Abstract

Background

Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and mobile health (mHealth) applications have revolutionized the healthcare landscape in the areas of remote patient monitoring (RPM) and digital therapeutics (DTx). These technological advancements offer a range of benefits, from improved patient engagement and real-time monitoring, to evidence-based personalized treatment plans, risk prediction, and enhanced clinical outcomes.

Objective

The systematic literature review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the status of SaMD and mHealth apps, highlight the promising results, and discuss what is the potential of these technologies for improving health outcomes.

Methods

The research methodology was structured in two phases. In the first phase, a search was conducted in the EuropePMC (EPMC) database up to April 2024 for systematic reviews on studies using the PICO model. The study population comprised individuals afflicted by chronic diseases; the intervention involved the utilization of mHealth solutions in comparison to any alternative intervention; the desired outcome focused on the efficient monitoring of patients. Systematic reviews fulfilling these criteria were incorporated within the framework of this study. The second phase of the investigation involved identifying and assessing clinical studies referenced in the systematic reviews, followed by the synthesis of their risk profiles and clinical benefits.

Results

The results are rather positive, demonstrating how SaMDs can support the management of chronic diseases, satisfying patient safety and performance requirements. The principal findings, after the analysis of the extraction table referring to the 35 primary studies included, are: 24 studies (68.6%) analyzed clinical indications for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), six studies (17.1%) analyzed clinical indications for cardiovascular conditions, three studies (8.7%) analyzed clinical indications for cancer, one study (2.8%) analyzed clinical indications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and one study (2.8%) analyzed clinical indications for hypertension. No severe adverse events related to the use of mHealth were reported in any of them. However, five studies (14.3%) reported mild adverse events (related to hypoglycemia, uncontrolled hypertension), and four studies (11.4%) reported technical issues with the devices (related to missing patient adherence requirements, Bluetooth unsuccessful pairing, and poor network connections). For what concerns variables of interest, out of the 35 studies, 14 reported positive results on the reduction of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) with the use of mHealth devices. Eight studies examined health-related quality of life (HRQoL); in three cases, there were no statistically significant differences, while the groups using mHealth devices in the other five studies experienced better HRQoL. Seven studies focused on physical activity and performance, all reflecting increased attention to physical activity levels. Six studies addressed depression and anxiety, with mostly self-reported benefits observed. Four studies each reported improvements in body fat and adherence to medications in the mHealth solutions arm. Three studies examined blood pressure (BP), reporting reduction in BP, and three studies addressed BMI, with one finding no statistically significant change and two instead BMI reduction. Two studies reported significant weight/waist reduction and reduced hospital readmissions. Finally, individual studies noted improvements in sleep quality/time, self-care/management, six-minute walk distance (6MWD), and exacerbation outcomes.

Conclusion

The systematic literature review demonstrates the significant potential of software as a medical device (SaMD) and mobile health (mHealth) applications in revolutionizing chronic disease management through remote patient monitoring (RPM) and digital therapeutics (DTx). The evidence synthesized from multiple systematic reviews and clinical studies indicates that these technologies, exemplified by solutions like Healthentia, can effectively support patient monitoring and improve health outcomes while meeting crucial safety and performance requirements. The positive results observed across various chronic conditions underscore the transformative role of digital health interventions in modern healthcare delivery. However, further research is needed to address long-term efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and integration into existing healthcare systems. As the field rapidly evolves, continued evaluation and refinement of these technologies will be essential to fully realize their potential in enhancing patient care and health management strategies.

Keywords: Healthentia, remote patient monitoring (RPM), digital therapeutics (DTx), software as medical device (SaMD), chronic diseases

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) and mobile health (mHealth) applications have revolutionized the healthcare landscape in the areas of remote patient monitoring (RPM) and digital therapeutics (DTx). These technological advancements offer a range of benefits, from improved patient engagement and real-time monitoring to personalized treatment plans and enhanced clinical outcomes.

The current landscape of SaMD and mHealth apps is characterized by rapid innovation and widespread adoption, especially after the Covid pandemic, which might have worked as a catalyst for digital health transformation. SaMD refers to software intended to be used for medical purposes without being part of a hardware medical device. mHealth applications; on the other hand, they encompass a wide range of digital tools designed to support health and wellness through mobile devices. mHealth applications are not necessarily medical devices and, therefore, they often do not comply with the regulatory framework. Both SaMD and mHealth apps have seen significant advancements, driven by the increasing need for accessible, efficient, and patient-centric healthcare solutions. Regulatory frameworks have also evolved to keep pace with these innovations, ensuring that these technologies meet the rigorous safety and efficacy standards. While the potential of SaMD and mHealth apps are immense, there are several challenges that need to be addressed to completely realize their benefits, such as data privacy concerns, integration with existing healthcare systems, and user adoption barriers.

The industrial outlook for remote patient monitoring (RPM) solutions shows significant growth potential as the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease necessitate continuous monitoring. Advances in wearable technology and biosensors have revolutionized the RPM landscape, offering accurate, user-friendly, and cost-effective solutions. The shift toward value-based care models, which emphasize patient outcomes and cost efficiency over service volume, aligns with the capabilities of RPM systems. Investment trends indicate robust financial backing for RPM innovations and market forecasts predict sustained growth, with the global RPM market projected to expand significantly over the next decade. This expansion is supported by the rising adoption of telemedicine, advancements in artificial intelligence and data analytics, and the growing consumer demand for personalized healthcare solutions (1, 2).

1.2. Healthentia SaMD

Healthentia is a software intended for: a) the collection and transmission of physiological data including heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and weight directly to care providers via automated electronic means in combination with validated IoT devices; b) the visualization (subjects-based dashboards) and the mathematical treatment of data (trends analysis, alerts) related to the monitored chronic disease subject’s physiological parameters; c) the transmission of patient’s outcomes and outcome scores related to patient’s health status, health-affecting factors, health-related quality of life, disease knowledge and adherence to treatment through validated questionnaires; d) the user (subject/patient) interaction with a conversational virtual coach for informative and motivational purposes, in order to support subject telemonitoring, decision making and virtual coaching (52, 53).

The Healthentia platform and its two front-end applications, the Healthentia mobile application for the subjects and the portal application for the healthcare professionals, is a standalone software [Software as a Service (SaaS)] medical active device. The platform consists of a collection of medical and non-medical modules. Medical modules are intended to collect, visualize, and compute patient’s physiological parameters to support the monitoring of the patient, decision-making during clinical trial, or under a medical treatment context. It is considered as a medical device because it is a software intended by the manufacturer to be used for diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, risk prediction, or prognosis of disease and does not achieve its principal intended action by pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic means.

The Healthentia platform is currently classified as Class IIa device per Rule 11 of Annex VIII of the Medical Device Regulation 2017/745 as amended. Based on the medical modules of Healthentia, healthcare professionals (HCPs) can monitor patients, causing an increased follow-up of the patients, which leads to good adherence to treatment.

Gathering information on lifestyle in a robust manner and collecting physiological parameters in real time continuously allows lifestyle elements to be aggregated into actionable inputs for diagnostic and patient management support.

