Abstract

Objective

Frusemide is a common diuretic administered to critically ill children intravenously, by either continuous infusion (CI) or intermittent bolus (IB). We aim to describe the characteristics of children who receive intravenous frusemide, patterns of use, and incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI), and to investigate factors associated with commencing CI.

Design

Retrospective observational study.

Setting

Paediatric intensive care unit (PICU), the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne.

Participants

Children who received intravenous frusemide during PICU admission lasting ≥24 h between 2017 and 2022.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcome was the daily dose of frusemide. Secondary outcomes included timing of therapy from PICU admission, fluid balance at frusemide initiation, additional diuretic therapy, and the incidence of AKI at admission and frusemide initiation. Children who received CI were compared with those who received IB only using multivariable logistic regression analyses.

Results

Nine thousand three ninety-four children were admitted during the study period. A total of 1387 children (15 %) received intravenous frusemide, including 220 children (16 %) by CI. The CI group were younger (132 vs 202 days, p = 0.01), had higher PIM-3 scores (2.2 vs 1.5, p-value <0.001), more congenital heart disease (CHD) (72.3 % vs 60.6 %, p <0.01), and higher incidence and severity of AKI at frusemide initiation than the IB group (65.7 % vs 40.1 %, p-value <0.001). CI were commenced later than IB (46 vs 19 h into admission, p <0.001) and at higher doses (4.3 vs 1.5 mg/kg/day, p-value <0.001). In multivariable analyses, CHD (aOR 1.67, 95 % CI 1.16-2.40, p <0.01) was associated with CI.

Conclusion

Frusemide infusions are administered more commonly to children with CHD, later in PICU admission, and at higher daily doses compared to IB. Children who receive CI have a higher incidence and severity of AKI at initiation.

Keywords: Frusemide, Diuretics, Paediatric intensive care unit, Fluid overload, Acute kidney injury

1. Introduction

Diuretic agents are the mainstay of fluid removal therapy for children with fluid overload in intensive care. Frusemide, a loop diuretic, is the most common first-line agent. It directly inhibits the sodium-potassium-chloride cotransporter (NKCCs) on the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Frusemide by continuous infusion (CI) is proposed to have beneficial pharmacodynamic properties by providing continuous tubular drug exposure and more stable urine output.1,2 Intermittent bolus (IB) dosing is more commonly prescribed in clinical practice3

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a heterogenous syndrome that describes reduced glomerular filtration. It occurs in approximately 30 % of children in intensive care.4 Fluid accumulation occurs commonly in critically ill children with AKI,5 making fluid removal an important component of AKI management. There are limited and conflicting data regarding the effects of frusemide on AKI progression and resolution. In children with fluid overload, frusemide can decrease renal venous congestion and improve kidney recovery. In hypovolemic patients, frusemide can potentially worsen AKI through hypovolaemia and renal vasoconstriction mediated by renin angiotensin aldosterone system activation.6,7 Previous studies comparing different modalities of frusemide have not described the incidence of AKI at frusemide initiation.[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]

There are few studies reporting the patterns of intravenous frusemide use in children admitted to intensive care. Therefore, we performed a retrospective study aiming1 to compare the characteristics of children who received CI or IB dosing;2 to describe the dose and timing of intravenous frusemide;3 to compare the incidence and severity of AKI and fluid overload at the commencement of intravenous frusemide therapy; and4 to investigate the factors associated with commencing CI. We hypothesized that children who received CI, compared with IB dosing, had greater severity of illness, greater fluid overload, and higher AKI grade at commencement of therapy.

2. Methodology

We performed a retrospective, observational study at the Royal Children's Hospital Paediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU) between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2022. The permission to conduct the study was provided by The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC number QA/99506/RCHM-2023). Children were eligible if they were 18 years old or younger, admitted to PICU for at least 24 h, and received intravenous frusemide for at least 24 h within the first 10 days of PICU admission. Children with chronic kidney disease (based on intensive care admission diagnostic codes), renal transplant recipients, and those who received any renal replacement therapy (RRT) during the index admission were excluded.

