Abstract

Introduction:

Rates of cigarette use remain elevated among those living in rural areas. Depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and weight concerns frequently accompany cigarette smoking and may adversely affect quitting. Whether treatment for tobacco use that simultaneously addresses these issues affects cessation outcomes is uncertain.

Methods:

The study was a multicenter, two-group, randomized controlled trial involving mostly rural veterans who smoke (N = 358) receiving treatment at one of five Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. The study randomly assigned participants to a tailored telephone counseling intervention or referral to their state tobacco quitline. Both groups received guideline-recommended smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, selected using a shared decision-making approach. The primary outcome was self-reported seven-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) at three and six months. The study used salivary cotinine to verify self-reported quitting at six months.

Results:

Self-reported PPA was significantly greater in participants assigned to Tailored Counseling at three (OR = 1.66; 95 % CI: 1.07–2.58) but not six (OR = 1.35; 95 % CI: 0.85–2.15) months. Post hoc subgroup analyses examining treatment group differences based on whether participants had a positive screen for elevated depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and/or concerns about weight gain indicated that the cessation benefit of Tailored Counseling at three months was limited to those with ≥1 accompanying concern (OR = 2.02, 95 % CI: 1.20–3.42). Biochemical verification suggested low rates of misreporting.

Conclusions:

A tailored smoking cessation intervention addressing concomitant risk factors enhanced short-term abstinence but did not significantly improve long-term quitting. Extending the duration of treatment may be necessary to sustain treatment effects.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking, Tobacco, Cessation, Rurality, Veterans

1. Introduction

Although the prevalence of cigarette use in the general population continues to decline, tobacco-related disparities persist among those who live in rural locations (Coughlin, Wilson, Erwin, Beckham, & Calhoun, 2019; Parker, Weinberger, Eggers, Perker, & Villanti, 2022; Roberts et al., 2016; Roberts et al., 2017; Vander Weg, Cunningham, Howren, & Cai, 2011; Yau & Okoli, 2021)—a difference that has only increased in recent years (Doogan et al., 2017). Factors that may contribute to the urban/rural differences in tobacco use include greater social acceptance of smoking in rural communities (Bernat & Choi, 2018), higher tobacco retail outlet density (Golden et al., 2020; Hall et al., 2019), less access to tobacco control resources (e.g., personnel and other resources dedicated to tobacco control, community-level tobacco control activities) (York et al., 2010), fewer smoke-free laws and voluntary restrictions against smoking in the home (Bernat & Choi, 2018; McMillen, Breen, & Cosby, 2004; Vander Weg et al., 2011), and a higher prevalence of sociodemographic characteristics associated with tobacco use (Pesko & Robarts, 2017). Those living in rural areas are also less likely to be advised to quit smoking by health care providers (Duffy et al., 2012) and to receive assistance with cessation (Heffner et al., 2021; Sardana et al., 2019). Rural residents who smoke cigarettes also have reduced access to tobacco cessation treatment (Hutcheson et al., 2008). Given that approximately 33 % of the 8.3 million veterans enrolled in VA care reside in rural areas (GAO, 2023), place-related disparities in tobacco use are particularly relevant to this group.

Common barriers to smoking cessation include depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and weight gain. Strong associations exist between cigarette smoking and difficulty quitting and both depression and alcohol use disorders (Augustson et al., 2008; Chiolero, Wietlisbach, Ruffieux, Paccaud, & Cornuz, 2006; Dawson, 2000; Falk, Yi, & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 2006; Hitsman et al., 2013; Kahler et al., 2009; Smith, Mazure, & McKee, 2014; Stepankova et al., 2017; Weinberger, Funk, & Goodwin, 2016; Weinberger, Gbedemah, & Goodwin, 2017; Ziedonis et al., 2008). Notably, rates of smoking among those with mental health and substance use disorders have not been declining at the same rates as the general population (Cook et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2018), which is likely to further exacerbate tobacco-related health disparities in these groups (Streck, Weinberger, Pacek, Gbedemah, & Goodwin, 2018). Although findings have been less consistent (Jeffery, Hennrikus, Lando, Murray, & Liu, 2000), concerns about weight gain are also associated with less success in quitting smoking (Klesges et al., 1988; Meyers et al., 1997) and are commonly cited as a reason for continued smoking and relapse (Ward, Klesges, & Vander Weg, 2001).

The presence of these concerns among cigarette smokers and their deleterious impact on quitting have prompted efforts to design interventions that address associated risk factors and are tailored to the individual needs of each smoker. Traditional tobacco cessation interventions are generally not designed to address these common concerns that many smokers experience, and efforts to coordinate treatment with other behavioral health services are often lacking. Considering that access to treatment tends to be lower in rural communities and that travel distance and other factors may make it burdensome to seek assistance for each issue separately, there may be advantages for those residing in rural areas to addressing them concurrently as part of a smoking cessation intervention. The feasibility and acceptability of this treatment approach was previously demonstrated in a single center randomized controlled trial (RCT) of rural veterans who smoke (Vander Weg et al., 2016). Building on earlier work, the current study investigated whether a tailored intervention that addresses key smoking-related concerns improves cessation outcomes in a larger multicenter trial of cigarette smoking among veterans who reside in rural areas.

2. Methods

The study was a multicenter two-group, randomized controlled trial. The study randomly assigned participants on a 1:1 ratio to one of two phone-based counseling approaches consisting of: 1) a tailored smoking cessation intervention that offered supplemental counseling to address elevated depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and/or concerns about postcessation weight gain (Tailored Counseling), or 2) referral to their state tobacco quitline (Quitline Referral). Randomization without blocking or stratification was conducted by the project data manager using a computerized algorithm. The project coordinator notified participants of their group assignment by telephone.

2.1. Participants

Participants were veterans receiving care through one of five geographically dispersed VA Medical Centers or one of their affiliated community-based outpatient clinics. To be eligible, participants had to smoke at least one cigarette per day (Notley et al., 2023; Rigotti et al., 2014), on average, and had to be willing to quit using all tobacco products. Area of residence was classified based on the VA rural designation system, which uses the United States Department of Agriculture’s Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes. This approach uses an individual’s geocoded address to arrive at a three-category designation (urban, rural, highly rural) based on population density, level of urbanization, and work commuting data (Hart, Larson, & Lishner, 2005). Urban locations are those that contain at least 30 % of the population residing in an urbanized area. Highly rural locations are sparsely populated areas for which <10 % of the working population communities to a community larger than an urbanized cluster. Rural areas are those that are not defined as urban or highly rural (VHA/ORH, 2022). The study team contacted veterans who had reported severe depressive symptoms (defined as ≥20 on the Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9] (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001)) or endorsed suicidal ideation to assess their safety and to offer a mental health referral, as appropriate, and the study excluded them from further participation. Those with a non-alcohol substance use disorder, dementia, or a serious mental illness that could interfere with phone counseling (e.g., catatonic or disorganized schizophrenia) were not eligible for participation.