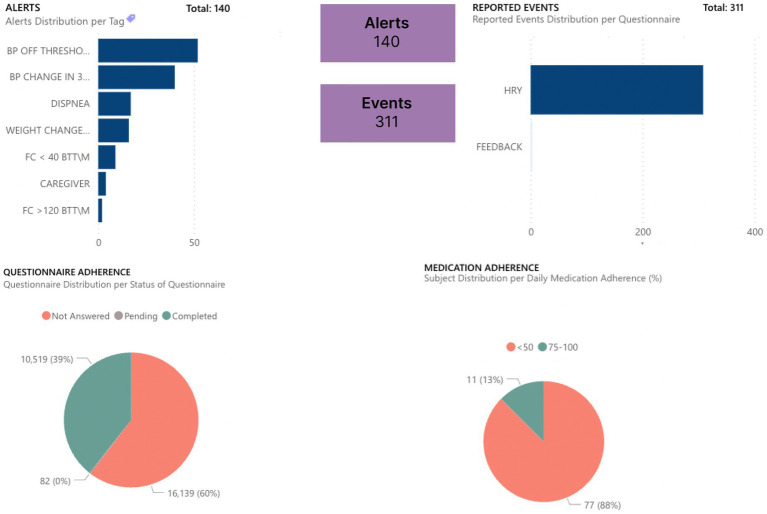

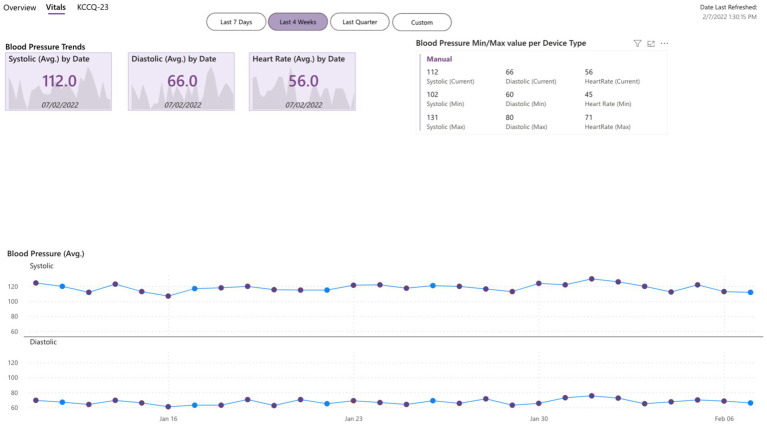

The gathered data are more objective than feedback given by the patient at one moment (during an office or virtual appointment with HCPs) because they are quantifiable data (e.g., heart rate) over a long period. Moreover, these data are reported in graphs by Healthentia, which are objective and more easily interpretable by the HCPs, allowing a more evidence-based individualized decision-making, as presented in Figures 1, 2.

Figure 1.

Dashboard for follow-up monitoring of patients.

Figure 2.

Dashboard of objective inputs for healthcare professionals.

Healthentia is compatible with different supported devices to collect lifestyle information and vital signs, as grouped in Table 1 based on the objective data and their source.

Table 1.

Objective data from patients.

| Type | Measurements | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Activity | Steps walked, distance traveled, calories burned, floors climbed, minutes in different activity intensity zones | Activity trackers |

| Exercise sessions (type, start time, duration, calories) | Activity trackers | |

| Sleep | Sleep start, sleep end, minutes in different sleep zones | Activity trackers |

| Vitals | Blood pressure | Integrated Internet of Things (IoT) devices |

| spO2 | Integrated IoT devices | |

| Weight | Integrated IoT devices | |

| Heart (resting heart rate, max heart rate, minutes in different heart rate zones, heart rate variability) | Activity trackers |

Healthentia indicates whether the Internet of Things (IoT) device has acceptable accuracy for the intended purpose or if it does not have acceptable accuracy and can only be used for measurements that do not require accuracy (e.g., step counter, sleep). The accuracy requirements for IoT devices that are connected to Healthentia are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Minimum accuracy of devices.

| Measurement | Min. accuracy |

|---|---|

| Blood pressure | ≤10 mmHg (at least 85% probability) |

| spO2 | Arms ±2–3% of arterial blood gas values |

| Heart (resting heart rate (RHR), max) | ±10% of the input rate or ± 5 bpm (beats per minute) |

| Weight | ±0.5–1.0 kg |

| Physical activity (steps) | n/a |

| Sleep | n/a |

These devices constitute a safe combination and currently there is no device-specific information on any known restrictions to combinations. Furthermore, trend analysis is done by plotting the data collected over a period. This is made possible by Healthentia and supports a diagnostic decision for the healthcare professional.

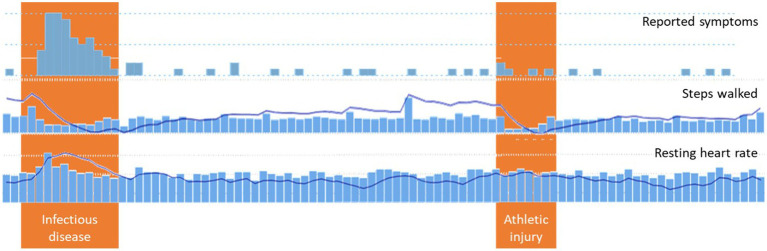

An example of trend analysis is shown in Figure 3, which contains screenshots of reported symptoms such as volume (indication of study commitment), measurements of steps walked, and vital measurements such as the resting heart rate, as well as their trends. The reported period includes two adverse events: an infectious disease and an athletic injury. During both events, the trend of the steps indicates a severe drop from the walking habit. But the trend of the resting heart rate indicates a worsening of that vital parameter over the established value only for the case of the infectious disease, as this vital parameter is not affected by the injury. In times other than the two events, the trends slowly recover to indicate the expected situation (normality) for the given patient.

Figure 3.

Trends analysis.

Healthentia further to the RPM capabilities described above; it is an advanced DTx solution that aims to improve patients’ lifestyle using a novel behavioral change framework that includes techniques like goal setting and monitoring, offering visualizations of the patients’ data, and discussing aspects of risky behaviors with them. The behavioral change techniques use the chatbot functionality to provide a virtual coaching experience to the patients. While the dialogs are selected when certain conditions arise, they are personalized, since the content delivered is augmented with actual patient data. The data used for personalization can be simple, for example, static pieces of information like the patient’s name or sex. It can also be some personalized goals set for the patient by a doctor. Finally, it can be the results of statistics on some data of the patient, like the average steps walked in the past week, or the frequency red meat is consumed in the past month. This way actual patient data can be compared to the personalized goals, while the patient is addressed by name. Employing the existing features in the dialogs and looking ahead to more dynamic options, Healthentia can keep the patients interested, since the dialogs are dynamic, personalized, and offer two-way exchange of information, both from Healthentia to the patient, but also from the patient to Healthentia.

1.3. Objectives

During the continuous design, development, and validation of the medical device Healthentia, a systematic literature review has been conducted to assess the status and efficacy of these digital health interventions and benchmark the results with findings and clinical evidence collected from various studies.

The systematic literature review involved a scientific process of identifying, selecting, and analyzing relevant studies that evaluate the effectiveness of SaMD and mHealth apps in managing chronic diseases, using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study) framework. The selected studies provide a robust evidence base, highlighting the positive impact of these technologies on patient outcomes.