2.1. Data collection

The demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded from the PICU database and included age, sex, weight, admission diagnosis, Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Intensive Care Registry diagnostic codes13 and specific conditions (cardiopulmonary bypass, sepsis, and oncology diagnosis), Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS) score, Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM-3) score,14 frusemide exposure within 1 month prior to PICU admission (as home medications or in hospital administration), use of invasive (mechanical ventilation) and noninvasive respiratory support (high-flow nasal cannula and noninvasive ventilation), vasoactive medications, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), intensive care length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and intensive care mortality.

2.2. Diuretic therapy

Diuretic therapy administered within the first 10 days of each admission was collected from the electronic medical record (EPIC, WI, USA). Children were assigned to the CI group if they received any continuous infusions ≥24 h, regardless of prior bolus doses. The first admission where a child received a CI was selected for the CI group. Children were assigned to IB group if they received IB dosing only. Children in CI group were also grouped according to the exposure to IB dosing prior to CI initiation (CI-IB + vs CI-IB-). We recorded the timing of administration from admission, duration of therapy, and daily dose in mg per kg per day. Co-administration of other diuretics including spironolactone, thiazide diuretics and metolazone was also recorded. No unit-based protocol for mode of administration exists.

2.3. Acute kidney injury and fluid balance

Creatinine data at baseline and during the PICU admission were used to diagnose and stage AKI according to the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition.15 Patients younger than 1 month old were excluded from the analysis of AKI. The baseline serum creatinine level was estimated as the lowest value within the previous 3 months prior to intensive care admission. For children in whom a baseline serum creatinine level was not available, the baseline serum creatinine was imputed using the Schwartz–Lyon equation and an age- and sex-based height-independent equation (Q(age) equation) as previously validated in the paediatric literature (Supplement Table 1).[16], [17], [18], [19] Creatinine data between 12 h prior to and 4 h after frusemide initiation were used to estimate AKI status at frusemide initiation. Severe AKI was defined as KDIGO stage 2 or stage 3. Cumulative fluid balance percent at frusemide initiation was calculated as the cumulative fluid input minus output (L) from PICU admission, divided by admission body weight (kg) and multiplied by 100. Positive fluid balance was referred to as fluid overload. Daily fluid balance was calculated and recorded from the time of frusemide initiation.

2.4. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the daily dose of frusemide. Secondary outcomes included timing of therapy from PICU admission, fluid balance at frusemide initiation, additional diuretic therapy, and the incidence of AKI at admission and frusemide initiation.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were described using frequencies and percentages (categorical data), means and standard deviations (SDs; normally distributed continuous data), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs; skewed continuous data). We compared the clinical characteristics of children based on the mode of frusemide administration using the Chi-square, t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test as appropriate.

We performed a multivariable logistic regression analysis to explore factors associated with the administration of CI. Univariate regression analysis was performed to identify potential predictor variables. Variables available prior to frusemide commencement that were clinically and statistically different between groups in univariate analyses (p-value <0.1) were considered for inclusion in the multivariable analysis.

Analyses were performed with R software, version 4.1.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the specific packages listed in the Supplemental Digital Content and Stata Statistical Software, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist for cohort studies was completed and is found in the Supplementary file. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

There were 9394 PICU admissions during the study period and 1387 (15 %) children received intravenous frusemide for 24 h or greater and were eligible for inclusion in this study. A total of 1167 (84 %) children received IB dosing only and 220 (16 %) received CI (Fig. 1). In children who received CI, 190 (86.4 %) had IB prior to the initiation of CI. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort, overall and stratified by the group, are shown in Table 1. The median age of children who received frusemide was 189 days (IQR: 53, 1227) and the most common diagnosis was congenital heart disease (CHD) (62.4 %).

