Abstract

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), characterized by the deposition of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides in the walls of medium and small vessels of the brain and leptomeninges, is a major cause of lobar hemorrhage in elderly individuals. Among the genetic risk factors for CAA that continue to be recognized, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the most significant and prevalent, as its variants have been implicated in more than half of all patients with CAA. While the presence of the APOE ε4 allele markedly increases the risk of CAA, the ε2 allele confers a protective effect relative to the common ε3 allele. These allelic variants encode three APOE isoforms that differ at two amino acid positions. The primary physiological role of APOE is to mediate lipid transport in the brain and periphery; however, it has also been shown to be involved in a wide array of biological functions, particularly those involving Aβ, in which it plays a known role in processing, production, aggregation, and clearance. The challenges posed by the reliance on postmortem histological analyses and the current absence of an effective intervention underscore the urgency for innovative APOE-targeted strategies for diagnosing CAA. This review not only deepens our understanding of the impact of APOE on the pathogenesis of CAA but can also help guide the exploration of targeted therapies, inspiring further research into the therapeutic potential of APOE.

Keywords: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, apolipoprotein E, amyloid β, pathology, diagnosis, therapy

1. Introduction

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is an age-related small vessel disease of the brain that primarily affects the elderly population [1]. Pathologically, it is characterized by the deposition of amyloid peptides, predominantly amyloid-β (Aβ), in the walls of small arteries, veins, and capillaries within the leptomeninges, cerebral cortex, and cerebellar cortex, leading to the disruption of the vascular structure and function, subsequent cerebral hemorrhage and ischemia, and finally, neurological deficits. Studies have delineated four major stages in the development of CAA: [2, 3] (1) disease initiation through cerebral vascular amyloid deposition, (2) physiological alterations in cerebral vessels and the gradual emergence of nonhemorrhagic brain damage, (3) progression to hemorrhagic brain lesions, and (4) damage to the brain parenchyma and cognitive dysfunction. CAA can be classified into two groups: Aβ deposition CAA, which is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is frequently observed in AD research, and other amyloid-related CAAs, which are rare genetic cases [3]. Unless otherwise specified, this text refers to Aβ deposition CAA, also known as sporadic CAA induced by Aβ [4].

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a key transporter protein involved in lipid metabolism that plays a crucial role in the redistribution of cholesterol and other lipids to neurons by binding to APOE receptors on the cell surface. In the central nervous system (CNS), APOE is predominantly expressed in astrocytes, microglia, cells of the vascular wall, and choroid plexus cells; it is expressed at lower levels in stressed neurons than in normal neurons [5]. It plays roles in regulating the blood–brain barrier (BBB), the innate immune system, synaptic functionality, and the accumulation of Aβ, all of which significantly impact neurological health, particularly in association with the pathological conditions of AD and CAA.

The APOE ε4 allele has been identified as the most significant genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, and both the APOE ε4 allele and the ε2 allele have the strongest associations with CAA and other vascular-related disorders [5]. Specifically, APOE ε4 is considered a poor prognostic marker for a variety of neurological diseases and influences the risk and severity of CAA in a level-dependent manner [6]. The APOE protein can form a complex with Aβ [5], interact with Aβ clearance receptors on the BBB, and hinder the binding of Aβ to receptors on the blood vessel wall [6]. This activity affects mainly the generation, aggregation, precipitation, and clearance of Aβ and ultimately leads to increased deposition of Aβ in blood vessels. In contrast, the APOE ε2 allele is associated with the rupture and hemorrhage of Aβ-rich vascular walls, promoting degenerative changes such as fibrinoid necrosis [7].

This paper provides a detailed discussion of the protein structure, subtypes, and functionality of APOE by reviewing the literature and survey data. It offers a multidimensional analysis of the molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology involved in CAA and their potential connections to APOE. Moreover, we explore feasible diagnostic and treatment options for CAA triggered by Aβ.

2. The APOE gene: the key to cerebral amyloid angiopathy

The APOE gene is located on the long arm of human chromosome 19; it is composed of four exons and three introns (totaling 3,597 base pairs) and encodes a protein of 299 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 34 kilodaltons [8]. Three codominant alleles of the APOE gene, ε2, ε3, and ε4, have been identified and encode different isoforms of the APOE protein [9,10]. The polymorphism of these alleles results in the production of six APOE genotypes, namely, the homozygous ε2/ε2, ε3/ε3, and ε4/ε4 genotypes and the heterozygous ε2/ε3, ε3/ε4, and ε2/ε4 genotypes [11]. Notably, the combination of two nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs429358 and rs7412) in the fourth exon of the APOE gene leads to variations in the amino acids at positions 112 and 158 of the APOE protein [12,13]. Historically, the ε4 allele is considered the oldest form, evolving into the ε3 and ε2 alleles approximately 200,000 years ago. In modern populations, the APOE ε3 allele is the most prevalent, particularly in Asia, where it is found in up to 85% of the population, and in Africa, where this percentage reaches 69% [14]. The prevalence of the APOE ε4 allele exhibits substantial regional variability, ranging from less than 10% in Southern Europe and South China to as high as 40% among Central African populations and 37% in Oceania, with a discernible increase toward northern latitudes [15]. APOE ε2 is the rarest allele, with a global frequency of approximately 7.3% [16]. It is most common in East/West Africa, for example, in 38% of the population of Burkina Faso and 31% of the population of Togo [17].

The APOE protein is one of the five major plasma apolipoproteins and exists in three different isoforms: APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4. This protein consists of two key structural domains connected by a flexible hinge region [16]. The N-terminal domain (comprising residues 1 to 167) contains a receptor-binding region and four α-helices [18], whereas the C-terminal domain (comprising residues 206 to 299) contains a lipid-binding region and three α-helices [19]. The three main isoforms of APOE are highly similar in amino acid sequence but differ in single amino acid substitutions at several critical sites. APOE4 has two arginines at positions 112 and 158; APOE3 has a cysteine (Cys) at position 112; and APOE2 has a Cys at both positions [20]. The difference in amino acids at positions 112 and 158 in APOE4 affects its molecular conformation, resulting in significant differences in its neurobiological activity with that of APOE2 and APOE3 [21]. The distinctions among the APOE isoforms and their associations with CAA are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Isoform-specific amino acid differences and allele frequencies of APOE genotypes.

| Gene expression level | Isoform-specific amino acid difference |

Allele frequency (%) |

Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 112 | 158 | General | CAA | ||

| APOE2 | Cys | Cys | 22 | 2 | [22] |

| APOE3 | Cys | Arg | 85 | 67 | [23] |

| APOE4 | Arg | Arg | 13 | 34 | [24] |

Abbreviations: CAA: Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; Cys: Cysteine; Arg: Arginine.

APOE isoforms influence various brain cell functions, including the morphology and integrity of synapses, the deposition of Aβ, and the functionality of neurovascular units such as the BBB. Studies have shown that patients who are carriers or expressers of the APOE4 gene exhibit increased densities of dendritic filopodia with structural alterations in the spines [25]. Compared with APOE3 knock-in mice, APOE4 knock-in mice exhibit reductions in dendritic length and branching, as well as a reduced spine density in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, leading to impaired spatial learning and memory abilities [26]. Notably, changes in the dendritic length and spine density in APOE ε4 mouse models can also be traced back to their younger life stages [27]. Additionally, APOE isoforms have been shown to impact Aβ aggregation according to an analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) biomarkers in a cohort of cognitively normal individuals, and APOE4 promotes the formation of Aβ protofibrils more effectively than APOE2 and APOE3 in a β-amyloidosis mouse model [28]. However, numerous studies on transgenic mice with familial AD have shown that either increasing or decreasing the expression or lipidation level of APOE4 can reduce Aβ deposition [29], suggesting that other factors may be involved in the APOE-regulated process of Aβ deposition.

In addition, APOE isoforms are also associated with neurovascular dysfunction and the loss of BBB integrity in the pathogenesis of cognitive disorders [30]. A multifaceted role of APOE4 in altering neurovascular function, such as reductions in vascular density and resting cerebral perfusion without altering blood pressure, was observed in APOE4-targeted replacement mice. Compared with APOE3-targeted replacement or wild-type mice, APOE4 mice presented damage to neurovascular coupling, endothelial cell-induced microvascular responses, white matter integrity, and cognitive function [31]. A multiomic analysis of APOE4 knock-in mice revealed early disruption of the transcriptome, affecting signaling networks related to BBB integrity and ultimately leading to behavioral changes [32]. Other factors, such as an individual’s diet, physiology, and sex, may also interact with APOE4, influencing BBB function and causing changes in cognitive performance in animal models [33].

3. CAA pathology: from Aβ deposition to vascular damage

3.1. Molecular mechanisms: production, deposition, and clearance of Aβ and their impacts

Aβ is generated through the processing of transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β-secretase and γ-secretase, which produces Aβ peptides (36 to 43 amino acids), among which Aβ40 and Aβ42 are the most common types in the brains of CAA patients [34]. APP is a highly conserved type I transmembrane protein that is widely expressed in various tissues and has high homology across both mammalian and invertebrate species, indicating its essential physiological function [35]. Furthermore, genetic knockout of APP family members in mice leads to perinatal lethality and neurological deficits, further underscoring the importance of its functions [36].

