.23) in the absence of stimulation. As expected, “off medication/on stimulation” MDS-UPDRS part III was significantly improved (23%, p < 0.001) compared to pre-surgical “off medication” testing. “On medication/on stimulation scores” were also significantly improved (30%, p = 0.004) compared to pre-surgical “on medication” testing. LED was also significantly reduced post-surgically (31%, p < 0.001; Table 2). No changes were observed in the MDS-UPDRS III gait score on medication post-surgically.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristic | N = 22 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 61 ± 8 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 5 |

| Male | 17 |

| Disease duration, years | 10.4 ± 3.8 |

| Implant target | |

| GPi | 13 |

| Unilateral | 8 |

| Bilateral | 6 |

| STN | 9 |

| Unilateral | 6 |

| Bilateral | 3 |

| Time between gait assessments, months | 15.0 ± 3.8 |

| Time between surgery and follow up gait assessment, months | 7.7 ± 2.9 |

Abbreviations: GPi, globus pallidus internus; STN, subthalamic nucleus.

Table 2.

Clinical variables before and after surgery (N = 22).

| Pre- surgical |

Post- surgical |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levodopa equivalent daily dose, mg | 1392 ± 500 | 963 ± 505 | < <0.001 |

| MDS-UPDRS-III off med / off stim | 47.1 ± 14.4 | 44.3 ± 11.9a | 0.231 |

| MDS-UPDRS-III off med / on stim | 24.8 ± 10.7b | < <0.001† | |

| MDS-UPDRS-III on med / on stim | 19.8 ± 10.7 | 13.9 ± 8.6 | 0.004 |

| MDS-UPDRS-III gait score on med / on stim | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | ≈ 1.0‡ |

All p values from paired t-tests calculated between pre-surgical and post-surgical except †paired t-test vs. pre-surgical off med; ‡Wilcoxon signed-rank test. aN = 20. bN = 19. Note: off stim and on stim refer to the post-surgical visit only; e.g., on med / on stim refers to on medication at the pre-surgical visit and on medications and on stimulation at the post-surgical visit.