The systematic literature review provides a comprehensive overview of the current status of SaMD and mHealth apps, highlights promising results, and discusses the potential these technologies hold for improving health outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

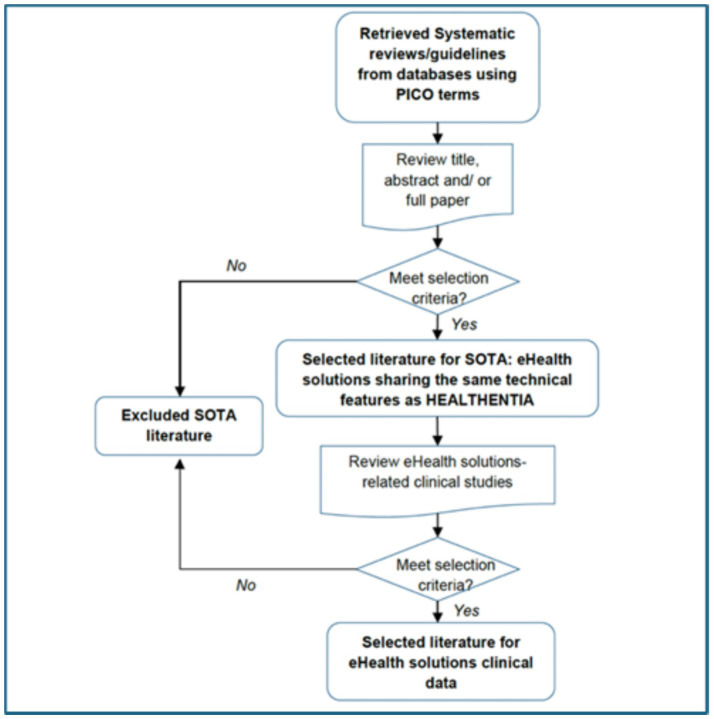

The research methodology was structured following a systematic approach as illustrated in Figure 4. Initially, a search was conducted in EuropePMC database up to April 2024 using the PICO model Schardt et al. (54):

Figure 4.

Strategy for state-of-the-art (SOTA) literature retrieval and screening process.

P—Patient, Population, or Problem: The study population comprised individuals afflicted with chronic diseases.

I—Intervention or Exposure: The intervention involved the utilization of mHealth solutions.

C—Comparison or Control: The comparison is to any alternative intervention.

O—Outcome: The desired outcome focused on the efficient monitoring of patients.

The search protocol was not limited to EuropePMC and its full description was:

Search on EuropePMC (52)

-

Appraise the detected articles

If data are not sufficient, extend the search to Cochrane.

If data are still not sufficient, extend the search to PubMed with a focus on “mHealth” and publications for the last 3 years.

If data are still not sufficient, use alternative terms for the technology or the medical subject headings (MeSH) term “Telemedicine.”

If data are still not sufficient, search for clinical studies and not only for systematic reviews.

Regarding the subject-specific databases, there were no such databases considered, as the target was a broad scope of indications.

The systematic reviews fulfilling these criteria were incorporated within the framework of this study, which is presented in Figure 4. Five different queries were formulated concerning five specific chronic conditions, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer(s), heart failure, and cardiovascular diseases:

Search query for diabetes: ((“e-Health” OR “mHealth” OR “RPM” OR “Telehealth” OR “Internet of Things”) AND (TITLE:diabetes) AND (TITLE:"Systematic Review”))

Search query for COPD: ((“e-Health” OR “mHealth” OR “RPM” OR “Telehealth” OR “Internet of Things”) AND (TITLE:COPD) AND (TITLE:"Systematic Review”))

Search query for cancer: ((“e-Health” OR “mHealth” OR “RPM” OR “Telehealth” OR “Internet of Things”) AND (TITLE:cancer) AND (TITLE:"Systematic Review”))

Search query for heart failure: ((“e-Health” OR “mHealth” OR “RPM” OR “Telehealth” OR “Internet of Things”) AND (TITLE:"heart failure”) AND (TITLE:"Systematic Review”))

Search query for cardiovascular diseases: ((“e-Health” OR “mHealth” OR “RPM” OR “Telehealth” OR “Internet of Things”) AND (TITLE:"cardiovascular”) AND (TITLE:"Systematic Review”))

The second phase of the investigation involved identifying and assessing clinical studies referenced in the Systematic Reviews, followed by the synthesis of their risk profiles and clinical benefits.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the studies involved in this research focused on monitoring chronic diseases using devices similar to Healthentia, with a control group for comparison to gather clinical data. Studies primarily centered on economic aspects without relevance to mHealth solutions or chronic diseases were excluded from consideration, as indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| PICO reference | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Chronic disease monitoring | Other pathologies management |

| Intervention | Report use of similar devices | Evaluation of other management methods without comparison to e-Health solution |

| Comparison | Comparative study (with control group) | NA |

| Outcome | Reported clinical benefits for patients | Economic considerations |

2.3. Screening of articles

Concerning the screening of the articles, the title, abstract and full article, as applicable, were screened and verified for meeting the inclusion and exclusion selection criteria. In case the selection criteria are met, the articles are included to establish the state-of-the-art. When the included articles contained clinical data on e-health solutions substantiated by referenced articles, those publications were screened to retrieve detailed clinical study information (clinical indications, number of patients, device used, performance data, and side-effects). Screening was performed by title, abstract, and full article analysis based on the selection criteria. In case the selection criteria were met, the clinical studies containing performance and safety data were included for analysis.

2.4. Study selection

Four independent researchers (S.K., A.P., L.F., K.K.) initially screened the titles and abstracts resulting from the five aforementioned queries. Subsequently, pertinent full texts from the previously accepted studies were incorporated by the same team. Following this inclusion, a hand search for device-related studies within the references of the systematic reviews identified during the initial screening was conducted. The key findings were mainly randomized control trials assessing mHealth solutions with functionalities similar to those of Healthentia.

2.5. Data extraction

Two extraction tables were developed as part of the research process. The first extraction table, concerning systematic reviews resulting from the search queries, contained essential details such as title, authors, journal of publication, publication year, DOI, along with clinical performance data and conclusions collected from meta-analyses. Following the manual search process mentioned earlier, a second extraction table was created to compile more specific information from the referenced primary studies. This table included details such as title, authors, publication year, DOI, clinical indication, study type, device type and name, patient numbers in both device and control groups, as well as data on HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin), blood pressure, LDL-c (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), (HR) QoL (health-related quality of life), weight/waist measurements, exacerbations, 6MWD (six-minute walk distance), adherence rates, hospital readmissions, self-care/management practices, depression and anxiety assessments, physical activity levels, sleep patterns, adverse events, complications, and conclusions drawn from the gathered information.

