Abstract

Background

There has been significant progress in understanding neurosarcoidosis (NS) as a distinct disorder, which encompasses a heterogeneous group of clinical and radiological alterations which can affect patients with systemic sarcoidosis or manifest isolated.

Rationale and aim of the study

The healthcare challenges posed by NS and sarcoidosis in general extend beyond their physical symptoms and can include a variety of psychosocial factors, therefore the recognition of main neuropsychiatric symptoms can be useful to approach patients with NS. Methods: For this purpose, databases such as Pubmed, Medline and Pubmed Central (PMC) have been searched.

Results

A correct diagnosis of NS is established by the combination of clinical picture, imaging features and the histopathological finding of non-caseating and non-necrotizing granulomas. After analyzing the current literature, there is a need for specific, case-control, cohort and clinical trials on the psychiatric manifestations of sarcoidosis, because the evaluation of psychological distress (in terms of emotional suffering e.g. anxiety or depression) is often underestimated.

Discussion and Conclusion

Exploring the neuropsychiatric manifestations of sarcoidosis is useful to raise awareness of this condition among clinicians and to establish a holistic management, which includes both physical and psychological aspects.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, anxiety, depression, pain, neuropathy, fatigue, headache, disease

Introduction

Neurological manifestations of sarcoidosis encompass a heterogeneous group of clinical and radiological alterations which can affect patients with systemic sarcoidosis or manifest isolated at any age and of all ethnic groups [1,2]. Psychiatric symptoms may be concomitant with the neurosarcoidosis (NS) diagnosis or in the context of systemic sarcoidosis [3]. The most common histological elements of sarcoidosis are noncaseating granulomas involving ubiquitous organ and tissues, most often lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes. Pulmonary disease can be found indeed in up to 90% of cases, and African Americans, Scandinavians and subjects aged between 30 and 50 years are the group with the highest prevalence of disease [4]. Black patients exhibit the highest risk of severe disease being the group most often associated with cardiac and/or progressive disease [5]. The epidemiology of NS has not been clarified completely; however, it has been estimated that 5%–10% of sarcoidosis patients manifest with overt clinical symptoms but the disease can be found in up a higher number of autopsies, revealing that a high number of asymptomatic or misdiagnosed cases are missed at an initial diagnostic workup [6]. The diagnosis is even more challenging in regions/countries with lower incidence of sarcoidosis, where the heterogeneity of clinical pictures can limit the access to a diagnostic confirmation with biopsy of the central nervous system (CNS), which is mandatory in some cases [7,8]. The recognition of main neuropsychiatric symptoms that can manifest beyond physical manifestation is important in order to improve the global awareness of the disease. For this purpose, databases such as Pubmed, Medline and Pubmed Central (PMC) have been searched. The keywords anxiety OR depression OR psychiatric symptoms AND sarcoidosis OR neurosarcoidosis have been included in this search, which has been conducted in the period between inception to April 2024.

Neurosarcoidosis (NS)

The central nervous system (CNS), which is divided into cerebral and spinal nervous system, represents the most common localization of NS. Two types of NS can be distinguished: type A, where extra-neural sarcoidosis is evident, and type B, where there is no extra-neural involvement from sarcoidosis (isolated NS). Beyond distinctive symptoms, patients with cerebral NS can also display a spectrum of nonspecific manifestations, such as fever, headache, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting [9–11]. Moreover, some patients can develop emotional lability (i.e. euphoria, depression, aggression, apathy), anxiety, and other psychiatric disorders [12]. Cranial neuropathy, which can be isolated or multiple, is the most frequent manifestation of cerebral NS being present in 25-70% of cases. Any cranial nerve can be affected, but the II and VII cranial nerves are the most commonly involved [10,11]. Facial neuropathy accounts for 70% of the isolated forms, frequently occurring at the beginning of the disease. It is primarily unilateral but often bilateral. In these cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) helps identify nerve lesions as thickening and enhancement at the level of the inflamed area. Cranial nerve involvement can be associated with leptomeningeal alterations or represent an isolated finding [10,11].

Parenchymal lesions are detectable in about 50% of cases [13]. They are characterized by non-enhancing white matter abnormalities and are mainly localized in the periventricular regions. Intraparenchymal lesions are detected on T2-weighted images as areas of high signal intensity, which are difficult to differentiate from multiple sclerosis. Also, concomitant vascular comorbidities and age can be potential confounders because imaging does not differentiate between these entities and NS. Meningeal infiltration may occur in up to 40% of patients [14,15]. Basal leptomeninges are more frequently affected than pachymeningitis. The most common findings in MRI studies of nervous system involvement are leptomeningeal abnormalities, mainly diffuse or focal thickening and enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images [10, 16]. The course can be sub-acute, chronic, or recurrent, usually associated with a good outcome. When performed, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination reveals lymphocytic pleocytosis with protein elevation and low glucose, while MRI is used to detect leptomeningeal enhancement. Sarcoidosis-associated meningeal disease should be differentiated from lymphoma and tuberculosis involving the leptomeninges.

CNS manifestations of sarcoidosis also include intracranial mass lesions, vasculopathy, hydrocephalus, and seizures [9–11]. Involvement of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland is a rare occurrence but may cause neuroendocrine dysfunction, such as diabetes insipidus [17,18].

Spinal sarcoidosis was initially reported as an ultra-rare manifestation of NS often accompanied by leptomeningeal involvement (61%). However, recent studies have documented myelopathy in some 19%–26% of patients with NS [19,20] with concurrent brain involvement being observed in 70% of cases. Spinal cord involvement is characterized by high signal on T2-weighted images, low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and patchy enhancement after contrast administration. Intramedullary lesions show hypointense caption on T1 and hyperintense on T2 with post-contrast nodular enhancement and a preference for the cervicothoracic cord. Cauda equina nerve roots and conus medullaris are also frequently involved. However, imaging findings are often nonspecific, making diagnosis challenging, especially when NS is the only manifestation of the disease [21]. Several patterns of myelitis have been described on MRI, with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis being the most common [22–24]. Sarcoid myelopathy should be distinguished from other neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, glioma, transverse myelitis, or acute encephalomyelitis. Neurosarcoidosis can also manifest as dural involvement appearing as a nodular thickening on T1-weighted images and hypointense lesion on T2-weighted images [25,26]. Skull lesions, a rare manifestation of NS, display well-circumscribed nonsclerotic margins (“punched out”), whereas skeletal involvement, which is reported in 1-13% of cases, manifests as multiple contrast enhanced lesions. Lytic lesions show low T1 and high T2 signal, with sclerotic lesions displaying low T1 and T2 signal [27,28].

