Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate whether cumulative impact load and serum biomarkers are related to lower-extremity injury and to determine any impact load and cartilage biomarker relationships in collegiate female basketball athletes.

Methods

This was a prospective longitudinal study evaluating lower-extremity impact load, serum cartilage biomarkers, and injury incidence over the course of a single collegiate women’s basketball season. Data were collected from August 2022 to April 2023; no other follow-up after the cessation of the season was conducted in this cohort. Inclusion criteria for the study included collegiate women’s basketball athletes, ages 18 to 25 years, who were noninjured at the start of the study time frame (August 2024). Cartilage synthesis (procollagen II carboxy propeptide and aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope) and degradation (collagen type II cleavage) biomarkers were evaluated at 6 season timepoints. Impact load metrics (cumulative bone stimulus, impact intensity) were collected during practices using inertial measurement units secured to the distal medial tibiae. Injury was defined as restriction of participation for 1 or more days beyond day of initial injury. Cumulative impact load metrics were calculated over the week before any documented injury and blood draws for analysis. Point biserial and Pearson product moment correlations were used to determine the relationship between impact load metrics, serum biomarkers, and injury.

Results

Eleven collegiate women’s basketball athletes (height: 1.86 meters, mass: 82.0 kg, age: 20.54 years) participated. Greater medium-range (6-20 g) cumulative impact intensities during week 5 and 6 for both limbs (r = 0.674, P = .023) and high-range (20-200 g) during week 8 for both limbs (0.672, P = .024) were associated with injury. Greater cumulative bone stimulus was associated with increased procollagen II carboxy propeptide levels before conference playoffs for right (r = 0.694, P = .026) and left (r = 0.747, P = .013) limbs. Greater chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope levels at off-season-1 (r = 0.729, P = .017), and at the beginning of the competitive season (r = 0.645, P = .044) were associated with season-long injury incidence.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that moderate-to-high intensity impacts (6-200 g) early in the season were associated with subsequent injury among female collegiate basketball players. Increased cartilage synthesis at various time points was correlated with increased cumulative bone stimulus metrics and season-long injury incidence in this population.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, prognostic case series.

There are approximately half a million1,2 female athletes participating in basketball in the United States at the high school or college level. Injuries can occur from acute high-impact loads or from cumulative loading over time, increasing the vulnerability of the joint. Impact loading during landing has been associated with acute joint injuries such as anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears3 and chronic overuse injuries such as patellofemoral pain.4,5 Female athletes are more likely to sustain such injuries compared with their male counterparts, with 41.7% of traumatic injuries occurring to the knee and ankle.6 Both ankle and knee joint injuries, which result in chronic instability, drastically increase the risk for early development of osteoarthritis (OA).7, 8, 9, 10

Previous work suggests that individuals who go on to sustain ACL injury and those with chronic ankle instability exhibit greater vertical impact peak forces compared with healthy individuals.3,11 Individuals with ACL injury also may present with altered biomechanical movement strategies in the sagittal and frontal planes.12, 13, 14, 15 High-impact loads, coupled with faulty alignments, may further amplify abnormal loading of joints, increasing the long-term risk for recurrent injury and joint damage.9,16 Both acute and cumulative impact forces have been cited as strong predictors of running-related injuries.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 However, there is less evidence to indicate that cumulative impact loading has the same relationship with ankle and knee joint injuries commonly sustained during basketball. Tibial mounted inertial measurement units (IMUs) can provide a surrogate measure of the vertical force load rates during running and landing activities.24,25 Further, the use of IMUs to monitor athletes’ impacts load over multiple days, weeks, or months provides an affordable, direct, and noninvasive way to evaluate the cumulative load sustained by musculoskeletal tissue(s) during sports participation.

Excessive impact forces, singular or cumulative over time, also may initiate an inflammatory process in the joint that leads to the degeneration of articular cartilage and underlying subchondral bone.9 Studies26,27 have proposed the use of serum biomarkers panels of cartilage turnover to potentially identify individuals at risk of injury. These biomarkers are not abundant in healthy joints and are suggested to be an indication of trauma or load-related inflammation.28 Individuals who demonstrate elevated cartilage turnover levels may already be exhibiting faulty biomechanical strategies affecting the internal biochemical processes occurring within the joint.27 Thus, an imbalance in underlying metabolic processes associated with the maintenance of cartilage turnover or cumulative tissue load (i.e., collagen synthesis and degradation) may serve as a precursor to injury.26 Research has demonstrated that cartilage degradation and synthesis biomarkers levels were significantly associated with the subsequent likelihood of sustaining an ACL injury. Multiple studies also support that biomarker fluctuations observed after ACL injury27,29,30 and after some forms of exercise31 may negatively influence long-term joint health. This relationship relative to other lower-extremity joint injuries should be considered. Serial evaluation of cumulative impact loading and joint injury biomarkers can provide important context regarding fluctuations in these metrics over the course of an athletic season and extend outside the scope of previous work.27 Therefore, the purposes of this study were to evaluate whether cumulative impact load and serum biomarkers are related to lower-extremity injury and to determine any impact load and cartilage biomarker relationships in collegiate female basketball athletes. We hypothesized that high impact load and cumulative load would be associated with injury, measurable through select impact metrics and serum biomarkers, and may serve as indicators of injury risk.