2.2. Recruitment and follow-up procedures

The study used the VA Health Factors (clinical reminders) file to identify potential smokers; we also used pharmacy records to find veterans who received smoking cessation pharmacotherapy within the previous 18 months. The study sent those identified as possible smokers a letter inviting their participation along with a phone number to call for additional information. They also had the option of returning a postage-paid self-addressed postcard to indicate their interest or to opt out of study participation. Follow-up phone calls were made to those who requested more information or did not respond to the initial mailing. Study staff subsequently mailed interested smokers an informed consent document and baseline survey. The study conducted follow-up phone calls three and six months after randomization. Information about group assignment was not available in the database of outcome assessors in order to blind them to treatment condition. As part of the interview script, assessment staff also instructed participants not to reveal which treatment they received. Participants received treatment (including pharmacotherapy) free of charge but were not otherwise compensated. We randomized the first study participant on 11/19/2013. The study completed its last six-month follow-up survey on 12/5/2016. The study was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board. The study team registered the trial with ClinicalTrials.gov (registration number: NCT01892813).

2.3. Interventions

2.3.1. Tailored counseling

A detailed description of the Tailored Counseling intervention is available elsewhere (Vander Weg et al., 2016) and briefly summarized here. The intervention consisted of six sessions of cognitive behavioral counseling for smoking cessation that emphasized coping skills training and problem solving and which was delivered over the telephone. In addition to addressing cigarette smoking, the study screened participants for eligibility for each of the supplemental treatment modules as part of the baseline assessment. The study determined depressive symptoms to be elevated based on a score of 5–19 on the PHQ-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001). The study assessed alcohol use using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) (K. Bush, Kivlahan, McDonell, Fihn, & Bradley, 1998). The study used scores of ≥4 for men and ≥ 3 for women to identify those engaging in potentially risky patterns of alcohol use. We measured concerns about post-cessation weight gain on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (most ever) (Perkins et al., 2001). Those scoring >5 were offered the weight management intervention. Participants could be eligible for 0 to 3 of the supplemental modules. Decisions about whether to receive each of the modules for which they were eligible were left to the participant. The supplemental counseling material was delivered concurrently with the smoking cessation intervention during the same six phone calls. Those who were not eligible for any of the additional treatment modules and/or who declined all supplemental modules received only the tobacco cessation intervention.

Mood management:

Treatment for elevated depressive symptoms focused on behavioral activation based on an adapted version of the protocol developed by Lejuez, Hopko, Acierno, Daughters, and Pagoto (2011). Treatment emphasized helping participants increase their reinforcement density by engaging in activities that they consider enjoyable, meaningful, and consistent with their values. Behavioral activation has demonstrated benefits for enhancing cessation rates in smokers with depressive symptoms (MacPherson et al., 2010).

Alcohol risk reduction:

The alcohol use intervention was designed to be consistent with VA/Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guidelines (Department of Veterans Affairs/Department of Defense, 2009) for brief interventions in primary care and also incorporated materials developed by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Total abstinence was not required; instead, a patient-centered approach was used. The study encouraged participants to adopt low-risk drinking patterns (i.e., ≤2 drinks/day for men and ≤ 1 drink/day for women) but were allowed to set their own goals (Enggasser et al., 2015). Those who scored >8 on the AUDIT-C, or who scored ≥4/3 (for men and women, respectively) on the AUDIT-C and reported a prior history of treatment for an alcohol use disorder were offered a referral to their facility’s substance abuse treatment program (none accepted) but were allowed to continue with the study and intervention.

Weight management:

The weight management intervention emphasized traditional behavioral strategies such as goal setting, problem solving, and self-monitoring, as well as encouraging modest and manageable changes in diet and physical activity (Damschroder et al., 2014; Gokee LaRose, Tate, Gorin, & Wing, 2010). The study provided pedometers to help track activity levels. The intervention emphasized accepting and minimizing post-cessation weight gain rather than promoting weight loss.

The intervention was delivered by a Ph.D. level social worker with expertise in substance abuse, a PhD-level anthropologist with related experience, four clinical psychology doctoral students, and a master’s level counselor. Each interventionist was trained to deliver all components of the tobacco cessation intervention and supplementary modules. Interventionist training consisted of seven didactic sessions lasting 60–90 min each led by the principal investigator (MWV). Interventionists practiced delivering the treatment with peers prior to interacting with study participants. The interventionists met as a group with the PI on a weekly basis to discuss treatment strategies using a case management approach. Approximately 5 % of calls were randomly selected for review for purposes of monitoring fidelity, providing feedback, and addressing “drift” from the intervention protocol.

2.3.2. Quitline referral

Participants assigned to the QL referral condition were referred via fax to the tobacco quitline in their state of residence. Participants were enrolled from eight states served by four QL providers. To best approximate usual care, participants in the QL Referral condition received standard counseling services for which they were eligible and pharmacotherapy (described below). We made arrangements with QL providers to obtain information regarding participant enrollment and the number of treatment calls completed.

Pharmacotherapy:

The procedure for selecting smoking cessation medications was the same for both treatment conditions. Options included three forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) (patch, gum, lozenge), bupropion, and varenicline. Combination therapy was offered as appropriate.

A study nurse reviewed each participant’s electronic medical record to assess prior history of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy as well as to identify medical and psychiatric contraindications for each medication and potential drug-drug interactions. The study summarized findings in a structured electronic format to aid study prescribers in selecting medications for which the participant was medically eligible.

