Abstract

Abstract

Exercise is a potent stimulus for combatting skeletal muscle ageing. To study the effects of exercise on muscle in a preclinical setting, we developed a combined endurance–resistance training stimulus for mice called progressive weighted wheel running (PoWeR). PoWeR improves molecular, biochemical, cellular and functional characteristics of skeletal muscle and promotes aspects of partial epigenetic reprogramming when performed late in life (22–24 months of age). In this investigation, we leveraged pan‐mammalian DNA methylome arrays and tandem mass‐spectrometry proteomics in skeletal muscle to provide detailed information on late‐life PoWeR adaptations in female mice relative to age‐matched sedentary controls (n = 7–10 per group). Differential CpG methylation at conserved promoter sites was related to transcriptional regulation genes as well as Nr4a3, Hes1 and Hox genes after PoWeR. Using a holistic method of ‐omics integration called binding and expression target analysis (BETA), methylome changes were associated with upregulated proteins related to global and mitochondrial translation after PoWeR (P = 0.03). Specifically, BETA implicated methylation control of ribosomal, mitoribosomal, and mitochondrial complex I protein abundance after training. DNA methylation may also influence LACTB, MIB1 and UBR4 protein induction with exercise – all are mechanistically linked to muscle health. Computational cistrome analysis predicted several transcription factors including MYC as regulators of the exercise trained methylome–proteome landscape, corroborating prior late‐life PoWeR transcriptome data. Correlating the proteome to muscle mass and fatigue resistance revealed positive relationships with VPS13A and NPL levels, respectively. Our findings expose differential epigenetic and proteomic adaptations associated with translational regulation after PoWeR that could influence skeletal muscle mass and function in aged mice.

Key points

Late‐life combined endurance–resistance exercise training from 22–24 months of age in mice is shown to improve molecular, biochemical, cellular and in vivo functional characteristics of skeletal muscle and promote aspects of partial epigenetic reprogramming and epigenetic age mitigation.

Integration of DNA CpG 36k methylation arrays using conserved sites (which also contain methylation ageing clock sites) with exploratory proteomics in skeletal muscle extends our prior work and reveals coordinated and widespread regulation of ribosomal, translation initiation, mitochondrial ribosomal (mitoribosomal) and complex I proteins after combined voluntary exercise training in a sizeable cohort of female mice (n = 7–10 per group and analysis).

Multi‐omics integration predicted epigenetic regulation of serine β‐lactamase‐like protein (LACTB – linked to tumour resistance in muscle), mind bomb 1 (MIB1 – linked to satellite cell and type 2 fibre maintenance) and ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component N‐recognin 4 (UBR4 – linked to muscle protein quality control) after training.

Computational cistrome analysis identified MYC as a regulator of the late‐life training proteome, in agreement with prior transcriptional analyses.

Vacuolar protein sorting 13 homolog A (VPS13A) was positively correlated to muscle mass, and the glycoprotein/glycolipid associated sialylation enzyme N‐acetylneuraminate pyruvate lyase (NPL) was associated to in vivo muscle fatigue resistance.

Keywords: ageing, BETA, DNA methylation, mitoribosome, proteomics

Abstract figure legend Omics integration is a powerful tool for understanding determinants of adaptation. Recent efforts infer epigenetic regulation of the proteome via integrated multiome analysis that can inform the identification of therapeutic targets. We performed DNA methylomics and proteomics in skeletal muscle to gain a deeper understanding of the beneficial effects of late‐life exercise adaptation using progressive weighted wheel running – PoWeR. Integrated ‐omics predicted epigenetic regulation of the protein landscape in skeletal muscle with exercise. Translation, mitoribosomal and mitochondrial complex I proteins were regulated as well as LACTB, MIB1 and UBR4 – the latter are mechanistically linked to several aspects of muscle health. MYC was implicated as a transcriptional activator of the training‐induced proteome. Correlating the proteome to muscle mass and function suggested roles for VPS13A and NPL in muscle phenotype. These data are a resource for understanding potential contributors to the beneficial effects of exercise in skeletal muscle with ageing. Created using BioRender.com.

Introduction

Physical exercise is an effective strategy to reduce the loss of muscle mass and function that inevitably accompanies human ageing (Cartee et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2023). A training approach that combines resistance and endurance exercise modalities can promote metabolic health and skeletal muscle mass, strength and power production (Murach & Bagley, 2016; Schumann et al., 2022). This type of training is also consistent with the recommendations of the American College of Sports Medicine for general health and wellness (Liguori, 2020). The loss of each muscle health dimension is independently associated with increased all‐cause mortality as well as lower quality of life and decreased ‘healthspan’ (García‐Hermoso et al., 2018; Kokkinos et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2011; Metter et al., 2002; Reid & Fielding, 2012; Sui et al., 2007; Trombetti et al., 2016). Despite its effectiveness, exercise is often overlooked as a key aspect of a healthy lifestyle in favour of dietary, pharmacological and/or biological therapeutics (DeVito et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). These approaches may not achieve the same level of effectiveness as exercise, nor work synergistically or additively with exercise (Elliehausen et al., 2023; Furrer & Handschin, 2023; Konopka et al., 2019; Walton et al., 2019). For instance, in healthy humans, consuming the repurposed ‘anti‐ageing’ drug metformin has a deleterious effect on endurance and resistance exercise adaptation in skeletal muscle (Konopka et al., 2019; Walton et al., 2019).

There is a >20 year history of using ‐omics to understand skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise, particularly hypertrophic and strengthening exercise, in ageing humans (Jozsi et al., 2000; Murach & Peterson, 2023; Pillon et al., 2020; Roth et al., 2002). To complement human ageing and exercise studies, we recently developed a murine training method called progressive weighted wheel running, or PoWeR (Dungan et al., 2019; Murach, McCarthy, et al., 2020; Murach, Mobley, et al., 2020). PoWeR is a high‐volume voluntary approach that involves both endurance and resistance exercise stimuli. In concert with ‐omics, PoWeR can help identify cellular and molecular factors mediating the powerful beneficial effects of combined exercise in skeletal muscle at different times throughout the lifespan. In young mice (4–6 months old), 2 months of PoWeR elicits an ‘athlete’ phenotype characterized by larger and more functional cardiac muscle and hypertrophied hindlimb skeletal muscles with a slower‐twitch fibre type profile and fewer hybrid fibres relative to untrained animals (Dungan et al., 2019; Murach, Mobley, et al., 2020). PoWeR also elicits molecular changes in skeletal muscle that include an altered DNA methylome specifically in myonuclei that relates to gene expression in the trained state (Murach, Dungan, et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2021). We utilized a PoWeR approach adapted for aged mice to determine the extent to which late‐life exercise attenuates aspects of skeletal muscle ageing (Dungan et al., 2022; Murach, Dimet‐Wiley, et al., 2022). Despite lower training volume and less weight on the wheel than young mice (Dungan et al., 2019; Murach, Mobley, et al., 2020), 8 weeks of late‐life PoWeR had a positive effect on muscle mass, in vivo contractile function, fibre type composition, the gene expression landscape and the myonuclear DNA methylome (Dungan et al., 2022). Late‐life PoWeR also altered epigenetic patterns in murine skeletal muscle consistent with a lower DNA methylation age (Jones et al., 2023; Murach, Dimet‐Wiley, et al., 2022). The molecular profile of muscle after PoWeR shares features with epigenetic partial reprogramming mediated by Yamanaka factors, specifically MYC (Jones et al., 2023, 2024).

Adapting a data integration technique called binding and expression target analysis (BETA) (Wang et al., 2013), we recently found that myonuclear DNA methylation predicted myonuclear transcriptional changes and the functional metabolic response to rapid loading‐induced skeletal muscle adaptation (Ismaeel et al., 2024). Several studies have connected the methylome to the proteome in the contexts of cancer (Magzoub et al., 2019), the brain (Gadd et al., 2022; Muhie et al., 2023), skeletal muscle (Maehara et al., 2023), and in muscle with exercise (Landen et al., 2023). Furthermore, proteomic profiling provides a unique lens for understanding ageing processes since protein alterations throughout the lifespan can often occur without changes to mRNA levels (Llewelyn et al., 2024; Takemon et al., 2021). This decoupling could be a symptom of age‐related alterations to mRNA stability (Brewer, 2002; Ma et al., 2012; Min et al., 2018; Pioli et al., 1998) and/or ribosomal stoichiometry (Hinz et al., 2021; Kelmer Sacramento et al., 2020), leading to altered protein homeostasis (i.e. proteostasis) – a hallmark of ageing (López‐Otín et al., 2013). We therefore sought to determine how the skeletal muscle epigenetic effects produced by late‐life PoWeR might relate to the muscle proteome.