Methods

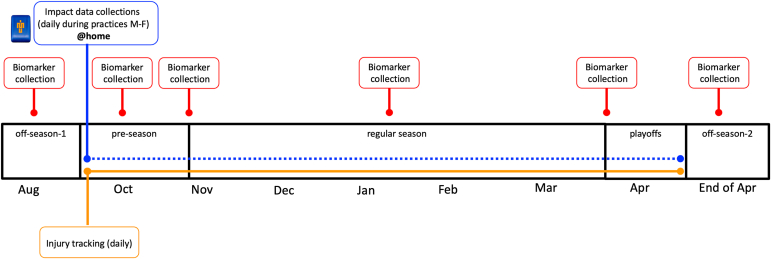

This was a preliminary, prospective longitudinal study evaluating lower-extremity impact load, serum cartilage biomarker monitoring, and injury incidence collection over the course of a single athletic season. Data were collected from August 2022 to April 2023. The nature of this study limited the ability to recruit more than a single women’s basketball team because of the number of wearable sensors available for use during the study duration. On the basis of previous epidemiologic work,32 we estimated 4.79 lower-extremity injuries per season for a team of 15 athletes. Information about this study was provided to 3 local universities that had a women’s varsity basketball team to gauge interest. After this recruitment period, a single women’s basketball team was formally recruited in July of 2022. Individuals were eligible if they were 18 to 25 years and actively part of the women’s varsity basketball team. Individuals were excluded if they were currently injured at the time of study initiation, those with a known history of anemia, individuals with a major fear of needle sticks or a history of fainting in response to blood draws, and individuals who weighed less than 110 pounds. These criteria were established to ensure the participants were representative of the typical athletic population and to mitigate any potential health risks or data-collection issues related to blood sampling. Figure 1 demonstrates the outcomes that were collected over the 2022-2023 season. Serum biomarkers of cartilage turnover were collected at 6 time points before, during, and after the 25 week season (off-season 1 [before week 1], preseason [during week 6], beginning of regular season play [during week 10], midpoint of the regular season [during week 18], before conference playoffs [during week 24], off-season 2 which occurred after cessation of NCAA tournament play [after week 25]). These time points were chosen to represent various phases of the athletic season and to ensure that we did not only evaluate a single period of the season, as this could bias results. Impact load metrics were collected daily during practices from preseason to cessation of play. Injury status was collected daily as reported by the team athletic trainer. Injury was defined as occurring as a result of participation in an organized practice or competition that required medical attention by a certified athletic trainer or physician resulted in a restriction of the student-athlete’s participation for 1 or more days beyond the day of initial injury.33 The injury location, diagnosis, severity, and time loss were recorded using the injury tracking software (PyraMed Health Systems, Berwyn, PA). Athletes who sustained lower-extremity injuries were retained in the study for us to monitor the influence of injury on our main outcome metrics. Only lower-extremity joint injuries were used for the final data analysis, as we assumed these would be most strongly related to the cartilage biomarkers. This study was approved by the university’s institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained before testing.

Fig 1.

This is a figure of the prospective, longitudinal study in a collegiate women’s basketball team over the course of the 2022-2023 season. The timeline depicts the frequency and timing of the serum blood draw collections, the daily collection of impact load metrics using the inertial measurement units, and the daily collection of injury status, recorded by the team athletic trainer.

Data Collection

Serum Biomarkers of Cartilage Turnover

We used 2 markers indicative of type II collagen and aggrecan synthesis (procollagen II carboxy propeptide [CPII] and aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope [CS846], respectively) and one marker of type II only collagen degradation (collagen type II cleavage [C2C]). These biomarkers were selected on the basis of a previous study26 that demonstrated preinjury differences in these markers in military cadets who went on to sustain ACL injury. Further, these biomarkers are indicative of type II collagen and aggrecan metabolism, proteins that are abundantly present in articular cartilage and have been suggested by the OA Biomarkers Working Group as appropriate markers for evaluating post-traumatic OA, indicators of poor joint health.34 CPII levels have been found to directly correlate with the synthesis of type II collagen,35 whereas CS846 has been reported as highly concentrated in human fetal cartilage and primarily absent in healthy, adult articular cartilage.28 However, the presence of CS846 has been identified in osteoarthritic cartilage, and there is work to support a significant increase in CS846 content after joint injury.36

For each of the biomarker collection time points (6 collection points per subject, see Fig 1) an ∼10 mL total blood sample, drawn in the morning, was obtained from each participant through an intravenous antecubital blood draw into a standard collecting tube and immediately processed. Serum aliquots were frozen and stored frozen at –80°C to be thawed for future batch processing. Each sample was labeled with the subject’s study number.

Tibial Impact Load Metrics Collection

Before the start of each practice, all participants had an IMU device (42 × 27 × 11; 9.5 g) affixed to both legs to obtain lower-extremity impact (tibial acceleration) data.20 The IMUs (Blue Thunder IMUs; IMeasureU, Auckland, New Zealand) contain a dual-g tri-axial accelerometer, gyroscope, and magnetometer. The device was secured to the distal medial tibia, just above the medial malleolus of both legs using a custom silicone Velcro strap.37 The IMUs were sampled continuously during all practices, and all data were stored on-board of the IMU at 1000 Hz. After each practice, the data onboard the IMUs were uploaded to the IMeasureU web portal (IMU Step, Auckland, New Zealand).

Data Reduction

Serum Biomarkers of Cartilage Turnover

Aliquots of sera were assayed in duplicate for biomarkers of collagen turnover and metabolism (CPII, CS846, C2C) through commercially available 96-well, precoated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (IBEX, Pharmaceuticals, Montréal, Quebec, Canada) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits for each biomarker were from the same respective lot numbers to further minimize interassay coefficients of variation (CV) and assays for each individual subject were performed at the same time to minimize the potential effect of multiple freeze/thaw cycles. A multilabel plate reader was used to detect serum absorbances for each cartilage turnover marker at an optical density of 450 nm. Serum concentrations were determined against the known standard curve provided by the manufacturer by using Prism GraphPad Software, version 9 (GraphPad, Boston, MA) to plot the mean standard absorbance readings on the y-axis versus log concentration on the x-axis using a logistic equation (4 parameters). This process was performed by the same member of the research team. Intra-assay CVs ranged from 5.02% to 6.51%; interassay CVs ranged from 6.91% to 9.66%. In addition to the determined serum concentrations, we also calculated cartilage degradation to cartilage synthesis (C2C:CPII) ratios to represent cartilage turnover. This was done by dividing the cartilage degradation levels by the cartilage synthesis levels at each of the 6-blood draw timepoints.

