Abstract

Objective

There is uncertainty about whether early infusion of intravenous amino acids confers clinical benefits in critically ill patients. In this study, we aimed to test the hypothesis that intravenous amino acids could improve 90-day mortality in critically ill patients with normal kidney function.

Design

This is a multicentre, open-label, randomised, parallel-controlled trial.

Setting

20 ICUs across China.

Participants

1928 eligible critically ill patients with normal kidney function.

Interventions

In addition to standard care, patients assigned to the intervention group will receive a continuous infusion of amino acids at a rate to achieve a total daily protein intake of approximately 2.0 g/kg/day.

Main outcome measures

The primary endpoint is all-cause mortality at day 90 after randomisation. Secondary endpoints and process measures will also be reported. The primary conclusions will be based on a modified intention-to-treat analysis for efficacy.

Ethics and dissemination

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University (2020-NZKY-014-02 for the original version and 2020-NZKY-014-06 for the revised version) and all the participating sites. Results will be disseminated through journal publications and conference presentations.

Registration

This study protocol was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, and the identifier is ChiCTR2100053359 (https://www.chictr.org.cn/hvshowprojectEN.html?id=257327&v=1.7).

Keywords: Critical care, Amino acid, Protein, Kidney function

1. Introduction

It has been postulated that an early infusion of amino acids could improve both renal medullary perfusion and glomerular blood flow,1 and the induction of mitochondrial biogenesis, thus ameliorating the onset of acute kidney injury and reducing risk of death from subsequent multiple-organ dysfunction.2 A large-scale, multicentre randomised controlled trial recently demonstrated that an early infusion of amino acids can significantly reduce the onset of acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery.3 Furthermore, a post hoc subgroup analysis of a Phase II multicentre clinical trial conducted in critically ill patients suggested that an early infusion of amino acids may significantly reduce subsequent mortality.4,5

To confirm the potentially important benefits of providing an early infusion of amino acids in a broader critically ill population, we designed a Phase III, confirmatory trial with sufficient power to test the hypothesis that early intravenous amino acids could result in reduced 90-day mortality.

2. Methods and analysis

2.1. Study design

This is a multicentre, open-label, randomised, parallel-controlled trial conducted by the Chinese Critical Care Nutrition Trials Group (ChiCTR2100053359, https://www.chictr.org.cn/hvshowprojectEN.html?id=257327&v=1.7). The trial protocol was developed according to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) statement.6

2.2. Participants

All patients admitted to the participating hospital's intensive care units (ICUs) will be considered for eligibility. After obtaining signed informed consent, the investigator will have access to the electronic case report form and study web site, which will generate a random number to determine study treatment arm. The flow of patients through the trial will be reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 statement.7

2.2.1. Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Informed consent form obtained from the patient or next of kin;

-

2.

18 years old or older;

-

3.

Within 48 h of ICU admission;

-

4.

Expected to stay in ICU for more than two days (ex. not expected to be discharged on the day after enrolment);

-

5.

Have a working central venous access line through which the study intervention could be delivered;

-

6.

Be able to tolerate at least one litre of fluid volume per day;

-

7.

APACHEII score ≥15 or SOFA score ≥6.

2.2.2. Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Patients who are currently receiving selective COX-2 inhibitors;

-

2.

Patients receiving palliative treatment or expected to die within 48 h;

-

3.

Patients who have acute kidney injury (AKI), defined as current serum creatinine (SCr) increased 1.5 times preacute illness value OR with a recent increase greater than 26.5 μmol/L. [Note: If preacute illness creatinine values are unknown, an upper limit of normal: 90 μmol/L for females and 110 μmol/L for males was assumed8];

-

4.

Patients with malignant diseases receiving radiotherapy or chemotherapy;

-

5.

Patients currently receiving or scheduled for dialysis/renal replacement therapy;

-

6.

Patients with a kidney transplant;

-

7.

Patients who require treatment of a burn injury to greater than 20% of total body surface area;

-

8.

Patients who have a documented contraindication to the study intervention;

-

9.