Disease of peripheral nerves

Sarcoid neuropathy is less studied and, to some extent, more challenging to recognize than other forms of NS. The plethora of peripheral nervous system (PNS) manifestations of sarcoidosis include large (LFN) and small (SFN) fiber neuropathy, which can develop in acute or chronic courses, polyradiculopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and polyneuropathy with sensory, motor, and sensorimotor features. However, chronic symmetrical axonal sensory-motor polyneuropathy is the most common manifestation [29]. Peripheral neuropathy is estimated to occur in 2–40% of patients with NS, more often Caucasians [30,31]. The involvement of PNS can occur at any time in the disease course, sometimes as the first manifestation of the disease. For instance, in a French clinicopathological study of 11 patients with peripheral neuropathy, only 2 had a diagnosis of sarcoidosis before muscle and nerve biopsy [32]. The mechanisms that lead to the neuropathy remain poorly understood, but compression by granuloma and inflammation may contribute to axonal suffering and chronic demyelination.

A biopsy showing the characteristic noncaseating granulomas is generally needed to diagnose sarcoidosis-related PNS; when performed, the biopsy should sample the muscle and nerve together, if possible, as this improves the diagnostic yield [33]. SFN is a common and debilitating manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis, but its pathogenesis remains unknown. In affected individuals, SFN involves the small nerve fibers, thus the peripheral thinly myelinated Aδ fibers and the unmyelinated C nerve fibers [34]. Symptoms of SFN vary, but common early symptoms include a burning sensation in hands and feet, paresthesia, and restless legs syndrome [35]. Current consensus criteria for NS categorize small fiber neuropathy as a stand-alone entity (i.e. a “para-neurosarcoidosis” manifestation of the disease) not necessarily due to direct granulomatous infiltration [9]. In a study of 143 patients with sarcoidosis-associated SFN, other causes of neuropathy were found in 28 cases, highlighting the importance of a thorough evaluation to exclude alternative etiologies [36]. SFN is associated with carriage of the HLA-DQB1*0602 allele, suggesting the existence of a genetic predisposition [30,31].

Sarcoidosis-related myopathy

Although muscle involvement in sarcoidosis is common, occurring in 60-80% of cases, only 0.5 to 2.5% of patients manifest symptomatic disease with fatigue, myalgias, or weakness [37,38]. Sarcoidosis is the most common cause of non-necrotizing granulomatous myopathy; other less common etiologies include autoimmune disorders (e.g. eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, autoimmune thyroiditis, Crohn’s disease), inclusion-body myositis, myasthenia gravis, anti-mitochondrial autoantibody with or without primary biliary cirrhosis, and chronic graft-vs-host disease [39,40]. Clinical subtypes of sarcoidosis myopathy include chronic myopathy, nodular disease, and acute myositis [41,42]. The most common type is chronic myopathy, a slow progression syndrome, which, similar to sporadic inclusion-body syndrome, occurs predominantly in the 6th-7th decade and is characterized by symmetric and progressive weakness involving proximal muscles, more often of the lower limbs. The main clinical difference is the poor steroid responsiveness of chronic sporadic inclusion body myositis-like syndromes compared to chronic sarcoidosis myopathies. Creatine kinase is generally normal. The absence of sensory involvement helps distinguish between sarcoid myopathy and sarcoid neuropathy. Electromyography (EMG), muscle MRI, and fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography(FDG-PET) are helpful in diagnosis [43–46].

Acute myositis is characterized by severe myalgia, orbital myositis, and rapidly progressive weakness of the proximal limbs, typically in younger patient groups (3rd-6th decades). FDG-PET may show the typical “tiger man” sign (diffuse multilinear FDG uptake, predominantly in the leg muscles). Notably, acute myositis is often accompanied by serum hypercalcemia [47,48].

Patients generally respond well to corticosteroids with methotrexate being reserved to refractory cases [49,50]. Nodular syndromes are characterized by palpable nodules (clusters of granulomas), with an age of onset of 20-40 years; these patients are symptomatic for myalgias (in their legs more than arms) but rarely complain of weakness. EMG, in contrast with acute myalgia and chronic myopathy, is generally normal, without myopathic potentials. Response to corticosteroid treatment is good, but relapses are common [51].

Diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis

Imaging findings of NS are present in about 10% of patients affected by systemic disease, but histological evidence of NS has been reported in up to 25% of cases in autopsy studies [9–11]. Due to the lack of pathognomonic clinical manifestations and universally agreed upon diagnostic criteria, NS may represent a diagnostic challenge, particularly when it occurs in isolation. Some diagnostic criteria have been suggested to improve the detection of NS, defining the diagnosis as possible with the association of clinical presentation, MRI, CSF, and/or EMG/NCS findings of typical granulomatous CNS inflammation, and probable if in addition there is also pathological confirmation of sarcoidosis [9]. In such cases, the diagnosis of NS needs to be confirmed histologically after exclusion of alternative etiologies. Yet, biopsy is performed in highly selected cases after careful evaluation of benefits and risks of the procedure. Recently, Berntsson et al. performed a retrospective cohort study of individuals primarily diagnosed with NS at a tertiary center in Sweden from 1990 to 2021 [25]. They identified 90 patients, 54 with possible NS and 36 with probable sarcoidosis. Notably, CNS biopsy revealed an alternative diagnosis in 24 patients (27%). Following extensive workup (i.e. clinical features, laboratory tests, including CSF and serum analysis, MRI, FDG-PET, chest high resolution computed tomography (HRCT), nerve conduction studies, EMG, and pathology reports of CNS and extra-neural biopsies), only 14 patients were diagnosed as “definite” NS, with the remainder being either “probable” (n = 32) or “possible” (n = 20). Table 1 summarizes the diagnostic criteria for Definite, Probable and Possible NS [9–11]. When CNS involvement is suspected, the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group recommends brain, cervical, thoracic, and lumbar MRI with and without gadolinium [9]. A comprehensive analysis of CSF is also indicated. Patients with suspected PNS sarcoidosis should undergo an EMG and nerve conduction study; nerve or muscle biopsy is also recommended [9]. The skin and mediastinal or laterocervical lymph nodes are easily accessible sites to biopsy for confirming the diagnosis of sarcoidosis when NS is associated with systemic involvement [52].

