Abstract

Background

Smoking prevalence among U.S. adults experiencing homelessness is ≥70 %. Interventions are needed to address persisting tobacco disparities.

Methods

Adults who smoked combustible cigarettes (CC) daily (N=60) were recruited from an urban day shelter and randomly assigned to an e-cigarette switching intervention with or without financial incentives for carbon monoxide (CO)-verified CC abstinence (EC vs. EC+FI). All participants received an e-cigarette device and nicotine pods during the first 4 weeks post-switch; and those in the EC+FI group also received escalating weekly incentives for CC abstinence during the same period. Key follow-ups were conducted at 4- and 8-weeks post-switch.

Results

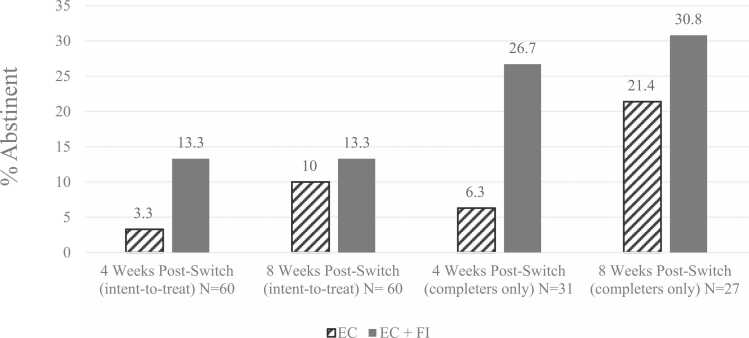

Participants were predominantly male (75 %), 50 % were racially/ethnically minoritized, with an average age of 48.8 years. Descriptive analyses indicated that CC smoking abstinence rates among EC and EC+FI were 3.3 % vs. 13.3 % at 4 weeks (8.3 % overall) and 10.0 % vs. 13.3 % at 8 weeks (11.7 % overall) in the intent-to-treat analyses (missing considered smoking). Among those who completed follow-ups (51.7 % and 45.0 % at 4- and 8-weeks), CC abstinence rates in EC and EC+FI were 6.3 % vs. 26.7 % at 4 weeks (16.1 % overall) and 21.4 % vs. 30.8 % at 8 weeks (25.9 % overall). EC+FI participants reported fewer days of smoking, more days of e-cigarette use, and greater reductions in CO at 4-week follow-up. Most participants reported a high likelihood of switching to e-cigarettes (67.7 %).

Conclusion

E-cigarette switching with financial incentives for CC cessation is a promising approach to tobacco harm reduction among adults accessing shelter services. Refinements are needed to improve engagement.

Keywords: Smoking cessation, Homelessness, E-cigarette switching, Financial incentives, Tobacco harm reduction, Combustible cigarette abstinence

Highlights

-

•

The feasibility of e-cigarette switching was evaluated at an urban shelter.

-

•

Interventions were delivered with and without incentives for cigarette cessation.

-

•

Early cigarette cessation was greater when cessation was incentivized.

-

•

Exclusive e-cigarette use was greater when cigarette cessation was incentivized.

-

•

E-cigarette use remained high regardless of incentives.

1. Introduction

Although adult smoking prevalence has declined to 11.5 % in the U.S. overall,(Cornelius, 2023) the prevalence of smoking is much higher among adults experiencing homelessness (70 %).(Baggett and Rigotti, 2010; Boozary et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2022; Taylor et al., 2016) Numerous studies have shown that lower socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with a reduced likelihood of smoking cessation,(Businelle et al., 2010, Kendzor et al., 2010, Kendzor et al., 2020, Kendzor et al., 2012, Wetter et al., 2005) despite a similar number of cessation attempts between individuals of lower and higher SES(Kotz and West, 2009). Not surprisingly, socioeconomic disadvantage is linked with greater tobacco-related cancer incidence and mortality(Singh and Jemal, 2017). Although standard cessation approaches are helpful for many,(Fiore et al., 2008) alternative strategies may benefit those who are unable to quit following traditional evidence-based treatment recommendations.

There is substantial evidence that offering financial incentives for smoking abstinence is an effective approach to promoting smoking cessation in a variety of challenging populations,(Notley et al., 2019) and several studies have focused specifically on adults experiencing homelessness(Baggett et al., 2018; Businelle et al., 2010; Molina et al., 2022; Rash, Petry, and Alessi, 2018; Wilson et al., 2023). Incentive-based interventions (contingency management) employ behavioral principles and operant conditioning, and they use positive reinforcement to increase the likelihood that desired behaviors or outcomes will recur(Petry et al., 2017; Rash, Stitzer, and Weinstock, 2017). Notably, past research has demonstrated that contingency management interventions for smoking cessation dramatically increase cessation rates(Notley et al., 2019), including among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults(Businelle et al., 2014; Kendzor et al., 2024; Kendzor et al., 2015). Nevertheless, the majority of those who try to quit ultimately return to smoking.

Switching from combustible cigarettes (CCs) to electronic cigarettes (i.e., e-cigarettes) is a practical strategy that may reduce harm for those who have been unable to quit or who are uninterested in quitting smoking,(Abrams et al., 2018, Fairchild et al., 2018, Kendzor et al., 2024, Levy et al., 2017) especially for groups with a high smoking prevalence and a low likelihood of cessation. Although not without harm,(Anderson et al., 2016, Clapp et al., 2017, Ghosh et al., 2018, Hajek et al., 2019, Omaiye et al., 2019, Ratajczak et al., 2018) e-cigarette use is associated with far fewer carcinogenic and other harmful exposures than CCs (Abrams et al., 2018; Hajek et al., 2014; Margham et al., 2016; Ratajczak et al., 2018; Reilly et al., 2019; Shahab and Goniewicz, 2017; Talih et al., 2019; Wagener et al., 2017). In addition, evidence from randomized trials suggests that the use of e-cigarettes is associated with similar or higher CC cessation rates relative to traditional forms of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)(Bullen et al., 2013; Hajek, Phillips-Waller, Przulj, Pesola, Myers Smith, et al., 2019; Hajek, Phillips-Waller, Przulj, Pesola, Smith, et al., 2019; Hartmann-Boyce et al., 2022; Hatsukami et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022). Likewise, findings from large survey studies have shown that daily e-cigarette use is associated with previous smoking cessation, (Farsalinos and Barbouni, 2020; Farsalinos and Niaura, 2020) suggesting that some people who smoke may use e-cigarettes as a means to quit CCs.

Although little is known about the utility of e-cigarettes for harm reduction among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults overall, initial research has demonstrated the feasibility of using e-cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy among adults experiencing homelessness(Collins et al., 2019; Dawkins et al., 2020; Scheibein et al., 2020). Plausibly, switching from CCs to e-cigarettes has the potential to benefit groups who experience high rates of smoking and low rates of smoking cessation. Incentivizing CC abstinence in the context of a switching intervention is a novel and potentially powerful harm-reduction strategy. Thus, the current study examined the feasibility and potential impact of an e-cigarette switching intervention, with and without financial incentives for CC cigarette abstinence, on CC cessation and tobacco product use. The primary aims of the study were to determine whether e-cigarette switching is a useful tobacco harm reduction approach among adults accessing shelter services, and to evaluate whether the addition of financial incentives for CC abstinence might enhance the potential efficacy of the switching intervention.

