Abstract

Despite being increasingly adopted in various regions, the model of Hospital‐at‐home can still appear to be confusing to many healthcare workers. The authors examined and summarized the existing concepts and implementations of Hospital‐at‐home. How Hospital‐at‐home contrasts to traditional inpatient models were outlined.

Keywords: community medicine, hospital general medicine, Hospital‐at‐home, hospital‐in‐the‐home, internal medicine

How Hospital‐at‐home contrasts to traditional inpatient models were outlined. How Hospital‐at‐home is implemented in an acute hospital setting were also being described. The Hospital‐at‐home model offers a compelling blueprint for what the future of acute care might look like.

1. INTRODUCTION

The conceptualization of a dedicated facility to cater to the sick can be traced back millennia, with the earliest mentions in ancient Mesopotamia. Historically, the gravitation toward centralized locations for healthcare was fueled by the dual objective of consolidating expertise and providing sanctuaries for the diseased to receive care and recuperation. With the advent of modern medicine, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the hospital shift from primarily a refuge for the poor and sick to a center of advanced medical research and treatment. As medical science advanced, there was a growing emphasis on specialized care, which further entrenched the hospital's role in healthcare delivery.

However, the latter half of the 20th century witnessed a unique shift. As medical technology became more portable and as healthcare strategies started emphasizing patient‐centric care, the concept of home healthcare began to gain traction. 1 This was not a return to the past, where physicians commonly made house calls, but rather an innovative fusion of modern medicine's capabilities with the comforts of home.

The term “hospitalist” was coined in the late 1990s, denoting a physician whose primary professional focus is the general medical care of hospitalized patients. 2 Their unique position allows them to bridge the gap between outpatient and inpatient care. With the Hospital‐at‐home model's emergence, hospitalists have found a new avenue to extend their expertise. Instead of being confined to the hospital's physical boundaries, these physicians now manage acute care episodes in the patient's home setting, supported by a suite of modern technologies and a multidisciplinary team.

The increasing interest in Hospital‐at‐home models is not only a testament to technological advancements but also a reflection of the changing patient and provider preferences. With challenges like overcrowded wards, hospital‐acquired infections, and rising operational costs, there is a pressing need for alternative healthcare delivery methods.3, 4, 5 Hospital‐at‐home, managed adeptly by hospitalists and backed by robust technological support, presents an exciting prospect in this evolving landscape.

2. METHOD

The authors examined and summarized the existing concepts and implementations of Hospital‐at‐home. How Hospital‐at‐home contrasts to traditional inpatient models were outlined. How this is being setup and implemented in an acute hospital setting were also briefly described to complement the existing literature.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Definition of Hospital‐at‐home

The “Hospital‐at‐home” concept emerges from an intersection of clinical, technological, and sociological advancements in healthcare. Central to its philosophy is the principle of providing acute, hospital‐level care in the more familiar and comfortable confines of a patient's own home. But to fully grasp this innovative model, it is essential to delineate its core characteristics and demarcate its boundaries.

3.1.1. What it is

At its essence, Hospital‐at‐home is an acute care model that endeavors to replicate the standard of care conventionally offered within a hospital, but within the patient's home. This model necessitates a robust system that seamlessly combines:

Medical equipment and monitoring: Advanced portable medical devices and telehealth tools enable real‐time monitoring of patient vitals, ensuring quick clinical decisions. 5

Multidisciplinary care: Much like the hospital environment, Hospital‐at‐home models often involve a collaborative effort of physicians, nurses, therapists, and other healthcare professionals. This integrated approach ensures a holistic treatment plan and closely mirrors the inpatient experience. 6

3.1.2. What it is not

The rise of various home‐based healthcare services has sometimes blurred the lines of distinction. A summary of differences is provided in Table 1.