Specifically, the nonamyloidogenic pathway is the predominant metabolic route for APP [37]. In this pathway, APP is first cleaved by α-secretase specifically at the Leu site to produce N-terminal soluble APP and the transmembrane C-terminal fragment α/C83, the latter of which is further cleaved by γ-secretase to produce the noncytotoxic P3 fragment and APP intracellular domain [38]. β-Site APP cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE1, also known as β-secretase) and its homolog BACE2 (also referred to as θ-secretase) participate in the nonamyloidogenic metabolism of APP [39]. With respect to the amyloidogenic pathway, studies have shown that BACE1 primarily cleaves APP at the Glu11 position, producing a C89 fragment, which is then cleaved by γ-secretase to generate truncated Aβ. BACE2 cleaves APP at the Phe20 site, resulting in a C80 fragment that further inhibits the production of Aβ [40,41]. The balance between these two APP metabolic pathways is crucial for maintaining Aβ homeostasis, which in turn helps prevent the toxic aggregation and misfolding of Aβ.

Like other brain metabolic products, the clearance of Aβ relies on multiple pathways, including enzymatic degradation [42], interactions with cell surface receptors and transport proteins [43], intramural periarterial drainage (IPAD), and glymphatic system drainage [44–46]. Each of these aspects plays a crucial role in maintaining Aβ homeostasis and preventing its accumulation in the brain, in turn preventing the emergence of pathological conditions such as CAA and AD.

The primary detrimental effects of Aβ on brain tissue include neuroinflammation and toxicity. Neuroinflammation is a chronic inflammatory phenomenon within the CNS that is characterized by the production of a large amount of proinflammatory factors by activated microglia and astrocytes [47]. Aβ shares structural similarities with antimicrobial peptides and the fusion domains of viruses, both of which can trigger glial cells to release a significant amount of proinflammatory factors [48], leading to neuroinflammation. Simultaneously, the overproduction of proinflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and interferon-gamma can affect the processing of APP within astrocytes, increasing the generation and toxicity of Aβ [49] and thereby exacerbating inflammation. Aβ aggregates can exert toxic effects on the nervous system through multiple pathways. They induce the formation of pores on cell membranes, promote various signals that activate glial cells [50], and can interact with glutamate neurotransmission, hindering the plasticity of excitatory synapses, where Aβ oligomers can alter the synaptic structure and density and subsequently impair synaptic plasticity and cause cognitive decline. Moreover, associated with Ca2+, its influx typically facilitates long-term potentiation (LTP) through the enhancement of postsynaptic neuronal synapses, which is a critical mechanism for learning and memory [51,52]. Under abnormal conditions, Aβ aggregates disrupt membrane integrity by forming channels, resulting in abnormally excessive Ca2+ influx that can perturb intracellular signaling, culminating in the inhibition of LTP and neuronal death [53,54]. These findings suggest that while Ca2+ supports LTP under normal physiological conditions, its increased influx in the presence of Aβ aggregates under pathological conditions may lead to detrimental outcomes. These findings further highlight the complex role of Aβ in the neuropathological processes of CAA and AD.

3.2. Pathophysiology: vascular damage in individuals with CAA and its consequences

Pathology studies have revealed extensive abnormalities in the histology [55] and ultrastructure [56] of the vascular wall in patients with CAA, in which smooth muscle cells in the vascular walls gradually diminish and are replaced by amyloid plaques. To date, seven types of amyloid proteins have been identified in CAA, including Aβ, cystatin C, prion protein, Abri/Adan, transthyretin, gelsolin, and immunoglobulin light chain amyloid protein. Among these, the accumulation of Aβ is the primary pathological feature of CAA; the protein is predominantly deposited in the small arteries and capillaries of the cerebral cortex and leptomeninges, with Aβ40 being the most frequently observed in the vascular walls of CAA patients [57]. Immunoelectron microscopy studies have shown that amyloid fibrils accumulate mainly within the outer basement membranes (BMs) of vessels in the early stages of CAA [58]. As the disease progresses, the degeneration of medial smooth muscle cells and the accumulation of many amyloid fibrils lead to cerebral vascular dysfunction. When CAA pathology progresses in severity, it typically presents with a variety of vascular pathologies, such as the duplication of vessel structures (forming a ‘double-barrel’ lumen), occlusive intimal changes, hyalinosis, microaneurysmal dilation, and fibrinoid necrosis [59,60].

The two main complications of CAA include cerebral hemorrhage and cerebral infarction. Cerebral microbleeds (CMBs) associated with CAA are typically caused by the rupture of blood vessels due to the deposition of amyloid proteins within vessel walls [61,62]. Similarly, cortical superficial siderosis (cSS) has also been identified as a specific biomarker for CAA [63], reflecting the widespread rupture of amyloid-rich cortical and leptomeningeal vessels. In the context of cerebral infarction, cerebral microinfarcts are characterized by high signal abnormalities on high-resolution T2-weighted images and are located in cortical areas with a maximum size of up to 5 millimeters [64], which may be caused by CAA-related cerebral hypoperfusion or occlusive small vessel disease.

4. APOE and CAA: genetic roles and clinical impact

4.1. Correlations between APOE genotypes and CAA

APOE primarily exists in the form of complexes with other lipoproteins in the plasma and CSF. Extensive in vitro and animal experiments have shown that APOE can facilitate the transition of Aβ from a nontoxic, monomeric state to a toxic form comprising oligomers and protofibrils, with the impact varying among the different APOE isoforms. The order of influence on this process is APOE4 > APOE3 > APOE2 [65]; specifically, APOE4 is detrimental to Aβ metabolism, APOE3 is neutral, and APOE2 is protective [66]. Bales and colleagues reported isoform-dependent differences in Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortex between mice with different APOE genotypes, with a significantly greater brain Aβ burden in PDAPP/TRE4 mice (i.e. those with the human APOE ε4 genotype) than in PDAPP/TRE3 and PDAPP/TRE2 mice [65].

Consistent with the conclusions mentioned above, several studies have indicated that APOE4 is associated with the risk of sporadic CAA and related cerebral hemorrhages, with the pathological severity of the disease being APOE4 dependent [65]. Similarly, patients with advanced CAA pathology (48%) were found to have a frequency of the APOE ε4 allele that was six times greater than that of patients with mild CAA pathology [22]. Other experiments have revealed that the severity of CAA pathology is greater in individuals with the ε4/ε4 genotype than in individuals with other APOE genotypes [67]. Thus, different APOE genotypes lead to varying degrees of CAA risk and severity, with patients carrying the APOE4 genotype (in particular APOE4 homozygous carriers) at the highest risk and experiencing the greatest disease severity.

Although the majority of experimental results suggest that the APOE ε4 genotype is a primary risk factor for CAA, interestingly, different genotypes may be associated with different types of CAAs as risk factors. Sporadic CAA often presents in mixed Congo Red angiopathy (CA) (characterized by amyloid protein deposition accompanied by other vascular pathologies), where APOE ε4 is identified as a risk factor for this type, in which Aβ is deposited in the walls of medium and small vessels of the meninges and cortex, as well as in the cortical capillaries. In contrast, in the pure CA (characterized by isolated amyloid protein deposition in blood vessels) form of CAA, APOE ε2 is considered a risk factor, in which Aβ deposition is restricted to the walls of medium and small vessels in the meninges and cortex without affecting cortical capillaries [68,69].

Different APOE isoforms can impact Aβ and related cellular structures in various ways, particularly due to differences in the mechanism of action between APOE4 and the other two types of APOE, which in turn indirectly trigger CAA. First, due to its 20-fold lower affinity for Aβ peptides than APOE3, APOE4 has a reduced capacity to clear Aβ, facilitating Aβ deposition. The deposited Aβ then transforms into neurotoxic substances or produces many free radicals, causing endothelial damage and leading to CAA [70]. Second, APOE4 cannot form stable complexes with microtubule-associated protein 2 and tau protein to stabilize the cellular scaffold structure like APOE3 [16, 71]; APOE4 is associated with dysfunctions in neurons, glial cells, and cerebral vascular endothelial cells, which may contribute to the deposition of Aβ and cerebral hemorrhage in patients with CAA, although this mechanism requires further validation. Third, APOE4 has weaker antioxidant capabilities than APOE3 does, thus providing poorer protection to neurons against oxidative stress, suggesting that brains with the APOE4 genotype are more susceptible to damage and a range of neurological disorders, including CAA. Fourth, compared with other isoforms, APOE4 may more effectively guide Aβ to pathological interactions with human brain pericytes (HBPs) and subsequently damage HBPs, further affecting the production of the APOE protein and the clearance of Aβ to some extent, thereby inducing CAA. Fifth, Arg-112 in APOE4 alters the nature of the lipid-binding domain, shifting the lipid-binding preference from high-density lipoproteins to very low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) [72] and causing other functional changes. These variants play key roles in various diseases, particularly atherosclerosis. Research indicates that individuals with the ε4/ε4 genotype are at increased risk of conditions such as extracranial atherosclerosis [73] and cerebrovascular and neurodegenerative disorders, including AD and CAA [74]. Several studies have indicated that carriers of APOE ε4 are more likely to have CAA and an increased severity [75,76], as well as a greater risk of early hemorrhagic episodes [77].

