Abstract

Objective

Branch atheromatous disease (BAD) is a form of ischemic stroke that presents with imaging findings similar to those of lacunar infarction, but has a different pathogenesis and is known to cause progressive paralysis. Due to regional variations, the epidemiology of BAD is not well understood, and its relationship with the functional prognosis remains unclear. Using a comprehensive Japanese stroke database, we investigated its epidemiological characteristics and associations with functional outcomes.

Methods

In this multicenter cohort study, we retrospectively analyzed data from 27 hospitals that contributed to the Saiseikai Stroke Database (2013–2021). We used multivariable logistic regression to calculate adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of BAD compared with lacunar infarction (LI) for functional outcomes at discharge. Ischemic stroke caused by BAD or LI was included, and demographic characteristics and clinical data were evaluated and contrasted between BAD and LI.

Results

Of the 5,966 analyzed patients, 1,549 (25.9%) had BAD and 4,434 (74.1%) had LI. BAD was associated with worse functional outcomes (aOR, 2.77; 95% CI, 2.42–3.17; relative to LI) and extended hospital stays (median 19 days for BAD vs. 13 days for LI). Moreover, aggressive treatment strategies, including the use of argatroban and dual antiplatelet therapy, were more common in BAD patients.

Conclusion

BAD presented worse functional outcomes and longer hospital stays than LI, necessitating treatment plans that take into account its progression and prognosis.

Keywords: Ischemic stroke, Branch atheromatous disease, Lacunar stroke, Functional outcome, Antithrombotic therapy, Epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic stroke represents a pressing global health issue, frequently leading to functional disabilities [1]. The subtype of ischemic stroke known as branch atheromatous disease (BAD) presents unique challenges for clinicians, characterized by its rapid progression and resistance to treatment [2]. First described by Caplan [3] in 1989, BAD is distinct from lacunar infarction (LI)—another subtype affecting perforating arteries—by virtue of its specific clinical characteristics [2,4,5]. Although BAD is known to predominantly affect the Asian population, with approximately 9.1% of stroke cases in Japan being BAD-related, the comprehensive epidemiological understanding of this disease remains limited [6]. Reasons for the poor epidemiological understanding of this disease include geographic differences in prevalence, the small size of most existing studies, and the absence of BAD as a distinct category in large databases such as general health registries and insurance records [7–9]. Moreover, a consensus on effective treatment strategies is yet to be reached, often leading to aggressive treatment proposals [10].

The above background highlights the importance of acquiring precise epidemiological data on BAD, a disease that is often challenging to treat, and investigating differences in outcomes between BAD and LI. This study focused on filling this gap by using a comprehensive Japanese stroke database. This knowledge may prove instrumental in predicting stroke patient prognosis and enhancing treatment methodologies. In this study, we aimed to determine epidemiology of BAD and the association of BAD and LI with functional outcome. Furthermore, we strive to elucidate the association of these conditions with functional outcomes, thereby contributing to the development of better therapeutic strategies and improvement of patient prognosis.

METHODS

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the institutional ethics review boards of Saiseikai Shiga Hospital (No. 226) and Tokyo Saiseikai Central Hospital (No. 28-15), which were the core hospitals of this registry. The ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent because of the anonymity of data.

Study design and setting

The study utilized data from the Saiseikai Stroke Database. This database is a prospective registry of acute stroke patients collected within the first week after stroke onset. The Saiseikai Stroke Research Group is composed of 27 hospitals under the Social Welfare Organization Saiseikai Imperial Gift Foundation in Japan. The registry was operational from April 2013 to March 2021. Details and data from the Saiseikai Stroke Database can be found in Supplementary Material 1 and have been published previously [11].

