Abstract

Demand for user authentication in virtual reality (VR) applications is increasing such as in-app payments, password manager, and access to private data. Traditionally, hand controllers have been widely used for the user authentication in VR environment, with which the users can typewrite a password or draw a pre-registered pattern; however, the conventional approaches are generally inconvenient and time-consuming. In this study, we proposed a new user authentication method based on eye-writing patterns identified using electrooculogram (EOG) recorded from four locations around the eyes in contact with the face-pad of a VR headset. EOG data acquired during eye-writing a specific pattern are converted into a ten-dimensional vector, named a similarity vector, by calculating similarity values between the EOG data for the current pattern and ten pre-defined template patterns using dynamic positional warping. If the specific pattern corresponds to password, the similarity vector will have shorter distance to a similarity vector of the pre-registered password than an individually pre-determined threshold value. Nineteen participants were instructed to eye-write ten template patterns and five designated patterns to evaluate the performance of the proposed method. A specific user’s similarity vectors were computed using the other users’ template EOG data, employing the leave-one-subject-out cross-validation scheme. The proposed method exhibited an average accuracy of 97.74%, with a false accept rate of 1.31% and a false reject rate of 3.50%. The proposed method would provide a new effective way to secure private data in practical VR applications with edge devices because it does not require heavy computational burden.

Keywords: Biometric system, Electrooculography, User authentication, Virtual reality

Introduction

As the application field of virtual reality (VR) is rapidly expanding from traditional applications in entertainment and education to new applications such as tourism, social networking, and online shopping, VR is gradually becoming important in daily life as a personal device, such as computers and smartphones [1, 2]. Similar to many other personal devices, VR applications often require user authentication, such as in-app payments, system settings, and access to private information [3]. VR user authentication is necessary when a VR head-mounted display (HMD) headset is shared by multiple users. Traditionally, many existing VR HMD devices provide hand controllers with which a VR user can typewrite his/her own password using a virtual keyboard or draw a pre-registered pattern on a pattern lock screen for user authentication; however, these conventional methods are generally time-consuming and inconvenient to use [4]. Moreover, when drawing patterns with hand controllers, other people who watch the user’s motions can readily guess the password pattern he or she set [5].

Recently, several alternatives to conventional hand-controller-based user authentication have been proposed, such as voice and gait biometrics [6, 7]. However, these two alternatives have critical limitations. Although voice biometrics-based user authentication is convenient, its performance is significantly affected by ambient noise levels and user voice status changes [6]. More importantly, this authentication method cannot be used by individuals who have trouble vocalizing because of traumatic injuries, laryngectomy, or neurodegeneration. In addition, gait biometrics-based authentication is inconvenient because it requires large body actions [7]. Moreover, biometric gait authentication is weak against mimics performed by an attacker who knows the user’s behavioral characteristics well [8]. Therefore, a new method for the convenient, robust, and secure authentication of VR users must be developed.

The detection of eyeball movement can also be used for hands-free user authentication in VR applications. Camera-based eye tracking is widely employed in VR user authentication, which is particularly useful in VR HMD environments because people around the user cannot guess the user’s gaze shift, as the user’s eyes are covered with VR HMD devices [9, 10]. Iskander et al. [11] proposed a camera-based authentication method that detects sequential eye-gaze shifts for 54 blocks on a cryptogram. The blocks were arranged at six depths in a three-dimensional virtual space. George et al. [12] proposed a camera-based authentication method that employs objects in a virtual room instead of blocks in a cryptogram to input the password. However, infrared cameras are generally too expensive for use in low-cost VR HMD headsets. Commercial HMD headsets with embedded infrared cameras for eye-tracking are more expensive than those without cameras (e.g., HTC-Vive Pro without cameras: 599 USD vs. HTC-Vive Pro Eye with cameras: 799 USD).

Electrooculogram (EOG), an electrical signal generated from the eyes, can also be used to track eyeball movements, although its precision is not as good as that of camera-based eye tracking [13, 14]. The main advantage of using an EOG as an alternative to camera-based eye trackers is its cost-effectiveness. For example, the list price of the ADS-1298 chipset for recording and processing of bioelectric signals is less than 5 USD; thus, a 4-channel EOG recording system can be implemented at a price as low as 10 USD, which is at least 20 times lower than that of infrared cameras.

In general, the electrodes used to record EOG signals are placed on the contact area between the face and the VR HMD headset [15, 16]. As the electrodes for measuring the EOG are not heavy, users are not burdened by the increased weight of the VR HMD. To detect eye movements, EOG sensors can be readily incorporated into commercial smart glasses and VR HMDs, such as JINS MEME™ [17] and EmteqPRO™ [18]. In addition, the electrodes embedded in the pads of VR HMDs can be used to record facial electromyograms for facial expression recognition [19] and silent speech recognition [20].