2. Method

2.1. Overview

A total of 60 adults were randomly assigned to one of two e-cigarette switching interventions: 1) e-cigarette switching (EC) or 2) e-cigarette switching + small financial incentives for carbon monoxide (CO) verified CC abstinence (FI + EC). Participants were followed weekly from one week prior to a scheduled e-cigarette switch date (pre-switch) through four weeks post-switch date (intervention phase), with a final follow up 8-weeks after the switch date (post-intervention). Regardless of treatment group assignment, participants received $20 compensation via reloadable study credit card for a carbon monoxide (CO) breath sample and the completion of weekly tablet-based surveys from 1 week pre-switch through 4 weeks post-switch (6 assessments total; up to $120 in possible earnings), and $50 for completion of the final 8-week post-switch follow-up CO breath sample and survey assessment. All participants were provided with a disposable phone and a prepaid phone plan to enable communication with the study team. The primary outcomes were self-reported CC abstinence over the previous 7 days corroborated with CO verification at 4- and 8-week post-switch follow-ups. Secondary outcomes included changes in CO from baseline, reductions in days of CCs smoking, and continued e-cigarette use. E-cigarette use (without CC use), CC use (without e-cigarette use), dual use of e-cigarettes and CCs, and abstinence from both e-cigarettes and CCs was also tracked. Other feasibility outcomes included study retention, perceptions of the intervention, and incentive costs.

2.2. Recruitment/enrollment

Participants were recruited by study staff at the Homeless Alliance day shelter in Oklahoma City, OK. Study staff were stationed at a table in a large open area of the shelter where meals were served, and where guests could access computers and nearby office services. The staff provided information about the study, answered questions, and screened/enrolled interested individuals in an adjacent private office space. Participants were enrolled between September and December 2022. Final follow-ups were completed in February 2023.

2.3. Participants

Participants were eligible to take part in the study if they: 1) were ≥21 years of age 2) had an CO level ≥8 ppm suggestive of current smoking, 3) reported smoking ≥5 cigarettes per day, 4) were willing and able to attend study visits over 9 weeks, 5) expressed interest in switching from CCs to e-cigarettes, 6) were willing to abstain from smoking cannabis for the duration of the study, 7) were able to speak and understand English, 8) demonstrated >6th grade English literacy by earning a score ≥4 on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine-Short Form (REALM-SF;(Arozullah et al., 2007) required to complete tablet questionnaire items), 9) were able to read a 3-sentence selection from the consent form, and 10) were not pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. E-cigarette switching (EC)

At baseline (pre-switch), participants were provided with a Vuse pod-based e-cigarette device and offered 3 refill pods in their preferred flavor (Menthol or Golden Tobacco, 5 % nicotine concentration). Participants were encouraged to practice using the device over the subsequent week before they switched. Participants were advised to completely switch from CCs to the e-cigarette device one week after the baseline visit. On the switch date, they were supplied with refill pods based on their pre-switch CC smoking level (i.e., 1 pod per pack of cigarettes smoked per week), and the pods were replenished at each weekly visit through 4-weeks post-switch (intervention phase). Although participants in the EC group did not earn incentives for CC abstinence, they were yoked with a participant in the EC+FI group (described below), and they earned the same weekly incentive amount as their counterpart earned for CC abstinence credited to a reloadable study credit card. For example, if a participant in the EC + FI group did not earn an incentive during a particular week due to non-abstinence, their counterpart in the EC group would also not receive an incentive. As in other contingency management research,(Dallery et al., 2013, Hertzberg et al., 2013, Kendzor et al., 2022, Stoops et al., 2009, Wells et al., 2022) the yoked design was employed to equate potential earnings between the groups and promote comparable study engagement and attendance. All participants were scheduled for the same number of study visits and study assessments, and all participants were offered the same compensation for the completion of in-person study assessments.

2.4.2. E-cigarettes + financial incentives (EC+FI)

Participants assigned to the EC+FI group each received an e-cigarette device and pods and were instructed to switch from CCs to e-cigarettes as described above. In addition, participants also earned financial incentives for CC abstinence via credits to their reloadable study credit card. On the switch day, participants earned a $20 credit if they self-reported CC abstinence over the past 24 hours and had a CO level of ≤8 parts per million (ppm). The lenient 8 ppm threshold was chosen due to the recency of CC cessation. At each weekly visit during the treatment phase (from 1 to 4 weeks post-switch), participants earned incentives for self-reported CC abstinence over the past 7 days corroborated with a CO level ≤6 ppm. The amount of the incentives increased by $5 for each consecutive week where CC abstinence was confirmed. Thus, participants could earn $20-$40 incentives at each visit (up to $150 total over 5 visits). Participants who reported CC use over the past 7 days and/or had a CO level >6 ppm did not earn incentives that week but could earn incentives at the next visit with the incentive value reset to $20.

2.5. Measures

2.5.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

Participants self-reported their age, sex (male or female), race (White, Black or African American, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, multi-racial and other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), sexual orientation (sexual/gender minoritized or cisgender/heterosexual), education (≤high school diploma/GED or >high school diploma/GED), insurance status (Medicaid, Medicare, uninsured, and/or private/military insurance), annual household income (<$10,000 or ≥$10,000), and housing status (currently experiencing homelessness or not experiencing homelessness) at baseline.

2.5.2. Smoking characteristics

Participants reported their average cigarettes smoked per day, the number of years that they had smoked, menthol cigarette preference, whether they had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days, and for how long they had been using e-cigarettes at baseline. The Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI)(Heatherton et al., 1989) assessed cigarette dependence (scores ≥5 indicated high dependence).

2.5.3. Substance use and mental health

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D-10)(Andresen et al., 1994) is a 10-item assessment of depression symptoms over the past week. Items are rated on a scale from 0 to 3, and total scores may range from 0 to 30. Scores ≥10 indicate clinically significant depression. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C)(Bush et al., 1998) is a 3-item assessment of at-risk drinking behaviors and possible alcohol use disorder. Scores may range from 0 to 12, and scores ≥3 for women or ≥4 for men suggest heavy drinking and/or active alcohol abuse or dependence. The Cannabis Use Disorder Identification Test – Short form (CUDIT-SF)(Bonn-Miller et al., 2016) is a 3-item assessment of Cannabis Use Disorder among participants who endorsed current cannabis use. Scores may range from 0 to 12, with scores ≥2 indicating possible cannabis use disorder.

2.5.4. Combustible cigarette (CC) use and cessation

The total number of days of CC smoking over the past week (0–7 days) was assessed at 4- and 8-weeks post-switch. Expired CO was assessed (via Vitalograph CO ecolyzer, Vitalograph Inc.) weekly from baseline (pre-switch) through 4 weeks post-switch, and at 8-weeks post-switch. At each visit after the switch date through 4 weeks post-switch, participants who reported that they had not smoked CCs in the past 7 days and had a CO level ≤6 ppm were considered CC abstinent.