Tibial Impact Load Metrics

Metrics obtained from IMU Step software included a cumulative bone stimulus metric, impact load (tibial acceleration), total number of steps, impact intensity (high, medium, low), and impact asymmetry. Cumulative bone stimulus is a proprietary calculation performed by the IMU Step software and is an estimate of the mechanical stimulus that would cause the bone to respond and remodel.38 Cumulative bone stimulus is a unitless metric calculated by taking the peak resultant acceleration (impact) from every foot contact with the ground, throughout the duration of the session (practice) will be calculated and input into Equation 1, where k = number of loading conditions/activities, nj = number of impacts or loading cycles per loading condition, σj = resultant peak tibial acceleration, and m is an empirical constant of 4 determined previously by Beaupre et al.39

| (Eq 1) |

It is important to note that cumulative bone stimulus does not equate to the physiological intensity of a particular session or period of time but represents the mechanical stimulus that will lead to changes in bone remodeling.38 The cumulative bone stimulus metric reaches a plateau after a certain number of cycles/steps, indicating that continued mechanical stimulation has a limiting influence on bone response. Impact load (i.e., tibial acceleration) is a unitless metric that is a surrogate of the impact load that is experienced by the tibia during running and court-based activities.38 Impact load is calculated by multiplying the number of steps by the peak tibial acceleration value (force exerted by gravity, g) at which they are taken.

| (Eq 2) |

For both impact intensity and impact asymmetry metrics, IMU Step continuously bins the number of steps or impacts based on tibial acceleration values (ranging from 1 to 200 g+). These bins were categorized into high (21-200 +g), medium (6-20 g), and low (0-5 g) intensity. Output metrics (cumulative bone stimulus, number of steps within each intensity bin, impact asymmetry value by intensity bin) were calculated over the week before any documented injury and blood draws for analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Because of the nature of this preliminary study, results are reported both descriptively along with correlation analyses. Statistics were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and an a priori alpha level of 0.05 was used for all analyses. Weeks of the season were denoted numerically, beginning with the first preparatory season practices in September and encompassed data from Sunday to Saturday. Point biserial correlations were used to determine whether injury incidence was associated with impact load metrics taken over the week before the injury occurring. Pearson product moment correlation analyses were used to assess the relationship between impact load metrics averaged over the week before blood draws with cartilage biomarker levels and whether the total number of lower-extremity joint injuries sustained was associated with cartilage biomarker levels. Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality were performed to assess the normality of the data. In the presence of any non-normally distributed data, Spearman rho correlations were performed and reported. Descriptive analyses of median (minimum, maximum) cartilage synthesis and degradation levels and impact load metric values across the entire basketball season were conducted to provide a visual depiction of fluctuations in these metrics.

Results

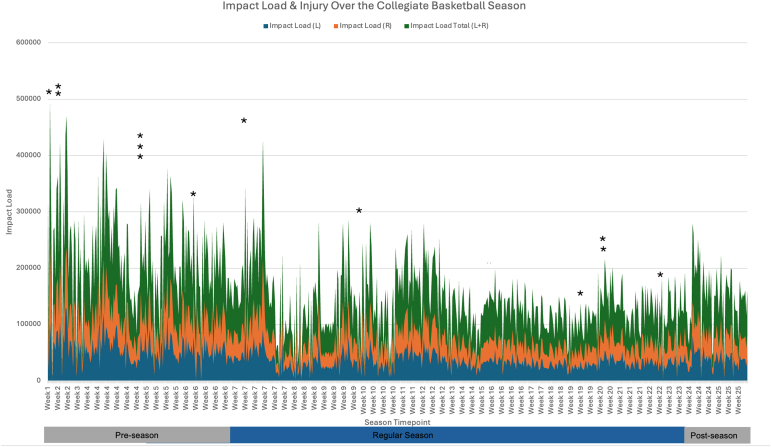

Thirteen collegiate women’s basketball athletes from a local university were initially recruited. Two of the 13 athletes were excluded because of their age and current injury status. Eleven athletes (mean values: height: 1.86 meters, mass: 82.0 kg, age: 20.54 years) were included. Descriptive data and information regarding participant demographics, season long statistics, and injury-related data can be found in Table 1. Injuries reported by the athletic trainer occurred both during practices (n = 10) and competitive regular season games (n = 3). A descriptive graph of impact load for the left, right, and combined limb values and injury incidence is plotted over time in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Study Information

| Outcome | Collegiate Female Basketball Athletes (n = 11) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 20.54 ± 1.96 (18-24) |

| Height, m | 1.86 ± 0.067 (1.75-1.95) |

| Mass, kg | 82.0 ± 10.32 (67.57-101.13) |

| Dominant limb | Right limb (11), left (0) |

| Previous injury (self-reported)∗ | Anterior cruciate ligament tear (n = 4) |

| Medial collateral ligament tear (n = 1) | |

| Lateral collateral ligament tear (n = 1) | |

| Meniscal tear (n = 1) | |

| Shin splints (n = 1) | |

| Ankle sprain (n = 8, [7 bilateral]) | |

| Torn acetabular labrum (n = 1) | |

| Patellar instability (n = 2) | |

| 2022-2023 season injuries | Lateral ankle sprain (n = 10) |

| Medial collateral ligament (n = 1) | |

| Tibiofemoral cartilage lesion (n = 1) | |

| Patellar dislocation (n = 1) | |

| Number of athletes injured and number of injuries per athlete | 7 athletes; 1 athlete (4 injuries), 1 athlete (3 injuries) 5 athletes (1 injury) |