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all PICU patients and those receiving intravenous frusemide therapy by continuous infusion or intermittent bolus dosing.

| Variables | Total PICU patients (n = 9394) | Patients who received intravenous frusemide administration |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1387) | Continuous infusion (n = 220) | Intermittent bolus only (n = 1167) | p-valuea | ||

| Age, days | 752 (131, 3157) | 189 (53, 1227) | 132 (50, 444) | 202 (54, 1407) | 0.01 |

| Male sex | 5343 (57) | 771 (56) | 116 (53) | 655 (56) | 0.58 |

| PICU admission body weight, kg | 12 (5.6, 26.5) | 6.6 (4.0, 15) | 5.6 (3.8, 9.1) | 6.9 (4.0, 16.0) | <0.01 |

| Admission diagnosisb | |||||

| Congenital heart disease | 3737 (39.8) | 866 (62.4) | 159 (72.3) | 707 (60.6) | <0.01 |

| Gastrointestinal/renal | 336 (3.6) | 47 (3.4) | 8 (3.6) | 39 (3.3) | 0.83 |

| Injury | 596 (6.3) | 91 (6.6) | 3 (1.4) | 88 (7.5) | <0.01 |

| Miscellaneous | 1390 (14.8) | 185 (13.3) | 36 (16.4) | 149 (12.8) | 0.15 |

| Neurological | 1507 (16.0) | 90 (6.5) | 5 (2.3) | 85 (7.3) | <0.01 |

| Respiratory | 1828 (19.5) | 108 (7.8) | 9 (4.1) | 99 (8.5) | 0.03 |

| Severity of illness | |||||

| PIM-3 score | 1.2 (0.6, 3.2) | 1.6 (1.0, 4.0) | 2.2 (1.2, 4.9) | 1.5 (1.0, 3.9) | <0.001 |

| RACHS score (798, nCI = 151, nIB = 647) | 6.6 (1.7, 14.3) | 6.6 (4.7, 15.3) | 8.5 (6.6, 23.3) | 6.6 (3.8, 14.3) | <0.01 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 2481 (26) | 696 (50) | 143 (65) | 553 (47) | <0.001 |

| Fluid overloadc, percent | 2.8 (0.4, 6.4) | 2.8 (0.4, 6.4) | 3.9 (−1.0, 9.0) | 2.7 (0.5, 6.1) | 0.25 |

| Frusemide use prior to PICU admissiond | 1889 (20) | 483 (35) | 113 (51) | 370 (32) | <0.001 |

| As home medication | 773 (8) | 238 (17) | 49 (22) | 189 (16) | 0.03 |

| In hospital use | 1233 (13) | 261 (19) | 67 (30) | 194 (17) | <0.001 |

| Intensive care therapies and outcomes | |||||

| Use of vasoactive drugs | 3508 (37) | 1036 (75) | 194 (88) | 842 (72) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory supporte | 7001 (75) | 1346 (97) | 219 (100) | 1127 (97) | 0.02 |

| Duration, hours | 35 (12, 101) | 94 (50, 178) | 168 (107, 351) | 81 (46, 156) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation (MV) | 5340 (57) | 1251 (90) | 207 (94) | 1044 (90) | 0.03 |

| MV prior to frusemide initiation | 1181 (22) | 1181 (85) | 206 (94) | 975 (84) | <0.001 |

| Duration, hours | 27 (10, 90) | 70 (37, 144) | 133 (74, 239) | 64 (28, 124) | <0.001 |

| ECMO | 265 (2.8) | 73 (5.3) | 22 (10.0) | 51 (4.4) | <0.01 |

| ECMO prior to frusemide initiation | 60 (0.6) | 60 (4.3) | 22 (10.0) | 38 (3.3) | <0.01 |

| Duration, hours | 98 (59, 167) | 85 (52, 162) | 88 (75, 179) | 80 (45, 151) | 0.19 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 602 (6.4) | ||||

| Peritoneal dialysis | 425 (4.5) | ||||

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | 177 (1.9) | ||||

| PICU LOS, hours | 48 (24, 114) | 132 (82, 237) | 212 (140, 425) | 119 (74, 208) | <0.001 |

| Hospital LOS, hours | 231 (115, 597) | 447 (249, 1030) | 765 (349, 1979) | 408 (241, 925) | <0.001 |

| PICU Mortality | 272 (2.9) | 37 (2.7) | 6 (2.7) | 31 (2.7) | 0.95 |

ANZPICR = Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Intensive Care Registry. AKI = acute kidney injury. ECMO = extracorporeal embrane oxygenator. LOS = length of stay. PIM-3 score = Paediatric Index of Mortality 3 score. RACHS score = Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery score.