Participants

Our study included cases of ischemic stroke due to BAD and LI registered in the Saiseikai Stroke Database between 2013 and 2021. We excluded patients younger than 16 years, those with incomplete discharge modified Rankin Scale (mRS) data, and patients diagnosed with stroke subtypes other than BAD or LI. Stroke diagnoses were categorized according to the TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) criteria in this database [12]. In this database, BAD patients were recorded independently of atherothrombotic and LI, and they were diagnosed and enrolled by the stroke specialist at the institution. Generally, patients with intracerebral lesions with a diameter of ≥15 mm and more than three slices or lesions extending to the surface of the pontine base were defined as BAD, according to previous reports [3,13]. The diagnosis of LI generally followed the TOAST criteria, which includes the following: (1) lesion location in the subcortical hemisphere or brainstem; (2) size less than 1.5 cm as evaluated by computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) no potential cardiac source of embolism; and (4) no stenosis greater than 50% in an ipsilateral artery.

Data collection and variables

The following clinical data were collected and analyzed from the Saiseikai Stroke Database: sex, age, medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, and previous stroke), smoking habits, ongoing antithrombotic therapy, level of consciousness on arrival (Japan Coma Scale [JCS]) [14,15], lesion vessel, acute phase medical treatment, intervention (mechanical thrombectomy), mRS at discharge, and in-hospital mortality. The JCS, a consciousness rating scale specific to Japan, is a reliable tool for assessing intracranial disease, and it can also be converted to the Glasgow Coma Scale (Supplementary Tables 1, 2) [16,17]. In this database, the diagnosis was classified according to the artery from which the dominant vessel of the lesion originated. Thus, the territories registered as BAD vascular lesions were determined to be the following: middle cerebral artery as lenticulostriate form artery, basilar artery as paramedian pontine artery, posterior cerebral artery as thalamoperforating artery, internal carotid artery as anterior choroidal artery, and anterior cerebral artery as Heubner artery [2,9].

Outcomes

The outcome of this study was poor functional outcome as assessed by mRS at discharge, as well as length of hospital stay. We defined good functional outcome as an mRS score of 0 to 2 and poor functional outcome as an mRS score of 3 to 6 [11].

Statistical analysis

In our study, we analyzed the characteristics and clinical data of patients in both groups (BAD group, LI group) utilizing the Wilcoxon rank sum test for numerical variables and Pearson chi-square test for categorical variables. We conducted logistic regression analyses for the groups to determine adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for BAD outcomes, accompanied by 95% confidence intervals (CIs), compared with LI outcomes. We identified potential confounders including sex, categorized age, previous medical history, categorized JCS scores (each digit), and vascular lesions. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to estimate aORs for BAD outcomes, including their 95% CIs. Point estimates with 95% CIs were used to present statistical results. In addition, a similar subgroup analysis was performed by classifying lesions into internal carotid artery, anterior cerebral artery, middle cerebral artery, basilar artery, and posterior cerebral artery vascular lesions. We determined statistical significance as a nonoverlap of the 95% CIs with the null effect value (OR, 1) or a two-sided P-value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Pro 17 software (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics, clinical findings, and treatment

Of the 27,691 patients registered in the Saiseikai Stroke Database, 5,966 patients were eligible for analysis: 1,549 (25.9%) in the BAD group and 4,434 (74.1%) in the LI group. The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. The background characteristics and clinical data of the patients are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. In the entire cohort, 3,579 (60.0%) were male, 1,349 (22.6%) were 64 years old or younger, 1,653 (27.7%) were 65 to 74 years old, and 2,964 (49.7%) were at least 75 years old. In the BAD group, 828 (53.6%) were at least 75 years old, and 1,108 (71.7%) had hypertension. Patient background information was generally similar in both groups.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient selection. BAD, branch atheromatous disease; LI, lacunar infarction. a)The sum exceeds the total number of exclusions as there is an overlap in the subcategory counts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | Total (n=5,966) | BAD group (n=1,545) | LI group (n=4,421) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 3,579 (60.0) | 828 (53.6) | 2,751 (62.2) | <0.01 |

| Age (yr) | <0.01 | |||

| ≤64 | 1,349 (22.6) | 309 (20.0) | 1,040 (23.5) | |

| 65–74 | 1,653 (27.7) | 408 (26.4) | 1,245 (28.2) | |

| ≥75 | 2,964 (49.7) | 828 (53.6) | 2,136 (48.3) | |

| Past medical history | ||||

| Hypertension | 4,034 (67.6) | 1,108 (71.7) | 2,926 (66.2) | <0.01 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2,319 (38.9) | 647 (41.9) | 1,672 (37.8) | 0.35 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,632 (27.4) | 449 (29.1) | 1,183 (26.8) | 0.08 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 693 (11.6) | 179 (11.6) | 514 (11.6) | 0.97 |

