Abstract

The centromere effect (CE) is a meiotic phenomenon that ensures meiotic crossover suppression in pericentromeric regions. Despite being a critical safeguard against nondisjunction, the mechanisms behind the CE remain unknown. Previous studies have shown that various regions of the Drosophila pericentromere, encompassing proximal euchromatin, beta and alpha heterochromatin, undergo varying levels of crossover suppression, raising the question of whether distinct mechanisms establish the CE in these different regions. To address this question, we asked whether different pericentromeric regions respond differently to mutations that impair various features that may play a role in the CE. In flies with a mutation that affects the synaptonemal complex (SC), a structure is hypothesized to have important roles in recombination and crossover patterning, we observed a significant redistribution of pericentromeric crossovers from proximal euchromatin towards beta heterochromatin but not alpha heterochromatin, indicating a role for the SC in suppressing crossovers in beta heterochromatin. In flies mutant for mei-218 or rec, which encode components of a critical pro-crossover complex, there was a more extreme redistribution of pericentromeric crossovers towards both beta and alpha heterochromatin, suggesting an important role for these meiotic recombination factors in suppressing heterochromatic crossovers. Lastly, we mapped crossovers in flies mutant for Su(var)3–9. Although we expected a strong alleviation of crossover suppression in heterochromatic regions, no changes in pericentromeric crossover distribution were observed in this mutant, indicating that this vital heterochromatin factor is dispensable to prevent crossovers in heterochromatin. Our results indicate that the meiotic machinery plays a bigger role in suppressing crossovers than the chromatin state.

Introduction

During the first meiotic division, recombination between homologous chromosomes is a crucial process that is required to promote their accurate segregation away from one another. Meiotic crossovers are a highly regulated phenomenon, with the meiotic cell tightly governing where along each chromosome crossovers can form. The rules that control crossover placement are commonly referred to as crossover patterning events and are an additional requirement in ensuring that homologs disjoin correctly during meiosis.

Of the various meiotic crossover patterning events that have been established (Sturtevant 1913; Beadle 1932; Owen 1950; Martini et al. 2006); reviewed in (Pazhayam et al. 2021)), the exclusion of crossovers near the centromere - commonly referred to as the centromere effect (CE) - occurs animals, fungi, and plants (Mahtani and Willard 1998; Copenhaver et al. 1999; Wu et al. 2003; Ghaffari et al. 2013; Vincenten et al. 2015; Nambiar and Smith 2016; Fernandes et al. 2024). Studies in both Drosophila and humans have shown a correlation between centromere-proximal crossovers and nondisjunction (Koehler et al. 1996; Lamb et al. 1996; Oliver et al. 2012).

Despite the importance of the CE in protecting against meiotic NDJ, little is known about how the CE is established or maintained. Studies that have looked at the Drosophila CE over the past century have largely attempted to establish the centromere or pericentromeric heterochromatin as being the final arbiter of crossover prevention in this region, but failed to reach a definitive conclusion (Mather 1939; Slatis 1955; Yamamoto and Miklos 1978; John 1985; Westphal and Reuter 2002; Mehrotra and Mckim 2006). Whether the CE is controlled by one primary mechanism of action, or several factors that must act together to suppress recombination in the region remains an unanswered question in the field, as does the identity and nature of these factors. Although the centromere effect has largely remained a mechanistic mystery since its discovery, certain modes of control have been ruled out in D. melanogaster. Disruption of centromere clustering, changes in centromere number, and changes in repetitive DNA dosage were shown to no trans-acting effects on the strength of the CE (Pazhayam et al. 2023).

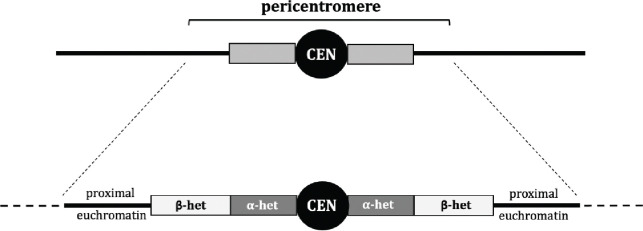

The pericentromeric region in Drosophila melanogaster, as well as many other organisms including mammals, Arabidopsis, and fission yeast consists of a centromere embedded in large chunks of heterochromatinized repetitive DNA (Miklos and Cotsell 1990; Simon et al. 2015; Ghimire et al. 2024). Pericentromeric heterochromatin in Drosophila is heterogeneous (Figure 1), comprising two classes defined by sequence, staining patterns, and replication status. This is most clearly seen in polytene chromosomes, where the centromeres are embedded in regions that are densely staining and highly under-replicated, and the adjacent regions are more diffusely stained and are less under-replicated (Gall et al. 1971; Miklos and Cotsell 1990). The former, referred to as alpha heterochromatin, are composed largely of tandem arrays of highly repetitive satellite DNA sequences. The moderately stained regions, referred to as beta heterochromatin, are found between alpha heterochromatin and euchromatin, and have a high density of transposable elements interspersed within unique sequence. The unique sequences found in beta heterochromatin have made it possible to assemble much of it to the reference genome (Hoskins et al. 2015), whereas the alpha heterochromatin has not yet been assembled.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the pericentromere region in D. melanogaster. Grey boxes indicate pericentromeric heterochromatin and thick black lines indicate euchromatin. In the lower image, the centromere indicated as CEN, alpha heterochromatin as α-het, and beta heterochromatin as β-het. Dashed lines indicate euchromatin that is not considered centromere-proximal and therefore excluded from our definition of the pericentromere.

These two classes of centromere-proximal heterochromatin also differ in crossover-suppression patterns. Hartmann et al. (2019) showed that in wild-type flies, meiotic crossovers are completely absent from alpha-heterochromatic regions, whereas crossover frequencies in beta heterochromatin and proximal euchromatin depend on distance from the centromere (Hartmann et al. 2019b). A similar pattern of centromere-proximal crossover suppression has been described in Arabidopsis thaliana (Fernandes et al. 2024), where the pericentromere is organized similarly to that D. melanogaster, with the centromere embedded in regions of highly repetitive heterochromatinized DNA that give way to less repetitive heterochromatinized DNA, followed by unique euchromatic sequence.

The existence of these two components of the CE raises the question of how they are established during meiosis, and whether distinct processes are responsible for their establishment and execution. It has been previously speculated that the “controlling systems” preventing crossovers in centromere-proximal euchromatin are different from those that prevent crossovers in pericentromeric heterochromatin (Carpenter and Baker 1982a; Szauter 1984), leading us to attempt to tease apart the mechanistic differences in proximal crossover suppression within the various regions of the pericentromere, including any - if they exist - between alpha and beta heterochromatin.

Evidence for centromere-proximal crossover suppression being a meiotically controlled phenomenon is abundant, and since the meiotic program is not a monolith, we focused on two facets: the synaptonemal complex (SC) and the proteins directing meiotic recombination. The SC is a protein structure that forms during meiosis between paired homologs and is the context within which meiotic recombination occurs. SC has been shown to be necessary for crossover formation as well as patterning in many species (Sym and Roeder 1994; Storlazzi et al. 1996; Page and Hawley 2001; Libuda et al. 2013; Voelkel-Meiman et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2015; Voelkel-Meiman et al. 2016; Billmyre et al. 2019). It has been proposed that the SC has liquid crystalline properties that helps mediate crossover designation and interference by providing a compartment within with the proteins that carry out these processes can diffuse (Morgan et al. 2021; Zhang et al. 2021; Von Diezmann et al. 2024). SC in pericentromeric heterochromatin has been reported to have morphological differences from the SC along euchromatin (Carpenter 1975). A 2019 study showed that the Drosophila SC component C(3)G plays a definitive role in suppressing pericentromeric crossovers (Billmyre et al. 2019). Collectively, these observations suggest the SC may have a crucial role in establishing the CE.

The second facet is the proteins that direct meiotic recombination. Hatkevich et al. (2017) showed that loss of Bloom syndrome helicase, an important DNA repair protein, lacked not only the CE, but also other forms of crossover patterning such as interference (Hatkevich et al. 2017). A 2018 study showed that the introduction of D. mauritiana orthologs of the pro-crossover genes mei-217 and mei-218 into D. melanogaster mei-218 mutants attenuated crossover suppression around the centromere, as it is in D. mauritiana, suggesting that these genes mediate the strength of the CE in D. melanogaster (Brand et al. 2018). Mei-217 and Mei-218 are components of the meiotic-mini-chromosome-maintenance (mei-MCM) complex that is hypothesized the block the anti-crossover activity of Blm (Kohl et al. 2012) Analysis of the data of Hartmann et al. (2019) suggests that both mei-218 and rec, which encodes the third component of the mei-MCM complex, may contribute to crossover suppression around the centromere. This, and data from other organisms showing genetic modes of suppressing pericentromeric crossovers through blocking or preventing Spo11-mediated meiotic DSBs (Vincenten et al. 2015; Nambiar and Smith 2018; Xue et al. 2018), suggests that the meiotic program is able to exert considerable control over the CE.

