Abstract

CXCL14 is a highly conserved chemokine expressed in various cell types, playing crucial roles in both physiological and pathological processes, including immune regulation and tumorigenesis. Recently, the role of CXCL14 in tumors has attracted considerable attention. However, previous pan-cancer studies have reported inconsistencies regarding the effects of CXCL14 on tumors, particularly concerning its expression levels in tumor tissues and its influence on various phenotypes of cancer cells. This variability is believed to stem from the context-dependent nature of CXCL14, as different sources of CXCL14 and its secretion within distinct tumor microenvironments may mediate diverse biological effects. Such phenomena have also been observed in prostate cancer research. Despite a foundational understanding of CXCL14 in prostate cancer, there remains a lack of comprehensive reviews summarizing the specific roles of this chemokine and systematically analyzing the reasons behind its complex effects. Therefore, this article aims to discuss the role of CXCL14 in the tumor microenvironment of prostate cancer and explore future research directions and potential applications.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Chemokines, CXCL14, Tumor microenvironment

Background

Chemokines are a class of small molecular weight secreted proteins that bind to specific receptors on the surface of target cells, exerting chemotactic effects during both physiological and pathological processes. They induce cell migration to specific locations and regulate inflammatory responses, as well as maintain the homeostasis of the local microenvironment [1]. CXCL14, also known as BRAK (Breast and Kidney-Expressed Chemokine) or BMAC (BM-40-SPARC-Associated), is a highly conserved chemokine consistently expressed in the epithelial cells of the skin. It is primarily responsible for the recruitment and maturation of immune cells, plays an immunosurveillance role, and influences epithelial cell mobility [2]. Structurally, CXCL14 resembles other chemokines in the CXC family, containing four conserved cysteine residues that form disulfide bonds [3]. The first 22 amino acids at the N-terminal end are strongly hydrophobic and function as a signal peptide, which is cleaved prior to secretion, resulting in a mature protein consisting of 77 amino acids [4]. A notable distinction is that CXCL14 encodes a very short amino terminus (Ser-Lys) before the invariant CXC motif [5].

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the second most common tumor among men worldwide [6]. With advancements in science and technology, treatment strategies—including surgical intervention, endocrine therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy—have provided significant benefits to patients with PCa [7–11]. However, how to control tumor progression, recurrence, and the emergence of castration resistance after standard first-line treatment—androgen deprivation therapy—remains a significant challenge for urologists [12]. Therefore, elucidating the autocrine roles of tumor cells and their interactions with other cellular components within the tumor microenvironment (TME) is essential for a more comprehensive understanding of the specific mechanisms underlying critical characteristics of PCa progression, drug resistance, and metastasis [13, 14].

Chemokines are important mediators that influence the characteristics of the TME [15]. In recent years, the role of CXCL14 in tumorigenesis and development has garnered extensive attention from researchers. However, the findings have been somewhat divergent, particularly regarding the expression levels of CXCL14 in tumor tissues and its effects on various phenotypes of tumor cells [16–21]. This phenomenon is also observed in studies of CXCL14 in PCa [22–24]. Therefore, by reviewing all existing literature on the relationship between CXCL14 and PCa, as well as studies on CXCL14 in pan-cancer over the past eight years, this paper aims to discuss the role of CXCL14 in the TME of PCa. Additionally, it seeks to analyze the reasons behind the conflicting results and to explore future research directions and potential applications based on insights gained from pan-cancer research.

CXCL14 in PCa

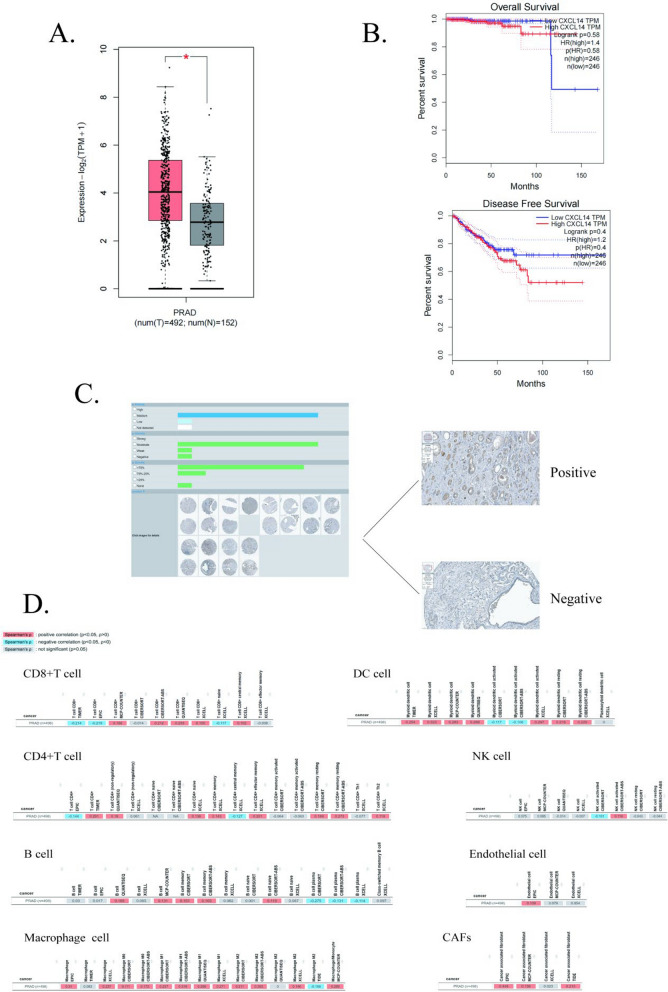

By utilizing online databases, we offer a comprehensive overview of the role of CXCL14 in PCa. According to the results obtained from GEPIA2 [25], CXCL14 exhibited high expression levels in tumor tissues within the TCGA database (Fig. 1A). However, the Overall Survival and Disease-Free Survival rates did not show statistically significant differences between patients with high and low CXCL14 expression levels (Fig. 1B). Based on the HPA database [26], we further verified the extent of CXCL14 expression at the protein level in PCa, observing that it is widely expressed across samples from PCa patients, albeit with notable variability among populations (Fig. 1C). In the TIMER2 database [27], we identified a correlation between CXCL14 expression and several cellular features. Given that CXCL14 is a chemokine, its ability to recruit diverse cell types and remodel their characteristics within the TME is of significant interest to researchers. Previous studies have demonstrated that CXCL14 plays a role in PCa by recruiting macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) [22, 28–31]. Additionally, CXCL14 is closely associated with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and endothelial cells, all of which have been identified as CXCL14-secreting cells in PCa [31–33]. These findings are substantiated by the high correlation results observed in TIMER2. However, some scholars have suggested that CXCL14 may inhibit T-cell proliferation in PCa [31, 34], a conclusion that aligns only partially with results from specific datasets in TIMER2 (Fig. 1D). We hypothesize that this discrepancy may arise from variations in the markers used to define cellular types. Interestingly, pan-cancer studies have also indicated a correlation between CXCL14 and T cells; however, some researchers report a positive correlation [16, 35–37], while others suggest a negative correlation [38] or even propose that CXCL14 acts as a highly selective chemokine that does not modulate T cell chemotaxis [39]. We believe that the interactions between CXCL14 and T cells may depend on the tumor context, and the specific characteristics of their relationship warrants further investigation through molecular biology experiments.