| Congestive heart failure | 190 (3.2) | 61 (4.0) | 129 (2.9) | 0.05 |

| Previous stroke | 1,562 (26.2) | 349 (22.6) | 1,213 (27.4) | <0.01 |

| Smoking | 0.29 | |||

| Current smoker | 1,253 (21.0) | 311 (20.1) | 942 (21.3) | |

| Ex-smoker | 915 (15.3) | 225 (14.6) | 690 (15.6) | |

| Medication | ||||

| Antithrombotic therapy | 0.44 | |||

| Anticoagulant | 149 (2.5) | 39 (2.5) | 110 (2.5) | |

| Antiplatelet | 1,462 (24.5) | 372 (24.1) | 1,090 (24.7) | |

| Both | 60 (1.0) | 14 (0.9) | 46 (1.0) | |

| Statin | 893 (15.0) | 210 (13.6) | 683 (15.5) | 0.08 |

Values are presented as number (%).

BAD, branch atheromatous disease; LI, lacunar infarction.

Table 2.

Clinical data of the study participants

| Parameter | Total (n=5,966) | BAD group (n=1,545) | LI group (n=4,421) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular territory | <0.01 | |||

| Internal carotid artery (anterior chroidal arterya)) | 142 (2.4) | 34 (2.2) | 108 (2.4) | |

| Middle cerebral artery (lenticulostriate arterya)) | 2,788 (46.7) | 877 (56.8) | 1,911 (43.2) | |

| Anterior cerebral artery (Heubner arterya)) | 56 (0.9) | 12 (0.8) | 44 (1.0) | |

| Basilar artery (paramedian pontine arterya)) | 1,011 (17.0) | 379 (24.5) | 632 (14.3) | |

| Posterior cerebral artery (Thalamoperforating arterya)) | 274 (4.6) | 24 (1.5) | 250 (5.7) | |

| Other | 781 (13.1) | 119 (7.7) | 662 (15.0) | |

| Unknown | 914 (15.3) | 100 (6.5) | 814 (18.4) | |

| Consciousness (JCS) | <0.01 | |||

| One digit | 5,847 (98.1) | 1,502 (97.2) | 4,345 (98.4) | |

| Two digits | 96 (1.6) | 39 (2.5) | 57 (1.3) | |

| Three digits | 20 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 16 (0.4) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.1) |

Values are presented as number (%).

BAD, branch atheromatous disease; LI, lacunar infarction; JCS, Japan Coma Scale.

The vessel of responsibility assumed to be applicable in the case of BAD.

Table 2 shows the clinical data including parent vascular territories in each group. Vascular territories were more common with middle cerebral artery (46.7%), 877 (56.8%) in the BAD group and 1,911 (43.2%) in the LI group. Table 3 shows medical treatment in the acute phase. Overall, tissue plasminogen activator was administered to 102 patients (1.7%), with 47 patients (3.0%) in the BAD group. Argatroban was administered in 790 cases (51.5%) in the BAD group and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) was taken in 638 cases (41.3%) in the BAD group.

Table 3.

Medical treatment in the acute phase

| Medical treatment | Total (n=5,966) | BAD group (n=1,545) | LI group (n=4,421) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue plasminogen activator | 102 (1.7) | 47 (3.0) | 55 (1.2) | <0.01 |

| Anticoagulation therapy | ||||

| Argatroban | 1,606 (26.9) | 790 (51.1) | 816 (18.5) | <0.01 |

| Heparin | 368 (6.2) | 143 (9.3) | 225 (5.1) | <0.01 |

| Warfarin | 107 (1.8) | 23 (1.5) | 84 (1.9) | 0.29 |

| Direct oral anticoagulant | 206 (3.5) | 55 (3.6) | 151 (3.4) | 0.79 |

| Antiplatelet therapy | ||||

| Ozagrel | 3,247 (54.4) | 556 (36.0) | 2,691 (60.9) | <0.01 |

| Oral antiplatelet therapy | <0.01 | |||

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 3,418 (57.3) | 751 (48.6) | 2,667 (60.3) | |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 1,837 (30.8) | 638 (41.3) | 1,199 (27.1) |

Values are presented as number (%).