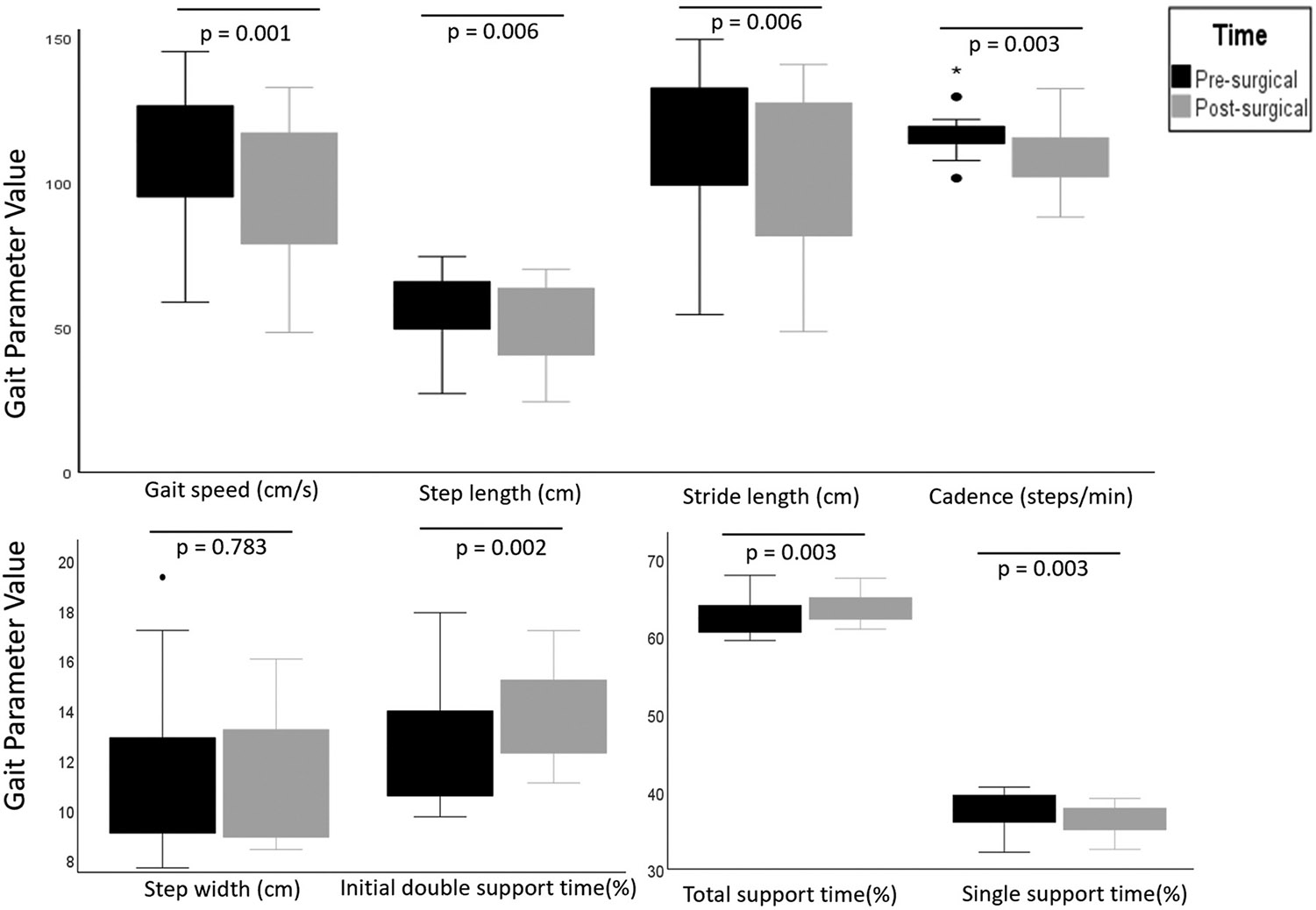

Significant change was observed in most gait outcome measures between pre-surgical “on medication” and post-surgical “on medication/on stimulation” states (Fig. 1). Average gait speed decreased from 110.7 (21.3) to 93.57 (24.9) cm/s (p = 0.001). Cadence decreased from 116.5 (7.7) to 110.3 (10.7) steps per minute (p = 0.003). Step length and stride length were reduced (57.2 (11.2) to 51.0 (13.3) cm, p = 0.006, and 114.6 (22.6) to 102.0 (26.7) cm, p = 0.006 respectively). Further, total support time and initial double support time was increased (62.43% (2.1) to 63.83% (1.7), p = 0.003% and 12.6% (2.1) to 14% (1.7), p = 0.002; respectively). Single support time was decreased from 37.56% (2.08) to 35.17% (1.74); p = 0.003. This implies reduction in swing phase of the gait cycle post-surgery. Step width was unchanged. Pre- and post-surgical video review of walking task didn’t reveal festination or freezing of gait for any subject.

Fig. 1.

Boxplot demonstrating distribution of gait parameters pre- and post-surgery. Dots and asterisk represent outliers. p < 0.006 significant.

