Abstract

Background

Complementary feeding is crucial for infant growth, but poor hygiene during this period increases the risk of malnutrition and illness. In Ethiopia, national data on hygiene practices during complementary feeding, particularly among mothers of children aged 6–24 months, is limited. This study aims to synthesize existing data through a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the status of hygiene practices and identify key influencing factors, informing public health strategies to improve child health outcomes.

Methods

The systematic review methods were defined following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A search strategy was implemented using electronic databases (Medline, Global Health, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Embase, CINAHL, and Psyc INFO) as well as grey literature. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist was used to assess the quality of the studies. The meta-analysis was conducted using STATA 17 software to compute pooled prevalence and odds ratios (OR) for the determinant factors, with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

The systematic review and meta-analysis included six studies with 2,565 mothers. The overall pooled prevalence of hygienic practices during complementary feeding was 42% (95% CI: 35%–48%). Subgroup analysis showed a prevalence of 41% in southern Ethiopia and 39% in northern Ethiopia. Significant factors associated with better hygiene practices included having hand washing facilities near toilets (AOR: 4.6, 95% CI: 1.04–8.31, p = 0.01) and a positive attitude towards hygiene (AOR: 2.7, 95% CI: 1.07–4.69, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis found a low proportion of hygienic practices during complementary feeding in Ethiopia, with maternal attitude and access to hand washing facilities identified as key predictors. Training and counseling for mothers on safe food processing are recommended, along with further research on community interventions and the impact of socio-economic factors on hygiene practices.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-024-05319-4.

Keywords: Hygiene practice, Complementary feeding, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines complementary feeding (CF) as a process that starts when breast milk alone is no longer sufficient to meet the nutritional requirements of the infant [1]. An infant’s need for energy and nutrients exceeds that provided by breast milk at six months of age. The two years following the end of exclusive breastfeeding are crucial windows for a child’s growth and development [2]. Although breastfeeding begins at six months, it should be combined with safe, age-appropriate solid, semisolid, and soft foods that are stored and prepared hygienically and fed with clean hands [3].

According to the guidelines for infant and young child feeding indicators, complementary foods should be prepared, stored, and fed with clean hands and utensils rather than bottles and teat feedings [4]. This transition from exclusive breastfeeding to family foods is a critical period during which poor hygiene practices in complementary feeding significantly contribute to the high prevalence of gastrointestinal and respiratory illnesses in young children. Gastrointestinal diseases associated with preventable food-borne bacteria remain a global health challenge for children under two years of age [1], as their immature immune systems make them particularly vulnerable to infections with enteric pathogens [5].

Inappropriate feeding practices can lead to malnutrition in young children. Those who lack proper nutrition are more likely to develop infections, experience poor growth, and die nearly six times more often [1]. Approximately 600 million food-borne diseases are diagnosed worldwide annually, resulting in 420,000 deaths. Children under five account for 30% of these food-borne deaths, with more than 125,000 children in this age group dying each year from such diseases [3].

Infectious diseases caused by enteric pathogens associated with preventable food-borne bacteria remain a major global health threat for children under the age of two. Furthermore, dietary contamination results in diarrheal diseases that cause approximately 230,000 deaths every year [6]. Poor food hygiene practices contribute to 70% of diarrhea episodes in developing countries, leading to 88% of childhood deaths [7]. The process of feeding complementary foods is directly related to malnutrition, which is estimated to be the underlying cause of 45% of all deaths in children under five years of age; 41% of these deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, and 34% occur in South Asia [3, 8].

The transmission of food-borne diseases among children is exacerbated by unsafe food-handling practices by mothers and caregivers. Approximately 10% to 20% of food-borne disease outbreaks are attributed to unclean food preparation practices by mothers. The current prevalence of adequate complementary food introduction in Ethiopia is 13%, according to the 2019 Mini Demographic and Health Survey. Additionally, preventable bacterial pathogens are responsible for 43% of infant mortalities [9, 10].