Fig. 1.

CXCL14 Expression as a Prognostic Biomarker and Its Relationship with Immune Infiltration in Prostate Cancer: A Expression of CXCL14 in prostate cancer and normal prostate tissues in the GEPIA 2 database; B The upper panel illustrates the relationship between CXCL14 and Overall Survival (OS) in prostate cancer, the lower panel depicts the relationship between CXCL14 and Disease Free Survival (DFS) in prostate cancer; C Immunohistochemistry of CXCL14 in prostate cancer in the HPA database; D The correlation of CXCL14 with common immune cells in prostate cancer in the TIMER2 database

However, while online databases facilitate ‘code-free’ bioinformatics analyses for researchers, the depth of exploration remains limited. For instance, most samples used in the aforementioned online analyses are derived from TCGA, a bulk RNA sequencing-based database [40], which does not adequately focus on the interactions between different cell types and primarily depicts the relationship between CXCL14 and the TME of PCa from a macroscopic perspective. Therefore, by employing various experimental techniques at the cellular level, we gained a more nuanced understanding of the role of CXCL14 in PCa development. We conducted a comprehensive literature review on CXCL14 and PCa to date, and Table 1 summarizes the key findings from each study. Additionally, Fig. 2 summarizes the molecular interactions between CXCL14 and the TME in PCa, with specific details to be further elaborated upon in the following sections.

Table 1.

Summary of CXCL14-related literature findings

| References | CXCL14 expression in tumour (high grade) | Secretory cells of CXCL14 in clinic | Secretory cells of CXCL14 in experiment | Tumour endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [22] | Upregulated | No distinction | Cancer cell | Tumour promotion |

| [23] | Contradiction | Both cancer cell and stromal cell | Cancer cell | Contradiction |

| [24] | Downregulated | No distinction | Cancer cell | Tumor suppression |

| [70] | Upregulated | No distinction | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [71] | Upregulated | No distinction | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [28] | Downregulated | No distinction | Cancer cell | Tumor suppression |

| [84] | Downregulated | Stromal cell | NA | Tumor suppression |

| [85] | Downregulated | Stromal cell | NA | Tumor suppression |

| [29] | NA | NA | Stromal cell | Tumour promotion |

| [86] | Contradiction | No distinction | NA | Contradiction |

| [32] | NA | NA | Both cancer cell and stromal cell | Tumour promotion |

| [72] | Upregulated | No distinction | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [30] | Upregulated | No distinction | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [34] | Upregulated | No distinction | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [33] | Upregulated | Both cancer cell and stromal cell | Stromal cell | Tumour promotion |

| [31] | Upregulated | Endothelial cells | NA | Tumour promotion |

| [87] | NA | Cancer cell | NA | Tumour promotion |

Fig. 2.

Mechanism diagram of CXCL14 interaction with TME in the prostate cancer: In the TME of prostate cancer, CXCL14 is sourced from tumor cells, CAFs, and endothelial cells. The secretion of CXCL14 by tumor cells is regulated by CD82 and EGF, while the CXCL14 released by CAFs is modulated by exosomes containing lncAY927529. Subsequently, CXCL14 can exert its effects on various cell types, including tumor cells, CAFs (via ERK and ARE/NOS1), macrophages (through ERK and NF-κB), NK cells, T cells, and dendritic cells, ultimately regulating the phenotypic characteristics of the tumor

Oncogenic effects of CXCL14

Most studies on PCa have identified a significant role for CXCL14 in promoting tumorigenesis and progression. The current consensus, based on findings from various cellular experiments, is that CXCL14 enhances the invasion and migration of PCa cells [22, 29, 32, 33]. Additionally, CXCL14 has been shown to recruit macrophages and drive their polarization towards the M2 phenotype [22, 29, 33], which is associated with immune suppression [41]. This process indirectly facilitates the immune escape of tumors [42]. Similar conclusions have been drawn in pan-cancer studies as well [43–45]. However, concerning whether CXCL14 can promote tumor cell proliferation, while all cellular experiments in PCa consistently yielded positive results, research in lung cancer indicated that CXCL14 primarily promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis without affecting proliferation [46]. We propose that such discrepancies may be attributed to the limited energy resources available to tumor cells. During the early stages of metastasis, tumor cells may sacrifice some proliferative capacity in exchange for enhanced invasive potential [47, 48]. Consequently, there could be variability in proliferative capacity at different metastatic stages [49]. The current literature lacks comprehensive studies addressing the effects of CXCL14 on tumor cell proliferation across different metastatic stages in PCa. Additionally, the relationship between CXCL14 and the plasticity of PCa remains an area worthy of future exploration.

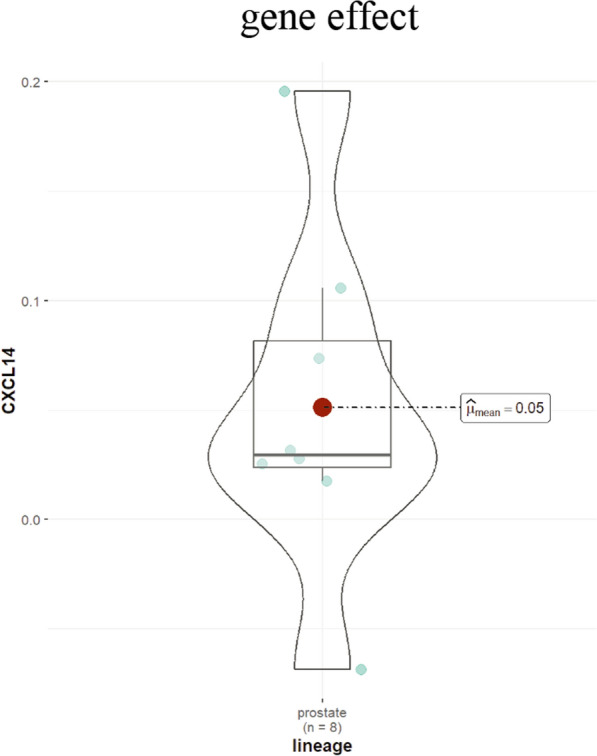

DepMap is built upon the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) project [50], which generates a comprehensive cancer cell dependency map [51, 52] utilizing RNA interference silencing [53] and CRISPR-Cas9 knockout techniques [54]. This methodology facilitates dependency mapping by specifically knocking out individual genes to validate their effects on tumor cell growth. The analysis of PCa cell lines revealed that knocking down CXCL14 inhibited growth in only one out of eight cell lines (gene effect < 0) and yielded a value greater than − 0.5 (Fig. 3), which previous studies have classified as having a non-significant effect [55]. Consequently, based on the results from DepMap, we suggest that the influence of CXCL14 on the proliferation of PCa cells may be minimal. We believe that the discrepancies observed between these findings and cellular experiments could be attributed to cellular heterogeneity, even within the same cell line [56, 57], as well as various confounding factors. These factors include differences in experimental culture conditions [58] and variability in gene knockdown efficiency [59]. Subsequent validation through multi-sample repetitions and the co-validation of various gene editing techniques is required to determine the specific effects of CXCL14 on the growth characteristics of PCa cells.