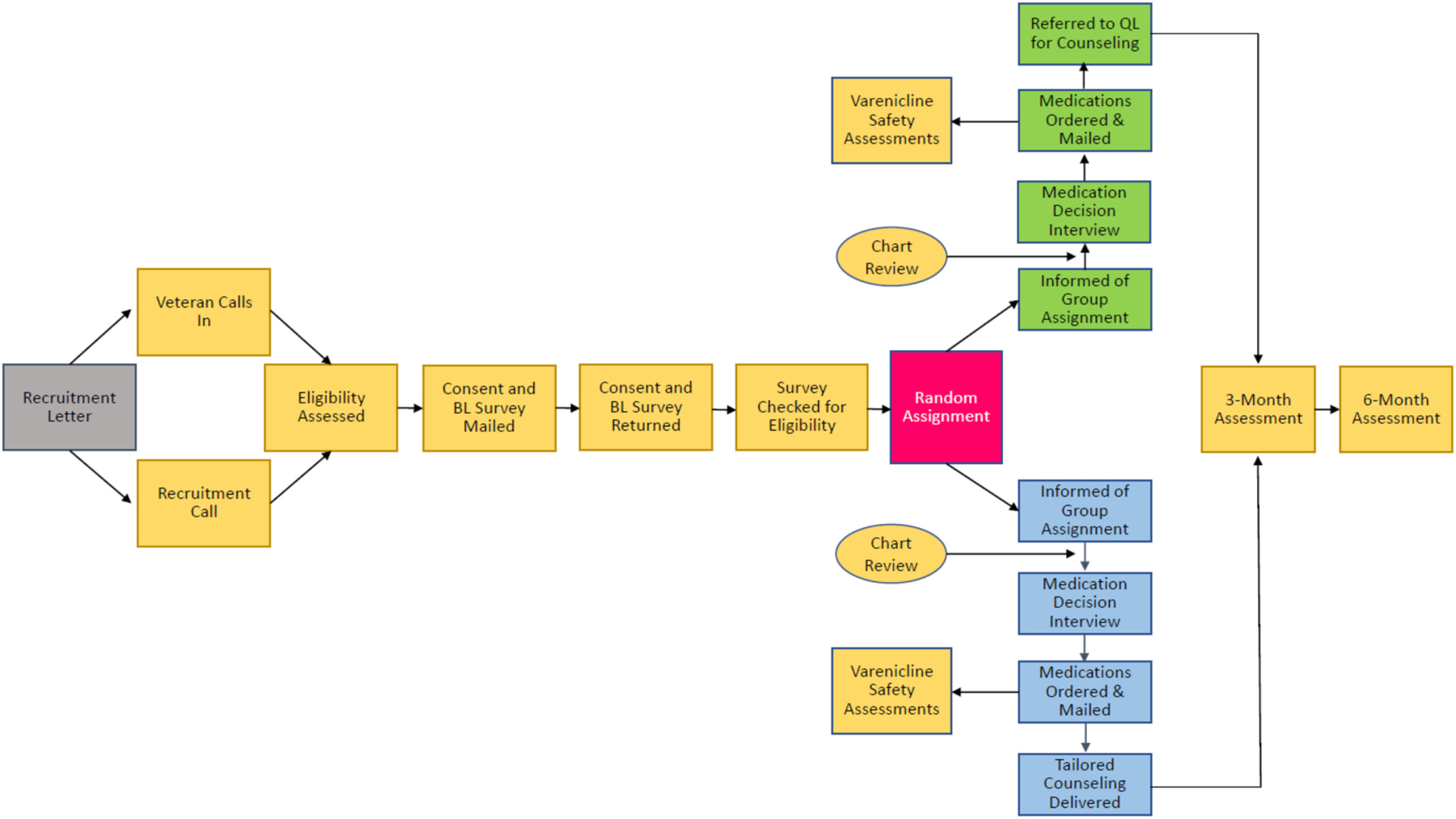

Because each medication option has been shown to be efficacious for smoking cessation (Fiore et al., 2008) with insufficient evidence about which is likely to be most beneficial for a given patient, a shared decision-making approach to selecting pharmacotherapy was used (Vander Weg et al., 2016). Study staff engaged participants in a semistructured interview regarding past experiences with smoking cessation medications, solicited ratings about the importance of eight different medication attributes, and reviewed common side effects. Medication was mailed directly to participants from their medical center’s pharmacy. In accordance with VA policy in place at the time of the trial, study team members contacted participants in both groups who were prescribed varenicline by phone every 28 days while receiving the drug to assess for neuropsychiatric side effects. Participants could request a change in their medication due to perceived lack of efficacy or side effects. A flow diagram outlining study procedures is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Study flow.

2.4. Measures

The primary outcome was self-reported seven-day point prevalence abstinence (PPA) (Piper et al., 2019), which was assessed at three- and six-months after randomization. Specifically, we asked participants whether they smoked any cigarettes during the prior seven days. The study also assessed use of other tobacco products and e-cigarettes. Those who endorsed any tobacco or e-cigarette use (on even a single occasion) were considered non-abstinent. We conducted primary analyses based on an intention-to-treat approach using penalized imputation, in which those with missing follow-up data were coded as using tobacco. In a secondary analysis, we also used a complete case approach in which participants with missing outcomes were dropped from the analysis.

Even though self-reported and biochemically verified cessation rates have been shown to have high agreement among veterans (Noonan, Jiang, & Duffy, 2013), the study mailed participants who met seven-day PPA criteria at six months a saliva collection kit for measuring cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine commonly used to confirm tobacco use status (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002). We included a brief survey to assess behaviors that could contribute to elevated cotinine levels, including recent use of cigarettes, other tobacco products, and e-cigarettes. Because cotinine is not specific to tobacco products, we also assessed use of NRT. The study shipped samples to J2 Laboratories (Tucson, AZ) for processing and quantification. A level of 15 ng/ml was used as the cut-off for verifying abstinence (SRNT Subcommittee on Biochemical Verification, 2002).

During the three-month follow-up, the study asked interview participants to rate their satisfaction with individual treatment components using the following options: extremely, very, moderately, slightly, not at all.

We included several items to help characterize the sample. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, education, occupation, and household income. Self-rated health was assessed using a single item from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthy Days measure (CDC, 2000). Items related to tobacco use history included cigarette consumption, age of smoking onset, duration of smoking, presence of other smokers in the household, and number of prior quit attempts lasting ≥24 h. Dependence on nicotine was assessed using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerstrom, 1991). Readiness to quit smoking was measured using the Readiness to Quit Ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991). Confidence in quitting was assessed with a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all confident) to 10 (Extremely confident).

2.5. Statistical analysis

The study investigated group differences in seven-day PPA through binary logistic regression analyses. As a post hoc analysis, we conducted stratified analyses to investigate whether the effect of treatment differed based on whether participants met/did not meet criteria for one or more of the supplemental treatment modules. The study examined group differences in treatment satisfaction using chi-square tests. For the purpose of this analysis, responses were dichotomized as “moderately, slightly, or not at all” vs. “very to extremely”. We conducted analyses using IBM SPSS and PSPP.

2.6. Sample size

The target sample size was 500 participants (n = 250 per group), which would provide 80 % power to detect an absolute difference in abstinence rates of 11 % (32 % vs. 21 %) at a Type I error rate of 5 % based on a two-tailed test (Lenth, 2006-9). However, financial support for the project unexpectedly ended one year early due to changes in funding agency priorities, at which time 358 participants had been enrolled and randomized to treatment conditions.

3. Results

A CONSORT diagram of participants’ flow into the study is presented in Fig. 1. Of 6574 veterans who were sent mailings about the study, 1006 (15 %) expressed potential interest. A total of 418 (42 %) met initial eligibility criteria and provided informed consent. Sixty were subsequently excluded due to significantly elevated depressive symptomatology or suicidal ideation (n = 53), lack of interest in study participation (n = 3), or because of early termination of funding (n = 4). A total of 358 smokers were randomized to treatment conditions. Two participants died prior to the three-month follow-up interview, and one died between the three- and six-month interview. The study excluded three-month follow-up data from one participant who was mistakenly interviewed early (37 days post-randomization).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Consistent with the VA population, most were middle-aged (mean = 58.8 years (SD = 12.2)), male (92 %), and white (91 %). For 39 % of the sample, the highest level of education attained was high school or less. Thirty-two percent were employed for wages, and 47 % had an annual household income of <$25,000. Forty percent reported their health as fair or poor. On average, participants reported smoking 20.3 (SD = 10.9) cigarettes per day and had been smoking regularly for a mean of 40.1 (SD = 14.3) years. The number of prior quit attempts lasting ≥24 h averaged 7.2 (SD = 11.0). Eleven percent endorsed using one or more tobacco products or electronic cigarettes in addition to combustible cigarettes. Treatment groups did not differ significantly on any of the variables reported in the table.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Variable | Total (N = 358) |