| Past sports played (besides basketball) | Soccer, lacrosse, volleyball, swimming, field hockey, handball, track and field |

| Season impact load (unitless) | |

| Left | 33,649.52 ± 9,754.61 |

| Right | 32,766.58 ± 8,385.23 |

| Season cumulative bone stimulus (unitless) | |

| Left | 264.84 ± 12.72 |

| Right | 265.16 ± 12.53 |

| Step count (no. steps) | |

| Left | 2,557.62 ± 473.57 |

| Right | 2,559.59 ± 465.21 |

| Impact asymmetry (L-R) (no. steps) | –0.811 ± 3.037 |

| CPII levels, ng/mL | 789.66 ± 199.51 |

| CS846 levels, ng/mL | 27.24 ± 37.35 |

| C2C levels, ng/mL | 114.35 ± 19.87 |

NOTE. Outcome data represented as mean ± standard deviation (range).

C2C, collagen type II cleavage; CPII, procollagen II carboxy propeptide; CS846, aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope; L, left; R, right.

prior to 2022 season

Fig 2.

Shown are the variations in impact load, a unitless metric that is a surrogate of the impact load that is experienced by the tibia during court-based activities, for left (L), right (R) and both limbs (L+R) over the course of a 25-week collegiate women’s basketball season. This figure also denotes with asterisks when a lower-extremity joint injury occurred during the season.

Injury and Cumulative Impact Loading

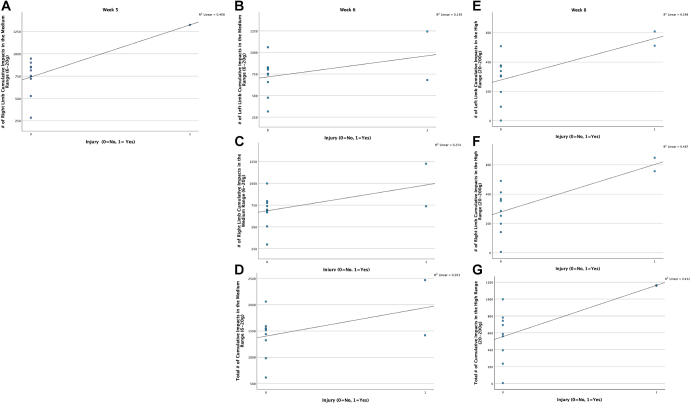

There was a statistically significant relationship between injury incidence and the cumulative number of medium-intensity (6-20 g’s) and high-intensity (21-200 +g) impacts over the preceding week (Fig 3). Greater medium-range (6-20 g’s) cumulative impact intensities during week 5 (preseason) for the right limb (r = 0.631, P = .037), and during week 6 (preseason) for left limb (r = 0.609, P = .047), right limb (r = 0.711, P = .014), and both limbs (r = 0.674, P = .023) were moderately associated with lower-extremity injury. Greater cumulative high-intensity impacts (21-200 g’s) during week 8 (regular season) for the left limb (r = 0.631, P = .037), right limb (r = 0.698, P = .017), and both limbs (0.672, P = .024) were also moderately associated with lower-extremity injury. There was no significant association between season averages for the number of high-intensity (r = 0.183, P =.569), medium-intensity (r = –0.010, P =.975), and low-intensity (r = 0.118, P =.715) asymmetry values with the total number of injuries sustained during the season. There were no other significant associations between impact loading variables and injury across weeks 1-4, 7, 9-10, and 11-25, (P > .05).

Fig 3.

Shown are a series of scatterplots (a-g) that visualize the statistically significant point biserial correlations for the right, left, and both limbs (total) that were observed during week 5 (preseason), week 6 (preseason), and week 8 (regular season) between the number of medium and high impacts taken over the course of those weeks and subsequent lower-extremity injury occurrence. The R2 value is also listed in the upper right-hand corner of the scatter plots.