Fig. 3.

Gene effect score of CXCL14 in prostate cancer cell lines within the DepMap database

Moreover, there is ongoing debate regarding the interaction between CXCL14 and T cells within the TME. In PCa research, it has been suggested that CXCL14 can inhibit T cell proliferation [31, 34] and upregulate the expression of PD-1, an inhibitory immune checkpoint molecule on T cells [22]. This effect indirectly suppresses tumor immunity [60] and promotes the progression of PCa. However, similar phenomena in pan-cancer studies have only been observed in pancreatic and breast cancers [35, 37], while contradictory findings have emerged in studies involving head and neck tumors and esophageal cancers [36, 38]. We propose that the specific effects of CXCL14 on T cells may depend more on the characteristics of the TME. CXCL14 is often associated with mesenchymal stromal cells [61, 62], which are capable of secreting various cytokines, such as TGF-β, thereby suppressing the immune response by acting on T cells [63]. Regarding T cell activation, CXCL14 can recruit DCs, which play a critical role in T cell activation [64]. We believe that the downstream pathways mediated by CXCL14 are diverse, and the specific effects are more dependent on the characteristics of different cancer types and the unique TME of individual patients [65].

Non-coding RNAs are RNA molecules that do not encode proteins, encompassing various types, including microRNAs, circular RNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and others. These RNA species play critical roles in cellular processes [66] and are intricately linked to the onset and progression of tumors [67]. In the context of prostate cancer, research has demonstrated that exosomes secreted by tumors containing lncAY927529 can induce the secretion of CXCL14 from ST2 cells, thereby promoting tumor progression [32]. Furthermore, in ovarian cancer, LINC00092 has been identified as a downstream regulator of CXCL14, driving tumor glycolysis and progression [61]. Recent advancements in third-generation full-length transcriptome sequencing technology have markedly improved the accuracy of long-chain RNA detection [68]. These technological improvements provide a robust foundation for future studies aimed at establishing a comprehensive non-coding RNA library specific to prostate cancer, which will significantly enhance our understanding of the functional roles that non-coding RNAs play in the pathogenesis and progression of this malignancy.

With the continuous advancement of bioinformatics analysis technologies, an increasing number of studies have begun to rely on the mining of public databases [69]. This trend is also reflected in the research on CXCL14 and PCa [30, 34, 70–72], where all aforementioned studies concluded that CXCL14 promotes the progression of PCa or is associated with adverse clinical features and poor prognosis based on bioinformatics analyses. Furthermore, recent pan-cancer studies involving CXCL14 have yielded similar findings [73–76]. While public data mining can effectively annotate sequencing results from various dimensions and offers convenience [77], we cannot completely rely on bioinformatics analyses. As illustrated in Fig. 1B, the survival outcomes analyzed from PCa data in TCGA database appear negative. The primary reason for this is that TCGA fundamentally serves as a database of RNA expression [78], whereas it is proteins that truly influence functional and phenotypic levels [79]. Although there is a positive correlation between RNA expression levels and protein abundance to some extent [80], post-transcriptional modifications mean that RNA expression does not fully substitute for protein expression [81]. Therefore, network analysis tools based on TCGA data are primarily of reference value. Additionally, bioinformatics analyses has several limitations, including small sample sizes in sequencing results that may lead to population heterogeneity and lack statistical significance [82], as well as noise generated during the sequencing process [83]. Consequently, more downstream functional experiments and real clinical data are necessary to validate these findings.

Antitumor effects of CXCL14

Despite substantial evidence supporting the tumor-promoting role of CXCL14 in PCa, some scholars have reached opposing or contradictory conclusions [23, 24, 28, 84–86]. Although the number of studies favoring the tumor-promoting perspective is greater (11 vs. 6), it is noteworthy that all six contrary studies relied on clinical cohorts or basic experiments rather than public database analyses. This discrepancy not only affirms the authenticity and consistency of the results from bioinformatics analysis [88] but also underscores the credibility of these findings. Similarly, several studies in pan-cancer research support this viewpoint [89–92]. Regarding the mechanisms by which CXCL14 suppresses tumor development, PCa studies suggest that DCs are recruited to indirectly activate immune responses within the TME [28]. In contrast, pan-cancer studies emphasize the recruitment and activation of functional T cells as a pivotal mechanism [16, 35–37]. However, investigations into the specific downstream mechanistic pathways underlying CXCL14’s tumor-suppressive effects remain relatively scarce in both PCa and pan-cancer studies. In contrast, there is a stronger focus on upstream research, particularly concerning the mechanisms by which CXCL14 expression is suppressed in tumors [93]. Notably, CXCL14 promoter methylation has been demonstrated to lead to downregulation of expression in both prostate and pan-cancer studies [16, 28, 94–96]. Given that various DNA methyltransferase inhibitors are employed in clinical treatments for PCa [97], exploring their application in TME characterized by low CXCL14 expression warrants further animal experiments and clinical studies.

Potential mechanisms underlying the paradoxical role of CXCL14

Some scholars have attempted to elucidate the reasons behind the dual effects of CXCL14 in tumors, even within the same cancer type, by employing concepts such as 'cancer type specificity' and 'secretory cell specificity [2, 4, 5, 98].

Regarding the specificity of cancer species, numerous studies have indicated that the same molecule can mediate diametrically opposed functional pathways in different cancer types [99, 100]. First, the cellular localization of the molecule's role may vary across cancer types, leading to the mediation of distinct signaling pathways in both intracellular and extracellular contexts [101]. The premise that CXCL14, as a secreted protein, must be released outside the cell to exert its function is also worthy of consideration. Second, while receptors and downstream cascade signaling molecules are critical components of signaling pathways, unfortunately, the specific interactions between CXCL14 and its receptors, as well as the primary pathways through which it operates, remain inadequately addressed. In the subsequent sections, we will further elucidate the findings regarding CXCL14 receptors, positing that the expression levels of these receptors in the TME differ among various cancer types [102], thereby influencing the functional pathways mediated by CXCL14 to some extent. Concerning downstream signaling molecules, Fig. 2 illustrates the specific signaling pathways through which CXCL14 has exerted its biological effects within PCa TME to date. Tumor-promoting pathways include those mediated through macrophage interactions, such as CXCL14/ERK and CXCL14/NF-κB, and those involving CAFs, including CXCL14/ERK and CXCL14/ARE/NOS1. Conversely, evidence supporting a tumor-suppressive pathway is limited; preliminary experiments suggest that epidermal growth factor (EGF) can inhibit CXCL14 expression in tumor cells, promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, yet comprehensive descriptions of CXCL14's downstream effects are lacking. However, while previous studies have identified several signaling pathways within the TME that require CXCL14 involvement and can influence tumor phenotypic characteristics, it is important to note that tumors inherently possess significant heterogeneity. Relying solely on standardized cell lines for experimentation fails to replicate the genetic alterations that occur in vivo under the influence of individual patient characteristics. Future researchers should consider collecting primary tumor cells from patients with diverse characteristics to explore the specific functions of CXCL14 across different tumor landscapes. Thus, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how CXCL14 influences the functions of various cell types within the TME in PCa. Additionally, CXCL14 is essentially a chemokine, with its primary role being to induce directional cell movement [103]. It is conceivable that CXCL14 recruits different cell types and indirectly influences tumor development in various cancer contexts, most notably through the recruitment of activated immune cells [104, 105] or suppressed immune cells [22, 106] to remodel the TME. Notably, Schwann cells play a crucial role in perineural invasion [107]; they migrate into tumor cells at an early stage, ‘leading’ them along nerves—a phenomenon in which chemokines are believed to play a significant role [108, 109]. Given the frequent occurrence of perineural invasion in PCa patients [110], investigating whether CXCL14 contributes to PCa by recruiting non-immune cells presents a promising area for future research.

