Abstract

Regional sea level rise has been regarded a key factor in understanding of climate change impact to coastal communities. As a vulnerable island to sea level rise and storm surges, the province of Prince Edward Island (PEI) in Canada lacks sufficient long-term island-wide historic record of sea level data. This has become a major challenge for further studies on coastal environments and climate change adaptation. To overcome this limitation, here we reconstruct a long-term hourly sea level dataset using the existing long-term records of limited permanent tide stations and short-term records of widely-distributed temporary stations. With comprehensive statistical analysis and modeling, the historical sea level records furthest between 1911 and 2023 are reconstructed with an hourly time step. This new dataset significantly extends the availability of long-term sea level data along with the shoreline of PEI, which can be used for further studies on coastal change assessment and coastal hazard adaptation in the context of climate change.

Subject terms: Physical oceanography, Physical oceanography

Background & Summary

Sea level rise (SLR) has been widely regarded as a threat to global coastal communities in the context of climate change1. Previous research has revealed that the melting glaciers and increased buoyancy fluxes have been significantly lifting the sea level under a warming climate2,3, which makes the coastal communities face the increasing risks of inundation and flooding. The research focusing on the 20th century found that the averaged global SLR has changed from 1.7 to 3.3 mm/year, which has shown a significant accelerating trend from the middle to the late 20th century4. At the regional-study scope, the Pearl River Estuary (by the north coast of South China Sea) reported a 3.9 mm/year SLR from 1993 to 20205; the SLR in the North Sea has risen by 1.0 mm/year and has exceeded 2.7 mm/year after the year of 19936; Southeastern Australia has shown an 0.2–0.3 m SLR in the last 200 years with an rising rate of 4.0 mm/year from 1900 to 19497. In this context, there have been more frequent coastal hazards related to SLR globally8, such as coastal flooding events, long-term coastal land inundation, and coastal erosion. National wide observations across the USA have proved the growing frequency of coastal flooding events since the 1950s9; worldwide coastal communities, especially large cities, are facing a series of further impacts of urban inundation, ecosystem degradation, heritage destruction, and even displacement of population10; different regional studies have indicated that the coastal erosion will also be accelerated by the rising sea levels11,12. Towards the various potential consequences associated with SLR, it is highly significant to have the record of the long-term and spatially-explicit regional SLR and to understand its changing pattern, for a resilient coastal flooding control and environmental management for coastal communities5,13.