To the best of our knowledge, only one study, by Luo et al. [21], investigated the possibility of using EOG as a tool for user authentication in VR environments. Their method relied on EOG signals recorded as unconscious responses to external visual stimuli; however, the visual stimuli they used must be played for ten seconds, making it difficult to apply in practical scenarios. Although they attempted to reduce the stimulus presentation time to three seconds, the error equal rate (EER) was too high, with the authentication accuracy unreported.

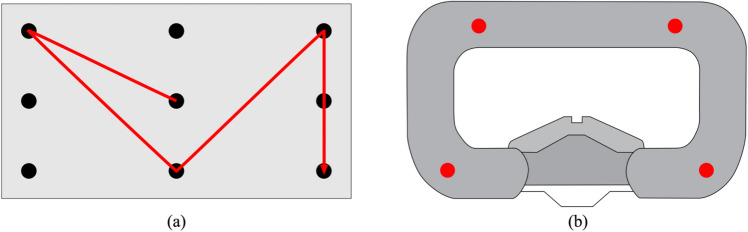

In this study, we proposed a new EOG-based VR user authentication method in which VR users can register their own password patterns by shifting their eye gaze on a 3 × 3 grid, as shown in Fig. 1a. Once a user pattern is registered in the database, a new vector-based detection algorithm is applied to identify the user during the authentication process. The proposed authentication method retains the various advantages of camera-based eye tracking, including hands-free authentication and difficulty in guessing a password by observing the user. Furthermore, the proposed method does not require deep neural networks or matrix decomposition procedures, demanding a low computing power that is sufficient to run on edge devices.

Fig. 1.

a Example of a password pattern defined by a user. Users can draw any eye-writing pattern on a 3 × 3 grid to register their own password patterns. b Electrode locations assumed to be embedded on a face-pad of a commercial VR HMD (red dots in the figure represent the electrode locations)

In biometric authentication systems, a large number of trials for individual calibration of a classifier are generally required, as there is large inter-individual variability in biosignals [22, 23]. In this study, we also investigated the feasibility of implementing a subject-independent biosignal-based user authentication method that does not require any preliminary session for training a classifier for each user but requires only a few trials for the user’s own password registration. The proposed authentication method was tested with 19 healthy participants, with which practical applicability and feasibility of the proposed method was investigated in terms of accuracy, false acceptance rate (FAR), false rejection rate (FRR), and EER, with the details of each metric provided in Appendix A.

Methods

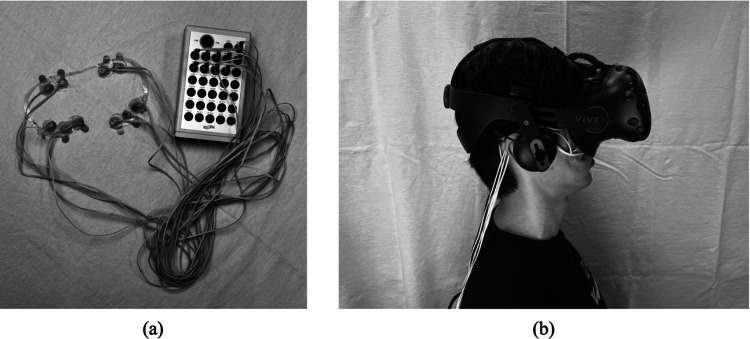

The EOG was acquired from 21 healthy participants, two of whom were excluded from further analyses after manual inspection of the signals owing to severe noise/artifact contamination of their data. Thus, EOG data from 19 participants (10 males; 9 females; mean age: 22.68 ± 2.31) were used. None of the participants reported any serious diseases or symptoms, particularly those affecting their visual function, which could affect the results of this study. Before the experiment, all the participants signed a written consent form after being informed of the detailed experimental procedure. The experimental procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hanyang University, Republic of Korea (IRB No. HYUIRB-202209-024-1). Four monopolar active electrodes were attached to the upper and lower parts of each eye, as shown in Fig. 1b, assuming the face-pad of a commercial VR HMD (HTC Vive Pro; HTC Corporation, New Taipei City, Taiwan). The EOG signals were recorded using a commercial biosignal recording system (ActiveTwo; BioSemi, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), as demonstrated in Fig. 2a, at a sampling rate of 2,048 Hz. The participants were seated on a comfortable armchair, with a distance of 0.7 m from a 27-inch monitor. MATLAB ver.2021a (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA) was used to process and analyze the EOG data.