Regarding the specificity of secreting cells, we have observed that within the TME, various cell types, in addition to tumor cells and CAFs, are equally capable of secreting CXCL14. We will explore this phenomenon in greater detail in the subsequent sections. Furthermore, we aim to hypothesize more profoundly about why CXCL14 secreted by different cell types mediates opposite biological effects. Firstly, there may be isoforms of CXCL14 that have yet to be identified. Although no studies have investigated this possibility to date, previous literature has demonstrated that alternative splicing can generate protein isoforms with distinct functions [111]. Additionally, in a non-tumor context, some researchers have found that single nucleotide polymorphisms in CXCL14 can lead to varying degrees of immune responses in patients infected with influenza A [112]. Currently, there is a paucity of studies investigating the functional polymorphisms of CXCL14 in prostate cancer, highlighting this as a significant area for future research endeavors. Secondly, the molecule that ultimately determines the biological effect might not be CXCL14 itself; rather, the high expression levels found in mesenchymal tissues and tumor cells in earlier studies could represent two distinct TME. For instance, a study on breast cancer indicated that CXCL14 initially acts on CAFs, promoting the release of several important cytokines into the TME, such as FGF-2, MMP8, TIMP-1, CXCL1, and CX3CL1, thereby indirectly facilitating tumor cell proliferation and metastasis [39]. As a secreted protein, it is reasonable to assume that CXCL14 released by CAFs may preferentially act upon CAFs themselves or exert a significantly stronger effect on them than on tumor cells, thereby fostering the development of a unique tumor-promoting microenvironment. In contrast, CXCL14 secreted by tumor cells may also preferentially affect tumor cells and activate alternative pathways to create a tumor-suppressive microenvironment, although this remains to be validated by further studies.

Overall, after collating recent studies on the relationship between CXCL14 and pan-cancer, we did not observe a clear preference for tumor-promoting or tumor-suppressing cancer types. Similar to findings in PCa, most reports indicate that both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing effects can occur within the same cancer type [89, 113]. We believe that the processes determining the specific function of a molecule are complex and cannot be simply summarized by a direct mapping relationship. Although we have proposed several hypotheses regarding the opposing effects induced by CXCL14 in the preceding sections, our intention is merely to highlight potential research directions rather than assert that CXCL14 must induce certain phenomena through specific mechanisms. Tumor biology is influenced by the TME, which comprises a multidimensional network of interactions [114]. Furthermore, the characteristics of a given cancer or even the same pathological subtype are not invariant [115]. A potentially crucial step moving forward may involve ‘screening’—specifically, how to identify CXCL14-dominant TME and the molecules that interact with CXCL14.

Cellular sources of CXCL14

In PCa studies, the results shown in Table 1 indicate that the majority of CXCL14-secreting cells are predominantly tumor cells and CAFs. Notably, a report on tumor bone metastasis found that endothelial-to-osteoblast hybrid cells can secrete high levels of CXCL14, which promotes M2 macrophage polarization and inhibits T cell proliferation, ultimately resulting in an immunosuppressive TME [31]. With respect to CAFs, numerous basic experiments demonstrate that CXCL14 secreted by these cells fosters PCa development, and similar conclusions have emerged from recent pan-cancer studies [39, 44–46, 61]. However, clinical results have been inconsistent across both PCa and pan-cancer research [116, 117]. We believe this inconsistency may be influenced by sample size limitations; due to significant patient heterogeneity, small sample sizes often fail to accurately reflect the actual situation in clinical practice [118, 119]. Additionally, most studies are retrospective, which may introduce potential selection bias [120]. Concerning tumor cells, the findings in PCa are more complex, with reports of both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressing effects observed in both basic experiments and clinical practice, similar results have been noted in pan-cancer studies [96, 121, 122]. We hypothesize that the high variability in results may stem from substantial differences among various cell lines or even within the same cell line in identical cancers [123], with such variability being particularly pronounced in patient populations.

In addition to tumor cells, CAFs, and endothelial-to-osteoblast hybrid cells, studies in pan-cancer research have also identified other types of cells that can secrete significant amounts of CXCL14, influencing tumor biological activities. For example, a study on B-cell lymphoma found that macrophages can also secrete CXCL14, which inhibits M1 polarization (an immune-activated type [124]) by lowering aerobic glycolysis levels [125]. Similarly, in a nasopharyngeal carcinoma study, perivascular cells were found to be regulated by the FGF2/FGFR1/ERK/AHR pathway, secreting large amounts of CXCL14 to promote M2 macrophage polarization, ultimately leading to tumor immune escape and promoting tumor progression [106]. With advancements in sequencing technologies, single-cell transcriptomic analysis has been widely applied across various diseases [126]. This provides us with new analytical approaches to investigate whether there are other sources of CXCL14 secretion in PCa. By conducting in-depth analyses at the single-cell level within large, cross-regional clinical cohorts, we aim to explore the predominant cellular sources that play key roles under different TME characteristics, ultimately assisting clinicians in developing a more comprehensive CXCL14 secretion profile.

Potential receptors of CXCL14

So far, there is no widely accepted answer regarding the specific receptors for CXCL14. Unlike other chemokines, CXCL14 does not have a “dedicated” CXCR molecule [127]. In previous studies focusing on PCa, researchers have been more concerned with identifying the upstream and downstream signaling pathways when CXCL14 exerts its biological functions, while research on CXCL14 receptors has been relatively scarce. Only one study has predicted potential receptors based on a protein interaction network database (STRING), suggesting that CXCR4, CXCL12, CXCR3, CXCR2, CCR2, CCR1, CXCR5, CCR7, CXCR1, and CCR5 may have close interactions with CXCL14 and could be potential receptors [34]. However, this conclusion does not hold in pan-cancer studies. In one breast cancer study, the authors utilized sequence alignment methods to identify GPCRs that exhibit similarities to known chemokine receptors (CXCL14, like other chemokines, signals through the Gαi subfamily of GPCRs). By combining these findings with reactive cell lines of CXCL14, they hypothesized that potential receptors include ACKR2, CXCR4, GPR25, or GPR182. Experimental validation showed that only ACKR2 could induce the downstream pathways of CXCL14, but ACKR2 is not a direct receptor for CXCL14 [39]. It is true that receptor expression for CXCL14 may vary among different cancer types; however, this study also provides us with new directions for further research.