It is not Transition Care (Hospital‐to‐home): Transition care primarily focuses on posthospital discharge, ensuring the patient's smooth recovery and reducing the likelihood of readmissions. 7 The core objective here is bridging the gap between hospital and home rather than replicating hospital‐level care at home. 8

It is not Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy (OPAT): While both services involve treatments at home, OPAT is more specialized, often requiring patients to make frequent visits to the hospital for intravenous antibiotic administration.9, 10

It is not Home Health Care: Home healthcare offers services such as physical therapy, nursing care, or wound care after hospitalization but lacks the acute level of care and real‐time monitoring intrinsic to Hospital‐at‐home. 11

It is not Palliative Home Care: While palliative care can be provided at home, its primary goal was to offer relief from the symptoms and stress of serious illness, rather than to provide acute treatment. The main aim was to improve the quality of life for both the patient and the family. 12

TABLE 1.

Hospital‐at‐home with other services.

| Services compared | Inpatient | Outpatient | 24/7 availability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital‐at‐home |

|

|

Inpatient acute care service. | |

| Transitional care (Hospital‐to‐home) |

|

Typically, postdischarge, aims to prevent readmissions. | ||

| OPAT |

|

Typically rendered in infectious disease clinics. Patient travels to clinics to receive intravenous antibiotic administrations. |

||

| Home health care |

|

Nursing, allied health services. No acute care and regular vital signs monitoring. |

||

| Palliative home care |

|

|

Palliative care delivered at home, with aim of relieving symptoms and providing care in the comfort of familiar environment. |

Note: Differences vary depending on delivery by each institution; there might be some overlap between the services.

Abbreviation: OPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy.

3.2. Deviations in implementation

The Hospital‐at‐home model, despite its foundational principles and objectives, has been interpreted and implemented with varying degrees of nuance across different healthcare systems. While the overarching goal remains consistent—to deliver inpatient‐level care within the comfort and convenience of a patient's home—the pathways and tools to achieve this have demonstrated notable deviations.

3.2.1. Scope of services

While some institutions offer a comprehensive range of services, replicating almost all aspects of in‐hospital care, many are still developing thus offering limited services. 5 For instance, some models may exclusively focus on postsurgical care, while others might specialize in managing chronic illnesses. 13

3.2.2. Use cases

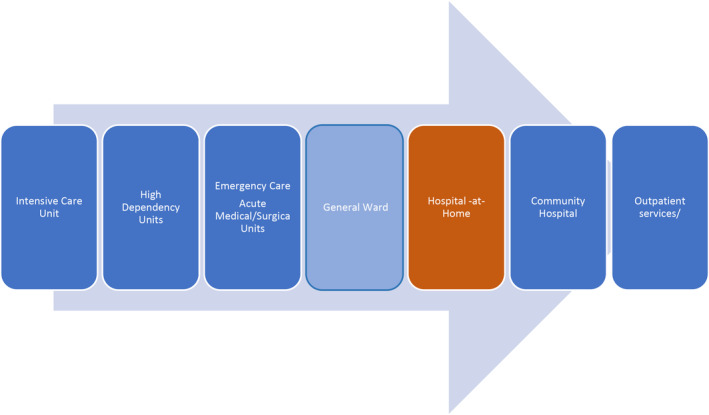

Hospital‐at‐home is an acute care delivered at patient's home. The level of acuity should be between inpatient care and postacute care traditionally delivered in community hospital (Figure 1). While there are some use‐cases that is suitable for Hospital‐at‐home, we believe that the patient selection should not just be disease or condition based but patient centric: not so ill that they cannot be safely managed at home, yet not so well that do not warrant admission.

FIGURE 1.

Level of acuity for Hospital‐at‐home.

3.2.3. Technology utilized

The extent and nature of technology adopted can vary widely. While some healthcare providers heavily rely on cutting‐edge telemedicine platforms, wearables, and AI tools, others might utilize a more conventional approach, leveraging phone calls and basic remote monitoring tools. 14 Future iterations may employ augmented and virtual reality tools for more immersive and thorough consultations, giving healthcare professionals better insights into patients' conditions from a distance. 15

3.2.4. Duration of care

The time frame for which the Hospital‐at‐home model is implemented can differ. Some programs may offer care for the entire duration of what would have been an inpatient stay (admission avoidance), while others provide a hybrid model, combining a few initial days in the hospital followed by early supported discharge.3, 16 Most centers deliver time‐limited interventions between 1 and 14 days. The median length of stay in of the pioneering center in Singapore was reported to be 4 days. 4