The heterochromatic nature of the pericentromere could also be a key factor contributing to the CE. Crossover suppression within heterochromatin as well as an effect of heterochromatin on crossover suppression in adjacent regions have previously been shown in Drosophila and other organisms (Slatis 1955; John 1985; Hartmann et al. 2019a; Fernandes et al. 2023; Fernandes et al. 2024). Westphal & Reuter (Westphal and Reuter 2002) observed elevated centromere-proximal crossovers in a several suppressor-of-variegation mutants that impact chromatin structure. Three of the Su(var) mutants in their study mapped to genes encoding proteins necessary for heterochromatin formation and maintenance, including HP1 (Su(var)2–5) and H3K9 methyltransferase (Su(var)3–9), as well as their accessory proteins (Su(var)3–7). Peng & Karpen (2009) showed that a hetero-allelic Su(var)3–9 mutant had elevated DSBs in meiotic cells that colocalized with alpha-heterochromatic sequences, suggesting that Su(var)3–9 is crucial to keeping DSBs out of alpha heterochromatin during meiosis. Together, these data suggest that the inherent heterochromatic nature of large portions of the pericentromere contributes to crossover suppression within it.

In this study, we measured centromere-proximal crossover frequencies, the strength of the CE, and crossover distribution patterns within different regions of the pericentromere: proximal euchromatin, beta heterochromatin, and alpha heterochromatin (Figure 1). We investigated three classes of mutants: structural (SC), meiotic, and heterochromatic. If multiple modes of crossover control are required to act in synchrony to suppress crossovers in centromere-proximal regions, we hypothesized that we would observe differences in where the CE is disrupted in each mutant class. The structural mutant we looked at was a c(3)G in-frame deletion mutant that leads to failure to maintain full-length SC by mid-pachytene (Billmyre et al. 2019). We observed significant CE defects on chromosome 2 in this mutant, along with a considerable redistribution of crossovers away from proximal euchromatin, towards beta but not alpha heterochromatin. This suggests that full length SC at mid-pachytene is required to suppress crossovers in beta heterochromatin. We also looked at mutants lacking mei-218 and rec, which are crucial for crossover formation and patterning but have no known roles outside of meiosis/DNA repair (Carpenter and Baker 1982a; Hartmann et al. 2019a). Upon establishing that both mutants have a significantly weakened CE, we found a significant increase in heterochromatic crossovers in both beta and alpha heterochromatin at the expense of crossovers in proximal euchromatin. Surprisingly, the heterochromatic mutant in our study - Su(var)3–9null - turned out to be dispensable not only for centromere-proximal crossover suppression, but also for preventing crossovers specifically in pericentromeric heterochromatin, as no significant redistribution of crossovers was observed between proximal euchromatin and pericentromeric heterochromatin. As Su(var)3–9 is a gene crucial for heterochromatinization at the pericentromere (Schotta et al. 2002) and is also implicated in preventing meiotic crossovers in heterochromatin (Westphal and Reuter 2002), this result implies that chromatin-based steric hindrance/inaccessibility do not play as big of a role in keeping crossovers out of heterochromatic regions as various classes of meiotic factors necessary for crossover designation and patterning do.

Our results suggest that while the cell seems to require multiple facets of control to exclude crossovers in centromere-proximal regions during meiosis, the CE is a primarily meiotic phenomenon in Drosophila, with the meiotic program – both the structure providing the conduit for proteins that carry out recombination and the recombination proteins themselves – seemingly superseding heterochromatin in preventing heterochromatic crossovers.

Results

Synaptonemal complex protein C(3)G is necessary for centromere-proximal crossover suppression during meiosis

The synaptonemal complex is a protein structure that forms specifically between paired homologs during meiosis. In Drosophila, the SC is formed before meiotic DSBs are induced, and plays a crucial role in both DSB and crossover formation (Page and Hawley 2001; Mehrotra and Mckim 2006; Lake and Hawley 2012; Collins et al. 2014), as well as crossover patterning (Billmyre et al. 2019). To ask how important the Drosophila SC is in establishing the centromere effect, we measured recombination in a mutant defective for SC maintenance. c(3)GccΔ2 is a deletion the removes residues 346–361 from the coiled-coil domain of the transverse filament (Billmyre et al. 2019). This mutation results in loss of the SC structure by mid-pachytene. Interestingly, c(3)GccΔ2 flies display elevated centromere-proximal crossovers on chromosome 3, which has a strong CE, but not on chromosome X, which has a weak CE, suggesting that C(3)G and a full-length SC are necessary to maintain a robust CE.

We asked whether C(3)G is important for pericentromeric crossover suppression on chromosome 2 as well by measuring crossover frequencies within a ~40 Mb region that spans the centromere an includes euchromatin, beta heterochromatin, and alpha heterochromatin. Female flies heterozygous for markers on both arms of chromosome 2 were used to map recombination between the distal 2L locus net and the proximal 2R locus cinnabar (cn). The centromere on chromosome 2 lies in the interval between markers purple (pr) on 2L and cn on 2R, covering an approximate length of 20.5 Mb, including 11.2 Mb of assembled sequence and an estimated 4 Mb of alpha heterochromatin on 2L and 5.3 Mb on 2R.

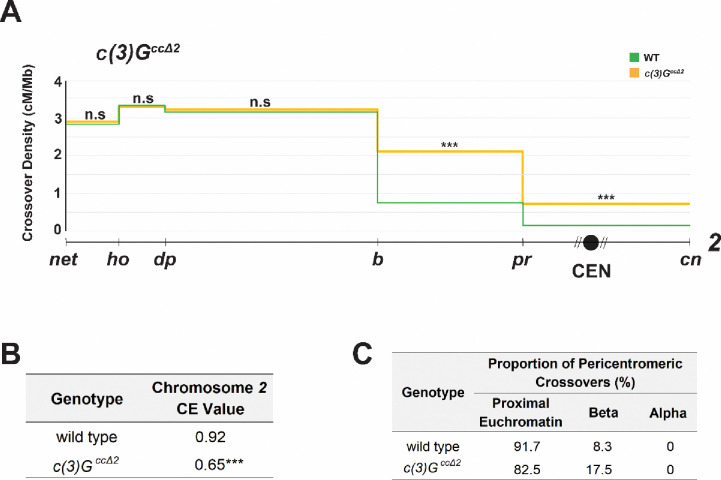

Figure 2A shows crossover density along chromosome 2 (divided into five intervals by six recessive marker alleles) in wild-type flies and in c(3)GccΔ2 mutants. Total genetic length in this mutant is significantly increased in the mutant, from 48.05 cM in wild type to 64.01 cM (p<0.0001). While crossover distributions closely resemble wild-type in the three distal and medial intervals interval 2, crossover frequencies in the interval spanning the centromere (pr - cn) and the adjacent interval (b - pr) are significantly increased in the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant (p<0.0001; Figure 2A). This suggests that chromosome 2, like chromosome 3, experiences a weaker centromere effect in this mutant.

Figure 2.

A. Crossovers in c(3)GccΔ2 (n = 5,918) and wild-type (n = 4,331) flies along chromosome 2 with the Y-axis indicating crossover density in cM/Mb and the X-axis indicating physical distances between recessive marker alleles that were used for recombination mapping. The chromosome 2 centromere is indicated by a black circle, unassembled pericentromeric repetitive DNA by diagonal lines next to it. A 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate statistical significance between mutant and wild-type numbers of total crossovers versus parentals in each interval. Complete dataset is in Supplementary Table S1. n.s p > 0.01, *p < 0.01, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002 after correction for multiple comparisons. B. Table showing CE values on chromosome 2 in wild type and c(3)GccΔ2 flies. ***p < 0.0002. C. Table showing percentage of pericentromeric crossovers that occurred within each region of the pericentromere in wild type vs c(3)GccΔ2 mutant flies. Supplementary Figure S1 contains gel images of allele-specific PCRs for each SNP defining the boundaries of pericentromeric regions.

Since crossover frequencies measured in cM/Mb are based only on observed crossover numbers, we calculated a CE value that also takes into account crossover numbers expected if there no centromere-proximal suppression during meiotic recombination. This value considers crossover density in the centromeric interval as equal to the average density of the entire chromosome 2 region being studied and is a more biologically relevant measure of the CE as it is agnostic to differences in total crossover numbers between two genotypes.

WT flies have a CE value of 0.92 on chromosome 2 (Pazhayam et al. 2023), whereas the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant has a significantly lower CE value of 0.65 (p<0.0001; Figure 2B), consistent with a strong defect in the CE. This suggests that the maintenance of full-length SC throughout pachytene is essential for ensuring vigorous suppression of centromere-proximal meiotic crossovers in Drosophila.

The synaptonemal complex protein C(3)G is necessary for crossover suppression in beta but not alpha heterochromatin

On observing that the Drosophila SC component C(3)G is crucial for centromere-proximal crossover suppression on chromosome 2, we asked whether it plays a role in the distribution of crossovers across the various regions of the pericentromere. To determine this, we built flies of the desired mutant background that were heterozygous for isogenized net-cn and wild-type chromosomes. Through Illumina sequencing, we identified SNPs between these chromosomes, allowing us to fine map crossovers within the larger intervals defined by phenotypic markers. We collected every fly that had a crossover between pr and cn and, through allele-specific PCR, mapped the crossover to proximal euchromatin or beta heterochromatin on either arm, or to alpha heterochromatin. We defined beta heterochromatin as the region between where the H3K9me3 mark begins (Stutzman et al. 2024) and the most proximal SNPs on the current assembly (release 6.59 of the D. melanogaster reference genome). Alpha heterochromatin was defined as the region between the most proximal SNPs on 2L and 2R.