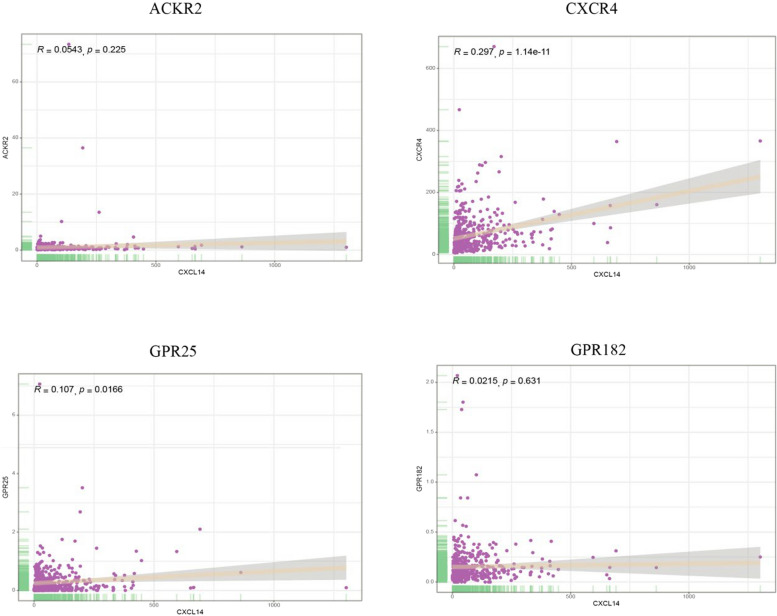

We analyzed the TCGA database to extract samples from all PCa patients and performed a correlation analysis between CXCL14 and all genes. Figure 4 demonstrates the correlation levels of CXCL14 with ACKR2, CXCR4, GPR25, and GPR182 in PCa. Unfortunately, the correlations between these four molecules and CXCL14 were not satisfactory. However, the interactions between molecules are not limited to expression levels; various non-expression-related pathways, including stability and the promotion of nuclear translocation, should also be further validated in future studies [128, 129].

Fig. 4.

The correlation of CXCL14 with ACKR2, CXCR4, GPR25, and GPR182 in prostate cancer samples from TCGA

Future directions in CXCL14 research

We conducted a search in ClinicalTrials and found no ongoing targeted therapy projects involving CXCL14 in PCa. Consequently, it is imperative to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of CXCL14 in the initiation and progression of PCa to establish a foundation for clinical translation. Drawing from previous experiences and integrating the latest technological advancements, we propose several key directions for future basic research: 1 Researchers should adopt a comprehensive approach when selecting cellular models for their experiments. It is crucial to consider not only tumor cells but also other CXCL14-secreting cell types, such as CAFs and endothelial cells. Additionally, co-culturing tumor cells with CAFs is essential for accurately simulating the in vivo TME; this methodology has already shown promise in numerous foundational studies [130, 131]. Incorporating improvements such as organoid culture systems and primary cell cultures represents vital strategies for replicating the in vivo growth and developmental environment of tumors [132]. 2 Given that many researchers focus on various types of secreting cells, distinguishing cell types becomes increasingly important. Previous studies have predominantly leveraged TCGA data, which, while providing large sample sizes that enhance result reliability, also have inherent limitations associated with bulk RNA sequencing. This method does not allow for the differentiation of the various components within the TME, potentially leading to only a general impression of certain phenomena. More nuanced results must be validated through single-cell technologies, including single-cell transcriptomics [133], single-cell proteomics [134], and single-cell metabolomics [135]. Furthermore, utilizing spatial information[136]could facilitate the exploration of interaction preferences among CXCL14-secreting cells and their surrounding counterparts, as well as help delineate distinct subregions based on CXCL14 expression levels—laying the groundwork for future precision therapies. 3 We should explore the interactions between CXCL14 and prevalent TME types in PCa, including immune desert tumors [137] (cold tumors) and inflammatory tumors [138] (hot tumors). As previously noted, the molecular relationships within the TME are complex; under varying subtype contexts, CXCL14 may interact with different molecules, resulting in diverse phenotypic characteristics. Given the conflicting findings reported in earlier studies, a more holistic perspective is warranted to interpret the role of CXCL14: identifying the core molecules that collaborate to form the TME and elucidating the key pathways involved, rather than solely focusing on whether CXCL14 acts as a promoter or inhibitor of tumorigenesis.

In clinical diagnostics, CXCL14, as a protein that can be secreted into the extracellular space, is theoretically detectable in peripheral blood. Although there are currently no relevant applications in PCa, studies across various cancers have reported that measuring CXCL14 levels in blood and urine can assist in tumor diagnosis and prognostic prediction [139]. For instance, in one study on rectal cancer, the authors established two novel indices, CXCL14/CEA and CXCL14/CRP, which improved the prediction of tumor occurrence [140]. In PCa, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is widely used for differentiating PCa from benign prostatic hyperplasia [141]; however, PSA values in the range of 4–10 ng/ml are considered to be in a “gray zone”, making it challenging to draw conclusions based solely on laboratory tests [142]. Therefore, exploring whether the combination of CXCL14 with PSA-related indicators (such as PSA, p2PSA [143]) can enhance the diagnostic efficiency of PCa and reduce unnecessary biopsy procedures is a promising avenue for investigation. Moreover, the application of PSA in PCa has its limitations. PSA is primarily used for diagnosing PCa rather than predicting prognosis-related events such as bone metastasis, postoperative biochemical recurrence, and castration resistance following androgen deprivation therapy [144, 145]. While many studies have found associations between PSA levels and these prognostic factors [146–149], no universally accepted threshold has yet been established. As CXCL14 is a molecule associated with metastasis, research has demonstrated potential in using machine learning models that incorporate multiple chemokines, including CXCL14, to predict the efficacy of bicalutamide [30]. Thus, the prospect of combining CXCL14 with PSA to predict these related events is highly anticipated.

In addition to the previously mentioned changes in blood and urine, alterations in the components of prostatic fluid also play a significant role in the diagnosis of PCa, including Zn2⁺, citrate, and lactate dehydrogenase [150–152]. However, it is regrettable that there have been no studies to date investigating the differential expression of CXCL14 in prostatic fluid.