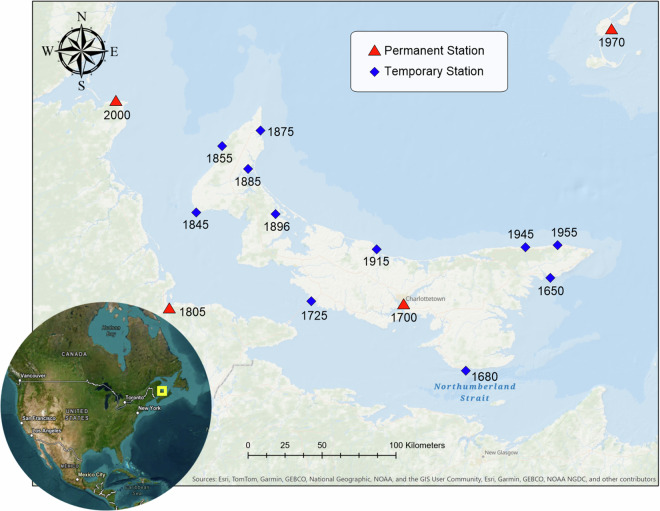

Prince Edward Island (PEI) is located by the south coast of Gulf of St. Lawrence, on the Atlantic coast of Canada (Fig. 1). The province of PEI is the smallest, lowest-lying and most densely-populated, and the only island provincial administrative region in Canada. In the recent decades, PEI has been increasingly reported having a rising vulnerability towards climate change impacts14, and has been regarded as a typical research site for climate change and adaptation studies, including the topics of coastal flooding15,16, coastal erosion17,18, community resilience19,20, agricultural management21,22, ecology and landcover23,24, tourism management25,26, and public health27. These recent and ongoing regional research works in PEI are mostly to solve the challenges for the environmental security and sustainable development of the local coastal communities. The relevant challenges are tightly associated with the unique geographic conditions of PEI. Geologically, PEI has a low elevation range of 0–142 m with sedimentary geological bodies of red sandstone or mudstone, and red soil layer. Along the shoreline of PEI, a series of coastal morphologic areas have been formed by the ocean activities, such as estuaries, bays, beaches, bluffs, sandbanks, and barrier islands, which are basically in an unconsolidated texture17. PEI has a cool and humid oceanic climate (−3~−11C in winter and 20–34 C in summer) with over 1100 mm annual precipitation (about 80% rainfall and 20% snowfall)28. Frequent storm hazards has occurred here in the recent 5 years, including 2019 Storm Dorian, 2021 Hurricane Ida, and 2022 Hurricane Fiona, which have all caused severe floods and erosions in the coastal environments and communities in PEI19. In this context, the only pillar industries of the PEI society, including agriculture, fisheries and tourism, have shown their sensitivities to the climate change impacts. Regional SLR around PEI, in the past and future, has been revealed and projected to significantly influence the coastal-change processes and further leading to adverse effects on the coastal land resources, local populations and socioeconomic activities18,29. Especially the hazards of coastal erosion, storm surge, and flooding have been listed as the major climate change risks in PEI14, to which SLR may have an important contribution by raising the frequency of and the damage caused by these potential hazards, according to the global research experience30–32.

Fig. 1.

PEI and surrounding sea areas on the terrain map (retrieved from ESRI via ArcGIS Pro), and the DFO tide stations (marked with ID) utilized in this study.

With the necessary need of understanding the regional SLR, the long-term and site-specific sea level records become an important reference33. The previous studies in the Thames Estuary, UK13, coastal sites in Spain34,35, estuaries in Northeastern USA36,37, and Marseille, France38 have shown researchers’ efforts in providing the datasets of regional sea level record. Along the shoreline of Canada, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has been providing the freely-available sea level records via Canadian Tides and Water Levels Data Archive (https://www.isdm-gdsi.gc.ca/isdm-gdsi/twl-mne/index-eng.htm)39, in which the earliest record started from the year of 1848 and over 60 stations have had the historic record for over 50 years. While for the research site of PEI, there is only one permanent DFO tide station (i.e., Charlottetown tide station, station ID: 1700; in Fig. 1)40, which started recording in 1911 and now is still in operation. Meanwhile, there used to be several temporary stations along the shoreline of PEI (Fig. 1), which run shortly in different historic periods and have short-term records of their running, but none of them are still in operation nowadays. In the recent years, the University of PEI has established the PEI Storm Surge Early Warning System (PSSEWS, https://pssews.peiclimate.ca/)41, which has set up multiple island-wide tide stations and has kept the sea level records after the year of 2020. However, for the other parts of the island, there still lacks long-term observation records of SLR.

Facing the need of keeping the long-term spatially-explicit sea level records and understanding the SLR around PEI across the recent two centuries, and the limitation of lacking island-wide sea level observations, we expect to explore the possibility of using the existing records of both permanent stations close to PEI (not limited to be in PEI) and the temporary stations in PEI to reconstruct the sea level variation in a correlation approach. This simulation will markedly improve the availability of the island-wide SLR records into decades scale throughout the 20th century and the early 21st century with reliable reconstructed sea-level data. The outcomes of this sea level reconstruction are expected to help the researchers focusing on PEI’s nearshore hydrodynamics, coastal erosion, maritime management, coastal landscape evolution, and regional historical geography. An open-source dataset of PEI regional SLR may also further provide available resources for decision-makers and the public to understand the coastal-change processes around the island and the impact of climate change.