Several interventions have been implemented in Africa and Ethiopia to improve hygiene practices during complementary feeding [11]. These interventions include community-based health education programs that focus on the importance of hand washing before food preparation and feeding. For example, programs that distribute hygiene kits and provide training sessions for mothers and caregivers on safe food handling practices have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing food-borne illnesses among young children [11]. Initiatives that promote the use of clean utensils and hygienic food storage are crucial for enhancing hygiene standards among caregivers [7, 12].

Despite these efforts, there is a scarcity of national evidence on the status of hygiene practices during complementary feeding, particularly among mothers of children aged 6–24 months, who often face challenges such as busy work schedules that limit their attention to food hygiene practices. The current study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to derive reliable and current figures regarding the hygiene practices during complementary feeding in Ethiopia.

Methods

Search strategy

The systematic review methods were defined following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [13] and were registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024498118). A search strategy was implemented using electronic databases (Medline, Global Health, Google Scholar, Web of Science, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO), while a grey literature search was conducted, no relevant articles were identified from that source. The search strategy was initially developed in Medline using MeSH subject headings combined with free-text terms related to the four search components: “hygiene practice,” “complementary feeding,” “associated factors,” and “mothers.” This strategy was then adapted for use in the other databases, covering studies published from January 1, 2013, to December 1, 2023. Additionally, further studies were retrieved through manual reference listing of included studies, relevant reviews, and consultations with experts in the field.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Study Design: Cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, case control studies or interventional studies.

Population: Studies involving mothers of children aged 6–24 months in Ethiopia.

Intervention/Exposure: Studies that assess hygiene practices during complementary feeding, including but not limited to hand washing practices, hygiene of feeding utensils, and food preparation hygiene.

Outcome Measures: Studies reporting on the prevalence of hygienic practices or factors influencing hygiene practices.

Language: Studies published in English.

Publication Date: Studies published from January 1, 2013, to December 1, 2023.

Exclusion criteria

Study Design: Qualitative studies, reviews, editorials, and opinion papers.

Population: Studies focusing on populations outside Ethiopia or mothers of children younger than 6 months or older than 24 months.

Outcome Measures: Studies not reporting relevant hygiene practices or not providing sufficient data on the prevalence or factors associated with hygiene practices.

Language: Studies published in languages other than English.

Studies unavailable as full-text articles were excluded.

Outcome definition

“Hygiene practice” was defined as actions taken to ensure food safety and cleanliness during the preparation and feeding of complementary foods, which may vary across studies.

Study selection procedures

The EndNote X9 citation manager was used to import studies from various sources and remove duplicates. Five review authors (EG, EKB, GAA, KS, and GL) independently evaluated the inclusion of all potential studies identified during the search process. Other review authors (ANY, AYB, AGB, and SKB) assessed the full text of the papers to determine eligibility for final inclusion in this study. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Ultimately, all qualifying papers with complete contents were reviewed.

A breakdown of the number of articles retrieved from each database is as follows: Medline yielded 39 articles, Global Health contributed 400 articles, Google Scholar returned 800 articles, and Web of Science provided 600 articles. Additionally, Embase yielded 400 articles, CINAHL contributed 200 articles, and Psyc INFO provided 126 articles. In total, 2565 articles were retrieved across all databases.

Data extraction and management

After studies were imported to EndNote v.9 and duplicates were removed, three independent reviewers (EGD, EKB, and GAA) extracted essential data independently using a standardized pre-specified data abstraction format. This format was designed to minimize disagreements in the extraction process. Any discrepancies were discussed, and if necessary, the second author of the study was consulted. The data abstraction format included the author, publication year, study design, study location, sample size, participants, magnitude, and associated factors (adjusted odds ratio with confidence intervals for the variables).

Quality assessment and risk of bias

To ensure the quality and reliability of the studies included in this review, we conducted a thorough quality assessment using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [14]. This checklist is freely available at the JBI Critical Appraisal Tools and provides a structured approach to assess the quality of qualitative research.

The review team (SKB, GL, and ANY) employed a blinded review approach to evaluate each study’s quality independently. Any discrepancies in the quality assessment were resolved through consultation with a second author (EKB). We considered studies that scored 5 or more on the JBI criteria as having good quality and eligible for inclusion in the review.