Quitline referral (n = 180) |

Tailored counseling (n = 178) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||

| Age, mean (m), standard deviation (SD) | 58.8 (12.2) | 59.0 (12.1) | 58.6 (12.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 30 (8.4) | 15 (8.3) | 15 (8.4) |

| Racial or ethnic minority1, n (%) | 31 (8.7) | 16 (8.9) | 15 (8.4) |

| High school or less education, n (%) | 138 (38.8) | 72 (40.2) | 66 (37.3) |

| Fair or poor self-rated health, n (%) | 144 (40.3) | 76 (42.2) | 68 (38.4) |

| Married, n (%) | 184 (48.6) | 99 (55.0) | 85 (47.8) |

| Employed for wages outside of home, n (%) | 102 (31.8) | 50 (30.7) | 52 (32.9) |

| Annual household income < $25,000, n (%) | 160 (47.3) | 75 (44.6) | 85 (50.0) |

| Smoking-related variables | |||

| Cigarettes smoked per day, m (SD) | 20.3 (10.9) | 20.2 (10.9) | 20.5 (11.0) |

| Age of smoking initiation, m (SD) | 16.7 (4.2) | 16.7 (4.5) | 16.6 (4.0) |

| Years as regular smoker, m (SD) | 40.1 (14.3) | 40.6 (14.7) | 39.6 (14.0) |

| Prior quit attempts lasting ≥24 h, m (SD) | 7.2 (11.0) | 7.1 (10.5) | 7.3 (11.4) |

| Live with other smokers, n (%) | 140 (39.2) | 65 (36.3) | 75 (42.1) |

| Nicotine dependence2, m (SD) | 4.9 (2.2) | 4.9 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.2) |

| Readiness to quit smoking3, m (SD) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.7 (1.4) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| Confidence in quitting4, m (SD) | 6.2 (2.2) | 6.1 (2.2) | 6.3 (2.2) |

| Use other tobacco product5, n (%) | 41 (11.5) | 24 (13.3) | 17 (9.6) |

| Mood, alcohol, and weight-related variables | |||

| Depressive symptoms6, m (SD) | 5.9 (5.0) | 6.3 (5.1) | 5.6 (5.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), m (SD) | 27.9 (5.2) | 27.6 (5.4) | 28.1 (5.1) |

| Weight concerns7, m (SD) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.4 (2.8) | 3.6 (2.9) |

| Consumes alcohol, n (%) | 236 (66.1) | 120 (66.7) | 116 (65.5) |

| Number of drinks per week, m (SD) | 9.0 (14.4) | 8.2 (12.1) | 9.8 (16.3) |

| AUDIT-C8, m (SD) | 2.3 (2.9) | 2.5 (2.9) | 2.2 (2.9) |

| Site | |||

| Ann Arbor, MI, n (%) | 39 (10.9) | 23 (6.4) | 16 (4.5) |

| Denver, CO, n (%) | 33 (9.2) | 17 (4.7) | 16 (4.5) |

| Iowa City, IA, n (%) | 206 (57.5) | 100 (27.9) | 106 (29.6) |

| Jackson, MS, n (%) | 9 (2.5) | 7 (2.0) | 2 (0.6) |

| Omaha, NE, n (%) | 71 (19.8) | 33 (9.2) | 38 (10.6) |

Hispanic (n = 4), White, Hispanic (n = 7), Black, Hispanic (n = 1), Native American, Hispanic (n = 1), Black (n = 8), Native American (n = 4), Native American and White (n = 2), Asian and Pacific Islander (n = 2), Other (n = 2).

Measured using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (Heatherton et al., 1991). Possible scores range from 0 to 10.

Measured on a scale from 1 (No interest in quitting) to 10 (Have quit and will never smoke again) using the Contemplation Ladder (Biener & Abrams, 1991).

Measured on a 10-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all confident) to 10 (extremely confident).

Includes snuff, chewing tobacco, cigars, pipe tobacco, and/or electronic cigarettes.

Measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Measured on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 10 (most ever).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Bush et al., 1998).

Participants’ mean score (and standard deviation) on the PHQ-9 was 5.9 (SD = 5.0), which is indicative of mild depressive symptoms. The mean level of concern about postcessation weight gain was 3.5 (SD = 2.9) out of 10. Scores on the AUDIT-C averaged 2.3 (SD = 2.9). Most participants (66 %) consumed alcohol at least occasionally, with a mean number of 9.0 (SD = 14.4) drinks/week. Thirty-one percent reported ever receiving treatment for alcohol use.

The proportion of participants who met eligibility criteria for each of the supplemental behavioral interventions was as follows: mood management (QL Referral = 55 %; Tailored = 47 %; χ2 (1) = 2.06, p = .15), weight management (QL Referral = 25 %; Tailored = 26 %; χ2 (1) = 0.09, p = .76), and alcohol risk reduction (QL Referral = 35 %; Tailored = 25 %; χ2 (1) = 4.37, p = .04). Although the study did not offer those in the QL Referral condition the supplemental interventions, significantly more participants assigned to QL Referral than the Tailored intervention met eligibility criteria for the alcohol intervention. Participants were eligible for a mean of 1.06 (SD = 0.80) treatment modules out of three (median and mode = 1).

3.1. Treatment receipt

3.1.1. Tailored counseling

Among the 178 participants assigned to the Tailored intervention, 161 (90 %) completed at least one treatment call. The mean (SD) number of calls completed was 4.5 (2.2) out of six. Sixty-four percent of participants completed all six intervention calls. The overall attendance rate across the calls was 75 %. Twenty four percent of participants were eligible for two modules, and 4 % were eligible for all three. Among the 84 participants in the Tailored condition who met criteria for the mood management module, 65 (78 % of those eligible) accepted the intervention. Forty-four participants met eligibility criteria for the alcohol intervention, of whom 21 (48 %) accepted the treatment. Forty-six participants were eligible for the weight management module, with 34 (74 %) accepting the intervention. Assessment of fidelity from the random sample of sessions indicated that 97 % of content from the smoking cessation intervention was covered as intended. Fidelity rates for the weight and mood management modules were 86 % and 98 %, respectively.

3.1.2. Quitline referral

Of the 180 participants assigned to the QL condition, the study referred 175 (97 %) to their state QL. The study lost four participants to follow-up before the referral could be initiated, and one asked not to be referred due to having previously received treatment through the QL. Data from QL providers indicated that 100 (55.6 % of those referred) accepted telephone counseling. Forty-six (26 %) declined counseling or were not enrolled for other reasons, while 29 (16 %) could not be reached by the QL. The median number of counseling calls completed was 3 (mean = 5.0; range = 0–38).