Table 1.

Level of confidence in the diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis (adapted by [2]).

| Definite | Clinical presentation suggestive of NS. Exclusion of other possible diagnoses. Positive nervous system histology is needed. |

| Probable | Clinical presentation suggestive of NS. Laboratory support for CNS inflammation (CSF and/or MRI evidence compatible with NS). Exclusion of other possible diagnoses. |

| Possible | Clinical presentation suggestive of NS. Exclusion of other possible diagnoses. |

NS: neurosarcoidosis; CNS: cerebral neurosarcoidosis; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

When a biopsy is not feasible, imaging findings, although nonspecific, are crucial in defining NS, with MRI being a very helpful diagnostic tool [26].

Treatment of neurosarcoidosis

The treatment of CNS neurosarcoidosis aims at minimizing organ damage and preventing organ dysfunction caused by granulomatous inflammation. As with other forms of the disease, corticosteroids are the first-line treatment, with immunosuppressants (i.e. methotrexate, mycophenolate, or azathioprine) being reserved to patients unresponsive or intolerant to corticosteroids [52]. Infliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody may be beneficial in patients with refractory disease [53–56]. However, a degree of relapse may be observed, and infection is the main concern for adverse events. When response to treatment is scarce or absent, it is wise to reconsider the diagnosis of NS and exclude alternative diagnoses such as tuberculosis, lymphoma, and multiple sclerosis. CSF analysis may be helpful, but the levels of IL-2 receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme and CD4/CD8 T cell ratio are neither sensitive nor specific of NS [57].

Anxiety and depression in sarcoidosis patients

Depressive symptoms

The healthcare challenges posed by sarcoidosis extend beyond its physical symptoms and encompass a variety of psychosocial factors. Among these, depression and anxiety emerge as frequent comorbidities, significantly heightening the overall burden of the disease on affected individuals [58,59].

The experience of chronic illness, coupled with the uncertainty of the prognosis, often weighs heavily on patients with sarcoidosis, impacting their functional abilities and diminishing their quality of life [60,61]. Social isolation can further compound these psychological struggles, as physical limitations and a lack of public awareness for the disease contribute to a decrease in psychosocial well-being [58]. Pulmonary symptoms, such as impaired respiratory function, can exacerbate fatigue and psychiatric symptoms, creating an interplay between physical and mental health [62] Additionally, emerging research suggests a direct influence of inflammatory processes on psychological responses in the central nervous system, with cytokines like Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α implicated in alterations to brain function, cognition, and sleep patterns [63]. An imbalance in cytokine levels, tipping towards a proinflammatory state, has been also linked to psychiatric disorders like Major Depressive Disorder [64]. Finally, although treatments such as steroids are integral to sarcoidosis management, their potential impact on psychological symptoms warrants consideration, although the existing literature does not point to a direct association between steroid use and clinically manifest depression [65].

While it’s established that depression and anxiety rates are elevated in sarcoidosis patients compared to the general population, epidemiological data present a wide range of variability across studies [62]. The prevalence of depression among patients with sarcoidosis spans from 4% to 66% across different investigations, reflecting differences in study populations and assessment methodologies [66–70]. Notably, most studies rely on self-reported measures rather than formal psychiatric evaluations, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation [60]. Nevertheless, the presence of depressive symptoms holds clinical significance and should be integrated into the comprehensive care of sarcoidosis patient [60]. Disparities in depression prevalence between sarcoidosis patients and the general population are most pronounced among those under 60 years old, reflecting the heightened impact of disease-related disability and dysfunction in the working-age population [62]. Factors associated with depressive symptoms include female sex, limited access to healthcare, lower socioeconomic status, dyspnea, high disease severity, and long diseases history [62, 65, 71–73]. In this context, sleep disorders emerge as a particularly relevant comorbidity of sarcoidosis, correlating strongly with depression and contributing to cognitive impairments and diminished overall quality of life [74]. Additionally, hypothyroidism, often occurring concurrently with sarcoidosis, may exacerbate depressive symptoms [75] Ethnicity might also play a role, with some studies indicating a link between Hispanic ethnicity and depression in patients with sarcoidosis, while others did not find a significant influence of ethnic factors [65, 76]. Depressive symptoms intertwine with fatigue in a bidirectional relationship, compounding the burden on sarcoidosis patients [77]. Functional impairment due to fatigue can exacerbate or precipitate depressive symptoms, while depression can, in turn, undermine self-care behaviors such as diet, exercise, and treatment adherence, perpetuating fatigue [63].

Anxiety in sarcoidosis

Research focusing specifically on anxiety symptoms is sparser. In a large German cohort, half of the patients exhibited symptoms indicative of anxiety, with disparities most pronounced in age groups under 60 [62]. In a smaller Italian cohort, 6% of patients met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria for panic disorder and 5% for a generalized anxiety disorder [78]. Factors associated with elevated anxiety rates include female gender, dyspnea, symptom severity, multi-organ involvement, and comorbidities such as sleep apnea [62, 79]. Among disease symptoms, dyspnea emerges as a key correlate of anxiety symptoms [62]. Furthermore, anxiety appears to exacerbate fatigue, with anxious patients exhibiting a 2.4-fold higher risk of experiencing fatigue compared to patients without anxiety [80].

Psychological burden, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and outcome of patients with sarcoidosis and moderate-severe symptoms

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multi-dimensional concept which captures both physical and psychosocial domains and is useful to measure the effects of health status on quality of life [81]. Altered physical status, chronic pain, work absenteeism, social isolation and loss of income are all factors that can be associated with diminished HRQoL in sarcoidosis patients [59]. Patients with sarcoidosis and moderate-severe symptoms (depression and/or anxiety) exhibit worse HRQoL as compared to patients without psychological symptoms. Interestingly, sarcoidosis patients with moderate-severe psychological symptoms visit the emergency department (ED) more frequently (relative risk (RR) of 8.87 and 13.05 for depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively) and those with moderate-severe depressive symptoms show a lower diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) in comparison to patients without depressive symptoms. Which component precipitates or worsens the other is still unknown [3].

In a study it emerged a significant, positive correlation between mood disturbances and respiratory parameters such as the forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV(1)) and forced vital capacity (FVC). Altered pulmonary function indices such as a reduced FEV1 and FVC correlated well a high rate of psychiatric comorbidity, evaluated by the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q) [78].