2.6. Limitations of the study

The methodological decision to exclusively gather systematic reviews derived from the search queries conducted on a single database was a necessary choice driven by time limitations. Nonetheless, this approach may have introduced a potential selection bias, given that the scope of studies available for data collection was inevitably narrower in comparison to the broader spectrum present in the literature, considering the major interest in the findings of primary studies that collected the necessary information.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the included studies

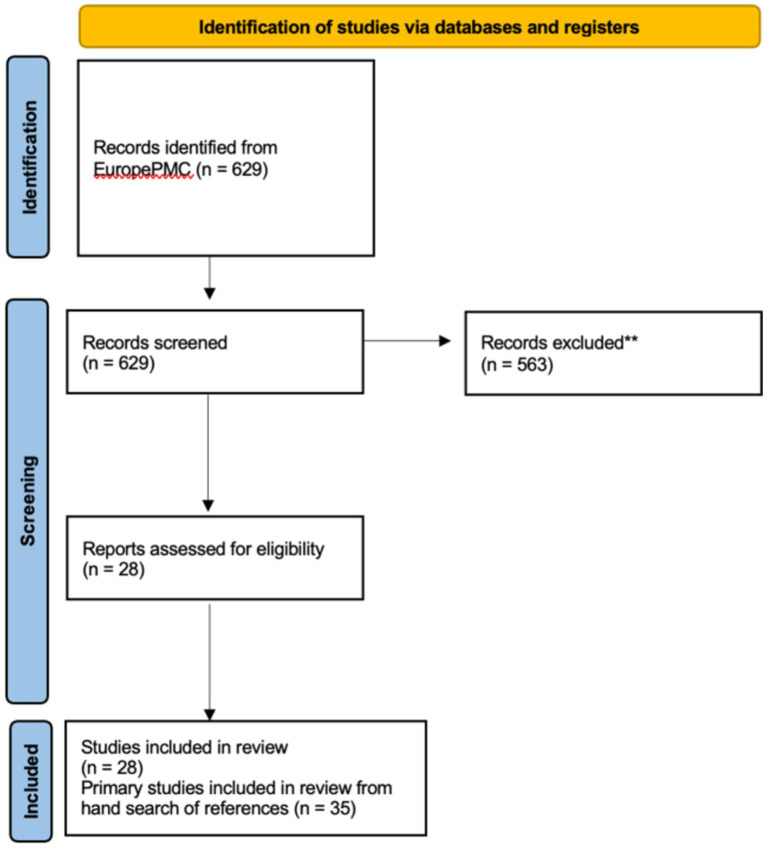

The EuropePMC research resulted in 629 records. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 563 records were deemed irrelevant and excluded. Subsequently, 28 systematic reviews were included after a full-text examination. Within these 28 records, references were reviewed manually to identify key primary studies on mHealth solutions. Initially, 116 sets of clinical data were considered relevant. However, after a detailed review of full texts, the number of pertinent studies was refined down to 35 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flow chart of literature search [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020].

Table 4 summarizes data extracted from the first step of the search strategy (systematic reviews, results from meta-analysis: 14 records) and Table 5 summarizes data extracted from the second step of the search strategy (primary studies: 35 records).

Table 4.

Clinical performance of eHealth solutions (systematic reviews/meta-analyses results).

| References | Condition | Clinical performance | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| de Souza et al. (3) | Type II diabetes (T2DM) | HbA1c: Use of mobile applications reduced HbA1c in 0.39% (CI 0.24–0.54) | The use of mobile applications can help reduce glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) by 0.39% compared to the usual care group |

| Lee et al. (4) | Type II diabetes | Significant benefits:

|

Among older adults with T2DM, mHealth interventions were associated with improved cardiometabolic outcomes versus usual care |

| Kim et al. (5) | Type II diabetes | Significant benefits:

|

Digital healthcare technology can improve HbA1c and triglyceride levels of type 2 diabetes patients |

| He et al. (6) | Type II diabetes | Significant benefits:

|

Smartphone application–based diabetes self-management intervention could optimize patients’ glycaemic control and enhance participants’ self-management performance |

| Liu et al. (7) | Type II diabetes | Significant benefits:

|

Mobile app-assisted self-care interventions can be an effective tool for managing blood glucose and blood pressure, likely because their use facilitates remote management of health issues and data, provision of personalized self-care recommendations, patient–care provider communication, and decision-making |

| Masotta et al. (8) | Heart disease | Significant benefits in studies describing the remote transmission of patient’s physiologic parameters:

|

The review confirms the benefits of telemonitoring in reducing rehospitalizations of heart failure (HF) patients |

| Kitsiou et al. (9) | Heart disease | Significant benefits:

|

mHealth interventions with remote monitoring and clinical feedback reduce mortality and HF-related hospitalizations, but might not reduce all-cause hospitalizations in patients with HF |

| Uminski et al. (10) | Heart disease | Significant benefits [post-discharge Virtual Ward (VW)]

Do not reduce death or hospital readmissions for patients with undifferentiated high-risk chronic diseases |

A post-discharge VW can provide added benefits to usual community-based care to reduce all-cause mortality and heart failure-related hospital admissions among patients with heart failure |

| Jaén-Extremera et al. (11) | Heart disease | Significant benefits:

|

For all the risk factors, a small effect of the telemedicine was seen |

| Cruz-Cobo et al. (12) | Heart disease | Significant benefits:

|

mHealth technology has a positive effect on patients who have experienced a coronary event in terms of their exercise capacity, physical activity, adherence to medication, and physical and mental quality of life, as well as readmissions for all causes and cardiovascular causes |

| Patterson et al. (13) | Heart disease | Significant benefits:

|

Smartphone applications were effective in increasing physical activity in people with cardiovascular disease. Caution is warranted for the low-quality evidence, small sample, and larger coronary heart disease representation |

| Lu et al. (14) | COPD | Significant benefits:

|

The implementation of telemedicine intervention is a potential protective therapeutic strategy that could facilitate the long-term management of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD) |

| Jang et al. (15) | COPD | Significant benefits:

|

Adding telemonitoring to the usual care for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) may reduce unnecessary ER visits but is unlikely to prevent hospitalizations from COPD exacerbations |

| Buneviciene et al. (16) | Cancer | Significant benefits:

|

The majority of studies (15 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 7 pre-post designs) found that mHealth interventions were associated with improvement in at least one domain of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of cancer patients |

Table 5.

Clinical performance of eHealth solutions (references of systematic reviews included).

| Reference | Clinical indication | Study type | Device under evaluation | Patients (eHealth solution) | eHealth solution—clinical performance | Side-effects, complications related to eHealth solution | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holmen et al. (17) | Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) | Prospective randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Few Touch Application (FTA) (diary app, glucometer, food habit registration system, physical activity registration system, a personal goal setting system, and a general information system) | 39 to the FTA group, 40 to the FTAhealth counseling (FTA-HC) group | HbA1c level decreased in all groups, but did not differ between groups after 1 year. The mean change in the heiQ domain skills and technique acquisition was significantly greater in the FTA-HC group after adjusting for age, gender, and education (p = 0.04) |

|

|

| Karhula et al. (18) | T2DM | RCT | eClinic (Medixine Ltd) [information content, health parameters registered by the corresponding measurement devices, personal care plan entered by the health coach in agreement with the patient, and data obtained from the electronic health record (EHR)] | 175 heart patients and 162 diabetes patients |

|

None |

|

| Li et al. (19) | T2DM | RCT | R Plus Health app and chest strap for physical activity | 44 |

|

|

|

| Coombes et al. (20) | T2DM | RCT | Personal activity Intelligence Health app and wrist-worn heart rate monitor |