In this investigation, we used pan‐mammalian methylation arrays targeted at ∼36k CpGs conserved from mice to humans (Arneson et al., 2022) – which also contain methylation ageing clock sites we leveraged previously (Jones et al. 2023) – combined with tandem mass spectrometry proteomics in a large cohort of aged female sedentary (SED) and late‐life PoWeR mice (n = 7–10 for each group and molecular analysis using the same muscle for methylome and proteome analysis). By integrating the methylome and proteome with BETA, we infer coordinated regulation of ribosomal, translation initiation factor, mitochondrial ribosomal (mitoribosomal), and mitochondrial complex I proteins with PoWeR late in life. We also identified several proteins implicated in muscle health that were influenced by late‐life exercise at the epigenetic and protein levels. We used these data to computationally deduce major transcriptional regulators of adaptation. An exploratory comparison to previously published weighted wheel running proteomic data from muscle of young mice (Leuchtmann et al., 2023) provides preliminary insight on protein responses to training across the murine lifespan. Finally, we related our proteomics data to muscle mass and in vivo muscle function to (1) identify correlates of skeletal muscle health at the protein level and (2) provide a hypothesis‐generating resource for the skeletal muscle community. Collectively, we present rich datasets for epigenetic and protein targets related to improved skeletal muscle health with ageing by using a combined exercise training approach and ‐omics integration.

Methods

Ethical approval

Animal procedures were performed according to all national and local guidelines and regulations, the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the ARRIVE guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020), and the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 2019‐3301) at the University of Kentucky.

Animals and animal procedures

Mice were housed in a temperature‐ and humidity‐controlled room, maintained on 12:12‐h light–dark cycles, and food and water were provided ad libitum throughout experimentation. All animals were sacrificed via cervical dislocation after deep isoflurane anaesthesia. Approximately 22‐month‐old female C57BL/6N mice were obtained from the Charles River Laboratories (Hollister, CA, USA) National Institute on Aging research colony; exact ages are not recorded for this colony, but the birth month is documented. Twenty‐two months in mice is estimated to correspond to ∼73 human years (Dutta & Sengupta, 2016). Female mice were used for these experiments since they tend to consistently run a greater distance than males in our studies. These experiments were a subset of a larger study, and thus all mice were subcutaneously injected once‐daily with a 0.9% NaCl sterile saline solution (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, cat. 50‐843‐141) throughout the 8 weeks of PoWeR/remaining SED. Importantly, all of the results reported are only from the saline‐treated of the larger study. For all murine exercise training experiments, aged female mice were subjected to voluntary progressive weighted wheel running (PoWeR) as previously described by us (Dungan et al., 2022; Murach, Dimet‐Wiley, et al., 2022). Mice in the PoWeR group (n = 10) were singly housed in cages with running wheels to allow monitoring of individual running distance using ClockLab software (Actimetrics, Wilmette, IL, USA), and mice in the SED group (n = 9) were group housed in cages without running wheels. Following an introductory week with an unweighted wheel, 8 weeks of PoWeR training commenced with the following weight progression: 2 g in week 1, 3 g in week 2, 4 g in week 3, and 5 g in weeks 4–8. One‐gram magnets (product no. B661, K&J Magnetics, Pipersville, PA, USA) were affixed to one side of the wheel to allow for the progressive increase in weight. Mice were approximately 24.5 months old upon completion of the experiment. PoWeR mice ran 4.3 ± 2.9 km/day (mean ± SD), as previously reported by us (Jones et al., 2023). Following 8 weeks of PoWeR or 8 weeks as sedentary controls, muscle function was tested in the right hindlimb of mice before they were humanely euthanized in the morning by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anaesthesia after a 24‐h wheel lock and overnight fast. Hindlimb muscles were then rapidly dissected and flash‐frozen. Gastrocnemius tissue of the left hindlimb was split into two parts, one of which was used for epigenomic analyses and the other for the proteomic analyses herein.

Before euthanization at the end of week 8, right limb plantarflexor muscle complex strength was measured using an in vivo isometric peak tetanic torque technique (Englund et al., 2020) (muscles from the left limb were used for the methylomics and proteomics). The tibial nerve was stimulated, and electrode placement optimized to minimize antagonistic dorsiflexion. An ideal current was defined and maintained during a force–frequency experiment to establish peak tetanic torque. Immediately after, each mouse underwent a fatigue test of 54 submaximal contractions at 60 Hz. Each contraction's peak torque and the maximum for all contractions were computed. The number of contractions with peak torque values exceeding 50% and 70% of that maximum was defined for each mouse. Cumulative work for each animal was calculated by summing the integral of each contraction, which was corrected for baseline force. Data for fatigue resistance and total work calculations were not recorded for three SED mice and one PoWeR mouse since these mice exhibited cumulative workloads that suggested an inability to perform the task. Murine muscle characteristics are presented in Table 1, and SED vs. PoWeR were compared using Student's two‐tailed t test (P < 0.05) since data were homoscedastic and normally distributed.

Table 1.

Skeletal muscle mass and in vivo functional characteristics

| SED | PoWeR | |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrocnemius absolute mass (mg) | 74.9 ± 12.2 | 99.3 ± 8.7* |

| Gastrocnemius normalized mass (mg·g‐1) | 2.76 ± 0.53 | 3.85 ± 0.24* |

| Total work (mN·m) | 13097 ± 9068 | 22888 ± 6199 |

| Final torque during muscular fatigue testing (mN·m) | 0.65 ± 0.49 | 0.83 ± 0.30 |

| Peak torque during muscular fatigue testing (mN·m) | 1.57 ± 0.78 | 2.85 ± 0.62* |

Data presented as mean±SD. *p<0.05 vs. SED.

Epigenomics

DNA was extracted from flash‐frozen gastrocnemius tissue using a Qiagen (Germantown, MD, USA) DNA kit (cat no. 69504 or 69506) and standard protocols with elution into ultrapure, nuclease‐free milliQ water. The Clock Foundation (Torrance, CA, USA) quantified DNA and assessed its purity via 260/280 absorption ratio; extraction, quantification and purity were assessed by The Clock Foundation. Bisulfite conversion was then performed on at least 150 ng of the extracted DNA using a Zymo EZ DNA methylation kit at AKESOgen (Peachtree Corners, GA, USA). AKESOgen then used at least 150 ng of the total converted DNA and processed it further using an Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) 36k Horvath Mammalian Methylation Chip array kit (a customized Infinium HD iSelect Methyl Custom BeadChip; Arneson et al., 2022). The BeadChip was then scanned using an iScan to determine DNA methylation. Methylation arrays were subjected to quality control measures according to the protocols established by the Mammalian Methylation Consortium (Clock Foundation). SEnsible Step‐wise Analysis of Methylation data (SeSAMe) was used to derive β values for all samples, according to the script at github.com/shorvath/MammalianMethylationConsortium/Manifests and R packages/Archived.RpackagesManifests and R packages/Archived.Rpackages/sesame_1.9.7.tar.gz. The β values for the PoWeR and SED animals were used as counts and transposed into a SummarizedExperiment container alongside a dataframe describing the sample IDs and the group to which each sample belonged. We then applied the SeSAMe DML function to the SummarizedExperiment container and then used the summaryExtractTest function to extract the P‐values for differentially methylated loci. SeSAMe uses a linear model and Student's t test on the slope and Fisher's F test contrasting a full model versus reduced model to determine which loci are statistically significantly differentially methylated; results of these two tests are the same for the analyses herein since there are only two groups. SeSAMe was used in R version 4.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with SeSAMe package version 1.19.5. As a result of the exploratory nature and follow‐on proteomics validation in this study, adjustments for multiple comparisons were not made and significance was accepted at P < 0.05 for differentially methylated CpG sites (Streiner & Norman, 2011).

Proteomics

Proteomics samples were processed in two batches to accommodate the capacity of a 16‐plex tandem mass tag kit. The current work is part of a larger study that includes more samples and different treatment groups (Dimet‐Wiley et al. 2024). Samples from one batch were included in the second batch to control for any potential batch effects. Samples of flash‐frozen gastrocnemius were diced and placed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer with protease inhibitors and a 7 mm metal bead in each tube. Samples were homogenized using a Qiagen TissueLyser for 10 min at 30 Hz, then chilled for 20 min at 4°C. Samples were pelleted through centrifugation at 4°C at maximum speed (∼16,000 g) for 20 min, supernatants were collected, and their protein concentrations determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay. Supernatants were diluted to 2 mg/ml with RIPA buffer (containing protease inhibitors at the same concentrations as before). Samples were then split into aliquots for subsequent proteomic and metabolomic analyses (data not shown), and 150 ng of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen adw protein (Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA, NBP2‐35889‐20 ug) was added to each 50 µL proteome aliquot as a pre‐digestion control.

After the initial processing, SDS was added to a final concentration of 5%, with 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) used as a diluent. Dithiothreitol was added to a final concentration of 10 mM, then samples were incubated at 56°C for 30 min, cooled, and iodoacetamide was added to a final concentration of 20 mM. Samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, centrifuged for 2 min at 11,700 g, and supernatants collected. Fifty microlitres of each supernatant was digested overnight with trypsin at 37°C using an S‐Trap (ProtiFi, Fairport, NY, USA). After digestion, the peptide eluate was dried and reconstituted in 100 mM TEAB buffer. Equal amounts of peptide (20–30 µg) were taken from each sample, and 500 fmol of β‐galactosidase (SCIEX, Framingham, MA, USA) was added as a post‐digestion control and an internal standard to monitor liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) reproducibility. Each sample in a respective batch was labelled with TMTpro reagent, giving it a unique identifier, then quenched with 5% hydroxylamine; after this, the samples for a respective batch were pooled. The pooled sample was fractionated into eight fractions using a reversed‐phase fractionation spin column (Pierce/Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The fractions were dried in a SpeedVac and reconstituted in a 2% acetonitrile (ACN), 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid buffer.