Cartilage Serum Biomarkers and Cumulative Impact Loading

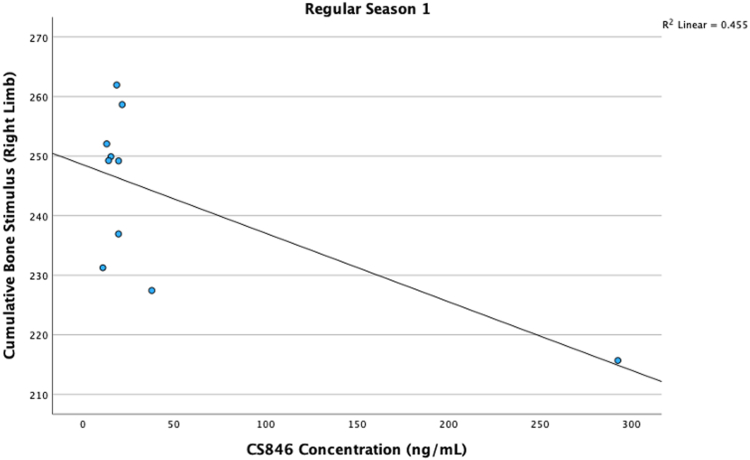

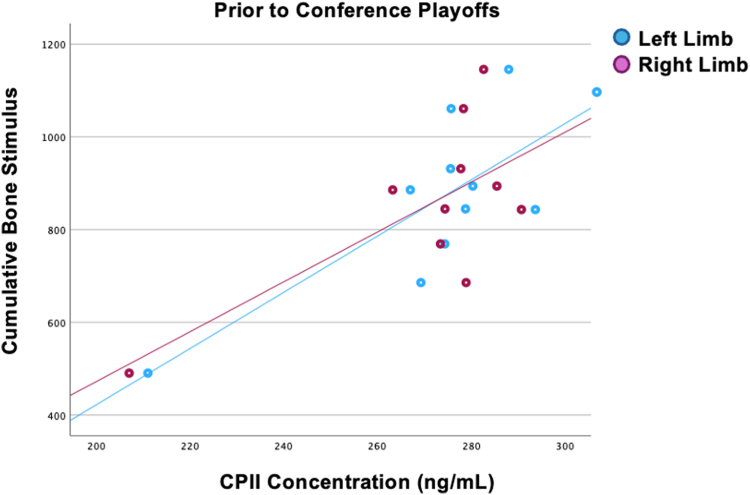

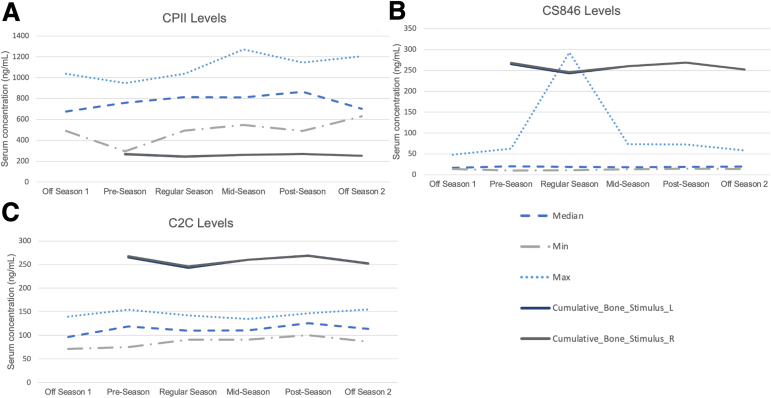

Greater CS846 levels at the start of the regular season were moderately associated with lower cumulative bone stimulus in the right limb (rho = –0.675, P =.032) (Fig 4). Greater cumulative bone stimulus was moderately associated with increased CPII levels before conference playoffs for right (r = 0.694, P = .026) and left (r = 0.747, P = .013) limbs (Fig 5). There were no other significant associations between CS846, CPII, or C2C and cumulative bone stimulus for either limb at any of the other timepoints, P > .05. Descriptive plots for cartilage synthesis and degradation levels and average cumulative bone stimulus values can be found in Figure 6 A-C to provide a visual depiction of fluctuations in these metrics.

Fig 4.

Scatterplot is shown that represents the correlation between greater levels of aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope (CS846) and lower levels of cumulative bone stimulus of the right limb at the regular season 1 (start of the regular season) timepoint. An R2 value is also listed in the upper right-hand corner of the scatter plots.

Fig 5.

Scatterplot is shown that depicts the relationship between increased procollagen II carboxy propeptide (CPII) levels and increased cumulative bone stimulus of both the left and right limbs before conference playoffs time point.

Fig 6.

Shown are the minimum, maximum and median cartilage biomarker levels (a-c) and mean cumulative bone stimulus of the left (L) and right (R) limb over the duration of a 25-week collegiate women’s basketball season. Cumulative bone stimulus is a unitless metric calculated by taking the peak resultant acceleration (impact) from every foot contact with the ground throughout the duration of the session (practice). Fluctuations in the serum biomarker concentrations of procollagen II carboxy propeptide (CPII), aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope (CS846), and collagen type II cleavage (C2C) concentrations, presented as nanograms per milliliter, are represented at each of the 6 study time points (off-season 1, preseason, regular season 1, regular season 2 [midpoint of regular season], before conference playoffs, off-season 2 [after cessation of National Collegiate Athletic Association play]).

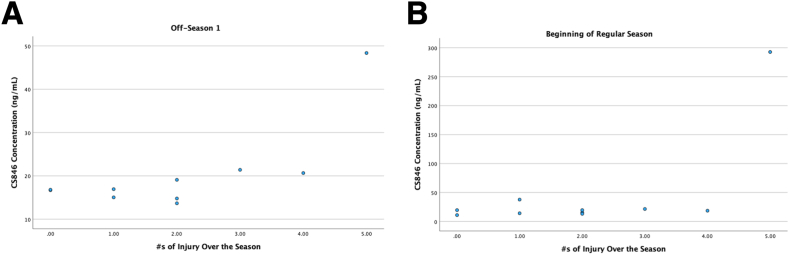

Cartilage Serum Biomarkers and Injury

Greater CS846 levels before the start of the formal basketball activities (offseason 1) (rho = 0.729, P = .017) and at the start of the regular season (rho = 0.645, P = .044) were moderately associated with the occurrence of injury (Fig 7). There were no other significant associations between CS846 and injury at the other 4 time points. There were also no significant associations for CPII and C2C and injury at any of the 6 time points, P > .05. There were no significant associations between C2C:CPII ratios and injury incidence at offseason 1 (r = 0.240, P = .505), preseason (r = –0.184, P = .611), regular season 1 (0.184, P = .611), regular season 2, midpoint of the season (r = –0.191, P = .597), prior to conference playoffs (r = 0.172, P = .634), and off-season 2, just following cessation of NCAA play (0.031, P = .931).

Fig 7.

Shown are 2 scatterplots (a-b) that depict the small relationship between greater levels of aggrecan chondroitin sulfate 846 epitope (CS846) and the season-long injury incidence (i.e., greater number of injuries sustained over the season) at both the off-season 1 and beginning of the regular season time points.