Data are presented as n (%) or median with 25th and 75th centiles unless otherwise specified.

p-value represents a statistical difference between CI and IB group.

Defined by principal admission diagnoses in the Australian and New Zealand Paediatric Intensive Care Registry data dictionary.

Percentage of fluid overload is cumulative fluid balance (L) adjusted by body weight (kg) measured from PICU admission to the day frusemide started.

Diuretic administration within 1 month of PICU admission.

Respiratory support includes the use of high-flow nasal cannula, noninvasive ventilation, and mechanical ventilation.

3.1. Characteristics of children who received a frusemide infusion

Children in the CI group, compared with the IB group, were younger, had higher PIM-3 scores, more exposure to frusemide prior to PICU admission, and higher rates of mechanical ventilation and ECMO at frusemide initiation (Table 1). More children in the CI group were admitted for CHD, but fewer were admitted with injury, neurological, and respiratory conditions, compared with the IB group.

On multivariable analysis, the factors associated with CI at frusemide initiation was CHD (adjusted odds ratio: 1.67 [95 % CI: 1.16-2.40], p-value <0.01). There was no association between age, PIM-3 score, mechanical ventilation, and fluid overload and CI at frusemide initiation.

3.2. AKI and fluid balance at initiation of intravenous frusemide

More children (≥1 month old) in the CI group had any AKI or severe AKI at PICU admission and frusemide initiation (Table 2; Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). There were no statistically significant differences in the rate of AKI at frusemide initiation between children who received prior IB doses (CI-IB+) and those who did not (CI-IB-) (Supplement Table 2). The odds of receiving CI were 4.6-fold higher in those with severe AKI (Table 4).

Table 2.

Frequency of acute kidney injury at PICU admission and at frusemide initiation.

| Variables | Patients who received intravenous frusemideb |

p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1131) | Continuous infusion (n = 181) | Intermittent bolus only (n = 950) | ||

| Paediatric intensive care admissionc | 1070 | 169 | 901 | |

| Any AKI | 472 (44.1) | 111 (65.7) | 361 (40.1) | <0.001 |

| AKI stage 2 and 3 | 213 (19.9) | 58 (34.3) | 155 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| Frusemide initiationd | 905 | 145 | 760 | |

| Any AKI | 311 (34.4) | 86 (59.3) | 225 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| AKI stage 2 and 3 | 137 (15.1) | 54 (37.2) | 83 (10.9) | <0.001 |

PICU = paediatric intensive care unit; AKI = acute kidney injury

Data are presented as n (%) or median with 25th and 75th centiles unless otherwise specified.

p-value represents a statistical difference between CI and IB group.

Age ≥ 1 month.

Denotes children with available creatinine data: Creatinine values within the first 24 h of PICU admission were used to stage AKI on PICU day 0.

Denotes children with available creatinine data: Creatinine values between 12 h prior to and 4 h after were used to stage AKI at frusemide initiation.

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analysis of factors associated with continuous frusemide infusion.

| Variable | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | p-value | Odds Ratio (95 % CI) | p-value | |

| Time to frusemide initiation, day | 1.70 (1.55, 1.87) | <0.001 | ||

| Age, days | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | <0.01 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.07 |

| PIM score | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.54 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.50 |

| Congenital heart disease | 1.70 (1.23, 2.33) | <0.01 | 1.67 (1.16, 2.40) | <0.01 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 2.06 (1.53, 2.78) | <0.001 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation prior to frusemide initiation | 2.90 (1.65, 5.09) | <0.001 | 1.76 (0.86, 3.61) | 0.12 |

| Fluid overload at frusemide initiation, mL/kg | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.01 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.05 |