2.5.5. E-cigarette use and dual use

Self-reported past week e-cigarette use (yes/no) and total days of e-cigarette use over the past week (0–7 days) were assessed at 4- and 8-weeks post-switch. In addition, participants were categorized as using 1) only e-cigarettes (no CCs), 2) only CCs (no e-cigarettes), 3) both e-cigarettes and CCs, or 4) neither e-cigarettes or CCs over the past 7 days at 4- and 8-weeks post-switch.

2.6. Analysis plan

Descriptive statistics were generated (e.g., frequencies, means) to characterize participant characteristics, CC use and cessation, and e-cigarette use overall and by treatment group. Exploratory T-tests (continuous variables) and chi-square (categorical variables) analyses were conducted to compare the intervention groups on participant characteristics and study outcomes. Analyses of CC cessation were conducted with two sets of outcomes: 1) participants with missing smoking status outcomes were considered smoking (intent-to-treat), and 2) participants with missing data were excluded from analyses (completers only). Because of the small sample size and the pilot study design, we highlighted all variables that differed between the treatment groups as indicated by p<0.20 (see Table 1, Table 2), per previous recommendations for pilot trials.(Lee et al., 2014)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| N | All (N=60) |

EC (n=30) |

EC+FI (n=30) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) or M (SD) | ||||

| SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Age, Years, M (SD) | 60 | 48.77 (10.98) | 50.30 (10.98) | 47.23 (10.94) |

| Sex, Female, % (n) | 60 | 25.0 (15) | 23.3 (7) | 26.7 (8) |

| Sexual/Gender Minoritized, % (n)a | 60 | 21.7 (13) | 23.3 (7) | 20.0 (6) |

| Race | 60 | |||

| White, % (n) | 53.3 (32) | 63.3 (19) | 43.3 (13) | |

| African American/Black, % (n) | 33.3 (20) | 23.3 (7) | 43.3 (13) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native, % (n) | 5.0 (3) | 3.3 (1) | 6.7 (2) | |

| Multi-Race/Other, % (n)b | 8.3 (5) | 10.0 (3) | 6.7 (2) | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity, % (n)c | 60 | 6.7 (4) | 0 (0) | 13.3 (4) |

| Currently Experiencing Homelessness, % (n) | 60 | 76.7 (46) | 80.0 (24) | 73.3 (22) |

| Annual Household Income <$10,000, % (n) | 58 | 82.8 (48) | 86.7 (26) | 78.6 (22) |

| Education, ≤High School/GED, % (n) | 60 | 78.3 (47) | 86.7 (26) | 70.0 (21) |

| Insurance | 60 | |||

| Medicaid, % (n) | 68.3 (41) | 70.0 (21) | 66.7 (20) | |

| Medicare, % (n) | 21.7 (13) | 16.7 (5) | 26.7 (8) | |

| Uninsured, % (n) | 18.3 (11) | 23.3 (7) | 13.3 (4) | |

| Private/Military, % (n)d | 8.3 (5) | 10.0 (3) | 6.7 (2) | |

| TOBACCO USE CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

| Cigarettes per day, M (SD)e | 59 | 16.00 (11.53) | 15.73 (12.13) | 16.28 (11.08) |

| Years of Smoking,M(SD) | 60 | 27.20 (12.09) | 29.37 (10.80) | 25.03 (13.08) |

| Preferred Cigarette Flavor | 60 | |||

| Non-Menthol, % (n) | 38.3 (23) | 36.7 (11) | 40 (12) | |

| Menthol, % (n) | 36.7 (22) | 40.0 (12) | 33.3 (10) | |

| Both, % (n) | 25.0 (15) | 23.3 (7) | 26.7 (8) | |

| Heaviness of Smoking Index, High Dependence (score ≥5), % (n) | 60 | 26.7 (16) | 33.3 (10) | 20.0 (6) |

| E-Cigarette Use, Past 30 days, % (n) | 60 | 35.0 (21) | 23.3 (7) | 46.7 (14) |

| SUBSTANCE USE/MENTALHEALTH | ||||

| CES-D, Depressed (score ≥10), % (n) | 60 | 68.3 (41) | 73.3 (22) | 63.3 (19) |

| AUDIT-C, Alcohol Use Disorder (score ≥3 [women] or ≥4 [men]), % (n) | 60 | 26.7 (16) | 23.3 (7) | 30.0 (9) |

| CUDIT-SF, Cannabis Use Disorder (score ≥2), % (n) | 60 | 33.3 (20) | 30 (9) | 36.7 (11) |

Note: Bolded information indicates possible differences between groups (p<0.20). Based on previous recommendations,50 a higher threshold for significance was highlighted because of the pilot study design and small sample size.

Sexual/gender minoritized participants included those who identified their sexual orientation as lesbian or gay (n=2), bisexual (n=3), queer, pansexual, and/or questioning (n=2), don’t know (n=1), or declined to answer (n=4), and/or those who identified their gender as transgender man (n=1), transgender woman (n=1), or declined to answer (n=2).

American Indian/White (n=2), Black/White (n=1), Black/multi-race (n=1), and Hispanic Black (n=1)

The proportion of Hispanic participants differed significantly by treatment group assignment (p<0.05).

Military health insurance (n=1).

Out of range value removed (n=1).

Table 2.

Smoking characteristics at 4- and 8-week post-switch follow-ups.

| n | Overall (N=60) | EC (N=30) | EC+FI (N=30) | p | Phi or Cohen’s d⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustible Cigarette Abstinence, CO-Verified, Past 7 days | ||||||

| 4 Weeks (intent-to-treat), % (n) | 60 | 8.3 (5) | 3.3 (1) | 13.3 (4) | 0.161 | 0.181 |

| 4 Weeks (completers only), % (n) | 31 | 16.1 (5/31) | 6.3 (1/16) | 26.7 (4/15) | 0.122 | 0.277 |

| 8 Weeks (intent-to-treat), % (n) | 60 | 11.7 (7) | 10.0 (3) | 13.3 (4) | 0.688 | 0.052 |

| 8 Week (completers only), % (n) | 27 | 25.9 (7/27) | 21.4 (3/14) | 30.8 (4/13) | 0.580 | 0.106 |

| Single and Dual Product Use (completers only) | ||||||

| 4 Weeks, E-Cigarette Use Only, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 31 | 16.1 (5/31) | 6.3 (1/16) | 26.7 (4/15) | 0.122 | 0.277 |

| 4 Weeks, CC Use Only, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 31 | 19.4 (6/31) | 18.8 (3/16) | 20.0 (3/15) | 0.930 | 0.016 |

| 4 Weeks, Dual E-Cigarette/CC Use, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 31 | 64.5 (20/31) | 75.0 (12/16) | 53.3 (8/15) | 0.208 | 0.226 |