Intriguingly, the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant displayed a significant redistribution of crossovers across two of the three proximal regions. The distribution in this mutant, measured as percentages of total crossovers across the chromosomal region being studied, were significantly increased from wild type in proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin (Table 1). While only ~2.7% of total crossovers on chromosome 2 form in proximal euchromatin in WT flies, c(3)GccΔ2 mutants had ~4.1% of total chromosome 2 crossovers now found in this region (p=0.0012). Similarly, ~0.9% crossovers in c(3)GccΔ2 mutants are found in beta heterochromatin, a significant (p=0.0002) increase from the ~0.2% observed in wild-type flies (Table 1). Curiously, we observed no crossovers mapping to the region between our most proximal SNPs on 2L and 2R, meaning that no crossovers occurred in alpha heterochromatin, as in wild-type flies (Table 1). This suggests that while SC mutants are unable to maintain wild-type levels of crossover suppression in beta heterochromatin, they are as successful as wild-type flies in suppressing crossovers in alpha heterochromatin.

Table 1.

Percentage of crossovers in the region of chromosome 2 being studied that occurred within each section of the pericentromere in wild type (WT) and mutants.

| Genotype | Flies | Crossovers | Percentage of Chromosome 2 Crossovers |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proximal Euchromatin | Beta Heterochromatin | Alpha Heterochromatin | |||

|

| |||||

| WT | 4331 | 2081 | 2.69 | 0.24 | 0 |

|

| |||||

| c(3)GccΔ2 | 5918 | 3788 | 4.05** | 0.86*** | 0 |

| mei-218null | 12,339 | 284 | 10.21**** | 3.87**** | 0.35 |

| recnull | 16,776 | 848 | 10.97**** | 5.31**** | 0.94**** |

| Su(var)3–906/+ | 10,154 | 4871 | 2.24 | 0.16 | 0 |

|

| |||||

| Su(var)3–9null | 8123 | 4289 | 2.98 | 0.37 | 0.02 |

p<0.01

p<0.001

p<0.0001.

All others p >0.05.

We also calculated crossover frequencies in each region of the pericentromere as a percent of total pericentromeric crossovers in this mutant (Figure 2C), and observed a statistically significant redistribution from proximal euchromatin towards beta (p=0.0268) but not alpha heterochromatin (p=1.000), compared to WT.

Collectively, these data indicate that full length SC during mid-pachytene plays a role in maintaining wild-type levels of crossover suppression at the pericentromere (Figure 2A, 2B) as well as wild-type proportions of crossovers within proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin but is dispensable for crossover suppression within alpha heterochromatin (Figure 2C, Table 1).

Meiotic recombination genes are necessary for centromere-proximal crossover suppression

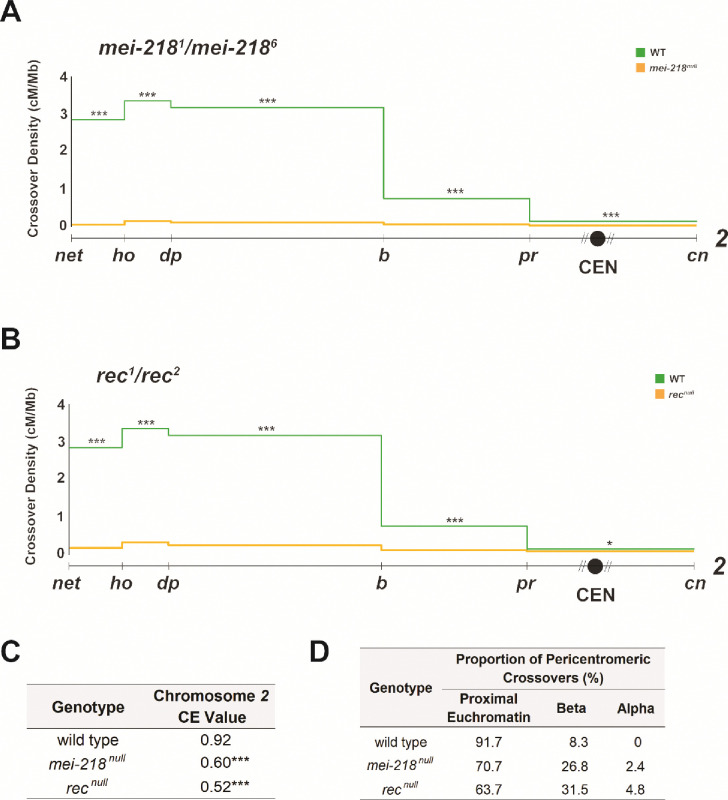

Crossovers during meiosis are controlled by a meiotic program that designates and likely also patterns their formation along the length of the chromosome. To measure the influence of the meiotic program on centromere-proximal crossover suppression and the strength of the centromere effect, we first looked at a null mutant of the meiotic pro-crossover gene mei-218, which encode a component of the meiotic-mini-chromosome maintenance (mei-MCM) complex (Kohl et al. 2012). Mei-218 is crucial for the formation and patterning of meiotic crossovers (Baker and Carpenter 1972; Brand et al. 2018; Hartmann et al. 2019a). We addressed the role of mei-218 in exerting the centromere effect by measuring recombination along chromosome 2, between the markers net and cinnabar. Crossover density in mei-218 null mutants is shown in Figure 3A. Consistent with its crucial role in crossover formation during meiosis, the mei-218 mutant had a significantly reduced genetic length (2.30 cM, p<0.0001) along the chromosome 2 region being studied than wild-type flies did (48.05 cM). Notably, the distribution of crossovers along the chromosome in mei-218 mutants appears to be almost flat, substantially different from the usual bell curve observed in wild-type flies. The genetic length of the interval containing the centromere was either close to or higher than crossover frequencies along the rest of the chromosome in this mutant, indicating an impaired centromere effect (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) Crossovers in mei-218null (n = 12,339) and wild-type (n = 4,331) flies along chromosome 2 with the Y axis indicating crossover density in cM/Mb and the X axis indicating physical distances between recessive marker alleles that were used for recombination mapping. The chromosome 2 centromere is indicated by a black circle, unassembled pericentromeric repetitive DNA by diagonal lines. B. Crossovers in recnull (n = 16,776) and wild-type (n = 4,331). C. CE values on chromosome 2 in wild-type, mei-218null, and recnull flies. D. Table showing percentage of pericentromeric crossovers that occurred within each region of the pericentromere in WT, mei-218null, and recnull flies. For all panels, a 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate statistical significance between mutant and wild-type numbers of total recombinant versus non-recombinants in each interval (see Table S1 for complete datasets). n.s. p > 0.01, *p < 0.01, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002, after correction for multiple comparisons. Supplementary Figure S1 contains gel images of allele-specific PCRs for each SNP defining the boundaries of pericentromeric regions.

The mei-218 mutant had a CE value of 0.60 on chromosome 2 (Figure 3C), a significant decrease from the WT chromosome 2 CE value of 0.92 (p<0.0001), further suggesting a very weak centromere effect in this mutant, consistent with what was observed by Hartman et al. (Hartmann et al. 2019a). Combined with the flat distribution of crossovers observed in this mutant, mei-218 appears to be essential in establishing a robust suppression of crossovers near the centromere during meiosis.

To ask whether this importance in centromere-proximal crossover suppression extended to other pro-crossover meiotic genes, we also studied mutants defective for rec, which encodes another mei-MCM component (Kohl et al. 2012). Figure 3B shows crossover density along chromosome 2 in rec null mutants, which also show a significant decrease in genetic length (5.05 cM; p<0.0001) from the wild-type level. Crossovers in this mutant followed the pattern of the mei-218 mutant, with a much flatter distribution observed along the chromosome than in wild-type flies. The genetic length of the interval spanning the centromere was once again higher than or much closer to the genetic lengths of intervals in the middle of the chromosome arm, suggesting that rec mutants also have a diminished centromere effect. This is further corroborated by the CE value of rec mutant flies (0.52), significantly reduced from WT chromosome 2 CE value of 0.92 (p<0.0001) (Figure 3C), indicating that Rec is also crucial for maintaining a strong centromere effect. Overall, these results demonstrate that genes encoding two components of the mei-MCM complex - mei-218 and rec - are independently necessary to ensure that crossovers form at the right frequencies, and to guarantee centromere-proximal crossover suppression in Drosophila.

Meiotic recombination genes are necessary for crossover suppression in alpha and beta heterochromatin

On observing that the meiotic mutants rec and mei-218 both have an ablated CE, we asked whether these genes are also necessary to maintain wild-type patterns of crossover distribution within the pericentromere. Hartmann et al. (2019b) previously fine mapped centromere-proximal crossovers in Blm mutants, which also lack a functional CE, and observed a flat crossover distribution that extended into proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin, but never into alpha heterochromatin. They concluded that Blm is necessary to maintain the distance-dependent CE observed in beta heterochromatin and proximal euchromatin, but that the complete suppression of crossovers observed in alpha heterochromatin is likely due to the region not being under genetic/meiotic control, hypothesizing instead that highly repetitive regions do not experiencing meiotic DSBs.

