Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

What is the composition of currently available commercial human embryo culture media provided by seven suppliers, for each stage of human preimplantation embryo development?

SUMMARY ANSWER

While common trends existed across brands, distinct differences in composition underlined the absence of a clear standard for human embryo culture medium formulation.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

The reluctance of manufacturers to fully disclose the composition of their human embryo culture media generates uncertainty regarding the culture conditions that are used for human preimplantation embryo culture. The critical role of the embryo culture environment is well-recognized, with proven effects on IVF success rates and child outcomes, such as birth weight. The lack of comprehensive composition details restricts research efforts crucial for enhancing our understanding of its impacts on these outcomes. The ongoing demand for greater transparency remains unmet, highlighting a significant barrier in embryo culture medium optimization.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

For this study, 47 different human embryo culture media and protein supplements were purchased between December 2019 and June 2020; they comprise complete media (n = 23), unsupplemented media (n = 14), and supplements (n = 10). Unsupplemented media were supplemented with each available supplement from the same brand (n = 33 combinations). All samples were directly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until composition analysis.

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

We determined the concentrations of 40 components in all samples collected (n = 80). Seven electrolytes (calcium, chloride, iron, magnesium, phosphate, potassium, sodium), glucose, immunoglobulins A, G, and M (IgA, IgG, IgM), uric acid, alanine aminotransferase (ALAT), aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT), and albumin, as well as the total protein concentration, were determined in each sample using a Cobas 8000 Analyser (Roche Diagnostics). Analysis of pyruvate, lactate, carnitine, and 21 amino acids was achieved with Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS).

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Our analysis showed that generally, the concentrations of components of ready-to-use human embryo culture media align with established assumptions about the changing needs of an embryo during early development. For instance, glucose concentrations displayed a high-low-high pattern in sequential media systems from all brands: 2.5–3 mM in most fertilization media, 0.5 mM or below in all cleavage stage media, and 2.5–3.3 mM in most blastocyst stage media. Continuous media generally resembled glucose concentrations of cleavage stage media. However, for other components, such as lactate, glycine, and potassium, we observed clear differences in medium composition across different brands. No two embryo culture media compositions were the same. Remarkably, even embryo culture media from brands that belong to the same parent company differed in composition. Additionally, the scientific backing for the specific concentrations used and the differences in the composition of sequential media is quite limited and often based on minimal in vivo studies of limited sample size or studies using animal models.

LARGE SCALE DATA

N/A.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

We used a targeted approach and performed a selection of tests which limit the composition analysis to this set of analytes.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

Comprehensive disclosure and complete transparency concerning the composition of human embryo culture media, including the exact concentration of each component, are crucial for evidence-based improvements of culture media for human preimplantation embryos.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This research was supported by ZonMw (https://www.zonmw.nl/en), Programme Translational Research 2 (project number 446002003). M.G. declares an unrestricted research grant from Ferring not related to the presented work, paid to the institution VU Medical Center. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

TRIAL REGISTRATION NUMBER

N/A.

Keywords: embryo culture medium, composition, culture environment, human preimplantation embryo, IVF/ICSI

Introduction

In the early days of human IVF, preimplantation embryos were cultured in fairly simple salt solutions prepared by embryologists themselves. Nowadays, it is common to purchase more complex commercial embryo culture media from various suppliers (Chronopoulou and Harper, 2015). Although a lot remains unknown, improved understanding of the environmental and nutritional needs of embryos during the preimplantation phase has led to changes in the composition of embryo culture media to better meet those needs (Summers and Biggers, 2003; Chronopoulou and Harper, 2015). Two distinct approaches have been used to determine the needs of human preimplantation embryos and subsequently the human embryo culture media composition. One approach follows the ‘back to nature’ principle that embryo culture media should closely resemble the changing natural in vivo embryo environment (Leese, 1998). Variable concentrations of components determined in human oviduct and uterine fluid led to the development of a sequential embryo culture system (Gardner et al., 1996; Gardner, 1998), where each sequential medium provides a different nutritional environment for each stage of preimplantation embryo development. The second approach follows the ‘let the embryo choose’ principle that preimplantation embryos utilize the nutrients they need from an environment where all required nutrients for each stage are available within a tolerated range (Biggers, 1998). This concept supports the use of a single medium to provide an in vitro environment in which embryos can develop until the blastocyst stage without medium refreshment, to reduce stress. Both sequential and continuous medium systems are widely used in IVF laboratories and multiple suppliers have both types of embryo culture media available.

Clinical trials comparing human embryo culture media have demonstrated that the choice of culture medium affects IVF efficacy (Mantikou et al., 2013; Youssef et al., 2015; Kleijkers et al., 2016), as well as the foetal growth and birth weight of children conceived through IVF (Dumoulin et al., 2010; Nelissen et al., 2012; Kleijkers et al., 2016). The subsequent challenge of selecting an embryo culture medium is further complicated by uncertainties regarding the media compositions and any modifications to these compositions over time, due to the lack of transparency by manufacturers. Although an ingredient list is frequently provided, these lists are not always complete (Dyrlund et al., 2014; Tarahomi et al., 2019). Moreover, despite multiple calls for transparency, manufacturers refrain from disclosing a complete description of the composition of the embryo culture media, including the concentrations of all components, for commercial reasons (Biggers, 2000; Evers, 2016; Sunde et al., 2016; Tarahomi et al., 2019; Paulson, 2023). As a result, the exact culture conditions for human preimplantation embryos, which contribute to the birth of an estimated 1 million children every year (ESHRE 2023), remain unknown. Detailed disclosure of the concentrations of all components of commercial embryo culture media is required to facilitate evidence-based improvement of human embryo culture media, to potentially enhance IVF success rates and the health of children born after IVF.

To address this, other studies have previously measured the concentrations of various components in commercial human embryo culture media (Baltz, 2012; Morbeck et al., 2014a, 2017; Tarahomi et al., 2019) or protein supplements (Morbeck et al., 2014b). However, some of these embryo culture media were analysed without supplementation of proteins (supplements) and did therefore not represent the environment that embryo culture media normally provide to human embryos. One study that did analyse supplemented embryo culture media included four continuous media (Morbeck et al., 2017). We previously performed a composition analysis of 15 different ready-to-use commercial human embryo culture media and additionally studied the effects of culture medium storage and culture (Tarahomi et al., 2019). In the present study, the medium composition analysis has been expanded to determine the concentrations of 40 components of 56 ready-to-use commercial human embryo culture media, including both sequential media and continuous media, along with 14 unsupplemented media and 10 supplements. This study, examining 80 different culture mediums and protein supplement samples, is the most comprehensive analysis of human embryo culture medium composition to date.