In addition, the APOE genotype has been strongly correlated with amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) in AD patients receiving Aβ clearance immunotherapy, likely because of its effect on the transport of Aβ to the cerebrovascular system [78–80]. Specifically, APOE ɛ4 homozygotes have the highest risk of developing ARIA following passive Aβ immunotherapy [81]. Clinical trials of the FDA-approved drugs lecanemab and donanemab have revealed that APOE ɛ4 homozygotes receiving passive Aβ immunotherapy presented a much higher incidence of ARIA-edema/effusion and ARIA-hemosiderosis/microhemorrhages than APOE ɛ4 heterozygotes and noncarriers [82,83]. Moreover, more severe CAA was also observed in APOE ɛ4 carriers than in noncarriers during active immunotherapy with the Aβ42 vaccine in AD patients [78]. Multiple findings indicate that ARIA is associated with vascular Aβ deposition and the pathogenesis of CAA. Three potential mechanisms by which APOE ɛ4 increases ARIA risk have been proposed: (1) its impact on the integrity of the neurovascular unit through various pathways [30, 84–87], (2) its well-established role in immune dysregulation [88–91], and (3) vascular damage caused by the mobility of APOE–Aβ complexes [80].

On the other hand, Wilhelmus et al. proposed that different APOE genotypes may also influence Aβ clearance by affecting the levels of APOE production [92]. This finding was supported by the observation that APOE ε4 carriers had lower plasma APOE levels than carriers of the other two genotypes did, whereas APOE ε2 carriers had higher plasma APOE and LDL-related APOE levels than APOE ε4 carriers did [93]. Another study also showed that adding purified APOE reduced cultured HBP death and promoted Aβ clearance [94], suggesting that the genotype influences Aβ clearance efficiency by affecting APOE protein expression levels.

4.2. Mechanisms of CAA mediated by APOE through Aβ

The deposition of Aβ is closely related to its production, aggregation, uptake, and clearance processes; APOE can influence these processes, thereby regulating the deposition of Aβ and mediating the induction of CAA (Figure 1).

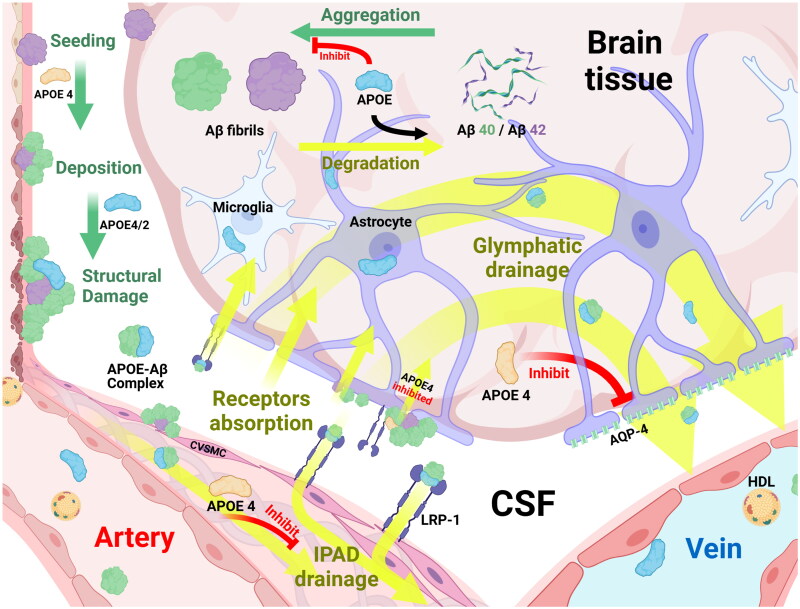

Figure 1.

Mechanisms underlying Aβ fibril formation, aggregation, and APOE-mediated clearance in cerebral amyloid pathology.

Aβ protein precursors generated in brain tissues polymerize to form Aβ, a process influenced by APOE. Aβ42 was the first peptide to be ‘seeded’ in brain tissues and blood vessel walls. Under the effects of APOE, Aβ40 aggregation and deposition processes are completed; Aβ40 gradually replaces Aβ42, ultimately causing structural damage to tissues.

In the process of clearing Aβ, soluble Aβ can be directly degraded by extracellular proteases with the aid of APOE. In addition, Aβ can also form complexes with APOE and be cleared through the following pathways: (1) Through the perivascular and glial lymphatic system, which is composed of the brain interstitial space, astrocytes and microglia, Aβ is transported from the arterial side to the venous side and finally drained into venous blood vessels for clearance; this process is suppressed by APOE ε4. (2) Aβ is cleared through the drainage function of the IPAD pathway; the APOE ε4 genotype slows this clearance process, while APOE also participates in the drainage of nonfibrillar Aβ. (3) With the assistance of APOE, the complexes are absorbed by astrocytes and microglia through cell surface recognition receptors such as LRP-1 or are cleared into blood vessels and their anastomoses, which is jointly promoted by APOE and HDL. The clearance of APOE4–Aβ complexes is the slowest among the APOE subtypes.

Abbreviations: Aβ: Amyloid β; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; AQP-4: Aquaporin-4; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; CVSMCs: Cerebral Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein; IPAD: Intramedullary Periarterial Drainage; LRP-1: Low-density lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein-1

Different APOE genotypes have different impacts on the isoforms of Aβ. Toxic Aβ primarily consists of Aβ40 and Aβ42, and the type of deposition and the ratios of these peptides significantly influence the disease type and severity. Both Aβ types are associated with CAA, and studies have shown that Aβ42 mainly forms the basis of brain parenchymal plaques and CAA, while Aβ40 also plays an important role in the absorption of Aβ42. As a result, a higher Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio in cerebral vessels is largely associated with the formation of CAA [95–97]. In terms of the characteristics of different Aβ types, Aβ42 is more influenced by HDL and APOE than is Aβ40, meaning that Aβ40 is less easily transported and cleared by lipoprotein-mediated transvascular pathways and is thus more likely to accumulate in vessels [66]. In vitro experiments revealed that Aβ42 is taken up faster than Aβ40 by cerebral vascular smooth muscle cells (CVSMCs), causing earlier and more extensive cellular degeneration [98]. A significant negative correlation between soluble APOE and Aβ42 levels has been observed in the hippocampal homogenates of PDAPP/TRE2 (APOE ε2 genotype) mice, suggesting that higher APOE levels are conducive to reducing Aβ42 levels; however, this significant correlation was not observed in hippocampal extracts from PDAPP/TRE3 or PDAPP/TRE4 mice [65]. Subsequent studies have shown that recombinant APOE ε2 promotes greater Aβ42 clearance than does recombinant APOE ε4 [66]. Thus, due to reduced APOE expression or functionality, the APOE ε4 genotype impairs the APOE-dependent clearance of brain-derived Aβ. Since Aβ42 clearance is more sensitive to APOE regulation, this impairment results in an early and sustained increase in soluble Aβ42 levels and an age-dependent increase in the brain Aβ burden [65], thereby mediating the occurrence of CAA.

APOE can influence the aggregation of Aβ by affecting its production and maturation processes from the outset, which serves as an important trigger of CAA. Abnormal aggregation of Aβ is more likely to induce CAA, making the maintenance of this process in its normal state crucial. Currently, the predominant view is that the involvement of APOE and Aβ in the seeding hypothesis represents the main mechanism through which Aβ aggregates and induces CAA. In this hypothesis, the formation of CAA can be outlined in three steps [99]: (1) initially, under the influence of APOE4, Aβ42 acts as a ‘seed’ that is planted in the vessel walls and brain parenchyma; (2) subsequently, Aβ40 begins to deposit onto the vessel walls, again influenced by APOE4, with amounts gradually surpassing those of Aβ42, leading to the maturation and aggregation of Aβ, with amyloid material starting to replace the normal vessel walls; and (3) finally, through the involvement of APOE4 or APOE2 and the action of Aβ, a series of pathological changes occur in the vessel walls, culminating in rupture and hemorrhage and thereby inducing CAA-associated neuroimaging lesions and clinical manifestations. This hypothesis also corroborates the earlier conclusion that APOE has stronger effects on combining Aβ42 than Aβ40, suggesting that Aβ40 is more likely to precipitate and a greater impact of a higher Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio on CAA formation.