This pattern of crossover redistribution in Blm mutants is similar to what we observed in the SC mutant c(3)GccΔ2 is consistent with an important contribution of the SC in regulating meiotic recombination. Since the CE in both rec and mei-218 mutants is weakened much like in Blm and c(3)GccΔ2 mutants, we sought to ask if fine mapping crossovers within the pericentromere in mei-218 and rec mutants would reveal the same patterns of crossover redistribution observed in Blmnull and c(3)GccΔ2 flies. Surprisingly, pericentromeric crossover distribution patterns in the mei-218 and rec mutants were different from both Blm and c(3)GccΔ2 mutants. In mei-218 mutants, 10.2% of total chromosome 2 crossovers were within proximal euchromatin, a significant increase from both the WT value of 2.7% in this region, as well as the c(3)GccΔ2 value of 4.05% (p<0.0001 for both comparisons). Similarly, 3.9% of total crossovers in mei-218 mutants form in beta heterochromatin, also a significant increase compared to wild-type (p<0.0001) and c(3)GccΔ2 (p=0.0002) flies (Table 1).

Interestingly, we observed an increase in crossover frequencies in the region described as alpha heterochromatin, with 0.4% of total chromosome 2 crossovers in mei-218 mutants forming between our most proximal SNPs, compared to none in both wild-type and SC mutant flies (Table 1). The increase isn’t statistically significant (p = 0.35), but statistical power is limited by the severe reduction in total crossovers in mei-218 leading to few pericentromeric crossovers (41 from >12,000 flies scored). Because we never saw a crossover between the most proximal SNPs in wild type (n=132), the increase observed in the mei-218 mutant may be biologically relevant.

We then looked at pericentromeric crossover distributions in the rec mutant and observed similar patterns to those of the mei-218 mutant. When compared to wild type, crossover frequencies, measured as a percent of total crossovers across chromosome 2, were increased in all three regions of rec mutants (Table 1). crossover frequencies increased to ~11% in proximal euchromatin, ~5.3% in beta heterochromatin, and ~0.9% in alpha heterochromatin, all significant (p<0.0001) changes from crossover frequencies in the respective pericentromeric regions of wild-type and SC mutant flies.

We also calculated crossover frequencies as a percent of total pericentromeric crossovers (Figure 3D) and observed a statistically significant redistribution from proximal euchromatin towards beta heterochromatin in both mei-218 (p=0.0049) and rec (p<0.0001) mutants, compared to wild-type flies. Compared to c(3)GccΔ2 flies, mei-218 mutants did not exhibit a significant redistribution of crossovers from proximal euchromatin to beta heterochromatin (p=0.1824), but rec mutants did (p=0.0032). rec mutant flies also displayed a highly significant redistribution of pericentromeric crossovers from proximal euchromatic regions towards alpha heterochromatin, compared to both wild-type (p=0.0016) and SC mutant (p=0.0008) flies.

Collectively, these results suggest that when the mei-MCM complex is lost, there is a significant repositioning of crossovers within the pericentromere, compared to both wild type and the SC mutant in our study. More specifically, we observe a clear redistribution of pericentromeric crossovers away from proximal euchromatin and into both alpha and beta heterochromatin. Centromere-proximal crossovers in both mutants can reach further into pericentromeric heterochromatin than in wild-type, Blm mutant, or SC mutant flies, indicating not only a weakening of the strength of the CE but also its reach along the chromosome. This is particularly striking, as heterochromatic crossover suppression has been widely thought to happen through non-meiotic mechanisms (Carpenter and Baker 1982b; Szauter 1984; Westphal and Reuter 2002; Mehrotra and Mckim 2006), possibly through heterochromatinization and steric hindrances to DSB and recombination machinery. We had expected to see increases in crossovers within pericentromeric heterochromatin only in mutants of important heterochromatin genes. Instead, crossovers within heterochromatin seem to unambiguously be under meiotic control.

Su(var)3–9 is dispensable for centromere-proximal crossover suppression during meiosis

On observing that the meiotic machinery – in the form of both SC and recombination proteins – is necessary to prevent heterochromatic crossovers, we asked what pericentromeric crossover distributions look like in a heterochromatin mutant. As the majority of the chromosomal region described as the pericentromere is heterochromatic, we wanted to investigate whether mutations in genes necessary for heterochromatin formation and maintenance disrupt the CE and/or the suppression of heterochromatic crossovers to even greater extents than observed in our SC and meiotic recombination mutants.

To this end, we wished to look at a some of the suppressor of variegation mutants that were reported to have elevated centromere-proximal crossovers (Westphal and Reuter 2002). Of the genes in that study, Su(var)3–7 and Su(var)3–9 were of the most interest to us, as they encode critical heterochromatin-associated proteins. Su(var)3–9 codes for the H3K9 methyltransferase responsible for methylating pericentromeric heterochromatin, and SU(VAR)3–7 functions as an HP1 companion (Cléard et al. 1997; Delattre et al. 2000) and potential anchor for the HP1 and SU(VAR)3–9 complex (Westphal and Reuter 2002).

We hypothesized that the elevation of pericentromeric crossovers observed on chromosome 3 in the Su(var)3–7 heterozygote and the Su(var)3–7 Su(var)3–9 double heterozygote in (Westphal and Reuter 2002) would hold true on chromosome 2, and that the excess centromere-proximal crossovers in these mutants would map to the heterochromatic regions of the pericentromere. We assayed flies with a heteroallelic Su(var)3–9 genotype previously observed to have elevated DSBs in female meiotic cells (Peng and Karpen 2009). We hypothesized that this elevation would lead to an increase in centromere-proximal crossovers and a subsequent weakening of the centromere effect.

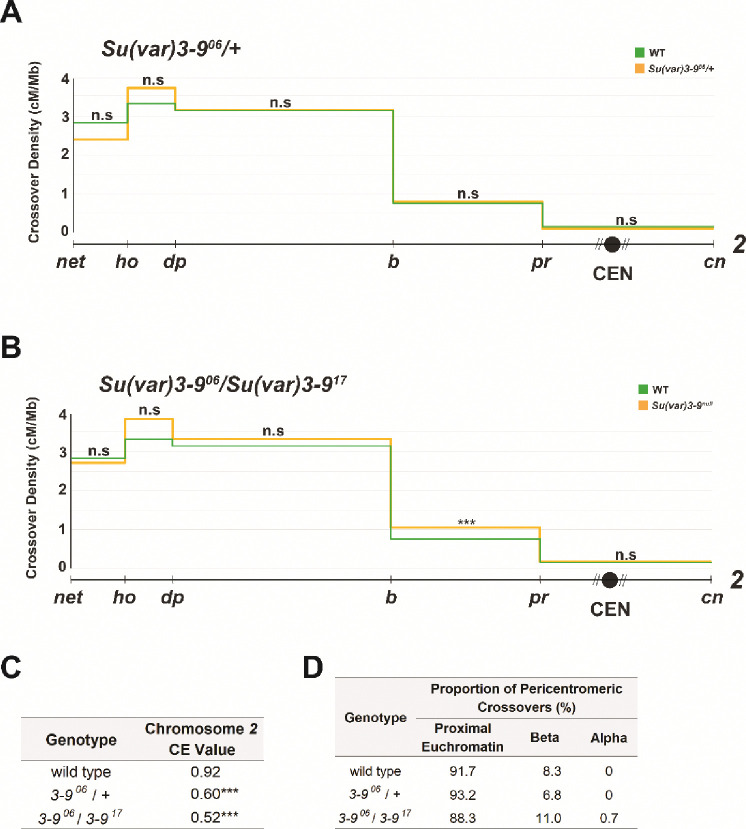

When crossover distribution was measured along chromosome 2 in Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 females, we found in increase in genetic length in the region being studied, from 48.05 cM in wild-type females to 52.8 cM in the mutant (p=0.0041); however, this elevation in genetic length comes from an increase in distal, euchromatic crossovers that lie outside of the purview of SU(VAR)3–9’s H3K9 methylation functions. Furthermore, crossover frequencies within the interval containing the centromere were not different from wild-type levels, and no change in crossover density was observed (Figure 4A). The chromosome 2 CE value in this mutant (0.91) was also unchanged from the WT chromosome 2 CE value (0.92) (Figure 4C), further indicating that the centromere effect remains intact. This is despite the reported elevation in DSBs in meiotic cells in this mutant (Peng and Karpen 2009). This suggests that crossover homeostasis is intact in this mutant, consistent with meiotic cells employing multiple levels of control to ensure crossover suppression around the centromere.

Figure 4.

(A) Crossovers in Su(var)3–906/+ (n = 10,154) and wild-type (n = 4,331) flies along chromosome 2 with the Y axis indicating crossover density in cM/Mb and the X axis indicating physical distances between recessive marker alleles that were used for recombination mapping. The chromosome 2 centromere is indicated by a black circle, unassembled pericentromeric DNA by diagonal lines. B. Crossovers in Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 (n = 8,123) and wild-type (n = 4,331) flies. C. CE values on chromosome 2 in WT, Su(var)3–906/+, and Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 flies. D. Percentages of pericentromeric crossovers that occurred within each region of the pericentromere in wild-type, Su(var)3–906/+, and Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 flies. For all panels, a 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to calculate statistical significance between mutant and wild-type numbers of total crossovers versus non-recombinants in each interval. n.s p > 0.01, *p < 0.01, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002 after correction for multiple comparisons. Supplementary Table S1 contains complete datasets. Supplementary Figure S1 contains gel images of allele-specific PCRs for each SNP defining the boundaries of pericentromeric regions.