| 8 Weeks, E-Cigarette Use Only, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 24 | 20.8 (5/24) | 7.7 (1/13) | 36.4 (4/11) | 0.085 | 0.352 |

| 8 Weeks, CC Use Only, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 24 | 20.8 (5/24) | 15.4 (2/13) | 27.3 (3/11) | 0.475 | 0.146 |

| 8 Weeks, Dual E-Cigarette/CC Use, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 24 | 50.0 (12/24) | 61.5 (8/13) | 36.4 (4/11) | 0.219 | 0.251 |

| 8 Weeks, No E-Cigarette or CC Use, Past 7 Days, % (n) | 24 | 8.3 (2/24) | 15.4 (2/13) | 0.0 (0/11) | 0.174 | 0.277 |

| Combustible Cigarette (CC) Use, Past 7 days (completers only) | ||||||

| 4 Weeks, Days of Use, Past 7 days,M(SD) | 31 | 3.26 (2.84) | 4.25 (2.77) | 2.20 (2.60) | 0.042 | 0.763 |

| 8 Weeks, Days of Use, Past 7 days, M (SD) | 25 | 3.20 (2.78) | 2.79 (2.33) | 3.73 (3.32) | 0.435 | 0.336 |

| E-Cigarette Use, Past 7 days (completers only) | ||||||

| 4 Weeks, Any E-Cigarette use, Past 7 days, % (n) | 31 | 80.6 (25) | 81.3 (13) | 80.0 (12) | 0.930 | 0.016 |

| 4 weeks, Days of E-Cigarette Use, Past 7 days,M(SD) | 28 | 4.36 (2.88) | 3.64 (2.84) | 5.07 (2.84) | 0.195 | 0.502 |

| 8 Weeks, Any E-Cigarette use, Past 7 days, % (n) | 24 | 70.8 (17) | 69.2 (9) | 72.7 (8) | 0.851 | 0.038 |

| 8 weeks, Days of E-C Use, Past 7 days, M (SD) | 24 | 4.17 (3.10) | 4.15 (3.11) | 4.18 (3.25) | 0.983 | 0.009 |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO), parts per million (ppm; completers only) | ||||||

| Baseline (ppm), M (SD) | 60 | 14.32 (6.91) | 14.07 (5.34) | 14.57 (8.27) | 0.782 | 0.072 |

| 4 Weeks (ppm),M(SD) | 31 | 10.65 (8.97) | 14.31 (9.80) | 6.73 (6.15) | 0.015 | 0.919 |

| 4 Weeks, Change from Baseline (ppm),M(SD) | 31 | −4.06 (11.07) | 0.31 (12.10) | −8.73 (7.77) | 0.019 | 0.883 |

| 8 Weeks (ppm), M (SD) | 27 | 8.78 (7.44) | 8.86 (8.49) | 8.69 (6.47) | 0.955 | 0.022 |

| 8 Weeks, Change from Baseline (ppm), M (SD) | 27 | −5.85 (9.05) | −4.57 (8.91) | −7.23 (9.35) | 0.456 | 0.292 |

Note: Bolded information indicates possible differences between groups (p<0.20). Based on previous recommendations,50 a higher threshold for significance was highlighted because of the pilot study design and small sample size. The “intent-to-treat” outcomes categorized participants with missing smoking status outcomes as smoking, whereas “completers only” outcomes included only those with non-missing responses (and excluded participants with missing outcome data).

Phi values ≥0.10, 0.30, and 0.50 indicate small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively, for chi-square analyses (categorical variables). Cohen’s d values ≥0.20, 0.50, 0.80 indicate small, medium, and large effects sizes, respectively, for t-tests (continuous variables).

3. Results

3.1. Eligibility screening

A total of 49 screened individuals were excluded from participation for the following reasons: CO value <8 ppm (n=37), smoking <5 cigarettes per day (n=14), REALM-SF score <4 (n=13), unable to read a sentence selection from the consent form (n=6), unwilling or unable to attend all study visits (n=4), age <21 (n=3), or unwilling to switch to e-cigarettes (n=1). Also note that 8 enrolled participants reported a smoking rate ≥5 cigarettes per day during the initial screening and later reported <5 cigarettes per day at the baseline assessment.

3.2. Participant characteristics

Participants were predominantly male (75 %, n=45), half of participants were racially and/or ethnically minoritized (50 %, n=30), with an average age of 48.8 (SD=11.0) years. Participants reported smoking an average of 16.0 (SD=11.5) cigarettes per day (CPD) for 27.2 (SD=12.1) years. At baseline, 35 % (n=21) of participants reported any e-cigarette use in the past 30 days (see Table 1). These participants were asked to select all reasons for their e-cigarettes use from the following options: to reduce/quit smoking traditional cigarettes (52.4 %, n=11), saving money, e-cigarettes cost less than cigarettes (42.9 %, n=9), e-cigarettes are allowed in areas where cigarettes are not (38.1 %, n=8), for pleasure/enjoyment (28.6 %, n=6), curiosity (28.6 %, n=6), for the e-cigarette flavors (14.3 %, n=3), for my health, e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes (9.5 % (n=2), and to lose weight/keep weight down (4.8 %, n=1). A total of 23.8 % (n=5) of participants selected “other” reasons for use. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

3.3. Participant retention

CC abstinence was assessed for 31 of 60 (51.7 %) and 27 of 60 (45.0 %) participants at the 4- and 8-week post-switch follow-ups, respectively. By intervention group, CC abstinence was assessed in 53.3 % (EC; n=16) vs. 50.0 % (EC+FI, n=15) of participants at the 4-week post-switch follow up; and 46.7 % (EC, n=14) vs. 43.3 % (EC+FI, n=13) of participants at the 8-week post-switch follow-up. Note that some variables had additional missing values which reduced the sample sizes further; the analytic sample sizes for each variable are noted in Table 2.

3.4. Combustible cigarette (CC) use and abstinence

Overall, across treatment groups, participants reduced their CC use from daily at baseline (inclusion criteria) to 3.26 days per week at the 4-week follow-up and 3.20 days at the 8-week follow-up. At 4 weeks, participants assigned to the EC+FI group reported smoking CCs on significantly fewer days during the previous week than those assigned to the EC group (2.20 days vs. 4.25 days). However, this pattern did not persist through the 8-week follow-up, with the EC group reporting fewer days of CC smoking (2.79 days) than EC+FI (3.73 days). See Table 2.

When participants with missing smoking status at follow-ups were categorized as smoking, CO-verified 7-day point prevalence CC abstinence was 8.3 % (n=5) overall at 4-week and 11.7 % (n=7) overall at 8-week follow-ups. The proportion of participants who were CC abstinent was descriptively higher in the EC+FI than the EC group at 4-week and 8-week follow-ups. Among participants who completed follow-ups, CO-verified 7-day point prevalence abstinence was 16.1 % (n=5 out of 31 completers) overall at 4 weeks, and 25.9 % (n=7 out of 27 completers) overall at 8 weeks. The proportion of participants who were CC abstinent was descriptively higher in the EC+FI than the EC group at 4-week and 8-week follow-ups. See Table 2 and Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Carbon monoxide-verified combustible cigarette abstinence rates by intervention group. Note: The “intent-to-treat” groups had 30 participants each within the EC and EC+FI groups at 4- and 8-weeks post-switch. The “completers only” groups had 16 and 15 participants in the EC and EC+FI groups at 4 weeks post-switch, and 14 and 13 participants in the EC and EC+FI group at 8 weeks post-switch.