BAD, Branch atheromatous disease; LI, Lacunar infarction.

Outcome

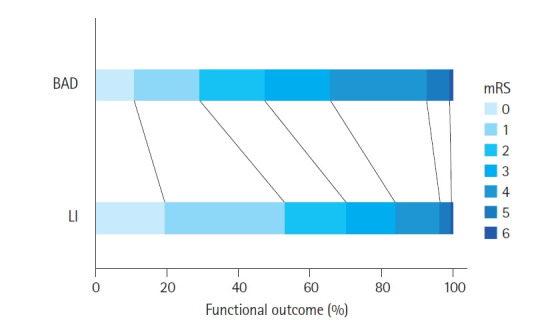

The overall poor functional outcome at discharge was 2,130 (35.7%), and the median length of a hospital stay was 14 days (interquartile range [IQR], 9–23 days). The distribution of outcomes in each group is shown in Table 4. A comparison of the percentage of mRS 0 to 6 at discharge in each group is shown in Fig. 2. BAD was associated with worse functional outcomes, with an aOR of 2.77 (95% CI, 2.42–3.17) compared to LI, indicating a higher likelihood of poor functional outcome (mRS score of 3–6) at discharge. The median hospital stay for BAD patients was 19 days (IQR, 11–29 days) compared to 13 days (IQR, 9–21 days) for LI patients, with a P-value of <0.01.

Table 4.

Outcome data of BAD and LI groups

| Outcome | Total (n=5,966) | BAD group (n=1,545) | LI group (n=4,421) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor functional outcome | 2,130 (35.7) | 812 (52.6) | 1,318 (29.8) | <0.01 |

| Length of hospital stay (day) | 14 (9–23) | 19 (11–29) | 13 (9–21) | <0.01 |

Values are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

BAD, branch atheromatous disease; LI, lacunar infarction.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of functional outcome at discharge for each group. BAD, branch atheromatous disease; LI, lacunar infarction; mRS, modified Rankin Scale.

DISCUSSION

Key observations

In this nationwide multicenter registry analysis, a comparison between BAD and LI patients revealed that BAD was associated with poorer functional outcomes and longer hospital stays. A trend towards intensive treatment of BAD with argatroban and DAPT also was observed in Japan.

Strengths of this study

This study had several advantages over previous investigations. First, its novelty lies in characterizing the epidemiology of BAD and the association of BAD with functional prognosis. While BAD was previously recognized to cause progressive paralysis, its prognosis, even with detailed adjustment for confounders, has rarely been discussed [5,13]. Although progress has been made in recent years in large-scale data studies using insurance databases, BAD is not typically classified under the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems code. In addition, regional differences in cases between Asia and Western countries also may be a reason for the lack of such comprehensive epidemiological information [2]. Therefore, the use of a specialized registry as in the current study may be important [18]. We consider the clear association between BAD and prognosis, demonstrated even after adjusting for potential confounders in this study’s sample size, to be a key epidemiological finding. Second, we elucidated the status quo of aggressive treatment of BAD in Japan. Although treatment guidelines for BAD have not been established definitively, due to the progressive nature of the disease, it has been reported that aggressive treatment with not only tissue plasminogen activator but also multiple drugs is beneficial [10,19,20]. In this database, multidrug therapy combining argatroban and DAPT was administered more frequently compared to the LI group, reflecting the above reports. BAD was considered to result from an atherothrombotic mechanism at the branch vessel. Given its pathogenesis, antiplatelet agents are the initial treatment, and early multimodal use of antiplatelet agents has been reported to be effective [10]. In summary, this study adds to the epidemiological information on BAD and clarifies the reality of treatment in Japan, but further research is needed to determine whether aggressive treatment is effective.

