Abstract

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder diagnosed by clinicians and experts through questionnaires, observations, and interviews. Current diagnostic practices focus on social and communication impairments, which often emerge later in life. This delay in detection results in missed opportunities for early intervention. Gait, a motor behavior, has been previously shown to be aberrant in children with ASD and may be a biomarker for early detection and diagnosis of ASD. The current study assessed gait in children with ASD using a single RGB camera-based pose estimation method by MediaPipe (MP). Data from 32 children with ASD and 29 typically developing (TD) children were collected. The ASD group exhibited significantly reduced step length and right elbow° and increased right shoulder° relative to TD children. Four machine learning (ML) algorithms were employed to classify the ASD and TD children based on the statistically significant gait parameters. The binomial logistic regression (Logit) performed the best, with an accuracy of 0.82, in classifying the ASD and TD children. The present study demonstrates the use of gait analysis and ML techniques for the early detection of ASD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85348-w.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, Gait, Children, Early detection, Machine learning

Subject terms: Psychology, Human behaviour

Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by difficulties in social communication and interactions, as well as the presence of restricted and repetitive behavior1. ASD affects approximately one in every 100 children worldwide, and this prevalence is projected to increase2. The average age of ASD diagnosis ranged from 3.17 to 10 years between 1990 and 20123. However, a recent global meta-analysis indicates that the age at diagnosis has improved, ranging from 2.58 to 19.55 years from 2012 to 20194.

The diagnosis of ASD is often challenging because it relies on the clinical professionals’ expertise, who use a combination of observation, interviews, behavioral scales, and questionnaires to arrive at a diagnosis. These methods have limitations owing to their complexity, time-consuming nature, high cost, and the need for skilled interpretation5,6. As a result, the early detection and diagnosis of ASD can be delayed, leading to the loss of a critical developmental period for intervention and treatment. Early detection and diagnosis of ASD is crucial, as it has been associated with better clinical outcomes7. Moreover, taking advantage of early brain plasticity and the potential for modifiable abnormalities in reward circuitry in the brain can help prevent the full manifestation of ASD8. Therefore, it is essential to address the challenges of diagnosing ASD at an early stage and develop effective methods for early detection, diagnosis, and intervention to improve outcomes for individuals with ASD.

Despite advancements in understanding the neurological aspects of ASD, no reliable biomarkers are available for this condition9. Individuals with ASD often exhibit atypical sensory processing from sensory detection to multisensory integration10,11. As the motor system matures alongside the sensory system during brain development, the suboptimal functioning of one system can affect the other12. Aberrant sensory noise and poor multisensory integration are potential sources of atypical motor development in ASD13. Given that sensory-motor dysfunction can be considered a primary feature of ASD14, the condition may also present as a movement disorder15,16.

Motor deficits have been observed in ASD since its earliest description17. A meta-analysis shows that children and teenagers with ASD exhibit significant deviations in their motor behaviors, ranging from 21–100%18. Children with ASD often display stereotypes, atypical posture, clumsiness, coordination issues, increased joint mobility, and an unusual gait19–23. Moreover, motor impairments in children with ASD are associated with the severity of the condition and its core deficits24–26. Researchers across various fields have recognized movement and sensory disturbances as the backbone symptoms of ASD27. Therefore, motor function impairments hold promise as a potential biomarker or “putative endophenotype”28 or a “bio-behavioral marker"29 of ASD as they often manifest before social and communication deficits and occur in most individuals with ASD30,31. Additionally, motor function impairments can be objectively quantified, making them a potentially valuable diagnostic tool compared to social and communication deficits6.

The way an individual walks, known as gait, has been recently studied in ASD. It can serve as an indicator of sensory-motor development in the brain during early childhood. A child walks independently between the age of 9 and 18 months, which is the interplay of neurocognitive, locomotor, and learning factors32–36. However, research consistently reports that children with ASD exhibit impairments in kinematic gait parameters37 and standardized motor tests compared to healthy peers38,39. Specifically, they tend to walk with reduced stride length and ankle flexion angle, increased hip flexion angle, slower walking speed, and longer step time40,41. Atypical gait patterns in ASD have been described as uncoordinated and disjointed from an early age42,43, and clinicians consider it a hallmark feature of the condition44. Despite stereotyped and repetitive motor behavior being a diagnostic criterion for ASD, the current diagnostic system includes a minimal description of motor impairment1. Therefore, gait appears to be a potential phenotype and biomarker of ASD.

Various instruments have been employed in the past to measure gait in individuals with ASD15,42,43,45,46, but they have some limitations such as cost-effectiveness, restricted accessibility, requirement of a special experimental setup, and intrusive nature in terms of bodily attachments. This necessitates an alternative economic, objective, and non-intrusive computer vision (CV) based framework to study gait in ASD. Recently there has been a shift from traditional instruments, and an increasing number of researchers have been using computer vision (CV) based advances to objectively quantity the motor behaviors and gait in ASD47,48,6,].

The primary objective of this study is to objectively assess gait in children with ASD and compare it with gait in typically developing (TD) children. Such a comparison is likely to reveal differences in gait function between the two groups, providing insights into how motor impairments affect children with ASD and indicating the extent to which gait impairments might serve as a biomarker for ASD. Further, state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) algorithms could be employed to automate and assist in the early detection and diagnosis of ASD based on gait parameters.

Methods

Participants

Children with ASD were recruited from two rehabilitation centers in Kanpur, India, whereas the TD children were enrolled from schools located in the same vicinity. The study included 32 children with ASD who had a mean age of 5.97 years and 29 TD children with a mean age of 4.86 years. The mean standardized Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC) score for the ASD group was 59.19 (14.11), while the TD group had an average ABC score of 99.76 (8.37). The exclusion criteria were the known diagnosis of any neurological or genetic conditions, preterm birth, and the use of medication that affected the nervous system in the last week. The information about exclusion criteria was obtained through a screening interview conducted with each participant’s parent(s) before the actual testing took place. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur (IITK/IEC/2021-22/I/24) and the research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The written consent to participate was also obtained from the parent(s) of the children prior to the initiation of the study.

Clinical measures

Children with ASD were previously diagnosed by a consultant medical practitioner specializing in diagnosing and treating neurodevelopmental disorders. The children were enrolled in rehabilitation centers, and further diagnosis of ASD was established by a licensed clinical psychologist using the Indian Scale for the Assessment of Autism49. The Government of India has created a comprehensive assessment tool called the ISAA to evaluate ASD and determine the level of severity in such children. ISAA is made up of 40 items, which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale and grouped into six categories: Social Relationship and Reciprocity, Emotional Responsiveness, Speech-Language and Communication, Behaviour Patterns, Sensory aspects, and Cognitive Component. The total score on the ISAA ranges from 40 to 200, with lower scores indicating milder symptoms and higher scores reflecting more severe manifestations of ASD49. The ISAA scale has adequate psychometric properties, compared to the Childhood Autism Rating Scale its reliability and internal consistency were found to be satisfactory50,51.