Fig. 2.

a The electrodes were arrayed on a plastic film designed to match the shape of the face-pad of VR HMD. Actual data acquisition was implemented using four channels among the electrodes. b The appearance of wearing a VR HMD with the EOG setup

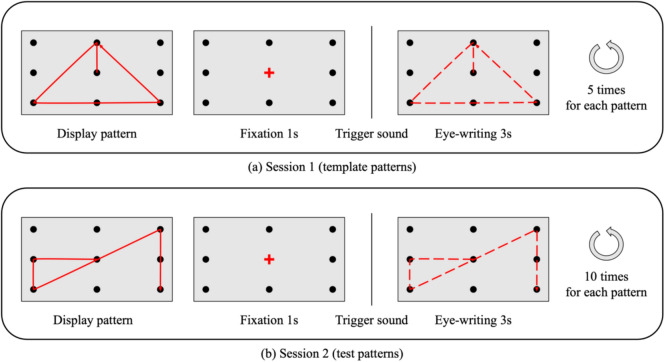

The experiment consisted of two consecutive sessions to collect template and test pattern data, as shown in Fig. 3. Both sessions consisted of repeated trials involving the presentation of a designated pattern, presentation of a baseline fixation, and eye-writing of the designated pattern. First, a designated pattern for the participant to eye-write was displayed on the screen. Second, the participants were instructed to fix their gaze on the red cross at the center of the screen for one second. After a pure-tone beep sound was presented, the participants were asked to eye-write the designated pattern within three seconds. The only difference between the two separate sessions was that the data acquisition procedure for the template patterns was repeated five times, and that for the test patterns was repeated ten times for each pattern. Ten different patterns were prepared to maximize the differences between the template patterns in the recorded EOG signals (see Fig. 7. in Appendix C). Five distinct patterns were prepared to test the feasibility of the authentication method (see Fig. 8. in Appendix C). Every pattern exhibited three changes in stroke direction and started from the center of the 3 × 3 grid. All the participants conducted the experiment using the same template and test patterns.

Fig. 3.

Experiments consisting of two sessions. Both sessions required gazing on the center of the screen for one second, followed by a trigger sound to start eye-writing the pattern for three seconds. The patterns to eye-write were displayed on the screen before the presentation of a fixation. a In Session 1, the participants were asked to eye-write ten template patterns repeatedly for five times. b In Session 2, they were asked to eye-write five test patterns repeatedly for ten times

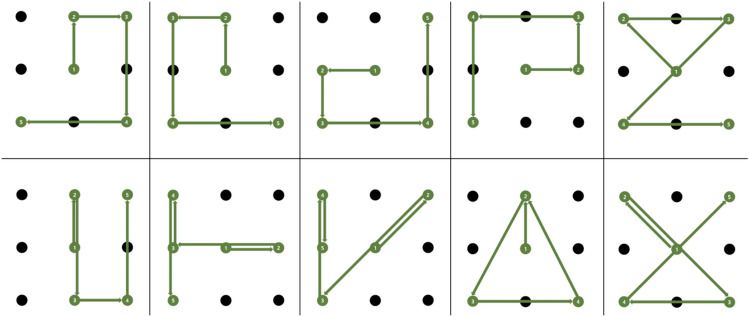

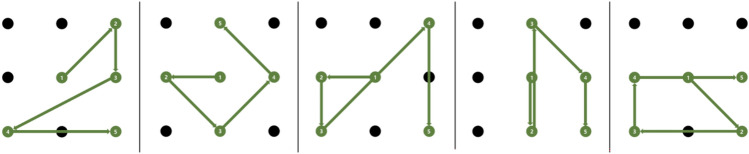

Fig. 7.

Ten template patterns used in this study. Ten template patterns were designated so that the EOG signals of eye-written patterns were different from each other because an arbitrary pattern was used as an input and the distance between each template pattern was computed

Fig. 8.

Five test patterns used in this study

The raw EOG signals were low-pass filtered using a 3rd order Butterworth filter at a cutoff frequency of 20 Hz. The horizontal and vertical EOG components were extracted from the EOG signals of the four channels. The EOG signals were then segmented into 3.5 s epochs including a 0.5 s period before the onset trigger, followed by the application of linear baseline correction to each epoch. Trials with unusual peaks, which occurred at most once in some participants, were deleted by manual inspection. Therefore, to balance the numbers of trials for each pattern, the numbers of trials in the template and test patterns were set to four and nine, respectively, by excluding the last trial for each pattern when no unusual peaks were detected. Prior to the main analyses, all recorded data were downsampled to 64 Hz. The continuous wavelet transform saccade detection algorithm proposed by Bulling et al. [24] was used to detect the saccadic eye movements. This algorithm extracts signals with absolute wavelet coefficient values greater than a preset wavelet threshold (). The wavelet coefficient of data at scale and position is defined as

| 1 |

where represents a Haar mother wavelet. The wavelet threshold and scale were set to 102.1659 and 20, respectively, as proposed in previous studies [14, 24]. Finally, the signals were resampled after saccade detection to obtain the same Euclidean distance between adjacent points, and their sizes were normalized to make the width and height equal to one.