| In children older than 1 month | ||||

| Time to frusemide initiation, day | 1.80 (1.62, 2.00) | <0.001 | ||

| Age, days | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | <0.01 | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | 0.14 |

| PIM score | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.64 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.27 |

| Congenital heart disease | 1.83 (1.31, 2.56) | <0.001 | 1.39 (0.90, 2.16) | 0.14 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 1.95 (1.41, 2.69) | <0.001 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation prior to frusemide initiation | 2.31 (1.30, 4.09) | <0.01 | 1.70 (0.67, 4.29) | 0.26 |

| Fluid overload at frusemide initiation, mL/kg | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | <0.01 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.29 |

| AKI at PICU admission | 2.86 (2.03, 4.04) | <0.001 | ||

| AKI stage 2 or 3 at PICU admission | 2.51 (1.75, 3.61) | <0.001 | ||

| AKI at frusemide initiation | 3.47 (2.40, 5.00) | <0.001 | ||

| AKI stage 2 or 3 at frusemide initiation | 4.84 (3.22, 7.27) | <0.001 | 4.58 (2.93, 7.16) | <0.001 |

PIM = Paediatric Index of Mortality, AKI = acute kidney injury, CI = confidence interval.

Fluid overload at frusemide initiation was not statistically different between the CI and IB groups (3.9 % [IQR: -1.0 to 9.0] vs 2.7 % [IQR: 0.5-6.1], p-value 0.25) (Table 1). Patients in the CI-IB- group had significantly less fluid overload compared with the CI-IB + group (Supplement Table 2). Greater negative fluid balance was achieved in the CI compared with the IB group at 24, 48, and 72 h after initiation (Supplementary Fig. 3). There were no clinically significant differences in serum sodium or potassium in the first 24 h of therapy (Supplementary Table 3).