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale-3, Comprehensive Interview Form52 (was utilized to measure adaptive behavior in ASD and TD children. This assessment tool is designed to measure adaptive behavior across various age ranges. It assesses adaptive functioning across three domains (communication, socialization, and daily living skills) and yields an overall score, the Adaptive Behavior Composite (ABC). The standard ABC composite scores in VABS-3 are grouped into low (20–70), moderately low (71–85), adequate (86–114), moderately high (115–129), and high (130–140) categories. The VABS-3, Comprehensive Interview Form demonstrates reliable psychometric properties, showing a high level of internal consistency ranging from 0.90 to 0.9886. It is widely accepted as a measure of reported adaptive behavior in ASD and provides valuable information about an individual’s functional abilities in different areas of their daily life53–55.

Experimental setup and data acquisition

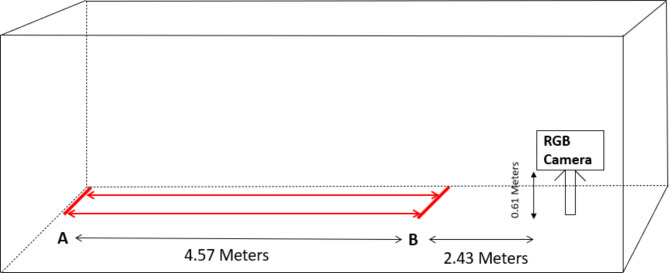

The experiment was conducted in a well-lit spacious hall. The participants were instructed to perform a simple walk with the go and stop signal from the instructor at a self-styled pace on a walking pathway. The participants walked back and forth from point A to point B on the walk pathway. The distance from point A to B was 4.57 m. They walked for 120 s or completed at least two trails. The walking pathway’s starting and end points were marked with colored tape. Each participant stood straight upright, facing the walking pathway, and started walking when instructed. Prior to the recording session, the participants engaged in a brief practice session to acquaint themselves with the procedure. The parent(s) of the children were watching the children performing the walk through the transparent glass in the next hall room. The graphical overview of the experimental setup is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the walk pathway and position of the camera facing the walk pathway.

The gait patterns of children with ASD and TD children were captured using an RGB camera, DJI Osmo Pocket. The camera was mounted on a tripod and positioned 0.61 m above the ground, facing the walking pathway from a distance of 2.43 m. The camera has 3-axis stabilization and an 80-degree field of view. It uses a 1/2.3 sensor and offers stable video recording, with the highest resolution being 3840 × 2160 pixels and a maximum of 120 frames per second. For this study, the videos were captured at a resolution of 1920 × 1080 pixels and a frame rate of 30 frames per second.

Data processing and calculation of gait parameters

The RGB video data was processed using the Google open-source pose estimation model of MediaPipe (MP). MP is a top-down approach to pose estimation, which uses the BlazePose topology to track the pose57. BlazePose increases the processing speed and, at the same time obtains a higher accuracy in pose estimation. MP has several advantages over other two-dimensional pose estimation models, such as open-source, the least requirement of advanced hardware, and can be operated on any commonly used operating system. It has been demonstrated that MP not only performs better than other two-dimensional pose estimation models but also has the highest correlation of gait kinematics with the standard gait measuring instrument56.

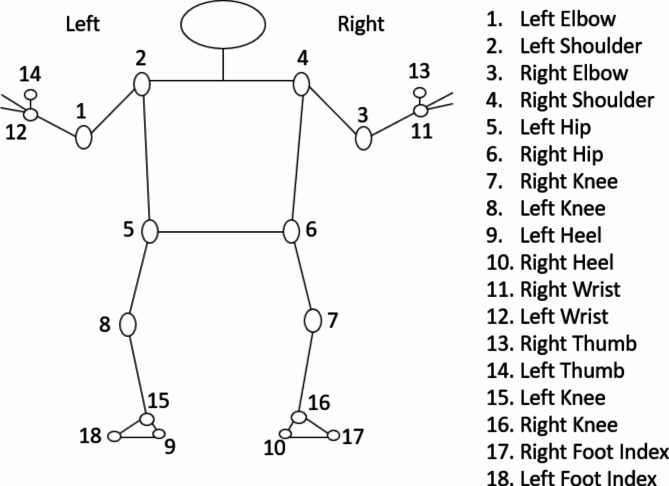

MP takes RGB data as input and produces 2D coordinates of a person’s joint anatomical positions as output. The process of pose estimation through MP involves a dual machine learning pipeline of detector and tracker. This established procedure encompasses two stages. The first stage involves placing a region-of-interest (ROI) representing a person’s pose onto a video frame using a detector. Following this, in the second stage, the tracker anticipates the landmarks of the pose along with a segmentation mask within the ROI. This prediction is based on utilizing the frame cropped within the ROI as input57. In the current study the MP was customized to generate 18 key points. These produced 18 key points of MP are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Coordinate positions of joint angles.

Based on 18 key points obtained from the MP, their two-dimensional coordinates were used to calculate the 12 joint anatomical angles on both the left and right sides of the body. After obtaining the coordinate positions of the joint angles, straightforward trigonometric equations are employed to compute the angles of the joints. As an illustration, to ascertain the angle at the elbow, the coordinates of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist are utilized. This involves applying trigonometric principles, particularly the dot product and the arccosine (inverse cosine) functions, to determine the angle formed between two vectors. The dot product, combined with the magnitudes of these vectors, serves to calculate the cosine value of the angle, which is then converted into degrees using the arccosine function (Eq. 1).

The angles calculated include left and right heel angle, left and right knee angle, left and right hip angle, left and right shoulder angle, left and right elbow angle, and left and right wrist angle. The angle of the heel was determined by using the position of the ankle, heel, and the index of the foot, while the angle of the knee was calculated by using the location of the hip, knee, and ankle. Similarly, the angle of the hip was determined by using the position of the shoulder, hip, and knee, and the angle of the shoulder was calculated using the location of the elbow, shoulder, and hip. The angle of the elbow was determined using the position of the shoulder, elbow, and wrist, and finally, the angle of the wrist was calculated using the position of the elbow, wrist, and thumb. From these coordinates, the required kinematic angles were calculated using the formula (1):

|

1 |

Finally, the joint angles over several frames were averaged by summing them up and then dividing by the total number of frames:

|

2 |

where N represents the total number of frames; Anglei denotes the angle value in the ith frame.

A Python program was developed to calculate six spatial and temporal gait parameters, step length, step time, stride time, stride length, speed, and cadence. To calculate these gait parameters, the program plotted the X coordinates of the right and left ankles on a graph to identify the intersection points and their corresponding frame positions. The X coordinate signals of both the ankles were initially smoothed using the Savitzky-Golay (SG; Fig. 3) filter58. The SG is a widely used signal processing technique for reducing noise and enhancing signal smoothness.

Fig. 3.

Graph of smoothed intersection points over time.