3.2.5. Logistical and operational models

The execution logistics, such as how medications are delivered, how emergency scenarios are handled, or how frequent in‐person visits are scheduled, can see significant deviations based on regional healthcare regulations, patient demographics, and available resources. 17

3.2.6. Reimbursement structures

Financial models supporting Hospital‐at‐home care differ substantially across countries and even within regions. While some systems offer a full reimbursement, similar to inpatient care, others might have differential pricing or might necessitate out‐of‐pocket expenditures by the patient. 18

3.3. How it is done at our hospital

Our hospital is in the initial phase of integrating Hospital‐at‐home models into modern healthcare delivery. To reap the potential benefits, we adapt our system that fuses traditional medical procedures with the demands of a home‐based environment. In the early phase of planning, guidance from other sites that have started Hospital‐at‐homes was sought. Subsequently, workgroup meetings were held with representations from admission office, bed management unit, business office, clinical governance, finance, IT support, laboratory, nursing informatics, and pharmacy to discuss on the processes and workflows.

3.3.1. Virtual beds

The concept of virtual beds was made in keeping with most Hospital‐at‐home institutions. This not only means care delivered to the patient's home but also implies a paradigm shift in managing hospital resources. Virtual beds, utilizing healthcare informatics, ensure that each patient is monitored just as they would be within the hospital's walls. This approach streamlines patient management, enhances resource allocation, and promotes efficient patient care, all from a remote setting. 19

3.3.2. Ward rounds

The Hospital‐at‐home model necessitates a revamp of the ward round protocol. Patients are scheduled for virtual ward rounds using telemedicine platforms, 20 with timings decided upon in mutual agreement. Sequential visits by multiple doctors are not encouraged in favor of consolidated virtual rounds. This ensures a seamless experience for the patient, reducing the hassle of repetitive engagements through teleconsult platforms.

The Hospital‐at‐home team actively engages in patient training sessions, ensuring that they are well versed with teleconsultation tools. When using the teleconsultation platform, some patients were asked to show pertinent body parts such as their leg for lower limb cellulitis (Figure 2) and the dorsum of the hand or forearm which was sited with the intravenous cannula. As some older adults have difficulty in using these tools, we engage their family members and involve them in caregiving at home. For certain medical assessments that necessitate physical touch, such as palpation or neurological evaluations, provisions for periodic home visits by medical personnel are established.

FIGURE 2.

Patient showing knee area during tele consultation.

Contrary to the usual practice of removing intravenous cannula before patients leave the hospital building, we made an exemption for this for patients admitted into Hospital‐at‐home as most of them needed intravenous therapy. Briefings were conducted in various departmental levels and nurses were reminded to keep the intravenous cannula should it is still patent to minimize unnecessary reinsertion.

Blood tests are collected by trained nurses and samples are quickly dispatched to hospital laboratory for prompt analysis. This is usually timed with tasks such as intravenous medication administration so that the home visits are optimized.

As x‐ray is a radiation emitting investigation, this cannot be performed at patients' homes because of existing regulations and safety. The hospital made provision where patients can be scheduled for such tests similarly to inpatients. Efficient scheduling coupled with responsive transportation logistics ensures patients are brought to and from the hospital with minimal hassle. Any delay or absenteeism may cause wastage in appointment slots in radiology.

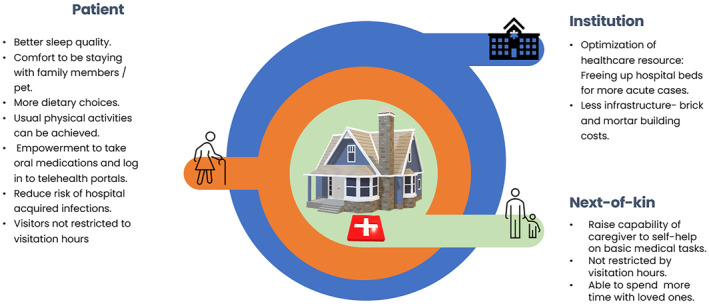

3.4. Tangible benefits of implementation

Hospital‐at‐home models have demonstrated many advantages over traditional inpatient care. These benefits cater to the psychological, physical, and logistical aspects of patient care, creating a holistic and efficient system that is patient centered. Some of the benefits (nonexhaustive) are illustrated in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Benefits of Hospital‐at‐home.