12 |

|

None

|

|

| Boer et al. (21) | COPD | RCT | Living Well with COPD [pulse oximeter, spirometer, forehead thermometer, questionnaires, advice (coaching)] | 36 | Exacerbations: no statistically significant differences between the intervention group and the control group in exacerbation-free weeks (mean 30.6, SD 13.3 vs. mean 28.0, SD 14.8 weeks, respectively; rate ratio 1.21; 95% CI 0.77–1.91) | None |

|

| Sun et al. (22) | T2DM | RCT | Glucometer connected via Bluetooth to mHealth app showing advice and reminders. Daily diet info. | 44 |

|

None |

|

| Chao Dyna et al. (23) | T2DM | RCT | Custom/unspecified app with questionnaires | 49 |

|

None |

|

| Huang et al. (24) | T2DM | Randomized two-arm pre-posttest control group | Medisafe app with questionnaires and reminders | 22 |

|

None |

|

| Zhai and Yu (25) | T2DM | RCT | Yutangyihu app: Connected glucose meter and diet advice, emotional management, and medication guidance | 60 |

|

None |

|

| Bailey et al. (26) | TD2M | Randomized, controlled feasibility study | MyHealthAvatar-Diabetes app | 9 |

|

|

|

| Patnaik et al. (27) | T2DM | RCT | Custom/ unspecified app | 33 |

|

None |

|

| Park et al. (28) | Advanced lung cancer undergoing chemotherapy | Pilot study | Aftercare app (questionnaires, chat, notifications, wearable device, portable pulse oximeter, thermometer, scale, and resistance bands for physical therapy) | 100 |

|

Not significant |

|

| Lim et al. (29) | T2DM | RCT | u-healthcare website | 50 |

|

Not significant |

|

| Pappot et al. (30) | Cancer | Interventional Study | Kræftværket app (questionnaires) | 10 (active treat.) 10 (post-treat.) | (HR)QoL: Significant increase in overall QoL after the 6-week period (global QoL: baseline 62.5, SD 22.3; after 6 weeks 80.8, SD 9.7; p = 0.04) | None |

|

| Yang et al. (31) | Cancer | RCT | Pain Guard app (questionnaires, reminders, reports, e-diary, real-time medication consultation, content) | 27 | (HR)QoL: No significant differences in baseline pain scores or baseline QoL scores between groups. Improvements in global QoL scores in the trial group were also significantly higher than those in the control group (p < 0.001) | Adverse reactions in the trial group (7/31) were lower than that in the control group (12/27), especially constipation, with significant differences (p = 0.01) | Pain Guard was effective for the management of pain in discharged patients with cancer pain, and its operability was effective and easily accepted by patients |

| Hansel et al. (32) | T2DM | RCT | Web-based program called Accompagnement Nutritionnel de l’Obésité et du Diabète (ANODE) | 52 |

|

Participants’ connections varied, with decreasing logins throughout the study | ANODE e-coaching program improved diet quality and cardiometabolic risk factors significantly |

| Katalenich et al. (33) | T2DM | RCT | Diabetes Remote Monitoring and Management System (DRMS) | 50 |

|

|

|

| Nagrebetsk et al. (34) | T2DM | Feasibility trial in primary care | t Diabetes app | 7 |

|

|

|

| Davoudi et al. (35) | HF | RCT | My Smart Heart (reminders, content, messages, frequently asked questions, daily recording of physical and psychological symptoms, vital signs, alerts) | 55 | (HR)QoL: Statistically significant differences in the mean scores of quality of life and its dimensions after the intervention, thereby indicating a better quality of life in the intervention group (p < 0.001) | None | Use of a smartphone-based app can improve the quality of life in patients with heart failure. The results of our study recommend that digital apps be used for improving the management of patients with heart failure |

| Clays et al. (36) | CHF | RCT | HeartMan (questionnaires, blood pressure monitor, weight scale, pill organizer, heart rate, galvanic skin response, skin temperature and activity tracking) | 34 |

|

None |

|

| Athilingam et al. (37) | HF | Feasibility study–RCT | HeartMapp (questionnaires, daily weighing, symptom assessment, responding to tailored alerts, vital sign monitoring, content) | 7 |

|

None |

|

| Park et al. (38) | HF | Feasibility study | RxUniverse prescribed HealthPROMISE and iHealth apps (content, reminders, questionnaires, blood pressure, weight) | 60 |

|

None |

|

| Wang et al. (39) | T2DM | RCT | Custom/ unspecified app | 60 |

|

None |

|

| Gunawardena et al. (40) | T2DM | RCT | Smart Glucose Manager (SGM) | 27 |

|

None |

|

| Kleinman et al. (41) | T2DM | RCT | Gather Health app | 44 |

|

None |

|

| Fukuoka et al. (42) | T2DM | RCT | mDPP mobile app | 30 |

|

None |

|

| Wayne et al. (43) | T2DM | RCT | Custom/unspecified app | 48 |

|

None |

|

| Pernille et al. (44) | Cardiac rehabilitation | RCT | Vett® (goal setting, reminders, questionnaires, weight, BP) | 55 |

|

None | Individualized follow-up for 1 year with an app significantly improved VO2peak, exercise performance and exercise habits, as well as self-perceived goal achievement, compared with a CG in patients post-CR. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups at follow-up in the other outcome measures evaluated |

| Johnston et al. (45) | MI | RCT | SUPPORT study (AstraZeneca) (e-diary, medication management, reminders, content, questionnaires) | 85 |

|

None |

|

| Persell et al. (46) | Hypertension | RCT | Hypertension Personal Control Program coaching app (questionnaires, blood pressure) | 144 |

|

None | Among individuals with uncontrolled hypertension, those randomized to a smartphone coaching app plus home monitor had similar systolic blood pressure compared with those who received a blood pressure tracking app plus home monitor. Given the direction of the difference in systolic blood pressure between groups and the possibility for differences in treatment effects across subgroups, future studies are warranted |

| Hilmarsdóttir et al. (47) | T2DM | RCT | SidekickHealth app | 15 |

|

None |

|

| Lee et al. (48) | T2DM | RCT | Switch application | 54 |

|

None |

|

| Yu et al. (49) | T2DM | RCT | Diabetes-Carer | 45 |

|

|

|

| Brath et al. (50) | T2DM | RCT (single-blinded) | Custom/ unspecified app | 53 |

|

None |

|

| Yang et al. (51) | T2DM | Cluster-RCT | Hicare smart K app | 145 |

|

None |

|

3.2. Validity and rigor

Concerning the validity and rigor of the selected articles, the literature search for the state of the art was intended to provide a global overview of the disease, the condition, the technology used, and to provide a baseline for the performance and safety profile. It was not intended to be extensive from a regulatory perspective. The study relied on the fact that the selected articles came from peer-reviewed journals and have been identified and selected through a well documented protocol.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal findings

After the analysis of the extraction table referring to the included 35 primary studies, 24 studies (68.6%) analyzed clinical indications for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), six studies (17.1%) analyzed clinical indications for cardiovascular conditions, three studies (8.7%) analyzed clinical indications for cancer, one study (2.8%) analyzed clinical indications for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and one study (2.8%) analyzed clinical indications for hypertension. No severe adverse events related to the use of mHealth were reported in any of them. However, five studies (14.3%) reported mild adverse events (related to hypoglycemia, uncontrolled hypertension) and four studies (11.4%) reported technical issues with the devices (related to missing patient adherence requirements, Bluetooth unsuccessful pairing, and poor network connections).

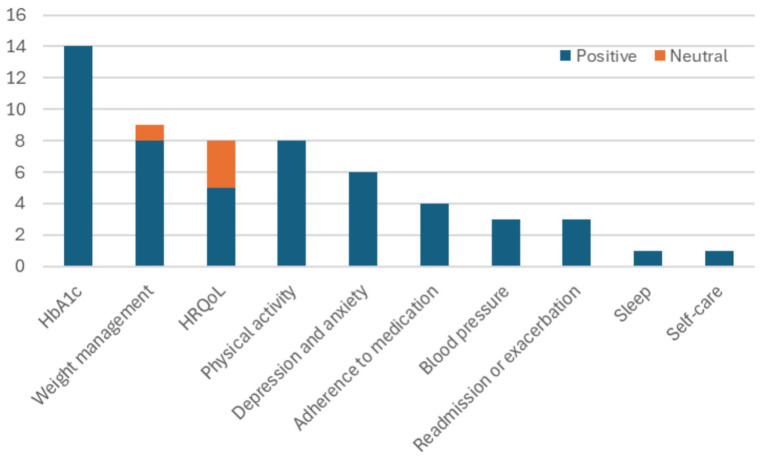

Regarding the variables of interest, out of the 35 studies, the observations are summarized in Figure 6 and are also listed below:

Fourteen studies reported positive results on the reduction of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) with the use of mHealth devices.