Materials and methods

Commercial human embryo culture media and protein supplements

Human embryo culture media and protein supplements from 11 different brands that were commercially available in the Netherlands between December 2019 and June 2020 were purchased from seven suppliers. Embryo culture media and protein supplements that became available on the market after this period and before the publication date were not included in the analysis. We included: 23 complete human embryo culture media (supplemented by the manufacturer): G-IVF PLUS, G-1 PLUS, G-2 PLUS, G-TL (Vitrolife, Sweden), Complete Early Cleavage Medium (with Dextran Serum Supplement; DSS), Complete MultiBlast Medium (with DSS), Continuous Single Culture Medium Complete (CSCM-C), Continuous Single Culture Medium-NX Complete (CSCM-NXC) (FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, CA, USA), SAGE 1-Step HSA, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Protein Plus Fertilization, ORIGIO Universal IVF Medium, ORIGIO Sequential Fert, ORIGIO Sequential Cleav, ORIGIO Sequential Blast, Global Total LP for Fertilization, Global Total LP, EmbryoGen, BlastGen (Cooper Surgical, CA, USA), Sydney IVF Fertilization Medium, Sydney IVF Cleavage Medium, Sydney IVF Blastocyst Medium (Cook Medical, IN, USA), GM501 (Gynemed, Germany) and GAIN Complete (FertiPro, Belgium); 14 unsupplemented human embryo culture media: G-IVF, G-1, G-2 (Vitrolife, Sweden), Early Cleavage Medium, MultiBlast Medium, Continuous Single Culture Medium, Continuous Single Culture Medium-NX (FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, CA, USA), SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Fertilization Medium, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Cleavage Medium, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Blastocyst Medium, Global for Fertilization, Global (Cooper Surgical, CA, USA), IVC-TWO and IVC-THREE (InVitroCare Inc, MD, USA); and 10 protein supplements: Human Serum Albumin (HSA; Vitrolife, Sweden), recombinant human albumin supplement G-MM* (Vitrolife, Sweden), Human Serum Albumin (HSA; FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, CA, USA), Serum Substitute Supplement (SSS*; FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, CA, USA), Dextran Serum Supplement (DSS*; FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, CA, USA), SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Human Serum Albumin (HSA; Cooper Surgical, CA, USA), SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Serum Protein Substitute (SPS*; Cooper Surgical, CA, USA), LifeGlobal Human Serum Albumin (HSA; Cooper Surgical, CA, USA), Human Serum Albumin (HSA; InVitroCare Inc, MD, USA), and Human Serum Albumin (HSA; Gynemed, Germany). Although the supplements with an asterisk (*) are not CE-marked and therefore not available for clinical use in Europe, we analysed their compositions in this study.

Sample collection

Upon arrival, each complete medium (n = 23), unsupplemented medium (n = 14), and protein supplement (n = 10) was aliquoted in Eppendorf tubes, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until composition analysis. Each unsupplemented medium (same bottle) was additionally supplemented with the corresponding protein supplement(s) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then aliquoted, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C until analysis. Global for Fertilization, Global, IVC-TWO, and IVC-THREE were supplemented with two different levels of HSA. Where Cooper Surgical’s instructions for Global media did not provide explicit supplementation guidance, clarification was sought, leading to the decision to analyse Global medium with both 5% and 10% LG HSA. For InVitroCare Inc media, we opted for the highest and lowest protein supplement percentages within the recommended supplementation range: 10–12% HSA for IVC-TWO and 12–15% HSA for IVC-THREE. In total, 80 different samples of ready-to-use embryo culture media (n = 56), unsupplemented embryo culture media (n = 14), and protein supplements (n = 10) were collected.

Composition analysis

The concentration of 40 components was determined in all collected samples. Seven electrolytes (calcium (Ca2+), chloride (Cl−), iron (Fe2+/3+), potassium (K+), magnesium (Mg2+), sodium (Na+), and phosphate ()), glucose, immunoglobulins A, G, and M (IgA, IgG, and IgM), uric acid, alanine aminotransferase (ALAT), aspartate aminotransferase (ASAT), and albumin, as well as the total protein concentration, were quantified using a Cobas 8000 Analyser (Roche Diagnostics). Analysis of pyruvate, D- and L-lactate, D- and L-carnitine, and 21 amino acids (alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, citrulline, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, ornithine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, threonine, tryptophan, tyrosine, and valine) was performed with Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). All samples were thawed and prepared simultaneously for each analysis, and measurements were done by specialist technicians blinded to the names and brands of all embryo culture media and protein supplements.

Results

Concentrations of 40 components were determined in 56 samples of complete human embryo culture media (n = 23) and manually supplemented human embryo culture media (n = 33; together also referred to as ready-to-use embryo culture media) (Figs 1, 2, and 3 and Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Table S1a) and in unsupplemented human embryo culture media (n = 14) and protein supplements (n = 10) separately (Supplementary Figs S2, S3, S4, and S5 and Supplementary Table S1b and c).

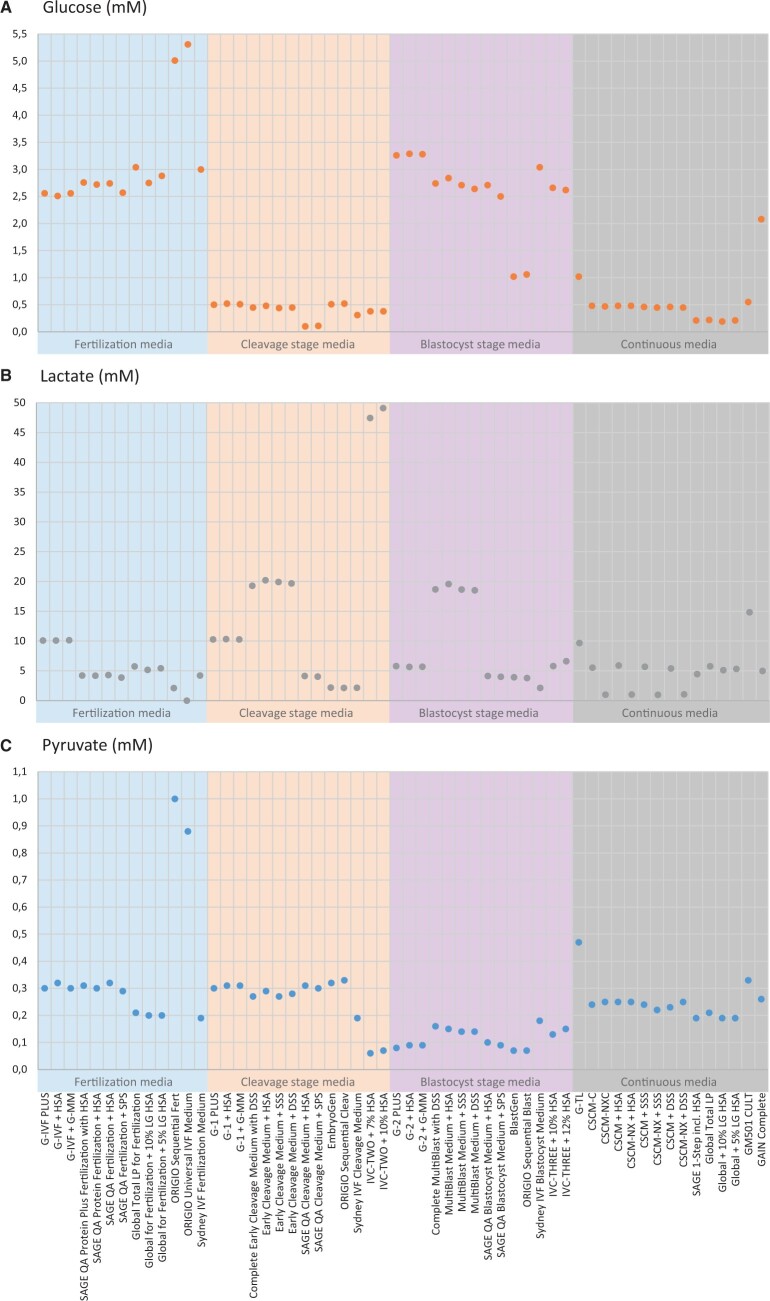

Figure 1.