Fractions were injected into an Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) coupled to an Ultimate 3000 RSLC‐Nano liquid chromatography system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were injected onto a 75 µm i.d., 75 cm‐long EasySpray column (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and eluted with a gradient from 0%–28% buffer B over 180 min. Buffer A contained 2% (v/v) ACN and 0.1% formic acid in water, and buffer B had 80% (v/v) ACN, 10% (v/v) trifluoroethanol and 0.1% formic acid in water.

The mass spectrometer operated in positive ion mode with a source voltage of 2.4 kV and an ion transfer tube temperature of 275°C. MS scans were acquired at 120,000 resolution in the Orbitrap, and top speed mode was used with a cycle time of 3 s. MS2 was performed in the Orbitrap using higher‐energy collisional dissociation (HCD) at 50,000 resolution with a collision energy of 35% for ions with charges 2–4. Dynamic exclusion was set for 25 s after an ion was selected for fragmentation.

Raw MS data files were analysed using Proteome Discoverer v2.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with peptide identification (outside of the known pre/post‐digestion controls) performed using Sequest HT searching against the mouse protein database from UniProt. Fragment and precursor tolerances of 10 ppm and 0.02 Da were specified, and three missed cleavages were allowed. Carbamidomethylation of Cys and TMTpro labelling of N‐termini and Lys side‐chains were set as a fixed modification, with oxidation of Met set as a variable modification. The false‐discovery rate (FDR) cutoff was 1% for all peptides.

All analyses for this study used reporter intensity for downstream analyses of the MS2 dataset. Pre‐ and post‐digestion controls were analysed separately and removed before downstream processing since they had been spiked in. The coefficient of variation was computed for the pre‐ and post‐digestion controls across all of the saline‐treated SED and PoWeR mice samples, as well as the aforementioned two SED samples repeated in both batches (referred to hereafter as ‘batch standards’). The pre‐digestion control, recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen adw protein, had a coefficient of variation of 59% while the post‐digestion control, β‐galactosidase, had a coefficient of variation of 26%. The MS2 raw data files were processed as follows. First, each MS2 file was aggregated across batches to include only proteins identified in both batches, and the two batch standards were averaged for each batch to create a pooled batch standard value for each protein. The pooled batch standard for the SED and PoWeR batches were each added to the dataset. Because the batch standards in the PoWeR batch were samples from SED animals, these samples were used for the computation of the pooled batched standard and then dropped from the dataset, whereas the pooled batch standard and the batched standard for the saline‐treated SED animal were retained for the sedentary samples. Proteins with a zero value in one of the batch standards were removed from the data to prevent floor effects from being applied to the normalization process and avoid reliance on averaging to just one batch standard. Additionally, proteins for which >50% of the samples in a particular cohort had a value of zero were removed since the reduced number of measurements might contribute to a reduced variance for that specific cohort and could, in turn, increase the probability of a false positive. After this initial data cleaning, there were only four instances where more than one sample was missing from a cohort. The protein ID lists were run through UniProt's Retrieve/ID mapping tool (Consortium, 2021) to identify obsolete entries (none were identified); of note, gene nomenclature was acquired from UniProt in October 2021. After the aforementioned processes, >96% of proteins identified in both batches were deemed eligible for downstream analyses. Within each cohort, we ran a mixed imputation that utilized the k‐nearest neighbour method for data missing at random and the zero method for data missing not at random. Because our script derived from the DEP R package (Zhang et al., 2018), values were log scaled during imputation. Thus, we reversed the log scaling and compiled the two cohorts’ data together.

After imputation, samples from both batches were normalized by sample loading; importantly, the pooled batch standards were not included in the computation of the global scaling value. Then samples were normalized by trimmed mean of M values, the reference column for which was not allowed to be one of the pooled batch standards. Finally, each batch underwent internal reference scaling (Plubell et al., 2017) to its pooled batch standard. This series of steps allowed for cross‐comparison across batches. Once normalized, the data were compared using Edger (the data were fit to a quasi‐likelihood negative binomial generalized linear model, and empirical Bayes quasi‐likelihood F tests were used to determine differential expression; Robinson et al., 2010). A Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons was used to acquire FDR‐adjusted P‐values. The script can be found at: https://github.com/AndreaWiley/MousePoWeR2GroupDEPanalysis.

BETA, gene ontology and transcriptional regulator analysis

We presented the integration of RRBS and RNA‐seq data using BETA in a previous publication (Ismaeel et al., 2024). BETA was first developed as software that provides an integrated analysis of transcription factor binding to genomic DNA and transcript abundance using chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP‐seq) and transcriptomics (RNA‐seq) datasets (Wang et al., 2013). The underlying algorithm of BETA takes into consideration the distance of the regulatory element relative to the transcription start site (TSS) by modelling the effect of regulation using a natural log function, termed the regulatory potential, as described previously by Tang et al. (2011). CpG sites were converted into ‘methylation peaks’ as a surrogate for transcription factor binding peaks, with the significance scores being the −log2(P‐value). Gene names from the proteomics analysis acquired from UniProt were included as the input along with corresponding log2FC and P‐values. The BETA basic command was run with the following parameters ‘–gname2 ‐k BSF ‐g mm10 ‐c 0.05 –da 500’. To determine whether methylation has regulatory potential, a non‐parametric statistical test contrasted regulatory potentials for differentially methylated CpGs upstream or downstream of the TSS with differentially expressed proteins in the experiment (in this instance, PoWeR vs. SED defines the differential expression). α for the BETA integration analysis was set at P < 0.05, and individual comparisons were reported using rank product analysis (Breitling et al., 2004). It is worth noting that the genomic location information for CpGs from the array was used for the BETA input, and given the nature of the BETA algorithm is based on regulatory potential, sometimes regulation of genes that differed from the genes that were classified in the array was identified, which is purely based on distance to the TSS.

Differentially expressed protein lists as well as BETA results (adj. P < 0.05) were uploaded into ShinyGO as gene symbols (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/) (Ge et al., 2020) and over‐representation analyses for molecular functions were performed using an FDR cutoff of 0.05. Figures were extracted from ShinyGO. All other figures were generated using GraphPad Prism version 7.00 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) and BioRender.com.

Landscape In Silico deletion Analysis (Lisa) was run according to the recommended procedures as reported by Qin et al. (2020), consistent with our previous work (Jones et al., 2023; Murach, Liu, et al., 2022). In brief, the list of proteins differentially expressed (P < 0.05) in PoWeR mice relative to SED mice were run with LISA2 software from http://lisa.cistrome.org using the command line (so that all differential proteins could be utilized), and the Cauchy combination test P‐value was used to determine significance followed by deduplication to extract unique transcriptional regulators.

To determine relationships between the skeletal muscle proteome and variables of muscle mass and function, we used Pearson's correlation coefficient (parametric, r, assumes linearity) as well as Kendall's rank correlation coefficient (Kendall's tau, τ, non‐parametric and does not assume linearity and is sensitive to outliers). Results from both analyses are presented, and significance for correlations was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Methylation of conserved CpGs is modified by late‐life PoWeR

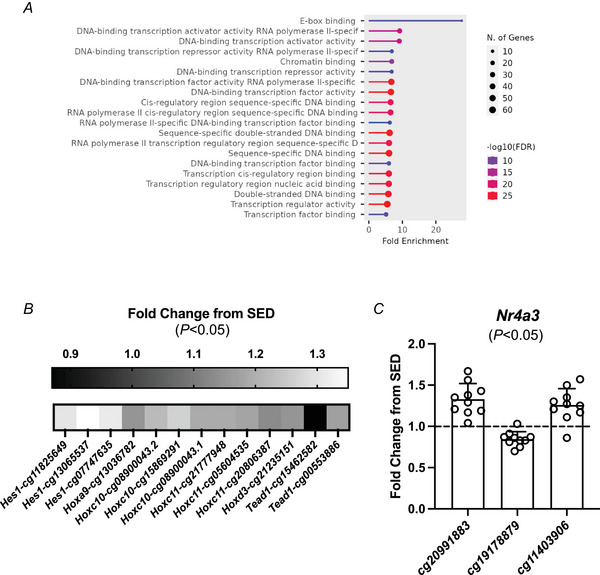

Using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), we previously reported that myonuclear DNA methylation is altered by late‐life PoWeR in the soleus muscle of mice (Dungan et al., 2022). The myonuclear DNA methylome is also affected by PoWeR training as well as acute skeletal muscle overload in young mice (von Walden et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2021). These findings establish that the epigenome in skeletal muscle fibres is modified by muscle loading, even in aged organisms. Muscle fibres adapt profoundly to exercise training and at least 50%–60% of nuclei in murine muscle are myonuclei (von Walden et al., 2020). Thus, measuring DNA methylation changes in muscle tissue is in part due to changes in the muscle fibre. We posit that the methylome and proteome results presented below are in large part reflective of changes within the muscle fibre. While RRBS is high‐coverage, it is generally low‐depth and the CpGs identified by this method are not necessarily conserved across species. This limitation may impact translatability across studies. In the current investigation, we leveraged Horvath pan‐mammalian methylation arrays that utilize conserved CpGs in mice and humans and also contain DNA methylation clock sites (Arneson et al., 2022). After PoWeR, 4919 unique CpG sites (∼13% of measured CpGs) were differentially methylated (DM) (P < 0.05, Supporting information, Supplemental Table S1). Of those, 210 CpGs were in promoter regions and those promoters were most enriched in genes of the molecular function category transcriptional regulation and, specifically, E‐box binding (Fig. 1A ).