The nucleation-dependent polymerization model confirmed that APOE and clusterin (CLU), which is a secretory protein mostly synthesized in astrocytes in the brain that is highly inducible in neurons by AD risk factors [100], can inhibit the early stages of Aβ aggregation and the seeding aggregation of Aβ protofibrils [101,102]. The order of this interaction between APOE and Aβ protofibrils is APOE2 = APOE3 > APOE4 [103], with evidence showing that APOE3 delays the onset of Aβ protofibril growth kinetics in a concentration-dependent manner, thus inhibiting early Aβ aggregation [104]. Additionally, APOE and CLU inhibit the early, continuous aggregation of Aβ into protofibrils by interacting with Aβ nuclei/oligomers formed on matrix-coated beads [105]. Other studies have shown that APOE can inhibit the in vitro growth of Aβ by binding and sequestering Aβ monomers [106]. Based on the conclusions above, we speculate that the ability of APOE4 to restrain Aβ aggregation may be weaker than that of the other two subtypes, leading to the overprecipitation of Aβ in APOE ε4 carriers and the subsequent induction of CAA.

The clearance of Aβ from the brain is a key process in maintaining cognitive function [67]. A decrease in the efficiency of Aβ clearance is likely to directly induce CAA. This process is mainly divided into two parts for discussion: cellular and receptor-mediated mechanisms and Aβ clearance pathways.

One mechanism for clearing Aβ from the brain involves its binding to APOE, followed by uptake by astrocytes and microglia [107]. High levels of APOE may facilitate Aβ clearance through members of the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor family and associated proteins, such as LRP1 [108,109]. Shibata [110] and Wilhelmus [111] confirmed that LRP1 is a primary receptor for the uptake and clearance of Aβ, participating in the absorption and clearance of the APOE–Aβ complex by astrocytes [112] and CVSMCs [98]. The clearance of the APOE4–Aβ complex is the slowest, primarily because the transfer of this complex is mediated by the LRP1 receptor and it is cleared by very LDL transfer at a slower rate than other isoforms, leading to impaired clearance of Aβ [113]. Experiments by Robert et al. also showed that APOE on the vascular side of the brain works in conjunction with HDL in the blood to clear Aβ in the brain by transporting it into the bloodstream [66]. Furthermore, an increase in APOE levels can enhance the extracellular proteolytic degradation of soluble Aβ, which involves Aβ-degrading enzymes such as neprilysin, insulin-degrading enzymes (IDEs), angiotensin-converting enzymes, and metalloproteinases [114,115], thereby reducing the cell surface content of Aβ and preventing Aβ-mediated cell death [42].

Several studies have shown that CVSMCs can internalize and phagocytose Aβ [108, 111, 116]. These cells play crucial roles in maintaining vascular wall integrity, regulating cerebral blood flow [117], and facilitating the perivascular drainage of Aβ in the interstitial fluid [118,119]. Research has confirmed the cytotoxic effects of Aβ on CVSMCs, with Aβ42 disrupting the cytoskeleton, inducing morphological changes, increasing cell death, and reducing the ability of Aβ to be internalized. Consequently, as Aβ accumulates, impaired CVSMC function may lead to microaneurysm formation, the leakage of fibrinogen and other potential neurotoxic blood components, and the formation or rupture of vascular thrombi [120,121], thereby causing cerebrovascular diseases such as CAA. Since certain APOE isoforms might play a significant role in the mechanism of Aβ deposition, the interaction between APOE and the process underlying the cytotoxic effects of Aβ on CVSMCs need to be elucidated in future studies.

Moreover, Aβ clearance pathways, such as IPAD and glymphatic drainage, play crucial roles in the elimination of Aβ. Carare and colleagues proposed the IPAD pathway [44, 46, 118], in which the primary route involves the drainage of brain interstitial fluid and solutes along the BMs of the walls of cerebral capillaries and leptomeningeal arteries into the cervical lymph nodes rather than through traditional lymphatic vessels. Research has indicated that Aβ is primarily removed from the brain parenchyma via this route [44, 46, 122], and mouse experiments have shown that APOE participates in the clearance of nonfibrillar Aβ through this IPAD pathway [107]. As arteries age or as the quantity and functionality of APOE decrease, the efficiency of perivascular drainage decreases, leading to elevated levels and the subsequent deposition of Aβ and ultimately the induction of CAA [107, 123]. Studies have shown that transgenic mice overexpressing APOE ε4 exhibit a disrupted pattern of Aβ clearance via the IPAD pathway, whereas overexpression of the other two genotypes does not have this effect [124].

Interestingly, astrocytes also have a vital connection with CAA formation since they can influence the aggregation of Aβ in different ways. APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes produce BMs that facilitates Aβ aggregation [125]. Additionally, APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes secrete reduced amounts of laminin, thereby affecting the properties of the pial–glial BMs [126], which serves as a bidirectional conduit for the entrance and exit of CSF into the brain. Consequently, the influence of this genotype may disrupt the balance between CSF and interstitial fluid exchange, indirectly affecting the clearance of Aβ [44, 46, 127]. Furthermore, the ability of APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes to maintain the integrity of the BBB is diminished [128]. This genotype activates the ceramide A–NFκB–metalloproteinase-9 pathway, leading to compromised BBB integrity [129] and thereby disrupting the IPAD pathway for Aβ clearance. Moreover, APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes exhibit low synthesis of type IV collagen, one of the components responsible for the integrity of vascular walls and BMs [130]. Consequently, APOE ε4 tends to make vessels fragile and affects BMs functions, leading to slowed drainage through the IPAD pathway and clearance of Aβ, thus promoting CAA pathology [130]; however, these effects have rarely been observed with APOE ε2 and ε3.

Another Aβ drainage pathway involves the glymphatic system, which is composed of water channels formed by aquaporin-4 (AQP4) on astrocytes and has been extensively studied in recent years. This system plays a crucial role in clearing metabolic waste from the CNS and is regulated by many physiological factors, such as sleep, circadian rhythms, and arterial pulsation [131–133]. Animal studies have shown that AQP4-dependent lymphatic channels are important for facilitating the clearance of soluble Aβ from CSF and extracellular fluid. Compared with wild-type mice, the rate of Aβ clearance in astrocytes in mice lacking AQP4 was reduced by 55–65% [45, 134]. Research has indicated that lymphatic drainage plays a crucial role in the macroscopic transfer of APOE produced in the choroid plexus to the brain. CSF-derived APOE is rapidly transported to the brain in a subtype-specific manner (APOE2 > APOE3 > APOE4), and the distribution of APOE within the brain parenchyma is facilitated by AQP4 [135]. Although few studies have investigated whether APOE plays a vital role in the clearance of Aβ through the glymphatic system described above, we hypothesize that AQP4 influences the amount and distribution of APOE in the brain parenchyma, thus affecting Aβ clearance.

Furthermore, both astrocytes and microglia contribute to the production and release of APOE. Astrocytes produce APOE and lipoproteins extracellularly [136], and microglia express and release APOE [137]. Extensive experimental data suggest that APOE is primarily secreted by astrocytes in the brain [138,139] and serves as the main lipid carrier within the CNS [140]. Interestingly, the amount of APOE produced by astrocytes cultured in vitro is only 3–10% of that produced by HBPs, and HBPs carrying the APOE ε4 allele produce three times less APOE than those without the allele. Additionally, APOE produced by pericytes, rather than astrocytes, primarily regulates the cytotoxicity and clearance of Aβ near brain vessels [141]. These experimental results significantly contradict the widely accepted conclusion that APOE is produced mainly by astrocytes, yet some scholars propose that this discrepancy might be due to the richer diversity and greater quantity of astrocyte types in the human brain, increasing the importance of APOE production at the macroscopic level. Additionally, the conditions of in vitro cultures might not perfectly reflect true physiology, as cultures lack neighboring cells that secrete potential factors regulating APOE expression [142,143]. Therefore, the source of APOE produced in the human brain warrants further verification via novel techniques, such as the use of an encephaloid model to mimic real in vivo conditions.

Astrocytes with different APOE genotypes exhibit varying levels of Aβ clearance via effects on the IPAD pathway and other Aβ uptake mechanisms. As mentioned earlier regarding Aβ clearance pathways, APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes produce less laminin and type IV collagen, impairing the function of the BMs and BBB, promoting Aβ aggregation and inhibiting its clearance [6]. Additionally, in vitro, adult astrocytes bind and internalize Aβ, participating in Aβ deposition and clearance, similar to other perivascular cells, such as HBPs, and mediate the occurrence of CAA; these processes are potentially influenced by APOE [144]. The role of APOE in this process may be twofold. First, APOE might influence the Aβ-mediated degeneration of HBPs and astrocytes in a concentration-dependent manner, possibly by preventing the formation of cell surface aggregates to maintain Aβ solubility [141] and thereby facilitate its uptake and internalization. Furthermore, early research revealed that APOE enhances the recognition of soluble Aβ by LRP1 [145], promoting astrocyte uptake and the internalization of Aβ. Other studies have indicated that the lysosomal degradation capacity of Aβ in APOE ε4-expressing astrocytes is reduced relative to that of astrocytes expressing other genotypes, decreasing the efficiency of Aβ clearance.