In addition to the quality assessment, we also conducted a risk of bias evaluation for each study. The JBI checklist helped identify key areas where potential bias may occur, such as in sampling methods, data collection techniques, and participant representation. Studies with a low risk of bias were prioritized in the final analysis, while studies with high or unclear risk were carefully examined for their impact on the review’s findings.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

The extracted data were entered into Microsoft Excel V.2016 and subsequently exported to STATA version 17 software for analysis. Descriptive analyses were conducted to summarize the characteristics of the included studies in summary tables and narrative text. Meta-analysis was performed, calculating the pooled estimate for the magnitude of physical activity using random-effects models with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed both subjectively, through visual inspection of forest plots [9], and objectively, using the Cochrane Q-test and I2 statistics [10]. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on sample size, publication year, and study area. The presence of publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and Egger’s and Begg’s statistical tests [15].

Heterogeneity across studies

To evaluate heterogeneity among the reported proportions, p-values from the I-squared test were computed. Significant heterogeneity was found among the included studies in this analysis (I2 = 92.34%, p < 0.001). Consequently, the pooled effects were estimated using a random-effects meta-analysis approach based on DerSimonian and Laird.

Additional analysis

To identify potential moderating factors that might account for variations in effect sizes among the primary studies, a subgroup analysis was conducted based on various characteristics, such as publication year, sample size, and study area. Furthermore, a meta-regression model was employed to investigate the sources of heterogeneity by utilizing the sample size, study area, and publication year of each study.

Result

Study characteristics

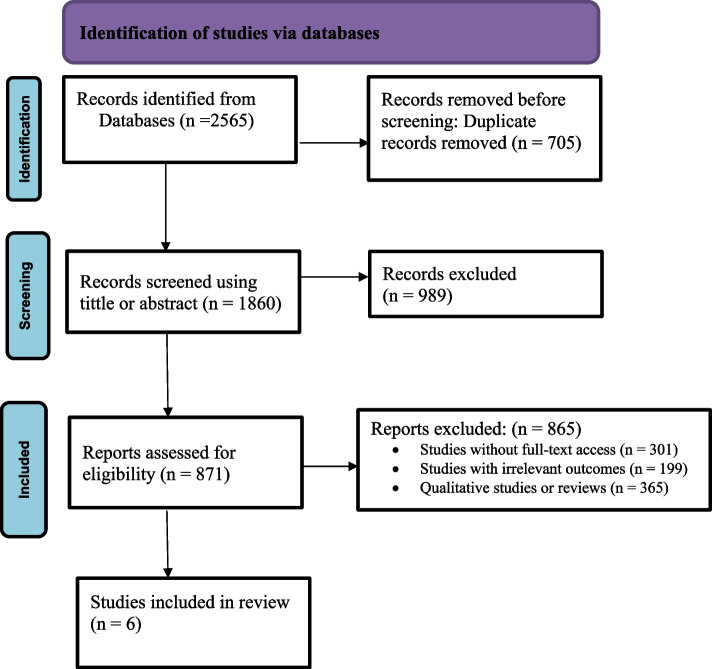

A total of 2565 articles from pre-selected database sources were manually searched. Duplication resulted in the removal of 705 articles. After that, 989 of them were eliminated after a review of the abstract and title. After 874 papers were assessed in their entirety, six of them qualified for a systemic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for selecting the studies for the review

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

The studies included in our systematic review and meta-analysis investigated hygiene practices during complementary feeding across diverse regions in Ethiopia. The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 297 to 604 participants, employing various sampling techniques, with systematic random sampling being the most commonly used. The prevalence of hygiene practices varied between studies, with the highest prevalence reported by Shumi Bedada et al. [16] at 55%, and the lowest reported by Habtam Ayenew Teshome et al. [5] at 34%. These studies were conducted in both urban and rural areas, which may explain some of the differences in reported prevalence (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis on hygiene practices during complementary feeding

| First Author | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Sampling Technique | Prevalence of HP (%) | JBI score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alelign Alemu Demmelash et al. (2020) [17] | Bahirdar curia | Cross-Sectional | 604 | Systematic Random Sampling | 39 | 8 |

| Shumi Bedada, et al. (2021) [16] | Bale Zone | Cross-Sectional | 517 | Systematic Random Sampling | 55 | 9 |

| Habtam Ayenew Teshome, et al. (2022) [5] | Tegedie District | Cross-Sectional | 576 | Systematic Random Sampling | 34 | 8 |

| Gizachew Ambaw Kassie, et al. (2023) [3] | Wolaita Sodo town | Cross-Sectional | 602 | Multi-Stage Random Sampling | 42 | 7 |