Concentrations of energy sources (glucose, lactate, and pyruvate) determined in 56 ready-to-use (23 complete and 33 manually supplemented) commercial human embryo culture media. (A) Glucose concentrations in mM. (B) Lactate concentrations in mM. Early Cleavage Media and MultiBlast Media contained both isomers of lactate: L-lactate (<50%) and the metabolically dead-end and thus toxic D-lactate (>50%) (see Supplementary Table S1a). All other dots represent the concentrations of 100% L-lactate in each human embryo culture medium. (C) Pyruvate concentrations in mM.

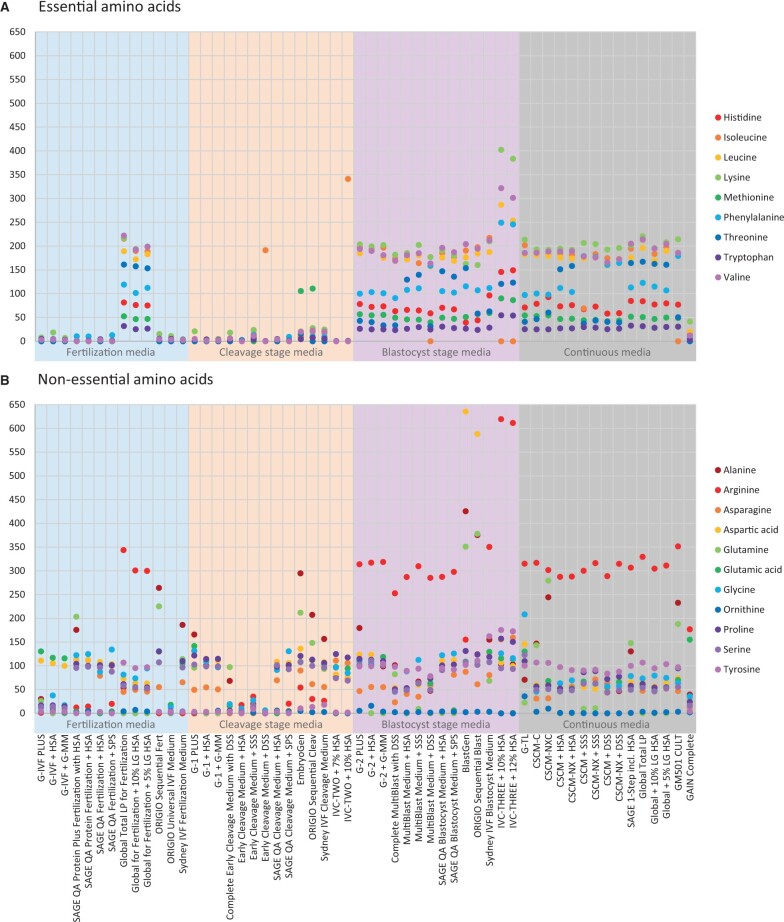

Figure 2.

Concentrations of amino acids determined in 56 ready-to-use (23 complete and 33 manually supplemented) commercial human embryo culture media. (A) Essential amino acid concentrations in μM. (B) Non-essential amino acid concentrations in μM. Citrulline was not included in this graph, as it was not detected in any of the culture media. Glycine concentrations of >3000 μM are shown in Supplementary Fig. S1B.

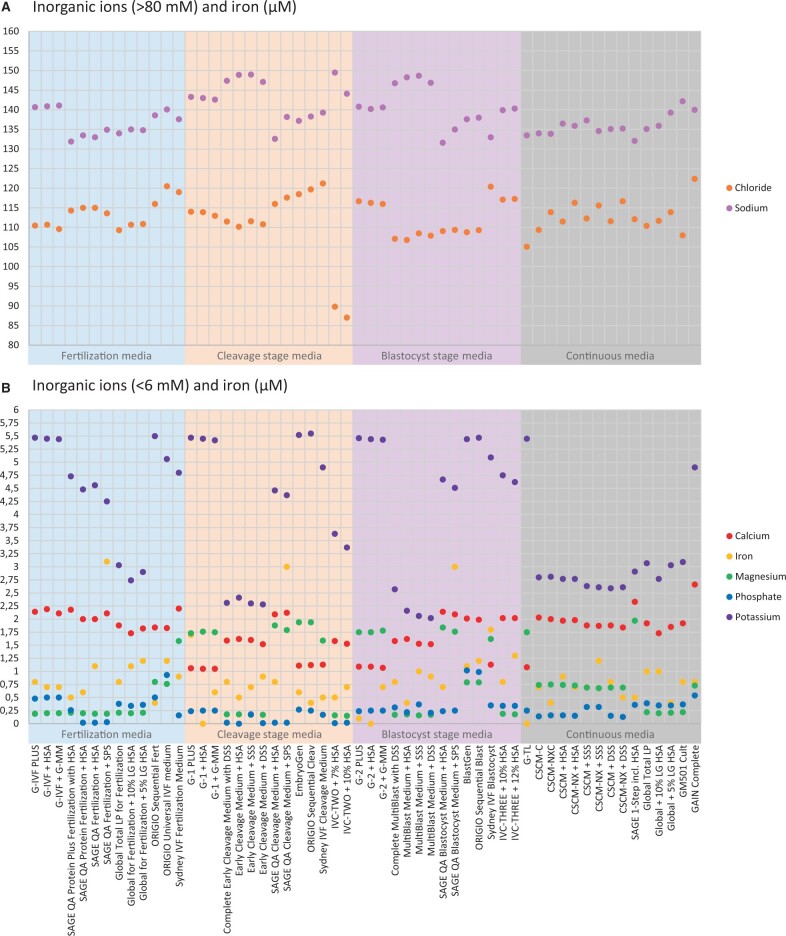

Figure 3.

Concentrations of inorganic ions (chloride, sodium, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, potassium) and iron determined in 56 ready-to-use (23 complete and 33 manually supplemented) commercial human embryo culture media. (A) Chloride and sodium concentrations (in mM) (B) Calcium, magnesium, phosphate, potassium (all in mM), and iron (in μM) concentrations.

Energy sources

Glucose was detected in all ready-to-use embryo culture media (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S1a). Glucose concentrations followed a high-low-high pattern in sequential media systems: most fertilization media contained 2.5–3.0 mM, most cleavage stage media contained only 0.5 mM or less, and most blastocyst media contained 2.5–3.3 mM. Glucose concentrations in ORIGIO media (including BlastGen) deviated from the general pattern (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S1a). Glucose concentrations in continuous media were mainly relatively low and similar to the glucose concentrations in cleavage stage media (0.5 mM or below). Three continuous media deviated from this general pattern: G-TL had a glucose concentration of 1.0 mM, GAIN Complete contained over 2.1 mM glucose, and the 0.2 mM glucose in SAGE-1-Step was higher compared to SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Cleavage Medium.