Methods

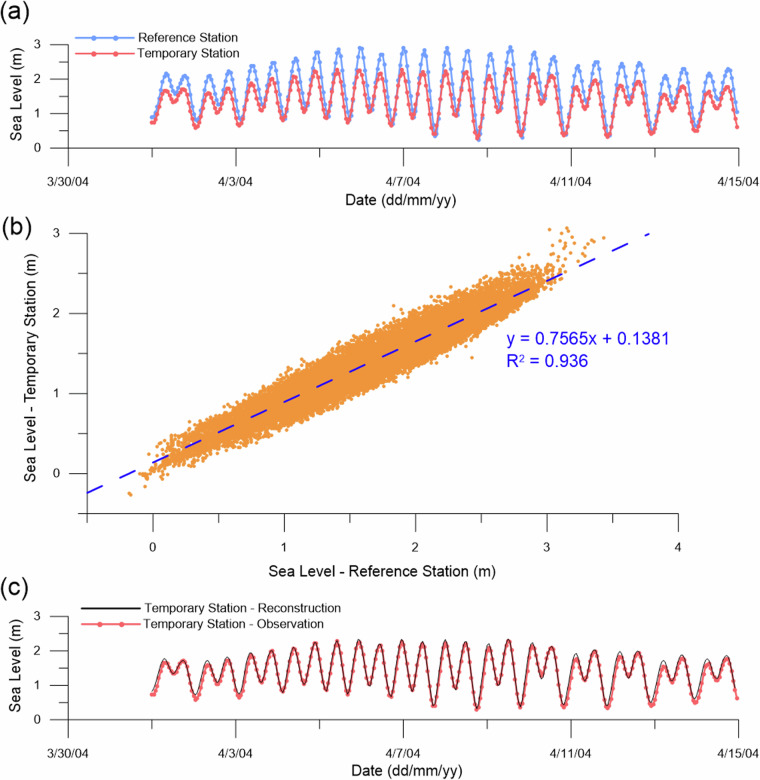

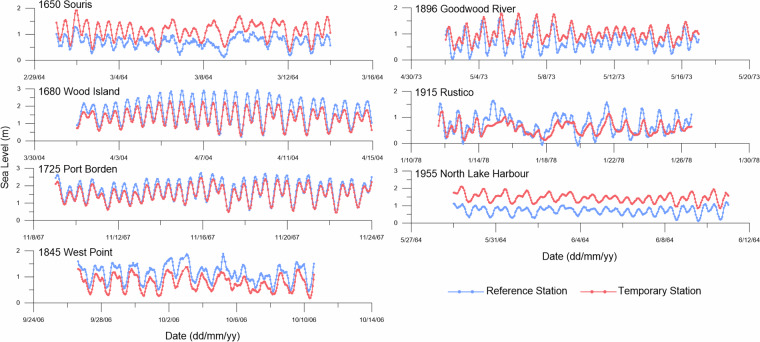

Based on the existing records of the permanent and temporary stations around PEI, trying to establish the statistical correlation between them and then to reconstruct the sea levels can be considered as a feasible method to address the limitation of short record at the temporary stations. The core principle behind this method is that the same-time tide records of a temporary station have a high similarity with a nearby and geographically-connected permanent station, as the ebb and flow of the tides at these station combinations share the same processes in a certain spatial area13,42–44. In this case, if the records have any temporal overlaps between a temporary and a permanent station, a linear regression can be generated based on that similarity, and the simulated long-term sea levels can be reconstructed following the linear correlation for each temporary station. According to the records of different DFO stations around PEI, their greatest common divisor of their sampling intervals in different periods is one hour39. Hence, the hourly data, which we use in the reconstruction, also provides a relatively high temporal-resolution for getting more accurate correlations based on the record overlaps from monthly to interannual scales. Our reconstruction following three steps (Fig. 2), which are (1) examining the spectrum of each temporary station and its reference station in a randomly-selected 14-day window in their overlapped period (also shown in Fig. 4) to determine the temporal offset for regression, (2) establishing the correlation between each temporary station and its reference station using linear regression method and checking the R2 value, and (3) reconstructing the long-term sea level data for each temporary station using the equation from step (2). It should be noted that due to the tidal dynamics, the best temporal matching may not always be the synchronous one in each combination. In other words, although the temporary station and its reference station has a highly-similar trend of sea level variation, their variation can be at the same time or a few (usually less that 3) hours different, which will be identified in the step (1).

Fig. 2.

Intermediate results from the three steps of sea level reconstruction (demonstrated at Wood Island (ID: 1680) station): (a) spectrum of the temporary station and its reference station; (b) linear regression of the matched water level records, after identifying the record of Wood Island best matching that 1-hour-earlier of Charlottetown; and (c) the comparison of the reconstructed sea level data and the correlated observation data.

Fig. 4.

Spectrum check for all the selected temporary stations.