3.4.1. Activities of daily living

Being in a familiar environment has proven beneficial for the patient's well‐being.

Sleep quality

A fundamental human necessity, sleep is often disrupted in the sterile and unfamiliar hospital environment. In contrast, patients in their own homes often report better sleep quality, contributing to faster recovery and overall improved health outcomes. 21

Dietary habits

While hospital food is tailored to health needs, it may lack the appeal of homemade meals. With the Hospital‐at‐home model, patients are usually entrusted with following dietary guidelines, with assistance provided for those with specific needs or mobility issues. Personalized diet regimens catered to individual preferences can lead to better adherence and nutritional intake. 22 Provision of food from the hospital's central kitchen to homes remains a logistical challenge where menu ordering, preparation, delivery, and ensuring safe consumption within a specific time frame needs to be coordinated.

3.4.2. Patient empowerment

By placing the responsibility of certain aspects of care on the patient and their families, a sense of ownership and empowerment is fostered. 23

Self‐monitoring

Patients and their caregivers are trained to monitor and submit vital signs. This not only allows for timely interventions if anomalies are detected but also equips patients and families with skills and knowledge about their health conditions. 24

Medication management

In the Hospital‐at‐home setting, patients manage their oral medications, fostering a deeper understanding and adherence to their regimen. Any modifications are clearly communicated, ensuring that patients and caregivers are always in the loop and actively participating in the care process. 25

3.4.3. Economic and logistical benefits

Hospital‐at‐home models, when efficiently executed, can lead to reduced costs for both healthcare providers and patients.5, 6 Additionally, by freeing up hospital beds, healthcare systems can better allocate resources to those who need inpatient care the most.

3.5. Drawbacks and limitations

Despite its numerous benefits, the Hospital‐at‐home model presents several significant challenges and limitations that must be carefully considered during implementation. These challenges primarily revolve around patient reliance, timely escalation of care, the management of delirious patients, and the inherent limitations in its applicability to specific patient populations.

3.5.1. Reliance on patients and caregivers

A key drawback of the Hospital‐at‐home model is the increased reliance on patients and their family members or caregivers to manage essential care tasks. Responsibilities such as meal preparation, assistance with personal hygiene, monitoring and submitting vital signs, and maintaining communication with clinical providers can be overwhelming. Family members may need to take time off work or rearrange their schedules to provide adequate care. This creates an additional burden, especially in cases where caregivers lack the necessary flexibility or training to manage these tasks effectively.

3.5.2. Timely escalation of care

One of the most critical limitations of the Hospital‐at‐home model is the potential delay in escalating care when a patient's condition worsens. Despite thorough patient selection processes conducted by Hospital‐at‐home consultants in emergency departments and inpatient wards, some patients may experience a deterioration in their health during their time in the program. This could include complications such as hypotension, alarming diagnostic results, or new warning signs that require immediate attention. In such cases, patients may need to be transferred back to our hospital facility. While the program provides both emergency and nonemergency contact numbers, and patients are equipped with wrist tags containing hospital information, the logistics of managing acute deteriorations at home are not as robust as within a hospital setting, where immediate care can be provided.

3.5.3. Falls risk in delirious patients

While being in a familiar environment can aid in managing delirium, especially for patients prone to confusion and disorientation, the lack of constant supervision in the Hospital‐at‐home setting raises concerns for patients with hyperactive delirium and a high risk of falls. In a hospital, these patients benefit from around‐the‐clock monitoring by healthcare professionals who can intervene promptly if they exhibit signs of agitation or confusion. At home, even with family support, the ability to provide such close supervision is limited. This lack of constant oversight increases the likelihood of falls, which can lead to further complications, such as fractures or head injuries, and may necessitate emergency hospital transfers. For these high‐risk patients, the safety provided by a controlled hospital environment may outweigh the benefits of home care, making the Hospital‐at‐home model unsuitable for them.