Patients known to be pregnant or currently breastfeeding;

-

10.

Patients with severe liver disease (biopsy proven cirrhosis or documented portal hypertension with a known past history of either upper GI bleeding attributed to portal hypertension or of hepatic failure leading to encephalopathy/coma);

-

11.

Patients with a documented hypersensitivity (known allergy) to one or more of the included amino acids;

-

12.

Patients with a documented inborn error of amino acid metabolism.

Please note that the exclusion criteria No. 3 was revised after the start of the trial based on the results of the EFFORT-Protein trial, which reported that higher protein provision might be harmful to patients with AKI.9 During the first interim meeting conducted on March 4th, 2023, the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) recommended that recruitment of patients with AKI should be discontinued. This revision was, therefore, applied by the trial management committee and approved by the ethics committee on March 10th, 2023.

2.2.3. Sample size calculation

Conservative estimates of potential effect size were obtained from a previously published formal subgroup analysis demonstrating an early, continuous, supplementary, infusion of a standard mixture of L-amino acids may significantly reduce mortality (P = 0.034, 7.9% absolute risk difference, 0.65 relative risk reduction).5

Given best estimates of a baseline mortality rate of 15.9% in standard care patients,10 and assuming the relative risk reduction (0.65) is preserved, using standard formulas11 a trial of 1838 patients (919 per group) would have 90% power to detect an absolute risk difference of 5.5%. A trial of this size (N = 1838) also provided 80% power to detect a treatment effect as low as 4.8% absolute risk difference and, in the worst-case scenario, if the trial yielded a treatment effect as low as 3.4% absolute risk difference, the overall findings could still be expected to be statistically significant at the traditional two-sided P-value threshold of 0.05.

2.3. Randomisation and study intervention

2.3.1. Randomisation

Allocation concealment was maintained through the use of a central randomisation website (https://capctg.medbit.cn/en/2022/01/04/essential/) that was secure, encrypted, and password protected. The randomisation sequence was generated using SAS Version 9.4 with blocks of variable size and random seeds12 to ensure that allocation concealment could not be violated by guessing the allocation sequence at the end of each block. Randomisation was stratified within the study site. Stratification variables and their thresholds were concealed from site investigators to further prevent anticipation of the allocation sequence.13

2.3.2. Blinding

No placebo or alternative fluid was provided to patients assigned to the control group. Follow-up and analyses will be conducted in a blinded fashion: the investigators who contacted the patients or their relatives for Day 90 follow-up and the statisticians who analyse the data and report results will not be aware of the treatment assignment.