Figure 1. Methylation of conserved CpGs is modified by late‐life PoWeR.

A, molecular function analysis of differentially methylated (DM) CpGs in promotor regions after PoWeR (compared to sedentary, SED). B, fold difference with PoWeR compared SED for transcriptional regulators Hes1 (cg11825649, P = 0.008; cg13065537, P = 0.026; cg07747635, P = 0.033), Hoxc10 (cg08900043.2, P = 0.021; cg15869291, P = 0.027; cg08900043.1, P = 0.038), Hoxc11 (cg21777948, P = 0.0006; cg05604535, P = 0.043; cg208086387, P = 0.046), and Tead1 (cg15462582, P = 0.015; cg00553886, P = 0.030) with multiple DM promotor regions and Hoxa9 (cg13036782, P = 0.024) and Hoxd3 (cg21235151, P = 0.034) with a single DM promoter region. C, Nr4a3 DM CpG promotor regions (cg20991883, P = 0.0002; cg19178879, P = 0.0004; cg11403906, P = 0.002) fold difference from SED. Individual fold change data points presented for PoWeR (n = 10) relative to the average of SED (n = 9).

Several transcriptional regulators had multiple DM promoter region CpGs including Hes1, Hoxc10, Hoxc11 and Tead1 (Fig. 1B ). Homeobox A9 (Hoxa9) and Homeobox D3 (Hoxd3) also had a DM promoter region CpG after PoWeR. HOX genes are (1) essential for development (Krumlauf, 1994), (2) reportedly regulated by DNA methylation (Tsumagari et al., 2013), (3) methylation hotspots during ageing in human skeletal muscle (Voisin et al., 2021), and (4) differentially regulated by ageing and physical activity status at the methylation and mRNA levels in humans (Turner et al., 2020). We previously reported that methylation of a Hox gene is affected by myonuclear accretion during exercise in murine myonuclei (Murach, Dungan, et al., 2022), indicating myogenic cell‐ specific regulation in adult muscle. Furthermore, distinct methylation patterns of certain HOX/HOXL genes are associated with longevity across species (Haghani et al., 2023). Methylation changes to HOX genes implicates developmental processes during ageing (Horvath et al., 2023). In skeletal muscle, hes family bHLH transcripton factor 1 (Hes1) and TEA domain family member 1 (Tead1) are generally associated with satellite cell activity (Joshi et al., 2017; Lahmann et al., 2019; Noguchi et al., 2019); however, Tead1 in the muscle fibre may indirectly control satellite cell function (Southard et al., 2016) and promote a slow‐twitch muscle fibre phenotype through development (Tsika et al., 2008). Another gene with several DM CpGs in its promoter was nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 3 (Nr4a3) (Fig. 1C ). In humans, Nr4a3 is among the most exercise‐responsive genes; it is controlled by DNA methylation (Pattamaprapanont et al., 2016) and strongly influences muscle metabolism in preclinical models (Paez et al., 2023; Pearen & Muscat, 2018; Pearen et al., 2008; Pearen et al., 2012; Pearen et al., 2013; Pillon et al., 2020). After high intensity interval exercise in humans, muscle NR4A3 was upregulated 165‐fold and promoter hypomethylation coincided with an increase in gene expression of NR4A1 (Maasar et al., 2021). Perhaps PoWeR‐altered methylation of promoter regions in these genes affects their sensitivity to an acute exercise bout leading to a more ‘primed’ response in muscle fibres when trained (Furrer et al., 2023).

More than 900 proteins are upregulated in skeletal muscle of late‐life PoWeR mice, and around one‐third of proteins correspond with the proteome response to weighted wheel running in young mice

After PoWeR, 1032 proteins were differentially expressed, with 931 of these (90%) upregulated relative to SED control mice (adj. P < 0.05, Supporting information, Supplemental Table S2). Molecular function categories for upregulated proteins were largely related to RNA binding, translational regulation and NADH dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 2A ). According to adjusted P‐value, the five most upregulated proteins with PoWeR were ankyrin repeat and SOCS box protein 6 (ASB6, adj. P = 0.0000005), retinosa pigmentosa 2 (RP2, adj. P = 0.0000009), ribosomal protein large 38 (RPL38, adj. P = 0.0000009), NADH dehydrogenase 1 β subcomplex subunit 5 (NDUFB5, adj. P = 0.000004), and Wiscott–Aldrich syndrome protein family member 2 (WASF2, adj. P = 0.000004). To our knowledge, only WASF2 (WAVE2) has been implicated in skeletal muscle. The WAVE–WASP network is known to affect muscle stem cell (satellite cell) biology (Gildor et al., 2009; Gruenbaum‐Cohen et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2007; Murach, Vechetti Jr, et al., 2020). WAVE2 specifically may affect myogenic regulatory factors and myogenic cell migration (Kawamura et al., 2004; Nguyen et al., 2023). ASB2 – in the same family as ASB6 – has been implicated in skeletal muscle mass regulation and responsiveness to loading (Gilbert et al., 2024) as well as muscle disease (Ehrlich et al., 2020). ASBs typically function as E3 ubiquitin ligases and ASB6 is involved in autophagy (Gong et al., 2021) and insulin signalling (Wilcox et al., 2004), but the role of ASB6 in skeletal muscle is not defined. According to log fold change (adj. P < 0.05), the proteins with the largest upregulation were immunoglobulins (Supporting information, Supplemental Table S2). ASB6, RP2, RPL38 and WASF2 were also among the top 15 proteins according to fold change. Other highly upregulated proteins worth mentioning are ACTN2 and TPM3. Mutations to ACTN2 and TPM3 both result in myopathy (Donkervoort et al., 2015; Inoue et al., 2021; Lambert & Gussoni, 2023; Lornage et al., 2019; Ranta‐Aho et al., 2022; Savarese et al., 2019), with the latter being linked to calcium handling that is most evident in slow‐twitch muscle fibres (Yuen et al., 2015). How any of the aforementioned proteins contribute to late life‐exercise adaptation in skeletal muscle is not yet clear. ACTN3, a z‐disk protein, was a top 30 upregulated protein according to fold change and has a clear role in skeletal muscle. Its abundance is linked to muscle performance, mass, metabolism, fibre type, contractile speed and trainability (Broos et al., 2016; Clarkson et al., 2005; Del Coso et al., 2019; MacArthur et al., 2007; MacArthur et al., 2008; Seto et al., 2013; Vincent et al., 2007). ACTN3 induction in mouse muscle late in life with exercise training may therefore be beneficial.

Figure 2. Upregulated proteins in skeletal muscle after late‐life PoWeR.

A, molecular function analysis of upregulated proteins after PoWeR relative to SED. B, ASB6 (UniProt ID: Q91ZU1, adj. P = 0.0000005), RPL38 (Q9JJI8, adj. P = 0.0000009), RP2 (Q9EPK2, adj. P = 0.0000009), NDUFB5 (Q9CQH3, adj. P = 0.000004) and WASF2 (Q8BH43, adj. P = 0.000004) upregulation fold difference from SED after PoWeR. C, Xpo1 (cg09455096, P = 0.003 and cg08330824, P = 0.009) and Lpp (cg14306812, P = 0.01) promoter CpG methylation and corresponding protein upregulation (XPO1 adj. P = 0.016; LPP adj. P = 0.023) fold difference from SED after PoWeR. Individual fold change data points presented for PoWeR (n = 7) relative to the average of SED (n = 7). D, the relationship of CpG percentage methylation (any genomic context) after PoWeR to corresponding protein fold‐change for significant proteins (r = 0.123, r 2 = 0.015, P = 0.06). E, the relationship of CpG percentage difference from sedentary after PoWeR (any genomic context) to its corresponding protein fold‐change for significant proteins (r = −0.017, r 2 = 0.0003, P = 0.80).

A recent study used a 10‐week resistance wheel running intervention in young C57BL/6J mice (16 weeks of age at start) to survey the proteomic response to training in muscles using tandem mass spectrometry (Leuchtmann et al., 2023). The training protocol, equipment and duration were different from this investigation, as was the sex of the mice (n = 4 males/group), muscles analysed (plantaris and soleus) and analysis approach. Accepting these limitations, we performed a preliminary analysis to determine the degree of overlap in the muscle proteome of young versus old mice using differentially upregulated proteins. In the plantaris muscle of young male mice – which has a fibre type profile that is roughly similar to the gastrocnemius – 966 proteins were elevated after training (Leuchtmann et al., 2023) (P < 0.05). This number of differentially expressed upregulated proteins (reported at P < 0.01) was strikingly similar to what we observed with late‐life PoWeR in the gastrocnemius (adj. P < 0.05). Approximately 30% of those plantaris proteins overlapped with the late‐life PoWeR gastrocnemius proteome. The molecular function category for overlapping proteins was related to NADH dehydrogenase activity; this commonality included numerous mitoribosomal proteins. For proteins only upregulated in young with resistance wheel running, the molecular function categories most enriched were propanoate metabolism and TCA cycle. The molecular function category most enriched based on FDR adj. P‐value/fold enrichment was the ribosome pathway for proteins only upregulated with late‐life PoWeR. There were fewer proteins upregulated in the soleus versus plantaris muscle of young male mice after resistance wheel running (227 proteins, P < 0.05) (Leuchtmann et al., 2023). Agreement between the late‐life PoWeR gastrocnemius proteome and the young soleus proteome with resistance running was minimal (25 proteins). This exploratory comparison suggests intersecting as well as potentially distinct regulation of the proteome with exercise according to age in skeletal muscle. All the aforementioned comparisons are presented in Supporting information, Supplemental Table S3.