3.3. Frusemide dose and timing at commencement of therapy

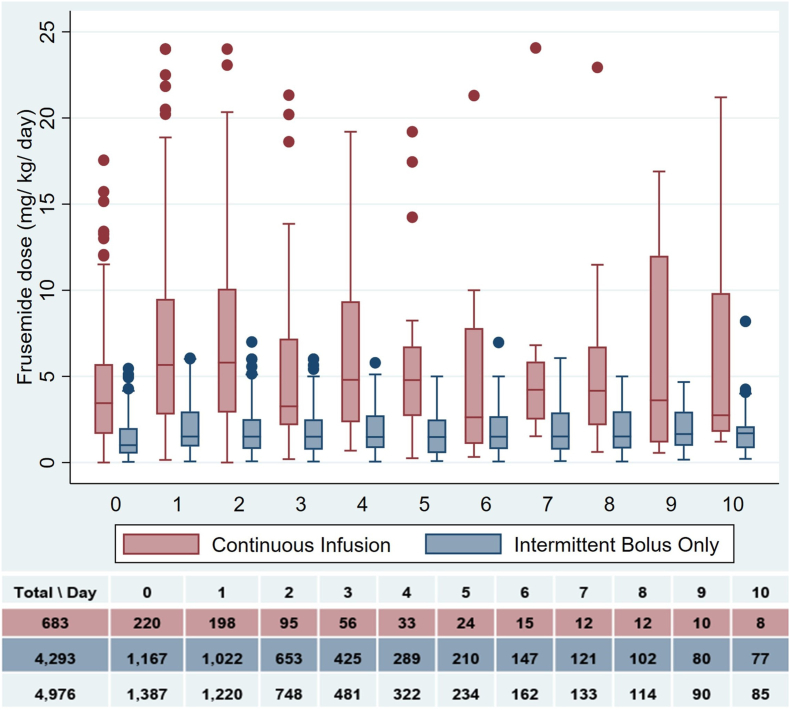

Daily frusemide doses were higher in the CI group compared with the IB group over the first 24 h (3.4 [IQR: 1.6-5.7] vs 1.0 mg/kg/d [IQR: 0.5-2.0], p-value <0.001) and over the study period (4.3 [IQR: 2.0-7.2] vs 1.5 mg/kg/d [IQR: 0.7-2.5], p-value <0.001) (Table 3, Fig. 2). CIs were started later after PICU admission (46 [IQR: 27-91] vs 19 h [IQR: 11-35], p-value <0.001) and had shorter duration of administration as compared with IB doses (50 [IQR: 35-93] vs 62 h [IQR: 38-110], p-value 0.02). Median time to CI initiation was longer in those who received prior IB doses (CI-IB+) compared with those who did not (CI-IB-) (20 [IQR: 7, 33] vs 56 h [IQR 33, 98], p-value <0.001) (Supplementary Table 2). Time to frusemide initiation and the daily dose at frusemide initiation by group are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. In the CI-IB + group, median cumulative urine production and frusemide dose were greater after CI initiation compared with the prior group. However, urine volume in mL per mg of frusemide was not statistically significantly different prior to and after CI initiation (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Timing, duration and additional diuretic agents in children based on the frusemide infusion and intermittent bolus dosing groups.

| Patients who received frusemide administration |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients (n = 1387) | Continuous infusion (n = 220) | Intermittent bolus only (n = 1167) | p-valuea | |

| Time to first dose from PICU admission, hours, | 21 (12, 42) | 46 (27, 91) | 19 (10, 35) | <0.001 |

| Duration of IV frusemide administration, hours, | 61 (37, 108) | 50 (35, 92) | 62 (38, 110) | 0.02 |

| Frusemide dose in the first 24 h, mg/kgb | 1.2 (0.6, 2.5) | 3.4 (1.6, 5.7) | 1.0 (0.5, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Daily frusemide dose, mg/kg/dayb | 1.5 (0.9, 3.0) | 4.3 (2.2, 8.0) | 1.5 (0.7, 2.5) | <0.001 |

| Additional diuretics | ||||

| Spironolactone | 876 (63.2) | 191 (86.8) | 685 (58.7) | <0.001 |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | 127 (9.2) | 63 (28.6) | 64 (5.5) | <0.001 |

| Metolazone | 10 (0.7) | 7 (3.2) | 3 (0.3) | <0.01 |

| Urine catheter | 1253 (90.3) | 208 (94.5) | 1045 (89.5) | 0.02 |

PICU = paediatric intensive care unit.

Data are presented as n (%) or median with 25th and 75th centiles unless otherwise specified.

p-value represents a statistical difference between CI and IB group.

Daily frusemide dose is calculated for each frusemide administration day.

Fig. 2.

Daily frusemide dose (mg/kg/day).

3.4. Additional diuretic therapy

The characteristics of additional diuretic use are shown in Table 3. Spironolactone was the most common adjunct overall (63.2 %). More children in the CI group received spironolactone (86.8 % vs 58.7 %, p-value <0.001) and thiazide diuretics (28.6 % vs 5.5 %, p-value <0.001).

3.5. Clinical outcomes

PICU and hospital LOS were greater in those receiving CI (212 [IQR: 140-425] vs 119 h (IQR: 74-208), p-value <0.001 and 765 [IQR: 349-1979] vs 408 h [IQR: 241-925], p-value <0.001, respectively). There was no difference in mortality between groups.

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

In this single-centre study of children admitted to intensive care for ≥24 h, intravenous frusemide was administered to 15 % of children, with one in six receiving this therapy by CI. Compared with children who received IB, those who received CI were younger, received more intensive care therapies, and were more likely to be admitted with CHD. The factors associated with CI was CHD at frusemide initiation.

Any AKI or severe AKI at either PICU admission or frusemide initiation were more common in the CI group compared with the IB group. There was a 4.6-fold greater odds of severe AKI at frusemide initiation in the CI group. CI were commenced later after PICU admission than IB and had shorter duration of administration. For the first 24 h of therapy, the frusemide dose was approximately 3.5-fold greater in the CI group. Additional diuretic agents were more common in the CI group and spironolactone was the most common agent. Children in the CI group had greater duration of intensive care and hospital LOS but no difference in mortality.