Risk of bias assessment was conducted for all included studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cross-Sectional Studies. The Table 2 below illustrates the quality appraisal of each study.

Table 2.

Quality appraisal of the included studies on hygiene practices during complementary feeding in Ethiopia

| Author (Year) | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alelign Alemu Demmelash et al. (2020) [17] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | A |

| Shumi Bedada et al. (2021) [16] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | B |

| Habtam Ayenew Teshome et al. (2022) [5] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | A |

| Gizachew Ambaw Kassie et al. (2023) [3] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | A |

Y = Yes; N = No; U = Unclear; NP = Not Applicable; A = High Quality; B = Moderate Quality

Criteria:

• Q1: Clear Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

• Q2: Sample Size Adequacy

• Q3: Appropriate Sampling Method

• Q4: Non-respondents Described

• Q5: Validity of Measurement Tools

• Q6: Statistical Analysis Appropriateness

• Q7: Outcomes Clearly Defined

• Q8: Ethical Considerations and Approvals

• Q9: Clear Data Interpretation

• Q10: Adequate Representation of Participants and Findings

Meta-analysis

Pooled prevalence of hygiene practice during complementary feeding

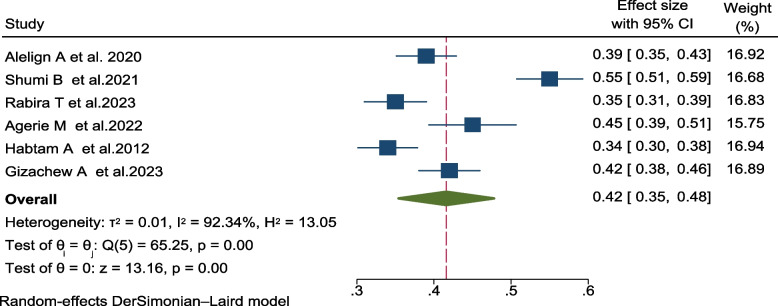

The overall pooled prevalence of HP was 42% (95% CI: 35%–48%, I2 = 92.34%, P < 0.001) using the random-effects model (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pooled prevalence of hygiene practice during complementary feeding

Subgroup analysis

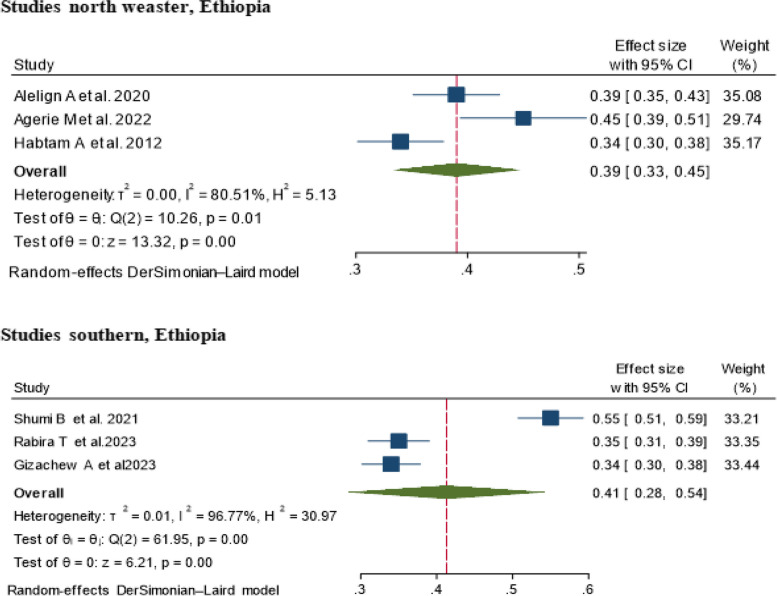

High heterogeneity was observed between studies (I2 = 92.34%). Consequently, a subgroup analysis was conducted based on the study area. The pooled prevalence of hygiene practices during complementary feeding in southern Ethiopia was 41% (95% CI: 28–54%, I2 = 96.77%, p < 0.001), while the pooled prevalence for northern Ethiopia was 39% (95% CI: 33–45%, I2 = 80.5, p < 0.001) using the random-effects model (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Subgroup analysis based on study area