Conclusions

In summary, research on CXCL14 in PCa has yet to reach a consensus. The prevailing trend suggests that CXCL14 secreted by tumor cells tends to inhibit tumorigenesis and progression, while that secreted by CAFs appears to promote tumor development. However, some studies have reported contradictory conclusions. Therefore, despite numerous researchers focusing on chemokines and CXCL14 in the context of PCa, significant gaps in knowledge remain to be addressed. It is hoped that future rigorous basic experiments, combined with multicenter, multimodal, and large-sample clinical cohorts, will elucidate the specific role of CXCL14 within different TMEs, providing new insights for the precise diagnosis and treatment of PCa.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics mining methods

The RNA expression of CXCL14 and survival analysis in prostate cancer were conducted using the GEPIA 2 database (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn), which provides data based on TCGA and GTEx resources [25]. Immunohistochemical analysis of CXCL14 in prostate cancer was obtained from the HPA database (http://www.proteinatlas.org) [26]. Correlation analysis of CXCL14 with various cell types in the TME was performed using TIMER2 database (http://timer.cistrome.org) [27]. Additionally, the “DepMap_Public_22Q2” version was downloaded from DepMap (https://depmap.org/portal/) [51] to analyze the relationship between CXCL14 and prostate cancer cell proliferation. Data from TCGA were retrieved using the R package “TCGAbiolinks” [153] in R version 4.2.2, and subsequent correlation analyses were performed between all genes and CXCL14 after selecting only prostate cancer patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- PCa

Prostate cancer

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- DCs

Dendritic cells

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- PSA

Prostate-specific antigen

Author contributions

Lei Tang and Xin Chen contributed equally to this work. Conceptualization, L.T.; data curation, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, X.W. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (No.BE2020655).

Availability of data and materials

The original data of the present study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Lei Tang and Xin Chen have Contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Jianquan Hou, Email: houjianquan@suda.edu.cn.

Xuedong Wei, Email: wxd0422@163.com.