The SG algorithm starts by selecting a window around each data point in the spectrum, then fits a polynomial to the data points within that window. The data point is then replaced by the value from the fitted polynomial58. The window size in SG algorithm refers to the length of the filter window, which is associated with the number of coefficients. The polynomial parameters refer to the order of the polynomial used to fit the data within the window, and this order determines the degree of the polynomial used in the smoothing process. In this study, the parameters were set with a window length 11 and a polynomial order of 2. In SG algorithm, the smoothed value at a particular index i is computed as a weighted sum of neighboring data points, with the weights being the filter coefficients, as expressed in the following Eqs. 58,59:

|

3 |

where  indicates the smoothened value at the i index position in the data series,

indicates the smoothened value at the i index position in the data series,  represent the filter coefficients,

represent the filter coefficients,  are the data points in the neighborhood of the central point58.

are the data points in the neighborhood of the central point58.

Following the application of the SG filter, the intersection points were used to calculate step length, step time, stride length, and stride time. Step length was defined as the horizontal distance in meters between two consecutive ankle strikes of opposite feet. Step time was defined as the time in seconds between two consecutive ankle strikes of opposite feet. Stride length was defined as the horizontal distance in meters between two consecutive ankle strikes of the same foot, while stride time was defined as the time in seconds between two consecutive ankle strikes of the same foot. Speed was calculated as the total distance covered in meters per second. Given the total distance in meters and the total time in seconds, speed was computed by dividing the total distance by the total time. Cadence was defined as the total number of steps divided by the total time taken.

Data analyses

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was carried out in R60. The normality assumption of gait parameters was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Due to the small sample size and non-normal distribution of the data, a non-parametric statistical analysis was conducted. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to investigate the statistical differences in gait parameters between children with ASD and TD children. The Mann-Whitney U test is a non-parametric test that compares the ranks of values between two groups rather than their means, making it more suitable for non-normally distributed data. It is robust to outliers and does not require assumptions about the homogeneity of variances, making it a reliable alternative when these conditions are not met. Since the study is primarily exploratory, p-values of < 0.05 were considered as significant and the effect size was evaluated using r. Effect sizes of r = .1, r = .3, and r = .5 were considered small, medium, and large, respectively61. The correlation between ASD symptoms (ISAA) and significant gait variables in the two groups was evaluated using Spearman’s correlation. Spearman’s correlation is a non-parametric statistical test that relies on ranks, does not assume a linear relationship between the variables, and is robust to outliers, making it particularly suitable for the current study.

Classification algorithms

Multiple supervised machine learning classifiers were used to classify the two groups of children based on their gait parameters. These classifiers included two ensemble algorithms called Random Forest (RF) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), a non-linear model known as Support Vector Machine with Radial Basis Function Kernel (SVM-RBF), and a linear model, Binomial Logistic Regression (Logit).

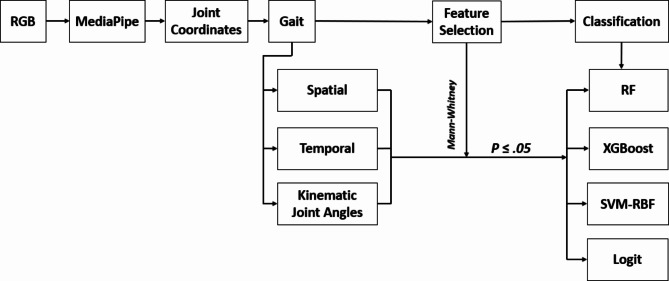

Feature selection refers to eliminating the irrelevant and retaining the relevant features for a given ML model. The selection and elimination of features in each ML model are essential because it helps to overcome overfitting, improving the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of a classifier. In the present study, the Mann-Whitney U test was used as a filter method of feature selection technique. Features with statistically significant differences between the groups, that is p ≤ .05 were retained and are essential for predicting the outcome variable. Features with non-significant differences between the groups, that is p ≥ .05 are considered less important in predicting the outcome variables and hence, excluded from the model. Previously it has been observed that the filter methods such as Mann-Whitney test and students t-test perform better than the wrapper and embedded techniques62. The caret package along with its dependencies in R was utilized to deploy the classifiers60. The data was randomly divided into a training set, which comprised 80% of the data, and a test set, which comprised 20% of the data. The training data was then subjected to repeated k-fold cross-validation with five repeats of 10-fold cross-validation. For each fold, 20 different combinations of hyperparameters for the algorithm were tested. The data underwent preprocessing using the preProcess() function from the caret package, which employed scale and center transformation methods to transform the data. To ensure a consistent replication, a random-number seed was used before each analysis63. The overall schematic representation of the analysis pipeline is given in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of analysis pipeline. First, the RGB input data was fed into MediaPipe to obtain joint coordinates. These coordinates were then used to calculate gait parameters. Next, the gait parameters of two groups of children, ASD and TD, were compared using statistical test such Mann-Whitney test. Any gait parameters that showed a significant difference (p ≤ .05) between the two groups were selected as features. Finally, machine learning (ML) classifiers were applied to these features for further analysis. RF is random forest, XGBoost is extreme gradient boosting machine, SVM-RBF is support vector machine-radial basis function, and Logit is binomial logistic regression.

Random Forests (RF) is an ensemble learning method that uses a combination of decision trees to improve the classification performance of a single tree classifier. From the training set  (includes n rows

(includes n rows  and n columns

and n columns  ), a set of m trees were built with individual weight functions

), a set of m trees were built with individual weight functions  in the individual tree leaf j, the prediction

in the individual tree leaf j, the prediction  of the new testing set x′ is64,65:

of the new testing set x′ is64,65:

|

4 |

The three gait parameters were utilized as M input features, and m features (m < < M) were selected at random to construct m decision trees for random forest. The value of ‘m’ remains constant during the growth of the forest, and each decision tree is expanded to the fullest extent possible.

The XGBoost employs the predictions of multiple weak models to generate a more robust prediction66,67. XGBoost maps the relationship between the input variables X = {x1, x2, ., xN} and target variable y. For a given dataset with n samples and m features, K additive functions are used in the XGBoost model to predict the output through the following estimation66,68:

|

5 |

where  is the regression tree’s space, and q denotes the independent structure of each tree with T leaves. Each fk corresponds to an independent tree structure q and leaf weights ω. To learn the set of functions, the following regularized objective is minimized.

is the regression tree’s space, and q denotes the independent structure of each tree with T leaves. Each fk corresponds to an independent tree structure q and leaf weights ω. To learn the set of functions, the following regularized objective is minimized.

|

6 |

where  denotes the model loss function, and

denotes the model loss function, and  denotes the regularized term.

denotes the regularized term.

Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier finds a hyperplane to separate different class instances with a maximum margin. It utilizes support vectors, the closest instances to the decision boundary, and incorporates a soft margin to handle misclassification69. SVM with radial kernel uses a nonlinear kernel to transform the input data into a higher-dimensional space. The Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel function measures the similarity or closeness between two points, xi and xj and is mathematically represented as:

|

7 |

where exp denotes the exponential function,  represents the squared Euclidean distance between the two points, and

represents the squared Euclidean distance between the two points, and  is the similarity or closeness value computed by the RBF kernel function for the given points xi and xj.

is the similarity or closeness value computed by the RBF kernel function for the given points xi and xj.