Publication bias

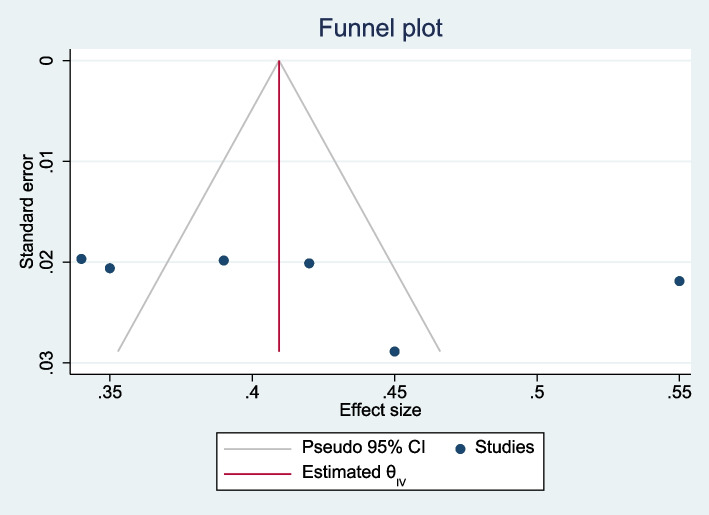

Publication bias was examined by the visual inspection of the funnel plot and it shows the presence of publication bias with the substantial asymmetry of the funnel plot (Fig. 4). However, we conduct objective Egger’s test and Begs to confirm the presence of publication bias. As a result, Egger’s test (p = 0.37), and Beg’s test (p = 0.1329) showed no small study effect. To treat publication bias we ran the nonparametric trim-and-fill analysis, but no imputed studies were observed.

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot to determine the presence of publication bias among 6 included studies

Meta-regression

Meta-regression was conducted by considering publication year and sample size as covariates using a random-effect model. The result showed that no heterogeneity was observed by the publication year (p = 0.52), sample size (p = 0.61), and study area (p = 0.52) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-regressions of the hygiene practice during complementary feeding among mother children aged 6–24 months in Ethiopia by sample size and publication year

| Covariate | β (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Publication year | 0.0059(-0.0126206to .0245669) | 0.52 |

| Sample size | 0..00017(-.0008599 to 0.0005085) | 0.61 |

Sensitivity analysis

We used a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis to investigate the source of variability in the study of hygiene practice during complementary feeding prevalence. Our sensitivity analysis revealed that the point estimated prevalence obtained when each study was excluded from the analysis fell within the confidence interval of the pooled prevalence. As a result, the pooled magnitude may be realistic. After excluding a single trial, the pooled prevalence ranged from 39% (35, 43) to 43% (36, 50) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Leave-one-out sensitivity analysis hygiene practice during complementary feeding among mother children aged 6–24 months in Ethiopia

Pooled factors associated with hygiene practice during complementary feeding

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, attitude and the presence of hand washing facilities near toilets were identified as significant factors associated with hygiene practices during complementary feeding. Analysis of studies revealed that respondents with a positive attitude toward hygienic practices were 2.7 times more likely (AOR: 2.7, 95% CI: 0.807—4.689, I2 = 0%, p < 0.001) to engage in good hygiene compared to those with a negative attitude. Additionally, respondents with hand washing facilities after toilet visits were 4.6 times more likely (AOR: 4.6, 95% CI: I2 = 31.4%, p = 0.01) to practice good hygiene during complementary feeding than those without such facilities (Table 4).

Table 4.