In addition to the function of astrocytes, microglia are also closely connected with Aβ precipitation. Indeed, in addition to the role of APOE-mediated Aβ in the development of CAA, microglia expressing different APOE subtypes may also cause CAA due to their different functions, affecting the expression of APOE and related cascades. Research has revealed a diminished phagocytic effect on Aβ in APOE ε4-expressing microglia [146], and cell-derived APOE can be deposited within amyloid plaques, further contributing to plaque formation [147]. Other studies have shown that high expression of APOE4 in microglia can induce the production of numerous cytokines, trigger the rearrangement of microglial inflammation-related genes, and activate inflammation-related signaling pathways, resulting in proinflammatory responses and ultimately leading to inflammatory damage [137]. Other studies have shown that APOE4-expressing microglia have a poorer lipid uptake ability, and the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets also signifies functional impairments and inflammatory responses in the aging brain, adversely affecting neuronal activity and network coordination [137].

In summary, the APOE genotype directly influences the onset of CAA by regulating the production, aggregation, and deposition of Aβ. APOE4 exacerbates neurovascular dysfunction and the loss of BBB integrity by mediating the templated aggregation of mature Aβ through effects on the Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio, thereby aggravating CAA formation. Concurrently, APOE4 hinders the effective clearance of Aβ, particularly by slowing the clearance rate of APOE4–Aβ complexes and affecting the cellular uptake and processing of Aβ, leading to its accumulation in the brain. Moreover, the expression of APOE ε4 alters the functionality of astrocytes and microglia, impacting their abilities to process Aβ and indirectly promoting CAA formation by affecting Aβ clearance pathways such as the IPAD and glymphatic systems. These mechanisms collectively elucidate how the APOE genotype plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of CAA, with APOE4 being especially critical in facilitating CAA formation.

4.3. APOE-mediated cognitive decline in CAA patients

Cerebrovascular injury caused by CAA, such as cerebral hemorrhage and cerebral infarction, can result in subsequent cognitive impairment [148–151]. In addition, CAA patients often experience transient focal neurological episodes that are likely related to bleeding (especially superficial cortical siderosis or focal convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage), which can induce transient ischemic attacks, migraine with aura, focal epileptic seizures, syncope, changes in mental status, hallucinations, and functional neurological disorders [118, 152].

Moreover, neuropathological studies have shown a very high prevalence of overlap between sporadic CAA and AD [153,154]. A recent autopsy study revealed that, 96.3% of AD patients presented with copathology of CAA, and these patients presented more severe CAA in cortical and leptomeningeal vessels than patients with other neurodegenerative diseases, such as dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease dementia [155], suggesting a strong correlation between CAA and AD. CAA involves the accumulation of Aβ within the cerebral vasculature [95–97, 156–159], whereas AD is characterized by the accumulation of Aβ in plaques within the brain parenchyma [160,161]. For a detailed comparison of CAA and AD, refer to Table 2 [162,163].

Table 2.

Overview of the clinical profiles of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy.

| Overview | AD | CAA | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical initial symptom | Memory decline | Intracranial hemorrhage | [162] |

| Characteristic imaging findings | Hippocampal atrophy | Hemorrhage; cSS | [162] |

| Cerebral Aβ pathology findings | Extracellular Aβ deposits | Aβ deposition in the walls of cerebral arteries and arterioles | [160] |

| CSF Aβ38, pg/ml (AD vs. CAA vs. controls) | |||

| 1490 vs. 2740 vs. 2840ac | [164] | ||

| CSF Aβ40, pg/ml (AD vs. CAA vs. controls) | |||

| 6470 vs. 3150 vs. 6890ac | [164] | ||

| 3713 vs. 2912 vs. 4003ac | [163]d | ||

| CSF Aβ42, pg/ml (AD vs. CAA vs. controls) | |||

| 323 vs. 115 vs. 520abc | [164] | ||

| 433 vs. 355 vs. 838ac | [163] | ||

| 336 vs. 398 vs. 1030 | [165]e | ||

| CSF p-tau181, pg/ml (AD vs. CAA vs. controls) | |||

| 92.8 vs. 62.1 vs. 49.5ab | [164] | ||

| 110 vs. 66.3 vs. 47.9ac | [163] | ||

| 78 vs. 46 vs. 42 | [165] | ||

| CSF t-tau, pg/ml (AD vs. CAA vs. controls) | |||

| 657 vs. 316 vs. 250ab | [164] | ||

| 712 vs. 395 vs. 215ac | [163] | ||

| 600 vs. 391 vs. 365 | [165] | ||

| Amyloid PET uptake f | |||

| AD > CAA > controls | [166] | ||

p < 0.05, AD patients versus CAA patients.

p < 0.05, AD patients versus healthy controls.

p < 0.05, CAA patients versus healthy controls.

AD patients and controls were not statistically compared.

A statistical analysis was not conducted.

This conclusion is based on a meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: CAA: Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy; Aβ: Amyloid β; AD: Alzheimer’s Disease; cSS: cortical Superficial Siderosis; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; p-tau: phosphorylated tau181; t-tau: total tau.

Accordingly, in addition to direct neurovascular injury, the pathological processes of AD constitute another potential factor contributing to cognitive decline in CAA patients [167]. Compared with patients with nonamnestic cognitive impairment, CAA patients with an objective memory impairment (AD typical cognitive pattern) presented a smaller hippocampal volume and increased tau-PET binding in regions susceptible to AD-related neurodegeneration [154, 168]. However, a recent study did not observe any differences in overall cognition, specific cognitive domains, or the presence of neuropsychiatric symptoms between CAA patients with and without an AD-associated CSF biomarker profile [165]. In addition, a multivariate analysis controlling for AD pathology and other potential confounders revealed that individuals with moderate-to-severe CAA presented a slower perceptual speed and impaired episodic memory than subjects with no-to-minimal CAA, [153] suggestig that CAA-related cognitive impairment is not only influenced by AD pathology but also depends on its own pathological processes.

The APOE ε4 genotype may contribute to cognitive impairments by increasing the burden of oligomeric Aβ at synapses, leading to synaptic atrophy and neuronal loss in the brain. Additionally, due to the APOE ε4 genotype, damage to the BBB may facilitate the entry of neurotoxic plasma derivatives into the brain, contributing to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques [67]. Research has also shown that the presence of APOE4 hinders the neuronal response to Reelin. In the CNS, Reelin is a crucial extracellular matrix protein that regulates neuronal migration and positioning during brain development and is involved in modulating kinase and phosphatase activity to counteract Aβ toxicity. Studies have shown that an increase in Aβ levels significantly reduces learning and memory in mice with impaired Reelin function [169], suggesting that a reduction in Reelin function may aggravate the impact of Aβ on nerves. As a result, APOE4 may increase the risk of cognitive impairments in CAA patients by reducing the degree to which neurons respond to Reelin. Additionally, APOE4 may cause the dysfunction and eventual death of hippocampal neurons expressing γ-aminobutyric acid. Given that these interneurons have an inhibitory effect on hippocampal function and that the hippocampus plays a crucial role in cognition and memory processes [170], APOE4 can lead to excessive excitation of the entire hippocampal network, leading to cognitive impairments [171]. Experiments using mouse lines produced under the control of the neuron-specific synapsin-1 promoter [172], which expresses floxed human APOE3 or APOE4 genes [173] and the Cre recombinase gene, have been conducted to verify these results. Experiments have shown that PS19-fE4 mice (expressing human APOE4) exhibit significant overexcitability in the CA3-CA1 network compared with PS19-fE3 mice (expressing human APOE3). However, the elimination of neuronal APOE4 removed this overexcitability of the neuronal network [174]. The mechanisms described above explain how CAA is closely related to cognitive impairments. However, whether these mechanisms differ in their impacts on cognitive impairments in patients with CAA and AD, as well as the characteristic mechanisms unique to each disease and independent of the other, remain to be further studied.

5. Diagnosing CAA: strategies and standards

Currently, the definitive diagnosis of CAA is mainly based on postmortem examinations, which identify certain characteristic structures, such as distinctive acellular thickening in the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries (including arterioles) and, less frequently, veins, as well as vascular features affected by CAA and the presence of Aβ using special staining techniques [55].

For the clinical identification of living CAA patients, radiological criteria are often used to confirm the presence of hemorrhagic and ischemic lesions caused by CAA. The commonly used criteria include the Boston criteria [1, 175] and the Edinburgh criteria [176], which incorporate clinical, imaging, and pathological aspects to assess the occurrence of CAA [63, 177,178]. The Boston criteria 2.0 mainly rely on clinical and brain MRI data in addition to biopsy data for diagnosing CAA, briefly including an age of 50 years and older; presentation with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), transient neurological episodes, or cognitive impairment; and specific MRI features, such as ICH, CMBs, or foci of cSS or convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage, as well as severe perivascular spaces in the centrum semiovale or white matter hyperintensities in a multispot pattern [1]. In contrast, the Edinburgh criteria were proposed as an alternative, especially for patients with ICH who do not have MRI data available [176], and incorporate a multivariate predictive model for CAA-related lobar ICH, including the presence of the APOE ε4 allele, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and finger-like projections of the ICH.