3.5. Carbon monoxide (CO)

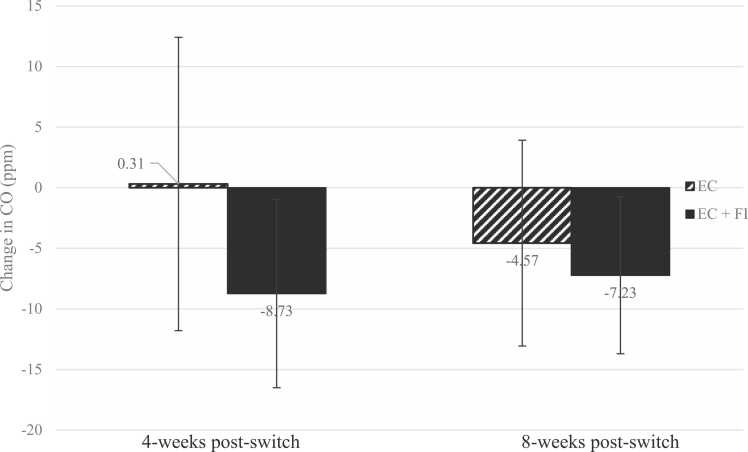

Overall, CO levels decreased from baseline among those who completed study follow-ups, with an observed CO decrease of 4.06 ppm (SD=11.06, n=31) by 4 weeks post-switch and 5.85 ppm (SD=9.05, n=27) by 8 weeks post-switch. CO levels and changes in CO differed significantly by treatment group at the 4-week follow-up, with those assigned to EC+FI showing lower CO levels and greater decreases in CO than those assigned to EC. CO levels at the 8-week follow-up were similar between groups, though decreases in CO remained descriptively greater among those assigned to EC+FI. See Table 2 and Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Changes in CO (ppm) from baseline to 4-week (n=31) and 8-week (n=27) follow-up by intervention group. Note: The intervention groups had 16 and 15 participants each in the EC and EC+FI groups at 4 weeks post-switch, and 14 and 13 participants in the EC and EC+FI group at 8 weeks post-switch. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean change in CO.

3.6. E-cigarette (EC) use

By the 4-weeks post-switch, 80.6 % of participants reported e-cigarette use during the past week. By 8 weeks post-switch, 70.8 % reported past week e-cigarette use (4 weeks after they were no longer receiving nicotine pods through the study). The proportion who reported past week e-cigarette use were similar between groups at both follow-ups. Overall, participants reported using e-cigarettes on 4.36 days and 4.17 days during the previous week at the 4- and 8-week follow-ups, respectively. Descriptively, participants assigned to EC+FI reported using e-cigarettes on more days than those assigned to the EC group at the 4-week follow-up, though this pattern was no longer apparent at the 8-week follow-up. For full details of the results, including p-values, see Table 2.

3.7. Incentives contingent on combustible cigarette abstinence

Participants assigned to the EC+FI intervention earned a range of $0-$150 between the switch day and 4 weeks post-switch, though notably, most participants (73.3 %, n=22) did not earn any incentives. Overall, the mean amount of earnings was $16 (SD=$35.61) per participant (median and mode=$0). Attendance at each of the five weekly visits where CC abstinence-contingent incentives could be earned ranged from 46.7 % to 53.3 %; thus, the low rate of follow up was a major contributing factor to low incentive earnings. Among participants who earned any CC abstinence-contingent incentives (n=8), the mean amount earned was $60 (SD=$47.28; median=$42.50; mode=$20).

3.8. Intervention perceptions

Participants’ (n=31) perceptions of the intervention were assessed at the 4-week follow-up. Most participants (74.2 %; n=23) found the study-provided e-cigarettes to be very or extremely helpful for avoiding CC smoking (22.6 % [n=7] moderately/somewhat, 3.2 % not at all [n=1]). Most participants (67.7 %, n=21) reported a very or extremely high likelihood of completely switching to e-cigarettes from CC cigarettes in the future (22.6 % moderately/somewhat [n=7], 9.7 % not at all [n=3]). Most participants (64.5 %; n=20) reported being extremely or very likely to continue using e-cigarettes after the study-provided pods were no longer available (29.0 % moderately/somewhat [n=9], 6.5 % not at all [n=2]). Participants endorsed the following as possible reasons for not continuing to use e-cigarettes after study completion (participants were allowed to select up to three reasons out of six options, and could also self-specify their reason): cost (48.4 %, n=15), feeling like they were not getting enough nicotine (25.8 %, n=8), preferring cigarettes (22.6 %; n=7), dislike of the e-cigarette flavors (22.6 %; n=7), difficulty keeping the device charged (19.5 %; n=6), and because using the e-cigarette was not satisfying (12.9 %; n=4). Finally, no e-cigarette related adverse events were brought to the attention of study staff or investigators during the study.

4. Discussion

The current study evaluated the feasibility and potential efficacy of an e-cigarette switching intervention offered with and without financial incentives, with the goal of promoting CC cessation among adults accessing day shelter services. CO-verified CC cessation rates were modest overall at follow-ups (i.e., 8–12 % [intent-to-treat], 16–26 % [completers only]), yet still promising, given the barriers faced by this population. CC cessation rates appeared higher in the EC+FI group in the shorter term (4 weeks post-switch) while the study provided nicotine pods. Likewise, reductions in days of CC smoking and CO were observed, with greater short-term benefits for the EC+FI intervention. Past week e-cigarette use remained high at follow-ups (71–81 %), with slightly more days of e-cigarette use in the EC+FI than the EC group in the short-term. Overall, participants reported that the e-cigarettes were helpful for avoiding CCs , and most reported a high likelihood of switching from CCs to e-cigarettes in the future. E-cigarette switching has the potential to reduce harm among adults accessing day shelter service, and offering incentives for CC cessation may enhance the benefits.

While previous randomized trials have demonstrated that e-cigarettes can be an effective harm reduction and intervention strategy, (Bullen et al., 2013, Foulds et al., 2022, Hajek et al., 2019, Hajek et al., 2019, Hatsukami et al., 2019, Walker et al., 2020) only few small studies have demonstrated the feasibility and potential efficacy of offering e-cigarettes as a harm-reduction strategy among adults experiencing homelessness(Collins et al., 2019; Dawkins et al., 2020; Scheibein et al., 2020). Cox et al. (2022) published a protocol describing an ongoing full-scale randomized trial to evaluate e-cigarettes (starter pack plus 4 weeks of nicotine e-liquid) compared with usual care (advice and referral) in this group. In addition, past research has indicated that financial incentives are effective for promoting smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults(Kendzor et al., 2024) and studies evaluating this approach in adults experiencing homelessness have demonstrated feasibility and potential efficacy(Baggett et al., 2018; Businelle et al., 2014; Molina et al., 2022; Rash et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2023). Past research has indicated that there is interest in using both e-cigarettes and incentives to aid smoking cessation among adults experiencing homelessness(Boozary et al., 2022). The current study is the first to evaluate an e-cigarette intervention combined with incentives for CC abstinence.