In light of these findings, a multidisciplinary treatment approach that acknowledges the psychosocial dimensions of sarcoidosis is imperative. Screening for depression and anxiety should be incorporated into routine clinical evaluations of sarcoidosis patients, facilitating timely interventions to address mental health needs [82]. Moreover, interventions such as pulmonary rehabilitation have shown promise in ameliorating depressive symptoms in sarcoidosis patients, highlighting the potential benefits of comprehensive management strategies [83].

Other mood disorders in sarcoidosis patients

The prevalence of other mood disorders in patients with sarcoidosis has not established yet.

Some authors have reported at least one of psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV) axis I diagnosis in the 44% of sarcodosis patients evaluated in their study. Specifically, a bipolar disorder was found in the 6.3% and an obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) was found in the 1.3% of them. The highest prevalence was found in those subjects with a multi-systemic involvement, severe radiographic stage and chronic asthenia. However, the limited sample size of this study does not allow to make epidemiological conclusions [78]. Interestingly, it has been hypothesized an autoimmune-based mechanism at the basis of OC symptoms in one case. Previously it has been reported an association between OC symptoms and autoimmune connective tissue disorders. In a patient with OC symptoms, some authors have found recently an inflammatory cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) profile, with elevated IgG index, intrathecal IgG synthesis, CSF-specific oligoclonal bands, a positive MRZ reaction and a distinct antinuclear antibody pattern with perinuclear staining at tissue-based assays of both serum and CSF. Non-caseating granulomas have been found at endobronchial-guided lymph node biopsy and, surprisingly, OC symptoms improved after immunotherapy for sarcoidosis. These data suggest that in some cases the mechanism underlying some mood disturbances can be much more complex than a primary psychiatric disorder, and that an organic basis should be always excluded [84].

Eating disorders

Eating disorders are a rarely described part of the clinical picture or complication of sarcoidosis and can have a multifactorial etiology. However, it seems that they are often underestimated and unrecognized, and may consequently lead to a worse prognosis due to malnutrition of patients [85].

The causes of eating disorders in the course of sarcoidosis can be generally divided into 3 groups: 1) the specific location of the granulomas, 2) part of the clinical picture or a complication of it, or 3) an adverse effect of the drugs used [86,87].

Specific localization may involve hypothalamic-pituitary infiltration by sarcoid granulomas or extensive lymphocytic infiltration in this region of the brain. This is a rare localization and then the disease manifests secondary to the lesion with endocrine and non-endocrine symptoms thus: diabetes insipidus, decreased libido, galactorrhea, dysregulation of body temperature and eating disorders including anorexia [88]. In gastrointestinal involvement, lack of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and food intolerance can also lead to malnutrition and significant weight loss [87].

Sarcoidosis is often asymptomatic, but it is estimated that up to ∼2/3 of patients have systemic symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, loss of appetite and weight loss. These are nonspecific symptoms that, especially at the outset, pose many diagnostic difficulties and delay the introduction of treatment [5].

In severe sarcoidosis, the clinical manifestations and complications of the disease depend on the organs involved. An increased risk of eating disorders including anorexia may be associated with renal involvement including granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN), nephrocalcinosis, nephrolithiasis and hematuria, which can lead to malnutrition [89,90]. Rare cases of acute kidney injury without extrarenal symptoms as the first manifestation of the disease have been observed. Kikuchi et al. described a case of a 70-year-old man with progressive worsening kidney function. The patient also exhibited severe anorexia, malaise and weight loss. Symptoms completely resolved after oral prednisolone was started and renal function was improved [91].

There are also reported cases in which anorexia and weight loss were the first manifestation of sarcoidosis preceding in time other symptoms of the disease [85].

In the chronic form of sarcoidosis with involvement of multiple organs including the lungs and heart, the consequence of failure of these organs is weight loss, eating disorders, asthenia, anorexia, malnutrition and cachexia [92]. In addition, patients with sarcoidosis are likely to have an increased risk of certain malignancies, such as lymphomas, which can lead to similar complications [63].

It is also important to keep in mind that drugs used in the treatment of sarcoidosis, both first- and second-line as well as modern biologic drugs, have among their adverse effects fatigue, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and anorexia [93].

This is particularly important in the case of methotrexate (MTX), which acts as an anti-inflammatory agent and immunomodulator. Given its mechanism of action, MTX can cause many adverse events, including nausea and anorexia [94]. Less commonly, similar symptoms are caused by systemic glucocorticoids but it is important to remember that their prolonged intake can cause fatigue, nausea, headaches as well as eating disorders on the background of effects on the gastrointestinal system [95,96]. Among the new drugs used in the treatment of sarcoidosis, rituximab, infliximab, and adalimumab may have potential negative effects on appetite and possible eating disorders [97–99].

Headache and pain syndromes

Headache and painful syndromes are major contributors to the disability of sarcoidosis patients. Drawing solid conclusions about the role of headache in sarcoidosis is challenging [100]. Most evidence arises from single case reports or cases series with small figures, and there are far more literature reviews than original data studies. In addition, the assessment of causality is complex, since headache can be caused by various pathophysiological processes, but also due to comorbid diseases, such as primary headache disorders, or some drugs employed in its treatment.

The prevalence of primary headache disorders in the general population is very high, with tension-type headache and migraine with a prevalence of 23.3% (95%CI: 21.1 − 25.7%) and 13.3% (95% CI: 12.4-14.3%), respectively [101]. Indeed, they represent the second and third most prevalent disorders [101], with a prevalence that is consistent across regions, races and countries [102]. Despite these high figures, patients with sarcoidosis have a prevalence of migraine that exceeds the expected rate. According to a cohort study that assessed all consecutive cases of sarcoidosis between 2010 and 2015 observed that 22/78 (28%) patients with sarcoidosis without and 6/18 (33%) patients with sarcoidosis with sarcoidosis NS fulfilled migraine criteria [103] based on the ID migraine screening test [104].

In a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 29 articles, accounting for 1088 patients diagnosed as of 2015, headache was a common symptom in NS patients, estimated in 32% (95% CI: 28-35%) [24]. In a single-center prospective cohort study that assessed all consecutive patients evaluated between 2016 and 2020, 29 patients with newly diagnosed NS were screened, and 20 were finally eligible. Headache was the most prevalent symptom at baseline, reported in 12/20 (60%) cases, and its prevalence varied between 6/20 (30%) and 9/20 (45%) cases during follow-up [105].