Through our initial examination of the existing records of the permanent stations in or close to PEI, there are in total four stations appropriate for our study, which are Charlottetown (ID: 1700) in PEI, Shediac Bay (ID: 1805) in the province of New Brunswick, Cap-aux-Meules (ID: 1970) in the province of Quebec, and Lower Escuminac (ID: 2000) in the province of New Brunswick (Fig. 1, Table 1). All the four permanent stations are still in operation and have long-term records across decades since the last century, among which the Charlottetown station has the longest record since the year of 1911 and the continuous record since 1938 (Fig. 3). As for the temporary stations, there used to be in total 11 stations in PEI, however, 4 of them had poor records due to probable operational failure or could not satisfactorily match a permanent station with valid records based on the correlation, so that be discarded for the island-wide SLR reconstruction, which are Miminegash (ID: 1855), Tignish (ID: 1875), Alberton (ID: 1885), and Naufrage (ID: 1945). The other 7 temporary stations are selected for the reconstruction (shown in Figs. 1, 3 and Table 1).

Table 1.

Information of the applied stations.

| Station | Station ID | Latitude (N) | Longitude (W) | Permanent/Temporary | Reference Station | Correlation | R2 | Time difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlottetown | 1700 | 46.23 | 63.12 | Permanent | √ (CH) | N/A | ||

| Shediac Bay | 1805 | 46.23 | 64.55 | √ (SB) | ||||

| Cap-aux-Meules | 1970 | 47.38 | 61.86 | √ (CAM) | ||||

| Lower Escuminac | 2000 | 47.08 | 64.88 | √ (LE) | ||||

| Souris | 1650 | 46.35 | 62.25 | Temporary | CAM | y = 1.3217x + 0.2049 | 0.858 | Synchronous |

| Wood Island | 1680 | 45.95 | 62.75 | CH | y = 0.7565x + 0.1381 | 0.936 | 1 hour earlier than CH | |

| Port Borden | 1725 | 46.25 | 63.70 | CH | y = 0.7921x + 0.2276 | 0.892 | Synchronous | |

| West Point | 1845 | 46.63 | 64.40 | SB | y = 0.8692x −0.2026 | 0.882 | Synchronous | |

| Goodwood River | 1896 | 46.62 | 63.92 | LE | y = 0.8534x + 0.3942 | 0.897 | 2 hours later than LE | |

| Rustico | 1915 | 46.47 | 63.28 | LE | y = 0.5682x + 0.2261 | 0.798 | 2 hours later than LE | |

| North Lake Harbor | 1955 | 46.47 | 62.07 | CAM | y = 0.8810x + 0.7838 | 0.814 | Synchronous | |

Fig. 3.

Duration of datasets at all stations around PEI.

Through checking the sea level records of all the stations, there are some unavoidable data points losses found in the records of the selected stations. Therefore, a manual examination and correction has also been done for all the overlapped data points of each station combination, to ensure that the overlapped records of the two stations best match each other. The final reference stations are determined by the highest coefficient of determination (R2) values among the comparisons in addition to the spectrum check (Fig. 4). There are in total 3 stations having temporal shifts applied in the reconstruction progress, which are the stations of Wood Island (ID: 1680), Goodwood River (ID: 1896) and Rustico (ID: 1915), they cannot match any permanent stations synchronously. The possible reasons of the time offsets can be special geomorphologies, such as estuaries, bays, river channels and straits, that the tidal current may travel for some time to reach the farther direction13,43. We have concluded the best asynchronous matching of the lagged correction for these three stations, which are Wood Island best matching 1-hour-earlier Charlottetown, and Goodwood River and Rustico best matching 2-hour-later Lower Escuminac.

With the linear correlation obtained for each selected temporary station and its reference station (shown in Table 1), the simulated sea levels at the locations of all the selected stations can be reconstructed using the correlation to transform the sea level records of the reference stations. Note, there are also some unavoidable data losses in the records of the selected permanent stations, which could result from equipment failure, extreme weather, and equipment maintenance. As the availability of the record of the simulated reconstruction for temporary stations fully depends on their reference stations, if the reference stations have any lost data points, they will be reflected in the simulated data for the associated temporary stations.