3.5.4. Use case limitations

The Hospital‐at‐home model is not suitable for all patients, especially those with conditions requiring continuous or frequent monitoring. Patients who are critically ill and need close monitoring of their vital signs, or those who cannot effectively communicate via telecommunication platforms, may not be appropriate candidates for the program. Furthermore, the absence of lived‐in caregivers, particularly for elderly or disabled patients, can limit the feasibility of home‐based care. Patients who cannot self‐monitor or lack family support may be better managed in a traditional inpatient setting.

3.5.5. Technological and logistical constraints

Although technology plays a pivotal role in the success of the Hospital‐at‐home model, its limitations must be acknowledged. Not all patients are comfortable using telemedicine platforms, and certain medical assessments, such as palpation or neurological evaluations, require physical interaction, which telemedicine cannot provide. While periodic home visits by medical personnel can address some of these issues, they may not always be timely or adequate. Additionally, diagnostic tests such as x‐rays cannot be performed at home because of safety and regulatory concerns, necessitating patient transportation to a hospital or diagnostic facility, which can introduce delays and disrupt care continuity.

3.5.6. Cost and reimbursement issues

While Hospital‐at‐home models are often touted for their cost‐effectiveness, they may require significant upfront investment in technology, training, and logistical support. Furthermore, reimbursement models vary widely across regions, with some systems offering full coverage akin to traditional hospital care, while others impose out‐of‐pocket expenses on patients. These financial disparities can impact the model's accessibility and long‐term sustainability, particularly in lower income populations or regions with less robust healthcare financing frameworks.

3.6. In alignment with shift toward community care

In recent years, there has been a distinct transformation in the medical landscape, with a pronounced shift toward community‐based care. This change is not only reflected in the rising presence and preference for the Hospital‐at‐home model but is also seen in the broader integration of community resources into the healthcare continuum. The shift toward community care is not merely a reactionary response to healthcare system constraints but a deliberate move rooted in evidence‐based benefits for patients, healthcare providers, and the system at large.

Hospital‐at‐home is only one of the numerous community‐based programs that have surged in adoption. Others include outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), home‐based palliative care, and mobile health clinics. 26 These models prioritize care outside traditional hospital settings, emphasizing the benefits of treating patients in familiar, comfortable environments. While these transformations pose challenges, the potential benefits for patients, providers, and the broader healthcare system make it a change worth embracing.

4. CONCLUSION

While some of the descriptions here may be aspirational, the medical landscape is amid transformative change, nevertheless. As illustrated throughout this exploration, the Hospital‐at‐home model offers a compelling blueprint for what the future of acute care might look like. This model seamlessly merges the comforts of a home setting with the rigorous medical care associated with traditional hospital settings, making it a symbol of modern patient‐centric care.

Despite the promising advancements in healthcare technology, it is paramount that the core tenets of the Hospital‐at‐home model remain intact. Central to its success is the prioritization of patient safety, comfort, autonomy, and holistic well‐being. As technology and processes evolve, healthcare providers must always circle back to these foundational principles, ensuring that patients not only receive top‐tier medical care but also feel valued, heard, and central to their care journey.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

The subject gave informed consent (Figure 2) and patient anonymity is preserved. This review is in compliant with ethical exemption, CIRB Ref. No.: 2024/2252.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the SKH@Home workgroup committee and team, patients, vendor team, SGH@Home, KHome, CGH@Home, and MOHT.