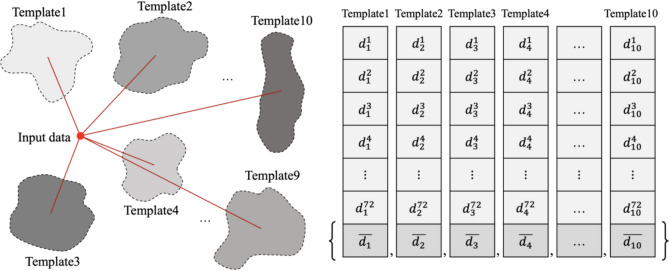

Every time a user registers or attempts to authenticate his or her own password pattern, a preprocessed EOG signal for the user’s eye-written pattern, hereafter referred to as the ‘input data,’ is converted to a vector named ‘similarity vector,’ as shown in Fig. 4. In this conversion process, ten template patterns were used as references to calculate the similarity. The similarity vector represents the distance of the input data from each of the ten template patterns. To construct the similarity vector, the similarity values between the input data and the EOG data of template eye-written patterns were calculated using the dynamic positional warping (DPW), which is an extended version of dynamic time warping [25]. As we employed a leave-one-subject-out cross-validation (LOSO-CV) strategy, four trials of 18 participants for 10 template data resulted in a 72 × 10 matrix, where the DPW values evaluated for each template pattern were arranged in a column. Subsequently, the elements in each column of the 72 × 10 matrix were averaged, yielding a 1 × 10 similarity vector. This similarity vector represents the input data in the template space, the details of which are provided in Appendix B.

Fig. 4.

Ten templates were used to convert an EOG signal of an eye-writing pattern to a similarity vector (left panel). The similarity values were calculated between input data, which is a user’s EOG signal of an eye-writing pattern, and EOG signals of ten template patterns eye-written by other people, using DPW. The notation indicates the specific template that was compared to the input data, while the notation refers to the order of trials of template EOG signals. (right panel). Averaging all DPW values in each template pattern yielded a ten-dimensional vector, referred to as the ‘similarity vector’

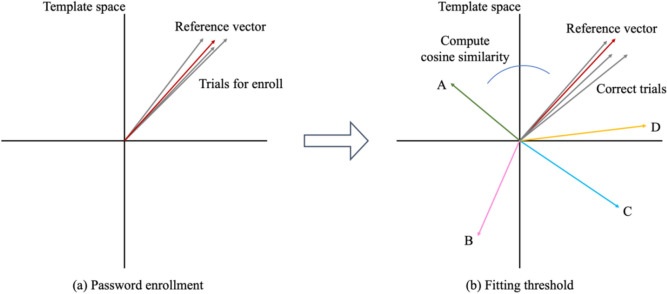

The password registration procedure consisted of two stages, as shown in Fig. 5. First, to register a password pattern, the user must eye-write the designated password pattern repeatedly. Subsequently, the similarity vectors of the obtained EOG data were averaged to create a single 1 × 10 vector, hereafter referred to as the ‘reference vector.’ In the next stage, a threshold value was determined to indicate the tolerance range for the distance between the new input similarity vector and the reference vector. This tolerance range allowed for possible variations in the EOG signals [26].

Fig. 5.

Assuming one of the test patterns as a password, there were nine trials for the test pattern acquired from a participant. a Three out of nine trials were used to evaluate the reference vector. The grey vectors represent trials used for the registration, and the red vector was the reference vector, which was the average of the three grey vectors. b Other three trials were used as correct trials to fit the threshold value. Four trials each from remaining four test patterns were also used as incorrect trials. Every correct and incorrect trials were used to compute cosine similarity with the reference vector. A, B, C, D represent four incorrect trials, and the grey vectors represent correct trials. The template space is shown as a two-dimensional space for graphical visualization, which was actually a ten-dimensional space

In the first stage, hereafter referred to as the ‘enrollment stage,’ three similarity vectors for a designated password pattern were used to create the reference vector by calculating their average. We also created a reference vector with a single similarity vector for the same password patterns. Additionally, we investigated the feasibility of not using the EOG data from each user during the enrollment stage by employing an artificially created signal instead of the user’s EOG data to reduce the burden on the users during repeated password pattern registration. An artificially created signal was generated using ideal saccadic eye movements for eye-writing password patterns.

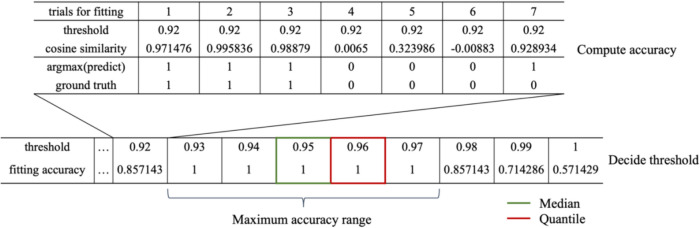

In the second stage, hereafter referred to as the ‘fitting threshold stage,’ the optimal boundary value for the allowable range of distances between the reference and similarity vectors for correct attempts was determined. To avoid the potential risk of underfitting or overfitting, the cosine similarity was used to determine the distance. This approach allowed the mapping of the vector space to a closed and bounded space, ranging from − 1 to 1. To obtain a fine threshold value, each user’s EOG data for three correct and four incorrect trials were used. The cosine similarity between the reference vector and aforementioned seven trials (three correct and four incorrect trials) was compared with 200 candidate threshold values uniformly sampled from − 1 to 1. During this process, when the cosine similarity from a specific trial was larger than the current threshold value, the trial was classified as correct, as shown in Fig. 6. After investigating the accuracy with varying thresholds, the range of thresholds with the highest accuracy was identified. The median or quartile of this range was used to determine threshold values. Every trial of eye-writing patterns in this fitting threshold stage was taken from a specific user; however, we also fitted the threshold value using correct trials from one user and incorrect trials from other participants.