With regard to medication management, the nicotine patch was the most commonly chosen medication for participants in both treatment conditions (61 %), followed by the nicotine lozenge (45 %). Bupropion (21 %), varenicline (20 %), and nicotine gum (19 %) were selected less frequently (Note: because NRT and bupropion could be used as monotherapy or in combination, the total exceeds 100 %). Choice of medications did not differ significantly by group.

3.2. Smoking cessation outcomes

Seven-day self-reported PPA outcomes are presented in Table 2. Because intervention groups differed regarding eligibility for the supplemental alcohol risk reduction module, baseline AUDIT-C score (the bases for determining eligibility) was included in the models as a covariate. One hundred and fifty-eight (89 %) of those assigned to Tailored Counseling and 168 (93 %) of those assigned to QL Referral completed three-month follow-up interviews. Self-reported abstinence rates based on a penalized imputation approach were significantly higher for Tailored Counseling. Approximately 41 % of those assigned to Tailored Counseling reported abstinence at three months compared to 29 % of those assigned to QL Referral (odds ratio (OR) = 1.65; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 1.067–2.57). Those assigned to Tailored Counseling also had significantly greater odds of abstinence at three months based on complete case analysis (46 % vs. 31 %; OR = 1.83; 95 % CI: 1.16–2.88).

Table 2.

Self-reported seven-day point prevalence abstinence by group.

| Outcome | Tailored counseling (n = 177) |

Quitline referral (n = 178) |

OR (95 % CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three months (post treatment) | |||

| Penalized imputation | 40.7 | 29.2 | 1.65 (1.06–2.57) |

| Complete case analysisb | 45.6 | 31.0 | 1.83 (1.16–2.88) |

| Six months | |||

| Penalized imputation | 31.3 | 25.1 | 1.37 (0.86–2.19) |

| Complete case analysisc | 35.7 | 27.4 | 1.49 (0.92–2.47) |

Adjusted for baseline AUDIT-C score.

Based on 326 participants (n = 158 for Tailored Counseling condition and n = 168 for QL Referral condition).

Based on 318 participants (n = 154 for Tailored Counseling condition and n = 164 for QL Referral condition.

Abstinence rates at six months remained greater among those assigned to Tailored Counseling, but differences between treatment conditions were no longer statistically significant. Based on a penalized imputation approach, rates of self-reported abstinence were 31 % for the Tailored intervention, compared to 25 % for those receiving QL Referral (OR = 1.37; 95 % CI: 0.86–2.19). Abstinence rates based on complete case analysis were 36 % for those in the Tailored condition and 27 % for those in the QL referral condition (OR = 1.49; 95 % CI: 0.92–2.47).

3.3. Biochemical verification

The study sent salivary cotinine collection kits to the 100 participants (n = 55 in the Tailored condition and n = 45 in the QL Referral condition) who reported seven-day PPA at six-months. Of the 73 participants who returned samples, eight reported using tobacco in the seven days prior to their sample collection. Saliva samples were not interpretable from 14 participants who reported using NRT in the past seven days (which would result in a positive cotinine test) and two additional participants whose sample was insufficient for processing. Cotinine levels from the remaining 49 participants indicated that 46 (94 %) met criteria for abstinence, while three (6 %) had levels that were at or above the cut-off (QL Referral = 1; Tailored = 2). Rates of biochemical verification of self-reported abstinence did not differ by group (χ2 (1) = 0.17, p = .68).

3.4. Post hoc analyses

In post hoc analyses, we examined self-reported abstinence by group based on whether participants screened positive for any of the concerns addressed in the supplemental treatment modules (Table 3). A difference in cessation outcome favoring Tailored Counseling was only evident among those with ≥1 accompanying concern related to elevated depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and/or concerns about weight gain (OR = 2.02, 95 % CI: 1.20–3.42) at three months. As with the primary analyses, however, results were no longer statistically significant at six months. Among participants who were not eligible for any of the supplemental treatment modules, self-reported quit rates did not differ by condition at either three or six months.

Table 3.

Post hoc analysis of self-reported seven-day point prevalence abstinence by group stratified by the number of supplemental treatment modules for which participants were eligible.

| |

Eligible for 0 modules |

Eligible for ≥ 1 module |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Tailored counseling (n = 56) | Quitline referral (n = 35) | OR (95 % CI) | Tailored counseling (n = 121) | Quitline referral (n = 143) | OR (95 % CI) |

| Three months (Post-treatment) | ||||||

| Penalized imputation | 41.1 | 45.7 | 0.83 (0.35–1.94) | 40.5 | 25.2 | 2.02 (1.20–3.42) |

| Complete case analysisa | 50.0 | 47.1 | 1.13 (0.46–2.73) | 43.8 | 26.9 | 2.12 (1.24–3.61) |

| Six months | ||||||

| Penalized imputation | 40.0 | 40.0 | 1.00 (0.42–2.38) | 27.3 | 21.5 | 1.37 (0.78–2.40) |

| Complete case analysisb | 46.8 | 42.4 | 1.19 (0.49–2.93) | 30.8 | 23.7 | 1.44 (0.81–2.56) |

Based on 80 participants who were eligible for 0 modules (n = 46 for the Tailored Counseling condition and n = 34 for the QL Referral condition) and 246 participants who were eligible for ≥1 module (n = 112 for the Tailored Counseling condition and n = 134 for the QL Referral condition).

Based on 80 participants who were eligible for 0 modules (n = 47 for the Tailored Counseling condition and n = 33 for QL Referral condition) and 238 participants who were eligible for ≥1 module (n = 107 for the Tailored Counseling condition and n = 131 for the QL Referral condition).

3.5. Treatment satisfaction

The study assessed satisfaction with the counseling and medication components of treatment and compared them by group. Participants’ satisfaction with treatment was generally greater for those assigned to the Tailored intervention compared to QL Referral. Perceived usefulness of treatment for quitting (60 vs. 28 %), usefulness of phone counseling (63 vs. 30 %), convenience of treatment (74 vs. 48 %), perceived difficulty (14 vs. 24 %), and how much participants liked that the intervention was delivered by phone (81 vs. 57 %) were all significantly better for those receiving Tailored Counseling versus Quitline Referral, respectively (p’s ≤ 0.05). The only dimension of treatment satisfaction that did not differ between groups was perceived usefulness of cessation medication, which was selected and provided according to an identical protocol in both groups.

Discussion

This study examined the efficacy of a novel tobacco use treatment approach that addressed additional concerns commonly experienced by those attempting to quit. A tailored smoking cessation intervention for rural veterans that offered supplemental behavioral counseling for elevated depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, and weight concerns was associated with significantly increased seven-day PPA at three months. Although quit rates for those assigned to Tailored Counseling remained greater at the six-month follow-up, differences were no longer statistically significant. Those who were eligible for ≥1 of the supplemental treatment modules, with or without having participated in supplemental counseling, tended to benefit most from the tailored intervention approach, at least in the short-term, while those without depressive symptoms, risky alcohol use, or concerns about weight gain did as well with QL referral.