Binomial Logistic Regression (Logit) is used to model the relationship between a categorical dependent variable and multiple independent variables. It is commonly used when the dependent variable has only two categories (i.e., it is dichotomous). The model predicts the logit transformation of the probability of the event of interest. A binary variable with two categories denoted as y, and a set of p predictors denoted as  . The model predicts the logit transformation of the probability of the event y being equal to 1. The final output is derived by the following:

. The model predicts the logit transformation of the probability of the event y being equal to 1. The final output is derived by the following:

|

8 |

where, p represents the odds ratio, and it is calculated as:

|

is the intercept term.

is the intercept term.

are the coefficients of the predictor variables

are the coefficients of the predictor variables  .

.

Model evaluation

Multiple metrics were used to evaluate the performance of the model, including area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC), accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. The AUC is a common evaluation metric used for binary classification tasks and provides a useful summary of the classifier’s performance. The AUC score was calculated using the roc() function of the pROC library in R70. An AUC score of 0.8 to 0.9 is generally considered good, while a score above 0.9 is regarded as excellent, according to71. These metrics were computed from a confusion matrix that provided four outcomes: true positive (TP) for correctly predicted positive instances from positive classes, true negative (TN) for correctly predicted negative instances from negative classes, false positive (FP) for incorrectly predicted positive instances from negative classes, and false negative (FN) for incorrectly predicted negative instances from positive classes. Accuracy measures prediction correctness, sensitivity reflects group assignment accuracy, and specificity measures the accuracy of rejecting incorrect group assignment. These metrics were calculated using the following:

|

9 |

|

10 |

|

11 |

Results

Demographic and clinical measures

There were no significant differences between the ASD and TD groups in terms of age, sex, height, and weight. However, the groups did differ significantly in ABC and ABC domain scores. The detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| ASD (n = 32) | TD (n = 29) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 22/10 | 15/14 | p = .104 |

| Age (years) | 5.97 (2.67) | 4.86 (1.44) | p = .052 |

| Height (m) | 1.01 (0.25) | 0.95 (0.144) | p = .230 |

| Mass (kg) | 18.62 (7.18) | 17.59 (3.29) | p = .488 |

| ABC Standard Score | 74.03 (5.92) | 108.9 (7.36) | p = .000*** |

| ABC-Communication Domain Standard Score | 59.19 (14.11) | 99.76 (8.37) | p = .000*** |

| ABC-Daily Living Skills domain Standard Score | 86.78 (13.29) | 114.83 (9.51) | p = .000*** |

| ABC-Socialization Domain Standard Score | 80.56 (8.62) | 108.21 (10.85) | p = .000*** |

| ISAA Total | 120.42 (18.17) |

ABC is Adaptive Behavior Composite, ISAA is Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism. ***p ≤ .001..

Gait parameters

Among six temporal and spatial variables examined, children with ASD had a statistically significant decreased step length (p = .0284, r = .28) compared to the TD group. Among the kinematic angles analyzed, children with ASD displayed reduced right elbow° (p = .25, r = .28) and enlarged right shoulder° (p = .048, r = .25) compared to the TD children. The results of the comparison between ASD and TD children on gait parameters are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gait parameters.

| Parameter | ASD | TD | p-value | Effect Size (r) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median | Q1 | Q3 | Mean (SD) |

Median | Q1 | Q3 | |||

| Step Length (m) |

0.342 (0.08) |

0.349 | 0.295 | 0.399 |

0.394 (0.07) |

0.38 | 0.342 | 0.456 | 0.028 | 0.28 |

| Step Time (seconds) |

0.642 (0.31) |

0.543 | 0.461 | 0.734 |

0.563 (0.28) |

0.50 | 0.444 | 0.585 | 0.197 | 0.17 |

| Cadence (steps/second) |

1.757 (0.63) |

1.737 | 1.46 | 2.061 |

1.566 (0.53) |

1.654 | 1.389 | 1.961 | 0.38 | 0.11 |

| Stride Time (seconds) |

1.334 (0.39) |

1.401 | 1.23 | 1.65 |

1.284 (0.45) |

1.285 | 1.152 | 1.424 | 0.30 | 0.13 |

| Stride Length (m) |

0.755 (0.24) |

0.789 | 0.651 | 0.869 |

0.781 (0.31) |

0.748 | 0.67 | 0.972 | 0.64 | 0.06 |

| Speed (seconds) |

2.33 (0.91) |

2.25 | 1.79 | 2.856 |

2.82 (1.12) |

2.744 | 2.137 | 2.781 | 0.057 | 0.24 |

| Left Elbow° |

139.33 (32.32) |

153.50 | 125.29 | 160.62 |

146.97 (29.33) |

161.28 | 140.13 | 167.09 | 0.11 | 0.21 |

| Right Elbow° |

138.25 (32.85) |

149.76 | 127.71 | 163.36 |

150.80 (26.12) |

160.94 | 140.59 | 169.46 | 0.025 | 0.28 |

| Left Shoulder° |

14.24 (12.05) |

10.79 | 9.58 | 13.98 |

13.09 (6.88) |

10.72 | 9.49 | 14.68 | 0.84 | 0.03 |

| Right Shoulder° |

13.82 (8.77) |

12.28 | 8.29 | 16.68 |

11.14 (9.44) |

6.96 | 5.78 | 13.70 | 0.048 | 0.25 |

| Left Hip° |

171.05 (5.66) |

172.76 | 170.72 | 173.28 |

171.97 3.99) |

172.65 | 171.59 | 173.30 | 0.54 | 0.08 |

| Right Hip° |

170.82 (6.33) |

172.31 | 170.60 | 173.51 |

172.76 (2.10) |

172.82 | 172.11 | 173.98 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| Left Knee° |

166.56 (5.77) |

167.77 | 165.01 | 169.57 |

167.86 (5.47) |

167.85 | 165.52 | 171.54 | 0.23 | 0.16 |

| Right Knee° |

166.42 (8.51) |

167.83 | 165.21 | 170.28 |

168.03 (3.87) |

166.93 | 165.21 | 171.31 | 0.99 | 0.00 |

| Left Heel° |

80.86 (9.03) |

79.22 | 75.13 | 82.36 |

86.04 (18.27) |

81.80 | 78.09 | 90.54 | 0.18 | 0.17 |

| Right Heel° |

83.58 (10.82) |

82.10 | 76.75 | 85.96 |

82.27 (10.59) |

79.78 | 74.79 | 84.35 | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| Left Wrist° |

157.22 (10.16) |

159.94 | 153.36 | 164.16 |

157.01 (8.97) |

160.07 | 152.35 | 162.86 | 0.81 | 0.03 |

| Right Wrist° |

158.15 (8.85) |

159.65 | 153.73 | 163.18 |

159.75 (12.23) |

162.71 | 156.57 | 168.00 | 0.10 | 0.21 |

Q1 and Q3 are 25th and 75th percentiles respectively. *p ≤ .05..