2.3.3. Interventional arms

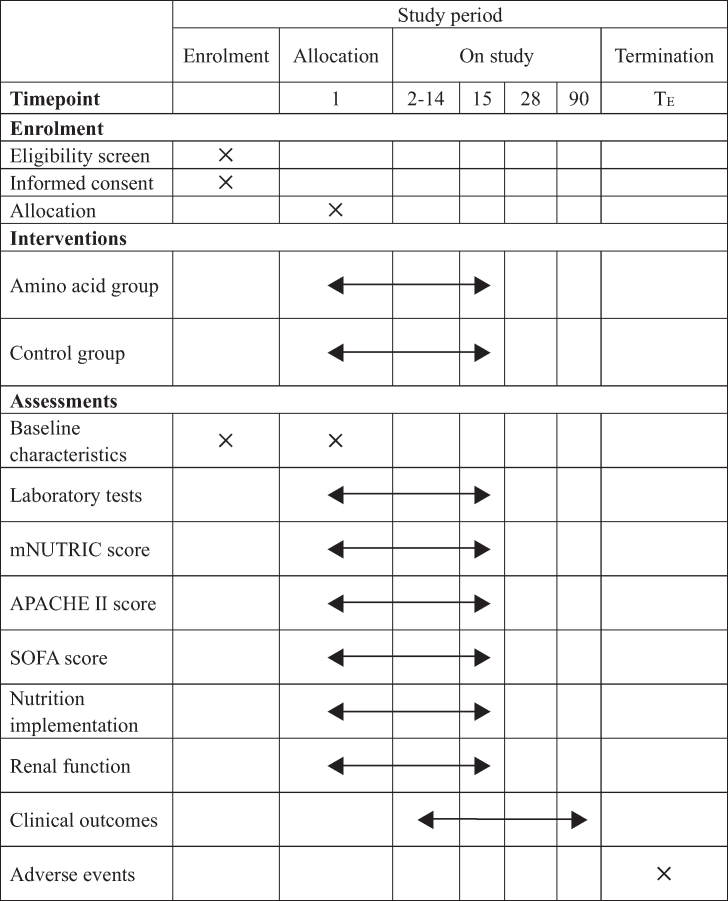

Each participant will be randomised to the amino acid group or the standard care group in a 1:1 ratio after enrolment. Table 1 shows the schedule of enrolment, interventions, and assessments according to the SPIRIT 2013 statement.

Table 1.

Schedule of enrolment, interventions, and assessments.

2.3.3.1. Arm#1 amino acid group

If randomised to the intervention arm, the patient will receive a continuous infusion of standard amino acids (18AA-VII Traumatic Amino Acid Solution, Haisco, China) delivered at a rate to achieve a total daily protein intake (including nutrition therapy and study intervention) of approximately 2.0 g/kg/day.

The initial infusion will be started at approximately 100 g/day. If the patients receive any form of enteral or parenteral nutritional support, the infusion rate of the study amino acid intervention was reduced such that the total protein intake from all sources (nutrition and study intervention) would reach approximately 2.0 g/kg/day. The protocol reduced the study amino acid infusion to a lower rate only if total protein from EN, PN, and study amino acid reached 2.5 g/kg/day.

The study intervention will be discontinued 15 days after randomisation, discharge from the study ICU, death, or when the patient's central venous catheter is removed, whichever occurs first. During the intervention, whenever a patient's blood urea increases to greater than 30 mmol/L, the amino acid infusion will be suspended until blood urea decreases to below 20 mmol/L.

The ESSENTIAL Study AA dosing tool (Wechat mini-program) was developed to help calculate study amino acid infusion rates based on a patient's current protein intake from enteral and parenteral nutrition and the patient's weight. Protein intake calculations for overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) patients will be based on their ideal body weight (ideal BMI set at 23 kg/m2).

The majority of patients will commence study amino acid at an infusion rate of 42 mL/h, which can provide 100 g protein per day.

2.3.3.2. Arm#2 standard care group

Standard care in the patients randomised to the control arm consists of a reasonable attempt to provide enteral or parenteral nutrition when the attending clinician judges the patient would tolerate feeding. The attending clinician will select the route, starting rate, metabolic targets, and energy/protein goals based on their usual practice according to the guidelines.

2.4. General management

All patients will be cared for by the local treating team at each participating ICU, including monitoring vital signs, obtaining necessary blood samples for laboratory measurement, fluid therapy, the use of mechanical ventilation, and vasopressors, etc. All cointerventions will be at the discretion of the treating clinical teams and recorded in the patient's medical record.

Initiation of renal replacement therapy (RRT): Initiation of RRT should be based on the criteria described by Bellomo et al.14 Patients who have acute kidney injury (at least 1.5 times increase in creatinine from known baseline value) and meet at least one criterion of the below makes the patient eligible for initiation of RRT:

-

1.

Anuria (negligible urine output for 6 h)

-

2.

Severe oliguria (urine output <200 mL over 12 h)

-

3.

Hyperkalaemia (potassium concentrations >6.5 mmol/L)

-

4.

Severe metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2 despite normal or low partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood)

-

5.

Volume overload (especially pulmonary oedema unresponsive to diuretics)

-

6.

Pronounced azotaemia (urea concentrations >30 mmol/L or creatinine concentrations >300 μmol/L)

-

7.