Discussion

In this study, we found that over the course of a women’s collegiate basketball season, a greater number of more intense impacts early in the season was associated with subsequent injury and increased cartilage synthesis at various time points was correlated to increased cumulative bone stimulus metrics and season-long injury incidence. Specifically, during the preseason and early regular season, we observed that lower-extremity joint injury was associated with sustaining a greater number of medium-intensity (6-20 g’s) and high-intensity (21-200 g’s) impacts over the week before the injury occurred (Fig 3). On the basis of previous research,3,11 excessive impact loading and poor biomechanical movement patterns12, 13, 14, 15 can contribute to lower-extremity injury risk.9,16 Further, research related to training load in athletes has identified a relationship between greater intensity and injury.40 The findings of our study are in line with previous research suggesting that the volume of intense impact load during practices and games may be of importance.41, 42, 43 We did not observe any similar relationship between the number of medium/high impacts and injury during the later weeks of the season. This may be because during the preseason and beginning of regular season competition, there is less frequent and intense game play, and thus practices may be more intense and voluminous. Later in the season, we would expect practice intensities to be lower and game intensities to be greater. Because we did not measure impact load during game play, we cannot speak directly to whether this relationship would hold; however, we hypothesize it may have impacted the findings of this study.

We also observed that at the beginning of the regular season, a greater level of cartilage synthesis (CS846 concentration) was associated with lower cumulative bone stimulus values (Fig 4), and at the end of the season, a greater level of cartilage synthesis (CPII concentration) was associated with greater cumulative bone stimulus (Fig 5). Lastly, we observed that greater cartilage synthesis levels of CS846 before the start of basketball activities and early during the regular season were associated with subsequent lower-extremity joint injury (Fig 7). Although we saw statistically significant associations, we cannot discount that these associations may have been a cause of chance findings or Type I errors. The results of this work must be taken considering the number of correlations that were performed over the duration of the athletic season. Furthermore, this work is just a small sample of preliminary findings that highlight the potential relationship between cartilage biomarkers, impact load, and injury in female collegiate basketball athletes; larger studies are needed to speak to the clinical applicability of such findings.

Cumulative bone stimulus, an impact load metric derivative that estimates the mechanical stimulus experienced by the tibia, was only associated with fluctuations in cartilage synthesis markers, CS846 and CPII, at 2 of the 6 seasons blood draw time points. We observed that at the beginning of the regular season, a greater level of CS846, a marker indicative of aggrecan synthesis, was moderately associated with lower cumulative bone stimulus (Fig 4). On the basis of how the cumulative bone stimulus metric is calculated and the metric’s natural trend to increase and then plateau on the basis of an external stimulus, it is not surprising that we observed lower cumulative bone stimulus during the preseason period before the start of regular season basketball activities. However, we did not expect to observe this relationship with greater CS846 levels during this period. Further before conference playoffs, we conversely observed that greater levels of CPII (synthesis) were associated with an increase in cumulative bone stimulus (Fig 5). We also observed that CS846 at the off-season 1 time point and the beginning of the regular season was associated with season-long injury incidence.

Although CS846 and CPII are both markers that indicate relative cartilage synthesis, there is various agreement among previous studies supporting their fluctuations. For example, greater CS846 levels have been observed in patients with OA.44,45 Although our population of athletes was healthy, with no known active joint injuries at the time the study began, many of the athletes had sustained previous, significant joint injuries, including several ACL ruptures and collateral ligament damage. ACL injuries and subsequent reconstructions have been strongly reported to increase the development of posttraumatic OA.30 Those who sustain a traumatic knee injury are 5 times more likely to develop posttraumatic OA,9 and upwards of 50% of young athletes who sustain ACL injuries will develop posttraumatic OA within 10 to 20 years.46, 47, 48 As increased CS846 has been reported in osteoarthritic knees, it is plausible that increases in this biomarker observed during the beginning of the regular season, before increased competitive season game play, were a result of potentially early underlying metabolic and osteoarthritic changes in these knee joints. However, because of the peak change early in the preseason to early season progression and the high impact load values during preseason and early regular season, we feel this may be related to “preseason” ramp up and a direct response of the body to load changes. Furthermore, this cartilage synthesis marker is also markedly increased in content after joint injury.37 In this study, 13 lower-extremity joint injuries (10 ankle, 3 knee; Table 1) were sustained across the duration of the season, both during practices and games. Similarly, increased CPII levels before conference playoffs in this study may be the result of increased load sustained by these athletes during this period of the season. Further, increases in CPII levels have been associated with an increased risk of sustaining future ACL injury in military cadets27; therefore, it is plausible the increases observed in CPII and relationship to increased cumulative bone stimulus metrics may indicate a precursor to injury in this population. Hypothetically, we would have also expected to observe a similar relationship with CS846 at this time point, but any lack of association may be due to a multitude of factors such as varying physiological differences between the participants as well as the small sample size. Regardless, these findings suggest that the cumulative bone stimulus fluctuations experienced throughout the season may have implications for cartilage health, influencing biochemical markers associated with collagen synthesis and future injury risk. The correlation between increased cartilage synthesis at various time points and cumulative bone stimulus metrics further supports the possible interplay between mechanical loading and biological responses.