Across both e-cigarette switching groups, among those who completed the study, more than a quarter of participants achieved CO-confirmed CC abstinence at the final 8-weeks post-switch follow-up, despite facing the significant day-to-day challenges associated with homelessness. Importantly, at 4-weeks post-switch, those who received financial incentives for CC abstinence (in addition to the EC switching intervention) had higher rates of CO-verified CC abstinence and exclusive use of ECs (no CC use), greater reductions in expired CO, and they reported more days of EC use and fewer days of CC use compared with those who received the EC switching intervention alone (all p’s <0.02). However, these early differences diminished by 8-weeks post-switch. Thus, findings suggest that the benefits of EC switching interventions may be enhanced by incentivizing CC abstinence.

The current study has several limitations. Despite the provision of phones and shelter-based intervention delivery, low follow-up rates were a challenge with only 52 % and 45 % returning to provide follow-up information about CC smoking and other outcomes at 4- and 8-week follow-ups, respectively. Future research must consider additional strategies to promote continued engagement and increase the uptake of incentives, perhaps by integrating tobacco harm reduction intervention and follow-up into shelter-based social services, providing nicotine pods for longer than four weeks, and incorporating longer incentive periods with higher incentive values. Plausibly, continued intervention engagement might improve if the intervention focused on adults moving from homelessness to supportive housing, rather than adults who are simply accessing day shelter services, as this population is likely to be more transient. On the other hand, it may be practical to anticipate intermittent engagement and loss to follow-up when working with in populations that experience significant barriers to achieving and maintaining good physical and mental health. Notably, the pilot study sample was small and focused on a single shelter. Nevertheless, findings provide initial evidence of the feasibility of using e-cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy among adults receiving day shelter services and offer a starting point for intervention.

Future e-cigarette switching studies might consider including more intensive treatment components such as counseling and perhaps other cessation pharmacotherapy. Although most participants found the intervention to be helpful, some indicated that the cost of e-cigarettes and perceptions of not getting enough nicotine from e-cigarettes were barriers to continued use. The cost barrier may be addressed by providing information about the lower relative cost of e-cigarette pods versus CCs(Kai-Wen et al., 2021). However, it is noteworthy that the cost of purchasing start-up kits (e.g., e-cigarette device, charger, nicotine pods) and multi-packs of nicotine pods may deter people with few resources from using e-cigarettes. Regarding e-cigarette nicotine uptake, it may also be helpful to offer information about the comparability of nicotine intake between e-cigarettes and CCs. Specifically, while peak nicotine levels may be initially lower for e-cigarettes than CCs among novice e-cigarette users, they tend to be similar to CCs among experienced e-cigarette users(Prochaska et al., 2022). Plausibly, e-cigarettes could be paired with other forms of nicotine replacement therapy(Walker et al., 2020) to increase nicotine uptake following the initial switch from CCs.

In conclusion, e-cigarette switching is a promising approach to tobacco harm reduction among adults experiencing homelessness, and the effect of e-cigarette switching interventions may be enhanced by incentivizing CC abstinence. However, intervention refinements are needed to provide education and increase engagement, and a longer-term intervention strategy may be needed. Tobacco harm reduction via e-cigarette switching among adults experiencing homelessness offers one approach to addressing significant tobacco-related health disparities in a frequently overlooked and underserved population.

Funding/acknowledgements

We would like to thank the dedicated leaders and staff of the Homeless Alliance in Oklahoma City, OK. This research was supported by Oklahoma Tobacco Settlement Endowment Trust (TSET) grant R23-02 and Grants P30CA225520 (Stephenson Cancer Center) and P30CA056036 (Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center). J. S. Ahluwalia was funded in part by P20GM130414, a NIH funded Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE). Manuscript preparation was additionally supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant K01MD015295 to A. C. Alexander. This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03743532).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Munjireen S. Sifat: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Adam C. Alexander: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Michael S. Businelle: Writing – review & editing. Summer G. Frank-Pearce: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Laili Kharazi Boozary: Writing – review & editing. Theodore L. Wagener: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Jasjit S. Ahluwalia: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Darla E. Kendzor: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft.

Disclosures

Munjireen S. Sifat, Adam C. Alexander, Michael S. Businelle, Summer G. Frank-Pearce, Laili Kharazi Boozary, and Theodore L. Wagener have nothing to disclose.

Dr. Kendzor is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Qnovia. Inc., which is a drug development company focused on inhaled therapies including prescription inhaled nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (not used or evaluated in the current study).

Dr. Ahluwalia also serves as a consultant and has equity in a start-up company, Qnovia. Qnovia is due to begin Phase I clinical trials to test a prescription nicotine replacement therapy through CEDR at the FDA. Dr. Ahluwalia received sponsored funds for travel expenses as a speaker for annual GTNF conferences from 2021 to 2024; as a speaker for the 2022 and 2024 Tobacco Science Research Conference; and, for the 2021, 2022, and 2023 Food and Drug Law Institute conferences.