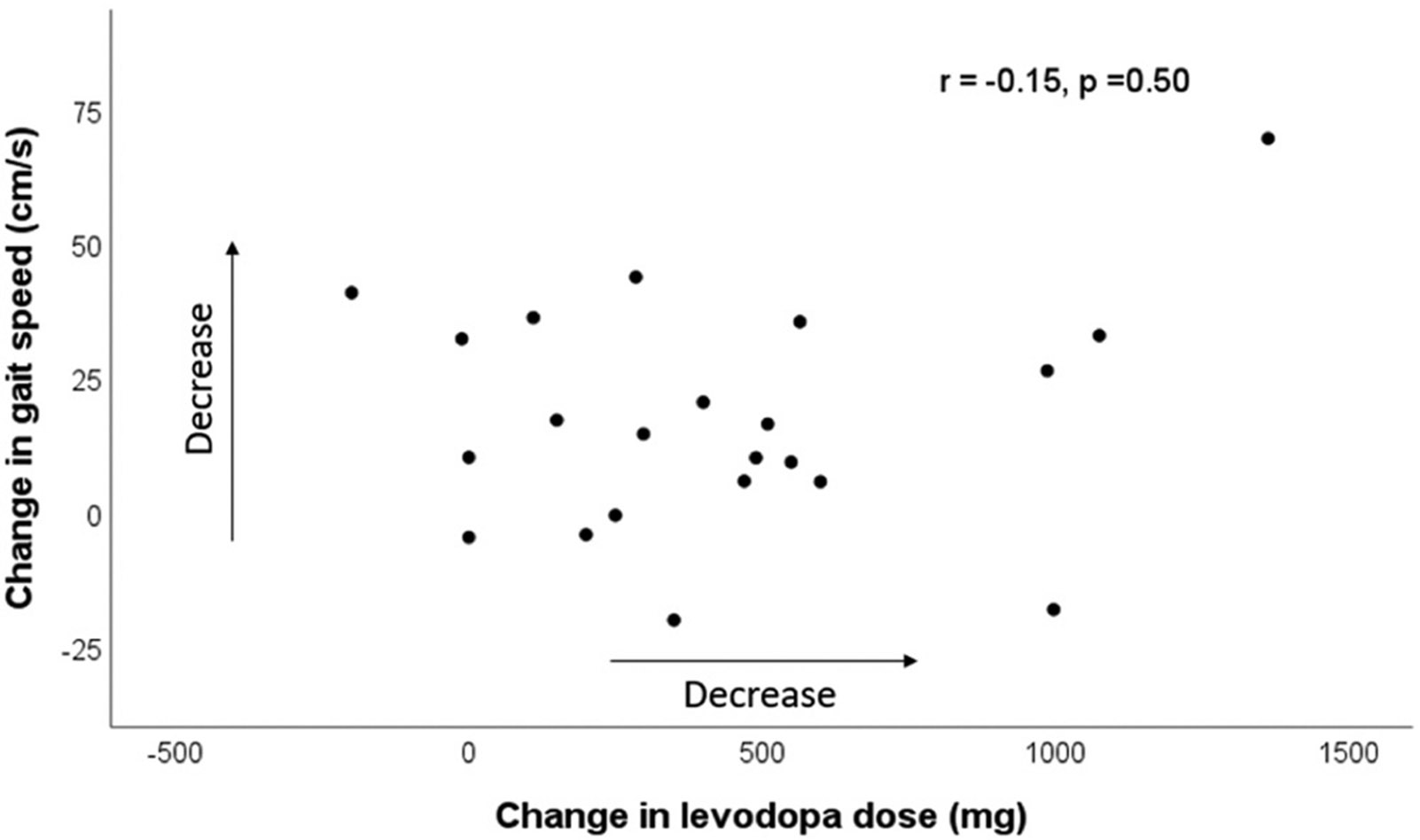

There was no correlation between change in LED and change in gait speed (r = −0.15, p = 0.5) (Fig. 2). There were also no significant correlations between change in gait speed and other clinical variables including age, disease duration, duration between the two kinematic analysis, or motor scores (not shown).

Fig.,. 2.

Change in gait speed (presurgical – postsurgical speed) and change in levodopa dose (presurgical – postsurgical levodopa equivalent dose) does not show correlation. Arrows indicate decrease in speed and levodopa dose.

Sub-group evaluations for only GPi group (n = 13) and another for only STN group (n = 9) did not reveal changes of gait variables, likely due to reduced statistical power (post-hoc power analysis was <0.8 for most variables in the sub-group analyses). There was a trend for significantly decreased cadence in the STN group post-surgically (118.25 steps/min to 109.54 steps /min; p = 0.007). Similarly, no statistically significant changes in gait variables were observed in stratified analyses considering subgroups of unilateral or bilateral implants (Supplement tables S2-5). Our sample had greater unilateral cases compared to bilateral implants. A pre- vs post-surgical comparison of right and left leg showed comparable results including reduction in gait speed, and stride length (Supplement table S7). However subtle differences between right and left sides were noted when examining step length (significant reduction noted in left limb but not in the right limb), total support time (significant increase in the left limb but not in the right limb), and single support time (significant decrease in the right limb but not in the left limb).