The preliminary findings of this study suggest that variations in cartilage metabolism, specifically cartilage synthesis, as indicated by CS846 levels and CPII, as well as cumulative bone stimulus metrics during specific timepoints may serve as potential predictors of injury susceptibility. Although there were numerous nonstatistically significant associations between cartilage markers, impact load, and injury, we did observe a small association between elevations in CS846 and injury incidence in this population. These initial study findings emphasize the importance of considering preseason and early-season biomarkers in potentially identifying athletes at risk for season-long injuries. Future studies should also further evaluate whether impact load metrics are more related to injury or cartilage biomarkers to strengthen the supporting evidence of these preliminary relationships. Understanding these relationships could help to inform injury prevention strategies and training interventions tailored to mitigate the risk associated with specific loading patterns, particularly the number of medium and high intensity impacts during early phases of athletic seasons. However, these relationships should be further evaluated in larger cohorts to determine actual predictive capabilities.

Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of our study. This was an exploratory study in a single collegiate female basketball team, where impact load was only captured during practices, and not competitions. Although IMUs can provide a surrogate of tibial acceleration and load, it cannot assess abnormal joint loading or kinematics such as increased valgus or external rotation. Within some of the scatterplots, it is clear that there are a few individuals whose results may be driving the relationship. Although we acknowledge this potential, this goal of this study was to evaluate biomarker fluctuations, impact load, and injury in this sample; thus, removing individuals who reflected these levels of load or cartilage biomarkers would limit the ability to interpret the findings. These findings cannot be applied to other populations, and future research should consider conducting similar evaluations in men’s and in youth basketball. In addition, there are several known (previous history of injury) and unknown confounders in this study. For example, several athletes had previously sustained traumatic joint injuries, including several ACL injuries. It is possible that elevations in cartilage metabolism biomarkers were affected by these past injuries. In addition, we did not account for upper extremity or trunk-related injuries and as serum cartilage biomarkers are a systemic estimate of circulating levels, this needs to be considered. On the basis of the upper-extremity injuries sustained over the season (nose contusion, rib contusion, finger fracture, forehead laceration and concussion, rotator cuff tendinitis) we felt it was reasonable to only discuss the results in the context of lower-extremity injuries.

Conclusions

This study investigates impact load, cartilage biomarkers, and lower-extremity joint injuries in collegiate female basketball players across a season. The findings demonstrate that more moderate- to high-impact intensities (6-200 g) early in the season were associated with subsequent injury. Increased cartilage synthesis (CS846, CPII) at various time points was also correlated with increased cumulative bone stimulus metrics and season-long injury incidence.

Disclosures

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: J.P.B. reports financial support was provided by the Arthroscopy Association of North America. C.M.E. reports financial support was provided by the Arthroscopy Association of North America. C.L. reports financial support was provided by the Arthroscopy Association of North America. All other authors (M.S., J.S., M.M., M.V.D., J.F.) declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the collaboration and support of the UConn Sports Medicine and Athletics Department(s), including Robert Howard, Andrea Hudy and Dr. Matthew Hall. This study was made possible by their dedication to advancing the field of sports medicine and care of student athletes.

References

- 1.National Federation of State High School Associations 2018-19 High School Athletics Participation Survey. https://www.nfhs.org/media/1020406/2018-19-participation-survey.pdf

- 2.NCAA Sports Sponsorship and Participation Rates Report: National Collegiate Athletics Association; 2018-2019. https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/research/sportpart/201819RES_SportsSponsorshipParticipationRatesReport.pdf