Pooled factors associated with hygiene practice during complementary feeding

| Factor Variable | Pooled Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) with 95% CI | I2 (%) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand washing facility near to the toilet | 4.677 (1.044, 8.309) | 31 | 0.01 |

| Attitude | 2.748 (1.07, 4.689) | 0.000 | < 0.05 |

Adjusted for factors including educational status, residence, and age

Discussion

This study estimated the pooled proportion of hygiene practices during complementary feeding among mothers with children aged 6 to 24 months in Ethiopia, which was found to be 42% (95% CI: 35%-48%). This aligns with findings from Bahir Dar Zuria [17], where similar attention to hygiene practices by policymakers and healthcare providers may have contributed to comparable results. However, the observed pooled proportion is higher than reported in comparable studies from Nigeria [18], where hygiene practice levels during complementary feeding were approximately 30%. Similarly, it is lower than findings from Uganda [19], which reported hygiene practice levels exceeding 50%. These differences highlight the influence of varying socioeconomic conditions, cultural practices, and infrastructure development across countries. Improved hygiene practices are crucial for child health, as they can influence nutritional outcomes and overall health [20]. However, this proportion is higher than in the Tegedie district [5], likely due to regional differences in socioeconomic status and access to resources. Conversely, the pooled prevalence in this study was lower than the findings from the Bale Zone [19], highlighting regional disparities in complementary food hygiene practices.

Our study found that mothers with hand washing facilities near their toilets were more likely to practice good hygiene, consistent with the findings from Tegedie [5]. These results emphasize the importance of access to proper sanitation facilities, which is particularly crucial in rural areas where hygiene resources may be limited [21]. International comparisons suggest similar challenges in other low-income countries such as India [22], where limited access to hygiene infrastructure is a primary barrier to improved hygiene practices during complementary feeding. Such cross-country similarities further reinforce the need for globally coordinated efforts to improve water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure. The disparities in hygiene practices between urban and rural areas can be attributed to varying levels of infrastructure development and resource availability. These findings are supported by similar studies from Kenya [23], which identified barriers such as limited resources and inadequate hygiene facilities. This cross-regional variation highlights the need for nuanced, context-specific interventions to bridge urban–rural gaps.

Additionally, mothers with positive attitudes toward hygiene were significantly more likely to adopt proper hygiene practices during complementary feeding. This aligns with studies from Ethiopia [12–14] and Kenya [23], where positive attitudes were linked to better hygiene practices. This is further supported by evidence from Bangladesh [16], where behavior-change interventions focusing on mothers’ attitudes significantly improved hygiene practices during complementary feeding. Such findings emphasize the importance of tailoring interventions to cultural contexts to maximize their effectiveness. These findings highlight the importance of education and awareness programs to improve hygiene behaviors, which are essential for child health.

In line with the WHO guidelines on Infant and Young Child Feeding (IYCF) [24], this study provides insight into how hygiene practices during complementary feeding can be improved through better access to WASH facilities, as well as through behavior change interventions targeting mothers’ attitudes. The evidence supports the need for integrated approaches that combine education on hygiene practices with improvements in infrastructure, especially in rural areas. In addition to improving WASH infrastructure, policymakers should focus on ensuring equitable access to sanitation facilities, especially in underserved areas, to facilitate better hygiene practices. Moreover, this study reinforces the global relevance of improving complementary feeding hygiene practices in line with WHO and UNICEF recommendations to reduce child morbidity and mortality associated with poor hygiene [25]. Furthermore, these findings can inform policymakers and healthcare providers on the critical need for targeted programs addressing the factors that influence hygiene behaviors, including access to hand-washing facilities and the promotion of positive attitudes toward hygiene.

While this study provides valuable insights into hygiene practices in Ethiopia, it also has global relevance, especially for low-resource settings. The factors influencing hygiene practices during complementary feeding, such as access to infrastructure and maternal attitudes, are similar in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [26–29]. By understanding the factors that influence hygiene practices during complementary feeding, this research can inform interventions aimed at improving maternal and child health outcomes in similar contexts worldwide. Future research should explore cross-country comparisons in greater detail, identifying shared challenges and opportunities for global policy alignment.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This study addresses a critical aspect of infant and young child feeding, focusing on hygiene practices during complementary feeding, which are crucial for child growth and development.