Wong HLM, Ong CY, Ngo HJ, Yeo SS, Lee MHJ. An overview of Hospital‐at‐home versus other models of care. J Gen Fam Med. 2025;26:19–26. 10.1002/jgf2.742

Chong Yau Ong: co‐first author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zimbroff RM, Ornstein KA, Sheehan OC. Home‐based primary care: a systematic review of the literature, 2010–2020. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(10):2963–2972. 10.1111/jgs.17365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “Hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514–517. 10.1056/nejm199608153350713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shepperd S, Iliffe S, Doll HA, Clarke MJ, Kalra L, Wilson AD, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2016;2016(9):CD007491. 10.1002/14651858.cd007491.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ko SQ, Goh J, Tay YK, Nashi N, Hooi BM, Luo N, et al. Treating acutely ill patients at home: data from Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2022;51(7):392–399. 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.2021465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Coast J, Richards SH, Peters TJ, Gunnell DJ, Darlow M‐A, Pounsford J. Hospital at home or acute hospital care? A cost minimisation analysis. BMJ. 1998;316(7147):1802–1806. 10.1136/bmj.316.7147.1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cryer L, Shannon SB, Van Amsterdam M, Leff B. Costs for ‘hospital at home’ patients were 19 percent lower, with equal or better outcomes compared to similar inpatients. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1237–1243. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ang YH, Ginting ML, Wong CH, Tew CW, Liu C, Sivapragasam NR, et al. From hospital to home: impact of transitional care on cost, hospitalisation and mortality. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2019;48(10):333–337. 10.47102/annals-acadmedsg.v48n10p333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parker SG, Peet SM, McPherson A, Cannaby AM, Abrams K, Baker R, et al. A systematic review of discharge arrangements for older people. Health Tech Assess. 2002;6(4):1–183. 10.3310/hta6040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Montalto M, Ko SQ. Telling the difference and the telling differences between hospital in the home and outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Intern Med J. 2022;52(5):880–884. 10.1111/imj.15780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chapman AL, Seaton RA, Cooper MA, Hedderwick S, Goodall V, Reed C, et al. Good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults in the UK: a consensus statement. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(5):1053–1062. 10.1093/jac/dks003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B, Rosati RJ, McCann BA, Hornbake R, et al. The future of home health care. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2016;28(4):262–278. 10.1177/1084822316666368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gomes B, Higginson IJ. Factors influencing death at home in terminally ill patients with cancer: systematic review. BMJ. 2006;332(7540):515–521. 10.1136/bmj.38740.614954.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Conley J, O'Brien CW, Leff BA, Bolen S, Zulman D. Alternative strategies to inpatient hospitalization for acute medical conditions. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1693–1702. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Totten A, Womack DM, McDonagh MS, Davis O'Reilly C, Griffin JC, Blazina I, et al. Improving rural health through telehealth‐guided provider‐to‐provider communication. 2022. 10.23970/ahrqepccer254 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. Dorsey ER, Topol EJ. State of telehealth. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):154–161. 10.1056/nejmra1601705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leong MQ, Lim CW, Lai YF. Comparison of hospital‐at‐home models: a systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e043285. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Montalto M. Patients' and Carers' satisfaction with hospital‐in‐the‐home care. International J Qual Health Care. 1996;8(3):243–251. 10.1093/intqhc/8.3.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Federman AD, Soones T, DeCherrie LV, Leff B, Siu AL. Association of a bundled hospital‐at‐home and 30‐day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1033–1040. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leff B. Hospital at home: feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital‐level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Int Med. 2005;143(11):798–808. 10.7326/0003-4819-143-11-200512060-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith AC, Thomas E, Snoswell CL, Haydon H, Mehrotra A, Clemensen J, et al. Telehealth for global emergencies: implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). J Telemed Telecare. 2020;26(5):309–313. 10.1177/1357633x20916567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fogg C, Griffiths P, Meredith P, Bridges J. Hospital outcomes of older people with cognitive impairment: an integrative review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(9):1177–1197. 10.1002/gps.4919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hickson M. Malnutrition and ageing. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(963):2–8. 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ong CY, Lee WD, Low SG, Low LL, Vasanwala F. Attitudes and perceptions of people with diabetes mellitus on patient self‐management in diabetes mellitus: a Singapore hospital's perspective. Singapore Med J. 2023;64(7):467–474. 10.11622/smedj.2022006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Shaw S, Morrison C. Video consultations for Covid‐19. BMJ. 2020;368:m998. 10.1136/bmj.m998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, et al. Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(4):430–439. 10.1016/j.arr.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leff B, Burton JR. The future history of home care and physician house calls in the United States. J Gerontol Series A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(10):M603–M608. 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]