Relation between gait and ASD

Spearman’s correlation was used to investigate the association between significant gait parameters and symptoms of ASD as measured by the ISAA scale. The results revealed that right shoulder° was positively correlated with the Sensory Aspects subscale of ISAA (ρ = 0.373, p = .039), suggesting that right shoulder° was associated with increased sensory symptoms in children with ASD. Spearman’s correlation heatmap of the gait parameters and ASD symptoms is given in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Correlation heatmap of significant gait parameters and ASD symptoms in children with ASD.

Classification of TD-ASD children using ML

The three significant gait parameters (p ≤ .05) described above, step length, right elbow°, and right shoulder°, were used as input predictors while ASD or TD group classification was treated as binary outcomes. The performance of ML classifiers is given Table 3. The accuracies were 0.73, 0.64, 0.73, and 0.82, respectively for RF, XGBoost, SVM-RBF, and Logit models. The sensitivities were 0.80., 0.80., 0.60., and 1.0, respectively for RF, XGBoost, SVM-RBF, and Logit models. The specificity of the models was 0.67, 0.50, 0.83, and 67, respectively for RF, XGBoost, SVM-RBF, and Logit. The Logit model had the highest AUC of 0.97, which was followed by RF and SVM-RBF. XGBoost had the lowest AUC of 0.65. RF and SVM-RBF performed almost equally in classifying the two groups based on three gait parameters. XGBoost performed lowest with an accuracy of 0.64 and AUC of 0.65. The Logit was the best performer in classifying the ASD and TD children with an accuracy of 0.82 and an AUC of 0.97 (Fig. 6).

Table 3.

Performance of ML classifiers.

| Model | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.9 |

| XGBoost | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.50 | 0.65 |

| SVM-RBF | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.83 | 0.90 |

| Logit | 0.82 | 1.0 | 0.67 | 0.97 |

Fig. 6.

Logit ROC curve.

Four models, including RF, XGBoost, SVM-RBF, and Logit, were employed to classify the two groups on three gait parameters. The Logit model outperformed the other models with an accuracy of 0.82, sensitivity of 1.0, specificity of 0.67, and an AUC of 0.97. This suggests that the Logit model is the most effective in distinguishing between two groups using the three gait parameters.

Discussion

The primary objective of the current study was to evaluate the gait function in children with ASD and TD children using a computer-vision (CV) based non-intrusive and economic framework. To achieve this, the study used an RGB camera to record gait patterns of participants. MediaPipe, a 2D-based pose estimation model, was employed to extract the joint coordinates from the recorded digital images. These joint coordinates were then used to calculate the spatial, temporal, and kinematic gait parameters. The quantified spatial, temporal, and kinematic joint angles parameters of children with ASD were compared with the TD children. The results showed that the children with ASD had significantly smaller step length compared to the TD children. This is congruent with the previous studies indicating a shorter step length in children with ASD15,46,72. Children with ASD tend to employ a strategy by lowering their step length so that they move smoothly and maintain stability and balance in locomotion. As a result, children with ASD may reduce their speed, however, this was statistically insignificant. However, two kinematic angles were significantly different between ASD and TD children, right elbow° and right shoulder°. The ASD group had significantly reduced left elbow° and enlarged right shoulder°. Reduced right elbow° is inconsistent with the findings of Shetreat-Klein et al.23. These researchers found that ASD participants had elaborated elbow angle in comparison to TD participants.

The findings indicate that children with ASD exhibit an abnormal walking pattern characterized by shorter step length, reduced right elbow°, and increased right shoulder °. This distinctive gait pattern, characterized by a shorter step length, may result in a more constrained, less flexible gait. The altered joint kinematic angles further appear to make these gait patterns rigid and stiff. Together, these findings suggest that the combination of these factors may contribute to a less flexible and more restricted gait in children with ASD, potentially affecting their movement and mobility. Vilensky et al.37 and Damasio and Maurer73 studied gait and observed reduced step/stride length in autism. They suggest that gait in ASD resembles the Parkinson’s gait and, therefore, hypothesized the dysfunctioning of the basal ganglia in autism. However, some researchers have argued against these findings. For instance, Hallet et al.74 found no significant difference in spatiotemporal parameters between adults with autism and healthy participants. Nonetheless, the same study found differences in gait variability parameters, implying that the dysfunction in the cerebellum may play a role in the gait abnormalities observed in autism. Recent research has indicated both the shortened step/stride length and greater variability in ASD gait15,43,46. Further research in this area may provide valuable insights into the underlying neural mechanisms contributing to gait dysfunction in this population.

Right shoulder° was significantly associated with Sensory Aspects of ISAA. The Sensory Aspects in ISAA measures the hyper-hypo sensitivity to stimulation. The relationship between the right shoulder° and sensory aspects of ASD may indicate poor sensory motor integration in individuals with ASD during locomotion. Accurate integration of sensory information from different sensory modalities is necessary for effective locomotion. Thus, alterations in sensory-motor integration can have negative impacts on locomotion and may affect the ASD severity. Previously, poor sensory-motor integration has been shown to have an association with ASD severity13,75. A study by Goulème et al.76 showed poor integration of information in the visual field had aggravated postural instability in ASD participants, suggesting a poor integration of sensory-motor integration in ASD during locomotion. Although the underlying neural mechanism of ASD is poorly understood, the cerebellum has a crucial function in integrating the sensory-motor information77.

For a long time, sensory and motor impairments were thought to be only peripheral features of ASD. However, recent updates in the diagnostic criteria of ASD in DSM-5 have included atypical sensory reactivity, highlighting the importance of sensory processing issues in ASD1. It’s worth noting that the sensory and motor systems in the human body are closely related, and any alterations in one can affect the other12. Thus, it is crucial to consider a broader framework, such as a ‘central theory of sensorimotor integration’ or a ‘theory of sensory-motor development’, to understand the difficulties in sensory-motor integration observed in individuals with ASD12,78. Motor impairments, including gait, may serve as a helpful tool in identifying and detecting ASD and may potentially serve as a biomarker. Further research in this area can provide valuable insights into the underlying neural and psychological mechanisms of motor impairments in ASD and help develop effective interventions.

Lastly, the current study aimed to classify ASD and TD children based on gait parameters using machine learning models. The highest accuracy of 0.82 was achieved by the Logit model in classifying the ASD and TD children. In other studies, different machine learning techniques and features have been utilized to classify ASD and TD children. For instance, SVM and Neural Networks were used in a study with multiple gait parameters to achieve an accuracy of 95%79. Al-Jubouri et al.80 employed dataset augmentation, and a rough set classifier based on joint kinematic angles to improve their accuracy from 60 to 92%. In another recent study, non-verbal aspects of social interaction in young children were quantified using the 2D pose estimation model. A neural network was used to predict ASD, achieving an accuracy of 80%9. The accuracy of Logit model is relative comparable to the other studies in terms of accuracy, and the use of the Mann-Whitney test for feature selection and the classification accuracy of the Logit model based on statistically significant features between the groups can be considered a strength of the current study. Machine learning and gait parameters seem promising tools for classifying ASD and TD children, with potential implications for early detection, diagnosis, and intervention.