We also measured crossover distribution along chromosome 2 in a Su(var)3–906/+ heterozygote (Figure 4B) and observed no changes from wild type in total genetic length (47.97 cM) or in crossover density in the centromeric interval. The Su(var)3–906 heterozygote had a CE value of 0.93 (Figure 4C), not significantly different from the wild-type CE value of 0.92 (p=0.2050), indicating that the centromere effect remains robust in this mutant.

Collectively, these results demonstrate that the H3K9 methyltransferase necessary for heterochromatinization of pericentromeres is dispensable both for the formation of crossovers and for suppression of crossovers in pericentromeric regions. Crossover homeostasis and CE machinery are reliably able to function in these mutants to guarantee that crossovers form at the correct frequencies and in the right chromosomal regions.

Su(var)3–9 is dispensable for suppressing crossovers in heterochromatin

Although no changes were observed in the strength of the CE in Su(var)3–9 mutants, it is still possible that crossover distribution within the pericentromeric interval is affected. Peng & Karpen (2009) reported in 2009 that many of the excess DSBs they observed in meiotic cells of Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 mutants co-localized with signals from fluorescent in situ hybridization of probes to satellite DNA sequences, something never seen in wild-type flies. This suggests that there may be a redistribution of crossovers within the pericentromeric interval towards alpha-heterochromatic regions. However, when we measured crossover frequencies in the Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 mutant in each of the pericentromeric regions (as a percent of total crossovers across the chromosomal region being studied) we found that they closely resembled WT levels (Table 1), with ~3% of total crossovers on chromosome 2 forming in proximal euchromatin and ~0.4% forming in beta heterochromatin. These are not significant changes from wild-type percentages (p=0.4406 and 0.3363, respectively).

We also calculated crossover frequencies within each pericentromeric region as a percent of total crossovers within the pericentromere, and once again observed no significant changes from wild-type frequencies, with 88% of pericentromeric crossovers mapping to proximal euchromatin (p=0.8614 compared to wild type) and 11% to beta heterochromatin (p = 0.5486) (Figure 4D). However, we did observe one crossover between the most proximal SNPs, which we never saw in our dataset from wild-type females.

We also looked at pericentromeric crossover distributions in the Su(var)3–9 heterozygote tested by Westphal and Reuter (2002) (Westphal and Reuter 2002), but saw no significant changes in total or pericentromeric crossover frequencies in proximal euchromatin, beta heterochromatin, or alpha heterochromatin. Similar to wild-type flies, 2.2% of total crossovers in this mutant were in proximal euchromatin, 0.2% were in beta heterochromatin, and 0% were in alpha heterochromatin (Table 1). Percentages of total pericentromeric crossovers also closely resembled wild-type percentages, with 93.2% occurring in proximal euchromatin and 6.8% occurring in beta heterochromatin (Figure 4D).

Overall, the lack of any significant redistribution of crossovers within the pericentromere tells us that meiosis successfully able to suppress pericentromeric crossovers in Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 mutants. Peng & Karpen (2007) showed that this mutant has reduced H3K9 methylation at repetitive regions of the genome, suggesting that H3K9 methylation – a hallmark of heterochromatinization – within the pericentromere is surprisingly dispensable for crossover suppression in beta heterochromatin and for keeping pericentric crossovers within proximal euchromatin. It also appears to be largely or completely dispensable for crossover suppression in alpha heterochromatin. Despite allowing for more heterochromatic DSBs during meiosis, the Su(var)3–9 mutant can maintain wild-type distributions of crossovers within the Drosophila pericentromere, completely unlike the SC and meiotic recombination mutants in our study.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that the centromere effect manifests differently in different regions of the pericentromere, with alpha heterochromatin displaying no crossovers and beta heterochromatin and proximal euchromatin displaying crossover suppression that diminishes with increasing distance from the centromere (Hartmann et al. 2019b; Fernandes et al. 2024). This suggests that the CE may be established via distinct mechanisms in different pericentromeric regions, motivating us to look at patterns of centromere-proximal crossover formation in three classes of mutants. These mutants affect either SC maintenance (Billmyre et al. 2019), meiotic recombination (Baker and Carpenter 1972; Hartmann et al. 2019a), or heterochromatin formation (Schotta et al. 2002), and were utilized to ask whether each of these processes exerts control over crossover suppression in independent regions of the pericentromere.

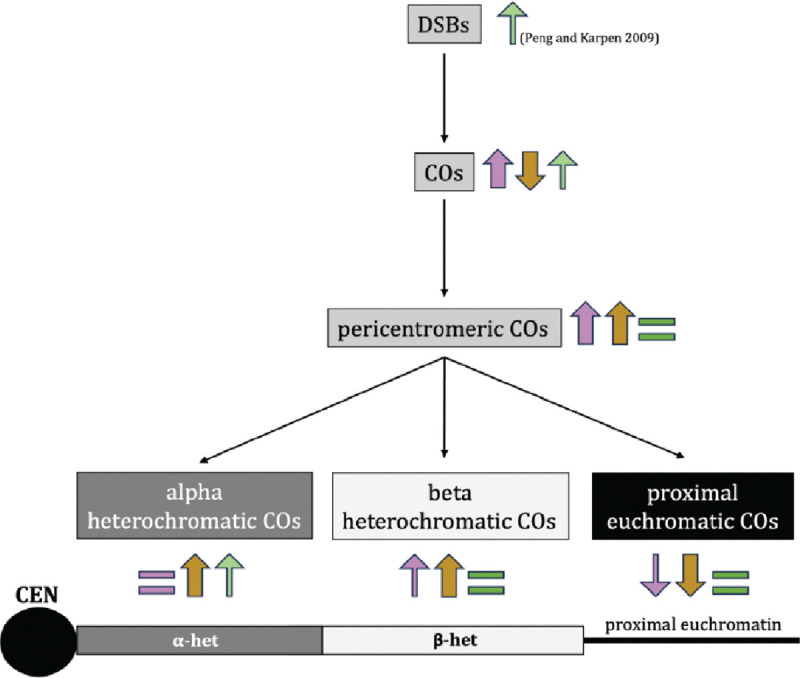

Our data show that crossover regulation at the pericentromere is indeed multi-faceted, with each class of mutants exhibiting distinct patterns of crossover formation in the various pericentromeric regions, summarized in Figure 5. We discuss the mechanistic implications of these results below.

Figure 5.

Summary of the effects of each mutant in this study on the formation of DSBs, crossovers, pericentromeric crossovers, alpha-heterochromatic crossovers, beta-heterochromatic crossovers, and proximal euchromatic crossovers. The arrows indicate whether there is an increase or decrease in the indicated event, with colors denoting the mutant in question. Purple is c(3)GccΔ2, dark yellow is mei-218null and recnull combined, green is Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917. Thickness of the arrows and intensity of color indicate strength of the increase/decrease. A schematic of a telocentric chromosome is shown below, with the centromere, alpha heterochromatin, beta- heterochromatin, and proximal euchromatin indicated.

Synaptonemal complex and the centromere effect

The SC is a meiotic structure essential for recombination in Drosophila, likely through facilitating the movement of meiotic recombination factors - such as the mei-MCM complex – along chromosomes. It provides a framework of sorts for the process of crossing-over and has been shown to contribute towards crossover patterning in various ways (Sym and Roeder 1994; Wang et al. 2015; Billmyre et al. 2019; Zhang et al. 2021). We sought to ask how disrupting it would affect pericentromeric crossover suppression and distribution.

The SC mutant in our study is an in-frame deletion of the SC gene c(3), which encodes the transverse filament of the Drosophila SC and is essential for SC assembly as well as meiotic recombination (Page and Hawley 2001). The allele we used – c(3)GccΔ2 – has defects in SC maintenance and fails to retain its full length structure by mid-pachytene (Billmyre et al. 2019). This mutant was also shown to exhibit increased centromere-proximal crossovers on chromosome 3, making it an ideal candidate to test how the SC contributes to the CE as well as to suppressing crossovers in different regions of the pericentromere.

Our data show the c(3)G mutant having a significantly weaker CE (Figure 2A, 2B) as well as a pericentromeric crossover redistribution phenotype that is intermediate between our meiotic recombination mutants and wild-type flies. While a significant increase in percentage of total crossovers is observed in both proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin in c(3)GccΔ2 flies, no change is observed in alpha-heterochromatic crossover frequencies when compared to wild type (Table 1). Additionally, the increases observed in proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin in the SC mutant do not reach the levels observed in either meiotic mutant (Table 1, Figure 2C, Figure 3C), indicating that while full length SC during mid-pachytene is necessary for centromere-proximal crossover suppression and to maintain wild-type proportions of crossovers within proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin, it doesn’t appear to be as crucial as the meiotic-MCM genes.