Promoter DNA hypomethylation relates to upregulated LPP and XPO1 protein after PoWeR

Although the methylation arrays we used only cover ∼36,000 CpGs, we performed a conventional comparison of upregulated proteins to DNA hypomethylation of DM promoter CpGs after PoWeR. It is generally considered that promoter and first exon hypomethylation relates to positive regulation of gene expression (Brenet et al., 2011; Feinberg & Vogelstein, 1983), as was first reported in skeletal muscle for PGC1α (Barrès et al., 2012). On balance, the relationship between methylation and gene expression can be complicated and potentially uncoupled by the ageing process (Marttila et al., 2015; Steegenga et al., 2014; Wierczeiko et al., 2018). With these considerations in mind, our analysis revealed potential epigenetic regulation of two proteins: lipoma‐preferred partner homolog (Lpp) and exportin‐1 (Xpo1) (Fig. 2C ). Lpp is typically associated with smooth muscle (Gorenne et al., 2003) and Xpo1 with inflammatory muscle diseases (García‐Manzanares et al., 2020; Hightower et al., 2020). It is worth noting that Lpp also had a hypermethylated CpG in its promoter after PoWeR (Supporting information, Supplemental Table S4). The ramifications of epigenetic regulation of LPP and XPO1 in skeletal muscle with late‐life exercise are not yet clear, but prior work has implicated LPP and nuclear export genes in skeletal muscle of aged humans (Tumasian 3rd et al., 2021). Further overlap analysis of CpG site hypo/hypermethylation and up/downregulated proteins can be found in Supporting information, Supplemental Table S4. The greatest overlap was between hypermethylated exons and corresponding upregulated proteins after PoWeR. There was a trending relationship (P = 0.06, r 2 = 0.015) (Fig. 2D ) for absolute CpG percentage methylation after PoWeR to its corresponding protein fold‐change (relative to SED) for all significantly different proteins. However, this relationship was diminished when correlating the CpG percentage difference in methylation from SED to its corresponding protein fold‐change relative to SED for all differentially expressed proteins after PoWeR (P = 0.80; r 2 = 0.0003) (Fig. 2E ). The aforementioned correlations included all significant CpGs corresponding to a significantly different protein regardless of genomic context (promoter, exon, intron, etc.).

BETA integration of the DNA methylome and proteome predicts epigenetic regulation of ribosomal, mitoribosomal and mitochondrial complex I proteins in skeletal muscle after PoWeR

The control of gene expression by DNA methylation is not fully understood and sometimes paradoxical (Bahar Halpern et al., 2014; López‐Moyado et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2020). During skeletal muscle development, there is a relationship between DNA methylation of promoters as well as gene bodies to myogenic gene expression, and methylation regulation varies according to distance from the TSS (Yang et al., 2021). Due to the complex and often unknown regulation of gene expression by DNA methylation, we employed a holistic approach called BETA that considers methylation patterns (agnostically) around a gene as well as proximity to transcription start sites (Ismaeel et al., 2024). This approach yielded targets that were predictive of in vivo skeletal muscle mitochondrial function (Ismaeel et al., 2024). BETA may therefore provide a better understanding of the potential regulation of proteins by DNA methylation beyond what individual CpG–protein relationships/correlations might provide.

BETA analysis was significant for upregulated proteins in PoWeR relative to SED (P = 0.0317, Fig. 3A ) but not downregulated proteins (P = 1.0). DNA methylation status was predictive of upregulation of 216 proteins (Supporting information, Supplemental Table S5). Pathway enrichment analysis revealed epigenetic regulation of translation – the majority of these proteins were ribosomal or mitoribosomal proteins (Fig. 3B ). Upregulated ribosomal proteins (RP) according to rank product from BETA were: RPL6, RPL18, RPL29, RPL31, RPLP0, RPS10 and RPS14. Ribosomal proteins are known to be controlled by DNA methylation due to high CpG density in promoter regions (Roepcke et al., 2006; Yoshihama et al., 2002). This known regulation of ribosomal proteins in combination with our previous work (Ismaeel et al., 2024) in part validates the predictive power of the BETA approach. We previously reported on possible regulation of ribosomal protein genes by DNA methylation specifically in myonuclei with PoWeR (Murach, Dungan, et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2021), which supports our findings here. In addition to ribosomal proteins, several eukaryotic translation initiation factors (EIF) were also predicted by BETA to be regulated by DNA methylation: EIF2B3, EIF2B4, EIF2B5 and EIF3D (Fig. 3C ). Recent studies implicate EIF3D as an essential component of the cellular stress response, phenotype switching and specialized translation initiation (Lamper et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2016; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2023; Shin et al., 2023; Thompson et al., 2022). These functions of EIF3D may confer some advantage to trained skeletal muscle late in life. Also, depletion of EIF3 components leads to mitochondrial abnormalities and compromised muscle health (Lin et al., 2020). Other EIFs such as EIF2B4 and EIF2B5 are implicated in muscle mass regulation (Liang et al., 2021; Spurlock et al., 2006). Altogether, late‐life PoWeR increases the abundance of proteins involved in global translation that may be regulated by DNA methylation.

Figure 3. BETA integration of the DNA methylome and proteome predicts epigenetic regulation of proteins after late‐life PoWeR.

A, BETA analysis of the relationship between CpG methylation status and upregulated (P = 0.03) and downregulated (P = 1.0) proteins after PoWeR compared to background. Key ribosomal proteins (RPL6, adj. P = 0.002; RPL18, adj. P = 0.006; RPL29, adj. P = 0.0006; RPL31, adj. P = 0.005; RPLP0, adj. P = 0.001; RPS14, adj. P = 0.01), translational initiation factors (EIF2B3, adj. P = 0.004; EIF2B4, adj. P = 0.010; EIF2B5, adj. P = 0.010; EIF3D, adj. P = 0.006), mitoribosomal proteins (MRPL1, adj. P = 0.0006; MRPL2, adj. P = 0.001; MRPL4, adj. P = 0.002; MRPL10, adj. P = 0.0001; MRPL11, adj. P = 0.003; MRPL14, adj. P = 0.003, MRPL28, adj. P = 0.0004; MRPL37, adj. P = 0.00004; MRPL43, adj. P = 0.003; MRPL45, adj. P = 0.0002; MRPL46, adj. P = 0.001; MRPL, 53 adj. P = 0.010; MRPS11, adj. P = 0.0002; MRPS22, adj. P = 0.001; MRPS25, adj. P = 0.0001), mitochondrial complex I proteins (NDUFA2, adj. P = 0.0009; NDUFA3, adj. P = 0.002; NDUFA8, adj. P = 0.002; NDUFB3, adj. P = 0.0003; NDUFB9, adj. P = 0.002;NDUFB11, adj. P = 0.001; NDUFC2, adj. P = 0.0008; NDUFS1, adj. P = 0.002; NDUFS2, adj. P = 0.002; NDUFS6, adj. P = 0.010; NDUFS7, adj. P = 0.0009; TIMMDC1, adj. P = 0.004; TMEM186, adj. P = 0.0007), and proteins critical toskeletal muscle health (LACTB, adj. P = 0.000009; MIB1, adj. P = 0.0009; UBR4, adj. P = 0.001). B–F, histograms plotting the fold‐change difference with PoWeR relative to SED. Individual fold change data points are presented for PoWeR (n = 7) relative to the mean of SED (n = 8). G, the relationship of the BETA score and the methylation distance from the transcriptional start site (in base pairs) for upregulated proteins. H, Lisa cistrome results for the top 10 transcription factors (TFs) using the upregulated proteins that BETA predicted to be significantly influenced by their methylation status as determined by −log10 P‐value. I, Lisa results for the top 10 TFs using all upregulated proteins as determined by −log10 P‐value.