The findings of the study may hold significant utilitarian value in the early detection and diagnosis of ASD. Motor behaviors and impairments, such as gait, often manifest prior to the development of social and communication deficits in children with ASD6,81. Since these motor behaviors can be objectively quantified from the first day of life, they hold significance for early detection of the disorder. The study offers preliminary insights into motor behavior and gait as a potential behavioral marker for ASD, suggesting that current diagnostic practices could be made more comprehensive by incorporating these motor impairments and behaviors. Combining gait patterns with machine learning techniques could greatly enhance the automated and computer-assisted early detection of ASD. By analyzing a few key gait parameters, machine learning models have the potential to identify subtle patterns that might be overlooked in traditional behavioral assessments. This approach, which integrates objective gait assessments with machine learning, could enable earlier and more accurate diagnoses of ASD. Moreover, because it is data-driven, this method may help reduce clinician bias and improve consistency in diagnosis, ultimately leading to better clinical outcomes for children on the ASD spectrum.

When ASD is diagnosed in the early stages of critical development, the advantages of brain plasticity can be leveraged to prevent the full manifestation of ASD symptoms in young children8. As a result, the lives of these children may be significantly improved. Traditionally, interventions for ASD have focused on social and communication impairments82. However, based on the findings of this and previous studies, tailored interventions could also be developed to address gait impairments in children with ASD.

Conclusion and limitations

The study assessed spatiotemporal and kinematic gait parameters in children with ASD and compared these parameters with those of TD children. The associations between significant gait parameters and ASD symptoms were also evaluated. Machine learning techniques were employed using a select number of gait parameters to classify the two groups of children. The results revealed that children with ASD exhibited reduced step length and a smaller right elbow°, as well as an enlarged right shoulder°, compared to TD children. The right shoulder° was significantly associated with sensory symptoms in children with ASD. Several machine learning algorithms were tested to classify the two groups, with the Logit achieving the highest accuracy of 82% (0.82) in accurately distinguishing between children with ASD and TD children, based on a few key gait parameters, including step length, right elbow°, and right shoulder°.

While the study provides valuable insights into gait parameters in children with ASD, several limitations must be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample size was small, which could limit the statistical power of the analysis and reduce the generalizability of the results. A small sample may not adequately represent the full spectrum of children with ASD. Second, the study did not assess sex differences in gait patterns, which may further limit the generalizability of the findings. Without exploring sex-specific differences in gait parameters, the study may overlook important nuances of gait in children with ASD. As a result, the findings may be more applicable to male children with ASD and may not fully capture potential sex-specific gait patterns, warranting further investigation in future research. Lastly, the associations between gait and ASD symptoms were weak, which suggests that these findings are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution.

Future studies should consider recruiting a larger sample to represent a more diverse cohort of children with ASD, ensuring that the findings are applicable across the full spectrum of the disorder. Sex differences in gait parameters, as well as how these gait patterns are associated with ASD symptoms, should also be explored. The relationship between sensory symptoms and gait parameters in children with ASD could be a valuable area for future research. Investigating how sensory information integrates with motor commands in these children may offer further insight into the underlying neuropsychological mechanisms. While supervised machine learning was used in the present study, future research could benefit from more advanced techniques, such as unsupervised machine learning, deep learning, and time-series data analysis, to better classify children with ASD. Lastly, exploring the neural correlates of impaired gait in children with ASD would provide an interesting and important avenue for future studies.

While previous studies have successfully used a single RGB camera from the frontal view along with MediaPipe to calculate gait parameters, this method, although promising, still suffers from several limitations83. A single RGB camera captures only 2D information, which significantly limits the ability to accurately assess gait. Although we manually examined video occlusions, this remains a challenge with the single-camera setup, potentially leading to missing or imprecise data on limb positions, thereby impacting the accuracy of the analysis. Moreover, the positioning of the camera is crucial, improper adjustment can lead to skewed results and unreliable gait parameters. MediaPipe is a powerful and lightweight tool for pose estimation, but the accuracy of key point detection can be affected by various factors, such as lighting conditions and the participant’s posture. Furthermore, alternative open-source pose estimation models, such as OpenPose84 and AlphaPose85, could be explored and compared to MediaPipe for potential improvements in accuracy.

To address these challenges, future studies may benefit from incorporating multiple RGB cameras and depth sensors placed on different planes. This would allow for more accurate reconstruction of joint positions and limb movements, leading to more reliable gait analysis. Furthermore, wearable sensors attached to the body or marker-based systems offer highly accurate measurements of gait, joint angles, and posture, which are valuable in both clinical and non-clinical settings. However, these systems tend to be costly and require controlled environments, which may not be feasible for all research settings. Therefore, we suggest that future studies integrate advanced machine learning and deep learning techniques to enhance the accuracy and adaptability of gait analysis with a single RGB camera. By combining these advanced methods with improved pose estimation models, we can potentially overcome some of the limitations of current approaches and achieve more reliable results in real-world applications.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants that took part in the study and staff at the rehabilitation centers that helped in the data collection. We would also like to thank Dr. Rashmi Kapoor, founder and director of AMRITA-School for Special Children, for allowing us to collect data at their center.

Author contributions

UJG: conceptualization, methodology and design, data collection, data analysis, writing and editing the original draft. AR: Data collection and data analysis. BB: Conceptualization and design, editing and reviewing the draft. KSV: Methodology, software, and infrastructural support. All authors read and approved the fnal manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Informed consent