Clinical complications of uraemia (e.g. encephalopathy, pericarditis, neuropathy)

Timing of stopping RRT: Termination of RRT is based on criteria as used in the VA/NIH Acute Renal Failure Trial Network Study.15 If (on continuous renal replacement therapy or between intermittent haemodialysis sessions) diuresis >30 mL/h and there are no other indications for RRT, then endogenous creatinine clearance should be calculated using a 6-h urine collection period. If endogenous creatinine clearance is ≥20 mL/min, RRT should be discontinued. If endogenous creatinine clearance is ≤12 mL/min, RRT should be continued. If endogenous creatinine clearance >12 mL/min and <20 mL/min, continuation or termination will be the decision of the treating physician. Exact initiation and termination dates of RRT should be recorded in the eCRF.

2.5. Study outcomes and their measures

2.5.1. Primary outcome measures

The primary study outcome is defined as patient vital status (alive/dead) to be determined on the 90th calendar day postrandomisation.

2.5.2. Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes consist of the following: duration of ICU stay; duration of invasive mechanical ventilation; duration of hospital stay; death in ICU; death in hospital; survival duration; days alive out of hospital; incidence of clinically significant kidney dysfunction (proportion of patients per study arm); days of RRT; incidence of RRT (proportion of patients per study arm); continuing need for RRT at study day 90 (proportion of patients per study arm); days of clinically significant organ failure (reported by organ system); new-onset organ failure; new receipt of organ support.

2.5.3. Process measures

These process measures will include: time from ICU admission to feeding start; time from study enrolment to feeding start; number of days of study amino acid infusion in patients allocated to receive the study intervention; mean nutritional support days per 10 patient days in patients receiving EN and/or PN; mean nutrition support days per 10 patient days in patients receiving EN; mean nutrition support days per 10 patient days in patients receiving PN; percentage of patients who never received enteral or parenteral nutrition; percentage of patients fed within 24 h of ICU admission; mean energy (not including study amino acid infusion) delivered in kcal/patient-day; mean energy (including energy from study amino acid infusion) delivered in kcal/patient-day; mean total protein delivered in g/kg/patient-day; mean energy delivered per patient for each of the first seven days of ICU stay; mean protein delivered per patient for each of the first seven days of the ICU stay.

2.5.4. Definition of outcomes

Clinically significant kidney dysfunction: two points or more in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score for renal system.

New-onset organ failure: organ failure occurring during the first seven trial days and not present at randomisation. Organ failure is defined as an increase in the SOFA score of two points or more for each organ system.

New receipt of organ support therapy: requirement of organ support therapy (mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy, and vasoactive agents) not applied at enrolment.

All-cause mortality at day 90: defined as patient vital status (alive/dead) to be determined on the 90th calendar day postenrolment (the day of randomisation will be set as trial day 1).

2.5.5. Duration of treatment and follow-up

The study intervention will be discontinued 15 days after randomisation, discharge from the study ICU, death, or when the patient's central venous catheter is removed, whichever occurs first. Every randomised patient will be followed up until 90 days post-randomisation, unless death occurs first. If patients remained in hospital on study day 90, follow-up was censored, and outcomes were recorded as per status at day 90.

2.5.6. Reasons for withdrawal/discontinuation

Patients may withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason without prejudice to their future medical care by the investigator or at the study site. Investigators should attempt to determine the cause of withdrawal and, if agreed by the patient, let the patient receive follow-up at day 90. The extent of a patient's withdrawal from the study (i.e. withdrawal from further study treatment, withdrawal from active participation in the study, withdrawal from any further contact) should be documented. Efforts should be made to follow-up on all randomised patients to the extent that the patient agrees.

2.6. Data collection

A web-based electronic database (Unimed Scientific Inc., Wuxi, China) will be established for data collection and storage. All data will be input by the primary investigator or nominated investigator (less than two for each participating centre) approved by the trial management committee. Training for data entry will be performed by the supplier of the electronic database and the coordinating centre of the Chinese Critical Care Nutrition Trials Group.

2.6.1. Data analysis

The reporting and presentation of this trial will follow the CONSORT guidelines. Primary analyses will be based on the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population. Sensitivity analyses will be done on the per protocol (PP) population and all the randomised patients (full analysis set, FAS) to support inferences drawn from the primary modified intention to treat efficacy analysis.