Author agreement

All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript being submitted.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Abrams D.B., Glasser A.M., Pearson J.L., Villanti A.C., Collins L.K., Niaura R.S. Harm minimization and tobacco control: reframing societal views of nicotine use to rapidly save lives. 2018;39(1):193–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C., Majeste A., Hanus J., Wang S. E-Cigarette aerosol exposure induces reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and cell death in vascular endothelial cells. Toxicol. Sci. 2016;154(2):332–340. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen E.M., Malmgren J.A., Carter W.B., Patrick D.L. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994;10(2):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arozullah A.M., Yarnold P.R., Bennett C.L., Soltysik R.C., Wolf M.S., Ferreira R.M., Lee S.-Y.D., Costello S., Shakir A., Denwood C. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Med. care. 2007:1026–1033. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett T.P., Chang Y., Yaqubi A., McGlave C., Higgins S.T., Rigotti N.A. Financial incentives for smoking abstinence in homeless smokers: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2018;20(12):1442–1450. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggett T.P., Rigotti N.A. Cigarette smoking and advice to quit in a national sample of homeless adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;39(2):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller M.O., Heinz A.J., Smith E.V., Bruno R., Adamson S. Preliminary development of a brief cannabis use disorder screening tool: the cannabis use disorder identification test short-form. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016;1(1):252–261. doi: 10.1089/can.2016.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boozary L.K., Frank-Pearce S.G., Alexander A.C., Sifat M.S., Kurien J., Waring J.J., Ehlke S.J., Businelle M.S., Ahluwalia J.S., Kendzor D.E. Tobacco use characteristics, treatment preferences, and motivation to quit among adults accessing a day shelter in Oklahoma City. Drug Alcohol Depend. Rep. 2022;5 doi: 10.1016/j.dadr.2022.100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown H.A., Roberts R.D., Chen T.A., Businelle M.S., Obasi E.M., Kendzor D.E., Reitzel L.R. Perceived disease risk of smoking, barriers to quitting, and cessation intervention preferences by sex amongst homeless adult concurrent tobacco product users and conventional cigarette-only users. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022;19(6):3629. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen C., Howe C., Laugesen M., McRobbie H., Parag V., Williman J., Walker N. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9905):1629–1637. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush K., Kivlahan D.R., McDonell M.B., Fihn S.D., Bradley K.A. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch. Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle M.S., Kendzor D.E., Kesh A., Cuate E.L., Poonawalla I.B., Reitzel L.R., Okuyemi K.S., Wetter D.W. Small financial incentives increase smoking cessation in homeless smokers: a pilot study. Addict. Behav. 2014;39(3):717–720. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle M.S., Kendzor D.E., Reitzel L.R., Costello T.J., Cofta-Woerpel L., Li Y., Mazas C.A., Vidrine J.I., Cinciripini P.M., Greisinger A.J. Mechanisms linking socioeconomic status to smoking cessation: a structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychol. 2010;29(3):262. doi: 10.1037/a0019285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp P.W., Pawlak E.A., Lackey J.T., Keating J.E., Reeber S.L., Glish G.L., Jaspers I. Flavored e-cigarette liquids and cinnamaldehyde impair respiratory innate immune cell function. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2017;313(2) doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00452.2016. L278-l292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S.E., Nelson L.A., Stanton J., Mayberry N., Ubay T., Taylor E.M., Hoffmann G., Goldstein S.C., Saxon A.J., Malone D.K., Clifasefi S.L., Okuyemi K. Harm reduction treatment for smoking (HaRT-S): findings from a single-arm pilot study with smokers experiencing chronic homelessness. Subst. Abus. 2019;40(2):229–239. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1572049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius M.E. Tobacco product use among adults–United States, 2021. Mmwr. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023;72 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7218a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox S., Bauld L., Brown R., Carlisle M., Ford A., Hajek P., Li J., Notley C., Parrott S., Pesola F., Robson D., Soar K., Tyler A., Ward E., Dawkins L. Evaluating the effectiveness of e-cigarettes compared with usual care for smoking cessation when offered to smokers at homeless centres: protocol for a multi-centre cluster-randomized controlled trial in Great Britain. Addiction. 2022;117(7):2096–2107. doi: 10.1111/add.15851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallery J., Raiff B.R., Grabinski M.J. Internet-based contingency management to promote smoking cessation: a randomized controlled study. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2013;46(4):750–764. doi: 10.1002/jaba.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins L., Bauld L., Ford A., Robson D., Hajek P., Parrott S., Best C., Li J., Tyler A., Uny I., Cox S. A cluster feasibility trial to explore the uptake and use of e-cigarettes versus usual care offered to smokers attending homeless centres in Great Britain. PLoS One. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild A.L., Lee J.S., Bayer R., Curran J. E-Cigarettes and the Harm-Reduction Continuum. 2018;378(3):216–219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1711991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsalinos, K.E., & Barbouni, A. (2020). Association between electronic cigarette use and smoking cessation in the European Union in 2017: analysis of a representative sample of 13 057 Europeans from 28 countries. tobaccocontrol-2019-055190. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055190%J Tobacco Control [DOI] [PubMed]