Lactate (L-lactate) was detected in all ready-to-use embryo culture media, except ORIGIO Universal IVF medium (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1a). We analysed both isoforms, L- and D-lactate, and confirmed that Early Cleavage and MultiBlast media from FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific contained both L- and D-lactate, in line with our previous findings (Tarahomi et al., 2019). Overall absolute lactate concentrations, as well as lactate concentration patterns in sequential media systems, varied among embryo culture media from all brands. For example, although lactate concentrations in cleavage stage media from Vitrolife, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage, and ORIGIO were the same compared to the corresponding fertilization media, absolute lactate concentrations differed notably between these brands: 10.1 mM in G-IVF and 10.2 mM in G-1, 3.9–4.3 mM in SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Fertilization and Cleavage Media and 2.1 mM in ORIGIO Sequential Fert and Cleav. The lactate concentration was lower (5.7 mM) in G-2, similar (4.1 mM) in SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Blastocyst Medium and higher (3.8 mM) in ORIGIO Sequential Blast. ORIGIO’s EmbryoGen and BlastGen aligned with the concentrations of ORIGIO Sequential Cleav and Blast. A different pattern was seen in Sydney Sequential media: 4.2 mM lactate in Sydney Sequential Fertilization Medium, a lower lactate concentration of 2.2 mM in Sydney Sequential Cleavage Medium and a similar concentration of 2.1 mM in Sydney Sequential Blastocyst Medium. Both Early Cleavage and MultiBlast media had a relatively high lactate concentration of around 20 mM. IVC-TWO medium samples contained the highest lactate concentrations: almost 50 mM. IVC-THREE medium contained a lower concentration of ∼6 mM. Vitrolife, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage, and Global continuous media mirrored lactate concentrations of the sequential media. Additionally, FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific had a low lactate variant of CSCM(-C): CSCM-NX(C), with a lactate concentration of ∼1 mM.

Pyruvate was detected in all ready-to-use embryo culture media (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Table S1a). Most fertilization and cleavage stage media contained a pyruvate concentration between 0.2 and 0.3 mM. However, ORIGIO Sequential Fert medium and ORIGIO Universal IVF medium had a 3-fold higher pyruvate concentration of respectively 1.0 and 0.9 mM, and IVC-TWO medium had a relatively low pyruvate concentration of <0.1 mM. Blastocyst media from most medium manufacturers contained a lower pyruvate concentration of 0.1–0.2 mM. In contrast, although the pyruvate concentration in IVC-THREE medium was in the same range as other blastocyst media, it was twice as high as the relatively low pyruvate concentration in IVC-TWO medium. The concentration pyruvate in Sydney IVF Blastocyst medium remained the same compared to the fertilization and cleavage stage media. Continuous media had pyruvate concentrations similar to fertilization and cleavage stage media of the same brand (0.2–0.3 mM). The concentration pyruvate in G-TL was notably higher in comparison with other continuous media and the Vitrolife sequential media.

Carnitine was undetectable in all ready-to-use embryo culture media, except for SAGE Quinn’s Advantage sequential media supplemented with SPS, which contained >0.2 μM L-carnitine (Supplementary Fig. S1A and Supplementary Table S1a). Although L-carnitine was identified in 8 out of the 10 analysed protein supplements (Supplementary Fig. S3B and Supplementary Table S1c), only the notably higher, but still relatively low, concentration of 2.5 μM in SPS resulted in these low, but detectable carnitine levels in the ready-to-use media.

Amino acids

Although amino acid concentrations varied, a clear general pattern was found in the concentrations of 11 amino acids in almost all ready-to-use embryo culture media.

Whereas the concentrations of histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine, all essential amino acids, were zero or low in fertilization and cleavage stage media, they were present in higher levels in almost all blastocyst media (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S1a). In contrast, Global (Protein) Fertilization media showed essential amino acid concentrations that were similar to the concentrations in blastocyst stage media of other brands. IVC-THREE medium samples had consistently elevated concentrations of essential amino acids compared to blastocyst media from other brands. Most manufacturers mimicked the essential amino acid concentrations of the blastocyst media in the continuous media. Concentrations of all essential amino acids in GAIN Complete medium were lower compared to all other continuous media.

In contrast, concentrations of the non-essential amino acids in ready-to-use embryo culture media did not show a clear pattern (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S1a). Most concentrations of alanine, arginine, asparagine, aspartic acid, glutamine, glutamic acid, glycine, proline, serine, and tyrosine were roughly between 50 and 150 μM in all ready-to-use media. However, generally lower concentrations were seen in G-IVF media (≤30 μM, except glutamic acid and aspartic acid), ORIGIO Universal IVF Medium (all ≤18 μM) and Early Cleavage Medium and MultiBlast Medium (all ≤27 μM). In most continuous media, non-essential amino acid concentrations were roughly 50 μM, slightly lower than in sequential media. Exceptions were slightly higher overall concentrations in G-TL (up to 208 μM) and slightly lower overall concentrations in GAIN Complete (all ≤39 μM, except glutamic acid). Additionally, concentrations of citrulline and ornithine, two non-essential amino acids not involved in protein synthesis that we also analysed, were respectively undetected and present in concentrations close to zero in all analysed samples.

Interestingly, arginine and tyrosine concentration patterns appeared to match the general pattern of essential amino acid concentrations: low in fertilization and cleavage stage media, higher in blastocyst and continuous media. Arginine and tyrosine concentrations in Global for Fertilization media were also higher and an exception from the general pattern, in line with essential amino acid concentrations (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S1a). Also remarkably, glycine concentrations in EmbryoGen and BlastGen, ORIGIO Sequential Fert, Cleav and Blast and Sydney IVF Fertilization, Cleavage and Blastocyst Media were up to 12.5 times higher than the average glycine concentration in other embryo culture media (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S1B and Supplementary Table S1a). Furthermore, glutamine and alanine concentrations were notably higher in SAGE Quinn’s Advantage Protein Plus Fertilization with HSA, EmbryoGen and BlastGen, ORIGIO Sequential media, CSCM-C and CSCM-NXC, SAGE-1-Step incl. HSA and GM501 CULT. Interestingly, glutamine was present in 20 out of 23 complete embryo culture media with concentrations from 25 to 378 μM, where it was absent or present up to 2 μM in their manually supplemented equivalent (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S1a). Embryo culture media from FUJIFILM Irvine scientific that were manually supplemented with SSS were an exception and did contain ∼10 μM glutamine, likely resulting from the higher glutamine concentration of 100 μM in the supplement SSS (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Fig. S4B and Supplementary Table S1a and c).