This is surprising as it tells us that despite c(3)GccΔ2 mutants having an ablated CE, meiotic cells in this mutant are still able to regulate crossover formation within the pericentromere and prevent the spread of excess centromere-proximal crossovers into alpha heterochromatin, and even into beta heterochromatin at the levels allowed in mei-218 and rec mutants. Like Blm, C(3)G appears to be necessary to maintain the distance-dependent CE observed in beta heterochromatin and proximal euchromatin, but dispensable for the complete suppression observed in alpha heterochromatin. These data suggest that it is possible to disrupt the CE in different ways – using different classes of mutants – that may allow an increase in crossovers within one region of the pericentromere but not another, or even different levels of crossover increases within the same region.

Our observations also fit well with the SC serving as a conduit for the recombination proteins that designate and pattern crossovers during prophase I (Rog et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2021; Fozard et al. 2023; Von Diezmann et al. 2024). Without any SC, as in the case of c(3)G null mutants, flies are completely unable to make meiotic crossovers (Page and Hawley 2001). This could be because meiotic proteins now lack a phase through which to travel along the length of paired homologs. In the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant, however, crossovers still form – at rates even higher than in wild type – but the CE is drastically weakened, which suggests that meiotic proteins can diffuse enough to designate crossovers along the chromosome, but somehow lose the ability to suppress them at the pericentromere. One explanation for this could be that centromere-proximal crossover suppression might be enforced after initial crossover designation. The c(3)GccΔ2 mutant has full length SC in early and early/mid-pachytene, but this is lost by mid-pachytene. It is possible that initial crossover designation occurs in early-pachytene, but the CE is established in mid-pachytene, and therefore severely disrupted in this mutant. Crossover distribution patterns being altered in c(3)GccΔ2 flies could also be related to timing, as it is possible that crossover suppression in alpha heterochromatin happens early, when the SC in these mutants is still fully intact, with beta-heterochromatic and proximal euchromatic crossovers being suppressed at mid-pachytene or later, when full length SC is lost in the mutant. Measuring the strength of the CE as well as pericentromeric crossover patterns in the other deletion mutants described in (Billmyre et al. 2019) that lose full length SC at different times during pachytene could shed light on which ones are important for crossover suppression in the different pericentromeric regions.

An interesting point to note about the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant is that while it has a weaker than wild-type CE on chromosomes 2 and 3, the weak CE on the X chromosome appears not to be affected (Billmyre et al. 2019). Curiously, another c(3)G deletion described by Billmyre et al. (2019) – c(3)GccΔ1 – displays CE defects on all three chromosomes, suggesting that different aspects of SC function and maintenance are important for CE establishment on different chromosomes. This suggests that CE mechanism may not be uniform across the genome. Investigating how pericentromeric crossover distributions are changed in c(3)G mutants that have an ablated CE on all three chromosomes may illuminate which aspects of SC function are important across the board, and which are important only for certain chromosomes.

Recombination machinery and the CE

The recombination genes in our study – mei-218 and rec - encode two major components of the mei-MCM complex, a pro-crossover protein complex necessary for both crossover formation and patterning during meiosis (Kohl et al. 2012). As these proteins are crucial for meiotic recombination but have no SC defects (Carpenter 1979), they provide data that is easily separable from the c(3)GccΔ2 mutant, allowing us to draw conclusions about the importance of recombination machinery independently of SC-mediated influences to centromere-proximal crossover suppression.

Based on data from the SC mutant in our study, as well as Blm mutants (Hatkevich et al. 2017), we hypothesized that mei-218 and rec mutants would exhibit a similarly defective CE, with increased pericentromeric crossovers in proximal euchromatin and beta heterochromatin but no changes from the complete crossover suppression in alpha heterochromatin. While we did observe significantly weaker centromere effects in both recombination mutants, we were surprised to see a substantial increase of total crossover percentages across all three regions of the pericentromere, with a significant redistribution of crossovers away from proximal euchromatin towards both beta and alpha heterochromatin (Table 1; Figure 3D). It must be noted here that the current assembly of the Drosophila reference genome is incomplete, and that the crossovers we recover in what we call alpha heterochromatin – defined as the region between the most proximal SNPs in our study – may still be occurring within beta heterochromatin. Nevertheless, mei-218 and rec mutants having any crossovers between our most proximal SNPs is noteworthy, as none were ever observed in Blm or c(3)G mutants (Hartmann et al. 2019; Figure 3D). This suggests that the mei-MCM complex suppresses crossovers deeper into beta heterochromatin and/or alpha heterochromatin than Blm or SC. These data also indicate that these two parts of the meiotic recombination machinery may have distinct areas of control within the pericentromere. Pericentromeric crossover distributions in double mutants could shed light on whether Blm and the mei-MCM complex work in tandem to maintain the CE and are equally important to suppress crossovers in the region.

Aside from how crossover distribution in these mutants differs from the Blm and c(3)G mutant, it is also unexpected and noteworthy that Mei-218 and Rec are necessary to prevent crossovers in heterochromatin. Previous data has shown that while “recombination-defective meiotic mutants” such as mei-218 can change euchromatic crossover distribution patterns on chromosome X and, unexpectedly, 4, they do not allow for the formation of heterochromatic crossovers on either chromosome (Sandler and Szauter 1978; Carpenter and Baker 1982b). Szauter (1984) inferred that the mechanisms “that prevent crossovers in heterochromatin are distinct from those that specify the distribution of crossovers in the euchromatin” (Szauter 1984). Our chromosome 2 results appears to contradict these conclusions, showing not only that heterochromatic crossovers can be under the control of meiotic machinery in Drosophila, but also reinforcing our hypothesis that the CE is mediated differently on different chromosomes.

Heterochromatin and the centromere effect

While both facets of the meiotic machinery tested in our study – SC and recombination genes – were observed to suppress heterochromatic crossovers, we wondered whether a stronger influence on pericentromeric crossover suppression is exerted by genes essential for heterochromatin formation, given that much of the pericentromere is heterochromatic. To test this, we used mutants of Su(var)3–9, the H3K9 methyltransferase that methylates and aids in the heterochromatinization of the pericentromere. Specifically, we tested a Su(var)3–9 heterozygote - Su(var)3–906/+ - as well as a heteroallelic null mutant Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 that was previously shown to have elevated DSBs within alpha heterochromatin in meiotic cells (Peng and Karpen 2009). Hypothesizing that heterochromatic crossover suppression is primarily chromatin-based, we expected to see a significantly greater number of crossovers in both heterochromatic regions of the pericentromere in this mutant compared to wild-type and to both classes of meiotic mutants. Surprisingly, we saw no change from wild type in CE value or total crossover distribution patterns in proximal euchromatin or beta heterochromatin, suggesting that pericentromeric crossover suppression is not mediated by this H3K9 methyltransferase, despite it being a key component of pericentromeric heterochromatinization. It appears that heterochromatic crossovers are not suppressed during meiosis because they occur in heterochromatin and may be subject to steric hindrances, but by virtue of them being under control of meiotic machinery.

Interestingly, we did recover one crossover between our most proximal SNPs in the Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 mutant. We believe this could be biologically relevant, as we observe complete suppression of crossovers in this region in wild-type flies. While this one crossover may be in unassembled beta heterochromatin, it is notable that Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 do not exhibit increased crossovers in beta heterochromatin. It is possible that this crossover was mitotic in origin. Among 3393 progeny of Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 males, which do not have meiotic recombination, we recovered a single crossover, in beta heterochromatin (Supplemental Table S1). Mitotic crossovers in the male germline are extremely rare in wild-type males (McVey et al. 2007), so this may indicate a true increase in these mutants. We note that the elevated DSBs in female meiotic cells reported by Peng and Karpen (2009) may not behave like typical meiotic DSBs in terms of repair mechanisms and regulation.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that crossover control at the Drosophila pericentromere is multifaceted, and that a collaborative effort between diverse factors that include the SC, various recombination proteins, and even chromatin state may be necessary to establish or enforce the centromere effect. We show that suppression of meiotic crossovers within heterochromatin appears to be influenced less, if at all, by the chromatin state and more by the meiotic machinery. Our data, in conjunction with studies from other labs, suggests that the mechanisms behind the centromere effect may vary among chromosomes, providing fertile ground for future research on pericentromeric crossover suppression in Drosophila and other species.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks:

Flies were maintained at 25 C on a corn meal-agar medium. The Oregon-R stock used as our wild-type control was generously provided by Dr. Scott Hawley. The mei-218 mutant alleles used in this study (mei-2181 and mei-2186) are described in (Baker and Carpenter 1972; Mckim et al. 1996). The rec mutant alleles used in this study (rec1 and rec2) are described in (Grell 1978; Matsubayashi and Yamamoto 2003; Blanton et al. 2005). The y ; Su(var)3–906/TM3 Sr and y ; Su(var)3–917/TM3 Sr stocks were generously provided by Dr. Gary Karpen. The y w / y+Y ; c(3)GccΔ2/TM3, Sb; svspa-pol stock was generously provided by Dr. Katherine Billmyre. The presence of mutant alleles was verified where possible using allele-specific PCRs optimized for this purpose. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Fly crosses:

Flies that were Oregon-R and net dppd-ho dp b pr cn were isogenized, then incorporated into various mutant backgrounds. The following stocks were built for this study: y mei-2181/FM7 ; net-cn iso/CyO, mei-2186 f / FM7 ; OR+ iso/CyO, net-cn iso/CyO ; rec1 Sb/TM6B Hu Tb, OR+ iso/CyO ; kar ry606 rec2/MKRS Sb, OR+ iso/CyO ; Su(var)3–906/MKRS, Sb, net-cn iso/CyO ; Su(var)3–917/MKRS Sb, y w ; OR+ iso/CyO ; c(3)GccΔ2/MKRS, y w ; net-cn iso/CyO ; c(3)GccΔ2/TM6B.