The written consent was obtained from the parents of the children prior to the data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- 2.Zeidan, J. et al. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res.15(5), 778–790. 10.1002/aur.2696 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels, A. M. & Mandell, D. S. Explaining differences in age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: A critical review. Autism18(5), 583–597. 10.1177/1362361313480277 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van’t Hof, M. et al. Age at autism spectrum disorder diagnosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2012 to 2019. Autism25(4), 862–873. 10.1177/1362361320971107 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crane, L., Chester, J. W., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A. & Hill, E. Experiences of autism diagnosis: A survey of over 1000 parents in the United Kingdom. Autism20(2), 153–162. 10.1177/1362361315573636 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vabalas, A., Gowen, E., Poliakoff, E. & Casson, A. J. Applying machine learning to kinematic and eye movement features of a movement imitation task to predict autism diagnosis. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-020-65384-4 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw, J., Steiner, A. M., Gengoux, G. & Koegel, L. K. Feasibility and effectiveness of very early intervention for infants at-risk for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. J. Autism Dev. Disord.45(3), 778–794. 10.1007/s10803-014-2235-2 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dawson, G. Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Dev. Psychopathol.20(3), 775–803. 10.1017/s0954579408000370 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kojovic, N., Natraj, S., Mohanty, S. P., Maillart, T. & Schaer, M. Using 2D video-based pose estimation for automated prediction of autism spectrum disorders in young children. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-021-94378-z (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ben-Sasson, A., Gal, E., Fluss, R., Katz-Zetler, N. & Cermak, S. A. Update of a meta-analysis of sensory symptoms in ASD: A new decade of research. J. Autism Dev. Disord.49(12), 4974–4996. 10.1007/s10803-019-04180-0 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson, C. E. & Baron-Cohen, S. Sensory perception in autism. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.18(11), 671–684. 10.1038/nrn.2017.112 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whyatt, C. & Craig, C. Sensory-motor problems in Autism. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience10.3389/fnint.2013.00051 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowen, E. & Hamilton, A. Motor abilities in autism: A review using a computational context. J. Autism Dev. Disord.43(2), 323–344. 10.1007/s10803-012-1574-0 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mosconi, M. W. & Sweeney, J. A. Sensorimotor dysfunctions as primary features of autism spectrum disorders. Sci. China Life Sci.58(10), 1016–1023. 10.1007/s11427-015-4894-4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss, M. J., Moran, M. F., Parker, M. E. & Foley, J. T. Gait analysis of teenagers and young adults diagnosed with autism and severe verbal communication disorders. Front. Integr. Neurosci.10.3389/fnint.2013.00033 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casartelli, L., Molteni, M. & Ronconi, L. So close yet so far: Motor anomalies impacting on social functioning in autism spectrum disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.63, 98–105. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.001 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanner, A. Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child2, 217–250 (1943). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier, K. A., Hass, C. J., Naik, S. K., Lodha, N. & Cauraugh, J. H. Motor coordination in autism spectrum disorders: A synthesis and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord.40(10), 1227–1240. 10.1007/s10803-010-0981-3 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim, Y. H., Partridge, K., Girdler, S. & Morris, S. L. Standing postural control in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Autism Dev. Disord.47, 2238–2253. 10.1007/s10803-017-3144-y (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uljarević, M., Hedley, D., Alvares, G. A., Varcin, K. J. & Whitehouse, A. J. O. Relationship between early motor milestones and severity of restricted and repetitive behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res.10(6), 1163–1168. 10.1002/aur.1763 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrow, W. J., Jaworski, M. & Accardo, P. J. Persistent toe walking in autism. J. Child Neurol.26(5), 619–621. 10.1177/0883073810385344 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fournier, K. A., Amano, S., Radonovich, K. J., Bleser, T. M. & Hass, C. J. Decreased dynamical complexity during quiet stance in children with autism spectrum disorders. Gait Post.39(1), 420–423. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2013.08.016 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shetreat-Klein, M., Shinnar, S. & Rapin, I. Abnormalities of joint mobility and gait in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev.36(2), 91–96. 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.02.005 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Travers, B. G. et al. Brainstem white matter predicts individual differences in manual motor difficulties and symptom severity in sutism. J. Autism Dev. Disord.45(9), 3030–3040. 10.1007/s10803-015-2467-9 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travers, B. G., Powell, P. S., Klinger, L. G. & Klinger, M. R. Motor difficulties in autism spectrum disorder: Linking symptom severity and postural stability. J. Autism Dev. Disord.43(7), 1568–1583. 10.1007/s10803-012-1702-x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radonovich, K. J., Fournier, K. A. & Hass, C. J. Relationship between postural control and restricted, repetitive behaviors in autism spectrum disorders. Front. Integr. Neurosci.10.3389/fnint.2013.00028 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torres, E. B. & Donnellan, A. M. Editorial for research topic “Autism: the movement perspective”. Front. Integr. Neurosci.10.3389/fnint.2015.00012 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Esposito, G. & Paşca, S. P. Motor abnormalities as a putative endophenotype for autism spectrum disorders. Front. Integr. Neurosci.10.3389/fnint.2013.00043 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anzulewicz, A., Sobota, K. & Delafield-Butt, J. T. Toward the autism motor signature: Gesture patterns during smart tablet gameplay identify children with autism. Sci. Rep.10.1038/srep31107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilton, C. et al. Relationship between motor skill impairment and severity in children with Asperger syndrome. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord.1(4), 339–349. 10.1016/j.rasd.2006.12.003 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green, D. et al. Impairment in movement skills of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.51(4), 311–316. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03242.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burnett, C. N. & Johnson, E. W. Development of gait in childhood. Part I: Method. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.13(2), 196–206. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1971.tb03245.x (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnett, C. N. & Johnson, E. W. Development of gait in childhood: Part II. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.13(2), 207–215. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1971.tb03246.x (1971). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forssberg, H. Ontogeny of human locomotor control. I. Infant stepping, supported locomotion and transition to independent locomotion. Exp. Brain Res.10.1007/bf00237835 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thelen, E. & Cooke, D. W. Relationship between newborn stepping and latter walking: A new interpretation. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.29(3), 380–393. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1987.tb02492.x (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivanenko, Y. P., Dominici, N. & Lacquaniti, F. Development of independent walking in toddlers. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev.35(2), 67–73. 10.1249/jes.0b013e31803eafa8 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vilensky, J. A. Gait disturbances in patients with autistic behavior. Arch. Neurol.38(10), 646. 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510100074013 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghaziuddin, M., Butler, E., Tsai, L. & Ghaziuddin, N. Is clumsiness a marker for Asperger syndrome?. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res.38(Pt5), 519–527. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1994.tb00440.x (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manjiviona, J. & Prior, M. Comparison of Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autistic children on a test of motor impairment. J. Autism Dev. Disord.25(1), 23–39. 10.1007/bf02178165 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kindregan, D., Gallagher, L. & Gormley, J. Gait deviations in children with autism spectrum disorders: A review. Autism Res. Treat.2015, 1–8. 10.1155/2015/741480 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lum, J. A. G. et al. Meta-analysis reveals gait anomalies in autism. Autism Res.14(4), 733–747. 10.1002/aur.2443 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rinehart, N. J. et al. Gait function in high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry15(5), 256–264. 10.1007/s00787-006-0530-y (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rinehart, N. J. et al. Gait function in newly diagnosed children with autism: cerebellar and basal ganglia related motor disorder. Dev. Med. Child Neurol.48(10), 819. 10.1017/s0012162206001769 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Marchena, A. & Miller, J. “Frank” presentations as a novel research construct and element of diagnostic decision-making in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res.10(4), 653–662. 10.1002/aur.1706 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biffi, E. et al. Gait pattern and motor performance during discrete gait perturbation in children with autism spectrum disorders. Front. Psychol.10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02530 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nobile, M. et al. Further evidence of complex motor dysfunction in drug naïve children with autism using automatic motion analysis of gait. Autism15(3), 263–283. 10.1177/1362361309356929 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Belen, R. A. J., Bednarz, T., Sowmya, A. & Del Favero, D. Computer vision in autism spectrum disorder research: A systematic review of published studies from 2009 to 2019. Transl. Psychiatry10.1038/s41398-020-01015-w (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ardalan, A., Assadi, A. H., Surgent, O. J. & Travers, B. G. Whole-Body movement during videogame play distinguishes youth with autism from youth with typical development. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-019-56362-6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment: Government of India. Report on Assessment Tool for Autism: Indian Scale for Assessment of Autism (ISAA) (2009). https://thenationaltrust.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/ISAA%20TEST%20MANNUAL(2).pdf.