Inorganic ions and iron

Calcium, chloride, iron, magnesium, phosphate, potassium, and sodium were all available in almost all ready-to-use embryo culture media (Fig. 3A and B and Supplementary Table S1a). Magnesium concentrations exhibited two different patterns in sequential media systems. Low concentrations (0.8 mM or below) were consistently maintained for all developmental stages in embryo culture media from Global, FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific, and InVitroCare Inc. Contrastingly, embryo culture media from Vitrolife, SAGE Quinn’s Advantage, and Sydney demonstrated higher magnesium concentrations in cleavage and blastocyst stage media, as well as continuous media (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Differently, ORIGIO media (including EmbryoGen and BlastGen) showed a high-low-high pattern (0.8 mM in the fertilization stage, 1.9 in the cleavage stage, 0.8 in the blastocyst stage). In continuous media, magnesium concentrations were highest in G-TL (1.8 mM) and SAGE-1-Step (2.0 mM). Potassium concentrations were generally constant in all sequential and continuous media from the same brand, but clearly varied in absolute concentrations between brands (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Where continuous media from other brands contained a potassium concentration between 2.6 and 3.1 mM, higher concentrations were found in G-TL (5.5 mM) and GAIN Complete (3.9 mM). Calcium concentrations (1.1–2.7 mM) varied among the different brands in cleavage stage and blastocyst stage media and in continuous media (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Phosphate concentrations were 0.5 mM or below in most embryo culture media, except in ORIGIO Universal IVF medium (0.9 mM), BlastGen (1.0 mM), and ORIGIO Sequential Blast (1.0 mM) (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Iron concentrations varied between 0 and 1.8 µM in most samples, but was 3.0–3.1 µM in all SAGE Quinn’s Advantage media supplemented with SPS (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Both chloride (105.1–122.4 mM) and sodium (131.6–150.4 mM) concentrations were similar in all media from different brands, except the chloride concentrations of below 90 mM in IVC-TWO samples (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S1a).

Other components

Other components that were analysed in ready-to-use embryo culture media were uric acid and immunoglobulins IgA, IgG, and IgM, which were not detected or at a level that was almost zero, as well as albumin and total protein, which were generally a bit below 5 or 10 mM (albumin) and around 5 or 10 mM of total protein, and ALAT and ASAT, which were present in almost all samples (ALAT up to 4.3 U/l and ASAT up to 4.4 U/l) (Supplementary Table S1a–c). ALAT and ASAT were additionally analysed, since we previously found these liver enzymes to be present and affecting the composition of embryo culture media during embryo culture (Tarahomi et al., 2019).

Discussion

We determined the composition of the commercial human embryo culture media available that we could purchase in the Netherlands and provided a comprehensive report on the concentrations of 40 components in 56 ready-to-use human embryo culture media.

This study is unique in its analysis of embryo culture media for all sequential stages and the comparison with continuous media, together representing the most comprehensive analysis of ready-to-use embryo culture media composition within a single experiment. Additional analyses of unsupplemented media and protein supplements for the same components enable tracing of each components’ origin. We limited our purchase to one lot number of all embryo culture media and protein supplements. Reliability of the measurements was confirmed by semi-duplicates within our 80 samples: different samples of the same culture medium before and after supplementation with a protein supplement. Our results were also validated by partial overlap with previous studies that analysed 32–39 components in commercial embryo culture media, as the concentrations of many overlapping components are similar to those found by Morbeck et al. (2014a, 2017) and Tarahomi et al. (2019). A limitation of this study is that the embryo culture media will likely contain more components than measured in this study as we used a targeted approach. Part of the unidentified components could originate from the protein supplements added to the embryo culture media, which are the most undefined and variable ‘component’ of ready-to-use human embryo culture media (Dyrlund et al., 2014). We did not analyse the presence and concentrations of vitamins, growth factors, or anti-oxidants, some of which are expected to be present in at least some of the included embryo culture media as they are mentioned on the ingredient list of several media.

Our results showed that no two human embryo culture media were the same. Although similarities were found, the concentrations of several components varied between all embryo culture media. Importantly, current concentrations of components seem to be based on limited available evidence. Below we discuss the most notable differences in concentrations of some of the components we found in commercial human embryo culture media, with the perspective of the often limited evidence for these concentrations in the scientific literature.

Energy sources

Glucose concentrations in all cleavage stage media were ∼0.5 mM or lower, which is mirrored in continuous media and notably lower than in fertilization and blastocyst stage media (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S1a). This pattern likely originates from the observation that hamster embryos failed to develop beyond the two-cell stage in the presence of glucose and phosphate, which may have led to cautiousness in adding glucose to cleavage stage media (Yanagimachi and Chang, 1964; Schini and Bavister, 1988). Furthermore, measurements of six midcycle human oviduct fluid samples later confirmed that a low glucose concentration of 0.5 mM seems appropriate for cleavage stage culture (Gardner et al., 1996). However, experimental studies in the late nineties and early 2000s showing embryo development into blastocysts in embryo culture media with a higher glucose concentration in combination with a different medium composition, did not receive adequate attention (for review, see Summers and Biggers, 2003). Although since then, it was generally accepted that glucose concentrations do not absolutely inhibit the first cleavages of preimplantation embryos and generally discouraged to minimize glucose concentrations in cleavage stage media, medium manufacturers have continued to maintain low glucose concentrations to this day.

A recent study that also analysed midcycle human oviduct fluid (n = 21), found an average in vivo glucose concentration of ∼3.4 mM (Utsunomiya et al., 2022). Additionally, our group measured an elevated glucose concentration of 5.1 mM in 22 samples of human uterine fluid from healthy, fertile women 3 days after a positive LH test or ovum pick-up (Tarahomi et al., 2024). Although the first study included subfertile women, these findings suggest that the physiological glucose concentration is comparable to or higher than commonly present in fertilization and blastocyst stage media and that lower glucose concentrations should be considered as non-physiological. Elevating the glucose concentrations in cleavage stage and continuous media according to the in vivo evidence, requires improving the concentrations of other medium components for successful support of blastocyst development (Gardner and Lane, 1996). Particularly continuous media could significantly benefit from an effort in optimizing medium composition by aligning the glucose concentration with in vivo levels, as an adequate amount of glucose is crucial for energy provision after compaction (Gardner, 2008). All in all, the discrepancies in reported glucose concentrations in vivo and what we now found in vitro deserve more attention.

Lactate concentrations varied widely in all embryo culture media and no consistent pattern was observed across the sequential media systems from all brands (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S1a). The variation highlights the absence of a general rationale on the optimal lactate concentration in culture media for human preimplantation embryos. This is concerning, as lactate concentrations have been shown to interfere with pyruvate oxidation, the primary energy source for zygotes and cleavage stage embryos (Lane and Gardner, 2000). For example, the lactate concentration of almost 50 mM found in IVC-TWO medium may hinder embryos from effectively utilizing pyruvate for energy during the cleavage stage. In mice, a physiological lactate concentration of 5 mM or below appeared to be acceptable, as pyruvate uptake in mouse cleavage stage embryos was shown to be maintained (Lane and Gardner, 2000). Although the physiological lactate concentration in human oviducts was long considered to be around 10.5 mM based on analysis of six samples of midcycle human oviduct fluid (Gardner et al., 1996), a recent study found a lower lactate concentration of 5.1 mM in midcycle oviduct fluid from 21 women, supporting a lactate concentration of around 5 mM in cleavage stage media (Utsunomiya et al., 2022). Additionally, our group found a lactate concentration of 6.6 mM in 22 samples of human uterine fluid 3 days after a positive LH test or ovum pick-up (Tarahomi et al., 2024). These recent in vivo findings suggest that a lactate concentration in the range of 5–7 mM would be considerable for human preimplantation embryos until the blastocyst stage. However, metabolic balance is suggested to depend on the ratio between lactate concentration and pyruvate concentration, rather than absolute concentrations alone (Morbeck et al., 2014a). Furthermore, where all other embryo culture media specifically contained L-lactate, over 50% of the total lactate measured in Early Cleavage and MultiBlast media from FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific was identified as the metabolically dead-end and thus toxic D-lactate, as was also identified by us previously (Tarahomi et al., 2019). Interestingly, between ordering the media and publication of this study, Early Cleavage and MultiBlast medium have been taken off the market and FUJIFILM Irvine Scientific now only provides continuous media: CSCM(-C) and low lactate media CSCM-NX(C).