Mitochondrial translation proteins were associated with DNA methylation alterations after late‐life PoWeR according to BETA. Upregulated mitoribosomal proteins predicted by BETA were: MRPL1, MRPL2, MRPL4, MRPL10, MRPL11, MRPL14, MRPL28, MRPL37, MRPL43, MRPL45, MRPL46, MRPL53, MRPS11, MRPS22 and MRPS25 (Fig. 3D ). Numerous mitochondrial complex I proteins were also predicted by BETA to be regulated by DNA methylation status. These proteins were: NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (NDU) subunit A2 (NDUFA2), NDUFA3, NDUFA8, NDUFB11, NDUFB3, NDUFB9, NDUFC2, NDUFS1, NDUFS2, NDUFS6, NDUFS7, NDUFV3, translocase of inner mitochondrial membrane domain containing 1 (TIMMDC1) and transmembrane protein 186 (TMEM186) (Fig. 3E ). We previously found that late life PoWeR as well as epigenetic partial reprogramming lowered Ndufb11 mRNA levels in the soleus muscle of mice (Jones et al., 2023). We also reported lower Romo1 mRNA levels in the soleus after late‐life PoWeR (Jones et al., 2023), but ROMO1 protein (not predicted by BETA) was slightly elevated in the gastrocnemius (logFC = 0.23, adj. P = 0.013). Elevated NDUFB11 and ROMO1 at the protein level here could be specific to the gastrocnemius muscle, reflect a disconnect between mRNA and protein levels, and/or be related to the timing of tissue harvest after the final exercise bout not being optimal for comparing the mRNA to protein response. BETA scores and where CpGs are located relative to the TSS for the genes encoding the protein classes mentioned above are in Fig. 3G .

BETA integration of the DNA methylome and proteome predicts epigenetic regulation of proteins mechanistically linked to skeletal muscle health

BETA predicted methylation regulation of several other key proteins with late life PoWeR: serine β‐lactamase‐like protein LACTB (LACTB), MIB E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (MIB1), and ubiquitin protein ligase E3 compenent n‐recognin 4 (UBR4) (Fig. 3F , Supporting information, Supplemental Table S6). Using skeletal muscle as a model tissue since muscle fibres are resistant to cancer, LACTB was identified as a tumour suppressor due to its ability to alter lipid metabolism (Keckesova et al., 2017). It is also a regulator of intramitochondrial membrane organization (Polianskyte et al., 2009) and is reportedly part of the mitoribosomal complex (Chen et al., 2008). MIB1 maintains type 2 glycolytic fibres with ageing (Seo et al., 2021). This is important since type 2 muscle fibres specifically atrophy throughout the lifespan, which may deleteriously affect muscle mass and function (Grosicki et al., 2022; Holloszy et al., 1991; Lexell et al., 1983; Nilwik et al., 2013; Yamaguchi et al., 2025). MIB1 in muscle fibres also maintains muscle stem cell diversity (Eliazer et al., 2022). The Mib1 gene contains one allele of miR‐1, a myomiR that may influence muscle mitochondrial metabolism (Wüst et al., 2018) and neuromuscular junction stability (Klockner et al., 2022). UBR4 is essential for protein quality control in skeletal muscle throughout the lifespan of model organisms (Hunt et al., 2019; Hunt et al., 2021). Other UBRs such as UBR5 are also central to skeletal muscle mass regulation and are seemingly influenced by DNA methylation during exercise (Hughes et al., 2021; Hughes et al., 2023; Seaborne et al., 2018; Seaborne et al., 2019). BETA scores and where CpGs are located relative to the TSS for genes coding the muscle health‐related proteins mentioned above are shown in Fig. 3G . Collectively, BETA suggests epigenetic regulation by late‐life exercise of several proteins that are mechanistically linked to skeletal muscle health.

Information on the major transcriptional regulators of the trained proteome using computational cistrome analysis

To gain insight on what transcription factors may regulate the proteomic signature of late‐life training adaptation in skeletal muscle while accounting for the potential influence of DNA methylation status, we utilized landscape in silico deletion analysis (Lisa) (Qin et al., 2020) (Supporting information, Supplemental Table S7). We leveraged Lisa previously to infer transcriptional regulators in skeletal muscle that we previously validated using a doxycycline‐inducible muscle‐specific MYC overexpressing mouse (Iwata et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2023; Murach, Liu, et al., 2022). Using the BETA gene names list corresponding to upregulated proteins, the top 10 transcription factors predicted to regulate the muscle proteome after late life PoWeR were: transcription elongation factor SPT5 (SUPT5H), general transcription factor IIB (GTF2B), transcription factor 7 (TCF7), CXXC finger protein 1 (CXXC1), K(lysine) acetyltransferase 2B (KAT2B), recombination activating gene 2 (RAG2), histone H3 phospho Ser28 (H3S28ph), recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobin kappa J region (RBPJ), myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC), and zinc finger protein 57 (ZFP57) (Fig. 3H ). MYC is also one of the top transcriptional regulators when performing Lisa with the entire list of upregulated proteins after PoWeR (Fig. 3I and Supporting information, Supplemental Table S7).

Associating the proteome to muscle mass and in vivo muscle function uncovers new potential regulators of skeletal muscle health

We used normalized proteomic values for each sample to correlate to different features of skeletal muscle in our SED and PoWeR mice. These features were absolute and body weight‐normalized gastrocnemius mass, in vivo plantarflexor fatigue at 60 Hz stimulation, and cumulative in vivo plantarflexor work. The functional measures are primarily a measure of gastrocnemius function, which is the muscle used for methylomics and proteomics in this study. The average values for these measures in SED and PoWeR mice are in Table 1.

Several mitochondrial, mitoribosomal, and ribosomal proteins positively correlated to absolute and normalized muscle mass (Supporting information, Supplemental Table S8). Vacuolar protein sorting 13 homolog A (VPS13A) was among the most correlated proteins to absolute (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.84, r 2 = 0.71, P = 0.00008, Kendall's τ = 0.66, P = 0.0006) and normalized mass (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.82, r 2 = 0.68, P = 0.0002, Kendall's τ = 0.58, P = 0.0025) (Fig. 4A ). Also worth noting is that LACTB (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.76, r 2 = 0.57, P = 0.001, Kendall's τ = 0.58, P = 0.0025) and mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (MTOR) (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.72, r 2 = 0.51, P = 0.003, Kendall's τ = 0.49, P = 0.012) correlated well to absolute muscle mass. LACTB is implicated in muscle health (see above) and MTOR – specifically mTORC1 – is a central regulator of muscle phenotype and hypertrophic adaptation (Bodine et al., 2001; Crombie et al., 2023; Goodman et al., 2011; Ham et al., 2020; Roberts et al., 2023) (see Supporting information, Supplemental Table S7).

Figure 4. Relationship of the skeletal muscle proteome to skeletal muscle mass and in vivo function.

A, the relationship of VPS13A protein abundance to absolute gastrocnemius mass (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.84, r 2 = 0.71, P = 0.00008, Kendall's τ = 0.66, P = 0.0006) and normalized mass (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.82, r 2 = 0.68, P = 0.0002, Kendall's τ = 0.58, P = 0.0025) (SED, n = 8; PoWeR, n = 7). B, the relationship of MYL12B (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.87, r 2 = 0.75, P = 0.0001, Kendall's τ = 0.77, P = 0.0003) and NPL (Pearson coefficient r = 0.77, r 2 = 0.60, P = 0.002, Kendall's τ = 0.72, P = 0.0006) protein abundance to in vivo plantar flexor fatigue resistance at 60 Hz stimulation (SED, n = 6; PoWeR, n = 7). C, the relationship of MYL12B (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.91, r 2 = 0.83, P = 0.0003, Kendall's τ = 0.64, P = 0.0095) and NPL (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.80, r 2 = 0.64, P = 0.006, Kendall's τ = 0.56, P = 0.025) (SED, n = 3; PoWeR, n = 7) protein abundance to in vivo total work. Individual data points presented for SED (black) and PoWeR (red). Data for fatigue resistance and total work calculations were not recorded for three SED mice and one PoWeR mouse since these mice exhibited cumulative workloads that suggested an inability to perform the task.

Myosin light chain 12B (MYL12B) and N‐acetylneuraminate pyruvate lyase (NPL) were the proteins most positively correlated to plantarflexor fatigue resistance at 60 Hz stimulation (i.e. strength of final contraction) (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.87, r 2 = 0.75, P = 0.0001, Kendall's τ = 0.77, P = 0.0003 and r = 0.77, r 2 = 0.60, P = 0.002, Kendall's τ = 0.72, P = 0.0006, respectively) (Fig. 4B ). Both were also positively correlated to cumulative work (Pearson's coefficient r = 0.91, r 2 = 0.83, P = 0.0003, Kendall's τ = 0.64, P = 0.0095 and r = 0.80, r 2 = 0.64, P = 0.006, Kendall's τ = 0.56, P = 0.025, respectively) (Fig. 4C ).