Data Records

This newly generated sea level reconstruction for the nearshore area around PEI, Canada is freely available to the public via the Figshare database (10.6084/m9.figshare.27989570)45. The dataset consists of 13 files, including one introduction (TXT) file named “ReadMe.txt”, one Excel spreadsheets (XLSX) file named “PEI_sea_level_reconstruction.xlsx” containing sea level records for all the selected 11 stations, and 11 comma separate variable (CSV) files named in the form of “Station ID_Name.csv” for respectively for each selected station. The temporal resolution for all the data is one hour, and the time zone is the local time (UTC-4). The datum used in the dataset is the chart datum (CD), that represents the reference plane to which depths on a published chart, all tide height predictions, and most water level measurements are referred46. The unit used for water level is meter (m) and each value is accurate to two decimal places (i.e., cm). For different permanent stations, Charlottetown station has the earliest record in Jan. 1911 and continuous records since 1938. Shediac Bay station has the earliest record from Nov. 1971 and has a one-month (July) break in 1981 and an interannual break from Mar. 1992 to Aug. 2003. Cap-aux-Meules station has the earlies record in Mar. 1964 while has several on-and-off breaks between Dec. 1969 and June 2007, which may be due to its high difficulty for maintenance on an offshore island. Lower Escuminac has the continuous records since Jan. 1973. Accordingly, the associated temporary stations have the same duration of available reconstructed data as their own reference stations. Through this reconstruction work, the long-term sea level data in PEI has been expanded from the only available station of Charlottetown to in total 8 stations across the island (Fig. 5). The newly-generated dataset is expect to play a supportive role in relevant studies in the coastal environments of PEI, especially for those may need a historic record as a reference.

Fig. 5.

Distribution of the reconstructed sea level data in PEI.

Technical Validation

The objective of establishing this reconstructed sea level dataset is to maximum address the lack of observation records. Hence, it is not feasible to directly compare the data points with any observed reference values. In this case, it is more important to check if this simulation dataset is reasonable or reliable enough for providing the SLR changing pattern. Accordingly, two key questions should be noted for the technical validation: 1) if the expected matched data points of each station combination are used for the linear regression due to the existing losses of data points; 2) if the linear correlation between each selected temporary station and its reference station is reliable enough.

For the matching examination, we have manually and visually gone through each overlapped sea-level match throughout all the 7 station combinations, which contains in total 46,152 matches. The asynchronous adjustments for Wood Island, Goodwood River and Rustico were made after the temporal-matching corrections. For the reliabilities of the linear correlations, we have examined the R2 values of them. The results showed that all of them exceeded 0.79, and 5 of the 7 exceeded 0.85 (shown in Table 1). Although there is no fixed requirement for R2 value, we would like to justify that our results have been operated the spectrum examination (Fig. 4) for all the station combinations to ensure the reconstructions are based on the correlated sea level variation trends, and some research experiences in oceanography have even used significantly lower values (e.g., 0.30–0.60) as their threshold for approval and have regarded the R2 values over 0.70 as highly-correlated47,48. Therefore, we regard our results having a strong reliability to well reflect the sea level variations around PEI as a simulated dataset. While in the meantime, the future users of this dataset should also notice the potential bias between the simulated sea-levels and the objectively real ones that is generated from random errors that cannot be addressed through our reconstruction, which may be from the differences in local-scale short-term hydrometeorological processes like extreme rainfall or wind-wave setup, or the operational issue of individual tidal gauge.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, Natural Resources Canada, and the Government of Prince Edward Island.

Author contributions

T.P. collected the original data, analyzed and modeled the statistical correlation, generated the new dataset, wrote the first draft of the manuscript. X.W. originated the concept of this study, supervised the data collection, analyses and reconstruction, and contributed to the manuscript revision. M.Q.M. and S.B. contributed to data examination and correction, and manuscript revision.

Code availability

Our newly-generated dataset can be found on the open-source database, Figshare (10.6084/m9.figshare.27989570). There is no specific code produced to support this effort. All the analyses described in this paper can be accomplished by commonly-used statistical tools like Microsoft Excel or IBM SPSS Statistics. The original data for this reconstruction work can be downloaded via Canadian Tides and Water Levels Data Archive (https://www.isdm-gdsi.gc.ca/isdm-gdsi/twl-mne/index-eng.htm).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dangendorf, S. et al. Persistent acceleration in global sea-level rise since the 1960s. Nat. Clim. Change9, 705–710 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouttes, N., Gregory, J. M., Kuhlbrodt, T. & Smith, R. S. The drivers of projected North Atlantic sea level change. Clim. Dyn.43, 1531–1544 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fraser, N. J., Inall, M. E., Magaldi, M. G., Haine, T. W. N. & Jones, S. C. Wintertime Fjord-Shelf Interaction and Ice Sheet Melting in Southeast Greenland. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans123, 9156–9177 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Church, J. A. & White, N. J. A 20th century acceleration in global sea-level rise. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33 (2006).