A priori identified subgroup analysis will be conducted on the following baseline variables: age (>59 vs. ≤59), BMI (>25 vs. ≤25), SOFA (≥9 vs. <9), and Subjective Global Assessment muscle wasting (well nourished vs. other categories).

Please see the statistical analysis plan for additional details (see Supplementary Appendix).16

2.6.2. Data and safety monitoring

An independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), comprising experts in clinical trials, biostatistics, and intensive care were established. The committee reviewed information on all serious adverse events.

The DSMB will review the safety report with group allocation blinded after the first 600 and 1200 participants finishing their follow-up and have the right to stop the trial prematurely because of concerns about participant safety. Using the Haybittle–Peto approach,17,18 the DSMB was charged with informing the study management committee if there was a difference in serious adverse events between study groups that exceeded three standard deviations in magnitude.

2.7. Adverse events

Adverse events (AEs) are defined in accordance with the National Cancer Institute-Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events as any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical investigation subject administered an investigational intervention and which does not necessarily have to have a causal relationship with this treatment.

It is recognised that the patient population admitted to ICUs will experience a number of common aberrations in laboratory values, signs, and symptoms due to the severity of the underlying disease and the impact of standard therapies. These will not necessarily constitute an adverse event unless they require significant intervention or are considered to be of concern in the investigator's clinical judgement.

2.7.1. Severe adverse events

Severe adverse events (SAEs) are defined as any untoward medical occurrence that:

-

1.

Results in death

-

2.

Is life-threatening

-

3.

Requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

4.

Results in persistent or significant disability/incapacity

-

5.

Is a congenital anomaly/birth defect

-

6.

Is an important medical event that may require intervention to prevent one of the previously listed outcomes.

In this study, all SAEs will be reported regardless of suspected causality.

2.7.2. Monitoring of potential adverse events

The DSMB will be responsible for overseeing all subjects' safety and monitoring total mortality and serious adverse events. All serious adverse events occurring during the trial will be reported to the trial management committee and respective ethics committees within 48 h.

3. Discussion

Previous studies differed in the choice of amino acid formula.19 Almost all of them used balanced multiamino acid formulas containing 14 to 18 different amino acids, which mainly contained essential amino acids and were similar to the formula we chose. The PROTECTION trial used a 15-amino acid formula,3 as we chose the 18-amino acid formula (), both of which were a mixture of essential amino acids in majority. However, our formula had a higher content of branched-chain amino acids, which was a continuation of the selection from the phase II Nephro-Protective trial.4

Previous studies demonstrated that branched-chain amino acids can enhance mitochondrial biogenesis through the activation of the mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway,[20], [21], [22] thereby regulating stress-related metabolic disorders in critically ill patients.20,23 Moreover, the infusion of amino acids may increase nephron plasma flow by decreasing afferent arteriolar resistance,24,25 decreasing tubuloglomerular feedback activation26,27 and increasing cortical nitric oxide synthase activity,28,29 conferring potential clinical benefits for kidney protection and survival.5,30

The PROTECTION trial, which is the most important multiregional clinical trial on amino acid infusion in critically ill patients, investigated cardiac surgery patients.3 To confirm the potentially important benefits of providing an early infusion of amino acids to a broader critically ill population, we designed a Phase III, confirmatory trial with sufficient power to test the hypothesis that early intravenous amino acids could result in reduced 90-day mortality.

3.1. Limitations

No placebo or alternative fluid was provided to patients assigned to the control group; however, follow-up and analyses were conducted in a blinded fashion. Although the absence of a blinded placebo intervention may introduce bias, a placebo intervention would have interfered with protein delivery in the standard care patients. This potential for bias is partially mitigated by objective outcome recording and successful allocation concealment.31

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Jinling Hospital, Nanjing University (2020-NZKY-014-02). Ethics approval of each participating site is required before initiation of enrolment. This study is being conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as stated in the current version of Fortaleza, Brazil, 2013, and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act. This study is registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry with the identifier ChiCTR2100053359 (https://www.chictr.org.cn/hvshowprojectEN.html?id=257327&v=1.7).