Eight studies examined health-related quality of life (HRQoL); in three cases, there were no statistically significant differences, while the groups using mHealth devices in the other five studies experienced better HRQoL.

Seven studies focused on physical activity and performance, while one study focused on the six-minute walk distance (6MWD), all reflecting increased attention to physical activity levels.

Six studies addressed depression and anxiety, with mostly self-reported benefits observed.

Four studies reported improvements in body fat. Three studies addressed BMI, with one finding no statistically significant change and two BMI reduction. Two studies reported significant weight or waist circumference reduction.

Four studies reported adherence to medications in the mHealth solutions arm.

Three studies examined blood pressure, noting reductions.

Two studies reported reduced hospital readmissions, while one reported improvement in exacerbations.

One study noted improvements in sleep time.

One study reported improvement in self-care/management.

Figure 6.

Variables of interest considered across the 35 studies.

What can be observed considering the variables of interest is that clinical outcomes are important in mHealth solutions, since HbA1c, blood pressure, readmissions and exacerbations are considered 20 times. On the other hand, there is a definite shift toward behavioral variables. Objectively measured behavioral variables (weight-related, physical activity and sleep) are considered 18 times, while subjectively reported variables (HRQoL, depression, anxiety, adherence to medication and self-care) are considered 19 times.

4.2. The desired app characteristics

Based on the principal findings of the systematic literature review, it is apparent that following features and essential characteristics for SaMDs that can support chronic disease patients. We can categorize features in terms of functionalities or technical feature and health outcomes.

4.2.1. Technical features

-

PROMs: Collecting licensed or custom questionnaires, such as EQ-5D-5L, capture patient experience directly and can give useful information to the healthcare professionals (HCPs) like

Enhancing clinical decision-making

Improving treatment personalization

Facilitating regulatory compliance

-

Demonstrating real-world effectiveness

The key features that are important when using PROMs are the scheduling that should be based actions or dates orchestrated by clinical pathways and the personalization of PROMs delivery according to patient’s status.

-

Notifications: This functionality uses the push notifications of the smartphones and communicates to the patients any type of message. Questionnaires can be sent via this functionality, medication reminders as well as any other type of message to remind patients to do certain actions like expiring questionnaires or other tasks like inserting their weight.

The key features here are to allow flexibility on using them and a key feature is to be able to schedule them automatically as per the needs of a clinical protocol but also allowing the clinician to send them instantly to an individual or a group of patients.

-

Alerts: An alert dashboard for HCPs in a software as a medical device (SaMD) is very valuable to help prioritizing and management of time to cater for patients that need more immediate attention.

The key feature for such a tool is to facilitate evidence-based decision-making by presenting key metrics and offer data-driven care. Some other features could be summarized below:

Real-time monitoring: Enables quick identification of critical issues or changes in patient conditions.

Efficiency: Streamlines workflow by consolidating important information in one place.

Early intervention: Allows for timely medical responses, potentially preventing complications.

Compliance tracking: Assists in monitoring adherence to treatment plans or medication schedules.

-

Messaging and teleconsultation: These features establish a communication channel between the HCPs and the patients via messages inbox integrated with teleconsultation provision. Some key benefits are the following:

Reduction of burden: Both clinicians and patients can benefit from a virtual visit instead of a physical one in hospital saving time and resources.

Efficiency: Clinician’s burden is reduced as a lot of messages can be dealt with by the nurses.

Early intervention: It allows for timely medical responses, potentially preventing complications.

Enhanced patient engagement: Patients report if anything seems off or if they have a question concerning their treatment plan.

-

Conversational agent: This feature is also called chatbot or agent. The functionality is to give assistance to the patient once they have asked for help on predefined topics. It can be patient or system initiated, starting a dialog, and offering predefined topics and solutions to the user.

The key features for such agents are to be also system initiated based on certain parameters and it can be used to offer personalized behavioral change coaching through the interaction with the patient based on their progress.

-

Goal setting: This feature is great to enhance patient engagement and track progress toward a health goal. Here are some key features:

Personalized goal creation: Allow patients and healthcare providers to collaboratively set tailored goals.

Progress tracking: Visual representations of goal progress over time.

Reminders and notifications: Automated alerts to keep patients engaged with their goals.

Adjustable targets: Flexibility to modify goals based on patient progress or changing circumstances.

System feedback: Recognition of wins and achievements to motivate.

Smart goals: AI models to predict a patient’s individual trajectory based on assessing their starting point.

4.2.2. Health outcomes

Symptom/condition tracking: Further to the PROMs, one question widgets or widgets can be allocated to capture mood, symptoms, pain scores, and so on.

Medication management: This feature is very helpful to both clinicians and patients. The benefit for the clinician is to monitor medication adherence from a dashboard after setting up and managing their medication plan with history of drugs, dosages, and frequencies. The patients, on the other hand, will see their medication on their phone and can set up to receive medication reminders or not in order to confirm that the medication was taken.

Measurements: To offer a closer monitoring of patients, some require the use of medical devices to capture daily or, in other frequencies, vitals like spO2, blood pressure, weight, blood glucose, and others. This can be dealt with a manual logging of data of via integration with digital devices. These data points are transferred to the platform and can be viewed by clinicians. A key feature would be to set up rules in order to alert when a critical issue is identified or there is a change in trend of a major value, indicating a change in a patient’s condition.

Lab exams: Similar to the measurements, values of biomarkers can be inserted manually or through an integration with a medical device and can be viewed in the platform for clinical decision.

Activity tracking: The literature is very clear on the importance of physical activity in terms of steps and activity minutes mainly, but also resulting information regarding the kilocalories (kcal) spent on such activity. This information helps the clinicians assess the patient health status. The reduction in steps is a very clear deterioration of health if it is accompanied by good treatment adherence and other symptoms. The key feature here is the integration with activity trackers in order to also get the variety of data points that can be obtained from the wearable.

-

Sleep: Sleep tracking is an important feature for many health-related SaMDs. The key aspects to take into consideration when tracking sleep are duration, time of sleep onset, and quality metrics related to rapid eye movement (REM) and time awake. To receive such information, it is key to have a wearable integration. Other key features are as follows:

Sleep pattern visualization: Provide graphs or charts showing sleep trends over time.

Sleep hygiene recommendations: Offer personalized tips based on tracked data.

Sleep goal setting: Enable users to set and track sleep-related goals.

Environmental factors: Log room temperature, noise levels, or light exposure that may affect sleep.

Correlation with other health data: Show relationships between sleep and other tracked health metrics.

Sleep score: Provide a simplified daily score to help users quickly gage their sleep quality.

Reminders: Send notifications for consistent bedtimes or pre-sleep routines.