Interpretation

The prognostic impact observed in the results of this study may be reasonably attributed to the extent of early paralysis and early neurological deterioration, as previously reported [2,13]. In BAD, a relatively large-diameter (700–800 μm) perforating artery is stenosed or occluded by an atheromatous lesion near the orifice of the parent artery, resulting in infarction of the entire perforating artery. As an indicator of its pathology, it has been reported that hyperintense lesions identified on diffusion-weighted MRI gradually enlarge and show progressive motor deficits [21]. Early neurological deterioration is associated with a poor prognosis, and we postulate that the clinical nature of BAD as such contributes to its poor prognosis [22].

Clinical implications

The findings of this study may be useful in detecting and diagnosing BAD and predicting prognosis. In particular, they emphasize the importance of identifying and suspecting LI at an early stage in the emergency department and linking the patient to a stroke specialist, with subsequent accurate diagnosis and prognosis. Emergency departments receive a large number of stroke patients, more than 70% of whom have ischemic stroke, suggesting that the number of potential BAD patients is large [23]. No clear trend was observed between BAD and LI in patient demographics, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies [7]. This emphasizes the need for greater emphasis on a radiographic approach in the identification of BAD, and early referral to a stroke specialist is desirable. Information on the prognosis of BAD may be useful in explaining the prognosis to patients and their families after diagnosis. The longer duration of treatment and poorer functional prognosis for BAD compared to LI may assist health care providers in treatment planning, including rehabilitation.

The present results also suggest the need for intensification of treatment strategies. Although there is no clear evidence that intensified antithrombotic therapy improves the prognosis of BAD, the progressive nature and high risk of BAD may justify early consideration of intensified antithrombotic therapy. Therefore, we believe that establishing a treatment protocol that includes multiple agents is critical to improving the quality of care in the emergency department and subsequent stroke specialist consultation.

Limitations

The present study had several limitations, including the lack of initial US National Institutes of Health (NIH) Stroke Scale data, potential diagnostic discrepancies among institutions, and the limited generalizability due to the predominantly Asian population. First, because the NIH Stroke Scale was not included in this database, it is impossible to measure the extent to which initial neurological severity, apart from level of consciousness, influences prognosis. Second, there were concerns about the external validity of the study results for global application because BAD is thought to be more common in the Asian population. Third, there is the possibility of selection bias. Although there is some consensus on the diagnosis of BAD, as described in the Methods section, there was not a fully standardized and elaborated diagnostic protocol in this study. It is possible that some difficult-to-define cases were diagnosed differently between institutions. There may also have been a small number of cases in which the disease progressed to the point where the patient was retrospectively judged to have BAD. This raises concerns about selection bias. However, because Japan has the largest number of MRIs in the world and because diagnostic imaging is homogenized in Japan, we do not believe that there is a significant effect.

In conclusion, BAD presented worse functional outcomes and longer hospital stays than LI, indicating the need for early treatment and tailored rehabilitation plans to improve outcomes.

Capsule Summary

What is already known

Branch atheromatous disease (BAD) is a common form of ischemic stroke in the Asian region and, unlike lacunar infarction (LI), is known for its progressive nature. The functional prognosis of BAD compared to LI has not been clarified in large cohorts.

What is new in the current study

This large-scale multicenter study demonstrates that BAD is associated with worse functional outcomes and longer hospital stays compared to LI. Aggressive treatment strategies are more commonly used in BAD patients in Japan.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: GF; Data curation: HO, AF; Formal analysis: GF; Visualization: GF; Writing–original draft: GF; Writing–review & editing: HO, AF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

Data analyzed in this study are available from Saiseikai Research group; there are restrictions to the availability of these data, which were used under license for current study, and so are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the Saiseikai Stroke Research Group for clinical data collection.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material is available at https://doi.org/10.15441/ceem.24.220.

Explanation of the Saiseikai Stroke Database.