4. Discussion

In this retrospective, clinical study we show overall worsening of kinematic gait parameters despite improved MDS-UPDRS motor scores less than a year after DBS surgery. We observed decreased gait speed, step length, stride length and cadence, increased total support as well as double support time. This overall gait change did not correlate to the degree of reduction of the levodopa dose after surgery. Although significant gait changes were not seen when considering only specific DBS target or lead laterality, this was likely due to smaller sample size for sub-group analyses. Despite changes of most gait variables step width did not change in the present study. Prior studies have indicated step width variability is an indicator of fall risk [20] however, in our study we did not evaluate variability and are unable to comment whether our patients’ fall risk changed in this context.

There have been several reports of mostly beneficial DBS effect on overall gait speed when patients are studied postoperatively, off and on stimulation, in the off medication clinical state [7,12,21-23]. While one study failed to show any acute benefit of STN stimulation on gait speed and stride length [24], others have shown significant benefit in gait speed and stride length [15,16]. Interestingly, Ferrain at al. study showed improvement in gait parameter was better with stimulation and medication combined compared to individual therapies alone [15]. These studies, aside from providing mixed results regarding DBS effect on gait, lack pre-surgical baseline. This limitation hinders our understanding of gait changes post-surgery and only identifies acute effects of stimulation.

Longitudinal studies examining gait changes pre- and post- DBS surgery also demonstrate mixed results. Rocchi et al. [11] examined effects of bilateral STN or GPi stimulation (n = 29) at baseline and 6 months post procedure. Their study demonstrated worsened gait speed in STN group. It is unclear if this was associated with changes in levodopa dosing. Some studies did not show any changes between pre-surgical and post-surgical gait speeds at 6-month followup [10,14]. In contrast, other longitudinal studies [12,13] have demonstrated improved gait speed post-surgery. It is important to note that studies showing gait improvement were followed up to 3months, while studies that showed no significant improvement/worsening were followed for > 3months (i.e 6 months).

Gait worsening in non-surgical PD patients has been observed over time periods usually spanning more than a year [25]. This points to a gradual worsening of gait, which will likely not be captured by studies that follow changes for shorter duration. The above studies reported gait outcomes at shorter duration i.e only 3 or 6 months post-surgery compared to the present study where time to follow-up was approximately eight months after surgery. The length of follow up may therefore account for gait worsening observed in our study. In summary, based on the above mentioned studies, it appears that DBS may improve gait when comparing off stimulation to on stimulation states acutely, but over time the gait worsens compared to pre-surgical baseline. Importantly, our study shows that worsening of kinematic parameters occurred less than a year after surgery, even though gross clinical gait assessment (MDS-UPDRS gait score) showed no change at this time. Quantitative gait parameters may be early indicators of subtle decline that eventually becomes clinically meaningful. It is unclear if this worsening is due to surgical implant, stimulation, or natural disease progression combined with the lack of DBS effect on axial symptoms such as gait and balance [26]. Our group analysis showed that dopaminergic medication reduction post-surgery did not relate to gait worsening, but we cannot rule out that medication effect was not significant in some individual patients.

Gait parameters are also influenced by physical therapy and gait training, which has not been accounted for in any of the studies that examined gait speed using kinematic data. Since the present study is retrospective, physical therapy could not be used as a controlled intervention and hence potential influence of physical therapy in addition to DBS therapy remains undetermined [25,27].