Pyruvate concentrations show a trend with higher concentrations in fertilization media and cleavage stage media (both 0.2–0.3 mM), and lower concentrations in blastocyst stage media (roughly around 0.1 mM) from most brands (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Table S1a). To a certain extent, these concentrations resemble the concentrations found in midcycle human oviduct fluid (0.32 mM; n = 6) and human uterine fluid throughout the menstrual cycle (0.10 mM; n = 15) (Gardner et al., 1996). More recent in vivo analyses determined pyruvate concentrations of 0.209 mM in midcycle oviduct fluid (n = 21) and 0.106 mM in the luteal phase (n = 28) (Utsunomiya et al., 2022), and 0.08 mM in human uterine fluid (n = 22) (Tarahomi et al., 2024). The lower pyruvate concentrations in most blastocyst media compared to fertilization and cleavage stage media align with the general idea that pyruvate is the preferred energy source for preimplantation embryos until embryonic genome activation or the blastocyst stage (Gardner, 2008). In contrast, the consistent pyruvate concentrations in Sydney IVF sequential media align with the suggestion that pyruvate uptake by preimplantation embryos remains constant, even in the blastocyst stage, and dependent on the medium composition particularly the lactate concentration in the medium (Lane and Gardner, 2000; Lee et al., 2022). The rationale for the elevated pyruvate concentrations in ORIGIO fertilization media and continuous medium G-TL is unclear.

The optimal ratio of lactate to pyruvate concentrations in the human preimplantation embryo environment is unknown. In blood, a lactate-pyruvate ratio between 10 and 20 is considered normal. The in vivo findings from 1996 indicated lactate-pyruvate ratios of ∼33 in human oviduct fluid and 59 in human uterine fluid (Gardner et al., 1996). The more recent in vivo findings, however, suggest ratios of 25–30 in oviduct fluid and about 83 in uterine fluid (Utsunomiya et al., 2022; Tarahomi et al., 2024). In contrast, our analysis revealed a high variability in lactate-pyruvate ratios within embryo culture media, ranging from 0 to 719, confirming previous observations of high variability in lactate-pyruvate ratios in embryo culture media (Morbeck et al., 2014a). Since the lactate-pyruvate ratio in the embryo environment directly influences the metabolic activity of an embryo, affecting the amount of energy available for embryo development, further research into the lactate-pyruvate ratio is important for future culture medium development (Zander-Fox and Lane, 2012).

Carnitine was included in our analysis in light of the growing interest in carnitine as a potential component in embryo culture media due to its role in fatty acid metabolism and energy production to maintain metabolic homeostasis and its roles as scavenger of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cryoprotector (for review, see Placidi et al., 2022). Experimental studies have shown that the addition of acetyl-L-carnitine to embryo culture media improves oocyte and embryo development and cryotolerance of mouse, porcine, bovine, and human preimplantation embryos (Truong et al., 2016; Lowe et al., 2017; Truong and Gardner, 2017, 2020; Zolini et al., 2019; Gardner et al., 2020). Although carnitine was not detected in most ready-to-use embryo culture media included in this study (Supplementary Fig. S1A and Table S1A), it may be included in future versions of these media or new embryo culture media. Whether carnitine is present in human oviduct and uterine fluid is unknown.

Amino acids

Essential amino acids were absent or present at low concentrations in fertilization and cleavage stage media, but consistently appeared in higher concentrations in blastocyst and continuous media from most brands (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S1a). In contrast, non-essential amino acids were generally present, but varied in their absolute concentrations among the different types of embryo culture media and brands (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S1a). These patterns may reflect the findings from an experimental study showing that mouse embryo development and viability are greatest in the consistent presence of non-essential amino acids and glutamine and when essential amino acids are exclusively added after the eight-cell stage (Lane and Gardner, 1997). The contrasting presence of essential amino acids in Global for Fertilization media may be influenced by another experimental study with mouse embryos suggesting that zygotes have enhanced developmental potential when produced in mKSOM supplemented with 19 amino acids (Summers et al., 2000). In vivo studies showed that both essential and non-essential amino acids are present in midcycle human oviduct and uterine fluid (Kermack et al., 2015; Utsunomiya et al., 2022). However, absolute concentrations of both essential amino acids and non-essential amino acids in these in vivo fluids differ from the concentrations measured in the embryo culture media. The in vivo evidence suggests that the absence or low concentrations of essential amino acids in media for the early stages of human embryo culture are non-physiological and might represent an adaptation to support human embryo development in vitro in a suboptimal medium composition.

Glycine concentrations in three sequential media systems were markedly higher than in all other embryo culture media and exceeded 3000 μM (Supplementary Fig. S1B and Supplementary Table S1a). Elevation of these glycine concentrations could be attributed to its role as an organic osmolyte, although a concentration of 1000 μM glycine was earlier found to be maximally effective for mouse preimplantation embryos (Baltz, 2012). This was supported by enhanced development of early- and late-stage bovine embryos in the presence of 1100 μM glycine (Herrick et al., 2016). Interestingly, the physiological glycine concentration in (early luteal phase) human uterine fluid was also found to be around 1000 μM (Kermack et al., 2015; Tarahomi et al., 2024) and the average glycine concentration in 21 samples of midcycle oviduct fluid was demonstrated to be 462 μM (Utsunomiya et al., 2022). Given that the in vivo glycine concentration appears to be around 1000 μM in human uterine fluid and is notably higher in human oviduct fluid than in most human embryo culture media, and considering that 1000 μM is the optimal glycine concentration for mouse and bovine embryos, investigating the effect of increasing the glycine concentration up to 1000 μM in human embryo culture media might be of interest.

The reasons for substantial glutamine concentration discrepancies between complete embryo culture media, in which the concentration is notably high, and the same media after manual supplementation, in which glutamine is generally absent, remain unclear (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S1a). In vivo studies reported different glutamine concentrations: 130 μM in midcycle human oviduct fluid (n = 21), 426 μM in human uterine fluid throughout the cycle (n = 56) and 227 μM in early luteal human uterine fluid (n = 22) (Kermack et al., 2015; Utsunomiya et al., 2022; Tarahomi et al., 2024). Glutamine’s potential benefits for embryo development are linked to its roles as organic osmolyte or an extra carbon source for preimplantation embryos. The presence of 1000 μM glutamine was found to be optimal in overcoming the 2-cell block in mouse embryos (Chatot et al., 1989; Lawitts and Biggers, 1992), and that concentration was later applied in potassium simplex optimization medium (KSOM) and Vitrolife sequential media (Summers and Biggers, 2003). However, free glutamine then appeared to be detrimental for embryo development due to ammonium accumulation (Lane and Gardner, 1994), resulting in the addition of a stable dimer of alanyl- or glycyl-L-glutamine to embryo culture media to prevent this quick ammonium build-up (Lane et al., 2001). Elevated alanine concentrations in conjunction with higher glutamine concentrations suggest the addition of alanyl-L-glutamine to the complete embryo culture media included in our analysis.