Nutrition: Last but not least, it is very common when discussing chronic diseases to discuss nutritional habits and consumption of nutrients. Incorporating nutrition tracking and management into an SaMD can be highly beneficial for patient health. The key features for a nutrition component are as follows:

Food logging: Allow users to record meals and snacks, with a searchable database that can be a challenge when only local products are available.

Nutrient tracking: Monitor intake of calories, macronutrients, and micronutrients.

Personalized recommendations: Offer dietary suggestions based on health goals and conditions.

Integration with health data: Connect nutrition info with other health metrics like blood sugar or weight.

Visual summaries: Display charts of nutritional intake over time.

Goal setting: Allow users to set and track nutrition-related goals.

Educational content: Provide information on balanced diets and nutrition basics.

Recipe suggestions: Offer healthy recipe ideas aligned with dietary needs.

Hydration tracking: Include water intake monitoring.

4.3. Conclusion

The systematic literature review demonstrates the significant potential of SaMD and mHealth applications in revolutionizing chronic disease management through remote patient monitoring (RPM) and digital therapeutics (DTx). The evidence synthesized from multiple systematic reviews and clinical studies indicates that these technologies, exemplified by solutions like Healthentia, can effectively support patient monitoring and improve health outcomes while meeting crucial safety and performance requirements. The positive results observed across various chronic conditions underscore the transformative role of digital health interventions in modern healthcare delivery. However, further research is needed to address long-term efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and integration into existing healthcare systems. As the field rapidly evolves, continued evaluation and refinement of these technologies will be essential to fully realize their potential in enhancing patient care and health management strategies.

4.4. Future research

The health outcomes presented in the principal findings are mainly connected to the increased adherence of the patients. It is apparent that SaMDs that offer high levels of engagement with the patient can increase adherence and result in positive health outcomes. However, the impact of lifestyle change, which is the common denominator in chronic diseases, is not considered. The future research will be focused on the benefits of virtual coaching and how this can consume all data captured by the device and processed in a way to orchestrate behavioral change techniques with a strong impact on the patient’s health.

The growing adoption of RPM signifies a shift toward more patient-centered, data-driven healthcare delivery. Looking ahead, the integration of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning into RPM platforms is expected to further optimize care delivery and decision-making processes.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available through the cited papers, as it is a systematic literature review.

Author contributions

SK: Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AP: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KK: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KT: Writing – review & editing. EG: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RP: Writing – review & editing. MG: Writing – review & editing. PF: Writing – review & editing.

Conflict of interest

SK, AP, and KK are employed by Innovation Sprint srl.

MG and PF are employed by AstraZeneca SpA.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Grand View Research . (2022). Remote patient monitoring system market size, share & trends analysis report by product, by application, by end-use, by region, and segment forecasts, 2023–2030. Grand View Research.