A meta-analysis conducted comparing gait speed with age matched healthy controls showed that PD patients had reduced gait speed by 0.17 m/s on average [28]. Although disease progression may have contributed to worsening gait speed seen in our patient population, the decrease of 0.134 m/s per year was greater than the speed changes reported in literature. Ellis et al. reported speed reduction by 0.04 m/s per year (in patients with average MDS-UPDRS part III of 32) [29], Hobert et al. reported a decrease of 0.034 m/s per year in early and intermediate PD [30], and Wilson et al. reported 0.0124 m/s per year reduction in speed (average MDS-UPDRS part III of 25) [31]. Of note, Hass et al. used distribution analysis to quantify the change in gait speed, which when applied to our population, was quantified as a “moderate” reduction in speed [32]. It is possible that gait velocity decreases more rapidly in surgical candidates with advanced disease compared to patients with milder disease as reported in literature. However, a large change in speed in our study due to surgical intervention and/or chronic stimulation cannot be completely ruled out. Worsened akinesia and gait with stimulation of anterior or dorsal aspect of STN (anterior zona incerta and Forel fields H2) has been reported [33-35]. Freezing of gait as well as increased falls have been associated with STN stimulation in some patients [36,37]. A proposed theory is that the involvement of pallidothalamic and pallido-pedunculopontine nucleus fibers could lead to worsening of akinesia and stimulation-induced gait disturbances [33].

There are several limitations to this retrospective clinical study. A major limitation was lack of a control PD group, which could help address the effect of disease progression on worsening of gait metrics. However, it would be difficult to assemble a comparable cohort of patients with similar disease severity who are DBS candidates but do not undergo surgery. Another limitation is potential sampling bias since gait testing was performed as part of routine clinical care (our clinic protocol is that all patients should undergo gait analysis before and approximately six months after surgery), and patients with postoperative gait difficulties may have preferentially presented for postoperative gait testing. There were additional 91 patients who underwent DBS procedure for PD during the same period but did not meet criteria of having both pre- and post-surgery gait analysis. Gait testing was not performed at the same time as MDS-UPDRS exam, which may have led to discrepancy of improved exam yet worsened gait analysis. Patients were in their usual “on medication” state when they presented for gait analysis, but we were unable to determine where in the medication cycle they were, whereas MDS-UPDRS exam was performed approximately 60 min after medication intake. There was also lack of gait testing in the “off medication” state. Additionally, we do acknowledge a small sample size, which is inadequate to adequately analyze sub target differences i.e between STN vs GPi, and unilateral vs bilateral groups.

5. Conclusion

Our results demonstrate decreased gait speed and other quantitative gait metrics in the on medication state following DBS surgery despite overall improvement in motor exam. No specific clinical factors were identified that correlated with this worsening, including target nucleus, lead laterality, or medication reduction. Previous studies have shown that gait and balance steadily worsen after DBS, which was attributed to disease progression. However, our study demonstrates that this worsening occurs less than a year after surgery, in at least a subset of patients who undergo DBS procedure. Efficacy and need for DBS in PD therapy is undeniable as can be seen with excellent tremor, bradykinesia as well as rigidity control. We hope the current study provides direction for prospective studies to address these issues, and investigate if early physical therapy and other interventions may preempt this decline in post-surgical PD patients. This will impact clinical care including use of fall precautions in this patient population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

R.T has received royalties from UpToDate. P.T has been supported by Parkinson Foundation Fellowship grant. J.L.M has received funding from McCamish Foundation and receives consulting fees from Biocircuit technologies. C.D.E received funding from Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and royalties from UpToDate. There are no other financial disclosures by the authors. S.A.F has been supported by Sartain Lanier Family Foundation. He has received honoraria by Lundbeck, Sunovion, Biogen, Acorda, Alterity. S.A.F has current grant funding through Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Sun pharmaceuticals Advanced Research Company, Biohaven, Impax, Sunovion Therapeutics, Neuro-crine, Vaccinex, Voyager, Addex Pharma S.A, Prilenia Therapeutics CHDI Foundation, Michael J. Fox Foundation, NIH (U10 NS077366), Parkinson Foundation. S.A.F receives royalties from Demos, Blackwell Futura, Springer for textbooks, UpToDate, other Signant Health (Bracket Global LLC), CNS ratings LLC.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Project has been partially funded by (NIH/NINDS K23 NS097576). No other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethical compliance statement

Emory University Institutional review board approved the study. Informed patient consent was not necessary for this work. All authors have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

RT: Conception, Organization, Execution, Design, Execution, Writing of the first draft. JLM: Execution, Review and Critique, Review and Critique. SAF: Conception, Review and Critique, Review and Critique. CDE: Review and Critique, Review and Critique. DB: Execution, Review and Critique, Review and Critique. PT: Execution, Review and Critique, Review and Critique. SM: Conception, Execution, Design, Execution, Review and Critique, Review and Critique.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.12.002.