The neuroradiological characteristics of CAA, which cover multiple key areas, play a crucial role in its diagnosis and assessment. The most common manifestation is lobar ICH, a type of nontraumatic bleeding that is predominantly located in the temporal and occipital lobes, where amyloid protein deposits are abundant [179,180]. In addition, convexal subarachnoid hemorrhage (cSAH) is another important indicator of CAA, often leading to transient focal neurological episodes [181,182]. Furthermore, CMBs manifest as small regions of chronic blood extravasation that can be detected through specific MR sequences, such as T2*-weighted gradient recalled echo; lobar CMBs are quite commonly observed in patients with CAA [62, 183,184]. Moreover, cSS involves the deposition of hemosiderin under the dura, which is often observed after cSAH. This manifestation of cSS occurs with a relatively high frequency in histologically confirmed cases of CAA and is associated with the early recurrence of lobar hemorrhages [185], but due to the insufficient number of samples, the use of cSS as a diagnostic sign of CAA is thus far unconvincing. Additionally, a specific pattern of WMH on T2-weighted MRI [186], especially in posterior brain regions, is characteristic of CAA [166]. The diagnosis of CAA can also be facilitated through PET imaging of Aβ with the use of florbetapir as a tracer to quantitatively measure Aβ deposition in the brain [187], as well as through an analysis of Aβ levels in the CSF. Compared with the levels in healthy controls, reduced levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 can be detected in the CSF of CAA patients who have cSS and convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage [188].

6. Treating CAA: current status and prospects

Currently, no cure is available for CAA. Existing treatment strategies mainly target reducing Aβ deposition via numerous techniques, including antibody-mediated clearance of aggregated and soluble Aβ, reducing Aβ production, and enhancing Aβ clearance efficiency through pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches. Table 3 summarizes some of the current research progress on approaches for the treatment of CAA described below.

Table 3.

Brief summary of current clinical trials of drugs for CAA.

| Treatment methods | Site of action | Mechanism of action | Drugs or molecules | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotherapies | ||||

| Lecanemab and donanemab immunotherapy | Aβ plaques | Slowing functional decline, removing Aβ plaques | Lecanemab, Donanemab | [83, 82] |

| Anti-human APOE antibody 4 (HAE-4) passive immunotherapy | Low-lipid form of human APOE-Aβ plaques | Binding to low-lipid APOE, diminishing Aβ plaques | HAE-4 | [189] |

| Peptide mimetic therapies | ||||

| Targeting the APOE receptor binding region | APOE receptor binding region | Inhibiting the interaction between APOE and its receptors | / | [190] |

| Mimicking HDL | APOE | Binding to APOE to enhance its function | / | [190] |

| Targeting amino acids 12–28 of APOE | APOE-Aβ interaction | Inhibiting the interaction between APOE and Aβ | / | [191] |

| Upregulating ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 | APOE | Altering the balance between lipidated and nonlipidated APOE | / | [191] |

| Decreasing APOE aggregation | APOE | Altering the balance between lipidated and nonlipidated APOE | / | [192] |

| Gene therapy | ||||

| CRISPR/Cas9 gene therapy | APOE ɛ4 allele | Converting APOE ɛ4 to APOE ɛ3 or APOE ɛ2 | / | [192] |

| Other APOE-targeted therapies | ||||

| LXR and RXR agonists (e.g. bexarotene) | APOE | Promoting APOE lipidation and expression | Bexarotene | [193] |

Abbreviations: CAA: Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; HAE-4: anti-Human APOE antibody 4; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein; LXR: Liver X Receptor; RXR: Retinoid X Receptor.

Although passive immunotherapies targeting various Aβ species have emerged as potential therapeutic strategies for AD [194,195], their ability to reduce the vascular Aβ burden has not been extensively studied. Aβ passive immunotherapy not only relieves CAA pathology but also improves vascular reactivity [196]. Long-term injection of ponezumab (an Aβ antibody) in transgenic mice with prominent CAA resulted in a significant reduction in Aβ accumulation in leptomeningeal and cerebral vessels, and vascular reactivity was restored following the acute administration of ponezumab.

However, a trial of anti-Aβ immunotherapy in CAA patients yielded negative results [197], raising doubts about the possibility of immunotherapy in CAA patients. Furthermore, neuropathological investigations have suggested that the removal of Aβ from severely affected vessels in patients with advanced CAA may render these vessels more prone to hemorrhage [198]. Despite the promising potential and significant advancements in Aβ-targeted immunotherapies, their adverse effects, such as hemorrhage and microbleeds, may greatly limit their development and trials in CAA patients. Since these adverse effects are mediated by the APOE genotype, further research is suggested to reveal the detailed mechanisms by which APOE affects Aβ clearance with and without immunotherapy.

Recent research has revealed that anti-human APOE antibody 4 (HAE-4) is capable of recognizing and binding to a low-lipid form of human APOE [189], which is exclusively present in Aβ plaques. Through passive immunotherapy targeting either mouse APOE or human APOE4, researchers were able to reduce the severity of Aβ pathology in mouse models of amyloidosis [199,200]. Furthermore, in mouse models with pronounced CAA, HAE-4 not only diminished the number of Aβ plaques in the brain tissue but also mitigated the symptoms of CAA [201]. Importantly, this approach does not lead to vascular complications; instead, it potentially preserves vascular integrity by restoring the function of certain cells within the neurovascular unit that are often impaired in CAA [202,203]. Given that the lipidation level of APOE is directly linked to the extent of Aβ pathology in the brain [5, 204,205], APOE with a low lipidation level could exert a toxic effect by facilitating Aβ plaque seeding or obstructing the clearance of Aβ from the CNS. Therefore, by targeting low-lipid APOE within the core of Aβ plaques, HAE-4 might recruit microglia to plaques, thereby degrading APOE. In conclusion, the therapeutic application of HAE-4 antibodies for CAA appears to be highly promising for future research.

Researchers have also proposed the use of peptide mimetics to modulate the function of APOE for treating CAA. One mechanism involves the use of peptide mimetics to competitively bind to the APOE receptor binding region (amino acids 130–150), inhibiting the interaction between APOE and its receptors and thereby suppressing its effect on microglial immunoreactivity [190, p. 2]. This approach has been shown to improve the survival rate in mouse models of traumatic brain injury [206,207] and may also mitigate the inflammatory response associated with CAA. Another mechanism suggests that these peptide mimetics can enhance the function of APOE; by designing peptides to mimic HDL and bind to APOE, the secretion of APOE and its lipidation status can be increased, offsetting the adverse effects on Aβ metabolism [208]. Additionally, peptide mimetics targeting amino acid residues 12–28 of APOE can inhibit the interaction between APOE and Aβ [191], effectively reducing the extent of Aβ pathology and synaptic loss in mouse models [209]. Blocking this interaction upstream of Aβ processing can significantly reduce Aβ levels and tau pathology, improving cognitive function. Although these mechanisms have been observed in AD mouse models, given the similarities in the pathological mechanisms of CAA and AD, a reasonable assumption is that this peptide mimetic treatment strategy may also be effective for CAA. However, the specific outcomes require further experimental investigation.

Gene therapy for APOE has emerged as another highly promising therapeutic strategy. Using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system, the APOE ɛ4 allele could be converted to APOE ɛ3 or APOE ɛ2, thereby ameliorating the CAA-inducing effects associated with APOE ɛ4. Research conducted on induced pluripotent stem-cell (iPSC)-derived neurons has shown that converting APOE ɛ4 to APOE ɛ3 through gene editing can reduce its cytotoxic effects [210]. Experiments in iPSC-derived organoids have shown that converting APOE ɛ4 to APOE ɛ3 may alleviate Aβ pathology by increasing the rate of Aβ clearance by astrocytes and microglia [146]. However, the application of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology for the treatment of CAA is still in its infancy and requires further investigation and exploration.

Because lipidated APOE is more effective at clearing Aβ than nonlipidated APOE, researchers have investigated whether treatment can be pursued by altering the balance between lipidated and nonlipidated APOE. Experiments have revealed that peptide mimetics capable of upregulating ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 [211] can increase the lipidation level of APOE4 in mouse models, reduce Aβ and tau levels, and alleviate cognitive deficits [189]. Similarly, peptide mimetics that decrease APOE aggregation can increase its capacity to accept lipids and improve symptoms [192]. Among these peptide mimetics, the liver X receptor (LXR) and retinoid X receptor (RXR) families can promote APOE lipidation and expression [212]. Oral administration of bexarotene, an LXR/RXR agonist and an FDA-approved anticancer agent, has been shown to increase the clearance of Aβ and improve cognitive function in animal models [193]. Additionally, the administration of choline (a soluble precursor of phospholipids) has been shown to restore defective lipid homeostasis in APOE4-iPSC-derived astrocytes1. These therapeutic strategies aimed at improving the lipidation levels of APOE are also based on experiments conducted using AD mouse models. Given that the pathogenesis of CAA is closely related to the lipidation level of APOE, these strategies could be applied to the treatment of CAA, although further validation is needed.