In this study, the correlation between the clinical features and the imaging findings were reported, and the most commonly observed pachymeningeal enlargement in 6/12 (50%) cases, leptomeningeal and perivascular enhancement in 2/12 (16.7%), and single cases of hypophysis enhancement, thalamic enhancement, or trigeminal nerve enlargement, while 6/12 (50%) patients had neither meningeal nor perivascular enhancement [105].

The increased frequency of headache within patients with NS, when compared with systemic sarcoidosis was also supported by another study, that retrospectively analyzed the clinical presentation of 91 patients, among which, 10 had isolated NS. Headache was the most frequently observed symptom in NS patients [106].

All these findings suggest that headache can be caused by various pathophysiological processes, including aseptic meningitis, pachymeningitis, leptomeningitis, vasculitis, hypophysitis, space occupying lesions, cranial nerve neuritis or comorbid primary headache disorders [107]. In this regard, the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd version (ICHD-3) proposed a very unspecific criteria for 7.3.1 headache attributed to NS [107] (Table 2). In line with other secondary headache disorders, causation is supported by a parallel clinical course of both the headache and the presumptive causative disorder.

Table 2.

ICHD-3 criteria for 7.3.1 headache attributed to NS [107].

| Criterions | Sub-criterion (if any) | Content |

|---|---|---|

| A | Any headache fulfilling criterion C | |

| B | NS has been diagnosed | |

| C | Evidence of causation demonstrated by at least two of the following: | |

| C1 | Headache has developed in temporal relation to the onset of the NS | |

| C2 | Either or both of the following | |

| C2a | Headache has significantly worsened in parallel with worsening of NS | |

| C2b | Headache has significantly improved in parallel with improvement in the NS | |

| C3 | Headache is accompanied by one or more cranial nerve palsies | |

| D | Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis |

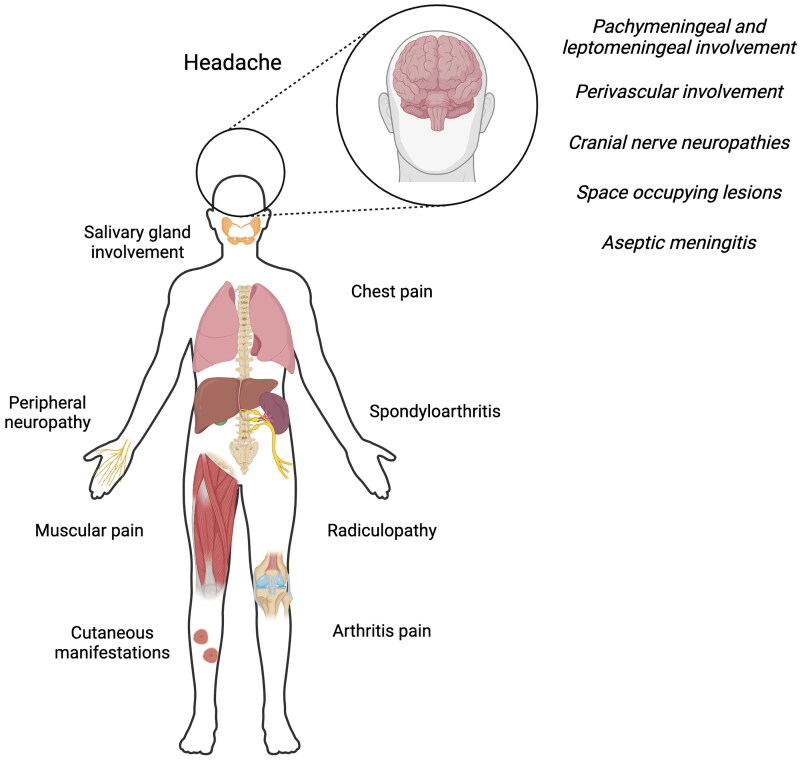

In the case of pain, it is also commonly reported in sarcoidosis, but low studies have investigated pain in NS patients. In a cross-sectional web-based survey conducted in Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands in 2017-2018, including 1072 patients, pain was reported by 74.5%, 68.9% and 62.5% patients, with statistically significant differences within countries. In addition, the frequency of pain killers was 35.3%, 48.6% and 42.7%, respectively, also with statistically significant differences [108]. In a study done in the Dutch Sarcoidosis Society without comorbidity, published in 2003, pain was reported by 594/821 (72.4%) patients, including arthralgia (53.8%), muscle pain (40.2%), headache (28%) and chest pain (26.9%) [109]. In addition, peripheral neuropathy may occur, and in the case of small fiber neuropathy, patients may present with distal neuropathic pain [110]. Bone sarcoidosis can present with spinal and articular pain [111], but also as radicular pain [112]. Abdominal pain can be caused by hepatic or splenic involvement, and facial pain may suggest parotid or salivary glands involvement [113]. The Figure 1 summarizes the main hypothesis regarding painful syndromes in sarcoidosis.

Figure 1.

Common causes of pain in sarcoidosis patients. Created with BioRender.

Fatigue

About 80% of patients with sarcoidosis suffer from chronic fatigue, which compromises significantly the quality of life, work ability [63, 114] and is associated with a high socioeconomic burden in terms of absenteeism from work and livelihood, the first which has been estimated to be around 15.9 sick-days per person annually [115]. Etiology is multifactorial, being the consequence of treatment itself (e.g. corticosteroids) and/or the consequence of comorbidities such as depression, anxiety, anemia, altered sleep patterns and hypothyroidism [63]. Furthermore, fatigue may be related to sarcoidosis itself (e.g. cardiac complications, lung and/or neurological disease and chronic inflammation) and/or drugs (e.g. weight gain, anemia or sub-clinical infection) [59].

Neuropsychobiological mechanisms of fatigue have not been clarified yet but it has been demonstrated an increase of brain activation into the angular gyrus, which is important to keep the activity of working memory system and executive functions [116].

Interventional measures which are directed to reduce fatigue can include low-dose corticosteroid drugs and pulmonary/general rehabilitation such as inspiratory muscle training [117].

Fatigue can occur occasionally or become chronic, even after the clinical remission of sarcoidosis being associated with some specific risk factors such as a specific (neurotic) personality, elevated psychological distress, and reduced baseline levels of ACTH/cortisol [118].

Conclusion

The traditional (clinical) approach to patients with sarcoidosis (both systemic and NS form), which focuses on physical symptoms and somatic aspects of the disease [119] may be insufficient to quantify the real burden of the condition.