References

- [1].Diem-Zangerl A, Seppi K, Wenning GK, Trinka E, Ransmayr G, Oberaigner W, Poewe W, Mortality in Parkinson’s disease: a 20-year follow-up study, Mov. Disord 24 (2009) 819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Creaby MW, Cole MH, Gait characteristics and falls in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Park. Relat. Disord 57 (2018) 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hartholt KA, Lee R, Burns ER, van Beeck EF, Mortality from falls among US adults aged 75 years or older, 2000-2016, JAMA 321 (2019) 2131–2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fasano A, Aquino CC, Krauss JK, Honey CR, Bloem BR, Axial disability and deep brain stimulation in patients with Parkinson disease, Nat. Rev. Neurol 11 (2015) 98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hallett M, Litvan I, Evaluation of surgery for Parkinson’s disease: a report of the therapeutics and technology assessment subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology, Task. Force Surg. Park. ’S. Dis. Neurol. 53 (1999) 1910–1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stern MB, Dodel R, Dubois B, Holloway R, Jankovic J, Kulisevsky J, Lang AE, Lees A, Leurgans S, LeWitt PA, Nyenhuis D, Olanow CW, Rascol O, Schrag A, Teresi JA, van Hilten JJ, LaPelle N, Movement Disorder Society URTF, Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results, Mov. Disord 23 (2008) 2129–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Roper JA, Kang N, Ben J, Cauraugh JH, Okun MS, Hass CJ, Deep brain stimulation improves gait velocity in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis, J. Neurol 263 (2016) 1195–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Murray MP, Sepic SB, Gardner GM, Downs WJ, Walking patterns of men with parkinsonism, Am. J. Phys. Med 57 (1978) 278–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Morris M, Iansek R, McGinley J, Matyas T, Huxham F, Three-dimensional gait biomechanics in Parkinson’s disease: evidence for a centrally mediated amplitude regulation disorder, Mov. Disord 20 (2005) 40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cebi I, Scholten M, Gharabaghi A, Weiss D, Clinical and kinematic correlates of favorable gait outcomes from subthalamic stimulation, Front Neurol. 11 (2020), 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rocchi L, Carlson-Kuhta P, Chiari L, Burchiel KJ, Hogarth P, Horak FB, Effects of deep brain stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus or globus pallidus internus on step initiation in Parkinson disease: laboratory investigation, J. Neurosurg 117 (2012) 1141–1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Krystkowiak P, Blatt JL, Bourriez JL, Duhamel A, Perina M, Blond S, Guieu JD, Destee A, Defebvre L, Effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation and levodopa treatment on gait abnormalities in Parkinson disease, Arch. Neurol 60 (2003) 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Allert N, Volkmann J, Dotse S, Hefter H, Sturm V, Freund HJ, Effects of bilateral pallidal or subthalamic stimulation on gait in advanced Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord 16 (2001) 1076–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rochester L, Chastin SF, Lord S, Baker K, Burn DJ, Understanding the impact of deep brain stimulation on ambulatory activity in advanced Parkinson’s disease, J. Neurol 259 (2012) 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ferrarin M, Rizzone M, Bergamasco B, Lanotte M, Recalcati M, Pedotti A, Lopiano L, Effects of bilateral subthalamic stimulation on gait kinematics and kinetics in Parkinson’s disease, Exp. Brain Res 160 (2005) 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rizzone MG, Ferrarin M, Lanotte MM, Lopiano L, Carpinella I, The dominant-subthalamic nucleus phenomenon in bilateral deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease: evidence from a gait analysis study, Front Neurol. 