Fig. 6.

To determine the threshold values, which separated the correct and incorrect attempts for authentication, we varied the threshold from − 1 to 1 with a step of 0.01 in the fitting threshold stage (top panel). For each step, when the threshold was bigger than the cosine similarity between the reference vector and a trial for fitting, the predicted value was set to 0. The ground truth was set to 0 for incorrect trials (bottom panel). Finally, we selected the median and quartile value among the range of thresholds in which the fitting accuracy was highest

Once the password pattern was registered, that is, the reference vector and threshold value were determined for each user, the authentication process became straightforward. When an authentication attempt occurred, the cosine similarity between the similarity vector for the authentication attempt and the reference vector was evaluated using the previously determined threshold value. When the cosine similarity was greater than or equal to the threshold value, the attempt was considered acceptable. However, when the cosine similarity was less than the threshold value, the attempt was rejected.

The proposed authentication method was validated for each of five test patterns. Assuming that one of the test patterns was the password pattern, of the nine trials for the test pattern, three trials were used for the enrollment stage (i.e., determination of the reference vector). Another set of three trials was used as correct trials for fitting the threshold. Four trials, each from the remaining four test patterns, were used as incorrect trials in the fitting threshold stage. The remaining three trials were used to assess the performance of the proposed authentication method. We also sampled four trials from each of the remaining four test patterns to evaluate the performance of the proposed authentication method. In summary, the authentication accuracy for each pattern was evaluated using three trials of correct eye-written patterns and four trials of incorrect eye-written patterns for each participant.

In practice, individual users are not required to provide their own eye-written patterns for the template; they are only required to register their own password patterns and several incorrect patterns, which were the test patterns used in this study, during the registration process. The authentication system can utilize publicly available template patterns to verify a user’s identity using their eye-written patterns and distinguish them from incorrect attempts. In this study, because we employed the LOSO-CV strategy, template patterns were constructed with all participants’ EOG data except for the test participant’s data. To practically apply our authentication method, the user is only required to repeat the correct trials (a designated password pattern) three times and eye-write four incorrect patterns, once for each pattern (to adjust the threshold value).

Results

The average authentication accuracy for all participants is shown in Table 1, where the threshold values were set as either the median or the quartile of the range in which the fitting accuracy was the maximum. In the case of using the median as the threshold, for Self-3 condition (three trials were used for enrollment stage), the average accuracy was 98.0451%, FAR was 2.6316%, and FRR was 1.0526%. In the Self-1 condition (a single trial was used for enrollment), the average accuracy achieved was 97.7444%, which differed from that of Self-3 by 0.3007%p. In the case of Artificial-1 (where an artificially created EOG signal was used for enrollment), the average accuracy was equal to that of Self-1. When the quartile of the range was set as the threshold, Self-3 exhibited an average accuracy of 97.1429%, an FAR of 1.0526%, and an FRR of 5.2632%. Self-1 exhibited an average accuracy of 97.7444%, an FAR of 1.0526%, and an FRR of 3.8596%. Finally, Artificial-1 showed an average accuracy of 97.7444%, FAR of 1.3158%, and FRR of 3.5088%. When the quartile was used to determine the threshold, the average accuracy decreased slightly or was equal to the median; however, the FAR was maintained at approximately 1%. In the Artificial-1 case, when the median threshold was employed, the FAR and FRR were both approximately 1%. Therefore, to evaluate other factors, we used the strategy of determining the threshold as a quartile. These results suggest that high authentication accuracy can be achieved even with artificially generated EOG data, without using the users’ EOG data.

Table 1.

Comparison of performance for deciding threshold by median or quartile

| Method | Enrollment trials | Accuracy (%) | FAR (%) | FRR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Self-3 | 98.045 ± 1.917 | 2.631 ± 3.483 | 1.052 ± 2.497 |

| Self-1 | 97.744 ± 2.249 | 3.157 ± 2.986 | 1.052 ± 2.497 | |

| Artificial-1 | 97.744 ± 2.621 | 2.631 ± 3.483 | 1.754 ± 4.890 | |

| Quartile | Self-3 | 97.142 ± 3.563 | 1.052 ± 2.094 | 5.263 ± 6.877 |

| Self-1 | 97.744 ± 3.097 | 1.052 ± 2.094 | 3.859 ± 5.584 | |

| Artificial-1 | 97.744 ± 3.240 | 1.315 ± 2.262 | 3.508 ± 6.428 |

The accuracies, FARs, and FRRs of template sets with different sizes were compared. The template sets were built with EOG data from 18 participants; however, we also assessed the performance when the templates were built with only 16 participants. When a specific participant was assumed to be the user, two participants who were randomly selected from 18 participants were excluded from the template set. These results are shown in the ‘User’ row in Table 2; the result from 18 participants is shown in the ‘Quartile’ row in Table 1. The performance remained the same for all enrollment conditions, except for the Self-1 condition, in which the average accuracy and FRR were slightly reduced.