4.2. Comparison with other studies

A single-centre study from Canada reported the frequency of intravenous frusemide in children in intensive care and the associated mortality.3 This report describes some similar findings to our study such as the younger age, higher incidence of CHD and later administration in children receiving CI compared with IB. However, their reported use of adjunct diuretic agents was much less than in our study. Although they did not report the incidence of AKI, they proposed an interaction between AKI and higher cumulative doses in the CI group. Two other single-centre studies found no association between frusemide and AKI after initiation. The first study of 362 critically ill children with AKI reported no difference in progression of AKI severity after initiation between children receiving a CI compared with those receiving no frusemide (no children received IB).20 The second study of 456 children reported no difference in the incidence of AKI after exposure to IB when compared with no frusemide.21

4.3. Implications of findings

Our study showed that intravenous frusemide delivered as a CI, compared with IB, was commenced later in admission, in children with more severe AKI, and more commonly in children with CHD. Most children who received CI had received IB prior to infusion suggesting that clinicians utilise infusion as a rescue modality, if IB is inadequate or deemed unlikely to be efficacious. Continuous infusions were more common in children after CHD surgery suggesting that clinicians may perceive CI to be associated with less haemodynamic instability or that fluid overload is greater in this group. Fluid overload was only marginally higher in the CI group overall, which implies that other factors may influence the use of infusions. Higher dosing in the CI group and the higher rate of administration of additional diuretic agents likely reflects the “rescue” nature of CI following an inadequate clinical response to IB in a population with higher AKI. In patients who received IB prior to CI initiation, urine output and frusemide dose were greater after CI initiation; however, urine output per mg of frusemide was not different. This implies that urine output was likely dose-related rather than the mode of administration. Institutional practice regarding the starting dose for IB dosing is also considerably less relative to the suggested starting dose for CI at our institution. Moreover, the CI group had a higher rate of frusemide use prior to PICU admission suggesting the possibility of diuretic resistance. Factors such as the presence of oedema, haemodynamic stability, the availability of venous access, oliguria, and the availability of peritoneal dialysis in children after CHD surgery may influence decision-making regarding frusemide therapy and its modality.

5. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are the large cohort of critically ill children and the comparison of frusemide administration modalities. However, there are limitations. Firstly, the retrospective nature of the study means that only associations can be inferred. The study was performed in a single centre and therefore the findings may not be generalisable. Eighty six percent of those who received CI were administered IB therapy prior. Therefore, the associated effects of diuretic therapy likely reflect the cumulative effects of total dosing and may be confounded by the prior use of IB. We did not report reasons for commencing CI. Secondly, we reported the incidence of AKI but not the progression following diuretic therapy because of patient attrition per day. Third, we reported fluid balance calculated from fluid balance charts which have inherent inaccuracies. However, most children had in-dwelling urinary catheters and therefore fluid balance was likely to be accurate. We excluded those who received RRT because we specifically aimed to focus on frusemide therapy. Analysing the effects of diuretic agents would have been difficult to interpret in the context of administration of RRT. Diuretic use in children who ultimately require RRT for fluid removal is important to investigate to understand the response and timing of RRT initiation. Finally, we did not investigate the haemodynamic effects of frusemide therapy or complications including deafness. This would likely be affected by many other unaccounted factors in a retrospective analysis. A prospective study is suggested to investigate the causal relationship between mode of frusemide administration and responsiveness to the therapy (e.g. challenge test), progression of AKI, haemodynamic instability and diuretic complications.