Results from this study add to a small but growing literature on smoking cessation intervention strategies for rural tobacco users. Despite the increased burden of tobacco use and tobacco-related health problems in rural communities, relatively few clinical trials have been conducted specifically with this group. Given differences in sociodemographic characteristics and health care access and utilization, it is unclear whether strategies found to be effective in the general population will translate to rural cigarette smokers. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions in rural and remote populations found significant benefit for individual facet-to-face counseling (Vance, Glanville, Ramkumar, Chambers, & Tzelepis, 2022). However, the study found no significant effects for other forms of treatment including telephone counseling, NRT, or community-based multiple interventions. Further, the quality of evidence was considered very low for all comparisons. The authors concluded that additional high quality studies are needed to establish the evidence base in this area (Vance et al., 2022), a conclusion mirrored by others, as well (Coughlin, 2020; Gupta et al., 2020).

In contrast to conclusions from the systematic review by Vance et al. (2022), which were based on only two trials involving telephone counseling, the present results are encouraging regarding the potential for state tobacco quitlines to overcome place-related barriers to treatment access and to assist large portions of rural cigarette smokers in their quitting efforts. Among those experiencing difficulties related to symptoms of depression, concerns about weight gain, and risk alcohol use, quitlines still remain a viable treatment delivery option. However, as observed in the present study, quit rates tend to be lower among those with mental health and/or substance use disorders (Kerkvliet, Wey, & Fahrenwald, 2015; Tedeschi et al., 2016; Toll et al., 2012), leading to suggestions to screen for and provide personalized counseling for these conditions. Although addressing each of these issues in a single intervention protocol as was done here is not the convention, prior studies have demonstrated that state or national quitlines that address hazardous drinking (Toll et al., 2015), symptoms of depression (van der Meer, Willemsen, Smit, Cuijpers, & Schippers, 2010), and weight concerns (Bush et al., 2012) concurrently with tobacco use can be effective.

Overall, studies evaluating tailored behavioral interventions to address comorbid behavioral risk factors such as depression, risky alcohol use, and weight concerns in the context of treatment for cigarette use have yielded mixed, but generally promising, findings (Ames, Pokorny, Schroeder, Tan, & Werch, 2014; Duffy et al., 2006; Gierisch, Bastian, Calhoun, McDuffie, & Williams Jr., 2012; Kahler et al., 2008; Spring et al., 2009; Toll et al., 2015). Considering the tendency of smoking to cluster with other risky behaviors (Meader et al., 2016) and the high rates of mental health comorbidities among cigarette users (Smith et al., 2018), these findings demonstrate the potential benefit of addressing these issues concurrently without adversely affecting, and possibly even enhancing, treatment success.

Findings also suggest that for the intervention to have a long-term benefit, extended treatment duration and/or ongoing monitoring to provide assistance in the event of a lapse may be necessary. Several trials have demonstrated that providing treatment over a longer time period improves cessation outcomes (Hall et al., 2009; Hall et al., 2011; Joseph et al., 2011). This may be particularly important for those with comorbid mental health conditions or substance use disorders (Hitsman, Moss, Montoya, & George, 2009; Okoli & Khara, 2014). Despite these benefits and calls to provide and reimburse long-term treatment for tobacco dependence in a manner similar to other chronic conditions (Steinberg, Schmelzer, Richardson, & Foulds, 2008), this model has not been integrated into routine clinical practice (Hall, 2017).

Strengths of the study include the novel patient-centered treatment approach, which included supplemental behavioral counseling for issues commonly faced by smokers attempting to quit. A sizable proportion of rural veterans were eligible for and receptive to receiving these forms of counseling in the context of a quit attempt, which suggests that the Tailored intervention has the potential to reach many smokers. At the same time, smokers did not have to meet criteria for any of these conditions - or accept treatment for them - to participate. This pragmatic approach is arguably more consistent with how a multiple risk factor intervention might be implemented in clinical practice. The shared decision-making approach to smoking cessation medication also represents a unique strategy for selecting from among multiple evidence-based options. The focus on rural residents, who tend to have higher rates of tobacco use and less access to treatment, and pragmatic eligibility criteria were other positive features.

Limitations include the fact that recruitment ended prior to attaining the target sample size due to early termination of funding. In addition, the approach to selecting and providing smoking cessation medication for the QL Referral group deviated from usual care, and likely decreased the probability of detecting a significant treatment effect. In order to evaluate the tailored counseling approach, however, we considered it important not to vary the process for providing medications (or the way they were selected) across treatment conditions. Finally, participants self-selected whether to receive supplemental counseling related to comorbid concerns (Tailored Counseling) and choose smoking cessation medications (both conditions), which introduces potential bias that complicates attributions of causal inference. On the other hand, this more closely represents what would occur in practice, and is consistent with the patient-centered approach that we sought to adopt. Additionally, although we monitored treatment fidelity as it related to delivery of the intervention, we did not formally assess participant adherence to counseling recommendations. Finally, because the sample consisted entirely of veterans, most of whom were male and white, and reflected other sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., employment outside the home, household income, self-rated health) that are not representative of the overall population, generalizability to other smokers is uncertain.

In summary, a Tailored Counseling intervention for rural veterans who are smokers increased three-month abstinence rates but did not significantly improve quitting at six months. Notably, attempting to quit while also managing other health behaviors did not adversely affect cessation outcomes, a concern that has been raised about addressing comorbid risk factors in the context of smoking cessation. The short-term benefits of the Tailored approach were limited to those dealing with additional smoking-related concerns; for those without these concerns, similar cessation outcomes were observed with quitline referral. To enhance long-term quit rates, future trials should evaluate strategies to augment the potency of tailored counseling and to determine the effectiveness of extending the duration of treatment. Strategies for effectively integrating a tailored intervention strategy into routine primary care should also be explored.

Funding source

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Rural Health, Veterans Rural Health Resource Center-Iowa City (Award 15025). The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study, data collection or analysis. They also had no role in the decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of George Bailey with data acquisition as well as database development and management, Ashley Montgomery with study coordination, and Misha Quill, Ph.D. with intervention delivery.

Declaration of competing interest

None of the authors has a conflict of interest to disclose related to this work.