- 50.Chakraborty, S., Thomas, P., Bhatia, T., Nimgaonkar, V. L. & Deshpande, S. N. Assessment of severity of autism using the Indian scale for assessment of autism. Indian J. Psychol. Med.37(2), 169–174. 10.4103/0253-7176.155616 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., DeVellis, R. F. & Daly, K. Toward objective classification of childhood autism: Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). J. Autism Dev. Disord.10(1), 91–103. 10.1007/BF02408436 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V. & Saulnier, C. A. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Third edition (Vineland-3) (NCS Pearson, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carter, A. S. et al. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Supplementary norms for individuals with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord.10.1023/a:1026056518470 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perry, A., Flanagan, H. E., Dunn Geier, J. & Freeman, N. L. Brief Report: The Vineland adaptive behavior scales in young children with autism spectrum disorders at different cognitive levels. J. Autism Dev. Disord.39(7), 1066–1078. 10.1007/s10803-009-0704-9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ray-Subramanian, C. E., Huai, N. & Ellis Weismer, S. Brief report: Adaptive behavior and cognitive skills for toddlers on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord.41(5), 679–684. 10.1007/s10803-010-1083-y (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hii, C. S. T. et al. Automated gait analysis based on a marker-free pose estimation model. Sensors23(14), 6489. 10.3390/s23146489 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pose Landmark Detection Guide. Retrieved May 20, 2023, from (n.d.). https://developers.google.com/mediapipe/solutions/vision/pose_landmarker/

- 58.Pelliccia, D. Savitzky–Golay Smoothing Method. NIRPY research (2019). https://nirpyresearch.com/savitzky-golay-smoothing-method/

- 59.Lim, Z. K., Connie, T., Goh, M. K. O. & Saedon, N. I. B. Fall risk prediction using temporal gait features and machine learning approaches. Front. Artif. Intell.7, 1425713. 10.3389/frai.2024.1425713 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R (Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022). https://www.R-project.org/.

- 61.Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed.). (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988).

- 62.Haury, A. C., Gestraud, P. & Vert, J. P. The influence of feature selection methods on accuracy, stability and interpretability of molecular signatures. PloS ONE6(12), e28210. 10.1371/journal.pone.0028210 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw.10.18637/jss.v028.i05 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn.45, 5–32. 10.1023/A:1010933404324 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhou, Y. et al. The detection of age groups by dynamic gait outcomes using machine learning approaches. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-020-61423-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost, in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (2016). 10.1145/2939672.2939785

- 67.Dey,. Machine learning algorithms: A review. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol.7(3), 1174–1179 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Noh, B. et al. XGBoost based machine learning approach to predict the risk of fall in older adults using gait outcomes. Sci. Rep.10.1038/s41598-021-91797-w (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Boser, B. E., Guyon, I. M. & Vapnik, V. N. A training algorithm for optimal margin classifiers, in Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Workshop on Computational Learning Theory (1992). 10.1145/130385.130401

- 70.Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform.10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tharwat, A. Classification assessment methods. Appl. Comput. Inform.17(1), 168–192. 10.1016/j.aci.2018.08.003 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vernazza-Martin, S. et al. Goal directed locomotion and balance control in autistic children. J. Autism Dev. Disord.35(1), 91–102. 10.1007/s10803-004-1037-3 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Damasio, A. R. & Maurer, R. G. A neurological model for childhood autism. Arch. Neurol.35(12), 777–786. 10.1001/archneur.1978.00500360001001 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hallett, M. et al. Locomotion of autistic adults. Arch. Neurol.50(12), 1304–1308. 10.1001/archneur.1993.00540120019007 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hannant, P., Cassidy, S., Tavassoli, T. & Mann, F. Sensorimotor difficulties are associated with the severity of autism spectrum conditions. Front. Integr. Neurosci.10.3389/fnint.2016.00028 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goulème, N. et al. Postural control and emotion in children with autism spectrum disorders. Transl. Neurosci.10.1515/tnsci-2017-0022 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Glickstein, M. Cerebellum and the sensory guidance of movement. Novartis Found. Sympos.10.1002/9780470515563.ch14 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hannant, P., Tavassoli, T. & Cassidy, S. The role of sensorimotor difficulties in autism spectrum conditions. Front. Neurol.10.3389/fneur.2016.00124 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ilias, S., Tahir, N. M., Jailani, R. & Hasan, C. Z. C. Classification of autism children gait patterns using neural network and support vector machine, in 2016 IEEE Symposium on Computer Applications & Industrial Electronics (ISCAIE) (2016). 10.1109/iscaie.2016.7575036

- 80.Al-Jubouri, A. A., Ali, I. H. & Rajihy, Y. Gait and full body movement dataset of autistic children classified by rough set classifier. J. Phys. Conf. Ser.1818(1), 012201. 10.1088/1742-6596/1818/1/012201 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhat, A. N. Motor impairment increases in children with autism spectrum disorder as a function of social communication, cognitive and functional impairment, repetitive behavior severity, and comorbid diagnoses: A SPARK study report. Autism Res.14(1), 202–219. 10.1002/aur.2453 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bhat, A. N. Fewer children with autism spectrum disorder with motor challenges receive physical and recreational therapies compared to standard therapies: A SPARK data set analysis. Autism28(5), 1161–1174. 10.1177/136236132311931 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hii, C. S. T., Gan, K. B., You, H. W., Zainal, N., Ibrahim, N. M. & Azmin, S. Frontal plane gait assessment using MediaPipe pose, in Islam, M. T., Misran, N., Singh, M. J. (Eds) Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Space Science and Communication. IconSpace 2023. Springer Proceedings in Physics, vol 303 (Springer, 2024). 10.1007/978-981-97-0142-1_34

- 84.Cao, Z., Simon, T., Wei, S. E. & Sheikh, Y. Realtime multi-person 2D pose estimation using part affinity fields, in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7291–7299 (2017). https://openaccess.thecvf.com/content_cvpr_2017/papers/Cao_Realtime_Multi-Person_2D_CVPR_2017_paper.pdf

- 85.Fang, H. S. et al. AlphaPose: Whole-body regional multi-person pose estimation and tracking in real-time. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell.45(6), 7157–7173. 10.1109/TPAMI.2022.3222784 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hill, T. L., Saulnier, C. A., Cicchetti, D., Gray, S. A. O. & Carter, A. S. Vineland III, in Volkmar, F. (Eds.) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders (Springer, 2017). 10.1007/978-1-4614-6435-8_102229-1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.