The unique structure of APOE4 facilitates interdomain interactions between the amino and carboxyl termini, resulting in a more compact structure than that in APOE2 and APOE3 and potentially leading to faster turnover and lower APOE plasma levels, thereby producing pathogenic effects [213]. Through Western blot analyses of human APOE ε3 and APOE ε4 in brain homogenates from knock-in mice, wild-type mice and Arg-61 APOE mice, researchers have revealed that the APOE level in Arg-61-expressing mice is lower than that in wild-type mice, whereas the APOE mRNA level is similar to or even slightly higher than that in wild-type mice, indicating that domain interactions result in lower APOE levels in the mouse brain [213]. Consequently, by employing phenothiazine derivatives to inhibit these interdomain interactions, the pathogenic effects of APOE4 can be attenuated.

Other potential methods for enhancing the rate of Aβ clearance without the involvement of APOE, including increase Aβ degradation, promoting its clearance by vascular receptors, optimizing perivascular drainage, and exploring new pharmacological interventions, have also been investigated as methods for treating CAA (Figure 2).

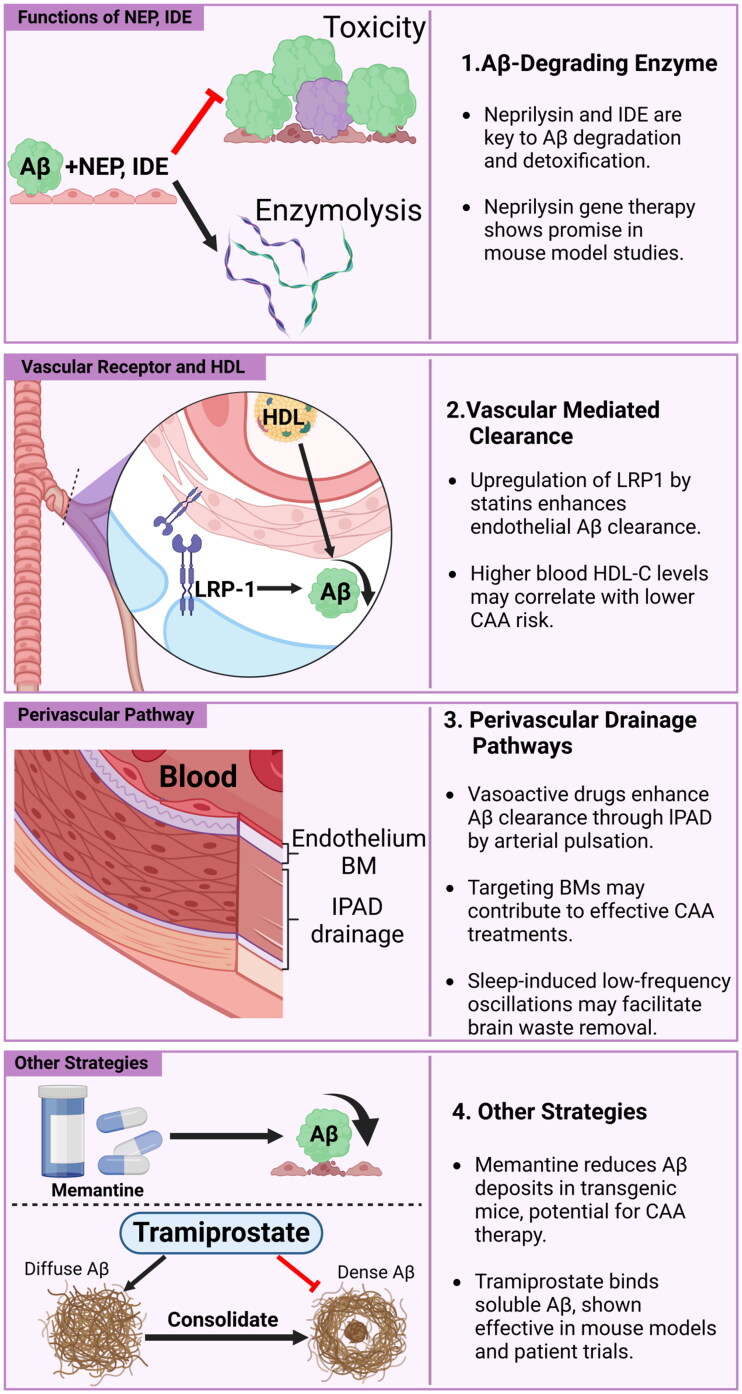

Figure 2.

Pathways for treating CAA by improving Aβ clearance.

Current research on Aβ clearance includes the following directions: (1) promoting the interference and decomposition functions of enzymes such as neprilysin and IDE to promote decomposition and weaken the toxic effects of Aβ; (2) using receptor antagonists such as simvastatin and lovastatin to regulate vascular receptors by upregulating the vascular receptor LRP-1 and other methods to promote the clearance of Aβ; (3) using vasoactive agents to activate blood vessels, enhance arterial pulsation, or target low-frequency oscillations in sleep or the vascular BMs to improve its drainage function, among others, to promote blood vessel-mediated Aβ clearance via peripheral pathways; and (4) using other strategies such as drugs that reduces Aβ deposits (e.g. Memantine) or bind soluble Aβ (e.g. tramiprostate) to promote Aβ clearance.

Abbreviations: CAA: Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy; Aβ: Amyloid β; APOE: Apolipoprotein E; BMs: Basement Membranes; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein; LRP-1: Low-density lipoprotein Receptor-related Protein-1; NEP: Neprylisin; IDE: Insulin-Degradation Enzyme; IPAD: Intramural Periarterial Drainage

Enzymes that degrade Aβ, such as neprilysin and IDEs, play crucial roles in clearing Aβ and reducing its cytotoxicity. Studies have shown that the levels of neprilysin in microvascular extracts from patients with CAA and AD are significantly reduced [214]. Therefore, gene therapy aimed at increasing the expression of neprilysin in the cerebrovascular system could be effective for CAA treatment, and experimental evidence has demonstrated the potential therapeutic efficacy of neprilysin in mouse models [215].

Vascular receptor-mediated Aβ clearance is also crucial. LRP1 is known to be involved in the clearance of Aβ in the brain. Kanekiyo and colleagues reported that conditional knockout of LRP1 in vascular smooth muscle cells in APP/PS1 mice increases cerebral vascular Aβ deposition [216,217]. Therefore, upregulating LRP1 is considered a potential therapeutic approach for CAA. Both simvastatin and lovastatin have been shown to upregulate the expression of LRP1 in endothelial cells [218], thereby increasing the transport and clearance of Aβ. Additionally, epidemiological studies have shown that high circulating HDL cholesterol levels may also help reduce the risk of CAA, suggesting that the increase in HDL levels is another potential treatment strategy [219].

The relationship between IPAD and Aβ clearance has been discussed in detail previously, with studies indicating that vasoactive drugs can promote Aβ clearance mediated by IPAD [46, 220]. The underlying principle is mainly the increase in the motive force generated by arterial pulsations to promote clearance. Furthermore, since IPAD involves the interaction between Aβ and BMs, research targeting BMs for therapy also contributes to CAA treatment [221]. Additionally, ongoing research suggests that vascular motility, characterized by spontaneous low-frequency oscillations of the cerebral arteries, may be another physiological mechanism for eliminating brain waste, including Aβ [222]. These low-frequency arteriole oscillations are particularly pronounced during slow-wave sleep and have been shown to be related to the dynamics of CSF flow in humans [223]. Therefore, enhancing vascular peristalsis through noninvasive sensory stimulation patterns or appropriate stimuli to promote healthy sleep is considered a potential treatment strategy for CAA patients.

Reducing the production of the intracranial metabolic waste Aβ is also a major challenge in the treatment of CAA. The production of Aβ can be prevented by blocking the cascade events that lead to Aβ deposition in vessels, primarily through the use of BACE inhibitors [224]. Additionally, the development of antisense oligonucleotides that target precursor proteins to intervene in the cascade reaction as a treatment strategy is ongoing, but effective results have yet to be achieved. Another therapeutic agent, taxifolin, is considered capable of blocking the formation of Aβ oligomers to maintain vascular integrity and prevent cognitive impairments in CAA model mice [225]. Furthermore, cilostazol, a known selective inhibitor of type 3 phosphodiesterase, is another promising drug capable of reducing Aβ40 deposition and improving cognitive impairments in CAA model mice [226]. Researchers have also explored therapies targeting Aβ clearance, proposing a low-molecular-weight drug, tramiprosate, which has shown effectiveness in binding to soluble Aβ and reducing Aβ concentrations in mouse models [227]. This drug also has promising potential for CAA treatment. Besides, Memantine, a known NMDAR antagonist, can reduce the number of vascular Aβ deposits and the quantity of hemosiderin deposits in an APP23 transgenic mouse model of CAA, showing promise for CAA treatment [228].