Discussion

Ageing coincides with inactivity (Russ & Kent‐Braun, 2004) and compromised mitochondrial (de Smalen et al., 2023; Shcherbakov et al., 2021; Tharakan et al., 2021; Ubaida‐Mohien et al., 2022) and complex I protein translation in skeletal muscle (Kruse et al., 2016). A recent study in mice identified altered mitochondrial metabolism as a primary driver of muscle atrophy during ageing (Fernando et al., 2023). Work utilizing proteomics in human skeletal muscle associated the abundance of complex I proteins with higher skeletal muscle oxidative capacity and metabolically healthier muscle throughout the lifespan (Adelnia et al., 2020; Ubaida‐Mohien et al., 2019; Ubaida‐Mohien et al., 2022). Using our late‐life combined exercise approach, we extend these findings to suggest that complex I proteins may be epigenetically regulated during exercise adaptation in female mice. This is noteworthy since ageing appears generally characterized by changes to methylation of metabolism‐related genes (Thompson et al., 2010). We have identified overlap in NADH dehydrogenase and mitoribosomal proteins in skeletal muscle with weighted wheel running in young mice published previously (Leuchtmann et al., 2023) versus the aged mice used here, suggesting ageing‐independent regulation by exercise in mice. Our results implicated LACTB, MIB1 and UBR4 as exercise training‐responsive proteins that may be controlled epigenetically. We then provided evidence that MYC likely plays a central role in mediating the late‐life exercise proteome in skeletal muscle. The inclusion of exclusively female mice offers insights into sex‐focused epigenetic and proteomic adaptations to exercise training with ageing. In humans, ‐omics analyses have highlighted biological sex differences both at baseline and after training that may drive some differential beneficial adaptations to exercise in skeletal muscle (Landen et al. 2021; Landen et al. 2023). The exploratory findings of this study provide a resource for targeting epigenetic and proteomic markers that may benefit skeletal muscle health with exercise and ageing in females. Altered proteostasis is a hallmark of ageing and is compromised in skeletal muscle (O'Reilly et al., 2025). Our data provide insights on the potential regulation of proteostatic mechanisms by exercise in skeletal muscle with ageing by way of altering aspects of the translational machinery at the epigenetic and protein levels.

Regulation of the mitoribosome by exercise was a major outcome of our integrated methylomic–proteomic analysis. Mitoribosomes are essential for the synthesis of bioenergetic proteins and are thus key regulators of mitochondrial health. The unique nature of mitoribosomes has been recognized for over 20 years (Sharma et al., 2003). However, high‐fidelity isolation and characterization of mitoribosomes via a genetically modified mouse model was not described until recently (Busch et al., 2019). Furthermore, detailed information on the biogenesis, assembly, structure and function of the mitoribosome has only been provided in the last several years (Amunts et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2017; Greber et al., 2014; Harper et al., 2023; Hillen et al., 2021; Itoh et al., 2022; Jaskolowski et al., 2020). The contribution of mitoribosomes to skeletal muscle exercise adaptation is therefore relatively unexplored. One recent study reported that some mitoribosomal mRNAs and proteins are reduced by ageing in skeletal muscle of mice which coincides with lower mitochondrial translation; this can be rescued by treadmill running late in life (de Smalen et al., 2023). These findings are consistent with our work. A recent proteomics study reported elevated mitoribosomal protein content in muscle of lifelong endurance athletes but not strength athletes (Emanuelsson et al., 2024). Late‐life resistance training in humans enhances mitoribosomal protein abundance, but to a lesser extent than high intensity interval training (Robinson et al., 2017). These observations collectively point to the high‐volume endurance component of PoWeR as the most likely explanation for our mitoribosomal protein observations.

Higher abundance of mitoribosomal as well as ribosomal proteins in muscle with late‐life exercise could be related to ribosome biogenesis to enhance overall translation, as is thought to happen in aged humans in response to resistance training and high‐intensity interval training (Robinson et al., 2017). Another possibility is that changes in mitoribosomal and ribosomal proteins could be related to ribosome heterogeneity and specialization (O'Brien, 2003; Zhang et al., 2015). The impact of ribosome specialization deserves further consideration in the context of exercise adaptation in skeletal muscle (Chaillou, 2019). The mutation of a single mitoribosomal protein (e.g. MRPS16) is sufficient to cause a mitochondrial respiratory chain disorder (Miller et al., 2004), and the manipulation of mitonuclear protein imbalance by disruption of mitoribosomal proteins can affect longevity in preclinical models (Houtkooper et al., 2013). Similarly, alteration to a single ribosomal protein (RPS28) can change the muscle proteome during Drosophila ageing (Jiao et al., 2021). These findings point to the powerful role of mitoribosomal and ribosomal proteins in skeletal muscle health throughout the lifespan. Since ageing is characterized by altered proteostasis and particularly mitochondrial protein metabolism in skeletal muscle (Drake & Yan, 2017), exercise may in part counteract that occurrence via epigenetic regulation of mitoribosomal and ribosomal proteins and improved translation and/or translational fidelity.

We leveraged the computational ChIP‐seq tool Lisa (Qin et al., 2020) to identify potential transcriptional regulators of the late‐life PoWeR methylome and proteome. Most of the transcription factors identified are not well‐characterized in the context of skeletal muscle adaptation to exercise. Some recent work suggests epigenetic regulation of SUPT5H with exercise in skeletal muscle (Gorski et al., 2023), and ZFP57 can affect Irisin expression in myotubes (Guo et al., 2023). However, we have previously reported on MYC as a potentially important regulator of exercise adaptation – specifically hypertrophic exercise (Figueiredo et al., 2021; Jones et al., 2023, 2024; Murach, Liu, et al., 2022) – and demonstrated its ability to influence DNA methylation status in skeletal muscle (Jones et al., 2023). MYC is known to alter DNA methylation in different cell types via interactions with methyltransferase enzymes (Brenner et al., 2005; Poole et al., 2019). MYC also binds E‐boxes, which is noteworthy since promoter methylation in E‐boxes was altered by PoWeR in the current investigation. Lisa on the proteome supports our findings of MYC activity as a key influence on the late‐life PoWeR transcriptome in the soleus muscle of mice (Jones et al., 2023), as well as the mechanical overload transcriptome in plantaris muscle myonuclei of young mice (Murach, Liu, et al., 2022). Of the top 10 transcription factors predicted by Lisa to most influence the late‐life PoWeR transcriptome (Jones et al., 2023) and proteome, two were in common: MYOG – a muscle‐specific bHLH transcription factor (Wright et al., 1989) – and MYC. Loss of MYC is implicated in low muscle mass in preclinical models (Demontis & Perrimon, 2009; Wang et al., 2023), but more research on the effects of MYC in aged skeletal muscle and the interaction with exercise is warranted (Jones et al., 2024).

We sought to provide insights on proteins related to muscle mass and function in SED and PoWeR mice. By correlating the proteomic data to gastrocnemius muscle weights and in vivo plantarflexor functional measures, we reveal potential novel regulators of skeletal muscle health. VPS13A was highly correlated to muscle mass in aged mice. As a protein that interacts with TBC1D1, VPS13A can influence GLUT4 trafficking in myotubes in vitro (Hook et al., 2020). VPS13A may also impact mitochondrial–endosomal interactions (Muñoz‐Braceras et al., 2019) as well as mitochondrial morphology and lipid droplet mobility (Yeshaw et al., 2019). More experimentation is required to determine the significance of VPS13A in skeletal muscle, but our data suggest a role in muscle mass maintenance that is related to metabolic health. MYL12B has not been heavily studied in skeletal muscle, but we previously reported persistent CpG promoter hypomethylation of Myl12b in myonuclei as well as interstitial nuclei after PoWeR in young mice (Wen et al., 2021). A single cell transcriptome atlas of murine skeletal muscle suggests Myl12b is most enriched in immune, fibrogenic and endothelial cells, but not myonuclei (McKellar et al., 2021). How MYL12B could contribute to muscle function is not yet clear, but it likely relates to an effect in muscle mononuclear cells. To our knowledge, NPL has not previously been associated with muscle function in the context of exercise with ageing. Using short‐term synergist ablation mechanical overload of the plantaris, however, we reported a robust upregulation of Npl mRNA in myonuclei of young mice (logFC = 2.6, adj. P = 0.000002) (Murach, Liu, et al., 2022). NPL is a key component of sialic acid catabolism, and sialic acids are important components of glycoproteins and glycolipids. Sialyation of glycoproteins is linked to various aspects of muscle biology and function (Chen et al., 2021; Cho et al., 2017; Iwata et al., 2013). Sialytion may be altered with ageing in skeletal muscle and potentially lead to dysfunction (Hanisch et al., 2013; Marini et al., 2021), but this is relatively unexplored. Recently, NPL was found to be essential for in vivo skeletal muscle function (Da Silva et al., 2023; Wen et al., 2018) – specifically fatigue‐resistance – as well as regenerative capacity (Da Silva et al., 2023). NPL deficient mice have muscle structural abnormalities that include branched fibres, irregular mitochondria and distended Golgi cisternae; these aberrations likely underpin muscle functional decrements in the absence of NPL (Da Silva et al., 2023). Perhaps higher NPL levels promote enhanced muscle function and offset some deleterious effects of ageing. The power of our late‐life ‐omics dataset is underscored by relating it to key phenotypic outcomes, leading to new research directions for exploring exercise‐regulated therapeutic targets in muscle.

Study limitations

The mice used in this study were exclusively female as they consistently complete more volume than their male counterparts while performing PoWeR training. Female mice do not undergo menopause naturally (but undergo ‘oestropause’) and we did not chemically induce menopause to mimic the natural onset observed in humans. Future investigations should aim to tease out the effects of menopause and other hormonal fluctuations on late‐life training responses in female skeletal muscle. Additionally, PoWeR mice completed their training while being single‐housed. We did not account for the possible stress that may come with single‐housing of our mice. It is also worth noting that there is not a perfect concurrent exercise training analogue for mice that directly translates to human concurrent training (Murach, McCarthy, et al. 2020). Nevertheless, high‐volume PoWeR is perhaps more translatable than approaches such as synergist ablation, and also induces classic muscle adaptations to resistance and endurance exercise (Dungan et al. 2022) without being invasive. Finally, late‐life PoWeR causes marked changes in gastrocnemius muscle phenotype including fibre type transformations and changes to myonuclear number (Dungan et al. 2022). The methylomic and proteomic changes we observe could be a direct consequence of these specific cellular shifts, but the extent of this deserves further investigation in future studies.