References

- Ames SC, Pokorny SB, Schroeder DR, Tan W, & Werch CE (2014). Integrated smoking cessation and binge drinking intervention for young adults: A pilot efficacy trial. Addictive Behaviors, 39(5), 848–853. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustson EM, Wanke KL, Rogers S, Bergen AW, Chatterjee N, Synder K, … Caporaso NE (2008). Predictors of sustained smoking cessation: A prospective analysis of chronic smokers from the alpha-tocopherol Beta-carotene cancer prevention study. American Journal of Public Health, 98(3), 549–555. 10.2105/ajph.2005.084137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat DH, & Choi K (2018). Differences in cigarette use and the tobacco environment among youth living in metropolitan and nonmetropolitan areas. The Journal of Rural Health, 34(1), 80–87. 10.1111/jrh.12194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biener L, & Abrams DB (1991). The contemplation ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 10(5), 360–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, & Bradley KA (1998). The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(16), 1789–1795. 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush T, Levine MD, Beebe LA, Cerutti B, Deprey M, McAfee T, … Zbikowski S (2012). Addressing weight gain in smoking cessation treatment: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Health Promotion, 27, 94–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2000). Measuring healthy days: Population assessment of health-related quality of life. Atlanta, GA: CDC. [Google Scholar]

- Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, & Cornuz J (2006). Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: A population-based survey. Preventive Medicine, 42(5), 348–353. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Wayne GF, Kafali EN, Liu Z, Shu C, & Flores M (2014). Trends in smoking among adults with mental illness and association between mental health treatment and smoking cessation. Jama, 311(2), 172–182. 10.1001/jama.2013.284985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin LN, Wilson SM, Erwin MC, Beckham JC, & Calhoun PS (2019). Cigarette smoking rates among veterans: Associations with rurality and psychiatric disorders. Addictive Behaviors, 90, 119–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS (2020). Smoking cessation treatment among rural residents. Cardiovascular Disorders and Medicine, 1(10), 47496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Lutes LD, Kirsh S, Kim HM, Gillon L, Holleman RG, … Richardson CR (2014). Small-changes obesity treatment among veterans: 12-month outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(5), 541–553. 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA (2000). Drinking as a risk factor for sustained smoking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 59(3), 235–249. 10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00130-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defense, D. o. V. A. a. D. o. (2009). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of substance use disorders (SUD). Retrieved from Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Doogan NJ, Roberts ME, Wewers ME, Stanton CA, Keith DR, Gaalema DE, … Higgins ST (2017). A growing geographic disparity: Rural and urban cigarette smoking trends in the United States. Preventive Medicine, 104, 79–85. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy SA, Kilbourne AM, Austin KL, Dalack GW, Woltmann EM, Waxmonsky J, & Noonan D (2012). Risk of smoking and receipt of cessation services among veterans with mental disorders. Psychiatric Services, 63(4), 325–332. 10.1176/appi.ps.201100097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy SA, Ronis DL, Valenstein M, Lambert MT, Fowler KE, Gregory L, … Terrell JE (2006). A tailored smoking, alcohol, and depression intervention for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, 15(11), 2203–2208. 10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-05-0880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enggasser JL, Hermos JA, Rubin A, Lachowicz M, Rybin D, Brief DJ, … Keane TM (2015). Drinking goal choice and outcomes in a Web-based alcohol intervention: Results from VetChange. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 63–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk DE, Yi HY, & Hiller-Sturmhofel S (2006). An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Research & Health, 29(3), 162–171. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, … Wewers ME (2008). Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical practice guideline. Retrieved from Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- GAO. (2023). VA Mental Health: Additional action needed to assess rural veterans’ access to intensive care (GAO-23–105544.). Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-23-105544.