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines, ensuring a comprehensive and reliable synthesis of the available literature.

The rigorous inclusion criteria and quality assessments ensured that only relevant studies were included, which strengthens the validity of the findings.

Limitations

The study excluded qualitative research, which could have provided deeper insights into the determinants of hygiene practices. Future research could explore these factors using qualitative methods to uncover cultural and behavioral nuances that influence hygiene practices.

Restricting the review to articles published in English may have excluded relevant studies in other languages, potentially limiting the scope of the analysis. This limitation could be addressed by including studies in other languages in future reviews.

The exclusion of papers without full access may have resulted in the omission of relevant studies, potentially affecting the comprehensiveness of the findings. Additionally, the exclusion of grey literature based on eligibility criteria may have led to the omission of valuable studies, further limiting the scope of the review. Although grey literature was included in our search strategy, future reviews could consider broadening eligibility criteria to include a wider range of grey literature, which may capture additional insights typically not published in traditional academic journals.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a low pooled proportion of hygienic practices during complementary feeding in Ethiopia. Key predictors of hygiene practices included maternal attitude and the availability of hand washing facilities near toilets. To address these issues, we recommend implementing training and counseling programs for mothers and caregivers on safe food processing and preparation. Further research should explore the impact of community-based interventions on improving hygiene practices and investigate the role of socio-economic and cultural factors in shaping these practices. Such insights can help inform targeted interventions to enhance food safety for infants.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the authors of the primary studies included in this review.

Authors’ contributions

GAA, EG, EKB, KS, GL, ANY, AYB, AGB, SKB search and extract the articles, EGD, EKB, GAA check the quality of the articles, EG, EKB, GAA, KS, GLA, ANY, AYB, AGB, SKB search and extract the articles, EG, EKB, GAA do the analysis part and write the result, GAA, EG, EKB, KS, GLA, ANY, review the manuscript. GAA and EG revised the manuscript. Finally, all authors gave approval of the version to be published; agreed on the journal to which the article had been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Data availability

All materials and data related are included in the main document of the manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publications

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zeleke AM, Bayeh GM, Azene ZN. Hygienic practice during complementary food preparation and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6–24 months in Debark town, northwest Ethiopia, 2021: an overlooked opportunity in the nutrition and health sectors. PLoS One. 2022;17:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang PC, Li SF, Yang HY, Wang LC, Weng CY, Chen KF, et al. Factors associated with cessation of exclusive breastfeeding at 1 and 2 months postpartum in Taiwan. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassie GA, Gebeyehu NA, Gesese MM, Abebe EC, Mengstie MA, Seid MA, et al. Hygienic practice during complementary feeding and its associated factors among mothers / caregivers of children aged 6 – 24 months in Wolaita Sodo town, Southern Ethiopia. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Ayaz F, Bin Ayaz S, Furrukh M, Matee S, Bhutto B. Cleaning practices and contamination status of infant feeding bottle contents and teats in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. Orig Artic Pakistan J Pathol. 2017;28(1):13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teshome HA, Yallew WW, Mulualem JA, Engdaw GT, Zeleke AM. Complementary food feeding hygiene practice and associated factors among mothers with children aged 6–24 months in Tegedie District, Northwest Ethiopia: community-based cross-sectional study. Hygiene. 2022;2(2):72–84. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havelaar AH, Kirk MD, Torgerson PR, Gibb HJ, Hald T, Lake RJ, et al. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med. 2015;12(12):1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter E, Bryce J, Perin J, Newby H. Harmful practices in the management of childhood diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review Global health. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fufa DD, Abhram A, Teshome A, Teji K, Abera F, Tefera M, et al. Hygienic practice of complementary food preparation and associated factors among mothers with children aged from 6 to 24 months in rural Kebeles of Harari region, Ethiopia. Food Sci Technol (United States). 2020;8(2):34–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi S, Ramji S, Arora NK, Rewal S, Dasgupta R, Deshmukh V, et al. Time-constrained mother and expanding market: emerging model of under-nutrition in India. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):11–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Birhanu MT. Practices of hygiene during complementary food feeding and associated factors among women with children aged 6 − 24 months in Dedo district, Southwest Ethiopia: a cross ‐ sectional study. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Abbott D. Save the children feed the future Ethiopia growth through nutrition activity national food safety landscape and rural households food safety practices in …. 2019.