Recombination mapping:

Meiotic crossovers were mapped on chromosome 2 by crossing females that were heterozygous for the markers net dppd-ho dp b pr and cn in the mutant background of choice to males homozygous for the same markers. Mitotic crossovers were mapped by crossing males that were heterozygous for these markers on chromosome 2 and were Su(var)3–906/+ or Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 chromosome 3 to females homozygous for the chromosome 2 markers. Males and females were both between 1 and 5 days old when mated, and each vial was flipped after seven days. Progeny were scored for all phenotypic markers and any that had a pericentromeric crossover (between pr and cn) were collected to fine-map where within the pericentromere the crossover occurred, through allele-specific PCR. Complete datasets for all recombination mapping are given in Supplementary Table S1. Wild-type crossover distributions were taken from a previous recombination mapping dataset (Pazhayam et al. 2023). Total chromosome 2 crossover numbers for wild type were estimated using the same dataset, based on total proximal crossovers collected in this study (n=132), and is indicated as “adjusted total crossovers” in Supplementary Table S1. For c(3)GccΔ2, fine-mapping of pericentromeric crossovers was done in 171 of the 478 flies with pericentromeric crossovers, requiring an adjusted total crossover number for percentages of total crossovers calculated in Table 1. This adjusted total crossover number is also indicated in Supplementary Table S1.

Recombination calculations:

Genetic length was calculated in centiMorgans (cM) as follows: (r/n) * 100, where r represents the number of recombinant flies in an interval (including single, double, and triple crossovers) and n represents total flies that were scored for that genotype. Release 6.53 of the reference genome of Drosophila was used to calculate physical length between chromosome 2 markers used for phenotypic recombination mapping. Since alpha heterochromatin sequence is not yet assembled, we estimated the length from the estimated heterochromatic sequence, 5.4 Mb for 2L and 11.0 Mb for 2R (Adams et al. 2000), minus the length of beta heterochromatin sequence in the Release 6.53 assembly (1.39 Mb for 2L, 7.6 Mb for 2R). CE values were calculated as 1-(observed crossovers/expected crossovers). Expected crossovers = total crossovers in a genotype * (physical length of proximal interval/total physical length).

SNPs defining pericentromeric regions:

Illumina sequencing was done on isogenized stocks of Oregon-R and net-cn to identify SNP differences. DNA from ~50 whole flies was extracted using the QIAGEN DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Reads were aligned to the reference genome using bowtie2 (v2.5.3) (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) and PCR and optical duplicates were marked using samtools markdup (v1.21) (Danecek et al. 2021). Variants were called using freebayes (v1.1.0) (Erik Garrisson 2012). Unique SNPs between the net-cn and OR+ chromosome 2 were identified using bcftools isec (v1.20) (Danecek et al. 2021). SNPs were validated by analyzing reads using Integrative Genomics Viewer (Robinson et al. 2011) and via PCR.

Four SNPs (called beta2L, alpha2L, alpha2R, and beta2R) were chosen to mark the boundaries between proximal euchromatin, beta heterochromatin, and alpha heterochromatin on each arm of chromosome 2. The alpha2L (position 23424573, C in net-cn, A in OR+) and alpha2R (position 639629, C in net-cn, A in OR+) SNPs chosen were the most proximal chromosome 2 SNPs in (Hartmann et al. 2019b). The beta2L (position 22036096, A in net-cn, T in OR+) and beta2R (position 5725487, C in net-cn, T in OR+) SNPs chosen were based on maximum proximity to the heterochromatin-euchromatin boundary as defined by various studies summarized in Supplemental Table S3 of (Stutzman et al. 2024).

Proximal euchromatin is defined as the region between phenotypic marker pr and the beta2L SNP on chromosome 2L and the region between the beta2R SNP and the phenotypic marker cn on chromosome 2R. Beta heterochromatin is defined as the region between the beta2L SNP and alpha2L SNP on chromosome 2L and the alpha2R SNP and beta2R SNP on chromosome 2R. Alpha heterochromatin is defined as the region between the alpha2L SNP on chromosome 2L and the alpha2R SNP on chromosome 2R.

A second beta2R SNP (position 5726083, A in net-cn, T in OR+) was chosen for the progeny of Su(var)3–906/+ and c(3)GccΔ2 mutants with pericentromeric crossovers as the allele-specific PCR amplifying the beta2R SNP at position 5725487 was no longer robust towards the end of our study. For consistency, progeny of WT, mei-218null, recnull, and Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 flies with pericentromeric crossovers where the position of the crossover was indicated by the presence or absence of the 5725487 beta2R band were re-confirmed with the allele-specific PCR amplifying the beta2R SNP at position 5726083. Additional SNPs alpha2L_II (position 23423662, A in net-cn, C in OR+) and alpha2R_II (position 637775, T in net-cn, C in OR+) were used to confirm each alpha-heterochromatic crossover that was observed. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are shown in Supplementary Table S3. Optimization PCRs for each SNP are shown in Supplementary Figure S2.

Allele-specific PCR:

Progeny from the crosses of experimental females of the desired mutant background and males homozygous for phenotypic markers net-cn that had a pericentromeric crossover (a crossover between the most proximal markers purple and cinnabar on either arm of chromosome 2) were collected and DNA was extracted. Since the recombined chromosome from experimental females is recovered over a net-cn chromosome from males, all progeny carry the net-cn versions of each SNP. Therefore, allele-specific PCRs that amplify the OR+ versions had to be performed on progeny with a pericentromeric crossover to map whether the crossover occurred in proximal euchromatin, beta heterochromatin, or alpha heterochromatin. For each allele-specific PCR, the presence of a band indicates that the recombined chromosome from the experimental female has the OR+ version of the SNP. The absence of a band indicates that the recombined chromosome from the experimental female has the net-cn version of the SNP. With this information, we pinpointed the switch from OR+ SNPs to net-cn SNPs on the recombined chromosome, telling us where the pericentromeric crossover in the experimental female occurred. Gels from all allele-specific PCRs for each fly of every genotype (WT, mei-218null, recnull, and Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917, Su(var)3–906/+ and c(3)GccΔ2) are shown in Supplementary Figure S1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katie Billmyre and Gary Karpen for generously sharing Drosophila stocks, Carolyn Turcotte for help processing Illumina sequences/SNP calling, and Greg Copenhaver, Kacy Gordon, Dale Ramsden, Dan McKay, as well as members of the Sekelsky lab for helpful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to JS under award 1R35GM118127. NP was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging under award 1F31AG079626 and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under award T32GM135128.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Figure S1. Gel images for allele-specific PCRs used to amplify the OR+ version of each SNP that defines the various pericentromeric regions in WT as well as each mutant in this study. Numbers indicate each fly with a pericentromeric crossover that was analyzed. O indicates OR+ flies (positive control) and N indicates net-cn flies (negative control).

Figure S2. Gel images for optimization PCRs performed to decide on the conditions for allele-specific PCRs that were used to amplify the OR+ version of each SNP that defines the various pericentromeric regions in this study. Temperature gradients from 56C to 66C are indicated on each gel. A black box is drawn around the band that should be amplified in OR+ (O) flies and not in net-cn (N) flies.

Table S1. The complete meiotic crossover distribution dataset on chromosome 2 between markers net and cinnabar for wild type and each mutant in this study. Mitotic crossover distribution datasets between the same chromosome 2 markers for Su(var)3–906/+ and Su(var)3–906/Su(var)3–917 flies are also shown. SCO, DCO, and TCO denote single, double, and triple crossover progeny, respectively.

Table S2. Primer sequences used to validate various mutant alleles.

Table S3. Primer sequences and PCR conditions for allele-specific PCRs used to amplify the OR+ version of each SNP that defines the various pericentromeric regions in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Drosophila stocks are available upon request. The authors confirm that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions of the article are present within the article, figures, table, and supplemental information. Illumina sequences for isogenized OR+ and net-cn flies have been submitted to SRA under BioProject PRJNA1198609.