- Gierisch JM, Bastian LA, Calhoun PS, McDuffie JR, & Williams JW Jr. (2012). Smoking cessation interventions for patients with depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(3), 351–360. 10.1007/s11606-011-1915-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokee LaRose J, Tate DF, Gorin AA, & Wing RR (2010). Preventing weight gain in young adults: A randomized controlled pilot study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(1), 63–68. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden SD, Kuo T-M, Kong AY, Baggett CD, Henriksen L, & Ribisl KM (2020). County-level associations between tobacco retailer density and smoking prevalence n teh USA, 2012. Preventive Medicine Reports, 17, Article 101005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Scheuter C, Kundu A, Bhat N, Cohen A, & Facente SN (2020). Smoking cessation interventions in Appalachia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 58, 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Cho HD, Maldonado-Molina M, George TJ, Shenkman EA, & Salloum RG (2019). Rural-urban disparities in tobacco retail access in teh southeastern United States: CVS vs. the dollar stores. Preventive Medicine Reports, 15, Article 100935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM (2017). Commentary on Laude et al. (2017): Extended treatment for cigarette smoking cessation. Addiction, 112(8), 1460–1461. 10.1111/add.13884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Prochaska JJ, & Robbins JA (2011). Using extended cognitive behavioral treatment and medication to treat dependent smokers. American Journal of Public Health, 101(12), 2349–2356. 10.2105/ajph.2010.300084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Humfleet GL, Munoz RF, Reus VI, Robbins JA, & Prochaska JJ (2009). Extended treatment of older cigarette smokers. Addiction, 104(6), 1043–1052. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02548.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart LG, Larson EH, & Lishner DM (2005). Rural definitions for health policy and research. American Journal of Public Health, 95, 1149–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerstrom KO (1991). The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heffner JL, Coggeshall S, Wheat CL, Krebs P, Feemster LC, Klein DE, … Zeliadt SB (2021). Receipt of tobacco treatment and one-year smoking cessation rates following lung cancer screening in the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37, 1704–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitsman B, Moss TG, Montoya ID, & George TP (2009). Treatment of tobacco dependence in mental health and addictive disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(6), 368–378. 10.1177/070674370905400604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitsman B, Papandonatos GD, McChargue DE, DeMott A, Herrera MJ, Spring B, … Niaura R (2013). Past major depression and smoking cessation outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis update. Addiction, 108(2), 294–306. 10.1111/add.12009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson TD, Greiner KA, Ellerbeck EF, Jeffries SK, Mussulman LM, & Casey GN (2008). Understanding smoking cessation in rural communities. The Journal of Rural Health, 24(2), 116–124. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2008.00147.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery RW, Hennrikus DJ, Lando HA, Murray DM, & Liu JW (2000). Reconciling conflicting findings regarding postcessation weight concerns and success in smoking cessation. Health Psychology, 19(3), 242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph AM, Fu SS, Lindgren B, Rothman AJ, Kodl M, Lando H, … Hatsukami D (2011). Chronic disease management for tobacco dependence: A randomized, controlled trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(21), 1894–1900. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Borland R, Hyland A, McKee SA, Thompson ME, & Cummings KM (2009). Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) four country survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 100(3), 214–220. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Metrik J, LaChance HR, Ramsey SE, Abrams DB, Monti PM, & Brown RA (2008). Addressing heavy drinking in smoking cessation treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(5), 852–862. 10.1037/a0012717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkvliet JL, Wey H, & Fahrenwald NL (2015). Cessation among state quitline participants with a mental health condition. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17, 735–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klesges RC, Brown K, Pascale RW, Murphy M, Williams E, & Cigrang JA (1988). Factors associated with participation, attrition, and outcome in a smoking cessation program at the workplace. Health Psychology, 7(6), 575–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JB (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, & Pagoto SL (2011). Ten year revision of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: Revised treatment manual. Behavior Modification, 35(2), 111–161. 10.1177/0145445510390929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth RV (2006-September). Java applets for power and sample size (computer software). Retrieved from http://www.stat.uiowa.edu/~rlenth/Power. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, Rodman S, Strong DR, Kahler CW, … Lejuez CW (2010). Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(1), 55–61. 10.1037/a0017939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillen R, Breen J, & Cosby AG (2004). Rural-urban differences in the social climate surrounding environmental tobacco smoke: a report from the 2002 Social Climate Survey of Tobacco Control. The Journal of Rural Health, 20(1), 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meader N, King K, Moe-Byrne T, Wright K, Graham H, Petticrew M, … Sowden AJ (2016). A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health, 16, 657. 10.1186/s12889-016-3373-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, Cuijpers P, & Schippers GM (2010). Effectiveness of a mood managemetn component as an adjunct to a telephone counseling smoking cessation intervention for smokers with a past major depression: A pragrmatic randomized controlled trial. Addiction, 105, 1991–1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers AW, Klesges RC, Winders SE, Ward KD, Peterson BA, & Eck LH (1997). Are weight concerns predictive of smoking cessation? A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(3), 448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan D, Jiang Y, & Duffy SA (2013). Utility of biochemical verification of tobacco cessation in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Addictive Behaviors, 38(3), 1792–1795. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notley C, Clark L, Belderson P, Ward E, Clark AB, Parrott S, … Pope I (2023). Cessation of smoking trial in the emergency department (CoSTED): Protocol for a multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 13(1), Article e064585. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okoli CT, & Khara M (2014). Smoking cessation outcomes and predictors among individuals with co-occurring substance use and/or psychiatric disorders. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 10(1), 9–18. 10.1080/15504263.2013.866860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Weinberger AH, Eggers EM, Perker ES, & Villanti AC (2022). Trends in rural and urban cigarette smoking quit ratios in the US. JAMA Network Open, 5, Article e2225326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, D’Amico D, Miller A, Broge M, … Shiffman S (2001). Cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce weight concerns improves smoking cessation outcome in weight-concerned women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 604–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesko MF, & Robarts AMT (2017). Adolescent tobacco use in urban versus rural areas of the United States: The influence of tobacco control policy environments. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(1), 70–76. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Bullen C, Krishnan-Sarin S, Rigotti NA, Steinberg ML, Streck JM, & Joseph AM (2019). Defining and measuring abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions: An updated review. Nicotine &Tobacco Research, 22(7), 1098–1106. 10.1093/ntr/ntz110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigotti NA, Regan S, Levy DE, Japuntich S, Chang Y, Park ER, … Singer DE (2014). Sustained care intervention and postdischarge smoking cessation among hospitalized adults: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 312, 719–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Kurti AN, Redner R, Gaalema DE, Stanton CA, … Higgins ST (2016). Rural tobacco use across the United States: How rural and urban areas differ, broken down by census regions and divisions. Health & Place, 39, 153–159. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Stanton CA, Quisenberry AJ, Villanti AC, Gaalema DE, … Higgins ST (2017). Rural versus urban use of traditional and emerging tobacco products in the United States, 2013–2014. American Journal of Public Health, 107(10), 1554–1559. 10.2105/ajph.2017.303967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardana M, Tang Y, Magnani JW, Ockene IS, Allison JJ, Arnold SV, … McManus DD (2019). Provider-level variation in smoking cessation assistance provided in the cardiology clinics: Insights from teh NCDR Pinnacle registry. Journal of the American Heart Association, 8, Article e011307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Chhipa M, Bystrik J, Roy J, Goodwin RD, & McKee SA (2018). Cigarette smoking among those with mental disorders in the US population: 2012–2013 update. Tobacco Control 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PH, Mazure CM, & McKee SA (2014). Smoking and mental illness in the U. S. population. Tobacco Control, 23(e2), e147–e153. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spring B, Howe D, Berendsen M, McFadden HG, Hitchcock K, Rademaker AW, & Hitsman B (2009). Behavioral intervention to promote smoking cessation and prevent weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction, 104(9), 1472–1486. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02610.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg MB, Schmelzer AC, Richardson DL, & Foulds J (2008). The case for treating tobacco dependence as a chronic disease. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148(7), 554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepankova L, Kralikova E, Zvolska K, Pankova A, Ovesna P, Blaha M, & Brose LS (2017). Depression and smoking cessation: Evidence from a smoking cessation clinic with 1-year follow-up. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(3), 454–463. 10.1007/s12160-016-9869-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streck JM, Weinberger AH, Pacek LR, Gbedemah M, & Goodwin RD (2018). Cigarette smoking quit rates among persons with serious psychological distress in the United States from 2008–2016: Are mental health disparities in cigarette use increasing? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/nty227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi GJ, Summins SE, Anderson CM, Anthenelli RM, Zhuang YL, & Zhu SH (2016). Smokers with self-reported mental health conditions: A case for screening in the context of tobacco cessation services. PLoS One, 11, Article e0159127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Cummings KM, O’Malley SS, Carlin-Menter S, McKee SA, Hyland A, … Celestino P (2012). Tobacco quitlines need to assess and intervene with callers’ hazardous drinking. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 36, 1653–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Martino S, O’Malley SS, Fucito LM, McKee SA, Kahler CW, … Cummings KM (2015). A randomized trial for hazardous drinking and smoking cessation for callers to a quitline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 445–454. 10.1037/a0038183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance L, Glanville B, Ramkumar K, Chambers J, & Tzelepis F (2022). The effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in rural and remote populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Drug Policy, 106, Article 103775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Weg MW, Cozad AJ, Howren MB, Cretzmeyer M, Scherubel M, Turvey C, … Katz DA (2016). An individually-tailored smoking cessation intervention for rural veterans: A pilot randomized trial. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 811. 10.1186/s12889-016-3493-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Weg MW, Cunningham CL, Howren MB, & Cai X (2011). Tobacco use and exposure in rural areas: Findings from the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Addictive Behaviors, 36(3), 231–236. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verification S. S. o. B. (2002). Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 4(2), 149–159. 10.1080/14622200210123581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VHA/ORH. (2022). Rural definition. Rural veterans Health Care Atlas. Retrieved from https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/aboutus/ruralvets.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Ward KD, Klesges RC, & Vander Weg MW (2001). Cessation of smoking and body weight. In Bjorntorp P (Ed.), International textbook of obesity. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Funk AP, & Goodwin RD (2016). A review of epidemiologic research on smoking behavior among persons with alcohol and illicit substance use disorders. Preventive Medicine, 92, 148–159. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, & Goodwin RD (2017). Cigarette smoking quit rates among adults with and without alcohol use disorders and heavy alcohol use, 2002–2015: A representative sample of the United States population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 204–207. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yau MTK, & Okoli CTC (2021). Associations of tobacco use and consumption with rurality among patients with psychiatric disorders: Does smoke-free policy matter? The Journal of Rural Health, 38, 364–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York NL, Rayens MK, Zhang M, Jones LG, Casey BR, & Hahn EJ (2010). Strength of tobacco control in rural communities. The Journal of Rural Health, 26(2), 120–128. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00273.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, Zvolensky M, Adler LE, Audrain-McGovern J, … Riley WT (2008). Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10 (12), 1691–1715. 10.1080/14622200802443569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]