- 12.Marege A, Regassa B, Seid M, Tadesse D, Siraj M, Manilal A. Bacteriological quality and safety of bottle food and associated factors among bottle-fed babies attending pediatric outpatient clinics of Government Health Institutions in Arba Minch, southern Ethiopia. J Heal Popul Nutr. 2023;42(1):1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porritt K, Gomersall J, Lockwood C. JBI's systematic reviews: study selection and critical appraisal. Am J Nurs. 2014;114(6):47–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJ, Hooft L, Leeflang MM. Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bedada S, Benti T, Tegegne M. Complementary food hygiene practice among mothers or caregivers in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study. J Food Sci Hyg. 2021;1(1):26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmelash AA, Melese BD, Admasu FT, Bayih ET, Yitbarek GY. Hygienic practice during complementary feeding and associated factors among mothers of children aged 6–24 months in Bahir Dar Zuria District, Northwest Ethiopia, 2019. J Environ Public Health. 2020;2020:2075351. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esan DT, Adegbilero-Iwari OE, Hussaini A, Adetunji AJ. Complementary feeding pattern and its determinants among mothers in selected primary health centers in the urban metropolis of Ekiti State, Nigeria. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6252. 10.1038/s41598-022-10308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajjura RB, Veldman FJ, Kassier SM. Effect of nutrition education on knowledge, complementary feeding, and hygiene practices of mothers with moderate acutely malnourished children in Uganda. Food Nutr Bull. 2019;40(2):221–30. 10.1177/0379572119840214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi HS, Ha SY, Cha SH, Kang CG, Kim BM. Design of channel type indirect blank holder for prevention of wrinkling and fracture in hot stamping process. AIP Conf Proc. 2011;1383:895–902. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grace D. Burden of foodborne disease in low-income and middle-income countries and opportunities for scaling food safety interventions. Food Secur. 2023;15(6):1475–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel A, Pusdekar Y, Badhoniya N, Borkar J, Agho KE, Dibley MJ. Determinants of inappropriate complementary feeding practices in young children in India: secondary analysis of National Family Health Survey 2005–2006. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(SUPPL. 1):28–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogutu EA, Ellis A, Rodriguez KC, Caruso BA, Mcclintic EE, Ventura SG, et al. Determinants of food preparation and hygiene practices among caregivers of children under two in Western Kenya: a formative research study. BMC Public Health. 2022:1–18. 10.1186/s12889-022-14259-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kimwele A, Ochola S. Complementary feeding and the nutritional status of children 6–23 months attending Kahawa west public health center, Nairobi. IOSR J Nurs Heal Sci. 2017;06(02):17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown J, Cairncross S, Ensink JH. Water, sanitation, hygiene and enteric infections in children. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(8):629-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Tiwari S, Bharadva K, Yadav B, Malik S, Gangal P, Banapurmath CR, et al. Infant and young child feeding guidelines, 2016. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53(8):703–13. 10.1007/s13312-016-0914-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dewey KG. Complementary feeding. Encycl Hum Nutr. 2005:465–71.

- 28.Laar AS, Govender V. Individual and community perspectives, attitudes, and practices to mother-to-child-transmission and infant feeding among HIV-positive mothers in Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic literature review. Int J MCH AIDS. 2013;2(1):153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acharya J. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviour of mothers of young children related to vitamin A supplements: comparing rural and urban perspectives in Nepal. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2018;5(5):389–99. Available from: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2083744337?accountid=14477%0Ahttps://ual.gtbib.net/sod/poa_login.php?centro=$UALMG&?centro=$UALMG&sid=$UALMG&title=&atitle=&aulast=Acharya%2C+Jib&date=2018&volume=&issue=&pages=. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All materials and data related are included in the main document of the manuscript.