Sarcoidosis raises significant challenges to the clinicians that extend beyond the physical symptoms, and addressing or preventing early the psychological discomfort in patients with sarcoidosis might be useful in coping better the disease and to improve the adherence to the therapy. A holistic approach, including a psychosocial evaluation at the first diagnosis of the disease might be a successful approach especially in patients at risk of psychiatric discomfort.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Ethical approval

Ethics committee approval is not required for narrative reviews.

Author contributions

CT, PS, conception and design; CT, NB, BR, DGA, MWP, MT, GA, FC, MAG, PS, analysis and interpretation of the data; CT, NB, BR, DGA, MWP, MT, GA, FC, MAG, PS, drafting of the paper, revising it critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All figures and tables are original and are not taken from other publications.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Claudio Tana is the Section Editor of the Primary Care section of Annals of Medicine.

Data sharing

Is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- 1.Voortman M, Drent M, Stern BJ.. Neurosarcoidosis and neurologic complications of sarcoidosis treatment. Clin Chest Med. 2024;45(1):91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2023.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidd DP. Neurosarcoidosis. J Neurol. 2024;271(2):1047–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00415-023-12046-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharp M, Brown T, Chen E, et al. Psychological burden associated with worse clinical outcomes in sarcoidosis. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019;6(1):e000467. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossides M, Darlington P, Kullberg S, et al. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology and clinical insights. J Intern Med. 2023;293(6):668–680. doi: 10.1111/joim.13629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Israël-Biet D, Bernardinello N, Pastré J, et al. High-risk sarcoidosis: a focus on pulmonary, cardiac, hepatic and renal advanced diseases, as well as on calcium metabolism abnormalities. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024;14(4):395. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14040395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tana C, Wegener S, Borys E, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis and treatment of neurosarcoidosis. Ann Med. 2015;47(7):576–591. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1093164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shrestha K, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Ormond DR.. Diagnostic challenges of neurosarcoidosis in non-endemic areas. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1220635. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2023.1220635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Ramón R, Gaitán-Valdizán JJ, Sánchez-Bilbao L, et al. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in northern Spain, 1999-2019: a population-based study. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;91:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern BJ, Royal W, III, Gelfand JM, et al. Definition and consensus diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis: from the neurosarcoidosis consortium consensus group. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1546–1553. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Culver DA, Ribeiro Neto ML, Moss BP, et al. Neurosarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;38(4):499–513. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson ML, White JR, Espahbodi M, et al. Cranial base manifestations of neurosarcoidosis: a review of 305 patients. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(1):156–166. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman SH, Gould DJ.. Neurosarcoidosis presenting as psychosis and dementia: a case report. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2002;32(4):401–403. doi: 10.2190/UYUB-BHRY-L06C-MPCP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradshaw MJ, Pawate S, Koth LL, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(6):e1084. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delaney P. Neurologic manifestations in sarcoidosis: a review of the literature, with a report of 23 cases. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87(3):336–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-3-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacomis D. Neurosarcoidosis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011;9(3):429–436. doi: 10.2174/157015911796557975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bathla G, Singh AK, Policeni B, et al. Imaging of neurosarcoidosis: common, uncommon, and rare. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(1):96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alfares K, Han HJ.. Neurosarcoidosis-induced panhypopituitarism. Cureus. 2023;15(8):e43169. doi: 10.7759/cureus.43169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langrand C, Bihan H, Raverot G, et al. Hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis: a multicenter study of 24 patients. QJM. 2012;105(10):981–995. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcs121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sève P, Pacheco Y, Durupt F, et al. Sarcoidosis: a clinical overview from symptoms to diagnosis. Cells. 2021;10(4):766. doi: 10.3390/cells10040766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joubert B, Chapelon-Abric C, Biard L, et al. Association of prognostic factors and immunosuppressive treatment with long-term outcomes in neurosarcoidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(11):1336–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Durel C-A, Marignier R, Maucort-Boulch D, et al. Clinical features and prognostic factors of spinal cord sarcoidosis: a multicenter observational study of 20 BIOPSY-PROVEN patients. J Neurol. 2016;263(5):981–990. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawate S, Moses H, Sriram S.. Presentations and outcomes of neurosarcoidosis: a study of 54 cases. QJM. 2009;102(7):449–460. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lury KM, Smith JK, Matheus MG, et al. Neurosarcoidosis review of imaging findings. Semin Roentgenol. 2004;39(4):495–e504. doi: 10.1016/j.ro.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fritz D, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC.. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in neurosarcoidosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berntsson SG, Elmgren A, Gudjonsson O, et al. A comprehensive diagnostic approach in suspected neurosarcoidosis. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):6539. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-33631-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JK, Matheus MG, Castillo M.. Imaging manifestations of neurosarcoidosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(2):289–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.2.1820289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bathla G, Watal P, Gupta S, et al. Cerebrovascular manifestations of neurosarcoidosis: an underrecognized aspect of the imaging spectrum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(7):1194–1200. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cicilet S, Reddy K S, Kancharla M.. Insights into neurosarcoidosis: an imaging perspective. Pol J Radiol. 2023;88:e582–e588. doi: 10.5114/pjr.2023.134021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soni N, Bathla G, Pillenahalli Maheshwarappa R.. Imaging findings in spinal sarcoidosis: a report of 18 cases and review of the current literature. Neuroradiol J. 2019;32(1):17–28. doi: 10.1177/1971400918806634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardin A, Dawkins B, Pezant N, et al. Genetics of neurosarcoidosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;372:577957. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hebel R, Dubaniewicz-Wybieralska M, Dubaniewicz A.. Overview of neurosarcoidosis: recent advances. J Neurol. 2015;262(2):258–267. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7482-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Said G, Lacroix C, Planté-Bordeneuve V, et al. Nerve granulomas and vasculitis in sarcoid peripheral neuropathy: a clinicopathological study of 11 patients. Brain. 2002;125(Pt 2):264–275. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nathani D, Spies J, Barnett MH, et al. Nerve biopsy: current indications and decision tools. Muscle Nerve. 2021;64(2):125–139. doi: 10.1002/mus.27201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Devigili G, Cazzato D, Lauria G.. Clinical diagnosis and management of small fiber neuropathy: an update on best practice. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20(9):967–980. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2020.1794825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoitsma E, Faber CG, Drent M, et al. Neurosarcoidosis: a clinical dilemma. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3(7):397–407. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tavee JO, Karwa K, Ahmed Z, et al. Sarcoidosis associated small fiber neuropathy in a large cohort: clinical aspects and response to IVIG and anti-TNF alpha treatment. Respir Med. 2017;126:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marcellis RG, Lenssen AF, Kleynen S, et al. Exercise capacity, muscle strength, and fatigue in sarcoidosis: a follow-up study. Lung. 2013;191(3):247–256. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9456-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yanardag H, Tetikkurt C, Bilir M.. Monaldi clinical and prognostic significance of muscle biopsy in sarcoidosis. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2018;88(1):910. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2018.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alhammad RM, Liewluck T.. Myopathies featuring non-caseating granulomas: sarcoidosis, inclusion body myositis and an unfolding overlap. Neuromuscul Disord. 2019;29(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chompoopong P, Liewluck T.. Granulomatous myopathy: sarcoidosis and beyond. Muscle Nerve. 2023;67(3):193–203. doi: 10.1002/mus.27741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kobak S. Sarcoidosis: a rheumatologist’s perspective. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2015;7(5):196–205. doi: 10.1177/1759720X15591310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garret M, Pestronk A.. Sarcoidosis, granulomas and myopathy syndromes: a clinical-pathology review. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;373:577975. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ten Dam L, Raaphorst J, van der Kooi AJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome in muscular sarcoidosis: a retrospective cohort study and literature review. Neuromuscul Disord. 2022;32(7):557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2022.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeshima S, Koike H, Noda S, et al. Clinicopathological features of sarcoidosis manifesting as generalized chronic myopathy. J Neurol. 2015;262(4):1035–1045. doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7680-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bullock C, McCann M, Sharma A, et al. FDG PET/CT and thyroid biopsy lead to neurosarcoidosis diagnosis. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18(11):3932–3935. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2023.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tana C. FDG-PET imaging in sarcoidosis. Curr Med Imaging Rev. 2019;15(1):2–3. doi: 10.2174/157340561501181207091552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aptel S, Lecocq-Teixeira S, Olivier P, et al. Multimodality evaluation of musculoskeletal sarcoidosis: imaging findings and literature review. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muse A, Cates M, Rogers P, et al. ‘Tiger woman sign’ hypercalcaemia: a diagnostic challenge. Clin Med (Lond). 2021;21(1):73–75. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2020-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bechman K, Christidis D, Walsh S, et al. A review of the musculoskeletal manifestations of sarcoidosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(5):777–783. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujita H, Ishimatsu Y, Motomura M, et al. A case of acute sarcoid myositis treated with weekly low-dose methotrexate. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(6):994–999. doi: 10.1002/mus.22222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen Aubart F, Abbara S, Maisonobe T, et al. Symptomatic muscular sarcoidosis: lessons from a nationwide multicenter study. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5(3):e452. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baughman RP, Valeyre D, Korsten P, et al. ERS clinical practice guidelines on treatment of sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(6):2004079. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04079-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gelfand JM, Bradshaw MJ, Stern BJ, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of CNS sarcoidosis: a multi-institutional series. Neurology. 2017;89(20):2092–2100. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen AF, Bouvry D, Galanaud D, et al. Long-term outcomes of refractory neurosarcoidosis treated with infliximab. J Neurol. 2017;264(5):891–897. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaiyanarm S, Satiraphan P, Apiraksattaykul N, et al. Infliximab in neurosarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2024;11(2):466–476. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kidd DP. Neurosarcoidosis: clinical manifestations, investigation and treatment. Pract Neurol. 2020;20(3):199–212. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2019-002349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chopra A, Kalkanis A, Judson MA.. Biomarkers in sarcoidosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(11):1191–1208. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2016.1196135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerke AK, Judson MA, Cozier YC, et al. Disease burden and variability in sarcoidosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(Supplement_6):S421–S428. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201707-564OT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saketkoo LA, Russell AM, Jensen K, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in sarcoidosis: diagnosis, management, and health outcomes. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(6):1089. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11061089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Curtis JR, Borson S.. Examining the link between sarcoidosis and depression. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):306–308. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.ed2000b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilsher ML. Psychological stress in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18(5):524–527. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3283547092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hinz A, Brähler E, Möde R, et al. Anxiety and depression in sarcoidosis: the influence of age, gender, affected organs, concomitant diseases and dyspnea. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Drent M, Lower EE, De Vries J.. Sarcoidosis-associated fatigue. Eur Respir J. 2012;40(1):255–263. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00002512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim YK, Na KS, Shin KH, et al. Cytokine imbalance in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2007;31(5):1044–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang B, Steimel J, Moller DR, et al. Depression in sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(2):329–334. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2004177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Drent M, Wirnsberger RM, Breteler MH, et al. Quality of life and depressive symptoms in patients suffering from sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15(1):59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cox CE, Donohue JF, Brown CD, et al. Health-related quality of life of persons with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2004;125(3):997–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.3.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Korenromp IHE, Heijnen CJ, Vogels OJM, et al. Characterization of chronic fatigue in patients with sarcoidosis in clinical remission. Chest. 2011;140(2):441–447. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ireland J, Wilsher M.. Perceptions and beliefs in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(1):36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Antoniou KM, Tzanakis N, Tzouvelekis A, et al. Quality of life in patients with active sarcoidosis in Greece. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(6):421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bourbonnais JM, Samavati L.. Effect of gender on health related quality of life in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2010;27(2):96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harper LJ, Gerke AK, Wang XF, et al. Income and other contributors to poor outcomes in U.S. patients with sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):955–964. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201906-1250OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mokros Ł, Miłkowska-Dymanowska J, Gwadera Ł, et al. Chronotype and the Big-Five personality traits as predictors of chronic fatigue among patients with sarcoidosis. A cross-sectional study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2023;40(2):e2023018. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v40i2.12889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benn BS, Lehman Z, Kidd SA, et al. Sleep disturbance and symptom burden in sarcoidosis. Respir Med. 2018;144s:S35–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alzghoul BN, Amer FN, Barb D, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of self-reported hypothyroidism and its association with nonorgan-specific manifestations in US sarcoidosis patients: a nationwide registry study. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00754–2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00754-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Innabi A, Alzghoul BN, Kalra S, et al. Sarcoidosis among US Hispanics in a nationwide registry. Respir Med. 2021;190:106682. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hendriks C, Drent M, De Kleijn W, et al. Everyday cognitive failure and depressive symptoms predict fatigue in sarcoidosis: a prospective follow-up study. Respir Med. 2018;138s:S24–s30. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goracci A, Fagiolini A, Martinucci M, et al. Quality of life, anxiety and depression in sarcoidosis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holas P, Krejtz I, Urbankowski T, et al. Anxiety, its relation to symptoms severity and anxiety sensitivity in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30(4):282–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bosse-Henck A, Koch R, Wirtz H, et al. Fatigue and excessive daytime sleepiness in sarcoidosis: prevalence, predictors, and relationships between the two symptoms. Respiration. 2017;94(2):186–197. doi: 10.1159/000477352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yin S, Njai R, Barker L, et al. Summarizing health-related quality of life (HRQOL): development and testing of a one-factor model. Popul Health Metr. 2016;14(1):22. doi: 10.1186/s12963-016-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thunold RF, Løkke A, Cohen AL, et al. Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34(1):2–17. doi: 10.36141/svdld.v34i1.5760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Luu B, Gupta A, Fabiano N, et al. Influence of pulmonary rehabilitation on symptoms of anxiety and depression in interstitial lung disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Respir Med. 2023;219:107433. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Endres D, Frye BC, Schlump A, et al. Sarcoidosis and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;373:577989. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kharkongor MA, Cherian KE, Kodiatte TA, et al. Uncommon cause for anorexia and weight loss. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016:bcr2016218675. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tana C, Drent M, Nunes H, et al. Comorbidities of sarcoidosis. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1014–1035. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2063375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tana C, Mantini C, Donatiello I, et al. Clinical features and diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Clin Med. 2021;10(9):1941. doi: 10.3390/jcm10091941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Polverino F, Balestro E, Spagnolo P.. Clinical presentations, pathogenesis, and therapy of sarcoidosis: state of the art. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2363. doi: 10.3390/jcm9082363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Agrawal V, Crisi GM, D’Agati VD, et al. Renal sarcoidosis presenting as acute kidney injury with granulomatous interstitial nephritis and vasculitis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(2):303–308. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tana C, Azorin DG, Cinetto F, et al. Common clinical and molecular pathways between migraine and sarcoidosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):8304. doi: 10.3390/ijms24098304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kikuchi H, Mori T, Rai T, et al. Acute kidney injury caused by sarcoid granulomatous interstitial nephritis without extrarenal manifestations. CEN Case Rep. 2015;4(2):212–217. doi: 10.1007/s13730-015-0171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.El Rhaoussi FZ, Banani S, Bouamama S, et al. Multisystemic sarcoidosis revealed by hepatosplenomegaly: a case report. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e23967. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pande A, Culver DA.. Knowing when to use steroids, immunosuppressants or biologics for the treatment of sarcoidosis. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2020;14(3):285–298. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2020.1707672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baughman RP, Cremers JP, Harmon M, et al. Methotrexate in sarcoidosis: hematologic and hepatic toxicity encountered in a large cohort over a six year period. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2020;37:e2020001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Drent M, Proesmans VLJ, Elfferich MDP, et al. Ranking self-reported gastrointestinal side effects of pharmacotherapy in sarcoidosis. Lung. 2020;198(2):395–403. doi: 10.1007/s00408-020-00323-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bast A, Semen KO, Drent M.. Nutrition and corticosteroids in the treatment of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(5):479–486. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moravan M, Segal BM.. Treatment of CNS sarcoidosis with infliximab and mycophenolate mofetil. Neurology. 2009;72(4):337–340. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000341278.26993.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Graves JE, Nunley K, Heffernan MP.. Off-label uses of biologics in dermatology: rituximab, omalizumab, infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, efalizumab, and alefacept (part 2 of 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):e55–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gerke AK. Treatment of sarcoidosis: a multidisciplinary approach. Front Immunol. 2020;11:545413. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.545413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tana C. Sarcoidosis: an old but always challenging disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021;11(4):696. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11040696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators . Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, et al. The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s10194-022-01402-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gelfand JM, Gelfand AA, Goadsby PJ, et al. Migraine is common in patients with sarcoidosis. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(14):2079–2082. doi: 10.1177/0333102418768037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, ID Migraine validation study, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003;61(3):375–382. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078940.53438.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Byg KE, Illes Z, Sejbaek T, et al. A prospective, one-year follow-up study of patients newly diagnosed with neurosarcoidosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;369:577913. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nozaki K, Scott TF, Sohn M, et al. Isolated neurosarcoidosis: case series in 2 sarcoidosis centers. Neurologist. 2012;18(6):373–377. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3182704d04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) the international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1–211. doi: 10.1177/0333102417738202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Voortman M, Hendriks CMR, Elfferich MDP, et al. The burden of sarcoidosis symptoms from a patient perspective. Lung. 2019;197(2):155–161. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00206-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hoitsma E, De Vries J, van Santen-Hoeufft M, et al. Impact of pain in a Dutch sarcoidosis patient population. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2003;20(1):33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tavee J. Peripheral neuropathy in sarcoidosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;368:577864. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2022.577864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sigaux J, Semerano L, Nasrallah T, et al. High prevalence of spondyloarthritis in sarcoidosis patients with chronic back pain. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(2):246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Humann C, Raymond C, Wendling D, et al. Clinical images: motor deficiency and radicular pain secondary to sarcoidosis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74(7):1138–1138. doi: 10.1002/art.42108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gerke AK. Morbidity and mortality in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20(5):472–478. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hendriks CMR, Saketkoo LA, Elfferich MDP, et al. Sarcoidosis and work participation: the need to develop a disease-specific core set for assessment of work ability. Lung. 2019;197(4):407–413. doi: 10.1007/s00408-019-00234-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rice JB, White A, Lopez A, et al. Economic burden of sarcoidosis in a commercially-insured population in the United States. J Med Econ. 2017;20(10):1048–1055. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1351371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kettenbach S, Radke S, Müller T, et al. Neuropsychobiological fingerprints of chronic fatigue in sarcoidosis. Front Behav Neurosci. 2021;15:633005. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.633005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Papanikolaou IC, Antonakis E, Pandi A.. State-of-the-art treatments for sarcoidosis. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J. 2022;18(2):94–105. doi: 10.14797/mdcvj.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Korenromp IH, Grutters JC, van den Bosch JM, et al. Post-inflammatory fatigue in sarcoidosis: personality profiles, psychological symptoms and stress hormones. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(2):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis-diagnosis and management. QJM. 1999;92(2):103–117. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analysed in this study.