8 (2017), 575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tomlinson CL, Stowe R, Patel S, Rick C, Gray R, Clarke CE, Systematic review of levodopa dose equivalency reporting in Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord 25 (2010) 2649–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Tilley BC, Calibration of unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores to Movement Disorder Society-unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale scores, Mov. Disord 27 (2012) 1239–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cohen J, A power primer, Psychol. Bull 112 (1992) 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Maki BE, Gait changes in older adults: predictors of falls or indicators of fear, J. Am. Geriatr. Soc 45 (1997) 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cossu G, Pau M, Subthalamic nucleus stimulation and gait in Parkinson’s Disease: a not always fruitful relationship, Gait Posture 52 (2017) 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mera TO, Filipkowski DE, Riley DE, Whitney CM, Walter BL, Gunzler SA, Giuffrida JP, Quantitative analysis of gait and balance response to deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease, Gait Posture 38 (2013) 109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kaufman K, Miller E, Kingsbury T, Russell Esposito E, Wolf E, Wilken J, Wyatt M, Reliability of 3D gait data across multiple laboratories, Gait Posture 49 (2016) 375–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lohnes CA, Earhart GM, Effect of subthalamic deep brain stimulation on turning kinematics and related saccadic eye movements in Parkinson disease, Exp. Neurol 236 (2012) 389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Galna B, Lord S, Burn DJ, Rochester L, Progression of gait dysfunction in incident Parkinson’s disease: impact of medication and phenotype, Mov. Disord 30 (2015) 359–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Limousin P, Krack P, Pollak P, Benazzouz A, Ardouin C, Hoffmann D, Benabid AL, Electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in advanced Parkinson’s disease, N. Engl. J. Med 339 (1998) 1105–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Debu B, De Oliveira Godeiro C, Lino JC, Moro E, Managing gait, balance, and posture in Parkinson’s Disease, Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep 18 (2018), 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Zanardi APJ, da Silva ES, Costa RR, Passos-Monteiro E, Dos Santos IO, Kruel LFM, Peyre-Tartaruga LA, Gait parameters of Parkinson’s disease compared with healthy controls: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Sci. Rep 11 (2021), 752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ellis TD, Cavanaugh JT, Earhart GM, Ford MP, Foreman KB, Thackeray A, Thiese MS, Dibble LE, Identifying clinical measures that most accurately reflect the progression of disability in Parkinson disease, Park. Relat. Disord 25 (2016) 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hobert MA, Nussbaum S, Heger T, Berg D, Maetzler W, Heinzel S, Progressive gait deficits in Parkinson’s disease: a wearable-based biannual 5-year prospective study, Front Aging Neurosci. 11 (2019), 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wilson J, Alcock L, Yarnall AJ, Lord S, Lawson RA, Morris R, Taylor JP, Burn DJ, Rochester L, Galna B, Gait progression over 6 years in Parkinson’s disease: effects of age, medication, and pathology, Front Aging Neurosci. 12 (2020), 577435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hass CJ, Bishop M, Moscovich M, Stegemoller EL, Skinner J, Malaty IA, Wagle Shukla A, McFarland N, Okun MS, Defining the clinically meaningful difference in gait speed in persons with Parkinson disease, J. Neurol. Phys. Ther 38 (2014) 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fleury V, Pollak P, Gere J, Tommasi G, Romito L, Combescure C, Bardinet E, Chabardes S, Momjian S, Krainik A, Burkhard P, Yelnik J, Krack P, Subthalamic stimulation may inhibit the beneficial effects of levodopa on akinesia and gait, Mov. Disord 31 (2016) 1389–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Russmann H, Ghika J, Villemure JG, Robert B, Bogousslavsky J, Burkhard PR, Vingerhoets FJ, Subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in Parkinson disease patients over age 70 years, Neurology 63 (2004) 1952–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].van Nuenen BF, Esselink RA, Munneke M, Speelman JD, van Laar T, Bloem BR, Postoperative gait deterioration after bilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation in Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord 23 (2008) 2404–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Potter-Nerger M, Volkmann J, Deep brain stimulation for gait and postural symptoms in Parkinson’s disease, Mov. Disord 28 (2013) 1609–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tommasi G, Lopiano L, Zibetti M, Cinquepalmi A, Fronda C, Bergamasco B, Ducati A, Lanotte M, Freezing and hypokinesia of gait induced by stimulation of the subthalamic region, J. Neurol. Sci 258 (2007) 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.