JCS scoring

JCS to GCS conversion

REFERENCES

- 1.Ding Q, Liu S, Yao Y, Liu H, Cai T, Han L. Global, regional, and national burden of ischemic stroke, 1990-2019. Neurology. 2022;98:e279–90. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrone L, Nannoni S, Del Bene A, Palumbo V, Inzitari D. Branch atheromatous disease: a clinically meaningful, yet unproven concept. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;41:87–95. doi: 10.1159/000442577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan LR. Intracranial branch atheromatous disease: a neglected, understudied, and underused concept. Neurology. 1989;39:1246–50. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakase T, Yoshioka S, Sasaki M, Suzuki A. Clinical evaluation of lacunar infarction and branch atheromatous disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:406–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakase T, Yamamoto Y, Takagi M, Japan Branch Atheromatous Disease Registry Collaborators The impact of diagnosing branch atheromatous disease for predicting prognosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24:2423–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deguchi I, Hayashi T, Kato Y, et al. Treatment outcomes of tissue plasminogen activator infusion for branch atheromatous disease. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:e168–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niimi M, Abo M, Miyano S, Sasaki N, Hara T, Yamada N. Comparison of functional outcome between lacunar infarction and branch atheromatous disease in lenticulostriate artery territory. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:2271–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokuda K, Hanada K, Takebayashi T, Koyama T, Fujita T, Okita Y. Factors associated with prognosis of upper limb function in branch atheromatous disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2022;218:107267. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2022.107267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwan MW, Mak W, Cheung RT, Ho SL. Ischemic stroke related to intracranial branch atheromatous disease and comparison with large and small artery diseases. J Neurol Sci. 2011;303:80–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamamoto Y, Nagakane Y, Makino M, et al. Aggressive antiplatelet treatment for acute branch atheromatous disease type infarcts: a 12-year prospective study. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:E8. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara G, Oka H, Fujii A. In-hospital recurrence and functional outcome between ischemic stroke caused by intracranial arterial dissection and intracranial atherosclerosis: retrospective cohort study of the nationwide multicenter registry. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023;32:107212. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2023.107212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. TOAST. Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto Y, Ohara T, Hamanaka M, Hosomi A, Tamura A, Akiguchi I. Characteristics of intracranial branch atheromatous disease and its association with progressive motor deficits. J Neurol Sci. 2011;304:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shigematsu K, Nakano H, Watanabe Y. The eye response test alone is sufficient to predict stroke outcome: reintroduction of Japan Coma Scale. A cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002736. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohta T, Waga S, Handa W, Saito I, Takeuchi K. New grading of level of disordered consiousness (author's transl) No Shinkei Geka. 1974;2:623–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima M, Okada Y, Sonoo T, Goto T. Development and validation of a novel method for converting the Japan Coma Scale to Glasgow Coma Scale. J Epidemiol. 2023;33:531–5. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20220147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada Y, Kiguchi T, Iiduka R, Ishii W, Iwami T, Koike K. Association between the Japan Coma Scale scores at the scene of injury and in-hospital outcomes in trauma patients: an analysis from the nationwide trauma database in Japan. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e029706. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada T, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, et al. Ozagrel for patients with noncardioembolic ischemic stroke: a propensity score-matched analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:2828–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura T, Tucker A, Sugimura T, et al. Ultra-early combination antiplatelet therapy with cilostazol for the prevention of branch atheromatous disease: a multicenter prospective study. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2016;6:84–95. doi: 10.1159/000450835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, Liu Y, Nie C, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous thrombolysis on acute branch atheromatous disease: a retrospective case-control study. Front Neurol. 2020;11:581. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terai S, Hori T, Miake S, Tamaki K, Saishoji A. Mechanism in progressive lacunar infarction: a case report with magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:255–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyamoto N, Tanaka Y, Ueno Y, et al. Demographic, clinical, and radiologic predictors of neurologic deterioration in patients with acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:205–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SE, Kim HJ, Ro YS. Epidemiology of stroke in emergency departments: a report from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of Korea, 2018-2022. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2023;10:S48–54. doi: 10.15441/ceem.23.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Explanation of the Saiseikai Stroke Database.

JCS scoring

JCS to GCS conversion