Table 2.

Comparison of performance for fitting threshold with user’s incorrect trials and other’s incorrect trials

| Method | Enrollment trials | Accuracy (%) | FAR (%) | FRR (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| User | Self-3 | 97.142 ± 3.563 | 1.052 ± 2.094 | 5.263 ± 6.877 |

| Self-1 | 97.894 ± 2.987 | 1.052 ± 2.094 | 3.508 ± 5.607 | |

| Artificial-1 | 97.744 ± 3.240 | 1.315 ± 2.262 | 3.508 ± 6.428 | |

| Other | Self-3 | 97.142 ± 3.688 | 0.526 ± 1.576 | 5.964 ± 7.979 |

| Self-1 | 97.142 ± 2.332 | 1.052 ± 2.094 | 5.263 ± 5.699 | |

| Artificial-1 | 96.992 ± 3.495 | 1.578 ± 2.387 | 4.912 ± 7.647 |

Table 2 also compares the results when the threshold was fit with only user’s correct and incorrect trials (‘User’ row) or fit with correct trials of the user and incorrect trials of other participants who were randomly selected (‘Other’ row). The former required seven user trials to fit the threshold, whereas the latter required only three user trials for the fitting threshold stage. The differences in the accuracy, FAR, and FRR between the two conditions were 0.752%p, 0.526%p, and 1.755%p, respectively. These results suggest that the decrease of the system performance was not high, even when the incorrect trials of the other participants were used instead of the user’s incorrect trials.

For the comparison with the conventional studies, EER was computed for three different enrollment conditions. The EER values for the Self-3, Self-1, and Artificial-1 conditions were 3.5088%, 3.5088%, and 3.8509%, respectively. The EER values did not exceed 4% under any condition.

The computation time for each input data was 1.92 s (Intel Core i7 8700, DDR4 32 GB), which shows that our method requires fairly low computational power for the entire process because there is no matrix decomposition or basis vector induction. The highest accuracy was 98.0451%, which was achieved when three trials were used for enrollment, and the threshold was determined using the median within the range of the maximum fitting accuracy.

Discussion

Our results showed that only three trials of eye-written patterns were sufficient to register passwords using the proposed method. Because no steps for neural network training or machine learning are necessary, the proposed authentication method is light enough to apply to a mobile device or stand-alone VR HMD, examples of which include Meta Quest2 and PICO4. The proposed authentication method provides a reliable and intuitive way for users to log into their accounts with high reliability, without any movement of the body or hands, except for the eyes. Moreover, because the VR HMD is blocked in front, as depicted in Fig. 2b, and only the user’s eyes move, there is no concern of peeping or leaking the password to observers during the authentication process.

The performance of the proposed method was assessed by assuming that one of the five test patterns used in this study served as a password. This approach was used to ensure consistency across all participants and to align with the LOSO-CV strategy. However, any eye-written pattern in the test and template pattern sets can be used as a password in the proposed method.

When incorrect trials of other participants were used to fit the threshold, the FAR decreased, and the FRR increased when the accuracy was the same. When the accuracy was the same, using incorrect trials of other participants to fit the threshold might pull the advantage of rejection against the wrong attempt and pull the tight decision against the right attempt.

The EOG signals obtained from the authentication attempt were processed through two transformation steps. First, the raw signals from the four channels were converted into a two-dimensional trajectory representing saccadic eye movements, followed by normalization. At this stage, the trajectory closely resembles the ideal pattern that the user eye-wrote. Second, this trajectory was transformed into a ten-dimensional vector known as the similarity vector. As detailed in Appendix B, the value of the th element of the similarity vector increases if the attempted pattern is similar to the th template pattern. Therefore, the similarity vector is nearly unique for different patterns. In summary, the variation originating from individual participants was relatively lower than that from individual patterns.

If a snap-to-grid method is applied, the type of authentication is converted into a keycode. There is no need for an acceptable range of correct attempts against password patterns, and the performance will improve. However, because the EOG characteristics differ for each person, distortion or skewness of eye-written patterns can occur, which is difficult to overcome [27]. In future research, we will use real-time biofeedback when a user eye-writes a pattern.

Despite the carefully designed experiment paradigm, the proposed study could entail some potential for bias, as all EOG recordings from a single participant were conducted in one time. To address this issue, the reliability of the test–retest procedure needs to be investigated in future research, considering the application of the proposed method in real-world scenarios.