References

- 1.Mempel TR, Lill JK, Altenburger LM. How chemokines organize the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024;24(1):28–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gowhari Shabgah A, et al. Chemokine CXCL14; a double-edged sword in cancer development. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;97: 107681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai C, et al. CXCL14 displays antimicrobial activity against respiratory tract bacteria and contributes to clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae pulmonary infection. J Immunol. 2015;194(12):5980–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hara T, Tanegashima K. Pleiotropic functions of the CXC-type chemokine CXCL14 in mammals. J Biochem. 2012;151(5):469–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westrich JA, et al. The multifarious roles of the chemokine CXCL14 in cancer progression and immune responses. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(7):794–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liadi Y, et al. Prostate cancer metastasis and health disparities: a systematic review. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024;27(2):183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fang AM, et al. Surgical management and considerations for patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer. Curr Treat Option Oncol. 2024;25(1):66–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, et al. PROTACs targeting androgen receptor signaling: potential therapeutic agents for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2024;205: 107234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patke R, et al. Epitranscriptomic mechanisms of androgen signalling and prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 2024;56: 101032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miszczyk M, et al. The efficacy and safety of metastasis-directed therapy in patients with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Urol. 2024;85(2):125–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serritella AV, Hussain M. Metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer in the era of doublet and triplet therapy. Curr Treat Option Oncol. 2024;25(3):293–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haffner MC, et al. Genomic and phenotypic heterogeneity in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2021;18(2):79–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark KC, et al. Novel therapeutic targets and biomarkers associated with prostate cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs). Crit Rev Oncog. 2022;27(1):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang X, et al. Autocrine/paracrine growth hormone in cancer progression. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2024. 10.1530/ERC-23-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen D, et al. Metabolic regulatory crosstalk between tumor microenvironment and tumor-associated macrophages. Theranostics. 2021;11(3):1016–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicchini L, et al. Suppression of antitumor immune responses by human papillomavirus through epigenetic downregulation of CXCL14. mBio. 2016. 10.1128/mBio.00270-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doebar SC, et al. Gene expression differences between ductal carcinoma in situ with and without progression to invasive breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2017;187(7):1648–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilyas U, et al. Genome wide meta-analysis of cDNA datasets reveals new target gene signatures of colorectal cancer based on systems biology approach. J Biol Res (Thessalon). 2020;27:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AbdelMageed M, et al. The chemokine CXCL16 is a new biomarker for lymph node analysis of colon cancer outcome. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. 10.3390/ijms2022579310.3390/ijms20225793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao LN, et al. CXCL14 facilitates the growth and metastasis of ovarian carcinoma cells via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Ovarian Res. 2021;14(1):159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li H, et al. Exploration of the shared genes and signaling pathways between lung adenocarcinoma and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(6):3054–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tian HY, et al. Exosomal CXCL14 contributes to M2 macrophage polarization through NF-κB signaling in prostate cancer. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:7616696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarze SR, et al. Modulation of CXCL14 (BRAK) expression in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2005;64(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang C, et al. The roles of Y-box-binding protein (YB)-1 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 14 (CXCL14) in the progression of prostate cancer via extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling. Bioengineered. 2021;12(2):9128–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang Z, et al. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucl Acid Res. 2019;47(W1):W556-w560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uhlén M, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li T, et al. TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Nucl Acid Res. 2020;48(W1):W509-w514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song EY, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms of promigratory chemokine CXCL14 regulation in human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4394–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Augsten M, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts expressing CXCL14 rely upon NOS1-derived nitric oxide signaling for their tumor-supporting properties. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2999–3010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen L, et al. The established chemokine-related prognostic gene signature in prostate cancer: implications for anti-androgen and immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1009634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu G, et al. Prostate cancer-induced endothelial-to-osteoblast transition generates an immunosuppressive bone tumor microenvironment. bioRxiv. 2023;41:317. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Q, et al. Exosomal lncAY927529 enhances prostate cancer cell proliferation and invasion through regulating bone microenvironment. Cell Cycle. 2021;20(23):2531–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Augsten M, et al. CXCL14 is an autocrine growth factor for fibroblasts and acts as a multi-modal stimulator of prostate tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(9):3414–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng D, et al. Mitochondria dysfunction-mediated molecular subtypes and gene prognostic index for prostate cancer patients undergoing radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 858479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu K, et al. Integrative analyses of scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq reveal CXCL14 as a key regulator of lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2021;30(5):370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westrich JA, et al. CXCL14 suppresses human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer through antigen-specific CD8(+) T-cell responses by upregulating MHC-I expression. Oncogene. 2019;38(46):7166–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J, et al. Prognostic biomarkers and immunotherapeutic targets among CXC chemokines in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 711402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egeland C, et al. Calcium electroporation of esophageal cancer induces gene expression changes: a sub-study of a phase I clinical trial. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(17):16031–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sjöberg E, et al. A Novel ACKR2-dependent role of fibroblast-derived CXCL14 in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis of breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(12):3702–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomczak K, Czerwińska P, Wiznerowicz M. The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): an immeasurable source of knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 2015;19(1a):A68-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo M, et al. Macrophage polarization: an important role in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1352946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papadakos SP, et al. Unveiling the Yin-Yang balance of M1 and M2 macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma: role of exosomes in tumor microenvironment and immune modulation. Cells. 2023. 10.3390/cells12162036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu D, et al. Downregulated microRNA-150 upregulates IRX1 to depress proliferation, migration, and invasion, but boost apoptosis of gastric cancer cells. IUBMB Life. 2020;72(3):476–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fazi B, et al. The expression of the chemokine CXCL14 correlates with several aggressive aspects of glioblastoma and promotes key properties of glioblastoma cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. 10.3390/ijms20102496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y, et al. Down-regulation of miR-29b in carcinoma associated fibroblasts promotes cell growth and metastasis of breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(24):39559–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang TM, et al. CXCL14 promotes metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer through ACKR2-depended signaling pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(5):1455–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brabletz S, et al. Dynamic EMT: a multi-tool for tumor progression. Embo j. 2021;40(18): e108647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bakir B, et al. EMT, MET, plasticity, and tumor metastasis. Trend Cell Biol. 2020;30(10):764–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen Q, Xu P, Mei C. Role of micronucleus-activated cGAS-STING signaling in antitumor immunity. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2024;53(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghandi M, et al. Next-generation characterization of the cancer cell line Encyclopedia. Nature. 2019;569(7757):503–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsherniak A, et al. Defining a cancer dependency map. Cell. 2017;170(3):564-576.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyers RM, et al. Computational correction of copy number effect improves specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat Genet. 2017;49(12):1779–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sioud M. RNA interference: story and mechanisms. Method Mol Biol. 2021;2282:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang SW, et al. Current applications and future perspective of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uchida S, Sugino T. In silico identification of genes associated with breast cancer progression and prognosis and novel therapeutic targets. Biomedicines. 2022. 10.3390/biomedicines10112995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arzumanian VA, Kiseleva OI, Poverennaya EV. The curious case of the HepG2 cell line: 40 years of expertise. Int J Mol Sci. 2021. 10.3390/ijms222313135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rahimi AM, Cai M, Hoyer-Fender S. Heterogeneity of the NIH3T3 fibroblast cell line. Cells. 2022. 10.3390/cells11172677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nguyen TM, et al. Reducing phenotypic instabilities of a microbial population during continuous cultivation based on cell switching dynamics. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2021;118(10):3847–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mazurkiewicz E, Mrówczyńska E, Mazur AJ. Isolation of stably transfected melanoma cell clones. J Vis Exp. 2022. 10.3791/63371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharpe AH, Pauken KE. The diverse functions of the PD1 inhibitory pathway. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(3):153–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao L, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00092 acts in cancer-associated fibroblasts to drive glycolysis and progression of ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2017;77(6):1369–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ji X, et al. CXCL14 and NOS1 expression in specimens from patients with stage I-IIIA nonsmall cell lung cancer after curative resection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(10): e0101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fang Z, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of proliferative phase endometrium: systems analysis of cell-cell communication network using cell chat. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10: 919731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heras-Murillo I, et al. Dendritic cells as orchestrators of anticancer immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21(4):257–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quail DF, Joyce JA. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19(11):1423–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Panni S, et al. Non-coding RNA regulatory networks. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2020;1863(6): 194417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goodall GJ, Wickramasinghe VO. RNA in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021;21(1):22–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sanita Lima M, et al. Long-read RNA sequencing can probe organelle genome pervasive transcription. Brief Funct Genom. 2024;23(6):695–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qin F, et al. Evaluation of the TRPM protein family as potential biomarkers for various types of human cancer using public database analyses. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(2):770–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feng DC, et al. Identification of senescence-related molecular subtypes and key genes for prostate cancer. Asian J Androl. 2023;25(2):223–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams KA, et al. A systems genetics approach identifies CXCL14, ITGAX, and LPCAT2 as novel aggressive prostate cancer susceptibility genes. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(11): e1004809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gerashchenko GV, et al. Expression pattern of genes associated with tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer. Exp Oncol. 2018;40(4):315–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fang D, et al. Identification of immune-related biomarkers for predicting neoadjuvant chemotherapy sensitivity in HER2 negative breast cancer via bioinformatics analysis. Gland Surg. 2022;11(6):1026–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.García-Solano J, et al. Differences in gene expression profiling and biomarkers between histological colorectal carcinoma subsets from the serrated pathway. Histopathology. 2019;75(4):496–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.López-Ozuna VM, et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for lymph node involvement in obese women with endometrial cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11: 695404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cai GX, et al. A plasma-derived extracellular vesicle mRNA classifier for the detection of breast cancer. Gland Surg. 2021;10(6):2002–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li P, et al. dbGSRV: a manually curated database of genetic susceptibility to respiratory virus. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3): e0262373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zoabi Y, Shomron N. Processing and analysis of RNA-seq data from public resources. Method Mol Biol. 2021;2243:81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nussinov R, Tsai CJ, Jang H. Protein ensembles link genotype to phenotype. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15(6): e1006648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Buccitelli C, Selbach M. mRNAs, proteins and the emerging principles of gene expression control. Nat Rev Genet. 2020;21(10):630–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Frye M, et al. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science. 2018;361(6409):1346–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li CI, et al. Power and sample size calculations for high-throughput sequencing-based experiments. Brief Bioinform. 2018;19(6):1247–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Khozyainova AA, et al. Complex analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2023;88(2):231–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eiro N, et al. Gene expression profile of stromal factors in cancer-associated fibroblasts from prostate cancer. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022. 10.3390/diagnostics12071605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eiro N, et al. Stromal factors involved in human prostate cancer development, progression and castration resistance. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143(2):351–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rastmanesh R, et al. Type 2 diabetes: a protective factor for prostate cancer? An overview of proposed mechanisms. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2014;12(3):143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dodla P, et al. Gene expression analysis of human prostate cell lines with and without tumor metastasis suppressor CD82. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Friedman J, Alm EJ. Inferring correlation networks from genomic survey data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8(9): e1002687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu J, et al. Identification of liver metastasis-associated genes in human colon carcinoma by mRNA profiling. Chin J Cancer Res. 2018;30(6):633–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li J, et al. Tumor characterization in breast cancer identifies immune-relevant gene signatures associated with prognosis. Front Genet. 2019;10:1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Luo X, et al. Associations of C-X-C motif chemokine ligands 1/2/8/13/14 with clinicopathological features and survival profile in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2022;24(4):348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ignacio RMC, et al. Chemokine network and overall survival in TP53 wild-type and mutant ovarian cancer. Immune Netw. 2018;18(4): e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cao JW, Cui WF, Zhu HJ. The negative feedback loop FAM129A/CXCL14 aggravates the progression of esophageal cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(12):4220–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kondo T, et al. Expression of the chemokine CXCL14 and cetuximab-dependent tumour suppression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogenesis. 2016;5(7): e240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nakayama R, Arikawa K, Bhawal UK. The epigenetic regulation of CXCL14 plays a role in the pathobiology of oral cancers. J Cancer. 2017;8(15):3014–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang TX, et al. Identification of aberrantly methylated differentially expressed genes targeted by differentially expressed miRNA in osteosarcoma. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(6):373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marques-Magalhães Â, et al. Targeting DNA methyltranferases in urological tumors. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Korbecki J, et al. The effect of hypoxia on the expression of CXC chemokines and CXC chemokine receptors-a review of literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2021. 10.3390/ijms22020843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pai SG, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10(1):101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Russell JO, Monga SP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in liver development, homeostasis, and pathobiology. Annu Rev Pathol. 2018;13:351–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Moreno-García A, et al. The neuromelanin paradox and its dual role in oxidative stress and neurodegeneration. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021. 10.3390/antiox10010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mantovani A, et al. Macrophages as tools and targets in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(11):799–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ozga AJ, Chow MT, Luster AD. Chemokines and the immune response to cancer. Immunity. 2021;54(5):859–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen X, et al. The role of CXCL chemokine family in the development and progression of gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2020;13(3):484–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li W, et al. Screening of CXC chemokines in the microenvironment of ovarian cancer and the biological function of CXCL10. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(1):329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang Y, et al. FGF-2 signaling in nasopharyngeal carcinoma modulates pericyte-macrophage crosstalk and metastasis. JCI Insight. 2022. 10.1172/jci.insight.157874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Li J, Kang R, Tang D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of perineural invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2021;41(8):642–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen Z, Fang Y, Jiang W. Important cells and factors from tumor microenvironment participated in perineural invasion. Cancers (Basel). 2023. 10.3390/cancers15051360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.March B, et al. Tumour innervation and neurosignalling in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2020;17(2):119–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Niu Y, Förster S, Muders M. The role of perineural invasion in prostate cancer and its prognostic significance. Cancers (Basel). 2022. 10.3390/cancers14174065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Cieply B, Carstens RP. Functional roles of alternative splicing factors in human disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6(3):311–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen L, Lei Y, Zhang L. Role of C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 14 promoter region DNA methylation and single nucleotide polymorphism in influenza a severity. Respir Med. 2021;185: 106462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Zeng J, et al. Aberrant ROS mediate cell cycle and motility in colorectal cancer cells through an oncogenic CXCL14 signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12: 764015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kang J, et al. Tumor microenvironment mechanisms and bone metastatic disease progression of prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2022;530:156–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Roma-Rodrigues C, et al. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. 10.3390/ijms20040840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tian PF, et al. Plasma CXCL14 as a candidate biomarker for the diagnosis of lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 833866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sjöberg E, et al. Expression of the chemokine CXCL14 in the tumour stroma is an independent marker of survival in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(10):1117–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bian X, et al. Integration analysis of single-cell multi-omics reveals prostate cancer heterogeneity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(18): e2305724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Noordzij M, et al. Sample size calculations. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;118(4):c319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Talari K, Goyal M. Retrospective studies—utility and caveats. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2020;50(4):398–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Li X, Zhao L, Meng T. Upregulated CXCL14 is associated with poor survival outcomes and promotes ovarian cancer cells proliferation. Cell Biochem Funct. 2020;38(5):613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Küçükköse C, Yalçin ÖÖ. Effects of Notch signalling on the expression of SEMA3C, HMGA2, CXCL14, CXCR7, and CCL20 in breast cancer. Turk J Biol. 2019;43(1):70–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhu Q, et al. Single cell multi-omics reveal intra-cell-line heterogeneity across human cancer cell lines. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):8170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang H, et al. The promising role of tumor-associated macrophages in the treatment of cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;73: 101041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wu M, et al. 1,5-AG suppresses pro-inflammatory polarization of macrophages and promotes the survival of B-ALL in vitro by upregulating CXCL14. Mol Immunol. 2023;158:91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jovic D, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: a brief overview. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(3): e694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wu T, et al. The role of CXC chemokines in cancer progression. Cancers (Basel). 2022. 10.3390/cancers15010167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Shaath H, et al. Long non-coding RNA and RNA-binding protein interactions in cancer: Experimental and machine learning approaches. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 3):325–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Mesjasz A, et al. Potential role of IL-37 in atopic dermatitis. Cells. 2023. 10.3390/cells12232766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schuth S, et al. Patient-specific modeling of stroma-mediated chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer using a three-dimensional organoid-fibroblast co-culture system. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Strating E, et al. Co-cultures of colon cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts recapitulate the aggressive features of mesenchymal-like colon cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1053920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yan HHN, et al. Organoid cultures for cancer modeling. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(7):917–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lei Y, et al. Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer research: progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14(1):91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kelly RT. Single-cell proteomics: progress and prospects. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2020;19(11):1739–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Rappez L, et al. SpaceM reveals metabolic states of single cells. Nat Method. 2021;18(7):799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wang Y, et al. Spatial transcriptomics: technologies, applications and experimental considerations. Genomics. 2023;115(5): 110671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Liu S, et al. Immunologically effective biomaterials enhance immunotherapy of prostate cancer. J Mater Chem B. 2024. 10.1039/d3tb03044j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Keam SP, et al. High dose-rate brachytherapy of localized prostate cancer converts tumors from cold to hot. J Immunother Cancer. 2020. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Li J, et al. Secreted proteins MDK, WFDC2, and CXCL14 as candidate biomarkers for early diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Zajkowska M, Mroczko B. A novel approach to staging and detection of colorectal cancer in early stages. J Clin Med. 2023. 10.3390/jcm12103530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.McNally CJ, et al. Biomarkers that differentiate benign prostatic hyperplasia from prostate cancer: a literature review. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:5225–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Li J, et al. Clinical study of multifactorial diagnosis in prostate biopsy. Prostate. 2023;83(15):1494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Desbène C, et al. Immuno-analytical characteristics of PSA and derived biomarkers (total PSA, free PSA, p2PSA). Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2023;81(1):7–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Van den Broeck T, et al. Biochemical recurrence in prostate cancer: the european association of urology prostate cancer guidelines panel recommendations. Eur Urol Focus. 2020;6(2):231–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ge R, et al. Epigenetic modulations and lineage plasticity in advanced prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(4):470–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Lei T, et al. Effect of postoperative nadir PSA and period until nadir PSA on biochemical recurrence in patients with negative surgical margins at pathological T2 stage following radical prostatectomy. J Biol Regul Homeost Agent. 2023;37(5):2829–36. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Chowdhury S, et al. Deep, rapid, and durable prostate-specific antigen decline with apalutamide plus androgen deprivation therapy is associated with longer survival and improved clinical outcomes in TITAN patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(5):477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Chaoying L, et al. Risk factors of bone metastasis in patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2022;26(2):391–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Briganti A, et al. Predicting the risk of bone metastasis in prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(1):3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence Zn/Fe ratiometric determination of zinc levels in expressed prostatic fluid: a direct, non-invasive and highly accurate screening for prostate cancer. Acta Sci Cancer Biol. 2018;2(9):20–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yun KI, et al. Determination of prostatic fluid citrate concentration using peroxidase-like activity of a peroxotitanium complex. Anal Biochem. 2023;672: 115152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Chen G, et al. ARNT-dependent CCR8 reprogrammed LDH isoform expression correlates with poor clinical outcomes of prostate cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2020;59(8):897–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Colaprico A, et al. TCGAbiolinks: an R/Bioconductor package for integrative analysis of TCGA data. Nucl Acid Res. 2016;44(8): e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original data of the present study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.