Inorganic ions and iron

The concentrations of inorganic ions determined in the embryo culture media were similar to the findings of Morbeck et al. (2014a, 2017) and Tarahomi et al. (2019). The biggest differences in concentrations of these ions were seen for calcium, magnesium, and potassium (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S1a). Calcium concentrations (1.1–2.7 mM) and magnesium concentrations (0.2–2.0 mM) identified in the embryo culture media are comparable to the average concentrations found in midcycle to luteal phase human oviduct fluid: in midcycle 1.3 mM calcium (n = 21) and in luteal phase 1.1 mM calcium (n = 21) and 1.1 mM calcium (n = 7), and in midcycle 0.5 mM magnesium (n = 21) and in luteal phase 0.6 mM magnesium (n = 21) and 1.4 mM magnesium (n = 7) (Borland et al., 1980; Utsunomiya et al., 2022). Potassium concentrations in all embryo culture media did not match the average concentrations determined in midcycle luteal phase human oviduct fluid (midcycle 15.8 mM (n = 21), luteal phase 15.8 mM (n = 21) and 21.2 mM (n = 7)) (Borland et al., 1980; Utsunomiya et al., 2022). An experimental mouse embryo study suggested that a potassium concentration of 25 mM, which is comparable to the 26.5 mM identified in proestrous mouse ampullary fluid (Borland et al., 1977), is optimal for mouse embryo culture as this concentration led to the best embryo development and highest implantation rate. However, a concentration of 10 mM, closer to proestrous mouse uterine fluid concentrations (14.1 mM), seemed to better support blastocyst formation (Roblero and Riffo, 1986). Global media contained potassium concentrations comparable to the concentration in KSOM (2.5 mM) (Erbach et al., 1994). Research on the effect of resembling a physiological potassium concentration in culture media for human embryo culture seems warranted, as evidence for the low potassium concentrations in human embryo culture media is absent. For further discussion of the concentrations of calcium, magnesium, and potassium in commercial embryo culture media, we refer to Morbeck et al. (2017).

Iron concentrations were highest in media supplemented with SPS, similar to previous measurements (Morbeck et al., 2014b). We did not analyse other metals that are known to be present in embryo culture media, like aluminium, chromium, and manganese (Morbeck et al., 2014a).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has highlighted the persistent uncertainty about the optimal composition of culture media for human preimplantation embryos. This was illustrated by the fact that none of the embryo culture media from different manufacturers were identical. In fact, one supplier, Cooper surgical, offers embryo culture media from four different brands with significantly different compositions. If the ideal composition were known, marketing multiple embryo culture media with varying compositions by a single supplier would seem inconceivable. Despite shared trends among various embryo culture media, the current compositions of commercial embryo culture media appear to be based on limited available evidence. Further research aimed at elucidating the natural in vivo environment of human preimplantation embryos may provide critical insights for optimization of the composition of culture media for in vitro culture of human preimplantation embryos. Outcomes of this type of research have the potential to enhance IVF success rates and improve child health outcomes after IVF. Complete disclosure of the current compositions of commercial human embryo culture media by manufacturers, along with ongoing transparency in the development and improvement of these media, is essential for safe and effective optimization of the in vitro environment of human preimplantation embryos.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

M S Zagers, Center for Reproductive Medicine, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

M Laverde, Center for Reproductive Medicine, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

M Goddijn, Center for Reproductive Medicine, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

J J de Groot, Laboratory General Clinical Chemistry, Department of Clinical Chemistry, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

F A P Schrauwen, Laboratory General Clinical Chemistry, Department of Clinical Chemistry, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

F M Vaz, Laboratory Genetic Metabolic Diseases, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pediatrics, Emma Children’s Hospital, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Gastroenterology Endocrinology Metabolism, Inborn Errors of Metabolism, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Core Facility Metabolomics, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

S Mastenbroek, Center for Reproductive Medicine, Amsterdam UMC Location University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in the online supplementary material.

Authors’ roles

M.S.Z. and S.M. conceived and designed the study. M.S.Z. collected all samples. J.J.d.G., F.A.P.S., and F.M.V. performed the analyses. M.S.Z. interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the publication of the latest version.

Funding

This research was funded by ZonMw (https://www.zonmw.nl/en), Programme Translational Research 2 (project number 446002003).

Conflict of interest

M.G. declares an unrestricted research grant from Ferring not related to the presented work, paid to the institution VU Medical Center. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Baltz JM. Media composition: salts and osmolality. Methods Mol Biol 2012;912:61–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggers JD. Reflections on the culture of the preimplantation embryo. Int J Dev Biol 1998;42:879–884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggers JD. Ethical issues and the commercialization of embryo culture media. Reprod Biomed Online 2000;1:74–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland RM, Biggers JD, Lechene CP, Taymor ML. Elemental composition of fluid in the human fallopian tube. J Reprod Fertil 1980;58:479–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borland RM, Hazra S, Biggers JD, Lechene CP. The elemental composition of the environments of the gametes and preimplantation embryo during the initiation of pregnancy. Biol Reprod 1977;16:147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatot CL, Ziomek CA, Bavister BD, Lewis JL, Torres I. An improved culture medium supports development of random-bred 1-cell mouse embryos in vitro. J Reprod Fertil 1989;86:679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronopoulou E, Harper JC. IVF culture media: past, present and future. Hum Reprod Update 2015;21:39–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumoulin JC, Land JA, Van Montfoort AP, Nelissen EC, Coonen E, Derhaag JG, Schreurs IL, Dunselman GA, Kester AD, Geraedts JP et al. Effect of in vitro culture of human embryos on birthweight of newborns. Hum Reprod 2010;25:605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrlund TF, Kirkegaard K, Poulsen ET, Sanggaard KW, Hindkjær JJ, Kjems J, Enghild JJ, Ingerslev HJ. Unconditioned commercial embryo culture media contain a large variety of non-declared proteins: a comprehensive proteomics analysis. Hum Reprod 2014;29:2421–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbach GT, Lawitts JA, Papaioannou VE, Biggers JD. Differential growth of the mouse preimplantation embryo in chemically defined media. Biol Reprod 1994;50:1027–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESHRE. ART Fact Sheet. 2023. https://www.eshre.eu/Europe/Factsheets-and-infographics (1 February 2024, date last accessed).