- 5.Li, X. et al. Impacts of river discharge, coastal geomorphology, and regional sea level rise on tidal dynamics in Pearl River Estuary. Front. Mar. Sci. 10 (2023).

- 6.Steffelbauer, D. B., Riva, R. E. M., Timmermans, J. S., Kwakkel, J. H. & Bakker, M. Evidence of regional sea-level rise acceleration for the North Sea. Environ. Res. Lett.17, 074002 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams, S. L. et al. Relative sea-level changes in southeastern Australia during the 19th and 20th centuries. J. Quat. Sci.38, 1184–1201 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cazenave, A. & Cozannet, G. L. Sea level rise and its coastal impacts. Earths Future2, 15–34 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 9.US EPA, O. Climate Change Indicators: Coastal Flooding. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-coastal-flooding (2016).

- 10.Jevrejeva, S., Jackson, L. P., Riva, R. E. M., Grinsted, A. & Moore, J. C. Coastal sea level rise with warming above 2 °C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.113, 13342–13347 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lo Presti, V. et al. Geohazard assessment of the north-eastern Sicily continental margin (SW Mediterranean): coastal erosion, sea-level rise and retrogressive canyon head dynamics. Mar. Geophys. Res.43, 2 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos, C. A. G. et al. Coastal evolution and future projections in Conde County, Brazil: A multi-decadal assessment via remote sensing and sea-level rise scenarios. Sci. Total Environ.915, 169829 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inayatillah, A. et al. Digitising historical sea level records in the Thames Estuary, UK. Sci. Data9, 167 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of PEI. Climate Change Risks Assessment. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/environment-energy-and-climate-action/climate-change-risks-assessment (2021).

- 15.Jardine, D. E., Wang, X. & Fenech, A. L. Highwater Mark Collection after Post Tropical Storm Dorian and Implications for Prince Edward Island, Canada. Water13, 3201 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Dau, Q. et al. Pluvial flood modeling for coastal areas under future climate change – A case study for Prince Edward Island, Canada. J. Hydrol.641, 131769 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pang, T., Wang, X., Basheer, S. & Guild, R. Landcover-based detection of rapid impacts of extreme storm on coastal landscape. Sci. Total Environ.932, 173099 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson-Arnott, R. et al. Assessing the impact of hurricane Fiona on the coast of PEI National Park and implications for the effectiveness of beach-dune management policies. J. Coast. Conserv.28, 52 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah, M. A. R. & Wang, X. Assessing social-ecological vulnerability and risk to coastal flooding: A case study for Prince Edward Island, Canada. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct.106, 104450 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pang, T., Shah, M. A. R., Dau, Q. V. & Wang, X. Assessing the social risks of flooding for coastal societies: a case study for Prince Edward Island, Canada. Environ. Res. Commun.6, 075027 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adekanmbi, T. et al. Assessing Future Climate Change Impacts on Potato Yields — A Case Study for Prince Edward Island, Canada. Foods12, 1176 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Afzaal, H., Farooque, A. A., Abbas, F., Acharya, B. & Esau, T. Precision Irrigation Strategies for Sustainable Water Budgeting of Potato Crop in Prince Edward Island. Sustainability12, 2419 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basheer, S. et al. Comparison of Land Use Land Cover Classifiers Using Different Satellite Imagery and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens.14, 4978 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dau, Q. V., Wang, X., Shah, M. A. R., Kinay, P. & Basheer, S. Assessing the Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Current Coastal Ecosystems—A Canadian Case Study. Remote Sens.15, 4742 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haldane, E. et al. Sustainable Tourism in the Face of Climate Change: An Overview of Prince Edward Island. Sustainability15, 4463 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacEachern, J. et al. Destination Management Organizations’ Roles in Sustainable Tourism in the Face of Climate Change: An Overview of Prince Edward Island. Sustainability16, 3049 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kınay, P., Wang, X., Augustine, P. J. & Augustine, M. Reporting evidence on the environmental and health impacts of climate change on Indigenous Peoples of Atlantic Canada: a systematic review. Environ. Res. Clim.2, 022003 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Government of PEI. PEI Climate and Weather. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/environment-energy-and-climate-action/pei-climate-and-weather (2023).