- Farsalinos K.E., Niaura R. Vol. 22. Nicotine & Tobacco Research; 2020. E-cigarettes and Smoking Cessation in the United States According to Frequency of E-cigarette Use and Quitting Duration: Analysis of the 2016 and 2017 National Health Interview Surveys; pp. 655–662. (Nicotine & Tobacco Research). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M.C., Jaén C.R., Baker T.B., Bailey W.C., Benowitz N.L., Curry S.J., Dorfman S.F., Froelicher E.S., Goldstein M.G., Healton C.G. US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2008. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J., Cobb C.O., Yen M.S., Veldheer S., Brosnan P., Yingst J., Hrabovsky S., Lopez A.A., Allen S.I., Bullen C., Wang X., Sciamanna C., Hammett E., Hummer B.L., Lester C., Richie J.P., Chowdhury N., Graham J.T., Kang L., Eissenberg T. Effect of electronic nicotine delivery systems on cigarette abstinence in smokers with no plans to quit: exploratory analysis of a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2022;24(7):955–961. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A., Coakley R.C., Mascenik T., Rowell T.R., Davis E.S., Rogers K., Webster M.J., Dang H., Herring L.E., Sassano M.F., Livraghi-Butrico A., Van Buren S.K., Graves L.M., Herman M.A., Randell S.H., Alexis N.E., Tarran R. Chronic E-cigarette exposure alters the human bronchial epithelial proteome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198(1):67–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2033OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P., Etter J.-F., Benowitz N., Eissenberg T., McRobbie H. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. 2014;109(11):1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P., Phillips-Waller A., Przulj D., Pesola F., Smith K.M., Bisal N., Li J., Parrott S., Sasieni P., Dawkins L., Ross L., Goniewicz M., Wu Q., McRobbie H.J. E-cigarettes compared with nicotine replacement therapy within the UK Stop Smoking Services: the TEC RCT. 2019;23:43. doi: 10.3310/hta23430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajek P., Phillips-Waller A., Przulj D., Pesola F., Myers Smith K., Bisal N., Li J., Parrott S., Sasieni P., Dawkins L., Ross L., Goniewicz M., Wu Q., McRobbie H.J. A randomized trial of E-cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy. 2019;380(7):629–637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Boyce J., Lindson N., Butler A.R., McRobbie H., Bullen C., Begh R., Theodoulou A., Notley C., Rigotti N.A., Turner T., et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D.K., Meier E., Lindgren B.R., Anderson A., Reisinger S.A., Norton K.J., Strayer L., Jensen J.A., Dick L., Murphy S.E., Carmella S.G., Tang M.-K., Chen M., Hecht S.S., O’connor R.J., Shields P.G. A randomized clinical trial examining the effects of instructions for electronic cigarette use on smoking-related behaviors and biomarkers of exposure. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton T.F., Kozlowski L.T., Frecker R.C., Rickert W., Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. Br. J. Addict. 1989;84(7):791–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzberg J.S., Carpenter V.L., Kirby A.C., Calhoun P.S., Moore S.D., Dennis M.F., Dennis P.A., Dedert E.A., Beckham J.C. Mobile contingency management as an adjunctive smoking cessation treatment for smokers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15(11):1934–1938. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kai-Wen C., Ce S., Hye Myung L., Frank J.C., Geoffrey T.F., Ron B., Bryan W.H., Sara C.H., Richard J.O., Connor, David T.L., Cummings K.M. Costs of vaping: evidence from ITC four country smoking and vaping survey. Tob. Control. 2021;30(1):94. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Costello T.J., Castro Y., Reitzel L.R., Cofta-Woerpel L.M., Li Y., Mazas C.A., Vidrine J.I., Cinciripini P.M. Financial strain and smoking cessation among racially/ethnically diverse smokers. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100(4):702–706. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Frank-Pearce S.G., Waring J.J., Chen S., Hébert E.T., Swartz M.D., Alexander A.C., Sifat M.S., Boozary L.K. Financial incentives for smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2024;7(7) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.18821. e2418821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Poonawalla I.B., Cuate E.L., Kesh A., Rios D.M., Ma P., Balis D.S. Financial incentives for abstinence among socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals in smoking cessation treatment. Am. J. Public Health. 2015;105(6):1198–1205. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Vidrine D.J., Frank-Pearce S.G., Shih Y.T., Dallery J., Alexander A.C., Boozary L.K., Waring J.J.C., Ehlke S.J. Mobile contingency management for smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: protocol for a randomized trial. Conte Clin. Trials. 2022;114 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Businelle M.S., Waring J.J., Mathews A.J., Geller D.W., Barton J.M., Alexander A.C., Hébert E.T., Ra C.K., Vidrine D.J. Automated mobile delivery of financial incentives for smoking cessation among socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: feasibility study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2020;8(4) doi: 10.2196/15960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendzor D.E., Reitzel L.R., Mazas C.A., Cofta-Woerpel L.M., Cao Y., Ji L., Costello T.J., Vidrine J.I., Businelle M.S., Li Y. Individual-and area-level unemployment influence smoking cessation among African Americans participating in a randomized clinical trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012;74(9):1394–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz D., West R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: it’s not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob. Control. 2009;18(1):43–46. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E.C., Whitehead A.L., Jacques R.M., Julious S.A. The statistical interpretation of pilot trials: should significance thresholds be reconsidered? BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014;14(1):41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy D.T., Cummings K.M., Villanti A.C., Niaura R., Abrams D.B., Fong G.T., Borland R. A framework for evaluating the public health impact of e-cigarettes and other vaporized nicotine products. 2017;112(1):8–17. doi: 10.1111/add.13394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Hui X., Fu J., Ahmed M.M., Yao L., Yang K. Electronic cigarettes versus nicotine-replacement therapy for smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Tob. Induc. Dis. 2022;20:90. doi: 10.18332/tid/154075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margham J., McAdam K., Forster M., Liu C., Wright C., Mariner D., Proctor C. Chemical composition of aerosol from an E-cigarette: a quantitative comparison with cigarette smoke. Chem. Res Toxicol. 2016;29(10):1662–1678. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina M.F., Hall S.M., Stitzer M., Kushel M., Chakravarty D., Vijayaraghavan M. Contingency management to promote smoking cessation in people experiencing homelessness: leveraging the electronic health record in a pilot, pragmatic randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2022;17(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0278870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notley C., Gentry S., Livingstone-Banks J., Bauld L., Perera R., Hartmann-Boyce J. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019;(7) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004307.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omaiye E.E., McWhirter K.J., Luo W., Pankow J.F., Talbot P. High-Nicotine electronic cigarette products: toxicity of JUUL fluids and aerosols correlates strongly with nicotine and some flavor chemical concentrations. Chem. Res Toxicol. 2019;32(6):1058–1069. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Alessi S.M., Olmstead T.A., Rash C.J., Zajac K. Contingency management treatment for substance use disorders: how far has it come, and where does it need to go? Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2017;31(8):897–906. doi: 10.1037/adb0000287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska J.J., Vogel E.A., Benowitz N. Nicotine delivery and cigarette equivalents from vaping a JUULpod. Tob. Control. 2022;31(e1):e88–e93. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash C.J., Petry N.M., Alessi S.M. A randomized trial of contingency management for smoking cessation in the homeless. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2018;32(2):141–148. doi: 10.1037/adb0000350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rash C.J., Stitzer M., Weinstock J. Contingency management: new directions and remaining challenges for an evidence-based intervention. J. Subst. Abus. Treat. 2017;72:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak A., Feleszko W., Smith D.M., Goniewicz M. How close are we to definitively identifying the respiratory health effects of e-cigarettes? Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2018;12(7):549–556. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2018.1483724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly S.M., Bitzer Z.T., Goel R., Trushin N., Richie J.P., Jr. Vol. 21. Nicotine & Tobacco Research; 2019. Free Radical, Carbonyl, and Nicotine Levels Produced by Juul Electronic Cigarettes; pp. 1274–1278. (Nicotine & Tobacco Research). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibein F., McGirr K., Morrison A., Roche W., Wells J.S.G. An exploratory non-randomized study of a 3-month electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) intervention with people accessing a homeless supported temporary accommodation service (STA) in Ireland. Harm Reduct. J. 2020;17(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12954-020-00406-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab L., Goniewicz M.L. Nicotine, carcinogen, and toxin exposure in long-term E-cigarette and nicotine replacement therapy users. 2017;166(6):390–400. doi: 10.7326/M16-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh G.K., Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950–2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J. Environ. Public Health. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2819372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops W.W., Dallery J., Fields N.M., Nuzzo P.A., Schoenberg N.E., Martin C.A., Casey B., Wong C.J. An internet-based abstinence reinforcement smoking cessation intervention in rural smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1-2):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talih S., Salman R., El-Hage R., Karam E., Karaoghlanian N., El-Hellani A., Saliba N., Shihadeh A. Characteristics and toxicant emissions of JUUL electronic cigarettes. Tob. Control. 2019;28(6):678–680. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E.M., Kendzor D.E., Reitzel L.R., Businelle M.S. Health risk factors and desire to change among homeless adults. Am. J. Health Behav. 2016;40(4):455–460. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.40.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagener T.L., Floyd E.L., Stepanov I., Driskill L.M., Frank S.G., Meier E., Leavens E.L., Tackett A.P., Molina N., Queimado L. Have combustible cigarettes met their match? The nicotine delivery profiles and harmful constituent exposures of second-generation and third-generation electronic cigarette users. 2017;26(e1):e23–e28. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053041%J. (Tobacco Control) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker N., Parag V., Verbiest M., Laking G., Laugesen M., Bullen C. Nicotine patches used in combination with e-cigarettes (with and without nicotine) for smoking cessation: a pragmatic, randomised trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells S.Y., LoSavio S.T., Patel T.A., Evans M.K., Beckham J.C., Calhoun P., Dedert E.A. Contingency management and cognitive behavior therapy for smoking cessation among veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: design and methodology of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 2022;119 doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2022.106839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetter D.W., Cofta-Gunn L., Irvin J.E., Fouladi R.T., Wright K., Daza P., Mazas C., Cinciripini P.M., Gritz E.R. What accounts for the association of education and smoking cessation? Prev. Med. 2005;40(4):452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S.M., Blalock D.V., Young J.R., Griffin S.C., Hertzberg J.S., Calhoun P.S., Beckham J.C. Mobile health contingency management for smoking cessation among veterans experiencing homelessness: a comparative effectiveness trial. Prev. Med Rep. 2023;35 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2023.102311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]