Previous studies reported the performances of their methods. Luo et al. [21], who used EOG signals recorded as unconscious responses to external visual stimuli, reported an EER of 5.75% for 3-s stimuli. When camera-based eye-trackers were used for authentication, Iskander et al. [11] achieved an accuracy below 90% and George et al. [12] reported an error rate of 6.94%. Compared with these methods, the proposed method achieved an accuracy of 97.74%, with an FAR of 1.31% and FRR of 3.50%. The EER of the proposed method did not exceed 3.8509%. Although the environment and methodology cannot be directly compared, the performance of the proposed method is remarkable.

Conclusions

In this study, a novel user authentication method was developed for VR applications based on eye-written patterns identified from EOG. The proposed EOG-based authentication system can be readily combined with existing VR HMD by simply replacing the electrode-embedded face-pad with an existing face-pad, which can dramatically reduce the overall price of the system. In addition, using DPW, the proposed method did not depend on the time or speed of the eye-writing pattern. Our system exhibited high accuracy and low FAR and FRR values, implying that the proposed user authentication method can be used in practical scenarios. It is expected that the proposed method can be used as a next-generation authentication method in a VR HMD environment after further research to improve its robustness and test–retest reliability.

Appendix

A. Measures for the security level of a biometric system

The performance of a biometric system is primarily defined by its security level, and three measures are frequently employed to evaluate the performance of a system:

False acceptance rate (FAR) is the frequency of unauthorized access instances caused by individuals falsely claiming an identity that is not their own.

False rejection rate (FRR) is the frequency of rejection of individuals who should be accurately verified.

Error equal rate (EER), at which both the FAR and FRR attain identical values, can be employed as a distinctive metric to characterize the security level of a biometric system.

Several preliminary studies formulated probabilistic definitions of these measures and demonstrated a fundamental relationship between measures [28, 29]. In this study, the proposed method distinguished eye-written patterns, not users; therefore, the imposters were incorrect patterns, and the authentics were password patterns. Therefore, the FAR and FRR were defined as

| 2 |

| 3 |

respectively, where denotes false negative, denotes true positive, denotes false positive, and denotes true negative. The FAR and FRR depend on the threshold , which was determined in the fitting threshold stage in this study.

B. Each class of template constructs one or fewer dimensions

Let there be ten distinguishable classes that are template patterns . For one of pattern such that , the vector can be calculated from DPW values with every element of template set.

| 4 |

where th component is evaluated by averaging all DPW values with elements of th class of template set, where is an integer of .

Because the output of DPW is a positive real value, which increases when the calculated two patterns are completely different, there is a real number that has significantly arithmetic difference between and , where .

| 5 |

| 6 |

By subtracting constant , which is

| 7 |

| 8 |

the th component of vector is remarkably large, and the other components are relatively close to zero.

Because the space in is an -dimensional real space, the vector field and space are well defined.

C. Patterns provided to participants in this study

Author contributions

HyunSub Kim conducted overall data analysis and wrote a first draft of the manuscript. HyunSub Kim, Chunghwan Kim, and Chaeyoon Kim conducted material preparation, data collection. Study conception and design were performed by HyunSub Kim, Chunghwan Kim, Chaeyoon Kim, HwyKuen Kwak, and Chang-Hwan Im. Chang-Hwan Im provided important insight for the design of the paper and revised the manuscript. All authors listed have contributed considerably to this paper and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by Korea Research Institute for defense Technology planning and advancement (KRIT)—Grant funded by Defense Acquisition Program Administration (DAPA) (KRIT-CT-21-027).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Ethical approval

The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Hanyang University, Republic of Korea (IRB No. HYUIRB-202209-024-1).

Consent to participate

All participants signed a written consent after being informed of the experimental protocol.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Fig. 2b.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fan X, Jiang X, Deng N. Immersive technology: a meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tour Manag. 2022;91: 104534. 10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104534. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman G, Zamanifard S, Maloney D, Adkins A. My body, my avatar: How people perceive their avatars in social virtual reality. In: Proc Conf CHI. Honolulu HI USA; 2020. p. 1–8.

- 3.Mittal A. E-commerce: it’s Impact on consumer Behavior. Glob J Manag Bus Stud. 2013;3:131–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.George C, Khamis M, Zezschwitz EV, Burger M, Schmidt H, Alt F, Hussmann H. Seamless and secure VR: adapting and evaluating established authentication systems for virtual reality. In Proc Workshop Usable Secur. San Diego CA USA; 2017. p. 1–12.

- 5.Olade I, Liang H-N, Fleming C. Exploring the vulnerabilities and advantages of SWIPE or pattern authentication in virtual reality (VR). In Proc ICVARS. Sydney NSW Australia; 2020. p. 46–52.