- 29.Government of PEI. Erosion and Flooding. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/information/environment-energy-and-climate-action/erosion-and-flooding (2021).

- 30.Taherkhani, M. et al. Sea-level rise exponentially increases coastal flood frequency. Sci. Rep.10, 6466 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vitousek, S. et al. Doubling of coastal flooding frequency within decades due to sea-level rise. Sci. Rep.7, 1399 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neumann, B., Vafeidis, A. T., Zimmermann, J. & Nicholls, R. J. Future Coastal Population Growth and Exposure to Sea-Level Rise and Coastal Flooding - A Global Assessment. PLOS ONE10, e0118571 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodworth, P. L. et al. Towards a global higher-frequency sea level dataset. Geosci. Data J.3, 50–59 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marcos, M., Puyol, B., Wöppelmann, G., Herrero, C. & García-Fernández, M. J. The long sea level record at Cadiz (southern Spain) from 1880 to 2009. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans116 (2011).

- 35.Marcos, M., Puyol, B., Calafat, F. M. & Woppelmann, G. Sea level changes at Tenerife Island (NE Tropical Atlantic) since 1927. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans118, 4899–4910 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talke, S. A., Kemp, A. C. & Woodruff, J. Relative Sea Level, Tides, and Extreme Water Levels in Boston Harbor From 1825 to 2018. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans123, 3895–3914 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talke, S. A. et al. Sea Level, Tidal, and River Flow Trends in the Lower Columbia River Estuary, 1853–present. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans125, e2019JC015656 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wöppelmann, G. et al. Rescue of the historical sea level record of Marseille (France) from 1885 to 1988 and its extension back to 1849–1851. J. Geod.88, 869–885 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Government of Canada, F. and O. C. Canadian Tides and Water Levels Data Archive. https://www.isdm-gdsi.gc.ca/isdm-gdsi/twl-mne/index-eng.htm (2019).

- 40.Charlottetown (01700). https://www.tides.gc.ca/en/stations/1700.

- 41.PEI Storm Surge Early Warning System (PSSEWS). https://pssews.peiclimate.ca/.

- 42.Parker, B. B. Tidal Analysis and Prediction. https://repository.oceanbestpractices.org/handle/11329/632, 10.25607/OBP-191 (2007).

- 43.Cheng, R. T., Casulli, V. & Gartner, J. W. Tidal, Residual, Intertidal Mudflat (TRIM) Model and its Applications to San Francisco Bay, California. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci.36, 235–280 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasheed, A. S. & Chua, V. P. Secular Trends in Tidal Parameters along the Coast of Japan. Atmosphere-Ocean52, 155–168 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pang, T., Wang, X., Mahmood, M. Q. & Basheer, S. Reconstruction of long-term hourly sea level data for Prince Edward Island, Canada. figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.27989570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Government of Canada, F. and O. C. Canadian Chart 1 Symbols, Abbreviations and Terms. https://charts.gc.ca/publications/chart1-carte1/sections/intro-eng.html (2019).

- 47.Feng, J. et al. Acceleration of the Extreme Sea Level Rise Along the Chinese Coast. Earth Space Sci.6, 1942–1956 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Son, Y.-T., Park, J.-H. & Nam, S. Summertime episodic chlorophyll a blooms near the east coast of the Korean Peninsula. Biogeosciences15, 5237–5247 (2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Our newly-generated dataset can be found on the open-source database, Figshare (10.6084/m9.figshare.27989570). There is no specific code produced to support this effort. All the analyses described in this paper can be accomplished by commonly-used statistical tools like Microsoft Excel or IBM SPSS Statistics. The original data for this reconstruction work can be downloaded via Canadian Tides and Water Levels Data Archive (https://www.isdm-gdsi.gc.ca/isdm-gdsi/twl-mne/index-eng.htm).