References

- Adams M.D. et al. , 2000. The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science 287: 2185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. S., and Carpenter A. T., 1972. Genetic analysis of sex chromosomal meiotic mutants in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 71: 255–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle G. W., 1932. A possible influence of the spindle fibre on crossing-over in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 18: 160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billmyre K. K., Cahoon C. K., Heenan G. M., Wesley E. R., Yu Z. et al. , 2019. X chromosome and autosomal recombination are differentially sensitive to disruptions in SC maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116: 21641–21650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanton H. L., Radford S. J., McMahan S., Kearney H. M., Ibrahim J. G. et al. , 2005. REC, Drosophila MCM8, drives formation of meiotic crossovers. PLoS Genet 1: e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand C. L., Cattani M. V., Kingan S. B., Landeen E. L. and Presgraves D. C., 2018. Molecular evolution at a meiosis dene mediates species differences in the rate and patterning of recombination. Current Biology 28: 1289–1295.e1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T., and Baker B. S., 1982a. On the control of the distribution of meiotic exchange in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 101: 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T., and Baker B. S., 1982b. On the control of the distribution of meiotic exchange in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 101: 81–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T. C., 1975. Electron microscopy of meiosis in Drosophila melanogaster females: II: The recombination nodule—a recombination-associated structure at pachytene? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 72: 3186–3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter A. T. C., 1979. Recombination nodules and synaptonemal complex in recombination-defective females of Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma 75: 259–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cléard F., Delattre M. and Spierer P., 1997. SU(VAR)3–7, a Drosophila heterochromatin-associated protein and companion of HP1 in the genomic silencing of position-effect variegation. Embo j 16: 5280–5288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K. A., Unruh J. R., Slaughter B. D., Yu Z., Lake C. M. et al. , 2014. Corolla is a novel protein that contributes to the architecture of the synaptonemal complex of Drosophila. Genetics 198: 219–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver G. P., Nickel K., Kuromori T., Benito M. I., Kaul S. et al. , 1999. Genetic definition and sequence analysis of Arabidopsis centromeres. Science 286: 2468–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P., Bonfield J. K., Liddle J., Marshall J., Ohan V. et al. , 2021. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delattre M., Spierer A., Tonka C. H. and Spierer P., 2000. The genomic silencing of position-effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster: interaction between the heterochromatin-associated proteins Su(var)3–7 and HP1. J Cell Sci 113 Pt 23: 4253–4261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erik Garrisson G. M., 2012. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv:1207.3907 [q-bio.GN]. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J. B., Naish M., Lian Q., Burns R., Tock A. J. et al. , 2023. Structural variation and DNA methylation shape the centromere-proximal meiotic crossover landscape in Arabidopsis. bioRxiv: 2023.2006.2012.544545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes J. B., Naish M., Lian Q., Burns R., Tock A. J. et al. , 2024. Structural variation and DNA methylation shape the centromere-proximal meiotic crossover landscape in Arabidopsis. Genome Biol 25: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozard J. A., Morgan C. and Howard M., 2023. Coarsening dynamics can explain meiotic crossover patterning in both the presence and absence of the synaptonemal complex. eLife 12: e79408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall J. G., Cohen E. H. and Polan M. L., 1971. Repetitive DNA sequences in Drosophila. Chromosoma 33: 319–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari R., Cannon E. K., Kanizay L. B., Lawrence C. J. and Dawe R. K., 2013. Maize chromosomal knobs are located in gene-dense areas and suppress local recombination. Chromosoma 122: 67–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire P., Motamedi M. and Joh R., 2024. Mathematical model for the role of multiple pericentromeric repeats on heterochromatin assembly. PLoS Comput Biol 20: e1012027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grell R. F., 1978. Time of recombination in the Drosophila melanogaster oocyte: evidence from a temperature-sensitive recombination-deficient mutant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 75: 3351–3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M., Kohl K. P., Sekelsky J. and Hatkevich T., 2019a. Meiotic MCM proteins promote and inhibit crossovers during meiotic recombination. Genetics 212: 461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M., Umbanhowar J. and Sekelsky J., 2019b. Centromere-proximal meiotic crossovers in drosophila melanogaster are suppressed by both highly repetitive heterochromatin and proximity to the centromere. Genetics 213: 113–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatkevich T., Kohl K. P., McMahan S., Hartmann M. A., Williams A. M. et al. , 2017. Bloom syndrome helicase promotes meiotic crossover patterning and homolog disjunction. Current Biology : CB 27: 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins R. A., Carlson J. W., Wan K. H., Park S., Mendez I. et al. , 2015. The Release 6 reference sequence of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res 25: 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John B. a. M. K., 1985. The inter-relationship between heterochromatin distribution and chiasma distribution. Genetica 66: 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler K. E., Hawley R. S., Sherman S. and Hassold T., 1996. Recombination and nondisjunction in humans and flies. Human Molecular Genetics 5: 1495–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl K. P., Jones C. D. and Sekelsky J., 2012. Evolution of an MCM complex in flies that promotes meiotic crossovers by blocking BLM helicase. Science 338: 1363–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake C. M., and Hawley R. S., 2012. The molecular control of meiotic chromosomal behavior: events in early meiotic prophase in Drosophila oocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 74: 425–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb N. E., Freeman S. B., Savage-Austin A., Pettay D., Taft L. et al. , 1996. Susceptible chiasmate configurations of chromosome 21 predispose to non–disjunction in both maternal meiosis I and meiosis II. Nature Genetics 14: 400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., and Salzberg S. L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libuda D. E., Uzawa S., Meyer B. J. and Villeneuve A. M., 2013. Meiotic chromosome structures constrain and respond to designation of crossover sites. Nature 502: 703–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtani M. M., and Willard H. F., 1998. Physical and genetic mapping of the human X chromosome centromere: repression of recombination. Genome Res 8: 100–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini E., Diaz R. L., Hunter N. and Keeney S., 2006. Crossover homeostasis in yeast meiosis. Cell 126: 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather K., 1939. Crossing over and heterochromatin in the X chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 24: 413–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubayashi H., and Yamamoto M. T., 2003. REC, a new member of the MCM-related protein family, is required for meiotic recombination in Drosophila. Genes Genet Syst 78: 363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKim K. S., Dahmus J. B. and Hawley R. S., 1996. Cloning of the Drosophila melanogaster meiotic recombination gene mei-218: A genetic and molecular analysis of interval 15E. Genetics 144: 215–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra S., and Mckim K. S., 2006. Temporal Analysis of meiotic DNA double-strand break formation and repair in Drosophila females. PLoS Genetics 2: e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklos G. L., and Cotsell J. N., 1990. Chromosome structure at interfaces between major chromatin types: alpha- and beta heterochromatin. Bioessays 12: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C., Fozard J. A., Hartley M., Henderson I. R., Bomblies K. et al. , 2021. Diffusion-mediated HEI10 coarsening can explain meiotic crossover positioning in Arabidopsis. Nature Communications 12: 4674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar M., and Smith G. R., 2016. Repression of harmful meiotic recombination in centromeric regions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 54: 188–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar M., and Smith G. R., 2018. Pericentromere-specific cohesin complex prevents meiotic pericentric dna double-strand breaks and lethal crossovers. Mol Cell 71: 540–553.e544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver T. R., Tinker S. W., Allen E. G., Hollis N., Locke A. E. et al. , 2012. Altered patterns of multiple recombinant events are associated with nondisjunction of chromosome 21. Human Genetics 131: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen A. R. G., 1950. The Theory of Genetical Recombination, pp. 117–157 in Advances in Genetics, edited by Demerec M.. Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. L., and Hawley R. S., 2001. c(3)G encodes a Drosophila synaptonemal complex protein. Genes Dev 15: 3130–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazhayam N. M., Frazier L. K. and Sekelsky J., 2024. Centromere-proximal suppression of meiotic crossovers in drosophila is robust to changes in centromere number and repetitive dna content. Genetics 226:iyad216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazhayam N. M., Turcotte C. A. and Sekelsky J., 2021. Meiotic Crossover Patterning. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. C., and Karpen G. H., 2007. H3K9 methylation and RNA interference regulate nucleolar organization and repeated DNA stability. Nat Cell Biol 9: 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J. C., and Karpen G. H., 2009. Heterochromatic genome stability requires regulators of histone H3 K9 methylation. PLoS Genet 5: e1000435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T., Thorvaldsdóttir H., Winckler W., Guttman M., Lander E. S. et al. , 2011. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29: 24–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rog O., Köhler S S., and Dernburg A.F. (2017) The synaptonemal complex has liquid crystalline properties and spatially regulates meiotic recombination factors. Elife 6:e21455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler L., and Szauter P., 1978. The effect of recombination-defective meiotic mutants on fourth-chromosome crossing over in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 90: 699–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotta G., Ebert A., Krauss V., Fischer A., Hoffmann J. et al. , 2002. Central role of Drosophila SU(VAR)3–9 in histone H3-K9 methylation and heterochromatic gene silencing. Embo j 21: 1121–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon L., Voisin M., Tatout C. and Probst A. V., 2015. Structure and function of centromeric and pericentromeric heterochromatin in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front Plant Sci 6: 1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatis H. M., 1955. A Reconsideration of the brown-dominant position effect. Genetics 40: 246–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storlazzi A., Xu L., Schwacha A. and Kleckner N., 1996. Synaptonemal complex (SC) component Zip1 plays a role in meiotic recombination independent of SC polymerization along the chromosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93: 9043–9048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant A. H., 1913. The linear arrangement of six sex-linked factors in Drosophila, as shown by their mode of association. Journal of Experimental Zoology 14: 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stutzman A. V., Hill C. A., Armstrong R. L., Gohil R., Duronio R. J. et al. , 2024. Heterochromatic 3D genome organization is directed by HP1a- and H3K9-dependent and independent mechanisms. Mol Cell 84: 2017–2035.e2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym M., and Roeder G. S., 1994. Crossover interference is abolished in the absence of a synaptonemal complex protein. Cell 79: 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szauter P., 1984. An analysis of regional constraints on exchange in Drosophila melanogaster using recombination-defective meiotic mutants. Genetics 106: 45–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenten N., Kuhl L.-M., Lam I., Oke A., Kerr A. R. et al. , 2015. The kinetochore prevents centromere-proximal crossover recombination during meiosis. eLife 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]