Regarding CAA-related ICH, studies have shown that treatment with minocycline can reduce the frequency of CMBs in CAA transgenic mice [229]. Furthermore, regarding the treatment of CAA-related cognitive impairments, as mentioned above, Reelin, a key extracellular matrix protein, can participate in modulating kinase and phosphatase activity to counteract the toxicity of Aβ. Therefore, improving the quantity and function of Reelin may be a promising research direction for delaying the onset and progression of CAA-related dementia. Additionally, clinical trials have shown that the use of perindopril to lower blood pressure can reduce the recurrence rate of CAA-related ICH by 77%, effectively relieving the symptoms of CAA through blood pressure control [230]. Recent research has shown that in CAA patients, macrophages produce migrasomes after they engulf Aβ, which then disrupts the integrity of the BBB, further aggravating the condition of CAA [231]. These migrasomes are induced by Aβ40 in macrophages and destroy the BBB through CD5 antigen-like-promoted complement-dependent cytotoxic effects on vascular endothelial cells. Thus, researchers have proposed targeted therapy based on migrasomes as a beneficial technique for slowing the progression of CAA, representing a highly promising research direction.

7. Conclusions

CAA results from the deposition of Aβ proteins, predominantly Aβ42 and Aβ40, within the cerebral vasculature, disrupting normal cerebrovascular function. This pathology is intricately linked to an imbalance between Aβ production and clearance mechanisms, which include enzymatic degradation and transport systems facilitating Aβ removal via the BBB and perivascular pathways. APOE4 is associated with increased Aβ deposition and neurotoxicity, exacerbating the onset risk and contributing to neurocognitive decline in CAA patients. In contrast, APOE2 can inhibit the deposition of Aβ but harms the blood vessel wall, causing rupture and bleeding.

Therapeutic strategies focusing on modulating APOE activity and the interaction between APOE and Aβ are promising. As our understanding of the interplay between APOE variants and CAA pathology improves, we anticipate that APOE-targeted therapies will not only attenuate the pathological effect of CAA but also enhance the cognitive outcomes of patients. Advancements in this domain may pave the way for groundbreaking therapeutic developments, providing hope for individuals experiencing CAA and related neurodegenerative conditions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Innovation 2030—Major Project (grant number 2021ZD0201805) and the Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (grant number TJYXZDXK-004A).

Authors contributions

HH, SW and YH drafted the manuscript. QW and LH collected the related papers and participated in the design of the review. NZ participated in the design of the review and helped draft and revise the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data was generated or analyzed.

References

- 1.Charidimou A, Boulouis G, Frosch MP, et al. The Boston Criteria v2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre MRI-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(8):714–725. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00208-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koemans EA, Chhatwal JP, van Veluw SJ, et al. Progression of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a pathophysiological framework. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(7):632–642. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00114-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee G, Collinge J, Fox NC, et al. Clinical considerations in early-onset cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Brain. 2023;146(10):3991–4014. doi: 10.1093/brain/awad193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cisternas P, Taylor XA, Lasagna-Reeves C.. The amyloid-tau-neuroinflammation axis in the context of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(24):6319. doi: 10.3390/ijms20246319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, et al. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(9):501–518. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esiri M, Chance S, Joachim C, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, subcortical white matter disease and dementia: literature review and study in OPTIMA. Brain Pathol. 2015;25(1):51–62. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenberg SM, Vonsattel JP, Segal AZ, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E epsilon2 and vasculopathy in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Neurology. 1998;50(4):961–965. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chawla A, Boisvert WA, Lee CH, et al. A PPAR gamma-LXR-ABCA1 pathway in macrophages is involved in cholesterol efflux and atherogenesis. Mol Cell. 2001;7(1):161–171. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenberg DTA, Kuzawa CW, Hayes MG.. Worldwide allele frequencies of the human apolipoprotein E gene: climate, local adaptations, and evolutionary history. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2010;143(1):100–111. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.21298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Utermann G, Hees M, Steinmetz A.. Polymorphism of apolipoprotein E and occurrence of dysbetalipoproteinaemia in man. Nature. 1977;269(5629):604–607. doi: 10.1038/269604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson RJ, Hyman BT, Serrano-Pozo A.. Multifaceted roles of APOE in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2024;20(8):457–474. doi: 10.1038/s41582-024-00988-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumsden AL, Mulugeta A, Zhou A, et al. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype-associated disease risks: a phenome-wide, registry-based, case-control study utilising the UK Biobank. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102954. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendel T, Gromadzka G.. Polimorfizm genu apolipoproteiny E (APOE) a ryzyko i rokowanie w krwotokach mózgowych spowodowanych przez mózgową angiopatię amyloidowq. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 2010;44(6):591–597. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3843(14)60157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh PP, Singh M, Mastana SS.. APOE distribution in world populations with new data from India and the UK. Ann Hum Biol. 2006;33(3):279–308. doi: 10.1080/03014460600594513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbo RM, Scacchi R.. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) allele distribution in the world. Is APOE*4 a “thrifty” allele? Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:301–310. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1999.6340301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Husain MA, Laurent B, Plourde M.. APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: from lipid transport to physiopathology and therapeutics. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:630502. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.630502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abondio P, Sazzini M, Garagnani P, et al. The genetic variability of APOE in different human populations and its implications for longevity. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(3):222. doi: 10.3390/genes10030222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y-J, Caulfield T, Xu Y-F, et al. The dual functions of the extreme N-terminus of TDP-43 in regulating its biological activity and inclusion formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22(15):3112–3122. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caulfield T, Devkota B.. Motion of transfer RNA from the A/T state into the A-site using docking and simulations. Proteins. 2012;80(11):2489–2500. doi: 10.1002/prot.24131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisgraber KH, Rall SC, Mahley RW.. Human E apoprotein heterogeneity. Cysteine-arginine interchanges in the amino acid sequence of the apo-E isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1981;256(17):9077–9083. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)52510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martens YA, Zhao N, Liu C-C, et al. ApoE Cascade Hypothesis in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Neuron. 2022;110(8):1304–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Premkumar DR, Cohen DL, Hedera P, et al. Apolipoprotein E-epsilon4 alleles in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cerebrovascular pathology associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(6):2083–2095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rüb UDO, et al. . Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61(3):282–293. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.3.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldberg TE, , Huey ED, , Devanand DP. Associations of APOE e2 genotype with cerebrovascular pathology: a postmortem study of 1275 brains. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(1):7–11. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boros BD, Greathouse KM, Gearing M, et al. Dendritic spine remodeling accompanies Alzheimer’s disease pathology and genetic susceptibility in cognitively normal aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;73:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez GA, Burns MP, Weeber EJ, et al. Young APOE4 targeted replacement mice exhibit poor spatial learning and memory, with reduced dendritic spine density in the medial entorhinal cortex. Learn Mem. 2013;20(5):256–266. doi: 10.1101/lm.030031.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun G-Z, He Y-C, Ma XK, et al. Hippocampal synaptic and neural network deficits in young mice carrying the human APOE4 gene. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2017;23(9):748–758. doi: 10.1111/cns.12720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, et al. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(89):89ra57. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valencia-Olvera AC, Balu D, Bellur S, et al. A novel apoE-mimetic increases brain apoE levels, reduces Aβ pathology and improves memory when treated before onset of pathology in male mice that express APOE3. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15(1):216. doi: 10.1186/s13195-023-01353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, et al. APOE4 leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature. 2020;581(7806):71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koizumi K, Hattori Y, Ahn SJ, et al. Apoε4 disrupts neurovascular regulation and undermines white matter integrity and cognitive function. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3816. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06301-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barisano G, Kisler K, Wilkinson B, et al. A “multi-omics” analysis of blood–brain barrier and synaptic dysfunction in APOE4 mice. J Exp Med. 2022;219(11):e20221137. doi: 10.1084/jem.20221137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rhea EM, Hansen K, Pemberton S, et al. Effects of apolipoprotein E isoform, sex, and diet on insulin BBB pharmacokinetics in mice. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18636. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-98061-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamley IW. The amyloid beta peptide: a chemist’s perspective. Role in Alzheimer’s and fibrillization. Chem Rev. 2012;112(10):5147–5192. doi: 10.1021/cr3000994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grimm MOW, Grimm HS, Hartmann T.. Amyloid beta as a regulator of lipid homeostasis. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(8):337–344. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heber S, Herms J, Gajic V, et al. Mice with combined gene knock-outs reveal essential and partially redundant functions of amyloid precursor protein family members. J Neurosci. 2000;20(21):7951–7963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-07951.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deng Y, Wang Z, Wang R, et al. Amyloid-β protein (Aβ) Glu11 is the major β-secretase site of β-site amyloid-β precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1(BACE1), and shifting the cleavage site to Aβ Asp1 contributes to Alzheimer pathogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37(12):1962–1969. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lichtenthaler SF. Alpha-secretase in Alzheimer’s disease: molecular identity, regulation and therapeutic potential. J Neurochem. 2011;116(1):10–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang S, Wang Z, Cai F, et al. BACE1 cleavage site selection critical for amyloidogenesis and Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2017;37(29):6915–6925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0340-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun X, He G, Song W.. BACE2, as a novel APP theta-secretase, is not responsible for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease in Down syndrome. FASEB J. 2006;20(9):1369–1376. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5632com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]