5.1. Conclusions

In children in intensive care receiving intravenous frusemide, CI were administered in 16 % of admissions and commonly following a period of IB. Compared with IB, CI were administered to younger children, more commonly in those with CHD, and in those who received chronic diuretic therapy. They were administered, on average, at greater starting dose, more than twice as long after PICU admission and for shorter duration compared with IB dosing. Children receiving CI have higher rates of AKI and greater severity at PICU admission and at commencement of frusemide therapy.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nutnicha Preeprem: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Emily See: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Siva Namachivayam: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Ben Gelbart: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccrj.2024.10.001.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ellison D.H., Felker G.M. Diuretic treatment in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(20):1964–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1703100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Escudero V.J., Mercadal J., Molina-Andújar A., Piñeiro G.J., Cucchiari D., Jacas A., et al. New insights into diuretic use to treat congestion in the ICU: beyond furosemide. Frontiers in Nephrology. 2022;2 doi: 10.3389/fneph.2022.879766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaetani M., Parshuram C.S., Redelmeier D.A. Furosemide in pediatric intensive care: a retrospective cohort analysis. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 2024;11 doi: 10.3389/fped.2023.1306498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alobaidi R., Morgan C., Goldstein S.L., Bagshaw S.M. 2020. pp. 82–91. (Population-based Epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury in critically ill children∗). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gist K.M., Selewski D.T., Brinton J., Menon S., Goldstein S.L., Basu R.K. Assessment of the independent and synergistic effects of fluid overload and acute kidney injury on outcomes of critically ill children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(2):170–177. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000002107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricci Z., Deep A. Furosemide and acute kidney injury: is Batman the cause of evil? Intensive Care Medicine – Paediatric and Neonatal. 2023;1(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abraham S., Rameshkumar R., Chidambaram M., Soundravally R., Subramani S., Bhowmick R., et al. Trial of furosemide to prevent acute kidney injury in critically ill children: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Indian J Pediatr. 2021;88(11):1099–1106. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03727-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor D., Durward A., Mayer A., Turner C., Tibby S.M., Murdoch I.A. Comparison between continuous versus bolus furosemide administration in oliguric postoperative paediatric cardiac patients. Crit Care. 2003;7(2) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luciani G.B., Nichani S., Chang A.C., Wells W.J., Newth C.J., Starnes V.A. Continuous versus intermittent furosemide infusion in critically ill infants after open heart operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;64(4):1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)00714-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klinge J.M., Scharf J., Hofbeck M., Gerling S., Bonakdar S., Singer H. Intermittent administration of furosemide versus continuous infusion in the postoperative management of children following open heart surgery. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(6):693–697. doi: 10.1007/s001340050395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh N.C., Kissoon N., al Mofada S., Bennett M., Bohn D.J. Comparison of continuous versus intermittent furosemide administration in postoperative pediatric cardiac patients. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(1):17–21. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zarzor M., Hasaneen B., Abouelkheir M.M., El-Halaby H. Furosemide continuous infusion versus repeated injection in the management of acute decompensated heart failure in infants with left to right shunt: a randomized trial. Egyptian Pediatric Association Gazette. 2023;71(1):77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Australian and New Zealand paediatric intensive care Registry. https://www.anzics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ANZPICR-Data-Dictionary.pdf

- 14.Straney L., Clements A., Parslow R.C., Pearson G., Shann F., Alexander J., et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(7):673–681. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120(4):c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwartz G.J., Munoz A., Schneider M.F., Mak R.H., Kaskel F., Warady B.A., et al. New equations to estimate GFR in children with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(3) doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pottel H., Hoste L., Martens F. A simple height-independent equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2012;27(6):973–979. doi: 10.1007/s00467-011-2081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bacchetta J., Cochat P., Rognant N., Ranchin B., Hadj-Aissa A., Dubourg L. Which creatinine and cystatin C equations can be reliably used in children? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6(3):552–560. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04180510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoste L., Dubourg L., Selistre L., De Souza V.C., Ranchin B., Hadj-Aïssa A., et al. A new equation to estimate the glomerular filtration rate in children, adolescents and young adults. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29(5):1082–1091. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vivek S., Rameshkumar R., Muthu M., Karunakar P., Chidambaram M., Kumar C.G.D., et al. Furosemide in the management of acute kidney injury in the pediatric intensive care unit—retrospective cohort study. Intensive Care Medicine – Paediatric and Neonatal. 2023;1(1):6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai X., Chen J., Li W., Bai Z., Li X., Wang J., et al. Association between furosemide exposure and clinical outcomes in a retrospective cohort of critically ill children. Front Pediatr. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.589124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.