- 3.Hewett T.E., Myer G.D., Ford K.R., et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: A prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:492–501. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis I.S., Bowser B.J., Mullineaux D.R. Greater vertical impact loading in female runners with medically diagnosed injuries: A prospective investigation. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:887–892. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith B.E., Selfe J., Thacker D., et al. Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khodaee M., Currie D.W., Asif I.M., Comstock R.D. Nine-year study of US high school soccer injuries: Data from a national sports injury surveillance programme. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:185–193. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Svoboda S.J. ACL injury and posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Clin Sports Med. 2014;33:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bodkin S.G., Werner B.C., Slater L.V., Hart J.M. Post-traumatic osteoarthritis diagnosed within 5 years following ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2020;28:790–796. doi: 10.1007/s00167-019-05461-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas A.C., Hubbard-Turner T., Wikstrom E.A., Palmieri-Smith R.M. Epidemiology of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. J Athl Train. 2017;52:491–496. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.5.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wikstrom E.A., Song K., Migel K., Hass C.J. Altered vertical ground reaction force components while walking in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Inte J Athletic Therapy Training. 2020;25:27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bigouette J., Simon J., Liu K., Docherty C.L. Altered vertical ground reaction forces in participants with chronic ankle instability while running. J Athl Train. 2016;51:682–687. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.11.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Besier T.F., Lloyd D.G., Cochrane J.L., Ackland T.R. External loading of the knee joint during running and cutting maneuvers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1168–1175. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boden B.P., Dean G.S., Feagin J.A., Jr., Garrett W.E., Jr. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000;23:573–578. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20000601-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffin L.Y., Albohm M.J., Arendt E.A., et al. Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: A review of the Hunt Valley II meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1512–1532. doi: 10.1177/0363546506286866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaeding C.C., Leger-St-Jean B., Magnussen R.A. Epidemiology and diagnosis of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Clin Sports Med. 2017;36:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taga I., Shino K., Inoue M., Nakata K., Maeda A. Articular cartilage lesions in ankles with lateral ligament injury. An arthroscopic study. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:120–126. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100120. discussion 126-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiernan D., Hawkins D.A., Manoukian M.A.C., et al. Accelerometer-based prediction of running injury in National Collegiate Athletic Association track athletes. J Biomech. 2018;73:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller R.H., Edwards W.B., Brandon S.C., Morton A.M., Deluzio K.J. Why don't most runners get knee osteoarthritis? A case for per-unit-distance loads. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:572–579. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milner C.E., Ferber R., Pollard C.D., Hamill J., Davis I.S. Biomechanical factors associated with tibial stress fracture in female runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:323–328. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000183477.75808.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheerin K.R., Reid D., Besier T.F. The measurement of tibial acceleration in runners-A review of the factors that can affect tibial acceleration during running and evidence-based guidelines for its use. Gait Posture. 2019;67:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan M., Madden K., Burrus M.T., et al. Epidemiology and impact on performance of lower extremity stress injuries in professional basketball players. Sports Health. 2018;10:169–174. doi: 10.1177/1941738117738988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenforde A.S., Kraus E., Fredericson M. Bone stress injuries in runners. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016;27:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tenforde A.S., Sainani K.L., Carter Sayres L., Milgrom C., Fredericson M. Participation in ball sports may represent a prehabilitation strategy to prevent future stress fractures and promote bone health in young athletes. PM R. 2015;7:222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross T.S., Nelson R.C. The shock attenuation role of the ankle during landing from a vertical jump. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20:506–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milgrom C., Finestone A., Simkin A., et al. In-vivo strain measurements to evaluate the strengthening potential of exercises on the tibial bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:591–594. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.82b4.9677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svoboda S.J., Owens B.D., Harvey T.M., Tarwater P.M., Brechue W.F., Cameron K.L. The association between serum biomarkers of collagen turnover and subsequent anterior cruciate ligament rupture. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1687–1693. doi: 10.1177/0363546516640515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svoboda S.J., Harvey T.M., Owens B.D., Brechue W.F., Tarwater P.M., Cameron K.L. Changes in serum biomarkers of cartilage turnover after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:2108–2116. doi: 10.1177/0363546513494180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glant T.T., Mikecz K., Roughley P.J., Buzas E., Poole A.R. Age-related changes in protein-related epitopes of human articular-cartilage proteoglycans. Biochem J. 1986;236:71–75. doi: 10.1042/bj2360071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Catterall J.B., Stabler T.V., Flannery C.R., Kraus V.B. Changes in serum and synovial fluid biomarkers after acute injury (NCT00332254) Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R229. doi: 10.1186/ar3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harkey M.S., Luc B.A., Golightly Y.M., et al. Osteoarthritis-related biomarkers following anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction: A systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazor M., Best T.M., Cesaro A., Lespessailles E., Toumi H. Osteoarthritis biomarker responses and cartilage adaptation to exercise: A review of animal and human models. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019;29:1072–1082. doi: 10.1111/sms.13435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clifton D.R., Hertel J., Onate J.A., et al. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance: Descriptive epidemiology of injuries in US high school girls' basketball (2005-2006 through 2013-2014) and National Collegiate Athletic Association women's basketball (2004-2005 through 2013-2014) J Athl Train. 2018;53:1037–1048. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-150-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiStefano L.J., Dann C.L., Chang C.J., et al. The first decade of web-based sports injury surveillance: descriptive epidemiology of injuries in US high school girls' soccer (2005-2006 through 2013-2014) and National Collegiate Athletic Association women's soccer (2004-2005 through 2013-2014) J Athl Train. 2018;53:880–892. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-156-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraus V.B., Burnett B., Coindreau J., et al. Application of biomarkers in the development of drugs intended for the treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2011;19:515–542. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nelson F., Dahlberg L., Laverty S., et al. Evidence for altered synthesis of type II collagen in patients with osteoarthritis. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:2115–2125. doi: 10.1172/JCI4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lohmander L.S., Ionescu M., Jugessur H., Poole A.R. Changes in joint cartilage aggrecan after knee injury and in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:534–544. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<534::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson C.D., Outerleys J., Tenforde A.S., Davis I.S. A comparison of attachment methods of skin mounted inertial measurement units on tibial accelerations. J Biomech. 2020;113 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2020.110118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Besier T.F. Bone stimulus: Summary and applications. IMeasureU Research Articles. 2019 https://imeasureu.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/IMU_Bone_Stimulus.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beaupre G.S., Orr T.E., Carter D.R. An approach for time-dependent bone modeling and remodeling-application: A preliminary remodeling simulation. J Orthop Res. 1990;8:662–670. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eckard T.G., Padua D.A., Hearn D.W., Pexa B.S., Frank B.S. The relationship between training load and injury in athletes: A systematic review. Sports Med. 2018;48:1929–1961. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0951-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piedra A., Peña J., Ciavattini V., Caparrós T. Relationship between injury risk, workload, and rate of perceived exertion in professional women’s basketball. Apunts Sports Med. 2020;55:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towner R., Larson A., Gao Y., Ransdell L.B. Longitudinal monitoring of workloads in women's Division I (DI) collegiate basketball across four training periods. Front Sports Act Living. 2023;5 doi: 10.3389/fspor.2023.1108965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewis M. It's a hard-knock life: Game load, fatigue, and injury risk in the national basketball association. J Athl Train. 2018;53:503–509. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-243-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hunter D.J., Li J., LaValley M., et al. Cartilage markers and their association with cartilage loss on magnetic resonance imaging in knee osteoarthritis: The Boston Osteoarthritis Knee Study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9 doi: 10.1186/ar2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burland J.P., Hunt E.R., Lattermann C. Serum biomarkers in healthy, injured, and osteoarthritic knees: a critical review. J Cartilage Joint Preserv. 2023;3 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mather R.C., 3rd, Koenig L., Kocher M.S., et al. Societal and economic impact of anterior cruciate ligament tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:1751–1759. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roos E.M. Joint injury causes knee osteoarthritis in young adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17:195–200. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000151406.64393.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lohmander L.S., Englund P.M., Dahl L.L., Roos E.M. The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: Osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1756–1769. doi: 10.1177/0363546507307396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]