- Evers JL. Peanut butter. Hum Reprod 2016;0:1–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK. Changes in requirements and utilization of nutrients during mammalian preimplantation embryo development and their significance in embryo culture. Theriogenology 1998;49:83–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK. Dissection of culture media for embryos: the most important and less important components and characteristics. Reprod Fertil Dev 2008;20:9–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Kuramoto T, Tanaka M, Mitzumoto S, Montag M, Yoshida A. Prospective randomized multicentre comparison on sibling oocytes comparing G-Series media system with antioxidants versus standard G-Series media system. Reprod Biomed Online 2020;40:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Lane M. Alleviation of the ‘2-cell block’ and development to the blastocyst of CF1 mouse embryos: role of amino acids, EDTA and physical parameters. Hum Reprod 1996;11:2703–2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Lane M, Calderon I, Leeton J. Environment of the preimplantation human embryo in vivo: metabolite analysis of oviduct and uterine fluids and metabolism of cumulus cells. Fertil Steril 1996;65:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick JR, Lyons SM, Greene AF, Broeckling CD, Schoolcraft WB, Krisher RL. Direct and osmolarity-dependent effects of glycine on preimplantation bovine embryos. PLoS One 2016;11:e0159581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermack AJ, Finn-Sell S, Cheong YC, Brook N, Eckert JJ, Macklon NS, Houghton FD. Amino acid composition of human uterine fluid: association with age, lifestyle and gynaecological pathology. Hum Reprod 2015;30:917–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleijkers SH, Mantikou E, Slappendel E, Consten D, van Echten-Arends J, Wetzels AM, van Wely M, Smits LJ, van Montfoort AP, Repping S et al. Influence of embryo culture medium (G5 and HTF) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome after IVF: a multicenter RCT. Hum Reprod 2016;31:2219–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M, Gardner DK. Increase in postimplantation development of cultured mouse embryos by amino acids and induction of fetal retardation and exencephaly by ammonium ions. J Reprod Fertil 1994;102:305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M, Gardner DK. Differential regulation of mouse embryo development and viability by amino acids. J Reprod Fertil 1997;109:153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M, Gardner DK. Lactate regulates pyruvate uptake and metabolism in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Biol Reprod 2000;62:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane M, Hooper K, Gardner DK. Effect of essential amino acids on mouse embryo viability and ammonium production. J Assist Reprod Genet 2001;18:519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawitts JA, Biggers JD. Joint effects of sodium chloride, glutamine, and glucose in mouse preimplantation embryo culture media. Mol Reprod Dev 1992;31:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Liu X, Jimenez-Morales D, Rinaudo PF. Murine blastocysts generated by in vitro fertilization show increased Warburg metabolism and altered lactate production. Elife 2022;11:e79153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leese HJ. Human embryo culture: back to nature. J Assist Reprod Genet 1998;15:466–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe JL, Bartolac LK, Bathgate R, Grupen CG. Supplementation of culture medium with L-carnitine improves the development and cryotolerance of in vitro-produced porcine embryos. Reprod Fertil Dev 2017;29:2357–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantikou E, Youssef MA, van Wely M, van der Veen F, Al-Inany HG, Repping S, Mastenbroek S. Embryo culture media and IVF/ICSI success rates: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2013;19:210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morbeck DE, Baumann NA, Oglesbee D. Composition of single-step media used for human embryo culture. Fertil Steril 2017;107:1055–1060.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morbeck DE, Krisher RL, Herrick JR, Baumann NA, Matern D, Moyer T. Composition of commercial media used for human embryo culture. Fertil Steril 2014a;102:759–766.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morbeck DE, Paczkowski M, Fredrickson JR, Krisher RL, Hoff HS, Baumann NA, Moyer T, Matern D. Composition of protein supplements used for human embryo culture. J Assist Reprod Genet 2014b;31:1703–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen EC, Van Montfoort AP, Coonen E, Derhaag JG, Geraedts JP, Smits LJ, Land JA, Evers JL, Dumoulin JC. Further evidence that culture media affect perinatal outcome: findings after transfer of fresh and cryopreserved embryos. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1966–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson RJ. What do you mean, you don’t know what is in the culture media? F S Rep 2023;4:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Placidi M, Di Emidio G, Virmani A, D’Alfonso A, Artini PG, D’Alessandro AM, Tatone C. Carnitines as mitochondrial modulators of oocyte and embryo bioenergetics. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022;11:745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roblero LS, Riffo MD. High potassium concentration improves preimplantation development of mouse embryos in vitro. Fertil Steril 1986;45:412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schini SA, Bavister BD. Two-cell block to development of cultured hamster embryos is caused by phosphate and glucose. Biol Reprod 1988;39:1183–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MC, Biggers JD. Chemically defined media and the culture of mammalian preimplantation embryos: historical perspective and current issues. Hum Reprod Update 2003;9:557–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MC, McGinnis LK, Lawitts JA, Raffin M, Biggers JD. IVF of mouse ova in a simplex optimized medium supplemented with amino acids. Hum Reprod 2000;15:1791–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunde A, Brison D, Dumoulin J, Harper J, Lundin K, Magli MC, Van den Abbeel E, Veiga A. Time to take human embryo culture seriously. Hum Reprod 2016;31:2174–2182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarahomi M, Vaz FM, van Straalen JP, Schrauwen FAP, van Wely M, Hamer G, Repping S, Mastenbroek S. The composition of human preimplantation embryo culture media and their stability during storage and culture. Hum Reprod 2019;34:1450–1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarahomi M, Zagers MS, Zafardoust S, Mohammadzadeh A, Fathi Z, Sareban H, Fatemi F, Fakhr S, Hamer G, Repping S et al. In vivo human uterine temperature, pH, and uterine fluid composition analysis. bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.11.18.623470. 19 November 2024, preprint: not peer reviewed. [Google Scholar]

- Truong T, Gardner DK. Antioxidants improve IVF outcome and subsequent embryo development in the mouse. Hum Reprod 2017;32:2404–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong TT, Gardner DK. Antioxidants increase blastocyst cryosurvival and viability post-vitrification. Hum Reprod 2020;35:12–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong TT, Soh YM, Gardner DK. Antioxidants improve mouse preimplantation embryo development and viability. Hum Reprod 2016;31:1445–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utsunomiya T, Yao T, Itoh H, Kai Y, Kumasako Y, Setoguchi M, Nakagata N, Abe H, Ishikawa M, Kyono K et al. Creation, effects on embryo quality, and clinical outcomes of a new embryo culture medium with 31 optimized components derived from human oviduct fluid: a prospective multicenter randomized trial. Reprod Med Biol 2022;21:e12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagimachi R, Chang MC. In vitro fertilization of golden hamster ova. J Exp Zool 1964;156:361–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef MMA, Mantikou E, van Wely M, Van der Veen F, Al‐Inany HG, Repping S, Mastenbroek S; Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group. Culture media for human pre‐implantation embryos in assisted reproductive technology cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD007876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zander-Fox D, Lane M. Media composition: energy sources and metabolism. Methods Mol Biol 2012;912:81–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolini AM, Carrascal-Triana E, Ruiz de King A, Hansen PJ, Alves Torres CA, Block J. Effect of addition of L-carnitine to media for oocyte maturation and embryo culture on development and cryotolerance of bovine embryos produced in vitro. Theriogenology 2019;133:135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in the online supplementary material.