Conclusion

Combining methylomic with proteomic data identified several regulators of muscle health that are upregulated by exercise, and specifically provided evidence for ribosomal and mitoribosomal protein regulation by DNA methylation with late‐life combined exercise training. Collectively, our data are a resource for identifying new epigenetic and proteomic targets for improving muscle mass and function with exercise in advanced age.

Additional information

Competing interests

Y.W. is the founder of MyoAnalytics LLC. S.J.W. is the founder of Ridgeline Therapeutics. The authors have no other conflicts to declare.

Author contributions

K.A.M., C.S.F., S.J.W. and Y.W. conceived of the study and/or analysis approaches. A.D.‐W., A.H., A.K., G.K., W.‐J.L., C.S.F., Y.W. and K.A.M. analysed data. K.A.M. co‐wrote the manuscript with T.L.C. and K.A.M., and T.L.C. generated figures. A.D.‐W., A.K. and C.S.F. managed and/or performed experiments. S.H., R.B., C.S.F., S.J.W., Y.W. and K.A.M. provided resources, oversight, and intellectual contributions. All authors provided feedback. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 AG080047 to K.A.M. and R00 AR081367 to Y.W. This research was conducted while K.A.M. was a Glenn Foundation for Medical Research and AFAR Grant for Junior Faculty awardee. This work was supported by the Arkansas Integrated Metabolic Research Centre – AIMRC (P20GM139768). This work was also supported by the NIH NIDDK 1R41DK119052‐01, 2018, NIA 1U44AG074107‐01 2021, and the U.S. Department of Defense W81XWH‐19‐1‐0290 2019 to S.W.

Supporting information

Peer Review History

Table S1. Methylation at CpGs sites with late‐life PoWeR. Results describe the CpG identifying basename ID, CG start and end, gene symbol, location category and P‐values the comparison between late‐life PoWeR and SED, individual percentage methylation for each CpG in each animal, and group averages for comparison.

Table S2. Proteomic profile with late‐life PoWeR relative to SED. Results include protein description, corresponding gene symbol, log2FC, FDR‐adjusted P‐value, UniProt accession number, and the normalized protein reporter intensity for each protein analysed in each SED and PoWeR animal, and group averages for comparison of percent and fold‐difference of PoWeR relative to SED. *Gene symbol not specified.

Table S3. Comparison of the upregulated proteins in the gasctrocnemius from the present late‐life PoWer study to proteins in the planataris and soleus in young mice after resistance running (RR) from the Leuchtmann et al., 2023 study. Gene symbols for the cupregulated proteins that were shared (overlap between late‐life PoWeR (gastrocnemius) and young RR), only upregulated after late‐life PoWeR, or only upregulated in young RR are presented for both the plantaris and soleus muscles. Molecular function enrichment for shared upregulated proteins, those only upregulated with PoWeR, and those only upregulated in young RR; enrichment FDR adjusted P‐value, number of genes (nGenes), pathway genes, fold enrichment, and pathway details are presented.

Table S4. Overlap of hypo‐ and hypermethylated CpG sites and differentially expressed proteins after late‐life PoWeR. The 4919 differentially methylated CpG sites were cross‐referenced with the 1032 differentially expressed proteins after late‐life PoWeR. Overlap is presented for hypo‐ and hypermethylated exons, 5′ UTR (fiveUTR), intergenic, introns, promoters, and 3′ UTR (threeUTR) CpG sites to the late‐life PoWeR proteome.

Table S5. BETA analysis of the proteins upregulated by late‐life PoWeR via epigenetic regulation. Chromosome number, start and end sites, RefSeq ID, rank product value, and MGI gene symbol are presented.

Table S6. BETA integration of the skeletal muscle methylome regions upstream of the transcriptional start site and proteome with late‐life PoWeR. Listed are individual CpG sites controlling expression of upregulated proteins (Supplemental Table S4) after late‐life PoWeR. Chromosome number, start and end sites from the array, RefSeq ID, MGI gene symbol, distance from translation start site (TSS), and BETA score are presented.

Table S7. Lisa analysis using the BETA gene names list corresponding to upregulated proteins and the complete upregulated protein list after late‐life PoWeR. TF, P‐value, and negative log10 P‐value are presented. Highlighted cells are those included in Fig. 3H and I.

Table S8. Correlations of absolute gastrocnemius mass, gastrocnemius mass normalized to body weight, final torque during muscular fatigue testing, and total work to protein abundance in SED and PoWeR mice. Individual values are presented for each parameter and individual proteins. *Gene symbol not specified.

Biography

Toby L. Chambers is in his first‐year working as a post‐doctoral scholar with Dr Kevin Murach in the Molecular Muscle Mass Regulation (M3R) Laboratory at the University of Arkansas. He earned his undergraduate and master's degrees in Exercise Science from the University of Central Missouri in Warrensburg, MO, USA. He then completed his doctoral degree in Human Bioenergetics at Ball State University in Muncie, IN, USA. Since 2016, he has been involved in exercise physiology research in areas ranging from ageing and performance to human spaceflight. His research focus includes the molecular mechanisms governing skeletal muscle hypertrophy, particularly with ageing and injury.

Handling Editors: Karyn Hamilton & Christopher Sundberg

The peer review history is available in the Supporting Information section of this article (https://doi.org/10.1113/JP286681#support‐information‐section).

Contributor Information

Yuan Wen, Email: ywen2@uky.edu.

Kevin A. Murach, Email: kmurach@uark.edu.

Data availability statement

Raw and processed methylation data have been deposited at the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) GSE267903, and raw and processed proteomic data are available at MassIVE under dataset identifier MSV000094700. R scripts can be found at https://github.com/AndreaWiley/MousePoWeRStudy2GroupAnalyses.

References

- Adelnia, F. , Ubaida‐Mohien, C. , Moaddel, R. , Shardell, M. , Lyashkov, A. , Fishbein, K. W. , Aon, M. A. , Spencer, R. G. , & Ferrucci, L. (2020). Proteomic signatures of in vivo muscle oxidative capacity in healthy adults. Aging Cell, 19(4), e13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amunts, A. , Brown, A. , Toots, J. , Scheres, S. H. W. , & Ramakrishnan, V. (2015). The structure of the human mitochondrial ribosome. Science, 348(6230), 95–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arneson, A. , Haghani, A. , Thompson, M. J. , Pellegrini, M. , Kwon, S. B. , Vu, H.a , Maciejewski, E. , Yao, M. , Li, C. Z. , Lu, A. T. , Morselli, M. , Rubbi, L. , Barnes, B. , Hansen, K. D. , Zhou, W. , Breeze, C. E. , Ernst, J. , & Horvath, S. (2022). A mammalian methylation array for profiling methylation levels at conserved sequences. Nature Communications, 13(1), 783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar Halpern, K. , Vana, T. , & Walker, M. D. (2014). Paradoxical role of DNA methylation in activation of FoxA2 gene expression during endoderm development. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(34), 23882–23892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrès, R. , Yan, J. , Egan, B. , Treebak, J. T. , Rasmussen, M. , Fritz, T. , Caidahl, K. , Krook, A. , O'gorman, D. J. , & Zierath, J. R. (2012). Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metabolism, 15(3), 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodine, S. C. , Stitt, T. N. , Gonzalez, M. , Kline, W. O. , Stover, G. L. , Bauerlein, R. , Zlotchenko, E. , Scrimgeour, A. , Lawrence, J. C. , Glass, D. J. , & Yancopoulos, G. D. (2001). Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo . Nature Cell Biology, 3(11), 1014–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenet, F. , Moh, M. , Funk, P. , Feierstein, E. , Viale, A. J. , Socci, N. D. , & Scandura, J. M. (2011). DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS ONE, 6(1), e14524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, C. , Deplus, R. , Didelot, C. L. , Loriot, A. , Vir, E. , De Smet, C. , Gutierrez, A. , Danovi, D. , Bernard, D. , Boon, T. , Giuseppe Pelicci, P. , Amati, B. , Kouzarides, T. , De Launoit, Y. , Di Croce, L. , & Fuks, F. O. (2005). Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. European Molecular Biology Organization Journal, 24(2), 336–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling, R. , Armengaud, P. , Amtmann, A. , & Herzyk, P. (2004). Rank products: A simple, yet powerful, new method to detect differentially regulated genes in replicated microarray experiments. Federation of European Biochemical Societies Letters, 573(1–3), 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G. (2002). Messenger RNA decay during aging and development. Ageing Research Reviews, 1(4), 607–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broos, S. , Malisoux, L. , Theisen, D. , Van Thienen, R. , Ramaekers, M. , Jamart, C. , Deldicque, L. , Thomis, M. A. , & Francaux, M. (2016). Evidence for ACTN3 as a speed gene in isolated human muscle fibers. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0150594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]