Confidentiality issues

Processes, procedures, and technical methods will be implemented to protect information contained in the web-based application. Access to data will be provided in a secure and reliable manner. Safeguards for network and access will protect data in transit to authorised locations. Data will be monitored to prevent its unauthorised dissemination.

Data safety is maximised through several different mechanisms: physical access to computers and servers is electronically protected; the server is behind a firewall; the server is exclusively dedicated to database management (i.e. accessible only for researchers). Each participating sites will have access to the data of their own patients but not to the data of patients from other sites participating in the ESSENTIAL trial.

All reasonable measures will be taken to protect the confidentiality and identity of the patient and the patient's records according to the applicable regulations. All the data stored in the electronic database are deidentified to guarantee patients' privacy. Patient identity will not be revealed in any publication.

Potential risks and benefits

Amino acid intake at the dose achieved in this study has been proved safe in patients without acute kidney injury by the previous multicentre, Phase II, randomised clinical trial with no adverse effects or serious adverse effects documented.5 Furthermore, the dose achieved (2.0 g/kg/day) is currently recommended by many international nutrition guidelines.5

Dissemination policy

All the primary investigators of the participating ICUs and the sponsor will have full access to the data after the conclusion of the study. Anyone who wants to do a post-hoc analysis needs to submit a formal writing proposal to the writing and publication committee.

Authors’ contributions

Funding statement

The study was funded by the Key R&D Plan Fund Project in Jiangsu Province (No. BE2015685). The funders had no role in the study's design, data collection, and interpretation, or preparation of the manuscript. The decision to submit the manuscript was also made by the investigators.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Lu Ke reports financial support was provided by Nutricia Pharmaceutical (Wuxi). If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Trial status

The trial is currently ongoing (1859 patients recruited from 20 sites in China as per August 5, 2024), and recruitment will likely be completed by the end of 2024. We provide regular real-time updates through the research website (https://capctg.medbit.cn/en/2022/01/04/essential/).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccrj.2024.10.002.

Contributor Information

Lu Ke, Email: kelu@nju.edu.cn.

Weiqin Li, Email: ctgchina@medbit.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jufar A.H., Lankadeva Y.R., May C.N., Cochrane A.D., Bellomo R., Evans R.G. Renal functional reserve: from physiological phenomenon to clinical biomarker and beyond. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2020;319(6):R690–r702. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00237.2020. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romani M., Berger M.M., D'Amelio P. From the bench to the bedside: branched amino acid and micronutrient strategies to improve mitochondrial dysfunction leading to sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2022;14(3) doi: 10.3390/nu14030483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landoni G., Monaco F., Ti L.K., Baiardo Redaelli M., Bradic N., Comis M., et al. A randomized trial of intravenous amino acids for kidney protection. N Engl J Med. 2024 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2403769. NEJMoa2403769 (In en) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doig G.S., Simpson F., Bellomo R., Heighes P.T., Sweetman E.A., Chesher D., et al. Intravenous amino acid therapy for kidney function in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(7):1197–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3827-9. (In en) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu R., Allingstrup M.J., Perner A., Doig G.S., Group N.-P.T.I. The effect of IV amino acid supplementation on mortality in ICU patients may Be dependent on kidney function: post hoc subgroup analyses of a multicenter randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(8):1293–1301. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003221. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan A.W., Tetzlaff J.M., Gøtzsche P.C., Altman D.G., Mann H., Berlin J.A., et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D., Group C. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–732. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evaluation of elevated creatinine. (https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/935).