- 2.Hariharan U, Rajkumar K, Akilan T, Jeyavel J. Smart wearable devices for remote patient monitoring in healthcare 4.0 In: Hemanth DJ, Anitha J, Tsihrintzis GA, editors. Internet of Medical Things. Internet of Things. Cham: Springer; (2021) [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Souza F, de Aguiar Franco F, dos Santos Lara MM, Levcovitz AA, Dias MA, Moreira TR, et al. The effectiveness of mobile application for monitoring diabetes mellitus and hypertension in the adult and elderly population: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. (2023) 23:855. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09879-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JJN, Abdul Aziz A, Chan S-T, Raja Abdul Sahrizan RSF b, Ooi AYY, Teh Y-T, et al. Effects of mobile health interventions on health-related outcomes in older adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes. (2023) 15:47–57. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.13346, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J-E, Park T-S, Kim KJ. The clinical effects of type 2 diabetes patient management using digital healthcare technology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). (2022) 10:522. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10030522, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He Q, Zhao X, Wang Y, Xie Q, Cheng L. Effectiveness of smartphone application-based self-management interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs. (2022) 78:348–62. doi: 10.1111/jan.14993, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu K, Xie Z, Or CK. Effectiveness of mobile app-assisted self-care interventions for improving patient outcomes in type 2 diabetes and/or hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2020) 8:e15779. doi: 10.2196/15779, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masotta V, Dante A, Caponnetto V, Marcotullio A, Ferraiuolo F, Bertocchi L, et al. Telehealth care and remote monitoring strategies in heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Lung. (2024) 64:149–67. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2024.01.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitsiou S, Vatani H, Paré G, Gerber BS, Buchholz SW, Kansal MM, et al. Effectiveness of mobile health technology interventions for patients with heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Cardiol. (2021) 37:1248–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.02.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uminski K, Komenda P, Whitlock R, Ferguson T, Nadurak S, Hochheim L, et al. Effect of post-discharge virtual wards on improving outcomes in heart failure and non-heart failure populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2018) 13:e0196114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196114, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaén-Extremera J, Afanador-Restrepo DF, Rivas-Campo Y, Gómez-Rodas A, Aibar-Almazán A, Hita-Contreras F, et al. Effectiveness of telemedicine for reducing cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med. (2023) 12:841. doi: 10.3390/jcm12030841, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cruz-Cobo C, Bernal-Jiménez M, Vázquez-García R, Santi-Cano MJ. Effectiveness of mHealth interventions in the control of lifestyle and cardiovascular risk factors in patients after a coronary event: systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2022) 10:e39593. doi: 10.2196/39593, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson K, Davey R, Keegan R, Freene N. Smartphone applications for physical activity and sedentary behaviour change in people with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. (2021) 16:e0258460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258460, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu J-W, Wang Y, Sun Y, Zhang Q, Yan L-M, Wang Y-X, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring for reducing exacerbation occurrence in COPD patients with past exacerbation history: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). (2021) 8:720019. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.720019, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang S, Kim Y, Cho W-K. A systematic review and meta-analysis of telemonitoring interventions on severe COPD exacerbations. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:6757. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18136757, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buneviciene I, Mekary Rania A, Smith TR, Onnela J-P, Bunevicius A. Can mHealth interventions improve quality of life of cancer patients? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. (2021) 157:103123. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103123, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holmen H, Torbjørnsen A, Wahl AK, Jenum AK, Småstuen MC, Årsand E, et al. A mobile health intervention for self-management and lifestyle change for persons with type 2 diabetes, part 2: one-year results from the Norwegian randomized controlled trial RENEWING HEALTH. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2014) 2:e57. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3882, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karhula T, Vuorinen A, Rääpysjärvi K, Pakanen M, Itkonen P, Tepponen M, et al. Telemonitoring and mobile phone-based health coaching among Finnish diabetic and heart disease patients: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17:e153. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4059, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J, Wei D, Liu S, Li M, Chen X, Chen L, et al. Efficiency of an mHealth App and chest-wearable remote exercise monitoring intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes: a prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2021) 9:e23338. doi: 10.2196/23338, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombes JS, Keating SE, Mielke GI, Fassett RG, Coombes BK, O’Leary KP, et al. Personal activity intelligence e-health program in people with type 2 diabetes: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. (2022) 54:18–27. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boer L, Bischoff E, van der Heijden M, Lucas P, Akkermans R, Vercoulen J, et al. A smart mobile health tool versus a paper action plan to support self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e14408. doi: 10.2196/14408, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun C, Sun L, Xi S, Zhang H, Wang H, Feng Y, et al. Mobile phone–based telemedicine practice in older chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e10664. doi: 10.2196/10664, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chao Dyna YP, Lin TMY, Ma W-Y. Enhanced self-efficacy and behavioral changes among patients with diabetes: cloud-based mobile health platform and mobile app service. JMIR Diabetes. (2019) 4:e11017. doi: 10.2196/11017, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Z, Tan E, Lum E, Sloot P, Boehm BO, Car J, et al. A smartphone app to improve medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes in asia: feasibility randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e14914. doi: 10.2196/14914, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhai Y, Yu W. A mobile app for diabetes management: impact on self-efficacy among patients with type 2 diabetes at a community hospital. Med Sci Monit. (2020) 26:e926719. doi: 10.12659/MSM.926719, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey DP, Mugridge LH, Feng D, Xu Z, Chater Angel M. Randomised controlled feasibility study of the MyHealthAvatar-diabetes smartphone app for reducing prolonged sitting time in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2020) 17:4414. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patnaik L, Panigrahi SK, Sahoo AK, Mishra D, Muduli AK, Beura S. Effectiveness of mobile application for promotion of physical activity among newly diagnosed patients of type II diabetes – a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. (2022) 13:54. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_92_20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S, Kim JY, Lee JC, Kim HR, Song S, Kwon H, et al. Mobile phone app–based pulmonary rehabilitation for chemotherapy-treated patients with advanced lung cancer: pilot study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e11094. doi: 10.2196/11094, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim S, Kang SM, Kim KM, Moon JH, Choi SH, Hwang H, et al. Multifactorial intervention in diabetes care using real-time monitoring and tailored feedback in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. (2016) 53:189–98. doi: 10.1007/s00592-015-0754-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pappot H, Assam Taarnhøj G, Elsbernd A, Hjerming M, Hanghøj S, Jensen M, et al. Health-related quality of life before and after use of a smartphone app for adolescents and young adults with cancer: pre-post interventional study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e13829. doi: 10.2196/13829, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang J, Weng L, Chen Z, Cai H, Lin X, Hu Z, et al. Development and testing of a mobile app for pain management among cancer patients discharged from hospital treatment: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2019) 7:e12542. doi: 10.2196/12542, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hansel B, Giral P, Gambotti L, Lafourcade A, Peres G, Filipecki C, et al. A fully automated web-based program improves lifestyle habits and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes and abdominal obesity: randomized trial of patient E-coaching nutritional support (the ANODE study). J Med Internet Res. (2017) 19:e360. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7947, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katalenich B, Shi L, Liu S, Shao H, McDuffie R, Carpio G, et al. Evaluation of a remote monitoring system for diabetes control. Clin Ther. (2015) 37:1216–25. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.022, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nagrebetsky A, Larsen M, Craven A, Turner J, McRobert N, Murray E, et al. Stepwise self-titration of oral glucose-lowering medication using a mobile telephone-based telehealth platform in type 2 diabetes: a feasibility trial in primary care. J Diabetes Sci Technol. (2013) 7:123–34. doi: 10.1177/193229681300700115, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davoudi M, Najafi Ghezeljeh T, Vakilian Aghouee F. Effect of a smartphone-based app on the quality of life of patients with heart failure: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Nursing. (2020) 3:e20747. doi: 10.2196/20747, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clays E, Luštrek M, Pioggia G, Derboven J, Vrana M, de Sutter J, et al. Proof-of-concept trial results of the HeartMan mobile personal health system for self-management in congestive heart failure. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:5663. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84920-4, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Athilingam P, Jenkins B, Johansson M, Labrador M. A mobile health intervention to improve self-care in patients with heart failure: pilot randomized control trial. JMIR Cardio. (2017) 1:e3. doi: 10.2196/cardio.7848, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park C, Otobo E, Ullman J, Rogers J, Fasihuddin F, Garg S, et al. Impact on readmission reduction among heart failure patients using digital health monitoring: feasibility and adoptability study. JMIR Med Inform. (2019) 7:e13353. doi: 10.2196/13353, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Y, Li M, Zhao X, Pan X, Lu M, Lu J, et al. Effects of continuous care for patients with type 2 diabetes using mobile health application: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Health Plann Manage. (2019) 34:1025–35. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2872, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunawardena KC, Jackson R, Robinett I, Dhaniska L, Jayamanne S, Kalpani S, et al. The influence of the smart glucose manager mobile application on diabetes management. J Diabetes Sci Technol. (2019) 13:75–81. doi: 10.1177/1932296818804522, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinman NJ, Shah A, Shah S, Phatak S, Viswanathan V. Improved medication adherence and frequency of blood glucose self-testing using an m-health platform versus usual care in a multisite randomized clinical trial among people with type 2 diabetes in India. Telemed J E Health. (2017) 23:733–40. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0265, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukuoka Y, Gay CL, Joiner KL, Vittinghoff E. A novel diabetes prevention intervention using a mobile app: a randomized controlled trial with overweight adults at risk. Am J Prev Med. (2015) 49:223–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.003, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wayne N, Perez DF, Kaplan DM, Ritvo P. Health coaching reduces HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients from a lower-socioeconomic status community: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2015) 17:e224. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4871, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pernille L, Asta B, Astrid B, Jostein G, Even J, Nilsson BB. Long-term follow-up with a smartphone application improves exercise capacity post cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. (2020) 27:1782–92. doi: 10.1177/2047487320905717, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnston N, Bodegard J, Jerström S, Åkesson J, Brorsson H, Alfredsson J, et al. Effects of interactive patient smartphone support app on drug adherence and lifestyle changes in myocardial infarction patients: A randomized study. American Heart Journal. (2016) 178:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2016.05.005, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Persell SD, Peprah YA, Lipiszko D, Lee JY, Li JJ, Ciolino JD, et al. Effect of home blood pressure monitoring via a smartphone hypertension coaching application or tracking application on adults with uncontrolled hypertension: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. (2020) 3:e200255. doi: 10.1001/jamanetstudyopen.2020.0255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hilmarsdóttir E, Sigurðardóttir ÁK, Arnardóttir RH. A digital lifestyle program in outpatient treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled study. J Diabetes Sci Technol. (2021) 15:1134–41. doi: 10.1177/1932296820942286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Da Young L, Jeongwoon P, Dooah C, Hong-Yup A, Sung-Woo P, Cheol-Young P. The effectiveness, reproducibility, and durability of tailored mobile coaching on diabetes management in policyholders: A randomized, controlled, open-label study. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:3642. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22034-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Y, Yan Q, Li H, Li H, Wang L, Wang H, et al. Effects of mobile phone application combined with or without self-monitoring of blood glucose on glycemic control in patients with diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. J Diabetes Investig. (2019) 10:1365–71. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13031, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brath H, Morak J, Kästenbauer T, Modre-Osprian R, Strohner-Kästenbauer H, Schwarz M, et al. Mobile health based medication adherence measurement – a pilot trial using electronic blisters in diabetes patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. (2013) 76:47–55. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12184, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y, Lee EY, Kim H-S, Lee S-H, Yoon K-H, Cho J-H. Effect of a mobile phone–based glucose-monitoring and feedback system for type 2 diabetes management in multiple primary care clinic settings: cluster randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. (2020) 8:e16266. doi: 10.2196/16266, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Europe PMC . “Europe PMC: Free Article Database.” Europe PMC. Available at: https://europepmc.org/

- 53.Healthentia SaMD . “Healthentia Software as Medical Device”. Available at: https://europepmc.org/.

- 54.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framestudy to improve searching Pub Med for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. (2007) 7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available through the cited papers, as it is a systematic literature review.