- 6.Singh N, Agrawal A, Khan RA. Voice biometric: a technology for voice based authentication. Adv Sci Eng Med. 2018;10:754–9. 10.1166/asem.2018.2219. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen Y, Wen H, Luo C, Xu W, Zhang T, Hu W, Rus D. Gaitlock: protect virtual and augmented reality headsets using gait. IEEE Trans Depend Secure Comput. 2019;16:484–97. 10.1109/TDSC.2018.2800048. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gafurov D, Snekkenes E, Bours P. Spoof attacks on gait authentication system. IEEE Trans Inf Forensics Secur. 2007;2:491–502. 10.1109/TIFS.2007.902030. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar M, Garfinkel T, Boneh D, Winograd T. Reducing shoulder-surfing by using gaze-based password entry. In Proceedings of the 3rd symposium on Usable privacy and security. Pittsburgh PA USA; 2007. p. 13–19.

- 10.Mathis F, Williamson J, Vaniea K, Khamis M. RubikAuth: fast and secure authentication in virtual reality. In Extended Abstracts of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Honolulu HI USA; 2020. p. 1–9.

- 11.Iskander J, Abobakr A, Attia M, Saleh K, Nahavandi D, Hossny M, Nahavandi S. A k-NN Classification based VR user verification using eye movement and ocular biomechanics. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC). Bari Italy; 2019. p. 1844–1848.

- 12.George C, Buschek D, Ngao A, Khamis M. GazeRoomLock: Using gaze and head-pose to improve the usability and observation resistance of 3d passwords in virtual reality. In Proc AVR. Lecce Italy; 2020. p. 61–81.

- 13.Barbara N, Camilleri TA, Camilleri KP. EOG-based eye movement detection and gaze estimation for an asynchronous virtual keyboard. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2019;47:159–67. 10.1016/j.bspc.2018.07.005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang WD, Cha HS, Kim DY, Kim SH, Im CH. Development of an electrooculogram-based eye-computer interface for communication of individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2017;14:89. 10.1186/s12984-017-0303-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moinnereau M-A, Oliveira A, Falk TH. Saccadic eye movement classification using ExG sensors embedded into a virtual reality headset. In Proc IEEE Conf SMC. Toronto ON Canada; 2020. p. 3494–3498.

- 16.Zao JK, Jung T-P, Chang H-M et al. Augmenting vr/ar applications with eeg/eog monitoring and oculo-vestibular recoupling. In Proc Int Conf Augmented Cognition; 2016. p. 121–131.

- 17.Shimizu J, Chernyshov G. Eye movement interactions in Google cardboard using a low cost EOG setup. In Proc ACM Int Conf UbiComp. Heidelberg Germany; 2016. p. 1773–1776.

- 18.Gjoreski H, Mavridou II, Fatoorechi M, Kiprijanovska I, Gjoreski M et al. emteqPRO: face-mounted mask for emotion recognition and affective computing. In Proc ACM Int Conf UbiComp. New York NY USA; 2021. p. 23–25.

- 19.Cha HS, Im CH. Performance enhancement of facial electromyogram-based facial-expression recognition for social virtual reality applications using linear discriminant analysis adaptation. Virtual Reality. 2022;26:385–98. 10.1007/s10055-021-00575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cha HS, Chang WD, Im CH. Deep-learning-based real-time silent speech recognition using facial electromyogram recorded around eyes for hands-free interfacing in a virtual reality environment. Virtual Reality. 2022;26:1047–57. 10.1007/s10055-021-00616-0. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo S, Nguyen A, Song C, Lin F, Xu W, Yan Z. OcuLock: exploring human visual system for authentication in virtual reality head-mounted display. In Proc Annu Netw Distrib Syst Secur Symp. San Diego CA USA; 2020.

- 22.Li S, Savaliya S, Marino L, Leider AM, Tappert CC. Brain signal authentication for human-computer interaction in virtual reality. In Proc IEEE Int Conf CSE/EUC. New York NY USA; 2019. p. 115–120.

- 23.Pfeuffer K, Geiger MJ, Prange S, Mecke L, Buschek D, Alt F. Behavioural biometrics in vr: identifying people from body motion and relations in virtual reality. In Proc Conf CHI. New York NY USA; 2019. p. 110.

- 24.Bulling A, Ward JA, Gellersen H, Tröster G. Eye movement analysis for activity recognition using electrooculography. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2011;33:741–53. 10.1109/TPAMI.2010.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang WD, Shin J. Dynamic Positional warping: dynamic time warping for online handwriting. Int J Pattern Recognit Artif Intell. 2009;23:967–86. 10.1142/S0218001409007454. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogiela MR, Ogiela L. Eye movement patterns as a cryptographic lock. In Proc INCoS-2020. Victoria Canada; 2021. p. 145–148.

- 27.Wang J-G, Sung E. Study on eye gaze estimation. IEEE Trans Syst Man Cybern. 2002;32:332–50. 10.1109/TSMCB.2002.999809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golfarelli M, Maio D, Malton D. On the error-reject trade-off in biometric verification systems. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 1997;19:786–96. 10.1109/34.598237. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daugman J. Biometric decision landscapes. Univ Cambridge Comput Lab. https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/techreports/UCAM-CL-TR-482.pdf. Accessed Jan 2000.