- 9.Heyland D.K., Patel J., Compher C., Rice T.W., Bear D.E., Lee Z.Y., et al. The effect of higher protein dosing in critically ill patients with high nutritional risk (EFFORT Protein): an international, multicentre, pragmatic, registry-based randomised trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10376):568–576. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02469-2. (In en) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xing J., Zhang Z., Ke L., Zhou J., Qin B., Liang H., et al. Enteral nutrition feeding in Chinese intensive care units: a cross-sectional study involving 116 hospitals. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):229. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2159-x. (In eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jennifer L.K, Alice S.W., Alfred S.E., Douglas W.T. Methods of sampling and estimation of sample size, Monographs in epidemiology and biostatistics: methods in observational epidemiology. Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulz K.F., Grimes D.A. Unequal group sizes in randomised trials: guarding against guessing. Lancet (London, England) 2002;359(9310):966–970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08029-7. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doig G.S., Simpson F. Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care. 2005;20(2):187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.04.005. discussion 191-193. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellomo R., Kellum J.A., Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. Lancet. 2012;380(9843):756–766. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palevsky P.M., Zhang J.H., O’Connor T.Z., Chertow G.M., Crowley S.T., Choudhury D., VNARFT Network, et al. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(1):7–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doig G.S., Lu K., Cheng L., Tao C., Weiqin L., Investigators obotET Statistical Analysis Plan for a multi-centre randomised controlled trial: the effect of early intravenous amino acid supplementation in critically ill patients with normal kidney function. EvidenceBased.net. 2024 Sydney. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haybittle J.L. Repeated assessment of results in clinical trials of cancer treatment. Br J Radiol. 1971;44(526):793–797. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-44-526-793. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peto R., Pike M.C., Armitage P., Breslow N.E., Cox D.R., Howard S.V., et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34(6):585–612. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220. (In eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pruna A., Losiggio R., Landoni G., Kotani Y., Redaelli M.B., Veneziano M., et al. Amino acid infusion for perioperative functional renal protection: a meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2024 doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2024.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carré J.E., Orban J.-C., Re L., Felsmann K., Iffert W., Bauer M., Suliman H.B., et al. Survival in critical illness is associated with early activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(6):745–751. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0326OC. (In eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romani M., Berger M.M., D'Amelio P. From the bench to the bedside: branched amino acid and micronutrient strategies to improve mitochondrial dysfunction leading to sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):483. doi: 10.3390/nu14030483. (In eng) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L., Han J. Branched-chain amino acid transaminase 1 (BCAT1) promotes the growth of breast cancer cells through improving mTOR-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;486(2):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.101. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morio A., Tsutsumi R., Kondo T., Miyoshi H., Kato T., Narasaki S., et al. Leucine induces cardioprotection in vitro by promoting mitochondrial function via mTOR and Opa-1 signaling, Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. Nutr Metabol Cardiovasc Dis. 2021;31(10):2979–2986. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2021.06.025. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer T.W., Ichikawa I., Zatz R., Brenner B.M. The renal hemodynamic response to amino acid infusion in the rat. Trans Assoc Am Phys. 1983;96:76–83. (In eng) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods L.L. Mechanisms of renal hemodynamic regulation in response to protein feeding. Kidney Int. 1993;44(4):659–675. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.299. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seney F.D., Jr., Persson E.G., Wright F.S. Modification of tubuloglomerular feedback signal by dietary protein. Am J Physiol. 1987;252(1 Pt 2):F83–F90. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1987.252.1.F83. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomson S.C., Vallon V., Blantz R.C. Kidney function in early diabetes: the tubular hypothesis of glomerular filtration. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2004;286(1):F8–F15. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00208.2003. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tolins J.P., Shultz P.J., Westberg G., Raij L. Renal hemodynamic effects of dietary protein in the rat: role of nitric oxide. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;125(2):228–236. (In eng) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao B., Xu J., Qi Z., Harris R.C., Zhang M.Z. Role of renal cortical cyclooxygenase-2 expression in hyperfiltration in rats with high-protein intake. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2006;291(2):F368–F374. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00500.2005. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Losiggio R., Redaelli M.B., Pruna A., Landoni G., Bellomo R. The renal effects of amino acids infusion. Signa Vitae. 2024;20(7):1–4. doi: 10.22514/sv.2024.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forder P.M., Gebski V.J., Keech A.C. Allocation concealment and blinding: when ignorance is bliss. Med J Aust. 2005;182(2):87–89. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06584.x. (In eng) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.